Oxford University Press's Blog, page 313

October 13, 2017

A Tale of Two New York Cities [excerpt]

New York is a city of many things to many people. But more and more those people are being divided. Those who have the means to live in comfort and splendor, and those struggling to survive in a once vast urban landscape that grows smaller and smaller with each year. In this excerpt from his book The Creative Destruction of New York City, author and urban scholar Alessandro Busà, gives us the lay of this new land where all are welcome, particularly if they can afford it.

Now let me tell you another tale of two New Yorks, circa 2017. There’s a gilded-age city of gleaming glass towers where Wall Street managers, Hollywood celebrities, exiled Russian oligarchs, and Middle East billionaires live their glamorous lives or stash their offshore cash. And then there’s a city where even the professional middle class is one rent hike away from eviction.

It’s a city of creatives, freelancers, students, artists, teachers, nurses, clerks and firefighters struggling with exorbitant rents; of store owners living under the constant threat that their businesses will shut down; and of thousands of families coming in and out of the shelter system. And these two New Yorks, where the rich devour more and more of the urban space, while ordinary citizens are stuck, are growing further apart. A brand new global class of city consumers has been born, and they’re ousting the rest of us — the working classes, the middle classes, and even the upper middle classes — from the city we love. The sheer scale of their consuming power is entirely changing the rules of the urban development game, which today seems focused exclusively on producing a city that is more custom- tailored to their ostentatious consumption demands.

In the process, ordinary New Yorkers are pushed further out of this gilded city of unaffordable rents or left to observe their neighborhoods while they gradually morph into exclusive enclaves for the super- wealthy. Meanwhile, the power of city producers has never been greater. Those who count in real estate, banking, and finance have managed to ensure that their interests are safeguarded at city hall, in Albany, and in Washington. They have ensured that, regardless of who sits at different levels of government, the fundamental rules of the game (opening up more avenues for profit and being subsidized in the process) will remain untouched. Their ambitious agenda, based on a relentless use of rezoning and branding, is driving an era of unprecedented urban transformations and prompting the physical, social, and symbolic re-engineering of districts and communities across the board, from Flushing to East Brooklyn, from Staten Island to the South Bronx. No corner is off- limits to capital: the whole of the city is up for grabs, and new spectacular tides of creative destruction are on the horizon.

City producers and city consumers are transforming the city into a repackaged wonderland of lavish real estate, dotted by pockets of poverty where a new urban underclass lives its daily struggles. New York, like no other city, encapsulates the contradictions and inequalities that surround the process of neoliberal urbanization: it only takes a subway ride from Billionaire’s Row to Spanish Harlem to get a visual reminder of the way the rich and poor live in the city. Even though a trend toward a concentration of wealth among the city’s top earners goes back at least four decades, it has widened precipitously over the last 15 years.

By the end of Bloomberg’s tenure, the top one percent of earners in New York City brought in 40% of the city’s total income. And things have only worsened under de Blasio’s watch. Today, New York has among the highest levels of income inequality in the United States, concurring globally with the likes of Rio de Janeiro and Sao Paulo. And the most unequal of all US counties is unsurprisingly Manhattan.

Here, the average apartment in 2015 was priced at a whopping $1.95 million. In this island of wealth and inequality, median rentals have increased consecutively for years, and today, at above $4,000 a month, they are among the highest on the globe. And things aren’t much better in Brooklyn and Queens, where rents are at around $3,000 a month. Prepare to see more of the same happening soon in the South Bronx, where residents in Mott Haven have recently learned that their neighborhood is currently being marketed as “the Piano District” to hip newcomers, courtesy of developers Somerset Partners and Chetrit Group New York’s harsh social inequalities have come a long way, and de Blasio won’t be able to change the rules of a game that was established way before he moved his first steps into the world of politics. They are the result of a political turn that, grown out of the “neoliberal euphoria” of the laissez-faire economics of the early 1970s, has morphed into a system of crony capitalism, where an ever larger government is there to give blessings to well-connected special interest groups. It is a system that through corporate welfare, financial deregulation, and the public financing of private losses, has made sure that inequality was built into it, at the federal as much as at the local level.

This system, which certainly hasn’t changed after the 2007/ 2008 financial crisis (and the ensuing government-sponsored trillion-dollar bank bailout), has traditionally translated into a chronic shrinking of federal spending on housing, services, and infrastructures, at the same time when government was handing out special tax privileges and public funding to big private ventures. In cities, it is a system in which the enormous sway of city producers (the local elite) and city consumers has changed the rules of the game entirely. Those cities that won at the game, like New York or San Francisco, keep attracting top industries and global consumers, and have gradually morphed into citadels where the most outrageous wealth at the top clashes with unimaginable poverty at the bottom. Those that didn’t make it are sinking in a downward spiral of poverty, disinvestment, and population loss: these are cities like Youngstown, Ohio, where almost 40% of residents live below the poverty line, or Flint, Michigan, where even tap water can kill you.

Featured Image: New York City by Kevin Dooley. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post A Tale of Two New York Cities [excerpt] appeared first on OUPblog.

October 12, 2017

Animal of the month: 10 facts about bats

Bats are often portrayed in popular media as harbingers of doom and the embodiment of evil. They’re consistently associated with death, malevolent witches, and vampires. Batman, with his bat-like attributes, is easily the most sinister superhero in the league. Most people will have seen or heard about this creature, but what do we really know about them?

So this month, ending on All Hallows’ Eve, we are celebrating this misunderstood mammal. We’ve found ten facts you may not have known about bats:

Bats use echolocation to inform them how nearby objects are and employ this tool in hunting. Their physiologies allow them to produce sounds of 80 kHz (20 times higher frequency than what humans can hear), but smaller species can produce sounds up to 120 kHz.

There are an estimated 1,116 species of bats, a number which grows as new species are discovered. They have been commonly split into two groups: the plant-eating megabats and the omnivorous microbats.

Bats are the only mammals able to fly. The unusual configuration of the bat’s wing allows them to generate thrust which propels them forward. Some species are more capable of flying longer distances, for example the Brazilian free‐tailed bat migrates over 1,000 km from the United States to Mexico for the winter.

Mexican long-tongued bat (Choeronycteris mexicana) drinking from a cactus by U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Headquarters. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Mexican long-tongued bat (Choeronycteris mexicana) drinking from a cactus by U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Headquarters. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Madagascar’s endemic sucker-footed bat uses wet adhesion in the pads on its wrists and ankles to stick heads-up on smooth leaves, instead of the usual head-down hanging position.

Hibernation up to eight months is common with bats. Most mammals do not hibernate in sub-zero temperatures, but some bat species have been observed to buck this trend, overwintering in below freezing temperatures. These are cold-hardy animals!

About one quarter of all living mammal species are bats.

Mother bats leave their offspring to search for food sources. Mother and child relocate through contact calls, which can be specific to individual groups of bats.

Roosts can be set up in a variety of surprising places. Some of the strangest include the Egyptian pyramids, churches, disused mines, and libraries, where they have been credited with protecting the books from insects!

Despite being popularly portrayed as such, bats are not blind. Some species use their vision to locate prey in adequate light. But most species are unable to see well, so use their echolocation for hunting and to orientate themselves.

Species that live in trees escape the oncoming cold of winter by migrating south. Flying and foraging along the way, some species travel as far as 2,000 km, such as the Nathusius’ bats.

Featured image credit: Fruit bats by shellac. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr .

The post Animal of the month: 10 facts about bats appeared first on OUPblog.

Wielding wellness with music

The intersection between music and health occurs on a continuum of care ranging from the personal use of music to “feel better”, to professional music therapy work. While music therapists may work more often in the professional end of the continuum, our experiences and knowledge as clinicians and scholars provide us a unique perspective on the overall role of music in health.

Thus, I asked experts in the field to share their top suggestions for how you can incorporate music in your life to promote your own physical, social, spiritual, emotional, or mental health.

Melita Belgrave, Ph.D. MT-BC, Associate Professor at Arizona State University, studies the impact of intergenerational music therapy on older adult well-being and suggests:

1. Listen to music for validation Listen to specific music throughout the day to validate your current feelings. Create your own music playlist and use it as a guide for the entire day or different parts of the day. Try actively engaging with the music, whether it be singing, clapping your hands, tapping your feet, dancing, or specific movements that match the lyrics of the song.

2. Experience new music Find a new favorite song by listening to unfamiliar music by a preferred artist or within a preferred genre. Listen to the song on repeat. Identify the music elements that you enjoy about the song—are you drawn to the instrumentation? The background singers? The harmony? Learn the words if there are lyrics. Notice how you feel when listening to the new song. Learning something new in music can provide an extra spark of creativity and provide a break from daily tasks that have become monotonous.

3. Use music for rediscovery Often times, music holds strong memories for us. We can hear a song and be instantly transported back to a memorable period of our life. Sometimes in life we find ourselves not feeling as courageous or fearless as we did when we were younger. Identify a time in your life when you felt most courageous, fearless, or brave. What age were you during that time? What were your musical preferences? Locate three songs that you listened to during that time that you associate with these feelings. While listening to the songs, reflect on why you felt courageous during those times. What aspects of the music matched your past feelings—is it a bass line? The instrumentation? The lyrics? Select one of these songs to be your theme song for when you need to feel courageous, fearless, or brave.

Suzanne Hanser, Ph.D., MT-BC, Professor at Berklee College of Music and author of Integrative Health through Music Therapy: Accompanying the Journey from Illness to Wellness, recommends the following:

“Listen To Relaxes Music Girl Woman Headphones” via Max Pixel. Public Domain via FreeGreatPicture.

“Listen To Relaxes Music Girl Woman Headphones” via Max Pixel. Public Domain via FreeGreatPicture.1. Find your power song Everyone needs to be empowered sometimes, particularly when you are not feeling confident or motivated. Look through your music playlists or ask friends if they know songs or pieces of music that provide an empowering intention. Play the song, listen deeply to its message, and take it all in.

2. Compose a personal jingle The repeated chanting of “mantra” has been applied through centuries of spiritual practices to bring harmony to the soul, or to connect with the divine. In contemporary translation, a personal jingle is a chant or song that sets an affirmation or message to a catchy tune. Think of something that you wish to remind yourself today, like “I can do it!” or “Everything’s going to be all right,” or “Let peace begin with me.” As you begin to chant your message, emphasize the intonation until the chant becomes a melody. Repeat as often as you like. Chanting your special personal jingle is useful to focus your attention, especially when you find that your mind is busy with negative thoughts.

3. Sing a lullaby When you are feeling stressed, it might help to soothe yourself with music. Is there a tune that relaxes you? Is there a memorable song that was sung to you by a loved one? Do you find certain music comforting or peaceful? You can try listening to these selections, and if it feels right, hum along, or sing them yourself.

Meganne Masko, Ph.D., MT-BC, Assistant Professor at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis who explores music therapy and spiritual care writes:

There are disagreements about this in the literature, but the vast majority of end-of-life researchers describe spirituality as including connections to one’s self (intrapersonal experiences), to others (interpersonal experiences), to and with time, to the natural world, to something larger than one’s self (e.g, traditions, institutions, rituals), and/or to a higher power. It’s important that people have access to spaces where they can express their spirituality, whatever it might be, or whether or not it’s associated with a particular religious tradition.

With that background information, people can enhance these connections by using music for meditation and self-reflection, spending time with others, creating sacred spaces, and/or establishing new traditions. This can occur through:

Singing school, club, or team songs

Singing, playing, or listening to songs from a particular region of the country or world

Listening to recorded music while meditating or engaging in mindfulness

Participating in musical groups like choirs, community bands, or garage bands

Creating soundtracks of their lives

Listening to music about nature, or music that is meant to reflect nature

Creating visual art, journaling, or writing poetry while listening to music meaningful to the person

Listening to music, or engaging in live music making, as a religious practice. This usually involves singing, playing, or listening to music associated with a particular religion.

Featured Image Credit: field, wheat, grain, crop and tree by Vladimir Malyutin. CC0 Public Domain via Unsplash.

The post Wielding wellness with music appeared first on OUPblog.

The feminist roots of modern witchcraft [excerpt]

Throughout modern history, witchcraft has been predominately practiced by women. Historically, women were considered more likely than men to partake in magic due to their “inherent moral weakness and uncontrolled sexual nature.” Unsurprisingly, as witchcraft spread throughout the United States in the 1960s and 1970s, it captured the interest of the growing feminist movement. In the following excerpt from The Oxford Illustrated History of Witchcraft and Magic, Owen Davies discusses the feminist roots of modern witchcraft in America.

Through the 1960s and 1970s the pagan witch religion, in its various forms, spread overseas in a very modest way.

It was in America that the witchcraft religion became a significant aspect of the counter-culture phenomenon, expressed most cogently in the feminist movement. After all, the majority of executed witches during the witch trials were women. With grossly misleading execution figures circulating widely in popular culture, the idea that the historic witch persecutions resulted in the deaths of millions of women understandably led to such provocative descriptions as ‘gynocide’. Couple this with the Gardnerian notion that the Church had sought to exterminate a liberated witch fertility religion that expressed its sexuality, and the feminist interest in witchcraft was obvious. They rightly saw social parallels between the past and present in terms of patriarchy and misogyny. In 1968 one radical feminist movement, which was not Wiccan in inspiration, called themselves ‘WITCH’, the Women’s International Terrorist Conspiracy from Hell. Members of WITCH organized public protests and street theatre events to highlight the dominance of patriarchal capitalism.

A selection of jars containing herbs and other ingrediants used by cunning folk (professional practitioners of magic) in Britain on display at the Museum of Witchcraft. Image credit: “Herb collection” by Midnightblueowl. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

A selection of jars containing herbs and other ingrediants used by cunning folk (professional practitioners of magic) in Britain on display at the Museum of Witchcraft. Image credit: “Herb collection” by Midnightblueowl. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Various feminist voices soon appeared in the pagan witch community, rejecting the patriarchy expressed in the leadership of early Wiccan groups and some of the gender biases in their rituals. In 1971 the Hungarian-American pagan Zsuzsanna Budapest produced a pamphlet manual of Gardnerian rituals solely for women called the Feminist Book of Lights and Shadows. The most influential feminist Wiccan text of the 1970s, however, was The Spiral Dance: A Rebirth of the Ancient Religion of the Great Goddess. Its author Miriam Simos, better known as Starhawk, took Wicca in a new direction with a strong emphasis on ecological concerns, feminist spirituality, and shamanism. She co-founded the activist witch movement ‘Reclaim’ to further press for the social, political, and environmental concerns that resonated with her conception of a goddess nature religion. By the year 2000, Spiral Dance had sold more than 300,000 copies, influencing many feminists within and beyond the Wiccan community, and it was one of the first significant American influences on British Wiccans. One downside of its popularity was that Starhawk repeated the old falsehood that nine million people were executed as witches during the European witch-hunts.

Modern American witchcraft also had its gay activists, who were motivated both by the global campaign for homosexual rights, and also prejudice within modern witchcraft. Despite being a religion inspired by the paganism of the ancient world and its diverse sexual expressions, in the early decades of Wicca the emphasis had been on the importance of the ‘natural’, fertile relationship between male and female. The gay New York witch Leo Martello, who founded the Witches’ Liberation Movement and the Witches Anti-Defamation League, stirred up the debate during the early 1970s.

The likes of Spiral Dance had a substantial influence on a growing trend towards solitary practice in pagan witchcraft and other expressions of modern magic. From the Golden Dawn through to Gardnerian Wicca, modern magic had been imagined as a community with hierarchies, collective forms of worship, and initiations and rituals that involved at least two people. But as Wicca matured so the idea of the solitary practitioner grew. From being Gardner’s High Priestess in the early days of Wicca, Doreen Valiente came to prefer solitary magical working. In 1978 she wrote Witchcraft for Tomorrow as a guide on how to initiate oneself into the witches’ craft without needing to join a coven. ‘Many people, I know, will question the idea of selfinitiation, as given in this book,’ she wrote. ‘To them I will address one simple question: who initiated the first witch?’ Once the desire for modern magicians to form fraternities, orders, and covens based on notions of ancient secret societies ebbed, the impulse to diversify and innovate spread. One did not need to religiously follow some imposed set text or a set of rituals defined by someone else. The phrase ‘believing without belonging’, which sociologists of religion coined to describe the decline of Christian church attendance, also applied to the growth of modern paganism in the same era. Regional and local expressions of pagan witchcraft proliferated, drawing upon folk magic practices, for example.

These days there are those who call themselves witches but who do not consider themselves pagan, but are inspired by the spells, charms, and remedies of the cunning-folk of the recent past. Away from pagan witchcraft, an array of solitary magicians have forged their own tailor-made rituals and practices.

Featured image credit: “tarot-cards-magic-fortune-telling” by MiraDeShazer. CC0 via

Pixabay.

The post The feminist roots of modern witchcraft [excerpt] appeared first on OUPblog.

Who said what about Margaret Thatcher? [quiz]

No-one was neutral about Margaret Thatcher. During her premiership (and ever since), she has inspired both wild enthusiasm and determined opposition, and many vivid descriptions as a result. Having led her party to three general election victories (two of which were landslides) she ranks as the most popular British party leader in terms of votes cast for the winning party, with over 40 million ballots casted for the Conservatives between 1979 and 1987. Despite this, many critics have described Margaret Thatcher as divisive, accusing her of paying little attention to social issues such as women’s rights, unemployment, and racism. Known simply as “Maggie” by both supporters and opponents, she was famously dubbed the ‘Iron Lady’ by the Soviet Defence Ministry newspaper Red Star.

Do you know which of these remarks were made by her supporters and which by her opponents? Test your knowledge with our quiz.

Quiz image credit: Margaret Thatcher by WikiImages. Public Domain via Pixabay .

Featured image credit: Margaret Thatcher bids farewell after a visit to the United States in 1981 by Williams, US Military. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Who said what about Margaret Thatcher? [quiz] appeared first on OUPblog.

October 11, 2017

Sheepskin and mutton

This is a sequel to the previous post of 4 October 2017. Last time I mentioned an embarrassment of riches in dealing with the origin of the word sheep, and I thought it might not be improper to share those riches with the public. As a rule, I choose to say only the most general things about the attempts by scholars to solve a hard etymological problem, but the story of sheep is so intricate that it calls for a change of the habitual format. How then did language historians try to explain the origin of sheep, a word known only in West Germanic?

Our earliest etymologists believed that the words of modern languages could be traced to Hebrew (presumably, spoken by Adam and Eve in Paradise). If Hebrew failed to reveal the source, they turned to Greek and Latin for help. Surprisingly, look-alikes usually turned up. John Minsheu (1617) cited Hebrew kespebh or kesebakh “lamb.” He followed his predecessor Helvigius, the author of the first etymological dictionary of German, who, while searching for the etymons of German Schaf, suggested Hebrew scheh or Greek skepáō “I cover,” the latter “on account of a sheep’s rich fleece.” (See Andreas Helwig in Wikipedia. The article there needs a correction: Helwig’s dictionary appeared in 1611, though it is easier to find copies of the 1620 edition.) Both dictionaries were written in Latin, but Minsheu combined Latin with English glosses. The transliterations of the Hebrew words are by Helvigius and Minsheu, but both also printed the words in their original spelling. Today, the familiar transliteration of the Hebrew word for “sheep” is kebes.

What did they call the lamb in the bottom right-hand corner? Semantics hardly bothered them at that moment.

What did they call the lamb in the bottom right-hand corner? Semantics hardly bothered them at that moment.In principle, neither conjecture is improbable. The animal name could migrate from or into Hebrew, and, when it comes to the etymology of sheep, references to fleece are no less common today than they were four centuries ago. Kebes and West Germanic skæpa– (with long æ) are more alike than it seems at first sight, for, as mentioned more than once in this blog, many words in Indo-European have “movable s,” that is, a root can begin with s or lose it for the reasons that have never been found out. This means that we are allowed to compare kebes and (s)kæpa-. Animal names are easy to borrow, but the relatively few very old words that Semitic and Indo-European undoubtedly share are due to the proximity of the tribes that spoke those languages. Nowhere in the course of ancient history were the Semites in close contact with the speakers of West Germanic. Skepáō and skæpa- also sound alike, but they cannot be related, for the vowels match badly, and Greek p should have corresponded to Germanic f. Borrowing from Greek is out of the question for the same reasons as those mentioned above.

In the first half of the nineteenth century, few researchers risked an even tentative etymology of sheep. One of them was Charles Richardson, whose huge English dictionary appeared in the late thirties. His source of inspiration was Horne Tooke (see the post of 2 August 2017 and Stephen Goranson’s comment), and this is one of the reasons his etymologies lack merit. They are useful only in so far as the entries in the dictionary contain surveys of earlier opinions. But I think his derivation of sheep is his own. He mentioned German schaffen “to do, make, create” and schieben “to push.” From a historical point of view, the two verbs have nothing in common, and only schieben could have shed light on sheep. Richardson referred to Greek próbaton “cattle,” from the verb probáinein “to advance,” and suggested that sheep had once meant “moving, going, driven cattle; drove.” It was not a bad idea, and semantic analogs of the Greek concept of cattle exist in several languages, Hittite and Old Icelandic among them. However, neither schaffen nor schieben has anything to do with sheep, though schaffen and sheep once turned up as cognates in a list by a modern scholar (1971).

Moving property. And the shepherd, the “herd” of sheep, is also here.

Moving property. And the shepherd, the “herd” of sheep, is also here.Hensleigh Wedgwood, Skeat’s most active predecessor in the area of English etymology, believed that sheep was a borrowing of Polish skop “wether, (castrated) ram.” (The Gothic cognate of wether meant “lamb”! If I am not mistaken, in the United States, few English speakers recognize the word wether despite the existence of the once popular tongue twister “I wonder whether the wether will weather the weather or whether the weather the wether will kill” and the unforgotten word bellwether.) According to Wedgwood, sheep had been referred to the Polish word before. Most probably, he found this etymology in the once popular German dictionary by Konrad Schwenck. He supported his derivation by the history of French mouton, allegedly from Latin mutilus “maimed,” but mouton is, most probably, a Celtic word from a different root. Compare mutilate and see mutton in dictionaries.

I wonder whether the wether will weather the weather.

I wonder whether the wether will weather the weather.The phonetic match (skop ~ skæpa) is imperfect, because skæpa– had a long vowel, but, to be sure, while taking over a word from another language, people could modify the pronunciation of the source. Again we encounter the ghost of a loanword! Skeat said in the first (1882) edition of his dictionary that the Polish word had been borrowed from Germanic and set up the nonexistent root SKAP “castrate.” This was a false move. The fully transparent Polish noun has several exact cognates in neighboring languages and is indeed related to the Slavic verb meaning “to castrate,” while sheep never referred to castration. Already at our time, a distinguished Slavic linguist believed that skæpa– had been borrowed from Slavic. However, his scenario is as unlikely as Skeat’s: the vowels are again too different, and the meanings do not match. The weak aspect of this etymology is made especially clear by the existence of German regional Schöps (Middle High German schopz ~ schöpz) “castrated ram.” This is indeed a borrowing of Czech scopec (stress on the first syllable)!

I promised a long walk through the explanations of the origin of sheep because I wanted to make it clear how much stands behind a line or two in our dictionaries. In 1880, a leading German philologist (his name is August Fick) cited Sanskrit chāga “bull,” posited the variation -g- with -p- in chāga ~ skæpa-, and thus reconstructed the Germanic word’s Indo-European heritage, even though the oldest meaning of the word remained unclear. He was supported by a prominent Greek etymologist and by the great Friedrich Kluge, who refused to change his opinion despite the fact that in the field of Germanic he found no allies. In one important dictionary, he could even read that the Sanskrit word certainly has nothing to do with sheep! Fick’s chāga appeared in all ten editions of his dictionary. After Kluge’s death, his amanuensis (Kluge was blind for many years), favorite pupil, and editor of his etymological dictionary quietly removed the Sanskrit word from the entry Schaf, and it never appeared there again.

The same name often applies to several animals. So why not to “wolf” and “sheep”?

The same name often applies to several animals. So why not to “wolf” and “sheep”?This is not the end of the story: for the dénouement you will have to wait another week, but don’t expect a sensation, the more so as last time I cited the most possible solution. Yet if you are in the habit of opening dictionaries to discover the etymology of English words and one day decide to look up sheep, you will find a short string of indisputable cognates and the verdict: “Origin unknown.” Even if this verdict has merit, it is instructive to know how many frustrated efforts stand behind it.

The post Sheepskin and mutton appeared first on OUPblog.

A twenty-first century reinterpretation of dreams?

An important event is due to take place in Vienna next year for all those involved in the theory and practice of psychoanalysis. For the wider general public this event may also be of interest—accustomed as we all are, across the world now, to deploying the ideas and the language of psychoanalysis in everyday life.

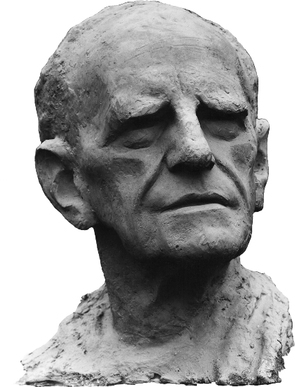

On 4 June 2018, at the campus of the prestigious Medical University of Vienna, where Sigmund Freud trained as a young doctor, and in the city where he lived and worked for most of his life, a larger than life size bronze sculpture of the founder of psychoanalysis, made by the gifted artist Oscar Nemon, will be unveiled.

Freud had dreamed as a young student doctor, at this same university, that one day perhaps his bust would sit alongside the figures before him that he so greatly admired. Now, with particular thanks to the Vienna Medical University, the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society, the International Psychoanalytic Association, and to the European Psychoanalytic Federation—and in great part with thanks to the Nemon family, who are preparing the statue, made over eighty years ago, to be cast and transported to Vienna, this dream of Freud’s will be realised.

A timely event, we might say, for the author who is most famous for his book on The Interpretation of Dreams. That book heralded the beginnings of the discipline of psychoanalysis, and Freud knew it would be many, many years before his ideas would be properly considered.

But, on this occasion, it is also thanks to a certain Donald Woods Winnicott—perhaps most of all—that this commemorative moment in history takes place. Winnicott, as President of the British Psychoanalytic Society, was instrumental in raising awareness and funds in the 1960s for getting this same statue by Nemon cast and put up in North London for the first time. It was ‘a debt of honour’, Winnicott felt, that was owed by psychoanalysts to the creator of their life work. Winnicott succeeded and Nemon’s Freud statue was unveiled in London in 1970 just months before Winnicott’s death.

And it is this same statue that will be recast once again to come to Vienna next year and once again, as it happens, it is Winnicott who is posthumously and, by chance, the instigator of these events.

Oscar Nemon’s daughter, Lady Aurelia Young, together with her sister-in-law, Alice Nemon-Stuart, owner of the estate of Oscar Nemon, assisted our editorial team’s research into the Nemon statue of Freud and approached us to see if we could help to bring about what was also the Nemon family’s dream, which was to place Oscar’s statue of Freud in Vienna, as originally planned. When first created in the early thirties by Nemon, the Freud statue was to have been placed in the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society for the celebration of Freud’s 80th birthday. But this had never happened at the time, or for years thereafter, despite many attempts.

Oscar Nemon’s bust of D. W. Winnicott, plaster cast, 1971. Reproduced courtesy of the Oscar Nemon Estate.

Oscar Nemon’s bust of D. W. Winnicott, plaster cast, 1971. Reproduced courtesy of the Oscar Nemon Estate.Since 1970, there has been no progress with bringing the statue to Vienna.

But with the timely appearance of the newly published Winnicott in the Collected Works, Winnicott has again become the instrument for securing interest in the Freud Nemon statue and its return to Vienna.

This statue had had its own special and poignant history when Winnicott first heard about it. The young, but successful, Croatian sculptor, Oscar Neumann, as he was known then, had been summoned to Vienna to take Freud’s likeness in 1931 and Freud was very pleased with the sculpted outcome. Nemon admired Freud greatly. And Freud was pleased with the results. He wrote to a colleague:

“there is something or rather quite a lot in it. The head which the gaunt goatee bearded artist has fashioned from the dirt—like the good Lord—is a very good and an astonishingly life like impression of me.”

But in 1938, Freud and his family fled as refugees from Vienna, welcomed and supported in London by Dr. Ernest Jones a previous President of the British Psychoanalytic Society, and in another year, Freud himself was dead. Nemon, also fleeing from Nazi persecution, also made his way to London and in time became the sculptor of key figures in British and in international society: the Queen and Winston Churchill, standing in the palace of Westminster, among so many more, as well as many figures from the world of psychoanalysis—Winnicott among these.

Now, however, a full 80 years to the exact day when Freud left Vienna, he is due to return, in Nemon’s sculpted form, to stand under the trees on the campus of his old university.

Despite the lack of success over so many years, when I contacted the heads of the international psychoanalytic communities, telling them about the statue Winnicott had helped to place in London, now perhaps being brought to Vienna, I received immediate and strong support for this. Within a few months plans were in place from Dr. Stephan Doering and the Rector at the Vienna Medical University to secure the funds and bring about Freud’s, Nemon’s, and I would like to think, Winnicott’s dreams.

In this present day instance, the interpretation of these many dreams might be said to have been a pleasure—for all of us involved—to be able to re-interpret!

Featured image credit: Oscar Nemon’s Studio with Nemon and his statue of Freud. The Donald Woods Winnicott Archive, in the care of the Wellcome Library, London, courtesy of the Winnicott Trust.

The post A twenty-first century reinterpretation of dreams? appeared first on OUPblog.

Buddhist nationalists and ethnic cleansing in Myanmar part II: the rise of religious nationalism and Islamophobia

Since August over 420,000 Rohingya have fled Myanmar, citing human rights abuses and seeking temporary refuge in Bangladesh. In part one we looked at the background and context of the Rohingya crisis. In this second part of Sarah Seniuk’s and Abby Kulisz’s interview with Michael Jerryson, they look at the role of Buddhist nationalism and the impact of Islamophobia in the developing crisis.

Sarah: How do you see the relationship between the Burmese government and the military affecting the continuation of violence against the Rohingya?

Michael: That’s an important question not just for Myanmar, but for Southeast Asia as well. We are seeing countries turning more towards an authoritarian government throughout Southeast Asia. For example, there have been outcries about Cambodia’s treatment and jailing of opposition leaders. In Thailand, the junta has been in control since May 2014. In Myanmar, there has been a long history of the military being in control. It appears right now that the military and the civilian government are working in unison, reinforcing one another.

The recent past is pertinent to this question. When the junta was in charge of the country, they would jail people who were too outspoken on Buddhist nationalism. They jailed U Wirathu, who is a very vocal member of another Buddhist nationalist group called the 969 movement. The term “969” is shorthand for the Triple Jewel in Buddhism: the 9 traits of the Buddha, 6 traits of the Dharma, and 9 traits of the Sangha. U Wirathu is a very high level Buddhist monk who was jailed because of his political pressure to make the government more focused on Buddhist nationalism and against Muslims. He was released in 2013 along with others, and the democratic arena has allowed him and others to flourish in their populism.

Whereas the junta was oppressive overall and silenced forms of Buddhist nationalism, the democratic civilian government has provided room for Buddhist nationalists to grow and develop. In no way is the civilian government and military doing this by themselves. They are being supported by a large swath of Burmese Buddhists.

88% of the country is Buddhist and almost 70% are considered ethnically Burman, compared to a little more than 4% of the population that is Muslim. Buddhist nationalist organizations like the 969 movement and the Ma Ba Tha have galvanized and furthered this Buddhist populist movement. And the military is acquiescing and supporting the use of violence.

Abby: The UN recently called the situation a textbook example of ethnic cleansing. How does Buddhism relate to the violence? Is there a separation between the government and religion?

Michael: Southeast Asia governments argue they are secular. However, whether it is in Sri Lanka, Thailand, or Myanmar, there is clear evidence of preferential treatment towards Buddhists and supporting Buddhism. In the Constitution of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar, Section 361, it states “The Union recognizes special position of Buddhism as the faith professed by the great majority of the citizens of the Union.” This and other examples display a secular persuasion that is very Buddhist.

Abby: How do Buddhist nationalist groups view themselves and their goals?

Michael: The members of the 969 movement and the Ma Ba Tha feel it is important to protect the nation from “Islamization”. The way they imagine the nation, à la Benedict Anderson, is to see it as Buddhist. U Wirathu of the 969 movement has given sermons in which he begins with statements such as, “These days, whatever you do, you need to do it from a nationalist perspective. Our existence as a Burmese Buddhist nation has been threatened.” You see Buddhist monks from the 969 movement and Ma Ba Tha pushing forward policy ideas and laws, like the four laws previously mentioned, as well as defending the laws.

When the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Myanmar, Yanghee Lee critiqued the Burmese government for their support of the four laws, U Wirathu exclaimed: “We already have made public the Race Protection Laws. But this bitch kaungma, without studying it, kept on complaining about how it is against human rights… Don’t assume you are a respectable person, just because you have a position in the U.N. In our country, you are just a whore.”

The 969 movement as well as the Ma Ba Tha would self-identify as Buddhist nationalists in what they are trying to do.

Sarah: This is more an observation. As you noted earlier, most recently reports point to the displacement of over 400,000 Rohingya. And nearby in India, there is a similar-sounding growth of Hindu nationalism as well. Thus, the UN has expressed concern not only about the Rohingya in Myanmar, but the international refugee population as they may again face a nationalistic type of persecution.

Michael: Yes, and I think this is where it shows the vulnerability of the Rohingya. The Burmese government’s allegations have been that Rohingya are simply migrants who came across the Bangladeshi borders in recent years. They are visitors; they are not citizens. And the Burmese government argues that the term “Rohingya” is made up. Now, on one hand, they are partly right. The term “Rohingya” is a modern nomenclature. But on the other hand, they are absolutely incorrect about the history of Rohingya in Myanmar. We have documentation of Rohingya in Myanmar for over 150 years. Burmese Buddhist nationalists have also expressed concern that Muslims are overtaking Myanmar. While the Rakhine state had changed in its religious and ethnic demographics over the last several decades, we have not seen a change in Myanmar’s country-wide Buddhist-Muslim percentages in over three decades. It has remained relatively stable.

Recently, the Rohingya have found their way into Bangladesh, but this is a new phenomenon. Over the last several years, Rohingya have tried to flee Myanmar, but no country has provided resources to receive them. One powerful example of this is the smuggler’s ring discovered in 2015. Rohingya had been paying smugglers to take them away from Myanmar. Some smugglers would not bring them to their ultimate destinations. Instead, they would stop in remote areas of southern Thailand. The smugglers would then demand a ransom. If the smugglers were not paid, the smugglers would kill the Rohingya. A joint military task force found these mass graves of these Rohingya, who had been killed by these smugglers. This shows again the challenges of the Rohingya. Where can they go? Bangladesh was not hospitable to these individuals before, and with 400,000 refugees, their hospitality is stretched thin at present.

Featured image credit: Photo of Kutupalong Refugee Camp in Bangladesh by John Owens (VOA). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Buddhist nationalists and ethnic cleansing in Myanmar part II: the rise of religious nationalism and Islamophobia appeared first on OUPblog.

October 10, 2017

Women at work: New York City at the turn of the 20th century

New York City was rapidly expanding at the turn of the 20th century: the five boroughs had just unified, skyscrapers were going up, and the economy was booming. In the following extract from Greater Gotham, historian Mike Wallace discusses how the New York City’s flourishing economy influenced the career opportunities available to women in the early 1900s.

In the mid-nineteenth century, middle and upper-class gender ideals had prescribed that men and women occupy separate spheres of action—men running business and politics, women raising children and governing the household. These Victorian ideals were not universally adopted, much less lived up to. But as goals, they achieved a measure of acceptance, particularly among members of their own social circles, in which husbands commonly had enough wealth or income to forgo their wives’ earning power, which was in any case limited.

Over the second half of the nineteenth century, the gap between prescription and practice had grown steadily wider. Middle-class women had gained access to higher education, and then, diplomas in hand, had challenged the formal barriers that had kept the professions—medicine, law, engineering, architecture, business management, college teaching, and the ministry—as male-only preserves. Some women did pass through professional school gateways and on into careers, though ongoing masculine resistance kept their numbers in check. Women had also been contesting the double standard, revising family law, managing economic resources, building female-run institutions, and engaging in politics (despite being barred from the polls).

The twentieth century’s opening decades witnessed major developments in Gotham’s macro-economy, changes that drew vast numbers of women into the workforce. This quantitative phenomenon was of such magnitude that it wrought a qualitative transformation in the metropolitan gender order—in fact if not yet in ideology.

While women’s progress in traditionally all-male professions remained incremental, professions already coded female—notably teaching and nursing—grew rapidly, responding to the immigration-driven boom in school creation and the parallel growth of hospitals and public health care agencies. The opening up of new positions drew in large numbers of public-school-trained daughters of the Anglo, German, and Irish lower middle class.

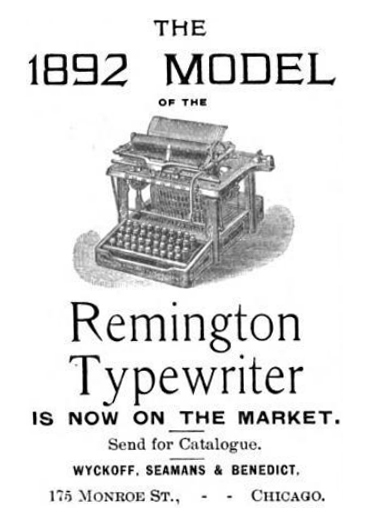

Secretaries were called “Miss Remingtons” after the typewriters they used, which helped to lock in the job category as female. Image Credit: “Remington Model 1892” by Dement, Isaac S. (January 1892). The National Stenographer. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Secretaries were called “Miss Remingtons” after the typewriters they used, which helped to lock in the job category as female. Image Credit: “Remington Model 1892” by Dement, Isaac S. (January 1892). The National Stenographer. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.In a similar way, the creation of skyscraper-headquarters by the proliferating national corporations, and the collateral mushrooming of business service industries, generated a tremendous demand for office workers. Clerical positions had hitherto been a male preserve, but the corporations opted for cheaper female labor. Male holdovers from the old regime were mollified by making them supervisors of the new army of women stenographers, typists, bookkeepers, copyists, file clerks, secretaries, receptionists, and telephone switchboard operators. Female entry into the white-collar workforce was further eased by the fact that many of the new positions were associated with new technologies, ones that hadn’t yet been sex-typed. As a result, when the corporations brought in women, men couldn’t complain their territory was being invaded.

The city’s flourishing culture industries also opened up multiple opportunities for women workers. Publishing underwent a phenomenal growth. Old family-run institutions swelled in scale, and new entrants crowded into the print marketplace, which collectively produced a torrent of books, newspapers, and magazines (including scores of labor and radical publications). This increased the demand for copy editors, illustrators, reporters, headline writers, ad writers, executive secretaries, and sometimes even literary or newspaper editors. The print boom also generated a demand for copy, and a concomitant willingness to pay freelance writers for features, short stories, poetry, and reviews. The theatrical industry blossomed, with vaudeville, movies, and the legitimate stage providing work for bevies of singers, actresses, comics, chorus girls, dancers, costumers, and makeup artists. The fashion industry created jobs for ad writers, store buyers (checking out the latest Parisian styles), designers (the Society of American Fashions was formed in 1912), editors of fashion magazines, and proprietors or employees of import firms, millinery shops, dressmaking houses, and cosmetic companies.

Sales and service positions surged with the enormous expansion of department stores and retail outlets. Female recruits flocked in, despite wages being low and work conditions difficult, because wages were somewhat higher and conditions somewhat better than in manufacturing, and pink collars commanded somewhat greater respect than did blue ones. Waitressing slots soared, too, as boardinghouses (which had served meals) gave way to rooming houses (no meals, no kitchenettes), sending throngs through the doors of lunchroom chains (Child’s, Dennett’s, Horn and Hardart). These spread rapidly throughout the city, relying on waitresses rather than the traditional (and better paid) waiters.

Huge numbers labored in the manufacturing sector—by 1910, 27 percent of New York State’s industrial labor force was female. Women were especially prominent in the garment industry, but many others held down light assembly and operative jobs—artificial-flower making, box making, confectionary dipping, bookbinding—a response to steeply rising demand for consumer goods.

The transfer of household tasks (baking bread) to commercial concerns (mammoth bread factories) continued apace. Functions coded as wife-like, such as cleaning, were increasingly provided at an industrial level. Steam laundries hired women to wash and iron for private households and commercial-scale enterprises such as hotels. Charwomen scrubbed floors in offices and theaters, work that was arduous and ill paid. And sex in the patriarchal household was supplemented by professional sex workers housed in apartments and hotels.

The one occupational stratum that shriveled was live-in maids, another instance of the exodus of labor from the home. The percentage of New York City women wage-earners engaged in paid household labor (servants and laundresses) dropped from 32.7 percent in 1900 to 12.9 in 1920. In 1900 there were 141 servants and 22 laundresses per 1,000 Gotham families; by 1920 the numbers had shrunk to 66 and 8. Given the plethora of new employment opportunities, white women were able to flee domestic servanthood, which they found degrading (subject to petty tyranny and sexual harassment) and constraining (leaving them with virtually no time of their own). Second-generation Irish, German, and Scandinavian girls refused to follow in the footsteps of their first-generation forbears, for whom service had been an acceptable entry-level job. Immigrant Jewish, Polish, and Italian women were equally disinclined to don a maid’s uniform. Black women, given their drastically narrower range of employment opportunities, perforce occupied a steadily increasing share of domestic labor’s steadily declining ranks. A complement of servants became the prerogative of wealthy families, while middle-class women, for the first time in generations, were forced to do the bulk of their own housework, and raise children without full-time help.

Featured image credit: Heatherbloom Petticoats, electric sign, n.d. (Image No. AAA0109, Outdoor Advertising Association of America Digital Collection, Duke University).

The post Women at work: New York City at the turn of the 20th century appeared first on OUPblog.

Cognitive biases and the implications of Big Data

Big Data analytics have become pervasive in today’s economy. While they produce countless novelties for businesses and consumers, they have led to increasing concerns about privacy, behavioral manipulations, and even job losses.

But the handling of vast quantities of data is anything but new. Since the 1960s, efforts have been made to devise new ways to administer increasing volumes of information stored by corporations and public organizations. Today, Big Data systems are no longer just employed to deal with large amounts of data but are utilized primarily to predict individual behavior. The actual potential of Big Data therefore lies in its underlying science: the ability to target individuals’ cognitive biases to home in on previously unobservable private attitudes and beliefs.

To illustrate, consider that when someone is shown the last two digits of their social security number and is then asked to value the absolute price of an item, say, a bottle of wine, the anchor point of their social security number will influence their valuation of this item. This same valuation is then tempered by the person’s own understanding of relative value. An ordinary bottle of wine would thus not be valued as much as a house, a car, or an exclusive bottle of champagne.

Collective anchors have a significant influence on our perceptions of value, and can also set up some apparent anomalies. A digital music album is often sold at more or less the same price as a physical one, even though there are differences in manufacturing and distribution costs. People regularly are willing to pay the relatively high price for a digital track because their initial anchor point is the price of a physical copy. Once the anchor point has been set, evaluation of value is undertaken in a way that is consistent with the initial estimate.

Mainstream responses to problems in such domains default to providing people with additional information in the form of evidence about product attributes, such as the hidden fees of credit card transactions, the performance specifications of a cell phone, or a car’s miles per gallon of gas. Recent research emphasizes that, in order to allow people to make an informed choice, they must be given information about how a product will be used, how often it will be used, how it compares to the same product of a different brand, and must receive information in accessible, attention-getting ways.

Image Credit: “World” by TheAndrasBarta. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

Image Credit: “World” by TheAndrasBarta. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.But on closer examination, the additional information hypothesis is often backwards. Receiving additional information can deepen individuals’ interpersonal disagreements and their illusions about the world around them.

In the environmental regulatory context, for example, it is conventionally presumed that individuals who are more scientifically literate and generally more proficient at processing quantitative information will be more likely to understand that climate change and its associated risks are real. But findings from cognitive psychological research demonstrate that views on climate change are governed more by social and cultural vantage points than by scientific literacy and numeracy: if individuals are given quantitative information revealing the implications of manmade climate change, and if such information is presented in a way that affects people’s social and cultural identities, the information can intensify rather than reduce disagreement on whether human activities increase or decrease global warming, depending on whether people believe in climate change or whether they are skeptical of it. Even scientifically learned individuals fail to gravitate toward the truth and will simply be more skilled at defending their original convictions.

These insights may help us understand how the law can assist citizens in getting the facts right when there is a tension between individual and collective self-interest. Such tensions exist in many parts of our societies, such as when the government tries to regulate the environment, the smooth working of capital markets in times of crises, the adverse implications of predictive algorithms, or the communication of scientific insights to the public.

For instance, when regulating the environment, it undeniably is in our collective self-interest to cope with the facts on climate change and to act accordingly. However, individuals who believe in climate change but live in a community of climate change skeptics behave rationally if they follow the skeptics in order to get along with their own social group, particularly in light of the seemingly unlikely possibility that their actions alone can make an appreciable difference on the environment.

Image Credit: “Science March 2017” by Mark Dixon. CC0 Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image Credit: “Science March 2017” by Mark Dixon. CC0 Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Or consider also the depiction in today’s political discourse of the manner in which algorithms constrict our viewpoints when they provide us with news that confirm what we already believe. Such information tends to preserve our thinking and fuels the glaring political divergence that encourages our propensity to sustain our innate creeds.

In all these contexts there are issues involved according to which particular beliefs, once they have become socially or culturally entrenched, are very difficult to change. What is more, changing such beliefs is no longer simply a matter of educating people through the provision of additional information. Instead, the solution requires an answer to the question of how, how often and to what extent we anchor upon a particular interpretation of facts.

Big Data analytics surely raise countless novel problems for lawmakers to resolve. What they are most ignorant about, however, is the ability to exploit precisely those cognitive biases that conspire to generate a distinct mental experience. The combination of these phenomena is all it takes to instigate the dynamics just described. Attempting to sort out their contradictions should be one of the central tenets of present-day legal research, and is perhaps one of the most important issues to emerge from the behavioral sciences in the past few decades.

Featured Image Credit: “System Network” by geralt and “Night Scape” by hasheem5, manipulated together. Both images : CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay .

The post Cognitive biases and the implications of Big Data appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers