Oxford University Press's Blog, page 244

June 28, 2018

An interactive view of the giraffe

Giraffes are some of the best-known, well-loved animals of the African safari. But today, many variations of these long-necked herbivores are listed as vulnerable or endangered due to habitat depletion and poaching.

This June, to celebrate our animal of the month, we bring you an interactive road-map to the anatomy of the giraffe. Click on each of the icons below to discover information from OUP’s various titles on these patchwork creatures, from hooves to horns:

Thinglink image credit: An adult female masai giraffe in the Masaai Mara national park, Kenya by Bjørn Christian Tørrissen. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons .

Feature image credit: Fighting giraffes by moviecoco568. CC by 2.0 via Flickr.

The post An interactive view of the giraffe appeared first on OUPblog.

Real sex films capture our changing relationship to sex

In 2001, the film Intimacy was screened in London as the first “real sex” film set in Britain. With a French director and international leads (the British Mark Rylance and New Zealander Kerry Fox), the film was controversial even before screening. The media conversation focussed especially on the actual sexual participation of mainstream (rather than pornographic) actors. Was “real sex” artistically necessary? Or was it simply market driven? Why was this not a form of prostitution for voyeurs? Was the well-known broadsheet film-reviewer who described Intimacy as sordid, badly acted, poorly scripted, ineptly translated, narratively muddled, with unpityingly harsh camera and wordless, nameless and violent sexuality right in his rejection of Intimacy? What is a “real sex” film historically, socially, culturally, and formally? What role does Intimacy play on- and off-screen?

Intimacy has been taken more seriously in academic (and some film-reviewing) circles, however. The strong feminist-psychoanalytical strand of film studies has explored Intimacy in the context of a broader argument that real sex film plays between the genres of pornography and art cinema in confronting risk events of our time. French cinema studies sees Intimacy as part of a particular French culture embedded in governmental tax and grant funding policy, French film schools promoting the feminization of French cinema, and the “conversational” status of film criticism across mainstream and emergent media. Cultural Studies approaches have combined textualist and social audience studies in exploring the “visceral, affective and emotional” appeal of “feel bad” films by “bringing the more difficult aspects of personal response into the open.”

Meanwhile, the sociology of risk, while not focussing on cinema, has re-thought the social context of contemporary films, which real sex films draw on and extend. Considered alongside the publication of Anthony Giddens’s The Transformation of Intimacy (1992), the film and sociological text work through similar social-historical shifts from romantic to confluent love and intimacy. In the book, Giddens coins the terms “confluent love” and “plastic sexuality” to describe sex freed from the needs of reproduction and negotiated on equal terms. Here, mutual sexual satisfaction, rather than the constant emotional closeness of an idealised romantic relationship, is key to a lasting union. And for Giddens, this kind of relationship has utopian potential, prefiguring a world beyond the traditional historical restraints of romantic love and the domestic subjugation of women.

Meanwhile, the sociology of risk, while not focussing on cinema, has re-thought the social context of contemporary films, which real sex films draw on and extend.

The film Intimacy is an especially revealing example of how an interdisciplinary approach can take this conversation qualitatively further by combining risk sociology, feminist geography of the body, French film studies (and broader film concepts of authorship, narrative, genre, mise-en-scène, spectatorship and audience), and feminist-psychoanalytical notions of desire and intimacy in exploring real sex cinema on- and off-screen.

Films showing graphic and high impact sex are not new nor are they confined to low-budget markets or European art house cinemas: think Marlon Brando in Last Tango in Paris (1972) or Peter O’Toole and Helen Mirren in Caligula (1979). The surge in real sex films such as Romance (2000), The Piano Teacher (2001), Irréversible (2002), 9 Songs (2005), Nymph()maniac (2013), and Blue is the Warmest Colour (2013) points to an historically new generation of on-screen couples that negotiate sexual identities and pursue sexual intimacy for its own sake. We see this in the feverish weekly couplings between Jay and Claire in Intimacy, in the cataclysmic affair between Adèle and Emma in the Palme d’Or Award-winning Blue is the Warmest Colour and in the covert sexual seductions between Sook-hee and Lady Hideko in the South Korean erotic thriller The Handmaiden (2016).

Both Blue is the Warmest Colour and The Handmaiden reveal the negotiation of sexual identities and the transgression of heteronormative boundaries against a local/global backdrop. In Blue is the Warmest Colour, the sexual journey of nursery teacher Adèle is mapped and embodied in her face through extreme close ups of her eating. At a family dinner, Adèle slurps, sucks, and forks spaghetti bolognese leaving traces of sauce across her mouth—an intimate orifice we see again in close up during her lovemaking with Emma. But at Emma’s family dinner the young lesbian couple is served stylish oysters and the carnalities and pleasures of food are replaced by polite conversation. In these contrasting scenes food acts as a metaphor for flesh and a signifier of class positioning, denoting power and difference.

In The Handmaiden, sexual identities are negotiated spatially in private and public settings and in the mapping of intimate and global narratives. The clandestine affair between handmaiden Sook-hee and heiress Lady Hideko develops in a private, domestic setting through everyday acts turned sensuous such as Sook-hee bathing, dressing, and reading to her mistress. But Lady Hideko hides a dark secret. At night she is summoned by her book-dealing uncle to read pornographic literature to a male audience. On a local level, these scenes contrast the negotiation of socio-sexual identities in private and public spheres—the lesbian trysts between Hideko and Sook-hee undermining the commercial space of men in an aesthetic rendering of the private is political. On a global scale, these socio-sexual relationships represent a directorial offer of a social-psychology of the relationship between Japan and Korea in the 1930s. So not only does the lesbian sex between Sook-hee and Lady Hideko challenge the public space of male sexual commerce but, as a global narrative, the “comfort girl” imperialist hetero-normative views about sexuality that were prevalent in colonial era Korea.

Depicted in these cinematic scenes are the historically located opportunities for sexual negotiation that Giddens describes in The Transformation of Intimacy, via the shift from romantic love to confluent love and plastic sexuality. Real sex films such as Intimacy, Blue is the Warmest Colour, The Piano Teacher and more recently The Handmaiden, revealing actual, graphic, and high impact sex not only give us insight into the transformation of intimacy on our cinema screens—but also the transformation of intimacy both in our own bedrooms and the global context.

Featured image credit: love american style by frankieleon. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Real sex films capture our changing relationship to sex appeared first on OUPblog.

Five critical concerns facing modern economics

Due to the nature of globalization and the interconnectedness of modern human society, the discipline of economics touches on other areas of study such as politics, environmentalism, and international relations. This is especially true for the tumultuous times in which we live. From the role of women in leadership positions to the uncertainty surrounding a higher minimum wage to the growth of populism in the Western world, we’ve excerpted five thought-provoking chapters that address central problems facing the field of economics today.

Have women made gains in the makeup of corporate leadership?

Although the highest ranks of corporate hierarchies remain dominated by men, the growth rate in female representation among corporate leaders in recent decades has been stunning, especially when considered as a proportion of the baseline levels. Between 1997 and 2009, the share of S&P 1500 board seats held by women nearly doubled (from 7.6 percent), the share of top executive positions held by women increased by 86 percent (from 3.2 percent), and the female share of CEOs increased by a factor of six (from less than 1 percent). And these gains immediately followed a near tripling of the female share among top executives over the preceding five-year period. These remarkable recent gains for women in corporate leadership are part of a broader set of female gains in the labor market that has spanned the past sixty or more years; they are particularly related to women’s increasing entry into nontraditional occupations since the 1970s. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, women made up 39.2 percent of workers in the occupational category for “managers” in 2015; this rate is lower than their overall participation in the labor market, but substantially higher than their share of top positions. – Amalia R. Miller

What are the employment effects of minimum wage?

Perhaps the economic factor of most importance in thinking about the effects of much higher minimum wages, and one that may inform the literature more generally, is the question of how the “bite” of the minimum wage—that is, how much the minimum wage binds—affects the estimated employment effects of the minimum wage. This question has received a bit of attention, but there is considerable scope for progress. One indirect approach to this question is a 1992 study, which estimated the effects of the minimum wage in Puerto Rico, a US territory that is bound by the US federal minimum wage but has much lower wage levels, and hence where the minimum wage has much more bite. The study reported very large aggregate employment effects and particularly adverse effects on low-wage industries, consistent with stronger disemployment effects where the minimum wage binds strongly. This evidence was revisited in another study in 1995, which concluded that evidence of disemployment effects was fragile. – David Neumark

President Bill Clinton signing the North American Free Trade Agreement into Law, November 1993. Executive Office of the President of the United States, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

President Bill Clinton signing the North American Free Trade Agreement into Law, November 1993. Executive Office of the President of the United States, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

How important is free trade to the global economy?

The most highly developed examples of regional trade agreements are the treaties establishing the European Union, the only regional trade area that is itself a member of the World Trade Organization (WTO). Regional trade agreements vary greatly. Some are free trade areas, which eliminate tariffs and import quotas between participating members. Other regional trade areas are more integrated and are referred to as customs unions because they combine a free trade area with a common external tariff and trade policy. Several significant regional trade areas include the free trade areas established by the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), the Caribbean Community (CARICOM and the nineteen states that comprise the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA), among others. – Aoife O’Donoghue

Is economic populism a result of austerity or globalization?

Global capitalism faces turbulent times. Advanced capitalist countries have lived through a harsh transition from the financial crash of 2008 to a period of secular stagnation in the context of rising inequality and social divides. This shift in macro regimes was largely unexpected by policymakers and the influential “economics profession”—the latter being in urgent need of conceptual renewal, realism, and more enlightened social policy concerns. The last three decades have been characterized by recurrent financial crises, complex cycles of economic activity, rising concentration of incomes and wealth, and systematic attacks against the welfare state and social protection policies. The political consequences of this state of affairs in countries with stable, mature democracies are still unfolding but look worrisome. Political parties and social movements with xenophobic, anti-migrant, anti-labor, and nationalist agendas are making strides in several European countries, and in the United States, a similar rhetoric has been adopted by billionaire-cum-politician Donald Trump that has resonated with groups of the American population in the 2016 presidential election and beyond. – Andres Solimano

A black plastic flag with a fleur-de-lis and the words “Refusons l’austérité” in French (“Refuse Austerity”, in English) commonly used in 2015-2016 at anti-austerity demonstrations in Quebec is planted in the snow near the Square-Victoria metro station in Montreal on 3 February 2016. Exile on Ontario St, CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

A black plastic flag with a fleur-de-lis and the words “Refusons l’austérité” in French (“Refuse Austerity”, in English) commonly used in 2015-2016 at anti-austerity demonstrations in Quebec is planted in the snow near the Square-Victoria metro station in Montreal on 3 February 2016. Exile on Ontario St, CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.How will the changing environment affect economic growth?

Widespread recognition that human actions are a driving force in planetary geological systems has ignited interest across the discipline in the social, political, and economic dimensions of global change. For economic geography, the onset of the Anthropocene raises foundational questions about drivers of regional growth, spatial differences in regional economic performance, and regional responses to stresses and shocks. There is a need to come to new theoretical understandings of the role of the changing material environment for the economy. How will gradual deterioration of environmental baselines affect regional economic growth and development trajectories? In what ways will adaptation responses to climatic and environmental stresses, such as out-migration from inundated or drought-prone areas, affect wages and housing markets? There remains a pressing need for attention to regional impacts and vulnerabilities in non-coastal contexts, areas that depend on climate-sensitive ecosystem services, high-value manufacturing and service sectors, and informal economies. There is also a need for further investigation of climate impacts on regional labour markets and spatial inequalities, of intersectional and relational dimensions of economic vulnerability, and of the production and performance of vulnerability in a variety of regional contexts. – Robin Leichenko

Featured Image credit: Container ship. CC0 via pixabay .

The post Five critical concerns facing modern economics appeared first on OUPblog.

Top attributes that prove you’re already an entrepreneur

Time and again I’ve heard musicians express some variation of the following sentiment: “I guess entrepreneurship is fine for some folks, but that’s not me. I’m a musician, not an entrepreneur.” The thing is, most folks who say this don’t really understand what it means to “be an entrepreneur.” Most likely they see it as something that is, at best, incompatible with being an artist; at worst, an opposition to our artistry.

But that’s simply not the case—and here are five attributes for your consideration.

1. Collaboration

There are few things more central to the life of a musician than collaboration. We do it constantly, whether it’s in rehearsal, during a performance, working with a composer, team-teaching a class, or dividing up the administrative tasks of our chamber group amongst its members. To be a musician is to be a natural collaborator.

Collaboration is also a central piece to being an entrepreneur; the multi-faceted nature of entrepreneurial action requires a team. For the musician who feels ill-equipped to wear the “entrepreneur” label, perhaps you can start getting over your unease by simply identifying as a “collaborator.”

2. Problem-solving

Musicians are constantly solving problems. That troublesome passage needs to be mastered. You’re performing in an unfamiliar space with an unflattering acoustic. There is virtually no end to the range of problems that musicians are faced with, which means that we get very good at troubleshooting and coming up with solutions on the fly. Sometimes those solutions may require a new or novel approach to the problem, such that over time we accumulate a rich repertoire of tricks to get us over the obstacles we encounter.

Entrepreneurs are also constantly in problem-solving mode. Part of that is because entrepreneurial ventures, in whatever form they take, have so many moving parts. There’s always something. Rather than being simply reactive, entrepreneurial problem-solving is proactive: observing the world around them with an eye for unmet needs or existing products or services that could be done better or more effectively. Being natural problem-solvers within their musical practice makes proactive problem-solving an easy step for musicians.

3. Iteration

Hard on the heels of problem-solving comes another important entrepreneurial attribute shared by musicians: that of repeated iterations of something before success is unlocked. This one is a natural for musicians: we’re iterating all the time. It’s how we master our own technique and develop our interpretations. It’s what we do when one plan to promote a concert doesn’t work – we try something else. Iteration is absolutely central to what it means to be a professional musician.

Entrepreneurial iteration is no different. Very few entrepreneurial ventures end up looking exactly like what was envisioned at the beginning of the process. As a product or service is developed, shared with potential customers, improved upon, introduced into the marketplace, reviewed by customers, and so forth, things usually change—sometimes a lot! But entrepreneurs understand that to get something right, repeated iterations are required; they neither throw something out after one try nor stubbornly stick to the same thing in the face of failure. They keep working on it until it’s where it needs to be. Doesn’t that sound a lot like what we do as musicians?

For musician-entrepreneurs, the trick is to take that empathy and employ it not just in our artistic practice but in all other aspects of how we conceive and implement our music.

4. Empathy

Entrepreneurship is a process by which value is unlocked for something by meeting needs in the marketplace. In order to do this well, one must first identify what unmet needs might exist; then one must identify the best way to meet those needs. Neither of these things can be done effectively without looking at the situation through the eyes of the customer. And that’s what entrepreneurs and design thinkers mean by the term “empathy.” In order to understand what someone needs and how that need can be satisfied, one must have empathy for the needs and sensibilities of the person you’re trying to reach. Without empathy, you’re just guessing blindly.

The same thing goes for musicians. Talk to any performer who is known for their “stage presence” or the compelling way they seem to connect to their audience, and they will all tell you the same thing: they have a deep and abiding desire to reach their audience on an intimate, personal level. They recognize that technique and artistry, even the music itself, are but tools for creating a bond with the audience, to give them an experience that will live on within them long after the performance is over. This is the empathy inherent in all great performers.

For musician-entrepreneurs, the trick is to take that empathy and employ it not just in our artistic practice but in all other aspects of how we conceive and implement our music.

5. Tenacity

There’s one universal truth about being an entrepreneur, and that’s that it takes hard work and perseverance in the face of setbacks and failure. Sound familiar? Who of us musicians can’t relate to hours spent in the practice room or the composing desk? Who of us can’t relate to the failed audition or the grant rejection or a particularly rough coaching session? Musicians know how to persevere; we literally could not advance to a high level of professionalism if we didn’t.

The real challenge for musicians is that being tenacious with one’s music-making can be draining enough; now I have to become a tenacious entrepreneur, too?

Well, yes. I can’t sugar-coat this one. It’s hard and it’s not for everyone. But that’s true regardless of whether or not one applies the label of “entrepreneur” to themselves. That’s just the nature of being a musician these days, even for those of us who are lucky enough to have full-time jobs in academia or in an orchestra. But that’s precisely why this is an attribute that can help us as entrepreneurs: we understand how to be tenacious, how to be resilient.

And so there we have it! “I’m a musician, not an entrepreneur.” Perhaps now you can see it’s possible to be both?

Featured image credit: “Time” by Alex Lehner. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Top attributes that prove you’re already an entrepreneur appeared first on OUPblog.

June 27, 2018

Full of fear: really dreadful

Fear is a basic emotion in all living creatures, because it makes them recognize and avoid danger. It is therefore no wonder that so many words for it have been coined. Language can describe fear by registering the physical reaction to it, for instance, shaking and trembling (quite a few words for “fear” in the Indo-European languages belong here) or trying to flee from the source of danger, as in Greek phobós, known from the suffix –phobe and all kinds of phobias (phébomai “I fear; I flee from”; its Russian cognate beg– designates only “running”). Russian boiu(s’) “I am afraid” is related to German beben “to tremble.” If Engl. bow “to bend” is akin to Latin fugere “to flee,” as in fugue, fugitive, refuge, and so forth (Old Engl. būgan has also been attested with this sense), then perhaps the initial meaning of this verb was “to cower in fear.” Or the word for “fear” can concentrate on some change in the person’s appearance. Thus, appall means (literally) “to make pale.” The ancient root of horrible (and horror) is easy to see in Latin horrēre “to stand on end” (said of hair). In a slightly different form, we recognize this root in hirsute.

Shaking in his shoes. Image credit: “Man Scared Frits Fear Shelter Leader Boss” by PublicDomainPictures. CC0 via Pixabay.

Shaking in his shoes. Image credit: “Man Scared Frits Fear Shelter Leader Boss” by PublicDomainPictures. CC0 via Pixabay.Last time (20 June 2018), I mentioned the pair start and startle. To be sure, not every word for “jumping” is connected with fear. Most of them aren’t. Consider jump itself, spring, leap, bound, and hop (all of them of questionable or unknown origin). Yet the connection between leaving one’s place and fright, fear, or apprehension is old and natural. German entsetzen means “to horrify” (add to it the adjective entsetzlich “abominable”; ent– is a prefix, and setzen is “to set,” the causative of sitzen “to sit”: on causative verbs also see the previous post). The reference must have been to unseating one, to the movement toward (or away from?) the place where one sits. Purely for entertainment’s sake, I may add that, according to what is said in the Old Icelandic Saga of the Sworn Brothers, a valiant man has a small heart, because such a heart contains less blood, and a bleeding heart bespeaks fear. Such a small heart beat in the breast of the hero Thorgeir (depending on the edition, you will find this passage at the end of Chapter 17 or 19).

From the etymological point of view, one of the most enigmatic words for “fear” is dread. Yet the oldest forms of the verb dread are well-known. Old English had a- and on-dræden “to fear greatly” (with long æ). Its congeners have also been recorded, but only in Old High German and Old Saxon, that is, in West Germanic, to the exclusion of Gothic and Old Norse. The word seems to have an obvious prefix, and, at first sight, should be divided into on– or and–dræd (-en is the ending of the infinitive), but this root has no cognates (or at least no certain cognates) and, if examined in isolation, means nothing. That is why it has been suggested that initially the word was divided into ond– and –ræden. With time, that division might have been forgotten, and the verb lost a wrong first syllable. By the way, all the recorded cognates of the Old English verb also exist only with prefixes, so that the verb must have been like German ent–setzen, cited above.

Hirsute but fearless. Image credit: “Orang Utan Monkey Ape Red Cute Hair Lazy” by Free-Photos. CC0 via Pixabay.

Hirsute but fearless. Image credit: “Orang Utan Monkey Ape Red Cute Hair Lazy” by Free-Photos. CC0 via Pixabay.Examples of such “mistakes” are many. In English, misdivision often involves n. For instance, nickname goes back to eke-name, that is, “an additional name” (eke, as in eke out), but the word was, not unexpectedly, often used with the indefinite article an. As a result, an ekename became a nekename and finally degenerated into the meaningless nickname. Many words have acquired their initial n as a consequence of this process, while adder, apron, and umpire have lost their initial n, which was taken for the last sound of the indefinite article. English speakers do not doubt that outrage is out + rage; yet its French etymon outrage has the root outr– “beyond” and the suffix –age, as in plumage and footage. In professional books, this process of misdivision is called rebracketing or metanalysis.

Thus, there are two etymologies of dread. Those who deal with the root dread say that the word’s past is beyond reconstruction. This verdict appears in numerous authoritative dictionaries. Some attempts to save this root from obscurity have of course been made, the last time in an excellent article by Helen Adolf (1947), to which I owe several examples in this post. However, I don’t think that her rescue operation was successful. (Helen Adolf, who lived to be almost 103 years old, was an outstanding person, and I am sorry I never met her.) Earlier (1907), the famous Norwegian philologist Alf Torp offered a clever hypothesis, but it required an inadmissible phonetic trick and found no support.

Between 1907 and 1947, an attack on dread was made by the American Francis A. Wood, and his proposal found favor (to use a solemn style) with two other distinguished scholars, but Wood compared the Germanic word with an equally, if not more, obscure Greek one and thus broke the golden rule of etymology: “Never expect a word of unknown origin to shed light on another opaque word. The result will always be wrong.” Outside dictionaries, dread has not been discussed too often (my database contains only nine items, not all of them of equal value). The most recent of them was written by Alfred Bammesberger (1977), who, however, missed Adolf’s work. As far as I can judge, no one has suggested that dread is a word borrowed from some non-Indo-European substrate (on this issue see again the previous post).

A man with a big body and a small heart. Image credit: Eric the Red by Arngrímur Jónsson. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

A man with a big body and a small heart. Image credit: Eric the Red by Arngrímur Jónsson. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.It was the great and incomparable Jacob Grimm who observed that perhaps ondræde has the prefix ond-. In this case, a fully transparent root appears: we still have it in German raten “to advise” and Engl. read, which in the past had the same meaning (also, “think, etc.”). It may be useful to explain what etc., above, means. These are some of the glosses of the Old English verb: “persuade; consult, discuss, design; decide; rule; possess; arrange; equip; guess; explain; put in order.” “Put in order” is probably the initial meaning of this verb, but to summarize its senses and the senses of its Old Icelandic cognate ráða is not much easier than to give an overview of Modern Engl. get.

However, Grimm saw a few serious obstacles to such a seemingly excellent suggestion, and preferred to stay with a word “of unknown origin.” These difficulties have been explained away (not explained!), and there is no certainty that we know the origin of dread. Bammesberger argued for the division ond-ræden or rather resuscitated the arguments of his distant predecessor Alois Pogatscher (a researcher whose name says nothing to non-specialists). If ræden is the root of the old word, then, with its prefix, it meant something like “make one lose one’s composure.”

This man-of-war is a dreadnought. It has no heart and knows no dread. Image credit: USS New York (BB-34) Underway at high speed, 29 May 1915. Photograph from the Bureau of Ships Collection in the U.S. National Archives. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

This man-of-war is a dreadnought. It has no heart and knows no dread. Image credit: USS New York (BB-34) Underway at high speed, 29 May 1915. Photograph from the Bureau of Ships Collection in the U.S. National Archives. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.I occasionally refer to The Universal Dictionary of the English Language by Henry Cecil Wyld. It is a first-rate dictionary with very useful etymologies, though at present few people consult them. Even Bammesberger did not expect to find anything of use in it. Yet this is what Wyld wrote, among other things, in the entry dread: “The most probable explanation is that the word is a very old West Germanic compound ond-, and-, & Germanic ræd, ‘council, advice’ &c. Old Engl. ondræden, then, would be ond-ræden; compare Old Saxon an- and and–drādan, & Old High German int–rāten, ‘to fear’, originally ‘to set the mind against; compare Modern German entraten, ‘to do without’. The final -d of the prefix was, as it were, detached, and prefixed to ræd, whence the later formation of –drædan. Middle Engl. drēden.” (The abbreviations have been expanded; æ is long throughout.) No doubt, Wyld knew his Pogatscher. Etymologies are offered, rejected, forgotten, and revived. It is a story of the eternal return.

At present, the vowel in dread is short. Shortening occurred rather regularly in monosyllables, especially before d, as in bread, head, good, and the like (the process goes back to early Modern English; our archaic spelling still reminds us of the length long gone). Nothing to be afraid of here: vowels are like humans, and, when they cannot lengthen, they usually shorten.

Featured Image: Fear saves lives. Featured Image Credit: “Cheetah Gazelle Hunting Running Chasing Cat” by jc112203. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Full of fear: really dreadful appeared first on OUPblog.

Bridging partisan divides over scientific issues

The current era in the Western hemisphere is marked by growing public distrust of “intellectual elites.” The present US administration openly disregards, or even suppresses, relevant scientific input to policy formulation. Research results that appear to conflict with deeply held political or religious beliefs, such as those on climate change or Big Bang cosmology, exacerbate already strong partisan divisions.

That’s the bad news. But there’s good news, as well. Periodic surveys of American attitudes, published by the National Science Board, show public trust in scientific leaders holding steady over the past four decades, while trust in leaders from other sectors (medicine, education, television, the press) has significantly deteriorated. In these surveys, about 90% of respondents express “a great deal of confidence” or “some confidence” in scientific leaders. In other surveys, a majority of respondents believed scientists were more knowledgeable and impartial, and therefore should play a greater role than elected officials, business leaders or religious leaders in policy decisions about climate change, stem cell research, genetically modified food, and nuclear power.

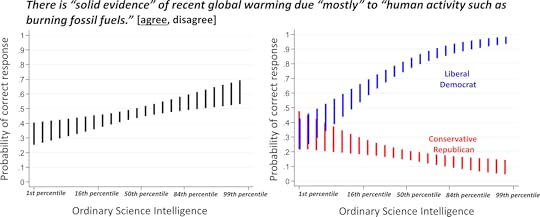

Scientists need to reinforce this reservoir of trust by listening and communicating with integrity, clarity in distinguishing fact from speculation, and fairness in representing arguments for and against alternative views. But that trust is a weaker determining factor for public attitudes than political or religious identification. Polling surveys offer guidance about how to educate the public on controversial scientific topics in the light of existing partisan divides. The challenge is illustrated starkly for the case of climate science by results in the figure below from a study by Kahan. Kahan’s and similar surveys show the partisan divide on the existence and causes of global warming growing much stronger as general scientific literacy increases. The polarization grows presumably because better-educated individuals are more skilled at finding or offering arguments that appear to confirm their pre-existing biases, even if those favored arguments misrepresent the underlying science.

Image credit: The fraction of respondents who agree with the statement above the figure, as a function of their performance on questions covering general science knowledge on non-controversial subjects. The left frame shows the aggregate response, while the right frame is subdivided by self-identified political identification of the respondents. By D.M. Kahan, Advances in Political Psychology 36(S1), 1 (2015). © 2015, John Wiley and Sons.

Image credit: The fraction of respondents who agree with the statement above the figure, as a function of their performance on questions covering general science knowledge on non-controversial subjects. The left frame shows the aggregate response, while the right frame is subdivided by self-identified political identification of the respondents. By D.M. Kahan, Advances in Political Psychology 36(S1), 1 (2015). © 2015, John Wiley and Sons.Exposure to yet more research results is unlikely to sway scientific opinions among the most polarized individuals. There is, however, a broad spectrum of opinion revealed in recent surveys of American attitudes toward climate change, carried out by groups from Yale and George Mason Universities. Those surveys find that more than 70% of the public have attitudes falling between two extremes labeled as “alarmed” (convinced of global warming and engaged to act on it) and “dismissive” (rejecting the phenomenon and strongly opposing mitigating action). Respondents with attitudes between these extremes, subdivided further into four groups (“concerned,” “cautious,” “disengaged,” and “doubtful”), are more ambivalent or currently less engaged in their views about climate change.

Educational efforts to bridge partisan divides on controversial scientific issues are best targeted at individuals in such middle segments of the populace. A productive approach should emphasize the following three components of such education.

1) Emphasize the degree of consensus among scientists actively working in the field. Various surveys have identified perceptions of scientific consensus on climate change as a key “gateway belief,” influencing other opinions about the issue and support for policy action. While surveys of climate scientists and peer-reviewed research papers systematically indicate that about 97% of the most knowledgeable scientists agree that the global climate is changing, with human activity as a major cause, only c.10% of Americans correctly estimate the level of consensus as “greater than 90%.” In a recent study, van der Linden and colleagues found that “increasing public perceptions of the scientific consensus causes a significant increase in the belief that climate change is (a) happening, (b) human-caused and (c) a worrisome problem. In turn, changes in these key beliefs lead to increased support for public action. … In fact, the consensus message had a larger influence on Republican respondents.”

2) Improve education and communication about the scientific method and scientific reasoning, emphasizing how scientists know what they know. Scientific literacy in surveys discussed above has generally been measured by the number of correct answers to general scientific knowledge questions on non-controversial subjects. Other surveys have tried instead to measure “scientific reasoning ability” via questions regarding how to evaluate scientific evidence. These surveys find that higher scores on the scientific reasoning scale are a better predictor than “scientific literacy” for individual’s acceptance of the scientific consensus on vaccines, genetically modified foods, and human evolution, though not on climate change or the Big Bang. On the latter subjects, polarization gets “baked in” with increasing age, and is driven in large part by organized groups providing cherry-picked or doctored information to cast doubt on the scientific consensus. It is important for future policy discussions to train students effectively to appreciate scientific reasoning and to provide resources to help them recognize the standard tools of science deniers and the differences between solid science and pseudoscience.

3) Emphasize current impacts of long-term problems, as well as promising mitigating actions. In competition with a wide array of pressing issues, the public expresses less concern about problems they judge to be distant or not amenable to viable solutions. On climate change it is important to stress serious impacts already being felt, aided by actuarial surveys that clearly document the steadily growing frequency over the past several decades of extreme weather events correlated with warming global temperatures and sea level rise. Another scientific issue largely ignored by the public, that of evolving bacterial resistance to antibiotics, is projected to cause 10 million deaths and US$100 trillion globally per year by 2050 if left unaddressed. The public needs to be educated about current effects and causes: in the U.S. alone, the Centers for Disease Control estimates that currently at least 2 million people annually battle, and at least 23,000 die from, bacterial infections now resistant to one or more antibiotics, and that 50% of all antibiotics prescribed in the U.S. are unwarranted. On both climate change and antibiotic resistance issues, there are mitigating actions individuals can take, and others they can lobby for, to help ameliorate the problem. Education about such actions tends to increase public engagement.

Featured image credit: Capitol at Dusk 2 by Martin Falbisoner. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Bridging partisan divides over scientific issues appeared first on OUPblog.

Basic goods as basic rights

If we were to try summarizing the many statements on human rights within the United Nations system, it might be as follows: basic goods are basic rights. True, there was an old approach to human rights that focused exclusively on “negative” political rights and cast doubt on “positive” subsistence rights. For example, it has been argued that we should not focus on economic or social rights because this would distract attention from political rights. This distinction, however, was forcibly shown to be illogical by political philosopher Henry Shue in his book Basic Rights (Princeton University Press, 1997).

As demonstrated by Shue, and as common sense suggests, even “negative” political rights require positive action in the form of the provision of human security services, legal services, and judicial services. Further, it is impossible for individuals to effectively exercise political rights when severely deprived of subsistence goods. Starkly put, there are no functioning political rights for the prematurely dead.

Shue defined basic rights as those rights that must be fulfilled so that other rights can be enjoyed. So being able to escape severe but preventable disease would be a basic right in that it would preclude the individual with the disease from effectively exercising his or her rights. Shue included both security rights and subsistence rights as two central categories of basic rights. Importantly, these two categories mirror “freedom from fear” and “freedom from want” that underpin the emerging notion of human security. The bottom line is that basic rights exist and require positive action for their fulfillment.

Basic rights are fulfilled (and human security provided) through the provision of basic goods, those goods and services that meet objective human needs. Basic goods include nutritious food, clean water, sanitation, health services, education services, housing, electricity, and human security services. Since basic good deprivations can have dramatic impacts on the well-being of those disadvantaged, such deprivations are violations of basic rights. As it turns out, however, basic goods deprivations are globally widespread.

Basic goods include nutritious food, clean water, sanitation, health services, education services, housing, electricity, and human security services.

Approximately 800 million people suffer from chronic hunger in the sense that they are not well nourished enough for an active life.

More than 700 million people do not have access to an improved drinking-water source.

Approximately 2.4 billion individuals do not have access to clean and safe toilets, and nearly 1 billon individuals practice open defecation.

Approximately 6 million infants and children die each year, largely due to preventable causes.

Approximately 250 million of the 650 primary school-age children have not mastered basic literacy and numeracy, and there are more than 750 million illiterate adults.

A much-quoted but unverifiable statistic is that at least 1 billion people lack access to adequate housing, with approximately 100 million of these being homeless.

Approximately 1.1 billion people live without access to electricity.

Half a million people die each year as a result of armed violence.

The imperative to address these deprivations has strong support within existing human rights language. The 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights addresses basic goods provision in Articles 25 and 26 on standards of living, and these considerations are reiterated in the 1966 International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights. Added to these was the 2010 United Nations General Assembly Resolution on the Human Rights to Water and Sanitation.

Identification of these violations of basic rights does not automatically lead to their rectification. Indeed, as stated by Henry Shue, “A proclamation may or may not be an initial step toward the fulfillment of the rights listed. It is frequently the substitute of the promise in the place of the fulfillment.” Actual fulfillment of basic rights requires provision, but the provision processes involved are often ignored in philosophical considerations, or largely assumed away by technological optimists. But ensuring basic rights requires that we delve into the sticky basic goods provision issues on a case-by-case basis.

Such careful consideration offers few rules-of-thumb. While in some cases, we can rely on bottom-of-the-pyramid, private provision, in others, the involvement of government in conditional cash transfer systems are critical. Sometimes technological change is important, as in the case of small-scale solar photovoltaics, lithium-ion batteries, and LED lighting. In other cases such as sanitation, technology does not seem to be the hold-up. This messiness is unavoidable.

To reiterate, basic goods are basic rights. Fulfilling these rights is one of the most important policy goals for global development policy. Existing language within the United Nations system supports this goal. Fulfillment of the goal requires careful thought and commitment to approaching development policy with fresh eyes, as well as a keen focus on critical provisioning processes and the economic, political, and technological constraints holding them back.

Featured image credit: Kids water by Abigail Keenan. Public domain via Unsplash.

The post Basic goods as basic rights appeared first on OUPblog.

June 26, 2018

Drenched in words: LGBTQ poets from US history

John F. Kennedy stated that “When power narrows the areas of man’s concern, poetry reminds him of the richness and diversity of his existence. When power corrupts, poetry cleanses.” Poetry attempts to reclaim awareness of the world through language, an entirely human construct that can only be pushed so far but one that is pushed repeatedly and necessarily in order to articulate what it means to be human. Throughout American history, LGBTQ poets have explored myriad themes including identity, sexuality, and historical and political landscapes, in order to comprehend and chronicle human experience.

We collated some of America’s most revered and influential LGBTQ poets to depict the evolution of America’s poetic writing and assert Walt Whitman’s claim that “The United States themselves are essentially the greatest poem.”

Hart Crane (1899–1932)

With hopes of being a poet from his earliest adolescence, Crane was an avid student of the emerging schools of modernism. He stated that a “poem is at least a stab at the truth.” His most famous work, The Bridge, was first published in 1930. The poem navigates through American history, returning the reader to contemporary New York with the Brooklyn Bridge becoming the mystical realization of the New Atlantis. Through his commitment to his poetic vision, influencing some of the most prominent writers in history, he has come to occupy an enduring place in the American literary canon.

Pauli Murray (1910–1985)

Born Anna Pauline Murray, Murray later changed her name to Pauli. Murray entered law school “with the single-minded intention of destroying Jim Crow,” and graduated cum laude and first in her class. After being rejected by Harvard because of her gender, she obtained a graduate degree at the University of California at Berkeley and produced a thesis titled “The Right to Equal Opportunity in Employment.” Murray achieved prominence as a lawyer, poet, educator, and minister, and worked throughout her life to promote the rights of workers, African Americans, and women.

Image credit: Allen Ginsberg by Ludwig Urning. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: Allen Ginsberg by Ludwig Urning. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Walt Whitman (1819–1892)

Instead of writing poetry in the confines of conventional meter and rhythm, Whitman’s poetry reflected the patterns and pace of Americans and American life. Best known for his collection Leaves of Grass (1855), Whitman focused the poetic eye, for the first time, on ordinary people as they pursued their daily lives, opening with a celebration of the poet as representative of all humankind. Whitman’s central theme is that the body stands equal to the soul and that all its individual parts are worthy of expression and celebration. Whitman is considered one of the greatest American poets and a key figure in the influence over 20th century American poetry.

Elizabeth Bishop (1911–1979)

Bishop entered the Vassar College class of 1934 and began an underground literary magazine, Con Spirito, a more socially conscious publication than the legitimate Vassar Review. At Vassar, Bishop came to see poetry as an available, viable vocation for women. Her first collection North and South introduces the themes central to Bishop’s poetry: geography and landscape, human connection with the natural world, questions of knowledge and perception, and the (in)ability of form to control chaos. Her second collection, A Cold Spring, won the 1956 Pulitzer Prize and positioned Bishop as “one of the best poets alive.”

Allen Ginsberg (1926–1997)

As a freshman at Columbia University, Ginsberg became part of a diverse (now legendary) group named the “Beat Generation”, referring to their shared sense of exhaustion and feelings of rebellion against the general conformity, hypocrisy, and materialism of wider society. Ginsberg felt that the poet’s duty was to bring a visionary consciousness of reality to his readers. Howl and Other Poems was published in 1956, for which a number of individuals were charged for publishing and selling work considered obscene. The American Civil Liberties Union defended Ginsberg’s poem in a highly publicized obscenity trial, which concluded when the Judge ruled that the work had redeeming social value.

H. D. (1886–1961)

Hilda Doolittle, who later established herself as “H.D.”, was sensitive to the defining nature of her gender. This became symbolic of the struggle for her own identity that she faced both as a woman and writer throughout her life. She became a patient of Sigmund Freud during the 1930s in order to understand and express her bisexuality, writing, and spiritual experiences. She became an icon for both the LGBT and feminist movements when her writings were rediscovered during the 1970s and 1980s. H.D. is now regarded as a major and versatile poet, whose exploration of her identity as both woman and artist is central to an understanding of literary modernism.

Langston Hughes (1902– 1967)

Hughes entered Lincoln University in 1926 as an already award-winning poet. For developing artistic and aesthetic sensibilities, Hughes credited those people he admiringly named the “low-down folks.” He praised lower classes for their pride and individuality, stating “they accept what beauty is their own without question.” The variety and quality of his achievements in various genres gave him a place of central importance in 20th century American literature. His vision was both experimental and traditional, rejecting artificial middle-class values, and promoted emotional and intellectual freedom. He also demonstrated that African Americans could support themselves with their art both financially and spiritually.

Image credit: Digitally restored black and white daguerrotype of Emily Dickinson, c. early 1847. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: Digitally restored black and white daguerrotype of Emily Dickinson, c. early 1847. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Pat Parker (1944–1989)

In high school, Parker joined the staff of the local African American newspaper and became the first female junior editor of her school newspaper. Growing up in the segregated South, Parker encountered racism regularly and the civil rights, women’s liberation, and Black Power movements politicized her. Throughout the 1970s, Parker performed in lesbian-feminist community spaces, where audiences responded enthusiastically to her writing that explored key themes of racial-sexual equality and struggles for justice. She helped to define womyn’s culture (feminist culture focused female independence) in the Bay Area and across the United States.

Emily Dickinson (1830–1886)

Dickinson’s poetry is remarkable for its emotional, intellectual energy and extreme distillation. In form, everything is tightly condensed, with words and phrases set off by dashes and brief stanzas. Yet in theme and tone her poems grasp for the sublime in their expression of human extremities. Stylistic tendencies such as punctuation that withholds traditional markers, a willingness to leave poems unfinished, and even the distinctive amount of white space left on the page force readers to involve themselves directly in her poetry in a way that places distance while encouraging an exceptional degree of intimacy. Emily Dickinson stands as one of America’s preeminent poets of the 19th century and perhaps of America’s entire literary tradition.

Featured Image credit: Monochrome Brooklyn Bridge. Brendan Church, Public Domain via Unsplash .

The post Drenched in words: LGBTQ poets from US history appeared first on OUPblog.

Reluctant migrants in Italy

The brutal murder of six African immigrants in the streets of the northern province of Macerata in February 2018 brought to mind an earlier history of black bodies in Italy. In April 1943, the fascist Ministry of Italian Africa transported a group of over fifty Africans to Macerata from Naples. The diverse group of men, women, and children from Ethiopia and Eritrea first traveled to Italy in April 1940 as part of the Mostra Triennale d’Oltremare—an exhibition space on the outskirts of Naples designed to celebrate the expanding Italian empire. One of the many components of the exhibit included a reproduction of a “native village” where visitors could see indigenous people performing a version of “traditional” life for Italian spectators. Intending for the group to remain in Naples for only six months, exhibition officials housed them in poorly insulated barracks. But Italy’s entry into the Second World War in June 1940 led to the sudden closure of the exhibition and the entrapment of its East African inhabitants. Separated from their homes, this group remained under the forced protection and control of the Ministry of Italian Africa until the end of the war. When Allied bombings of Naples intensified in early 1943, Ministry officials transported the African inhabitants of the exhibition northward to a dilapidated villa on the outskirts of Treia, Macerata.

The man who confessed to the 2018 murders, Luca Traini, made no secret of his racist and anti-immigrant motivations; he reportedly gave a fascist salute when he was arrested and has long documented ties to the anti-immigrant political party Lega Nord. His actions highlight the continued vulnerability of black lives in Italy. Traini and others like him see black bodies as a direct challenge to Italian identity; fascist officials also saw the presence of the African inhabitants of the Mostra d’Oltremare as a threat to racial purity. A contingent from the Italian African Police—equal in number to the group of African inhabitants—was stationed at the exhibition space in 1940 to maintain a state of constant surveillance. Barbed wire surrounded the barracks where the group was housed, and any attempt to escape was met with imprisonment. The conditions in the encampment pushed a number of people to alcoholism and mental illness.

In the context of the fascist regime, the fear of racial contamination also inspired the Ministry of Italian Africa to bring two women—Becchelé Mulorki (or Muluserki) and Abegaz Menen—from Eritrea to live in the exhibit and service the “physical needs” of the over fifty black men of the Italian African Police assigned to the exhibit’s outpost. These two women had no idea they would be expected to act as prostitutes when they boarded a boat for Naples. Denied the stipends provided to the other inhabitants, they were forced to sell their bodies for 150 lire per month, supplied by the General Command of the Italian African Police, and whatever small amounts the ascari were willing to pay for sex. Ministry officials denied their requests to enter a state-regulated prostitution house due to the “obvious” racial risks of coming into contact with white clientele. In the social and economic hierarchy that developed in the exhibition, these two women were undoubtedly at the bottom. Both spent months at a time in hospital from the brutal effects of their sexual servitude.

Today, immigration is transforming Italy to an increasingly diverse country. In many places, immigrants are filling necessary jobs abandoned by a generation of Italians who fled the countryside in pursuit of higher-paying careers in Italian urban centers and abroad. Italian politicians and pundits stoke fears by depicting the arrival of non-white immigrants as an urgent threat with the potential to undermine Italian whiteness. Corriere della Sera, the Italian newspaper with the highest circulation, characterized the increase in (primarily African) immigration following the 2011 collapse of the Qaddafi regime in Libya as “an invasion without precedent.” The reaction of the Italian government—under Berlusconi and the variety of center-left politicians who have followed him—has been to develop a network of Centers of Identification and Expulsion (Cie). These Centers house a wide variety of people living in the vulnerable margins of Italian society: recent immigrants; the children of immigrants who grew up in Italy, but lack papers; Roma people prevented from gaining proper documentation of citizenship due to a bureaucratic quagmire; a large number of East African women forced into a system of sexual slavery. Much like the inhabitants of the Mostra d’Oltremare, they exist in a state of legal limbo. They are not considered detainees or prisoners; Italian officials refer to them as “guests.” Paradoxically, the designation leaves them with fewer rights than they would have as prisoners. Many “guests” spend months in the Centers waiting for a decision about their fate with no clear recourse to legal action. In other ways, the Centers bear a striking resemblance to prisons. The spaces are surrounded by tall fences and the movements of the “guests” are tightly controlled. Isolated from their friends and family on the outside world, mental and physical illness is a constant problem.

For historians, it is imperative that we demonstrate the longer historical context behind this strict control over the movement of bodies coded as non-white in the Italian peninsula. Fears of an immigrant “invasion” differ little from the fears of racial contamination in the 1930s and 40s. Postwar Italy notoriously embraced what is known as the myth of Italia brava gente—a sense that Italians were less racially virulent than their Nazi German allies. This perception allowed the postwar Italian republic to paper over the effects of Italy’s 1938 race laws and the violence of Italian colonial rule in Africa. Grappling with the longer history of Italian perceptions of race is necessary for a reconceptualization of immigration, race, and national identity today. The historical record informs a moral imperative of alleviating the suffering of people living on the margins of Italian society.

Featured image: Mostra d’Oltremare by Johnnyrotten. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Reluctant migrants in Italy appeared first on OUPblog.

The scary truth about night terrors

Do you know what it’s like to stand near, but helplessly apart, from your child while he screams out in apparent horror during the night? I do. I did it almost nightly for months. It wasn’t necessary.

My six-year-old son is one of many children who experienced night terrors. Like most of these children, he has a relative who experienced night terrors as well–I had them when I was a child. Night terrors are not bad dreams or nightmares. As horrible as they are, nightmares dissolve with light and with the calming presence of a caring parent. Children typically experience nightmares late in the night, and can usually recall specific details. These dreams can be prevented, possibly, by avoiding certain images, stories, or food items. This is an inconvenience, not a problem. Night terrors are a different beast.

Your child doesn’t awaken because of– or during– a night terror, although their eyes may be wide open. You cannot sooth, or calm, or reassure a child experiencing one. Children typically experience night terrors early in the night, and have no recall of specific details. The standard medical advice suggests that you should stand by, watch your child suffer, listen to them scream, and only inhibit their thrashing when it might cause physical harm. In essence, your parenting style should be ultra-hands off at exactly the time you are emotionally driven to be fully hands on. And while I have felt tortured by this, I am more tormented by the secret belief that my son has subconsciously internalized being abandoned during these moments.

And I mean subconsciously internalizing the event, because experts believe that children will not remember night terrors, and thus bear no lingering scars. Indeed, my recollection of night terrors is not of the event, but rather finally waking to find my parents and/or siblings working to calm me down. But we live at a time when we are learning that the experiences felt by one’s grandmother can, through epigenetics, influence how we respond to the World. I worry that these moments my son experienced may have lasting effect.

These moments, we’ve now learned, happen within the first few hours of sleep as individuals arouse from slow-wave sleep (that is, deep non-REM sleep) and transition into lighter REM sleep. Night terrors appear to be more common in children who are overtired, sick, or stressed, or in kids taking new medicines, or in those away from home. In all cases they present as a non-responsive, terrified child.

Since most children do not experience them, we’d have to consider night terrors an extreme outcome of the cultural practice of nighttime separation.

Children tend to grow out of night terrors, with only a small percentage experiencing them into their adolescence. Some children experience them with such frequency, however, that professionals have suggested interventions. A common treatment for repeated night terrors is to prescribe antidepressants. A new approach to treating them is scheduled awakenings, whereby children are ‘jostled’ during the approximate time when they would be transitioning between sleep states, thus disrupting the path towards a night terror. Because my son experienced terrors 5-6 nights a week for months, we tried the latter strategy.

My wife and I would put my son to bed, wait for him to fall asleep, and then after 50-minutes stand in the hallway and trigger a vibrating device inserted between his mattress and box spring. This form of sleep disruption rarely worked. It’s when I joked one night that the sleep disruption was working better on us, that I had an epic faceplant moment: my son didn’t suffer from abnormal sleep patterns.

He was suffering from an unnatural sleeping situation. I should have known better! I teach about the health consequences of living in evolutionarily novel environments. When in our evolutionary history would it have made sense for young children to sleep apart from their parents? If it makes evolutionary sense, why are we essentially the only primate to do it? And if it doesn’t make sense, why doesn’t it? I’ll posit an answer–sleeping apart from your parents was dangerous. Indeed, being separated from family in the dark is exceptionally dangerous. It’s not long ago that humans were predators and prey.

We spend all day long keeping track of our children, rarely letting them out of visual contact. Then at the end of the day, we separate them from the family, place them in a dark and quiet room, and leave them. From an evolutionary perspective, they should be terrified. We expect more terrors from kids who are stressed or displaced from their family, I just don’t think we’ve recognized that our culture has led us to stress and displace our children every night.

We started sleeping with my son the next night. We didn’t need to stay the whole night, but found that he fell asleep earlier than he had previously. He also reached for us after sleeping for about an hour, around that time he would have been transitioning to lighter REM sleep. At that point, if the one who was with him was awake, my wife or I could return to our bedroom. I often slept the night. His terrors ceased, and his younger brother–who has only known co-sleeping–has never experienced one.

This personal anecdote led me to believe that night terrors are inflicted on our children as a result of novel cultural practices. If correct, since most children do not experience them, we’d have to consider night terrors an extreme outcome of the cultural practice of nighttime separation.

But if this is an extreme outcome, what lesser outcomes are we missing? I believe co-sleeping with children (1+ years old) is likely to decrease the prevalence of night terrors – and of any potential ‘lesser outcomes’ – by recovering an evolutionarily beneficial method of nighttime parenting.

Featured image credit: mattress bed pillow sleep relax by congerdesign. Public domain via Pixabay .

The post The scary truth about night terrors appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers