Oxford University Press's Blog, page 241

July 14, 2018

A misnomered species: 5 facts you should know about orcas

For centuries, orcas have accrued a myriad of different names: Orcinus orca (which translates roughly as “demon from hell”), asesinas de ballena (whale killers), Delphinus orca, grampus, thrasher, blackfish, killer whale, to name a few.

The names of these animals are overtly violent, but what do we actually know about the alleged “demons from hell”? This month, we want look at the facts about killer whales, and debunk the centuries-old mystery and fear surrounding orcas.

1. Orca sightings were first recorded in 79 CE

Gaius Plinius Secundus, better known as Pliny the Elder, was the first person to have recorded a description of killer whales. Based upon Pliny’s description of the creature, the orca seemed to have instilled fear into him. Penned in his encyclopedic Naturalis Historia, Pliny painted orcas as “an enormous mass of flesh armed with teeth,” as well as “and with its teeth tears its young, or else attacks the [balaena] females which have just brought forth, and, indeed, while they are still pregnant.” Moreover, Pliny describes the orca “as though the sea were infuriate against itself.” Pliny originally bore witness to Orcinus orca in 50 CE, when an orca had been drawn in by a ship from Gaul to the harbor of Ostia, Rome’s port city. The Romans, no stranger to watching animals die, attacked the killer whale until it succumbed, though not without sinking at least one Roman vessel beforehand. The earliest recordings of orcas are rooted in violent depiction, stemming centuries of fear from human observers. However, these “killer whales” are unlikely to attack humans.

2. Orcas are maritime carnivores

The diet of an orca specifically revolves around the ecosystem of a given pod, but the primary and typical diet of an orca consists of salmon, seals, porpoises, sea lions, and minke whales. Other regional pods prey on squids, octopi, otters, rays, dolphins, sharks, baleen whales, as well as turtles, seabirds, and even penguins. The orca hunting strategy is incredibly complex, given the size, high intelligence, and sociability of pods, allowing orcas to dominate the top of the marine food chain.

Image credit: “Orca Lofoten Islands Dusk Seascape” by Seaurchin. CC0 via Pixabay.

Image credit: “Orca Lofoten Islands Dusk Seascape” by Seaurchin. CC0 via Pixabay.3. Orcas are cetaceans

What is a cetacean? Cetacea is an order of marine animals that comprises whales, dolphins, and porpoises. Cetaceans have hairless bodies, no hind limbs, a horizontal tail fin, and a blowhole on top of their head for breathing. While cetaceans live in the water, they are also mammals, and thereby must resurface for air. Orcas were also given the categorization in 1758 of Delphinus orca, literally translating to “demon dolphin.” Of the more than seventy species of toothed whales, they are second in size only to the sperm whale—full-grown males can reach near thirty feet in length and almost twenty thousand pounds.

4. Orcas are acoustic creatures

The anatomy of an orca is incredibly complex and sophisticated. Orcas are equipped with strong underwater eyesight, but moreover, orcas are acoustic. By manipulating air in nasal passages below their blowholes, they generate a wide range of sound waves. Orcas have biosonar, providing a natural sonar system common amongst cetaceans. Their biosonar enables orca pods to map their surroundings, locate prey, and even “see” inside the bodies of other animals—a cetacean version of ultrasound. Through biosonar, orca pods are able to establish their own dialect through the variety of whistles and pulsed calls unique to regional pods. These distinctive dialects frame orca identity, not unlike the role of language and accent in marking human ethnicity.

5. Orca culture follows a matriline

Female orcas reach sexual maturity around the age of nine and reproduce well into their forties with an average gestation period of approximately seventeen months, followed by a similar nursing period. Female orcas only reproduce every four to five years, allowing deep bonds between mother and calf. In contrast to many mammalian species, female orcas can live long after menopause and often assume leadership roles within their pod. These leadership roles take the form of a matriline, in which older females within the pod hold authority. These matrilines, in turn, form the building blocks of larger pods—some of which are remarkably stable. With no fixed residence, the only home individual orcas know is their pod, which structures foraging, sleeping, breeding, and belonging, often for their entire lives. Any separation of even a singular orca from a pod yields deep mourning and dismay amongst the highly intelligent and socially-interwoven pod, for the orca pod is a familial unit, perpetually in motion.

The post A misnomered species: 5 facts you should know about orcas appeared first on OUPblog.

July 13, 2018

Where do our teeth come from? [excerpt]

We all know that we start with baby teeth which fall out and are replaced with adult teeth, but do we really know why? Where do our baby teeth come from in the first place? The science of tooth formation is wrapped up in genetics, and much of it is yet to be understood, but our journey from being toothless babies to adults with a fine set of pearly whites is fascinating. This adapted extract below from the Oxford Handbook of Integrated Dental Biosciences highlights how our teeth form, why they erupt through our gums when they do, what causes teething pains, and when baby teeth should begin to appear.

The early embryo starts as a ball of undifferentiated cells, then organizes into a 3-layered disc:

• Ectoderm—is the origin of skin and infolds to form the nervous system, sensory cells (of eyes, nose, etc), and dental enamel

• Mesoderm—is the origin of connective tissue, bone, muscle, kidneys, gonads, and spleen

• Endoderm—is the origin of epithelial lining of gut and respiratory systems, the parenchyma of liver and pancreas

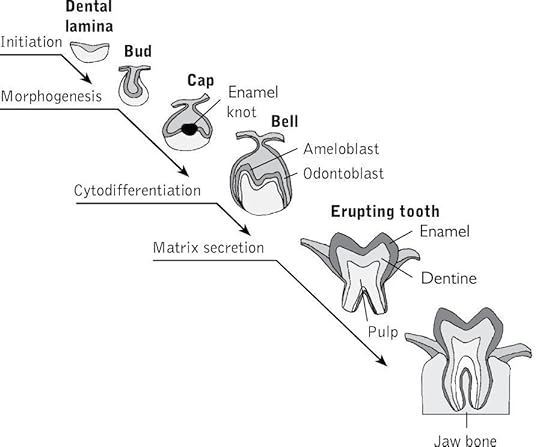

The process of tooth formation starts at 5–6 weeks in utero with the formation of the dental lamina. This is a thickening of the ectoderm extending from the lining of the primitive oral cavity down into the underlying ectomesenchyme. Within this dental lamina, focal bud-like thickenings map out the sites of the future teeth, 20 for the first set of teeth, and later 32 for the permanent teeth. These ectoderm buds, together with a surrounding aggregation of ectomesenchymal cells, form the earliest stage of the tooth germ. There are 6 stages in which the crown of the tooth is formed, which you can see in the diagram. The outer shape of the crown is fully formed before root development starts.

Reproduced from Scully, C. Oxford Handbook of Applied Dental Sciences (2003), with permission from Oxford University Press.

Reproduced from Scully, C. Oxford Handbook of Applied Dental Sciences (2003), with permission from Oxford University Press.Eruption brings the tooth from its developmental position into its functional position. This mechanism is not fully understood yet. The dental follicle is crucial (it later becomes the periodontal ligament). It seems the tooth is pushed rather than pulled – there does not seem to be a traction force. The dental follicle evolves to produce a complete crown, then the transforming growth hormone is released which attracts osteoclasts and macrophages which cause bone remodelling around the crown. Next, the overlying soft tissue breaks down releasing enamel matrix protein. This may be part of teething – rhinitis, fever, and inflammation of soft tissue around the erupting crown. Growth and thyroid hormones moderate the rate of eruption.

The mechanisms of eruption are not fully understood but factors potentially contributing to eruption are as follows.

• Root formation

Root growth is often happening at the same time as active eruption but seems to follow eruption rather than cause it, e.g. rootless teeth will erupt, and teeth with a closed apex can still erupt.

• Tissue fluid hydrostatic pressure

This mechanism is seen as highly likely. Minute changes in tooth position are synchronized to the pulse and there is a pattern to eruption across the day. Changes in tissue pressure have been recorded corresponding to eruption activity, increased vascularity, and expanding of blood vessels – producing a swollen ground substance.

• Bone remodelling

Bone is certainly remodelled during tooth eruption (e.g. bone tissues can be resorbed locally to make room for the developing clinical crown) but it does not seem to be a major motive force.

• Periodontal ligament

Fibroblasts migrate along the periodontal ligament at the same rate as teeth erupt but this is thought to be a passive process and there seems to be no traction force here.

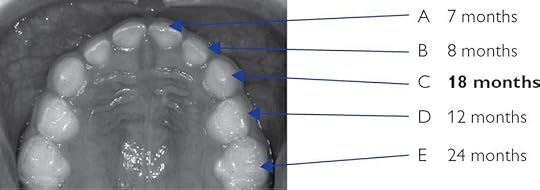

Tooth eruption dates vary from person to person, and up to 1 year either side of the standard dates should be allowed. See the below diagram for the standard dates for the eruption of baby teeth. Normally, primary teeth fall out and new teeth erupt more-or-less simultaneously, so any 1-sided delay, beyond a few months, should be investigated. Causes for delay are most commonly local obstruction by a supernumerary or impacted tooth or because there is insufficient space for it to erupt into.

Hugh Devlin and Rebecca Craven, used with permission.

Hugh Devlin and Rebecca Craven, used with permission.Even after the tooth is fully erupted there continues to be an adaptive process of remodelling bone and cementum which ensures that teeth remain in contact and vertical. Forces on teeth, whether continuous or intermittent, during eruption can slow, stop or reverse eruption or redirect its path.

Featured image credit: Monkey shouting in cave by Asa Rodger. Public Domain via Unsplash .

The post Where do our teeth come from? [excerpt] appeared first on OUPblog.

A Q&A with composer Will Todd

British composer and pianist Will Todd has worked at the Royal Opera House, the Lincoln Center in New York, London’s Barbican, and with Welsh National Opera, award-winning choirs The Sixteen, the BBC Singers, and Tenebrae. His music is valued for its melodic intensity and harmonic skill, which often incorporates jazz colours. We caught up with Will to ask him a few questions about his inspiration and approach to composition.

What does a typical day in your life look like?

So varied – and I love that! Could be anything from 8 hours in the composing shed at the end of my garden, to travelling in the UK or abroad to do performances, rehearsals, workshops or meetings, to cooking for the family, or doing admin and accounts… #nodayisthesame! If it’s a composing at home day, I try to be at my desk early and work till midday and I always start by playing something (anything!) on the piano.

What do you like to do when you’re not composing?

Films, cooking, reading, comedy, chatting.

What is the most difficult piece you’ve ever written and why?

Probably my Clarinet Concerto for Emma Johnson. It was a challenge to get the jazz elements she wanted integrated into a symphonic texture whilst keeping a good balance between clarinet and orchestra. Got there in the end though!

What is the most exciting composition you’ve ever worked on and why?

Very hard to answer—a definite highlight would be the 2012 commission for the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee Thanksgiving Service at St Pauls. I wrote The Call of Wisdom for the specially formed youth choir, and the whole thing was very exciting.

Tell us about one of your proudest moments.

Seeing my daughter on stage at ENO in a performance of Carmen! In my own music I was very proud of the fundraising Mass in Blue performance/workshop/singing day in 2015 in aid of Rainbow Trust where we raised £20,000.

What is your inspiration/what motivates you to compose?

I think the desire to have the music have a good effect on the listeners and performers—to create something magical.

How do you prepare yourself to begin a new piece?

I think a lot and play the piano a lot. But the text (if it’s a words piece) is one of the most important starting points.

How do you begin to approach a new commission?

I think about structure, and where it is being performed, and who is performing, before anything else.

Do you treat your work as a 9-5 job, or compose when you feel inspired?

Normally the former, but there are times when I have to rush out of the house to my composing shed to jot down an idea.

What does success within a composition look like to you–how do you know when to stop editing a piece and that you’ve reached the end?

I think, over time, you know when you have got a piece ‘right.’ It’s a hard balance to strike and it is easy to keep on fiddling with things; but in my experience, my first ideas are the best so I try not to change them too much.

Which of your pieces holds the most significance to you?

Mass in Blue has a lot of significance. Also Christus Est Stella.

What or who has influenced you the most in your life as a composer?

My mum made embroideries which were always hanging around the house in various stages of completion. This taught me so much about process. I also listened to a broad range of music in my childhood, from orchestral classics through to rock music and jazz. Nothing was off limits and that’s still the case. I love the operas of Puccini, the symphonies of Sibelius and Shostakovitch, and lots of choral music.

Have the challenges you face as a composer changed over the course of your career?

I think you feel the pressure of ‘the market’ more as you progress because you have a better understanding of what does and doesn’t work.

What is the last piece of music you listened to?

Didn’t We Almost Have It All by Whitney Houston.

What might you have been if you weren’t a composer?

In my dreams a cricketer!

What made you want to be a composer?

I think a general obsession with listening to music and trying to work out how to do it.

Is there an instrument you wish you had learnt to play, and do you have a favourite work for that instrument?

I love the trumpet and the music I love particularly is the jazz playing of people like Dizzy Gillespie and Miles Davis.

Which pieces would appear on your desert island playlist?

Mary’s Lullaby by John Rutter, Giacomo Puccini’s opera La Bohème, and Jean Sibelius’ 7th Symphony.

How has your music changed throughout your career?

I’m not sure I can tell; in general, it’s got shorter and better structured. I also don’t worry so much about what other people think.

What was the last concert you attended?

One in which I was performing Mass in Blue.

Which composer, dead or alive, would you most like to meet?

Puccini.

What’s your guilty pleasure listening?

All of it! But particularly the Carpenters!

Featured image: Cricketers on the Green by Junk151 via Pixabay .

The post A Q&A with composer Will Todd appeared first on OUPblog.

July 11, 2018

The gleaner continues his journey: June 2018

My discussion of idioms does not rest on a solid foundation. In examining the etymology of a word, I can rely on the evidence of numerous dictionaries and on my rich database. The linguists interested in the origin of idiomatic phrases wade through a swamp. My database of such phrases is rather rich, but the notes I have amassed are usually “opinions,” whose value is hard to assess. Sometimes the origin of a word is at stake. Then I find myself “at home.” For example, Walter Skeat and his coauthor and occasional opponent A. L. Mayhew disagreed about the etymology of the exclamation dear me. But the polemic centered on the origin of dear (Mayhew seems to have been right), and the arguments were familiar to me. However, if I read a note on the occasion that allegedly gave rise to the phrase between the devil and the deep sea, I cannot check the reliability of the source. I am sure Stephen Goranson is right, and perhaps the story is partly apocryphal, but, there may be a grain of truth in it. As for deep, rather than deep blue sea, the rhyme is perhaps wrong, but the alliteration devil/ deep saves the whole. Incidentally, knowing nothing about the circumstances in which the phrase was coined, I suspected its authenticity just because of the alliteration: the whole struck me as too good to be true. Whatever the original comment was, it must have been given a few last touches before it became proverbial (see Etymology Gleanings for June 2018).

Pilgarlic

No doubt, pulling garlic, while bemoaning one’s fate, cannot be an expected agricultural activity (see the post on the amorous pilgarlic). But, if the phrase was current as an idiom, I see no objection to it. Likewise, if we read that some event got a person’s goat or ruffled his feathers, we hardly conjure up the image of an irate horned animal or of a pinioned individual. But I must confess with great embarrassment that I cannot find the comment in which the authenticity of Chaucer’s phrase was called into question. When and where was it posted?

Now pillock. This is a widely-known British word for a despicable idiot. From a semantic point of view a pillock is the same as a jerk. And, yes, there is every reason to believe that it goes back to Middle and early Modern Engl. pillicock “penis; boy.” The OED refers to Norwegian dialectal pill “penis,” which, I am sure, is the same word as pille “pillar,” its apocopated form (so the reference is to an erect penis). The word may perhaps be a loan from northern English dialects, but there is no certainty. If pill is a variant of peel (as discussed in the post on pilgarlic) and an occasional synonym of pull, peel a cock acquires the familiar sense! Inserted i and a are common, as in handicraft, cock-a-doodle-doo, and the like (I discussed such words in my etymological dictionary in the entries ragamuffin and cockney; posts on those two words also exist).

Unidiomatic ruffled feathers. Image credit: “Stork Black Stork Bird Feathered Race Nature” by zoosnow. CC0 via Pixabay.

Unidiomatic ruffled feathers. Image credit: “Stork Black Stork Bird Feathered Race Nature” by zoosnow. CC0 via Pixabay.Some math

The origin of number and arithmetic is not problematic. The ultimate source of arithmetic is Greek “the art of counting” (tékhnē, as in technique), but the word came to English from Old French, where it sounded as arismetique, which, through folk etymology, yielded ars metrica. In the sixteenth century, arithmetic was made to conform to its Greek source, with th substituted for s. Number goes back to Anglo-Norman and Old French, but ultimately to Latin. Old French already had the excrescent b, and Modern French retained it (nombre). Rather probably, Latin numerus is related to Greek némein “to deal out, distribute.”

With regard to handful, most of my eight informants preferred to use a singular verb with it. Yes, number does take the plural (a number of people were present), but nothing follows from this fact about handful, especially in American English, in which collective nouns are usually followed by singular verbs. The problem is that American speakers may say a handful of judges are not because handful is a collective noun but because they tend to make the verb agree with the noun closest to it. We’ll never know why the journalist used the plural verb in the sentence I quoted, and at the moment, this is the least of our concerns. To make my point quite clear, here is a recent quotation from Newt Gingrich: “We learned that every one of those agencies have interest groups that desperately want to survive.” (Nowadays, I read newspapers mainly for linguistic purposes.) The mood of the tales are gloomy will remain a mistake until we agree that such concord is correct (as simple as that). “It may be wrong,” a student once said to me, “but it flows.” And it certainly does.

Greek and English words

Returning to this issue is probably a waste of time, but let me repeat: etymology is based on the achievements of historical linguistics. Comparing look-alikes was the method practiced in the eighteenth century and earlier, and there is no need to return to it. I’ll confine myself to one example. Engl. comb does not resemble Russian zub. Yet they are related to each other and to Greek gómphos. This conclusion is not a postscript to an imaginative story but the result of a study of old forms. There still are people who attempt to trace all words of a given language to one source. The gamut goes all the way from Hebrew to Scottish Gaelic, with Greek, Latin, and (deplorably) Russian included. Ernest Weekley called such enthusiasts monomaniacs. Language history allows us to connect dissimilar-looking words. Thus, related to Old Engl. comb was the verb cemban (from kambjan). Someone who was “uncombed” is now “unkempt.” Without recourse to the history of English, no one would have made this connection. Let me repeat: stringing together look-alikes is a waste of time, and why should hundreds of Old English words have been borrowed from Greek, seeing that the illiterate (“preliterate”) speakers of North Sea Germanic had no contacts with the speakers of Classical Greek? As to Greek honi “horn,” I can only say that the word was not recorded in Classical Greek, so it must be recent in the modern language and, by definition, it has no old connections with Engl. horn: a mere coincidence, of which there are many, unless it is a recent borrowing from English.

The origin of fake

This is what Professor Maher wrote to me: “Old Engl. fæc is the coiled rope. A rope that is not whipped at the end comes undone…. The end of the fæc is the fag end. The primary sense of faking for sailors and hairdressers was skillful arrangement of sisal fibers and hairs. The sense ‘spurious, counterfeit, faux’ inevitably followed and far outnumbers that nautical and tonsorial uses today.” I know only Old Engl. fæc “space of time; division, interval,” but, regardless of the Old English word, I have trouble with fake, because it surfaced so extremely late (in the 19th century). Be that as it may, any attack on such a hard problem is welcome.

Two Russian digressions

Russian uzhas “terror” is indeed related to anguish and the rest, but I wonder where I found the information that uzkii “narrow” is related to it. Indeed, not in Vasmer or any dictionary, though I am sure that what I wrote was not my invention.

[image error]Kolkhoz: a masterpiece of the Soviet agitprop. Image credit: I. Mashkov, Kolkhoznitsa with pumpkins. 1930 by Administration of the Volgograd Region. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Yes, the Russian noun kolkhoz is an abbreviated compound made up of two roots: kollektivnoe khoziaistvo, that is, collective ownership or a collective economic unit (collective business, as it were); compare English words like Caltech. After the revolution, such words were coined by the dozen; some of them stayed in the language. Collective farm is the way that awkward Russian coinage was rendered in English. As to ferma “farm,” Russian seems to have borrowed it from French (and added the feminine ending a). In dictionaries, it does not predate 1837. English also took over ferme in its Romance guise, but in late Middle English, the group er was rather regularly broadened to ar; hence Berkeley (which is pronounced as Barkley in the name of Bishop Berkeley and elsewhere; compare clerk ~ Clark); Derby (= Darby), parson, an etymological doublet of person; varsity (that is, University), and many other common words, for instance, far, carve, star, tar, and farthing, in which ar goes back to er.

The spelling of mattress

Why tt and ss? Double letters are the bane of English spelling, even though some people believe we have not got enough of them. For instance, in the United States, the plural of bus very often appears as busses. Old French and Middle English had materas. Double letters in this word began to appear as early as the 16th century (OED). Possibly, after the loss (syncope) of e in the middle, tt was supposed to indicate the phonetic value of the letter a, though, as we can see from matrimony and matrix, there is no system here. The letter s was probably doubled, to make the word look more impressive (a common phenomenon in the Middle Ages and later; some scribes repeated the last letter even three times). Conclusion: join the ranks of Spelling Reformers (Carthago delenda est).

This is Cato the Elder (234- 149 BCE), a Roman senator. He never gave a speech without ending it with delenda est Carthago “Carthage should be destroyed.” He had no notion of English spelling. Image credit: Marcus Porcius Cato, der Ältere via Dr. Manuel at German Wikipedia. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

This is Cato the Elder (234- 149 BCE), a Roman senator. He never gave a speech without ending it with delenda est Carthago “Carthage should be destroyed.” He had no notion of English spelling. Image credit: Marcus Porcius Cato, der Ältere via Dr. Manuel at German Wikipedia. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.On dogs and men

A correspondent informed me that Persian folk etymology derives sag “dog” from seh–yak “one third,” because one third of the dog’s essence is human. It would have been a pity not to share this piece of information with a larger audience. I’d rather say that at least one third of the human being’s essence is canine.

Spanish wisdom

Another correspondent wrote me about a tile inscribed in Andalusian Spanish, which reads (in translation): “Lord, bless anyone who does not waste my time.” In his friend’s interpretation, it means “God give me patience with time wasters.” This sounds like a good equivalent.

Many thanks for the numerous letters and comments and forgive me for a post of inordinate length: I hope I did not waste too much of your time.

Featured Image: A handful. A collective noun? Featured Image Credit: “Strawberries Fruits Close-Up Food Fresh Hands” by Pexels. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post The gleaner continues his journey: June 2018 appeared first on OUPblog.

Brexit threatens food supplies and Ministers know it

The story on the front page of The Sunday Times on 3 June 2018 pulled no punches. Headlined “Revealed: plans for Doomsday Brexit”, it reported on leaked government papers planning for a “no deal” Brexit scenario. They warned that the port of Dover could collapse on day one of exiting the EU, with major food shortages within a few days and medicines shortages within two weeks.

It seems barely comprehensible that a democratically elected government would risk the well-being of its people in this way. Yet, the government seems in total denial. Collectively, ministers seem gripped by an unbelievable degree of optimism bias making Voltaire’s Dr Pangloss look like an incurable pessimist.

The Department for Exiting the EU described the news as “completely false”, a claim that, on past experience, was greeted with scepticism. When one of us wrote of the threat to the supply of medical isotopes from Brexit, the Department also rubbished our claims, presenting situation as under control. A subsequent Freedom of Information request confirmed that it held no papers and had conducted no meetings whatsoever on the topic.

Returning to The Sunday Times story, the journalist who wrote the story has reported that a minister in the Department had described those who leaked the documents as “spineless cowardly quislings”.

Crucially, The Sunday Times story is entirely consistent with everything else we know about Brexit. The British cabinet is still unable to agree what it wants in terms of future customs arrangements. Even if it could reach agreement, it is simply impossible to put anything other than crisis responses in place. For example, we now know that the Department of Transport is planning to turn large swathes of motorway in Kent into lorry parks.

IMG_3603 by Jason Tester Guerrilla Futures. CC-BY-ND-2.0 via Flickr.

IMG_3603 by Jason Tester Guerrilla Futures. CC-BY-ND-2.0 via Flickr.Other governments, such as the Dutch and Irish, are vastly better prepared, despite not knowing what the British actually want. The Dutch government prepared an online tool to assist its companies to examine how Brexit might impact them. In contrast, the British have concealed any plans that they might have behind a curtain of secrecy. Concerns that they are simply hiding incompetence seemed confirmed when ministers were forced to release the “sectoral analyses“, deemed so sensitive that MPs could only read them in locked rooms. When they eventually reached the public domain we saw that they contained such remarkable insights as how fishing was concentrated in coastal towns and banks were in centres of population. Unsurprisingly, other European governments have now put many of their preparations on hold.

We identified five major threats to the food supply. The first, highlighted in the leaked papers, is to imported food. The United Kingdom is far from self-sufficient in its food reduction. While the threat to imports from the rest of the European Union is obvious, what is less appreciated is that food from the rest of the world only reaches the United Kingdom because of complex trading arrangements that depend on membership of the EU. These include hundreds of trade agreements, customs clearance infrastructure in Rotterdam, and food safety inspectors from the European Food Safety Authority, active in 130 countries.

The second threat is to domestic food production, much of which depends on the labours of seasonal agricultural workers, overwhelmingly coming from the rest of the EU. Even though the United Kingdom has not yet left the EU, producers are already facing a crisis, due to a combination of the low value of the pound, meaning those workers are taking less money home, and the “hostile environment” created by the Prime Minister that, whether intentional or not, makes them feel extremely unwelcome.

The third threat Brexit presents is to food prices. Brexit supporters who claim the United Kingdom could trade easily under World Trade Organisation (WTO) terms, have been rather more silent since President Trump provided a case study on just how difficult this would be; by launching a trade war. The reality will be extremely complex. Either the United Kingdom will remove all tariffs, devastating its domestic agricultural industry, or it will impose external tariffs that increase food prices greatly. Here, it is necessary to remember that the frequent claim by Brexit supporters that the EU imposes high tariffs on products from developing countries is not true. Whatever happens, resorting to WTO terms would be catastrophic.

Logistics is the fourth threat to the food supply. This is also touched on in the leaked government papers. The British retail market is dependent on a complex network of “just-in-time” deliveries, mainly on lorries. Thousands of these lorries cross the channel or the Irish border every day. Yet, following Brexit, it is likely that only a fraction of British lorries will have permits to operate in the rest of the EU.

The final threat is probably the best recognised. This is the Irish border. Food production in Ireland is integrated across the border. So far, the British government has been incapable of coming up with any feasible solution. Indeed, its proposals, such as the recent one for a buffer zone, have become progressively more ludicrous. The problems are enormous, not least the threat from large-scale organised smuggling, leading the Gardai, or Irish police, to call for reissuing of the automatic weapons that were necessary during The Troubles.

The optimistic scenario is that, faced with recognition of the scale of the problems, the British government will seek to save face by leaving the EU, on paper, but continuing to behave as if it was an EU member for what it might call an “implementation period” but which will be, in effect, an indefinite state of limbo, as its economy slowly declines and its influence weakens. Eventually, there will be sufficient groundswell of opinion to rejoin the EU. The pessimistic one is that, perhaps by accident, the United Kingdom does crash out. In that case, as our analysis, and seemingly, the government’s own, shows, we can expect a severe humanitarian crisis, with widespread food shortages being one of the first manifestations.

Featured image credit: Shopping Cart by Michael Gaida. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Brexit threatens food supplies and Ministers know it appeared first on OUPblog.

July 10, 2018

It’s not just decline and fall anymore…

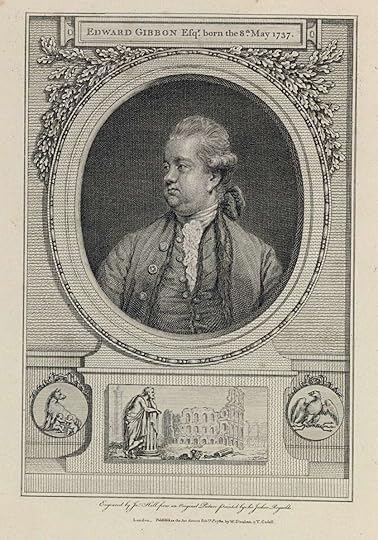

One evening in mid-October 1764, the young Edward Gibbon sat among the ruins of the Capitol at Rome. The prospect before him must have looked like a Piranesi print–bony cattle grazing on thin grass in the shade of shattered marble columns. It was then and there that he resolved to write the history of the decline and fall of Rome. For Gibbon, the half-millennium between the High Roman Empire and the Early Middle Ages, the era between the mid-3rd and mid-8th century AD which scholars now call Late Antiquity, was marked by an Awful Revolution. Gibbon thought that in the 2nd century AD the empire of Rome comprehended the fairest part of the earth and the most civilised portion of mankind. He shared the confidence of many of his contemporaries that progress was as inevitable as it was desirable; thanks to the steady advance of civilisation and rationality, no people need ever relapse into primitive uncouthness. The Awful Revolution which had caused the fall of the Roman Empire from its high point in the 2nd century was, therefore, a calamity which demanded an explanation. He found one; “I have described,” he wrote, “the triumph of barbarism and religion.”

Gibbon was far from being the first historian of Late Antiquity. The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire could never have been written without the superb scholarly spadework done by English and French scholars in the century before him—men like Henricus Valesius, historiographer to Louis XIV, and Dr. John Fell, Bishop of Oxford and refounder of the Oxford University Press (of “I do not love thee” fame). What was new for Gibbon was the belief in inexorable progress which was at odds with the fact of decline. Three and a half centuries earlier the Renaissance scholar Poggio Bracciolini had sat where Gibbon sat and studied the same prospect. He saw the ruins of Rome, he said, “prostrate and stripped of all its splendour like a gigantic rotted corpse”, but he had no sense that this was unnatural. Jam seges ubi Roma fuit—grain grows where once was Rome. Change and decay were simply indications of the cruelty of Fortune, sad but not remarkable.

Portrait frontispiece of Edward Gibbon (1737-1794): The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. W. Strahan and T. Cadell London 1780. Engraving by J. Hall after a painting by Sir John Reynolds. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Portrait frontispiece of Edward Gibbon (1737-1794): The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. W. Strahan and T. Cadell London 1780. Engraving by J. Hall after a painting by Sir John Reynolds. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.The gloomy view of Late Antiquity propounded by Gibbon combined with the pessimism of his predecessors to cast a long shadow. It is, in fact, only since the 1960s that large numbers of anglophone historians have come to expend on Late Antiquity the care and consideration they previously reserved for earlier eras of classical history, for the Glory that was Greece and the Grandeur that was Rome.

What they have found is a Roman Empire which was remarkably robust. On the Limestone Massif in northern Syria, for instance, great swathes of marginal land were being irrigated and farmed in the 6th and 7th century which were not tilled again until modern times. To be sure, from the 5th century onwards Germanic warlords destroyed the structure of Roman administration in Western Europe, and their dominance reduced the creature comforts of its population. But the Eastern Roman Empire, governed from Constantinople, continued to thrive. It codified Roman law and then codified it again. Poets continued to compose Greek epics and epigrams. The philosophers of Athens and Alexandria discussed disputed questions in natural science. Distinguished mathematicians designed the Great Church of the Holy Wisdom, once characterized as “the most interesting building in the world.”

And—something not visible in earlier eras of classical history—grass grew up between the paving stones of Greco-Roman civilisation; distinctive local cultures flourished in the provinces. Armenia acquired an alphabet and a written literature and also, in the 6th and 7th centuries, compact domed stone churches which are satisfyingly mathematical in their proportions. The uncommon common sense of Egyptian hermits was recorded in stories and sayings, the Apophthegmata Patrum, which still sell well in modern translations. Most striking of all, the Syriac language, the lingua franca of the Fertile Crescent, acquired a distinctive literature. Semitic languages, they say, are like love—the first is the worst—but the beauty of the poetry of S. Ephrem the Syrian shines through the English translations of Sebastian Brock, even for those of us who read no Syriac, while the multifarious learning cultivated from the 6th century onwards in Syriac-speaking Christian monasteries such as Qenneshre on the east bank of the Euphrates formed a vital link between Greek science and philosophy and the Arab thinkers and scholars of 9th century Iraq.

Add to all this what was going on beyond the frontiers of the Roman Empire, and a concern with the decline and fall of Roman rule in western Europe begins to seem somewhat parochial. Ethiopia and Ireland emerge into the historical record. Also, there was another whole empire to the east of the Roman frontier, that of Sasanian Persia, whose realms comprised modern Iraq as well as the Iranian plateau and territories to the east. The Rise of Islam swept away the Sasanian dynasty with astonishing rapidity, but understanding Sasanian Iran still helps greatly to elucidate the particular character of that ancient land. Some of the most important events in modern Near Eastern history happened in the 7th century AD.

Equestrian statue at Taq-e Bostan, Iran, of Khosro II in parthian armor, one of the oldest depictions of a cataphract, a form of heavy cavalry used by the Sasanid Empire. Philippe Chavin, CC BY 2.5 via Wikimedia Commons.

Equestrian statue at Taq-e Bostan, Iran, of Khosro II in parthian armor, one of the oldest depictions of a cataphract, a form of heavy cavalry used by the Sasanid Empire. Philippe Chavin, CC BY 2.5 via Wikimedia Commons.The history of Late Antiquity in fact fails to conform to preconceived patterns of progress and decline. Rather, it displays kaleidoscopic cultural diversity; the rational actor, that callow and colourless character beloved of economists, is difficult to discover. History may be servitude, history may be freedom. Perhaps it teaches nothing except that it teaches nothing—but it does present for our examination people setting about the difficult business of facing up to the forces of Nature, of believing in one God or many, of making the best of being human. In Late Antiquity, they did this in more ways than most.

Featured Image credit: Hagia Sophia (Church of the Holy Wisdom) is a former Greek Orthodox patriarchal basilica, later an imperial mosque, and now a museum in Istanbul, Turkey. brewbooks, 2006. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons .

The post It’s not just decline and fall anymore… appeared first on OUPblog.

Keeping high risk patients healthy at home

Staying on top of multiple chronic illnesses such as diabetes and heart failure can be a challenge for even the most well-resourced patient – imagine doing so while battling homelessness and schizophrenia. The result is often frequent trips to the emergency department and the hospital. This is not an uncommon scenario for patients who have co-occurring chronic conditions, mental illness, and social stressors, making them high risk for re-current hospitalizations. And, not surprisingly, many healthcare systems have started implementing programs to address the needs of these patients.

Intensive outpatient programs attempt to identify and treat high-risk patients before they need to visit a hospital. These programs typically offer care coordination, case management, social services, and around-the-clock access to clinicians. The thinking goes that spending money up front on an array of resources may prevent an even more expensive hospitalization from occurring, saving costs to the health system while keeping patients healthy at home.

Although a promising and simple idea, intensive outpatient programs have not consistently shown to improve health care outcomes or to improve costs. Experts think that failing to engage high risk patients in these programs may account for their limited success so far. Making resources available is a first step, but getting medically and socially complex patients to use them presents a greater challenge.

We reached out to a diverse group of intensive outpatient programs in Northern California to learn how front-line providers describe patient engagement in terms of their complex patient population. The participants’ vast experience illuminated how engagement of high-risk patients in intensive outpatient programs is unlike that of any other group of patients. By sitting down with nurses, physicians, care coordinators, and other providers, we sought to understand what a truly engaged patient looks like in this high-risk population.

The findings of our study are summarized in the Engagement Through CARInG Framework. The CARInG Framework categorizes engagement of high risk patients into three domains: Communications and actions to improve health; Relationships built on trust in IOCP staff; and Insight and goal-setting ability.

Intensive outpatient programs have not consistently shown to improve health care outcomes or to improve costs.

First, engaged patients communicate with providers and take actions to improve their health. Calling doctors, showing up to appointments, and picking up prescriptions are all signs of an engaged patient. Even opening the door for a visiting nurse can be a sign of engagement, and not a given among a patient population that frequently battles mental illness and immense social stressors.

Second, engagement requires relationships built on trust. As one provider explained to us: “Patients were skeptical and hesitant: ‘This is too good to be true. How are you going to do this or that?’ We just took it one day at a time and showed them, ‘We want to see you healthier and living a happy life.’”

Finally, engaged patients develop insight and the ability to set goals for their health. A patient engaged in an intensive outpatient program defines their own health goals and understands how take steps to achieve them. As one provider said: “It involves not telling the patient what they need to do but […] having the patient try to think out their own problem and their own resolution.”

The Engagement Through CARInG Framework outlines the skills, attitudes, and behaviors that comprise engagement for high-risk patients. It also demonstrates that engagement for high-risk patients contains subtlety that might not be obvious to providers unfamiliar with this population. For instance, participants in our study told us how engagement can vary amongst the three domains described above. One provider described how highly insightful patients (the third domain) can still be engaged in their care even if they struggle to take important actions to improve health (the first domain): “[Patients] are still engaged when they respond to the person they are working with and say, ‘I can’t do this right now.’ When they can name that this is not a good time for them, that really shows engagement and progress.”

There is a critical demand for effective interventions for patients with medical, social, and behavior complexity. The CARInG Framework collects and organizes the wisdom and experience of providers and care coordinators who have worked with hundreds of high risk patients. Improving engagement will undoubtedly be needed to reach the full potential of intensive outpatient programs for high-risk patients, and the CARInG framework can be used as a launching pad for interventions to improve this promising approach.

Featured image credit: Giving by Tom Parsons. Public domain via Unsplash

The post Keeping high risk patients healthy at home appeared first on OUPblog.

July 9, 2018

Stars in the telescopic eye: LVHIS and the nearby Universe

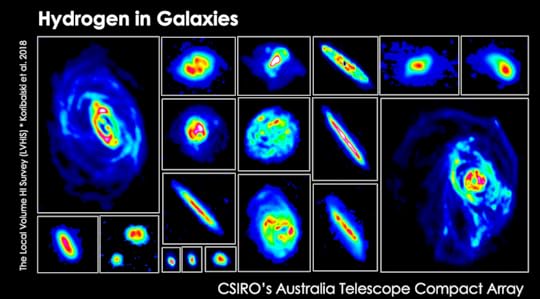

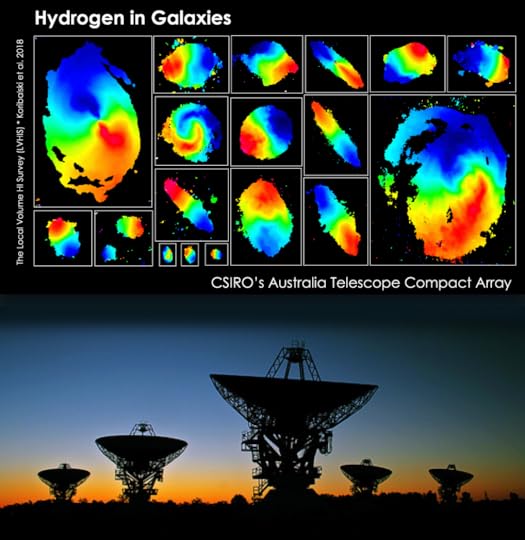

Spiral galaxies like the Milky Way and its neighbour, the Andromeda Galaxy, contain about 100 billion stars each, the light of which can be seen by eye. Also visible are small amounts of dust, typically enshrouding the sites of young star formations. What cannot be seen by the naked eye are the vast amounts of cold hydrogen gas and even larger reservoirs of dark matter. These elements of galaxy make-up are detectable only by radio telescopes.

Image credit: The Australian Square Kilometre Array Pathfinder (ASKAP) by Simon Johnston. Used with permission.

Image credit: The Australian Square Kilometre Array Pathfinder (ASKAP) by Simon Johnston. Used with permission. Understanding the distribution of cold hydrogen gas and dark matter could be central to understanding the construction of galaxies across the Universe, including our own. For the past several years, I have led a team of scientists on a research project to understand these galactic elements. We have taken deep radio observations of nearly 100 nearby galaxies, using CSIRO’s Australia Telescope Compact Array (ATCA) and combining and analysing the data this radio inferometer produced. Cold hydrogen gas is detectable at a wavelength of 21 cm, and by tuning the ATCA’s sensitive receivers to this frequency, we were able to map the distribution of hydrogen gas in each galaxy, well beyond the flat plane of dust and stars known as stellar disks.

Using the ATCA radio inferometer in this way, we have been able to not only map the location and intensity of the hydrogen gas, but also the speed at which it travels to an extremely high accuracy. Detailed analysis of each galaxy has allowed us to determine its distance, size, shape, rotational velocity, and total mass. This research discovered a veritable zoo of galaxies, from regular to highly irregular shapes: thin and fluffy discs; some sprouting extensions; tidal tails; warped outer arms; and tiny companions.

Image credit: Collage of galaxies from the Local Volume HI Survey by Bärbel Koribalski. Used with permission.

Image credit: Collage of galaxies from the Local Volume HI Survey by Bärbel Koribalski. Used with permission.The project is called LVHIS—pronounced ELVIS—which stands for Local Volume HI Survey. While the Milky Way and Andromeda Galaxy—together with about 100 small neighbours known as dwarf galaxies —make up the Local Group, the Local Volume (LV) encompasses around 1000 nearby galaxies out to a distance of 30 million light years. We chose to analyse galaxies already detected with CSIRO’s Parkes 64-m telescope (known as “The Dish”) in the HI Parkes All Sky Survey (HIPASS). Using these pre-detected galaxies allowed us to map their hydrogen structure with 20 times greater accuracy, and to derive their rotation speeds, which are important for measuring dark matter content.

Most LVHIS galaxies live in two prominent galaxy groups, known as the Sculptor Group and the Centaurus A Group. Interactions in which these group members enter each others’ gravitational fields and collide are common, and the results of this gravitational dance are best seen in cold hydrogen gas, observable by our radio telescopes at a wavelength of 21cm.

Even larger hydrogen studies are now under way with CSIRO’s Australian Square Kilometre Array Pathfinder (ASKAP), a 36-antenna radio interferometer in Western Australia. This research forms part of the WALLABY project, led by myself and Lister Staveley-Smith. Early Science with an array of 12 to 16 ASKAP dishes, each equipped with brand-new Phased-Array Feeds delivering a field of view of 30 square degrees on the sky, is starting to provide similar maps to LVHIS, but for many more galaxies and a larger volumes of space.

Image credit: Collage of galaxies from the Local Volume HI Survey by Bärbel Koribalski. Used with permission.

Image credit: Collage of galaxies from the Local Volume HI Survey by Bärbel Koribalski. Used with permission.On an even more ambitious scale, the full ASKAP HI All Sky Survey (WALLABY) is expected to get under way soon, and will detect over 500,000 galaxies and large numbers of star-less HI clouds. The latter are often tidal debris, i.e. gas removed from the outer disks of spiral galaxies by gravitational interactions between neighbours.

Underpinning this progression of ever larger and more detailed sky surveys are massive advances in innovative technologies. While the Parkes 21cm multibeam receiver allowed astronomers to survey the sky 13 times faster than previously feasible, the ATCA high-resolution interferometry provided detailed imaging. Now even larger 21cm receivers (Chequerboard Phased-Array Feeds) are deployed on ASKAP, making it a fast hydrogen survey machine and formidable pathfinder for the Square Kilometre Array (SKA).

These innovative advances in astronomy technologies provide the potential for ever greater discoveries about the galaxies inhabiting our Universe.

Featured image credit: The LH 95 star forming region of the Large Magellanic Cloud by European Space Agency (ESA/Hubble). Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Stars in the telescopic eye: LVHIS and the nearby Universe appeared first on OUPblog.

July 8, 2018

Philosopher of The Month: Maurice Merleau-Ponty [slideshow]

This July, the OUP Philosophy team honors Maurice Merleau-Ponty (1908-61) as their Philosopher of the Month. Merleau-Ponty was a French phenomenologist and together with Sartre founded the existential philosophy. His work draws on the empirical psychology, the early phenomenology of Husserl, Saussure’s structuralism as well as Heidegger’s ontology.

His most famous work Phénoménologie de la Perception (1945, Phenomenology of Perception) established Merleau-Ponty as the philosopher of the body. The body is the centre of perceptions and medium of consciousness. By this, he emphasized the way in which our experience does not form a shut-off private domain, but a way of being-in-the world in which the lived body and the perceptible world coexist internally. It is through this body-world co-existence, called intersubjectivity, that all meanings originate. Merleau-Ponty thus opposes purely scientific thinking for their explanation of human experience, and all notions of dualism such as the subject-object dualism of Cartesianism associated with Sartre’s existentialism, and the separation of the mind into the Freudian distinction of the conscious and the unconscious.

Merleau-Ponty also has profound influence in the field of aesthetics and art theory. His philosophy of painting rests on the three essays: ‘Cézanne’s Doubt’, ‘Indirect Language and the Voices of Silence’ and ‘Eye and Mind’. They examine how art and perception intertwine and how art displays the act of presenting the world in a way that is more truly representative. In his most famous essay, ‘Cézanne’s Doubt’, Merleau-Ponty offered an anti-formalist phenomenological interpretation of Cézanne’s painting. Whereas previous critical analysis of the artist tend to focus on his use of geometry, plane and form, Merleau-Ponty praised the artist for his use of colours and his ability to render visible a ‘lived’ prescientific experience of the world. Cezanne had used colors in the way that bring voluminosity and solidity to things since colours bring us closer to the world and get to ‘the heart of things’.

For more on Merleau-Ponty’s life and work, browse our interactive slideshow below:

Featured Image: The Card Player (5th version) (ca.1894-1895) by Paul Cezanne, oil on canvas, Musée d’Orsay. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Philosopher of The Month: Maurice Merleau-Ponty [slideshow] appeared first on OUPblog.

July 7, 2018

Professionalizing leadership – development

Barbara Kellerman looks at three crucial areas of learning leadership: leadership education; leadership training; and leadership development. In this third and final post, she discusses the importance of leadership development and how it is encouraged and supported lifelong.

Learning to lead – like learning to practice any profession – should consist of a certain sequence in a certain order. Like doctors and lawyers, and for that matter like preachers and teachers and truck drivers and hairdressers, leaders should first be educated, then trained, and then developed. Previously we have addressed leadership education and training. What finally is meant by leadership development? How are leaders developed – as opposed to educated or trained?

For the purposes of this discussion a single useful comparison: between adult development and leadership development. Both share similar characteristics. First, like adult development, leadership development can be fostered and nurtured by others, such as teachers and trainers. But it consists, essentially, of a journey we undertake on our own, of work we do ourselves rather than of tasks imposed on us by someone else.

Second, leadership development like adult development is a process that is internal, not external. While it implies progress of some sort – progress from one stage, level, or plateau to the next – it is not progress that can easily be measured or even detected, such as having mastered certain subject or skill.

Development further implies the passage of time. Like adult development, leadership development takes time, ideally a lifetime of acquiring experience and expertise, becoming not just smarter but wiser. Above all, development suggests a process that is continuous – ongoing and never-ending. Though development remains in some ways elusive, it is nevertheless conceived of as being expansive and extended, holistic and inclusive.

We used to think that children and adolescents “develop,” but adults do not. The notion that adults also change goes back only about fifty years. Jean Piaget, the famed twentieth century Swiss psychologist, is among the early pioneers of human development. Of course, not all adult developmentalists think similarly. Some developmentalists center on alterations that come with age, as we transition, say, from early into middle adulthood. Others focus on how we construct our lives, make meaning of our experience.. For instance, the term “identity-based leader development” refers neither to stage nor to age, but rather to experience, specifically to the experience of exercising leadership.

Never stop by Fab Lentz. Public domain via Unsplash.

Never stop by Fab Lentz. Public domain via Unsplash.What then are the implications of these theories for practice? Specifically, how should the leadership industry respond to the finding that, like adult development, leadership development implies a trajectory that continues indefinitely?

The military – which is the exception to the rule that leadership in America is taught too swiftly and superficially – provides a template. Most institutions and organizations ignore the idea that learning to lead takes time. But the military does not. Learning to lead at West Point, for example, is centered, explicitly, on the word “development.” As one of its publications, Building Capacity to Lead, makes clear, learning to lead “occurs in stages,” and involves “many of the same processes as those employed to develop more experienced adults.” In other words, the message that West Point sends is that learning to lead is a process, one that is evolutionary not revolutionary, and takes years or even decades, certainly not weeks or months. General Fred Franks, former commanding general of the Army’s Training and Doctrine Command, put it perfectly: “The longest developmental process we have in the United States Army is development of a commander. It takes less time to develop a tank – less time to develop an Apache helicopter – than it does to develop a commander. It takes anywhere from twenty-two to twenty-five years before we entrust a division of soldiers to a commander.”

The difference between how the military teaches how to lead, and how civilians teach how to lead, is enormous. The chasm is in leadership education and training – and in leadership development. Military personnel understand as civilians generally do not that leadership development takes time, and that this in turn requires an investment that is long term, not short term.

This is not exactly rocket science. Institutions of higher education, as well as corporations and other organizations that invest heavily in teaching how to lead, could easily do a better – a more serious and conscientious – job of developing leaders than they do now. And they could do so without incurring significant additional costs. Here, for example, two simple steps.

First, encourage contexts and cultures conducive to development, conducive to enabling people to learn, to grow, to evolve over time to become somehow sturdier and better than they were before. In their book, An Everyone Culture, Robert Kegan and Lisa Lahey describe companies that refuse to separate the people who make up the business from the business itself. “Their big bet on a deliberately developmental culture is rooted in the unshakeable belief that business can be an ideal context for people’s growth, evolution, and flourishing.” Put differently, investments in leadership development should always be made in tandem with investments in adult development.

Second, leadership programs should take a cue from professions such as medicine and law, which now virtually mandate continuing education. The exercise of good leadership cannot possibly be learned, not to speak of mastered, in a single stroke. In a single course or executive session or degree program–or a single anything else at a single moment in time. Among other reasons, things change. Leaders change. Followers change. Contexts change. Which is why leaders must become lifelong learners – and why every leadership program should bake into the cake of its curriculum ways of continuing to educate, train, and develop.

Of all those who stand to benefit from continuing indefinitely to change and to grow, leaders surely rank among the most important. For those of us in the leadership industry, to continue to ignore this simple truth would be a dereliction of duty.

Featured image credit: Application Business Collaboration Colleagues by rawpixel. Public domain via Pixabay .

The post Professionalizing leadership – development appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers