Oxford University Press's Blog, page 245

June 25, 2018

Martin Luther’s Polish revolution

Last year, Playmobil issued one of its best-selling and most controversial figurines yet, a three-inch Martin Luther, with quill, book, and cheerful pink plastic face. This mini-Luther celebrated the 500th anniversary of the Reformation: throughout 2017, in Germany and beyond, a flood of re-enactments, conferences, and state ceremonies remembered the Saxon monk’s opening attack on medieval Catholicism in autumn 1517. The packed “Luther Year” has now drawn to a close, but 2018 marks 500 years since the Lutheran Reformation’s arrival in the kingdom where it was to enjoy some of its most spectacular, ground-breaking early successes—Poland.

Poland has a reputation for being impeccably, historically Roman Catholic—the land of Pope John Paul II, Jesuit churches and popular folk piety. A Lutheran Poland, as part of the Protestant world, today requires some serious re-imagining of European history. Yet, however improbable it sounds, Poland has a claim to be one of the major birthplaces of the European Reformation—as scholars back in the 19th century well knew, penning thick tomes on this problem. It was the 20th century’s total wars, extreme nationalisms, and crazy-paving redrawing of borders which obscured this story from view, removing it from the familiar Reformation histories we tell, retell, and remember today.

There is no Playmobil figure (yet) of Jakub Knade, the Dominican who in 1518 cast off his friar’s habit and started to preach Luther’s message in Danzig/Gdańsk, the Polish monarchy’s principal port. He was a subject of Sigismund I, king of Poland and grand duke of Lithuania, scion of the powerful Jagiellonian dynasty. Sigismund I’s Poland stretched, in an awkward diagonal, from the Carpathians of today’s western Ukraine, to the affluent Baltic cities of Prussia.

During the reign of Sigismund I (1506-1548), his kingdom was, almost uniquely, shaken by four different waves of Reformation upheaval: urban, legal, peasant, and elite. During the urban wave, the kingdom’s Baltic ports were seized by religious revolutionaries in 1525, backed by crowds of sailors and fishwives, in violent Reformation city revolts unparalleled in Europe. In the case of the legal revolt, King Sigismund stunned the pope in 1525 by turning the lands of the Teutonic Order (crusading monks) into a vassal territory for himself, ruled by a new Lutheran duke of Prussia. Christendom’s very first legally Lutheran state was thus found within the Polish monarchy. The peasant upheaval also took place during 1525, when armies of Luther-quoting rebel peasants rampaged through King Sigismund’s Prussia in a full-scale Reformation uprising by the lower orders. And during the elite wave, Polish towns and nobles eagerly invited Lutheran preachers, tutors, and printers into their midst, where they were protected by the kingdom’s most powerful magnates, such as Łukasz Górka of Poznań. Polish undergraduates were a common sight at Luther’s Wittenberg University. In the 1530s, observers across Europe—from Vienna to London—were convinced that after old Sigismund’s death, Poland’s next king would be a Lutheran, who would take the radical step of announcing Europe’s first Lutheran monarchy. Besides the Holy Roman Empire itself (Germany), no other country was as rocked by Luther’s message in the 1520s as Poland.

Image credit: Miniature of Sigismund I the Old by Lucas Cranach the Younger, c. 1553. Photo by BurgererSF. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: Miniature of Sigismund I the Old by Lucas Cranach the Younger, c. 1553. Photo by BurgererSF. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.This powerful episode from the very genesis of the European Reformation has much to tell us, precisely because it was located at the historic cutting edge, right on the threshold of a brave new world. It is the reactions of King Sigismund—with his reputation for piety and good sense—his counsellors and bishops, which are just as significant as the events themselves. The majority of suspected Lutherans were ignored, or allowed to walk unpunished from court-rooms, and they certainly did not inspire the same existential horror that medieval heretics had. Modern Polish historians and politicians have long prided themselves on the country’s (claimed) traditions of religious toleration. But King Sigismund was not a liberal avant-la-lettre; he simply perceived the Reformation rather differently to us.

Lutheran rebels who took up arms, such as Jakub Knade, were ruthlessly hunted down by the Crown. But the peaceful majority of Luther-sympathisers were regarded as bookish dissidents, anomalies, misguided but genuine fellow Christians, members of a late medieval church which already accommodated an impressive variety of pieties and ideas: not as enemies of Crown or society. Paradoxically, the ruling elites in Poland saw most Lutherans as fellow Catholics—whereas Lutherans were perfectly clear in their own minds and writings that they had rejected the Roman church entirely as a hellish darkness. Poland may not have ended up Lutheran by 1600, but it is a historical laboratory in which we can see how late medieval Christians imagined, and brought, both Lutheranism and reformed Catholicism into existence.

This year, as the snows melt in Central Europe, tourists will walk under the medieval cranes of Danzig’s waterside, or step over the plaque in Krakow’s market square marking the 1525 creation of Ducal Prussia (upstaged by men in dragon costumes, buskers, and flower-sellers), or take tea in Poznań’s Egyptology museum café, where Łukasz Górka once dwelt with his Lutheran household. They may be coming to contemplate other histories—ancient, Renaissance, Jewish—but all around them are spaces, sites and ghosts integral to the story of how Europe slipped into two polarised, warring churches, leaving behind a late medieval culture which had stretched from Lisbon to Lublin. The story of Martin Luther and King Sigismund, then, is a story of lost identities, new identities, and alternative narratives in European history—a timely lesson in how revolution, and cultural fragmentation, begins.

Featured image credit: Martin Luther statue in Wittenberg by schorschel1982. CC0 via Pixabay .

The post Martin Luther’s Polish revolution appeared first on OUPblog.

European Public Law: facing the challenge of decline

In recent years, Europe has lost much of its promise. The financial crisis, the debt crisis, the refugee crisis, the apparent systemic deficiencies of national and supranational governance structures, as well as a fading confidence in democratic government, have led to a certain impression of “messiness.” If we take a look at Europe’s current legal and political landscapes, we find ourselves, in our imagination, in the Rhine-Ruhr-Area: in Europe’s biggest, confusing, and most intricate megacity in the heartland of Schuman’s and Adenauer’s Europe, which mirrors rapidly changing economic and cultural realities. There, even locals go astray when adventuring beyond well-trodden paths, often apologizing for its unstructured appearance with a sense that its best days are over. Regarding the situation of public authority in Europe, academics express the same downbeat perception of entanglement and decline that we associate with the Rhine-Ruhr-Area in a more sophisticated, but no less paralyzing fashion: by quoting the philosopher Samuel Pufendorf. The famous dictum which Pufendorf used to characterise the messy structures of the Holy Roman Empire has become a commonplace in legal and political scholarship as we try to grasp the particular features and dynamics of Europe as a legal and political space: irregulare aliquod corpus et monstro simile, which means a monster-like body politic.

To address such structures, a broad approach is urgently needed—an understanding of European public law that takes a fresh look on realities and paves the way for a better understanding, and ultimately includes domestic public law. We need to reach beyond the public law of the European Union because public authority in Europe remains overwhelmingly exercised by state institutions whose authority flows from their various constitutions. The various crises of these last years have made glaringly clear how much depends on the proper functioning of Member States’ public laws, laws that are hardly known outside the respective countries. Yet, these domestic laws form part of today’s ius publicum europaeum, of European public law as a transnational constitutional space, a legal and political sphere where institutional structures and legal dynamics are horizontally, as well as vertically, intertwined. Member States’ public laws are core elements of the European legal space, where institutions are not integrated within a strictly hierarchical system. They are united by the transnational elements of European public law: most importantly supranational European Union law, but also the European Convention on Human Rights and other international instruments such as the Treaty on Stability, Coordination and Governance, or conditionalities that require domestic reform. These different domestic and transnational laws continuously interact both vertically and horizontally, and have become mutually dependent, forming one legal space.

The broad “European Public Law” approach has analytical, as well as normative and constructive ambitions.

The broad “European Public Law” approach has analytical, as well as normative and constructive ambitions. While we identify and describe the often complex, sometimes irritating, pluralities of current European legal and constitutional landscapes, we articulate, at the same time, the aim for its conceptualization and for corresponding doctrinal reconstructions—for a restructuring and revirement that draws from existing constitutional and political traditions. “European Public Law” provides an analytical tool that aims at the full picture by encompassing national, supranational, and international elements. At the same time, our approach does not limit itself to “neutral” description. “European Public Law” takes a position and plays a performative role.

First, the “European Public Law” approach pursues European unity as expressed by the preamble of the Treaty on European Union (TEU). European unity presents a fundamental value. Though it remains open in many respects, it is neither devoid of contours nor of many settled components. Some can be grasped easily through comparison with other attempts at regional integration.

Second, “European Public Law” goes beyond Brussels, Strasbourg, and Luxembourg. As a comprehensive concept of European public law, transcending a narrow idea of European public law that focusses exclusively on EU law, “European Public Law” takes a closer look to the various domestic legal orders as the loci of most legal operations, deep normativity, and rich scholarship. Their astounding diversity merits our deep engagement—a diversity of stronger and weaker states, of administrative structures that flow from English and French to Ottoman and postcolonial traditions, of unitary and federal systems, of different forms of judicial review, and of academic learning. If properly construed as mirroring, structuring, and guiding legal communication in the European legal space, European public law will substantiate and structure the complex ties of European unity.

Third, “European Public Law” advocates scholarship that lives up to the complexity of these ties. This implies joining what our conventional thinking—that is, thinking in terms of “legal orders”—sets neatly apart: EU law, the European Convention on Human Rights, various domestic laws enacting or responding to such transnational law, comparative law, and some international instruments. A comprehensive approach does not repudiate thinking in terms of legal orders, but it embeds the conventional mind-set in order to respond to increased legal complexity.

It goes without saying that public law scholarship alone cannot mend the crises that led to citizens’ alienation from Europe. But it can help. A large part of public discourse is shaped and even invented by scholars. Scholarship reflects and creates legal and political imaginaries. Through their reconstructions, scholars create order and provide meaning—not only for experts. For sure, such constructions face significant challenges in a space that comprises a core of 28 domestic legal orders spelt out in 24 different languages. There hardly seems a path to European public law that does equal justice to all domestic systems. And yet, the impossibility of perfect justice does not justify forsaking any attempt at improvement. After all, Europe was not built on anxiety and depression, but on bold realist idealism and tireless aspiration. Drawing inspiration from Jean Monnet, one should not to be discouraged but rather emboldened by the messiness of the present and the challenges ahead.

Featured image credit: Mülheim an der Ruhr by giggel. CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

The post European Public Law: facing the challenge of decline appeared first on OUPblog.

June 24, 2018

Philosopher of the month: Mullā Sadrā [quiz]

This June, the OUP Philosophy team honours Mullā Sadrā (1571 – 1640) as their Philosopher of the Month. Mullā Sadrā was born in Shiraz, southern Iran, but moved around when he was studying and for the many pilgrimages he embarked on in in his lifetime. He later returned to Shiraz when he began teaching and taking on followers of his philosophy. He is best known for his work on Transcendent Wisdom, the philosophical school he founded, along with his work on metaphysics and proving the existence of God. Sadrā also worked in a range of other fields including epistemology, psychology, theology, and mysticism.

How much do you know about the life and work of Mullā Sadrā? Test your knowledge with our quiz below.

Quiz image credit: Inside of the House of Mulla Sadra in Kahak. CC-BY-SA-4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Featured image credit: Building in Qom, Iran by Mostafa Meraji. CC-BY-SA-4.0 via Wikimedia Commons .

The post Philosopher of the month: Mullā Sadrā [quiz] appeared first on OUPblog.

Gulls on film: roadkill scavenging by wildlife in urban areas

The impact of roads on wildlife (both directly through wildlife-vehicle collisions, and indirectly due to factors such as habitat fragmentation) has likely increased over time due to expansion of the road network and increased use and number of vehicles. In the UK, for example, there were only 4.2 million vehicles on the roads in 1951, compared to 37.3 million by the end of 2016. With more than a million wild vertebrates estimated to be killed by traffic daily, roadkill is now a higher cause of mortality for vertebrates in the US than hunting. We can learn a lot about animal ecology and behaviour by monitoring these flattened fauna, including their distributions, especially in the case of difficult-to-survey animals such as polecats (Mustela purotius); for example, 51% of records on a recent UK-wide survey were of roadkill animals. Carcasses of roadkill animals are also frequently collected on behalf of schemes such as Cardiff University Otter Project and the Predatory Bird Monitoring Scheme to monitor wildlife disease, and the presence of pollutants such as pesticides and heavy metals.

Monitoring roadkill can allow us to discover more about the impacts of roads on wildlife; roadkill counts can provide us with estimates of the number of animals killed on our roads each year and can allow us to measure the effectiveness of mitigation measures (such as wildlife crossings) that are installed to try and reduce this impact. The observed numbers of roadkill, however, may be an under-estimate because of the actions of scavenging animals that are eating or removing carcasses before they are counted. In our study, we aimed to quantify just what that shortfall was and find out which urban species are doing the scavenging. We wanted to know how quickly “roadkill” was removed, which species were removing it, and whether this differed between city parks and highly urban areas.

We used motion-sensitive camera-traps baited with chicken heads as proxy “roadkill” to attract scavengers. This provided us with a standard bait size (the bait weighed approximately 50g, equivalent to a large vole). Twelve locations around the city of Cardiff, Wales were baited with roadkill and filmed during this study, half of which were “residential” (within 50m of housing), and the other half were parkland. We filmed each site a total of ten times, combining to make a total of 120 filming sessions. The cameras were capable of filming using infra-red light, which allowed us to film both nocturnal and daytime scavengers. Using these remote cameras prevented any unnecessary disturbance to the animals and enabled us to gain exact times at which our scavengers snatched the roadkill.

We wanted to know how quickly “roadkill” was removed, which species were removing it, and whether this differed between city parks and highly urban areas.

Seven different species removed the roadkill; two species of gull; herring gull (Larus argentatus) and lesser black-backed gull (Larus fuscus), carrion crow (Corvus corone), Eurasian magpie (Pica pica), red fox (Vulpes vulpes), domestic dog (Canis familiaris), and domestic cat (Felis catus). Mice (Apodemus sylvaticus), and a brown rat (Rattus norvegicus) were also observed snacking on the roadkill but did not remove it completely.

Of the 120 corpses, 90 (76%) were removed within 12 hours. Birds were the more frequent scavengers, removing 51 of the carcasses, compared to 28 by wild and domestic mammals (in some instances, the scavenger was not caught on camera). Scavengers removed our roadkill remarkably quickly; 62% of carcasses were taken within two hours! The early bird gets the roadkill, it seems; scavenger activity peaked between 7-11 a.m. (sunrise was around 7:40 a.m. during the study), with over half (53%) of roadkill removed between these four hours. Most roadkill could therefore be removed before it could be observed during daytime roadkill surveys. Indeed, we calculated that roadkill could be under-estimated by a factor of up to six times due to the behaviour of scavengers.

The quick removal of roadkill, as well as the variety of species observed feeding on it, shows that many species are behaviourally adapted to scavenge on roadkill in urban environments. Roadkill is clearly an important source of food for scavenging animals, and by removing carcasses from our towns and cities (alongside other human-related food sources), scavengers in our towns and cities are providing valuable ecosystem services. Is it perhaps time to re-think the “pest” reputation of urban wildlife such as gulls, corvids, and foxes?

Featured image credit: Street. Public domain via Pixnio.

The post Gulls on film: roadkill scavenging by wildlife in urban areas appeared first on OUPblog.

Gun control is more complex than you think

In the public debate over gun control, many people talk as if our only options are to support or oppose it. Although some endorse more expansive views, many still talk as if our choices are quite limited: whether to support or oppose a small number of specific gun control proposals–for example, banning assault weapons. Both suppositions oversimplify and distort our choices. In reality, we face three intermingled policy questions: Whom should we permit to own firearms? Which guns should they be permitted to own? How should we regulate the guns they may own?

Virtually no one thinks we should permit everyone—two-year-olds, former violent felons, or the demonstrably mentally ill—to own guns, nor that we should permit private citizens to own all types of firearms—for instance, bazookas and grenade launchers. Finally, most everyone realizes we need additional regulations: when, where, and how those who legitimately own firearms can purchase or obtain them (a licensed dealer or out of the trunk of the local crime boss’s car?); how, when, and to whom they can sell or transfer them (can I sell them to known felons or give them to my six-year-old nephew?); whether (and how) people can carry them in public (not on airlines); and finally, how people store guns and ammunition (must they be in gun safes or can they be tossed willy-nilly on the front porch?).

Once we acknowledge the complexity of these issues, we see that any resolution will be difficult to identify and execute. We must decide whether people, and whom specifically, have a right to bear arms, what kind of right they have, and how unfettered the right is. We must evaluate divergent empirical evidence about (a) the role of guns in causing harm, and (b) the extent to which private ownership of guns can protect innocent civilians from attacks by criminals, either in their homes or in public.

Since we have less than indubitable evidence to resolve these issues, we must decide how to proceed despite some uncertainty. Although this might seem to be a shocking admission, it is actually old hat for policy regulations. When we initiated policies to lessen the number of automobile deaths and the severity of injuries, we had only vague notions about what policies and practices might work—installing seat belts, lowering speed limits, requiring states to made highway lanes wider, or encouraging car manufacturers to install systems that warn drivers when they drift into an adjoining lane. We tried various policies and discovered that some worked.

Resolving these issues is arduous; it requires intellectual honesty and self-criticism. Unfortunately, disputants often overstate or misstate their respective cases. Let me offer two examples.

Some advocates for particular gun control proposals transform what is a legitimate aspiration into a suggestion that they will achieve more than they possibly can. For instance, some people talk as if banning assault weapons would eliminate mass shootings. This suggestion is not only false, it is strategically imprudent. After the next mass shooting, people might infer that the ban is useless. This response could be avoided if advocates were more circumspect. No achievable policy can eliminate such shootings, at least not in the US where so many firearms are in circulation. What we can strive for are policies that diminish their frequency and lethality. Moreover, since spree shootings are a miniscule portion of the total number of gun homicides, advocates of assault weapon bans should acknowledge that bans would have a minimal effect on overall gun violence. Additional policies would be required.

Pro-gun advocates also oversimplify the debate. Many standardly reject gun control proposals as depriving law-abiding gun owners of the ability to defend themselves. However, to say that someone is “law-abiding” is simply to acknowledge that he or she has not yet been convicted of a crime. However, some people who have not previously been convicted of a crime end up committing. It is especially true for crimes of passions, such as when someone is jealous, drunk, clumsy, or mistaken. This phenomenon is relevant to the current US debate. Many spree killers—for instance, the shooters at Virginia Tech, Aurora, Orlando, Las Vegas, and Parkland High—obtained all or most of their guns legally. The shooters were, up until the time of their respective attacks, law-abiding citizens. Yet presumably most people would like to identify ways to keep guns—at least some guns—out of the hands of those who could become spree killers.

Regardless of what side you fall on, the gun control issue will not be solved by oversimplifying matters. Thoughtful, nuanced thinking is essential to achieve a resolution.

Featured image credit: Unloaded gun by St. Louis Circuit Attorney’s Office. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Gun control is more complex than you think appeared first on OUPblog.

June 23, 2018

Who cares about scholarly communication?

Is there really anything that everyone needs to know about scholarly communication? At first blush, the answer might seem to be no. Scholars typically communicate mostly with each other: they create articles, books, white papers, and other scholarly products, not usually expecting that those writings will reach millions of people and directly affect the public’s collective mind and discourse, but more often with the hope that their colleagues will read what they’ve written and that their ideas and discoveries will shape the discourse within their fields, and will eventually make the world a better place in that way.

The more I thought about it, though, the more I realized that scholarly communication is nowhere near as self-contained as one might think, and that it’s important for the general public to have a better understanding of how it works.

Why? Two reasons come to mind.

First, anyone who goes to university—and as of 2018, that’s roughly two out of three Americans—interacts with the scholarly communication ecosystem both regularly and directly during his or her higher-education experience. Students are assigned to read articles from peer-reviewed journals, consult scholarly monographs published by university presses, conduct library research, do literature reviews, learn how to evaluate journal quality, think about the scientific method, and so forth. If they move on to graduate school their interaction with scholarly communication becomes deeper and more comprehensive, and they very often become published scholarly authors for the first time. An understanding of how scholarly communication works can only help those who are going to spend formative years of their young adulthood (and possibly the rest of their lives) both contributing to and drawing from the well of scholarly and scientific literature that is that system’s lifeblood. Being an advanced student means being a scholarly communicator, and to participate effectively in scholarly communication you need to know more than just the difference between a peer-reviewed and a non-peer-reviewed journal: you need to have at least a general idea of how journals are evaluated, how different kinds of book publishers work, how copyright works (and doesn’t work) in the academic context, and so forth.

Everyone… is a consumer of what the scholarly-communication ecosystem produces.

Second, everyone else—regardless of whether they ever attend university—is a consumer of what the scholarly-communication ecosystem produces. A particular individual may never read an article in a peer-reviewed epidemiology journal, but at some point, she is certain to be encouraged to heed the judgment of her doctor in undergoing, say, vaccination or a mammogram based on the findings that her doctor has read in such journals. Another individual will read an article in a popular magazine that touts a researcher’s claim for the health benefits of pomegranate juice and will do a better job of evaluating that claim if he has some grounding in how scientific findings are evaluated and published. Yet another one will be told by her friend that “studies have shown” that Christopher Marlowe actually wrote Shakespeare’s plays, and may want to investigate this claim for herself—this is the most common, everyday context in which a baseline understanding of scholarly communication is likely to be helpful. People with little to no understanding of how scholarly communication really works open themselves up to manipulation on the part of anyone who begins a statement with “studies show” or “the science says.” Those can be intimidating phrases—but if you have a basic understanding of how science gets published and how to discriminate between good and bad studies, you are empowered to challenge and evaluate such statements.

In short, no one is completely untouched or unaffected by scholarly communication. The practices and products of scholars and scientists affect us more or less constantly in our daily lives, though often in ways that aren’t immediately recognizable: they affect the ways in which newscasters talk about the latest “miracle food” discovery, the ways politicians promote their economic plans to voters, the advertising language we see in magazines and online, and the services offered to us in doctors’ offices. Making those impacts, however quiet and subtle they may be, more easy to detect and thus to think critically about is important. And who knows—some readers might even find that a topic they would otherwise have dismissed as hopelessly obscure and boring (copyright law, say, or the machinations of predatory publishers) is surprisingly interesting. Who knows, maybe they’ll decide to become scholarly communicators themselves. An author can hope.

Featured image credit: “Book, Library…” by Stock Snap. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay .

The post Who cares about scholarly communication? appeared first on OUPblog.

Nine “striking” facts about the history of the typewriter

The first machine known as the typewriter was patented on 23rd June 1868, by printer and journalist Christopher Latham Sholes of Wisconsin. Though it was not the first personal printing machine attempted—a patent was granted to Englishman Henry Mill in 1714, yet no machine appears to have been built—Sholes’ invention was the first to be practical enough for mass production and use by the general public. With the help of machinist Samuel W. Soulé and fellow inventor Carlos Glidden, Sholes had spent the summer of 1867 developing his machine, and by September of that year was able to type his name in all capital letters.

That was just the beginning, as the typewriter’s societal and cultural impacts are still felt today. We’ve gathered these fascinating facts about this remarkable device, from its effect on women in the workforce to its direct influence on computers over a century later.

1. Christopher Latham Sholes (1819-1890) had produced 50 machines by 1873, but was unable to sell them; that year, he sold the production rights to gun manufacturer Philo Remington (1816-1889). By 1874, the first Remington-made typewriter was sold by E. Remington & Sons. In 1878, the first typewriter to offer upper and lowercase letters, the Remington No. 2, debuted.

2. In the 1890s, Remington competitor John Thomas Underwood (1857-1937) bought the rights to a more practical “front-stroke” machine from inventor Franz Xavier Wagner. The US Navy ordered 250 Underwood typewriters in 1897, solidifying his place in the market, and by 1915, the company employed 7,500 workers and produced 500 typewriters daily.

Image credit: Drawing for a Typewriter, 06/23/1868. This is the printed patent drawing for a typewriter invented by Christopher L. Sholes, Carlos Glidden, and J. W. Soule. From the National Archives. Brian0918, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: Drawing for a Typewriter, 06/23/1868. This is the printed patent drawing for a typewriter invented by Christopher L. Sholes, Carlos Glidden, and J. W. Soule. From the National Archives. Brian0918, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.3. Even though he had been unsuccessful in the marketing of his invention, Sholes was aware that the typewriter would be vital in helping women achieve entrepreneurial freedom, saying it was a means for women to “more easily earn a living.” Typewriting led to a separation of the authorship and the writing up of documents, which provided a new social avenue for women, especially in business and politics.

4. Mark Twain was the first author to submit a book manuscript in typed copy, having bought a typewriter in 1874. The typewriter became a symbol of a certain type of writer, and many are still preserved in the estates or museums of well-known authors such as Ernest Hemingway, Rudyard Kipling, George Bernard Shaw, and Ian Fleming.

5. In 1909, G. C. Mares described a hypothetical situation that would allow “a man sitting at his Zerograph [another early typewriter] in London…to hold written converse with his correspondents in the furthermost parts of the globe, without the intervention of any physical connection”—a process that sounds very similar to email.

6. The original typewriter’s most ubiquitous impact on modern society, seen all around the world on computer keyboards and mobile phones, is its key layout known as QWERTY. Christopher Latham Sholes originally tried an alphabetical layout in his prototypes, but the keys would jam; his solution shifted three of the most commonly used letters (E, T, and A) to the left hand, resulting in a design that slowed typists down and avoided jamming on the earliest machines.

7. In 1932, William Dealey and August Dvorak introduced the Dvorak keyboard, which was designed to make typing faster and less fatiguing; studies showed it increased accuracy and speed by about 70%. However, it never caught on because QWERTY had become too entrenched in society. It had been the sole layout when Remington cornered the market at the beginning, and by the 1930s, manufacturers, typists, and typing schools had too much invested in the status quo to change, even to a more efficient format.

Image credit: Fig. 1: Machines with one character per key. Fig. 2: Machines with two characters per key. Fig. 3: Machines with three characters per key. Larousse mensuel illustré, 1911, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: Fig. 1: Machines with one character per key. Fig. 2: Machines with two characters per key. Fig. 3: Machines with three characters per key. Larousse mensuel illustré, 1911, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.8. Famed polymath and horologist Rupert T. Gould (1890-1948) was fascinated with typewriters his entire life; by the 1940s, he had one of the largest collections in existence—at least 71—and wrote the first independent history of the machine, called The Story of the Typewriter in 1949.

9. It has been argued that the typewritten page was an influence in the move in book designs from justified lines to even-spacing between words and the uneven right-hand margins this causes. Artists in the 1950s also used the typewriter to experiment with the placement of text to create “concrete poetry.” Poet Aram Saroyan wrote:

I write on a typewriter, almost never in hand … and my machine—an obsolete red-top Royal Portable—is the biggest influence on my work. This red hood hold [sic] the mood, keeps my eye happy. The type-face is a standard pica; if it were another style I’d write (subtly) different poems. And when a ribbon gets dull my poems I’m sure change.

Featured image credit: Ernest Hemingway’s typewriter in his studio, Ernest Hemingway House, Key West, Florida, USA. Acroterion, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons .

The post Nine “striking” facts about the history of the typewriter appeared first on OUPblog.

The Kuleshov Fallacy

The face has long been regarded as one of the major weapons in the arsenal of cinema—as a tool of characterization, a source of visual fascination, and not least, as a vehicle of emotional expression. Research on emotion from psychology and other disciplines offers a rich resource illuminating the world of expressive behavior on which filmmakers draw, and shape to their own artistic ends, as I discuss in an earlier blog here.

But there is an influential idea in the history of film—part of the lore of film theory, exerting considerable influence among filmmakers—which holds that facial expression is at most of secondary importance in the way that films generate meaning and emotional impact. That idea is the “Kuleshov effect,” named after Lev Kuleshov, one of the heroic generation of Soviet filmmakers who put Soviet cinema at the forefront of the new medium in the 1920s. This vanguard introduced numerous innovations and inaugurated (alongside filmmakers and critics elsewhere in Europe) the tradition of film theory—that is, reflection on the nature of film seeking to identify the unique characteristics and potentials of the emerging art form.

In the early 1920s, Kuleshov conducted a number of informal experiments with his students and colleagues—among them another star-to-be of the Soviet filmmaking scene, V. I. Pudovkin, who would be important in documenting the experiments and disseminating the key conclusions drawn from them.

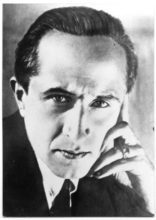

Image of Lev Kuleshov. Public domain via Wikispace

In one of the experiments, Kuleshov and his team edited an identical shot of the famous actor Moujoukine into three different sequences, juxtaposing his face with, respectively, shots of a bowl of soup, a woman in a coffin, and a girl playing with a toy bear. (Descriptions of the experiment offered by Kuleshov and Pudovkin in subsequent years vary in terms of the exact content of the shots – the original footage is lost, though fragments and evidence of the other experiments have survived.) The goal of the experiment was to test—or perhaps more accurately, to demonstrate—the power of editing. Kuleshov found that the emotion viewers attributed to Moujoukine varied according to the context in which the shot was placed: hunger when juxtaposed with the bowl of soup, sadness with the coffin, and happiness with the child. This affirmed the view among the Soviet film innovators that montage – editing – was the key to the power of cinema. In this way, the experiment made a critical contribution to the movement that would come to be dubbed “Soviet montage.”

But does the Kuleshov effect hold water? Recent attempts to re-test the Kuleshov hypothesis more rigorously suggest that it is a reality (though there is plenty of devil in the detail); those results won’t surprise anyone with expertise as a filmmaker or critic. But without careful handling, Kuleshov’s insight turns into a fallacy. The idea of the Kuleshov effect initiated by the original experiment and that continues to replicate – the Kuleshov meme – is deeply misleading to the extent that it suggests that performative factors, like facial expression, play no significant role in shaping our experience of films. But many filmmakers and critics continue to peddle the idea.

In a generally very insightful exploration of Bernard Herrmann’s films scores, for example, the film composer Howard Goodall says of the sequence in Psycho where Marion Crane drives into the night with the money she’s stolen from her boss: “What’s remarkable about [Herrmann’s cue for the scene] is how much impact it has on the pictures. Without it, what we’re looking at is someone driving along in a car, and there’s nothing dramatic, tense, or worrying about that.” Here the contextual factor invoked by Goodall is the score rather than the editing; but the underlying implication is the same—the face is sufficiently inert or open to interpretation that any role it might play in conveying expressive information is overridden by contextual features, like Herrmann’s score in this case.

Janet Leigh as Marion Crane in Psycho (Alfred Hitchcock, 1960). Images provided by Murray Smith.

But a close look at the sequence exposes the fallacy at work here. Janet Leigh’s performance conveys the emotions of Marion in nuanced but palpable fashion. Her anxiety is evident from a variety of telltale facial expressions, including lip-biting and squinting as night falls and headlights from the oncoming traffic dazzle her. And her facial behavior is of a piece with her bodily demeanor—deep sighs and irregular breathing, restless fidgeting with the steering wheel—conforming to the view of Dacher Keltner that facial expressions need to be understood as part of a multimodal expressive system including the voice and the body. So even if we stripped away Herrmann’s score, Marion’s state of mind would remain tangible from these expressive behaviors.

What is still more striking is a brief passage when Marion’s anxiety wanes and a different emotion takes hold of her: a faint but definite smile is visible on her face as she imagines the moment when her boss discovers her theft (represented by dialogue on the soundtrack).

Janet Leigh as Marion Crane in Psycho (Alfred Hitchcock, 1960). Image provided by Murray Smith.

According to the logic of the Kuleshov effect, this fleeting expressive moment ought to be rendered invisible by the context in which it appears (remember, according to Goodall, without the music all we see is “someone driving along in a car”). But in fact, the force of facial and bodily expression here is such that Leigh’s performance acts in counterpoint to the emotional tenor of Herrmann’s angular, edgy cue. This is only possible because facial and bodily expression are powerful, independent sources of expression in films, working alongside other techniques such as editing and music, not mere handmaidens to these other “medium-specific” parameters.

None of this is to say that Kuleshov didn’t discover, or at least demonstrate and popularize, an important aspect of the art of film. But the power of the Kuleshov effect, and its authority as a discovery deriving from an “experiment,” is often overstated. Part of the problem arises from this very characterization of Kuleshov’s explorations as “experiments.” The idea that artists can engage in experimentation is a common one, and plausible enough in a certain sense. But what’s the relationship between an artistic and a scientific experiment? That is a question that deserves independent consideration.

Featured Image Credit: Janet Leigh as Marion Crane in Psycho (Alfred Hitchcock, 1960). Image provided by Murray Smith.

The post The Kuleshov Fallacy appeared first on OUPblog.

June 22, 2018

Orangutans as forest engineers

Orangutans quite literally are “persons of the forest,” at least according to their Malay name (orang means “person” and hutan is “forest”). But this is more than just a name. As well as their distinctively “human” qualities, these large charismatic fruit-eaters are also gardeners, forest engineers responsible for spreading and maintaining a wide array of tree species. In Borneo in particular, their role as ecosystem engineers is not simply aesthetic, they may be critical for mitigating global carbon emissions. But how exactly might orangutans do this? The answer is in their poo.

Orangutans are the largest tree-dwelling frugivores (fruit eaters) in the world. They eat leaves, flowers, some invertebrates, and may even scavenge meat on occasion, but they are primarily fruit eaters, being especially attracted to the energy-rich fruits of the biggest forest trees. While other large animals, such as elephants and rhino, are capable of spreading seeds from fallen fruits, orangutan are capable of spreading the seeds from the hanging fruits of the largest trees, making them critical for forest production and regeneration.

Image credit: Flanged male orangutan. Copyright Dr Esther Tarszisz.

Image credit: Flanged male orangutan. Copyright Dr Esther Tarszisz.In Central Kalimantan, orangutans are vital for the health and well-being of their tropical peatland homes, and not just for their own survival. Indonesia’s tropical peat swamps are massive carbon sinks, trapping up to 20% of the earth’s soil carbon. These swamps already face enormous challenges from clearing, peat drainage for agriculture and timber extraction, and subsequent fires. In 2015 alone, these activities released 0.89 – 1.29 gigatons of carbon dioxide equivalent from Indonesia’s peatlands. Crucially, collapse of these peatland ecosystems would see the release of gigatons of carbon to the atmosphere, comparable with thousands of years of this stored peat carbon being released in just decades; a Gaian “burp” of titanic proportion, and consequence.

To find out just how important orangutans are for these peatland forests, we collected over 200 individual poo samples from wild orangutans in Central Kalimantan. Poo samples were washed and the seeds collected and germinated in a local nursery, alongside those extracted by us from intact fallen fruits. We found 13 species of undamaged types of tree seeds in orangutan poo, ranging in length from 2cm. Most of these germinated more successfully than the seeds we physically extracted from whole fruits. However, in addition to seeds from poo samples, we collected seeds that were spat to the ground by orangutans during feeding. Curiously, these spat out seeds had the highest germination success, especially for the very largest seeds (> 20 mm). The importance of the higher germination success of seeds spat by orangutan has hitherto been overlooked, but could be enormously important for the dispersal of the largest forest trees, as fruits can be carried considerable distance from a parent tree before the remnant seeds are ejected to the ground.

Image credit: Dr Esther Tarszisz planting seeds clean from orangutan poo. Image copyright Borneo Nature Foundation.

Image credit: Dr Esther Tarszisz planting seeds clean from orangutan poo. Image copyright Borneo Nature Foundation.The movement of seeds from their parent tree is key to mapping seed dispersal patterns, but as well as noting seed spitting, we need to know when and where orangutans poo. To that end we followed wild orangutans habituated to humans over several seasons, noting where and when they fed, and more importantly, where they pooped! We combined this data with measures of the passage of artificial seeds (plastic beads) through captive orangutan at Australia’s Perth and Taronga zoos. We did this by training captive orangutans to swallow our seed mimics and then, you guessed it, we collected their poo. Overall, we found that plastic “seeds” took an average 70-90 hours to pass through the orangutan, and up to 120 hours to be completely eliminated. Thus, in terms of mapping the potential dispersal of seeds by orangutans, we showed that fecal deposition, or poo points, from where seeds were initially ingested lagged behind the actual animal movement by 3-5 days. This has several key implications for the forest structure and establishment of new plants. Female orangutans tended to be more centric in movements driven by food sources, but males roamed widely for food and mates. This suggests that seed dispersal implications of males and females may be very different, but critical for the maintenance of centrally located fruits as well as those spread more broadly to support wandering males.

After many hours following and watching wild orangutans it is hard to deny their human-like mannerisms. What is clear is that these “persons of the forest” may be vital for the preservation of Indonesia’s massive global carbon stores. But orangutans continue to be threatened by legal and illegal land clearing, as well as hunting. This needs global attention, and further declines, or worse extinction, of these charismatic forest gardeners may reflect a grim rehearsal of our own demise, unless we pay attention and take action now, before the poop really hits the fan!

Image credit: Mother and young orangutan. Copyright Dr Esther Tarszisz.

Image credit: Mother and young orangutan. Copyright Dr Esther Tarszisz.

Featured image credit: Orangutan by ghatamos, CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Orangutans as forest engineers appeared first on OUPblog.

Global health as a social movement: Q&A with Dr. Joia Mukherjee

What is social entrepreneurship? In essence, it’s about using the tools of entrepreneurship—opportunity, resourcefulness, innovation—to address stubborn social and environmental problems. A defining feature of social entrepreneurship is the concept of systemic change; that is, change that addresses the underlying social, political, and economic forces that conspire to exclude the poor and marginalised from the opportunities that many of us take for granted.

The global AIDS movement is perhaps the most powerful example of systemic change in our lifetimes. Although the discovery of combination therapy for HIV in 1995 turned AIDS from a death sentence into a manageable chronic disease, high drug prices and fragile, underfunded health systems in much of the global south meant that millions were denied access to lifesaving treatment.

A decade later, thanks to a global movement of grassroots AIDS activists and scientific advocates, the world looked different. Billions of dollars in new funding were committed for AIDS treatment. Market reforms reduced drug prices by over 90%. And, most importantly, a global consensus emerged that every person with HIV/AIDS had a right to treatment.

I recently had the opportunity to chat with Dr Joia Mukherjee, a long-time colleague, mentor, and co-conspirator of mine, about the legacy of the global AIDS movement, and what comes next in modern healthcare delivery.

Peter Drobac: Working to transform unjust systems is a defining feature of social entrepreneurship. You highlight the Global AIDS movement as an example of large-scale, systemic change. What lessons from the AIDS movement could help aspiring social entrepreneurs address other complex social problems?

Dr Joia Mukherjee: To me, the most important and unique aspect of this movement and its success is transnational solidarity. Making the problems of human beings universal rather than walled off as only meaningful from the lens of the national state. Many of our friends from wealthy countries stood side by side with those from impoverished countries and said, “we matter” “All of us.” We could, as a human species do that for many other things.

Public health and international development have traditionally been fairly utilitarian—do the most good for the most people with the resources available. How does a focus on equity and human rights challenge that convention?

I think where utilitarian frameworks have failed is in the last part of your statement, “with the resources available.” The problem is, the decision about what resources are available is not based on “reality,” it is based on a set of choices that the global community and individual countries make: the choice of waging war, the choice in pricing pharmaceutical products, the choice of promoting market solutions to social problems.

Therefore, the conversation starts with a “resources available” question that comes out of a very skewed function machine. When the focus is on human rights and health equity, the equation is reversed. We are mandated as human beings to assure basic rights and social protection and then we need to understand how much it will cost and how it will be financed.

When we asked the children […] what their main risk factor for AIDS was, they said, “poverty.”

What has been your most powerful learning experience?

To this day, I can honestly say that my most powerful learning experience was when I first worked as an AIDS educator in Uganda in 1994. I was working with children 11-14 and teaching them about AIDS transmission, prevention, etc. When we asked the children, after many hours of workshops, games, songs, and learning, what their main risk factor for AIDS was, they said, “poverty.” I was stunned. It transformed my life and moved me away from prevention to a comprehensive view of what is really needed to achieve health; economic and social rights like a job, housing, school, food, and health care that has both prevention and treatment. Poverty is such a crushing and unaddressed aspect of all health—from epidemics, to non-communicable diseases, to death in childbirth. This has always guided me.

I can think of few other academic health care leaders who spend as much time as you do in villages and communities with patients and front-line health workers. Why is this important to you?

Medicine, as taught in the US, is so technical. Health is not. By seeing the struggles of patients to feed their families and even get to clinic—through the mud, on a donkey, being carried on a litter—profoundly shapes how I think about delivery. It is why the book has such a strong focus on social medicine. As Chief Medical Officer of PIH, it is similarly important for me to see what challenges our staff face—whether it is a drug stock out or unimaginable lines in the emergency room. It motivates me to do better and do more; and reminds me that there are no simple fixes for social justice.

Image Credit: An advert for AIDS education. CC BY-NC 4.0 via Wellcome Images.

Image Credit: An advert for AIDS education. CC BY-NC 4.0 via Wellcome Images.Universal Health Coverage (UHC) has become the top priority of World Health Organisation and many others. Is it really possible to achieve UHC? What would it take?

Strategy and money are both critical to the progressive achievement of UHC. Countries must commit more money for their people (and many have) but at the end of the day, for impoverished countries, even if political commitment is high, there is not enough money. We must globalize the notion of the financing for this basic human right. But developing a delivery strategy is also critical. Aid often fragments systems and results in enormous insufficiencies. Part of Rwanda’s success is vision and strategy, and coordination of donors and partners to adhere to a plan. Having just returned from Cuba I can also say that it is the best planned and most coordinated system I have ever seen—and the results speak to that in both countries.

What would you say is the distinction, if any, between Global Health and Global Health Delivery?

The focus on delivery is because I believe what defines the current state of global health in the world has been the increasing ability to deliver care; not just measure or describe, but to address vast inequalities in access to life saving medicines and services. Understanding why that gap is there and what can be done about it is a critical piece of the work.

Recently, you have stressed the importance of activism in creating social change. What causes are you focused on right now?

This is an interesting moment for women in the US and around the world. The #metoo movement and the attention on women’s issues, but also the backlash from nationalism and conservatism. It is difficult but also presents an opportunity to build solidarity between women rich and poor, black and white. Right now, we are focused at Partners In Health at trying to build that type of solidarity around childbirth and maternity issues. We know there are massive race and class disparities in birth outcomes for both mother and baby across the world. Can we get women who have the privilege of excellent health care to demand that high quality care for women is not privilege afforded to a few but a basic human right?

Also, AIDS isn’t over and in fact the gains are under threat. We have to assure more funding to end the epidemic. I will always be an AIDS activist.

Featured image credit: “Medicare for All Rally” by Molly Adams. CC BY 2.0 via Flikr .

The post Global health as a social movement: Q&A with Dr. Joia Mukherjee appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers