Oxford University Press's Blog, page 247

June 18, 2018

The 2018 classics book club at Bryant Park Reading Room

Oxford University Press has once again teamed up with the Bryant Park Reading Room on their summer literary series.

The Bryant Park Reading Room was first established in 1935 by the New York Public Library as a refuge for the thousands of unemployed New Yorkers during the Great Depression. Today, thanks to the generous support of HSBC Bank USA, and the continued efforts of the Bryant Park Corporation, the Reading Room is thriving once again. As part of the Bryant Park program, Oxford University Press has created a special book club where we pair acclaimed contemporary authors with a classic title from the Oxford World’s Classics series.

Check out the line-up below. Prior to each event, stop by Bryant Park to pick up a free copy of the book club choice while supplies lasts. The Reading Room is located in Bryant Park, right behind the NYPL Main Branch, on 42nd street between 5th and 6th Ave.

1. Tuesday, June 19, 2018 — Sonia Taitz, author of Great with Child, discussing Kate Chopin’s The Awakening, 12:30 p.m. – 1:45 p.m

Sonia Taitz is a playwright, essayist, and author of three novels and two works of non-fiction. An award-winning writer, her work has been praised by The New York Times Book Review, The Chicago Tribune, People, Vanity Fair, and many other publications.

2. Tuesday, July 10, 2018 — Simon Winchester, author of The Perfectionists, discussing Rudyard Kipling’s Stories and Poems, 12:30 p.m. – 1:45 p.m

Simon Winchester is the acclaimed author of many books, including The Professor and the Madman, The Men Who United the States, The Map That Changed the World, The Man Who Loved China, A Crack in the Edge of the World, and Krakatoa, all of which were New York Times bestsellers and appeared on numerous best and notable lists. In 2006, Winchester was made an officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE) by Her Majesty the Queen. He resides in western Massachusetts.

3. Tuesday, July 24, 2018 — Rebecca Coffey, author of Hysterical: Anna Freud’s Story, discussing Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s The Yellow Wallpaper, 12:30 p.m. – 1:45 p.m.

Rebecca Coffey is an award-winning journalist, documentary filmmaker, and radio commentator. Coffey contributes regularly to Scientific American and Discover magazines. She blogs about sexuality, relationships, crime and punishment, social media, and psychology for Psychology Today, and is a broadcasting contributor to Vermont Public Radio’s drive-time commentary series. Also a humorist, she is the author of Nietzsche’s Angel Food Cake: And Other “Recipes” for the Intellectually Famished (Beck & Branch, 2013) and Science and Lust (Beck & Branch, 2018).

4. Tuesday, August 7, 2018 — Sally Koslow, author of Another Side of Paradise, discussing F. Scott Fitzgerald’s This Side of Paradise, 12:30 p.m. – 1:45 p.m.

Sally Koslow is the author of the novels Another Side of Paradise; the international bestseller The Late, Lamented Molly Marx; The Widow Waltz; With Friends Like These; and Little Pink Slips. She is also the author of one work of nonfiction, Slouching Toward Adulthood: How to Let Go So Your Kids Can Grow Up. Her books have been published in a dozen countries.

Sally is the former editor-in-chief of McCall’s Magazine. She has taught at the Writing Institute at Sarah Lawrence College and is on the faculty of the New York Writer’s Workshop. She has contributed essays and articles to The New York Times, O, Real Simple, and many other newspapers and magazines. She has lectured at Yale, Columbia, New York University, Wesleyan University, and University of Chicago, as well as many community and synagogue groups.

5. Tuesday, August 21, 2018 — Karl Jacoby and Marie Myung-Ok Lee, discussing Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle, 12:30 p.m. – 1:45 p.m.

Karl Jacoby is a professor of history at Columbia University. The author of two previous books, he has won the Albert J. Beveridge Award and a Guggenheim Fellowship, among many other honors. He lives in New York.

Marie Myung-Ok Lee, author of three young adult novels, including Finding My Voice and Saying Goodbye, has received many honors for her writing, among them an O. Henry honorable mention, and both Best Book for Young Adults and Best Book for Reluctant Readers citations from the American Library Association. She is currently a visiting scholar at her alma mater, Brown University, in Providence, Rhode Island.

Featured image credit: Bryant Park, Saturday by Teri Tynes. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr .

The post The 2018 classics book club at Bryant Park Reading Room appeared first on OUPblog.

June 17, 2018

Why are there so many different scripts in East Asia?

You don’t have to learn a new script when you learn Norwegian, Czech, or Portuguese, let alone French, so why does every East Asian language require you to learn a new script as well? In Europe the Roman script of Latin became standard, and it was never seriously challenged by runes or by the Greek, Cyrillic, or Glagolitic (an early Slavic script) alphabets. You still have to learn the Greek alphabet for Greek, or the Cyrillic alphabet for Russian, Bulgarian, and Serbian, but they are the only exceptions. On the other hand, in East Asia today, the logographic script based on the Chinese characters is used in China, while Korean uses the indigenous han’gŭl alphabet, Japanese uses a mixture of Chinese characters and two different syllabaries, Vietnamese uses the roman alphabet, and Mongolian uses the Cyrillic alphabet.

There were even more scripts in earlier times. The Vietnamese used their own indigenous characters known as nôm, the Mongolians used their own vertical script, which was also used by the Manchus in north-east China, the Tanguts in western China invented their own characters, and so did the Khitans in the north-east. So, the first puzzle is the profusion of scripts in East Asia: why are there so many? The second is why none of these scripts actually replaced Chinese characters, at least until modern times. These days, the han’gŭl alphabet is used exclusively, without any Chinese characters, in North Korea, and South Korea is rapidly moving in the same direction; and in Vietnam both Chinese characters and nôm characters have been replaced by an adapted form of the roman script. But before the 20th century every society in East Asia with an indigenous script also used Chinese characters. Sometimes, as in Japanese, Korean, and Vietnamese, the writing system used both Chinese characters and the indigenous script in the same sentence; in other cases, such as Manchu and Tangut, they were kept apart but both were in use. What is the explanation for this state of affairs?

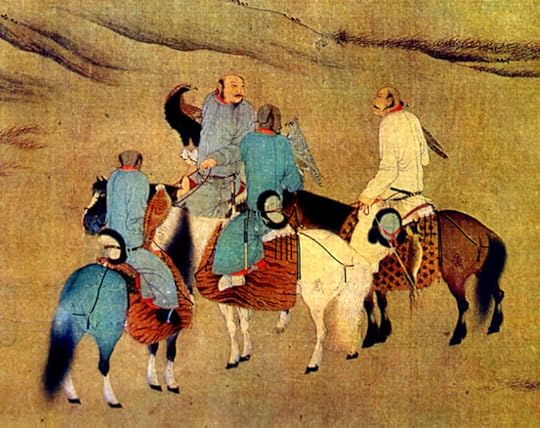

Khitans using eagles to hunt (berkutchi) by Hu Gui. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Khitans using eagles to hunt (berkutchi) by Hu Gui. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.We can start with the assumption that the Chinese characters were the first form of writing known in East Asia. In all societies on the periphery of China therefore, writing was first encountered in the form of Chinese characters and the literary Chinese that they were used to inscribe. Consequently, the earliest texts produced in Vietnam, Japan, and Korea were written using Chinese characters. Local place-names and personal names were written using Chinese characters phonographically, just for their sound alone, and this principle was then taken further, using Chinese characters to inscribe the local vernacular languages. So why was it necessary to invent vernacular scripts?

Although the circumstances in which the various East Asian scripts were invented or developed are different in each case, the scripts are united by one fact. This is that they all owe something to Chinese characters, or at least to their ‘ideal square’ shape. This is obvious in the case of the characters invented in the Tangut empire or in Vietnam, while in Japan the two kana syllabaries represent either abbreviations or cursive forms of Chinese characters. The best explanation for the profusion is that provided by Elena Berlanda, who has attributed script plurality to ‘dissociation’, the desire to be different. For the Tanguts, who were at odds with China, the invention of their own script was a political act, an assertion of independence from the dominant power in the region. Elsewhere, vernacular scripts empowered the spoken vernaculars by enabling them, too, to partake of the prestige of writing that hitherto only Chinese had enjoyed. So in fact the plurality of scripts in East Asia reflects what Kubilai Khan is reported to have said in the 13th century when urging the creation of a script for Mongolian: ‘Every state has its own writing.’

This is certainly true of East Asia now, but before the 20th century every state had its own writing for the vernacular, while at the same time Chinese writing retained its prestige, and for most intellectual writing—on medicine, philosophy, and Buddhism—literary Chinese continued to be used. It had the advantage of being a universal literary language, but when the vernaculars came to the fore in the 20th century, East Asia lost its common language. That was the price to be paid for empowering the vernaculars.

Featured image credit: Page from a 11th-13th century chrysographic manuscript edition of the “Golden Light Sutra” (Suvarnaprabhasottamaraja Sutra) written in Tangut by BabelStone. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons .

The post Why are there so many different scripts in East Asia? appeared first on OUPblog.

June 16, 2018

Why consumers forget unethical business practices

Imagine a consumer, Kate, who enjoys shopping for fashionable clothing, but who also cares about whether her clothing is produced ethically. She reads an article online indicating that fashion giant Zara sells clothing made by allegedly unpaid workers, but a few days later ends up buying a new shirt from Zara. She either forgets that Zara may be mistreating workers, or she mistakenly recalls that they are one of the brands that have agreed to a strict code of ethical labor practices, including paying a living wage to all workers. How could Kate do this if she cares about issues like workers’ rights?

Our research shows that even though most consumers, like Kate, want to abide by their ethics when they go shopping, follow-through is difficult, especially when memory is involved.

In a series of studies published in the Journal of Consumer Research, we uncovered a systemic bias that exists when it comes to trying to remember whether products are ethical. Consumers are much worse at remembering when a product is unethical (e.g., produced by workers who are mistreated) compared to when a product is ethical (e.g., produced using ethical labor standards).

Past consumer psychology research has shown that consumers find thinking about unethical products to be unpleasant. When we’re shopping for clothes, we don’t necessarily want to think about the harsh reality that some of those trendy items might have been made in factories using child labor or using chemicals that damage air quality, and for these reasons consumers often avoid such information altogether.

But what happens if consumers have to face this information? We predicted that they would end up forgetting when a company behaves unethically.

Our research shows that even though most consumers, like Kate, want to abide by their ethics when they go shopping, follow-through is difficult, especially when memory is involved.

Across our studies, we found that study participants consistently had worse memory for unethical information about a product than for ethical information. For example, even after being given several opportunities to memorize information about different brands of desks, participants in our first study were less likely to remember when a desk was made with wood sourced from endangered rainforests compared to when a desk was made with wood sourced from sustainable tree farms. In other studies, participants were less likely to remember when a pair of jeans was made with child labor versus adult labor. Participants’ poor memory for the unethical product information took one of two forms—they either failed to recall any information about this aspect of the product at all or incorrectly remembered the product to be ethical instead.

Is it that people just don’t want to remember “bad” information? We also looked at participants’ memory for other product information not related to ethicality (e.g., price, quality) and did not find the same memory errors, suggesting there is something unique about memory for ethical product information.

We believe this bias only occurs for ethical product attributes because of consumers’ conflicting desires. They generally believe they should remember ethical information in order to do the right thing, but they also have a desire to feel good by preventing emotionally-difficult experiences (which most ethical issues present).

Therefore, these two competing forces, which can be thought about as two separate “selves” of a consumer—the “should self” and the “want self”—conflict with each other when a consumer thinks about negative ethical product information. This conflict is not a pleasant feeling for consumers, so they look to resolve it. And the most likely way to do that? Letting the “want” self win the battle by forgetting the negative ethical information.

So what do consumers think about their poor memory for information about products made in an unethical fashion? A final study using adult participants from an online sample demonstrated that consumers judge the act of forgetting negative ethical information as more morally acceptable than remembering the information but choosing to ignore it.

So, what can companies do to increase the probability consumers will remember that they are ethical? One possibility is to continually remind consumers, even at point of purchase, of their ethical attributes; companies such as Everlane make their ethicality part of their marketing.

What can consumers do to fight this problem of “willfully ignorant memory?” As a start, rely less on memory when shopping. Double back around and revisit that labor practices report before heading out for your next shopping trip at the mall. Relying less on memory takes away the possibility of forgetting that a brand is unethical and purchasing something by accident that does not reflect your values.

Featured image credit: Clothing rack by Lauren Roberts. CC0 via Unsplash.

The post Why consumers forget unethical business practices appeared first on OUPblog.

Revitalizing the Epistemology of Religion

Philosophers studying epistemology debate the exact nature of knowledge, typically by examining the “evidence” behind one’s beliefs: logical processes, sensory perception, and so on. They also wonder about how much we can know. Knowledge about the empirical world is perhaps one thing; yet what about our beliefs in the areas of history, or mathematics, or morality, or politics? Or religion?

Religious belief is subject to constant scrutiny in both philosophy and some popular culture. Should people believe that there is a God or deity of some kind–what kind of evidence or grounds might there be either for or against its, or their, existence? Matters of religion can seem to mimic morality or politics in at least these ways: it can be rather unclear what counts as the right sort of evidence for believing one way or another on some question. And the social nature of our coming to believe (or disbelieve) anything about these domains means that we are largely dependent on testimony from others, and on how we handle disagreements with those whom we respect.

Social epistemology, to its credit, has made enormous advances recently: no longer do philosophers simply consider, as Descartes and other moderns famously did, what I myself alone with my thoughts and my evidence ought to believe.

Social epistemology, to its credit, has made enormous advances recently: no longer do philosophers simply consider, as Descartes and other moderns famously did, what I myself alone with my thoughts and my evidence ought to believe. Epistemologists now reckon with the messy details of how we share our beliefs and knowledge through testimony; how to think about one’s obligations, if any, to modify one’s beliefs when facing disagreement, or how to think about which experts to trust; and how to think about how social factors like gender, race, and class can influence or inhibit the spread of knowledge. In addition, epistemology takes up questions about the nature of “knowledge-how,” and the relation between knowledge and action.

These interests have taken shape alongside important developments in philosophy of language and formal epistemology. Our patterns of ascribing (and denying) knowledge to others is informative for how we deploy the concept of knowledge in everyday life, and for how seriously we take certain skeptical ideas. The formal tools of probability theory have offered new ways of conceptualizing the epistemological terrain, by helping us think more precisely about what evidence is and does, and how it confirms or supports hypotheses. These insights in turn shed light on the epistemological categories of defeat, higher-order evidence, and how an ideally rational agent would respond to new information.

But work in the epistemology of religion has been slow to imbibe many of these new insights and examine where they may lead. Religion is the place where such rethinking can potentially have its deepest impact. One of our aims is to explore these developments and to invite newer questions. For example, how might it be possible to gain knowledge in religious matters given the facts of religious diversity (both within and between religions)? How should we think about the nature of expertise in the domain of religion, especially given rampant disagreement both within religions and between religions? What does formal epistemology contribute to arguments for theism from a universe apparently fine-tuned for life, or for when one might plausibly believe a report of a miracle? How do we gain knowledge about modality (what is possible and what is necessary), and what might this mean for arguments in philosophy of religion which appeal to such modalities? To what extent may practical considerations figure in one’s decision about whether to believe theism (or atheism)?

Such questions, as most philosophers will tell you, are unlikely to have neat and tidy answers. Yet how we go about pursuing such answers enables us to think more carefully and more deeply about religious commitments in ways that can benefit both the religious and non-religious alike.

Featured image credit: Abbey arches by Pexels. Creative Commons via Pixabay

The post Revitalizing the Epistemology of Religion appeared first on OUPblog.

June 15, 2018

Andy Warhol’s queerness, unedited

“I think everybody should like everybody” is one of Andy Warhol’s most iconic quotes. If you type it into Google image search, you get back a grid of dorm-room posters, inspirational desktop wallpaper, t-shirts, and baby onesies. Seeping into popular culture, Warhol’s quote has become a simple, cheeky mantra for how to live the good life—a reminder to get back to the basics. Wouldn’t the world be better if we all just liked one another? Even a baby knows that. It’s the sort of quote that fuels Warhol’s enduring reputation as “the great idiot savant of our time”—as the influential critic Hal Foster once put it.

Image credit: Grid generated by typing the phrase “I think everybody should like everybody” into Google image search. Screenshot by Jennifer Sichel.

Image credit: Grid generated by typing the phrase “I think everybody should like everybody” into Google image search. Screenshot by Jennifer Sichel.However, things are not as simple as they seem. Lurking beneath the surface of this particular quote is a fraught history involving the excision of an entire, sophisticated, wistful discussion about homosexuality.

The quote comes from a defining interview Warhol conducted with art critic Gene Swenson, published in the magazine ARTnews in November 1963. As it was printed in ARTnews, the exchange between Warhol and Swenson goes like this:

Warhol: I think everybody should be a machine.

I think everybody should like everybody.

Swenson: Is that What Pop Art is all about?

Warhol: Yes. It’s liking things.

Swenson: And liking things is like being a machine?

Warhol: Yes, because you do the same thing every time. You do it over and over again.

Swenson: And you approve of that?

Warhol: Yes, because it’s all fantasy.

But that is not how the conversation really transpired. In March 2016, I uncovered an unknown, original tape-recording of the interview, stashed away in a box among Swenson’s papers. On tape, the exchange between Warhol and Swenson actually goes:

Warhol: … Well it has to be something like the idea that, uh, uh… that all Pop artists aren’t homosexual. And it really doesn’t… you know… And everybody should be a machine, and everybody should be, uh, like…

Swenson: I don’t understand the business about – if all Pop artists are not homosexual, then what does this have to do with being a machine?

Warhol: Well, I think everybody should like everybody.

Swenson: You mean you should like both men and women?

Warhol: Yeah.

Swenson: Yeah? Sexually and in every other way?

Warhol: Yeah.

Swenson: And that’s what Pop art’s about?

Warhol: Yeah, it’s liking things.

Swenson: And liking things is being like a machine?

Warhol: Yeah. Well, because you do the same thing every time. You do the same thing over and over again. And you do the same…

Swenson: You mean sex?

Warhol: Yeah, and everything you do.

Swenson: Without any discrimination?

Warhol: Yeah. And you use things up, like, you use people up.

Swenson: And you approve of it?

Warhol: Yes. [laughing] Because it’s all a fantasy…

As you can see, every reference to homosexuality and sex was expunged from the published interview, line by line. This happened across the board. Swenson begins the interview by asking Warhol, “What do you say about homosexuals?”—a question Warhol goes on to answer with great care and complexity, but is nowhere reflected in the published version. Listening to the tape, we learn that in Warhol’s “fantasy” it wouldn’t really matter whether a Pop artist is or isn’t “homosexual” because the stark division between homosexuality and heterosexuality falls away. And it falls away not because everybody celebrates his or her distinctness, but rather because everybody likes everybody and does the same thing all the time, including “sex” and “everything you do.” Warhol thus responds to Swenson’s question “What do you say about homosexuals?” with a confounding, provocative queer fantasy that undermines the distinction between homosexuality and heterosexuality, thereby making room for different forms of difference.

How did these dramatic excisions happen? For the most part, we don’t know. In another recorded interview, Swenson says that it was Tom Hess, executive editor at ARTnews, who “cut out all those words.” But the details are murky, and no paper trail has surfaced charting what happened in those final edits. We also know that Swenson went on to rail against the art establishment in a series of impassioned writings and disruptive protest actions. He waged public battles against publishers and curators over their culpable willingness to abet injustice by suppressing disruptive social, political and queer content during the 1960s.

As it turns out, Warhol’s simple mantra “I think everybody should like everybody” contains a whole story of censoring and queer fantasy—a story that is far from simple.

Featured image credit: Balloon by movprint. CC0 via Pixabay .

The post Andy Warhol’s queerness, unedited appeared first on OUPblog.

A good death beyond dignity?

According to the Australian euthanasia activist Philip Nitschke, to choose when you die is “a fundamental human right. It’s not just some medical privilege for the very sick. If you’ve got the precious gift of life, you should be able to give that gift away at the time of your choosing.” This view combines two extreme standpoints in the debate on euthanasia and assisted suicide: First, it claims that that you should be allowed to end your life as you please, unbound by further qualifications such as a grim medical diagnosis; and second, it says that we should treat this decision with utmost importance, as a claim right which can hardly be overridden by conflicting considerations.

As one normative consequence of this idea, you might think that ending your own life should be as easy and comfortable as possible. To this end, Nitschke, together with the Dutch engineer Alex Bannink, has developed the ”Sarco” (from “sarcophagus”, an ancient coffin made of stone or other durable materials). On the images available online, the device looks like a means of transportation, with a futuristic design and a cockpit-like pod that rests on a stand. And indeed, its main purpose is to allow its user to make their final journey “with elegance and style”, as Nitschke put it. After successfully completing an online questionnaire which tests for mental fitness, the person seeking death gets an access code for entering the pod. When the user once more has confirmed their choice to die, nitrogen is released to bring down the oxygen level in the pod cabin, rendering the person unconscious and killing them shortly thereafter.

One common concern with these types of mental tests is that they are executed not by a psychiatric specialist, but proceed AI-driven. Also, even people whose mental health is beyond doubt make all kinds of irrational decisions: Being in the grip of a fear or feeling forced by your social environment can lead you to ill-informed decisions, even if you are perfectly healthy by any common measure. Moreover, people can make all sorts of rational, but unwise or even silly choices they later regret; and while one might think that they nonetheless have a right to do so, one still can reasonably doubt whether this supports the kind of fundamental human right Nitschke has in mind: After all, nothing less than your very existence is at stake when you are about to enter Sarco, so one would have wished for a few more safety measures, all the more because the developers plan to make the design plans publicly available in 2019.

While I believe that personal autonomy certainly has a role to play in any promising conception of a good death, I am much more doubtful whether a dignified end really comprises nothing more than the end each individual would choose for themselves.

These considerations notwithstanding, let’s focus on yet another issue. One of the self-proclaimed aims of the Sarco is to bring the idea of a peaceful death to a new level: While euthanasia activists usually equate a “peaceful death” with a “dignified death”, Nitschke thinks that we can do ‘better.’ He asserts that his suicide machine elaborates on “the possibility of feeling not just dignity at the end, but of feeling euphoric. […] In a creative twist on my previous ‘have the best death you can’ proposition, the Sarco adds the extra layer of ‘feel your best.’” In line with this idea, the Sarco homepage welcomes its visitors with the tagline “What if we had more than mere dignity to look forward to on our last day on this planet?”

The picture suggested here is one of two variables for a good death, where a euphoric death of the sort Nitschke has in mind improves upon a dignified death. There are good reasons, however, to believe that not only severe suffering and pain may prevent people from having a “death with dignity”, but also that a death as envisaged by Nitschke and his co-designer will do the same. For the euphoric mood that the Sarco induces in its users is not the kind of contentment you experience when you are comfortably surrounded by your loved ones in the final moments of your life. On the contrary, Sarco’s killing mechanism allows you to feel good at the price of mental clarity and orientation. Nitschke compares this feeling with an experience he had during his Air Force days: “I was asked to write a letter to a friend while they lowered the oxygen level in my training chamber. I wrote rubbish, but it seemed like happy euphoric rubbish when I was re-reading it at ground oxygen level.”

However, this feeling of mental disorientation is precisely what many people associate with an undignified death. In a survey conducted in 2006 by Harvey Chochinov and colleagues, 211 patients with terminal cancer in its final stage were asked about their “sense of dignity”. One of the items in the researcher’s list that the vast majority of patients (77.3 %) identified as a negative factor relating to dignity was “Not being able to think clearly.” If these people are right, we might question how dying by hypoxia – being poisoned due to the exposure of nitrogen – can assure a dignified end when the state of mind accompanied by this counts as undignified in the eyes of many.

Perhaps Nitschke would admit this: “The Sarco will not be for everyone, that’s clear.” Maybe he would argue that what counts as a dignified death, or at least certain aspects of it, is also subject to the subjective attitudes of the affected person. And maybe this is explained by the assumption that a dignified death is a death that conforms with a person’s authentic values and wishes. While I believe that personal autonomy certainly has a role to play in any promising conception of a good death, I am much more doubtful whether a dignified end really comprises nothing more than the end each individual would choose for themselves. Some good deal of research has been done on this topic over the last years, and with some notable exceptions, the majority of the results deny that we should simply equate a dignified death with an autonomous one.

Featured image credit: Ocean Sunset Photo by Gabriel Garcia Marengo. Public Domain via Unsplash .

The post A good death beyond dignity? appeared first on OUPblog.

June 14, 2018

Top 10 facts about the giraffe

This June, people around the globe are marking World Giraffe Day, an annual event to recognise the bovine dwellers of the African continent. While these long-necked herbivores remain a firm favourite of the safari, there remains much about the giraffe which is relatively unknown. In order to celebrate our Animal of the Month, we bring you 10 amazing facts about the giraffe.

Image credit: Giraffe by Rachel Hobday. CC by 2.0 via Flickr.

Image credit: Giraffe by Rachel Hobday. CC by 2.0 via Flickr.1. Heady heights

Giraffes are the world’s tallest land mammal, standing on average between 4-6 metres tall. They are also the biggest species of ‘ungulates’, or hooved animals. This is in large part due to their long legs and necks, which extend to around 1.5 metres each.

Image credit: Giraffe by Barbara Willi. CC by 2.0 via Flickr.

Image credit: Giraffe by Barbara Willi. CC by 2.0 via Flickr.2. The Camel-Leopard

The modern word giraffe probably stems from the Arabic zarāfa, from the Ethiopian zarat, meaning ‘slender’. But in ancient Greek and archaic English, giraffes were known as ‘camelopards’ (καμηλοπάρδαλις), from the combination of the Greek words for camel and leopard. Giraffes were seen as a mixture of these two animals on account of their camel-like, bovine features and yellow-brown, leopard-like fur.

3. Giraffe Family Tree

There is only one major species of giraffe alive today, but there are actually as many as nine different sub-species’ roaming the African continent:

Image credit: Giraffe by David Kornfeld. CC by 2.0 via Flickr.

Image credit: Giraffe by David Kornfeld. CC by 2.0 via Flickr.· West African Giraffe

· Kordofan Girffae

· Nubian Giraffe

· Rothschild’s Giraffe

· Thornicroft’s Giraffe

· Reticulated Giraffe

· Masai Giraffe

· Southern (or Cape) Giraffe

· Anglolan (or Smoky) Giraffe

These variations include differences in colour—from the blonde West African Giraffe to the darker Masai Giraffe—and territorial ranges, from North-West to Southern Africa.

4. Varied Diet

It is a well-known fact that giraffes evolved long necks in order to feed on the highest branches, but this also allows them to feed on a wide range of plants. Giraffes munch on over 100 different species’ of leaves, roots, flowers, and pods, meaning they have one of the most varied diets of all animals.

Like most of us, however, giraffes have their favourite foods—they are most likely to be found snacking on Acacia and Combretum plants.

5. Tongue Twisters

Giraffes didn’t only evolve long necks to reach the juiciest leaves at the top of the tree—they also have incredibly long and powerful tongues. A giraffe’s tongue can extent up to 45cm, easily stripping a tree of its juiciest leaves.

A giraffe’s tongue is also noticeably dark in colour. Some researchers have argued that this is an evolutionary trait to avoid sunburn while feeding on the Savannah.

Image credit: Giraffe tongue by William Warby. CC by 2.0 via Flickr.

Image credit: Giraffe tongue by William Warby. CC by 2.0 via Flickr.6. Potential Predators

Despite their large size, giraffes are sometimes predated by other animals. Lions will sometimes hunt these giant creatures, and in Kruger National Park giraffe accounts for an estimated 43% of a lion’s diet. On rare occasions they have also fallen prey to other African creatures such as crocodiles and cheetahs.

Image credit: Lionness in KNP by Marc Eshcenlohr. CC by 2.0 via Flickr.

Image credit: Lionness in KNP by Marc Eshcenlohr. CC by 2.0 via Flickr.Young giraffes are much more susceptible to predation. Smaller carnivores like hyenas can pose a particular threat to giraffe calves, but adults have also been known to use their size and strength to kill predators attempting to hunt them.

7. En Pointe

Giraffes are ‘ungulates’, or hooved animals. Unlike primitive mammalian limbs, which extend into five digits, ungulates have lengthened and compressed their metapodial bones—the long bones at the ends of human hands and feet. This means that they actually walk on tiptoe, much like a ballerina.

8. Need for Speed

A giraffe’s long neck isn’t just for reaching leaves. These creatures have evolved to use their necks for momentum, allowing them to run faster (over 30 miles per hour at their top speeds), propel themselves upwards from a sitting position, and provide balance.

9. Necking and Clubbing

Giraffes also use their long, powerful necks to assert their dominance. Sub-adult male giraffes engage in so-called “necking contests”, in which they intertwine their necks, wrestle, and butt against each other for 30 minutes or more.

Image credit: P1013247 by Richard Evea. CC by 2.0 via Flickr.

Image credit: P1013247 by Richard Evea. CC by 2.0 via Flickr.These contests allow young males to establish dominance in their cohort’s hierarchy, develop their neck muscles, and hone their jousting skills. Adult males rarely engage in aggression, but when they do they swing their necks violently to deliver resounding blows with their heads, like clubs. Unsurprisingly, giraffes have thick skulls to protect against concussions from such impacts.

10. Conservation

While giraffe populations in Eastern and Southern Africa remain stable, and are even growing on privately owned game ranches, populations across West Africa and the northern parts of East Africa have been shrinking for many years.

Giraffes face overhunting and habitat degradation. Trees are chopped down for firewood and to create grazing land for livestock; the size of the animals and the amount of meat they provide results in large-scale poaching; the animal’s distaste for fences makes giraffes targets for farmers looking to protect their livestock.

Image credit: 055 by Becker1999. CC by 2.0 via Flickr.

Image credit: 055 by Becker1999. CC by 2.0 via Flickr.In the Sahel—a region of land between the Sahara and Sudanian Savanna—giraffe populations have been shrinking for many years. However they remain among the last indigenous large mammals to survive in the area. While other browsers lost out to competition with domestic livestock, the evolutionary traits of the giraffe have allowed these creatures to continue feeding on branches above the heads of these competitors.

Featured image credit: Giraffe herd by Kim Vanderwaal. CC by 2.0 via Flickr .

The post Top 10 facts about the giraffe appeared first on OUPblog.

C.P. Snow and thermodynamics, 60 years on

It’s nearly 60 years since C.P. Snow gave his influential “Two Cultures” lecture, in which – among many other significant insights – he advocated that a good education should equip a young person with as deep a knowledge of the Second Law of Thermodynamics as of Shakespeare. A noble objective, but why did Snow highlight this particular scientific law? There are many others – such as those associated with Newton or Einstein – that are more well-known. Isn’t the Second Law of Thermodynamics rather obscure?

Well, unless you happen to be a full-time hermit, living in total isolation, then you experience the Second Law much more frequently than you might realise.

For example, when you’re in a hurry, and you throw your mobile phone charger into a bag and run off. Later, when you retrieve the charger, the cable is tangled. How did that happen? Is there a tangle-gremlin in your bag, delighting in making the tangle as scrambled as possible?

Another example: when you’ve been working really hard all day, and you open the door of a teenager’s room to find yourself reeling from the sight. Why doesn’t Sam ever put clothes back on the hangers, and into the drawers? How can Alex make such a mess?

These are two every-day examples of the Second Law of Thermodynamics. Why so? Because the key feature of this law is that many processes naturally take place in one direction only: it is ‘natural’ for a charger cable to become tangled; it is ‘natural’ for a teenager’s room to become untidy. These ‘natural’ processes occur ‘all by themselves’, and do not require specific explanations or causes – they just happen.

What is ‘unnatural’ is for the change to take place the other way: untangling that cable doesn’t ‘just happen’, any more than a teenager’s room will become tidy ‘all by itself’, however much we might wish that it did!

Importantly, the Second Law doesn’t say that an ‘unnatural’ change is impossible – what it says is that an ‘unnatural’ change cannot happen of its own accord, spontaneously, ‘by itself’. If an ‘unnatural’ change takes place, then something else must be going on too – and the Second Law tells us is that the ‘something else’ required is the expenditure of energy. To untangle that cable, you need to work at it; and tidying that teenager’s room can require a lot of energy indeed – and, very often, not the energy of the teenager!

Image credit: “Chaos Clutter A Mess Things Stuff Apartment Room” by Hans. CC0 via Pixabay.

Image credit: “Chaos Clutter A Mess Things Stuff Apartment Room” by Hans. CC0 via Pixabay.More fundamentally, the Second Law tells us that ‘ordered’ states (the neatly coiled cable, the teenager’s tidy room) will, of their own accord, become ‘disordered’ (the tangled cable, the untidy room). This transition from order to disorder is a ‘natural’ phenomenon, and the only way for the transition to take place the other way, from disorder to order, is by consuming energy.

So, once you’ve untangled the cable and tidied that irksome room, you sit down and relax. Maybe you’re watching a football match on the television; maybe you’re listening to Dave Brubeck. And, once again, you are experiencing the Second Law. Think, for a moment, about a high-performing team — say, a top-flight football club or the Dave Brubeck Quartet. A key characteristic of all high-performing teams is that they sustain a high degree of order over time. The football players aren’t ambling randomly around the pitch: rather, the movements of all the players, and of the officials too, are highly co-ordinated, as determined by what is happening in the game at any moment; and even if the bass player in the Brubeck quartet is improvising, that improvisation is done in the context of the overall piece, blending imaginatively with the other players. High-performing teams sustain order over time. Football teams. Jazz quartets. That team you’re part of at work.

But is that team at work a high-performing team or just a bunch of people thrown together and called a ‘team’ because that’s the language of the work-place? My experience is that very few work-place teams are ‘high-performing’ in the sense I am using the term – and once again I come back to the Second Law. As I have described, the Second Law states that the ‘natural’ tendency is for order to degrade into disorder. This implies that high-performing teams are rare, and difficult to sustain. At the start, of course, ‘teams’ are formed in a spirit of optimism, but, sooner or later, they can fall apart. People bicker. Somebody fails to deliver. Someone else thinks the team leader is doing the wrong thing. What started with the noble intention of being a high-performing team degenerates into a rabble, with a small core of the conscientious doing all the work so that the team is not seen from the outside to fail.

This is the Second Law – from order to chaos. Unless. Unless there is a continuous flow of energy into the team to counteract the ‘natural’ process of disintegration, to sustain order over long periods of time, the order that is a fundamental characteristic, and requirement, of a high-performing team.

Where, then, does this energy come from? Firstly, from you. Each team member has an obligation to keep their own energy up, for we all know how debilitating it is to work with someone else who is politely described as ‘high-maintenance’. And secondly from the leader. A key — if not the key — attribute of leadership is the injection of energy into others. And many of the words we use to describe great leaders —inspirational, enthusiastic, committed, energising — reflect this. Which explains why leadership is so tiring.

So every time we untangle that cable, tidy that mess, or are part of a team, we are experiencing the Second Law. Maybe C.P. Snow’s exhortation that understanding the law should be part of everyone’s education has rather more validity than we might initially think.

Featured image: Colour by rawpixel. Public domain via Pixabay .

The post C.P. Snow and thermodynamics, 60 years on appeared first on OUPblog.

Five things you might not know about Edmund Burke

Edmund Burke (1730-1797) was an Irishman and a prominent Whig politician in late 18th century England, but he is now most commonly known as “the founder of modern conservatism”—the canonical position which he has held since the beginning of the 20th century in Britain and the rest of the world. But it took a great deal of time for Burke’s complex and various intellectual productions on Ireland, America, India, France, and British politics—which took the form of books, letters, pamphlets, and periodical contributions—to be boiled down to a neat, though rather vague, body of political principles, usually identified as tradition, historicism, religion, property, and hostility to abstract thinking. Below is a list of five other things you may not know about the legacy of Edmund Burke.

1. Burke was heavily criticized in his lifetime and in the years following his death.

Burke was depicted as a suspected Jesuit, a deathbed Catholic convert, and his speeches were so long Burke gained the nickname “dinner-bell.” His Irishness led to denunciations of his “adventuring” and one commentator mocked his oratory as “stinking of whiskey and potatoes.” After his passionate denunciations of the French Revolution, many in his party branded him intellectually inconsistent and his writings on France the ravings of a madman.

2. Burke was greatly admired by Liberals in Victorian Britain—but only to a point.

Mid-Victorian Liberal men of letters such as John Morley, Leslie Stephen (the father of Virginia Woolf), and James Fitzjames Stephen (Leslie’s brother) sought to recover Burke as a substantial intellectual figure in the history of ideas. To these Liberals, the French Revolution was increasingly seen as not simply a social and political transformation, but also a new ‘stage’ of human intellectual life. In addition, Burke was an increasingly relevant thinker to a society preoccupied with notions of slow, gradual, developmental change within a broadly empirical framework.

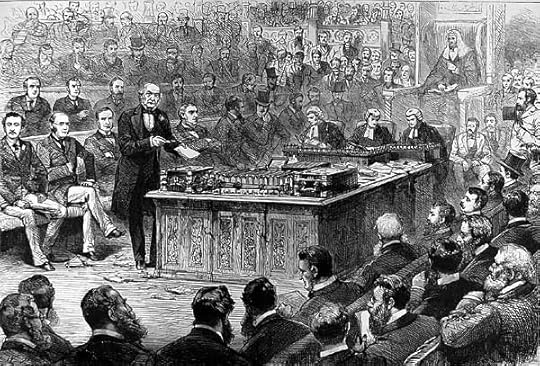

Image credit: Image credit: William Gladstone during a debate on Irish Home Rule in the House of Commons on 8 April 1886. Illustrated London News. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: Image credit: William Gladstone during a debate on Irish Home Rule in the House of Commons on 8 April 1886. Illustrated London News. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.3. Burke was an important source of inspiration in the debates over Irish Home Rule.

The dominant Liberal figure of the 19th century was William Gladstone, a towering intellectual moralist with a powerful oratorical style. When Gladstone, as Liberal Prime Minister, introduced the second reading of the first Irish Home Rule Bill in Parliament on 8 April 1886, he did so with the support of Edmund Burke: he stated that he had come to his conclusion through his readings of Burke, and he expressed a sincere wish that his supporters and detractors would do the same. What followed was a Burkean reading revolution, which had significant results for the legacy of Burke and the identity of the Liberal Unionists, who broke from Gladstone over the question of Irish devolution in 1886.

4. Burke was once central to English Literature syllabi in schools and universities.

Burke’s speeches may not have been much fun to listen to (if you believe his 18th century detractors), but his eloquent prose style was what kept people reading Burke, even when he was politically out of fashion. So, when new schools and universities were created—and as the academic disciplines taught in those institutions expanded to include history, English, and the ‘moral’ as well as the natural sciences—Burke found himself placed in the Premier League of English Literature and was taught alongside Chaucer, Shakespeare, and Milton.

5. Burke wasn’t christened “the founder of conservatism” until 1912—115 years after his death.

It was only with the development of academic studies of Burke’s “political philosophy” that Burke was widely recognised as a significant and—most importantly—consistent thinker, and that this body of thought was best labelled “conservative.”

Featured image credit: ‘Cincinnatus in Retirement. falsely supposed to represent Jesuit-Pad driven back to his native Potatoes. see Romish Common-Wealth.’ Caricature of Edmund Burke by James Gillray. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons .

The post Five things you might not know about Edmund Burke appeared first on OUPblog.

How (un)representative is the British political class? [QUIZ]

The fact that the British political class doesn’t fully reflect the diversity seen in the population as a whole is hardly news. However, many people don’t fully appreciate exactly how unrepresentative its members are, or the specific (and sometimes slightly odd) ways in which the political class differs from Britain as a whole.

This unrepresentativeness is something that we should all be concerned by. First, the current lack of diversity within the political class means that we might be missing out on original thinking and new ideas that could help to solve policy problems that have dominated British politics for decades. Second, it violates the principle of political equality on which our democratic system of government is based. To put it another way, the fact that certain groups of society appear to be systematically excluded from holding positions of political power calls into question whether British democracy truly lives up to its name?

To learn more about exactly who is in the political class and, as important, who is not, take this quiz.

Featured image credit: hierarchy-human-man-woman by geralt. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post How (un)representative is the British political class? [QUIZ] appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers