Oxford University Press's Blog, page 246

June 22, 2018

Securing the future of the Male Voice Choir

During a ‘question and answer’ session at a recent music convention, four contemporary composers of choral music faced a plethora of musicians from all types of backgrounds and traditions. Amongst a selection of interesting and searching questions asked, one brought an eerie silence to the room. The question was: ‘Would you consider writing for a male choir?’

The reaction of the panel was fascinating. Two of the composers looked confused and bemused, and didn’t respond. One of the composers responded readily with ‘‘I’d be delighted to write for any choir who was interested in my music.’’ The final composer was heard to guffaw and grimace in a way to suggest that something rather distasteful had happened.

Male choirs in the UK are, perhaps like the ‘choral society’, facing an uncertain future—as demonstrated by the panel of composers’ attitudes as described above. Borne out of working for religious environments that now cease to be; their very base of existence is no longer deemed popular by younger generations.

Steeped in tradition, they are often unaccepting of contemporary choral repertoire and staunchly at home performing the same works for many years. There is little commissioning of new and original works for the unique sound of a male choir, and they generally keep a proud distance from choral or conductor education.

It is easy to see why the reputation of the male choir stymies its own recruitment of members, stifles its vocal and choral development, and threatens its very existence as a tradition in the UK. To an extent, male voice choirs in the UK have become a parody of themselves, whereas this has been avoided in other countries.

Despite this, it is hoped that even the most steadfast opposers of single sex choirs would not wish to see the male choir tradition disappear forever. But how can they survive?

Members of a male choir are welcomed into a micro-society that is warm, caring, supportive, humorous, and very sociable. Most male choirs have a visible set of rules that govern how it is run, and a distinct structure with a visible leader in its conductor or musical team. Members are expected to perform from memory, having learnt up to eighteen pieces of music by heart (per concert); high levels of loyalty and commitment are the norm.

But choirs thrive on always looking forward and developing their skills and musicality in new, exciting and contemporary ways. Audiences cannot fail to be impressed by a choir that has exciting and ambitious musical plans. Contemporary choirs work with composers and publishers in producing new music to premiere whilst also being unafraid to perform much loved choral treasures. They reach out to local communities to co-work with them in supporting new ventures, competitions, workshops and educational projects.

This attitude is something that the traditional male choir might struggle with, and the question is whether is it time for them to embrace the inevitably required paradigm shift in thinking to ensure that they can remain a successful, appropriate, and appreciated part of today’s society? At the very least they should be asking themselves:

How far away are they from contemporary or popular choral repertoire?

How can they develop an audience of newcomers to the genre?

How can they make themselves irresistible to a younger generation of singers?

Is the content and design of their musical programmes relevant to today’s concert go-ers?

And how can they change the attitudes of three out of the four composers on the panel mentioned at the beginning of this article?

Two examples of choirs who are embracing change are Peterborough Male Voice Choir and London Welsh Male Voice Choir.

The former has been ‘reborn’ with an ambitious artistic vision which points the way to a great future whilst the latter has actively commissioned and championed new and contemporary music for male voices.

Both choirs have readily embraced good vocal health and development at the core of what they do and this ‘new core ideals’ policy has attracted noticeable numbers of men in their twenties and thirties—having clear goals and a demonstrative vision is attractive and bears much fruit. And both choirs do not necessarily spend a whole concert singing ‘on a stage’ but might perform in all sorts of shapes and formations, seeking the best performance per musical item.

Perhaps it is time for all of us to take stock with regard to this treasured tradition of the male voice choir, support it, and encourage it into fusing with contemporary choral music, whilst preserving its musical heritage for future generations to appreciate and enjoy.

Featured image credit: © John Downing MBE. Used with permission.

The post Securing the future of the Male Voice Choir appeared first on OUPblog.

June 21, 2018

Law Teacher of the Year announced at the Celebrating Excellence in Law Teaching conference

Oxford University Press hosted its annual Celebrating Excellence in Law Teaching Conference at Aintree Racecourse in Liverpool on 20 June.

Playing a central role at the conference were the six Law Teacher of the Year Award finalists. Delegates learned what it was that makes them such exceptional teachers, and heard first–hand about their teaching methods, motivations, and philosophies. The conference concluded with current Law Teacher of the Year, Nick Clapham of the University of Surrey, naming Lydia Bleasdale of the University of Leeds as this year’s winner.

Lydia was thrilled, and admitted her desire to take home the accolade:

I wanted to win the award for three reasons… to show my seven-year-old daughter the positive impact that working parents, in particular, working mums can have. I also wanted to win it because of my students and for the law school as a whole – I can’t emphasize enough the support the law school at Leeds give those who want to excel at teaching.

Lydia also paid an emotional tribute to her colleague Nick Taylor, who was her personal tutor at university. Without his support, she said she would not be here.

The conference brought together over 70 law academics for a day of discussion, workshopping and celebration. Sessions included some of the hottest topics in higher education and legal education today:

· OUP editors shared findings of their market research and publishing plans ahead of the launch of the Solicitors Qualifying Examination

· Michael Fay hosted a panel session with students on student mental health, its impact on academics, and practical initiatives to employ

· Warren Barr of Liverpool University and part of the business and law TEF panel shared his insights from the TEF subject level pilots.

The other Law Teacher of the Year finalists were:

· Lana Ashby, Durham University

· Kevin Brown, Queen’s University Belfast

· Amy Ludlow, University of Cambridge

· Richard Owen, Swansea University

· Verona Ni Drisceoil, University of Sussex

We’d like to thank all speakers, delegates, students and everyone involved for helping to make Celebrating Excellence in Law Teaching 2018 such a brilliant and inspiring occasion.

Image courtesy of Oxford University press and Natasha Ellis-Knight.

The post Law Teacher of the Year announced at the Celebrating Excellence in Law Teaching conference appeared first on OUPblog.

Competing territorial and maritime claims in the South China Sea

The Spratly Islands are small. In fact, this remote archipelago is just a collection of rocky islets, atolls, and reefs scattered across the southern reaches of the South China Sea. The Spratlys are so barren and barely above sea level that they could not support permanent settlements until recently. The Spratlys lack arable land, freshwater supplies, and apparent natural resources. The Spratlys seem unlikely contenders to make world headlines.

Yet the Spratlys’ diminutive physical stature belies their outsized role in international relations and geopolitics. In actuality, the islands are pivotal in a strategic rivalry between the surrounding countries of Brunei, China, Malaysia, the Philippines, Taiwan, and Vietnam, as well as countries farther afield including Australia, India, Indonesia, Japan, and the United States. The crux of the deepening dispute involves conflicting claims of sovereignty over the Spratlys among the littoral countries and freedom of navigation through the region more generally. In that sense, the quarrel over the Spratlys resembles a typical territorial dispute where governments disagree on the borderlines between their jurisdictions.

Yet in this case, the actual prize is not territory. Rather, the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) grants countries sovereignty over territorial waters extending twelve nautical miles out and the right to establish an exclusive economic zone stretching two hundred nautical miles outward from each sovereign landmass. It is not ownership of the Spratlys that is coveted but rather control over the surrounding waters, which include productive fisheries and potentially significant, but undocumented, undersea oil and gas deposits. The Spratlys dispute has also inflamed domestic public opinion and nationalist fervor, complicating efforts for the relevant governments to compromise without appearing to lose face. The Spratlys also sit astride some of the world’s busiest shipping lanes.

Given that, control over each speck of land can be leveraged to assert control and privileges over prime maritime real estate and airspace with implications for economic development, geopolitical rivalries, and domestic politics. This further highlights how the world remains very bordered. In fact, the beginning of the 21st century has seen growing attention directed toward marking out maritime sovereignty, most notably in the Arctic, Antarctic, Oceania, and, of course, the South China Sea.

Image credit: Map of the Spratly and Paracel Islands in the South China Sea by NASA. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: Map of the Spratly and Paracel Islands in the South China Sea by NASA. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.The rival claimants to the Spratlys base their arguments on a mixture of history, geography, and international law. These arguments are highly selective and reflect parochial national interests. Thankfully, this international jostling has generally unfolded through relatively mundane actions, such as air and sea patrols, scientific expeditions, and the erection of monuments and flagpoles marking the limits of de facto control. Unfortunately, these rather symbolic steps have occasionally escalated into testy diplomatic exchanges, military shows of force, the establishment of military outposts, and even deadly skirmishes.

The dispute settled into a stable, if unresolved, status quo with claimants exercising de facto control over portions of the archipelago while denying competing claims. The situation took a dramatic turn during 2013 when the Philippines began legal proceedings challenging China’s so-called “nine-dash line” that claimed most of the South China Sea, including the Spratlys. An UNCLOS arbitration tribunal concluded in 2016 that China’s claims lacked legal merit but left unresolved the underlying issue of rightful ownership. China rejected the ruling, so the tribunal did little to change the situation. These varied actions and reactions highlight how borders can be thought of a process in which function and meaning are continually made and remade.

Whether coincidental or not, China launched large-scale dredging operations at several locations in the Spratlys by the end of 2013. These operations served several objectives. First, the dredging created port facilities to accommodate larger ships. Second, the excavated sand was encased within retaining walls to raise and expand adjacent landmasses. Finally, this reclaimed land ultimately solidified into new artificial islets that are rapidly transforming into military installations.

Some of these former reefs are now permanent islets supporting military bases with long-range aircraft and anti-aircraft and anti-ship missile batteries, as well as auxiliary facilities to support permanent garrisons. The novel combination of land reclamation and military-infrastructure construction is suggestive of borders operating as a form of political technology influencing international relations and domestic politics.

Image credit: South China Sea claims map, July 2012 by Voice of America. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: South China Sea claims map, July 2012 by Voice of America. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Combined with similar projects in the Paracel Islands to the north, China has acquired an unrivaled presence across the South China Sea. Yet these developments prompted rival claimants to undertake similar projects. The United States has also made a point of commencing regular freedom of navigation missions to affirm its position that these are international waters and airspace.

The Spratlys appear poised to play an outsized role in jockeying for influence in Southeast Asia and across the broader Indo-Pacific region. International cooperation aimed at the development of natural resources could help build trust and erode the zero-sum mentalities informing so much decision-making regarding the Spratlys. Beyond resource extraction, environmental tourism offers a foundation for longer-term sustainable development, but large-scale dredging and construction could disrupt the region’s sensitive and unique ecosystems.

And even here, the fledgling tourism industry in the Spratlys often unfolds within the subtext of normalizing territorial claims. Government-sponsored tour groups featuring flag raising ceremonies and other patriotic celebrations, promulgated through social media and nationalist media outlets, as well as the patrols of prominently flagged ships and aircraft, are in different ways types of performances. They flag, literally and figuratively, government policy toward territorial and maritime sovereignty.

The Spratlys are a peculiar archipelago but simultaneously illustrate how borders manifest through the dynamic interplay between varied spatial processes, performances, and technologies. The Spratlys are also rather remote and inaccessible but simultaneously increasingly central to international relations and geopolitical strategy throughout the Indo-Pacific region. These trends show little signs of abating.

Featured Image credit: The USS John S. McCain conducts a routine patrol in the South China Sea, Jan. 22, 2017 by Navy Petty Officer 3rd Class James Vazquez, United States Navy. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons .

The post Competing territorial and maritime claims in the South China Sea appeared first on OUPblog.

Numbers and historical linguistics: a match made in heaven?

Whatever you associate with the term “historical linguistics,” chances are that it will not be numbers or computer algorithms. This would perhaps not be surprising were it not for the fact that linguistics in general has seen increasing use of exactly such quantitative methods. Historical linguistics tends to use statistical testing and quantitative arguments less than linguistics generally. But it doesn’t have to be like that.

Linguistics generally has seen an increase in the use of corpora and quantitative methods over the recent years. Yet journal publications in historical linguistics are less likely to use such methods. Part of the explanation is no doubt the advantage that linguistics for extant languages holds regarding greater availability of annotated text corpora and people who can answer questionnaires or take part in experiments. Yet this can only be part of the explanation.

Although historical records are clearly patchy and biased, there is nevertheless much information that can be processed quantitatively. For instance, there is an increasing variety of computational language resources available for historical language varieties. Similarly, the computational and statistical tools for processing and using these resources are becoming increasingly open and easy to use.

Second, historical linguistics has a long tradition of quantitative methods. Going far back in time, historical linguistics has been informed by statistics, counting, and quantitative measures. However, this way of doing historical linguistics has never been mainstream, in the sense that it is not the typical or most frequent way of doing research in historical linguistics.

This suggests a golden opportunity: why not use probabilities to estimate changes in language? Or use statistics to measure similarity between varieties? Or crunch numbers in order to describe the chances that a phenomenon did or did not occur in the past, given the available yet inevitably patchy evidence? After all, these are precisely the scenarios that quantitative techniques are ideal for.

Why not use probabilities to estimate changes in language? Or use statistics to measure similarity between varieties?

In short, there is nothing inherent in the field of historical linguistics that suggests it should not make greater use of quantitative techniques. An interesting metaphor to describe this state of affairs is what is known as the technology adoption curve. The curve takes the form of a bell curve covering all potential users. On the far left, where the curve is thin, we find the early adopters, those who will pick up new technology either out of sheer curiosity or because they think it will give them an advantage. Moving right, where the peak of the bell curve sits, we find the majority of users, who will only adopt a new technology when it is convenient or when other choices are becoming inconvenient. Between these groups, the early adopters and the large majority, there is a metaphorical gap, or chasm. For any new technology, crossing this chasm is the key to success.

Looking at linguistics as a whole, it appears that quantitative methods have indeed crossed that chasm and gone mainstream. Research papers in leading journals are increasingly making use of statistical techniques to support their linguistic arguments. Rather than a paradigm shift, this can be viewed as quantitative techniques being adopted by the majority and going mainstream, to the extent that some may feel they are being pressured to use such techniques.

Conversely, historical linguistics seems to have resisted this trend to a greater degree. It is reasonable to look to cultural explanations for this. After all, the technical barriers keep getting lower and the availability of resources keep increasing. So what is special about historical linguistics? For one thing, historical linguistics (at least if we consider the historical-comparative method) has a very long, very stable, and very successful history. The methodological core of the historical-comparative method has proved remarkably stable over time.

Furthermore, there is a history of failed attempts at using quantitative methods in historical linguistics. In some cases, such techniques have been tested and simply failed to work, as one would expect in any scientific endeavour. In other cases, the lack of extensive quantitative modelling by historical linguists have enticed scholars from other fields, with experience in statistical models, to step in and fill that gap. These endeavours have met with mixed reactions from mainstream historical linguistics.

What seems to be missing is a positive case for using quantitative methods in historical linguistics, on the premises of historical linguistics. That, in our view, is the only way that quantitative techniques can properly cross the chasm into adoption in mainstream historical linguistics. Such a positive case must go well beyond training manuals or statistics classes. Instead, the intellectual footwork for integrating numbers with the core questions that historical linguistics faces must be done.

By outlining a set of principles for integrating numbers and historical linguistics, we set out to provide the basis for such a positive case. These principles support a transparent, data-driven form of research, that can build upon and complement—but does not replace—traditional historical linguistics research. Further work is surely needed to drive this positive change, including how theories of linguistic change more directly can incorporate statistical components. Yet the present does look like a promising time for historical linguistics to cross the quantitative chasm.

Featured image credit: Binary damage code by Markus Spiske. CC0 via Flickr.

The post Numbers and historical linguistics: a match made in heaven? appeared first on OUPblog.

Holographic hallucinations, reality hacking, and Jedi battles in London

In 1977, Star Wars: Episode IV – A New Hope captivated audiences with stunning multisensory special effects and science-fiction storytelling. The original Star Wars trilogy sent shockwaves of excitement through popular culture that would resonate for years to come. Beyond the films themselves, the Star Wars universe extended into a wider sphere of cultural artefacts such as toys, books and comics, which allowed audiences to recreate and extend the stories. This imaginative play also spilled out into other areas of culture. For instance, ‘dark side’ rave music tracks sampled James Earl Jones’s iconic Darth Vader speech (e.g. New Atlantic – ‘Yes to Satan‘, 1991), while James Lavelle’s UNKLE project used dialogue snippets on tracks like ‘Unreal‘ (on Psyence Fiction, 1998) and the sounds of TIE fighters on the ‘Rock On‘ (1997) collaboration with Rammellzee. Inspired partly by his collection of Star Wars toys, James Lavelle‘s Mo’Wax label would even release a series of action figures based on the designs of graffiti artist Futura.

Today Star Wars and other works of science-fiction continue to inspire artists and technologists. In May 2018, James Edward Marks’s Psych-Fi collective presented the fourth edition of #Hackstock: May the Fourth as part of the Sci-Fi London film festival. Designed to coincide with the day of 4 May, or what fans call ‘Star Wars day’ (“May the 4th be with you”), #Hackstock is an event that draws the connections between sci-fi, psychedelia, counter-culture and immersive technologies. This year’s event featured a dazzling array of virtual reality (VR), augmented reality (AR) and immersive experiences. Among these, Psych-Fi’s own award-winning #HackThePlanet VR app is stylised as a digital psychedelic (or ‘cyberdelic‘) experience, plunging the viewer through a maze of circuit boards and electronic beats enhanced with a wearable vest that shakes your chest with the bass. Created in collaboration with composer Simon Boswell, the immersive film pays tribute to the movie Hackers (1995) and psychedelic guru Timothy Leary, who championed “the PC [as] the LSD of the ’90s”.

Elsewhere at #Hackstock there were PlayStation VR titles, retro games, brainwave-controlled sonic artworks, Metal Mickey (the robot from an 80s TV show), a Jedi Talkaoke pop-up chat show, and of course, the Star Wars-themed Jedi Challenges (2018), an augmented reality game in which you wield a light-sabre and battle against storm troopers. Jedi Challenges uses new augmented reality technology (the Lenovo Mirage AR headset) to provide a holographic experience. As with VR, you wear a headset, yet here the display blends the real world around you with the synthetic virtual world of the game; thus storm troopers appear as if they are in the actual location where you are playing it. This taps into the holographic special effects of the original Star Wars films, which saw R2D2 project a spectral Princess Leia and battle Chewbacca at holo-chess. With the latest AR headsets, ideas that were once the domain of science-fiction fantasy are fast becoming a reality.

The #Hackstock event also included a demonstration by DoubleMe, who are exploring the use of these AR technologies for communications. Using the Microsoft Hololens, DoubleMe are working on a holographic system which allows a person to be 3D-scanned and reproduced in a remote location, effectively allowing a hologram of that person to appear anywhere in the world. DoubleMe envision this as a new form of communication, where people will project synthetic 3D digital versions of themselves, and collaborate in virtual environments that are superimposed on real-world spaces. This opens up staggering possibilities for remote communications, which could be used for keeping in touch with loved-ones over long distances, carrying out medical consultancies, and much more besides. At the moment these technologies are at the prototype stage, but as the AR headsets come down in price, systems like this could soon enter into widespread use and transform the way we interact online.

The possibilities of these new augmented reality technologies are incredibly exciting, though as in the science fiction movies, there may also be cause for concern. For instance, Keiichi Matsuda’s short film Hyper Reality (2016) depicts a kaleidoscopic dystopia of the near future, where a dazzling mesh of synthetic computer graphics advertisements has completely enclosed over the real physical world. Certainly in the cities, this may be a world we are rapidly heading towards. Increasingly our lives are mediated through digital experiences, yet how much of our humanity is lost in the process of representing our digital selves? There may not be any easy answers, but of course, science-fiction is precisely the domain in which these questions can be explored, so it is fitting to include an event like #Hackstock as part of the Sci-Fi London Film Festival. By presenting sci-fi and counter-culture ideas alongside these emerging new technologies, #Hackstock is encouraging questioning, repurposing and dreaming — and as we enter a brave new world of pervasive augmented and mixed realities, that could be a very important thing.

#Hackstock 4.0. Photo credits: The People Speak, PsychFi, Sci-Fi-London, Dirty Urchin, DoubleMe, Phil Tidy and Chris Harvey, 2018.

#Hackstock 4.0. Photo credits: The People Speak, PsychFi, Sci-Fi-London, Dirty Urchin, DoubleMe, Phil Tidy and Chris Harvey, 2018.

#Hackstock 4.0. Photo credits: The People Speak, PsychFi, Sci-Fi-London, Dirty Urchin, DoubleMe, Phil Tidy and Chris Harvey, 2018.

#Hackstock 4.0. Photo credits: The People Speak, PsychFi, Sci-Fi-London, Dirty Urchin, DoubleMe, Phil Tidy and Chris Harvey, 2018.

#Hackstock 4.0. Photo credits: The People Speak, PsychFi, Sci-Fi-London, Dirty Urchin, DoubleMe, Phil Tidy and Chris Harvey, 2018.

#Hackstock 4.0. Photo credits: The People Speak, PsychFi, Sci-Fi-London, Dirty Urchin, DoubleMe, Phil Tidy and Chris Harvey, 2018.

#Hackstock 4.0. Photo credits: The People Speak, PsychFi, Sci-Fi-London, Dirty Urchin, DoubleMe, Phil Tidy and Chris Harvey, 2018.

#Hackstock 4.0. Photo credits: The People Speak, PsychFi, Sci-Fi-London, Dirty Urchin, DoubleMe, Phil Tidy and Chris Harvey, 2018.

#Hackstock 4.0. Photo credits: The People Speak, PsychFi, Sci-Fi-London, Dirty Urchin, DoubleMe, Phil Tidy and Chris Harvey, 2018.

#Hackstock 4.0. Photo credits: The People Speak, PsychFi, Sci-Fi-London, Dirty Urchin, DoubleMe, Phil Tidy and Chris Harvey, 2018.

Featured image: Section of ‘Holo_Point_Break’ by Jon Weinel, 2018. Image used with permission.

The post Holographic hallucinations, reality hacking, and Jedi battles in London appeared first on OUPblog.

June 20, 2018

The Oxford Etymologist waxes emotional: a few rambling remarks on fear

It is well-known that words for abstract concepts at one time designated concrete things or actions. “Love,” “hatred,” “fear,” and the rest developed from much more tangible notions. The words anger, anguish, and anxious provide convincing examples of this trend. All three are borrowings in English: the first from Scandinavian, the second from French, and the third from Latin. In Old Norse (that is, in Old Icelandic), angr and angra meant “to grieve” and “grief” respectively. But in Gothic, a Germanic language known from a fourth-century translation of the New Testament, the adjective aggwus (pronounced as angwus) meant “narrow.” Being (metaphorically) in “a narrow place”—between the hammer and the anvil, for example, or between the Devil and the deep sea—produced anger and anguish. Modern German still has enge “narrow” and Angst “fear.” Angst has even made it into English, along with Schadenfreude, Weltschmerz, and a few other German words for troublesome emotions.

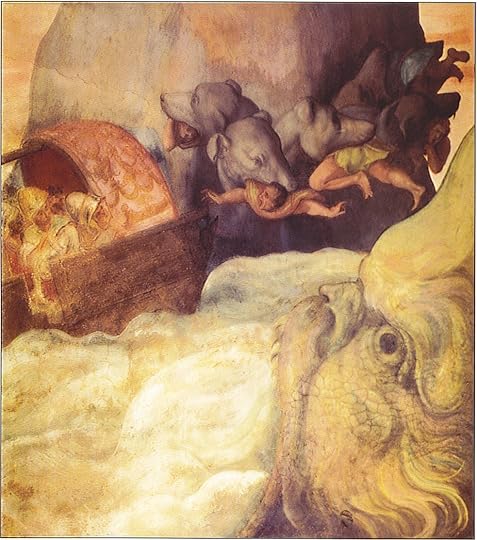

It is hard not to feel fear in a narrow place. Image credit: painting of Odysseus’s boat passing between the six-headed monster Scylia and the whirlpool Charybdis by Alessandro Allori. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

It is hard not to feel fear in a narrow place. Image credit: painting of Odysseus’s boat passing between the six-headed monster Scylia and the whirlpool Charybdis by Alessandro Allori. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.The development from “narrow” to “pain; extreme unease” is not only a Germanic phenomenon. Related to German enge are Russian uz-kii “narrow” and uzh-as “horror” (the root once had n after the vowel), Latin angor “anxiety,” and their cognates in the Iranian languages (Sanskrit and Avesta), Celtic, and Baltic. Engl. anger turned up close to the end of the twelfth century, in Ormulum, a poem mentioned in this blog more than once. Anguish appeared in texts more or less at the same time. Anxiety, anxious, and angina are the latest newcomers from Romance. Angina suggests stenosis, which is indeed a narrowing of a passage in the body, a spasm in the chest (Greek stenós “narrow”). Stenography “writing in shorthand” is a much more peaceful word, but it has the same Greek root.

We observe a similar picture, wherever we look at words designating fear. For instance, the relatively innocent English verb startle belongs here. In Old English, steartlian meant “to kick; struggle.” In some British dialects, it still means “to rush.” Even in Shakespeare’s days, to startle meant “to cause to start.” But when we start or are made to start something with surprise, we are startled. Much more dramatic examples are German Schreck “fright” and schrecken “to frighten.” A thousand years ago, the verb meant only “to jump up,” and a trace of it has been retained in the German name of the locust (Heuschrecke, that is, “hay jumper,” which modern speakers take for “hay horror”). We jump up in fear, when we are startled; hence schrecken. The noun Schreck is a so-called back formation from the verb; it looks as though schrecken were from Schreck, but this impression is wrong. However, a noun derived from a verb by back formation is indeed most unusual. As a rule, the process goes in the opposite direction: kidnap form kidnapper, babysit form babysitter, and so forth. Adjectives are also occasionally curtailed in this way: compare sleaze from sleazy.

Medieval ferries looked quite different from ours! Image credit: Project for sailing ships upstream by Unknown. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Medieval ferries looked quite different from ours! Image credit: Project for sailing ships upstream by Unknown. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Strangely, the origin of the noun fright, though it has congeners all over Germanic, is obscure Comparison with numerous words in Greek, Latin, Tocharian, and other languages is unrevealing, because those putative relatives also mean “fright” and therefore tell us nothing about the possible initial meaning. It seems that the word is specifically Germanic. Naturally, it has been suggested that its origin should be sought in the substrate (some non-Indo-European language of the indigenous population of the lands later settled by Germanic speakers). Since nothing is known about that mysterious language or the conditions under which fright was presumably borrowed, we, who are not faint-hearted, will let this hypothesis be and go on.

The folk etymological idea of the locust being horror is more to the point than the real one. Image credit: Garden locust (Acanthacris ruficornis), Ghana by Charles J Sharp. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The folk etymological idea of the locust being horror is more to the point than the real one. Image credit: Garden locust (Acanthacris ruficornis), Ghana by Charles J Sharp. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.As a consolation prize, we are allowed to examine fear. Old Eng. fær (long æ) meant “sudden calamity, danger.” Its cognates have instructive meanings: “ambush” (Old Saxon); “ambush; stratagem; deceit” (Old High German); “misfortune; damage; enmity” (Old Norse). In earlier German, “fear” also turned up as one of the senses of those words. Ambush looks like an ideal semantic basis for “fear,” but, of course, it can be a derivative, rather than the source of “fear” (we are afraid and think of an ambush, the place of great danger: one never known who is hidden in the bushes round the corner; perhaps there is an ambush there).The Modern German noun for “fear” is Gefahr, and, among its older meanings, we find “deceit” and “pursuit, persecution.” All in all, the idea the word fear conveyed was rather probably connected with “pursuit” and “ambush.”

Image credit: The Scarecrow of Batman cosplayer at the 2014 Amazing Arizona Comic Con at the Phoenix Convention Center in Phoenix, Arizona by Gage Skidmore. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: The Scarecrow of Batman cosplayer at the 2014 Amazing Arizona Comic Con at the Phoenix Convention Center in Phoenix, Arizona by Gage Skidmore. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons. If panic is from Pan, couldn’t there be some pre-Germanic god Furht, from whose name we have fright? Image credit: Illustration page 102 of the book Collection of Emblems or Table of Sciences and Moral Virtues by Jean Baudoin. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

If panic is from Pan, couldn’t there be some pre-Germanic god Furht, from whose name we have fright? Image credit: Illustration page 102 of the book Collection of Emblems or Table of Sciences and Moral Virtues by Jean Baudoin. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.In English, the native word met Anglo-Norman afrayer “to alarm, startle, frighten,” whose past participle eventually yielded afraid, but fear seems to have developed independently of its partial French look-alike. It may be worthy of note that folk etymology connects German Gefahr with the verb fahren “to travel.” Its English cognate is fare (the noun and the verb: pay your fare, she fared pretty well; farewell), but its reconstructed Indo-European root por is of unclear origin. Be that as it may, even though in old days travel was fraught with danger, Gefahr is not a product of fahren (Old Engl. faran).

By contrast, Engl. ferry is indeed a congener of fare (verb). Some verbs are related the way sit is related to set (I wanted to write “as lie is related to lay,” but then thought better of it and left that pernicious pair alone). Set means “to cause one (or something) ‘to sit’.” That is why such verbs are called causative. Occasionally they are easy to recognize (set versus sit poses no problems; neither does raise next to rise). Others have a more, even much more complicated history: thus, the causative of drink is drench (hard to guess!), and the “real” causative of rise is rear: raise is a borrowing from Scandinavian and is irregular form the phonetic point of view. (Startle, in its obsolete meaning “to make start” would be a causative of start.) The causative of Old Engl. faran was ferian, Modern Eng. ferry. The German causative verb of fahren is führen, known only too well from Führer.

Above, I expressed doubts about the substrate origin of fright. But of course, nouns and verbs meaning “fear” can be borrowed. Such are Engl. horror, terror, and panic (panic goes back to the name of the Greek god Pan, whose shouts struck terror in the hearts of those who heard them). However, English is a special case: in the Middle Ages, it absorbed thousands of French words and later added numerous words taken over from Latin. Yet to justify the idea of a loan word from a substrate, one needs more than the historical linguist’s inability to find that word’s origin. In any case, let us rejoice that heebie-jeebies is a native coinage. The word’s author is the American cartoonist W. B. Beck, who used it in his comic strip Barney Google (1923). Just Google for it. Another native word is dread, the subject of the next installment.

Featured Image: Only a narrow escape is possible from this script. Featured Image Credit: A selection of George Halliday’s journal written in Pitman shorthand by George Halliday. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The Oxford Etymologist waxes emotional: a few rambling remarks on fear appeared first on OUPblog.

Refugees, citizens, and camps: a very British history

Today, very few people think of Britain as a land of camps. Instead, camps seem to happen “elsewhere,” from Greece to Palestine to the global South. Yet during the 20th century, dozens of camps in Britain housed tens of thousands of Belgians, Jews, Basques, Poles, Hungarians, Anglo-Egyptians, Ugandan Asians, and Vietnamese. The camps jumbled together those who fled the crises of war and empire. Hungarians and Anglo-Egyptians competed for spaces when they disembarked in 1956, victims of, respectively, the Soviet invasion of Hungary and Nasser’s expulsion of British subjects from Egypt during the Suez Crisis; Ugandan Asians arrived in 1972 to find Poles still encamped from three decades earlier.

“Refugee camps” in Britain were never only for refugees. Indeed, it was impossible to segregate citizens and refugees. The Irish poor bunked with Belgians in flight, English women moved into camps to join their Polish husbands, while homeless Britons squatted in camps designed for foreigners. This was no rosy tale of multicultural harmony. But the contact between refugees and citizens—unsettling though it may have been—made it impossible for Britons to think of refugees only as different from themselves. This is one of the most crucial lessons that Britain’s camps, now largely forgotten, have to offer.

Many camps were peopled with British squatters, as refugees shared space—willingly or not—with Britons who had been ousted from their homes by bombs and poverty. Britons were often trying to get into the camps, while refugees were trying to get out of them. Although now we might think of camps as absolutely segregating refugees and citizens, 20th century camps often highlighted their closeness.

During the Second World War, millions of homes in Britain were damaged or destroyed; many others fell to slum clearance. Tens of thousands of Britons occupied army camps: a desperate response to this housing crisis. These squatters referred to themselves as “refugees” from overcrowding. But this was not just a metaphor. British squatters took over camps earmarked for or already occupied by Poles. In 1946, British ex-servicemen occupied a camp in Buckinghamshire that had been slated for Polish soldiers’ wives, and refused to vacate the premises. Some of these squatters were families that councils had refused to place in houses, because they were seen as unsatisfactory tenants. Refugee camps, then, could be places to stash British “problem families.”

Image credit: Photograph of Ugandan Asian family at Tonfanau by Jim Arnould, Nova (April 1973).

Image credit: Photograph of Ugandan Asian family at Tonfanau by Jim Arnould, Nova (April 1973).Along with demobilized British soldiers and bombed-out civilians, others made their way to Polish camps. In 1950, at the Kelvedon Camp for Poles in Essex, the National Assistance Board added a reception center for British vagrants. Poles and Britons slept separately, but shared clothing, a warden, and a doctor. Caring for Polish refugees and homeless Britons exhausted Kelvedon’s warden, who worried about “dissatisfying both populations.” He complained that the two groups were conspiring against him—Polish doctors happily handed out certificates to British vagrants stating that they were medically unfit to work.

Migrants, too, moved through spaces intended for refugees. Kaz Janowski, a Polish refugee who spent his childhood at Kelvedon, recalled “the steady flow of disheveled-looking [English] rustics,” as well as “gypsy” caravans moving through the camp and wayfarers sleeping in the camp ditches as they chose. Henry Pavlovich, who lived at the Polish camp at Foxley, recalled that as Polish families began to leave the camp, Irish and African Caribbean families took their place. Mixed communities sprang up. Pavlovich’s father, a trumpet player, forged casual friendships with the African Caribbean residents, intrigued by the Calypso music they brought with them to the Polish camp, and the drums they made from large oil cans or food tins. By contrast, the English and Irish residents of Foxley seemed to Pavlovich “totally unpredictable and uncomprehending about everything.”

As these stories suggest, refugee camps in Britain brought a startling variety of people into contact, creating unique intimacies and frictions. In 1972, hundreds of Ugandan Asians found themselves huddled over heaters in wartime wooden sheds at Tonfanau, a remote army camp in North Wales. This unlikely scene prompted even more unlikely encounters between people who surely would otherwise never have met. Margretta Young-Jones, who volunteered at Tonfanau, proudly recalled how she and a Ugandan Asian matriarch pricked their fingers and mixed their blood so she could be considered another “daughter.” Her young son, Edwin, was shocked by his first taste of a raw chili pepper at Tonfanau; Young-Jones described their shared meal as the start of a “beautiful friendship.”

The interactions between refugees and citizens can’t be easily characterized as hostility or benevolence, prejudice or tolerance. Instead, they reveal a morally complicated story about empathy, solidarity, and activism. As the global refugee crisis once again brings to Europe the challenges of mass encampment, we would do well to remember that refugee camps reflect how a society treats all people in need—foreign or domestic.

Featured image credit: Polish children at Foxley Camp. Photograph by Zbigniew Pawlowicz, by kind permission of his son, Henry Pavlovich .

The post Refugees, citizens, and camps: a very British history appeared first on OUPblog.

How nations finance themselves matters

To understand how nations should finance themselves it is fruitful to look at how corporations finance themselves, how they divide their financing between debt and equity.

Corporations typically issue equity when they need financing for a new profitable investment opportunity, when their shares are overvalued by the stock market, or when they need to raise funds to service their debt obligations.

But what is the equivalent of “equity”—shares sold for a stake in a company—for a country? The logical parallel here is “fiat money”: government decreed paper currency. Fiat money issued by a sovereign nation is analogous of equity issued by a corporation. Both are essentially pro-rata claims on wealth.

Linking a nation’s monetary economics to a corporate finance framework yields several important insights. First, it makes clear that money issuance in practice, like equity issuance, is in exchange for something, for a nation’s investment or other expenditures. The point is that fiat money does not drop from the sky, as suggested by a well-established but misleading idea in monetary economics, the notion of helicopter money. There is no such thing as money dropping from a helicopter. Indeed, the existence of money predates that of helicopters.

Second, this framing makes precise what the costs of inflation are. Inflation costs are similar to equity dilution costs, which are incurred by shareholders when a firm issues new shares to new shareholders at a price below the shares’ true value. An important result in corporate finance is that when a firm issues more shares through a rights offering, there cannot be any dilution of ownership. Equity dilution is only possible if the new shares are acquired at a favorable price by new shareholders. This is how the new shareholders increase their pro-rata ownership share at the expense of old shareholders. Similarly, inflation costs materialize only when the new printed money a nation issues disproportionately favors new holders. That’s how the purchasing power of existing holders of money is eroded. In sum, the cost of inflation is the redistribution of wealth caused by it. Inflation without redistribution does not result in a cost for the citizens of a country.

The question of how to conduct monetary policy boils down to a determination of what money buys. If what is bought is worth more, the expansion in money supply increases the country’s welfare.

When a company issues new shares at a favorable price to the new shareholders it does so, presumably, because the proceeds from the share issue are worth more to the old shareholders than foregoing the share issue entirely. The fresh funds raised may be used to undertake valuable new investments or to reduce the company’s debt burden. Similarly, a nation may be better off expanding its money supply, even at the cost of greater inflationary pressures if the expansion of the money supply finances valuable public expenditures or helps reduce a high debt burden. But when to print more money, and what is the right growth rate of M2? In essence, the question of how to conduct monetary policy boils down to a determination of what money buys. If what is bought is worth more, the expansion in money supply increases the country’s welfare.

A striking example is China. China’s central bank (PBoC) has been criticized for having printed too much money over the past three decades, based on its high M2 growth rates (often over 10% per year and on occasion over 30%). But China’s inflation has been quite low and stable, and its GDP growth rate has been almost 10% per year over the same period. The PBoC has, in effect, issued equity to finance valuable investment opportunities. Similarly, The US Federal Reserve has allowed M2 growth rates to reach around 30% per year for a few years during World War II, and at the end of the war the US economy reached the stunning size of about 50% of the world output. These are two striking examples of monetary policy that resemble the equity issuance policy of a firm with lots of growth opportunities.

Another striking example is that of the Swiss National Bank’s response to the increase in the global demand for safe assets following the financial crisis of 2007-2009. It responded by purchasing foreign exchange assets in exchange for Swiss Francs. It was thus able to add to the Swiss national wealth roughly one year’s worth of output essentially for free! The Swiss National Bank did what corporations do when they face a stock market bubble: they issue more shares!

A classical tradeoff in corporate finance that helps explain corporations’ choices between debt and equity financing is the tradeoff between the expected default and debt overhang costs associated with debt financing and the equity dilution costs associated with equity financing.

A similar tradeoff can be articulated for nations. National governments must balance likely inflation costs from an increase in money supply against the alternative—relying on financing from foreign-currency debt, which could result in default and debt overhang costs. In general, a country must weigh these conflicting risks, in order to decide how much wealth it derives from money issuance, and how much from international borrowing.

Finally, this corporate finance analysis can also help understand the benefits of a monetary union and the costs of abandoning monetary sovereignty. When is it appropriate for a nation to give up its right to issue money, by adopting a currency board or joining a currency union, such as the Euro? Doing so, essentially means foregoing the possibility of printing money and relying only on debt financing. The Argentinian debt crisis in 2000, a few years after it had adopted a currency board, and the Euro-area debt crisis of 2011-2013 can be seen as examples illustrating the costs of foregoing monetary sovereignty and relying exclusively on foreign-currency debt financing. Argentina eventually defaulted at huge cost and abandoned the currency board. The Euro area policymakers have been able to avoid default and put out the fire, essentially by printing more money, but clearly more needs to be done to fix the structural problem of an over-reliance on debt financing.

To conclude, applying a corporate finance framework to nation states reveals, among other things, that monetary policy cannot be reduced to a simple formula, an inflation target, or a quantity rule. It reveals that monetary policy cannot be framed independently of the exchange value of money and of foreign exchange reserve management. Also, by focusing on what money buys, a new perspective can be obtained on so-called unconventional monetary policies and the costs and benefits of quantitative easing.

Featured image credit: Singapore River Skyline Building by cegoh. Public domain via Pixabay .

The post How nations finance themselves matters appeared first on OUPblog.

June 19, 2018

The evisceration of storytelling

In his seminal essay “The Storyteller,” published in 1936, the German philosopher Walter Benjamin decried the loss of the craft of oral storytelling marked by the advent of the short story and the novel. Modern society, he lamented, had abbreviated storytelling.

Fast forward to the era of Facebook, where the story has become an easily digestible soundbite on your news feed or timeline. The popular stories on social media are those that are accessible. Complexity is eschewed in an effort to create warm and relatable portraits of others who are just like us. If modern society abbreviated storytelling, the digital era has eviscerated it.

In recent times, carefully crafted narratives with predetermined storylines have been used in philanthropy, diplomacy, and advocacy. From the phenomenon of TED talks and Humans of New York, to a plethora of story-coaching agencies and strategists, contemporary life is saturated with curated stories. “Tell your story!” has become an inspirational mantra of the self-help industry. Narrative research centers have emerged to look at the benefits of storytelling in areas from treating depression to helping new immigrants build community. An avalanche of books on the topic like Jonathan Gottschall’s “The Storytelling Animal” and Jonah Sachs’ “Winning the Story Wars” present storytelling as an innate human impulse that can help us to navigate life’s problems and change the world for the better.

But are stories really the magical elixir we imagine them to be?

Not in the curated form of storytelling that has come to reign. Curated stories omit the broader context that shapes the life of the storyteller. This was the case with the heartrending stories of abuse told by migrant domestic workers in New York to legislators in Albany as they campaigned for a Domestic Workers Bill of Rights in 2010. At one legal hearing, a Filipina worker related how her employers accused her of stealing a box of $2 Niagra cornstarch. Another spoke about how her male employer frequently exposed himself to his staff. And one West Indian domestic worker recounted that her employer violently beat her and called her the n-word. But these stories – limited in duration and subject to protocols – could not say why migrant women were so vulnerable and undervalued, and why they were forced to migrate for work. Instead, workers could speak only to the technical conditions of their employment. As a result, the stories encouraged the idea that the abuses were the result of a few bad employers who could be reined in by legislation, rather than a vastly unregulated global industry.

If modern society abbreviated storytelling, the digital era has eviscerated it.

The Italian narrative theorist Alessandro Portelli says that when we tell stories, we switch strategically between the modes of the personal, the political, and the collective. The contemporary boom of curated storytelling has involved a shift in emphasis away from collective and political modes of narration toward the personal mode. An online women’s creative writing project features personal stories written by women in Afghanistan. In one piece, Leeda tells the story of fifteen-year old Fershta. The girl is given by her father in marriage to a violent man who beats her and kills her seven year old brother. Leeda concludes that it is the father’s bad behavior that has led to this horrific situation. Other stories blame Afghan mothers for allowing violence to be perpetuated. Because the stories don’t often address the social or political backdrop of war and poverty, we have little means to understand the desperation that might lead a father to pull his daughters out from school and marry them off. As readers, we are helpless voyeurs without an avenue for effective action.

It has become increasingly common for stories to be harnessed for utilitarian goals – like a legislative victory or registering people to vote. For instance, during Barack Obama’s electoral campaigns, volunteers were trained to tell two-minute stories that they deployed when canvassing voters. While legislative campaigns and voter recruitment may be worthy goals, they require that stories be whittled down to a dull and formulaic soundbite that can be delivered in a legal hearing or a recruitment drive. Immigrant families who visited the offices of senators to tell their stories and ask for the passage of Comprehensive Immigration Reform (CIR) in 2010 seemed to be weary of reciting their stories all day long. And it’s not even clear that this strategy works. While activists mobilized to tell stories and extract promises for a bill that would never pass, legislators were busy passing anti-immigrant bills like SB 1070.

One response to this capture of storytelling has been refusal. Some prefer to remain silent rather than give in to the logic of the soundbite, to the reduction of their selves to a blurb that can fit within the lines of a grant application or legal protocol.

Others go off script. They employ their artistic skills to render their stories in all their depth and complexity. One group of domestic workers from the New York-based South Asian organization Andolan said that they did not want to speak any longer about simple narratives of exploitation and victimhood. They said that publicly telling stories of abuse can backfire for workers, who may have a harder time finding work. They preferred to go “off message” to talk about their families or the Liberation War in Bangladesh. These workers want to tell stories about the complicated nature of transnational lives.

Curated storytelling has extended deep into contemporary social life and political and cultural institutions. Curated stories package diverse histories and experiences into easily digestible soundbites and singular narratives of individual victims. The impact has been to deflect our attention from structurally defined axes of oppression and to defuse the oppositional politics of social movements. Perhaps, in response, we should heed Benjamin’s call for more deeply contextualized and complex storytelling – the slow piling of thin, transparent layers, one on top of the other – so much needed in today’s world.

Featured image credit: Black white vintage by rawpixel. Public domain via Unsplash.

The post The evisceration of storytelling appeared first on OUPblog.

How deaf education and artificial language were linked in the 17th century

Before the 1550s, it was generally believed that people who are born deaf are incapable of learning a natural language such as Spanish or English. This belief was nourished by the observation that hearing children normally acquire their speaking skills without explicit instruction, and that learning to read usually proceeds by first connecting individual letters to individual speech sounds, pronouncing them one by one, before a whole word is read and understood. Accordingly, it seemed obvious to many that, in the authoritative words of Aristotle, “written marks (are) symbols of spoken sounds.” Thus, for deaf children the road to learning a language like English seemed to be blocked forever. Acquiring speech by listening and imitating was obviously impossible. Written communication seemed equally unattainable, for if what is primarily signified by written letters (speech sounds) is not accessible to a person, there is no way such a person could learn to read.

In the 1550s, a Benedictine monk in northern Spain showed that this belief is untenable. His name was Pedro Ponce de Leon. He succeeded in teaching reading, writing, and, most spectacularly, speaking to a number of profoundly deaf children. Ponce defied the view that written language primarily symbolizes speech, as he taught his pupils first to read and write, without reference to speech sounds, “indicating with his finger the things that were signified to them by characters.” It was only at the next stage that he started teaching speech, “prompting them to make the movements of the tongue corresponding to the characters.” He thus showed that “just as it is better for hearing people to start with speech, so for those who have their ears blocked it is better to start with writing,” as the medical writer Valles put it in De sacra philosophia.

Other teachers followed in Ponce’s footsteps, but initially the practice was confined to Spain. In the seventeenth century, teaching language to deaf people became a topic of interest in Britain: in the 1660s, several members of the newly founded Royal Society acted as teachers of deaf pupils. These were William Holder and John Wallis, who both saw such teaching as an experiment corroborating their phonetic theories.

They became embroiled in a dispute about who was most successful in teaching Alexander Popham, a boy born deaf. Although Alexander’s speaking skills were at the centre of the dispute, it is clear that reading and writing also formed an important part of his instruction.

Image credit: Title page of the notebook used by Wallis to teach Popham.

Image credit: Title page of the notebook used by Wallis to teach Popham. Not all those concerned with teaching language to the deaf agreed that speech should be included. A radical position in this regard was taken by George Dalgarno, the author of an artificial language meant for universal use and claimed to be more logical than existing languages. Dalgarno’s project was part of a movement that was partly inspired by a growing awareness of the variety of possible notational systems. In particular, when scholars learned about Chinese script, it became clear that written language was not necessarily tied to speech sounds. Chinese characters were seen as so-called “real characters,” that referred to things rather than to words. In this respect, they were like Arabic numerals, and chemical or astronomical symbols. Since symbols of this type can be associated with different words in different languages, they seemed to open the way to the creation of a universal writing system. Just as the symbol “4” refers universally to the number called differently in different languages (“four,” “quatre,” etc.), so could symbols referring to all things be contrived, or so it was believed, in order to generate a universal script.

In pursuance of such a “universal character” Dalgarno eventually produced his artificial language. By the time he published it, he no longer intended his invention to be a universal writing system only, but a language that could be spoken as well as written. This aspect of his project was seen as a flaw by his critics, who considered a universal writing system as a useful invention for international communication, but saw an artificial language as rather an additional obstacle to it. Dalgarno wrote at great length explaining why this view was mistaken. The circumstance that he used the Latin alphabet, and that his language could thus be pronounced, did not detract from the fact that the written form of his language could function as a free-standing system, unconnected to speech.

In the 1660s, the distinction between “real characters,” i.e. non-phonetic writing, representing “things,” and “vocal characters,” i.e., phonetic writing, representing spoken words, was well-established. For Dalgarno, however, the question whether a certain piece of writing was “real” or “vocal” could not be decided on the basis of its intrinsic characteristics. Rather, it depended on the use made of it. If one chose to disregard pronunciation, his language, or any other written language for that matter, it could function as a real character! When Dalgarno formulated this insight in reply to his critics, he stated, probably unknowingly, a view that had guided Pedro Ponce a century earlier in his teaching of deaf children, connecting objects directly with written words.

Dalgarno eventually saw the implications of this view for the education of the deaf. In a tract on the subject published in 1680 (‘The Deaf and Dumb Man’s Tutor”), he explained that it was best to make full use of the potential of alphabetically written language. He envisaged the use of a finger alphabet, which worked by associating parts of the fingers with letters.

Image credit: Dalgarno’s finger alphabet.

Image credit: Dalgarno’s finger alphabet. If deaf people were trained from the cradle in the use of this alphabet, he believed, this visual system would become as natural to them as audible words are to hearing children. Dalgarno did not discuss the teaching of speech to the deaf, probably because he believed that a better, visual alternative was available. However, his visual communication system was tied to languages such as English and completely different from sign language.

Featured image credit: “Letter2” by Thomas Misnyovszki. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post How deaf education and artificial language were linked in the 17th century appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers