Oxford University Press's Blog, page 243

July 3, 2018

The end-of-life sector needs concrete solutions to be truly person-centred

In recent years the language used to describe what constitutes good end-of-life care has changed. ‘Shared-decision making’, ‘patient autonomy’, ‘choice’ and ‘advance care planning’ have become buzzwords. This is to be welcomed, of course, but has the sector really changed in practice? According to several policy reports, in addition to feedback from people who use end-of-life services, not particularly.

We wanted to explore some of the barriers that prevent people from receiving the care and treatment that’s right for them, so we spoke to hundreds of people nearing the end of their life and their carers via questionnaires, focus groups, and in-depth interviews, and found that some basic needs are not being met.

People reported not being given clear information about their symptoms, prognosis, or treatment options. When people did want more information, they didn’t always know the right questions to ask in order to obtain it. Many felt they weren’t always supported to make meaningful choices about their care and treatment. Opportunities to instigate important conversations about future care planning were missed. Where people didn’t feel empowered to make informed decisions about their care, it sometimes had a direct impact on care quality.

Specific insights included “I did not feel well informed on the last day of my mum’s life”; “I wasn’t prepared for health professionals not giving you the information you need or not answering questions at all”. Another noted that “one major thing we’ve learned is that you should never assume that information is shared between professionals”, for instance between the NHS and care homes. Others stressed the need to “be strong – you may have to push” to get all the information you need, and that they “wished they’d known what questions to ask.”

Healthcare professionals are in need of practical solutions just as much as those they are caring for.

In light of these findings, it is hardly surprising that person-centred end-of life care remains elusive for many people.

In contrast, those who were able to have open conversations about death with loved ones and healthcare professionals said that they felt more in control and prepared for what may lie ahead. Clearly there is much we can do to facilitate more of these positive exchanges and make them the norm, not the exception, for people faced with a life-changing diagnosis.

Calls for policy changes are certainly needed to help address these issues in the longer term, but we also urgently need tangible solutions that will make an immediate and vital difference to people currently living with terminal illness and those around them.

Healthcare professionals are in need of practical solutions just as much as those they are caring for. Although many will be experienced in treating terminally ill patients, as one physician we consulted noted, “not all doctors are good at communication”. Our interactions with a range of healthcare professionals who care for and treat people with life-limiting illnesses have shown that many have a desire to encourage more open conversations on what is often an emotive topic, or to complement the current high standard of compassionate end-of-life care already being provided by their organisation.

To provide a catalyst and a guide for some of these difficult conversations, we developed a booklet using the first hand insights gained through our research, primarily designed for people newly diagnosed with a terminal illness. Any tools that can also guide and inform an open, honest, two-way decision-making process between patients and healthcare professionals are to be welcomed. We must respond to some of the shortfalls exposed by our research with practical responses alongside longer term transformational change, and there certainly appears to be an appetite among health and care professionals for tools that can help them day-to-day to provide more person-centred care. Without practical resources that support patients to have meaningful conversations with healthcare professionals about their personal values and preferences, ‘person-centred care’ will continue to remain merely a buzzword and not reality.

Featured image credit: hospice caring nursing-elderly by unclelkt. Public domain via Pixabay .

The post The end-of-life sector needs concrete solutions to be truly person-centred appeared first on OUPblog.

July 2, 2018

How Wayfair opens the door to taxing internet sales

In a much anticipated decision, the US Supreme Court in South Dakota v. Wayfair, Inc. declared, by the narrowest of margins, that a state may require an internet seller to collect sales and use taxes even if the seller lacks physical presence in the state seeking to impose the obligation to collect its tax. In Wayfair, five justices in an opinion by Justice Anthony Kennedy overturned the Court’s 1992 decision in Quill Corp. v. North Dakota. Quill had held that a state may enforce a sales or use tax collection obligation only if a retailer has physical presence in the state.

Wayfair is an important decision, though much of the popular reporting about it has been overstated. Internet and mail order sales have always been taxable to the consumer making the purchase. The problem has been that most internet and mail order consumers ignore their legal obligation to self-report their remote purchases and pay the tax themselves. However, in recent years, sellers like Amazon have increased their sales tax collection activity as they expanded their physical presence in different states by building distribution centers and conventional brick-and-mortar stores.

While only five justices favored overruling Quill, no justice thought that the physical presence rule makes sense in 2018. The divide in Wayfair was between those justices who concluded that the Court itself should overturn the physical presence test and those justices who preferred for Quill, and the physical presence test to be adjusted or reversed by Congress.

The Court’s decision of Wayfair overturning Quill and the physical presence test changes the political dynamics of taxing internet sales. Any state can now adopt South Dakota’s remote seller statute and be confident that its law is constitutional. The South Dakota statute imposes sales tax collection responsibility if, in the current or prior year, a seller had gross sales revenue in South Dakota in excess of $100,000 or made 200 or more “separate transactions” in South Dakota. South Dakota’s law is purely prospective and makes no effort for force electronic or mail order sellers to collect or pay past sales taxes.

Amazon Tower I, Seattle, Washington by Joe Mabel. CC-BY-SA-4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Amazon Tower I, Seattle, Washington by Joe Mabel. CC-BY-SA-4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.If a state deviates from the South Dakota pattern, it risks a legal challenge to its statute. If, for example, a state uses a lower sales threshold to trigger an out-of-state retailer’s collection responsibilities, or imposes retroactive liability on out-of-state retailers for taxes they failed to collect in the past, the state risks a legal contest. It is thus likely that most states will adopt the South Dakota formula.

Wayfair presents the remote sales industry with an interesting political choice. Until now, the internet and mail order sales lobbies have successfully blocked in Congress legislation which would have overturned Quill and its physical presence test. If the remote sales industries conclude that the South Dakota statute imposes too onerous obligations on out-of-state sellers, the industry can seek federal legislation to make those rules more favorable to internet and mail order sellers.

If so, the proverbial political shoe will be on the other foot. Until now, the internet and mail order sellers resisting sales tax collection responsibilities have had the political advantage of defending the status quo. All they had to do in Washington was stop federal legislation overturning Quill. Our political system, with its many choke points, gives great advantage to the side opposing congressional action.

Now, in the wake of Wayfair, it is the remote sellers who are likely to seek federal legislation to protect their interests by reducing their sales tax collection responsibilities.

The post-Wayfair world will also present legal and political challenges for the states expanding the sales tax collection duties of internet retailers. An important issue for the states will be the aggregation of related firms: As states expand the tax collection responsibilities of remote sellers, those sellers will be tempted to divide themselves into separate entities, each with sales below the threshold triggering the obligation to collect sales taxes. The states will respond with legislation which treats as a single entity firms owned or controlled by the same interests. The Internal Revenue Code contains several statutory formulas which deem for tax purposes nominally separate but commonly controlled firms to be treated as a single entity.

In sum, the import of Wayfair should neither be understated or overstated. Many internet sellers, such as Walmart and Amazon, had collected state sales taxes under Quill because such sellers, besides their electronic sales, have physical presences through their brick-and-mortar stores and warehouses. However, as to the considerable world of internet sellers without such physical presence, Wayfair has leveled the playing field. Purely remote sellers making isolated and inconsistent sales into any particular state will still not be required to collect sales tax. But internet and mail order firms will be required to collect taxes when their respective sales into any state trigger the kind of activity described in the South Dakota statute approved by the Supreme Court. The expansion of the sales tax obligations of these internet sellers will make the states’ sales taxes fairer and more efficient by treating electronic and conventional, brick-and-mortar sales in the same way.

Featured image credit: law books legal court by witwiccan. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post How Wayfair opens the door to taxing internet sales appeared first on OUPblog.

“Our Lives, our Fortunes, and our sacred Honor”

This year, as the United States celebrates 242 years of independence, I cannot help but reflect upon the sort of country that the Second Continental Congress hoped to create and, more importantly, the sort of men they envisioned leading it. The men who declared independence were men of their time, as indeed was the author of the Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson. Thus, Jefferson and his compatriots could not envision women, African-Americans, or Indians, among others, playing a role in the public life of the 13 republics, those “Free and Independent States,” each one a white man’s republic.

Happily, Americans have broadened Jefferson’s original and exclusive vision bounded by sex and race. Despite the groanings of a depraved minority, Americans now welcome, and indeed embrace and celebrate, a more expansive and inclusive view that “all men are created equal.” Jefferson’s “men” are now humankind, and Americans are better for it. The country is better for it. Americans’ embrace of this broader view of “men” in the public space does not, however, suggest that everything in the country’s founding document is contested or has markedly evolved beyond what Jefferson and those other men in Philadelphia accepted as the truths of their age.

In pronouncing the birth of the United States, and by making the promise of the declaration and the United States real, Jefferson drew upon accepted truths, chief among them that character and integrity mattered. The most telling enunciation came when the representatives in the Second Continental Congress signed, “for the support of this Declaration, with a firm reliance on the protection of divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes and our sacred Honor.” The Second Continental Congress had come a long way from the first intercolonial gathering.

Image credit: Portrait of Richard Henry Lee by Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827), National Portrait Gallery. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: Portrait of Richard Henry Lee by Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827), National Portrait Gallery. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.In September 1774, representatives from twelve of the 13 mainland American colonies met in Philadelphia in the First Continental Congress. They had come to organize colonial resistance against what many of them saw as Parliament’s usurpation of British American rights, to remonstrate, and to proclaim their loyalty to George III. Before adjourning in October, the delegates resolved to meet once more in May 1775. When Congress convened the following spring, it faced dramatically different circumstances. Protest had turned to war. By the spring of 1776, delegates spoke openly of declaring independence and in June, Richard Henry Lee of Virginia introduced a resolution, “That these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved.” Congress had cast its die.

Responding to the Lee Resolution, Congress appointed a “Committee of Five” to draft a declaration of American independence. Written by Thomas Jefferson, lightly edited by John Adams and Benjamin Franklin, and revised by the Congress, the delegates adopted the Declaration of Independence on 4 July 1776. Declaring independence was no small matter. By doing so and by signing the document, these men publicly stepped forward into the unknown. They risked all, including their lives, reputations, and fortunes.

The founding generation, like every one before and since, had feet of clay. These men weren’t angels, and they knew it. Yet, when they “mutually pledge[d] to each other our Lives, our Fortunes and our sacred Honor,” they gambled all and aspired to something greater than their own narrow self-interest. The signers’ understanding of classical virtues and their deep desire to be remembered in history helped guide their conduct. In linking their reputations to the founding of the United States, these men publicly demonstrated their disinterestedness, their virtue, their deep and abiding concern with their honor, and their desire for some measure of fame.

Just how deeply the signers had internalized the codes of honor, virtue, or disinterestedness varied. What’s important is that these men understood and accepted the concepts well enough to be led and guided in their conduct. These men were vigilant about their good names and standing. Indeed, honor, virtue, and fame were particularly important in a country that was self-consciously shaking off the trappings of the Mother Country and the Old World, including their hereditary titles and distinctions. Without such frills, the honor and fame gained through virtuous conduct raised and sustained men’s reputations and served as proof of their fitness for public office.

Image credit: Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, and John Adams meet at Jefferson’s lodgings, on the corner of Seventh and High (Market) streets in Philadelphia, to review a draft of the Declaration of Independence by Jean Leon Gerome Ferris, Virginia Historical Society. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, and John Adams meet at Jefferson’s lodgings, on the corner of Seventh and High (Market) streets in Philadelphia, to review a draft of the Declaration of Independence by Jean Leon Gerome Ferris, Virginia Historical Society. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.The signers’ recognition of some men’s propensity for corruption was never far from the surface. Theirs was a predatory age, and they were particularly worried about the influence that foreign powers might wield over the fledgling country. Indeed, in Article 6 of the Articles of Confederation, the first draft of which was presented on 12 July 1776, they forbade “any person holding any office of profit or trust under the United States, or any of them, [to] accept any present, emolument, office or title of any kind whatever from any King, Prince or foreign State; nor shall the United States in Congress assembled, or any of them, grant any title of nobility.”

The founding generation’s fear over corruption continued even with the Constitution, which, like the superseded Articles of Confederation, explicitly decreed in Article 1, Section 9 that “no Person holding any Office of Profit or Trust under them, shall, without the Consent of the Congress, accept of any present, Emolument, Office, or Title, of any kind whatever, from any King, Prince, or foreign State.” The sentiment was clear: honor, virtue, and disinterested behavior counted, but some men needed reminders. The future and repute of the republic depended on vigilance and upon the law.

I suspect that Americans’ propensity for honorable, virtuous, and disinterested behavior is in roughly the same measure that it was in 1776. Character and deportment matter now, as then they did. The question, therefore, is where are the men and women of character in the republic’s life? They needn’t hold political office, but they most assuredly must be within the electorate in order to safeguard the health of the republic and its independence. The signers’ willingness to stake their lives, fortunes, and sacred honor underpinned their commitment to the republic as much as to their selves. Our lives, our fortunes, and our sacred honor are no less important to the United States. Americans deserve and depend as much upon their political leaders’ character now as did their predecessors in 1776.

Featured image credit: John Trumbull’s 1819 painting depicting the five-man drafting committee of the Declaration of Independence presenting their work to the Congress. The painting can be found on the back of the US $2 bill. The original hangs in the US Capitol rotunda by US Capitol. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons .

The post “Our Lives, our Fortunes, and our sacred Honor” appeared first on OUPblog.

From Eugène Rougon to Donald Trump: Émile Zola and politics

Zola modeled the characters, plot, and settings of his novel His Excellency Eugène Rougon (1876) on real people and events, drawing on his own experience as a parliamentary reporter in 1869–71 and secretary in 1870 to the Republican deputy Alexandre Glais-Bizoin. But the novel is not a mere chronicle of politics during the French Second Empire (1852–70). Zola’s representation of politics is itself political. The novel could be described as “satirical realism.” Its satirical thrust lies in its depiction of a culture of political repression and in its concentration on what happens in the corridors of power: the scheming, the rivalries, the play of interests, the lobbying and gossip, the patronage and string-pulling, the bribery and blackmail, and the manipulation of language for political purposes.

The satire is not simply a question of theme, but also of mode. The “realistic” texture of the novel is blended with techniques of hyperbole, distortion, and caricature that project a strongly ironic attitude towards the objects of representation. The two protagonists, Eugène Rougon, a leading politician, and Clorinde Balbi, a mysterious adventuress—he, demiurgic, titanic, engaging in fantasies of omnipotence; she, a huntress, a goddess, a serpent, a sphinx, living “in a world of endless, unfathomable intrigue”—are as much figures of myth as reflections of real historical models, while the minor characters play caricatural roles in the general narrative of greed and ambition. Indeed, it is reasonable to assume that the swaggering bully Théodore Gilquin, Rougon’s associate in his “political work” before Louis Napoleon’s coup d’état of 1851, and his occasional spy and henchman afterwards, was consciously conceived as a drunken version of Ratapoil, a character created by Honoré Daumier (1808–79), the “Michelangelo of caricature” who famously satirized the bourgeoisie, the justice system, and politicians through the emerging medium of lithography. Between March 1850 and December 1851, in the satirical magazine Le Charivari, Daumier published about thirty lithographs illustrating Ratapoil, who was intended to represent the shady agents who worked to help Louis Napoleon rise to power.

It is in the treatment of the relationship between Rougon and his gang of acolytes that the satire assumes a particularly surrealist quality. When Rougon is back in power, as Minister of the Interior, his greatest satisfaction is to bask in the admiration of his entourage:

Photograph of Émile Zola. Credit: “Photo de Émile Zola” by Nadar (1820-1910). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Photograph of Émile Zola. Credit: “Photo de Émile Zola” by Nadar (1820-1910). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.He said he was happy to have them around him, like faithful pets. It was not he alone who was the Minister, they all were, as if they were appendages of himself.

When his position is weakened, and Clorinde engineers his downfall, his “little court” deserts him. He finds himself alone.

He began to think back on his gang, with their sharp teeth taking fresh bites out of him every day . . . They lived on his flesh, deriving all their pleasure and health from it, feasting on it without thought of the future. And now, having sucked him dry, and beginning to hear the very foundations cracking, they were scurrying away, like rats who know when a building is about to collapse after they have gnawed great holes in the walls.

While Rougon, the leader who despises the common herd, embodies the pathology of power, his gang represents a familiar reality of modern politics: the leader’s dependency on his “base.”

A striking feature of the novel, and of its satiric intent, is its repeated focus on the relations between language and politics. Rougon sits at his desk, drafting an important circular. “Jules!” he shouts to his secretary, “give me another word for authority. What a stupid language we have! . . . I keep putting authority on every line.” For Rougon, the idiom of authority is repetitious and reductive. It corresponds, of course, to his distrust of the press except as an instrument of propaganda.

Whereas the Naturalist writer seeks to tell the truth, Rougon prefers to suppress it, or rather, to manipulate language to construct and impose his own “truth.” As a writer, he has problems: “Matters of style had always bothered him. Indeed, he despised style. . .” While uncomfortable with the written word, he is presented as a peerless practitioner, in his speeches and generally, of the rhetoric of political authority. His prowess as an orator is first displayed on the public stage in Chapter 10, when he gives a speech at the ceremony held to inaugurate work on a new railway line from Niort to Angers. The chief government engineer (a man who “prided himself on his irony”) includes in his own speech several little barbs that subtly highlight the self-interest and double-dealing that underlie the scheme (which has indeed been conceived to enrich one of Rougon’s cronies). Rougon responds to the engineer’s insinuations with a rhetorical performance that is majestic in its cant:

Now it was not merely the Deux-Sèvres department that was entering a period of miraculous prosperity, but the whole of France—thanks to the linking of Niort to Angers by a branch railway line. For ten minutes he enumerated the countless benefits that would shower down on the people of France. He even invoked the hand of God.

The challenge for Rougon, as a politician, is to control discourse. As George Orwell wrote in his classic essay ‘Politics and the English Language,’ “political language . . . is designed to make lies sound truthful and murder respectable and to give an appearance of solidity to pure wind.” Orwell wrote those words in 1946, but they are eminently applicable to His Excellency Eugène Rougon, just as they resonate, very strongly, today. The highest levels of government in the US today present us with unprecedented amounts (and degrees) of mendacity (“alternative facts”), often served up in a ludicrously bombastic manner. This led the late Philip Roth to characterize the current President as a person “incapable of expressing or recognizing subtlety or nuance . . . and wielding a vocabulary of seventy-seven words that is better called Jerkish than English.” In the opinion of many, the President’s words, delivered often via Twitter and amplified on Fox News, have radically undermined the very notion of a shared political truth.

Featured image credit: “White House lawn” by Daniel Schwen. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post From Eugène Rougon to Donald Trump: Émile Zola and politics appeared first on OUPblog.

How much do patents matter to innovation?

Patents—rights that governments grant to inventors for new inventions—pervade the modern world. The US alone grants about 300,000 of them annually, mostly for components of, or methods relating to, larger end products. Your smartphone, for example, contains thousands of patented features; but even many seemingly simpler items, such as cosmetics, often contain one or more. It’s no big surprise, then, that as patents have exploded in numbers and importance, they have begun to attract considerable public attention. Anyone reading the news over the past decade would have encountered stories on the patentability (or not) of human genes, business methods, and software; the impact of patents on the price of prescription drugs; the abuses attributed to “patent trolls” who buy up patents and, according to critics, profit from nuisance litigation; and, of course, the “smartphone wars” in which Apple, Samsung, and other players found themselves litigating in, at one point, ten different countries.

Most people are also aware that countries grant patents as a means to an end, namely to encourage investment in the creation, publication, and commercialization of new technologies from which the public ultimately benefits. Because invention is often expensive and uncertain, while copying is cheap, absent the exclusive rights that patents provide fewer inventors would invent, and society correspondingly would be worse off.

Or so the story goes, at any rate; but there’s also a competing story that focuses on social costs. Patents often are referred to as “monopolies,” after all, and sometimes (as in the case of new drugs for which there are no substitutes) the term fits. Monopoly in turn means that prices are higher than they would be under competition. Further, because every new invention necessarily builds on something that came before it, if patents are too plentiful or broad, they risk raising the price of creating new technologies, which in turn makes such creation itself less likely.

So do patents, on balance, generate a surplus of benefits over costs?

Of course, pretty much everything in life involves a tradeoff between costs and benefits; the question is whether any given tradeoff is worthwhile. So do patents, on balance, generate a surplus of benefits over costs? And if so, is that surplus as high as it could be, or should patent laws be reformed to make it greater?

Most economists believe that the answer to the first question is yes—that the world is a better place with patents than without them—but beyond that, consensus is hard to come by. Most observers believe, for example, that patents are crucial to innovation in industries such as pharmaceuticals. But the amounts drug companies actually spend on R&D, for which patents are said to compensate them, remains opaque; and while it’s better to pay a monopoly price than to do without a lifesaving drug, our choices might not be so constrained if we had better information. Similarly, one reason that firms in high-tech industries acquire patents is to have an arsenal in reserve, in case they wind up being sued themselves (the so-called patent arms race)—a practice that, on one view, seems socially wasteful. At the same time, though, venture capitalists often look to startups’ patent portfolios as evidence of hidden value, leaving the net impact of patents in the high-tech space a bit ambiguous.

After all these years, you might think we’d have a better idea of the conditions under which patents promote the public good. The good news is that the picture is, in general, improving, as economists conduct richer empirical studies of how the system works; their insights, though gradual and imperfect, can help nudge policymakers in the right direction. But it’s also important not to overstate one’s case: other research suggests that the policies governments have adopted over the decades with regard to patents may not be as central to the innovation landscape as those of us in the thick of it sometimes like to imagine.

Early in my career, I used to ridicule Chief Justice Burger’s assertion in a famous case that whether certain bacteria were patentable or not “may determine whether research efforts are accelerated by the hope of reward or slowed by want of incentives, but that is all.” If patents had only such a marginal impact on innovation, I wondered, why bother having a patent system in the first place? As the years have passed, however, I’ve come to see that maybe the chief was right—that, as Kevin Kelly writes, the technium evolves according to its own unique path and timetable. Perhaps the best the law can do is move it along a little faster or smoother than it otherwise might go. A rather humble mandate, perhaps; but at a time in which humility often seems to be in short supply, a bit refreshing for all that.

Featured image credit: Light bulb by Free Photos. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post How much do patents matter to innovation? appeared first on OUPblog.

July 1, 2018

The politics and power of nostalgia

The summer exam season is now upon us so let me start this month’s blog with a simple question: ‘What role does nostalgia play in explaining ‘the populist signal’?’ A recent report suggests that the role of nostalgic narratives has become a central element of contemporary politics that tap into (and to some extent fuel) anti-political sentiments amongst the public. Could it be that recent analyses of ‘funnelling frustration’ need to pay equal attention to ‘nurturing nostalgia’?

Nostalgic narratives that look back and promise to rediscover ‘the good old days’ provide one of the most obvious and powerful tools in the toolkits of populist politicians and their insurgent parties. To some extent nostalgic narratives have been used in different ways, different forms, and at different times by parties of the Left and the Right for decades, if not centuries; but in recent years the emergence of nationalist populism in many countries has focused attention on the role of nostalgia as a motivating force. The Brexit referendum provided a powerful example of the politics and power of ‘nurturing nostalgia’ while also ‘funnelling frustration’ in the sense that the ‘Leave’ campaign revolved around, as Alan Finlayson wrote at the time, ‘a mixture of resentment at past losses and scepticism about promised futures.’ The sense of a loss of tradition, a mythical integrity, an eviscerated global status, a romanticised past, plus a nativist and nationalist anxiety were all set against the perceived excesses of a distant European elite. However, a recent report by Demos provides further evidence about the politics and power of nostalgia and comes to a rather worrying conclusion.

The research reveals three countries [Britain, France and Germany] with profoundly different histories, political cultures, and national psychologies, yet also bound together by a common affliction. In these great nations, each with, in historical terms, momentous levels of prosperity, standards of living, and global influence, a substantial minority – or even majority – of citizens are gripped by a kind of malaise, a sense that something is fundamentally rotten at the heart of their societies. Moreover, an omnipresent, menacing feeling of decline; that the very best of their culture and communities has been irreversibly lost, that the nation’s best days have passed, and that the very essence of what it means to be French, or German, or British is under threat. While the political consequences of this psychological state are unique to each country, our research demonstrates that many of their antecedents are shared.

Nostalgia provided a barrier or buffer against further change. It’s not about going back but stopping a process of rapid socio-political change in which large sections of society really do feel left behind.

As J. D. Taylor argues in his wonderful book, Island Story (2016), ‘Politics has never been a matter of reason, but of feeling’ and in this regard it is possible to suggest that populist politicians and their parties have in recent years possessed a far more sensitive emotional antennae than their mainstream counterparts. As Ronald Brownstein has argued in relation to understanding the emergence of Donald Trump – ‘The most important word in Donald Trump’s lexicon may be: ‘again.’ The second most important word is ‘back’ as Trump is forever promising to ‘bring back’ manufacturing jobs, the steel industry, national pride, ‘law and order’, etc. As the Demos report illustrates, although nostalgic narratives are clearly mediated and contextualized by a nation’s socio-cultural history (i.e. they must ‘fit’ or resonate with the public) nostalgia has also become almost as promiscuous as it is prominent.

But what exactly does the Demos research tell us that we may not have known already?

The report is rich with insight but three themes or issues jumped out at me: (1) the progress ‘trade-off’; (2) ‘negative nostalgia’; and (3) ‘nostalgia-as-anchorage’.

Given the online comments that it provoked I don’t know if I dare mention my apparently heretical suggestion from May that there may be a need to somehow close the gap between the views of many political scientists on the state of democracy (i.e. generally negative, critical, pessimistic), on the one hand, and the views of the ‘new optimists’, on the other (i.e. broadly positive and optimistic). But when it comes to understanding this intellectual tension, as it appears very much on the ground in terms of people’s everyday lives, the research is fascinating. Critical citizens are very much aware of the progress that has been made in terms of standards of living, educational standards, etc., but feel that the trade-offs between these gains are not sufficiently off-set by the tangible losses they observe in terms of security, community, and cohesion. The link between ‘the precariat’ and nostalgia is understandable in the sense that the latter offers the former a vision of simpler, more stable times.

A second striking finding of the research was that despite the fact that a lot of respondents hankered after a bygone era, they also felt that ‘nostalgia’ had become a pejorative word, almost a taboo concept or liberal slur. This may reflect a set of assumptions that may – explicitly or implicitly – link nostalgia with a desire for ethnically homogenous, or certainly less diverse, communities. Hence, Brownstein’s emphasis on what he terms Trump’s ‘rhetoric of white nostalgia’. It might also be thought that looking backwards reflects an exhaustion of intellect and the inability to imagine fresh horizons or deal with the challenges of today. Which brings me to the third distinctive insight produced by the Demos data – ‘nostalgia-as-anchorage’.

The third noteworthy finding was that the focus group research in Britain, France and Germany did not suggest that nostalgia mattered because people necessarily wanted to go back to the past. It mattered because nostalgia provided a barrier or buffer against further change. It’s not about going back but stopping a process of rapid socio-political change in which large sections of society really do feel left behind. Nostalgia provides a link to a ‘deep story’, to use Hochschild’s term, which is in itself a powerful form of emotional anchorage.

So what? Why does understanding nostalgia as a contemporary political or cultural force matter? It matters because it suggests a need to cultivate an open and balanced public debate about those issues, such as immigration, poverty and inequality, that have for too long been allowed to fester on the margins of mainstream politics. It also matters because in terms of combatting ‘the perils of populism’ it suggests a need for politicians to reconnect at a deeper emotional level; to demonstrate a little emotional intelligence; and to offer a bold new vision — a renewed ‘deep story’ that unites a positive past with a positive future — by redefining many social challenges as opportunities for confident social change.

Featured image credit: Clock wall watch by Monoar. Publid domain via Pixabay.

The post The politics and power of nostalgia appeared first on OUPblog.

How to write a biography

This year I’ve been reading a lot of biographies and writing some short profile pieces. Both experiences have caused me to reflect back on a book-length biography I wrote a few years ago on the little-known educator Sherwin Cody.

I first learned about Sherwin Cody as an adolescent, when I spotted his “remarkable invention [that] has improved the speech and writing of thousands of people” in the back of a comic book. (It turned out to be a patented workbook of grammar exercises.) Many years later, reading about the history of writing instruction, I became fascinated by Cody’s life and career, so much so that I decided to tell his story. The rest is history, or more accurately, biography.

Writing a book-length biography was a new experience for me at the time. I learned a lot along the way. Here are a few tips based on my experience.

Start small—A good way to begin is by writing a short profile of your subject in no more than 1,000 words. Imagine it as a short encyclopedia piece or obituary of the person that encapsulates the basic story (the who, what, where, when and how) along with discussion of significant accomplishments and challenges. The profile will tell you if you know enough to write more and also help you to clarify your stance toward the subject. If you feel too strongly about your subject you may not be the ideal person to write a biography. There may be a temptation to adulate or unmask.

Figure out the contexts—Spend some time studying the individual’s era. What was the state of the world during the person’s lifetime, and how did major events intersect with your subject’s life. The context can be large-scale, taking in the sweep of history over several generations, or finely grained, covering one life span. But understanding the world as it was will give you a sense of how your subject may have seen it.

If you are writing about someone who has already been the subject of biographical work, you also need to consider the context of what other writers have said. How does your effort add to the story? Do you have new material? Has there been a re-evaluation of the individual? Has society changed in such a way that the person has new relevance? Is there an anniversary on the horizon? (You’ll want to plan way ahead for that last one!)

Develop a research network—As you dig into your work, be on the lookout for new material. Is archival material coming available? Are there family members who have recollections or bits of ephemera? Can you find some librarians or archivists or historical society staffers who share your interest? Some of this research may involve travel and/or copying fees, so keep that cost in mind.

Engage the backstory—Part of the enjoyment of writing a biography is that it allows you to put together a mystery not just out of large events, but out of small puzzle pieces as well. A description of some event during a person’s college years or on a vacation, for example, can illustrate their personality just as well as a large life event does, and it can make the subject relatable to readers who may have had a similar experience. Finding the sweet spot between too much digression and just enough backstory will not come immediately but it is worth the effort.

Be open to refocusing your idea—As you write and learn more about your subject, it may turn out that the story you are writing is not really about just one person. Perhaps it is a story about an ensemble of like-minded people, or a movement, and perhaps the stories of others are just as fascinating and important. Your work could turn out to be about a group working together or in opposition, or about people set in different times or places brought together by common thread. It may not be a biography in the strict sense and that’s fine. You can adjust.

Writing a biography can take an author anywhere. If there is someone whose life fascinates you and that you are in a position to illuminate as a researcher and writer, jump in.

Featured image credit: Epicantus by Daria. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post How to write a biography appeared first on OUPblog.

June 30, 2018

Rediscovering ancient Greek music

“Research into ancient Greek music is pointless”—Giuseppe Verdi

“Nobody has ever made head or tail of ancient Greek music, and nobody ever will. That way madness lies”—Wilfred Perrett

At the root of all Western literature is ancient Greek poetry—Homer’s great epics, the passionate love poems of Sappho, the masterpieces of Greek tragedy and of comic theatre. Almost all of this poetry was or originally involved sung music, often with instrumental accompaniment. Scholars are now in a position to reconstruct from surviving documents how Greek music actually sounded. By combining this knowledge with modern analogies and imaginative musicianship we may make a start at understanding why it was thought to exert such extraordinary power.

Music was as central to Greek life as it is to ours. Greeks believed that music had the power to captivate and enchant. In the fifth century BC, the music of Athenian theatre was enjoyed by tens of thousands of listeners. Top performers were treated like pop stars: the piper Pronomos of Thebes was said, like Elvis himself, to have ‘delighted the audience with his facial expressions and the movements of his body’. The complex rhythms of Greek poetry are usually studied in terms of metre, but were also the basis of dance steps, which involved the rise and fall of dancers’ feet. Marks on stone and papyrus show how the beat fell in some cases of ancient rhythm, and help us to work out how the intricate rhythms may have been danced.

The principal components of Greek music—as of all music—were the voice, instruments, rhythms, and melodies. The instruments are well known from ancient paintings and surviving relics, some in excellent condition. Two main kinds of instrument, the double-pipe (aulos) and the lyre, were used to accompany song. The sweet sound of plucked strings allegedly empowered the minstrel Orpheus to entrance trees and subdue wild animals. Imagine that all we knew of the Beatles songs—or the operas of Mozart, Verdi, Wagner, and Britten—were the words. Then after two millennia, we had the means to rediscover what the music sounded like. We would be bound to recognise the huge difference the sound of music makes to the listeners’ minds and emotions. Imagine!

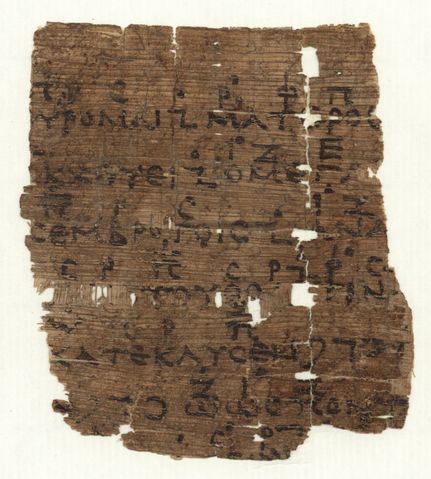

Image credit: The Euripides Orestes papyrus. Papyrus Collection, Austrian National Library. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: The Euripides Orestes papyrus. Papyrus Collection, Austrian National Library. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.We know that music—singing, playing instruments, and dancing—was a significant part of ancient Greek life, from the time of Homer in the 8th century BC for hundreds of years. It was used in religious worship, formal and informal entertainment and banquets, ceremonial occasions such as weddings and victory celebrations, and even in work settings where the aulos (double-pipe) was said to provide a rhythm for workers. Above all, however, we know that the surviving texts of most ancient poetry were sung to music.

Until recently, people thought we knew nothing of ancient tunes, but scholarship has now accurately deciphered marks on stone and papyrus that reveal songs and scraps of tunes, some of which haven’t been heard for 2000 years. The extraction of melody from the markings was allowed thanks to a comprehensive set of tables preserved from around the 5th century AD, by an otherwise unknown author called Alypius. Alypius listed the notations used to indicate vocal and instrumental melody, informing us what modes different marks could refer to and explaining the relative intervals.

A later author, the mathematician and astronomer Ptolemy, who also wrote about music in the 2nd century AD, gives us very precise details of the tuning of the seven- or eight-stringed lyres. He constructed an 8-stringed ‘octachord’ with moveable bridges, and measured the proportions of the strings in order to specify their pitch. As a result, we are able to reconstruct stringed instruments and tune them exactly as they would have been tuned in his time.

Scraps of papyrus with musical notation began to appear as early as the 16th century, and Florentine musicians were excited to try and rediscover the music of ancient Greece. However, they found that the indications were too slight for them to make good sense of the music, and they went their own way in creating opera and oratorio.

Over the past few hundred years, however, more papyri have come to light, as well as stone inscriptions with large amounts of musical notation. From them we are able to reconstruct the sounds of music that would have been sung and played. There are around two dozen melodies that have been transcribed and are able to be performed along with texts which provide the intrinsic rhythm—Greek words consisted of long and short syllables.

These pagan melodies, dating from the 5th century BC to the 3rd century AD, are audibly related to the sung music at the beginnings of the Western musical tradition as we know it, 9th-century Gregorian plainsong. The connection has never before been proven, and it changes musical history. A short film of the music was released in December 2017 and soon became a hit, going viral and reaching over 100,000 views in the first three months.

Now that we can reconstruct some of the sung versions of this poetry in musical form, we are bound to ask the question: how did ancient Greek music affect or interact with the texts of poetry?

Featured image credit: A 17th-century representation of the Greek muses Clio, Thalia and Euterpe playing a transverse flute, presumably the Greek photinx. Painting by Eustache Le Sueur. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons .

The post Rediscovering ancient Greek music appeared first on OUPblog.

June 29, 2018

Birkbeck crowned winners of the OUP and ICCA National Mooting Competition 2018

Congratulations to Daniel Cullen and Santosh Carvalho from Birkbeck, University of London, who displayed exceptional mooting skills to take the victory and be crowned winners of the OUP and ICCA National Mooting Competition at the final held at Inner Temple, London, on 28 June 2018. Congratulations should also go to Lewis Aldous who was part of the Birkbeck duo for the first three rounds.

Lady Justice Hallett, Vice-President of the UK Criminal Division of the Court of Appeal, presided over this year’s final and allowed the finalists to showcase their advocacy skills by testing their legal knowledge with her interventions. She remarked that all the teams were worthy finalists and that it had been an incredibly difficult task choosing a winner. She went on to say that all the students were welcome in her court any day.

Although the competition is now in its 20th year, Birkbeck is the first team to have won the competition under OUP’s new partnership with the Inns of Court College of Advocacy (ICCA). As a reward for their win, Daniel and Santosh receive £750 each as well as a day marshalling His Honour Judge Anthony Leonard QC at the Central Criminal Court of England and Wales (The Old Bailey), where they will have the chance to gain a real insight into how judges consider and manage cases.

The fictitious moot problem used in the final focused on tort law and economic loss, involving an expatriate businessman attempting to pay his gambling debts with a counterfeit cheque. The problem was written for the competition by barrister Rosalind Earis, and enabled all the students to shine as advocates.

Congratulations also go to the other three teams that reached the final – Keane Davison and Victoria Taylor representing Queen’s University Belfast; Georgia Palmer and Steven Moore representing Open University; and Robert Shu and Bharat Punjabi representing University College London. To get to this stage, the teams had to win four rounds of the competition, whilst also undertaking university exams and coursework. We send our thanks to them, and all the participants from this year’s competition for their incredible hard work, and also to the coordinators and academics who have coached them.

Santosh Carvalho and Daniel Cullen accepting their trophies from Lady Justice Hallett.

Image courtesy of Oxford University Press and ICCA.

The post Birkbeck crowned winners of the OUP and ICCA National Mooting Competition 2018 appeared first on OUPblog.

Sports impairment in youth with inflammatory bowel disease

Over 80,000 children and adolescents in the United States live with inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), which includes Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis. These are chronic autoimmune diseases that cause inflammation in the gastrointestinal tract. Crohn’s Disease can cause inflammation anywhere in the digestive tract, while the inflammation in Ulcerative Colitis is localized to the colon and rectum. Specific causes of IBD are unknown, but a combination of genetics, the environment, and the body’s immune response are factors that contribute to the development of IBD. IBD symptoms and disease severity often vary between patients, however, common symptoms include diarrhea, urgency to use the bathroom, abdominal pain, fatigue, fever, and weight loss. These symptoms can make it difficult for patients with IBD to exercise regularly. Among kids and teens with IBD, little is known about the impact of IBD symptoms on physical activity in youth with IBD. A recently published article on sports participation in youth with IBD by Dr. Rachel Greenley and colleagues provides us with key points to consider.

Why might IBD symptoms interfere with sports participation in youth with IBD?

IBD symptoms including urgency to use the bathroom, diarrhea, abdominal pain, and fatigue can all can make it difficult for youth with IBD to be physically active. For youth with IBD, being concerned about exercising near a restroom, what their peers might think if they have to sit out of an activity, or pain related to IBD symptoms may make exercise difficult. In addition, IBD can lead to certain symptoms outside of the digestive tract, like joint pain, which can also make exercise difficult.

Why is physical activity an important topic to study in youth with IBD?

Physical activity is important for all youth as it helps promote better physical and mental health. Healthcare providers recommend that youth with IBD engage in the same amount of physical activity that healthy youth engage in, which is at least 60 minutes of daily exercise. Youth with IBD experience similar benefits of physical activity as healthy youth. Among adults with IBD, physical activity has been shown to help improve disease symptoms. Thus, youth with IBD who participate in regular physical activity may be healthier overall and experience additional benefits such as reduced IBD disease activity and decreased risk of osteoporosis. Additionally, youth with IBD may be at greater risk for developing a mental illness such as major depressive disorder. Thus, it is possible that for kids and teens with IBD, physical activity may also be beneficial in decreasing the risk of major depressive disorder.

Healthcare providers recommend that youth with IBD engage in the same amount of physical activity that healthy youth engage in, which is at least 60 minutes of daily exercise.

What percentage of youth with IBD experience impairment in sports?

Our study included a national sample of 450 youth with IBD between the ages of 12-17 years old. Overall, within the study sample, 66% of kids and teens reported that their IBD caused at least some interference with their ability to participate in sports. Moreover, 18% reported that their IBD caused a major impairment in their participation in sports. No differences in level of impairment in sports participation were seen between youth of different genders, ages, or races/ethnicities.

What disease or physical health characteristics influence participation in sports?

Youth with IBD that reported having a pouch, ostomy, or past IBD-related surgery experienced greater impairment in their ability to participate in sports. Additionally, youth with IBD that reported pain and fatigue were more likely to have impairment in sports participation. Finally, greater IBD disease activity was associated with greater impairment in sports participation. Disease activity, however, was most strongly associated with impairment in sports participation across all of these physical health characteristics.

What is the role of anxiety and depression in influencing participation in sports?

Youth with IBD that reported high levels of anxiety and depression were more likely to also have impairment in sports participation. However, when comparing the role of anxiety and depression to that of the physical health characteristics mentioned above, pain and history of IBD-related surgery were found to be more salient factors in influencing youths’ ability to participate in sports than anxiety or depressive symptoms.

Where do we go from here?

Future research should look at specific barriers to sports participation that youth with IBD experience, which will help identify strategies to enhance participation in sports. Future research should also follow youth over time to better understand if impairment in participating in sports is just a temporary issue or a long-term problem. Finally, future research is needed to understand other domains of physical activity that might be impaired in youth with IBD.

What are the clinical implications?

It may be helpful for healthcare providers working with youth with IBD to regularly evaluate the amount of exercise that is occurring within this group. For kids who are less active, healthcare providers could help youth identify barriers to physical activity. The healthcare provider could also assist in developing a plan for physical activity that is sensitive to the youth’s ongoing IBD symptoms and concerns. Additionally, healthcare providers could consider working with teachers and schools to advocate for accommodations that may make physical activity and sports participation easier for this population.

To learn more about IBD, check out the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation

Featured image credit: Wanna play? by Sabri Tuzcu. Public domain via Unsplash.

The post Sports impairment in youth with inflammatory bowel disease appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers