Oxford University Press's Blog, page 242

July 6, 2018

The varieties of shame

When my grandmother died in 2009, my far-flung family returned to east Texas to mourn her. People she had known from every stage of her life arrived to pay their respects. At a quiet moment during the wake, my aunt asked my grandfather how he felt about seeing all these people who loved him and who loved my grandmother. He answered, “Shame” and started to cry.

Moral philosophers have been thinking about shame and its place in our moral lives for a long time. In the Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle claims that shame is the “fear of disrepute” that keeps us from doing shameful things. Aristotle’s influence on contemporary views of shame is easy to see. 2000 years later, John Rawls defines shame as the loss of self-esteem we experience when we fail to achieve certain excellences. Gabriele Taylor calls shame an “emotion of self-protection”—shame is a sort of emotional warning siren that stops us from losing more face than we already have. This general understanding of shame has become the dominant one in moral philosophy. Shame is thought of as a negative emotional response to a failure to live up to our values or ideals.

Suppose I want to be an honest person, but in a moment of weakness I hide something important from a loved one. I feel shame about my dishonesty. Philosophers will say the reason I feel shame is because I have betrayed my values. This way of understanding shame makes it a nice complement to our other important moral emotions. We feel guilt about doing the wrong thing, we feel indignation when we see injustice, and we feel shame when we fail to be the sorts of people we want to be. Thought of in this way, shame fits comfortably alongside the rest of our moral emotions with a distinct role to play: it helps us make sure we’re living up to our ideals.

So where does this story leave my grandfather? Nowhere, it seems. He felt shame when faced with a room full of people who loved him and who loved my grandmother. What values did he betray? What ideals did he fail to live up to? He didn’t do anything wrong. In fact, he didn’t really do anything at all.

Maybe my grandfather’s shame is just irrational. We want to say that he has no reason to feel shame. It would be perfectly natural to tell him, “No, you should feel loved and supported. You shouldn’t feel bad about yourself.” He must be mistaken about his feelings.

I don’t like this answer. In part, I think it’s patronizing. We’re assuming that because his feelings don’t fit the familiar story we tell ourselves about what shame does, then he’s the one that must be getting it wrong. Especially when it comes to negative emotions like shame, we’re quick to police those feelings when they don’t immediately make sense.

The bigger problem is that, out of all our moral emotions, shame seems to have the most variety. People feel shame about a whole host of things. Philosophers are right that we feel shame about failing to live up to our values, but we also feel shame about being seen naked. We feel shame about being poor, about looking stupid in front others, and about the way our bodies look. Rape survivors, torture victims, and cancer patients all report feelings of shame. Most of these cases don’t fit the story that moral philosophers usually tell about shame, and yet some of them—shame about being seen naked, for instance—are some of the most familiar shame experiences we have.

That experience—the experience of having his sense of self challenged by some other version of him—is the hallmark of shame.

So what should we do? I think we need to tell a new story, and it should be one that can help make sense of my grandfather’s shame and other cases like it. I think shame isn’t about failing to live up to our ideals. Instead, I think we feel shame when something happens to make us feel like we’re no longer ourselves. In other words, shame isn’t about our values; it’s about our identities. My grandfather was humble and unassuming. He preferred to fly below the radar and not draw a lot of attention to himself. When faced with a room full of people expressing love and concern for him, his self-conception got shaken—he hadn’t really flown as far below the radar as he thought. Having all these people in the room who loved him forced him to see himself in a way he didn’t expect or anticipate. Their presence presented him with a different version of himself that was strange and unfamiliar. That experience—the experience of having his sense of self challenged by some other version of him—is the hallmark of shame.

This story of shame doesn’t presuppose that we’ve failed to live up to our ideals, and it doesn’t assume that we have to be judged negatively by others. The result is that it can help us understand shame in all its variety. My grandfather’s shame isn’t irrational even though it doesn’t look the way moral philosophers have traditionally described it. That doesn’t mean my aunt was wrong to try to comfort him. Shame is, after all, a painful feeling. We can comfort people’s painful feelings without telling them those feelings are mistaken.

I think this story can also explain why shame is a morally valuable emotion. It’s common to hear people say that political leaders and public figures are “shameless” or “have no shame.” Obviously these judgments are meant to be critical—so why is it important to have a sense of shame? According to my story, we feel shame when we have our sense of ourselves challenged by some other version of us. Just because I think I’m an upstanding person, it doesn’t make me that way. Having a sense of shame means that we take seriously the thought that we might not always be the people we think we are.

Featured image credit: Caïn venant de tuer son frère Abel by Henri Vidal in Tuileries Garden in Paris, France by Alex E. Proimos. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The varieties of shame appeared first on OUPblog.

Nonsurgical challenges in surgical training

Surgical cases dramatized in popular culture are loosely based on reality, but surgery is decidedly less glamorous on a daily basis. Saving lives from the brink of death is relatively infrequent; more often, it’s navigating barriers to modest attempts at improving quality of life. It’s a marathon that also happens to be a daily sprint.

Before embarking on my own surgery training, I mentally prepared myself for the long hours and expected demands of caring for sick surgical patients, but looking back, the lessons I remember most came from small, quiet, and often unexpected moments.

Why is surgery training so grueling? Aside from the obvious—taking care of the ill is challenging—many of the pressures arise from one of a few buckets:

(1) You don’t want to hurt anybody—but you also don’t want to look incompetent.

For a young doctor, these two are often in direct opposition. My first day as an intern, I was tasked with drawing a patient’s blood. I’d phlebotomized patients as a medical student and thought I was good at it, so I approached the patient confidently, explained what I was doing, and went for the vein.

No blood. I apologized, tried again, and missed again. I felt the anxiety rising inside, thinking, do I call my senior already? I’ve been an intern for two hours; I can’t admit defeat and look so helpless so soon. Do I continue to stab this poor patient (who, thankfully, truly was being patient with me and my failed attempts)?

Solution: humble yourself.

I could have called a senior at that moment, and probably should have. As I stood there struggling to decide, the patient care technician, who was a quiet older woman, approached with a fresh needle. Without a word she took the patient’s arm, swabbed it with an alcohol pad, and deftly hit the vein. The tube filled with blood, and she handed it to me. I was so shocked (and humbled) that I could barely say thank you. She nodded and went back to her work.

Despite being a doctor on paper, there was so much I didn’t know, and that encounter helped me realize that the sooner I started seeing barriers as opportunities to learn how to be a doctor, instead of trying to overcome them just to prove I was one, the sooner I would become a good doctor.

(2) Everything is urgent, and everything is (seemingly) important.

Knowledge of human pathophysiology and basic science seems laughably irrelevant when rounding on 30+ patients with your team, constantly running to catch up, frantically jotting down orders dictated by your seniors, mostly clerical: book this patient for urgent laparotomy. Repeat labs on bed 2. Make sure Mr. Tan gets orange jello instead of red so I don’t have to hear him complain about it. Don’t forget to document the abdominal exam.

Looking back, the lessons I remember most came from small, quiet, and often unexpected moments. Performing surgery is only part of being a surgeon—you’re a doctor first.

Solution: prioritize.

It’s so easy to get overwhelmed. Sometimes you’re criticized no matter what, but in the grand scheme of things, missing the jello order is probably a smaller sin than not getting the sick patient to the OR. Figure out a method to capture your to-dos (write in a notebook, use a smartphone app, scrawl on your scrubs in pen), and prioritize. I would constantly construct and reorganize the Eisenhower matrix in my head throughout the day, mentally placing tasks in different quadrants, asking myself: is this urgent? Is it important?

Image by Rachel J. Kwon. Used with permission.

Image by Rachel J. Kwon. Used with permission.(3) Training is physically and emotionally demanding, and sometimes you lose sight of why you chose it.

Nothing fully prepares you for this, and sometimes it feels like everything is against you. One night, I was called by the ER to see a toddler with a broken feeding tube. It was midnight, and I’d been in the hospital since 6 am, had maybe eaten crackers at some point, and couldn’t remember the last time I’d used the bathroom. Impatient and irritated since there were “real” overnight emergencies, (i.e. cases that would take me to the operating room), I quickly assessed the patient and found that part of the tube needed replacing. I tried temporizing it to allow the child to receive her feeds until the part could be replaced. I couldn’t. I called the operating room to see if they had the same type of tube. They didn’t.

Over the course of the next eight hours on call, between checking in on sick patients and seeing new consults, I tried to figure out a solution. I sneaked into the OR supply room myself to confirm the feeding tube component wasn’t there. I went to central supply, deep in the bowels of the hospital basement. No luck.

Solution: remind yourself.

At some point I realized there was one person whose night was worse than mine: the child’s mother. I’d spoken with her intermittently when giving her updates. She was alone raising a kid who couldn’t eat normally and probably never would. My frustration at trying to fix a broken feeding tube was a fraction of what she endured every day. Yet she appeared completely calm, and her compassion and understanding surpassed mine, when it should have been the other way around. Seeing how she dealt with the situation gracefully in the face of distress reminded me that as physicians, we always have and must offer compassion and empathy to our patients even when we can’t cure their disease or solve their surgical issues.

Performing surgery is only part of being a surgeon—you’re a doctor first, which often means wading through the weeds to take care of your patients.

One day as a senior resident, I was on my way to the OR when I saw the tech who’d helped me that first day. I thought about how much I’d learned in the years since then, and wanted to tell her I was still truly grateful for her help that day. Oddly, I also wanted her to be proud that I was about to scrub a complicated operative case when the last time we’d spoken I didn’t even know how to draw blood. And although she didn’t know it, I couldn’t have gotten to where I was without her, and all the other unexpected teachers I encountered over the course of my residency who taught me invaluable lessons and skills beyond the surgeons who trained me in the operating room.

Featured image credit: Surgery hospital doctor by sasint. Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Nonsurgical challenges in surgical training appeared first on OUPblog.

July 5, 2018

Smoke from wildland fires and public health

Firefighters, forest managements, and residents are preparing for another fire season in the western part of the United States. Wildfires burn large expanses of forested lands in California, but it’s not just rural Californians who need to worry about effects of such fires. Residents in urban areas and neighboring states experience the through smoke from hundreds of miles away.

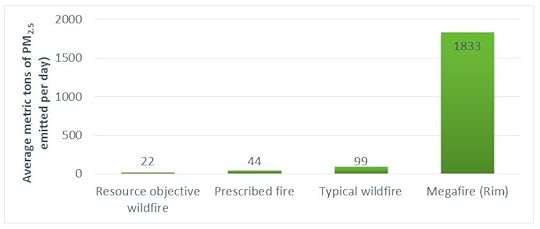

A recent case study analysis in the Journal of Forestry examined how smoke impacts from wildland fires that burn under hazardous conditions compared to fires that are purposefully managed to achieve more beneficial outcomes (described as “resource objective wildfires”). Within California and especially within the Sierra Nevada mountains, forests have evolved to burn frequently, but suppression activities have funneled much of the burning into large wildfires that are a major source of fine particulate matter (Fig. 1) and cause serious health threats to downwind communities.

Figure 1: Fine particulate matter from wildfires, prescribed fires, and other sources in California. Figure prepared by Jonathan Long using data from the USEPA’s triennial National Emissions Inventory. Image used with author permission.

Figure 1: Fine particulate matter from wildfires, prescribed fires, and other sources in California. Figure prepared by Jonathan Long using data from the USEPA’s triennial National Emissions Inventory. Image used with author permission.To learn more about this impact, the scientists compared the number of people likely exposed over time to increases in fine particulate pollution from smoke plumes (measured from satellite imagery) during representative wildland fires that burned in the same vicinity but under favorable or unfavorable conditions. Using fire under favorable weather and fuel conditions can facilitate restoration of large areas of forest while minimizing impacts to people downwind. Under such conditions, fires often spread moderately, emit less pollution per day and produce fewer pollutants per unit area by avoiding the increased consumption of logs and tree crowns that occurs during severe fires. Once a fire is underway under suitable conditions, managers can also accelerate (“push”) fire spread when weather lofts smoke away from communities or slow spread (“pull”) when dispersion is less favorable. Burning under favorable conditions allows for more advance warning of potential smoke impacts and helps members of the public to reduce their exposure.to potential harm. Over time, managers can prioritize prescribed fires, appropriate use of wildfire, and other fuel treatments in places and times to create landscape-scale “anchors” that can constrain both the extent and rate of spread of future wildfires.

Figure 2: Smoke plume from a single day of the Rim Fire, when high density smoke overlay more than 2 million people in California and Nevada. Created by Jonathan Long with smoke plume data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Image used with author permission.

Figure 2: Smoke plume from a single day of the Rim Fire, when high density smoke overlay more than 2 million people in California and Nevada. Created by Jonathan Long with smoke plume data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Image used with author permission.In contrast, millions of people in California and Nevada were exposed to enormous plumes of smoke from the 104,000 hectare Rim Fire in 2013 (Fig. 2). This extremely large wildfire had much higher daily emissions than wildfires that were managed to benefit forests in the same area around Yosemite National Park between 2002 and 2013 (Fig. 3). Even after considering the impact on an acre-by-acre basis, the smoke impacts were much greater during the Rim Fire than the fires managed for such resource objectives. The differences reflect not only greater consumption of forest fuels but also the concentration of that burning into extended periods of elevated emissions that reach large populations residing in metropolitan areas, many of which are already vulnerable to elevated levels of pollution.

Figure 3: Average daily emissions (metric tons of PM2.5/day) by fire type in our analysis of 10 years of wildland fires in the Yosemite National Park area, created by Leland Tarnay using data from the National Park Service. Image used with author permission.

Figure 3: Average daily emissions (metric tons of PM2.5/day) by fire type in our analysis of 10 years of wildland fires in the Yosemite National Park area, created by Leland Tarnay using data from the National Park Service. Image used with author permission.The results were drawn from the Central Sierra Nevada, but the framework for evaluating smoke impacts is applicable to other regions. The framework can be applied to fires that have already happened, as in this study, but researchers are now applying the framework prospectively by using models to predict smoke plumes and pollution levels in downwind communities under alternative fire scenarios. That research will help to evaluate the air quality implications of restoring a more frequent fire regime by managing fires under favorable conditions, rather than shunting burning into large conflagrations under conditions that are difficult to control and often expose downwind populations to heavy, prolonged smoke. By applying fuel reduction treatments and encouraging more frequent fires under appropriate weather and fuel conditions, fires in ecosystems that are prone to burning are likely to spread more moderately, emit less pollution per day, and minimize impacts to people.

Featured image credit: CC0 via Unsplash.

The post Smoke from wildland fires and public health appeared first on OUPblog.

Did Muslims forget about the Crusades?

The crusades are so ubiquitous these days that it is hard to imagine anyone ever forgetting them. People play video games like Assassin’s Creed (starring the Templars) and Crusader Kings II in droves, newsfeeds are filled with images of young men marching around in places like Charlottesville holding shields bearing the old crusader slogan “Deus vult” (God wills it!), and every year books about the crusades are published in their dozens, informing readers about the latest developments in crusader studies. And the news these books deliver from the frontlines of research can come as a bit of shock to our crusades-saturated systems: for the longest time, many historians believe, there was little to no interest in the crusades in the Islamic world. At a time when reminders of the crusades are everywhere, these experts ask us to imagine a world from which memories of Christian holy war had all but vanished.

How could Muslims have forgotten about the wars they fought with medieval Latin Christians for some 200 years? The argument runs something like this: although the initial conquest of Jerusalem in 1099 came as a shock, the crusaders never managed to make themselves much more than a nuisance to the Muslim superpowers of the day—first the Great Seljuk empire and then the Mamluk sultans of Egypt—whose real ambitions (and therefore rivals) lay elsewhere. Once the last crusader stronghold of Acre had fallen in 1291, the crusades could be quickly forgotten, with Ottoman conquests in the Balkans now taking center stage. In any case, it was believed that Muslims had never been all that curious about the non-Muslim world. It was only in the mid-19th century that an Arabic term for the crusades (hurub al-Salibiya, or “Cross Wars”) was coined, while what is sometimes described as the first history of the crusades written in Arabic by a Muslim (Sayyid ʿAli Hariri’s Book of the Splendid Stories of the Cross Wars) appeared in 1899. By then, under the gentle prodding of European imperialism, Muslims were beginning to recall earlier encounters with their neighbors to the west. According to a popular textbook on the crusades that is now widely assigned in US colleges, therefore, “The ‘long memory’ of the crusades in the Muslim world is in fact a constructed memory—one in which the memory is much younger than the event itself.”

Image credit: The Siege of Acre. Painted by Dominique Papety, c.1840. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: The Siege of Acre. Painted by Dominique Papety, c.1840. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.When crusades historians teach undergraduates that modern Muslim memories of crusader violence are essentially false, we need to consider the consequences. There is a message here about Muslim curiosity that comes through loud and clear: pre-modern Muslims were apparently so disengaged with Europe that they could forget about the crusades for centuries at a time. More provocative still is the point made about the legacy of Latin Christian holy war. If Muslims could forget the crusades, they must not have done much long-term harm and consequently cannot be blamed for fueling current conflicts.

Regardless of its implications, if this claim is right, then it’s right. That’s how history as a discipline has to work. The problem is that as things currently stand, the argument that “Muslims forgot about the whole thing anyway” is a thesis in search of evidence. Most crusades historians learn the relevant European languages, but do not work directly with Arabic or Ottoman Turkish sources. As a result, the research that could confirm this collective bout of Muslim amnesia—combing through the hundreds of histories, geographies, biographical dictionaries, travel narratives, inscriptions, and poems that Muslims wrote in the Middle East and North Africa between about 1300 and 1900 for references to the crusades—has yet to be done.

Even the briefest dip into Arabic sources offers up tantalizing clues of a more complex Muslim encounter with crusading. Ibn Khaldun was a North African scholar who recounted in a single sweeping narrative a series of wars between Latin Christians and Muslims that feature centuries of fighting in North Africa and the Near East and end in Muslim victory. No, he did not use the modern term hurub al-Salibiya, but why would he? He lived in the 14th century, not the 21st. Shaykh Muhammad al-ʿAlami lived in 17th-century Jerusalem, a time and place that is supposed to have been ignorant of the crusades. But he recalled enough about them to write a poem describing his son as a second Saladin. These may be isolated examples, or they may speak to broader trends. We should find out one way or the other before we embrace a historical argument that risks stereotyping Muslims as uncurious and prone to nursing baseless grievances.

Featured image credit: Taking of Jerusalem by the Crusaders, 15th July 1099. Painting by Emile Signol, c.1847. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons .

The post Did Muslims forget about the Crusades? appeared first on OUPblog.

The ascent of music and the 63rd Eurovision Song Contest

At a speed few can fathom, nationalism has become the dirtiest word in all of European cultural politics. Embraced by the right and rising populism, nationalism seemingly poses a threat to the very being of Europe. Nationalists proudly proclaim a euroscepticism that places the sovereignty of self over community. Just how and in what forms can the values of a common Europe survive? To answer that question, even cautiously, I turn once again to the Eurovision Song Contest (ESC), hosted this year by Portugal in mid-May. No theme is more central to the ESC than the musical competition between nations. The history of the ESC, established in 1956, has consistently responded to nationalist pressures. Musicians compete in the name of the nation; nation struggles against nation, accompanied by the symbols of national selfness.

To listen to the vast repertory of Eurovision songs from the past 63 years is to bear witness to modern European history itself. In recent years, this intrinsic nationalism has decidedly intensified. The Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014, the growing numbers of refugees, and the rise of right-wing populist movements throughout Europe have all left their impact on Eurovision songs. National entries may explicitly commemorate the past—Armenia’s 2015 “Face the Shadow,” recognizing the hundred years since the Armenian genocide, Ukraine’s juxtaposition of Soviet and Russian repression in Crimea with Jamala’s 2016 winning song, “1944.” Indeed, the history of the ESC is one marked by protest and boycott, politicization and national censorship.

And then there was this year’s ESC in Lisbon, when something changed and it was song itself that won the day. The first sign that the contest, with its theme of “All Aboard,” was embarking on a different route was the quick exit in the first semi-final (May 8) of the Russian entry, Yulia Samoylova, “I Won’t Break.” Samoylova had returned to the ESC after being prevented from singing the year before in Kiev after performing in Russian-annexed Crimea. The second sign that ESC 2018 would be different was a growing consensus that the songs themselves were significantly better than in previous years. It was not entirely clear just why this was so, but an aesthetic that took the music seriously was shared by many entries. Generally, there were fewer gimmicks on the stage. Several of the most memorable songs in Lisbon consciously broke the mold of appealing to the youth culture of European popular music, instead offering intimate portrayals of aging—Ieva Zasimauskaitė’s “When We’re Old,” for Lithuania—or the loss of a family member—Michael Schulte’s “You Let Me Walk Alone,” for Germany, which in fourth place proved one of the most powerful songs.

Traditionally, Eurosongs historicize, consciously drawing upon the past, and though Eurovision self-referentiality did not disappear, it was carried out respectfully, for example, when the Portuguese entry, Cláudia Pascoal and Isaura’s “O Jardim” (The Garden), evoked the winning song from 2017, Salvador Sobral’s “Amar pelos dois” (Love for Both of Us). Power ballads, long a Eurosong staple, were fewer, while hip hop finally came of age. Folk-inflected entries were few, but notable, as in Sanja Ilić and Balkanika’s “Nova deca” (New Kids) for Serbia.

Far more critical for ESC 2018 was a decidedly new Eurovision sound. It was this sound that the winning song, “Toy,” performed by Israel’s Netta Barzilai, marvelously captured.

Composed by the team, Doron Medalie and Stav Beger, “Toy” wove together the many threads of a diverse ESC history, creating a sound that was new and exciting for the Eurovision stage. The use of vocables—melodic sounds with no lexical meaning—has long been standard in Eurosongs. When Netta sang vocables in “Toy,” she thus made a gesture toward the past. She also made a deliberate connection to a style that heretofore had little presence in the ESC, electronic dance music (EDM). Over the 45 years of its participation in the ESC Israel had benefited from nationalist politics, but found itself sometimes vilified by other competing nations. Israel’s ESC fortunes declined dramatically after Dana International won in 1998. I was hardly alone in believing that global politics would prevent Israel from winning the ESC. Netta herself claimed that the song made the case for diversity, though in the end it was musical diversity that “Toy” best exemplified:

Netta Barzilai, “Toy” (opening strophe)

Look at me, I’m a beautiful creature.

I don’t care about your wooden time preachers.

Welcome boys, too much noise, I will teach you.

Pam pam pa hoo, turram pam pa hoo.

It is also important that the political present and nationalism also provided contexts for some of the finest songs in Lisbon, among them my personal favorite, the French entry, “Mercy,” performed by the female-male duo, Madame Monsieur.

In the chanson style that has distinguished French songs throughout Eurovision history “Mercy” not only contained a political narrative about the European refugee crisis, but it also mapped that narrative on Europe with the official video, which contains images of arriving refugees:

Madame Monsieur, “Mercy” (opening strophe)

Je suis née ce matin, I was born this morning,

Je m’appelle Mercy, My name is Mercy,

Au milieu de la mer In the middle of the sea

Entre deux pays, Mercy. Between two lands, Mercy.

At the end of the evening, “Mercy” placed only 13th, its European message politely acknowledged, but not compelling. Throughout the Grand Finale the questions of music and nationalism rose again and again, belying simple explanations and leading many to wonder whether we might be witnessing a different response to the new nationalisms, even those synonymous with rising populism in Europe. If only briefly, the 2018 Eurovision Song Contest in Lisbon offered us a moment, in which we could experience the ascent of music in the age of nationalism that we have come to know all too well.

Featured image credit: Lea Sirk (Slovenia 2018) by Wouter van Vliet, EuroVisionary is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License .

The post The ascent of music and the 63rd Eurovision Song Contest appeared first on OUPblog.

July 4, 2018

Monthly gleanings for June 2018

The post on pilgarlic appeared on 13 June 2018. I knew nothing of the story mentioned in the comment by Stephen Goranson, but he always manages to discover the sources of which I am unaware. The existence of Pilgarlic River adds, as serious people might say, a new dimension to the whole business of pilgarlic. Who named the river? Is the hydronym fictitious? If so, what was the impulse behind the coinage? If genuine, how old is it, and why so called? What happened in 1883 that aroused people’s interest in that seemingly useless word?

On the same day, an old friend sent me a link to the website that listed synonyms for “masturbate.” I am well aware of the extensive vocabulary of sex, for I have written the etymology of the F-word and of a few other words belonging to the same “semantic field,” but I could not imagine that people had invented over a hundred phrases for the universal but uninspiring activity, euphemistically called self-abuse. Few of those phrases struck me as ingenious, and even fewer are funny. But I could not help noticing at least five among them that seem to support my derivation of pull ~ pill garlic: pull the carrot, cuff the carrot, slay the carrot, stroke the carrot, and buff the banana. Sure enough, pull is not the same as pill ~ peel, while carrot and banana fit the situation better than garlic. But Chaucer’s phrase seems to have been associated with the image of a bald head, to which the glans is often likened. Also, unprotected sex (“barebacking” in the gentle parlance of modern speakers) is sometimes called going at it bald-headed. And yes, I do think that Chaucer’s phrase was “incredibly obscene.” What would you say about something like “and he spent the whole night j**king off”? Pretty gross, I believe. You may be an admirer of Bakhtin’s carnival theory or have reservations about it, but the fact remains that Chaucer’s, Rabelais’s, and Shakespeare’s obscenities were exactly that.

In the blues. A picture from Picasso’ so-called blue period. Image credit: The Old Guitarist via The Art Institute of Chicago. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

In the blues. A picture from Picasso’ so-called blue period. Image credit: The Old Guitarist via The Art Institute of Chicago. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.And here is one more note on a related theme. (I hope my comments have not hurt anyone’s sensitivities.) In my rather large databank of idioms, I have a letter from Notes and Queries (1896, Series 8/IX: 187) in which the correspondent wondered what the odd phrase he had heard could mean: “It stands stiff, and but’s a mountain.” I am sure it is butts, not but’s, with the whole being not an idiom but a jocular description of sex. Most probably, quite a few people guessed correctly and felt amused by the writer’s innocence. That may be the reason for the lack of responses. On the other hand, the editor did not see the light, for otherwise he would not have printed the query.

Another look at “mad hatter”

“Mad as a hatter” was posted on 24 January 2018. I argued that “madness” could not be hatters’ occupational disease. Later, I remembered the expression blue devils “deep melancholy” and decided to say a few words about it. Not much is known about the origin of that phrase (blue devils are, apparently, the devils that cause depression), but E. Cobham Brewer, for years the main authority on the origin of idioms, discussed it in his Dictionary of Phrase and Fable and wrote: “Indigo dyers are especially subject to melancholy; and those who dye scarlet are choleric. Paracelsus also asserts that blue is injurious to the health and spirits.” The reference to indigo dyers should I think be dismissed, even though some imaginary or real tie between melancholy and the color blue exists: we feel “blue,” when we are sad (hence the blues, though forget-me-nots don’t make anyone sink into a depression). The same should be said about the idiom to be in a brown study, that is, absorbed in one’s thoughts and, at least formerly, troubled by such thoughts (see the post for 22 October 2014). The important thing is to disregard spurious links to professions.

I have received two letters about the most recent post on emotions. Today I’ll answer both and perhaps stop. If I find enough to add to my “gleanings” in June, I’ll write a sequel next week.

In a brown study. Image credit: Pensive Female Woman Window Staring Person by skeeze. CC0 via Pixabay.

In a brown study. Image credit: Pensive Female Woman Window Staring Person by skeeze. CC0 via Pixabay.A small heart and courage

(See the previous post, June 27, on fear).

The first question runs as follows: “I was amused by the notion that a small heart is a sign of valor because it has little capacity for bleeding. Was this idea popular in the Middle Ages?” I know it only from The Saga of the Sworn Brothers. The great Icelandic writer Halldór Laxness, in his ironic and passionate novel on the themes of that saga (in the original it is called Gerpla, and in English Wayward People, but the title means approximately “mock heroics”), did not miss that detail. Other than that, all I can remember is the scene from The Lay of Atli, one of the songs included in The Poetic Edda. The hero Gunnar sees the heart cut from a slave’s breast and recognizes it for what it is, because it trembles, while his intrepid brother Högni’s heart, also presented to him, does not tremble at all. (This episode is also recounted in Chapter 37 of the Saga of the Völsungs.) Nothing is said about the size of those hearts, and I don’t know the origin of the belief celebrated in that heroic poem.

The second letter came from a correspondent who noticed my phrase between the Devil and the blue sea and asked where it came from. To me it came from the same source as blue devils, namely, my database of English idioms, and I sent the correspondent my references. But perhaps someone else will be interested in what I sent her. Here are two ideas on the origin of the phrase, as given in my sources. “The expression is made use of by Colonel Munroe in his Expedition with Mackay’s Regiment (London, 1637). In the engagement between the forces of Gustav Adolphus and the Austrians, the Swedish gunners, for a time, had not given their pieces proper elevation, and their shots came down among Lord Reay’s men, who were in the service of the King of Sweden. Munroe did not like this sort of play, which kept him and his men, as he expressed it, between the devil and the deep sea.” The other explanation known to me smacks of folk etymology: “It has been suggested that the phrase was adopted, if not originated, by the Royalists in allusion to Cromwell, ‘the deep C’, the relationship of the devil to deep ‘C’.”

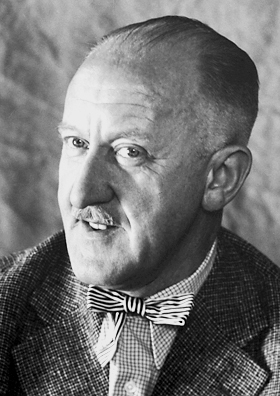

Halldór Laxness, the only Icelandic Nobel Prize winner, the author of numerous novels. Most of them have been translated into English and other languages. Image credit: Halldór Laxness via the Nobel Foundation. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Halldór Laxness, the only Icelandic Nobel Prize winner, the author of numerous novels. Most of them have been translated into English and other languages. Image credit: Halldór Laxness via the Nobel Foundation. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.The Way We Speak

This is from The New York Times: “…only a handful of judges from that era remain on the bench.” Is handful a collective noun? I wonder whether we are dealing here with the ineradicable American agreement of the type the mood of the tales were gloomy (this is a sentence from an undergraduate paper I always use as my parade example) or with the predominantly British use of the plural with collective nouns, as in the royal couple were seldom seen together, the team were in several towns, the Government are engaged in disputes and wars, and the like. This usage is very rare in American English (except for such noncontroversial cases as police and cattle and occasionally public). Since handful hardly qualifies for a collective noun, our mood should probably remain gloomy.

Featured Image: Between the Devil and the blue sea. Image credit: General view of Pearl Harbor during the Japanese attack on 7 December 1941 via the U.S. Navy. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Monthly gleanings for June 2018 appeared first on OUPblog.

The Ancient Celts: six things I learned from Barry Cunliffe

Confession: I’m not an archaeologist nor a historian—at least not in any meaningful sense, though I do delight in aspects of both. But I was lucky enough to see Barry Cunliffe speak about the Ancient Celts at the Oxford Literature Festival earlier this year and then to have front row seats to the recording of this podcast, and I wanted to share a little of what I’ve learned.

1) What is Celtic?

As JRR Tolkien quipped “Celtic is a magic bag, into which anything may be put, and out of which almost anything may come . . . Anything is possible in the fabulous Celtic twilight, which is not so much a twilight of the gods as of the reason.” The generalized concept of (Ancient) Celt is a tricky one, for starters the Celts likely didn’t recognise themselves as one people or nation, but instead were tribal and would form alliances and/or fight with other tribes. (The modern use of the term “Celt” suffers a similar ambiguity).

There are, however, some things they had in common, notably language and art. We’ll come to language next, but Celtic art, or art of the La Tène style, is similar all the way from Bulgaria to Ireland and is typified by swirly repeating patterns as you can see in the Wandsworth Shield below.

Image credit: The Wandsworth Shield, Iron Age shield boss in La Tène style, British Museum, Room 50. Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: The Wandsworth Shield, Iron Age shield boss in La Tène style, British Museum, Room 50. Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported via Wikimedia Commons.2) Now you’re speaking my language

The earliest undisputed record of Celtic language is found in an inscription from the sixth century BC, though it must have been spoken long before this. It is also likely that the Celtic language emerged as a Lingua Franca across the Atlantic Zone (Britain, Ireland, Spain, etc.) to facilitate social engagement, trade, and the spread of ideas and culture.

There are several Celtic languages that survive today: Welsh, Breton, and Irish and Scottish Gaelic are all descendants of Celtic and retain some mutual intelligibility.

Here’s a recording of a native Breton speaker speaking English—does it sound more like a French or Welsh accent to you?

3) It seemed like a good idea at the time…

Many of us might have agreed to things we might not normally do while under the influence: “skydiving sounds like a great idea”; “sure, I’ll sign up for that marathon”; and so it was for the Celts. During evening festivities, warriors would boast of their prowess and organize raiding parties. The next morning while sober, or potentially while still drinking, those who had committed to the raid would see it through. If successful the raid leader would gain status in the tribe by sharing the spoils with their followers and seek to gain new ones.

Wait, status measured by number of followers? It’s comforting to know that in 2,500 years some things haven’t changed…

4) There can only be one…

The feast was a crucial part of Celtic culture, not only a chance to eat, drink, and be merry but also to redefine or re-establish the social hierarchy. After the beast from the day’s hunt had been cooked and carved, meat from the thigh would be served to the chief charioteer. This piece was known as the “hero’s portion.” If another warrior or charioteer, aspiring to greatness, thought that they were more deserving they could issue a challenge and fight it out for the meat. This didn’t always end very well for one or the other with death being a possible outcome. Similar scenes have been noted at Sunday lunch for the last Yorkshire pudding.

5) The enemy of my enemy… nope, still my enemy.

A traditional Irish story from the early centuries AD tells of a chief surrounded by rivals and enemies, so with a cunning plan, he invited them to a great feast. During the feast he told each one of them in secret that they were his most-honoured guest. Over the course of the night, the rivals let slip to each other that they were his favourite, which inevitably caused disputes, which then escalated to violence.

The story goes that the host’s rivals killed each other leaving him the victor; “when the sun rose the next morning the blood was still flowing over the threshold.” Think I’d prefer dinner at the Freys’.

6) “Noble savages”

The Romans had an interesting but difficult relationship with the Celts, there is evidence that they traded with each other but they were also often at arms. While the Romans regarded the Celts as barbarians, they also held them in some esteem. Roman writing about the Celts calls them “noble savages,” this is in part to big up the Romans’ perception of themselves and their empire. By regarding their enemy as courageous and honourable (though perhaps in relative terms) their victories against the Celts were even more commendable and any losses more explainable.

Julius Caesar speaking of the Druids, the “educated class” of Celts, said that to learn their ways would take 20 years. This is in part due to the fact that the oral traditions of the Celts, and their lack of script—though they occasionally made use of other languages’ scripts—made wide dissemination of their knowledge difficult.

Featured image credit: Stone by Hans. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post The Ancient Celts: six things I learned from Barry Cunliffe appeared first on OUPblog.

Angling for less harmful algal blooms

Blooms bring to mind the emerging beauty of spring—flowers blossoming and trees regaining their splendor. Harmful algal blooms (HABs), however, bring to mind a toxic blue-green body of water and possibly a creature from the deep. These blooms, unlike spring flowers, are odorous, unpleasant, and potentially toxic. They can turn a fresh fish sandwich into a trip to the emergency room. They deter families from engaging in water-related recreational activities such as going to the shore. They discourage anglers from going fishing, which, in turn, affects those who depend on the local fishing economy.

The amount of harmful algae has rapidly increased in recent decades and it has adversely affected ecosystems from the Great Salt Lake, to the Great Lakes, to Great River, NY, and beyond. Runoff from crop and livestock production has increased the amount of nitrogen and phosphorous in water, which has led to eutrophication—where plants grow, but fish die due to lack of oxygen. This process has had various negative impacts across space and time. In Lake Erie, a significant and ever-growing hypoxic zone (an area with low or no dissolved oxygen) has grown. This jeopardizes the local fishing industry and the livelihoods of those who depend on it. Mitigating the risks uses a lot of resources. The Ohio Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) estimates that it costs approximately $3 billion per year to deal with algal toxins in Ohio’s public water systems. In addition, these toxic bacteria pose public health risks to humans and animals—in 2010 alone, there were 9 probable or suspect illness cases from Lake Erie water.

Dubbed the “Walleye Capital of the World,” Lake Erie supports a $1.5 billion sport fishing industry for over two million anglers searching for world-class walleye. Economic researchers have long relied on surveys of recreational users to determine willingness to pay for cleaner water and less harmful algae. We surveyed 767 Ohio recreational anglers about how their choices of Lake Erie fishing sites would change in response to changes in water quality attributes. We asked anglers to choose their favorite hypothetical fishing site, characterized not only by conventional water quality attributes, such as walleye catch rates and water clarity, but also a new measure of HAB intensity—miles of HABs the anglers have to boat through before reaching their preferred fishing destination.

Fishing East Sooke Park by Alan Bishop. Public domain via Unsplash.

Fishing East Sooke Park by Alan Bishop. Public domain via Unsplash.What are the economic impacts of HABs on US recreational anglers in Lake Erie? Findings demonstrate that anglers are willing to pay $8 to $10 more per trip for one less mile of boating through HABs en route to a fishing site. In addition, we find that anglers are willing to pay, on average, $40 to $60 per trip for a policy that cuts upstream phosphorus loadings by 40%. The majority of benefits for anglers result from improving the fishing experience, notably water clarity and HAB reduction, as opposed to better chances of angler success. This, in part, is due to the fact the fish will circle around the edges of the hypoxic zone so catch rates actually may not decline in lakes with more algae.

This research makes several contributions to understanding the valuation of ecosystem services. First, it demonstrates that HABs lower recreational anglers’ personal well-being. Second, it estimates the recreational anglers’ willingness to pay for HAB reduction above and beyond conventional water quality measures. This suggests that only using traditional water quality measures, such as water clarity or catch rates, could lead to an underestimate of benefits to the anglers and the industry. Third, the economic improvements of nutrient reductions are mainly manifested through the non-catchable component of the fishing experience (rather than changes in walleye catch rates).

HABs have severely compromised recreation opportunities, public health, and safe drinking water. Unfortunately it is not just in large lakes like Lake Erie, it is increasingly present in local lakes and streams as well. Families now must pay attention to HABs and watch for beach or lake advisories, especially during the summer and early fall. Luckily, NOAA now has weekly HAB forecast program for Lake Erie, Gulf of Maine, as well as the Pacific Northwest. Check these forecasts before planning your fishing or boating trips, and monitor for the red diamond “Elevated Recreational Public Health Advisory” signs, or review a check-list for what to do if you have a pet that has been in contact with HAB materials.

Featured image credit: board boardwalk bridge by Jonathan Petersson. Public domain via Pexels.

The post Angling for less harmful algal blooms appeared first on OUPblog.

July 3, 2018

The greatest witch-hunt of all time

Imagine that a man comes to the highest office in the land with absolutely no political experience. As a young man, he had arrived in the big city to make his fortune and became one of the richest and most famous men in America by making big deals and taking great risks. Some schemes worked out and others did not. Not long before reaching his lofty office, he undergoes a political and spiritual conversion that makes many suspicious and leads them to question his dedication to the cause.

When he assumes office, the trouble begins. He is an unconventional communicator, known for his coarse language and short temper. He does not play by the rules, and his legal problems—including charges of corruption and conflict of interest—soon surface. Even worse, he shows irrational support for America’s mortal enemies. His actions make people nervous, and amid the most destructive weather in memory, cries of “witch-hunt” come to the fore.

Such were the circumstances for Sir William Phips (1651-1695), governor of Massachusetts during the Salem witch-hunt. After several failures, Phips became wealthy and famous by salvaging a wrecked Spanish treasure galleon in the Caribbean. The first American to be knighted by the king of England, he remained a rough-and-tumble sailor, who only joined Increase Mather’s church when he began to seek high office. With Mather’s assistance, Phips became governor, arriving in Boston from England in May 1692, with the witch-hunt well under way and the colony losing a war with the French and their Native American allies.

Portrait of William Phips, governor of Massachusetts, 1692 to 1694 by the US National Archives and Records Administration. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Portrait of William Phips, governor of Massachusetts, 1692 to 1694 by the US National Archives and Records Administration. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Two years earlier Phips had led a naval expedition that captured Port Royal in Acadia, and administered an oath of loyalty to the French residents. So, when Acadian merchants visited Boston, Governor Phips welcomed them, while others wanted them locked up (we now know they were spies, planning an invasion of Boston). As if the war was not bad enough, Massachusetts was suffering from the worst weather of the Little Ice Age. It led to crop failure, starvation, and inflation.

We now understand that witch-hunts usually occur during bad weather in lands suffering from weak, uncertain government. When people are experiencing hard times and feel threatened—often from climate issues and warfare—they look to their government for help. Lacking reassurance, they seek scapegoats, and witch-hunts begin.

As an expert on the Salem witch trials, I am not surprised by cries of “witch-hunt” these days. I am struck by the many parallels between 1692 and today, and believe Phips’s fate may provide insights into how the current American political drama might play out.

Sir William would end the trials only after his wife was accused of witchcraft. By this time it was too late, for 25 innocents were dead and over one hundred more had suffered in wretched jails. The silver lining was the acquittal of witch-hunt critic Thomas Maule on charges of seditious libel—a landmark precedent for First Amendment rights. America’s instinctive distrust in government may also have its roots in the government’s massive failure to protect innocent lives during the witch-hunt. Incumbents rarely lost races in the Massachusetts legislature but over half of the members of the House of Deputies and over a third of the members of the Governor’s Council lost their seats in the elections held in the wake of the witch trials.

Phips’s enemies grew in number and power in the increasingly factionalized legislature. A barely literate ship’s captain who demanded the unquestioned obedience of his crew, Phips lacked the temperament or skills needed to navigate the stormy seas of Massachusetts politics. His adversaries soon began alleging high crimes against the governor, stemming from his involvement in illegal and self-serving commercial activities. The crown recalled him in 1694, but he died in London of a heavy cold before he could defend himself against the charges. Ill-suited for politics and obsessed with advancement and enrichment, Sir William’s life is a cautionary tale for our turbulent time.

Featured image credit: Witchcraft at Salem Village by William A. Crafts. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The greatest witch-hunt of all time appeared first on OUPblog.

Beyond nostalgia: understanding socialism markets

From Che Guevara t-shirts and Honnecker’s Hostel to Mao mugs and Good Bye, Lenin!—why do millions of consumers in China, Germany, Hungary, Poland, and other former socialist societies still insist on the superiority of socialist products and brands? The standard explanation offered by consumer sociologists and historians is that these thriving socialism markets stimulate political opposition, a yearning for the “better” socialist past. From this perspective, when consumers interact creatively and playfully with the socialist past and use highly emotional consumption dramas to revitalize themselves through socialist products and brands, they actively critique, resist, and in the process, invariably destabilize the capitalist present.

Although this explanation is valuable, it has surprisingly little to say about why socialism today is predominantly transported as a market-based consumption experience and what alternative modes for expressing the relationship between the socialist past and the capitalist presence are muted over time and why. What kind of socialisms are transported in these commercial images and meanings and what is their impact on the conditions of capitalism?

To explore this question in greater detail, we analyzed the German Ostalgie market, one of the largest socialism markets in the world. The Ostalgie market emerged after German reunification in 1991. When the Wall came down and consumers were finally able to buy long desired Western goods, socialist products and brands quickly disappeared from the East German supermarket shelves. Soon after the reunification of East and West Germany, however, these once rejected consumer goods re-appeared and are still thriving today.

Most consumer sociologists have taken this remarkable renaissance of East German products and brands as incontrovertible evidence for East Germans’ discontent with social and economic conditions in post-reunified Germany. Gathering the family around a simple socialist meal, rejecting West German food and lifestyle brands, or vacationing in one of the no-frills GDR-themed retro hotels are seen as powerful practices of resistance against West German preferences for efficiency, hyper-individualism, and status consumption.

In sharp contrast, however, we observed that the Ostalgie market’s romantic venerations of socialism changed considerably over time, that they were crafted in West German marketing departments, advertising agencies and film studios who retailored political dissent into consumable emotional-nostalgic market resources to restore political unity in four phases, each triggered by a historical disruption: the privatization of East German industry (1991-2000), the dismantling of German social security (1999-2005), the publication of Stasi informants (2003-2009), and the Euro and global financial crisis (from 2008).

In each of these phases, a nostalgic image of the socialist past was crafted from East German political critiques of capitalism and offered for mass-market consumption.

In each of these phases, a nostalgic image of the socialist past was crafted from East German political critiques of capitalism and offered for mass-market consumption. For example, consider how the 2003 iconic Ostalgie movie Good Bye, Lenin! transformed East German critiques of West German individualism into a banalized contrast between capitalism’s shallow consumer culture and socialism’s caring neighbourhood idyll. Importantly, this highly therapeutic narrative didn’t naturally emerge from the memories of former GDR citizens. Rather, it was carefully crafted and popularized by a team of West German script writers, producers, and promoters—at a time when West German politicians, journalists, and intellectuals seeking to critically unpack the activities of the famous “Stasi” (Ministry for State Security) condemned the GDR as a ruthless surveillance state. This re-imagination of East Germany then could be channeled through consumption by revalorizing socialist brands like Spreewald pickles or the East German care parcel as tokens of a communal utopia as nostalgia-framed identity salves that allow consumers to regain pride as former East German citizens.

With socialism being a multi-billion-dollar business today, sociologists and historians need to adjust their theories on the political significance of socialism markets. The ability of socialist goods to help consumers challenge capitalism’s social and economic conditions must be questioned. While, on the surface level, socialism markets may look like attractive avenues for consumers to take an active stance against status consumption, hyper-individualism and competition, they are ultimately strategies for capitalist societies to transform political dissent into highly emotional consumption adventures, thereby depoliticizing critique and nurturing consensus for the capitalist market system. Re-invoking innocent, emotional, and apolitical tales about the good life in socialism, these brands have a vital function for securing social order in turbulent times by giving citizens a sense of pride, control, and identity as consumers.

Featured image credit: Dresden by maxmann. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Beyond nostalgia: understanding socialism markets appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers