Oxford University Press's Blog, page 240

July 20, 2018

New narrative nonfiction [podcast]

After the 2008 recession, print book sales took a hit, but now BookScan has recorded consistent growth in print book sales year over year for the past five years. What has been driving these sales? Surprisingly, adult nonfiction sales. Covering topics from history, politics and law, nonfiction saw a growth of 13 percent during the last fiscal year.

On this episode of The Oxford Comment we take a look at what has narrative nonfiction turning the industry on its head. Host Erin Katie Meehan sat down with bookstore owner Angela Maria Spring and a selection of esteemed Oxford authors to discuss the emerging trends of diversity and education in publishing.

Featured image credit: “books-literature-library-bookstore-2211342” by PublicCo. CC0 via

Pixabay.

The post New narrative nonfiction [podcast] appeared first on OUPblog.

July 19, 2018

Librarians on bikes: cycling through US libraries

After working for 26 years as academic librarians, we have reached a point in our careers where we are right-sizing professionally and personally. This year, we requested and were granted a nine-month contract, enabling us to pursue our dream of cycling across the United States, from Washington, D.C., to Astoria, Oregon. Along the way, we are visiting public libraries, taking photos, and making notes about library services and programming, and in particular, services available to bicycle tourists and other non-resident patrons. Although our careers have been in academic libraries, we are big supporters of public libraries: one of the few welcoming and safe spaces that offer services to the public at no cost. Serving as advocates for public libraries, we are writing about our library visits, sharing photos, and tracking our progress cross-country.

As bicycle tourists, libraries provide a refuge and a personal connection. Crossing Kansas and Eastern Colorado, with 102-degree afternoon heat, libraries allowed us to get out of the high temperatures, spend time working on the computers, or log in to the library WiFi to conserve our cellular data. In talking with the librarians throughout our trip, we created a personal connection with the towns, learning so much more about the local history, the people that live there, and services and programs provided by the library.

Currently, our route follows the Adventure Cycling Association’s (ACA) TransAmerica Bicycle Trail, a route that originated in 1976 as the Bikecentennial Route. On their maps, ACA lists amenities (camping, hospitals, grocery stores, etc.) for towns situated along the 4,240-mile route. Around 2001, cyclists traveling on the route requested that ACA include sites providing internet access. ACA recognized potential problems with listing internet cafes due to their transient nature and decided the logical place for connectivity was public libraries. Since that time, ACA has included more than 1,500 public libraries on their maps.

Image credit: “Hartsel Community Library in Hartsel, Colorado” by Beth Cramer and John Boyd. Used with permission.

Image credit: “Hartsel Community Library in Hartsel, Colorado” by Beth Cramer and John Boyd. Used with permission.As of late June, we have visited over 20 public libraries, and bicycled 2,300 miles. Our approach is to introduce ourselves to library staff and ask them questions about library services for bicycle tourists such as ourselves and other non-residents that may stop at the library. We still are uncertain if they are more surprised (excited too!) that we are bicycling across the country or that we are both librarians.

Many of the libraries along our route provided services to bicycle tourists passing through their towns. The Kiowa County Public Library in Eads, Colorado is situated on the TransAmerica Bicycle Trail and created a visitor guide specifically for TransAmerica cyclists with useful information such as where to eat, shower, and camp, where to find ice cream, the grocery stores, and the swimming pool. The Council Grove Library in Council Grove, Kansas has created a Local Information space, a corner of the library that highlights the history, attractions, and businesses of the area. They serve as a second Visitors Center for the community, particularly since the library is open more hours.

We were also impressed by the ease of access to computers and WiFi for non-residents. At least four of the libraries we visited allowed anyone, regardless of residence, to obtain a library card with full borrowing privileges. All that is necessary is a government-issued ID and a piece of mail with your address.

In addition to the ease of access to library materials, all of the libraries that we visited had engaging summer programming, welcoming spaces, and personable staff.

In Hartsel, Colorado, a town of only 60 people, the community created the Hartsel Public Library in 1999. Books were donated and the library is staffed entirely by volunteers. The library is housed in a historic building built in 1899 surrounded by a picket fence, and recently received a grant to renovate the interior, creating a cozy and friendly space for community members and visitors.

Brownstown Branch Library in Brownstown, Illinois (population 750) houses its library in an old bank, using the vault as a children’s reading area. The library employs two part-time staff members. They each hold two jobs: one is a librarian/firefighter and the other is librarian/Mayor of Brownstown.

Image credit: “Brownstown Branch Library, Brownstown, Illinois” by Beth Cramer and John Boyd. Used with permission.

Image credit: “Brownstown Branch Library, Brownstown, Illinois” by Beth Cramer and John Boyd. Used with permission.In 2018, the Robert Hoag Rawlings Public Library in Pueblo, Colorado, received both the National Medal for Museum and Library Service (IMLS) and the Leslie B. Knope Award (community favorite/social media award). In winning the Knope Award, Pueblo beat out Beth’s hometown library, Lawrence Public Library in Lawrence, Kansas, during the final four voting. Having visited both of these libraries this summer, we were blown away by the library buildings and outdoor spaces; their creative and plentiful programming, and the obvious love and support they received from their communities. Both of these libraries are outstanding examples of the library as the heart of a mid-size city.

Libraries are not immune from the challenges faced by communities; in fact, they are often an important resource for connecting people in their community with services and support. In speaking with public librarians, we heard about the opioid problem, lack of jobs, and food insecurity among their patrons. One librarian told us they fear that one day medical intervention will be needed in the library or come too late for addicted patrons. Many libraries provide resume writing clinics and help patrons submit job applications online. Other libraries are providing free summer lunches to youth, age 1-18.

Image credit: “Lawrence Public Library in Lawrence, Kansas” by Beth Cramer and John Boyd. Used with permission.

Image credit: “Lawrence Public Library in Lawrence, Kansas” by Beth Cramer and John Boyd. Used with permission.The most appreciated services we found for bicycle tourists and other non-residents in the library were the simple things often taken for granted: a welcoming space with air-conditioning; electricity to charge our devices; internet connection; and the hospitality demonstrated by the library staff. One particularly hot afternoon, we witnessed bicycle tourists camping at the city park. As we passed the park several times that day, we were puzzled why anyone would choose to sit in 102-degree temperatures while there was a wonderful library only three blocks away. Now, whenever we meet other bicycle tourists in town, we let them know that a library is just minutes away.

Featured image credit: “Brownstown Branch Library in Brownstown, Illinois” by Beth Cramer and John Boyd. Used with permission.

The post Librarians on bikes: cycling through US libraries appeared first on OUPblog.

July 18, 2018

Pidgin English

There will be no revelations below. I owe all I have to say to my database and especially to the papers by Ian F. Hancock (1979) and Dingxu Shi (1992). But surprisingly, my folders contain an opinion that even those two most knowledgeable researchers have missed, and I’ll mention it below for what it is worth.

Several important dictionaries tell us that pidgin is a “corruption” of Engl. business, and I am not in a position to confirm or question their opinion. But those who enjoy essays on etymology usually want to know more than the final verdict, whether it is “origin unknown” or “from Latin via Old French.” The path of discovery often reads like a thriller and is more entertaining than the final piece of distilled truth, especially because dictionaries tend to shower users with cognates and pretend that this is what people expect. However, before going on, I would like to say why I put corruption, at the top of this paragraph, in quotes. (The quotes are present in the entry Pidgin in the original edition of the OED.)

True Pigeon (English?). In the past, the word Pidgin was occasionally spelled as Pigeon. Image credit: “Venice St Mark’s Square Italy Venezia Pigeons” by Charly_7777. CC0 via Pixabay.

True Pigeon (English?). In the past, the word Pidgin was occasionally spelled as Pigeon. Image credit: “Venice St Mark’s Square Italy Venezia Pigeons” by Charly_7777. CC0 via Pixabay.For a long time, the word corruption graced the works of our best scholars, including Walter W. Skeat, James A. H. Murray, and Henry Bradley, the OED’s first editors (on Bradley see the post for 9 April 2014). Our modern dislike of this term may be a tribute to political correction, but in the traditionally non-judgmental context of historical linguistics, corruption and corrupted are indeed wrong words. Open any old book on the history of language, and you will read that speakers of the Romance languages corrupted Latin words. By the same token, even in the days of the empire, good Latin words experienced the corrupting influence of the unwashed rabble. Language change is “corruption” by definition. For centuries, law-abiding speakers of English said cometh, but uneducated northerners changed it to comes. Today, the deleterious effect of that process is obvious to all. Someone corrupted sneaked into snuck and dived into dove. Corruption is ineradicable: Shakespeare corrupted Chaucer’s English, and we corrupted Shakespeare’s idiom. If pidgin is indeed the way Chinese speakers pronounced business, they did what they could: we witness change, adaptation, or alteration, not corruption, which presupposes an evil intent.

Several names stand out in the attempts to explain the origin of the word pidgin. One such name is Charles G. Leland. Ian Hancock mentioned Leland’s “apparently little-noticed suggestion” about the derivation of pidgin. His remark shows how short our memory is. Leland (1824-1903), an American-born author, was not simply known, but famous at his time. Folklorists and ethnographers still use his books, though they find that he “corrupted” a good deal of the information at his disposal. His humorous “ballads” enjoyed tremendous popularity, and his interest in Pidgin English was not a passing whim. Leland’s book Pidgin-English Sing-Songs and Stories in the China English Dialect was written in the same vein as his ballads that used a mixture of broken English and German. In that book, he wrote: “As the term wallah in Hindu, and that of engro in Rommany (sic), are applicable to any kind of active agent, so pidgin is with great ingenuity made expressive of every variety of calling, occupation or affair.” A correspondent to Notes and Queries (10/V, 1906: 91) wrote: “‘Pidgin English’ has not much literature, but Leland is its poet-laureate.”

Charles Godfrey Leland, to whom the etymology of the word Pidgin owes a debt of gratitude. Image credit: United States author, poet and folklorist Charles Godfrey Leland via United States Library of Congress. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Charles Godfrey Leland, to whom the etymology of the word Pidgin owes a debt of gratitude. Image credit: United States author, poet and folklorist Charles Godfrey Leland via United States Library of Congress. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Leland noted that some people derived pidgin from Engl. business, while other traced it to Portuguese (ocu)paçāo “business transaction.” Unfortunately, he did not say who those “others” were. There is nothing improbable in his etymology: “…the Portuguese were among the first European traders in West Africa, Asia, and the Americas, and one might readily assume that some word for ‘trade’, ‘business’ or ‘job’ was used by them” (Hancock). Also, Portuguese pequeno “little” (known to English speakers from the ethnic slur pickaninny), a derisive name for the jargon (pequeno portuguēs), has been suggested as the source of pidgin.

Another important name in the study of the etymology of pidgin is David Kleinecke. In his article (1959), he pointed out that in 1605 Captain Charles Leigh had planted a colony at the mouth of the Oyapock River. A letter from Master John Wilson of that colony is extant. It is said there that “the Pidians could not at all times provide them that they wanted.” Kleinecke wove an ingenious theory around this single occurrence of Pidians. He believed that such tribal names in West Guiana as Mapidian contain the same element as Pidian, allegedly the local name for “people,” which, as Kleinecke suggested, was carried from the west to the East Indies by English sailors and finally reached China. On the face of it, contrary to what Hancock says, this reconstruction has little appeal. The equation has too many unknowns. But Hancock showed that, most probably, Pidians is a misspelling for Indians. In that letter, Indians appears many times, and the mysterious Pidians only once. Most probably, it is a ghost word.

We could have ignored Kleinecke’s idea if it had not been supported by two eminent linguists: Robert A. Hall, Jr and Eric Hamp. As early as 1955, Hamp brought out a book Hands off Pidgin. It was followed by Pidgin and Creole Languages (1966), but to the American public Hamp is (or was) known as the author of another book with the fiery title Leave Your Language Alone, which five years later (in the second edition) was renamed as Linguistics and Your Language, a paean to the descriptive, as opposed to the prescriptive, approach to language. Hall’s main areas of research were Romance and Creole linguistics, but he enjoyed the role of an enfant terrible and toward the end of his career went so far as to defend the authenticity of the Minnesotan Kensington Stone. In his books, he pointed to the phonetic difficulty of turning business into pidgin and suggested a rather unconvincing remedy for improving the situation, so that it is only natural that in a 1974 review he supported Kleinecke’s derivation of pidgin.

The Oyapock River today. The early British colony there failed early. Image credit: he Maripa Falls on the Oyapock River as seen from the French Guiana side of the border. Brazil is on the other side. Photo taken on 5 June 2005, by Arria Belli. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The Oyapock River today. The early British colony there failed early. Image credit: he Maripa Falls on the Oyapock River as seen from the French Guiana side of the border. Brazil is on the other side. Photo taken on 5 June 2005, by Arria Belli. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Another advocate of the Pidians is Eric Hamp, a specialist in Celtic and Balkan linguistics and an astoundingly prolific author. The number of his short publications (sometime a paragraph or two of printed text) probably exceeds a thousand. One of them (1977) is on “a vastly preferable explanation [of the origin of pidgin] supported… by at least one shred of documentation from an appropriate chronological depth.” I suppose that Hamp did not see the full text of Wilson’s letter; if he had read it, he might have questioned the value of that “shred.” Also, the Hebrew of London speakers has been suggested as the environment in which the word pidgin originated (a rather hopeless fantasy), and above I promised to cite a conjecture missed by the best speicialists. Its author is Major H. R. E. Rudkin, and, for some reason, it appeared twice in Notes and Queries (vol. 162, 1932: 109 and the same volume, 1933: 153), though in a slightly different form.

In “his humble opinion,” it was much more likely that pidgin should be traced to Peking, pronounced approximately as “pey jing,” meaning “Northern Capital.” He explained: “When Englishmen were first permitted to enter China, it is most probable that Peking was the first large city they visited, and it was only after protracted negotiations with the Emperor that they were allowed to enter any other parts of that forbidden land. It is therefore only natural to infer that the jargon they and the Chinese used as a medium of communication should have come to be known as ‘Pei Ching; or ‘Pay Jing’ or ‘Pidgin’ English.” Above, I noted that the most recent publication on the word pidgin I know goes back to 1992. Quite possibly, since that time someone has discovered Rudkin’s contributions, the more so as my 2010 bibliography of English etymology features both, but I decided to mention them for safety’ sake. I needn’t point out that the name of the capital of China is now pronounced as Beijing in English.

Both Portuguese paçāo and Engl. business are rather hard to transform into pidgin, and Dingxu Shi explained at length why business is a better candidate. Kleinecke’s Pidian is perfect, but it is, most likely, a phantom. I wonder what specialists will say about Pay Jing English as the source of this intractable word. They will probably discard it, for, as Dingxu Shi explained, in a nineteenth-century phrase book, the entry for business is presented by two Chinese characters, pronounced as [pi] and [tsin]. However, couldn’t this word be a “derivative” of pidgin? Hancock also knew a similar word. The evidence for [pi tsin] is late, as are all the attestations of pidgin, while the first contacts between the English and China go back to the 1620. With this word we are, I daresay, between the Devil and the deep blue sea.

Featured Image: This is the way British ships at Macau probably looked like four hundred years ago. Image credit: East Indiaman‚ Kent off Deal‘, England by William John Huggins. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Pidgin English appeared first on OUPblog.

Immuno-oncology: are the top players changing the field?

Immunotherapy is a form of treatment to improve the natural ability of the immune system to fight diseases and infections, with immuno-oncology (IO) focusing on combatting cancer specifically. Novel immunotherapies are a possible solution for cancers that don’t respond to standard cancer treatments, either as standalone or in combination therapy. IO is changing the approach of many research and pharmaceutical companies and merely keeping up with this new, ever changing environment requires a strategy in itself.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have been a major talking point in the clinical landscape and investment into their development continues to expand since approval of the first compound in 2011. The global ICI market is predicted to exceed $25 billion USD by 2022, and over 940 agents are currently under investigation in clinical trials. Are all these treatment possibilities beneficial or are they simply adding to an already overcrowded market?

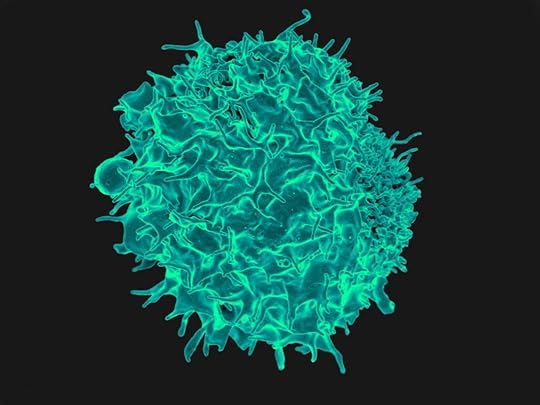

Immune checkpoints are regulatory proteins of the immune system that either stimulate or inhibit the functioning of the system. In cancer cells, these proteins are activated to downregulate immune responses and prevent T cells from fighting against them. Immune checkpoint inhibitors target these proteins to block their function and restore that of the immune system to halt further proliferation of cancer cells. Currently approved ICIs target CTL4-A, PD-1, and PD-L1, and have since proved their worth due to their potential use against many types of cancer.

CTLA-4 is expressed by T cells once activated and induces an inhibitory signal to the T cells. This affects the ability of the T cells to destroy cancer cells. However, inhibitors stop this process from occurring and turn off the inhibitory process, allowing cytotoxic T cells to act on the cancerous cells. Ipilimumab (brand name Yervoy) is a monoclonal antibody that was the first CTLA-4 inhibitor to be approved for the treatment of melanoma in 2011, firstly to treat advanced tumours or those that cannot be surgically removed. In 2015, ipilimumab was approved as adjuvant therapy and is currently being investigated in numerous clinical trials for the treatment of other cancer types.

Image credit: Colorized scanning electron micrograph of a T lymphocyte by NIAID. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

Image credit: Colorized scanning electron micrograph of a T lymphocyte by NIAID. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.PD-L1 ligands supress the immune system in various clinical scenarios, such as pregnancy and tissue allografts—but their role in cancer progression makes them a viable target for IO treatment. PD-L1 is highly expressed on cancer cells themselves, normally supressing the function of cytotoxic T cells. Blocking the binding of PD-L1 to its receptor, PD-1, removes the brakes from the immune system, hence reducing the growth of tumours. Atezolizumab (Tecentriq) was the first PD-L1 inhibitor to be approved, and granted fast track status by the FDA in 2016 for treatment of urothelial carcinoma after chemotherapy failure.

Combination therapy of both anti-CTL4-A and anti-PD-1 compounds have been shown to be more effective than either in standalone treatment for metastatic melanoma, however this is associated with increased risk and frequency of adverse events, and varying results when resuming therapy. Resistance to ICIs is also becoming an increasing issue and is a threat to their success rate, although more common in patients specifically with renal cell carcinoma and non-small cell lung cancer.

Chimeric antigen receptor T (CAR-T) cell therapy is a key player in the IO game, making significant progress in the oncology field in the last 20 years. T cells are extracted from the patient and modified ex vivo to express a CAR. The engineered new T cells are then reintroduced into the body, allowing them to be able to recognize and bind to specific proteins on the surface of tumour cells, and thus the immune response is boosted.

The function of CAR-T cells can also be supressed by PD-L1 binding to PD-1, just as normal T cells would be. Therefore, additionally blocking PD-1 function may enhance the success of CAR-T cells and combined therapy trials are presently ongoing.

Costing approximately $475,000 USD per patient, this novel treatment is a huge investment, bigger than British health system capacity at present, and so it is only available at a clinical trial level. However, Chief Executive of NHS England Simon Stevens states clearly that this is an area we must embrace and that the benefits are definitely worth the spend.

The scope for immunotherapy to provide precision medicine is growing especially when using multiple treatments in combination with each other. However, the pressure also falls onto ensuring we have the correct diagnostic and informatics tools to correctly and efficiently detect and treat cancers. The emerging treatments on the market need to be correctly supported by clinicians and systems alike to perform to the best of their ability. Regardless, checkpoint inhibitors and CAR T therapy are just a couple of treatments harbouring huge potential within oncology and part of a wider emerging industry to definitely keep an eye on.

Featured image credit: CGRB pipetting robot by Shawn O’Neil. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Immuno-oncology: are the top players changing the field? appeared first on OUPblog.

Who are the super-rich and why they are paid so much?

One of the most common arguments against contemporary capitalism is that it generates extreme inequalities. Few individuals – it is often said – earn huge earnings, while the rest of society has to struggle to make ends meet. But, who are the super-rich and why they are paid so much?

Observing the composition of top incomes reveals a striking novelty for what concerns the “who” question. In fact, while in the past, the large majority of individuals belonging to the richest segment of the population included rentiers or entrepreneurs, in the last few decades there has been a considerable increase in the number of “working super-rich” accessing the top income bracket, as shown by Alvaredo and colleagues. In Italy, for the richest 1% of the population, earnings (from employment and self-employment) accounted for the 46.4% of the total in 1980 while they accounted for 70.9% in 2008 and, similarly, among the 0.1% richest segment of the population, the share of earnings rose from 29.5% to 66.2% in the same period. Among the working super-rich, few selected professions are often at the top of the income parade: sportsmen, singers, artists, writers, CEOs.

The answer to the “why” question is instead much more challenging. There are currently at least three – not mutually exclusive – explanations. The first explanation hinges on the differentials in talent/productivity among individuals that, in some markets, can be magnified into huge differences in earnings. Rosen refers to markets in which consumers are able to identify who are the best performers, they prefer to be served by “the best”, and technology allows for joint consumption. Better performers can thus draw large audiences, for instance, in football stadiums, or via TV or selling their books or albums worldwide, with a cost of production largely independent of the size of the audience.

A second explanation, proposed by Adler, suggests that superstars might emerge among equally talented performers due to the positive network externalities of popularity. Actually, the appreciation of a particular performer (e.g. football player, singer, or artist) grows with the knowledge consumers have acquired about him/her through conversations with other people. In fact, as a performer’s popularity increases, it becomes easier to find other fans, because consumers are better off patronising the most popular star as long as others are not perceived as clearly superior.

Currency finance the dollar cash by pasja 1000. Public domain via Pixabay.

Currency finance the dollar cash by pasja 1000. Public domain via Pixabay.As a third explanation, extraordinary earnings might be associated with the bargaining power exerted by superstars. For instance, managers and CEOs in large companies might be able to fix their own remuneration independent of productivity, exploiting asymmetric information with respect to shareholders, while players in team sports can achieve wage increases by threatening the club owner with acceptance of a better deal from another team relying upon professional agents in order to negotiate better deals with team’s owners, as suggested in the book by Blair.

Providing empirical support to these explanations is often complicated due to difficulty of finding appropriate data. Sport statistics represent an exceptional opportunity since “we know the name, face, and life history of every production worker and supervisor in the industry”, as noted by Kahn.

At least for what concerns football players, the interpretation of extraordinary earnings based only on very talented workers who “win and take all” seems to be largely incomplete. Investments in popularity and in the choice of the “right” agent seem to be equally – or even more – remunerative than having good feet. Players seem to know this very well considering the time they spend on their social network accounts. Similarly, professional agents are gaining popularity becoming sometimes even more famous than the players they represent. With a few possible differences across sectors, these factors are likely to also explain the earnings of other super-rich such as actors, musicians, and virtually all workers in sectors characterised by a large audience. Whether or not this is fair remains an open dispute. What is less contentious is that these superstars arise in very special markets in which very few individuals play and the rest enjoy the performance. Not exactly competitive markets.

Featured image credit: Soccer stadium football by Free-Photos. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Who are the super-rich and why they are paid so much? appeared first on OUPblog.

July 17, 2018

Enjoying our Universe [slideshow]

What do we mean by “the Universe”? In the physics community, we would define “the Universe” as all “observable things”, ranging from the entire cosmos to stars and planets, and to small elementary particles that are invisible to the naked eye. Observable things would also include recently made discoveries that we are slowly coming to understand more, such as the Higgs boson, gravitational waves, and black holes. While it might take incredibly complex (and costly) instruments to prove that these phenomena occur, we are able to witness them and prove their existence.

As a fundamental understanding of our Universe is being developed, it is clear we are currently only exploring our Universe, since the hypothesis of the multiverse is yet unproven. Our unique and complex world stills holds many mysteries but those spectacles that have been documented over time show the beauty in the physics of our Universe.

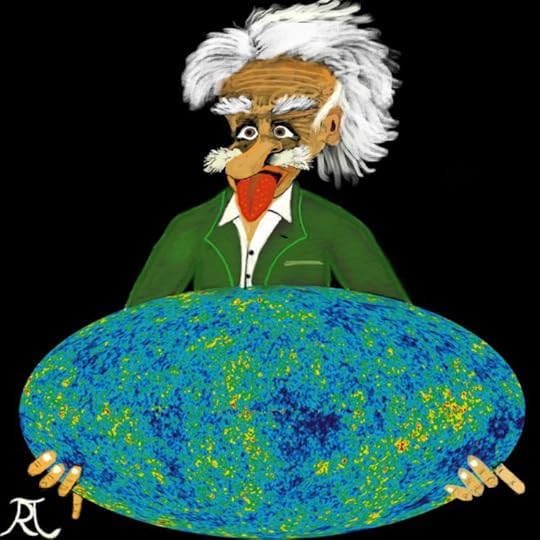

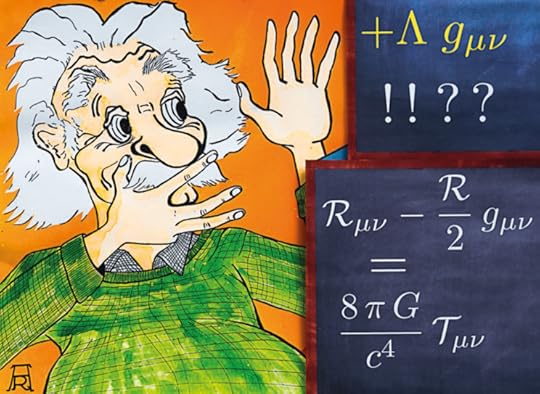

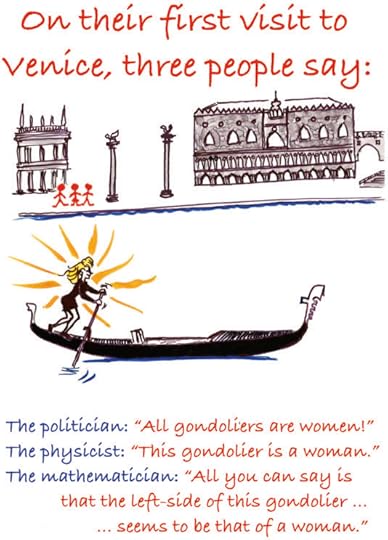

Here we present several original illustrations by Alvaro De Rújula that take us on a little tour of the “observable things” that make our Universe beautiful.

Albert Einstein holding the visible Universe, to whose current understanding he contributed so significantly.

Image credit: Albert Einstein by Alvaro De Rújula. The visible universe CC-00 via WMAP/NASA. Used with permission.

On the lower one, the left-hand side describes gravity, the right-hand side its “source.” The symbols c and G are the speed of light and Newton’s constant, which determines the magnitude of the gravitational forces μ and ν are “indices” that “run” from 0 to 3 for time and the three dimensions of space. The 8 and π are other rather well-known numbers.

Image credit: Albert Einstein and his blackboards by Alvaro De Rújula. Used with permission.

Image credit: The diverse perceptions of different professionals by Alvaro De Rújula. Used with permission.

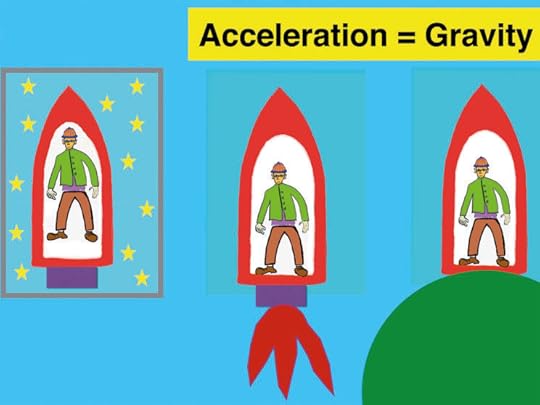

The guy in the rocket would be floating in it (if in a region with no significant gravitational forces), or if he and the rocket were in free fall in a gravitational field, as astronauts are in the Space Station (left). If he is in an accelerating rocket (middle) or at rest in a gravitational field (right) he cannot tell unless he cheats (by looking out of a window).

Image credit: Acceleration = Gravity by Alvaro De Rújula. Used with permission.

Typical sizes in meters are shown on the left-most column. Three of the four known fundamental forces are listed (the weak force does not play a role in stabilizing material objects). Nuclear forces binding protons and neutrons in nuclei are a consequence of the more fundamental Quantum Chromodynamic interactions between quarks. Analogously, chemical forces between atoms are a peripheral manifestation of the Quantum Electrodynamic forces between electrons and nuclei.

Image credit: All things made out of “ordinary” matter. by Alvaro De Rújula. Used with permission.

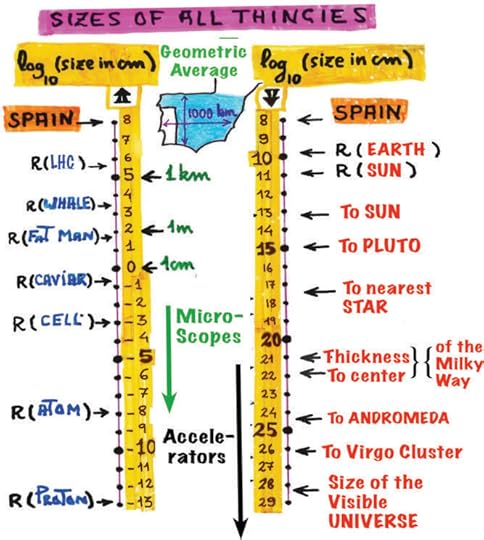

The sizes of “all” things, on a logarithmic scale in centimetres. The Large Hadron Collider has a radius of about 7 km. A caviar egg, a few millimeters. Spain has a geometric (or logarithmic) average size, in the ensemble of all sizeable things.

Image credit: The sizes of “all” things, on a logarithmic scale in centimetres by Alvaro De Rújula. Used with permission.

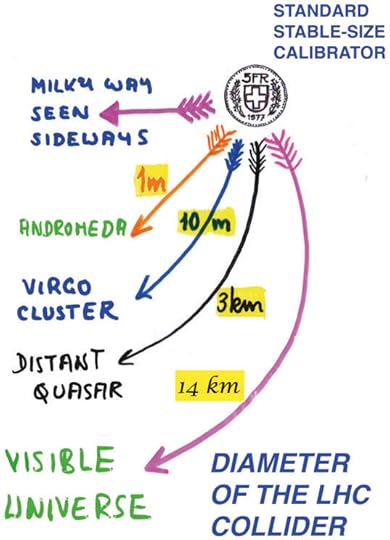

Large distances, compared to the full sixe of our Galaxy, represented by a 5 Swiss-Franc coin. A quasar is a gigantic black hole, visible from afar given the intense luminosity of the jets it spits out as it swallows the central areas of its “host” galaxy. Virgo is the cluster of galaxies to which we belong. The ratio of the sizes of the Galaxy and the visible Universe equals that of the coin and the LHC.

Image credit: Large distances by Alvaro De Rújula. Used with permission.

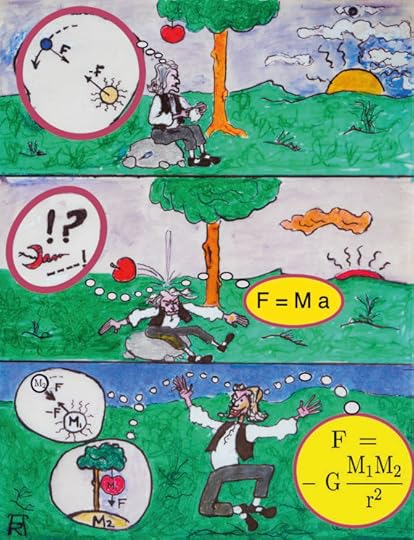

Newton’s laws of the equal but oppositely directed forces of action and reaction (top). Newton’s apocryphal apple leading him to discover the relation between force, mass, and acceleration (F=Ma) (center), as well as the expression for a gravitational force between two objects, in terms of their masses and the distance between their centers (bottom).

Image credit: Newton’s laws by Alvaro De Rújula. Used with permission.

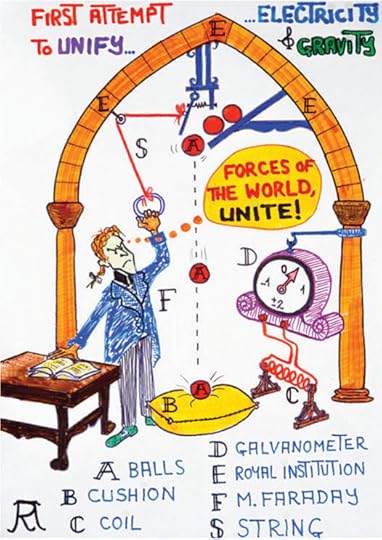

Faraday’s failed experiment on what would have been this second law of induction (of electricity by gravity). The (super?) string may have been premonitory. Many of Faraday’s instruments are preserved at the Royal Institution in Mayfair, London.

Image credit: Faraday’s failed experiment by Alvaro De Rújula. Used with permission.

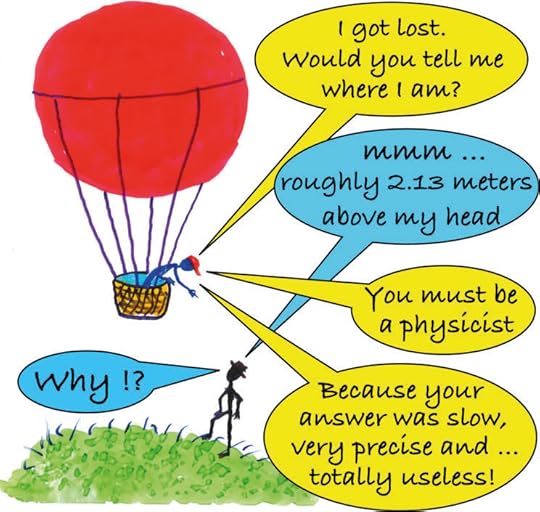

Image credit: A dialog with an incorrect conclusion by Alvaro De Rújula. Used with permission.

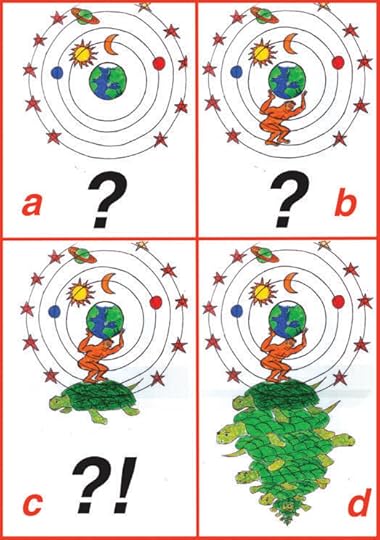

Image credit: Ancient views on gravity and the Universe around us by Alvaro De Rújula. Used with permission.

Featured image: “Milky Way Universe Person Stars Looking Sky Night” by Free-Photos. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Enjoying our Universe [slideshow] appeared first on OUPblog.

The goals of medicine do not stop at the edge of the body

Over the last 100 years, the world, people, and our society have changed beyond measure. So have diseases, and we are now almost 75 years into the first ever age where cure of disease, successful organ transplants and near complete recovery from trauma has been possible. Despite all of this change, however, medical school curricula have hardly changed in a hundred years. Medical students are educated in more or less the same fashion as they were when I attended medical school more than 60 years ago. This is despite almost every medical school attempting to revise their curricula more regularly than locusts swarm, but with far less impact.

Medical science has advanced exponentially, as has technology, but, as vitally important as those are, they are only tools that working doctors use in caring for patients. We live in an age and society where science is a social force; where many believe that in medicine itself it is science and technology that makes diagnoses and treats patients. This is not true. Physicians using science and technology treat patients and are the diagnosticians. Physicians, however, use much more than their technical knowledge. Medicine is a field of relationships: the relationship between patients and doctors; relationships with other doctors and with the many other professionals involved in the care of patients; relationships with patients’ families; and with institutions such as hospitals, hospices, laboratories, and radiology units. Excellence in maintaining, growing, and utilizing these relationships is crucial to patient care. If this were not the case, and it was doctors’ knowledge of sci-tech that mattered most, then young, recently-trained physicians would be the most skilled doctors of all.

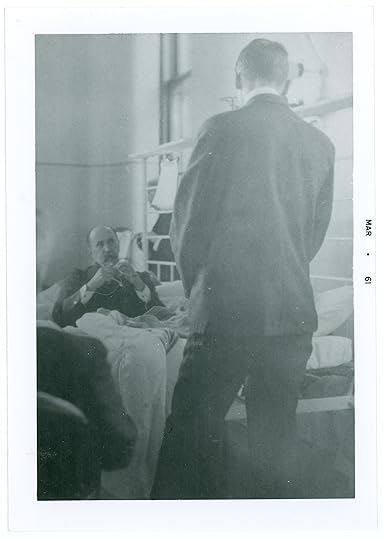

‘William Osler at a Patient’s Bedside. Johns Hopkins Hospital, circa 1903’ Reproduced by permission of the Osler Library of the History of Medicine, McGill University.

‘William Osler at a Patient’s Bedside. Johns Hopkins Hospital, circa 1903’ Reproduced by permission of the Osler Library of the History of Medicine, McGill University.In clinical medicine—the care of sick patients in offices and clinics—it is widely known that physicians become better as they gain experience. This was true in times past and it is, if anything, more the case now. The basic tools in the care of patients are old fashioned—finding out the patient’s narrative and examining the patient.

Sadly, physicians trained in recent years are deficient in these skills. Furthermore, almost every hospital, medical school and other medical institution claims to be person-centered, but the medicine practiced there remains centered on disease. We believe that this is a result of holding on to a 200-year-old understanding of human illness: that if someone is sick they must have a disease. According to this longstanding concept, the job of the doctor with a sick patient is to find the disease. Since diseases are found in the body the doctor’s primary concern is with the sick person’s body.

To counter this, a different definition of illness is required when treating patients, one which reflects the fact that people consider themselves sick when they cannot accomplish their goals and purposes. Sick people’s functions can be impaired in a plethora of different ways, rendering them unable to accomplish their personal goals as they could when they were well. Since the patient’s goals and purposes are specific to them, an approach to medical care based on restoring or improving function becomes irrevocably patient-centered, and knowledge about diseases is relegated to a supporting, albeit important, role. It is now the role of the doctor to focus on this patient-centered approach in their daily practice by becoming not only as knowledgeable as they can about their particular patient, but as knowledge as possible about people in general.

The next step in medical training is for this to be translated into medical pedagogy. A medical curriculum is needed where knowledge about people is central: knowledge about normal personhood, about anatomy, physiology, function, and functioning —not only physical function but how persons function in their lives and in society. The educational blueprint must then advance to abnormal structure and function, and to how illness is experienced, recognized, and diagnosed. The environment of the medical school must place a premium on relationships: doctor to patient; doctor to learner; learner to patient. Such a curriculum has been laid out. Elements of it have been developed and delivered. It is about time it became ubiquitous.

Featured image credit: Strong Women by Samantha Sophia. Public Domain via Unsplash .

The post The goals of medicine do not stop at the edge of the body appeared first on OUPblog.

London keeps it psychedelic at audio-visual performing arts festival

Entering into a darkened room crowded with people, there is a powerful smell of incense. A robed figure touches the forehead of each initiate, uttering an incantation. In the centre, a figure crouches, swaying slightly, engaged in some kind of mystical ritual. Amidst deep sonic drones, the figure seems to burst into flames and transform…

To the uninitiated, this might sound reminiscent of an ancient ritual, such as the rites of the Eleusinian Mysteries in Ancient Greece, where as legend has it, Persephone erupted in a great fire for an audience intoxicated by the hallucinogenic brew kykeon. Yet the above is actually a description of Transcendence by Kimatica, a theatrical performance that utilises cutting-edge motion tracking and video mapping to make a dancer’s body seem to erupt with fire. This performance of Transcendence was staged as part of Splice festival, London 2018.

Splice, now in its third year, has quickly established itself as a significant event on the international circuit of audio-visual arts festivals and VJ events, which also includes Live Performers Meeting, Punto y Raya, Fulldome UK, and Seeing Sound to name just four. There is now a vibrant scene for this type of work, which typically combines moving image with sound and music in various forms. For instance, this year’s Splice also included live video mashups, VJ performances, live coding, audio-visual workshops, talks, and more. As in previous years, the festival places up-and-coming underground artists alongside seasoned pioneers in the field. In the latter category are Addictive TV, who returned to Splice this year to perform their Orchestra of Samples project, which takes sounds and video of many different musicians who the group met and recorded while touring internationally, and turns them into an audio-visual sample collage. Sampled drum breaks sit alongside flute, hang drum, and other exotic instruments, creating a blend that is accessible and visually appealing, while also retaining an irresistible sense of fun—something that is never lost at Splice, which in previous years has seen avant-garde work juxtaposed with video mashups by artists such as Coldcut (known for their sampladelic beat collages on Ninja Tune, but also their innovative VJ collaborations with HEX and music software) and the outstanding Wookie-electro jams of Eclectic Method.

For many, these audio-visual performances will of course seem very “new,” yet in fact there is a considerable history to this type of work, which goes back over a hundred years to the early “colour organ” instruments and the abstract “visual music” paintings of Kandinsky. The term “visual music” was later used to describe films by artists such as Oskar Fischinger and Len Lye, which featured colourful abstract animations arranged to music, and provided the inspiration for Walt Disney’s Fantasia (1940). This area was also later developed through the films of Jordan Belson and John Whitney; the liquid light shows of groups such as Joshua Light Show, Boyle Family, and Nova Express; and others. Increasingly, artists creating this type of work began to use early forms of computer graphics, eventually leading to the VJ culture of the late ’80s and ’90s, which saw VJs mixing computer graphics videos to performances by acid house DJs.

Perhaps due to the synesthetic nature of this type of work—which combines sound and image in abstract, kaleidoscopic combinations—these audio-visual works have often been associated with psychedelia and altered states of consciousness. For example: in the beatnik-era, filmmaker Harry Smith created hand-painted visual music films that he projected alongside jazz performances for artists such as Dizzy Gillespie, which he claimed were inspired partly by the visual hallucinations he saw listening to jazz while stoned. Along similar lines, in the ’60s USCO collective, Jordan Belson, and James Whitney created films that explored various ideas related to introspective conscious states. Another example from this period, “Humble Ben” Van Meter’s film Acid Mantra (1967) used composites of multiple layers of film to communicate states of trance-like sensory overload. Later, ’90s rave-era VJ mixes like Future Shock, Dance in Cyberspace, and the projections at mega-raves like Fantazia seemed to also take inspiration from LSD, constructing hallucinatory journeys through fractal universes and surrealistic computer graphics.

At Splice 2018, this trajectory of audio-visual work that relates to ideas of altered states of consciousness is still very much in evidence. Kimatica characterise their performance Transcendence as an altered states ritual, which aims to connect the audience with ancient forms of spirituality. Yet, the altered states theme was also manifested elsewhere at Splice this year in different ways. For example, a talk by Bristol-based video design studio Limbic Cinema discussed their projection mapping work on the project Ergo Sum, a piece written and directed by Sleight of Hand Theatre, which aims to communicate the subjective experiences of “characters living with psychiatric and neurological conditions, exploring the boundaries and transitions between hallucination and reality, and internal self versus the external world.” Elsewhere at the festival, an excellent talk by Weirdcore (the maverick designer behind anarchic live visuals for artists such Aphex Twin and MIA) also discussed a project in which his motion graphics are being used to illustrate the experiences of ravers coming up on ecstasy. This idea of representing internal, subjective experiences, is not a new one—but what makes this work so fresh and exciting is the way these artists are harnessing the power of the latest illusory audio-visual technologies to elicit altered states of consciousness for today’s audiences.

Featured image credit: Ergo Sum performance directed by Sleight of Hand Theatre, 2018 by Limbic Cinema. Image used with permission.

The post London keeps it psychedelic at audio-visual performing arts festival appeared first on OUPblog.

July 14, 2018

Shariah: myths vs. realities

For many in the West today, “Shariah” is a word that evokes fear—fear of a medieval legal system that issues draconian punishments, fear of relegation of women and religious minorities to second-class citizenship, fear of Muslims living as separate communities who refuse to integrate with the rest of society, and fear that Muslims will seek to impose Shariah in America and Europe.

Candidates in American presidential elections, as well as far right anti-immigrant and anti-Muslim political parties in Europe, ultra conservative Christian leaders, and anti-Islam and anti-Muslim activists’ publications, blogs, and websites warn of the evils of Islam and Shariah and a clash of civilizations between Islam and the West, a fear that is often reinforced by sensational media headlines focusing on extreme behaviors by tiny minorities rather than the majority populations of law-abiding, contributing citizens. Indeed, a 2015 Media Tenor analysis of media coverage in America and Europe found that over 80% of stories on Islam were negative. As a result, many have come to believe that there is a “clash of civilizations” between Islam and the West, and fear a triple threat—political, civilizational, and demographic—further reinforcing fear of a “Shariah creep.”

In Europe, worries about the influx of Muslim refugees and immigrants, Muslim birth rates outpacing those of “native” populations, and visible symbols of Islam’s presence and perceived foreignness and difference—veils, beards, “Islamic dress,” halal meat, and mosques—have given rise to concerns about the loss of native identity, culture, and civilization, and have led to calls for restrictions on immigration in Europe. In Europe and North America, terrorist attacks by those claiming inspiration from ISIS further fuel fear of a threat from within, particularly that Muslims, both terrorist and mainstream, seek to impose Shariah on the West. As documented by organizations such as the Center for American Progress and islamophobianetwork.com, this fear was deliberately stoked between 2001 and 2012 by eight donors who contributed more than $57 million to promote fear of Islam, Muslims, and Shariah, claiming that they were working to overthrow the US Constitution and legal system and install a radical Islamic caliphate that will punish and subordinate all non-Muslims. In 2016, the Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR) and the Center for Race and Gender at the University of California, Berkeley, examined support for radical organizations. Their report, “Confronting Fear,” based on tax filings, showed that between 2008 and 2013, a US-based Islamophobia Network of some 33 groups received $205,838,077 in total revenue.

Demographic myths and fears are squarely overcome by reality. The Pew Research Center estimates that Muslims constitute only about 1% of the US population (3.3 million Muslims of all ages living in the United States in 2015). That share is expected to double to 2% by 2050. Even in Europe, Muslims currently constitute only 6% of the population, having grown about one percentage point per decade, from 4% in 1990 to 6% in 2010. This pattern is expected to continue through 2030, when Muslims are projected to make up 8% of Europe’s population—hardly the demographic threat proclaimed by nativists.

Similar to the demographic fear, the projected danger of Islamization and implementation of Shariah in the United States has also been based on a myth. In fact, no Muslim or Muslim organization has tried to implement Shariah to replace the Constitution or the American legal system. Yet, between 2010 and 2017, 120 anti-Shariah law bills had been introduced in 42 states. In 2017 alone, 13 states introduced an anti-Shariah law bill, with Texas and Arkansas enacting the legislation.

The volume of anti-Shariah bills begs the question of what, exactly, Shariah is, what it means to Muslims, and the varied roles that Muslims want it to play in the public sphere. Shariah is often–mistakenly–conflated with “Islamic law,” as it is implemented in certain countries today, typically citing those that most flagrantly violate international standards of human rights. Yet, Shariah and Islamic law are not the same. Shariah refers to the principles, values, and objectives found in the Quran and Muhammad’s example, including justice, protection of life and property, and care for the marginalized and dispossessed, among others. Many Muslims therefore maintain that Shariah, properly defined and understood, upholds the values of good governance, representative government, the public interest, social justice, human freedoms and rights, and individual accountability. While these principles and objectives do not change, what can—and should—change is Islamic law, or jurisprudence (fiqh), which is the human elaboration of how those values and objectives are to be put into practice concretely.

The volume of anti-Shariah bills begs the question of what, exactly, Shariah is, what it means to Muslims, and the varied roles that Muslims want it to play in the public sphere.

Ideally, as societies change and encounter new challenges and circumstances, so should Islamic law. In the past, Islamic law was developed for Islamic empires and societies with Muslim majority populations, not for Muslims living permanently in non-Muslim societies. While it was expected that Muslims might live for a time outside the lands of Islam, the expected ideal was to live in a Muslim society. Thus, there was no perceived need to develop a law for permanent minority communities.

Today, not only do some Muslims live as permanent minorities in non-Muslim communities, but Muslims living in Muslim-majority countries also often recognize the need for fresh interpretations that reflect new knowledge bases (such as advances in science and medicine), fields of expertise (such as technology), and even global challenges (such as climate change). As with other major faiths such as Christianity and Judaism, balancing respect for the past while addressing the needs of the present is a major concern for Muslim jurisprudents today. Rather than a threat or blind adherence to the past, the goal of reformers and their supporters is to reinstate the original purpose of Shariah: to serve as a source of guidance and protection for believers, wherever they live. That means, in instances where the laws in place are contrary to the objectives and values that Muslims uphold, they, like members of other faith traditions, can work for change through the legal processes that exist, respecting democratic processes and the pluralistic nature of society, and working together with others to introduce legislation and lobby the government concerning laws or appointments of Supreme Court judges.

Featured image credit: “A public demonstration calling for Sharia Islamic Law in Maldives 2014” by Dying Regime. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons .

The post Shariah: myths vs. realities appeared first on OUPblog.

Animal of the Month: 5 facts you should know about misnomered orcas

For centuries, orcas have accrued a myriad of different names: Orcinus orca (which translates roughly as “demon from hell”), asesinas de ballena (whale killers), Delphinus orca, grampus, thrasher, blackfish, killer whale, to name a few.

The names of these animals are overtly violent, but what do we actually know about the alleged “demons from hell”? This month, we want look at the facts about killer whales, and debunk the centuries-old mystery and fear surrounding orcas.

1. Orca sightings were first recorded in 79 CE

Gaius Plinius Secundus, better known as Pliny the Elder, was the first person to have recorded a description of killer whales. Based upon Pliny’s description of the creature, the orca seemed to have instilled fear into him. Penned in his encyclopedic Naturalis Historia, Pliny painted orcas as “an enormous mass of flesh armed with teeth,” as well as “and with its teeth tears its young, or else attacks the [balaena] females which have just brought forth, and, indeed, while they are still pregnant.” Moreover, Pliny describes the orca “as though the sea were infuriate against itself.” Pliny originally bore witness to Orcinus orca in 50 CE, when an orca had been drawn in by a ship from Gaul to the harbor of Ostia, Rome’s port city. The Romans, no stranger to watching animals die, attacked the killer whale until it succumbed, though not without sinking at least one Roman vessel beforehand. The earliest recordings of orcas are rooted in violent depiction, stemming centuries of fear from human observers. However, these “killer whales” are unlikely to attack humans.

2. Orcas are maritime carnivores

The diet of an orca specifically revolves around the ecosystem of a given pod, but the primary and typical diet of an orca consists of salmon, seals, porpoises, sea lions, and minke whales. Other regional pods prey on squids, octopi, otters, rays, dolphins, sharks, baleen whales, as well as turtles, seabirds, and even penguins. The orca hunting strategy is incredibly complex, given the size, high intelligence, and sociability of pods, allowing orcas to dominate the top of the marine food chain.

Image credit: “Orca Lofoten Islands Dusk Seascape” by Seaurchin. CC0 via Pixabay.

Image credit: “Orca Lofoten Islands Dusk Seascape” by Seaurchin. CC0 via Pixabay.3. Orcas are cetaceans

What is a cetacean? Cetacea is an order of marine animals that comprises whales, dolphins, and porpoises. Cetaceans have hairless bodies, no hind limbs, a horizontal tail fin, and a blowhole on top of their head for breathing. While cetaceans live in the water, they are also mammals, and thereby must resurface for air. Orcas were also given the categorization in 1758 of Delphinus orca, literally translating to “demon dolphin.” Of the more than seventy species of toothed whales, they are second in size only to the sperm whale—full-grown males can reach near thirty feet in length and almost twenty thousand pounds.

4. Orcas are acoustic creatures

The anatomy of an orca is incredibly complex and sophisticated. Orcas are equipped with strong underwater eyesight, but moreover, orcas are acoustic. By manipulating air in nasal passages below their blowholes, they generate a wide range of sound waves. Orcas have biosonar, providing a natural sonar system common amongst cetaceans. Their biosonar enables orca pods to map their surroundings, locate prey, and even “see” inside the bodies of other animals—a cetacean version of ultrasound. Through biosonar, orca pods are able to establish their own dialect through the variety of whistles and pulsed calls unique to regional pods. These distinctive dialects frame orca identity, not unlike the role of language and accent in marking human ethnicity.

5. Orca culture follows a matriline

Female orcas reach sexual maturity around the age of nine and reproduce well into their forties with an average gestation period of approximately seventeen months, followed by a similar nursing period. Female orcas only reproduce every four to five years, allowing deep bonds between mother and calf. In contrast to many mammalian species, female orcas can live long after menopause and often assume leadership roles within their pod. These leadership roles take the form of a matriline, in which older females within the pod hold authority. These matrilines, in turn, form the building blocks of larger pods—some of which are remarkably stable. With no fixed residence, the only home individual orcas know is their pod, which structures foraging, sleeping, breeding, and belonging, often for their entire lives. Any separation of even a singular orca from a pod yields deep mourning and dismay amongst the highly intelligent and socially-interwoven pod, for the orca pod is a familial unit, perpetually in motion.

The post Animal of the Month: 5 facts you should know about misnomered orcas appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers