Oxford University Press's Blog, page 237

August 1, 2018

Modified gravity in plane sight

Our Galaxy—the Milky Way—is a vast rotating disk containing billions of stars along with huge amounts of gas and dust. Its diameter is around 100,000 light years. The Milky Way has many satellite galaxies (e.g. the Magellanic Clouds), which orbit around it. Most of these satellites lie in a thin plane and rotate within it. The same is also true for the satellites of our neighbouring galaxy, Andromeda. Though this has been known for many years, the origin of these satellite planes has remained a mystery. Several previous studies showed that similar structures are not expected in the standard picture of galaxies obeying general relativity: the law of gravity developed by Einstein that lies at the heart of how we understand our Universe. In this picture, we expect a nearly random distribution of satellites. This contradicts observations, even when disregarding the particularly problematic velocity data.

In the Einstein-inspired picture, the fast rotation speeds of stars in galaxy outskirts imply that galaxies are held together by huge amounts of unseen mass, called dark matter. In many galaxies, this dark matter needs to vastly outweigh the visible. However, nobody has ever discovered definitive proof that dark matter actually exists. Instead, scientists have managed to prove that it can’t be made of any fundamental particles that we currently know of (e.g. it can’t just be dead stars). If it was, the gravity of these stars—which is capable of bending light—would occasionally magnify the light of background stars in the same way that moving a lens across a small light would make it appear to brighten and then fade. Although this does sometimes happen, such microlensing events are too rare, implying that the dark matter must be made of objects whose mass is at least a million times smaller than that of the Sun. Thus, the theorised dark matter has to be a new particle that has evaded numerous very sensitive attempts to detect it (e.g. LUX Collaboration 2018, PandaX-II Collaboration 2018).

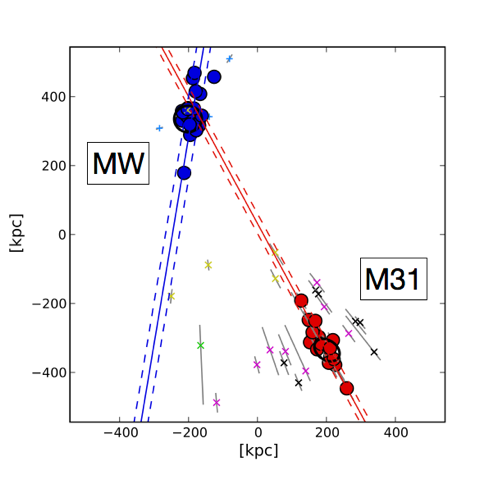

Image credit: The satellite galaxies of the Milky Way (blue) and Andromeda (red). Notice how both satellite systems are highly flattened. In this projection, both satellite planes are seen edge-on. The authors claim to have a model for how these mysterious structures formed, based on a past close flyby of the Milky Way and Andromeda that results from a major modification of Einstein’s law of gravity. Figure 16 of MNRAS 435, 1928–1957 (2013). Used with author permission.

Image credit: The satellite galaxies of the Milky Way (blue) and Andromeda (red). Notice how both satellite systems are highly flattened. In this projection, both satellite planes are seen edge-on. The authors claim to have a model for how these mysterious structures formed, based on a past close flyby of the Milky Way and Andromeda that results from a major modification of Einstein’s law of gravity. Figure 16 of MNRAS 435, 1928–1957 (2013). Used with author permission. An alternative theory called Modified Newtonian Dynamics (MOND) was proposed in the early 1980s by Israeli physicist Mordehai Milgrom. MOND says that gravity is much stronger than predicted by Einstein. Instead of following the usual inverse square law, gravity from any object follows a gentler inverse distance law once it gets weaker than a certain acceleration threshold typically reached in the outskirts of galaxies. As a result, instead of becoming one quarter as strong at double the distance from a galaxy, MOND says its gravity is still half as strong. Importantly, this change only applies once gravity gets weaker than a very low threshold that is one hundred billion times weaker than the gravity we experience on Earth’s surface. (Fun fact: the threshold is roughly the amount of gravity that an ant crawling on a glossy magazine would experience from just its cover). Thus, Milgrom’s proposal has very little effect here or elsewhere in the Solar System, where the inverse square law would still hold. But in the outskirts of galaxies, his proposed helping hand to Einstein’s gravity is enough to account for the fast speeds at which the stars and gas are observed to rotate. Despite its very limited freedom and its key equations being written down 35 years ago, MOND has proved amazingly good at predicting the rotation curves of a huge variety of galaxies spanning a factor of 100,000 in visible mass, all without inventing dark matter.

In a new study published by the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, it is claimed that MOND also provides a natural explanation for the satellite planes. The study assumes that the Milky Way and Andromeda started with plausible initial conditions (the “Hubble flow”) and had masses consistent with the stars and gas we actually detect in them. Solving the equations forwards, the galaxies end up with their observed distance and velocity—after a fashion. In MOND, their much stronger gravitational attraction implies they had a close flyby when the Universe was about half its current age.

This recent study conducted several simulations of the galaxies over the entire history of the Universe, varying parameters like just how close the galaxies got. The outer particles of both galaxies were knocked onto rather different orbits by the flyby. Amidst all this chaos, it was important to see if the outer particles of e.g. Andromeda ended up mostly rotating within a particular plane and, if so, whether this plane aligns with the real plane of Andromeda’s satellites.

Remarkably, they found some models in which the outer particles of both galaxies aligned with their observed satellite planes. The inner particles remain fairly undisturbed, so the simulations are compatible with the thin disk of the Milky Way that can be seen on a clear night. Moreover, the calculated time of the flyby is similar to when our Galaxy’s disk thickened suddenly to form its “thick disk.” Some of the particles in its simulated “satellite plane” are rotating in the opposite direction to the majority. The latest observations show that the fraction of these particles is similar to the observed fraction of “counter-rotating” satellites around our Galaxy. This phenomenon does not seem to arise around Andromeda, either in the simulations or in observations.

The study enabled researchers to observe realistic-looking satellite planes the first time anyone did a detailed investigation of the Milky Way–Andromeda flyby; this flyby is inevitable in MOND. Contrast this with the numerous efforts over more than a decade to try and explain the satellite planes in general relativity—it just doesn’t seem to work, regardless of how much dark matter you’re prepared to invent.

https://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Video_xy.mp4

Video credit: Simulation of the Milky Way (which comes in from the top) and Andromeda over the lifetime of the Universe, showing both galaxies roughly edge-on. Redder colours correspond to pixels with a greater amount of mass. 1 kpc = 3,260 light years. Author owned.

Feature image credit: Cosmos by geralt. CC0 by Pixabay.

The post Modified gravity in plane sight appeared first on OUPblog.

July 31, 2018

Back to school reading list for educators

Packing up your beach towels and heading back to the class room? To help make lesson planning and curriculum writing easier, we have prepared you a reading list from the Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education.

Curriculum:

Rethinking Curriculum and Teaching: Reexamines curriculum and teaching to view them as two interrelated concepts embedded in the societal, institutional, and instructional contexts of schooling. Question the technicist and reductionist treatment of curriculum and teaching. Explore the re-envisioning of curriculum and teaching in view of the educational challenges of the 21st century.

Preparing to Teach in Inclusive Classrooms: This article presents a critical analysis of inclusive teacher education. The article argues that while teacher education programs have changed dramatically over the last few decades, there are still areas where more progress could be made. It also argues for a need to re-conceptualize the way we prepare teachers so that they can confidently include all learners. It presents a framework, largely influenced by the work of Shulman, which could be applied for the preparation of pre-service teachers to teach in inclusive classrooms.

Creativity in Education: Creativity is an essential aspect of teaching and learning that is influencing worldwide educational policy and teacher practice, and is shaping the possibilities of 21st-century learners. Learn about pedagogical approaches to teaching.

The Classroom:

Achievement Motivation in Education: Achievement motivation theories are used to understand gender discrepancies in motivation across various academic domains. In the fields of education, educational psychology, and psychology, they examine motivation beliefs, goals, and aspirations of male and female students. Discover gender-related trends in academic achievements and motivation.

Social Emotional Learning and Inclusion in Schools: Inclusive classrooms provide new opportunities for group membership and creation of effective learning environments. Explore how to facilitate inclusion in the classroom as an approach and philosophy.

Trust in Education: There is a growing awareness of the crucial role that trust plays in every aspect of a school’s functioning and especially to student outcomes.

Relational Pedagogy: In recent years, relation pedagogy has developed in novel ways in response to ongoing efforts at school reform that is based on constraining view of education as the effective teaching of content. This view prioritizes methods, curricula, and testing, which overshadows the human relationship between teacher and student. Explore this pedagogical approach of caring.

Teachers as Conscientious Objectors: This article explores the role of teachers as potential catalysts for conscientious objection to practices and mandates that stand against or compromise their professional ethics. Read about how moral commitments can be a source of teachers’ resistance.

Featured image: Public Domain via Unsplash .

The post Back to school reading list for educators appeared first on OUPblog.

Epidemics and the ‘other’

A scholarly consensus persists: across time, from the Plague of Athens to AIDS, epidemics provoke hate and blame of the ‘other’. As the Danish-German statesman and ancient historian, Barthold Georg Niebuhr proclaimed in 1816: “Times of plague are always those in which the bestial and diabolical side of human nature gains the upper hand.” In the 1950s, the French historian René Baehrel reasoned: epidemics induce ‘class hatred (La haine de classe)’; such emotions have been and are a part of our ‘structures mentales … constantes psychologiques’. With the rise of AIDS in the 1980s and 1990s, this chorus resounded. According to Carlo Ginzburg, ‘great pestilences intensified the search for a scapegoat on which fears, hatreds and tension … could be discharged’. For Dorothy Nelkin and Sander Gilman, ‘Blaming has always been a means to make mysterious and devastating diseases comprehensible’. Roy Porter concurred with Susan Sontag: ‘deadly diseases’, especially when ‘there is no cure to hand … spawn sinister connotations’. More recently from earthquake wrecked, cholera-hit Haiti, Paul Farmer concluded: ‘Blame was, after all, a calling card of all transnational epidemics.’ Others can easily be added. The problem is: these scholars have produced only a handful of examples—sometimes, the Black Death in 1348-51 and the burning of Jews; sometimes, the rise of Malfrancese (or Syphilis) at the end of the fifteenth century; sometimes, cholera riots in the nineteenth century; and AIDS in the 1980s (but usually from the U.S. alone).

The collection and analysis of socio-psychological reactions to epidemic diseases taken from a wide range of sources from antiquity to the present tell a different story: few epidemics spurred hatred, social violence, or blame. Instead, before the 19th century, when epidemic diseases rarely possessed effective cures and all plagues were more or less medically mysterious, outbreaks of epidemics tended instead to elicit compassion and self-sacrifice that dissolved class and factional conflicts.

The Black Death of 1347-51 was a striking exception. With successive waves of plague in the later Middle Ages and Renaissance, however, the mass terror against Jews or any other minorities was not repeated. As early as 1530 and into the seventeenth century, accusations of intentional plague spreading (‘engraisseurs’ in France; ‘untori’ in Italy) emerged, but the numbers accused or executed never approached anything near the levels of 1348-51. Moreover, these accusations did not target marginal populations as is often supposed; instead, the trial records of the best-studied case, that of Milan’s plague in 1630, show the accused as ‘insiders’, beginning with solid native-born skilled artisans and ending with bankers and even the son of one of the most important military leaders of the city.

With the spread of cholera across Europe from 1830 to 1837, epidemics’ social toxins became more widespread and virulent. This explosion of hate and blame, however, again did not target the ‘other’. Rather, it was a class struggle, whose hate flowed in the opposite direction. Across radically different social and political regimes from Czarist Russia to Liberal Manchester, impoverished and marginal groups such as newly-arrived Asiatic Sarts at Tashkent or impoverished Irish Catholic immigrants in English cities formed crowds as large as 10,000 to destroy hospitals and attack health workers accused of poisoning and concocting a new disease to cull populations of the poor. These riots did not end with cholera’s first major European tour of the 1830s, when the disease was new and mysterious. In Italy, they persisted to the sixth cholera wave in 1910-11, long after its pathogenic agent and preventive measures had been discovered.

Smallpox was the disease par excellence of hate in the United States, and its social toxins burst forth with epidemics from the 1880s to the second decade of the twentieth century, well after this disease had scored its highest moralities and at the very moment of the laboratory revolution’s sprint in medical breakthroughs. Again, suspicion and hate spread along class lines, but now hate’s dance switched partners.

Cholera was not the only disease to spawn hate and violence into the 20th century. Smallpox was the disease par excellence of hate in the United States, and its social toxins burst forth with epidemics from the 1880s to the second decade of the twentieth century, well after this disease had scored its highest moralities and at the very moment of the laboratory revolution’s sprint in medical breakthroughs. Again, suspicion and hate spread along class lines, but now hate’s dance switched partners. Property holders from farmers to merchants comprised ‘the mobs’, while the victims were among the marginal—‘tramps’, ‘negroes’, Bohemians, and the ‘Chinese’.

Certainly, not all epidemics of modernity divided populations. The deadliest of pandemics in US history, yellow fever, in cities such as Philadelphia in 1793, New Orleans in 1853 and Memphis in 1878-9, brought blacks and whites together in mutual support and respect and saw contributions and volunteers pour across the Mason-Dixon line, creating martyrs to the plague, eulogized in newspapers and commemorated in works of poetry, paintings, and sculpture. Moreover, despite its monumental mortalities, mysteriousness of symptoms, quickness of death, peculiar age structure of its victims, and extraordinary contagion, the Great Influenza of 1918-20 failed to ignite hatred of victims, attacks on health workers, or blame of ‘others’. Instead, massive waves of volunteers, especially women, risked their lives, eagerly crossing state and international borders and reaching across class and ethnic barriers. El Paso, October 1918, is a case in point. Against the rising tide of anti-Mexican sentiment, the growth of the Ku Klux Klan, and nationalist fervour brewed by the Great War, debutants, middle-class ladies along with those from the labouring classes delivered food, swept floors, cared for children, and nursed the dangerously ill in El Paso’s worst-hit Mexican neighbourhoods.

The rich tapestry of epidemics’ social side effects challenges the one-dimensional, trans-historical consensus. Why did Ebola recently provoke violence against clinics and health workers in West Africa? What characteristics of epidemic diseases are more likely to spark hatred and blame? Certainly, rates of lethality are far more important than rates of mortality. But a mix of other factors, such as disgust and the quickness of death, along with prevailing social and cultural conditions must be considered. But the diseases themselves also mattered: just as different diseases affect our bodies differently, so too they have affected differently our collective mentalities.

Featured image: ‘The Triumph of Death’. Painting by Pieter Brueghel the Elder, c.1562. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons .

The post Epidemics and the ‘other’ appeared first on OUPblog.

Hegemonic comeback in Mexico? The victory of López Obrador

On 1 July, Mexicans elected a new president. The results confirmed what the polls had been predicting for months: Andrés Manuel López Obrador, known as AMLO, won by a landslide of over 50% of the vote—more than 30 points over the second place candidate, Ricardo Anaya of the National Action Party (PAN). In addition, AMLO’s new political outfit, the Movement of National Regeneration, or MORENA, essentially a one-man party, obtained the majority of seats in the Congress. The reasons behind this outcome are clearly rooted in the unpopularity of President Enrique Peña Nieto, who dragged his Revolutionary Institutional Party (PRI) to its worst-ever electoral results. Under his administration (2012-2018), Mexicans became increasingly exasperated with the country’s insecurity, its sluggish economy, and the corruption scandals involving senior members of his party and even his own family. Angry and frustrated, voters turned to AMLO and his promises: more security, higher wages, zero corruption, and justice for all. He has even promised to turn Mexico into a “loving republic” by helping raise “good and happy women and men.”

The outcome of the election was not inevitable. Had the PAN and the PRI understood that this election became a plebiscite on AMLO, they could have struck an unholy alliance to unify the anti-AMLO vote. Unlikely for two antagonistic parties, but they would have stood a chance. Had their coalition won, today AMLO would be in La Chingada, his ranch in Tabasco where he said he would retire if he lost the election. MORENA would also eventually fizzle without its leader. But that is not what happened.

That Sunday’s presidential election was the fourth organized by the National Electoral Institute (INE) since becoming completely independent from the executive branch in 1996. Late that evening, its president, Lorenzo Córdova Vianello, announced the winner and the overall official results. It was a remarkable twist of fate: AMLO has been a fierce critic of the INE. To this day, he does not acknowledge the electoral defeats he suffered in the presidential elections of 2006 and 2012, and has never backed down from his accusations that the board members of the INE were bribed into supporting a different candidate. Some may attribute this to simple demagoguery, but AMLO’s thinking is more complex than that. For him, the concept of democracy is not based on the simple act of voting, but on the broader and more revolutionary notion of a general will. From this perspective, his defeats were not caused by the caprices of the electorate, but by the malfeasance of his adversaries—abetted by the acquiescence of the INE. In 2006, he accused its board members of allowing ballot-stuffing and engaging in cyber fraud in favour of the PAN, and in 2012 of turning a blind eye to what he describe as a massive vote-buying operation by the PRI. On both occasions, he bullied and publicly vilified the INE for months, calling the board members “thieves” and “high traitors.”

Image credit: Andrés Manuel López Obrador being proclaimed “legitimate president” of Mexico by Hseldon10. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: Andrés Manuel López Obrador being proclaimed “legitimate president” of Mexico by Hseldon10. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.What relationship will AMLO establish with the INE now that he fulfilled his long ambition of becoming president? The question is of utmost importance for the survival of democracy in Mexico. He will likely disappoint on the multiple and almost impossible promises he made, if that happens, voters will seek other alternatives. At that moment, and given his previous record, he might attempt to undermine the autonomy of the INE, openly or behind the scenes, to tilt the electoral field in favour of his party. This is by no means a far-fetched scenario: MORENA controls the Congress, and president AMLO will have no trouble unifying the parties on the left along with left-leaning sectors of the PRI around him. A coalition of that breadth amounts to two-thirds of Congress, the necessary threshold to appoint INE board members. At that point, MORENA will be an inch away of becoming a new hegemonic party, and AMLO the unopposed leader of Mexico.

If that comes to pass, Mexico would have come full circle back into a hegemonic party system akin to that which existed under the PRI in the 20th century. The decades of democracy that followed the granting of complete autonomy to the INE in 1996 will come to a close, and a new competitive authoritarian regime—to use the expression coined by Levitsky and Way—will emerge. If that comes to pass, AMLO will surely have fulfilled his promise to transform Mexico.

Featured image credit: Mexican flag by danielforsytheg. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Hegemonic comeback in Mexico? The victory of López Obrador appeared first on OUPblog.

Making sense of President Trump’s trade policy

Trade policy was a cornerstone of US President Donald Trump’s campaigns, both in the primary and general, and has often been a centerpiece of his agenda since in office. Trade policy is once again at the forefront with the recently concluded G-7 summit, largely revolving around the President’s threatened steel tariffs on Canada and the EU which followed recent negotiations with China over a possible trade war. The President himself has been talking and tweeting about trade a lot recently.

Despite all the attention Trump has paid to trade and observers have paid to his policies and statements, we still only poorly understand that policy and we sometimes completely misunderstand it. Most importantly, we sometimes mistakenly view his trade policy as an ideological aberration. During the campaigns, it was common to see Trump’s trade policy compared to Senator Bernie Sanders’, and even used to claim Trump was running to opponent Hillary Clinton’s left. During his presidency, Trump’s trade policies have often drawn support from unlikely sources usually associated with the left.

This misunderstanding derives from two related mistakes. First, trade policy preferences are arrayed along a single dimension from support for free trade to support for protection. Second, this dimension is believed to be correlated with the standard left-right dimension such that protectionists are viewed as further to the left than free traders. However, trade has always divided both the right and left in the US (and often elsewhere), and trade policy has always been more complicated than merely being a debate between free traders and protectionists.

While it is true that Democrats have been, on average, more protectionist than Republicans since the 1950s, there have always been supporters of free trade among Democrats and opponents of trade among Republicans. To see the former, we only need look at Democratic presidents over that time span, each of whom championed the expansion of trade such as Bill Clinton signing NAFTA and Barack Obama negotiating the TPP. While the left wing of the Democrats often opposed trade, moderates tended to be more supportive. Most Republicans have been free traders over this same period, but notable exceptions, usually on the far right, have existed even before Trump such as Pat Buchanan.

That left-wing Democrats and right-wing Republicans have both often been the most opposed to trade should have been a clue that trade policy is not simply a single ideological dimension from right to left. In fact, it’s not a single dimension at all. Rather, opinions on trade are arrayed along the political spectrum. Other dimensions also exist, such as a security dimension and on a fair trade dimension. At one end of the fair trade dimension are people who support limits on trade for ethical reasons, namely that they worry about the effects of trade on labor rights and the environment abroad. While we normally think of labels on coffee when we think of this type of fair trade, the concept also includes such policies as bans on imports made with child labor or opposition to free trade agreements (FTAs) with countries with poor standards.

…opinions on trade are arrayed along the political spectrum.

Policymakers and the public can exist anywhere on each of these dimensions and their placement on one dimension does not determine their placement on the other. If we assume that people either support or oppose each dimension, this leads us to four policy orientations. Free traders oppose all limits to trade, whether for protectionist or fair trade reasons. Fair traders support limits only to protect labor rights and the environment abroad. Pure protectionists support limits only to protect jobs and/or the domestic economy. Anti-traders support all limits to trade.

Free traders tend to be wealthier, more educated, and more conservative while anti-traders tend to be poorer, less educated, and more liberal. This makes sense, as wealthier individuals with more job skills tend to benefit from trade, while poorer individuals with fewer skills tend to be hurt by it. Pure protectionists are also poorer and less educated but tend to be conservative, as they are not concerned by environmental and labor conditions. Fair traders, on the other hand, tend to be richer and more educated, thus oftentimes personally benefiting from trade, but also tend to be liberal and, thus, more likely to be interested in environmental and labor rights issues.

This helps us to understand Trump’s trade policy. Although much of Trump’s political support came from wealthier individuals who traditionally support Republicans (and free trade), an important constituency, especially in the primaries, were white working class voters, who often opposed trade for reasons of economic nationalism as well as self-interested concerns about their jobs. Trump appealed to these constituents in ways his primary competitors within the Republican Party did not because he himself holds these economic nationalist positions as illustrated by his campaign slogans “Make America Great Again” and “America First.”

This nationalist perspective distinguishes Trump from left wing critics of trade, like Sanders. Both expressed concerns about jobs in the US, but while Trump’s exclusive focus was on the domestic effects of trade, Sanders also expressed concern about conditions abroad. Despite the superficial similarities between their positions, the multidimensional approach helps us realize the major differences between them. The multidimensional approach also helps us to distinguish the Democratic presidents who supported FTAs—but who fought to include labor and environmental side agreements in them—from Republican leaders who usually opposed these side agreements while supporting the underlying FTA.

By looking at trade from a multidimensional perspective, we can better understand why President Trump has taken the trade positions he has and where those policies fit on the ideological spectrum. It also makes clear that trade policy is more complicated politically than often imagined, since we can’t just talk about free traders vs. protectionists, but must also consider fair traders—who are neither—and different types of protectionists.

Featured image credit: President Trump USA America Flag by Geralt. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Making sense of President Trump’s trade policy appeared first on OUPblog.

Giving young people a voice: a follow-up on El Sistema USA programs

“Music is my life. I will never stop playing cello,” says Vanessa Johnson, one of the young people whose early experiences with music are featured in the book The Music Parents’ Survival Guide (2014). Since more than four years have passed since it went to press, we are checking in with some youngsters to see how they are doing, focusing on those who participated in free after-school programs inspired by El Sistema, Venezuela’s music-education system which emphasizes ensemble playing right from the start.

In the Music Parents’ book, a photo shows Vanessa as a second grader finishing her first year in Cleveland’s El Sistema@Rainey program. She started on violin, then switched to cello, and takes private lessons now in addition to El Sistema classes. An eighth grader, she’ll age out of the program next year, but notes, “I’ll volunteer there once a week to teach younger kids.” The high school she’ll attend doesn’t have an orchestra, so she is auditioning for a youth orchestra to keep cello in her life. She feels the program helped her with school work. “Music is math. It has a lot of fractions. That helps me deal with fractions and everything else. But the best thing about music is it’s everywhere. When you walk down the street, you hear music, not actual music, but you hear your surroundings making music. I have thought about writing music. I’m good at improvising.”

Asia Palmer is also good at improvising, something this flutist has been doing in improvisational composition workshops offered by OrchKids, an El Sistema-inspired program in Baltimore. Asia’s mother, Lynette Fields, spoke in the Music Parents’ book about Asia and her brothers’ participation in this program back when they were in elementary school. Now in its tenth year, OrchKids has expanded beyond the early grades to keep older students involved, such as Asia and her twin brother, Andre, a percussionist, who have been with the program since it started. High schoolers now, they still take part in OrchKids workshops and ensembles, but have also won scholarships to study at Peabody Preparatory and at Interlochen Music Camp. “OrchKids opened doors for me,” says Asia. “It helped me get into Baltimore School for the Arts. If not for OrchKids, I would probably listen to one or two genres. My playlist is all over the place—Beyoncé, Cold Play, Brahms. I like to create my own music, a mixture of pop, funk, and jazz. Music helped with schoolwork, too, helps me concentrate.” As she told a New York Times reporter, “The program has given me a voice. I feel like I can be whatever, do whatever—strive.”

El Sistema children showed gains in what the study calls “growth mindset. . . the belief that one’s basic qualities—such as intelligence or musical ability—are due to one’s actions and efforts rather than to a fixed trait or talent.”

Their self-confidence aligns with results of two recent studies of El Sistema-inspired programs. A 2015-2017 Wolf Brown study of third-to-fifth graders in 12 El Sistema USA programs found marked differences between those youngsters and a group from the same grades, classrooms, and schools who weren’t in the music programs. El Sistema children showed gains in what the study calls “growth mindset. . . the belief that one’s basic qualities—such as intelligence or musical ability—are due to one’s actions and efforts rather than to a fixed trait or talent.” Growth mindset is thought to help with school success. The study also found that the El Sistema boys had higher rates of cooperation and perseverance than non-El Sistema boys. A study of a Los Angeles El Sistema program—YOLA (Youth Orchestra of LA)—found that YOLA students showed an increase in believing that “making mistakes—and working through them—is how one eventually succeeds,” another helpful mindset for academic success.

El Sistema USA has also made progress in the last four years. It started in 2009 as a loose alliance of El Sistema-inspired programs, but in 2016 became more organized with 501(c)3 nonprofit status and an official headquarters at Duke University, whose researchers helped the group define its core values, develop a membership process, and a list of new initiatives to pursue. With 85 member programs in nearly every state, El Sistema USA is introducing new training support for its teachers and is partnering with other music organizations to provide opportunities for older students who age out of the elementary school-focused after-school programs. “We are heavily represented in urban America now. I would like to see more representation in rural parts of the country,” says Katie Wyatt, El Sistema USA’s executive director. “Our next research question with Duke is to look at the impact of El Sistema programs on parents.” OrchKids has had a big impact on Asia’s mother, who works as a site coordinator at one of the seven schools that offer OrchKids programs. She has also learned to play recorder, one of the first instruments OrchKids students play. “I’m learning along with the kids,” says Ms. Fields.

Featured image credit: Street music by Vincent Anderlucci. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Giving young people a voice: a follow-up on El Sistema USA programs appeared first on OUPblog.

July 30, 2018

From Galileo’s trajectory to Rayleigh’s harp

A span of nearly 300 years separates Galileo Galilei from Lord Rayleigh—Galileo groping in the dark to perform the earliest quantitative explorations of motion, Lord Rayleigh identifying the key gaps of knowledge at the turn into the 20th century and using his home laboratory to fill them in. But the two scientists are connected by a continuous thread. Three centuries after Galileo discovered the parabolic trajectory, Rayleigh wrote down a fundamentally new equation of motion describing autonomous oscillators that would dominate the field of control theory in the 20th century and ultimately lead to the rise of chaos theory. The equation’s solution defines a single point that traces out a single continuous curve that arcs through a high-dimensional and abstract space known as phase space. This arc is the distant descendant of Galileo’s parabolic trajectory.

The concept of the system trajectory pervades modern science. From genetic drift to ideal gases to photons orbiting black holes, these motions admit the description of a single point, defining the unique state of a system, moving along a continuous curve in phase space. The complex world we live in is composed of an infinite set of interlinked system trajectories, interwoven into a multidimensional tapestry. Drawn from this universal backdrop, the same concept that Galileo discovered for a rock thrown from a cliff helped Lord Rayleigh to explain the unearthly behavior of the Aeolian harp.

The Aeolian harp is a stringed musical instrument played by the wind. It was named in antiquity for Aeolus, the keeper of the wind. It has strings of differing gauge and tension stretched lengthwise along a sounding board and tuned to create harmonics. When hung in a confined opening, such as a window or a narrow passageway, the channeled wind causes the strings of the harp to vibrate in resonant sympathy, producing a pleasing ethereal sound.

An Aeolian Harp. Image credit: ‘wind-harp-wind-masonry-substantiate-101464’ by Jostar. CC0 1.0 via Pixabay.

An Aeolian Harp. Image credit: ‘wind-harp-wind-masonry-substantiate-101464’ by Jostar. CC0 1.0 via Pixabay.John Strutt, the third Baron Rayleigh, was fascinated by sound and acoustics. Even on his honeymoon, boating up the Nile in Egypt, he spent much of his time writing his famous treatise The Theory of Sound, published in two volumes in 1877 and 1878, that stand today as a classic in the field. He returned to the physics of sound numerous times during his prolific career. For instance, Rayleigh was fascinated by systems that vibrated with regularity, like violin strings, clarinet reeds, finger glasses, flutes, and organ pipes, and he was particular entranced by the Aeolian harp. In early 1915, Rayleigh tackled the question of how a constant wind can produce a nonconstant dynamical motion. Based on his work on instabilities (for instance the eponymously named Rayleigh-Benard instability) he explained how a vibrating string sheds vortices of air that react back on the string to sustain its vibration.

The Aeolian harp is an example of an oscillator with a steady drive, yet Rayleigh understood that broader classes of sustained oscillations were possible that might be more ubiquitous and more applicable. In a short article for the Philosophical Magazine of London in 1883, titled On Maintained Oscillations, Rayleigh took the equation of a simple driven harmonic oscillator and added a cubic force term. The cubic force limits the growth of the solution to a steady-state oscillation, known as a limit cycle, that oscillates persistently with constant amplitude and frequency. Nearly 40 years later, the Dutch radio engineer Balthazar van der Pol discovered just such a limit cycle oscillation supported by the space-charge of triode oscillator vacuum tubes. Since then the same equations discovered by Rayleigh and van der Pol have proliferated across broad fields of complex systems. By the middle of the 20th century, autonomous oscillations had become the standard workhorses of control theory. In a nonlinear world, van der Pol’s nonlinear oscillator replaces the simple harmonic oscillator as the fundamental element of dynamical systems. Examples include magnetrons for radar, wheel shimmy of landing gear, and propeller vibrations on aircraft, as well as violin strings and clarinet reeds. The neurons of mind and motion are limit cycle oscillators, as are the pacemaker cells of the heart that beat with confidence a billion times in a lifetime.

Figure: ‘The phase-space portrait for van der Pol’s oscillator’, redrawn with permission from D. Nolte, Introduction to Modern Dynamics (Oxford University Press, 2015).

Figure: ‘The phase-space portrait for van der Pol’s oscillator’, redrawn with permission from D. Nolte, Introduction to Modern Dynamics (Oxford University Press, 2015).Featured image credit: ‘Beeld David met harp van het orgel – Katwijk aan Zee – 20124285 – RCE’ by Schollen, A.H.C. (Fotograaf). CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post From Galileo’s trajectory to Rayleigh’s harp appeared first on OUPblog.

Which Brontë sister said it? [quiz]

Emily Brontë, born 200 years ago on 30 July 1818, would become part of one of the most important literary trinities alongside her sisters, Charlotte and Anne. Emily’s only novel, Wuthering Heights, polarised contemporary critics and defied Victorian convention by depicting characters from “low and rustic life.” Jane Eyre, written by the eldest Brontë sister, Charlotte, was initially condemned as being “pre-eminently an anti-Christian composition,” however, the text caught the attention of readers and the fusion between romance and realism is hailed as Charlotte’s major contribution to the form of the novel. The youngest Brontë sibling Anne’s novel Agnes Grey is viewed as an effective exposure of the threat to woman’s integrity and independence posed by a corrupt and materialistic society. At the time, though praised for its minute observation, the novel was criticized for its concern with the eccentric and unpleasant.

Each Brontë sister has contributed some of the greatest works in literary history. Their words have influenced writers and readers over many generations and have offered meditations on love, beauty, and self-determination—but can you guess which Brontë sister said what?

Featured image credit: Old Books by jarmoluk. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Which Brontë sister said it? [quiz] appeared first on OUPblog.

Wars of national liberation: The story of one unusual rule II

In the first part of this post, I discussed the chequered history of Article 1(4) of Additional Protocol I to the Geneva Conventions. This provision has elevated so-called “wars of national liberation” to the level of inter-state armed conflicts as far as international humanitarian law (IHL) is concerned—albeit only for the parties to the Protocol. The rule was so controversial in the 1970s that it nearly prevented the adoption of the Protocol itself, but then it paradoxically languished for decades without practical application. Even so, was it really destined to become a dead letter, as some have argued?

This is a good moment to mention the sister clause to Article 1(4), namely Article 96(3) of the same Protocol. This latter provision grants the non-state party to a war of national liberation (that is, a “national liberation movement”) the right to issue a declaration by which that party undertakes to apply the Geneva Conventions and the Protocol in relation to the conflict in which it is involved. If successfully made, the legal effect of such a declaration is to bring those instruments into force for the said national liberation movement. Afterwards, there would be little doubt that the conflict in question qualified as one to which Article 1(4) applied, and therefore it could be accurately described as an internationalized armed conflict.

However, in order for any such declaration to be successfully made, it would have to be accepted by the depositary of the Protocol. As for nearly 80 other international treaties, this role is performed by Switzerland. Historically, communications that were either expressly styled as Article 96(3) declarations or contained formulations similar to those used by the provision have in fact been made on multiple occasions. These have included declarations issued by the African National Congress in 1980, the Palestinian Liberation Organization in 1989, and the National Democratic Front of the Philippines in 1996. However, until very recently, no such declaration had been accepted by the depositary.

New lease of life for the moribund rule

In June 2015, Switzerland surprised a few of those paying attention by issuing a brief notice, in which it stated that a unilateral declaration deposited by the Polisario Front just a few days prior “ha[d] … the effects mentioned in Article 96, paragraph 3, of Protocol I.” Perplexingly, it did not provide any further legal reasoning to justify this evaluation. I was more than intrigued: given the language of Article 96(3), accepting the declaration seemed to mean that Switzerland, in its capacity as the depositary of the Protocol, considered that the situation in Western Sahara qualified as a “war of national liberation” in the sense of Article 1(4). This would have a dramatic impact: an entire, heretofore theoretical, modality of internationalization would suddenly come to life.

I decided to submit a freedom of information request to the Swiss authorities in order to better understand the reasons behind the acceptance. A few weeks later, I received a copy of an internal memorandum with detailed analysis in French. In brief, the document confirmed that the conflict between the Kingdom of Morocco and the Polisario Front had fulfilled the criteria of Article 1(4) of the Protocol. The reasons given for that assessment were that the people of Western Sahara possessed the right to self-determination; that the Polisario Front as a matter of fact represented this people; and that in the conflict, Morocco acted as an “alien occupying power.”

…this example shows that once a legal provision is on the books, it takes on a life of its own.

Importantly, unlike other past adversaries of national liberation movements around the world, Morocco is a contracting party to the Protocol, having ratified it in June 2011. Therefore, the memorandum concluded, the depositary had no choice but to accept the declaration and notify it to all contracting parties of the Conventions and the Protocol. For good measure, it even confirmed that this was an unprecedented decision: the document expressly stated that “[t]his is the first time that [the depositary] received such a declaration meeting all these criteria”. The document thus put some meat on the bare bones of the official notice, making it better understandable for researchers and practitioners in the field.

Instead of a conclusion

So where does that leave us? This brief exploration allows for two main observations, a narrower and a broader one. The narrow observation is that there is now a solid case for qualifying the situation in Western Sahara as an armed conflict internationalized by way of Article 1(4) of the Protocol. In other words, the controversial rule originally drafted in the mid-1970s has suddenly been revived four decades later, thus belatedly confirming the practical viability of a specific type of conflict internationalization.

In addition, there is also a broader observation to be made. To paraphrase the legendary Mark Twain’s (mis)quote, we can now see that the reports of the death of Article 1(4) have been at least slightly exaggerated. To put it differently, this example shows that once a legal provision is on the books, it takes on a life of its own. Even if its content may at one point start to look archaic or obsolete, until it is repealed, its capacity to apply to novel circumstances may come as a surprise, on occasion even to its own authors.

Featured image credit: Flags by 495756. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Wars of national liberation: The story of one unusual rule II appeared first on OUPblog.

July 29, 2018

Donald Trump, Kim Jong Un, and North Korean human rights

US President Donald Trump traveled to Singapore to negotiate urgent nuclear matters, and not to discuss North Korean violations of basic human rights. Nonetheless, any such willful US indifference to these violations in another country, especially when they are as stark and egregious as they are in North Korea, represents a sorely grievous disregard for America’s vital obligations under international law. Moreover, because these core obligations are an integral and incorporated portion of US law, this President’s open indifference to North Korean crimes is also, arguably, a violation of the laws of the United States.

Under various mutually reinforcing norms of both national and international law – norms that are known formally as “peremptory” or “jus cogens” rules because they can permit “no derogation” —an American president has no right to ignore North Korean crimes against human rights because “there are other bad guys out there.” Jurisprudentially, at least, such an evident presidential non sequitur is neither a proper nor exculpatory “plea.” Additionally, the US Declaration of Independence codifies a social contract that sets human rights infringement limits on the power of any government. In essence, because justice, which is based on “natural law,” binds all human society, those specific rights articulated by the Declaration cannot be reserved exclusively to Americans.

Instead, these rights necessarily extend to all human societies, and, following the authoritative Nuremberg Tribunal judgments of 1945-46, can no longer be considered merely issues of “domestic jurisdiction.”

Incontestably, this is the law. For Mr. Trump to suggest otherwise would be both illogical and self-contradictory, as it would nullify the immutable and universal “law of nature” from which the Declaration — and indeed, the entire United States Constitutional Republic — derives. To be sure, very few Americans are even remotely aware of this history or corollary jurisprudence, but the facts and the law still remain valid and binding. Speaking of history, the actual conveyance of natural law thinking into American Constitutional theory was largely the work of John Locke’s classic Second Treatise on Civil Government.

Today, for Trump’s benefit, it is worth noting that the well-known American duty to revolt whenever governments commit “a long train of abuses and usurpations” flows directly from John Locke’s core idea that civil authority can never legitimately impair any person’s natural rights. Derivatively, Mr. Trump’s properly criticized current policy of separating parents and children among refugees to the United States fleeing insufferable regimes elsewhere is prima facie a violation of international law and its variously codified US incorporations. In this connection, it also goes without saying that any such US violations seriously impair our national interests and our ideals at the same time.

Human rights in other countries which an American president is currently negotiating with are always an obligatory concern under certain intersecting expectations of international and national law.

Accepting the aptly famous legal maxim – jus ex injuria non oritur, “rights do not arise from wrongs” — Mr. Trump should at least grasp the fundamental traditions and laws of his own country, and ought to finally acknowledge them as the only permissible standard for further global interactions.

The basic principles of the international law of human rights are already incorporated into statutes of the United States. Accordingly and unequivocally, the US Department of State is required to enforce the human rights provisions mandated by sections 116 (d) and 502B (b) of the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961, as amended. The express purpose of these provisions is to better ensure US support for human rights across the world.

Founded upon an irrational fear of both past and future, the Trump administration’s unhidden indifference to indispensable human rights (both internationally and nationally) is already generating a fearful kind of national aloneness, an anti-intellectual orientation that is inherently flawed and openly self-defeating. For the United States, and for the world in general, meaningful survival and progress now mandate renunciation of the long-discredited principle, “Everyone for himself.” Now, to be sure, it is no longer even possible to cite as “realistic” a national foreign policy that is at explicit cross-purposes with worldwide dignity and human well-being.

Gabriela Mistral, the Chilean poet who won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1945, once wrote that crimes against human rights carry within themselves “a moral judgment over an evil in which every feeling man and woman concurs.” At this particularly perilous time in our US presidential history, a last real hope for preventing such evil must lie in enhanced compliance with the complementary imperatives of America’s basic traditions and its relevant laws. With such compliance, and not with the plainly conspicuous degradations of “America First,” this country could still replace US President Donald Trump’s patently unlawful disregard for compassionate and purposeful human interactions with a desperately-needed ethos of national and planetary renewal.

Whether or not they represent a conscious US foreign policy objective, human rights in other countries which an American president is currently negotiating with are always an obligatory concern under certain intersecting expectations of international and national law. Accordingly, President Donald Trump’s unhidden disregard for truly basic human rights in North Korea represents a grievous and concurrent violation of both systems of pertinent jurisprudence. To avoid similar violations in the future, Mr. Trump should pay much closer attention to America’s philosophic origins and to strongly reinforcing norms of the unalterable law of nations.

Featured image credit: Kim and Trump shaking hands at the red carpet during the DPRK–USA Singapore Summit by Shealah Craighead. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Donald Trump, Kim Jong Un, and North Korean human rights appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers