Oxford University Press's Blog, page 235

August 13, 2018

The Geneva Conventions and the minimum standards of humanity

On the occasion of World Humanitarian Day, it seems appropriate to look to the basic principles of humanitarian law, which show what is always unacceptable. Prior to 1949, there was little international humanitarian law applicable to non-international armed conflicts, although such conflicts were becoming increasingly prevalent and overtaking their international counterparts. As such, after difficult negotiations, it was decided to try to distil the essence of the Geneva Conventions into a single provision.

This was common Article 3 of the Geneva Conventions, that deserves to be cited in detail:

… each Party to the conflict shall be bound to apply, as a minimum, the following provisions:

(1) Persons taking no active part in the hostilities, including members of armed forces who have laid down their arms and those placed ‘ hors de combat ‘ by sickness, wounds, detention, or any other cause, shall in all circumstances be treated humanely, without any adverse distinction founded on race, colour, religion or faith, sex, birth or wealth, or any other similar criteria.

To this end, the following acts are and shall remain prohibited at any time and in any place whatsoever with respect to the above-mentioned persons:

(a) violence to life and person, in particular murder of all kinds, mutilation, cruel treatment and torture;

(b) taking of hostages;

(c) outrages upon personal dignity, in particular humiliating and degrading treatment;

(d) the passing of sentences and the carrying out of executions without previous judgment pronounced by a regularly constituted court, affording all the judicial guarantees which are recognized as indispensable by civilized peoples.

(2) The wounded and sick shall be collected and cared for.

An impartial humanitarian body, such as the International Committee of the Red Cross, may offer its services to the Parties to the conflict.

Common Article 3 may be just shy of 70 years old, but it is by no means of retirement age. It may not read with Byronic lyricism, but it has a quality of its own. As a teacher of International Humanitarian Law, I often set the task of summing up the hundreds of provisions of the Geneva Conventions in a single article. Despite having many talented people trying to do so, no one has succeeded in improving on common Article 3.

Common Article 3 may be just shy of 70 years old, but it is by no means of retirement age.

It is true that there are issues that it misses. For example, there is nothing in the Article that deals with the prohibition of certain weapons, such as chemical or biological ones, or other aspects of what is sometimes known as “Hague” law. However, it reflects what is considered a base-line level of protection that is always applicable. It is reflective of customary law and reflects what the International Court of Justice has described as the “elementary considerations of humanity.”

It is true, though, that what is considered humane or not is not always simple to determine. When common Article 3 was drafted, it was rather thought that the answer would be obvious. That was perhaps a little optimistic, as the evaluative nature of the concept of humane treatment is one that has been the subject of difficult discussions, some of which have been engaged on an unfortunately self-interested basis.

That said, as the plurality opinion in the US Supreme Court in the Hamdan v Rumsfeld case showed, Article 75 of Additional Protocol I to the 1949 Geneva Conventions—which, despite being, as a matter of treaty law, only applicable to international armed conflicts—can also be a useful measure by which to interpret common Article 3. Practitioners may wish to take with them, if nothing else, common Article 3 and Article 75 when they are putting the law into practice. They are the lodestar from which humanitarian law needs to be applied.

In a troubled world, these provisions reflect a level of protection that is owed to everyone, no matter their race, religion, gender, or any other grounds. This was, rightly, the intention of the drafters of the Conventions, and they set them down in lapidary terms. Although practice has not always lived up to these provisions, this is more a failure of political will than one of drafting failures.

Let us hope that the humanitarian ideals encapsulated in the Geneva Conventions become more honoured, rather than in the breach, in the future. The matter is one which is in part of enforcement, by bodies such as the International Criminal Court, but, more importantly, an inculcation of those values by those involved in conflicts. It would be best if people go beyond them, but these standards are what can be expected of all, whoever, and wherever they are.

Featured image credit: Adventures at vadodara by Priyash Vasava. CC0 via Unsplash.

The post The Geneva Conventions and the minimum standards of humanity appeared first on OUPblog.

August 12, 2018

The vocation of youth

We all benefit when young people understand their strengths and talents and use these to make the world a better place through direct action, service, and leadership. We use the idea of vocation to describe this process of them coming to understand their strengths and talents and how these can be applied to address issues they care about in their community. Vocation captures the idea that young people live in a world that poses questions to them and their life is often the answer to these questions. In our own work with young people, we never met a young person who did not have a public issue that they cared about on a personal level. They all heard at least one question the world was asking of them.

Raising young people’s awareness about what issues matter to them and the strengths and talents they have facilitates learning about their vocation: how they can “make a difference” In our experience, seeing young people as having a vocation challenges common youth programs, services, and policies, which understand young people as deficient and not ready to take on real issues that matter to them. Youth programs, services, and policies often work to create oases for young people to protect them from what is going on in their neighborhoods and often limit what information they receive as well as what questions they can ask.

Having access to safe spaces, this year’s international youth day theme, facilitates and supports young people learning about their strengths and how they can make a difference on issues they personally care about—their vocation. The access to safe spaces correlates with positive identity development, political efficacy, wellbeing, and empowerment. The idea of vocation strengthens our understanding of these spaces by aligning them to values of participation, inclusion, and creativity and practices the amplify youth voice, youth involvement in decision-making, and youth action. The idea of vocation also challenges the concept of safe space, reminding us that safety should not equate to limiting information or removing risk. Vocation provides a useful frame in designing and facilitation youth safe spaces.

The access to safe spaces correlates with positive identity development, political efficacy, wellbeing, and empowerment.

The Vocation of Youth

There is lack of invitation for young people to apply their strengths and talents to make a difference. Instead young people receive messages to wait, hold back, and focus on self-development, while simultaneously being told they are self-absorbed. To add to the inconsistences facing young communities, the world refers to the younger populations as the “next generation” or “the future”, while core systems don’t allow this next generation to have a say in what their future looks like. In these tumultuous times, safe spaces provide ballast and opportunity that young people may not find in broader society.

The danger is to take the metaphor of safe and safety too far. While opportunities for young people to discuss ideas that matter to them, work out ways of responding, and taking joint action on these are required, we have to be aware that too often these spaces can work to isolate and segregate young people from broader discussions and direct action. Safe spaces work best when they invite courage and acceptable risk, and create opportunity roles for young people. Those who have worked with young people in violent, marginalized, and excluded communities have substituted safe spaces for dignity, courageous, and/or challenging spaces. They make these revisions to illuminate the purpose of safe spaces. These are only short-term oasis from the troubling situations in society. When safe spaces become isolating and segregating spaces the world loses. We lose the strengths and talents young people possess that should be contributed now to creating a better world—to making a difference.

Featured image credit: Balcony by Devin Avery. CC0 via Unsplash.

The post The vocation of youth appeared first on OUPblog.

August 11, 2018

Seven myths about feigning

Defendants may feign psychiatric disorders to reduce their criminal responsibility. From its detection and prevalence, to its connections with psychopathy, this extract from Finding Truth in the Courtroom debunks seven common myths about feigning, and why people do it.

Myth One: Feigning Can Be Easily Detected Using a Clinical Interview

More than a century ago, German psychiatrists such as Falkenhorst (cited in Vyleta, 2007) believed that feigners could be detected by observing the way individuals move. Today, some mental health experts still adhere to that idea.

In a classic study, Rosenhan (1973) had eight individuals—Rosenhan himself, one psychology student, three psychologists, two physicians, and a housewife—admitted to psychiatric institutions. All of them claimed hearing voices during the intake procedure. Although they stopped complaining about hallucinations once admitted to the clinic, all of them were diagnosed with schizophrenia, were prescribed medications, and had to stay in the hospital for a considerable time. In 2004, Rosen and Phillips identified 12 studies in which normal people instructed to feign a condition were asked to visit a medical doctor. In all studies, physicians detected feigners at a very low rate, from 0% to 25%.

Myth Two: Feigning Is Rare

Clinicians who do not use symptom validity tests will often fail to detect feigning of mental illness. As a consequence, they will think that only in rare cases will individuals pretend to have a psychiatric disorder.

Just like the first misconception about feigning, this second myth also has old roots. Carl Gustav Jung wrote that, during his career, he spoke to thousands of people admitted to a psychiatric institution, and only 11 were feigners. German psychiatrist Többen also opined that feigning was rare. He studied files of patients admitted to the clinic where he was working, and reported that only two were pseudo-patients. Jung and Többen were not the only ones; many old German psychiatrists thought that feigning of mental illness did not occur.

To a large extent, this belief was motivated by the fear of labeling truly sick people as malingerers, a practice present in the pre-19th century history of psychiatry. This fear is still with us today, and might explain why, in a study of 227 patients who attended the emergency department of a general hospital, 13% of them were suspected of feigning, while in their medical records this was completely dropped.

Myth Three: People Are Unable to Feign Symptoms for a Prolonged Period of Time

Many case reports show that people are able to convincingly feign a disorder for a prolonged period of time.

For example, Alan Knight not only pretended to be paralyzed and suffering from epilepsy; every now and then he would slip into a coma. He was caught when a CCTV camera spotted he and his wife shopping: Alan Knight was maneuvering a full shopping cart—not exactly skills that can be observed in a person living in an almost vegetative state.

Many case reports show that people are able to convincingly feign a disorder for a prolonged period of time.

At the moment he was unmasked as a feigner, Knight had played the role of a paralyzed epileptic for two years.

There are more examples of long-term malingerers. One famous case is Rudolf Hess, the high ranking Nazi official who first was held in captivity in England and later had to stand trial in Nuremberg. From February 1941 through February 1945, Hess claimed episodes of memory loss for vital parts of the recent German history in which he had played such a decisive role.

Myth Four: Feigners Are Ill

Based on experiments that show that negative expectations may lead to decrements in performance on neuropsychological tests, it has been shown that if a clinician thinks a patient is severely ill, they will activate negative expectations in the patient’s mind, resulting in abnormal performance on symptom validity tests.

There is evidence for a performance-undermining effect of negative expectations, but the effect is rather small. Speculating about “unconsciously determined distortion” may lead to circular reasoning: Because a patient is ill, she or he will score in the abnormal range on a symptom validity test, and because of this abnormal score on a symptom validity test, the patient must be ill.

This circularity has been dubbed the psychopathology-is-superordinate fallacy—the belief that abnormal scores on symptom validity tests are both caused by psychopathology and prove psychopathology.

Myth Five: Mental Health Professionals Should Be Kind to Feigners

The idea that mental health professionals should be kind to feigners builds on the notion that feigners are ill.

Not confronting feigners with their behavior may contribute to symptom escalation, as feigners may come to believe their lies. Pseudo-patients know that exaggerating symptoms conflicts with their self-definition of being an honest person – just as smokers often tell themselves that their chain-smoking grandfather reached the age of 92, feigners in the care of sympathetic professionals will start to believe that they do have real complaints.

Myth Six: Feigners Are Psychopaths

The belief that feigners have psychopathic or antisocial traits is a special variant of the idea that feigners are ill, but it also alludes to the myth that feigning is rare.

Some high-profile cases seemed to confirm the close link between psychopathy and habitual feigning. A fine example is the story of Vincent Gigante, a mafia boss, who started to walk around the neighborhood dressed in his bathrobe and muttering in himself whenever he had to stand trial. Renowned experts testified that Gigante suffered from psychosis and vascular dementia, and PET scans were shown in court to bolster these claims. However, later, Gigante admitted that he faked his mental illness in order to avoid conviction.

Myth Seven: Feigners Are Not Faking Good

According to the bipolarity hypothesis, faking bad (fabricating or aggravating symptoms) and faking good (hiding symptoms) are two mutually exclusive categories. That is, people who feign are not expected to also engage in faking good. There is no solid evidence for this widespread idea; in the study mentioned above, the prisoners sample engaged in both feigning symptoms and faking good.

The temporal patterns of faking bad and good testify as to the situational origins of feigning. During the pre-trial phase, defendants may feign mental illness and cognitive impairments in an attempt to reduce their criminal responsibility. Once convicted, these same individuals may engage in faking good so as to acquire privileges.

Featured image credit: Hammer by succo. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Seven myths about feigning appeared first on OUPblog.

August 10, 2018

The ever-evolving US Supreme Court

Justice Byron R. White, who served on the Supreme Court for 31 years (1962-1993), once observed that every time a new justice joins the court, it’s a new court.

His observation may sound counter-intuitive: after all, a new justice joins eight incumbents. Can a single new member make such a difference? But consider the dynamics of an institution in which each of the nine members has an equal vote, and where no one can accomplish anything without persuading colleagues to go along – four other justices, in the case of crafting a majority opinion, and three others when it comes to adding new cases to the court’s docket. While most justices do choose to retire rather than take literally the Constitution’s promise of life tenure, they typically serve for decades. They get to know each other very well. Each departure and each new arrival up-ends established patterns and presents a shock to the system.

And certainly, a Supreme Court vacancy is a shock to the political system. In the afternoon of June 27, 2018, when Justice Anthony M. Kennedy announced his decision to retire, time in Washington, D.C. seemed to stand still, at least in the moments before the partisan contenders caught their collective breath and took to their battle stations in anticipation that President Trump would soon choose a nominee. Among the questions: would the Democrats try to pay back the Republicans for the Senate’s unprecedented stonewalling of President Obama’s last Supreme Court nominee, Merrick Garland? Would President Trump’s replacement for Justice Kennedy, a 30-year veteran who had long been the “swing justice” on a polarized court, finally bring about the conservative triumph that had proven elusive for a generation, despite the fact that during the last half-century, Republican presidents have succeeded in naming 13 Supreme Court justices while Democrats have appointed only four?

On July 9, President Trump nominated Judge Brett Kavanaugh of the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit. Judge Kavanaugh, long a familiar figure in Washington legal circles, was himself a law clerk to Justice Kennedy. Clearly, he knows the Supreme Court very well. Whether the American public will get to know him well depends in part on how probing senators are during his confirmation hearing, and on how forthcoming he chooses to be in answer to their questions. President Trump’s first Supreme Court nominee, Judge Neil Gorsuch, answered almost none of the senators’ questions. He was confirmed by a party-line vote of 54 to 45 to the seat President Obama had intended for Judge Garland. Only three Democrats joined all the Senate’s Republicans in voting for confirmation.

In the country’s history, there have been only 113 Supreme Court justices. Most of them have labored in obscurity. That includes the current incumbents: a recent survey showed that . Surveys over the years have shown that few people have a clear idea of how the Supreme Court works.

So as the country turns its attention, however fleetingly, to the Supreme Court, here are some often overlooked points to keep in mind.

The Supreme Court sets our legal agenda. One of the court’s most important but least understood functions is deciding what to decide. Unlike most appellate courts, which have to decide all the properly presented cases that reach them, the Supreme Court has nearly unfettered discretion to choose the cases it wants to decide. And in making those choices–roughly 70 cases out of the 7,000 or so that reach the court every term–the justices necessarily set the country’s legal agenda.

In the country’s history, there have been only 113 Supreme Court justices.

It takes the votes of four justices to grant a case for argument and decision. The most obvious reason for granting a case is what the court calls a “conflict in the circuits”–when two or more of the federal appellate courts, organized into 13 circuits, have disagreed on the meaning of a statute or the constitutionality of an official action, the justices feel an obligation to provide a uniform national rule.

But there are other reasons for granting a “petition for a writ of certiorari,” or “granting cert,” as the court calls the decision to accept a new case. One reason is that the case offers a group of justices the chance to move the law in the desired direction, to accomplish a particular agenda.

Yes, the Supreme Court justices respect precedent, but respect goes only so far. To the extent that Supreme Court nominees say anything at their confirmation hearings, they express respect for the body of precedent that they will inherit as new Supreme Court justices. The rule of adherence precedent, known by the Latin phrase stare decisis, meaning to stand by what has been decided, is indeed important because without it, every day would be a new day and every argument could be considered afresh. But as every Supreme Court nominee surely knows, and as the senators should, stare decisis “is not an inexorable command,” as the late Chief Justice Rehnquist put it in a 1989 decision.

Lower courts are bound by Supreme Court precedent, but the Supreme Court itself is free to change its mind with the vote of five justices.

Extreme polarization is the exception, not the norm. In the final decade of Justice Kennedy’s long tenure, it was common to hear references to the “Kennedy Court,” meaning that in many important cases, there were four votes on one side, four on the other, with Justice Kennedy in the position to determine the outcome. This happened so often (last term’s decision upholding President Trump’s Muslim entry ban being one example and the 2015 decision recognizing a constitutional right to same-sex marriage being another that we have come to think of the situation as normal.

But it’s a historical anomaly.

Certainly, the polarized court reflects the country’s polarization, including the politically charged confirmation process of recent years. As a result, the court finds itself in a delicate, even perilous situation. At what point does the public come to see the justices as simply politicians in robes? How can the court maintain the public’s trust? In Justice Byron White’s words, a new Supreme Court is about to be born. Its future, our future, is in its hands.

The post The ever-evolving US Supreme Court appeared first on OUPblog.

Animal of the month: 10 facts about lions

Lions have enchanted humans since early Antiquity, and were even represented in European cave paintings from 35,000 years ago. They are regularly the main characters in folklore and allegory, appearing everywhere from African folktales to the Bible. It is not hard to see why lions are so ubiquitously revered. Their fearsome yet stunning appearance, combined with their endearing hunting tactics and formidable roar, answers any questions as to why early societies named the lion ‘King of the Beasts’, and indeed explains why this name is still used today. Lions have pervaded a plethora of aspects of today’s society, regularly featuring in films and documentaries, appearing as statues, and having English pubs named after them.

We wanted to share some lesser-known facts about these well-known beasts, which, despite their constant appearances in popular culture, you may not have known about them.

1. Extended family

Lions belong to the felidae family, and are one of the five species of the genus panthera. The felidae family includes all extant and extinct cats, whose notable characteristics include large brains, powerful jaws, and skeletons specialized for leaping.

Their panthera family members are tigers, jaguars, leopards, and snow leopards. Lions share their habitat with leopards, although their diets differ enough for them to not cross paths very often.

2. Immediate family

Groups of lions, called prides, usually consist of large groups of adult females, cubs, and one or two adult males. Male lions stay in pairs for most of their lives, growing up together as cubs in a pride before leaving the pride to lead a nomadic lifestyle. In their lifetimes they range from pride to pride, breeding, living with their cubs, and protecting the pride from intruders. Sometimes, males will not have the chance to grow up with other male cubs, so must therefore become solitary nomads. Once they begin their nomadic lifestyle, they usually search for another solitary nomad, with whom they can pair up.

Picture credit: ‘Two brothers’ by Gary Whyte. Public Domain via Unsplash.

Picture credit: ‘Two brothers’ by Gary Whyte. Public Domain via Unsplash.3. What they eat

Lions eat large hoofed animals, such as gazelles, zebras, antelopes, wildebeest, giraffes, and wild hogs, and they will also eat the young of larger mammals, such as elephants and rhinos – if they can get past their parents. Lions seem to prefer eating zebras and wildebeest, although the former in particular can often prove very difficult to catch.

Lions have also been known the eat rodents, hares, small birds and reptiles. Lions living in the Kalahari Desert also regularly eat porcupines!

4. Where do lions come from?

Lions have been on quite a journey throughout their existence. Archaeological evidence has determined the widespread presence of lions in Europe and North America until around 10,000 years ago. Aristotle speaks of lions in Greece around 300 BCE, and those partaking in the Crusades frequently reported encounters with lions from the 1st century onwards CE. However, due to human expansion and hostility towards them, lions were slowly but surely wiped out from most of the world by the early 1900s. A small population of the Asiatic lion remains in the Gir Forest in India, but lions only otherwise live out of captivity in Africa.

5. Fission-fusion

Whilst most would assume that lions live together in their prides 24/7, this is not actually how they work. Lions are an example of a fission-fusion group dynamic – each lion may spend days or weeks living on its own or in a small subgroup. One reason for this is to take part in hunting their food. Lions, contrary to popular belief, do not always hunt in groups, only doing so when prey is particularly difficult to catch – such as when they are based in harsh environments, or if the animal is much larger than them.

6. Lions in the Bible and in Architecture

Lions are frequently mentioned in the Bible, and are often used as symbols of strength, fortitude, and courage. The character of the lion was altered slightly in the middle ages to include attributes such as magnanimity, watchfulness, and vigilance, using this vigilance to detect and defend against sin. It is for this reason that lions are often featured in Christian architecture, particularly in Italian churches.

Lions are also seen as a symbol of the Resurrection, as the Physiologus use them in an allegory for the event. In the book, the lion’s cub is born dead and remains dead for three days, before the father breathes on it and it receives life.

Image credit: ‘Parma, duomo, leoni’ by Palickap. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: ‘Parma, duomo, leoni’ by Palickap. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.7. Roaring

Although lions are often depicted as fearsome beasts standing boldly and roaring for no reason, lions actually have many reasons for belting out a roar. Lions can recognise each other’s roars like humans can recognise each other’s voices, and use them as a means of communication over long distances. Males often, for example, roar when they are patrolling their territory in order to reassure females that they are safe. Roaring is a truly excellent means of communication, as lion roars can be heard up to 8km away from the lion itself!

8. Lions + rain = success

Climate change has had an impact on lion populations, except, not in the way that you might expect. Studies have shown that climate change has led to increased rainfall in the Serengeti, during which wildebeest, on which lions feed, tend to stay within the forests of the savannah. This is, conveniently, where the lions are based, so prey is much easier to access. As a result, cubs have much more food, and are therefore likelier to survive into adulthood.

9. Threats to their home

On the other hand, while climate change may not be having too much of an adverse effect on lions, humans are still threatening lions’ survival. The booming agricultural businesses of Africa demand large expanses of land to be cleared and cultivated, which is inconsistent with the large territories required by lions to hunt in. The range of the Asian lion was reduced to a single reserve in less than a century, and a similar pattern may soon take place in Africa.

10. Three Lions

Lions have been featured as emblems in heraldry since the early 1100s. The arms of England feature three lions passant gardant, i.e. walking and showing full face. The first lion represents Rollo, Duke of Normandy, and the second that of Maine, which was added to Normandy. These were borne by William the Conqueror and his descendants. Henry II added the third lion to represent the duchy of Aquitaine, which came to him through his wife Eleanor.

You didn’t think we weren’t going to make a reference to the almighty 3 Lions by the Lightning Seeds, did you? Fun fact: the lyric ‘it’s coming home’ is a reference to the fact that the game we now know as association football was first codified in England.

Featured image credit: ‘Lion cubs on the Masai Mara’ by Christopher Michel. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Animal of the month: 10 facts about lions appeared first on OUPblog.

Celebrating the NHS at 70

On the 5th of July 2018, the National Health Service (NHS) celebrated its 70th anniversary. Aneurin Bevan, the Minister for Health, founded the NHS in 1948 with the aim of bringing together hospitals, doctors, nurses, dentists, pharmacists, and opticians under a single umbrella organisation for the first time. Bevan intended to provide good healthcare to all, which was on the whole free at the point of delivery. Throughout its 70 years, the National Health Service has impacted the lives of millions of people across Britain and provides vital services daily. To celebrate this, we asked our authors for their thoughts and experiences on working for the NHS, and what this institution personally means to them.

“Working for the NHS may well shorten my life (the pressures are real!), yet I am proud to work for an organisation and be part of a nation that chooses to treat its people equally when they are ill, regardless of their ability to pay. The NHS has stood the test of time and change and remains a uniquely powerful engine of social justice.”

– Dr Andrew Baldwin, General Practitioner, East Sussex. Co-author of the Oxford Handbook of Clinical Specialties (OUP, 2016).

“During my many years working within the NHS, I have seen a wealth of innovations that have enabled individuals receiving care to be empowered and informed whilst nurses and other health professionals have advanced their practice to benefit the services. Such a precious institution can only be sustainable if each and every one of us working with the NHS is appropriately supported, but also accepts and thrives on constant change to allow for future demands.”

– Susan Oliver, RN, MSc, FRCN, OBE, Independent Nurse Consultant Rheumatology, Fellow of the Royal College of Nursing, Member of the British Society for Rheumatology, Honorary Member of European League Against Rheumatism. Editor of the Oxford Handbook of Musculoskeletal Nursing (OUP, 2009).

“It is only when you experience healthcare abroad that you come to fully realise how truly wonderful our NHS is. We had a foreign patient recently on Intensive Care who kept politely refusing nursing care and meals until we eventually realised it was because she thought she couldn’t afford these ‘extra’ services…!”

– Dr Nina Hjelde, Anaesthetic Registrar, Manchester Foundation Trust. Co-author of the Oxford Handbook of Clinical Specialties (OUP, 2016).

“My career in the NHS spans the years 1972-1995, and my roles were Student Nurse, Registered Nurse, Student Midwife, Registered Midwife, and then finally Midwife Teacher, after which I became a university lecturer. There have been so many changes over that time, but I must say I will be forever grateful to my dedicated colleagues (and students) who have all taught me so much while their unstinting efforts contributed to provide the best possible care to clients and patients.”

– Janet Medforth, Retired, Senior Lecturer, Sheffield Hallam University. Editor of the Oxford Handbook of Midwifery (OUP, 2017).

“To have had an opportunity to be part of this great institution has been a real privilege. I spent many years as a cardiac nurse working in London and now I’m educating the nurses of tomorrow. Long may the NHS continue.”

– Kate Olsen, Visiting Lecturer in Adult Nursing and Cardiac Nurse City, University of London. Editor of the Oxford Handbook of Cardiac Nursing (OUP, 2014).

We have also collated a reading list of open access resources which look at how, during its 70 years, the NHS has been at the heart of major medical milestones.

The changing face of the English National Health Service: new providers, markets and morality by Lucy Frith from the British Medical Bulletin. This article looks at the introduction of market mechanisms in the NHS, and what the effects of this are and if markets change the NHS beyond what Bevan might have imagined in 1948?

Implementing electronic records in NHS secondary care organizations in England: policy and progress since 1998 by Arabella Clarke, Ian Watt, Laura Sheard, John Wright, and Joy Adamson from the British Medical Bulletin. Whilst a number of different policies have aimed to introduce electronic records into the NHS secondary care organizations in England over recent years., there has been little formal attempt to explore the overall impact of these policies and how they have developed and progressed over time.

New NHS treatments: a real breakthrough for breast cancer? by Kiashini Sriharan. In November 2017, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) approved two new drugs for treatment of breast cancer for use on the NHS, palbociclib and ribociclib and which was deemed ‘ground-breaking’ in the media. But what exactly are these drugs and are they really as ‘breakthrough’ as they seem?

24/7 Consultant working in the NHS: 12 years experience in intensive care by P J Frost and M P Wise from QJM: An International Journal of Medicine. This article looks at the experiences of a consultant working for the NHS over the course of 12 years.

The post Celebrating the NHS at 70 appeared first on OUPblog.

August 9, 2018

Reflections on two decades of string teaching

In England, we have the expression ‘Carrying coals to Newcastle’ – a pointless action, since the place in question already has a bountiful supply. In Spain, they take oranges to Valencia and in Portugal, honey to a bee-keeper. If not quite as plentiful as oranges or honey, publishers’ lists are filled with beginner violin repertoire – what possible motivation could there be to write and publish more?

In the mid-1990s, we were directing a beginner string group in Oxfordshire. With pupils from different teachers all learning different repertoire, we decided to level the playing field and write some new pieces unfamiliar to all. And thus ‘Katie’s waltz’, ‘Rhythm fever’ and ‘Happy go lucky’ were born.

Children can be the sternest critics, not holding back in pulling a face or telling you something is boring. We reasoned that we needed to write instantly appealing tunes, with catchy rhythms and in a variety of styles that would cut through any after-school ennui. Furthermore, they had to be carefully written at the technical level of the students and – a crucial point! – make the students sound good. We’d be the first to acknowledge that many other writers have set out with the same intention and realised the same aims, but hearing students around the world, live or online, playing and enjoying our music, suggests this approach has near universal appeal.

Instrumental tuition has changed greatly over the last 20 years. While private music teaching has remained largely unchanged, teaching in schools has been transformed, with individual lessons yielding to groups and the duration of lessons becoming ever shorter. There’s also been the advent of whole-class lessons, first as Wider Ops, later as First Access, in which all the pupils in a primary-school class learn an instrument all together. Happily, the short beginner tunes we wrote 20 years ago have proved to be just as relevant in these more pressured teaching environments.

The original 1998 editions of Fiddle Time Joggers and Runners.

The original 1998 editions of Fiddle Time Joggers and Runners.With whole-class teaching, traditional music stands for two players are dispensed with, and the music is projected onto a white board at the front of the class for all players to read. A clever piece of software co-ordinates the notation and backing track, highlighting the music as it’s played and even turning the page at the right moment. This is a teaching method and technology undreamt of 20 years ago. Back then, few music books were published with any audio – cassettes (remember those?) were briefly considered for our first books, but it was five years later that we issued the first CDs. Now even these are becoming obsolete, as most users have no CD player or CD drive in their laptops, and downloadable mp3 recordings are the audio delivery of choice.

If life, famously, is ‘just one damn thing after another’ (Elbert Hubbard), then so, it seems, is a successful book series. Having got beginner violinists started, ‘jogging’ with the first finger pattern and ‘running’ with different finger patterns, it was inevitable that soon they’d need a book to help them ‘sprint’ into higher positions. A key driver for the series has been teachers writing to ask for material at ever-higher technical levels – even if the relationship between the number of students learning an instrument and technical level is pyramid shaped, with many more starting than getting to the top – there’s still a need to cater for these more advanced students with additional performance repertoire.

Writing these pieces has put us in touch with string teachers in many different countries, and we’ve presented workshops and attended conferences in the UK, across Europe, through the good offices of the European String Teachers Association, as well as Australia, Hong Kong, and Singapore.

It’s fascinating to see the similarities and differences in string teaching around the world, while recognising that we’re all working to the same objectives. We’ve heard some wonderful and inspiring stories. In Portugal, a teacher told us that when her group played our ensemble piece ‘Shark attack!’, the students, to get into the spirit, wore shark hats that they’d knitted specially, with a fin at the back and large bug eyes at the front.

We’re thrilled also that our music is played by Sounds of Palestine, a community music project that provides a safe space for children and which uses music education as a medium to achieve long-term social change for families living in refugee camps and scarred by war and conflict.

We’re glad, 20 years ago, that we decided to take those coals to Newcastle.

Featured image credit: Violin by Martin Remphry, bird by Alan Rowe, both copyright OUP.

The post Reflections on two decades of string teaching appeared first on OUPblog.

August 8, 2018

The shortest history of hatred: Part 1

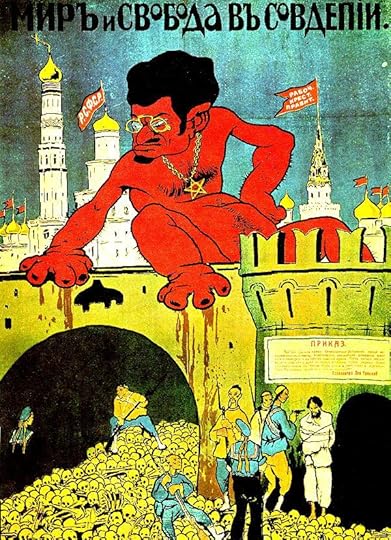

It would be unwise to leave the topic of emotions (see the posts on anger, dread, and fear), without saying something about hate and hatred. Although hate refers to intense dislike, it is curious to observe how diluted the word has become: today we can hate orange juice, a noisy neighbor, even our own close relative, and of course we hate not finding the objects we have mislaid. For some reason, to dislike, have little regard for, and resent are not enough for expressing our dissatisfaction. But along those trivial situations, we have coined phrases like hate speech, hate crime, and hate group. Those are more serious matters. Soviet propaganda treasured what it called the sacred (yes, sacred) feeling of hatred for the real and especially fictitious enemies of the regime and tried to instill it into the brainwashed citizens. Witch hunts and mass hysteria served this purpose extremely well. Newspapers and demonstrators roared from morning till night something like “Death to the Trotskyite dogs! We demand a death sentence to…” and the appeal echoed and re-echoed through the stultified populace. Probably everybody remembers Orwell’s hate week. His description is amazingly true to life. Terrible country, terrible times. What a blessing that we know none of it!

Surely, the word designating such a strong, even if hardly sacred, feeling deserves an etymologist’s attention. Engl. hate and (to give one example) its Latin synonym odium (from whose root, via French, we have the adjective odious) are opaque. The same is true of many but not of all languages that have a word for “hate.” For instance, Russian nenavidet’ “to hate” is almost transparent: it has the negative prefix ne-, the prefix na– (“on”), and the root videt’ “to see.” The overall meaning is probably “to look at something with dislike or repulsion.”

I hate you! Image credit: “Argument Argue Fight Fighting Bicker Couple” by LillyCantabile. CC0 via Pixabay.

I hate you! Image credit: “Argument Argue Fight Fighting Bicker Couple” by LillyCantabile. CC0 via Pixabay.Engl. hate has cognates everywhere in Germanic. It also occurred in the text of the Gothic Bible, translated in the fourth century by Bishop Wulfila from the Greek. Before discussing the word’s origin, it may be useful to look at the Greek words Wulfila translated as hatis (noun) and hat(j)an (verb).

One was orgē. It denoted “inclination, nature, character” and secondarily (though quite often) “irritation, wrath, malice.” We can see that the initial sense of that noun was general, with “irritation” and “wrath” being the product of the narrowing of meaning (the reference remained to one, unexpectedly “negative” trait). The other word that concerns us at the moment is thȳmós. This noun occurred in Greek texts even more often than orgē and meant “the breath of life, vitality at its inceptive state; life, soul” and, by extension, “will, ardent desire, striving for; hunger; thirst, appetite; consciousness; mood; courage, fortitude” and less often (in the plural) “wrath, malice” and “passion.” Surprisingly, “hatred” is again not what we find among the glosses, though “wrath,” “malice,” and “irritation” are surely close by. The third word we need is miseîn, which indeed meant “to hate,” and, finally, there was kholáō “to rave; to be furious.”

Before returning to Greek, it might be useful to quote the places in the Bible Wulfila translated. I’ll reproduce the relevant places not from Gothic, but from the Authorized Version: “and were by nature the children of wrath, even as others” (E II: 3); “Blessed are ye, when men shall hate you” (L VI: 22); “Love your enemies, do good to them which hate you” (L VI: 27); “That we should be saved from our enemies, and from the hand of all that hate us” (L I: 71); “do good to them that hate you” (M V: 44), and: “are ye angry at me, because I have made a man every whit whole on the Sabbath day?” (J VII: 23).

One of the most evil posters against Trotsky, with an open allusion to his Jewish origin. The Russian text says “Peace and freedom in the Russian Federation. Image credit: WhiteArmyPropagandaPosterOfTrotsky via Marxists.org. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

One of the most evil posters against Trotsky, with an open allusion to his Jewish origin. The Russian text says “Peace and freedom in the Russian Federation. Image credit: WhiteArmyPropagandaPosterOfTrotsky via Marxists.org. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Wulfila mainly needed a verb for hate and a participle for hating, rather than the noun, for the noun occurred only where the English text has wrath. In any case, in Greek we discovered four different words, in English three (hate, wrath, and be angry), while Wulfila preferred the Gothic word beginning with hat– in all cases, except in M V: 44, where the form hatjandam is a marginal gloss to fijandam. We have no way of discovering who supplied the gloss and why in those passages Wulfila had such a strong preference for the verb hat(j)an when he had the synonym fijan (we see its root in German Feind “enemy” and Engl. fiend, literally “hating”). A good deal has been written about the difference between fijan and hatan, but we may pass by that discussion.

The Goths did not only destroy Rome. They were the first Germanic speakers to be converted to Christianity. Image credit: Gothic soldiers (Missorium of Theodosius I) by Visipix. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The Goths did not only destroy Rome. They were the first Germanic speakers to be converted to Christianity. Image credit: Gothic soldiers (Missorium of Theodosius I) by Visipix. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.The Gothic translation was far from mechanical, because Wulfila drew most skillfully on the rich vocabulary of his native language (isn’t it amazing that the fourth -century Germanic barbarians had a vocabulary fully adequate, nuances and all, for translating not only the gospels but also the epistles from the convoluted, polished post-classical Greek?) and varied synonyms freely and ingeniously. In this case, he felt satisfied with the hat– words, though elsewhere for miseîn he did use fijan! It often seems that he was like a poet, listening to the effect his lines made. He must have been bilingual: Gothic and Greek. It is also known that he consulted with several knowledgeable people while doing his work. There was nothing haphazard or naïve about his translation.

We may now return to Greek. Rather unexpectedly, our survey showed that in all the Greek words but one “hatred” occupied the least significant place: we saw “inclination, nature, character; vitality, life, hunger, thirst; courage; madness, fury.” Apparently, “malice” could develop from several more general, admittedly, remote, concepts. Similar processes happen all the time, but we take them for granted. For example, the child is said to be acting up. What is the child doing? Rehearsing for a play? Getting its act together? (Another pretty obscure idiom.) No, the sweet darling has become unruly. Unless you know the meaning of the phrase to act up, you will never decipher the reference. It appears that nature, inclination, life, courage, and the rest could yield violent anger (let us note: anger, which is temporary, not hatred, which designates a permanent feeling). Did it happen because all things under the moon tend to deteriorate?

As etymologists we are forced to draw an important conclusion. In reconstructing the distant history of hate, we need not look only for other words of the near-identical meaning, because the source can be hidden in an unpredictable place. We should also explore the older senses of hate. Perhaps the most astounding find is this. I have once read that in Ossetian, an East Iranian language, the word for “love” is related to the Slavic word for “enemy.” No sources at my disposal confirm this hypothesis, but, whether correct or wrong, it is plausible and offers an example of what is called enantiosemy, that is, the coexistence of two opposite meanings in one word or ancient root (compare host and hostile and see the post for February 7, 2018). I would not have mentioned the facts of a language with which I have no familiarity if the unity of hatred and love did not loom in the distance, in our further exploration of the origin of hate.

At the moment, we’ll give way to gentler feelings and part until next week, but let me say something about the origin of the noun hatred. It has a suffix (-red), meaning “condition.” This suffix has never been productive, and today we can find it almost only in kindred. Hatred has partly ousted the reflex (continuation) of Middle Engl. hete. Hate still exists as a noun, but hatred is its more powerful rival (as could be expected).

Featured Image: Mikhail Vrubel, “The Flying Demon,” an illustration to Mikhail Lermontov’s narrative poem The Demon. “And all that was unstained and sacred/ Aroused in him contempt and hatred.” See Anatoly Liberman’s book Mikhail Lermontov, Major Poetical Works, p. 359. Featured Image Credit: Flying Demon by Mikhail Vrubel. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The shortest history of hatred: Part 1 appeared first on OUPblog.

Understanding academic impact: fear and failure, stealth and seeds

Failure is an unavoidable element of any academic career. For all but a small number of ‘superstar über-scholars’ most of the research papers we submit will be rejected, our most innovative book proposals will be politely rebuffed, and our applications for grants, prizes and fellowships will fall foul of good fortune. There is, of course, a strong correlation between ambition and failure in the sense that the more innovative and risky you try to be, the bolder the claims you try to substantiate, and the ‘bigger’ the journal you try to publish in the higher your chances of rejection.

After two decades of learning to play the journal publishing game – and it is a game – I have seen how the inbuilt conservatism of peer review processes are almost guaranteed to suffocate any fresh thinking; intellectual ambition almost killed at birth and many of our best scholars are now based beyond academe. I remember once sitting on an interview panel for a professorial position and one candidate proudly announced that he had published over two hundred journal articles and ‘had never had an article rejected!’ [Note: Exclamation mark in the original. I remember it distinctly – exploding like a non-verbal crescendo at the end of the sentence, reverberating with a cave-like quality in the small interview room and then hanging in the air like a bad smell.] This immodest boast was clearly designed to curry favour in a REF-driven context, but to me it represented little more than an admission of intellectual timidity. ‘Maybe you should try a little harder?’ I mischievously suggested.

I recently found myself in a similarly perplexing professional predicament while lunching with a ridiculously ‘senior’ professor of political science. My painful sense of academic inadequacy may have led me to rather over-emphasise that I had been appointed as the Special Adviser of a Select Committee in the House of Lords. My pudding may well have been slightly over-egged but this could not explain the rather deflating response, ‘Why the hell would you want to waste your time with that!’ Professor X retorted [Note: not my lunch partner’s real name] ‘It’s like signing-up to failure…the Government’s never going to accept what the committee says.’ With this totally unexpected ‘Why would you bother?’ reaction ringing in my ears, I quickly shifted the focus of the conversation to far more weightier matters and the long-term implications of Prof. X’s recent journal article on the political-economy of fountain pen production in Ulan Bator (apparently a booming Mongolia industry).

This conversation came back to haunt me when the Government did, with all but a few very minor concessions, reject the committee’s report. To use the language of ‘rejection’ rather underplays the Government’s response. The Government did not want to play ball, it was not interested, it said ‘go away and stop bothering us’ – the steamroller was not in the mood to be heckled.

I had failed. I had wasted my time – lots of time (and the time of lots of people).

Nine months of frenzied research, over 250 submissions of evidence, 58 witnesses, two committee visits plus lots of other activity and the meticulous crafting of a final report had really failed to have much of an impact at all. Professor X was correct…. it really had been a waste of time.

Or had it?

Three words, one little question, three short answers.

This is the challenge or risk that any social scientist takes when investing lots of time and energy in impact activities: the great problem of sowing seeds in a political context is that you can never be absolutely sure they will germinate. And even if your seeds to begin to take root and grow, the messiness of politics will inevitably ensure that it’s hard to prove an unequivocal link between your research and what happens.

Firstly, politics is a messy business. It works through the grating and grinding of a complex institutional machine and very often produces what an economist would call ‘sub-optimal’ decisions. Politics works through the planting of seeds and the injection of ideas and evidence into a contested ideological terrain. There are multiple and overlapping games being played-out at any one moment and it would be rare for any government to accept the recommendations of a select committee en masse. It is far more likely that impact will occur by stealth with the government quietly adopting the odd idea or two without fanfare, the report possibly helping to shape or inform policy well below the waterline of headline government business. That’s how politics works – through the creation of cracks and wedges, through the intellectual slow boring of hard woods and through the planting of seeds that may bear fruit in the future. But that’s not failure – it’s just how politics works.

This (secondly) explains why impact is a messy business for the social sciences. I can prove that my research was relevant, I can prove that I played a role in relation to knowledge-exchange, but I cannot claim that any of this extensive activity had a direct impact in terms of changing policy or public behaviour (or the quality of Mongolian fountain pens). This is the challenge or risk that any social scientist takes when investing lots of time and energy in impact activities: the great problem of sowing seeds in a political context is that you can never be absolutely sure they will germinate. And even if your seeds to begin to take root and grow, the messiness of politics will inevitably ensure that it’s hard to prove an unequivocal link between your research and what happens. But fuzzy impact is not failure, it just reflects the way in which the social sciences feed their insights into an increasingly complex social milieu. Which brings me to my third and final point.

I fear there is an instrumentalisation of the impact agenda occurring. Decisions regarding the investment of institutional resources and the appointment of staff are increasingly taken with a keen eye, not on the intellectual vibrancy of the project, the disruptive scholarly potential of the appointee, or the need to cultivate a culture of engaged scholarship, but on a crude, mechanical short-term calculation as to whether the outlay is likely to result in the requisite number of high-quality ‘impact case studies’. The risk is that impact becomes ‘the tail that wags the dog’ rather than a more creative endeavour through which the social sciences (re)connect with a broader society that desperately demands support and insight. Michael Burawoy’s wonderful phrase about ‘talking to multiple publics in multiple ways’ springs to mind, but to understand academic impact through either binary conceptions of ‘success’ or ‘failure’ – let alone through the lens of external audit mechanisms – risks falling into a trap of our own creation.

Featured image credit: Stacked books and journal by Mikhail Pavstyuk. CC0 via Unsplash.

The post Understanding academic impact: fear and failure, stealth and seeds appeared first on OUPblog.

The Little Red Book vs. the Big White Book

As part of our What Everyone Needs to Know series, we take a look at the famous writings of two of China’s predominant leaders.This article first appeared for The Times Literary Supplement (TLS) on 15 May 2018.

There are some similarities between former Chairman of the Communist Party of China Mao Zedong’s most famous book, Quotations from Chairman Mao Zedong (“The Little Red Book”) and current General Secretary Xi Jinping’s The Governance of China (“Big White Book”)—the second installment of which came out last year, each volume the same cream color and featuring the same photograph of the author. For example, even those in China uninterested in actually reading from the Little Red Book half a century ago would have found it politically useful to have a copy on hand and be able to claim familiarity with it—and the same goes for Xi’s Big White Book now. In addition, it is widely known that Mao’s writings were the works of many authors and there is little doubt that Xi’s ever-expanding corpus is also a collective creation.

There are, however, limits to this sometimes overstated comparison. For example, The Big White Book has not been put to nearly as many uses as the Little Red one. Only the latter was waved aloft at rallies and read aloud from in hospitals by true believers, convinced that its sacred words could make the deaf hear.

In addition, some outside China believed Mao’s short tome would offer guidance as they struggled to bring about radical change in their own countries. Today, there is increasing talk in some quarters of an exportable “China model.” Yet most foreign fans—a group that includes Mark Zuckerberg, who had a copy of Volume One on display on his desk in Silicon Valley when Lu Wei, then the chief Chinese censor, paid Facebook a visit a few years back—have so far contented themselves with claiming that Xi’s Big White Book matters simply because it offers insights into the author’s slogans, goals, and psyche.

The Little Red Book contains short sections from Mao’s writings, composed over the course of decades, while the speeches in The Big White Book were given during a short time span and appear either as lengthy excerpts or in their entirety. Mao had things to say about all the main Marxist concepts and criticized Confucianism as antithetical to his Party’s vision, while Xi ignores class struggle (neither this term nor the word “class” are listed in the Index of Volume One; instead one finds “Clash of Civilizations” and “Cloud-based Computing”). And he quotes Marx and Confucius together, as though the man Mao called a “feudal” philosopher and the German co-author of The Communist Manifesto belonged to the same philosophical school.

Only the [Little Red Book] was waved aloft at rallies and read aloud from in hospitals by true believers, convinced that its sacred words could make the deaf hear.

In China’s political system, those who end up leading do not take part in public campaigns in which they spell out what they believe and will do once in power. They attain the top spots first, then make statements about what they believe, give speeches about what they have done, and describe their goals. This means that dipping into Volume One of The Governance of China is a bit like working your way through a compilation of stump speeches. He claims that under his watch, China’s 2010 GDP will be doubled by 2020, and that the country will be a thoroughly “modern socialist” one by the middle of the century, when the People’s Republic of China turns 100.

Volume Two is more like a brochure from a company’s PR department, introducing and celebrating a brand. Xi expresses a commitment to expanding China’s reach into new parts of the world, while remaining determined to do so in a respectful manner. For instance, by not asking foreign partners to remake themselves in China’s image, but allowing them to operate in whatever distinctive manner suits them. Some of the speeches explain what Xi’s administration has done lately, while others focus on what he is determined to accomplish in the coming years.

Both volumes emphasize one central theme: China is poised to regain its stature as a great country. To do this, page after page implies or states: it needs stability, unity, and a strong leader in control.

The book’s publisher was surely aware that The Big White Book would generally be flipped through rather than read cover to cover. The set of colour images that begin Volume One, as well as the photographic inserts in Volume Two, should therefore be treated as integral parts of the text. The former show Xi as, among other things, a studious youth, a devoted husband, a caring father, a good son, down to Earth (he is photographed kicking a football), and empathetic (he is shown contributing to a disaster relief effort and listening to the concerns of villagers). The illustrations from the Volume Two present him as comfortably in charge of China (doing things such as reviewing troops) and respected abroad (striding with top world leaders at summits).

The Big White Book is hardly a page-turner. And a very large percentage of the millions of copies in circulation seem to have been given away. Still, this work needs to be taken seriously. China recently amended its constitution so that Presidents are no longer limited to two five-year terms. This raises the possibility that Xi could rule for life. The current pair of thick volumes of The Big White Book could end up being joined by enough sequels to fill a very long bookshelf.

Featured image credit: Mao Zedong by PublicDomainPictures. CC0 via Pixabay .

The post The Little Red Book vs. the Big White Book appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers