Oxford University Press's Blog, page 231

September 1, 2018

Fake news: a philosophical look at biased reasoning [excerpt]

No matter your religion, political party, or personal philosophy, you’ve likely met someone at one point or another and thought they’ve got it all wrong, or even, wow—this person is an idiot. In the search for moral truth, when we learn what is “right,” we in turn learn what is “wrong.” But how can we know whether our conclusions are sound, or the result of biased reasoning?

In the following shortened excerpt from On Truth, Simon Blackburn examines how our minds move, and questions whether or not we’re capable of seeking out “truth.”

As soon as we have perceptions of the world at all we think about what they imply and what we can infer from them—a perception has implications, whereas a sensation just happens. A glimpse or whiff is just something that happens, but when it is interpreted, consequences follow, expectations arise, and significances are discerned. And the ways in which people’s minds move are as much the subject of criticism and conversation as our other practices.

So what is meant if we say that a person, X, takes something, A, as a reason for some conclusion, B? A first stab would be that when X becomes aware of A, it moves him towards a mental state B. Notice that B might be a belief, but it could be something else: a desire, the formation of an intention or plan, an emotional reaction, or an attitude to something or some person. The movement towards B might be checked by something else in X’s mind, such as countervailing reasons against B. But X is, as it were, given a shove towards B.

This is a good start, but I think we need more than this. For X may find himself moved towards B but against his will or his better judgment. He wouldn’t endorse the movement from A towards B, or try to justify his ending up at B by citing A (he might feel guilty that A moves him towards B, so recognizing that it is no reason for B at all). So we can try instead that X takes A to be a reason for B if X does endorse and defend the tendency. He thinks that from the common point of view, a move from A towards B is one to be approved of. He can advocate it in a conversation designed to achieve such a common point of view.

A perception has implications, whereas a sensation just happens.

Such endorsements or approvals can come in degrees. At its most lukewarm it might be that X does not actually disapprove of taking a move from awareness of A towards B. Further along he might approve of it, and eventually disapprove of anyone who, aware of A, fails to be moved towards B. He would be holding that the move is compulsory.

The endorsements and approvals in question might be ethical, but they need not be. If someone moves from hearing a politician say something to believing it, one might criticize them as credulous or gullible, and these are criticisms of the way their minds work, but not in a particularly ethical or moral register. It is their intelligence or savoir faire that is at fault, even if their heart is in the right place.

Of course, I have abstracted a little for the sake of simplicity. As holism, which we met earlier, reminds us, any human being becoming aware of something is going to be adding it to an enormous background of things she already believes, knows, desires, intends, and so forth. It may be that a move from A to B is to be approved of against some backgrounds and not others. We may want to say that other things being equal, A is a reason for B, or just that A is sometimes a reason for B, deferring to such variations.

But sometimes we think it is compulsory or categorical. It doesn’t matter what else you believe if you learn that Y is in China or India, and then that he is not in India; it is right, then, to infer that he is in China. If you believe that there are five girls in the room, and then that there are five boys, it is right to infer that there are ten children.

Much of the philosophy of science is concerned not with questions of logical consistency, or with purely mathematical inferences and proofs, but with evaluating interpretations of experiments and observations. It needs to think about such things as our tendencies to generalize, the use of analogies and models, our bias towards simplicity in explanations, and the amount of confidence any one interpretation of things should command.

So we can discuss which movements of the mind are reasonable or unreasonable in much the same way as we discuss which motivations and behaviors are admirable, or compulsory or impermissible. It follows that skepticism about the idea of moral truth should suggest skepticism about assessment of mental tendencies as reasonable or unreasonable.

Much of our reasoning is automatic and implicit. A perception that there is a chair in front of me leads me to suppose that there is one behind me after I turn round. Isn’t it possible that I should have had the perception although the chair was an ephemeral being, a manifestation that itself carried no implications for the moment when I twirl around and bend my knees? Yes, barely possible. But a mind that took that possibility to be wide open, that failed to make the inference, is not one well adapted to life in this wonderfully regular and predictable world in which we live, and in which we have been adapted to live. It would be neither useful nor agreeable to possess such a mind.

Much of our reasoning is automatic and implicit.

When we talk of reason, as when we talk of aesthetics and morality, things become much clearer when we stop dealing with truth in the abstract and look at the “particular go” of it. We then understand why we want it: it is because we do not want people thinking badly, faltering along foolish paths of inference, and we need to signal what counts as doing so.

If we start where we are and look at our procedures of conversation, agreement and disagreement— and at our actual successes in learning how to live and what to believe—we can achieve modest confidences, although at any time we may encounter problems that stump us. In other words, we locate “moral truth” or “rational truth” as the axis around which important discussions and enquiries revolve, hopefully informed by whatever we know and think we know about human beings, their limitations, and their possibilities. The enquiry is essentially practical: we can say that its goal is truth, but it can as well be described as knowing when and how to act, whom to admire, how to educate people, what to believe, or, all in all, how to live.

Featured image credit: background-newspaper-press-1824828 by MIH83. CC0 via Pixabay .

The post Fake news: a philosophical look at biased reasoning [excerpt] appeared first on OUPblog.

August 31, 2018

Modelling roasting coffee beans using mathematics: now full-bodied and robust

Coffee is one of the most traded commodities in the world, valued at more than $100 billion annually. Even if you’re not an entrepreneur looking for the next big coffee venture, you’ll probably still care about how to make the 2.25 billion cups of coffee globally consumed every day as delicious as possible. Fortunately, scientists and researchers have partnered with large coffee companies in the hopes of understanding some of the complexities behind making a good cup of coffee: specifically, how coffee beans are roasted.

During the roasting process, partially dried coffee beans turn from green to yellow to various shades of brown, depending on the length of the roast. Once the residual moisture content within the bean dries up in the yellowing phase, crucial aromas and flavours are developed. However, the associated chemical reactions that produce these desirable coffee traits are highly complex and not well understood. This is partially due to the fact that the browning reactions linked to aroma and flavour development, called the Maillard reactions, is comprised of a large network of individual chemical reactions, where only preliminary understanding of the network’s construction exists.

To tackle the challenges involved with creating mathematical models for the Maillard reactions, along with other chemical reaction groups in a roasting coffee bean, we use the concept of a Distributed Activation Energy Model (DAEM), originally developed to describe the pyrolysis of coal. Not dissimilar to the Maillard reactions, the pyrolysis of coal involves large numbers of parallel chemical reactions and, using the DAEM, can be simplified to a single global reaction rate that describes the overall process. Crucially, however, the DAEM relies on knowing the distribution of individual chemical reactions beforehand. While the overall distributions associated with the Maillard chemical reactions remain unknown, we can reasonably approximate the reaction kinetics of the majority of the Maillard chemical reaction group.

However, the DAEM approach to chemical reaction groups only works when each of the reactions is happening parallel of one another. Because of this, we examine a simplified pathway of reactions involving sugars (which are linked to the formation of Maillard products) and separate groups of reactions to follow a progression of reactants to products. Specifically, we examine how sucrose first hydrolyses into reducing sugars, which in turn become either Maillard products or products of caramelisation. This division of this sugar pathway network allows us not only to fit each reaction subgroup with different parameter values, but also to determine that the hydrolysis of sucrose creates a “bottleneck” in the sugar pathway and prevents Maillard products from forming too early in the roast.

Even if you’re not an entrepreneur looking for the next big coffee venture, you’ll probably still care about how to make the 2.25 billion cups of coffee globally consumed every day as delicious as possible.

To model the local moisture content and temperature of the bean, two variables that crucially change which chemical reactions can occur during the roast, we use multiphase physics to describe how the solid, liquid, and gas components within the coffee bean evolve. This is a crucial difference to what has previously been done to model coffee roasting, as existing models often treat the coffee bean as a single “bulk” material. Additionally, unlike in previous multiphase models for roasting coffee beans, we allow the porosity of the bean to change according to the consumption of products in the sugar pathway chemical reaction groups. We also incorporate a sorption isotherm, an equilibrium vapour pressure specific to the evaporation mechanisms present in coffee bean roasting, in our model. Finally, to reduce the system variables to functions of a single spatial variable and time, we model a whole coffee bean as a spherical “shell”, while modelling a chunk of a coffee bean as a solid sphere. This is another improvement to previous multiphase models, which disagreed with recent experimental data describing the moisture content in both roasting coffee chunks and roasting whole beans.

Numerical simulations of this improved multiphase model (referred to as the Sugar Pathway Model) provide several key conclusions. Firstly, the use of spherical shells and solid spheres to describe whole and broken coffee beans, respectively, allows for good agreement with experimental data while simplifying the mathematical model’s structure. Secondly, due to the large number unknowns in the model, the Sugar Pathway Model can be fit to experimental data using a variety of parameter values. While this could be viewed as a drawback to the Sugar Pathway Model, we also show that small changes in parameter values do not drastically change the model’s predictions. Hence, the Sugar Pathway Model provides a reasonable qualitative understanding of how to model key chemical reactions that occur in the coffee bean, as well as how to model coffee bean chunks differently to whole coffee beans.

While largely theoretical, the Sugar Pathway Model provides a balance between the immensely complicated underlying physical processes occurring in a real-life coffee bean roast and its dominant qualitative features predicted by multiphase mathematical models. Additionally, industrial researchers can cheaply and efficiently use these multiphase mathematical models to determine the important features at play within a coffee bean under a variety of roasting configurations. While a basic framework for the roasting of a coffee bean is presented here, understanding the qualitative features of key chemical reaction groups allows us to get one step closer to that perfect cup of coffee.

Featured image credit: Coffee by fxxu. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Modelling roasting coffee beans using mathematics: now full-bodied and robust appeared first on OUPblog.

How much do you know about opioids? [quiz]

PAINWeek, the largest US pain conference for frontline clinicians with an interest in pain management, takes place this year from 4th September to 8th September. The conference focuses on several different aspects of pain management, and indeed many different methods of pain management exist. None is so ancient, widely-known, and controversial, however, than pain management using opioids. Since the time of the ancient Mesopotamians and Egyptians, drugs associated with opium have been known as an effective treatment for pain. Opium comes from the sap of the seeds of the opium poppy, Papaver somniferum, and acts as a narcotic. As highly addictive substances, the medical world has battled over the appropriate use of opioids ever since the drug began to be circulated in the early 1700s. While these drugs can provide immensely successful pain relief, the possibility of the patient becoming addicted to opioids is too great to be ignored. Indeed, the US currently faces an epidemic of opioid addiction, largely stemming from prescribed opioids.

Studies indicate that many patients are unaware of the dangers of opioid addiction, which is why it is vital that knowledge of opioid use is available publicly. Take our quiz to test your knowledge of opioids in relation to pain management.

Featured image credit: Close-up drugs by Pexels. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post How much do you know about opioids? [quiz] appeared first on OUPblog.

August 30, 2018

Remembering Sterling Stuckey, OUP author and scholar on Slave Culture

Executive Editor, Tim Bent, reflects on his work and friendship with OUP author, Sterling Stuckey.

any of us at Oxford noted with sadness the death of Sterling Stuckey on August 15th at the age of 86. Stuckey was the author of Slave Culture: Nationalist Theory and the Foundations of Black America, which OUP first published in 1987 and re-issued 25 years later, and which was a foundational text in our understanding of the culture of slavery—its complexity and richness in its defining forms of resistance, resilience, and celebration. “Though slave culture was treated for centuries as inferior, it was the lasting contribution of slaves to create an artistic yield that matched their enormous gift of labor, in tobacco and cotton,” Stuckey wrote in his preface.

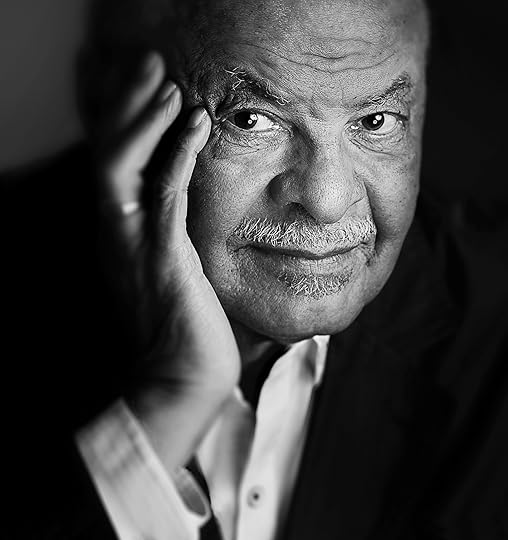

Sterling Stuckey in 2013. Photo by Benoit Malphettes.

Sterling Stuckey in 2013. Photo by Benoit Malphettes.As an editor, I helped Sterling bring out out the 25th anniversary edition of Slave Culture and got to know him well. We met once a year, usually in September, when he came to New York to listen to some jazz, meet with friends, and talk about books and new projects. He once gave me a copy of his mother’s poems, of which he was very proud. I was honored by the gift. We were to meet in a few weeks to talk about his new project, which involves Moby Dick, and specifically the degree to which Herman Melville was indebted to Frederick Douglass in the inspiration for and conception of the novel. The Great White Whale represents American slavery, he argues (the character of Pip is actually Douglass himself). Sterling was excited about setting off to make his case. I was looking forward to that conversation and where it would take us. We would also likely have talked about his long-planned biography of Paul Robeson, one of his heroes (and whom he had met, just as he had W. E. B. Du Bois), a project he was determined, one day, to finish.

You can read Stuckey’s obituary in The New York Times.

Sterling Stuckey was a renowned Historian and Professor Emeritus of History specializing in American slavery at University of California, Riverside.

Featured Image Credit: “Fountain” by Skitterphoto. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Remembering Sterling Stuckey, OUP author and scholar on Slave Culture appeared first on OUPblog.

Taking your better self to school: 5 renewals for teachers

For teachers, “back to school” can convey eagerness and excitement. It can also evoke fear, anxiety, and dread. Few of us have the pleasure of thriving in our schools every day, every year. If we learned of ways to bolster ourselves would we try them?

So many encounters can worry us and, our reactions to those worries can stay with us for a long time. We cannot always control the challenges that come our way, but we can be intentional about our reactions to them.

Ask yourself, “Who do I want to be in my school?” The answer can be clarifying, uplifting, motivating. Some are fond of answering, “I want to be my best.” “I want to do my best.”

Consider, though, the subtle differences between being and doing, between best and better. The intent to do better offers us both action and aim. “I want to enter school each day, aiming to do better.” Being suggests who we are. Doing suggests actions we take.

Starting the school year feels like a new beginning. And, it can be. What would you like for your new beginnings this year?

Five simple ideas offer possibilities for “taking your better self to school.”

1. Prepare yourself: walk through the door with intention

Many professionals use a routine to prepare themselves for a meeting, a presentation, the workday. That routine may span reviewing plans and schedules, greeting co-workers, and preparing the workspace for optimal accomplishment.

Civility, camaraderie, and composure can take us to our better selves. We can, each day, enter our schools aiming to be mentally and physically kind and strong, generous and judicious, calm and energized.

As we prepare for school each day, we can do the same, acknowledging our own personal and professional intentions. Do we prepare for reacting with calm wisdom in difficult moments? Do we avoid perseverating on negative thoughts, frustrations, and self-derision? Do we model the “better self” that helps others in their work?

Civility, camaraderie, and composure can take us to our better selves. We can, each day, enter our schools aiming to be mentally and physically kind and strong, generous and judicious, calm and energized. We can choose to do better day by day.

2. Notice your attire: your image has influence

Most of us choose different clothing for mowing the lawn, seeing a movie, or attending a ceremony. Do we also consider our clothing choices at school?

We are professionals. We are educated, skillful, knowledgeable leaders. Our attire can signal readiness and respect for our workdays and those we encounter there.

Some of us may lean toward wearing apparel that is too dressy, too casual, too revealing. Our clothing choices influence not only those who attend and work in our schools, but also the guests, parents, and community members who visit them. Our clothing can influence our mood and our self-respect.

Rethinking attire is not a recommendation for an expensive, expansive wardrobe. Appropriate school attire can be clean and simple. The same bottoms may be worn multiple times a week with different tops. Collared shirts can be casual and professional. Comfortable, attractive shoes can substitute for flip-flops and gym shoes.

Preparing ourselves for school by donning thoughtful, appropriate attire sends a message: “I know who I am.” “I know why I teach.” And, “I am dressing for the occasion.”

3. Fear not: conflict is perennial

Conflicts big and small occur every day in schools. They are inevitable.

At some time during our careers, many of us have said, “I hate conflict!” But, hating conflict, though common, rarely eases it or our reactions to it. Quite the contrary. The more strongly we resist and sulk, the more deeply we sustain the turmoil.

Conflict, whether big or small, is often felt deeply. It can consume us! Many of us do not easily shake off perceived slights and, some of us habitually perseverate, playing and replaying the offense long after it has occurred.

Who is most hurt by hanging on to the insult or criticism? Not likely the offender. He or she may not even know there was a problem. When attaching ourselves to conflict, we can lose the potential of our “better selves” at school. Holding conflict within us diminishes our effectiveness and often compromises our good health.

Enter school with deep breaths of self-assurance and wisdom. Decide not to allow the inevitable conflicts to take you “off your game.” Feel a solid shield of strength. Substitute anger and fear with compassion and curiosity.

When attaching ourselves to conflict, we can lose the potential of our “better selves” at school. Holding conflict within us diminishes our effectiveness and often compromises our good health.

Don’t be gobbled up by conflict. Notice it. Be curious about it. But, do not let it chisel away at your strength, stamina, and heart for teaching.

4. Entice learning: it benefits both you and your students

Not all students want to learn every day, in every class. The more we push them, the less they may be willing to participate. The more we use criticism or compliments to motivate, the more students can resent our efforts to manipulate them.

Consider shifting from praise and rewards to enticements that attract and appeal to students’ curiosity. When we capture imaginations, offer solvable puzzles, and provide imagery to ignite possibilities, we entice students to be curious.

We make the effort and take the responsibility to lead our students toward learning. We set up possibilities for interesting problem-solving. We think of better ways to prompt interest, curiosity, and humor as we lead our students to solve and imagine.

When we entice learners, we help them want to learn.

5. Be cordial: being friends is not necessary

Teachers in schools need not be friends to create a highly effective, respectful, and collegial teaching environment. In the sometimes-fragile ecosystems of schools, functioning respectfully and communicating appropriately may be more valuable than friendships.

Sharing personal information and holding out-of-school gatherings can appear to be “one happy family.” Yet, expecting all colleagues to function as friends may be as misguided as expecting the same from students.

Being cordial and respectful can contribute to healthy relationships in schools. And, friendly, professional distance can be an important facet of school life and thriving educators.

The post Taking your better self to school: 5 renewals for teachers appeared first on OUPblog.

August 29, 2018

Etymology gleanings for August 2018

The following items are my answers to the queries by Stephen Goranson

In a jiffyStephen Goranson has offered several citations of this idiom (it means “in a trice”), possibly pointing to its origin in sailor slang. English is full of phrases that go back to the language of sailors, some of which, like tell it to the marines, by and large, and the cut of one’s jib (to cite a few), are well-known. They have been collected and explained, and the journal Mariner’s Mirror (incidentally, a joy to read) contains numerous articles on their origin. In a jiffy has not turned up there (I have excerpted the entire set for my etymological database). Thus, having nothing to say about the environment in which the idiom was coined, I would like to tell a story about its possible derivation.

Jig, jag, jog. Image credit: Man Jogging Running Man Exercise Healthy Run by Free-Photos. CC0 via Pixabay.

Jig, jag, jog. Image credit: Man Jogging Running Man Exercise Healthy Run by Free-Photos. CC0 via Pixabay.Jiffy is (of course!) a word of “unknown origin,” though its connection with the verb jiffle “to shuffle, fidget” has been noticed. Two scholars have dealt with jiffy. I’ll begin with the second one. Toward the end of his life, Wilhelm Braune (1850-1926), a renowned Germanic specialist, published a series of articles on Romance etymology. They appeared in a journal devoted to Romance linguistics and literature, but in Germany and in German. The man’s full name was Theodor Wilhelm Braune; however, “the whole world” knew him as Wilhelm. Yet the signature under his contributions to the Romance periodical is invariably Theodor Braune, as though he wanted to distance himself from his Germanic persona. The article that interests us at the moment appeared in 1922 and is devoted to the roots g-b and g-f.

Braune collected several hundred Germanic words that were allegedly borrowed into Romance, and in his lists one also finds some English verbs and nouns (mainly regional). This series of articles is truly amazing, for it is so much out of character. Braune belonged to the school of German scholars who followed in the footsteps of Jacob Grimm and formed a group known in the history of linguistics as Neogrammarians (in German Junggrammatiker). Their emphasis was on a strict observance of phonetic correspondences (called at that time phonetic laws), and Braune wrote a typical Neogrammarian manual of Old High German, a book that ran into numerous editions, and, although it has been revised by several later editors, in essence it is still the same immensely useful old book. But in the article I am here talking about we are invited to a regular feast of disparate words, united by the alleged original meaning that Braune reconstructed as “to gape.”

Guffaw or a gaffe? Image credit: Man Embarrassing Embarrassed Scared Flash Of Genius by sipa. CC0 via Pixabay.

Guffaw or a gaffe? Image credit: Man Embarrassing Embarrassed Scared Flash Of Genius by sipa. CC0 via Pixabay.The entire series is of the same type. It was received very badly. To be sure, Braune’s articles could not be rejected, but the comments by Romance scholars were highly critical, while his Germanic colleagues ignored those publications. I have never seen a single reference to them, and, if I had not done with the German journal (Zeitschrift f. romanische Philologie) what I have done with Mariner’s Mirror, I would never have run into them. Braune’s conclusions resemble those of his distant predecessor (about whom see below) and those by Wilhelm Oehl, a Swiss researcher who wrote a book, as well as many stimulating articles, on so-called primitive creation and to whom I have referred more than once (see, for example, the post for 22 August 2007). Braune cited Engl. gaff “a fair; any public place of amusement,” gaffe “an embarrassing blunder,” guff “nonsense,” guffaw “a loud and boisterous laugh,” and even gaffer “old man” (usually derived from godfather), along with dozens of almost identical words from German, Scandinavian, and Dutch. Engl. jiffle and jiffy did not escape him either.

I don’t think Braune’s conjectures were ignored in England and the United States: rather, no English etymologist has ever read those articles. The overall meaning “to gape” does not look like a convincing semantic base for Braune’s lists, but most of his words certainly appear to have something in common. The origin of English words beginning with j-, unless they are obvious borrowings from French, is usually obscure. This is true of job, jog, jib, jig, and many others. Those are most often “low words,” to quote Samuel Johnson, slang, and obvious sound-symbolic and sound imitative formations. Braune’s examples form a family of etymological bastards. That is why their origin is “unknown,” and we may call them related, but certainly not in the Neogrammarian sense of this term. With them we probably come as close to the beginning of human speech as we can. I also note that jiff-le and fidg-et, if we disregard the suffixes, are mirror images of each other: whether one says jiff or fidge, the impression the sound complex makes will be the same. However, the common sematic denominator of such formations is elusive.

The etymologist and spiritualist Hensleigh Wedgwood via Anonymous. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The etymologist and spiritualist Hensleigh Wedgwood via Anonymous. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.It is amazing that a study like this came from the pen of a consistent Neogrammarian. We should now jump from 1923 to 1855. Etymology, especially English etymology, is still in diapers. Almost every volume of Transactions of the Philological Society publishes a paper by Hensleigh Wedgwood. Many years later, he will become the main predecessor and even opponent of Walter W. Skeat. Today he is almost forgotten. His 1855 contribution is titled “On Roots, mutually connected by reference to the term Zig-zag” (I have retained the capitalization of the original). So now the unifying sense is declared to be not gaping but zigzag. No doubt, Braune never leafed through those volumes. Otherwise, he would have been surprised to encounter jig, jag, jog, juggle, goggle, job, jibe, giggle, giffle ~ jiffle, and jiffy, the latter defined as “an instant, the time of a single vibration,” among dozens of words that begin with neither g nor j. The curious thing is that a seasoned historical linguist who knew every sound correspondence (Braune) and an amateur who was wont to derive all words of all languages from sound-imitative complexes and did not think much of the Neo-Grammarian laws (Wedgwood) suggested not only similar solutions of the origin of jiffy but even gave their respective papers almost identical titles. Both were probably close to the truth, regardless of whether jiffy and its kin suggested gaping or zigzagging to their creators. The environment in which this word was coined remains undiscovered. But Admiral Smyth’s non-inclusion of jiffy in his famous The Sailor’s Word-Book is a warning signal when it comes to positing the word’s home at sea.

Katie, bar the door. Image credit: Scotland’s story : a history of Scotland for boys and girls by Marshall, H. E. (Henrietta Elizabeth). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Katie, bar the door

Katie, bar the door. Image credit: Scotland’s story : a history of Scotland for boys and girls by Marshall, H. E. (Henrietta Elizabeth). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Katie, bar the doorStephen Goranson remembers that his mother used to say: “It’ll be Katy bar the door.” He wonders whether this strange phrase has anything to do with the first word of cater-corner (or kitty-corner), so that the reference is to a katy (diagonal) bar across the door.

In 1992 (Notes and Queries 237, p. 376), Fredrick G. Cassidy, the editor of Dictionary of American English (DARE) wrote the following: “In the United states today there is a vogue for the exclamation, ‘Katie, bar the door!’ used when any situation seems desperate or things are getting out of hand.” The best DARE’s team could do was to relate the phrase to the assassination of King James I of Scotland in 1437, when “Kate Barlass”—Lady Catherine Douglas—according to legend, thrust her arm in the staples of the door, from which the bar had been removed, thus preventing the murderers for a while gaining access to the house. Her arm was broken, but her heroic act was sung in popular ballads, with “Katie, bar the door!” as the refrain. Cassidy stated that many facts need verification but added that “It is certainly not the one about the contest of silence between a husband and wife called ‘Get up and bar the door.” He asked for any clues to the origin of the song, but no one responded.

More answers at the end of September.

Featured Image: In a jiffy. Image credit: Deadline Stopwatch Clock Time Pressure Watch by freeGraphicToday. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Etymology gleanings for August 2018 appeared first on OUPblog.

Ringtone wins the 2018 George R. Terry Book Award

e are proud to announce that the winner of this year’s George R. Terry Book Award is Ringtone: Exploring the Rise and Fall of Nokia in Mobile Phones, by Yves Doz and Keeley Wilson. The George R. Terry Book Award is awarded to the book that has made the most outstanding contribution to the global advancement of management knowledge. The prize was presented at the Academy of Management’s annual conference, and we would like to take this opportunity to congratulate our authors on this prestigious achievement. To celebrate, we are taking a look back at previous Terry Award winners and finalists.

Ringtone by Yves Doz and Keeley Wilson 2018: Winner

In less than three decades, Nokia emerged from Finland to lead the mobile phone revolution. It grew to have one of the most recognizable and valuable brands in the world and then fell into decline, leading to the sale of its mobile phone business to Microsoft. This book explores and analyzes that journey and distils observations and learning points for anyone keen to understand what drove Nokia’s amazing success and sudden downfall.

Trust in a Complex World by Charles Heckscher

2016: Winner

This book explores current conflicts and confusions of relations and identities, using both general theory and specific cases. It argues that we are at a catalyzing moment in a long transition from a community in which the prime rule was tolerance, to one with a commitment to understanding; from one where it was considered wrong to argue about cultural differences, to one where such arguments are essential.

Hyper-Organization by Patricia Bromley and John W. Meyer

2016: Finalist

Provides a social constructivist and institutional explanation for expansion of organizations and an overview of main trends in organization theory. Much expansion is hard to justify in terms of technical production or political power, it lies in areas such as protecting the environment, promoting marginalized groups, or behaving with transparency.

Making a Market for Acts of God by Patricia Jarzabkowski, Rebecca Bednarek, and Paul Spee

2016: Finalist

This book brings to life the reinsurance market through vivid real-life tales that draw from an ethnographic, “fly-on-the-wall” study of the global reinsurance industry over three annual cycles. This book takes readers into the desperate hours of pricing Japanese risks during March 2011, while the devastating aftermath of the Tohoku earthquake is unfolding. To show how the market works, the book offers authentic tales gathered from observations of reinsurers in Bermuda, Lloyd’s of London, Continental Europe and SE Asia as they evaluate, price and compete for different risks as part of their everyday practice.

A Process Theory of Organization by Tor Hernes

2015: Winnerhttps://global.oup.com/academic/produ...

This book presents a novel and comprehensive process theory of organization applicable to ‘a world on the move’, where connectedness prevails over size, flow prevails over stability, and temporality prevails over spatiality. The framework developed in the book draws upon process thinking in a number of areas, including process philosophy, pragmatism, phenomenology, and science and technology studies.

The Institutional Logics Perspective by Patricia H. Thornton, William Ocasio, and Michael Lounsbury

2013: Winner

How do institutions influence and shape cognition and action in individuals and organizations, and how are they in turn shaped by them? This book analyzes seminal research, illustrating how and why influential works on institutional theory motivated a distinct new approach to scholarship on institutional logics. The book shows how the institutional logics perspective transforms institutional theory. It presents novel theory, further elaborates the institutional logics perspective, and forges new linkages to key literatures on practice, identity, and social and cognitive psychology.

Neighbour Networks by Ronald S. Burt

2011: Winner

There is a moral to this book, a bit of Confucian wisdom often ignored in social network analysis: “Worry not that no one knows you, seek to be worth knowing.” This advice is contrary to the usual social network emphasis on securing relations with well-connected people. Neighbor Networks examines the cases of analysts, bankers, and managers, and finds that rewards, in fact, do go to people with well-connected colleagues. Look around your organization. The individuals doing well tend to be affiliated with well-connected colleagues.

Managed by the Markets by Gerald F. Davis

2010: Winner

Managed by the Markets explains how finance replaced manufacturing at the center of the American economy, and how its influence has seeped into daily life. From corporations operated to create shareholder value, to banks that became portals to financial markets, to governments seeking to regulate or profit from footloose capital, to households with savings, pensions, and mortgages that rise and fall with the market, life in post-industrial America is tied to finance to an unprecedented degree. Managed by the Markets provides a guide to how we got here and unpacks the consequences of linking the well-being of society too closely to financial markets.

Featured image credit: Books by Christopher. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Ringtone wins the 2018 George R. Terry Book Award appeared first on OUPblog.

August 28, 2018

The dilemma of ‘progress’ in science

Most practicing scientists scarcely harbor any doubts that science makes progress. For, what they see is that despite the many false alleys into which science has strayed across the centuries, despite the waxing and waning of theories and beliefs, the history of science, at least since the ‘early modern period’ (the 16th and 17th centuries) is one of steady accumulation of scientific knowledge. For most scientists this growth of knowledge is progress. Indeed, to deny either the possibility or actuality of progress in science is to deny its raison d’être.

On the other hand careful examination by historians and philosophers of science has shown that identifying progress in science is in many ways a formidable and elusive problem. At the very least scholars such Karl Popper, Thomas Kuhn, Larry Laudan and Paul Thagard while not doubting that science makes progress, have debated on how science is progressive or what it is about science that makes it inherently progressive. Then there are the serious doubters and skeptics. In particular, those of a decidedly postmodernist cast of mind reject the very idea that science makes progress. They claim that science is just another ‘story’ constructed ‘socially’; by implication one cannot speak of science making objective progress.

A major source of the problem is the question of what we mean by the very idea of progress. The history of this idea is long and complicated as historian Robert Nisbet has shown. Even narrowing our concern to the realm of science we find at least two different views. There is the view espoused by most practicing scientists mentioned earlier, and stated quite explicitly by physicist-philosopher John Ziman that growth of knowledge is manifest evidence of progress in science. We may call this the ‘knowledge-centric’ view. Contrast this with what philosopher of science Larry Laudan suggested: progress in a science occurs if successive theories in that science demonstrate a growth in ‘problem–solving effectiveness’. We may call this the ‘problem-centric’ view.

The dilemma lies in that it is quite possible that while the knowledge-centric view may indicate progress in a given scientific field the problem-centric perspective may suggest quite the contrary. An episode from the history of computer science illustrates this dilemma.

Around 1974, computer scientist Jack Dennis proposed a new style of computing he called data flow. This arose in response to a desire to exploit the ‘natural’ parallelism between computational operations constrained only by the availability of the data required by each operation. The image is that of computation as a network of operations, each operation being activated as and when its required input data is available to it as output of other operations: data ‘flows’ between operations and computation proceeds in a naturally parallel fashion.

The dilemma lies in that it is quite possible that while the knowledge-centric view may indicate progress in a given scientific field the problem-centric perspective may suggest quite the contrary.

The prospect of data flow computing evoked enormous excitement in the computer science community, for it was perceived as a means of liberating computing from the shackles of sequential processing inherent in the style of computing prevalent since the mid-1940s when a group of pioneers invented the so-called ‘von Neumann’ style (named after applied mathematician John von Neumann, who had authored the first report on this style). Dennis’s idea was seen as a revolutionary means of circumventing the ‘von-Neumann bottleneck’ which limited the ability of conventional (‘von Neumann’) computers from exploiting parallel processing. Almost immediately it prompted much research in all aspects of computing — computer design, programming techniques and programming languages — at universities, research centers and corporations in Europe, the UK, North America and Asia. Arguably the most publicized and ambitious project inspired by data flow was the Japanese Fifth Generation Computer Project in the 1980s, involving the co-operative participation of several leading Japanese companies and universities.

There is no doubt that from a knowledge-centric perspective the history of data flow computing from mid-1970s to the late 1980s manifested progress — in the sense that both theoretical research and experimental machine building generated much new knowledge and understanding into the nature of data flow computing and, more generally, parallel computing. But from a problem-centric view it turned out to be unprogressive. The reasons are rather technical but in essence it rested on the failure to realize what had seemed the most subversive idea in the proposed style: the elimination of the central memory to store data in the von Neumann computer: the source of the ‘von Neumann bottleneck’. As research in practical data flow computing developed it eventually became apparent that the goal of computing without a central memory could not be realized. Memory was needed, after all, to hold large data objects (‘data structures’). The effectiveness of the data flow style as originally conceived was seriously undermined. Computer scientists gained knowledge about the limits of data flow, thus becoming wiser (if sadder) in the process. But insofar as effectively solving the problem of memory-less computing, the case for progress in this particular field in computer science was found to have no merit.

In fact, this episode reveals that the idea of the growth of knowledge as a marker of progress in science is trivially true since even failure — as in the case of the data flow movement — generates knowledge (of the path not to take). For this reason as a theory of progress knowledge-centrism can never be refuted: knowledge is always produced. In contrast the problem-centric theory of progress — that a science makes progress if successive theories or models demonstrate greater problem solving effectiveness — is at least falsifiable in any particular domain, as the data flow episode shows. A supporter of Karl Popper’s principle of falsifiability would no doubt espouse problem-centrism as a more promising empirical theory of progress than knowledge-centrism.

Featured image credit: ‘Colossus’ from The National Archives. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The dilemma of ‘progress’ in science appeared first on OUPblog.

Teenage rebellions: families divided by religion in the Reformation

In her latest book, Åsne Sierstad—the author of The Bookseller of Kabul—follows the true story of two Norwegian sisters, who reject their parents’ moderate Islam to embark on a journey that leads, ultimately, to jihad in Syria. It’s a story familiar in the UK, where we have seen cases of teenagers like Amira Abase, Begum and Kadiza Sultan from Bethnal Green Academy running away to Syria in 2015.

Teenage rebellion is nothing new and religion can be a powerful flashpoint between parents and their children, convinced that the older generation has got it all wrong. As radical Islam attracts teenagers in 21st century Europe, so in early modern England the Reformation produced versions of Protestantism and Catholicism that provided powerful ways for children to reject their parents’ beliefs.

The Protestant Jacobean Archbishop of York, Tobie Matthew (1544-1628), suffered one of the most high-profile teenage rebellions when his son, also called Tobie Matthew (1577-1655), converted to Catholicism, eventually becoming a Catholic priest. As a leader of the Protestant Church of England, this was embarrassing enough for Archbishop Matthew, but to make it worse, Archbishop Matthew had a reputation for hunting down and persecuting Catholics. His son was converted and then ordained by some of the Archbishop’s longstanding enemies in the Catholic Church.

Archbishop Matthew’s pursuit of Catholics was relentless and driven by a genuine belief that Catholics were damned and the agents of Satan. Matthew saw Catholics as traitors and rebels, and the gunpowder plot of 1605—when Catholic plotters tried to blow up parliament—just confirmed his beliefs. Archbishop Matthew spent his career persecuting Catholics and was part of the regime that executed the Catholic gentlewoman, Margaret Clitherow, by crushing her to death between stones in York in 1586.

Image credit: Commemorative plaque for Margaret Clitherow on the Ouse Bridge, York. Photo by Pabloasturias. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: Commemorative plaque for Margaret Clitherow on the Ouse Bridge, York. Photo by Pabloasturias. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Not only did Tobie Matthew Jr., question his father’s values, he embraced the religion that Archbishop Matthew had devoted his career to destroying. In 1605, Tobie Matthew Jr. begged to be allowed to travel abroad but, suspecting his motives, his parents initially refused. His mother, Frances, even offered him her fortune if he stayed in England and married. Eventually, Tobie Matthew Jr. was allowed to go on the condition that he only went to Protestant countries, but needless to say, as soon as he crossed the channel he went to Italy, the heart of the Catholic Church, and converted to Catholicism.

Tobie Matthew Jr. knew the impact that his conversion would have on his parents, writing that “it would be to take a sort of life” from his parents “who gave their life to me”. Indeed, his parents were devastated. Archbishop Matthew told his son that he had broken Frances’ heart, telling him to stay away from his mother—whose happiness the Archbishop rated above the lives of a “hundred sons”. Nor did it change Archbishop Matthew’s views of Catholicism; he continued to prosecute English Catholics as his own son, Tobie, was in and out of prison and eventually forced into exile for his own Catholicism.

If teenage rebellion is a constant theme through history, so too is parental love. Whatever Archbishop Matthew may have claimed, he and Frances devoted endless time and effort to protecting their oldest son. Frances looked after Tobie Matthew Jr. when he was ill and Archbishop Matthew sent friends and colleagues to try and convince him to convert. After he was ordained as a Catholic priest—still seen as a crime—Tobie Matthew Jr. came to stay with his parents in the Archbishop’s palace and Archbishop Matthew assured colleagues that his son was just going through a rebellious phase.

Tobie Matthew Jr. never did return to Protestantism, going on to have an illustrious career as an author and translator of Catholic texts—he may even have become a Jesuit, embracing the extreme end of early modern Catholicism. When Archbishop Matthew died in 1628, he was still bitter at his son’s religious choices—noting in his will how much he had been forced to pay out to support Tobie Matthew Jr.

Archbishop Tobie Matthew’s own parents may have nodded their heads in recognition at the pain he suffered at the hands of his own son. Back in 1559, when the Protestant Queen Elizabeth had just succeeded the Catholic Mary I, a young man left his Catholic family in Bristol for Oxford University. That young man was Tobie Matthew—the future Archbishop of York—and his Catholic parents were horrified when he decided to become a Protestant minister. Matthew, of course, was convinced he was right just as Matthew Jr., knew his was the path to true salvation and happiness. Father and son were more alike than either would have liked to admit.

Featured image credit: York Minster from the Lendal Bridge. Photo by andy. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons .

The post Teenage rebellions: families divided by religion in the Reformation appeared first on OUPblog.

How the mindful brain copes with rejection

Whether it’s being left out of happy hour plans or being broken up with by a significant other, we can all relate to the pain of social rejection. Such “social pain” is consequential, undermining our physical and mental health. But how can we effectively cope with the distressing experience of being left out or ignored? Mindfulness may be an answer.

Mindfulness can be described as being “in the moment”—a tendency to direct our attention and awareness to our currently-felt internal and external sensations. Mindfulness couples such a focus on the present with an accepting, non-judgmental lens of these feelings. Instead of racing from one errand to the next, thinking only of how to complete the next task, mindful individuals stay focused on the here-and-now. They allow feelings like the stress of getting everything done to wax and wane, without interpreting them as “good” or “bad.”

Several studies have shown that mindful people tend not to experience the sting of rejection as acutely as others. However, we don’t really understand how mindfulness buffers people against such social pain. To better understand this, we ran a study to examine the ways in which the brains of mindful people cope with rejection. In our recent study, participants completed a questionnaire that measured how mindful they typically were. A few of the items are listed below. Answer them yourself, add up the points you get, and see how mindful you are (lower scores = less mindfulness):

1. I rush through activities without being really attentive to them.

____1 – Almost always ____2 – Somewhat frequently ____3 – Almost never

2. I snack without being aware that I’m eating.

____1 – Almost always ____2 – Somewhat frequently ____3 – Almost never

3. I drive places on “automatic pilot” and then wonder why I went there.

____1 – Almost always ____2 – Somewhat frequently ____3 – Almost never

Then, participants were placed in an MRI scanner, which measured the activity of their brain while they tossed a virtual ball back-and-forth with two other people. After a few minutes of ball-tossing, participants’ partners (who were actually computer programs) stopped tossing the ball to them and just passed it back and forth. Being left out of something as simple as a game of catch can evoke strong feelings of distress, which participants confirmed when they largely agreed with statements like, “I felt like an outsider during the game.”

Supporting the ability of mindfulness to buffer people against the sting of rejection, we found that mindful individuals reported less distress because they were left out of the ball-tossing game. We then looked at brain activity while participants were watching the ball whiz back-and-forth between their partners. During such social rejection, more mindful participants exhibited less activity in a specific part of the brain—the ventrolateral prefrontal cortex, or VLPFC. The VLPFC helps us regulate our feelings in a deliberate manner. For example, it would help us stifle a laugh at a funeral or allow us to interpret a racing heartbeat during a date as a sign that we are excited instead of scared. However, the VLPFC cannot perform these emotion-regulating functions indefinitely. By recruiting less of the VLPFC during rejection, mindful individuals appear to avoid excessively taxing this important regulatory resource.

Mindfulness can be described as being “in the moment”—a tendency to direct our attention and awareness to our currently-felt internal and external sensations.

So can we reap these distress-reducing benefits for ourselves? It’s still far too early to say that mindfulness is the cure to rejection’s sting. However, if our results are supported by other studies, they point to the potential for mindfulness to help us cope with feeling left out and turned down by others. By focusing our awareness on our present feelings without judging those feelings as inherently negative or positive, we may be able to better cope with rejection. Our study suggests that this beneficial coping strategy may be due to the lower burden that mindful responses to rejection places on the parts of our brain that promote effective emotion-regulation.

Featured image credit: Person on mountain by Milan Popovic. CC0 via Unsplash.

The post How the mindful brain copes with rejection appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers