Oxford University Press's Blog, page 227

September 20, 2018

Does TCJA Tax Churches? Should It?

Does the new federal tax law, commonly known as the Tax Cut and Jobs Act (TCJA), tax churches as some have argued? If so, is this tax appropriate?

The answers are “yes” and “yes.” The TCJA provisions taxing qualified transportation fringes treat secular and religious employers alike, including houses of worship. In a world of imperfect choices, the TCJA reasonably treats all employers fairly without entangling church and state inordinately.

Churches (including all houses of worship such as synagogues, temples and mosques) pay more taxes than many people believe. Churches do not pay property taxes or basic income taxes. But churches do pay the employer portion of federal social security (FICA) taxes for their non-clergy employees. Churches also often pay or collect state sales taxes on the tangible personal property they sell or purchase. In most states, churches also pay real estate conveyance taxes like other real estate purchasers and sellers.

Most importantly for the issue of the TCJA, churches, like other nonprofit institutions, are subject to federal and state taxes on unrelated business income (UBIT). Under the UBIT, a nonprofit corporation which is otherwise income tax-exempt under the Internal Revenue Code pays corporate income taxes on any business the corporation runs if such business is unrelated to the purpose of the corporation’s tax-exemption. In practice, few churches pay the UBIT perhaps because they avoid generating unrelated business income or because of lax enforcement of the UBIT–or perhaps for both reasons.

The drafters of the TCJA correctly took aim at certain fringe benefits including “qualified transportation fringes” such as employer-provided parking and transit passes. The proper way to tax these fringe benefits is to include them in the employee’s gross income as part of her compensation. Unwilling to go this far, the drafters of TCJA instead denied employers an income tax deduction for these fringe benefits. Thus, if a corporate employee excludes $100 from her salary for an employer-sponsored transit pass to take a commuter train to work, under TCJA, the employer cannot deduct this $100. With TCJA’s corporate tax rate set at 21%, the employer thus pays $21 to the federal treasury to offset the tax advantage to the employee who can exclude the entire $100 in transit benefits from her gross income.

However, denying a deduction is meaningless to a nonprofit employer which does not pay general income taxes. Accordingly, the drafters of TCJA decided that, when a nonprofit employer provides these qualified transportation fringe benefits, that amount will be considered UBIT to the tax-exempt employer. Thus, a tax-exempt employer whose employee excludes $100 in salary for a transit pass will pay the same $21 tax on this excluded amount as does a taxable employer.

This is the source of the complaint that the TCJA taxes churches. Churches have been subject to UBIT, though few in practice have paid it. A church (like any other nonprofit employer which previously did not owe the UBIT) will now pay UBIT if the church provides its employees with qualified transportation fringes including free parking and commuter transit passes.

The complaint, moreover, is not just that churches must now pay the UBIT on the parking and other transportation fringes they provide to their employees. For many churches, the greater expense will be the cost of the legal and accounting services they must obtain to comply with the UBIT.

Whether to tax churches and church personnel involves the imperfect trade-offs inherent in most tax policy choices. In terms of the First Amendment’s Free Exercise clause, it is desirable to minimize church-state entanglement. Taxation can be very entangling. This helps to explain why churches are not taxed on their church-related properties or on their general income. Such tax-exemption minimizes church-state entanglement.

On the other hand, it is unfair and inefficient for a church employee who receives a transit pass or an employer-provided parking place to get favorable tax treatment not available to secular employers and their personnel. Churches use public services like other employers and institutions. All tax policy choices involve such conflicting considerations as the revenue government needs to provide public services and fairness among similarly-situated taxpayers.

The TCJA strikes a reasonable balance, similar to the tax treatment of churches under the FICA, sales and real estate convenience taxes. Moreover, the IRS can simplify compliance with the TCJA-based UBIT for churches and other nonprofit institutions. The IRS could develop a simple form for churches and other nonprofits which only owe the new TCJA tax. This simple form would not impose on churches the cost and complexity of complying with the longer UBIT form (990-T) when it is not applicable.

Much parking provided to church employees has no fair market value since such parking is also available for free to other users such as congregants and visitors to the church. The IRS could clarify that, in such cases, the church (or any other nonprofit entity) owes no UBIT since there is no charge for the parking the church provides for free to all.

In contrast, under the TCJA, my employer, Yeshiva University, must pay the 21% UBIT on the cash amounts I exclude from my gross income for my employer-provided transit pass. Congress should have included these amounts in my gross income. The TCJA, which taxes my employer instead, is a second best alternative.

The TCJA provisions pertaining to qualified transportation fringes treat secular and religious employers alike. Compliance for churches and other nonprofit organizations can be simplified by the IRS developing an abridged UBIT return for entities which only owe UBIT on qualified transportation fringes.

In a world of imperfect choices, the TCJA reasonably treats all employers fairly without entangling church and state inordinately.

The post Does TCJA Tax Churches? Should It? appeared first on OUPblog.

Is Mars still alive?

Less than 50 days after this year’s World Space Week (4-10 October)—a global network of over 1,000 space-related organizations celebrating the role space plays in bringing the world together for peaceful purposes—NASA’s InSight spacecraft is scheduled to land near the Red Planet’s equator to take the planet’s pulse. As NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine said in an agency video tweet, “This is an important mission not just for the United States but an important mission for the world, so we can better understand why planets change and ultimately understand even more about our own planet.”

InSight (short for Interior Exploration using Seismic Investigations, Geodesy and Heat Transport) launched on 5 May 2018 aboard an Atlas rocket from California’s Vandenberg Air Force Base—only about three months before Mars approached within 56 million kilometres of Earth (the closest the two planets had come to each other in almost 60,000 years, and a record that will stand until 28 August 2287).

Scheduled to land on 26 November 2018, InSight is targeted to alight on a broad flat plain near the Elysium volcanic province (the second largest on Mars), where eruptive activity has continued until the very recent past and may likely still be volcanically active today. If successful, InSight will become the first outer space robotic explorer to study the interior of Mars, providing clues as to the planet’s origins and present state of geologic activity; no other craft sent to Mars has done this.

Image credit: An artist’s concept portrays a NASA Mars Exploration Rover (Opportunity and Spirit) on the surface of Mars, February 2003 by NASA. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: An artist’s concept portrays a NASA Mars Exploration Rover (Opportunity and Spirit) on the surface of Mars, February 2003 by NASA. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Still, challenges lay ahead. The lander will arrive only five months after one of the most intense dust storms ever recorded erupted on Mars, which completely engulfed the Red Planet and forced NASA’s solar-powered Opportunity rover to be placed in “survival (low-power) mode” to conserve energy. Although the storm began to subside in late July, as of this writing, NASA has yet to re-establish contact with the golf-cart-size rover, which has been operating on the surface of Mars for the past 15 years; scientists fear that the intensity of the storm, which all but obliterated the Sun from the sky, may have fully starved Opportunity’s solar panels of power—two months is a long time to be without being able to recharge its batteries, but optimism still prevails. This dramatic event serves as a reminder of the dangers future space pioneers will face when the time comes for them to explore Mars.

Residual dust may still be in the air when InSight lands, which is not guaranteed; the descent through the thin Martian atmosphere is so difficult that some landing attempts have been known as “seven minutes of terror.” For instance, the European Space Agency’s Schiaparelli lander made it to the surface in October 2016—but not the way it was intended: a computer glitch caused the craft to drop from a height of 2 to 4 kilometres at a speed of 540 kilometres per hour and impact the surface where it likely exploded.

Given good fortune, InSight, a stationary lander, will spend 738 Earth days (a little more than one Martian year) studying the interior of Mars (NASA’s five previous landers have literally only scratched the surface). Thus, InSight will be the first to sense and study the “vital signs” of Mars far below the surface. Using a 2.4-metre-long arm, the lander will dig 10 to 16 feet deep into the crust, penetrating the surface 15 times deeper than any previous Martian mission. The lander will then use a suite of instruments able to detect seismic activity and analyse the subsurface by studying the thickness and size of Mars’ core, mantle, and crust, as well as the rate at which heat escapes from the planet’s interior. These data will provide not only a glimpse into the evolutionary process that helped shape Mars, but of all the rocky planets in the inner Solar System, including Earth.

Image credit: Sharpest photo ever taken of Mars from Earth, 24 August 2003. Taken by the Advanced Camera for Surveys aboard NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: Sharpest photo ever taken of Mars from Earth, 24 August 2003. Taken by the Advanced Camera for Surveys aboard NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.InSight will also monitor the frequency of ongoing meteorite impacts. This data is important as Mars is closer than Earth to the Asteroid Belt (and has a thinner atmosphere than Earth’s). Thus, knowing the frequency, size, and location of impacts will help in the assessment of potential threats to future colonists on Mars (and how to protect them).

The prospect of sending humans to Mars is on the near horizon. NASA’s current goals include sending humans to an asteroid by 2025 and Mars in the 2030s. Tens of thousands of scientists from fifteen countries have supported the use of the International Space Station’s laboratories to prove the technologies needed for a mission to Mars: these include investigating the Solar Electric Propulsion needed to send cargo to Mars; establishing a communications system (which will utilise geostationary satellites over future Mars colonies, another in orbit around the Sun, as well as compatible ground stations on Earth); and studying long-term effects of the space environment on the human body. Other future missions, like NASA’s Mars 2020 rover, will not only seek out signs of habitable conditions on Mars in the ancient past, but also search for signs of past microbial life itself.

Meanwhile, engineers and scientists around the country are working feverishly to develop the technologies astronauts will use to one day live and work on Mars, including how to extract water from the soil and any underground reservoirs to create a sustained presence in the extreme Martian environment. Like early European settlers coming to America, planetary pioneers will not be able to take everything they need, so many supplies will need to be gathered and made on site.

The concept focuses on how to turn a planetary body’s atmosphere and dusty soils into everything from building materials for shelters on Mars to rocket fuel for the trip back and safely return home from the next giant leap for humanity. Such dreams bring further hope to international interests in Mars, where a global community can coexist for peaceful purposes — if not for the benefit of science, but for the survival of and expansion of humanity as we explore new worlds in the tradition of the great ocean faring navigators of our past.

Featured Image credit: An artist’s rendition of the InSight lander operating on the surface of Mars by NASA. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Is Mars still alive? appeared first on OUPblog.

Spotify Playlist: Broadway tunes in pop culture

Popular singers have been covering Broadway for years, introducing show tunes into the mainstream of music. These covers have popularized iconic Broadway tunes and broadcasted show tunes to a larger audience beyond Broadway. To rightly honor this, we’ve compiled a playlist of some of our favorite Broadway covers, featuring Frank Sinatra, Barbra Streisand, and more.

Featured image credit: Vintage Transmission by Darren Cowley. Public domain via Flickr .

The post Spotify Playlist: Broadway tunes in pop culture appeared first on OUPblog.

September 19, 2018

Blood is thicker than water

Not too long ago (12 October 2016), I wrote a post about the etymology of the verb bless and decided that my next topic would be blood, because bless and blood meet, even if in an obscure way. But more pressing business—the origin of liver (21 March 2018) and kidney (11 April 2018)—prevented me from meeting that self-imposed deadline. Today, Dracula-like, I am ready to tackle blood.

The pronunciation of this word deserves our attention as much as its origin. Blood is a parade example of the unpredictability of English spelling. It has once been calculated that the vowel we hear in blood can be spelled in five ways: with the letter u (cut, but, run), with the letter o (come, some), with the group ou (double, trouble, enough), with the group oe (apparently, in one word: does), and with oo (in blood and flood). To this I would like to add one and once, which, in principle, go with come and some but have a nice initial sound at the beginning.

Blood is raw. Image credit: “Blood Knife Kill Murder Red” by Twighlightzone. CC0 via Pixabay.

Blood is raw. Image credit: “Blood Knife Kill Murder Red” by Twighlightzone. CC0 via Pixabay.The pronunciation of blood is the product of a long and partly erratic process. In Old English, the word had a closed long vowel (blōd). The attribute “closed” is important, because later, in Middle English, closed o coexisted with open long o, as in stōn “stone.” (“Closed” and “open” refer to the movement of the lower jaw: open your mouth wide, and the vowel will also be open). Still later, by the Great Vowel Shift, closed ō changed to long u (ū), the sound we now have in school. Therefore, blood should have rhymed with mood, but it does not, because, instead or remaining long, this ū became short, and in early Modern English, quite regularly, changed to the vowel we still have in blood. It is the shortening that has never been explained, even though it occurred in numerous words, for instance, in good, book, cook, hood, look, and others in which the spelling with a double letter (oo) still reminds us of the pronunciation in Middle English. Elsewhere, only an etymological dictionary can inform us that the vowel was long—so in done, glove, month, stud, and many others.

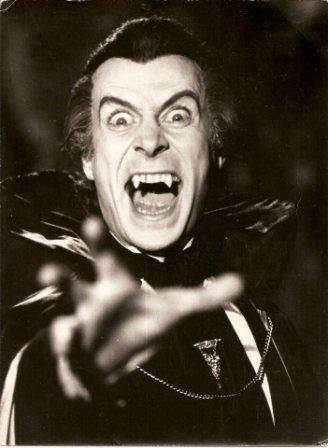

The best blood expert in the world. Image credit: Gianni Lunadei interpretando al Conde Drácula, en una versión televisiva del año 1980 by Alejandro Lunadei. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The best blood expert in the world. Image credit: Gianni Lunadei interpretando al Conde Drácula, en una versión televisiva del año 1980 by Alejandro Lunadei. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.While discussing the etymology of liver and kidney, I mentioned briefly how researchers try to reconstruct the most ancient meanings of such words. One cannot imagine that millennia ago people knew the function of our organs. For example, if my hypothesis about brain is correct (see the post 21 February 2007), brain is related to bran: just a mass. Liver was probably first and foremost a part of the slaughtered animal used for food (hence the name, as explained in the old post), and so on.

No word for “blood” common to all the speakers of the Indo-European languages existed, though some covered a large territory. Such is the Slavic word (Russian krov’, and so forth), with cognates far and wide. It is related to Engl. raw, from hrēaw, and by the same token to Latin crūdus, from which English has crude. Why raw and crude? Because the words in question referred to raw meat and other objects with blood dripping from them (for example, bloody weapon). Our remote ancestors needed words for various “kinds” of blood, rather than the generic term.

In English, blood is such a generic term, while gore is clotted blood, from a word for “filth” (thus, blood shed and coagulated). Old English had a corresponding pair: blōd and heolfor. Heolfor occurs in Beowulf. The Danes go to Grendel’s former habitat, and on their way they see a pool full of heolfor, the stagnant blood of Grendel’s old victims. The word has related forms in Classical Greek and Sanskrit. They mean “spot, dirt.” German, too, once had a close congener. Strangely, the word did not stay even in archaic dialects. In English, it was supplanted by gore.

Blue blood. Image credit: Le bal paré by Antoine-Jean Duclos. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Blue blood. Image credit: Le bal paré by Antoine-Jean Duclos. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. Red blood. Image credit: “Blood Vial Analysis Laboratory Test Medical” by PublicDomainPictures. CC0 via Pixabay.

Red blood. Image credit: “Blood Vial Analysis Laboratory Test Medical” by PublicDomainPictures. CC0 via Pixabay.Still another Old English word relevant to our story is drēor. The adjective drēorig “bloody” has yielded Modern Engl. dreary “bleak; lifeless,” traditionally rhyming with weary, the very opposite of sanguine. (Of the three extant Latin words for “blood” English speakers will immediately recognize only sanguis, because of sanguine. In the Middle Ages, an excess of blood was believed to make one cheerful.)

Given so much specialization, it does not come as a surprise that the origin of most words for “blood” has not been discovered. An additional difficulty consists in that some of such words could have a ritual meaning (“the blood of a sacrificial animal”) and be subject to taboo. There have been many attempts to connect blood with Old Engl. blōtan “to sacrifice” (this is where bless came in in my old post), and many people still share this etymology.

Blood is a word common to all the Germanic languages, but only to them. It is very old because Gothic, which was recorded in the fourth century, already had it. No phonetic variations have been recorded, except for those that are “regular” (Gothic bloþ, German Blut, etc.), and the meaning is the same everywhere. The fewer variants, the harder it is to trace the word’s distant past. We can only risk the hypothesis that the last consonant (such as þ in Gothic) belongs to an old past participle. All the rest is guesswork, and, characteristically, even the conjectures about the etymology of blood are few.

William Harvey (1578-1657), the physisian who discovered the phenomenon of blood circulation. Image credit: William Harvey by Daniël Mijtens. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

William Harvey (1578-1657), the physisian who discovered the phenomenon of blood circulation. Image credit: William Harvey by Daniël Mijtens. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Those sources that don’t say origin unknown suggest that the root of blood is the same as in blossom and bloom. English still has the archaic verb blow “to bloom, flourish.” The ancient root seems to have meant “swell, puff up; gush” (no connection with blow, as in to give a blow). If this etymology is correct, perhaps the inspiration for our word was the picture of the blood flowing from a wound. Conversely, if we start from the idea suggested by the phrase to be in full bloom, perhaps the word referred to the red color of the substance people shed so freely. One thing is rather clear: the generic sense of a word for “blood” is always a late development.

As noted above, the use of sacrificial blood might result in tabuistic coinages, that is, instead of calling blood by its name, people invented harmless synonyms, for instance, “a thing flown.” We remember that much later references to blood were deemed sacrilegious. Hence the oath ’sblood (that is, His blood), known from Shakespeare, and the once unpronounceable adjective bloody, immortalized by George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion.

Featured Image: “A Glass Of Water Color Ink Blood Red Dissolved” by frolicsomepl. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Blood is thicker than water appeared first on OUPblog.

September 18, 2018

Northeast India: a new literary region for IWE

It’s a young literature – this body of English writings from the eight states of India’s Northeast. Often evaluated in comparison with the rich tradition of Assamese literature (from the largest state in the region and going back several centuries) and overshadowed by the growing dominance of a ‘mainstream India-centred’ Indian writing in English, it began to emerge into the literary-critical scene at the turn of the 20th century, without a splash and with extreme modesty. A few texts here and there – like Arup Dutta’s children’s classic The Kaziranga Trail (1979) – seemed almost accidental, until we suddenly realised its presence in our midst. From one or two books on the shelf of The Modern Book Depot in Guwahati, to a row, to a wall, and now to a whole new extension – Easterine Kire, Temsula Ao, Mitra Phukan, Dhruva Hazarika, Mamang Dai, and the poets Robin Ngangom, Desmond Kharmawphlang, Kynpham Singh Nongkynrih, Esther Syiem, and Mona Zote are now not just popular reading, but have become subject of serious research. And Siddharth Deb, Anjum Hasan, Janice Pariat, and Kaushik Barua, a new generation with quicksilver imagination, supple language, rooted and contemporary, have made sure that this is a literature that is here to stay.

But how perfectly logical that it should have emerged! The recipe was there, the conditions were right, but then, of course, the region was invisible, except through the lens of the stereotype. The exotic, the mysterious, the simple, the lazy, richly endowed with natural resources, animistic, beautiful, untouched and unknown (the first modern historian of the region, Edward Gait, declared that little was known in the rest of India about it), – the catalogue is colonial but the stereotypes continue in other guises in the present. At the same time, it was a region of intense missionary activity, especially in education, and this resulted in the English proficiency that began to be noticed way before the English writings came on the scene.

However, it still needed that catalyst – or a catalytic time – that would jumpstart literary work. And this came in the shape of a time, a discourse, and a set of events. The time was roughly the 1980s when a number of identity movements began in the region around issues of territory (though the Naga secessionist movement dates back to the 1950s). The discourse was one of difference built around some of those stereotypes and directed externally to the Indian state and internally among the larger and smaller linguistic communities. The set of events included prominent ones like the students’ movement against illegal immigrants and outsiders and student and government action aligned to it (spawning similar movements all over the region) and long-running suspicion and mistreatment of students from the Northeast in Delhi and other metropolises often resulting in cruel beatings and deaths. A writer’s universe – richly historical, tragic, primeval and deeply rooted and ultra-modern!

Easterine Kire has evoked this complex universe in poetry, children’s fiction and novels that map changes in Naga society as it has moved from the 19th century into the 21st. From A Terrible Matriarchy, published in 2007, on the lives of three generations of women during a crucial period in Naga history, to the recent A Respectable Woman, 2018, set in the wake of Japanese retreat from the area after the Second World War, or the early A Naga Village Remembered (1982) on resistance to British invasion in 1879 and the lyrical When the River Sleeps (2014) on a spiritual quest this is a body of work that is both rooted and cosmopolitan. Temsula Ao’s sensitive little tale, ‘A Pot Maker’ represents the sensuous, tactile experience of moulding wet clay as a craft handed down from practitioner to inheritor, mother to daughter in a cameo of Indian craft traditions.

In fact, Shillong has been the catalytic place in many ways, a charming, childhood milieu for many of these writers, whose poetry and fiction is a continuing effort to understand its present against its idyllic past.

Political violence and recovery in a turn to nature and traditional culture, myths and land, local performance traditions and a long tradition of Western popular music – many of these are captured by writers here. And the special place of Shillong in this heady mix has been crucial. Writers who grew up in its special atmosphere have evoked it in fine novels of nostalgia and longing. In fact, Shillong has been the catalytic place in many ways, a charming, childhood milieu for many of these writers, whose poetry and fiction is a continuing effort to understand its present against its idyllic past. In the process, the writing has matured and moved – from small hill station to the metropolises of the world – at home equally in Bangalore or Rome. From her first, very local Shillong novel, Lunatic in my Head (2007) to The Cosmopolitans (2015), Anjum Hasan represents this journey, though she is only the most well-known of a very fine bunch of new writers.

And then, of course, there is Kaushik Barua. He announced his arrival on the literary scene with Windhorse (2013), shaking off local NE origins to tell, with delicate empathy, the story of people fighting in the Tibetan resistance. And as his second novel No Direction Rome (2018) proves, he is unwilling to get slotted, telling a crazy, dark and funny tale that is completely different in style and sensibility from the first but with the same human sympathy.

So – NE English writing coming into its own.

Featured image credit: Books by Tom Hermans. Public domain via Unsplash.

The post Northeast India: a new literary region for IWE appeared first on OUPblog.

Re-thinking post-war theatre architecture

The official opening on 14 June 2018 by the Queen and Duchess of Sussex of Chester’s new cultural ‘hub’, Storyhouse, offers a timely moment to consider the theatre as a building type. Storyhouse is an interesting re-thinking of what an Arts building can be. It combines a theatre, cinema, library, and café, in an attempt to break down boundaries between artistic and institutional structures. These facilities are housed within a 1930s former Odeon cinema, which has been significantly reworked and extended. The distinctions between the building’s functions are deliberately blurred. Library books, for example, are found throughout the foyer spaces, which feel anything but ‘institutional’.

Storyhouse’s intentions are explicitly democratic. It aims to appeal to a broad public. In this respect, it can be seen as the latest example in a long-running history, dating back to the 1940s. In the middle of that decade, public subsidy was directed to the performing arts for the first time. The Arts Council of Great Britain was founded in 1946. In the case of theatre, its interest was largely the country’s ‘repertory’ theatres, which presented a mixed programme of what seemed to those holding the purse-strings to be culturally worthwhile productions. Local government was then given the power routinely to subsidize the performing arts in 1948. Its support could be directed not only to individuals and organizations, but also to the construction and maintenance of buildings. The result was something new in Britain: the civic theatre.

During the 1950s and 1960s, the amount of public money spent on theatre (and theatre architecture) in Britain gradually increased. The election of a Labour government under Harold Wilson in 1964 led to a significant rise in spending, with Britain gaining its first Minister for the Arts, Jennie Lee. For Lee, it was critical that as many people as possible should have access to what she considered ‘the best’ of the arts. Her aim was essentially an education in taste and, by extension, a transformation in peoples’ outlook. While subsidy was usually only a small part of a theatre’s income, the Arts, in effect, were cast as the cultural element of an ever-evolving Welfare State.

Image credit: Dundee Repertory Theatre: a late example of the theatre-building boom, opened in 1982. Photo courtesy of Alistair Fair, used with permission.

Image credit: Dundee Repertory Theatre: a late example of the theatre-building boom, opened in 1982. Photo courtesy of Alistair Fair, used with permission.In some ways, Lee’s view of excellence was a relatively narrow one, and it might now be questioned. However, it catalysed a spate of theatre-building which lasted until the early 1980s. The new British theatres of this period reflected a range of agendas and ideas. An important debate related to the nature of performance space, and the optimum relationship between actor and audience. How could the three-dimensional, ‘live’ qualities of theatre be emphasized in order to distinguish it from cinema and television? How could new approaches to set design be best accommodated on stage? What sort of auditorium was the most ‘democratic’, with good sightlines and acoustics for all?

At the same time, the involvement of central and local government in supporting the Arts means that the theatre architecture of this period can also be understood in terms of various broader debates. For example, the potential was often mentioned for theatres to embody and enhance civic pride within towns and cities whose centres were frequently being modernized. To some extent, these buildings took a role previously performed by town halls and railway stations, connoting modernity and status. Theatres were often conceived in ‘urban’ terms: how would they animate town and city centres? Should they be located among civic buildings, where their prestige might be easily understood? Or were less overtly civic locations, perhaps in shopping centres, more appropriate? Another strand of debate related to the idea of the building itself. How could the forms and materials of modern architecture be used to suggest a new image of theatre, one which reflected the intention that it be available to everyone and which avoided elitist monumentality?

In answering these questions, a diverse range of buildings was created, in locations from Plymouth to Inverness, Aberystwyth to Ipswich. Visionary theatre directors worked with committed politicians, talented architects, and expert technicians to consider what a modern theatre could be. Many striking buildings were constructed. One task of the historian is to explain the forms these buildings took. However, just as important are the ideas, processes, and collaborations which made these buildings possible, and the publications, exhibitions, and professional organisations which shaped the debates.

Of course, there have been important developments since the 1980s, not least in terms of community participation and the extent to which theatre genuinely reflects the population it serves. In addition, theatre now takes place in a growing range of spaces. The National Theatre of Scotland, indeed, has eschewed architecture entirely: its travelling operation contrasts with the concrete solidity of the National Theatre in London, opened in 1976. Yet, as Storyhouse reveals, buildings for performance remain important and revealing. Just as Storyhouse allows us productively to question the role and place of theatre in the 21st century city, so Britain’s post-war theatres allow us to tell new stories about the country’s social, urban, and political histories during an optimistic period in which anything seemed possible.

Featured image credit: Storyhouse, Chester. Photo courtesy of Alistair Fair, used with permission.

The post Re-thinking post-war theatre architecture appeared first on OUPblog.

September 17, 2018

Was it right to pass Israel’s Nation-State Basic Law?

Recently, Israel’s Knesset passed by a 62-55 margin, Basic Law: Nation-State. Israel does not have a formal constitution, but rather a set of basic laws with quasi-constitutional status. Among these basic laws are those that deal with structural issues, as well as those that anchor human and civil rights. The new basic law anchors the definition of Israel as the nation-state of the Jewish people, a definition that has never been regarded as controversial, and enumerates its language, symbols, anthem and other fundamental matters.

The legislation aroused a lively public debate and much interest in the international press. In this brief post, I will lay out some of the arguments against the Basic Law and evaluate them.

Argument 1: The nation-state itself is a bad idea

This claim is backed by historical and moral arguments. The historical view argues that the nation-state can easily descend into fascism. Morally, the argument is that the nation-state, by definition, discriminates between citizens and turns those citizens who are not members of the nation into second-class citizens.

However, this argument is easily refuted as the right to self-determination in a nation-state is recognized and anchored in international human rights documents. Many western states are nation-states, and their number has only increased with the collapse of many multi-national states since the end of the Cold War. In fact, the most virulent opponents of Israel as a Jewish nation-state support the right of Palestinians to a nation-state of their own, and thus do not actually object to the principle as such.

The new basic law anchors the definition of Israel as the nation-state of the Jewish people, a definition that has never been regarded as controversial, and enumerates its language, symbols, anthem and other fundamental matters.

Argument 2: The Jewish people have no right to a nation-state

This argument comes in two versions. In the first, Judaism is not a national identity, and therefore the Jews have no right to a nation-state. In the second, even if the Jews are a nation, they have no claim to the Land of Israel and have no right to self-determination within its borders.

The former is supported by the argument that nationalism is a purely modern phenomenon with no basis in human history. As far as the modernist school is concerned, not only the Jews, but all nations were “imagined” or created within the past two centuries.

Of course, this claim is hotly contested. Moreover, in the specific case of the Jews, modernists have to jump through hoops to defend their thesis. In contrast, non-modernists like Hastings and Smith can point to the Jews as the model of pre-modern nationalism.

The right of the Jews for self-determination specifically in their historic homeland seems obvious and has been internationally recognized, but I shall not belabor this point here.

Argument 3: There is no need to enshrine Israel’s national status in a Basic Law

Those who criticize the Basic Law claim that Israel’s status as a Jewish nation-state is already anchored in various laws, and thus has no need to be upgraded to a constitutional level.

This argument doesn’t hold water. In nation-states, constitutions typically anchor the national character of the state. This anchoring is not redundant because it strengthens the status of similar principles found in regular statutes.

The need to anchor Israel’s nation-state status in a Basic Law is no different than the need to anchor human rights in two Basic Laws in 1992, despite ample existing laws and jurisprudence protecting such rights.

Argument 4: The Basic Law will legitimize the original sin of the “Constitutional Revolution”

The “Constitutional Revolution”—which took place in 1992 with the legislation of the two aforementioned Basic Laws—turned Israel from a parliamentary democracy into a constitutional one in a hasty and problematic manner. Thus, it could be argued that the passage of this new basic law, with the support of opponents of the revolution, signals acceptance of the revolution despite its deficiencies.

This argument is overstated. The Constitutional Revolution took place over twenty years ago, and the moral force of the opposition to the Supreme Court’s conduct has, in any event, faded with the passage of time, so that passing a new Basic Law hardly matters.

Argument 5: There is no consensus

While an ordinary law that enjoys legitimacy even if passed by a small majority, the legitimacy of a constitution depends on (among other things) a public consensus in its favor. Of course, complete unanimity is impossible, but widespread public support is necessary.

The principles included in Israel’s Basic Law: Nation-State are justified. These principles should be included in a constitution alongside structural principles and a commitment to protecting human rights. Yet, while this is a good law and I’m pleased that it passed, I regret that it did so with a slim majority and in retrospect would have preferred that passage of the law be postponed until a wider consensus could be achieved.

Featured image credit: Dome of the Rock by bluskyhi. CC0 via Canva.

The post Was it right to pass Israel’s Nation-State Basic Law? appeared first on OUPblog.

September 16, 2018

Beyond “The Brady Bunch:” stepfamilies in later life

When we think about stepfamilies, images of the perennially popular TV show The Brady Bunch likely spring to mind. Young single parents unite in marriage, bringing together their children from prior unions to form a stepfamily. Mike and Carol Brady presumably lived happily ever after, with their remarriage persisting into old age and ending only upon death of one of the spouses. However, images of stepfamilies headed by older adults are relatively rare in the media. Likewise, scholarship on families in later life also overlooked stepfamilies.

To mark National Stepfamily Day on 16 September to celebrate and support stepfamilies nationwide, we discuss key findings from our recent study charting the terrain of the stepfamily landscape during older adulthood. There are two main paths to stepfamily living for elders. Some of these stepfamilies were formed earlier in the life course and have persisted for decades. Others are unions formed more recently during later life and typically involve non-resident adult children.

Family demographic trends during the second half of life suggest that stepfamilies may be increasingly common among older adults. The doubling of the gray divorce rate, which refers to divorce among persons aged 50 and older, is contributing to the rise in single older adults who are eligible to form a remarriage or cohabitation. Those whose marriage dissolve through gray divorce are more likely to repartner than those who become widowed. Unmarried cohabitation among older adults has accelerated, quadrupling from less than 1 million to 4 million persons from 2000 to 2016. Remarriage is also more common. Just 19% of older married adults were in a higher-older marriage in 1980 whereas by 2015 the share had climbed to 30%.

In short, today’s older adults are more likely to be remarried or cohabiting than were their predecessors. Regardless of whether they are remarried or cohabiting, most of these individuals have children from previous relationships, foretelling a sizable share of older adults in stepfamilies.

We drew on national data from the 2012 Health and Retirement Study to establish a portrait of stepfamilies in later life. Nearly half of middle-aged and older (i.e., aged 50+) couples with children are in stepfamilies. That is, one or both of the spouse/partners is not the biological or adoptive parent of the other’s child(ren). Most older adult stepfamilies are headed by married couples (86%), but 14% are cohabiting couples. This union type distinction is important because married and cohabiting stepfamilies are unique in their stepfamily structure. Couples in married stepfamilies more often have children together (forming a blended stepfamily), whereas cohabiting stepfamilies more often include children from both partners’ previous relationships but lack a shared child.

Family demographic trends during the second half of life suggest that stepfamilies may be increasingly common among older adults.

Married and cohabiting stepfamilies also differ across social, economic, and health indictors. Those in married stepfamilies enjoy greater economic resources and better health, on average, compared with older adults in cohabiting stepfamilies. Still, individuals in both types of stepfamilies fare worse on these and other dimensions than their counterparts who are married and have only share biological or adopted children together. These patterns mirror those observed among younger families with children in which married two biological parent families tend to exhibit the best outcomes, followed by married stepfamilies, and lastly cohabiting stepfamilies.

Despite their social, economic, and health disadvantages, older couples in cohabiting stepfamilies report relationship quality that is comparable with that of older couples in married stepfamilies. Moreover, couple relationship quality in stepfamilies is similar regardless of whether one or both partners have children from previous relationships or whether the couple have a shared child. The negligible role of stepfamily configuration in couple relationship quality is somewhat surprising since children are a major source of relationship strain in stepfamilies. However, given that most children have grown up and left home in older stepfamilies it makes sense that stepfamily structure is not a salient factor in couple relationship quality in later life.

Stepfamilies are already commonplace among older adults and this trend is likely to grow in the coming years. Nearly half of older couples have stepchildren, meaning they are part of stepfamilies. Older stepfamily couples have fewer resources and confront more health problems than do couples without stepchildren, raising important questions about how adults in stepfamilies navigate old age. Stepchildren may be less willing to provide support or care for stepparents than biological parents. Stepparent-stepchild dynamics might create additional stress for stepfamily couples. The high prevalence of stepfamilies in later life should encourage greater research and policy attention to stepfamily functioning and its implications for health and well-being in later life.

As we celebrate National Stepfamily Day, let’s be sure to encompass all stepfamilies, young and old alike. By moving beyond the stereotypical Brady Bunch stepfamily with young parents and school-aged children, we can shine a light on stepfamilies maintained and formed during the second half of life.

Featured image credit: Multi-generation family having fun together outdoors by Monkey Business Images. Licensed image via Shutterstock.

The post Beyond “The Brady Bunch:” stepfamilies in later life appeared first on OUPblog.

Not your grandmother’s women’s lib movement: Femen’s uncivil disobedience

Oksana Shachko died on 23 July 2018. She co-founded the feminist socialist collective Femen in her native Ukraine ten years ago, to fight against patriarchy’s three central forms—dictatorship, the sexual exploitation of women, and established religion. One of Femen’s first protests was a guerrilla theater performance protesting sexual harassment at the university. Soon thereafter, Femen discovered its distinct “weapon”: bare breasts. Femen “hijacked” the Euro Cup of men’s football in Kyiv to protest against sex tourism, they “kidnapped” a baby Jesus from a nativity scene in the Vatican, and “ambushed” Russian President Putin at the Hanover trade fair in 2013. They did all this topless, with slogans painted on their young bodies, magnetizing the spotlight.

By “weaponizing” their naked breasts, Femen activists reclaimed female nudity and asserted the right to control their bodies. Femen dubs its tactics, which include “sex attacks, sex diversions and sex sabotage,” sextremism, or “female sexuality rebelling against patriarchy.” Their nudity symbolizes freedom and autonomy. It puts patriarchy into a frenzy.

Femen members have suffered threats and physical abuse. They have been charged with indecent exposure, blasphemy, and sabotage. After staging a protest outside the KGB in Belarus in 2011, Femen activists, including Ms. Shachko, were abducted by security agents, tortured, and abandoned three days later in the woods. In Paris, where Femen is now based, they were pepper-sprayed and beaten by Catholic and nationalist protesters when they disrupted a march against planned legislation to give same-sex couples the right to marry and adopt.

Journalists and sympathizers often describe Femen’s actions as “civil disobedience.” Doing so may help to make their protests intelligible or more palatable, situating them within a venerable historical tradition associated with the likes of Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King, Jr. Yet, the classification does these feminists a disservice, taming their radicalness into an ill-fitting straightjacket.

Civil disobedience is commonly conceived as a principled, public, nonviolent, non-evasive (in that the agent accepts legal sanctions), and respectful breach of law intended to reform a law or policy. Femen’s opponents contrast their actions with supposedly exemplary campaigns of civil disobedience, such as the “whites only” lunch counter sit-ins of the early 1960s in the United States. Femen’s sex attacks consist of principled, public, and nonviolent breaches of law. But critics have a point: Femen activists seek more than legal reform; they resist arrest tooth and nail; and they thumb their nose (or nipple, in this case) at patriarchal society’s “good” mores. They epitomize a kind of uncivil disobedience.

Image credit: Femen 2 by COMBO – Own work. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: Femen 2 by COMBO – Own work. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons. When Femen cut down a large cross with a chainsaw in central Kyiv, as part of a series of “Free Pussy Riot” actions (their Russian sisters in arms having been sentenced to two years in prison for their “Punk Prayer”), they were not trying to abide by the rules of the civil disobedience playbook. They burst into a male-dominated space, destroyed a religious (and phallic) symbol, defied patriarchal norms, and provoked men. The civil disobedience playbook demands that the oppressed demonstrate their dignity to those who don’t recognize it through dignified and respectful conduct. Think of Black civil rights activists impeccably dressed in their Sunday best, thoroughly trained in and committed to nonviolence, just sitting at a restaurant counter or riding a bus, managing not to react to being insulted, spat on, slapped, beaten, kicked, fire-hosed, or brutally arrested. They sought to persuade the White majority that they deserved equal rights.

Like the Black Lives Matter slogan “Not Your Grandfather’s Civil Rights Movement,” in reaction to this kind of politics of respectability, Femen’s could be: “Not Your Grandmother’s Women’s Lib Movement.” In fact, Femen’s members are more closely aligned with now-distant feminist forbearers, the suffragettes.

At the turn of the 20th century, the suffragettes embraced well-targeted property destruction and evaded law enforcement. They smashed the windows of London’s shopping district, cut telephone and telegraph wires, burnt post boxes all over the UK, vandalized and even bombed government offices and museums, and destroyed golf course tufts with acid. Emmeline Pankhurst defended suffragists’ use of “militant methods” and characterized herself as a “soldier” in a “civil war” waged against the state. The suffragettes were seen as lacking in self-respect, “unladylike” and “mad”; they were beaten, tortured, committed to mental hospitals against their will, imprisoned, and force-fed when they undertook hunger strikes.

Femen activists, who are routinely called “sluts” and “whores” and describe themselves as “hooligans,” pursue this radical tradition. They conceive of sextremism as a “highly aggressive form of provocation,” and don’t give a fig if the majority of the public sees their actions as undignified. They deliberately flout civility, and the liberal requirement to respect and listen to one’s opponent. Femen shout down their adversaries. Their bare chests proclaim “Fuck the Church,” “Fuck Your Morals,” or “In Gay We Trust!”

Whereas civil rights activists typically submitted to arrest, pleaded guilty in court, didn’t try to excuse or justify their lawbreaking, and accepted their punishment, thereby evincing their respect for the law, the suffragettes often evaded law enforcement and decried the state’s illegitimacy. Elizabeth Cady Stanton described “the insult of being tried by men—judges, jurors, lawyers, all men—for violating the laws and constitutions of men, made for the subjugation of my sex.” Femen members likewise sometimes resist arrest and denounce the system that tries and punishes them, insisting that it isn’t owed any deference.

Branding Femen’s protests as civil disobedience misses their point, which is in part to refuse to follow the standard script of civil disobedience. Let’s call their disobedience what it is: uncivil—radical and provocative.

Featured image credit: FEMEN Ukraine is not a brothel by FEMEN Women’s Movement – Alexey Perkin. CC-by-SA-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons .

The post Not your grandmother’s women’s lib movement: Femen’s uncivil disobedience appeared first on OUPblog.

September 15, 2018

Malaria Prevention: An Economic Perspective

In 1998, the Roll Back Malaria partnership – the largest global platform in history for coordinated action towards reducing the burden of malaria – was created to fund a series of health initiatives and malaria control interventions in affected countries. However, in spite of large successes in reducing both the incidence of and fatalities from the disease, malaria remains a significant cause of morbidity and death globally. In particular, Africa is the world region with the greatest number of cases: in 2016, of the 445,000 deaths from malaria globally, 91% were in Africa.

Luckily, a number of tools and technologies are available to prevent and cure the disease. In particular, sleeping under a treated mosquito net is highly effective in preventing the disease. However, while the private returns of prevention are high, the adoption of antimalarial products and behaviors remains unfortunately too low in endemic areas.

After providing background information on infection with malaria, we present research on the beneficial impact of malaria prevention on a series of outcomes and review the explanations for the low adoption rates of prevention technologies.

BackgroundMalaria is spread by the bite of Anopheles mosquitoes infected with a protozoan parasite. Children under 5 and pregnant women are very vulnerable to infection, because they have not yet developed immunity against the infection (children under 5) and because they temporarily lose their immunity (pregnant women). Technologies to prevent malaria include insecticide-treated net (ITN) and long-lasting insecticidal net (LLIN) usage and indoor residual spraying (IRS), among others. Treated bed nets prevent mosquito biting while repelling or killing mosquitoes. While older ITNs require periodic insecticide retreatment, newer LLINs remain effective for several years without retreatment. IRS is the process of spraying the interior walls of a dwelling with insecticide.

Beneficial effects of prevention and eradicationA large economics and medical literature finds that malaria prevention and eradication have a significant effect on health and economic outcomes. Malaria prevention and eradication directly decrease mortality and improve health status and anthropometric outcomes. In addition, beyond these direct effects on health, prevention and eradication have a positive effect on education, income, wealth, and employment outcomes. Interestingly, research on the impact of prevention and eradication exploits both historical and recent data from a number of different countries, which implies that these effects are robust.

Barriers to preventionThe main reason behind the low take-up of bed nets lies in household financial constraints and high prices of bed nets. For example, treated bed nets are unaffordable to many households in sub-Saharan Africa. This implies that free distribution of bed nets (or distribution with a high subsidy) is the most promising avenue for increasing take-up. There are also other reasons why free or highly subsidized bed nets are a good strategy. First, bed net usage creates positive externalities by reducing the number of vectors of the disease. Second, there is no evidence that free distribution increases wastage on individuals who do not actually need the nets. Finally, the increased usage from free distribution and highly subsidized prices allows more individuals to learn the benefits of bed nets by using them. For all these reasons, there is a wide agreement among policymakers and researchers that bed nets should be distributed for free or at a highly subsidized price in affected areas.

In addition to financial constraints, lack of information also acts as a barrier to prevention. Information on health products is acquired not only thanks to public information campaigns, but also by using the products themselves (learning-by-doing) and by observing the preventive behavior of others (social learning). This finding implies that enabling learning and raising awareness through informational campaigns can improve preventive behaviors.

Finally, there is a growing interest in using concepts from behavioral economics to explore the role of psychological factors in malaria prevention. In particular, one recent article finds that a financial commitment mechanism (in which individuals in India commit to retreat a bed net in the future) is effective at increasing bed net retreatment. There remain ample opportunities for researchers to test insights of behavioral economics to malaria preventive behavior.

ConclusionMalaria prevalence remains high in some regions of the world (in sub-Saharan Africa in particular). Since the benefits of prevention are large and significant, and adoption of preventive behavior unfortunately too low, identifying the factors behind malaria preventive behaviors is critically important. The main barrier to malaria prevention is undoubtedly the financial constraint, and the free or highly subsidized distribution of bed nets appears to be an effective pricing strategy. However, the role of information is also significant and some psychological cues could be used to strengthen prevention. While economic research has mainly investigated demand-side factors of malaria prevention, we believe that future research should focus on the supply side. In particular, understanding logistic problems in the delivery of health products (including shortages) is a promising avenue for future research.

Featured image: An Anopheles stephensi mosquito shortly after obtaining blood from a human (the droplet of blood is expelled as a surplus). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons .

The post Malaria Prevention: An Economic Perspective appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers