Oxford University Press's Blog, page 230

September 6, 2018

Is Punk (or any alternative culture) an antidote to authoritarian, neotraditionalist nationalism?

April 30th this year marked the 40th anniversary of the massive Rock Against Racism rally and concert in London, at which some hundred thousand people marched into Victoria Park to the sound of punk and reggae bands, including X-Ray Spex, fronted by Afro-British Poly Styrene. The context in which this mass movement arose in the late 1970s UK is uncannily familiar. Police were stopping people of color on the streets under the pretext of the notorious SUS (“suspicious persons”) law. Voices once consigned to the margins of the far-right were thrust into public discourse as the Prime Minister lamented being “swamped” by immigrants. Such was the environment in which punk burst into the global spotlight in the second half of the 1970s.

Punk appealed to many people seeking a socio-cultural space radically different from the emerging authoritarian, nationalist, neo-traditionalist trends of the late 1970s and 1980s in the UK, the US, and in the authoritarian–and increasingly, nationalist and neo-traditionalist–states of communist Eastern Europe. Underground punk scenes in East Germany, Czechoslovakia, and the USSR were complemented by spectacularly visible scenes in Hungary and in Poland, where an explosive combination of martial law and a burgeoning market economy fueled a punk rock tempest. The Third World was also intertwined with the development of punk, prompting reggae superstar Bob Marley to sing of an international “Punky Reggae Party” in 1978. Punk had become a global socio-cultural revolution. Today, as countries around the world once again flirt with authoritarian, neo-traditionalist nationalism, it is worth reflecting on how punks responded to similar trends 40 years ago.

Some punks organized, creating new coalitions and embracing activism. As in the UK, US punks from Washington, D.C. to San Francisco set aside animosities and joined forces with the previous generation of radicals, including socialists and Yippies, in Rock Against Racism (and later, Rock Against Reagan). Tim Yohannan and others around the San Francisco ‘zine Maximum Rocknroll connected scenes around the world into a global progressive punk network. Meanwhile, in Eastern Europe, punks formed alliances with art impresarios, student club directors, sympathetic journalists, jazz unions, and with visiting punk and reggae musicians from the UK and Jamaica, crying out together against their respective versions of the corrupt, oppressive civilization of “Babylon”.

A more typical choice among punks than outright activism was simply embracing alternative culture, carving out ever-expanding zones of fun, freedom, camaraderie, and egalitarianism in their boring, oppressive, atomized, and hierarchical societies.

Yet, maintaining punk coalitions and activism was precarious, particularly when it brushed up against organized politics. Even punks who loved Rock Against Racism were seldom enthusiastic about its sponsor, the Socialist Workers’ Party (or Labour, for that matter), and Yohannan’s efforts to mobilize punks evoked as much criticism as acclaim. The skepticism was often mutual: in Poland, perhaps the world’s best example yet of mass activism leading to political change, the Solidarity labor union invited–then promptly disinvited–punk band Brygada Kryzys to its “Forbidden Songs” festival in 1981. Punks’ efforts to engage with the most pressing issues of their time are inspiring, but also sobering reminders of the difficulty of channeling passion into political transformation.

A more typical choice among punks than outright activism was simply embracing alternative culture, carving out ever-expanding zones of fun, freedom, camaraderie, and egalitarianism in their boring, oppressive, atomized, and hierarchical societies. DIY culture was sometimes a necessity given the difficulty of penetrating the mass culture industry in the capitalist or communist world–but it soon became an ethos for punks, from Ian MacKaye’s independent Dischord record label in Washington, DC to Eastern Europe, where lucky owners of tape recorders could record local punk bands over classical music tapes. Punks also colonized parts of the mass media in the West and the East, including in communist Poland, where listeners to state media could tune in to Republika singing to catchy synth beats about being a cog in an Orwellian machine, watch Lady Pank playfully describing martial law Warsaw as a jungle ruled by wild animals, or listen to Dezerter furiously mocking authority in “Ask a Policeman” (“He will tell you the truth”).

Punk’s history suggests the challenges and possibilities of alternative cultural movements in the world today. Cross-cultural coalitions are as important now as ever, particularly with the current global crisis, fueled by tension between disenfranchised global diaspora communities and disenfranchised rural white communities. Creating alternative cultural spaces–safe spaces, sanctuaries, and micro-cultures–that are welcoming and inclusive is another worthwhile endeavor, particularly since these can become part of a new reality, much as punk has. Ian MacKaye recently suggested that “punk won,” since punks created an enduring space for their alternative culture, becoming so deeply ingrained in society and culture that punk’s innovations are taken for granted. We might ask ourselves, what new cultural developments are emerging today that might win a lasting place in our world? With our work, today’s alternative culture may become the future’s reality.

The post Is Punk (or any alternative culture) an antidote to authoritarian, neotraditionalist nationalism? appeared first on OUPblog.

September 5, 2018

Table talk: How do you pay your dues?

To find out how you pay your dues, you have to read the whole post. It would be silly to begin with the culmination. The story will be about phonetics and table talk (first about phonetics).

Sounds in the current of speech are not separate entities the way letters are in writing, though even letters tend to stick together and form new entities: consider the ligatures Æ, æ = a + e and Œ, œ = o + e. But to return to sounds. The same ending appears as voiced or voiceless, depending on the consonant before it: bets versus beds (with beds pronounced as bedz) and backed versus bagged. The consonants t and k are voiceless, so that the ending after them has also become voiceless, while g and d are voiced, and the ending following them is voiced. For the same reason, wisdom and Osborne have become wizdom and ozborn. This process of sound adaptation in speech is called assimilation. Its rules are capricious. For instance, Gatsby has not turned into Gadzby or Gatspy. Nor has pigsty become picksty.

Pay your dues and be happy. Image credit: “euro by janeb13. CC0 via Pixabay.

Pay your dues and be happy. Image credit: “euro by janeb13. CC0 via Pixabay.In addition to being partly unpredictable, such rules vary from language to language. Best buy, when pronounced with a heavy Russian accent, deteriorates into bezd buy. This voicing is intolerable in English (probably no one knows why) but necessary in Russian: otets [stress on the second syllable] da doch’ “father and daughter” and doch’ da otets “daughter and father” sound as otedz da doch’ and dodge da otets. The Russian connection will resurface at the very end of the present post.

If you have survived this introduction, read on. Our today’s subject is the pronunciation of s, z, t, d, and ch before y, that is, before the initial sound of a word like yes. Here the assimilatory process is rampant. The title of Shakespeare’s play As You Like It is pronounced not with z in as but with the first sound of a word like genre. The same is certainly true with regard to the adjective visual, though here we observe variation even between individuals and the varieties of one language. British speakers pronounce the middle of words like Asia and equation with sh (as in patience), while in American English, the voiced sound, as in genre, is heard in this position.

An old lady from London (no, this is not the beginning of a limerick) pronounced vi-z-yual aids, and I asked her why she did so. She retorted that the pronunciation of the word with the consonant of genre is slipshod. Perhaps it was slipshod several hundred years ago, but times change, and we are expected to change with them, whether we like it or not. However, the most authoritative British pronouncing dictionary of the middle of the past century, did give my interlocutor’s variant as common and listed visualize and visualization predominantly with z. A recent colleague of mine used to pronounce literature not as lit(e)ra-chure, but with the clearly articulated group –t-y-re (as in stew) in the middle. Though he taught comparative literature and probably knew better, his habit struck me as intolerable snobbery. But don’t judge lest ye be judged. Just read on.

The Scandinavian Vikings conquered two thirds of England but were soon assimilated. Image credit: The Ravager by John Charles Dollman. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The Scandinavian Vikings conquered two thirds of England but were soon assimilated. Image credit: The Ravager by John Charles Dollman. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.A French word like nature did sound in Middle English as natyur, with stress on the second syllable. Today it is nachure. Picture, stature, and virtue (all from French) have gone the same way: stress in them moved to the first syllable, and tyu turned into an affricate. Its voiced partner is the sound we hear in verdure. An affricate is a complex sound that begins with a stop (that is, p, t, k, b, d, and g) and ends in a fricative (hence the term affricate), or spirant (that is, s, f, and the like). English has two affricates: ch (as in chair and such) and its voiced version (as in jam, job, and dodge). German Pfalz has one affricate at the beginning (pf) and one at the end (ts). In southern German, one can hear kh in word-initial position.

The process of assimilation in picture is a fact of the past: someone ignorant of the history of English has no idea why the word is pronounced the way it is. But the same process as in picture and verdure happens in Present-day English: note how you pronounce this year and as young as (and as you like it!). Most probably, you will hear thish year and azh young. The same holds for did you. Unless you want to enunciate every word with absolute clarity, the result will be didgyou. Such processes vary from epoch to epoch. If a speaker of Old English (let us say, the Beowulf poet or King Alfred) came alive today and began to speak Modern English, he would have pronounced thank you as thanch you.

I could spin a gripping yarn about why we don’t say so but will restrain myself. However, I’ll mention the fact that Modern English owes a few variants to that old pronunciation of k as ch. Consider the following etymologically related pairs: seek ~ beseech, speak ~ speech, (Lan)caster ~ (Man)chester, dyke ~ ditch, and mickle (a northern variant) ~ much. The noun like once meant “person, body” (compare German Leiche “corpse”), as it still does in I shall not see his like again (Hamlet), and the phrase so-and-so and his likes. Lichgate ~ lychgate “a gateway to a churchyard under which the bier is set down at a funeral” has ch, while lykewake “watch kept at night over a dead body” retains the northern variant k.

It is a well-known fact that the British pronunciation of stupid is styupid, while in the US a dummy is stoopid. After st (as in stupid) this difference does not prevent us from understanding one another. But it takes some time to realize that after Monday comes “Chewsday” and that Chunisian means Tunisian. The same happens to the voiced partner of ch: the difference between styupid and stoopid recurs in due/dew versus do. Students constantly write me emails asking when the paper is “do” (of course, everything is said in the syllabus; I call this enquiry the do point). Didgyou (did you) does not bother anyone, partly because the context is always clear. But beware of generalizations. At the beginning of this post, I promised table talk. Unlike kings in cabbages and kings, the promised part will materialize.

Vis-ual aids. Image credit: “Teacher” by jerrykimbrell. CC0 via Pixabay.

Vis-ual aids. Image credit: “Teacher” by jerrykimbrell. CC0 via Pixabay.Last month, at a conference, five colleagues met for dinner. We had been acquainted for decades, so that topics for conversation suggested themselves easily. One of us said that he could not understand what kind of jewel the speaker in a recent talk meant, until it dawned upon him that the paper was about a duel. I replied that I had known the problem for years, for rather early in my career I had been informed that Old Germanic had three numbers: the singular, the plural, and the “jewel,” the last of them being dual (in those far-off days different forms of pronouns existed for we/you and we two/you two; the verbs following such pronouns also had different endings). But for dessert I told my colleagues the following story.

In 1958, in the city at that time called Leningrad, I, then a senior majoring in English, was allowed, among several other seniors and two overseers, to accompany a group of college students from England—a remarkable, even unique privilege that side of the Iron Curtain. One of the female students (let us call her Mary, because her name was Mary) became everybody’s favorite, though all of them, apparently instructed beforehand, behaved extremely well, asked no provocative questions, and let themselves be dragged through multiple museums without a murmur of protest. They were not left to themselves for a single moment. Of course, none of them spoke Russian, and no one in the streets of Leningrad spoke English.

Once, Mary said something to me about some society. “How do you join such a society?” I asked. “That’s easy,” she replied, “anyone may join it: you apply and pay your…” The next word I heard was Jews. I was struck speechless and motionless, as the idiom goes. “Pay your Jews? How?” “You just send them a check” (cheque, if you prefer, for the sake of local coloring ~ colouring). Of course, I did not dare ask her who those Jews were, for the word Jew was unpronounceable in good (Soviet) society, let alone in the presence of Western tourists. Fortunately, I remembered what books on phonetics had taught me: during, I had read, is pronounced as jewring. At that moment, the international Jewish conspiracy was put to rest. “You mean annual dues?” I stammered out. “Yes, yes, annual ‘jews’” she answered. She was puzzled why such a fluent speaker of English (as I was at the age of 21) had trouble understanding a simple monosyllabic word. Moral: learn the rules of assimilation, whether you study history or language, and pay your “dos.”

I promised my colleagues to immortalize this story (it tickled them to death), and you can see that I am as good as my incorruptible word.

Featured Image: Table talk. Featured Image Credit: “ Restaurant” by Free-Photos. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Table talk: How do you pay your dues? appeared first on OUPblog.

Reinventing the textbook in environmental law: time for something new?

I have spent most of the last 30 years in a Sisyphean state of writing and rewriting an environmental law textbook. The process of producing new editions every 2-4 years has involved too many late nights, missed holidays, and general angst. However, the collaboration with other deep thinkers in environmental law has been hugely rewarding, and the writing process has provided a surprising level of intellectual satisfaction.

Taking stock of this exhausting but rewarding experience now seems timely. If academics are to continue these labours of love, changes in technology and the educational experience force us to think about what we are doing in writing textbooks and how we are doing it. Are our intellectual and physical energies being well deployed? Do we have the right vision for student textbooks?

Back in 1988, there wasn’t much competition for student texts that covered the basics of environmental law. There were isolated examples of general and more specialised textbooks, but there was room for something new. When Simon Ball and I first agreed (or perhaps persuaded each other) to try writing a textbook for the relatively new and emerging subject of environmental law, we had a vision of what we wanted to achieve. We wanted the book to be accessible and directed at the non-specialist reader—it was never intended to be a definitive source—and we certainly weren’t interested in writing for the typical academic audience.

We were unashamedly committed to the idea of engaging learners in a way that was simple without being simplistic. We wanted to use a personal, informal tone. We talked about having maps, pictures, and photographs to provide a real-world context for case law, and (horror of horrors) we committed to having no detailed references or footnotes to distract the reader, but instead to have a narrative “Further Reading” section at the end of each chapter where we discussed the sources of the academic ideas in a very simple and abbreviated form of literature review. We wanted it to be short and compact. This approach wasn’t so much a stance against anything, but more of a reflection of the book we wanted to write in the way we wanted to write it. It felt exciting.

Fast-forward 30 years, the shape and tone of the book and the general “market” for student texts have fundamentally changed. There has been a steady flow of new editions and texts and now we have a relatively mature student library. There are traditional textbooks (both general and subject specific) and US style “sourcebooks” with commentary, cases, and materials. There are even revision guides and non-specialist, very short introductions.

Authors face an ongoing cascade of legal developments in trying to map the ever-expanding nature of the subject…

Over time, the student textbook I first started writing in 1988 has acquired a team of authors and is no longer short and compact. Some old and worn chapters have been consigned to the online resource centre (just as a dearly loved pet goes “to live on a farm”) to be replaced by newer, shinier chapters addressing “contemporary issues.” There have been tweaks of presentation as well, with introductory learning outcomes for each chapter, boxes dealing with important case law or specific issues, questions and a context setting example.

Notwithstanding the contemporary typesetting and pedagogic features, I wonder if there is a danger of this sort of textbook becoming anachronistic. Like penny farthings or fax machines, will they soon be perfectly useable but increasingly irrelevant? Today’s students have instant access to a much broader and deeper range of sources than ever before. Google provides an immediate “blagger’s” answer to any question and an almost infinite range of primary and secondary sources can be collated and accessed through a single link on a Virtual Learning Environment. University online teaching platforms compete directly with textbooks.

Authors face an ongoing cascade of legal developments in trying to map the ever-expanding nature of the subject and the increasingly blurred edges between disciplinary boundaries and publishing cycles that render books out of date within days or weeks.

So, to return to my starting point, is it time to think about a new form of environmental law textbook? If we want to engage (and inspire and motivate) a new generation of learners, what might an environmental law textbook for the 21st century (and beyond) look like? Here’s some starting suggestions. Perhaps a text could:

1. Be fully open access. There are obvious advantages of affordability, portability, and navigability, but there would also be the freedom of open-endedness and the opportunity for customization and co-production. Encouraging learners to network and collaborate within a much wider learning community provides real opportunities to become producers rather than consumers of knowledge.

2. Act as a hub that links directly to a wider range of open educational resources. Let’s admit defeat in the battle with ever-increasing complexity and focus on user-friendly overviews whilst encouraging digital literacy, including analysing and evaluating a wide range of digital resources for relevance and accuracy.

3. Engage with a wider range of learning outcomes that might be relevant to understanding the real-world context of environmental law. Perhaps an introduction to coalition formation and negotiation theory when dealing with climate change treaty negotiations? Or basic quantitative or qualitative research methods when analysing data on waste arisings or consumer behaviour? Or even more generic skills such as learning in groups or effective written and oral communication? Shouldn’t we recognise that learners develop much more than knowledge and understanding during a process of active learning?

4. Be structured around the true context for environmental law—authentic, messy, multi-dimensional, interdisciplinary problems that cut across traditional boundaries rather than self-defined silos of knowledge.

5. Finally (and critically), reframe the basic approach that textbooks traditionally take of flagging the environmental problems that law is designed to address but not necessarily presenting law as an active part of a pathway to a solution. Perhaps a new generation of textbooks should explicitly encourage learners to co-produce innovative solutions or pathways to solutions?

Learning whilst trying to make a difference—sounds cheesy doesn’t it—but perhaps that is a worthy manifesto aim for aspiring academic authors who are interested in trying something new?

The post Reinventing the textbook in environmental law: time for something new? appeared first on OUPblog.

September 4, 2018

Meet the editors of Diseases of the Esophagus

This year, professionals and researchers studying the esophagus will convene in Vienna for the 2018 World Congress of the International Society for Diseases of the Esophagus (ISDE 2018). Before the conference gets started, we’ve talked with Drs. Giovanni Zaninotto and Neil Gupta, co-editors-in-chief of the journal Diseases of the Esophagus, about their views on the field and the academic research in the journal.

How did you get involved in Diseases of the Esophagus?

Giovanni: I became a member of ISDE in the nineties and I read the journal since then. When in 2013 I was informed that the society was searching for a surgical co-editor to replace Andre Duranceau, I was interested and applied for the position and I got it!

Neil: Early in my gastroenterology training, I was exposed to esophageal diseases by one of my mentors. After completing my training, my interest in esophageal diseases grew and I continued to work closely with that mentor. When the ISDE was searching for a medical co-editor to replace John Pandolfino, that same mentor suggested that I apply. A few months later, I got a call and said “yes”!

What makes Diseases of the Esophagus unique as a medical journal?

Giovanni: Diseases of the Esophagus occupies a narrow niche in the vast sea of medical scientific journals. As its name states, the journal focuses on the esophagus, that is only a small segment of the gut, but the complexity of its physiology and the difficulty of treating its diseases (the esophagus is deeply buried in the chest and passes through three regions of the human body, the neck, the thorax and the abdomen) have attracted the interest of many physicians and surgeons. Diseases of the Esophagus constitutes the common house where both surgeons and physicians publish their researches and it is a rare example of truly multidisciplinary approach in the field of the medical journals.

Neil: The uniqueness of Diseases of the Esophagus really lies in its multi-disciplinary and international coverage of all things related to the esophagus. While other journals publish certain aspects of esophageal science, Diseases of the Esophagus is the only journal that publishes medical, surgical, endoscopic, radiologic, and oncologic esophageal research from all over the globe.

Image credit: courtesy of Dr. Giovanni Zaninotto.

Image credit: courtesy of Dr. Giovanni Zaninotto.How do you decide which articles should be published in DOTE?

Giovanni: What I am looking for in a manuscript? Excitement (wow!), originality, importance, relevance to our audience, clearly and engagingly written, and high probability of being cited.

Neil: I’m really looking for something that advances the field of Esophagology. Whether it’s the newest technique, the largest study, or the most rigorous methodology, I’m looking for something that’s unique.

What led each of you to the medical field? What made you choose to focus on esophageal health?

Giovanni: During the final year of the Medical School in Padova, I was attracted by the work of a couple of surgeons who were focusing on esophageal diseases. In the mid-seventies, the esophagus was considered the most difficult organ to treat. Flexible endoscopy was just starting, H2 blockers were not yet entered in the clinical practice, CT scans were far from being of common clinical use, and very little was known about esophageal physiology. A very primitive esophageal lab was started and my final dissertation of the medical school was on esophageal pH-monitoring. A long journey was starting: a few years later, I developed the first portable> Image credit: courtesy of Dr. Neil Gupta.

Image credit: courtesy of Dr. Neil Gupta.

What developments would you like to see in your field of study?

Giovanni: In the past years, there have been many technological developments both in diagnosis and therapy of esophageal diseases and many others are in the pipeline: to mention one, the possibility of screening for esophageal cancer with a simple analysis of the exhaled breath. We need thorough and well-conducted studies, especially RCTs, to put all these new “gizmos” in the right pathway for the management of esophageal disease.

Neil: I would like to see more high quality clinical studies that really give practicing physicians answers to their real world clinical problems that they see in routine practice. There are lots of common questions we have on a routine basis and haven’t answered for years. I would love to see some of these questions answered once and for all.

What are you most looking forward to at ISDE 2018?

Giovanni: To meet young researchers and have a glimpse at what will be the research in the next years and to strengthen the relationship with old friends.

Neil: To hear some of the great speakers on the agenda, see some of the new research being presented, and to catch up with friends and colleagues.

Join Diseases of the Esophagus for a Meet the Editors session from 11:45-12:45 on Tuesday, 18 September, in room Hörsaal 01 at the 2018 International Society for Diseases of the Esophagus World Congress.

Featured image credit: St. Stephen’s Cathedral by Jacek Dylag. CC0 via Unsplash.

The post Meet the editors of Diseases of the Esophagus appeared first on OUPblog.

Fracturing landscapes: a history of fences on the U.S.-Mexico divide

This past spring, I traveled to Otay Mesa, a small community in the southeastern section of San Diego that sits on the U.S.-Mexico divide. As a border historian, I’d traveled down to see the prototypes for the wall that Donald Trump has promised to build—the wall that looms large and hangs over the other disturbing headlines of border enforcement and family separation that have dominated our newsfeeds in the past few weeks. There were eight prototypes, some solid walls, others more like enormous steel fences, all of them were extremely tall. After I got a good look at them, I decided to travel west along the border toward the Pacific Ocean to see what I would find. I knew that fences would line the border the entire way, but even as a historian of border fences, I was surprised to see just how many kinds of fences were there. In the short, roughly ten-mile stretch, I saw nearly twenty different fence designs made up of at least six different kinds of materials. In one place, there were four fences still standing; each fence representing some previous phase of construction and a stark reminder that Trump’s prototypes aren’t new at all, they are part of a long historical trend.

The border at Otay Mesa, in fact, is the site of the very first federally funded border fence, planned in 1909 and completed in 1911. This fence, made up of four strands of barbed wire, was built by the Bureau of Animal Industry to stop the movement of cattle ticks that had been responsible for a widespread cattle disease in the United States. Knowing the tick was the disease vector, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) oversaw a campaign to rid the United States of the bug. As it turned out, any cow or steer that was exposed to the tick as a calf was immune to the disease, but if southern cattle moved to the north where the tick was not endemic, it infected unexposed cattle. The effort was successful, but because the tick was endemic to all of Mexico, Mexico did not need to get rid of the parasite. As such, any time cattle crossed the border, officials had to worry about the re-introduction of the tick. To keep cattle from Mexico from coming into the United States, the USDA built the first border fence.

Until the middle of the twentieth century, U.S. officials built fences for cattle and the ticks that they carried. Over time, though, fences became tools to control and restrict human migration. In the second half of the twentieth century, rising xenophobic concerns over the number of Mexican and other Latin American immigrants entering the U.S. led to the passage of a series of immigration laws. Most notable among them were the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act, which limited the number of people who could enter the United States from the Western Hemisphere for the first time (and thus limited the number of Latin Americans), and the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986. None of those laws fully worked to stem the flow of immigrants though, and so each one was eventually supplemented by border fences. “Securing the border” became a standard line for nearly every politician and fences grew in length and height each decade.

In October of 2006, the Bi-national Migration Institute reported that between 1990 and 2003, the Pima County Examiners Office saw a huge rise in the number of deaths along the entire border, many of which occurred in the Arizona-Sonora Desert.

But no matter how high or how long, fences have failed to stop the flow of migration. As Sam Truett argued in his 1997 article in Environmental History, “Ever since the border was mapped in 1854, the American West and the Mexican North have been linked by economic and cultural lifelines extending deep into their respective territories.” Their environments, too, are inextricably linked and no fence can sever those ties.

What fences have done is create and then exacerbate both an environmental and a humanitarian crisis. As fences have grown, they have diverted human traffic through some of the most dangerous landscapes in the Sonoran Desert. In October of 2006, the Bi-national Migration Institute reported that between 1990 and 2003, the Pima County Examiners Office saw a huge rise in the number of deaths along the entire border, many of which occurred in the Arizona-Sonora Desert. According to the report, between 1990 and 2005, the Tucson Sector alone faced a 20-fold jump in known migrant deaths alone, all due to the “funnel effect” of the expanding structures. The fences have also destroyed the natural environment by fragmenting habitats and blocking border crossing by some of our most valued wildlife.

As I argued in my own recent piece in Environmental History, “In the context of this larger history of construction at the border, past and present building projects provide an opportunity to look to history to understand potential outcomes of Trump’s proposed wall: put simply, history tells us that it will not work and that it will do more damage than good.” Human death and environmental degradation are on the rise all around the U.S.-Mexico border and, given the prototypes standing tall near the original site of the first border fence, nothing suggests that that gross destruction of the environment and disregard for human life is going to stop any time soon. Perhaps it’s time to learn from our previous mistakes.

Featured image credit: By Staff Sgt. Dan Heaton, U.S. Air Force. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Fracturing landscapes: a history of fences on the U.S.-Mexico divide appeared first on OUPblog.

Long, short, and efficient titles for research articles

The title of a research article has an almost impossible remit. As the freely available representative of the work, it needs to accurately capture what was achieved, differentiate it from other works, and, of course, attract the attention of the reader, who might be searching a journal’s contents list or the return from a database query. The title needs also, in passing, to signal the author’s competence and authority. Getting it right is vital. Success or otherwise is likely to decide whether the article is retrieved, read, and potentially cited by other researchers—crucial for recognition in science.

Is a long title or a short one better? A long title has obvious advantages in communicating content, but if it is too long, it may be difficult to digest, inducing the reader—with little time and commitment—to move on to the next article in his or her search. Conversely, a short title may be easy to digest, but too short to inform, leaving the reader again to move on. These considerations suggest there is an optimum number of words: enough to reflect content, yet not enough to bore.

The traditional recommendation from manuals on scientific writing and from academic publishers is that 10–12 words is about right, certainly no more, although the evidential basis is uncertain. Do authors follow this guidance? I took a sample of 4,000 article titles from the Web of Science database, published by Clarivate Analytics (formerly Thomson Reuters). The articles were from eight research areas: physics, chemistry, mathematics, cell biology, computer science, engineering, psychology, and general and internal medicine. The average or mean title length was 12.3 words, surprisingly close to the 10–12-word recommendation.

This estimate is necessarily subject to sampling error. Furthermore, it depends on the publication year from which the articles are taken. The mean title length of 12.3 words just quoted was for 2012. It was somewhat smaller at 10.9 words in 2002 and smaller still at 10.1 words in 1982. Mean title length also depends on the choice of subject area, the definition of journal article, and the coverage of the database (whose evolution may have contributed to the growth in mean title length). Nevertheless, reassuringly similar values emerged from an analysis of a larger sample of titles taken from the Scopus database, published by Elsevier.

On average, then, title lengths comply with expectations, possibly reflecting the wisdom of crowds, or of editors. Individually, however, title lengths vary enormously, with around 10% having either fewer than five words or more than 20. So, do articles with extreme titles—those whose lengths fall very far from the mean—succeed in attracting the attention of readers?

Here are two very short titles. The first is from a review article published in 2012 in the Annual Review of Psychology:

“Intelligence”

This article has had more than 180 citations, placing it in the top 1% in its subject area and publication year (citations and centiles for subject areas taken from Scopus for the period 2012–18). As a review article in the social sciences, though, it might be expected to be highly cited. The second title is from an original experimental research article published in 2012 in Physical Review Letters, which in spite of its name is not a review journal:

“Orthorhombic BiFeO3”

The topic addressed is less generally accessible, yet this article has had more than 40 citations and is in the top 7% for its area and year.

Importantly, adding more words to these titles to make them more specific does not seem to deliver a proportional gain in information. Consider expanding “Intelligence” to “An Overview of Contributions to Intelligence Research” or changing “Orthorhombic BiFeO3” to “Creation of a new orthorhombic phase of the multiferroic BiFeO3.” The additions, drawn from the article abstracts, just make explicit what is already largely implied.

So, do articles with extreme titles—those whose lengths fall very far from the mean—succeed in attracting the attention of readers?

By contrast with these very short titles, here are two very long ones. The first has 33 words—with hyphens treated as separators—and was published in 2012 in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology:

“Cost-effectiveness of transcatheter aortic valve replacement compared with surgical aortic valve replacement in high-risk patients with severe aortic stenosis: Results of the PARTNER (Placement of Aortic Transcatheter Valves) trial (Cohort A)”

With more than 120 citations, this article is in the top 1% for its area and year. This performance is not peculiar to general and internal medicine. Articles with very long titles from engineering disciplines can also do well. The second title is from an article published in 2012 in Optics Letters and has about 25 words, depending on definitions:

“Fiber-wireless transmission system of 108 Gb/s data over 80 km fiber and 2×2 multiple-input multiple-output wireless links at 100 GHz W-band frequency”

This article has had more than 110 citations and is in the top 1% for its area and year.

Despite the exceptional lengths of these titles, removing words or phrases, for example, from the first, “Results of the PARTNER . . . (Cohort A)” or, from the second, “at 100 GHz W-band frequency,” seems to result in a disproportionate loss in information and could actually mislead the reader.

Evidently, short titles need not fail to inform and long titles need not promote disengagement. Each can be as effective as the other and lead to high levels of recognition. The implication is that length, on its own, is a poor proxy for something more relevant and fundamental, namely how much the title tells the reader about the work given the number of words it expends.

What is being described here is a kind of efficiency. To paraphrase the statistician and artist Edward Tufte, albeit speaking in a different context, an efficient title is one that maximizes the ratio of the information communicated to its length. Accordingly, the number of words should be immaterial, or almost so. After all, it is what they communicate that really counts.

Featured image credit: Straying Thoughts by Edmund Blair Leighton. Public Domain via Flickr.

The post Long, short, and efficient titles for research articles appeared first on OUPblog.

September 3, 2018

The universality of international law

“The universality of international law [through the development of custom, treaty-making, and participation in universal international organizations]…is inextricably linked to the formality of international law. This formality of international law supports its universality, as it allows coexistence between entities with different values and conceptions of justice.” André Nollkaemper

The 14th Annual Conference of the European Society of International Law will take place at the University of Manchester, from 13th September through 15th September. This is one of the most important events in the international law calendar, attracting a growing network of scholars, researchers, practitioners, and students. The conference not only provides a forum for the exchange of new ideas, but also encourages the study of international law and promotes a greater understanding of its role in the world today.

This year’s conference theme will focus on “International law and universality,” and participants will be tasked with tackling important questions such as: What are the limits of formal and substantive universality? Can international organizations address the diverse needs of the international community? What impact do opposing cultural, socioeconomic, and political influences have on the application of the substantive and primary rules of international law geographically?

In preparation for this year’s meeting, we have asked some key authors to share their thoughts on the subject:

“The universality of international law is a heavily contested concept, especially in a diverse world where the issue of “whose international law is universal” is not an easy one to answer. My own work on unilateral sanctions has however brought me to the surprising conclusion that international law’s universality is not as fictitious as we may believe. The practice of non-UN sanctions is certainly not universally accepted; certain States (mainly developed countries) are quick to impose sanctions in response to violations of certain norms, other States (mainly developing countries and emerging powers) are quick to contest this practice. Although it should be acknowledged that sanctions are more frequently adopted to enforce civil and political rights rather than social and economic rights, the dispute surrounding sanctions rarely revolves around the norm the sanctioning entity is seeking to enforce. Seeing as normative agreement is at the basis of any (legal) order, this suggests that States may agree on the norms that lie at the foundation of the international system but disagree on the means through which it should be upheld. Using this as our basis the issue becomes: which enforcement practices can transform the fiction of international law’s universality into a reality?”

— Alexandra Hofer is a PhD Candidate at Ghent University. She is assistant editor of The Use of Force in International Law: A Case-Based Approach (Oxford 2018), and has published in the Chinese Journal of International Law and in the Journal of Conflict and Security Law.

“A way to understand universality in international law is to focus on the common values that international law ought to promote. Does international law promote moral projects of global concern? Can it? The modern state produces a paradox: it is necessary for international law to reflect a universality of values, robustly understood, to solve many of the problems the planet faces today, but it is exceedingly difficult to get international law to reflect these values. Advances in the study of moral cognition inform us that our capacity to care about others evolved to facilitate cooperation within groups but not between groups. Our moral brains stop us from universalizing the commitments of justice across tribes. International law faces special challenges in getting what ought to be our moral regard for others across borders. Overcoming our cognitive limitations requires us to change how we think about international law. Economic and social rights might take a secondary role, coming only after what ought to be done is settled. A more granular focus on the consequences of international law commitments might be more effective, particularly when it comes to burden and benefit sharing in the global economy.”

— John Linarelli, Professor of Commercial Law at Durham Law School, and co-author (with Margot Salomon and M Sornarajah) of The Misery of International Law: Confrontations with Injustice in the Global Economy (Oxford 2018)

Can international organizations address the diverse needs of the international community?

“Universality is a facade. Worse still, it is a fake, a phony, an opiate, a weapon of the strong. Recognition of this condition leads to an imperative: step behind the facade to see what has been pushed out of sight and redacted.

Justice provides a clear example. Lady Justice stands strong, her impartiality signified by her blindfold and scales even as she grips the sword of authority. But she has a doppelgänger. This double sometimes peeks through the blindfold — if she wears one at all. Lady Justice also has a history. Her double often goes by other names: Justitia, Themis, Dike, and Maat to name a few.

Once we begin to look for this doppelgänger in the tangles of history and variation, we begin to see the cracks in the facade of Universality that misdirects our gaze even as it offers legitimacy and power. If we follow Lady Justice’s doppelgänger further still, she leads us to the issues of translation and heteroglossia. For Lady Justice speaks only in lingua franca and demands all speak in the voice of Law. Her doppelgänger, in contrast, is a trickster who prefers the vernacular and the moments that universal Justice breaks down in translation.

And so we return to the imperative with which we began, which asks that we begin not with the Universals of international law but with its doubles. Follow the doppelgängers of international law. Step behind the justice facade.”

— Alexander Hinton, Distinguished Professor of Anthropology, Director, Center for the Study of Genocide and Human Rights, UNESCO Chair in Genocide Prevention, Rutgers University, and author of The Justice Facade: Trials of Transition in Cambodia (Oxford 2018)

*The comments expressed in this article are the personal responses of the cited authors, and do not in any way reflect the opinions of Oxford University Press.

Featured image credit: Manchester by timajo. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post The universality of international law appeared first on OUPblog.

September 2, 2018

The flow of physics

Galileo was proud of his parabolic trajectory. In his first years after arriving at the university in Padua, he had worked with marked intensity to understand the mathematical structure of the trajectory, arriving at a definitive understanding of it by 1610—just as he was distracted by his friend Paolo Sarpi who suggested he improve on the crude Dutch telescopes starting to circulate around Venice. This distraction lasted 20 years, only to end under his house arrest, when he finally had time to complete and publish his work on motion in his Two New Sciences.

Galileo’s trajectory was a solitary arc with specific initial conditions. Similarly, Kepler’s orbits were solitary ellipses, one for each of the planets. When Newton posited his second axiom, in Latin prose (no equation) outlining the differential equation  , he integrated it to obtain its integral curve, once again focusing on special cases defined by specific initial conditions. Even Lagrange, freed from Newton’s law, was still bound in his use of the principle of least action to solitary beginnings and endings, to the single path between two points that minimized the mechanical action. This legacy of great figures in the history of physics—Galileo, Kepler, Newton, Lagrange—along with a legion of introductory physics teachers today, helps to perpetuate the perspective that physics treats solitary trajectories.

, he integrated it to obtain its integral curve, once again focusing on special cases defined by specific initial conditions. Even Lagrange, freed from Newton’s law, was still bound in his use of the principle of least action to solitary beginnings and endings, to the single path between two points that minimized the mechanical action. This legacy of great figures in the history of physics—Galileo, Kepler, Newton, Lagrange—along with a legion of introductory physics teachers today, helps to perpetuate the perspective that physics treats solitary trajectories.

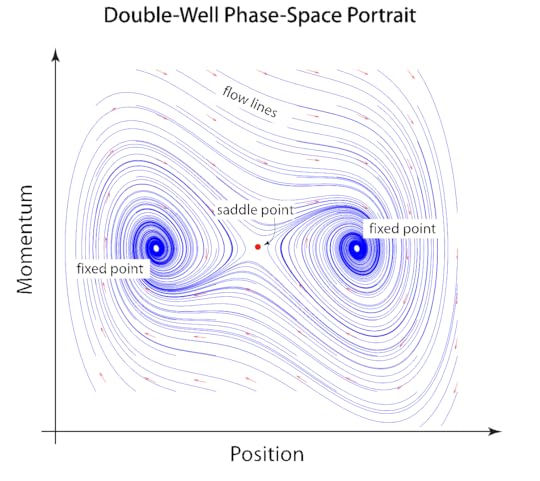

Image credit: Example of a phase-space portrait of the damped double-well potential. Redrawn with permission from D. Nolte, Introduction to Modern Dynamics (Oxford University Press, 2015).

Image credit: Example of a phase-space portrait of the damped double-well potential. Redrawn with permission from D. Nolte, Introduction to Modern Dynamics (Oxford University Press, 2015).Yet over a hundred years ago, Henri Poincaré took a decisive step away from the solitary trajectory and began thinking about dynamical systems as geometric problems in dynamical spaces. He was not the first—the nineteenth century mathematicians Rudolph Lipschitz and Gaston Darboux, inspired by Bernhard Riemann, had already begun to think of dynamics in terms of geodesics in metric spaces—but Poincaré was the first to create a new toolbox of techniques that treated dynamical systems as if they were the flow of fluids. He took a fundamental step away from concentrating on single trajectories one at a time, to thinking in terms of the set of all trajectories, treated simultaneously as a field of flow lines in dynamical spaces.

This was the dawn of phase space. Phase space is a multidimensional hyperspace that is like a bucket holding all possible trajectories of a complex system. James Gleick, the noted chronicler of science, has called the invention of phase space “one of the most important discoveries of modern science”. Phase space was invented in fits and starts (and at times independently) across a span of 70 years, beginning with Liouville in 1838, then added to by Jacobi, Boltzmann, Maxwell, Poincaré, Gibbs and finally Ehrenfest in 1911. A phase-space diagram, also known as a phase-space “portrait,” consists of a set of flow lines that swirl around special points called fixed points that act as sources or sinks or centers, and the flow is constrained by special lines called nullclines and separatrixes that corral the flow lines into regions called basins. These complex flows are like string art, and phase-space portraits like Lorenz’s Butterfly have become cultural memes.

Attached to each flow line on a phase portrait is a tangent vector, constituting a vector field that fills phase space. These tangent vectors are to dynamics what the vector fields of electric and magnetic phenomena are to electromagnetics. A broad class of complex systems with their flows can be described through the deceptively simple mathematical expression for the vector field where the “dot” is the time derivative, and the variables and the function are vector quantities. The vector

where the “dot” is the time derivative, and the variables and the function are vector quantities. The vector  is the set of all positions and all momenta for a system with N degrees of freedom. When the physical system is composed of interacting massive particles that conserve energy (like the atoms in an ideal gas or planets in orbit), then the flow equation reduces to Hamilton’s equations of dynamics. Yet dynamical systems treated by flows are much more general, capable of capturing the behavior of firing neurons; the beating heart,; economic systems like world trade; the evolution of species in ecosystems; the orbits of photons around black holes. These have all become the objects of study for modern dynamics. It would not be an exaggeration to say that is to modern dynamics what

is the set of all positions and all momenta for a system with N degrees of freedom. When the physical system is composed of interacting massive particles that conserve energy (like the atoms in an ideal gas or planets in orbit), then the flow equation reduces to Hamilton’s equations of dynamics. Yet dynamical systems treated by flows are much more general, capable of capturing the behavior of firing neurons; the beating heart,; economic systems like world trade; the evolution of species in ecosystems; the orbits of photons around black holes. These have all become the objects of study for modern dynamics. It would not be an exaggeration to say that is to modern dynamics what  was to classical dynamics.

was to classical dynamics.

The flows of physics encompass such a broad sweep of subjects, that it is sometimes difficult to see the common thread that connects them all. Yet, the phase-space phase portrait, and computer techniques for the hypervisualization of many dimensions are becoming common tools, providing a unifying language with which to explain and predict the behavior of systems that were once too complex to address. By learning this language, a new generation of scientists will cut across the Babel of so many disciplines.

Featured image credit: The International Space Station by Paul Larkin. Public Domain via Unsplash.

The post The flow of physics appeared first on OUPblog.

Hamburger semantics

The students in my class were arguing a question of semantics: is a hamburger a sandwich?

One student noted that the menu designer at the restaurant where she worked couldn’t decide if a Chicken Burger should be listed under Hamburgers or Sandwiches. Another student invoked the USDA’s definition of a sandwich as “meat or poultry between two slices of bread.” The discussion in class got surprisingly heated, with raised voices and an expletive hurled. People feel strongly about meanings and their burgers.

Not long afterwards, two friends were arguing a point of usage on Facebook. One asserted that “Words have a meaning – which facilitates clear communication among participants in a language – or they do not.” The other countered that “Words don’t have a meaning. Most words communicate many different things.” And she gave the example of the polysemy of the word “sandwich.”

Words do communicate many different things and their meanings shift over time. The two discussions made me hungry to address the semantics of words like “sandwich” and “hamburger,” which turn out to be a particularly good test kitchen in which to explore the evolution of words.

“Sandwich,” of course, is an eponym from the title of the fourth Earl of Sandwich, John Montagu (1718–1792). It refers to “an item of food consisting of two pieces of bread with meat, cheese, or other fillings between them, eaten as a light meal.” It can also mean “something that is constructed like or has the form of a sandwich” (according to the Oxford Living Dictionary). The first definition gets extended a bit in usages like “open-faced sandwich,” where the filling is not actually between the bread, and in “club sandwich,” which involves more than two pieces of bread. The second meaning of “sandwich” gets extended metaphorically in “sandwich generation” and in the slang expression, “a knuckle sandwich.”

Food historians trace the term “hamburger” to the German immigration of the nineteenth century, and according to the Oxford Encyclopedia of Food and Drink in America, Delmonico’s restaurant in New York offered a Hamburg Steak as early as 1834. Cookbooks soon featured the Beefsteak à la Hamburg and the Salisbury Steak, pioneered by the Civil War physician, James H. Salisbury.

Hampered for a time by early twentieth century fears of ground meat (think Upton Sinclair and The Jungle), hamburgers on a bun became popular as fair food in the early twentieth century and took off after 1921, popularized by the Kansas-based White Castle restaurant.

The rest is culinary history.

By the 1930s, “sandwich” was being omitted and “hamburger” was no longer an adjective modifying “steak” or “sandwich,” but a noun in its own right. What’s more, “burger” was becoming a productive word part.

And linguistic history as well. The term “Hamburger Steak” lost ground to “Salisbury Steak,” which became the more common way of referring to beefcakes with gravy instead of buns. According to H. L. Mencken in The American Language, the term “Salisbury Steak” was helped along by the World War I fervor for Americanizing German food words. However, the word “hamburger” (sometimes without the –er) prevailed as the name of the beef patty in a bun, and as early as 1916, we can find menus listing the “hamburger sandwich,” which is how White Castle featured it as well.

By the 1930s, “sandwich” was being omitted and “hamburger” was no longer an adjective modifying “steak” or “sandwich,” but a noun in its own right. What’s more, “burger” was becoming a productive word part. The journal American Speech documented blended neologisms like cheeseburger, chicken burger, and wimpy burger (after the character J. Wellington Wimpy in the Popeye comic strip), as well as the turkey burger and the lamburger. It seemed that “-burger” could be used with all kinds of foods served hamburger-like on a bun: clam burgers, shrimp burgers, fish burgers, there was even something called a nutburger (described as a nut and meat sandwich). What was blended, linguistically, with burger could indicate toppings (cheeseburger, egg burger, bacon burger), composition (rabbit burger, mooseburger, veal burger), or style (California burger, Texas burger, twinburger).

With so many linguistic combinations ending in “burger,” the clipped version came to be mostly used as to refer generically to hamburger-style sandwiches—patties on buns with condiments and garnishes. On menus today, “Burger” is often used as a heading that includes hamburgers and various other burger-like sandwiches as well. One local eatery in my town offers “ALL KINDS OF BURGERS” and below that heading lists HAMBURGER, TURKEY BURGER, GARDENBURGER, SEABURGER (fresh Oregon snapper fillet charbroiled ), and a double beef patty SUPERBURGER.

So is a hamburger a sandwich? If a sandwich is two pieces of bread with meat between them, a hamburger qualifies as a sandwich (John Montagu would probably have loved them as much as J. Wellington Wimpy does). But if we think of a hamburger as a round patty of ground beef typically served on a bun, it becomes less sandwich-like and more of an independent semantic category. A hamburger is like a thumb in that regard: a thumb is both a finger (we have ten of them) and something more.

Bon appétit.

Featured image credit: “Le Jour ni l’Heure 3275 : L’Invention du hamburger — Giambattista Tiepolo, 1696-1770, Abraham et les trois anges, c. 1770, Prado, dét., samedi 3 mai 2014, 17:38:11” by Renaud Camus. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Hamburger semantics appeared first on OUPblog.

September 1, 2018

How Trump beat Ada’s big data

The Democratic Party’s 2008 presidential primary was supposed to be the coronation of Hillary Clinton. She was the most well-known candidate, had the most support from the party establishment, and had, by far, the most financial resources.

The coronation went off script. Barack Obama, a black man with an unhelpful name, won the Democratic nomination and, then, the presidential election against Republican John McCain because the Obama campaign had a lot more going for it than Obama’s eloquence and charisma: Big Data.

The Obama campaign put every potential voter into its database, along with hundreds of tidbits of personal information: age, gender, marital status, race, religion, address, occupation, income, car registrations, home value, donation history, magazine subscriptions, leisure activities, Facebook friends, and anything else they could find that seemed relevant.

Layered on top were weekly telephone surveys of thousands of potential voters that attempted to gauge each person’s likelihood of voting—and voting for Obama. These voter likelihoods were correlated statistically with personal characteristics and extrapolated to other potential voters so that the campaign’s computer software could predict how likely each person in its database was to vote and the probability that the vote would be for Obama.

This>wonks who put all their faith in a computer program and ignored the millions of working-class voters who had either lost their jobs or feared they might lose their jobs. In one phone call with Hillary, Bill reportedly got so angry that he threw his phone out the window of his Arkansas penthouse.

Big Data is not a panacea—particularly when Big Data is hidden inside a computer and humans who know a lot about the real world do not know what the computer is doing with all that data.

Computers can do some things really, really well. We are empowered and enriched by them every single day of our lives. However, Hillary Clinton is not the only one who has been overawed by Big Data, and she will surely not be the last.

Featured image credit: American flag by DWilliams. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post How Trump beat Ada’s big data appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers