Oxford University Press's Blog, page 229

September 11, 2018

5 essential focuses in Sociology

Sociology is a rather new discipline; while its founding theorists lived during the Enlightenment, seminal figures like Karl Marx, Emile Durkheim, and Max Weber shaped the field amid the rise of industrialization and modernity. The scientific and political upheavals of the 19th and 20th centuries brought about a new understanding of how society worked. It is truly a crucial field of study in today’s interconnected world.

From the concept of intersectionality to the social impacts of the welfare state and the ubiquity of mass media, we’ve gathered excerpts from five critical avenues of sociological thought.

Individuals are shaped by the multiple categories to which they are perceived to belong and the social structures that undergird systems of categorization. Systems of social categorization are virtually always associated with differential, unequal resources. Intersectionality is a concept fundamental to understanding these societal inequalities; the key assertion of intersectionality is that the various systems of societal oppression do not act independently of each other. Different systems of inequality are transformed in their intersections, the fundamental principle of intersectionality. The phrase “race, class, and gender,” still in use, is a precursor of the concept of intersectionality. The preferred use of the latter term reflects in part the awareness that there are more than three intersecting systems of societal inequalities. Further, some identities may be privileged categories, others marginalized. Thus oppression and privilege may be experienced simultaneously, complicating the analysis of inequality. Intersectionality crosses levels of analysis, from the micro-level experiences of individual actors to the macro-level structural, organizational, and institutional contexts in which human interactions and experiences are formed. Intersectionality is an analytic approach, a way of thinking about social categories that articulates similarity and difference, always inflected by relations of power. – Judith A. Howard

What is the modern welfare state?

Modern welfare states aim to implement social policies to remedy the suffering caused by ruthless market mechanisms. They provide insurances to allow citizens to prepare for the vicissitudes of life, such as aging, illness, injuries, retirement, and unemployment. In cases in which citizens do not have employment and income to sustain insurance schemes due to those same difficulties, welfare states still provide a certain degree of safety to this less capable population. However, the generosity and spending patterns of welfare states vary widely depending upon their inherent structures, goals, commitments, and capacities. The late 20th century saw the beginning of ongoing neoliberal trends of market fundamentalism linked with increasing economic globalization in trade, investment, and finance; postindustrial structural transformations of labor market; increasing immigration; rapid aging of the population; and dissolution of traditional family structures. In the face of these structural transformations and pressures, how have different welfare regimes reacted to help stressed populations, especially the poor? Furthermore, how do welfare states in developing countries protect their less capable populations under the pressures of globalization and postindustrial economic transformation? – Cheol-Sung Lee and In-Hoe Koo

What constitutes “mass media?”

Germany Under Allied Occupation 1945/Scene of destruction in a Berlin street just off the Unter den Linden. No 5 Army Film & Photographic Unit, Wilkes A (Sergeant). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Germany Under Allied Occupation 1945/Scene of destruction in a Berlin street just off the Unter den Linden. No 5 Army Film & Photographic Unit, Wilkes A (Sergeant). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.While the “mass media” have long been an object of research, scholarly emphasis has shifted in recent decades from the first word of that term to the second. In the 1920s and 1930s, as the sociology of mass media began to assert itself as an academic subdiscipline, social scientists, media industry researchers, and other critics were concentrated most intently on aggregate, society-wide “mass” effects. In the contemporary moment, the focus has shifted to “media” as plural in every sense: as technologies, as niche circuits of cultural production and reception, and as distinctive multinational, national, or subnational institutional fields. How far this fragmentation of media goes, to what extent it is really something new, and the degree to which it also means a dispersal of power continue to be at the center of debate in sociology and related disciplines. There is also ample evidence of increases in the scale of media infrastructures along with new kinds of global connections. – Rodney Benson and Tim Wood

How can war be studied sociologically?

Wars are no longer confined to the battlefield context, with well-defined military forces facing similarly organized opponents engaged in mutual destruction within a confined space and limited duration. Any sociologically informed understanding recognizes that war was never thus, but rather always situated in social, economic, and political dynamics that went far beyond the battlefield, being influenced by and having implications for social transformation. The international political sociologist would start with the premise that practices of war and peace are situated in wider discursive and institutional continuities and are implicated in societal change. Equally significant from the outset is a rejection of perspectives that assume a clear-cut dividing line between the domestic and the international. The practice of war might be used to draw and redraw boundaries: how these are drawn, where and whence they are manifest, how they impact on trajectories of power and political authority, and how these, in turn, are, in late modernity, articulated in global terms. We might, therefore, appreciate sociological writings that focus on war and the state. – Vivienne Jabri

Comparing the processual model of Stan Cohen with the attributional model of Erich Goode and Nachman Ben-Yehuda reveals three basic similarities and three significant differences. The first similarity is their shared view that moral panics are an extreme form of more general processes by which social problems are constructed in public arenas. The second similarity is that they both observe that moral panics are recurrent features of modern society that have identifiable consequences on the law and state institutions. The third similarity is the perceived sociological function of moral panics as reaffirming the core values of society. On the other hand, the first difference lies in how they assess the role of the media. In the processual version, the media are strategic in the formation of moral panics. They may be the prime movers or endorse others already campaigning, but they are always actively involved. In the attributional model, despite their greater prominence in Goode and Ben-Yehuda’s second edition, the media play a much more passive role. They provide an arena where different versions can compete. – Chas Critcher

Featured image credit: “The witch no. 1” lithograph by Joseph E. Baker, depicting the Salem Witch trials, an example of a moral panic, 29 February 1892. Library of Congress, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post 5 essential focuses in Sociology appeared first on OUPblog.

An archaeology of early radio production: doing sound historiography without the sound

What did early US radio sound like? During radio’s initial rise to prominence in the 1920s, before the “golden age” of network broadcasting in the 1930s and 1940s, what kinds of programming, production practices, and performance styles greeted audiences’ ears when they tuned into this new medium? What strategies of musical instrumentation, sound mixing, and dramatic representation were favored for these broadcasts, and what styles of singing, playing, speaking, and acting did early radio listeners hear?

At first glance (first whisper?), these questions should seem easy enough to answer. Why not just play a few recordings of old programs – “listen in” on the past, as it were, to the surviving traces of that bygone era – and hear for ourselves? However, those recordings do not, in fact, exist, at least not for this early, prenetwork period. To reconstruct this otherwise silent soundscape, the historian is thus left to either project back onto the past from anachronistic evidence of subsequent network-era recordings (in short, doing bad history), or look to other sources entirely – that is, doing sound historiography without the sound.

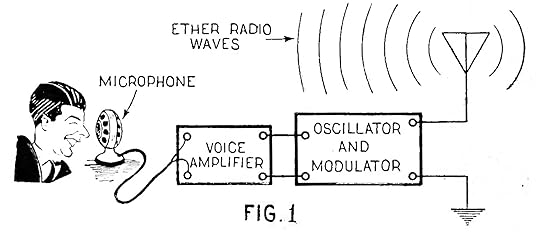

A. P. Peck, “How Broadcast Stations Operate,” Radio Listeners’ Guide and Call Book, Late Fall 1925. Used with courtesy of Larry Steckler.

A. P. Peck, “How Broadcast Stations Operate,” Radio Listeners’ Guide and Call Book, Late Fall 1925. Used with courtesy of Larry Steckler.In my own work as a radio historian, I have advocated confronting these challenges through a production-oriented approach that uncovers the lost sounds of early radio through an archaeological dig into the creative practices of the professional soundworkers who made them. From the programmers who sculpted radio’s emerging temporal rhythms and flows to the writers who crafted new, radio-friendly forms of music, drama, and talk, the directors who guided performers on the studio floor, the singers, musicians, actors, and speakers who appeared before the radio microphone, and the control room engineers who fashioned the final radio mix, the historical record offers rich evidence of the forms of sonic labor cultivated by the producers and performers charged with the daily task of radiomaking. In excavating these emergent forms of radio soundwork, here are a few places I suggest we look – topoi, if you will, for a new sonic archaeology conducted in the absence of the sounds themselves:

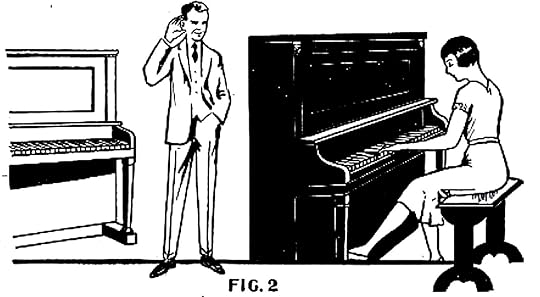

Sylvan Harris, “Fundamental Principles of Radio,” Radio Listeners’ Guide and Call Book, Late Fall 1925. Used with courtesy of Larry Steckler.The job of soundwork is also a matter of paperwork, with federal regulators and station staff swiftly spawning internal systems of record-keeping that rivaled any other form of modern bureaucracy. Early license periods were short, with regulators issuing regular guidelines to stations seeking renewals that covered everything from studio acoustics to preferred classes of programming service. Station records are similarly instructive sources, including everything from internal memos on shifts in programming policies, to program logs that reveal nascent scheduling strategies and document quality control issues, to scripts that include handwritten musical and sound effects cues.In addition to official station records, personal papers of popular singers, announcers, and program hosts populate the archives, offering treasure troves of materials on early production strategies and documenting the careers of sound workers otherwise lost to time. Oral histories may similarly help call back into presence the sounds of a bygone era, while surviving caches of listener letters are filled with pertinent details concerning beloved or reviled techniques practiced by early radio performers.The radio industry also yielded an entire secondary print market, including professional journals in which members of the new profession traded tips and strategies, textbooks for those seeking to refine techniques of radio speaking, popular radio magazines that took fans behind the scenes of their favorite performances, and critics’ columns that spilled small oceans of ink on the merits or problems with particular programs, performers, and production strategies.

Sylvan Harris, “Fundamental Principles of Radio,” Radio Listeners’ Guide and Call Book, Late Fall 1925. Used with courtesy of Larry Steckler.The job of soundwork is also a matter of paperwork, with federal regulators and station staff swiftly spawning internal systems of record-keeping that rivaled any other form of modern bureaucracy. Early license periods were short, with regulators issuing regular guidelines to stations seeking renewals that covered everything from studio acoustics to preferred classes of programming service. Station records are similarly instructive sources, including everything from internal memos on shifts in programming policies, to program logs that reveal nascent scheduling strategies and document quality control issues, to scripts that include handwritten musical and sound effects cues.In addition to official station records, personal papers of popular singers, announcers, and program hosts populate the archives, offering treasure troves of materials on early production strategies and documenting the careers of sound workers otherwise lost to time. Oral histories may similarly help call back into presence the sounds of a bygone era, while surviving caches of listener letters are filled with pertinent details concerning beloved or reviled techniques practiced by early radio performers.The radio industry also yielded an entire secondary print market, including professional journals in which members of the new profession traded tips and strategies, textbooks for those seeking to refine techniques of radio speaking, popular radio magazines that took fans behind the scenes of their favorite performances, and critics’ columns that spilled small oceans of ink on the merits or problems with particular programs, performers, and production strategies. F. R. Bristow, “Causes and Cure of Radio Interference,” Radio Craft, January 1930. Used with courtesy of Larry Steckler.

F. R. Bristow, “Causes and Cure of Radio Interference,” Radio Craft, January 1930. Used with courtesy of Larry Steckler.If we were at first confronted with a seemingly vanished stratum of programming from radio’s prenetwork period, adopting the production-oriented approach I have advocated reveals a vast wealth of historical traces that let us reconstruct the sounds of this lost era via other means. This approach not only enables us to reconstruct what early broadcasts sounded like, it also tells us why they sounded this way – why, in other words, workers pursued the creative choices they did, and what larger pressures or rationales informed those decisions. Studying these emergent forms of soundwork gives us better insight into radio history, revealing the development of dominant production practices and aesthetic norms by a surprisingly early date. Some of these norms and practices would continue to inform network productions of subsequent decades, while many would also be echoed in practices adopted by workers within the neighboring film and record industries during the closing years of the decade, upon their own embrace of the twentieth century’s new technologies of electric sound reproduction. Lending an ear to the work of those who engaged in the daily task of making radio in this sense can tell us not only more about the history of broadcasting itself, but also about much broader transformations in modern sound culture in which the radio medium played a formative part and whose reverberations continue, in many ways, well into the present.

Featured image credit: Radio by Vande Walle Ewoud. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post An archaeology of early radio production: doing sound historiography without the sound appeared first on OUPblog.

September 9, 2018

Revealing the past of childhood before history

Through most societies of the human past, children comprised half the community. Archaeologists and their collaborators are now uncovering many aspects of the young in societies of the deep past, too long the ‘hidden half’ of prehistory.

In coastal mud at Happisburgh in England, footprints of ancient Homo dating from 800,000 years ago include those of a child just 3ft, 3in high. In the caves of Upper Palaeolithic France, more footprints show adult cave painters were accompanied by children. Ochre markings around the outstretched hand of a patient child held against a rock wall are permanent graffiti that have lasted 20,000 years, and the fingers of two-year-old children daubed paint on walls suggest them sitting on an adult’s shoulders.

In the rock engravings of the Mojave Desert in Nevada we see two adults walking with their two children, and in paintings of Southern Africa, young children walk alongside women we assume to be their mothers.

Children in every time and place start to learn the core crafts they will need as adults, typically by watching and copying. Evidence of learning may be hard to identify, though weaving equipment was found in Bronze Age and Iron Age burials of children in Italy. But if the apprentice’s metalwork is melted down for re-use, or the unskilled pots remain unfired, archaeologists will not find them. In the Trans-Urals of Russia, fingerprints from children aged five to eight were found on rough Bronze Age pots of the second millennium BC buried with children; were they made by the deceased child, or provided for burial by the child’s age-mates?

In the Trans-Urals of Russia, fingerprints from children aged five to eight were found on rough Bronze Age pots of the second millennium BC buried with children; were they made by the deceased child, or provided for burial by the child’s age-mates?

Stone tools last forever. Both learners and experts produce plenty of waste flakes before the final tool emerges. We may find the unskilled apprentice if we look for a concentrated area of poorer quality knapping which implies an area for learning and practice. Increasing numbers of such sites have been identified, from Sweden to Ireland, from the US Great Basin in Nevada to Hokkaido in Japan, and dating from Neanderthal times onwards.

Play, of course, helps practical skills develop. We do find objects which appear more like a modern child’s plaything. But is that what they are? Is a human figure a child’s doll or – to use the archaeological cliché – a ‘ritual object’? The little clay animal figures from Lizard Man village in Arizona look like toys; an Iron Age rattle in the form of a small animal from Iron Age Czech Republic could be the same. Miniature furniture found at the Neolithic site of Ovčarovo in Bulgaria ‘feels’ like a doll’s house, as does the clay model house with small animals from the Greek Neolithic site of Platia Magoula Zarkou, but we cannot be sure.

The playthings made by children for themselves may not always survive. It seems likely, too, that we sometimes fail to recognise the activities and products of childhood in what appears as a random scatter.

Until recently it was nearly inevitable that only some of those born into a family would survive into adulthood. Most of our information on children in prehistory comes from those who died young. We have children’s bodies from as far back as the African Australopithecines. Deliberate burials by Neanderthals include those of children. In prehistory, the youngest infants may have received no formal burial, and infanticide is acknowledged as a feature of many past societies. But some prehistoric societies buried older children using the same ritual and location as for adults, some buried children separately, while others placed their remains beside the dwelling, like those below house floors at sites in Cyprus and Turkey.

The style and content of a child’s burial reflect the culture of their society but also the wealth and status of their family. Grave goods can range from a simple pot with food to a collection of household items, or to lavish body decoration. An Upper Palaeolithic child aged two to four years at La Madeleine in France wore clothing embroidered with 1,000 beads; two older children at Sunghir in Russia had ivory carvings, spears and 10,000 beads. Children of prehistoric foragers in Argentina had up to 1,000 beads.

The style and content of a child’s burial reflect the culture of their society but also the wealth and status of their family. Grave goods can range from a simple pot with food to a collection of household items, or to lavish body decoration.

The fabrics of children’s clothing (skins, or later fabrics) may survive. The skulls may show head binding as in the Tiwanika culture of the Andes, or the accidental head deformation arising from the use of cradleboards in North America.

The skeleton itself can show signs of trauma, whether fatal or showing survival suggesting community care, and including the impact of war. There was little discrimination by age or gender in the weapon marks on bodies of fifty-eight adults and children massacred at a 12,000-year-old site of advanced foragers at Jebel Sahaba in Sudan. The fourteenth-century massacre site of Crow Creek in South Dakota included 144 children.

Bioarchaeological studies can examine skeletal remains for signs of childhood disease, trace childhood diet and weaning age, and even migration: burials found near England’s Stonehenge indicated a childhood far away in Wales, Scotland or even further.

Time-travelling archaeologists visiting a forager camp or farming village would first encounter the noise of children. Their voices have been relatively silent in archaeological narratives but now that has begun to change.

Featured image credit: A Neanderthal family scene: reconstruction at Krapina Neanderthal Museum, Croatia by Tromber. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons .

The post Revealing the past of childhood before history appeared first on OUPblog.

September 8, 2018

Animal of the month: 8 facts about rabbits

Popular as pets, considered lucky by some, and widely recognised as agricultural nuisances, rabbits are commonplace all over the world. Their cute, fluffy exterior hides the more ingenious characteristics of this burrowing herbivore, including specially-adapted hind legs, extra incisors, and prolific breeding capabilities. Whilst rabbits thrive in most areas, certain species face the common struggle of their specialist habitats being destroyed, and myxomatosis has devastated rabbit populations in the past, at one point destroying 99% of the rabbit population of the United Kingdom. Luckily, rabbits have been able to recover from this, and several species of rabbits have lately been able to recover from the brink of extinction. Learn more about what makes rabbits so fascinating with our factsheet.

1. Rabbits, rabbits, everywhereRabbits are the primary prey of several different avian and mammalian predators. To counteract this, rabbits have adapted to become super-breeders. They reach sexual maturity early, sometimes when they are as young as three months old, and have short gestation periods of between thirty and forty days. Their litters are large, and females also have the uncanny ability to ovulate upon copulation instead of on a cyclical basis, become pregnant immediately after giving birth, and even conceive a second litter whilst still being pregnant with their first!

2. Critter controlThe remarkable breeding habits of rabbits mean that populations have overwhelmed the amount of predators in their habitat on a number of occasions. As a result, measures are often put in place to attempt to control rabbit populations. These can include the introduction of predators to the habit, as well as the use of biocontrol agents.

3. Family funRabbits are part of the family Leporidae, which also includes hares and cottontails. The shared family characteristics are short tails, long ears, and hind legs which are specially adapted to enable the animals to jump.

Image credit: Marsh Rabbit at Smyrna Dunes Park by Andrea Westmoreland. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.4. Lagomorpha

Image credit: Marsh Rabbit at Smyrna Dunes Park by Andrea Westmoreland. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.4. LagomorphaLeporidae are a part of the order Lagomorpha, an order which only came into being around one hundred years ago. The animals in the Lagomorpha order were previously included in the Rodentia order, due to the characteristics that they share with rodents – the most compelling being that animals of both orders have gnawing incisors. The difference between lagomorphs and their rodent cousins is that lagomorphs possess a second pair of incisors next to their main gnawing incisors. The Lagomorph order includes rabbits, hares, cottontails, and pikas.

5. What’s in a name?Rabbits were previously better known as coneys, with the word rabbit referring to a young rabbit and coney to an older animal. The word coney is a borrowing from Anglo-Norman and Old French words such as conin and counin. Why adopt these French words? Rabbits were originally brought to Britain by the conquering Normans!

6. Where in the worldRabbits can be found all over the world, from Japan to Greenland! The European rabbit is native to southwestern Europe, and has been introduced by human populations to a number of different countries around the world. Copious other species of rabbits can be found around the globe, some in very challenging habitats. The Desert Cottontail, for example, lives in Death Valley, California, and the Marsh Rabbit lives in Virginian swamps.

7. Medieval RabbitsRabbits were of utmost importance in medieval Britain, as they were sought after for their soft fur and delicious meat. When rabbits were first introduced in Britain, they had to be reared in specially-created warrens, as they could not stand the wet British climate at first. Rabbits were not able to freely colonise the countryside until the 18th century! Due to their high value, rabbits belonging to manor houses were guarded jealously against poachers, but by the 14th century efficient and ruthless gangs of poachers were adept at their craft, and poaching, particularly in rural areas, became hard to defend against.

8. Brainy BunniesAdult rabbits are capable of neurogenesis, on a higher level than other mammals, such as rodents. Studies of rabbit brain activity have found evidence of neurogenesis in the hippocampus, the striatum, and the cerebellum. The exact biological reason for this trait is unknown, although it is believed to be linked to the evolution of rabbits, giving them an advantage in the survival of the fittest.

Featured image credit: “Rabbit Hare Animal” by 12019. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Animal of the month: 8 facts about rabbits appeared first on OUPblog.

Dental students and the smell of fear

Human communication takes many forms, but picturing humans using chemical mechanisms to send messages leaves us skeptical. However, this concept becomes more plausible when we think of communication mediated via pheromones in animals. If we can accept that mice developed mechanisms to recognize the odor of a cat (and consequently be frightened by it), why is it so incredible to think that humans have adapted a similar sensory communication system to interpret and react to the scent of fear?

Laboratory-based research has increasingly revealed human sensitivity to the exposure to body odors—particularly sweat signals—which are produced by people undertaking emotional experiences. The most notable reactions are to negative experiences, like fear and anxiety. In other words, humans are able to emit body odors when they are stressed and scared that can be differentiated from the body odors they exude when they are disgusted or calm. Reactions to such chemical signals emerge in manifest behavioral changes, and when looking closely at physiological reactions and neural processing. However, we are rarely able to attribute such changes explicitly to the presence of a person’s body odor.

The majority of these lab-based studies have not yet tried to mimic a real-life situation, making it questionable whether chemosignal communication in humans is a lab epiphenomenon. To investigate whether body odors can signal someone’s anxiety in a more realistic setting, we designed an experiment based on a daily situation in which two people are in close contact—to allow the smell of the body odor to be perceived—and an activity to be performed, which can be affected by exposure to the body odor.

What better situation could there be for testing human responses to stress and fear than going to the dentist? Often, the possibility of a painful procedure induces significant anxiety in the patient, and they share the same peri-personal space with their dentist.

We recruited two groups of dental students: the first group (donors) volunteered to donate their body odors; the second group (recipients) performed a series of dental tasks on mannequins under the exposure of different odors. Body odors were collected under two conditions – from donors during a frontal lecture, with minimal involvement on their side, and during a clinical dental session which was likely to induce stress body odors.

Often, the possibility of a painful procedure induces significant anxiety in the patient, and they share the same peri-personal space with their dentist.

To make sure that smelling someone else’s body odor occurred in conditions similar to real-life exposure (thankfully the majority of us wear deodorant and perfume that can mask our unwanted sweat), we decided to mask the body odors collected from donors by spraying a common odor on the t-shirts. This “deodorant” is commonly found in dental clinics: clove oil. To make sure that the masking odor would not bias our data in a specific direction, we also used it to spray some clean, unused t-shirts.

The second group of students (recipients) were asked to perform three different dental tasks on mannequins dressed in the t-shirts from the three odor conditions: anxiety body odor masked with clove oil, rest body odor masked with clove oil, and clove oil alone.

When asked directly about the perceptual features of the odors, the students were not able to determine differences in their intensity and pleasantness. However, the results revealed that the performance of the students was significantly affected by the scent of the anxiety body odor compared to the other odor conditions. The reported mistakes included—among other things—increased likelihood of damaging teeth close to the operation site and treating a wrong tooth.

As demonstrated in the lab, exposing humans to emotional messages embedded in body odors triggers a simulation reaction: I smell your fear, I become stressed too. As we all know, stress tends to negatively impact our performances, particularly when we’re still inexperienced at the task in hand (as in the case of these dental students). Whether these effects are applicable to experienced professionals has yet to be determined. However, as with many other unconscious biases, being aware of the possibility of being subconsciously influenced helps us to take precautions against the negative consequences.

This study is the first of its kind to show that even in situations mimicking real-life experiences the presence of certain odors with embedded social messages can influence our behavior beyond our conscious control. Devoting efforts to uncover these sensory-based behavioral biases, identify the chemicals that selectively mediate these effects in humans, and evaluate the contextual conditions in which we allow the smell of fear to affect our behavior requires further scientific work. And, we believe, it’s a fascinating endeavor to undertake.

Featured image credit: Dental Repairs by rgerber. CC0 via Pixabay .

The post Dental students and the smell of fear appeared first on OUPblog.

September 7, 2018

A brief look at the post-WWII American military [excerpt]

From the ashes of World War II emerged two victorious superpowers: the United States and the Soviet Union. At the end of the war, America in particular was left with exceptional military strength, a monopoly on atomic weapons, and a home front intact. In the below excerpt from The American Military: A Concise History, Joseph T. Glatthaar explains the development of the American military in the years following World War II.

The United States emerged from World War II as the strongest nation in the history of the world. Never had one nation possessed such military and economic might. Its booming economy was essentially untouched by the violence, and it boasted an experienced military with a monopoly on atomic weapons.

Over the next three decades, the United States promoted its vision of the Atlantic Charter, hoping to transform the world into its own image. Painfully, the United States learned that its economic and military power were finite, and since the 1970s it has struggled to absorb that lesson.

Before the United States entered World War II, Maj. Gen. George Marshall had the Army create a manual on military government, and in April 1942 he established the School of Military Government to train occupation troops. When the United States agreed to oversee one of four occupied zones in Germany after the war, the Third and Seventh Armies had knowledgeable personnel for the initial occupation and the removal of Nazi officials from positions of authority. Trained troops quickly assumed greater responsibility for refugees, displaced persons, identifying and burying the dead, and administering services to the defeated population. In 1949, occupation ended when Britain, France, and the United States merged their zones to form the Federal Republic of Germany; the fourth zone, overseen by the Soviet Union, became the German Democratic Republic (East Germany).

“You put us in the Army and you can get us out. Either demobilize us or, when given the next shot at the ballot box, we will demobilize you.”

In Japan, the United States was the sole occupier, with MacArthur placed in charge. To ensure a peaceful transition, the United States permitted Japan to retain its emperor, despite his role in the war. By 1952, the United States turned over authority for rule in Japan to a civilian government. When Japan surrendered, the United States had more than 12.0 million people on active duty. The public and service personnel clamored for them to return home. Fortunately, the military had planned demobilization carefully. Although the most experienced personnel would rotate home first and damage the integrity of the command, it was fairest system they could contrive. By mid- 1946, only 1.5 million remained, a pace of demobilization that was still not fast enough for many. As one soldier wrote his congressman, “You put us in the Army and you can get us out. Either demobilize us or, when given the next shot at the ballot box, we will demobilize you.”

The war had pulled the United States out of the Great Depression, and many people feared a relapse when the war ended. To avoid a flood of returning veterans in search of jobs, the government passed the G.I. Bill, which offered them benefits such as free college tuition, a livable stipend for schooling, and low- interest home and business loans. The legislation eased the transition from a wartime to a peacetime economy and offered education and opportunity for millions who otherwise would never have had them, laying the groundwork for economic mobility.

Neither the Truman administration nor the military had any intention of reverting to the late 1930s conditions in size or structure. The administration wanted a military strength of 1.5 million, and the draft expired in 1947. To fill the dwindling ranks, Congress instituted a peacetime draft in 1948. The policy marked a dramatic shift from a military that depended on mobilizing citizen- soldiers to one that focused on readiness to deploy.

The war highlighted some serious weaknesses in the defense establishment. Various intelligence- gathering elements, for instance, had failed to share information prior to Pearl Harbor. The government sought to rectify such weaknesses with the passage of the National Security Act of 1947, which established the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) to oversee the collection, analysis, and dissemination of intelligence. For nearly three decades, the Army aviators lobbied for independence, and their contributions in World War II, along with reliance on the atomic bomb for defense, ensured the creation of an independent air force.

World War II also demonstrated the complexity of warfare and the need for greater cooperation among the services. The Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) had secured collaboration among the services in planning, but battles such as Leyte Gulf indicated the need for better joint cooperation. The 1947 legislation made the JCS permanent and created a National Military Establishment under a secretary of defense to improve joint planning and operations. Finally, the law created the National Security Council, which brought together the central players of national defense and security, such as the president, the JCS, the secretary of defense, the CIA director, the secretary of state, a national security adviser, and various cabinet members as needed. The legislation marked the beginning of a dramatic shift of power in peacetime away from the State Department and to the military and national security sphere. It also paved the way for new military schools that emphasized joint operations, such as the National War College, and think tanks that brought in civilian experts to advise and solve problems.

Featured image credit: US Army paratroopers by US Department of Defense. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post A brief look at the post-WWII American military [excerpt] appeared first on OUPblog.

Can “ultra-brief” mindfulness reduce alcohol consumption in heavy drinkers?

Scientific interest in mindfulness has grown exponentially since the 1980s. Clinical researchers have been asking whether these practices—which are based on ancient Eastern (Buddhist) contemplative traditions—can be used as psychotherapeutic techniques to ameliorate depression, chronic pain, and addictive behaviour.

Mindfulness is commonly defined as a way of paying attention, non-judgmentally, to one’s current experience. Despite this apparently simple definition, psychological treatments based on mindfulness meditation are often complex and multifaceted, meaning that they contain a number of distinct components that engage multiple, distinct psychological processes. For example, mindfulness interventions for drug and alcohol problems combine cognitive behavioural strategies with a variety of meditation exercises, such as the “body scan,” “awareness of hearing,” and “loving kindness” meditation. These exercises themselves differ in the degree to which they emphasise two styles of meditating: focused attention and open monitoring . Finally, these techniques and styles of meditating are practiced over a number of session in a group setting, so patients also experience a supportive environment, in which they can share experiences and learn from others.

Given the multiple components of mindfulness interventions, it is difficult to parse the specific contribution of their individual elements to their overall efficacy. Some of these components might be more necessary (or more efficacious) than others. If we can determine that certain aspects of a complex integrative treatment such as MBRP have beneficial effects in their own right, it might be possible to distill these into more efficient, abbreviated treatments.

We recently conducted a tightly controlled laboratory experiment in which we aimed to examine the relatively isolated effects of one style of meditating, namely open monitoring, on the response of heavy drinkers of alcohol. Since the total duration of the meditation instructions, within the experimental sessions, was only 11 minutes, we described this as “ultra-brief” mindfulness training.

…mindfulness interventions for drug and alcohol problems combine cognitive behavioural strategies with a variety of meditation exercises, such as the “body scan,” “awareness of hearing,” and “loving kindness” meditation.

What were the main findings of the study?

Compared to participants in the control group, who were instructed to relax in response to alcohol craving, those in the mindfulness (open monitoring) group showed a reduction in drinking over the following week, equivalent to a bottle of wine less than the control group.

Neither group showed changes in consumption immediately after the mindfulness/relaxation instructions (during a fake “taste test”), suggesting the effect only emerges after some practice.

Why did you study the effects of an “ultra-brief” form of mindfulness when most of the evidence suggests you need to practice for a long time before you see any benefits?

The brief nature of the audio-recorded instructions used in our study was simply a by-product of looking at only a single aspect of mindfulness, rather than a more complete intervention. Our instructions did not, for example, emphasise “focused attention” (focusing on a specific internal sensation or external object during meditation), which often precedes open monitoring. Instead, we repeatedly asked participants to “notice” what was going on in their mind and body while craving alcohol, and to simply observe and label these experiences without trying to change them. Although the participants only practiced the open monitoring technique very briefly in the experimental session, they were also given a small instruction card reminding them to practice the technique they’d been taught for the next seven days, whenever they experienced alcohol craving.

What are the implications of your study for treating alcohol problems?

It is premature to be considering treatment implications, but our findings do suggest that it may be worth pursuing research on abbreviated forms of mindfulness interventions, at least in people who recognise they drink too much but are not severely addicted. It seems very unlikely that such a brief approach would be effective in people with more severe drug or alcohol problems. For these individuals, more intensive treatments, including medical management along with evidence-based psychosocial treatments (e.g. MBRP) during the relapse prevention phase, will likely continue to be the preferred approach.

Featured image credit: Night-life by mossphotography. CC0 via Unsplash.

The post Can “ultra-brief” mindfulness reduce alcohol consumption in heavy drinkers? appeared first on OUPblog.

What type of choir director are you?

Think about the choir directors you’ve had in the past. What were they like? Each one likely had a different approach to leading, conducting, and communicating. What makes a great leader? Which communication style is most effective?

Let’s begin with leadership style.

Determining your leadership styleHow do you interact with others? Writer David Jensen described two types of people: open and reserved.

According to an article by Jenson on behavioural style, ‘Open people…are willing to reach out and touch. They will use a lot of eye contact and expression to communicate.’ If you’re an open leader, people may describe you as easy to work with, agreeable, friendly, and caring.

By way of contrast, Jenson then goes on to say that ‘Reserved people ‘will hold back on disclosing anything that might give clues to their inner nature.’ If you’re a reserved leader, people may describe you as thoughtful, intentional, dedicated, and doing high-quality work.

Where do you fall on the spectrum?

Determining your communication styleHow would you describe your communication style? Here are four interesting ways to look at communication styles, as suggested by ‘Straight Talk’,

Director: You are goal-oriented, a risk-taker, driven, and focused. You often communicate in a quick, direct manner.Expresser: You are creative, an expressive story-teller, dynamic, and enthusiastic. You often communicate by explaining and describing things in detail.Thinker: You are detail-oriented, a problem-solver, intentional, and thorough. You often communicate by asking questions, then giving specific feedback.Harmonizer: You are quiet and thoughtful, a conflict-avoider, and care deeply about the people you work with. You often communicate only when needed, in a gentle manner.Which one resonates with you?

Understanding the type of choir director you areDetermining your leadership and communication styles are important to figuring out what type of choir director you are. To help illustrate this, I put together four character profiles. Can you relate?

The artist

You are well-trained in music history, theory, and literature. Creating beautiful music is your top priority. You feel things deeply and may get offended when others don’t seem to care as much as you do about the art form, but people respect you and your opinions.

Leadership style: Reserved

Communication style: Thinker

Strengths: You are committed to excellence, hard-working, and dedicated.

Weaknesses: You may be perceived as closed off and not relatable.

The organizer

You are driven, structured, and attentive to details. You plan ahead and are always prepared. Your rehearsals are planned to the minute. You have systems and strategies for teaching new anthems, reviewing parts, and developing vocal technique. Some may resist this amount of structure, but you get results.

Leadership style: Reserved

Communication style: Director

Strengths: You are driven and provide structure for learning and achieving goals.

Weaknesses: You may be perceived as inflexible, strict, or high-strung.

The entertainer

You want choir to be fun. You want to win the affection of your choir members, so you try not to ask too much of them in rehearsal. Some may consider this a laissez-faire (“let them do” in French) approach, but you want people to feel comfortable and see you as an equal.

Leadership style: Open

Communication style: Expresser

Strengths: You are friendly and easy to be around and create a relaxed environment.

Weaknesses: You may be perceived as lax, lacking initiative, or not committed.

The facilitator

You enjoy working collaboratively with your choir. You seek their input and value their opinions and ideas. You work together to develop a strategy to address something you’re working on. You see yourself as a learner as much as a teacher sometimes.

Leadership style: Open

Communication style: Harmonizer

Strengths: You empower others and create a thoughtful learning environment.

Weaknesses: You may be perceived as less knowledgeable or lacking the ability to take charge.

The purpose of these illustrations is to help you think about your leadership and communication style and develop the flexibility you need to lead and serve your choir well. Note the strengths and weaknesses for each; how does this inform your work?

Learning how others communicateFinally, it’s important to learn how others communicate and receive information, especially in group settings, as you’ll likely have many communication style preferences within your choir. How do you communicate effectively in a way that reaches everyone?

The secret is learning to be flexible. According to an article by Carnicer, Garridom, and Requena, published in the International Journal of Music and Performing Arts (June 2015, Vol. 3, No. 1, pp.84-88) ‘Good leaders are able to adopt and combine different styles of leadership to improve the welfare and efficacy of the group they lead’. The key is learning to recognize what your choir needs when and adapting in the moment.

What leadership or communication strategy has helped you become a more effective leader?

Images provided by Mohamed_Hassan. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

Featured image credit: Leadership, illustration by Geralt via Pixabay.

The post What type of choir director are you? appeared first on OUPblog.

September 6, 2018

Religion and literature in a secular age

There is a long history of people exploring the relationship between religion and literature. We might go back to sacred texts from different traditions and think, for instance, about why there is such a vast array of literary forms in the Judaeo-Christian Bible. Or we might consider the role that religion plays in the literary tradition, from the clear Christian content of texts such as The Divine Comedy and Paradise Lost, to the extensive engagement with theological motifs, symbols, and ideas that is such a striking feature of so many modern texts.

While there are many ways of telling a story about how religion and literature relate to one another, it is worth pondering why our thinking about this relationship continues to gather pace. The latter part of the 20th century saw the emergence of three major journals focused on this area—Religion and Literature, Christianity and Literature, and Literature and Theology—and interest has intensified further in the early years of the 21st century with the so-called “religious turn” in the humanities. If our modern western age is increasingly secular, as many would have us think, then why the ongoing interest?

One way of answering this question comes from the work of Charles Taylor, whose book A Secular Age (2007) has proved so pivotal for many scholars working in the humanities. Taylor argues that our secular age is not one in which religion has gone away but is, rather, an era characterised by the new position in which religion now finds itself. Whereas pre-modern western thought saw Christianity ensconced as the dominant ideology, our modern age is one in which religious belief is one option among many.

Taylor argues that our secular age is not one in which religion has gone away but is, rather, an era characterised by the new position in which religion now finds itself.

Taylor’s epic story of religion and secularity has come in for plenty of criticism, as one might expect of a work that tries to cover so much historical ground. But his basic premise about the pluralised context for belief in the modern age offers a valuable means of understanding the snowballing interest in the study of religion and literature. Literature has long been the most promiscuous of forms, covering any area of thought and experience with which a writer happens to be concerned. Since the emergence of literary studies in the late-19th century, critics have struggled to identify the precise content of the discipline, and they have frequently brought neighbouring fields of knowledge—history, psychology, philosophy, science, art, religion, and so on—into their reflections on literary form and language. The promiscuity of literature, and the literary criticism that accompanies it, might be said to epitomise our modern secular age. And it is in this setting that religious belief continues to play a major role, as it is routinely put into conversation with other ways of thinking.

We can see how Christianity sits alongside and butts up against other systems of belief in the novels of Charles Dickens. Critics have long debated whether Dickens should be thought of as a religious writer, and one can see why this question has proved hard to resolve. Dickens can be highly critical about parts of the church, and it is certainly not the case that his novels are written with pious ends in mind. But it is hard to think of another Victorian writer who quotes from the Bible and the Christian tradition more extensively. Many of the most poignant moments in his novels, from the death of Jo in Bleak House as he is led in a recital of the Lord’s Prayer, to the climactic role given to ideas of atonement and resurrection in A Tale of Two Cities, are indebted to Christian thought. The sacred and secular are regularly commingled in Dickens’s fiction. What we find in his work, as in so much modern western literature, is the myriad of ways in which the Christian faith jostles with other systems of belief. Untangling these different threads can be difficult, and it would be a mistake to think that the sacred and secular can ever finally be separated. But their intersection and crossover in modern western literature is worth closer examination. Those who want to explore the relationship further, whether with reference to Christianity or other religious traditions, might usefully start with the three journals mentioned already as well as two recent edited collections: The Cambridge Companion to Literature and Religion (2016) and The Routledge Companion to Literature and Religion (2016).

Featured image credit: Book by Mikali. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Religion and literature in a secular age appeared first on OUPblog.

Are casual hookups sexually empowering for college women?

A note from the editor:

Dear reader: Dr. Jennifer Beste is the College of Saint Benedict Koch Professor of Catholic Thought and Culture at the College of Saint Benedict and Saint John’s University. She is author of College Hookup Culture and Christian Ethics: The Lives and Longings of Emerging Adults (Oxford University Press, 2018) and God and the Victim: Traumatic Intrusions on Grace and Freedom (Oxford University Press, 2007). Her areas of teaching and research include trauma theory and Christian theology, sexual ethics, and children, justice, and Catholicism. She enjoys traveling to universities to share her research on hookup culture and sexual assault on college campuses. All names used have been changed to protect student anonymity.

If you are interested in this topic, you might want to also listen to “A podcast with Jennifer Beste by OUP Academic” which features Dr. Beste further discussing her research.

Yours truly,

The OUPblog Editor

ursuing this question in conversation with undergraduates inside and outside of the classroom for over ten years, I have found that the vast majority of young women experience hookup culture as disempowering. This conclusion is supported by a growing number of social scientists, but the evidence I will share below comes from my own experiences with college students. Here is a sampling of my findings, along with representative student quotations taken from my qualitative research.

My first major research in the area of hookup culture was a three-year project in which a graduate student and I interviewed college sophomores, juniors, and seniors who volunteered to share their honest perspectives and experiences of hookups. Hundreds of students each year added their voices to the project, with many choosing to do so anonymously. Amanda, the only woman during three years of interviews to report a positive overall experience of hookups, attributed this to being careful and deliberate about hookup partners and behaviors, and not letting her friends influence her too much:

Though I value their opinions, it’s important that I think for myself, that I make my own decisions based on my own values and based on how I project that I will later feel about my decisions.

In another research study, spanning another three years, students in my sexual ethics courses became sober ethnographers who observed and analyzed college parties. Asked to pay attention to power dynamics between different groups, the majority of students perceived that white, heterosexual men were the most dominant group at parties. And asked to observe how men’s and women’s bodies were depicted and treated, my students noted ways that sexual objectification of women in hookup culture erodes women’s self-esteem and agency:

A student named Mike echoed many ethnographers’ perceptions when he wrote:

Men were seen as the pursuers. They were the hunters in this situation, going out to find a girl that they want. The girls of course were the hunted. This gives power to the guys; the hunters are seen as the people who control the situation and ultimately the outcome.

When asked whether they thought their peers were happy at college parties, 10% of my ethnographers said yes, usually citing the positive influences of alcohol as evidence. 90% perceived that their peers were dissatisfied overall with hookups and party culture, especially if you include the morning afterwards when they wake up sober.

According to women in the study, the top four reasons for dissatisfaction were 1) a sense of emptiness and/or loneliness post-hookup, 2) disillusionment and hurt (the ideal of an emotionless, unattached hookup rarely happens in reality), 3) depression and loss of self-esteem, and 4) negative sexual experiences, including assault.

My third research project, another three-year venture, was conducted at a different university than my first two. This time, I engaged in a qualitative analysis of 150 students’ reflections about whether it is possible for hookups to be ethically just. A minority (18% of women and 26% of men) responded that a hookup could be just if free consent, equality, and mutuality are present during the hookup, and if both partners feel positive afterwards. In contrast, 81% of women and 68% of men perceived that hookups fail in reality to be just because it is highly unlikely that respect, free consent, equality, and mutuality would actually be present.

[1]Why is this?According to many male students, since hookup partners don’t know each other well or feel connected with their partner, they aren’t motivated to care about communication, mutuality, and equality. One male student wrote anonymously:

In a hookup, the sexual activity would be extremely skewed in terms of mutual sex. The possibility of negative ramifications resulting from non-mutual sex are so low that one person is almost always going to take advantage of another person because there was no sort of prior relationship. Both parties do not really owe each other anything, which poses a great risk for unequal sex.

Female respondents agreed, emphasizing that most hookup sex is “guy sex” that is focused solely on satisfying the man’s desires and pleasure. One anonymous female student said:

Many women feel they cannot say no to males, or they don’t want to make the male feel bad if they are uncomfortable with a situation. I think that women may also perform certain sexual acts even if they don’t want to because they don’t want to be labeled as stiff and get a bad reputation. It can be easier for women to just be submissive and let the male do whatever he pleases even if she may be uncomfortable.

When these students were asked in an anonymous survey what kind of sex (equal mutual sex or unequal, non-mutual sex) they found most desirable, arousing, and pleasurable, men’s responses were mixed while 100% of women described equal mutual sex as the most desirable, arousing, and pleasurable sex imaginable. In contrast, they used words like aggressive, demeaning, painful, humiliating, and terrifying to describe sex that was unequal and non-mutual.

Despite women’s preferences, both genders in the survey perceived that unequal, non-mutual sex, which takes place most frequently in hookups, is the most prevalent kind of sex experienced by college students. A female student wrote anonymously:

Of course unequal, non-mutual sex isn’t as desirable as equal sex, but I’m sure it occurs more often between people in our age group. Why? People want love, acceptance, sex, and companionship. But they can’t have it all, so some things have to give. And sometimes sex is that thing.

Readers, of course, will want to test their own knowledge and past experiences against the dominant themes that emerged from my engagement with undergraduate “insiders” at two different universities. From my own vantage point as professor and qualitative researcher, the prospect of women’s sexual empowerment through casual hookups is bleak—unless we have so regressed as a society that women’s empowerment has been rebranded as a “momentary boost” in self-esteem from performing sexual favors and receiving temporary male approval.

[1] The percentage of student in this survey do not equal 100 because a minority of students did not directly answer the question.Dr. Jennifer Beste is the College of Saint Benedict Koch Professor of Catholic Thought and Culture at the College of Saint Benedict and Saint John’s University.

Featured Image Credit: “Woman” by StockSnap. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Are casual hookups sexually empowering for college women? appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers