Oxford University Press's Blog, page 183

July 14, 2019

Nell Blaine, the artist who wouldn’t allow disability to cramp her style

After I mentioned to someone that I was writing a biography of a leading painter who contracted a severe form of polio but taught herself how to cope with her disability, he said, “So she painted with her feet, right?”

It seems that people have a hard time coupling excellence in art and disability without imagining some sort of freakish practice that we must look upon kindly because This Is The Best They Can Do.

The wonderful and amazing thing about Nell Blaine—whose polio attack came at age 37, during what appeared to be the peak of her career—is that the work she made afterward is far superior to the earlier paintings.

Blaine, who was born in 1922 in Richmond, Virginia, and escaped to New York at age 20, was initially in thrall to the rigorous abstraction of Dutch painter Piet Mondrian. But her fascination with the objects of the real world kept breaking through. For example, in Lester Leaps (1944–45), a tribute to the jazz musician Lester Young, a shape at the upper right looks unmistakably like a baton in the hand of a bandmaster. Then, on a trip to Europe in 1950, Blaine discovered a new freedom in sketching landscapes in Paris and Rome.

Despite the dominance of Abstract Expressionism in New York in the 1950s, she realized that her heart was in a different kind of painting: landscapes and interiors. But first she had to figure out how to achieve a viable personal style. In many of her works from the late fifties, brushstrokes have a tentative, unresolved look, as if she was still persuading herself of the value of representational art. Even so, the Whitney Museum of American Art purchased one of her paintings, Harbor and Green Cloth II (1958) in 1959.

That was the year Blaine had made enough money from her graphic design work—side jobs that she needed to earn a living—to fund a trip to Greece. She had heard that government-run studios on the island of Mykonos rented for a pittance. They did, but hers was very cold and lonely. Never at a loss for making friends, she soon found more congenial lodgings with two gay Americans, where she could paint the majestic view from the windows of her room.

In letters to fellow painter Jane Freilicher, she described her island sojourn in glowing terms. But she had begun to feel strangely weak. After a collapse, her worried friends called a local doctor, who diagnosed the flu. Fortunately, they also called a visiting German doctor, who realized that Blaine had actually contracted the most severe type of polio. Near death, she was airlifted to a New York hospital, where she spent months in an iron lung. While some people stricken with polio were left with no more than a limp, Blaine became paraplegic.

Her watercolors, in particular, would rank with the greatest American masters of the medium.

Told that she could never paint again, she characteristically rebelled. During the long months of her rehabilitation, Blaine decided to invest the energy she would have needed to learn how to walk into redeveloping her painting skills. Her first post-polio artwork was a shaky drawing of flowers, dedicated to her nurse, with whom she had fallen in love. (Bisexual in her pre-polio life, she would rely for the rest of her life on the intimacy and all-encompassing care of the two women with whom she had successive relationships.)

In the years that followed, she trained herself to use her left arm for oil painting and her right arm for watercolor. Although Blaine could no longer work on a large scale or finesse tiny details, she developed a coloristically rich, rhythmically vibrant style that gave landscapes and still lifes a unique beauty and visual intensity. Her watercolors, in particular, would rank with the greatest American masters of the medium.

During the remainder of Blaine’s life, her paintings were shown in leading galleries and reviewed with the encomiums reserved for outstanding work. A facsimile of her sketchbook, published in 1986, contained a tribute by her longtime friend, the poet John Ashbery. He praised “the sensuality … backed up by a temperament that is crisp and astringent, which is as it should be, since even at its most poetic, nature doesn’t kid around.”

Featured image: Nell Painting Autumn Afternoon in Gloucester, Mass., 1994. Photo by Carolyn Harris. Used with permission.

The post Nell Blaine, the artist who wouldn’t allow disability to cramp her style appeared first on OUPblog.

July 13, 2019

How austerity politics hurts prisoners

The Battle of Dunkirk–the 1940 allied evacuation of 338,226 Belgian, British, and French troops from the beaches of Northern France–has been continually accentuated as a critical moment of the World War II. In “a miracle of deliverance,” as Winston Churchill, the then-prime Minister called it, hundreds of thousands of soldiers came together in a resourceful feeling of togetherness. Today, Dunkirk remains a symbol of determination against adversity.

Seven decades later, the country has to weather another battle, albeit against a different enemy. In May 2010, after a series of financial failures in the United States and Europe–such as the insolvency of the Northern Rock Bank, collapse of Lehman Brothers, financial deceit in the US mortgage market, and large-scale bank bailouts–the coalition government adopted austerity measures. It did so in an effort to both reduce the public sector deficit in the short term and to maintain confidence in the country’s financial stability in the long term.

Yet, the politics of austerity, however deeply entrenched in the popular national memory, has failed to reignite the spirit of Dunkirk. The dramatic impact of austerity on those who are acutely reliant upon public services–those who are poor, marginalised, and excluded–is too visible to ignore. Regrettably, this phenomenon remains to be under articulated. This harmful effect of austerity on prisoners—a cohort that, to a greater extent than the general population, suffers from physical and mental ailments, as well as from rampant poverty and deprivation, should not be ignored.

Austerity is a political choice, rather than an economic imperative. Severe cuts to national finances of Greece, Ireland, and Portugal were part of their recovery plans. In the UK case, however, while the country was not a member of the Eurozone, our politicians went ahead with the stringent bailout conditions that were similarly imposed on Greece, Ireland, and Portugal by the Europe Commission, the European Central Bank, and the International Monetary Fund (the Troika).

Large spending cuts across public programmes were didactically introduced to cover the burgeoning deficits without raising taxes. The prison budget was reduced by 22%–£0.8 billion–leading to a 30% reduction in the number of frontline prison officers—even as incarceration rates plateaued. This has seriously compromised the resilience of prison health agenda, as its delivery is largely depending on a stable prison regime.

Getting no direct benefits from financial bailouts, prisoners have to bear the disproportionate brunt of austerity. With 155 prisoners per 100,000 population, England and Wales have the highest incarceration rate in Western Europe. This record imprisonment rate, despite the abated crime rates, remains broadly consistent, dovetailing the tough stance on crime and longer sentences. Moreover, contrary to the government cost-saving ambition during the time of recession, the hefty price tags of prisons–£38,042 per person–have not explicitly featured in any political debates.

While prisons are often the last bastion for prisoners to address their health and welfare needs, they are no longer able to withstand austerity with fortitude. Fragmented access to prison healthcare, exacerbated poor living conditions, hindered participation in purposeful activities, and increased level of violence have become the norm. In 2018, mere 17% prisoners—fewer than two out of ten—were released from their cells for at least 10 hours a day to participate in education, employment, and training sessions. Between 2010 and 2018, suicide, self-harm, and assault rates in English prisons increased by 23%, 47%, and 52% respectively.

These statistics contradict the election pledge that prisons should be “places where people are helped to turn their lives around.” The current prison conditions not only progressively harm physical and mental health, but also create inhumane conditions to live in, making prisons places of double punishment where detainees are unable to articulate their needs, make decisions, and or advocate for their rights.

The first step towards reviving the Dunkirk spirit of solidarity that once emerged in the national consciousness is challenging the misnomers of austerity and imprisonment. The path forward shall be paved by using alternatives to imprisonment, revisiting sentencing practices, using a more informed economic recovery approach, introducing intergovernmental and non-governmental monitoring of the compliance that health standards should not be breached, as well as by naming and shaming human rights violators. To come back to our roots of humanity and unity embodied by Dunkirk, and to springboard honest conversations about the right of prisoners to have better lives, we will need to critically challenge the use of austerity in imprisonment.

Featured image credit: “corridor” by Matthew Ansley. Public domain via Unsplash.

The post How austerity politics hurts prisoners appeared first on OUPblog.

July 12, 2019

The evolution of the book to the digital page

With summer holidays looming and suitcase space tight, I recently bought myself a Kindle. The e-reader is now available in a variety of models pitched at a variety of price points. Mine is called a Paperwhite. The name, like much about the digital reading experience, looks to elide the gap between reading on paper and reading on a plastic screen. When the device is locked, it displays one of a series of holding images that hark back to pre-digital text technologies: a clutch of pens, a galley full of moveable type, the ink bleed of a manuscript letter in close up. The born digital nature of most writing today can feel like something of a dirty secret.

At the same time, there are perfectly good reasons for skeuomorphic design, that is, when new technologies ape aspects of the older ones they are displacing. It makes the transition between technologies more comfortable, the learning curve shallower. The first printed books often preserved manuscript features – illumination or rubrication, for example – in order to appear less alien to their late medieval readership. Perhaps the most obviously skeuomorphic feature of my new e-reader is the way that the text is divided into a series of pages, like an old-fashioned book, rather a single scrolling block, like this blogpost. I don’t think I’m ready to read a novel that isn’t divided into pages. I can’t quite say why, but I suspect I’m not alone in this.

I don’t think I’m ready to read a novel that isn’t divided into pages. I can’t quite say why, but I suspect I’m not alone in this.

If I fire up Pride and Prejudice the screen looks reassuringly familiar. Yes, there’s the famous opening – “It is a truth universally acknowledged…” – but also, above it, in large, centred lettering, generously framed in whitespace, Chapter One. The page layout is comfortingly bookish. What’s more, if I want to, I can pull up the book’s front matter: title page, table of contents, introduction – all parts of the book that have their own long backstories. But when I follow the link labelled Copyright Page the illusion starts to glitch. Copyright pages have a chequered history. They are something of a ragbag – a bundle of dates, legals, and cataloguing info, thrown together and printed on the reverse of the title page – but they tend to fit on one page. It’s in the name. Not here though. Even if I fiddle with the settings, choosing the smallest font and the meanest margins, this page runs over two screens.

So my device isn’t great with page numbers. This has been a high profile issue since e-readers made their first appearance. But let’s remember that page numbers are not timeless. You hardly find them at all in the middle ages, for much the same reason that they make don’t sense on a gadget with resizable fonts. When every book had to be copied out by hand, the page number didn’t offer a standard measure. Your copy of a work might have been written out on larger sheets than mine, or in smaller handwriting, or with illuminations or double-sized initials that mine lacked. Any pagination would then be copy-specific: it wouldn’t provide a transferable reference that could be shared among a dispersed reading community. Only with the arrival of the printed edition did that become possible. For referencing, it was more useful to have a locator based on some feature of the work itself, such as dividing a work into chapters, with the standard chaptering of the Bible accomplished by Stephen Langton around the turn of the thirteenth century.

Returning to Pride and Prejudice, my Kindle is certainly reproducing that novel’s chaptering, but it’s also offering me something else to make up for the lack of page numbers. Down in the bottom right of the screen is a percentage. The device has divided my book into a hundred equal parts so that it can tell me what proportion I’ve read. This isn’t such a new idea either. The Dominican friars of thirteenth century Paris, looking for a more granular locator than Langton’s chaptering, would divide each chapter into equal sevenths which could then be referred to by a letter from a to g. In the beginning…? Genesis 1a. Jesus wept? John 11d.

What about “Time left in chapter” – my device’s other way of situating me within a work? It feels rather novel, to have our reading presented to us in terms of duration, rather than having to estimate this ourselves based on metrics of length. Still, perhaps the chapter itself has always had one eye on the clock. In his novel Joseph Andrews (1742), Henry Fielding pictures his readers as hard-pressed but conscientious scholars in need of some light relief. They read novels in snatches of half an hour before diligently returning to weightier matters. And if the chaptering isn’t calibrated to this thirty-minute breaktime, Fielding reasons, they will find themselves adrift midchapter, thereby “spoiling the beauty of a book by turning down its leaves”. Not a problem for me, thankfully, with my skeuomorphic bookmark. Just as well, since the e-reader does not – yet – come with foldable corners. Not even on the Paperwhite.

Feature Image Credit: “e-reader” by Amanda Jones. Free use via Unsplash.

The post The evolution of the book to the digital page appeared first on OUPblog.

July 11, 2019

Standing in Galileo’s shadow: Why Thomas Harriot should take his place in the scientific hall of fame

The enigmatic Elizabethan Thomas Harriot never published his scientific work, so it’s no wonder that few people have heard of him. His manuscripts were lost for centuries, and it’s only in the past few decades that scholars have managed to trawl through the thousands of quill-penned pages he left behind. What they found is astonishing—a glimpse into one of the best scientific minds of his day, at a time when modern science was struggling to emerge from its medieval cocoon.

It was a time when many still believed in magic, and most of the methods of science and mathematics that we take for granted today had not yet been developed. For instance, calculus had not yet been discovered, and there was no formal understanding of infinite series. But Harriot was one of the best algebraists of the early seventeenth century, and he managed to make a number of pioneering mathematical discoveries—including some that anticipated calculus and limit theory. These discoveries enabled him not only to make advances in pure mathematics, they also enabled him to apply mathematics to various practical and theoretical problems.

There are many reasons that Harriot never got around to publishing his scientific work, not least the dramatic times in which he lived. He moved in the most glamorous of Elizabethan circles—the charismatic Sir Walter Ralegh was his patron; but stars often fall, and when Ralegh fell from grace, Harriot’s fortunes suffered, too.

But at the beginning of their association, Harriot and Ralegh’s lives were full of excitement and hope. After graduating from Oxford, Harriot’s first job was that of live-in navigational advisor during Ralegh’s preparations for the first English colony in America.

He began his new employment in 1583, when England was a tiny player in maritime commerce and geopolitics. If Ralegh’s planned American trading colony were to materialize, his mariners would have to sail safely across uncharted oceans with the sky as their only guide, and Harriot provided them with the best training then available. Which was just as well for Harriot, too, because in 1585 he sailed to Roanoke Island with the First Colonists.

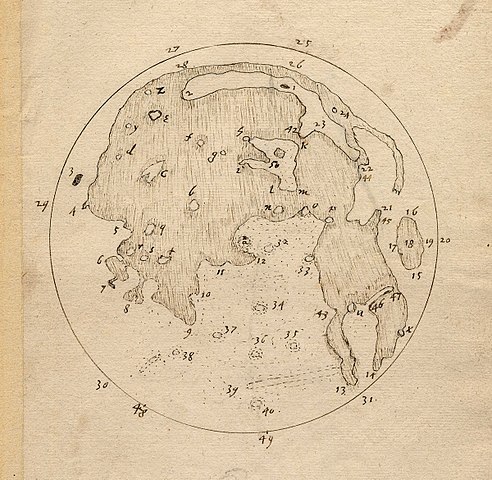

Image credit: Drawing of the Moon’s surface showing craters by Thomas Harriot, preceding Galileo’s observations. Public domain via

Wikimedia Commons

.

Image credit: Drawing of the Moon’s surface showing craters by Thomas Harriot, preceding Galileo’s observations. Public domain via

Wikimedia Commons

.He saw the Roanoke people as friendly and ingenious, and found their way of life appealing in many ways. Tragically, few of his fellow travellers were so open-minded. When food supplies eventually ran low, and illnesses unwittingly brought from England struck down many of the local people, tensions between the visitors and their hosts reached breaking point. The First Colonists abandoned their experiment and returned to England—having killed the chief who had earlier invited them to share his land.

The disaster at Roanoke seems to have weighed heavily on Harriot. Although he continued as navigational advisor to Ralegh’s follow-up ventures, he never sailed to America again.

Instead, he began to turn towards more detached scientific pursuits. Initially, these included original mathematical research with navigational applications, but later, he explored science and mathematics simply for their own sake. He explored almost every area of the mathematics and physics of his day, and he made a number of breakthroughs that today we link with others’ names.

He found the law of falling motion independently of his contemporary Galileo, and used a telescope to map the moon and the motion of sunspots, again independently of Galileo. He discovered the law of refraction before Snell, produced a fully symbolic algebra and fledgling analytic geometry before René Descartes, found the secret of colour and the nature of the rainbow before Isaac Newton, and the rules of binary arithmetic before Gottfried Leibniz—to name just a few of his many achievements.

If only he had published all this work! Unfortunately for early modern science, he had little interest in fame. But the vagaries of a life spent working for controversial patrons didn’t help. First Ralegh, and then Harriot’s second patron, the earl of Northumberland, ended up imprisoned in the Tower of London on false charges of treason. Harriot himself came under suspicion. For instance, his renown as an astronomer led to the false accusation that he had cast a horoscope to aid the Gunpowder Plotters.

Yet despite all the ups and downs his curiosity remained undimmed. Four centuries on, he deserves to be celebrated for the decades he devoted to scientific discovery. Although this means he should take his rightful place in the scientific hall of fame, it is refreshing, at this time when we are awash with celebrities, that Harriot did much of his work just for the love of it.

Featured image credit: Night sky in Hatchers Pass, Alaska. Photo by McKayla Crump. CC0 via Unsplash .

The post Standing in Galileo’s shadow: Why Thomas Harriot should take his place in the scientific hall of fame appeared first on OUPblog.

July 10, 2019

From rabbits to gonorrhea: “clap” and its kin

Three years ago, I discussed the origin of several kl– formations, all of which were sound-symbolic: kl- appeared to suggest cleaving, cluttering, and the like. In this context, especially revealing is the etymology of cloth (see the posts for June 29, 2016 and August 10, 2016). The problem with such consonant groups is that there is rarely anything intrinsically symbolic in them. Why should kl- suggest clinging and clustering, rather than cloying or clobbering? Actually, it does both. In this hunt, one never knows where to stop, and researchers are often carried away by the tempting similarity of numerous words that may or may not have anything in common.

Yet this is probably how language originated. No one strove for consistency. Words were born out of chaos. Ancient people’s erratic habits keep language historians busy. To complicate matters, sound-symbolic formations are more or less universal and do not obey so-called phonetic laws (correspondences). Finally, even if we have explained the first two sounds of the word correctly, we still have to account for the rest of them. Granted, cl– in clover (one of the words I discussed) makes sense, because the juice of the plant is sticky, but what about –over? The same question should be asked about every word under discussion.

Cl- is fine, but what is -over? In clover by Robert Couse-Baker. Flickr, CC BY 2.0.

Cl- is fine, but what is -over? In clover by Robert Couse-Baker. Flickr, CC BY 2.0.Since groups like kl-, gl-, pl-, and the rest do not mean anything in and of themselves, they can be used for many purposes. We are on safer ground when it comes to sound imitation (onomatopoeia). Our vowels and consonants are not suited to reproduce coughing, hiccoughing, sneezing, giggling, roaring, barking, and the rest, but we do what we can. Evidently, kl– ad gl– have been chosen for rendering loud noises. Clap is one of such words. It goes back to Old English and has close cognates all over the Germanic-speaking area. Modern German kläffen “to yap” is almost the same word. To be sure, flap, slap, rap, tap, lap (up), and even larrup “to thrash” might have been chosen to mean “give a sharp, forcible, or resounding noise.” Crap would perform this function even better, and another final consonant would do the work equally well (compare the obviously sound-imitating clatter). But, for some reason, the Germanic complex klap– won the day and even spread all over the Romance-speaking world. A typical clapper. Image CC0 Public Domain via Max Pixel.

A typical clapper. Image CC0 Public Domain via Max Pixel.

It is curious to observe how far the recorded meanings may deviate from the initial sound-imitating idea. Allegedly, some people think that pigs grunt klap-klap while eating; hence the dialectal French noun clapon “pig.” Shoes go clop-clop; hence French chapin (borrowed from Spanish) “shoe” (not a common but characteristic word). Yet, as noted, one should tread lightly, rather than rush clop-clop, here, for a lot can be suggested but little can be “proved” in this area. English dialectal clapholt designates small boards of split oak, cut to make barrel staves (the modern Standard word is clapboard). In northern Devonshire, a clapper is a wooden bridge across a stream. When we deal with splitting, a loud noise is natural. Clap “to strike” is also behind claptrap, originally a “trap” devised for causing applause.

Then we find Scots clappers “rabbit warren,” explained as being “sometimes formed merely of heaps of stones thrown loosely together.” Stones, naturally, tend to fall or come in contact with one another with a lot of noise. Strange, as it may seem, rabbits bring me to clap “gonorrhea.” In 1887, the German scholar Hermann Varnhagen published an informative article on the use of the Germanic root klap in Romance. His material is excellent and in my exposition, I have of course drawn on his results, but sometimes he seems to have let his enthusiasm carry him too far. Here is one more of his examples.

A warren. Is it the progenitor of a brothel? Photo by John Schilling via Flickr, CC BY-ND 2.0.

A warren. Is it the progenitor of a brothel? Photo by John Schilling via Flickr, CC BY-ND 2.0.In his opinion, rabbits’ fertility gave rise to Old French clapoir “brothel” and the venereal disease clap. Words for “brothel” are many and ingenious (see the post for January 15, 2014). Perhaps Varnhagen guessed well (compare cathouse “brothel”), but there may be a less complicated approach to the word. Clap “to strike,” like strike itself, was used in the Elizabethan days as a synonym for “copulate.” Assuming that similar usage enjoyed enough popularity in France, the name of the venereal disease would emerge as a result of sexual activity. Dictionaries trace the English word to Old French, cite the obsolete Dutch cognate, and conclude: “Of uncertain origin.” The origin looks rather obvious.

A house of sin, as depicted in the past. Brothel by Joachim Beuckelaer. Released to the public domain by the Walters Art Museum. Via Wikimedia Commons.

A house of sin, as depicted in the past. Brothel by Joachim Beuckelaer. Released to the public domain by the Walters Art Museum. Via Wikimedia Commons.In Hemingway’s novel A Farewell to Arms, we read that soldiers and officers used to go to different brothels. At the end of the story, the hero (Lieutenant [Tenente] Fred Henry) and Catherine have one of their staccato conversations: “What are you thinking about now?” “Nothing.” “Yes you were. Tell me.” “I was wondering whether Rinaldi had the syphilis.” “Was that all?” “Yes.” “Has he the syphilis?” ”I don’t know.” “I am glad you haven’t. Did you ever have anything like that?” “I had gonorrhea.” “I don’t want to hear about it. Was it very painful, darling?” “Very.” A young Ernest Hemingway. Public domain, modified by Fallschirmjäger. Via Wikimedia Commons.

A young Ernest Hemingway. Public domain, modified by Fallschirmjäger. Via Wikimedia Commons.

OF course, Hemingway could not care less for the etymology of the word, even though he knew the origin of the disease, and we needn’t trouble him any longer. Rather, we should return to my gleanings of August 29, 2018 (and don’t miss Stephen Goranson’s comments). In that post, in connection with the work jiffy, I wrote about a series of articles by the famous German philologist Wilhelm Braune and retold one section in the latest of them. Today I have to mention his early (1896) essay. I also suggested that Braune, most probably, had never seen Hensleigh Wedgwood’s works. But, strangely, he does not seem to have referred to Varnhagen’s well-known contribution either (Braune’s text is so dense that it is easy to miss something; hence my cautious tone), though his analysis runs along the same lines. In any case, both scholars examined not only kl– but also some gl-words denoting noises, and concluded that Engl. yelp is one of them. Old Engl. gielpan (pronounced as yielpan) once began with “real” g, as do all its cognates. There is nothing revolutionary in such a conclusion. Whoever has dealt with words like Engl. call (a borrowing from Scandinavian) and Hebrew kol “voice” agreed that the complex gol ~ kol denotes noise almost everywhere. In the world of onomatopoeia, the difference between kl and gl is of little importance.

Cliff, the last word to be discussed today, is the most controversial one, and the literature on it is huge. For some reason, the German analog of cliff is Klippe, and the problem of –f(f) ~ -(p)p has never been resolved. A mountain of research has not given birth even to the smallest viable mouse. At cliff and Klippe, dictionaries say only “origin unknown (uncertain).” Some scholars trace both nouns to the substrate: allegedly, the ancient Germanic inhabitants of Europe borrowed this word, along with many others denoting the features of the terrain new to them, from the native speakers of the area.

Since that language is lost, there is nothing to say about it. Braune believed that the words are Germanic and designate a huge piece of broken rock (compare clapboard and clappers, above, which Braune did not cite). If Braune guessed well, the difference between final p and f is as insignificant as the difference between initial k and g in kol ~ gol. I am not ready to take sides here, but have to say two things. First, a few seemingly inscrutable etymological riddles sometimes have embarrassingly easy solutions. Second, it does no one any good to ignore existing conjectures, even if they run counter to conventional wisdom, for, as history shows, a good deal of wisdom turns out to be folly.

Featured image credit: Photo © Richard Knights (cc-by-sa/2.0)

The post From rabbits to gonorrhea: “clap” and its kin appeared first on OUPblog.

What America’s history of mass migration can teach us about attitudes to immigrants

International migration is one of the most pervasive social phenomena of our times. According to recent UN estimates, as of 2017, there were almost 260 million migrants around the world. In the last five decades, the number of foreign born individuals living in the United States has increased more than five-fold, moving from 9 million in 1970 to 50 million in 2017. Not surprisingly, these trends have sparked a heated political debate. Both in Europe and in the US, proposals to introduce or tighten immigration restrictions are becoming increasingly common, and support for populist, right wing parties has been rising steadily.

Two main hypotheses have been proposed to explain anti-immigrant sentiments. The first is economic in nature: the negative effect of immigration on natives’ employment and wages may be the key determinant of political discontent in receiving countries. Although this idea is compelling, and consistent with some studies, evidence suggests that immigrants have a negligible, or even positive, impact on natives’ earnings. The second hypothesis is that backlash is triggered by cultural differences between immigrants and natives. Both today and in the past, politicians highlight the possibility that immigrants’ cultural diversity might represent an obstacle to social cohesion and a menace to the values of hosting communities.

Studying in a unified framework the political and the economic effects of immigration offers an interesting look on how immigration affects communities. It also has one crucial advantage: if one were to observe that immigrants bring economic prosperity without harming any group of native workers, but that they nonetheless trigger political backlash, this would speak in favor of the cultural hypothesis. Between 1850 and 1920, during the Age of Mass Migration, more than 30 million Europeans immigrated to the United States, and the share of foreign born in the US population was even higher than today. Such massive migration, however, was interrupted by two major shocks – World War I and the Immigration Acts (1921 and 1924) – that induced large variation not only in the number but also in the composition of immigrants moving to US in this period.

But in US cities between 1910 and 1930, it appears immigrants raised both employment and occupational mobility among natives. Even native workers employed in occupations heavily exposed to immigrants’ competition, such as manufacturing laborers, did not experience any job or wage losses. These positive economic effects were made possible by two, mutually reinforcing mechanisms. First, firms expanded and increased their investment to take advantage of the supply of cheap, unskilled labor provided by the immigrants. Second, the complementarity between the skills of immigrants and those of natives allowed the latter to get better jobs.

In spite of the positive impact of immigration on native workers, immigrants certainly did cause strong political backlash. First, members of the House representing cities that received more immigrants between 1910 and 1920 were significantly more likely to vote in favor of the 1924 National Origins Act – the bill that eventually shut down European immigration, and regulated the American immigration policy until 1965. It appears that a 5 percentage points increase in immigration was associated with a 10 percentage points higher probability of voting in favor of the National Origins Act. Second, cities cut public goods provision and taxes in response to immigrant arrivals. The reduction in tax revenues was entirely driven by declining tax rates, while the fall in public spending was concentrated on schools and hospitals – two categories of spending where members of the majority group are especially likely to oppose redistribution towards minority groups.

Why did such backlash emerge even if immigrants brought economic prosperity to US cities? It seems natives’ political reactions were increasing in the cultural distance between immigrants and natives, suggesting that backlash had, at least in part, non-economic foundations. The use of religion, in particular, is motivated by the historical evidence that, at that time, nativism often resulted in anti-Semitism and anti-Catholicism. While immigrants from Protestant and non-Protestant countries had similar effects on natives’ employment, they triggered very different political reactions. Only Catholic and Jewish, but not Protestant, immigrants induced cities to limit redistribution, favored the election of more conservative legislators, and increased support for the 1924 National Origins Act.

While such results may be specific to the conditions prevailing in US cities in the early twentieth century they indicate that, when cultural differences between immigrants and natives are large, opposition to immigration can arise even if immigrants are on average economically beneficial and do not create economic losers among natives. Thinking about the current political debate, it’s likely policies aimed at increasing the cultural assimilation of immigrants and at reducing the (actual or perceived) distance between immigrants and natives might be at least as important as those designed to address the economic effects of immigration.

The post What America’s history of mass migration can teach us about attitudes to immigrants appeared first on OUPblog.

July 9, 2019

The worrying future of trade in Africa

Africa is on the cusp of creating the African Continental Free Trade Area. This will be the first step on a long journey towards creating a single continental market with a customs union and free movement of people and investment – similar to the European Union.

The agreement, brokered by the African Union, was established at the Kigali Summit. To date, 52 countries have signed the agreement; only Benin, Eritrea and Nigeria have yet to sign it. The free trade area comes into force once 22 member states have ratified the document. On April 2, 2019, Gambia became the 22nd country to approve the agreement.

The first phase begins in June 2019. In terms of market access offers, the parties have already agreed to liberalise 97 percent of tariff lines, accounting for at least 90 percent of intra-African trade, with a five-year timeline for liberalisation (ten years for the least developed African countries).

Many studies conducted thus far on the expected effects of the agreement have been positive. The United Nations Economic Commission for Africa projects that the agreement will increase intra-Africa trade by over 52 percent. According to estimates by the African Development Bank, the effect of the removal of tariffs on intra-African trade will be a 0.1 percent increase in net real income, amounting to gains of $2.8 billion. In addition to the removal of tariffs, the removal of nontariff barriers on goods and services may result in a 1.25 percent increase in net real income, or a gain of $37 billion.

Much of the potential of the free trade agreement rests on the assumption that this agenda will be comprehensively implemented. Yet there is nothing in the history of trade commitments in Africa to suggest that this is likely. The trade agreement will follow the existing model of regional integration in Africa and may therefore face in even greater measure some of the implementation and coordination challenges that have obstructed regional trade. The East African Community, the most successful region in recent years, has encountered several obstacles, such as instability in the application of tariff and trade rules and trade disputes between countries. Following these disputes, some member states have ignored the rulings of the East African Community Secretariat.

This raises the question of whether the African Union and institutions created to administer the African Continental Free Trade Area will have enough disciplinary power to make countries comply. It’s unlikely.

Other matters of coordination have not been properly considered, such as aligning the trade agreement with industrial policy in the form of providing a continental framework to avoid predatory behaviour at the national level, which is one of the causes of dispute among countries of East African community. There is also the difficulty of aligning the new trade agreement with other commitments. For example recently launched post-Cotonou trade negotiation, the latest incarnation of the trade relations between the European Union and the African, Caribbean and Pacific countries, may not integrate well with the African Continental Free Trade Area. Given that under the current Cotonou Agreement, African regions negotiate separately with the EU, an approach that could undermine the African Continental Free Trade Area agreement, the African Union is insisting on a continent-continent approach where Africa negotiates as a single unit. However, such an approach would involve North African countries that have hitherto not been part of the EU-Africa trade history (which they view as neo-colonial) and are not keen on joining the trade agreement.

For the African Continental Free Trade Area to work, the African Union will have to deal with implementation and coordination challenges from the very beginning.

Featured Image Credit: ‘Shipping Containers’ by chuttersnap. CCO public domain via Unsplash.

The post The worrying future of trade in Africa appeared first on OUPblog.

July 8, 2019

Why the law protects liars, cheats, and thieves in personal relationships

Deception pervades intimacy. One reason is that deceivers stand to gain so much. A married man might falsely present himself as single so he can lure someone new into a sexual relationship. A girlfriend might deceive her boyfriend into thinking that she has been faithful so he will not leave her. A son might deceive his parents so they do not realize that he is using the money they send for tuition to fund his gambling addiction. A non-citizen might dupe a citizen into marriage in order to acquire the legal right to live and work in the United States. A stay-at-home wife without her own income might lie to her husband about household expenses as a way of accumulating cash she can spend without his approval.

Another reason deception is common in intimacy is that many would-be deceivers are confident that their deceit will not be discovered. Indeed, uncovering an intimate’s deception can be extremely difficult, even for a person of average or above-average shrewdness and sophistication. First, we have much less ability to spot deception than we like to believe and detecting deception from someone close to us may be especially challenging. Second, strong social norms urge us to trust our intimates rather than investigate them. Third, even if we would like to disregard those norms, it is often difficult to mount an investigation without the detective work jeopardizing the relationship because the investigated person finds out about the sleuthing. There are practical obstacles to investigating without the subject’s knowledge. Your intimate may discover that you have been following him, interrogating his friends, or searching his garbage. Moreover, there are legal obstacles to investigating without first obtaining permission. Perusing someone’s tax returns, credit reports, or email without authorization is against the law—and for good reason.

The consequences of intimate deception can be life-changing. They include financial losses, violations of sexual autonomy and bodily integrity, lost time, missed opportunities, and emotional distress and devastation.

So how does the law respond to duplicity within dating, sex, marriage, and family life? People often assume that intimate deception operates in a completely private realm where courts and legislatures play no role. In fact, deception within intimacy is a perennial issue for the law because it is such a prevalent part of life. An enormous body of law governs intimate deception, but this legal regulation has been overlooked and under-examined.

An enormous body of law governs intimate deception, but this legal regulation has been overlooked and under-examined.

The law tends to protect intimate deceivers and to deny help to the people they deceived. Courts routinely tell deceived intimates that even if they can prove all the elements of a tort claim for misrepresentation, battery, intentional infliction of emotional distress, or the like, they cannot access those remedies because they were duped by an intimate rather than a stranger.

For example, Paula Bonhomme reported that she connected with a man on an internet chatroom, who proceeded to spend almost two years emotionally abusing her while extracting more than ten thousand dollars in gifts. Paula eventually learned that she had been exchanging phone calls, messages, and packages with someone who did not exist. She contended that a woman named Janna St. James had invented a fake persona to lure her into endless interactions and manipulate her financially and emotionally. Paula sued Janna for fraudulent misrepresentation, and her allegations appeared to satisfy all the elements of that tort. Nonetheless, the Illinois Supreme Court held that Paula’s suit could not proceed, on the (strained) theory that Paula was suing an intimate.

We need a transformation in the law governing intimate deception. When a deceived intimate seeks redress in court, judges should begin with a rebuttable presumption that she will have access to the same remedies that the legal system makes available for equivalent deception outside of intimacy. If a person could sue a deceptive stranger for stealing her money, causing her physical injury, or inflicting emotional harm, she should be able to present the same evidence and bring the same claims when her deceiver is an intimate.

The law can also do a better job of regulating intimate deception before any lawsuit is brought. Avoiding injury is better than having a right to redress after being harmed and many people will not sue, even if their chances of prevailing in court improve.

Intimate deception generally causes less damage if it is unmasked sooner rather than later. So legislatures should look for opportunities to help people discover whether an intimate is deceiving them when that can be accomplished without jeopardizing privacy, liberty, or security. For example, states might cooperate to create a database that consolidates public records on marriages, divorces, and bigamy convictions. Such a database would make it easier to discover whether a lover—or fiancé—is as unmarried as he claims to be.

Similarly, intimate deception will cause less injury if the law limits the damage that a duplicitous person can inflict without his intimate’s knowledge. Too often, the law does nothing to stop a married person from taking joint property for his own purposes or from secretly accumulating debts that his spouse will be obligated to pay. States should make it harder for a married person to expropriate joint assets without his spouse’s consent where such safeguards can be imposed without unduly burdening everyday transactions.

In short, the law should devote more attention to helping people deceived within intimate relationships and be less concerned about protecting intimate deceivers. Entering an intimate relationship should not mean losing legal protection from deceit.

Featured image credit: Happy Singles Awareness Day. Photo by Kelly Sikkema. CC0 via Unsplash .

The post Why the law protects liars, cheats, and thieves in personal relationships appeared first on OUPblog.

July 7, 2019

The not-so ironic evolution of the term “politically correct”

This month, we look at the term “politically correct.”

The phrase has a long history in the twentieth century to describe those who hold to some ideological orthodoxy. The term shows up, for example, in the January 1930 issue of The Communist, the newspaper published by the Communist Party of the U.S.A. The newspaper reports on a resolution by Canadian students studying in Moscow who criticized the “opportunistic line” of one American socialist and endorsed the views of the Tenth Party Plenum as giving “a politically correct perspective.” What’s more, the students’ resolution noted that “an enlightenment campaign” would be required to overcome “erroneous conceptions.” “Politically correct” was being used unironically to denote conformity to official Party doctrine.

However, other leftist writings from the 1930s seemed to use the term mockingly. West Coast communist leader Harrison George, writing in 1932 about the United Farmers’ League, critiqued the party for insisting that “all things be revamped to conform with the program for European peasants.” That program, he argued, would not be understood by American farmers though “Of course, it is politically ‘correct’ to the last letter.” George’s quotes around correct suggest his view of a gulf between political doctrine and practical solutions.

By 1934, the New York Times had extended the phrase to refer to Nazi orthodoxy. In an article titled “Personal Liberty Vanishes in Reich,” Frederick T. Birchall wrote that in Germany “All journalists must have a permit to function and such permits are granted only to pure ‘Aryans’ whose opinions are politically correct. Even after that they must watch their step.” In Birchall’s report, the phrase describes ideological line-toeing required under Hilter. A 1940 Washington Post report similarly condemns Josef Stalin for replacing seasoned older officers with “politically correct zealots.”

In the wave of social change that emerged in the post-World War II era, the mix of ironic and non-ironic usage remained in play linguistically among those on the left. “Politically correct” could be used to indicate a connection of one’s progressive political views to actions in everyday life. But it could also be used to refer to leftist views too ideologically rigid to be useful, a usage influenced perhaps by the Chinese Cultural Revolution of the 1960s and the popularity of the notion of “correctness” in the writings of Mao Zedong.

Over time, those unsympathetic to social change adopted “politically correct” as a derisive term for progressive viewpoints generally and especially for changes in language that reflected and signaled those viewpoints. An early example of the phrase being used this way was from writer and critic Terry Teachout, who wrote in the National Review in 1986 that “‘The Cosby Show’ is, to use a hideously canting phrase, ‘politically correct.’” “Politically correct” was still enough of a novel idea to the general public to be singled out as “hideously canting” and placed in quotation marks.

Soon, however, the ironic quotes were gone. During the 1980s, conservative commentators began to refer to multicultural curriculum initiatives and attempts to foster inclusive language as “political correctness.”

Soon, however, the ironic quotes were gone. During the 1980s, conservative commentators began to refer to multicultural curriculum initiatives and attempts to foster inclusive language as “political correctness.” The adjective phrase had become a noun. In 1992, President George H. W. Bush speaking to the graduating class at the University of Michigan, would claim that that such initiatives were an “assault” on free speech.

The notion of “political correctness” has ignited controversy across the land. And although the movement arises from the laudable desire to sweep away the debris of racism, sexism and hatred, it replaces old prejudices with new ones.

It declares certain topics off-limits, certain expressions off-limits, even certain gestures off-limits. What began as a cause for civility has soured into a cause of conflict and even censorship.

The following year, the television show “Politically Incorrect” debuted, associating the idea of in-your-face truth-telling. The show lasted nine years before being cancelled over comments by host Bill Maher, whose criticism of US military policy was construed as disrespecting military personnel. A high—or low—point in the shift of connotation of “politically correct” from ironic self-mocking to partisan satire was the publication of James Finn Garner’s Politically Correct Bedtime Stories in 1994. A New York Times bestseller for over a year, the book referred to Cinderella as a “young wommon,” the seven dwarfs as “bearded, vertically challenged men,” and the big, bad wolf as “a carnivorous, imperialistic oppressor.”

The notions of political correctness and incorrectness continued to evolve in the direction of partisan attack. In the 2016 election, one candidate warned of a conspiracy “to give away American values and principles for the sake of political correctness,” while another asserted that “Political correctness is killing people” by making profiling difficult. The eventual Republican candidate, when challenged about comments he had made about women, dismissed the issue by saying, “The big problem this country has is being politically correct.”

The use of “politically correct” and “political correctness” no longer has any irony or even sarcasm to it, and George H. W. Bush’s nod to civility is gone as well. Instead, dismissing an issue or challenge or complaint as being “politically correct” has become catchall for those who want to avoid discussing racism, sexism, and discrimination and who are willing to rebrand offensiveness as frankness.

This July might be a good time to declare our independence from this particular expression.

Featured image: “Politician giving a speech” by Liberal Democrats. CC BY-ND 2.0 via Flickr.

The post The not-so ironic evolution of the term “politically correct” appeared first on OUPblog.

July 6, 2019

G.E. Moore – his life and work – Philosopher of the Month

G.E. Moore (1873-1958) was a British philosopher, who alongside Bertrand Russell and Ludwig Wittgenstein at Trinity College, Cambridge, was a key protagonist in the formation of the analytic tradition during the twentieth century.

One of seven children, Moore grew up in South London and was educated initially by his parents. He was taught French by his mother, and reading, writing, and music by his father. Aged eight he enrolled at Dulwich College studying a mix of classic and romance languages, alongside mathematics, and at eighteen commenced study at Cambridge University reading classics. It was at Cambridge that Moore met Bertrand Russell (two years his senior) and Philosophy Fellow of Trinity College, J.M.E. McTaggart who together, encouraged Moore to study philosophy. Moore graduated in 1896. A fellowship kept him at Cambridge for the next six years.

During his time at Cambridge, Moore formed a number of long-lasting friendships with figures of the soon to be Bloomsbury Group. These friendships allowed Moore a channel of indirect influence on twentieth-century culture, leading in part to the encouragement of his reputation of having a Socratic personality; his written work did not necessarily capture his full thought. Moore would remain at Cambridge almost without leave – but for a short spell away and later a handful of years spent in the US – becoming first lecturer in 1911, then professor in 1925 before retiring in 1939. During this time, Moore was elected a fellow of the British Academy in 1918, President of the Aristotelian Society from 1918 to 1919, and in 1921 became editor of the highly-influential journal Mind.

Moore’s work was not confined by field or by niche, and it is often remarked that Moore was as concerned with puzzling out philosophical ideas, developing arguments, or exploring challenges, as he was devolving a framework as in the tradition of systematic philosophers. His influence extends deeply and widely, but he is perhaps best known for his opposition to the prevailing British idealism, his criticism of ethical naturalism in his most well-known work Principia Ethica, his contributions to ethics, epistemology and metaphysics and Moore’s Paradox. Moore wrote a number of other books including: Ethics (1912), Philosophical Studies (1922), Some Main Problems of Philosophy (1953), and the posthumous collection Philosophical Papers (1959).

Leading the charge alongside Russell, Moore firmly rejected the then dominant philosophy of idealism (though he had initially been a follower under McTaggart). Instead of upholding the theory established by G. W. F. Hegel, that everything common-sense believes is realm, is mere appearance, Moore argued the opposite; that everything common-sense believes is real, is real. Two key papers expound upon this and deserve close attention: “A Defence of Common Sense” (1923) and “A Proof of an External World” (1939).

In 1903, Moore published Principia Ethica in which he laid out his criticism of ethical naturalism, arguing that it involves the naturalistic fallacy that goodness can be defined in naturalistic terms. He argued that goodness is in actuality indefinable, unanalysable, and non-natural property. Principa Ethica was hugely influential, sending ripples through non-philosophical circles – including the literary world of the Bloomsbury Group where members including Maynard Keynes, Lytton Strachey, and Leonard Woolf had come into contact with him as fellow members of the Cambridge University secret debating society the Cambridge Apostles – as well within philosophy. The 1903 work has been frequently cited as one of the most influential works of its type and time, though in recent times this claim is somewhat down-played.

“It is raining but I do not believe it is raining,” is the sentence often used to express Moore’s Paradox. It is a fitting example of his love for puzzling out an idea. In the sentence it seems impossible for anyone to consistently assert the sentence, though there doesn’t appear to be a logical contradiction. The paradox illustrates that though the sentence is apparently absurd, it can nevertheless be true, consistent, and not logically a contradiction. The paradox was to have a strong influence on Wittgenstein (who has been attributed with naming it thus), though Moore himself never developed the idea more fully.

Perhaps then this approach to the paradox gives us a clue to Moore’s life more broadly and offers a lens on his legacy. A key figure among British philosophers in the early twentieth century, he is arguably the lesser known name, by degree. Yet his work was of such influence and significance that its effects were felt so widely and fully.

Moore married Dorothy Ely in 1916 and together had two sons: the poet Nicholas Moore, and composer Timothy Moore. G.E. Moore died in Cambridge, 1958.

Featured image credit: “Bicycle and a brick wall” by Clem Onojeghuo via Unsplash.

The post G.E. Moore – his life and work – Philosopher of the Month appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers