Oxford University Press's Blog, page 187

June 7, 2019

250 Years of Oxford weather

Talking about the weather is a national obsession. Thomas Hornsby talked about the weather, or at least wrote about it, in Oxford back in the mid-eighteenth century. His surviving diaries from 1767 mark the commencement of the longest continuous single-site weather records in the British Isles, and one of the longest anywhere in the world.

Hornsby was a Savilian professor of astronomy at Oxford University. At the time, the university’s astronomy facilities were very limited (a couple of telescopes on the roof above the professor’s lodgings in New College Lane). Hornsby, described by contemporaries as “an energetic young Fellow of Corpus Christi College,” petitioned the Radcliffe Trust in 1768 for funds to build and equip a new astronomical observatory. He must have been persuasive, too, for the Radcliffe trustees agreed quickly, and funded the construction of Oxford’s Radcliffe Observatory. The final bill came to £31,661 (between £3M and £4M in 2019 values). The instruments themselves, the finest in the world in their day, cost almost as much as the building. By comparison, Hornsby’s salary, as the Radcliffe librarian, was £150 per annum. The observatory was completed in 1799.

Thomas Hornsby’s weather diary for January 1767; barometer readings are in inches of mercury, outside temperature in degrees Fahrenheit. This was a bitterly cold month in Oxford, the temperature remaining mostly below freezing.

Thomas Hornsby’s weather diary for January 1767; barometer readings are in inches of mercury, outside temperature in degrees Fahrenheit. This was a bitterly cold month in Oxford, the temperature remaining mostly below freezing.For once, the Law of Unintended Consequences worked in science’s favour. Air temperatures were at first measured solely to correct star positions for atmospheric refraction, but over time the meteorological observations became increasingly important in their own right. Today they are unique and priceless records documenting changes in climate since Georgian times, and a significant contribution to Britain’s meteorological history.

After a few false starts following Hornsby’s death in 1810, the observatory has maintained an unbroken daily record of atmospheric temperature and barometric pressure since 14 November 1813. Daily rainfall records began in January 1827 (a monthly rainfall series began with Hornsby in 1767), and daily sunshine duration in February 1880 – the longest continuous sunshine record anywhere in the world. After the astronomical observatory moved to the clearer skies of South Africa in 1935, responsibility for the meteorological observations passed to the university’s School of Geography (now the School of Geography and the Environment). Today the observers are postgraduate students, who make the morning meteorological observation at 9 a.m. Greenwich Mean Time every day of the year without fail – including Christmas Day.

The morning readings being taken at the Radcliffe, August 2018. (Copyright Stephen Burt)

The morning readings being taken at the Radcliffe, August 2018. (Copyright Stephen Burt)Almost all of the meteorological instruments have been replaced over the years, thermometers many times: but the duty observer still reads the the Newman Standard barometer, installed in the Radcliffe Observatory in June 1838. The same instrument has been in use for over 180 years.

The records could well have been lost altogether had it not been for the dedication of staff members like James Balk, who joined the observatory at the age of 14 in 1903. He took on the Herculean task of assembling, cataloguing and carefully analysing those precious early records, mostly in his spare time. Without his interest and commitment, they might have been discarded when the observatory staff moved to Pretoria. Balk remained in charge of the meteorological observations in Oxford after everyone else moved, only retiring in 1954 after 51 years of service.

What do Oxford’s long weather records tell us of climate change? Oxford has warmed by 1.7 degrees Celsius in 200 years, and all of the ‘Top 5’ warmest years have occurred since and including 2006. In contrast, the most recent ‘Top 5’ coldest year was 140 years ago in 1879. Oxford is also getting sunnier, as well as warmer. Sunshine amounts have increased since the 1960s, particularly in winter, the increase being largely attributed to the reduction in winter fogs brought about by smoke reduction legislation. Fogs are now only one-third as frequent as they were in the 1920s and 1930s.

What will the next 250 years of weather records from Oxford reveal? Before the end of this century Oxford could be warmer than Rome is today. Whatever would Thomas Hornsby make of that?

Featured image credit: “Clouds” by Jesse Gardner. Public domain via Unsplash.

The post 250 Years of Oxford weather appeared first on OUPblog.

June 6, 2019

Why even Mormons are pushing for LGBT inclusion

A decade ago, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints was licking its wounds after its disastrous involvement in California’s Proposition 8. The church had won a coveted victory—Proposition 8 passed, effectively outlawing same-sex marriage in the state—but lost the war of public opinion. When Americans found out that Mormons had funded an estimated 50%–70% of the $40 million raised to support Prop 8, despite comprising less than 2 percent of California’s population, there was a public outcry. “Mormon” became equivalent in the public eye to “homophobic.”

Fast forward to this year’s commencement season, when a Brigham Young University graduate gave a speech that was widely heralded for its courage and honesty. Political science valedictorian Matty Easton challenged decades of the church’s teachings that homosexuality was a sin someone chose, rather than an orientation that was part of their makeup, as he publicly came out as gay.

“I’m coming to terms not with who I thought I should be, but who the Lord has made me be,” he said. “As such I stand before my family, friends and graduating class today to say that I am proud to be a gay son of God.”

What changed? What has happened in Mormonism in the last decade to make it possible for a gay student to proudly proclaim that his homosexual orientation is divinely inspired, even if the church-owned university he attended still won’t let him so much as hold hands with a man?

Not the leadership. The LDS Church’s hierarchy is essentially a gerontocracy, with the top fifteen leaders—all men—generally appointed in their sixties and holding their posts until death. Instead, society changed—rapidly—while the church’s leadership has struggled to keep up. In 2007, according to Pew research, Americans were exactly divided on whether homosexuality should be accepted or discouraged by society. In other words, Mormons were far from alone in supporting measures like Proposition 8 in 2008. But by 2014 when Pew repeated its study, 62% of Americans had tilted toward support, and it has climbed every year since.

That change is occurring among Latter-day Saints as well. Support for homosexuality and same-sex marriage is markedly lower among Mormons than in the general population, but there’s a clear generational shift at work. For example, only 38% of Boomer/Silent Mormons (those ages 52 and older in 2016) agreed that homosexuality should be accepted by society, but 60% of Mormons in the 18–26 age group said it should. Younger Mormons are more socially conservative than other Millennials their age, but not as conservative as their Mormon parents and grandparents.

They’re also more sexually diverse. Only 2.6% of older Mormons who remain affiliated with the church report being anything other than heterosexual, or about one in thirty-eight. In contrast, roughly one in ten Millennial Mormons is nonheterosexual, mirroring patterns in the general population. For young adult Saints, bisexuality is the most common minority orientation (7%), followed by homosexuality (2%) and “other” (1%).

So when Mormon leaders make statements about homosexuality today, they do so in a climate that has shifted dramatically in a short period of time. Many Mormons feel differently about homosexuality than they did a decade ago, and more younger ones are embracing a nontraditional sexual identity—with pride.

What’s more, the church’s stance on LGBT issues has proven a “wedge issue” in whether young people—even those who are not LGBT themselves—want to stay Mormon. The third-most-cited reason that Millennial former Mormons gave for leaving the church was the institution’s position on LGBT issues. For older former members, it did not even rank in the top ten.

The church is now attempting to navigate a tricky position in which it continues to hold the line on same-sex marriage (still teaching that it is a sin, but no longer investing in political campaigns against it or forbidding children of same-sex couples from getting baptized) while cracking the door for greater acceptance of LGBT members. And younger Mormons are often leading the way.

Featured image: Untitled by Robert V. Ruggiero. Public Domain via Unsplash.

The post Why even Mormons are pushing for LGBT inclusion appeared first on OUPblog.

June 5, 2019

Etymology gleanings for May 2019: Part 2

Spelling bee and the shame of the sun: some thoughts on animated spellcheckers

Once again, I have stumbled upon an upbeat report of the latest spelling bee, and shout in disgust: “J’accuse!” I accuse the establishment of promoting a harmful sport. Millions of Americans graduate from high school without having heard what the subjunctive mood or an impersonal sentence means. They have never been told that some languages have cases (the genitive, the dative, and so on). We implore college students to avoid the apostrophe in the possessive pronoun its, and they ask what possessive pronoun means. Those are our sons and daughters who refuse to read English and American classics because their own vocabularies are reduced to a few thousand most common words and because long books, unlike cartoons, are “boring.”

Against this background, some children waste their lives learning the spelling of Bewusstseinlage (it is a German noun meaning approximately “the state of consciousness”). For some reason, Bewusstseinlage has made it into English dictionaries, along with the more respectable German compounds Schadenfreude, Zeitgeist, and Weltschmerz. And rejoice: some spellers know this monster, without, of course, knowing German. (German has a lot of grammar, and grammar, we have been told, is not “fun.”) Last year, a young ambitious teenager “was dinged out” by marasmus: she did not remember which letter follows the first m. To be sure, if she knows everything else, this is indeed a tragedy. “I knew the word. I knew the word. I had heard it before, I knew the definition of it, but I forgot that schwa in that second,” she said with the eloquence of despair. But this year, eight children (seven of them 13, one 14-years-old) spelled all the words correctly. Weep and wonder: Wundtian, coelogyne, yertchuk, huiscoyol, bremsstrahlung, and ferraiolone.

The only bees we should treasure. Image credit: “Honey Bee Hive” by chrisad85. Pixabay License via Pixabay.

The only bees we should treasure. Image credit: “Honey Bee Hive” by chrisad85. Pixabay License via Pixabay.The Shame of the Sun is an essay written by Martin Eden, the hero of Jack London’s best novel, which none of those honey-seekers have read. See a picture of the eclipse in the header.

On char and chore

We remember char– only from charwoman; yet chores is a familiar word. The suggestions of our correspondent (in a letter) are perfectly correct. Old Engl. cirran meant “to turn away”; the cognate noun sounded as cerr ~ cyrr. German kehren “to turn” is, most probably, related. Although The Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology states that the variation char ~ chore is unexplained, there is no mystery here. I am borrowing my examples from the excellent book Laut und Leben (literally, “Sound and Life”) by Horn-Lehnert. Similar examples occur elsewhere, but those sources are less “popular.” In the not too remote past, long a (as in Modern Engl. spa) tended to become long o (as in Modern Engl. or) in the pronunciation of the lower classes: bawth “bath,” awfter “after,” and the like. The southern American long a, pronounced as aw, (sometimes followed by schwa) and ridiculed as drawl, is of that origin, and of course the pronunciation Chicawgo, though “non-standard” and not southern, is well-known. The spellings Chorles, Mork, yord, and yorn for Charles, Mark, yard, and yarn were recorded at the beginning of the seventeenth century. Char- ~ chor- also belong here.

Returning to the sn- ~ sl- morass: snuff, snub, snob; snide, snitty, and their likes

A mobile creature with s-mobile in the name. Image credit: Western Diamondback by skeeze. Pixabay License via Pixabay.

A mobile creature with s-mobile in the name. Image credit: Western Diamondback by skeeze. Pixabay License via Pixabay.I have received several letters about sn– and sl– words (see the posts for March 13 and March 20, 2019). In one of those posts, sniff, snuff, snout, etc. and their possible connection with nose were discussed. The trouble is that initial s- often appears before other consonants in words that are certainly related. The anthologized examples are Engl. steer “a castrated (or young) bull” versus Latin taurus “bull” and Engl. snake versus Sanskrit nāga (the same meaning), but such words are numerous. The origin of this enigmatic, fugitive s, known as s-mobile (movable s), remains a puzzle; see a book on it by Mark Southern. That is why, when we deal with sniff, snuff, and the rest, we cannot be sure whether any connection exists between them and nose; neb, nib, nibble, and German Schnabel “beak” also spring to mind.

From sniff, nib, and their likes, we may return to snout ~ snoot ~ snotty. About a century ago, Samuel Kroesch, my “quondam” colleague at the University of Minnesota, discussed some such words in detail and discerned the development from “blow one’s nose” to “deceive” (a common trend in many languages), with the original sense being “to cut, “ that is, “to snub.” According to this reconstruction, a snotty person must have been a deceiver. (In my post, I cited the Old Germanic look-alikes meaning “smart, wise”; were mainly those people considered wise who could outsmart or demean others?) This returns us to the perennial question about the origin of snob (see the post of May 14, 2008). I can see two possible approaches here. Either snob arose as a sn-word with a derogatory meaning and was later applied to cobblers, who, like tailors, for centuries, were ridiculed and denigrated. Or a snob was a snubber in the direct sense of the word; that is, a cutter of shoe soles.

Snotty, snitty snobs have always existed, but the word surfaced in print only in the 1780s and was made popular by Thackeray. Image credit: “Book of Snobs XVIII page 69” by W. M. Thackeray himself, for the first edition of The Book of Snobs. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Snotty, snitty snobs have always existed, but the word surfaced in print only in the 1780s and was made popular by Thackeray. Image credit: “Book of Snobs XVIII page 69” by W. M. Thackeray himself, for the first edition of The Book of Snobs. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.My ideas about the origin of snitty “ill-tempered; sly” (another question from a correspondent) are equally vague. I looked up snitty and the adjective snide in several dictionaries and found that their origin is unknown. Nor does my etymological database contain a single reference to them. Snitty turned up in a printed book only in 1978 (the earliest citation in the OED); snide surfaced in the 1850s. At first sight, their proximity to Dutch snijden and German schneiden “to cut” seems obvious, but is it real? And how did they arise in English? They could hardly be borrowed directly from Low German so late. Conversely, if a snitty person is a twin of a snotty one, do we witness a case of arbitrary vowel alternation, so common in slang (this alternation is sometimes called false ablaut)?

Snide is equally opaque. Although this adjective may be applied to a mean, sarcastic person, in today’s English, only remarks and comments are usually called snide. And here I may suggest a connection that does not seem to have been noticed. German has the adjective schnöde “contemptible; mean”; its Dutch congener is snood. Somewhere, and not too long ago, there must have been groups of people who used such words with their direct meanings: “cut close to the surface, shorn; shaved.” Those were probably itinerant workers, handymen traveling from place to place and from land to land with their implements (axes, adzes, hatchets, planes) and developing some sort of technical lingua franca. Their professional words were mutually understandable across dialect and language borders, but the vowels and consonants varied in a rather capricious way. Occasionally some elements of their vocabulary became known to the outside world, continued as slang, and finally merged with the more “respectable” words (compare the history of slang: the post for September 28, 2016).

Admire the snood and think of the origin of the word. “Snood Met” by Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. CC 1.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Admire the snood and think of the origin of the word. “Snood Met” by Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. CC 1.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Snide and snitty seem to be Americanisms. Are they loans from Dutch speakers? Surely, snitty existed before 1978, and its closeness to schnöde looks convincing. Snide may be a member of the same family. Next, surprisingly, comes Engl. snood “hairband; a fillet worn traditionally in Scotland by unmarried women.” The function of the snood was to keep the hair close to the skin of the head. Snide, snitty, and snood, though an ill-assroted family, look like belonging together. Yet each has its own history whose details may be lost for all times.

Featured image: “Eclipse Twilight Moon” by ipicgr. Pixabay License via Pixabay.

The post Etymology gleanings for May 2019: Part 2 appeared first on OUPblog.

June 4, 2019

What early modern theater tells us about child sexual abuse

The sexual abuse of children endemic in the Roman Catholic Church is once again in the news, with Pope Francis mandating reporting within the Church. The Catholic Church is not alone; investigative journalists have revealed a pattern of sexual misconduct among Southern Baptist pastors and deacons over a twenty-year period, involving more than seven hundred victims. Secular institutions, including USA Gymnastics and the Pennsylvania State University football program, have also enabled and covered up child sexual abuse.

What can a longer historical view tell us about these patterns of abuse?

For one thing, we can recognize that evidence of child abuse has long hidden in plain sight. Records of the grammar schools, choir schools, and commercial theater companies that trained and employed boys in early modern England are full of casual references to beating. These references are sometimes euphemisms for sex acts, as when Richard Mulcaster was said to jest that his rod “Lady B[i]rch” would enter into matrimony with a boy’s “buttock[s].” Explicit accusations of sexual abuse are rare, but we know that the schoolmaster and playwright Nicholas Udall was convicted of “com[mitting] buggery” with a pupil in 1541, and there is little reason to think that this was a unique instance. Anti-theatrical writer William Prynne claimed that child abuse was routine in the commercial theater: “Players and Play-haunters in their secret conclaves play the Sodomites . . . desperately enamored with Players[’] Boy[s] thus clad in wom[en’s] apparell, so fa[r] as to sol[icit] them by words, by Letters, even actually to abuse them.”

But accusations like Prynne’s cannot be taken at face value. Prynne is a Protestant extremist writing biased, slanderous invective. He is also grouping what we now call child abuse within the amorphous category of sodomy. We cannot know whether accusations of this sort allude to sexual abuse, queer sex acts, or undefined paranoia about sexuality and gender. We cannot even know what exactly Prynne means by “boys”: child actors could be as young as six or seven, but the seventeenth-century children’s companies sometimes retained actors into their twenties.

The challenge for scholars is to contextualize such evidence without ignoring historical realities of abuse. Alan Stewart threads this needle in his book Close Readers, arguing that outcries against schoolroom flogging derive not only from concerns about violence and sex acts but from cultural anxieties about status and social mobility. At the same time, Stewart argues that “the shared secret of the dolorem infandum, the pain not to be spoken” is the consequence not only of a few aberrant schoolmasters but of widespread practices of abuse enabled by the early modern educational system as a whole.

We can detect traces of dolorem infandum in Renaissance drama, including in songs that depict the sexual subjection of children. Songs by William Shakespeare, Ben Jonson, and other playwrights sexualize not only boys playing women but boys playing boys. They are not straightforward evidence of historical practices of abuse, but they do make plain that fantasies of sexual aggression were closely associated with the child singers of the early modern theater. In some cases, such as John Marston’s play What You Will, song becomes a means for children to denounce and excoriate their abusers. More often, children’s songs reference abuse without censure or critique, trading upon the erotic energy invested in virtuosic young vocalists.

It is now taboo to eroticize children in the explicit ways we see in Renaissance drama. As James Kincaid has shown, however, our idealization of childhood innocence has come with its own set of obsessions and desires. Kincaid’s book Child Loving traces these desires back to the Victorian period, arguing that “by attributing to the child the central features of desirability in our culture—purity, innocence, emptiness, Otherness—we have made absolutely essential figures who would enact this desire.” Kincaid’s subsequent book Erotic Innocence shows how fixations upon childhood purity and desirability play out in the sensationalism surrounding child molestation in contemporary American culture.

Accounts of child abuse tend to focus on individual abusers—Larry Nassar, Jerry Sandusky, Cardinal Theodore McCarrick. At the Catholic Church’s recent summit on sexual abuse, Pope Francis described abusive priests as “ravenous wolves” and “tools of Satan” who must be held individually accountable. The risk here is in ignoring the institutional and ideological conditions that make patterns of abuse possible. Scholars of literary and cultural history have begun to trace these patterns back in time, revealing long histories of obsession with child sexuality and institutional complicity in abuse. Further examination of this difficult topic is necessary, both in the present moment and in longer historical context.

Featured image credit: “Bacchanal with infant satyrs and putti” (c. 1633–78) by Giulio Carpioni. CCO 1.0 via The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The post What early modern theater tells us about child sexual abuse appeared first on OUPblog.

June 3, 2019

The effects of junk science on LGBTQ mental health

Studies and statistics can be interpreted in wildly different ways. It’s concerning how false and misleading uses of data collected about LGBTQ people affect our communities. In general, studies and resulting data about LGBTQ people and mental health are a positive step in moving toward culturally competent mental health care for all. For example, the Williams Institute at the UCLA School of Law studies LGBTQ people and laws affecting them. The organization also provides potential solutions to rectify the imbalances in social and economic systems.

LGBTQ people suffer from a proportionately higher level of mental health issues and suicides than straight people. There are also a lot of false claims about this complex issue, and this is a concern. For example, the Alliance for Therapeutic Choice and Scientific Integrity peddles the antiquated belief that queer and transgender identity are mental illnesses that require treatment. The misleadingly named organization is a new incarnation of the National Association for Research and Therapy for Homosexuality, which has a long history of peddling damaging reparative therapy along with other junk science. The organization’s misleading information supporting reparative therapy has been considered as actual evidence in the current debate about and drafting of state-by-state legislation to outlaw the use conversion therapy on minors. (Conversion therapy has been discredited by every reputable mainstream medical and psychiatric organization.) Further, the organization’s junk science has received unwarranted media attention, influencing public opinion and fanning the flames of anti-LGBTQ hatred and violence.

The game of battling studies and statistics is a sort of pushmi-pullyu situation. Like Doctor Dolittle’s fictional animal with two heads at opposing ends of its body, studies exist and statistics are extracted and used in various capacities both nefarious and righteous. For example, the Williams Institute’s statistics, such as a 2011 study on the prevalence of people who experience same-gender attraction, was twisted into anti-LGBTQ news by hate websites in a way that directly contradicted the legitimate study outcomes. The Christian Post claimed that the Williams Institute study was inflating the numbers of self-identified LGBTQ people.

There are dozens of online news sites spreading false information about LGBTQ people on a daily basis. Anti-LGBTQ propaganda organizations, including Focus on the Family, The American Family Association, the Family Research Institute, and LifeSite News, use their own dubious studies and statistics along with completely legitimate statistics and solid studies, but skew the information with their own anti-LGBTQ bias.

The American Psychiatric Association’s removed homosexuality from its classifiable mental illness list from its Diagnostic and Statistical Manual in 1973. However, anti-LGBTQ groups and organizations and their news organs still have at their core a belief in this discredited notion.

In reality, everyday acts of oppression and abuse contribute to trauma that negatively affects mental health in a disproportionate number of LGBTQ community members. But disinformation about the community, skewed reports, hate-filled pronouncements, and wrong-headed interpretations of studies about LGBTQ people are part of the all-too-commonplace discrimination and aggression that many people even don’t see. However, such lies, along with daily abuses and aggressions, acts of discrimination and oppression, take a huge toll; they are not just hurtful, annoying, or tiring – they are debilitating, and they negatively affect people’s mental health.

Members of the LGBTQ community are fighting for their very lives and wellbeing every day in a homo- and transphobic society. In the end, they are not just data points, statistics, or study subjects; they are living, breathing human beings. And they are strikingly resilient.

Featured image: “Two Hands Filled With Paint” by fotografierende. Public Domain via Unsplash.

The post The effects of junk science on LGBTQ mental health appeared first on OUPblog.

June 2, 2019

What is the Middle Voice?

We have probably all heard the terms “active voice” and “passive voice,” but did you know there is also a middle voice?

Grammarians use the term “voice” to refer to the relationship between the event described by a verb and the participants in the event. When a verb is in the active voice, the subject is performing the action described by the verb and the object of the verb is having the action performed on it. So, in a sentence like

The press published several excellent new studies on grammar.

The subject (“the press”) is doing the publishing, and the direct object (“several new studies of grammar”) is being published. The passive voice, the unfortunate bane of some writing teachers, is found in the sentence:

Several excellent new studies on grammar were published by the press.

where “new studies” is the subject and is having the action performed on it and the object of the preposition by is performing the action described by the verb. The metaphors “acting upon” and “being acted upon” are evident in the terms active voice and passive voice and extended to the idea of active and passives sentences (ones with active or passive voice verbs). And note that the by phrase can be omitted, leading to what is called the truncated passive where the noun performing the action (“the press”) is implied:

Several new studies on grammar were published.

Beyond the active and passive, English also has something known as the middle voice, sometimes more fancily called “the mediopassive.” The middle voice occurs when the subject of the sentence is the noun or noun phrase that is acted upon, but there are none of the trappings of the passive, like the auxiliary be-verb and the by-phrase. We find the middle voice in sentences like these:

Her novels sell well.

Some people photograph easily.

Novels are sold, not doing the selling; people are photographed, not operating a camera. But in these middle voice sentences, the focus is on the novels and people, and reference to agency is suppressed altogether. You can think of the middle voice as mid-way between the active and the passive—grammatically active but semantically passive. The middle voice is often accompanied by an adverb like well or easily, which refers to properties of the subjects (novels or people) or the situation that makes them good products or easily photographed.

The middle voice also includes sentences with a non-literal reflexive pronoun in the place of the adverb. An example would be “Her novels sell themselves,” which means that they are so easy to sell that no effort is needed. The sentence is a close paraphrase of “Her novels sell well,” but the similarity breaks down if the two sentences are negated: “Her novels don’t sell well” is not the quite the same as “Her novels don’t sell themselves.”

Verbs of causation overlap with middle verbs, and sometimes are even referred to as a kind of medio-passive. These are verbs like open, close, melt, freeze, sink, break, among others. Open, for example, can occur in the active voice, as in “Jill opened the window.” But it can also occur in the passive (“The window was opened by Jill”) or in the middle voice (The window opened”), where the implication of agency is suppressed.

The middle voice has antecedents and analogies in many other languages, and it enjoys a long history in English. Historians of the language date the middle in its present shape from the early fifteenth century and the scholar F. Th. Visser cites this 1437 example:

Grete pleynte … of Wynes made nygh the seide Portz come into this londe … atte that tyme … the tonne of such Wynes solde better chepe by a gretter quantite than it is nowe.

In other words, the wines sold well.

A recent study by linguist Marianne Hundt found various examples of the middle in advertising product descriptions, like ones that refer to “sleepwear that machine washes,” surfaces that “wipe clean easily,” and even “a turtleneck collar that cuddles easily below the neck.”

The middle voice is anything but middling.

Featured image: “ Books in Library” by Jessica Ruscello. Public Domain via Unsplash.

The post What is the Middle Voice? appeared first on OUPblog.

May 31, 2019

Keep eating fish; it’s the best way to feed the world

The famous ocean explorer, Sylvia Earle, has long advocated that people stop eating fish. Recently, George Monbiot made a similar plea in The Guardian – there’s only one way to save the life in our oceans, stop eating fish – which, incidentally, would condemn several million people to starvation.

In both cases, it’s facile reasoning. The oceans may suffer from many things, but fishing isn’t the biggest. Earle and Monbiot’s sweeping pronouncements lack any thought for the consequences of rejecting fish and substituting fish protein for what? Steak? That delicious sizzler on your plate carries the most appallingly large environmental costs regarding fresh water, grain production, land use, erosion, loss of topsoil, transportation, you name it.

Luckily for our planet, not everyone eats steak. You’re vegan, you say, and your conscience is clean. An admirable choice – so long as there aren’t too many of you. For the sake of argument and numbers, let us assume that we can substitute plant protein in the form of tofu, made from soybeans, for fish protein. Soybeans need decent land; in fact it would take 2.58 times the land area of England to produce enough tofu to substitute for no longer available fish. That extra amount of decent arable land just isn’t available – unless we can persuade Brazil, Ecuador and Columbia to cut down more of the Amazon rainforest. We would also add 1.71 times the amount of greenhouse gases that it takes to catch the fish.

And, again for the sake of argument, were we to substitute beef for fish, we would need 192.43 Englands to raise all that cattle and greenhouse gases would rocket to 42.4 times what they are from fishing.

But aren’t there alternatives that we can eat with a clean conscience? It depends. First, we must accept the inescapable truth that everyone has to eat. You and I and another few billion humans right down to the single cell organisms. The second inescapable truth arises from the first but is often ignored, is that there is no free lunch. The big variable in this business of eating is deciding the appropriate price to the environment.

There are costs to each mouthful. By the time you swallow it, that mouthful has racked up a huge amount of unseen costs: production of greenhouse gases, pollution of air and waterways, soil erosion, use of freshwater, use of antibiotics, and impacts on terrestrial and aquatic biodiversity.

After extensive studies, it turns out that some fish have the lowest green house gas footprint per unit of protein.

However, it doesn’t have to be that costly. Ocean fisheries don’t cause soil erosion, don’t blow away the topsoil, don’t use any significant freshwater, don’t use antibiotics and don’t have anything to do with nutrient releases, that devastating form of pollution that causes algal blooms in freshwater and dead zones in the ocean. After extensive studies, it turns out that some fish have the lowest green house gas footprint per unit of protein. Better even than plants. Sardines, herring, mackerel, anchovies and farmed shellfish all have a lower GHG footprint than plants, and many other fisheries come close.

A ringing endorsement of fish over meat came in 2013, when Andy Sharpless, the CEO of the conservation group Oceana, pointed out that you can sustainably produce food from the sea at low environmental cost. In his book, The Perfect Protein: The Fish Lover’s Guide to Saving the Oceans, Sharpless says, “What if there was a healthy, animal sourced protein, that both the fats and the thins could enjoy without draining the life from the soil, without drying up our rivers, without polluting the air and the water, without causing our planet to warm even more, without plaguing our communities with diabetes, heart disease and cancer?” His answer was to eat fish.

There has been plenty of criticism of commercial fisheries, mostly focused on the impacts on marine ecosystems – fishing certainly reduces the abundance of fish in the ocean, and also non-target species like marine birds, mammals and turtles. But consider the alternative.

Suspend, for a minute, your image of food from the land as it appears to most of us in grocery stores or farmers’ markets – beautifully arranged vegetables, tasty bread, pretty cuts of meat as well as pre-cooked, pre-packaged, eternally preserved fast food. Then cast your minds to how and from where it comes, the raw material from a field. The land as it once was has been totally transformed by farming, replacing original habitat by clearcutting every type of existing flora and replacing it with exotic species, that would be grains, vegetables and fruit trees. Farming, be it agrobusiness or subsistence, essentially eliminates the habitat for indigenous species, and thousands of them have gone extinct because of food production, whereas no marine fish is known to have gone extinct from fishing. The ocean will remain the ocean, though of course we have to manage fish stocks well. We should press our governments to manage fisheries sustainably and minimize the environmental impacts of fishing.

Let’s give a final thought to the reality of boycotting fish and commercial fishing. The need for protein in this world is huge, and we certainly must not waste it. Fishing fleets are guided by quotas set by management and what Earle and Monbiot might boycott, will be shipped and gratefully eaten elsewhere.

Featured image: “Pile of Fish” by Oziel Gómez. Free for use via Pexels.

The post Keep eating fish; it’s the best way to feed the world appeared first on OUPblog.

Predicting the past with the periodic table

Predicting the future is the pinnacle of what science can do. It’s impressive enough for a scientist to look at existing data and compose a theory explaining it. It’s even more impressive for a scientist to predict what data will look like before they are collected. The periodic table is central to chemistry precisely because it has both explanatory and predictive power.

From the time the periodic table was first assembled, it has helped predict future chemical data. But the periodic table applies to more than just chemistry, and it has predicted future data in other areas as well. Here is a case in which the periodic table helped predict biological data—the biochemical timing of certain genes—before those genes were found and sequenced.

Instead of just predicting the future, the periodic table predicted the past—or rather, it predicted future data about the past.

The predictive power of the periodic table was evident from the beginning. Exactly 150 years ago, Dmitri Mendeleev wrote chemical properties on 63 cards and slid them around in history’s most productive version of Solitaire. Once Mendeleev recognized how these cards stack up in groups of eight, he established the basic order of the periodic table. This order revealed four gaps in the table, which Mendeleev predicted would be discovered in the future as elements with particular atomic weights and other chemical properties. Mendeleev’s table predicted scandium, gallium, technetium, and germanium before any of these were isolated in a lab.

Before Mendeleev, other chemists had organized other periodic tables, but these tables aren’t used anymore because they were not predictive.

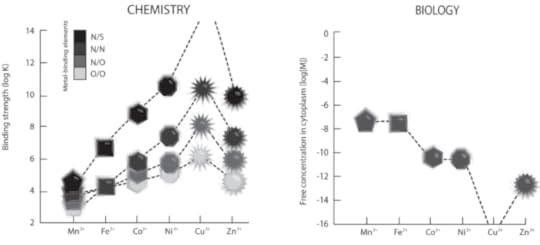

Some of these predictions related to Mendeleev’s periodic table had implications beyond chemistry, extending to biology and geology. One such prediction began 66 years ago with a pair of inorganic chemists, who found that the periodic table helps predict how transition metals work. They measured how tightly six transition metal ions bind to non-metals. When they arranged the metals in periodic table order, no matter which non-metals they used, they found a graph with a consistent upside-down “V”, peaking at copper (see the graph on the left).

Figure 1. The Irving-Williams series of metals binding ligands (left) and cytoplasmic concentrations of free ions (right) for divalent transition metals. Graphs constructed by Mary Anderson Chaffee.

Figure 1. The Irving-Williams series of metals binding ligands (left) and cytoplasmic concentrations of free ions (right) for divalent transition metals. Graphs constructed by Mary Anderson Chaffee.

This means that copper, on the right side of the transition metals, sticks to pretty much anything, while manganese, at the far left, sticks to things far more weakly. This simple trend proved powerful in the field of inorganic chemistry. This graph is taught to chemistry majors today, named after the two chemists, as the “Irving-Williams series.”

One of the chemists was Robert J.P. Williams (1926-2015), who was only an undergraduate at the time. He went on to write a foundational inorganic chemistry textbook and made discoveries ranging from how the iron in hemoglobin works to how mitochondria create cellular energy. Williams liked to apply chemical reasoning to biological contexts, with considerable success.

During the final decades of his life, Williams expanded his scope and applied chemical reasoning to the four-billion-year history of life on this planet. He made a bold prediction: life evolved according to a predictable chemical sequence, which itself followed the order of the periodic table.

To reach this conclusion, Williams started with the series that carries his name. He observed that cells are constrained to follow the Irving-Williams series when they pump metal ions in and out to maintain particular metal concentrations inside the cytoplasm. Concentrations of sticky ions like copper must be kept low lest they stick to the wrong thing, while less sticky ions like manganese can be kept at higher concentrations. This results in a graph of cytoplasmic transition metal concentrations being the exact inverse of the Irving-Williams series: when binding is tight, concentrations are low, and vice versa (see the graph on the right). This general rule applies to life at all places – and at all times.

Williams combined three observations to make a prediction:

Chemical observation: Transition metal stickiness follows the periodic table order.Geological observation: Oxygen increased in the air over billions of years and oxidized the entire planet, including some transition metals.Biological observation: Cells need to use metals that are dissolved and free in solution, not stuck in a big chunk of rock.By following the chemical rules of how oxygen would react and how metals combine and dissolve, Williams argued that life on the ancient earth could only use elements on the left side of the series (manganese, iron, cobalt, and nickel) while more recent, complex life use more elements on the right side of the series (copper and zinc).

The record of which metals life used, and when the metals were used, is written in thousands of genes found in millions of organisms. Williams predicted what future gene sequencing would reveal before DNA sequencing technology came of age, revealing what genes were found in organisms across the tree of life and which metals they used. By the middle of the first decade of the 21st century, enough data was in, allowing three separate groups to confirm Williams’ theory: indeed, ancient organisms emphasized the left side of the series and new organisms the right.

Because the periodic table is universal, Williams’s ideas are also universal and continue to apply to data yet to be collected. Other water-based planets should follow the Irving-Williams series and alien life should use the same metals for the same biochemical jobs (if confounding astrobiological factors don’t confound). What’s especially exciting is that we are moving into an age of discovery in this particular area. Exactly like DNA sequencing gave data about natural history a decade ago, over the next decade, astrobiology should give data about exoplanets’ atmospheric chemistry that may start to reveal how Williams did.

Williams looked into life’s history and saw the pattern of the periodic table behind it. He looked past the chaos of biochemistry and geology to the orderly columns of the periodic table scaffolding and constraining the possibilities, setting chemical rules and sequences for the planet to follow. Williams showed where the biological data would go, and later, the biological data followed his theory.

Mendeleev could not have anticipated this when he was shuffling cards around 150 years ago, but the order of elements that he discovered set a chemical order for both mineral and biological evolution on this planet. Who knows? It may have done so on others as well.

The post Predicting the past with the periodic table appeared first on OUPblog.

May 30, 2019

Defining Central Europe in the aftermath of World War I

The Great War ended the age of empires in continental Europe. National narratives of the successor states have it that they materialized like the proverbial jack-in-the-box in 1918. In reality, the transition from empire to nation state was a process that lasted years, and thus prolonged the violence of the World War long into the postwar area.

It is only logical, if one thinks about it: in Central Europe, a vast area between Russia and Germany was turned into a tabula rasa on which now new borders had to be drawn. It certainly does not come as a surprise that this was not achieved by peaceful means. In 1919, while peace was established in Paris, fighting went on in Central Europe.

This continuation of conflict was a tragedy for a region that had witnessed some of the fiercest battles of the Eastern Front. Wartime destruction, famine, and epidemics were ubiquitous. After 1918, its population was still suffering, starving, dying. And yet peace was only a distant dream. The immediate postwar experience of the people of Central Europe contrasted highly with the national bravado voiced by the elites in their respective capitals.

A large majority of the new citizens of emerging Central European countries—predominantly peasants—had no clear idea what the new ethnic nation states were supposed to mean. Central Europe was populated by people speaking Lithuanian, Ukrainian, Russian, Yiddish, Czech, Slovak, or German, with no clear boundaries running between them. In prewar censuses, they even had difficulties to grasp the concept of nationality, and in consequence, an alternative category—tutejsi (locals)—had to be added. As subjects of empires until 1918, the idea that they should suddenly be citizens of different states came to them as a shock: “Other times had come,” a peasant noted in his memoir on Polish independence in 1918. “The village woke up because everything was shaking all around. They tell us that there’ll be a Poland and it’s already taking shape, though it’s still a bit weak, but slowly getting stronger. The peasants don’t want to believe it, because we’ve always been told that this here’s Russia and Russia it will be, and now, all of a sudden-hocus-pocus-it’s Poland.”

The immediate postwar experience of the people of Central Europe contrasted highly with the national bravado voiced by the elites in their respective capitals.

From late 1918 onwards, cities, towns, and villages far from the state centers that struggled for survival on a daily basis were drawn into the new contest for national supremacy. Neighbors that had been living together—not conflict-free, but by and large peacefully—under imperial rule for ages overnight were turned into enemies by competing politicians and agents of nationality which claimed them as their citizens. Did they embrace the struggle for national independence with enthusiasm? Were they sending their sons unhesitatingly to the diverse fronts that opened when the arms of the Great War fell silent? Far from it: in the contested borderlands of Central Europe, the passage from war to peace was experienced as a fratricidal civil war. Another peasant in the Lithuanian-Polish borderlands complained: “Now, this is Lithuania, and that’s Poland. It used to be one, but now there’s a border between Bereźniki and Ogrodniki; there’s a war on. Is that how things should be? Don’t we all go to the same church? Isn’t it a disaster that brothers are divided and fighting?”

Geographically in the eye of the cyclone, the emerging ethnic Polish nation state claimed territories that hosted minorities of almost all nations involved in the Central European Civil War. Between 1918 and 1921, it was in a permanent state of declared or undeclared war on literally all frontiers except the Romanian.

For political scientists, the notion of the diverse postwar conflicts in Central Europe as a civil war might be provocative, since the term usually refers to conflicts below state level, while here, different states were involved. The counter-argument is that those very states were not fully developed yet, since their borders and population still had to be defined, and their state institutions—above all a functioning army—had to be built. Furthermore, the local people experienced those conflicts as a civil war, not as wars between nations. With the words of historian David Armitage: “Civil war is, first and foremost, a category of experience; the participants usually know they are in the midst of civil war long before international organizations declare it to be so.” To bring both arguments together: The Central European Civil War marked the transition from empires to nation states. In its fires, state institutions were built and state citizenship was defined.

Featured image credit: “Map showing the political divisions of Europe in 1919 after the treaties of Brest-Litovsk and Versailles” by unknown author. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons .

The post Defining Central Europe in the aftermath of World War I appeared first on OUPblog.

May 29, 2019

Etymology gleanings for May 2019

Ethnic phrases

In connection with the discussion of take French leave, Dutch uncle, Welsh rabbit, and the like (see the posts for May 15 and May 22, 2019), I was asked whether other idioms with such ethnic names exist. They probably do, but in my database, I only stumbled upon have the Danes “to have diarrhea.” The idiom, allegedly recorded in the 17th century, was mentioned in Notes and Queries for 1878, with reference to the horrors of the Viking raids. I notice that the Vikings and their gods have been made responsible for several English idioms, and in all cases in which I could check the facts, the explanations turned out to be wrong. The plant danewort (= dwarf elder) was also said to be a laxative. The association with the Danes in this phrase looks like a product of folk etymology, though it may be a coinage by some post-Renaissance erudite, who associated the plants growing in the places of old battles with the tragic events of the Middle Ages. I don’t know whether the leaves of the danewort are or were ever used as a laxative. A comment about taking French leave (read it in the relevant post) is suggestive, but the English idiom is apparently native, because the French (to avenge themselves?) say filer à l’anglaise.

A rare linguistic question

Egg on his face. Image credit: “Egg on yer face-col” by Robin Hutton. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 via Flickr.

Egg on his face. Image credit: “Egg on yer face-col” by Robin Hutton. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 via Flickr.Students of linguistics never write me, except that once every two or three years, someone asks what it takes to become an etymologist (and I explain that it takes one’ whole life). So I hasten to answer a recent query from abroad. This was the question: “In books on English grammar, I sometimes find mention of the zero article. Is zero article the same as the absence of the article?” No, not quite. In linguistics, zero refers to the meaningful absence of something. Compare the egg is in the basket (obviously, the speaker refers to the egg mentioned before), have you never seen an egg? (any egg), and there is egg on your lip (the stuff, probably yolk). One can also cite less obvious cases: in an Icelandic saga, such events are commonplace (in any saga), in the Icelandic saga, such a detail looks odd (the saga you have been talking about, though perhaps the generic use of the article), and in Icelandic Saga, one often finds references to sorcery (Icelandic Saga as a genre). Such examples are not restricted to the use of the articles.

Chickaleary

Is she chicaleary? Image credit: “Naughty but nice” by Trevor King. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

Is she chicaleary? Image credit: “Naughty but nice” by Trevor King. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.A correspondent writes: “In Barbara Kingsolver’s recent novel Unsheltered, on p. 328, a young woman of the 19th century says of her sister, ‘I’m sure she’s all chickaleary now, drinking chocolate….’ But none of the citations I find seem to fit that usage.” On April 4, 2007, I wrote a post titled “One, Two, Three, Alairy” and in passing mentioned the dialectal word chickaleary “aged pedestrians on winter mornings.” Our correspondent discovered this post, and I decided to reread it. To my amazement, I found numerous comments, the most recent one going back to May 18, 2019 (!). In 2009, the University of Minnesota Press published my voluminous Bibliography of English Etymology. Ten years ago, I had access to a single old citation (from Blackwood’s Magazine; there, the word was traced to Scottish Gaelic), but later, I came across some more discussion of this noun (not an adjective) in Manchester Notes and Queries. If anyone is interested, in the future, I may briefly summarize that exchange. To me, chickaleary looks like chick-a-leary, with –leary meaning the same as alairy (discussed in detail in the 2007 post), and a, inserted, as in cock-a-doodle-doo and many other words, including perhaps rag-a-muffin. A chicken with its legs more or less apart will fit the idea of an aged person on a slippery wintry road, though, if chickaleary is indeed Celtic, the English transformation may be due to folk etymology (again folk etymology!). The word is almost certainly northern. Kingsolver’s character must have been jittery (with excitement?), while drinking chocolate.

Our favorite words

Two and occasionally three times a year, I speak on language matters on Minnesota Public Radio (MPR News with Kerri Miller). Last week’s topic was “Our Favorite Words.” People called with comments and questions about the words they like. The choices were curious and confirmed the importance of sound symbolism in the life of language. Both men and women, regardless of their age, “like” words that more or less suggest their meaning. One such word was discombobulate. And indeed shouldn’t it mean “confuse, perplex”? Shenanigans was among the “favorites,” and so was danggonnit (which I have seen spelled as two words: dang gonnit, something resembling darn it, but looking like dang, gone it!). Other people enjoy bookish words: onomatopoeia (this message warmed the cockles of my heart), hyperbole, and diaphony. Some of the comments were very much to the point: “Chutzpah is my favorite. You can say it strongly and the way you pronounce it helps with the meaning of the word (which means you have the nerve to stand up),” spooky (“it’s fun to say”), or egregious (“it adds the right amount of emphasis”).

Caldo! Image credit: “Close Up Photography of Brass Hot Faucet”

Caldo! Image credit: “Close Up Photography of Brass Hot Faucet”by Pixabay. Public domain via Unsplash.

To be sure, sometimes we believe that the sound shape of a noun or a verb matches its meaning because we know the meaning and believe that the connection is natural (hence the surprise of English speakers that Italian caldo means “hot”), but a strict etymological analysis may confirm the sound-imitating or expressive origin of the word. It is amazing how often monosyllabic verbs like dig, put, and kick are dismissed in dictionaries as being of unknown origin. Indeed, an emphatic or expressive origin cannot be demonstrated (let alone proved), and language historians like precision. Discombobulate is certainly not a product of so-called primitive creation, but the pseudo-scholarly, jocular impulse behind coining it must have been similar. This brings me to biffy, another caller’s favorite word. Biffy is “of unknown origin,” and my database does not contain a single note on it. The names of such places go all the way from totally arbitrary (like john) to genteel (restroom), from apparently native but hopelessly obscure (loo) to bookish, borrowed, and transparent (privy, lavatory). The (sound-imitative?) verb biff “to strike” is well-known. Could it exist as a synonym of break wind? The common Indo-European (yes!) verb fart, from perd, that is, prd-, does look like an onomatopoeia. Among the countless synonyms for toilet, I found thunderbox. Anyway, skip to the loo or read my post of April 25, 2007.

In that talk show, I was indeed on the same wave length with the listeners. I too have a soft spot for “funny” words like tatterdemalion and nincompoop on the one hand and such “otiose” bookish monsters as lubricity and adumbrate on the other. Two people complained that, when they used “hard words,” those around them disapproved: “Don’t show off.” Naturally, being better educated and more eloquent than one’s neighbor is an unforgivable sin.

From newspapers

“Now that unemployment is at historic lows, thanks to we baby boomers retiring to the tune of 10,000 a day….” The tune is sweet, but what about the grammar? The use of we after prepositions has been noticed and discussed. Are we at the beginning of some ugly trend, like the ubiquitous infinitive splitting (to not see, to often watch, and the like)? Change in morphology often (if not always) begins as native speakers’ deafness to established rules. Shall we soon say something like everything depends on we?

“One of North Korea’s only allies.” Isn’t the redundancy obvious? Nearly half of the panel employed by the fifth edition of the American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language found the phrase one of the only acceptable. Yet such a locution does not seem to make sense, does it?

SPELLING REFORM (NOTE): The deadline for receipt of submissions of alternative spelling schemes is May 31, this year. The website is: <spellconf.pss@gmail.com>.

To be continued next week.

Featured image: “Sambucus ebulus” by unknown author. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Etymology gleanings for May 2019 appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers