Oxford University Press's Blog, page 191

May 3, 2019

Eight facts about past poet laureates

The poet laureate has held an elevated position in British culture over the past 350 years. From the position’s origins as a personal appointment made by the monarch to today’s governmental selection committee, much has changed about the role, but one thing hasn’t changed: the poet laureate has always produced poetry for events of national importance, particularly in relation to royalty. Recent poet laureates have produced poetry commemorating the 60th anniversary of Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation, the oldest surviving World War I veteran, and various royal weddings over the years.

This May, a new poet laureate is due to be announced in the UK. In celebration of this occasion, enjoy these eight facts about past poet laureates from 1668 to the present day.

1. Ben Jonson was the unofficial first poet laureate

Playwright and poet Ben Jonson is sometimes cited as the first poet laureate: in 1616, James I granted him a royal pension in recognition of his services to poetry. However, the post was not made official until the appointment of John Dryden by Charles II in 1668, when a formal warrant was issued awarding Dryden the title

2. One laureate was dismissed on religious grounds

After twenty years as laureate, John Dryden became the first – and only – poet laureate to be removed from the post in 1688. Dryden was dismissed for refusing to take the oath of allegiance to the new sovereigns, William and Mary; he was a Catholic convert, and risked being prosecuted for treason by remaining in public office in the court of the Anglican monarchs, so the Anglican Thomas Shadwell became laureate in his place.

3. Laureates composed odes to the monarch’s birth

Thomas Shadwell didn’t waste his three years as poet laureate, establishing a new tradition: writing poetry in honour of the monarch’s birthday each year. Subsequent poet laureates were also required to write poems for other major court and national occasions such as marriages, deaths, and victories. This requirement died with Robert Southey in 1843; since then, laureates have been expected to write poems for any significant country-wide events on a voluntary basis.

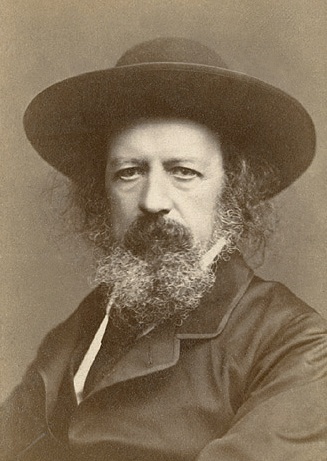

Alfred, Lord Tennyson by Jbarta. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Alfred, Lord Tennyson by Jbarta. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.4. Young or old can fill the role

Whether seasoned poet or a young prodigy, any poet could become laureate regardless of age or writing experience. The youngest poet to be appointed laureate was Laurence Eusden, who accepted the position in 1718 at the age of 30. In this case, youth did not spawn brilliance: Eusden’s poetry was mocked and satirised by other writers at the time, and his poems aren’t widely known or circulated today. The eldest to be named laureate was well-known romantic poet William Wordsworth, who was 73 when he became laureate in 1843. Wordsworth was initially reluctant to accept the post due to his age, but when he was assured that nothing would be expected of him as poet laureate, he accepted, and did not write a single official verse throughout his tenure.

5. Three years passed with no laureate following the death of Alfred, Lord Tennyson

The longest serving poet laureate, Alfred Tennyson, was so well-loved by Queen Victoria that there was a break of over three years following his death in 1892 before the next laureate was appointed. Indeed, Tennyson’s legacy extends beyond his 42 year tenure as he remains a widely revered poet today, with poems including “The Charge of the Light Brigade” – which he wrote as laureate during the Crimean War – still being circulated and studied widely.

6. Three poets have refused the post

In the search for the next poet laureate, several poets – notably Benjamin Zephaniah – have ruled themselves out of the shortlist; this aversion to becoming poet laureate is nothing new. In the past, the laureateship has been officially refused on three occasions: by Thomas Gray in 1757, by Sir Walter Scott in 1813, and by Samuel Rogers in 1850.

7. Serving as laureate is no longer a lifelong commitment

Until recently, poets were awarded the laureateship for the remainder of their lives. The longest serving poet laureate was Tennyson, who held the position for 42 years during Queen Victoria’s reign. Since Andrew Motion was appointed in 1999, the laureateship has been offered on a ten year fixed term basis to allow more poets the opportunity to be poet laureate.

8. Few laureates have left a lasting legacy

How many poems do you know that were written by poet laureates? While the first and most recent laureates’ names likely ring a bell – John Dryden and Carol Ann Duffy – there have been few notable poets in between, and even fewer notable poems. Among those you have likely come across are “I wandered lonely as a cloud” by Wordsworth, “In Memoriam” by Tennyson, and the Christmas carol “While shepherds watched their flocks by night” by Nahum Tate. How long will the next laureate’s legacy last? That remains to be seen.

Featured image: Writing, desk, paper, and stationary by Clark Young. Public Domain via Unsplash.

The post Eight facts about past poet laureates appeared first on OUPblog.

How research and policy affect responses to sexual violence

Sexual violence in war has never been as visible as in the last ten years or so. We talk about it in global and national policy spaces, the media reports about sexual violence in conflicts around the world, and research in this area is booming. This is a major change, as sexual violence has long been considered irrelevant when thinking of war. The United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325 on Women, Peace and Security, issued in 2000, reflects this interest in valuing a gender perspective in global politics. This is a positive development for peace, justice, and human rights advocates, who have argued that the dynamics of war and peace are inherently gendered and therefore have different impacts on women and men. Cynthia Enloe, for instance, has highlighted the importance of paying attention to women’s experiences before, during and after war in order to better understand women’s contributions to both war and peace.

In the mid-90s after journalists reported on gender-based atrocities in the former Yugoslavia and in Rwanda, observers began to frame sexual violence as a weapon of war. Perpetrators used rape to fragment and destroy communities. In 2018 Denis Mukwege and Nadia Murad were awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for their work on efforts to prevent conflict-related sexual violence. If we can abolish landmines or chemical weapons, should we not be able to abolish sexual violence?

But sexual violence is much more than a weapon. In addition to fragmenting communities, humiliating individuals, and changing the ethnic composition of a population, sexual violence has a range of impacts. For example, it may reinforce dominant ideas about gender and sexuality as well as damage social bonds within families and communities. Importantly, sexual violence may reflect and exacerbate patterns of inequality such as along the lines of race, ethnicity, class, religion, gender, and sexuality. Nevertheless, sexual violence is not limited to wartime, and in many contexts, violence against women continues into peacetime.

When global policy makers and the media focus on sexual violence in wartime it is important; it helps ensure that attention and funding is available to provide support and redress for survivors. We need more research in order to help understand patterns and experiences, and perhaps develop better mechanisms for intervention at earlier stages. However, there are also negative consequences with an exclusive focus on sexual violence. Exceptionalising rape in war has the effect of normalising and ignoring widespread rape and abuse in peacetime or other forms of gender-based violence that take place on the margins of war. Undue attention to conflict-related sexual violence among certain populations can obscure other urgent problems, revictimize people, ignore relatively uncommon victims (e.g. men and boys), or make invisible certain perpetrators (e.g. husbands and boyfriends). Excessive attention for one particularly vulnerable group can create research fatigue. It can have the effect of imposing very specific definitions of abuse and harm and even become an unreliable indicator for what contexts are potential security threats.

The research community has an important responsibility to ensure it makes a meaningful contribution to outcomes for survivors. A critical approach will enable us to raise questions around what we know, how we know it, and importantly, how our methods and approaches affect different forms of intervention. But ethical and reflexive research alone cannot prevent negative effects and consequences; we need the global community of policy makers to engage with such critiques as well.

Featured Image Credit: ‘We all have fears’ by Melanie Wasser. CC0 Public Domain via Unsplash.

The post How research and policy affect responses to sexual violence appeared first on OUPblog.

May 2, 2019

How historians research when they’re missing crucial material

How do you write about an historical topic when the principal sources that would reveal what happened and why no longer exist? Good case studies exist in the Royal Navy’s efforts in the run-up to the First World War to reform the spirit ration (the alcohol allocated to members the Royal Navy) and to suppress homosexuality. In both these instances, policies were in place and actions taken, but there is a near void in the government records.

This may be deliberate. The Admiralty Record Office Digests, the huge leather-bound volumes in which all of the files sent for safe-keeping to the Navy’s central document repository are carefully listed, contains detailed and specific references to numerous important papers with a bearing on what was then euphemistically termed “unnatural crime”. So there can be no doubt that substantial paperwork on this topic once existed. Moreover, some of the annotations in the digests strongly imply the Navy intended to retain the most important of these files for posterity. Yet, none of them are available today, having been ‘weeded out’ by the end of the 1950s. Accidents do happen and people make mistakes, but it is hard to avoid the impression that these documents are no longer present because someone did not want them to survive.

If the trail on the suppression of homosexuality leads to a dead end, the situation is even worse with regard to the spirit ration. After 1908, the pages of the digests covering this area (“Indulgences” in Admiralty parlance) are literally blank, suggesting that no papers on this topic were ever registered in the Record Office. In theory this implies that in the immediate run-up to the First World War, rum was so insignificant a part of naval life that the Admiralty secretariat never needed to create a single file on the subject. Thus, not so much a trail with a dead end as no trail at all.

In the case of the spirit ration, this is evidently not true. In March 1912, the new First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill, announced to Parliament that he would examine the policy of giving sailors a daily tot of rum. One year on he had outlined the results to an expectant House of Commons. During those twelve months it is inconceivable, given how bureaucracy works, that such an examination would have produced no documentation. On the contrary,

official papers must once have existed, but, for whatever reason, they had left none of the usual traces in Whitehall. Fortunately, if the Admiralty did not choose to keep records on this topic or even to register that they had once existed, several important figures were more conscious of the needs of posterity and personally retained relevant correspondence.Churchill was one; Prince Louis of Battenberg, the Second (soon to be First) Sea Lord was another. His private papers are especially useful. Not only do they refer explicitly to the supposedly non-existent official documents – confirming, as no other source does, that they had once existed – but, in addition, they succinctly explain what the policy was and how it had come about. As all historians know, private papers often add colour to the official record. In this instance they cover for the complete absence of an official record.

The situation with regard to the suppression of homosexuality is different in almost all respects. Unsurprisingly, private papers do not do much to illuminate this topic. Fortunately, unlike with the spirit ration, there is ample evidence in the digests that official records had been created, registered and retained until the 1950s. Moreover, the digest entries are remarkably detailed, providing the names of suspected culprits, the locations of the alleged contact, and the actions that were taken by the authorities. Where new regulations or procedures resulted, the number and date of the subsequent confidential circular were recorded. Such information provides avenues into other documentary sources. It’s possible to cross reference names to individual service records, court martial registers, medical officers’ journals, and Record Office indexes. All of these provide little snippets of information, insignificant on their own, but collectively providing a great deal of important information. More vital still, it is possible for historians to use the date and number of confidential circulars to track down specific rule changes and the documents that explained them. They are not always easy to find, as some of the confidential circulars are still held within the Ministry of Defence. But once obtained and viewed in conjunction with the information from the other sources mentioned above, they tell the story that the “weeded” files no longer can.

It can be deeply frustrating to know that that all the answers on a particular topic were once on a scrap of paper that is now gone forever. However, neither the blank page nor the dreaded word ‘weeded’ need be an insuperable barrier to historical research. Alternative sources nearly always exist; it is just a matter of finding them.

Featured image credit: HMS Illustrious on Loch Long by Pepe Hogan. P ublic sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0. via Ministry of Defense.

The post How historians research when they’re missing crucial material appeared first on OUPblog.

9 forgotten facts about Leonardo da Vinci

For over 500 years, the masterworks of Leonardo da Vinci have awed artists, connoisseurs, and laypeople alike. Often considered the first High Renaissance artist, Leonardo worked extensively in Florence, Milan, and Rome before ending his career in France, and his techniques and writings influenced artists and thinkers for centuries after his death.

Today, to commemorate the 500th anniversary of Leonardo’s death, here are nine surprising facts about his work:

In a letter to Ludovico Sforza, ruler of Milan in 1483, Leonardo concentrated on his capabilities as a military engineer. He listed ten categories of military devices that included bridges, guns, and mortars; he only mentioned that he could “undertake sculpture of marble, bronze and clay, similarly in painting whatever can be done, to bear comparison with anyone else, whoever he is” at the end of the letter. Throughout his life, Leonardo flourished when receiving regular income from a court, whereas he struggled when working on commission.Leonardo painted two versions of The Virgin of the Rocks due to a legal dispute that involved “some of the lengthiest and most confusing documentation for any Renaissance painting.” The version today seen at the Louvre in Paris is most likely the original and had been painted as an altarpiece for the S Francesco Grande in Milan in the 1480s. Leonardo and his fellow painters believed the value of the panel was worth more than the original commission sum so the painting was never delivered; the dispute was finally resolved over two decades later in 1506 when arbitrators ordered Leonardo to complete the painting within two years. This second version is believed to be the painting now exhibited at the National Gallery in London. Studies of the Arm showing the Movements made by Biceps, c. 1510, a drawing by Leonardo da Vinci. Public Domain via

Wikimedia Commons

..The

Last Supper

, a fresco for the monastery of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan, was Leonardo’s major achievement of the 1490s, painted while out of favor with his patron, the aforementioned Duke Ludovico. Leonardo’s use of an experimental medium to make the fresco look like an oil painting was difficult and the work deteriorated quickly. A successful restoration attempt was not made until the early 20th century, after centuries of neglect and humidity. Its most recent restoration began in 1979 and was completed in 1999, though this confirmed that only small flakes of original paint remained in some areas once top layers of paint were removed. While the fresco has spent most of its existence in states of disrepair, early copies made by students of Leonardo have survived and are a reason for the image’s centuries-long cultural resonance.The

Mona Lisa

is arguably the world’s most famous painting. Now housed at the Louvre, the portrait is believed to depict the wife of Francesco del Giocondo, a Florentine merchant, which is why the painting is also called La Gioconda. According to 16th century biographer Giorgio Vasari, Leonardo worked on the painting for over 4 years, never delivering it to his patron. The subject’s mysterious smile, combined with Leonardo’s distinct sfumato (Italian for “smoked”) style that veils the face in a hazy atmosphere, has garnered much speculation and controversy over the years.Based on the ubiquity of the Mona Lisa and Last Supper in popular culture, it may be a surprise to some that only 10 completed paintings by Leonardo survive. (A few unfinished works also remain, as well as a small group of paintings that were possibly completed as part of a studio.) Conversely, approximately 4,000 sheets of the accomplished draughtsman’s technical drawings, anatomical sketches, and architectural plans survive.Leonardo’s definition of music was “figurazione delle cose invisibili” (shaping of the invisible.) In his paragone (the introduction to his famous, posthumously published treatise on painting), his philosophy of music was accorded the highest place among the arts after painting.

Studies of the Arm showing the Movements made by Biceps, c. 1510, a drawing by Leonardo da Vinci. Public Domain via

Wikimedia Commons

..The

Last Supper

, a fresco for the monastery of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan, was Leonardo’s major achievement of the 1490s, painted while out of favor with his patron, the aforementioned Duke Ludovico. Leonardo’s use of an experimental medium to make the fresco look like an oil painting was difficult and the work deteriorated quickly. A successful restoration attempt was not made until the early 20th century, after centuries of neglect and humidity. Its most recent restoration began in 1979 and was completed in 1999, though this confirmed that only small flakes of original paint remained in some areas once top layers of paint were removed. While the fresco has spent most of its existence in states of disrepair, early copies made by students of Leonardo have survived and are a reason for the image’s centuries-long cultural resonance.The

Mona Lisa

is arguably the world’s most famous painting. Now housed at the Louvre, the portrait is believed to depict the wife of Francesco del Giocondo, a Florentine merchant, which is why the painting is also called La Gioconda. According to 16th century biographer Giorgio Vasari, Leonardo worked on the painting for over 4 years, never delivering it to his patron. The subject’s mysterious smile, combined with Leonardo’s distinct sfumato (Italian for “smoked”) style that veils the face in a hazy atmosphere, has garnered much speculation and controversy over the years.Based on the ubiquity of the Mona Lisa and Last Supper in popular culture, it may be a surprise to some that only 10 completed paintings by Leonardo survive. (A few unfinished works also remain, as well as a small group of paintings that were possibly completed as part of a studio.) Conversely, approximately 4,000 sheets of the accomplished draughtsman’s technical drawings, anatomical sketches, and architectural plans survive.Leonardo’s definition of music was “figurazione delle cose invisibili” (shaping of the invisible.) In his paragone (the introduction to his famous, posthumously published treatise on painting), his philosophy of music was accorded the highest place among the arts after painting. Detail of Virgin and Child Enthroned with the Doctors of the Church, 1495, depicting Ludovico Il Moro and his son Massimiliano Sforza. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.According to Vasari in his Le vite de’ più eccellenti pittori, scultori ed architetti (Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects), Leonardo “devoted much effort to music; above all, he determined to study playing the lira, since by nature he possessed a lofty and graceful mind; he sang divinely, improvising his own accompaniment on the lira.” Leonardo played the lira for Duke Ludovico, an instrument that Vasari noted “had built with his own hands, made largely of silver but in the shape of a horse skull – a bizarre, new thing.”Leonardo’s studies of anatomy and physiology led to interesting ideas on how music is created by the human body. Due to the lack of preserving chemicals at the time, he was unable to study the vocal chords or inner ear, but his dissections enabled him to study voice production, facial muscles, the lips and the tongue and their impact on pronunciation, and the hands of musicians.Two of Leonardo’s long-lost notebooks reappeared in 1967 at the Biblioteca Nacional in Madrid. They comprised 700 pages and contained drawings of new types of instruments: new bellows for organetti and chamber organs, a

viola organista

, and a viola a tasti, a “keyed string instrument operated by segments of cogwheels.”

Detail of Virgin and Child Enthroned with the Doctors of the Church, 1495, depicting Ludovico Il Moro and his son Massimiliano Sforza. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.According to Vasari in his Le vite de’ più eccellenti pittori, scultori ed architetti (Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects), Leonardo “devoted much effort to music; above all, he determined to study playing the lira, since by nature he possessed a lofty and graceful mind; he sang divinely, improvising his own accompaniment on the lira.” Leonardo played the lira for Duke Ludovico, an instrument that Vasari noted “had built with his own hands, made largely of silver but in the shape of a horse skull – a bizarre, new thing.”Leonardo’s studies of anatomy and physiology led to interesting ideas on how music is created by the human body. Due to the lack of preserving chemicals at the time, he was unable to study the vocal chords or inner ear, but his dissections enabled him to study voice production, facial muscles, the lips and the tongue and their impact on pronunciation, and the hands of musicians.Two of Leonardo’s long-lost notebooks reappeared in 1967 at the Biblioteca Nacional in Madrid. They comprised 700 pages and contained drawings of new types of instruments: new bellows for organetti and chamber organs, a

viola organista

, and a viola a tasti, a “keyed string instrument operated by segments of cogwheels.”To refer to Leonardo da Vinci as just an artist minimizes his role in numerous areas of study; in addition to painting, sculpture, and drawing, the quintessential “Renaissance Man” left an indelible mark on architecture, engineering, science, philosophy, and even music. These are but a fraction of the accomplishments, theories, and physical works left behind by the polymath.

Featured image credit: Leonardo da Vinci’s fresco of the Last Supper, Santa Maria delle Grazie, 1495-98. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post 9 forgotten facts about Leonardo da Vinci appeared first on OUPblog.

May 1, 2019

Sniff—snuff—SNAFU

I have received several questions about sl– and sn– words and will soon answer them, but today I’ll write about the word that has interested me for a long time, especially in connection with two idioms.

The word is snuff. First there is snuff “a candlewick partly consumed.” Then there is snuff “tobacco for inhaling.” Many dictionaries state that snuff1 and snuff2 are not related. Perhaps they aren’t, but in our search for their origin, we may discover that the term related is not as clear as it sometimes seems. For starters, it is a good idea to be guided by the principle, formulated by Jacob Grimm: while dealing with homonyms, try to find a common etymon for them. (Such an etymon may not exist, but the attempt is worth the effort.)

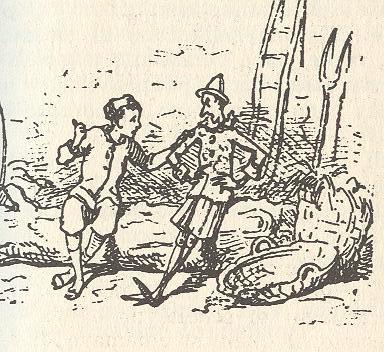

This is Candlewick, Pinocchio’s friend and seducer. Image credit: “An image from ‘Le avventure di Pinocchio'” by Enrico Mazzanti. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

This is Candlewick, Pinocchio’s friend and seducer. Image credit: “An image from ‘Le avventure di Pinocchio'” by Enrico Mazzanti. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.It is not clear why so many sl- words refer to things slippery and sleazy, but the initial group sn– often makes people think about an active nose. For instance, regardless of Dutch snoepen “to eat (on the sly),” the etymon of snoop (originally an Americanism), the English verb suggests nosing around. A snout, we may agree, is a very useful nose. The connection of snoring and sneezing with the nose needs no proof. Sneeze is especially typical. The Old English verb was fnēsan (it had exact congeners in German ad Old Norse) and should have yielded fnese, but in late Middle English, fn– in fnesen was replaced with sn-. I suspect that fnese did not survive because no English word begins with fn, but mainly because sn– fit the sense perfectly. (Or do you say fitted? The history of the past tense of put, set, quit, and their likes is a plot fit for a thriller. I suspect that your little sons and daughters wet their beds when they were babies, but Hamlet definitely whetted Gertrude’s almost blunted purpose.)

Long ago, I wrote a post about the enigmatic word snob (May 14, 2009). Those interested in the present discussion may consult it with some profit. Whatever the origin of snob, it was coined as a term of abuse, the name of someone at whom you could cock a snook(s), a sign of derision and superiority. Snuff “tobacco” acquired its meaning because tobacco was inhaled, or sniffed. The word’s source is apparently Dutch. German has the verb schnupfen “to take snuff” and the noun Schnupfen “a cold,” that is, a disease that produces too much mucus, or snot, in the nose. An overabundance of snot makes one miserable, rather than snotty, but one never knows in what direction associations with the nose will develop. I’ll return to snottiness next week.

And this is a real candlewick, the parent of snuff. Image credit: “Candle wick” by Vive la Rosière. CC BY-SAY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

And this is a real candlewick, the parent of snuff. Image credit: “Candle wick” by Vive la Rosière. CC BY-SAY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.German schnauben means “to snort.” At schnauben, the latest edition of Friedrich Kluge’s German etymological dictionary lists many words of this type, with the conclusion that all of them refer to the nose, sneezing, snot, and so forth. Although they begin with sn-, their final sounds vary, and all such words need not go back to the same source. This is the trouble with all sound-symbolic and echoic formations. Obviously, an etymologist has to account for every sound of the word under discussion, but in this area, doing so proves to be an almost impossible task. I may perhaps be allowed to repeat the metaphor I have used in several of my previous posts. Such words, the plebs of word formation, are like mushrooms growing on a stump: we observe great similarity in the absence of a common root. Or they resemble people wearing the same uniform: in a crowd, they resemble one another, but they have different parents.

If we disregard a few words like snow, whose history goes all the way to the days of the Indo–Europeans, we note with surprise how m many sn-words reached English from Dutch or Low German (Low in this phrase means “northern”). To High German, the same words, sometimes slightly altered phonetically, also came from the north. When a word is borrowed, there must be a reason for it. I have never seen an explanation of why a multitude of sn– words current in the north of the European mainland had such a strong appeal to the speakers of the neighboring areas. Who transmitted them? Snack, snaffle “a bit on a bridle,” snick “to cut, snip,” snap and its synonym snip, snip–snap–snorum “a card game,” snot, snout, snook (the fish), snarl, snuffle “to breathe nosily through the nose” (though not snivel), and possibly sneer and snug are of that origin!

No one will disagree that a snout is a very useful nose. Image credit: “TN State Fair Pig” by Brent Moore. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

No one will disagree that a snout is a very useful nose. Image credit: “TN State Fair Pig” by Brent Moore. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.Snobs tend to snub those who, they believe, are their inferiors, do they not? To illustrate the mess we are in, I would like to retell what Walter W. Skeat said about snuff and snub. At the beginning of each entry, Skeat indicated the language of the word’s origin. At snuff “to sniff, smell,” he wrote Dutch and traced it to Middle Dutch snuffen, related to snuyven (Modern Dutch snuiven) and Dutch snuf “smelling, scent.” Those he compared with a few Swedish and German words, all from the reconstructed root sneub-. Whether such a root existed need not bother us at the moment. Snuff “powdered tobacco” is said to be a derivative of this verb. He labeled snuff “to snip off the top of a candlewick” as English and parallel (whatever parallel means in this context) to English regional snop “to eat off, as cattle do young shoots” and Swedish regional snōppa “to snip off, snuff a candle.” But at the end of the entry he says: “See snub”! Snub is said to be of Scandinavian origin. Among its cognates we find East Frisian (which in this context means “Low German”) snubbe “to snub, chide,” originally “to snip off the end of a thing.”

In this word group, vowels seem to signify nothing and consonants, except for sn-, very little. Why did Skeat think that snuff “candlewick” is English, even though it is so close to Low German schnuppe? The Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology (ODEE) says that this word is of unknown origin. Bu do we have a chance of discovering its origin, that is, of pinpointing its exact source and way of derivation? I doubt it. To complicate matters, this snuff was preceded by its synonym snot! Skeat called snot English, but the ODEE prefers to trace it to Middle Low German/Dutch, even though it too (like Skeat) cites Old Engl. ge-snot (the same meaning), a cognate of German Schmutz “dirt.”

Less than a thousand years ago, we would have said that she is fnesing. Image credit: “Sneeze” by Tina Franklin. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

Less than a thousand years ago, we would have said that she is fnesing. Image credit: “Sneeze” by Tina Franklin. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.It seems that we have a knot that refuses to be disentangled. Perhaps it would be more honest to say that Germanic, mainly Low German/Dutch and to a lesser degree Scandinavian, presents us with nouns and verbs having the structure sn + a vowel (the vowel is usually short) + a voiceless stop (that is, p, t, or k). Many, but not all of them, refer to the activities of the nose. They are products of unbridled language creativity, the result of a language play that followed vague and partly unpredictable rules. People seemed to ask themselves: “What should we call this thing or action?” and answered: “Let us call it’s not or perhaps snuff.” If we were the contemporaries of that game, we might have been able to follow some of the hidden steps, but even that is not clear. Modern slang follows the same pattern and is notoriously hard to etymologize. Are snuff1 and snuff2 related? The answer depends on how closely we want them to be allied.

Unexpectedly, the plot thickens. Germans say mir ist es schnuppe “I cannot care less,” literally, “to me it is tobacco.” Why do they say so, and are they alone in this respect? We will return to the tobacco industry next week.

Featured image: Snapdragon, a snout-shaped flower. “Flowers” by Eirena. Pixabay License via Pixabay.

The post Sniff—snuff—SNAFU appeared first on OUPblog.

Exploring the Da Vinci Requiem

Wimbledon Choral Society and conductor, Neil Ferris, commissioned me to write the Da Vinci Requiem to commemorate the 500th anniversary of Leonardo da Vinci’s death. Leonardo died on 2 May 1519 at the Château du Clos Lucé, Amboise, France; Wimbledon Choral Society will premiere the work in the Royal Festival Hall, London, on 7 May 2019.

Before starting work on the Requiem I remembered that my parents had The Notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci somewhere in their house. In 1946, soon after these translated editions were published, my mother gave them to my father as a wedding present. She knew my father had an enduring fascination with Leonardo and his scientific view of the world. (My father had a place to read natural sciences at university but changed his mind to become a professional flautist.) As a child I loved poring over these large dusty tomes of Leonardo’s, filled with the most extraordinary sketches.

So looking for connections between Leonardo’s philosophical writings and the Missa pro Defunctis (or translated into English, Mass for the dead) became a curiously enriching line of enquiry. Leonardo’s position on religion and faith has always been ambiguous. Many have tried to impose their views on his personal beliefs but who can say what currency these have? Giorgio Vasari, the sixteenth-century art historian (among other things), wrote about Leonardo’s approach to religion: he “formed in his mind a conception so heretical as not to approach any religion whatsoever . . . perhaps he esteemed being a philosopher much more than being a Christian.” However, Vasari omitted this rather provocative statement in a second edition of his Lives of the Painters. Ultimately, it’s the essence of what Leonardo says, how his ideas on life and death marry so well with the Requiem Mass, which intrigues.

Image credit: The Notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci. Used with permission of Cecilia McDowall.

Image credit: The Notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci. Used with permission of Cecilia McDowall.Da Vinci Requiem brings together my chosen Latin texts (Introit, Kyrie, Lacrimosa, Sanctus, Benedictus, Agnes Dei and Lux aeterna) from the Missa pro Defunctis with extracts from The Notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci, and is structured in seven movements in the shape of an arch. The Introit and Kyrie for chorus open the work, and this movement is scored for the darker-hued instruments of the orchestra; it is at times dissonant, unsettled, always searching. The soprano and baritone soloists (superb Kate Royal and Roderick Williams) overlay the chorus’s restless motion with a question and answer dialogue, words of Leonardo. There is linguistic contrast, in this movement and later in the Requiem, bringing the Latin and English together.

The second movement for soprano soloist introduces a sharper edge to the work and is more lightly scored with its downward sliding strings. I found an unusual but apt text by Dante Gabriel Rossetti for this entitled, For “Our Lady of the Rocks,” by Leonardo da Vinci. Rossetti wrote the poem seated in front of the painting in the National Gallery and focused on the darker implications in Leonardo’s painting; “Mother, is this the darkness of the end, the Shadow of Death? And is that outer sea Infinite, imminent Eternity?” Rossetti wrote the poem in 1848, a year of revolutions and turbulence in Europe.

Leonardo was commissioned to paint the Virgin of the Rocks, which so inspired Rossetti, in 1485 by a church in Milan. Milan, at that time, was in the grip of the bubonic plague. (On 16 March, in the same year, there was a total eclipse of the sun which was ominously interpreted from pulpits everywhere in Milan . . . one can imagine the rhetoric!). The painting may have been an invocation against the ravages of the plague at that time. The texture of this movement, I hope, gives an acerbic darkness to the drama of the poem.

Image credit: Cecilia McDowall by Karina Lyburn. Used with permission.

Image credit: Cecilia McDowall by Karina Lyburn. Used with permission.The third movement for chorus alone, the Lacrimosa, “I obey thee, O Lord? is less dark and unashamedly melodic giving prominence to the oboe. Reflective in nature, it is another bringing together of the Leonardo text with the Latin mass.

The central part of the Da Vinci Requiem is held by the Sanctus and Benedictus which I hope conveys a sense of joy in amongst the more contemplative passages of the work. Trumpets and drums bring an energy and rhythmic vigour here and are set in contrast with descending choral lines accompanied by the bell-like glockenspiel.

The Agnus Dei for chorus and soprano solo is supported by sombre lower wind, brass and strings. In the sixth movement, for baritone solo, the text is entirely Leonardo’s in which he draws parallels between sleep and death.

The chorus and soloists all come together in the final movement of the work, the “Lux Aeterna.” Light, bright, luminous, the Leonardo text focuses on flight: “Once you have tasted flight, you will forever walk the earth with your eyes turned skyward….” In the closing bars all voices drift upwards, folding into silence, an allusion to Leonardo’s concept of The Perspective of Disappearance (La Prospettiva de’ perdimenti). It has been a fascinating exploration, aligning Leonardo’s extraordinary insights, both artistic and philosophical, with such a profound and ancient text.

Featured image credit : Old Man with Water Studies, a drawing by Leonardo da Vinci. Public domain via Wikipedia Commons.

The post Exploring the Da Vinci Requiem appeared first on OUPblog.

April 30, 2019

Gardens and cultural memory

Most gardens are in predictable places and are organised in predictable ways. On entering an English suburban garden, for example, one expects to see a lawn bordered by hedges and flowerbeds, a hard surface with a table for eating al fresco on England’s two days of summer, and a water feature quietly burbling in a corner. In warmer places, such gardens are not necessarily expected yet are still there. Some years ago I happened to be passing through the Iranian city of Abadan, at the southern end of the Iran-Iraq border. It is one of the hottest populated places on the planet, and in 1964 a heat burst raised the temperature to a record-breaking 87°C (189°F). During the Iran-Iraq war the city was shelled, bombed, and burnt. Gardening was not a high priority. When I travelled through the town on a warm winter’s day, my bus was diverted because of construction, and I found myself in a residential area inhabited decades ago by British employees of the Anglo-Persian Oil Company. The houses are now occupied by Iranians, some of whom have maintained English gardens. I saw one man clipping his hedge, and another pruning roses.

Such English gardens are memories of affirmations of identity and of memories of England, and they are to be found in many places far from England. I have visited an English cottage garden on an island off West Falkland. In Pakistan, the former colonial hill-town of Murree (apparently named after the Blessed Virgin Murree, known in the Islamic world as Maryam, who is said to be buried there) is planted with English trees (maple, oak, and pine), and some of the houses have lawned gardens. Similarly, the road leading from Dehradun up to the Indian hill station of Mussoorie takes one past a house that one would not be surprised to find in Surrey. A plaque on the gate announces it as the residence of a British colonel-of-foot; I imagine his moustachioed ghost tending the flowers in the garden.

Perhaps the gardens most clearly focussed on cultural memory are reconstructions, some of which are attempts to recreate the gardens of a particular year. The recreation of the garden at Kenilworth Castle in Warwickshire aspires to how the garden was in 1575, when Queen Elizabeth visited, and the zenith of the garden’s history. Similarly, the recreation of George Washington’s garden at Mount Vernon attempts to show its appearance in 1799, the year that Washington’s death suspended the garden in time.

In Japan and China, many gardens gesture towards the remote origins of distinguished ancient civilisations. In Japan, the folk beliefs and ritual practices eventually known collectively as Shinto centred on the spirituality of the natural world, and shrines erected at sacred outcrops and groves were surrounded by gardens consisting of white sand and small stones, which seemed to signify ritual purity. Japanese gardens have evolved over the intervening centuries, but still retain this animistic spirituality, and sand and stones appear in the most contemporary of designs. Similarly, there is an aesthetic of rocks (shared with the gardens of China and Korea), which are valued for their sculptural qualities. Rocks in ponds or dry landscapes often represent the legendary gardens of the immortals, and thus have a richness for Asian visitors that baffles innocent Westerners. In the West, gardens are centred on horticulture, so an Asian garden centred on stones comes as something of a shock.

Gardens often surprise the visitor, and sometimes we are left grasping for explanations. The floating islands of Lake Titicaca, in Peru, are constructed from totora reeds harvested from the lake; the same reeds are also used for the houses and boats used by the Uru people who live on the islands. In this botanical monoculture, it is surprising to see small decorative gardens planted with shrubs and flowers native to much lower altitudes. Do such gardens represent a memory of the land? My command of Aymara was insufficient to ask the question.

Featured image: A cottage garden, West Falkland. Photo by Mary Campbell. Used with permission.

The post Gardens and cultural memory appeared first on OUPblog.

Writing about jazz in the post-modern gig era

How should music reference works deal with jazz in the era of multi-genre freelancing? Back in November 1983, when I asked Stanley Sadie, series editor for Grove Dictionaries of Music, if he’d ever thought of having a New Grove Dictionary of Jazz, jazz seemed to be a reasonably coherent genre with a connected succession of styles. Maybe I was just being young, naive, ignorant. Or maybe the notion of jazz as something coherent hadn’t yet started to completely unravel, even though all sorts of challenges were nipping at it, especially as the fusions emerged (jazz-rock, jazz-funk, and so forth).

Stylistically, there seemed to be a strong continuity and overlap in the changes taking place over time: New Orleans jazz and Dixieland jazz emerging from blues and ragtime; a transition to virtuosic improvising soloists playing in swing and, later, bebop styles; most of these same musicians becoming involved in big-bands, when jazz temporarily became America’s popular music; a growing boredom with bebop, leading to explorations of alternatives in modal jazz and avant garde jazz; and then fusion, the melding of techniques of jazz improvisation with rock or soul rhythms. This was the conventional narrative. At the time, it made sense to regard jazz as a discreetly approachable scholarly entity.

A decade later it was becoming clear that these labels, while remaining very useful for describing longstanding jazz careers, were losing their usefulness for understanding what was going on within new developments in jazz. More than anything, I remember thinking, when Bill Frisell’s country music Nashville CD was named Down Beat magazine’s jazz album of the year, “Okay. That’s it. I give up.”

As the century ended, I noted that it was getting harder and harder to write a jazz reference biography that did not devolve into a boring shopping list: he or she performed with A, B, C, D, E, F, G, and recorded with T, U, V, W, X, Y, Z. The reason were obvious. We were approaching a half century from the time when live jazz flourished in nightclubs. People were going to clubs for rock and roll, rock, soul, disco, hip-hop. Jazz clubs hadn’t disappeared, but they were greatly diminished in quantity and importance, and no longer supported careers. As stressful and demeaning as extended nightclub residencies had been (low money, long hours, miserable racist experiences, and celebrations of addiction, not to mention the out-of-tune pianos), these residencies had nonetheless offered stability, an opportunity for a jazz group to develop and refine a personalized repertory, and consequently a reasonable signpost upon which we reference writers could hang a career. Now, as the century ended, even the greatest jazz musicians were cobbling together careers, traveling incessantly from festival to brief club date to university workshop.

Image Credit: John Zorn at the 2014 Newport Jazz Festival, August 1, 2014. digboston, CC BY 2.0 via

Wikimedia Commons

.

Image Credit: John Zorn at the 2014 Newport Jazz Festival, August 1, 2014. digboston, CC BY 2.0 via

Wikimedia Commons

.All this continues in the 21st century. Of course it’s not just jazz. When my wife and I heard Yefim Bronfman at Tanglewood in the summer of 2018, we were wondering how old he was. I looked on his website and happened to notice that Tanglewood was not in his biography for the concert season 2018-2019. How could that be? What was he doing that was so important that Tanglewood didn’t even deserve a mention? Clicking on the “Schedule” tab, I discovered that during this year he was giving 110 concerts in 70 different venues, worldwide. Tanglewood, eh? It didn’t matter. Life as a concert soloist was an ever-expanding list.

But for jazz, the problem intensifies, because in addition to the endless freelancing, many musicians are enjoying a post-modern approach to creation. Jazz is no longer conceived of as a coherent genre, and it has increasingly come to be understood as a process, a method of performance practice that might operate upon all kinds of music, whether popular, ethnic, classical, whatever.

I wouldn’t throw away notions of genre and style. Labels are useful for identifying sound types. If I say “bebop” or “big-band swing,” most of you will have some idea of the nature of those sounds. But jazz, as a methodology, a performance practice, has developed far beyond notions of genre and style. In the late 1990s, we were already struggling with this. Saxophonist John Zorn and his colleagues in the Manhattan Knitting Factory circle were putting out a bunch of CDs on the Tzadik label that had, we thought, more to do with Jewish music than with jazz. Pianist Uri Caine was improvising on the music of Gustav Mahler. Winston “Mankunku” Ngozi was melding a John Coltrane-influenced tenor sax style together with South African township music. In universities and conservatories, super-talented aspiring young musicians were more likely to be involved in exploring “contemporary improvisation” (which may or may not involve jazz styles or practices) than in a specific jazz improvisation course.

Smooth jazz exploded in popularity. To my ear, it could much more accurately (if more awkwardly) have been called instrumental rhythm-and-blues, or instrumental soul (i.e., R&B/soul without singing/lyrics). But smooth jazz was a sexy label, great for commodifying the music; it was a reasonably coherent stylistic label, and I didn’t really mind if someone wanted to regard it as belonging to the genre Jazz. In a different vein, during these years I was asked to write previews of the Dubai Jazz Festival for the Dubai edition of London’s Time Out magazine, only to discover that all but one of the performers played music that I would never call jazz. It was a blues, funk, and pop festival. The word “jazz,” commodified, had lost all relationship to genre and style.

Today there’s way more diversification than ever before, in applying notions of jazz to music. Frisell’s Nashville was the harbinger, or maybe the tipping point. What it represents has become the norm. Should there be a third edition of The New Grove Dictionary of Jazz? Probably not. Jazz coverage, such as it is, now belongs in a general dictionary of music and musicians. Current-day jazz careers have fragmented into a disconnected succession of gigs and recordings (a shopping list), and anyway, most professionals are involved in multi-genre explorations of worldwide music that shouldn’t be confined to a jazz box.

Featured Image credit: “Jazz club sign, Fisciano, Italy” by Pietro Battistoni. CC0 via Unsplash .

The post Writing about jazz in the post-modern gig era appeared first on OUPblog.

April 29, 2019

How Rabindranath Tagore reshaped Indian philosophy and literature

This April, the OUP Philosophy team honours Rabindranath Tagore as its Philosopher of the Month. Tagore (1861-1941) was a highly prolific Indian poet, philosopher, writer, and educator who wrote novels, essays, plays, and poetic works in colloquial Bengali. He was a key figure of the Bengal Renaissance, a cultural nationalist movement in the city. Born in Calcutta in 1861 into a distinguished, intellectual and artistic family that played an important part in the economic and social activities of Bengal, he was the son of Debendranath Tagore, an important Hindu religious leader and a mystic.

Tagore pioneered the use of colloquial Bengali instead of archaic literary idiom for verses in his first poetic collection Manasi (1890), in a philosophical and symbolic play Chitra (1895), and the lyric collection, Sonar Tari (1895). By the turn of the 20th century, at the age of 40, he had become a household name. In 1913, he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature for his English version of his celebrated poetic collection, Gitanjali, which is a free verse recreation of his Bengal poems modelled on medieval Indian devotional lyrics.

Tagore also helped to shape the development of Indian philosophy in the early 20th century. His philosophical works have religious and ethical themes. His best-known philosophical writing is The Religion of Man, based on the Hibbert Lectures he delivered at Manchester College, Oxford, in May, 1930, which contains his reflections on the spirit of religion and explores the themes of spirituality, God, the divine experience, and humanity. His body of literary works also expresses universal humanism, in particular his sympathy for the lives of women and the poor people of Bengali. His view about nature was also closely aligned with the philosophical aspects of the Hindu tradition in which nature is seen as a manifestation of the divine. His verse about the natural world expresses a sense of wonder and a human longing to be with the divine. Apart from this love of nature and humanity, he believed that the highest religion of man is to try to enhance creativity, which is “the surplus in man.”

Tagore was also a social critic and an educator. He rejected the mechanical, formal system of learning in favour of a curriculum that encouraged creativity, imagination, and moral awareness in students. His philosophy of education incorporated the synthesis of nationalist tradition, Western and Eastern strands of philosophy, science and rationality, and an international cosmopolitan outlook. In 1901, he established a school at Santineketan, Bolpur, which he later developed into an international institution, Visva-Bharati, based on his education principles.

As a close friend of Mahatma Gāndhī, who called him the “Great Sentinel” of modern India, Tagore opposed British rule and initially had an influence on the Indian nationalist movement. However, Tagore later embraced a humanist inter-nationalism, preferring instead to harmonize eastern and Western world views. His critique of nationalism and its violence is expressed in his key philosophical essay, “Nationalism” in which he called for a spirit of cooperation and tolerance between nations.

To this day Tagore is regarded as a cultural icon for India, and a key figure for innovations and modernization of Bengali literature and his formative influence on many modern Indian artists.

Featured Image: taj-mahal-india-agra-temple-tomb by Simon. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post How Rabindranath Tagore reshaped Indian philosophy and literature appeared first on OUPblog.

Racist jokes may be worse than racist statements

Jane Austen’s Emma Woodhouse tells her father, “Mr. Knightley loves to find fault with me, you know—in a joke—it is all a joke.” Mr. Knightley isn’t joking, as he and Emma know; he presents his criticisms without a hint of jocularity. But if Emma persuades Mr. Woodhouse to believe Mr. Knightley is joking, he “would not suspect such a circumstance as her not being thought perfect by everyone.” A little over 200 years after Emma was published, the comedian Roseanne Barr defended a racist tweet about Valerie Jarrett, President Obama’s former adviser, in a further tweet, “It’s a joke—”.

It’s probably not often that Austen and Barr belong in the same paragraph, yet despite the cultural differences between Regency England and 21st century America, both trade on a similar idea, that we don’t really mean what we say in jest, and thus we can say things jokingly that we should not say seriously. Both consider jokes to belong in a significantly different communicative category than statements or assertions. Emma’s thought is that if Mr. Woodhouse believes Mr. Knightley is joking, Mr. Woodhouse will think there is no truth to what he says; and Barr’s thought is that if she is joking, she does less—perhaps no—harm.

The idea that we can say things jokingly that we should not say seriously explains why people who would not stoop to a racist or sexist statement might make a racist and sexist joke, as the comedian Trevor Noah, born in South Africa under apartheid and himself of mixed race, did about Australian Aborigine women. It also explains why people often defend racist, sexist, and other derogatory comments as misguided attempts at humor. In addition to Barr’s non-apology, recall Don Imus’s initially half-hearted repentance for calling the members of a women’s basketball team “nappy-headed ho’s” during his radio show—it was “meant to be amusing.” Austen, Barr and Imus are right that jokes do not operate in the same way as assertions, but I believe that they, and many of us, are quite wrong about the communicative functions and effects of jokes.

The philosopher of language J.L. Austin pointed out that different kinds of speech are governed by different norms. To draw on Austin’s examples, I should not bet you five dollars unless I will give you the money if I lose, and I should not pronounce you married if I am not licensed to perform weddings. But I can bet you five dollars even if I am not licensed to perform weddings, since being licensed to marry someone isn’t a norm that governs wagers.

Austin argued that for some kinds of speech the norms include what we might call a responsibility to the facts. An antiques appraiser should not appraise your antique table for $5 000 if she thinks it will fetch $500, or $500 000, at auction; a judge should not declare you guilty in a criminal court if it is apparent that you did not commit the crime. But not all speech is responsible to the facts. For example, telling a bedtime story is not responsible to the facts, nor is naming a dog you save from an animal shelter. It doesn’t matter if the events in the bedtime story never happened, or if the dog’s previous owner had given it another name.

Jane Austen sees that joking speech is not responsible to the facts. Thus it can be acceptable to express something you believe to be false in a joke.

Jane Austen sees that joking speech is not responsible to the facts. Thus it can be acceptable to express something you believe to be false in a joke. But seriously saying something you believe to be false is largely condemned. We call that lying, and it is permissible only in special circumstances, such as when assuring a new parent that his slightly squished newborn is beautiful. The main norm covering joking, however, is that the joke be funny. There are other norms covering jokes as well, of course—e.g., I shouldn’t joke on learning that you have been bereaved. But because jokes do not have a responsibility to the facts, it can be socially acceptable to say something jokingly that would be hurtful if said seriously; if Mr. Knightley’s criticisms are successfully passed off as a joke, Mr. Woodhouse will not be hurt.

Since jokes have no responsibility to the facts, people sometimes use jokes to express something that it would be unacceptable to express seriously. We can use humor to express a painful or uncomfortable truth, and indeed doing so is sometimes recommended for defusing tense conversations. But people can also exploit the disconnect between jokes and the facts to express pernicious untruths, such as harmful stereotypes about race and gender. This, arguably, is what Barr and Imus did. They expressed racist untruths; and when they were upbraided, they claimed they were using a kind of speech that is not responsible to the facts, pointing towards the conclusion that since they did not mean it seriously, they did not mean it all.

However, to joke about a racial stereotype may be worse than saying it outright. In one study, the social psychologist Thomas E. Ford asked subjects to read either sexist statements or sexist jokes, and then to evaluate a situation in which a young woman at work is patronized by her male supervisor. Those who had read sexist jokes were more tolerant of the supervisor’s sexism than those who had read sexist statements. The effect was limited to subjects who already had antagonistic attitudes and indignation towards women. But the fascinating thing, to my mind, is that in this study, jokes, but not statements, led people to express less savory aspects of their attitudes.

So what might a racist joke, like Barr’s comment, do? It might bring out the racist worst in some of us, instead of the enlightened, thoughtful, equality-oriented, best. And if that is the case, then the fact that it was a joke does not alleviate the offence. Rather, it compounds the offence, making it more harmful rather than less.

Featured image credit: “Musician, microphone” by Bogomil Mihaylov. Public domain via Unsplash.

The post Racist jokes may be worse than racist statements appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers