Oxford University Press's Blog, page 193

April 16, 2019

Will robots really take our jobs?

The fear of automation technology and its potential to displace a large portion of the global labor force is nearly ubiquitous. A 2018 survey from the Pew Research Center reports that almost 80 percent of respondents across 10 countries believe that robots and computers are likely to take over much of the work currently done by humans sometime in the next 50 years and this change will cause much more harm than good, including job loss and rising inequality.

A certain unease about technology is warranted as there is strong evidence that technological innovation causes some people to lose their jobs. However, there is no credible evidence that technological change – at any point in time – has led to a net decline in overall employment. Still, it’s only natural to wonder whether this time could be different.

Looking over the period from 1999 to 2009, our research shows that low-wage jobs that are intensive in routine cognitive tasks, such as cashiers, have been supplanted by automation. Nevertheless, the impact on individual low-wage workers affected by this change is surprisingly small. One reason for this small impact is that automation, while changing the composition of jobs, does not lead to a net decline in the total number of jobs. Moreover, since low-wage jobs have few skill requirements and the minimum wage acts as a wage floor, individual low-wage workers displaced from their jobs are able to transition into newly created jobs without much of a wage penalty.

How could the use of technology intended to replace certain low-wage jobs lead to offsetting employment growth in other types of jobs? One possible explanation has to do with the nature of low-wage automation. Automation often involves moving some tasks that were previously performed by an employee, such as scanning items at the cash register, onto the customer. As firms introduce these new technologies, they also have to create new jobs to help teach and oversee customer interaction with the technology. In the short-run, this employment growth could help offset the decline in jobs from automation. However, this offsetting employment growth is unlikely to persist over longer periods of time as customers adapt to the new technology.

Another potential explanation is that automation technology could ease what economists call a fixed input in production problem. For example, the area behind the counter at one’s favorite café is a fixed amount of space that is often crowded with workers both taking orders and making drinks. The end result can be long queues. During busy times, some people may choose to avoid the café altogether. However, the introduction of ordering kiosks or a smartphone based ordering app could eliminate the need for cashiers, freeing up precious space behind the counter, which the café could repurpose to increase its capacity to make drinks. As wait times fall, fewer people skip their coffee purchase and the café can profitably hire more baristas – offsetting the decline in cashiers. This could lead to employment growth that persists over longer time horizons.

In sum, the above analysis of low-wage automation implies that certain types of jobs are disappearing. However, this job loss may not be nearly as costly as believed by the general public because low-wage automation seems to also lead firms to create new, similar-paying jobs. That said, the source of this offsetting employment growth remains unclear and may not persist over longer time horizons – meaning that the cost of low-wage automation on individual workers could increase over time. Future inquiry into this important topic is warranted if we are to move past our longstanding and nearly universal fear of technology and better understand its impact on present-day labor markets.

Featured image credit: Robot arm technology by jarmoluk. Public domain via Pixabay .

The post Will robots really take our jobs? appeared first on OUPblog.

April 15, 2019

At least in Green Book, jazz is high art

I’m anxiously awaiting the release of Bolden, a film about the New Orleans cornettist Buddy Bolden (1888 – 1933) who may actually have invented jazz. But since Bolden will not be released until May, and since April is Jazz Appreciation Month, now is a good time to talk about the cultural capital that jazz has recently acquired, at least in that multiply honored film, Green Book. As is often the case when a film is honored lavishly, however, Green Book has run up against a backlash. If nothing else, critics have argued that the story of the friendship between the Italian American bouncer Tony Vallelonga (Viggo Mortensen) and the African American pianist Don Shirley (Mahershala Ali) melodramatically promotes white fantasies of reconciliation with black people. Vallelonga—known in the film’s goombah fantasies of outer-borough ethnicity as “Tony Lip”—is hired to chauffeur Shirley through the heart of the racist South on a concert tour in the early 1960s. After Tony deftly extracts Don from various life-threatening experiences, the two men come to understand and appreciate each other. A text at the end assures us that the real-life Tony and the real-life Don remained friends right up until they both died some fifty years later.

Some of this may be true, but we have since learned that the filmmakers had few if any conversations with Shirley’s family. Instead, they relied almost entirely on what Tony’s son said his father told him. For example, the Don Shirley of the film tells Tony that he and his brother are not on speaking terms. But Shirley’s relatives have said that Don was a regular visitor at his brother’s house. The real Don Shirley was extremely protective of his privacy, and rather than reveal himself during the long drives with Tony, he may have found it easier simply to declare that he was estranged from his family.

I remember Shirley’s ingenious piano concoctions from the 1960s, especially his hit record “Waterboy” with its bluesy inflections. So, early in Green Book, I was surprised when Tony turns on the car radio and Don reacts like a bemused aristocrat to Little Richard’s performance of “Lucille.” I expected him to declare in a British accent, “How curious.” Just as Tony appears to be the first person to introduce Don to fried chicken (also denied by the family), he is also the first to introduce Shirley to the felicities of black popular music. It’s as if Shirley only knew the high classical sounds that wafted up into his apartment on top of Carnegie Hall.

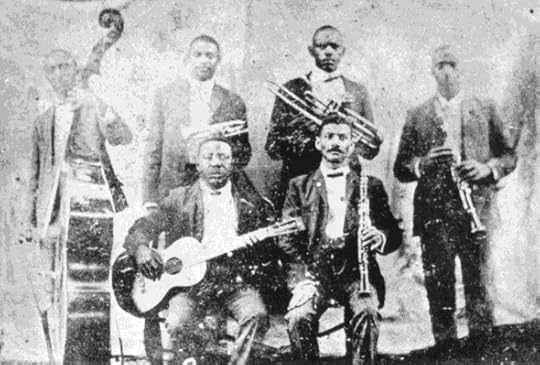

Buddy Bolden’s band, 1900-1906. (Bolden, second from left). Unknown photographer, from the personal collection of trombonist Willie Cornish, loaned for reproduction in book “Jazzmen” in 1938. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Buddy Bolden’s band, 1900-1906. (Bolden, second from left). Unknown photographer, from the personal collection of trombonist Willie Cornish, loaned for reproduction in book “Jazzmen” in 1938. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.But Don Shirley was well-acquainted with all kinds of African American music. He recorded several LPs devoted entirely to Negro spirituals, and he knew his way around a jazz groove. As a child prodigy, he studied classical music in Russia and made his debut at age eighteen with the Boston Pops. Shirley soon learned, however, that he was the wrong color to pursue a career as a concert pianist, eventually taking the advice of impresario Sol Hurok and building his career playing popular music.

What I find most intriguing about Green Book is the high-art cachet it gives to jazz. By suggesting that Don Shirley knew nothing about black popular music, the film separates jazz from vernacular music and places it in the same category as classical music. Indeed, in his performances—and even in Green Book—Shirley would regularly begin a number with gestures toward the classical repertoire before moving seamlessly into jazz and blues. Significantly, in concert, Shirley wore a tuxedo, as did the cellist and the bassist who appeared with him.

Shirley’s recordings reveal that he was no improvisor. Everything was carefully worked out ahead of time. There is, however, no mistaking his rhythmic authority and his mastery of the jazz idiom. Appropriately, the film ends with Shirley, still in his tuxedo, triumphantly sitting in with a group of black jazz musicians at a roadhouse (with the encouragement of Tony, of course).

Green Book has to avoid any mention of the spirituals that Shirley studied and performed. That would mean he knew the African American vernacular, and it would ruin the film’s absurd but crowd-pleasing notion that Tony helped a black man get in touch with his roots. The only one of Shirley’s many records the film acknowledges is “Orpheus in the Underworld” with its double allusion to the classical.

The film’s careful separation of musical genres suggests that whatever Shirley plays must be art music. Little Richard’s “Lucille” is definitely not art, but a jazz-inflected version of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s “Happy Talk” is, especially when played by Shirley.

It’s been almost one hundred years since demure Americans could be scandalized by jazz. Decades later, in Jailhouse Rock (1957), Elvis Presley attends a party where college professors and their wives discuss “altered chords” and “dissonance” in contemporary jazz. When a well-dressed woman asks Elvis’s character if he agrees that “atonality is just a passing phase in jazz music,” he replies, “Lady, I don’t know what the hell you talkin’ about.” At least in 1957, jazz belonged to the professorate. This was, of course, a few years before John Coltrane, Archie Shepp, Charles Mingus, and other avant-gardists played what some considered obstreperous protest music. But many of us never stopped believing that jazz was serious music.

Professors have been teaching jazz for some time now, but I would like to think that jazz still has powerful connections with the popular as well as the classical. There are many problems with Green Book, but to its credit, the film does not demean any of the music that Don Shirley plays. Even the film’s stereotypical working-class Italian Americans are fine with it. Lovers of both jazz and classical music should take heart, I suppose.

Featured Image credit: Piano Keys by Joshua Hoehne/@mrthetrain. CC0 via Unsplash.

The post At least in Green Book, jazz is high art appeared first on OUPblog.

April 14, 2019

12 of the most important books for women in philosophy

To celebrate women’s enormous contributions to philosophy, here is a reading list of books that explore recent feminist philosophy and women philosophers. Despite their apparent invisibility in the field in the past, women have been practising philosophers for centuries. Some of the great social and cultural movements have also been enriched by the female minds and their indefatigable efforts. Explore books on feminist philosophy, gender oppression, and women’s empowerment by female authors who approach pressing issues with analytical clarity and insight. Learn more about the classic female philosophers and their legacies.

Categories We Live By: The Construction of Sex, Gender, Race, and Other Social Categories, by Ásta

Asta examines the concept of social categories, which frame our identity, action, and opportunities. The main idea she draws on in her book is that social categories are conferred upon people. She illuminates what these categories are, and how they are created and sustained, demonstrating how these can be oppressive through examples from current event.

Unmuted: Conversations on Prejudice, Oppression, and Social Justice, by Myisha Cherry

Unmuted: Conversations on Prejudice, Oppression, and Social Justice, by Myisha Cherry

This book collects lively, diverse and engaging interviews of philosophers working on contemporary social and political issues from Myisha Cherry’s podcast Unmute. The interviews address some of the pressing issues of our day, including social protests, Black Lives Matter, climate change, education, integration, LGBTQ issues, and the #MeToo movement. Cherry asks the philosophers to talks about their ideas in accessible ways that non-philosophers can understand.

Sophie de Grouchy’s Letters on Sympathy: A Critical Engagement with Adam Smith’s The Theory of Moral Sentiments, by Sophie de Grouchy, Edited and translated by Sandrine Bergès, and Eric Schliesser

This is a new translation of a text by a largely forgotten female philosopher, Sophie de Grouchy (1764-1822),whose profound contributions anticipated the work of later political philosophers. Grouchy published her Letters on Sympathy in 1798 together with her French translation of Smith’s The Theory of Moral Sentiments. Although the former is a response to Smith’s analysis of sympathy, it is an important philosophical work in its own right and offers an insight into Enlightenment and feminist thought, and the early Republican theory.

Equal Citizenship: A Feminist Political Liberalism, by Christie Hartley and Lori Watson

This book is a defense of political liberalism as a feminist liberalism. It argues that political liberalism’s core commitments restrict all reasonable conceptions of justice to those that secure genuine, substantive equality for women and other marginalized groups. It also looks at how the philosophic idea of public reason can be used to support law and policy needed to address historical sites of women’s subordination in order to advance equality.

Resisting Reality: Social Construction and Social Critique, by Sally Haslanger

Sally Haslanger is an acclaimed feminist philosopher in the field of feminist theory and epistemology. This book collects Haslanger’s essays on the concept of social constructions and offers a critical realist account of gender and race. It develops the idea that gender and race are positions within a structure of social relations. It argues that by theorising how gender and race fit within different structures of social relations, we are better able to identify and fight against oppression and forms of systematic injustice.

Learning from My Daughter: The Value and Care of Disabled Minds, by Eva Feder Kittay

Eva Feder Kittay is an award-winning philosopher and a mother who has raised a multiply-disabled daughter. Through personal narrative and philosophical argumentation, she relates how parenting a disabled child altered her views on what truly matters and gives meaning in life. She addresses difficult questions such as the desire for normality, reproductive technology’s promise that we can choose our children, the importance of care, and the need for an ethic of care.

Down Girl: The Logic of Misogyny, by Kate Manne

In this ground-breaking work, the feminist philosopher Kate Manne analyses what misogyny is, how it works in contemporary culture and politics, and how to fight it. She argues that misogyny should not be understood primarily in terms of the hatred or hostility some men feel towards women. Instead, it is about controlling and punishing women who challenge male dominance while rewarding those women who reinforce the status quo. The book refers to iconic and modern-day events such as the Isla Vista killings in May 2014 and Australian Prime Minister Julia Gillard’s misogyny speech in October 2012, showing how these events, among others, set the stage for the 2016 US presidential election.

Pornography: A Philosophical Introduction, by Mari Mikkola

Debates concerning pornography tend to be heated and problematic. What is pornography? Is there a fundamental right to access and consume pornography? Does pornography undermine women’s civil rights and equal status as citizens? Can there be a genuinely feminist pro-pornography stance? Mari Mikkola provides an accessible introduction to the philosophical examination of the hotly debated questions related to pornography conducted from a feminist perspective. She approaches pornography from numerous debates and philosophical perspectives including ethics, aesthetics, feminist philosophy, political philosophy, epistemology, and social ontology.

Simone de Beauvoir: The Making of an Intellectual Woman, by Toril Moi

This landmark study focuses on the life of Simone de Beauvoir, one of the most iconic female philosophers of the twentieth century. Through her analysis, Toril Moi showed how Simone de Beauvoir became the leading feminist thinker of the twentieth century, uncovering also the conflicts and difficulties that she faced as an intellectual woman in the middle of the twentieth century. It incorporates biography with literary criticism, feminist theory, and historical and social analysis, to fully explore her life in philosophy.

This landmark study focuses on the life of Simone de Beauvoir, one of the most iconic female philosophers of the twentieth century. Through her analysis, Toril Moi showed how Simone de Beauvoir became the leading feminist thinker of the twentieth century, uncovering also the conflicts and difficulties that she faced as an intellectual woman in the middle of the twentieth century. It incorporates biography with literary criticism, feminist theory, and historical and social analysis, to fully explore her life in philosophy.

The Monarchy of Fear: A Philosopher Looks at Our Political Crisis, by Martha Nuusbaum

Martha Nussbaum is a renowned moral philosopher. In The Monarchy of Fear she turns her attention to the current political crisis that has polarized America since the 2016 election. She focuses on the emotions of fear, anger, disgust, and envy. Drawing on a mix of historical and contemporary examples, from classical Athens to the musical Hamilton, The Monarchy of Fear untangles this web of feelings and provides a roadmap of where to go next.

The Confucian Four Books for Women: A New Translation of the Nü Shishu and the Commentary of Wang Xiang, translated with introductions and notes by Ann A. Pang-White

This is the first complete English translation of the Confucian Four Books for Women, which written by female scholars for women’s education and spanned the 1st to the 16th centuries. It incorporates Ban Zhao’s Lessons for Women, Song Ruoxin’s and Song Ruozhao’s Analects for Women, Empress Renxiaowen’s Teachings for the Inner Court, and Madame Liu’s (Chaste Widow Wang’s) Short Records of Models for Women. These works reveal the history and development of Chinese Women’s writing, education, and philosophical discourse over the period of 1,600 years.

Differences: Rereading Beauvoir and Irigaray, Edited by Emily Anne Parker and Anne van Leeuwen

Simone de Beauvoir and Luce Irigaray have a lot in common; both were French philosophers and theorists, whose works took off around the middle of the century. However, both women insisted on their ideological differences, which have largely guided the reception of their works. This edited volume, with works from scholars in French philosophy and existentialism, delves into the commonalities of Beauvoir and Irigaray’s works from a historic and contemporary feminist perspective.

The above reading list is by no mean an exhaustive one. These works give insight into women’s philosophical discourse and the evolution of feminist thought. Women produce ground-breaking works across all the fields of philosophy and it is important to recognize the value and the original and fresh perspectives they bring at such a divisive time.

Featured Image:Photo by Aliis Sinisalu on Unsplash

The post 12 of the most important books for women in philosophy appeared first on OUPblog.

Is it right to use intuition as evidence?

Dr. Smith is a wartime medic. Five injured soldiers are in critical need of organ transplants: one needs a heart, two need kidneys, and two need lungs. A sixth soldier has come in complaining of a toothache. Reasoning that it’s better that five people should live than one, Smith knocks out the sixth soldier with anesthetic, chops up his organs, and transplants them into his five other patients. In the chaos of the war, no one ever finds out. Does Smith act wrongly?

It seems to me that Smith has done something wrong. This feeling of mine is not the conclusion of any explicit argument. Instead, I just reflect on this situation and find myself with the intuition that Smith’s act is wrong. On this basis, I conclude that morality does not always require us to bring about the best outcome. It is better for five to survive than one, but it’s not permissible to murder someone to bring this outcome about.

Here, I use my intuition as evidence for a philosophical claim. I start with a claim about how things seem to me, intuitively, and I move from there to a claim about how things actually are. This is one of the primary ways in which philosophers answer questions about reality and our place in it—we think carefully about hypothetical scenarios or abstract principles, and see what claims then seem to us to be true about whether an action is immoral, or when our actions are free, or what we can know.

Or at least, this is the received view about philosophical methodology. In recent years, a number of philosophers—including Timothy Williamson, Herman Cappelen, Max Deutsch, and Jonathan Ichikawa—have challenged this view. It’s not that they think that intuitions aren’t good reasons for philosophical beliefs. They think that we don’t use intuitions as reasons for philosophical beliefs in the first place. These philosophers maintain that in a case like the above, I don’t treat my intuition that Smith has acted wrongly as evidence that morality doesn’t require bringing about the best outcome—instead, I treat the fact that Smith has acted wrongly as evidence for this claim. To think that we use facts about our mind, rather than facts about the world, as evidence is to wrongly psychologize our reasoning.

I think these critics are wrong. Many aspects of philosophical reasoning only make sense if they involve using intuitions as evidence. For example, this is the easiest way to explain the fact that in the above example, my intuition and my belief coincide: I have an intuition that Smith acts wrongly, and I also believe this. While philosophers sometimes reject their intuitions, this is the exception rather than the rule: most of the time, we act as if we expect our intuitions to be a guide to the truth.

Many aspects of philosophical reasoning only make sense if they involve using intuitions as evidence.

When philosophers don’t go along with their or others’ intuitions, they often offer error theories for those intuitions. These error theories are supposed to explain away intuitions contrary to their own beliefs. A philosopher intent on maintaining that morality requires bringing about the best consequences might try to explain away my intuition to the contrary by arguing that while Smith’s action was right, in most similar cases, there would be very bad consequences to doctors killing patients to harvest their organs (for example, if this became common, people would stop going to their doctors). The reason it seems to me that Smith acts wrongly is because I am confusing Smith’s situation with these other similar situations in which organ harvesting would be wrong.

The practice of offering error theories only makes sense if we think intuitions are evidence. In offering the error theory above, this hypothetical philosopher is tacitly acknowledging that my intuition would be evidence for my belief, were this contrary explanation of my intuition not available. If we could not explain my intuition by my confusing Smith’s action with similar actions, the best explanation of my intuition would be that it is based on perception of the actual moral qualities of Smith’s action—I believe that Smith acts wrongly because I have a moral sense that leads me to understand that in a situation like this, Smith’s action does not meet the demands of morality.

Why does it matter whether philosophers use intuitions as evidence? It matters because we want to make sure that we are reasoning responsibly. If we use intuitions as evidence, it is incumbent upon us to ask: are we right to do so? Are our intuitions about knowledge, free will, ethics, God, and so on, actually reliable guides to those subject matters? Are the ways things seem to us correlated with the ways things are? In answering these questions, we have to also take seriously the challenges of skeptics who purport to show that our intuitions are not reliable—whether because they are shaped by evolutionary pressures, biased by culture, or responsive to irrelevant factors, like the order in which different cases are presented. These skeptics might be right or they might be wrong. But the challenge they are raising is one that cannot be ignored, for the use of intuitions as evidence is central to philosophical practice.

Featured image credit: “Lost in the Wilderness” by Stijn Swinnen. CCO via Unsplash.

The post Is it right to use intuition as evidence? appeared first on OUPblog.

April 13, 2019

Harold Wilson’s resignation honours – why so controversial?

On February 6 Marcia Falkender, the Baroness Falkender, died. She was one of the late Prime Minister Harold Wilson’s closest and longest-serving colleagues, first as his personal then political secretary. An enigmatic figure, she has been variously reviled, mocked, and defended since the end of Wilson’s political career. Most notoriously she was connected to Wilson’s 1976 resignation honours list, the “Lavender List.”

Twice a year, every year, the British government publishes a list of people it has decided to honour. The honours list is probably best known outside of the United Kingdom as the way people get knighthoods, though the list includes various other orders, decorations and medals to recognize various types of service. In exceptional cases, such as royal anniversaries or political resignations, the government produces extra lists to recognize special service. Throughout the twentieth century the purpose and focus of these honours has evolved with changing political and social priorities. British honours represent both a judgment of merit and one about hierarchy. Today civil servants (who have been one of the main beneficiaries of the system) portray it as a politically neutral and organic expression of national worth that rewards good people, and whose most egregiously hierarchical, imperial, and political manifestations are consigned to the distant past. In this narrative, a few past scandals were moments of individual corruption rather than revelations of fundamental problems in the system. The Lavender List was one such moment when civil servants, the press, and politicians portrayed choices about whom the government would honour as a corrupt violation of normal practice.

Of all the parties involved the civil service usually exercised the most control over honours lists. One of the few types of honours that escaped this oversight, though, were those on prime ministerial resignation lists. By tradition, these lists offered outgoing prime ministers the opportunity to recognize people who had helped them personally. Advisers, drivers, detectives, and secretaries often filled out these lists.

Wilson’s 1976 resignation list looked different. The first draft included multiple appointments to high honours–knighthoods and life peerages–to businessmen who had limited connections to either Wilson or the Labour Party. Most were immigrants who had made it good in the UK. They included notorious financier James Goldsmith, raincoat manufacturer Joseph Kagan, show-business tycoon Lew Grade, and Grade’s brother, EMI executive Bernard Delfont. Wilson seems to have chosen men in whom he was interested or who impressed him in some way. While he did not know Goldsmith well, he was impressed that Goldsmith was suing Private Eye, a magazine Wilson and his wife disliked.

This first draft was quickly leaked, sparking controversy months before the list was confirmed. Civil servants, political allies, and, indirectly, political enemies alike put pressure on Wilson to remove or change many of the senior appointments on the list, including Goldsmith, who was removed.

Wilson resisted most of the pressure for change. The final list was greeted with derision by politicians and many in the press. Labour politicians objected to the presence of capitalist entrepreneurs with limited or no connections to their party. Conservatives sneered at Wilson’s choice of men who seemed more aligned with capitalist values. Other social conservatives sniffed at their foreign (and often Jewish) origins. Some treasury officials also knew that a couple of the men, including Kagan, were under investigation for financial crimes.

Many critics portrayed Falkender as holding power over Wilson beyond her role as his political secretary. Joe Haines, a long-serving member of Wilson’s political staff, coined the name “Lavender List” to support this idea by presenting the list as an intrusion on the corridors of power that was illegitimate because of its femininity. They derided Wilson for his supposed weakness to Falkender’s persuasion.

The main official criticism of the list came from the Political Honours Scrutiny Committee, a group of Privy Counselors led by civil servant, chess master, and former code breaker Philip Stuart Milner-Barry. The committee had been set up in the wake of the “sale of honours” scandal of the early 1920s. In effect, though, it laundered the sale of honours by parties by giving them an official stamp of approval. It censured the list precisely because there was no evidence of political donations to Labour on the part of the recipients. To the committee the lack of evidence for money changing hands for honours was proof of the list’s corruption because it was a break with the standard practices of party-sponsored honours sales.

Civil servants who were usually secretive about honours lists also leaked news of the undesirable names to the press. Men like Milner-Barry and Wilson staffers Haines and Bernard Donoghue attacked Falkender as unprofessional, but in hindsight their actions and responses look pettier, less discreet, and less professional than Falkender’s. For all that they drew on gendered notions of Falkender’s alleged feminine irrationality they were the ones leaking to the press, playing games, and, above all, furiously gossiping.

Wilson was already known for innovative honours. In 1965 his appointment of the four Beatles as MBEs (Members of the British Empire) had caused a minor controversy. He had also engineered an OBE (Officer of the British Empire) for cricketer and anti-apartheid symbol Basil D’Oliviera in 1969. The 1976 resignation list seemed to be a last gesture of defiance by Wilson at the system, and the scandal a last punishment by civil servants and other establishment figures for his attempts at innovation.

But the seeming violations of tradition in Wilson’s lists were to become normal in the 1980s and 1990s: popular culture celebrities, “ruthless” entrepreneurs, women Lords, and others from outside the traditional boundaries of the establishment. The political culture that derided Falkender’s influence was in for a surprise. Within three years, a woman would occupy Ten Downing Street not as secretary, but as prime minister. Wilson’s model of honours won out. Most of the controversial names on the Lavender List would look normal today.

Featured image credit: “Houses of Parliament” by PublicDomainPictures. Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Harold Wilson’s resignation honours – why so controversial? appeared first on OUPblog.

April 12, 2019

The Cambridge Philosophical Society

In 2019, the Cambridge Philosophical Society celebrates its 200th anniversary. When it was set up in 1819, Cambridge was not a place to do any kind of serious science. There were a few professors in scientific subjects but almost no proper laboratories or facilities. Students rarely attended lectures, and degrees were not awarded in the sciences. The Philosophical Society was Cambridge’s first scientific society. Within a few years of its foundation, it had begun hosting regular meetings, set up Cambridge’s most extensive scientific library, collected and curated Cambridge’s first museum of natural history, and begun publishing Cambridge’s first scientific periodical.

Over the last 200 years, countless new scientific discoveries have been presented at meetings and in the journals of the Philosophical Society. These are a few:

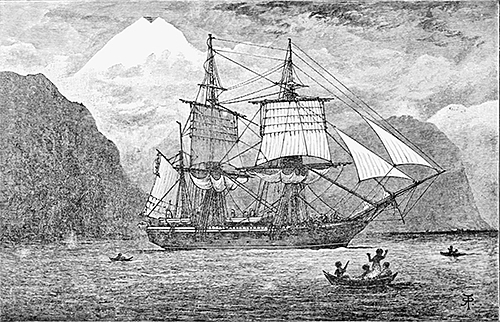

Darwin's Beagle letters

Darwin's Beagle letters Charles Darwin had studied at Cambridge from 1828 to 1831 then, wanting to pursue a scientific career but unsure of how to go about it, he accepted an offer to travel on HMS Beagle as it mapped the coastlines of South America. The fellows of the Philosophical Society were keen to send a Cambridge man on the voyage; “what a glorious opportunity this would be for forming collections for our museums” wrote one as he debated who to propose for the voyage. In the end, young Darwin was chosen and set off in December 1831. Darwin regularly wrote back to Cambridge from his travels, with many of his letters addressed to his old mentor John Stevens Henslow. Henslow had been one of the co-founders of the Philosophical Society and so excited was he about Darwin’s discoveries and observations in South America that he eagerly brought Darwin’s letters to meetings of the Society to be read aloud.

These readings were immensely popular, so much so that the Society published a booklet containing extracts from Darwin’s letters in the winter of 1835 – this was Darwin’s first scientific publication. Because Darwin was in the South Pacific Ocean at the time of publication he didn’t learn of it until many months later, and though he was initially alarmed not to have been consulted, he was ultimately gratified to hear how well the booklet had been received. He was particularly pleased when his sister reported that their father, who had had doubts about Charles’s decision to pursue a career in natural history, “did not move from his seat till he had read every word of your book … he liked so much the simple clear way you gave information.”

Image Credit: H.M.S. Beagle in Straits of Magellan by Robert Pritchett. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

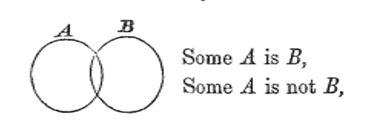

Venn Diagrams

Venn Diagrams The philosopher and logician John Venn is best remembered today for creating what we now call “Venn diagrams.” He first published a paper on these diagrams – he called them “Eulerian circles” – in July 1880 in a journal called The Philosophical Magazine. But Venn, who was a fellow of Caius College in Cambridge, often attended meetings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society, and so it was natural that his first talk on the circles was given at the Society. This was in December 1880 and it was the first time he showed these images to an audience. Initially, these diagrams were just used by logicians and mathematicians; today they are still used for these purposes, but have also become a staple of pop culture and internet memes.

Image Credit: John Venn’s “geometrical diagram for the sensible representation of logical propositions” from a talk he gave at Cambridge Philosophical Society, 6 December 1880. Used with permission.

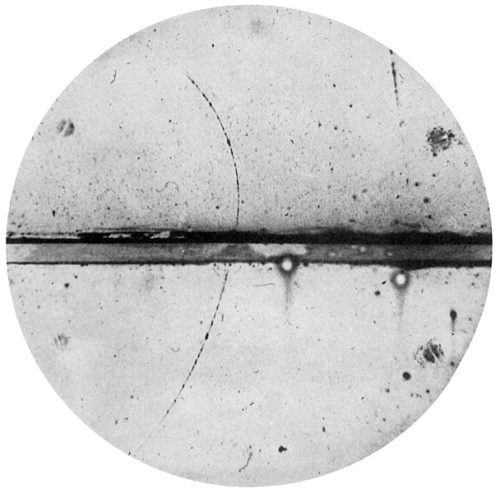

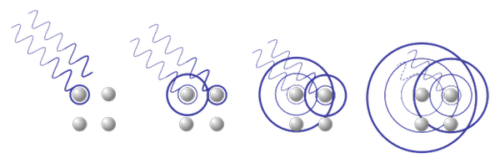

The Cloud Chamber

The Cloud Chamber In May 1895, a young researcher at Cambridge’s Cavendish Physics Laboratory gave his first talk at the Cambridge Philosophical Society. This young man, C.T.R. Wilson, was fascinated by meteorology and had just returned from a weather observatory on Ben Nevis where he had spent hours watching cloud formations as they moved and changed above the mountains. Back in Cambridge, he began to create artificial clouds in the laboratory, in a device he called “the cloud chamber.” It was this device he talked about at the meeting that May evening; it was the first time he had presented this work to colleagues.

Many researchers at the Cavendish then were studying x-rays and radioactivity, so Wilson had access to radioactive material and began to irradiate his clouds to see what happened. This was around the same time that the head of the laboratory – J.J. Thomson – discovered the first sub-atomic particle, the electron. Wilson and Thomson realized that by introducing electrons into Wilson’s artificial clouds, they could observe the water droplets that formed around the particles, and thus could work out their charge and mass.

Wilson’s cloud chamber, designed to study the weather, became one of the most important tools in understanding the secrets of the sub-atomic world, and Wilson and Thomson would both go on to win Nobel prizes for their work.

Image Credit: Cloud photograph of the first positron ever observed by Carl D. Anderson. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

X-ray diffraction

X-ray diffraction Lawrence Bragg was a young researcher at the Cavendish Laboratory when he presented his first ever scientific paper to the Cambridge Philosophical Society. He was just 22, and in fact his mentor J.J. Thomson read the paper for him as Bragg was so young. The paper discussed an experiment in which x-rays were aimed at a crystal, passed through the crystal, and then exited the crystal in a regular pattern that showed up as dots on a photographic plate. Others had tried to explain the regular nature of the pattern produced, but it was Bragg who successfully showed that the arrangement of dots was directly linked to the structure of atoms within the crystal: he had created a new way of “seeing” inside matter.

Other scientists immediately saw the importance of Bragg’s results. One of Bragg’s most ardent supporters was his father William Bragg who at once began working on the machine known as the x-ray spectrometer. The technique of x-ray diffraction would become one of the most important tools in twentieth-century science, and was most famously used to decode the structure of DNA.

Like Wilson, Lawrence Bragg was awarded a Nobel Prize for this piece of work first unveiled to the world at a meeting of the Cambridge Philosophical Society.

Image Credit: Diffraction of radiations by atoms by the.ever.kid. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The word "scientist"

The word "scientist" It’s well known that the word “scientist” was coined in Cambridge in 1833 by William Whewell (a founding member of the Cambridge Philosophical Society). But it’s less well known that it took place at a meeting arranged by the Cambridge Philosophical Society. In 1833, the British Association for the Advancement of Science met in Cambridge thanks to an invitation from the Society. The Society organised almost all aspects of the meeting, and parts of it were even held in the Society’s own house.

Many at the time were concerned about the terminology used to describe the people who did science. ‘Natural philosopher’ was a commonly used term, but Whewell considered it “too wide and too lofty;” the German natur-forscher was good, but did not lend itself to any elegant English translation; while the French word savans was “rather assuming” and too, well, French. Instead, Whewell proposed the word “scientist” as an analogy with “artist.” At the time, Whewell reported, his idea was not “generally palatable.” In Britain, it was rejected as being ugly and utilitarian. But over the course of the century, both the word and the concept of distinct scientific disciplines began to become more visible.

Doctor Research by mohamed_hassan. Pixabay License via Pixabay.

Featured image credit: “Cambridge-Architecture-Monument” by blizniak. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post The Cambridge Philosophical Society appeared first on OUPblog.

How industry can benefit from marine diversity

The global economy for products composed of biological materials is likely to grow 3.6% between now and 2025. This in response to serious environmental challenges the world will face. Such products have enormous potential to provide solutions to global challenges like food security, energy production, human health, and waste reduction. This economic growth may strongly benefit from organisms that come from the sea. For example, scientists estimate that marine microorganisms have 100-times higher potential for developing anti-tumour drugs than those on the ground, simply because of the higher natural biodiversity.

Today’s technology has enabled scientists to generate a spectacular vision of the marine microbial world. Industry uses these microbes and their products (chemicals and enzymes) because they can lead to lower production costs or get to market quickly. This is vital for compounds under price pressure such as fine chemicals and pharmaceutical compounds. For example, Yondelis is an anti-tumour agent derived from Caribbean sea squirt Ecteinascidia turbinate. Other examples include proteins Cpn10 and Cpn60, isolated from marine psychrophilic bacterium Oleispira antarctica, used to extract enzymes necessary for industrial processes like beer fermentation or the bleaching of paper products. However, few companies can undertake the costs and risks involved for this kind of research.

Oceans cover 71% of the Earth’s surface and are inhabited by about 2 million microorganisms. They have been evolving for at least 3.5 billion years. People have discovered only a tiny fraction of microorganisms in the ocean. This is simply because the ocean is so large. Scientists with experience in cultivation, isolation, and characterization of microorganisms know how much effort it takes to isolate a marine microorganism and how much time and resources it takes to discover, test, and commercialize a new product.

There are numerous steps to explore the ocean for marine microorganisms and their products. First researchers take an expedition to collect samples. Then scientists analyse these samples on board and in a laboratory. Once they identify a potentially useful microorganism or product, they have to find a way to enable mass production. Then there’s further testing to validate that the products perform as expected. Final steps include pre-clinic and clinical trials (if it is a drug), or industrial studies and tests (if an industrial product), before relevant boards can approve such products and bring them to market. These elaborate sorts of tests are not commonly done at laboratory scale because they require such a large investment of time or money. They are essential when researchers envision manufacturing marine products for commercial use, however.

The cost of a sampling expedition depends on the site explored, the number of researchers involved, and the cost of storage and transportation. Anyone could go to the beach and retrieve seawater for free. If one wants to access off-shore or deep sea resources, the project could cost €10,000 a day.

It would take around 1000 years to isolate all the marine microbial species that may exist.

The amount of time and resources also depend on which microbe scientists end up identifying. It would take around 1000 years to isolate all the marine microbial species that may exist. Researchers have been able to culture some bacteria successfully within a few months, but other strains can take years to isolate.

It would take about 15 years to discover, develop, and commercialize a marine-derived oncology drug for clinical applications, for instance. The total cost of this would be at least €800 million. Only 40% of drugs on the market generate sales to cover that sort of cost. In the case of enzymes companies might use for commercial products, this time frame is shorter, but still challenging.

Publicly funded research cruises and marine biodiscovery research projects, many supported by the EU’s successive research and innovation funding programmes, such as INMARE, contribute to novel and more efficient exploration of marine microbes. Such research projects also help scientists understand how to derive products from these microbes. These projects and initiatives can help meet the need for organic chemicals. The challenge is not just how to access and sample our ocean’s biodiversity; it’s also crucial to take advantage of that biodiversity and bring related products to market.

The post How industry can benefit from marine diversity appeared first on OUPblog.

April 11, 2019

National Women’s History Month: A Brief History

Every year, I teach a course on U.S. women’s history. Every year, I poll my students to find out how many of them encountered any kind of women’s history in their pre-college educations. They invariably say that they didn’t learn enough about women (this is a self-selecting group after all), but they also easily recite key components of U.S. women’s history: the Salem witch trials, Sojourner Truth, the nineteenth amendment, Rosie the Riveter, second-wave feminism, among others. These lists don’t capture the complexity of U.S. women’s history, but they represent a substantial and significant change over the past forty years.

In the 1970s, history classes barely talked about women. Even among historians and museum professionals, the question of women’s history as a respectable subfield was still very much open. When John Mack Faragher published Women and Men on the Overland Trail in 1979, one reviewer remarked that the “somewhat inverse title of this book is doubtless designed to arouse curiosity and boost sales.” For many historians, raised in a school of thought that emphasized the historical achievements of Great Men, women’s history seemed secondary and even frivolous. When Joan Wallach Scott asserted in the American History Review in 1986 that gender could be “a useful category of historical analysis,” her work represented a paradigm shift.

It was in this context that Women’s History Month was born. As the first generation of women’s historians fought for recognition in their profession, most were also engaged with feminist activism outside of the academy. They were among those who lobbied the United Nations to recognize International Women’s Day, which it did for the first time in 1974. The date – 8 March – had long been significant for socialist feminists, as the anniversary of Soviet women’s suffrage in 1917. In the 1960s, it took on broader meaning for diverse feminist groups around the world.

After the United Nations recognized 8 March as International Women’s Day, the date became the focal point for broader celebrations and observances, including local Women’s History Week festivities across the United States. In 1978, the Sonoma County school district organized such a successful Women’s History Week that it caught the attention of several leading feminist scholars.

Among these scholars was Gerda Lerner, a founding member of the National Organization for Women and the 1980-1981 president of the Organization of American Historians. Inspired by the Sonoma observance, Lerner and others moved to establish Women’s History Week celebrations in their own communities.

They also lobbied for federal recognition and achieved it with remarkable speed. In March of 1980, President Carter officially designated the week of 2–8 March, 1980 as Women’s History Week. His proclamation quoted Lerner and reiterated his support for the Equal Rights Amendment (which was then in the process of ratification, though it would ultimately fail). He also declared women’s history to be “an essential and indispensable heritage from which we can draw pride, comfort, courage, and long-range vision.” By 1987, feminist activists and congressional legislators expanded the celebration to encompass the whole month of March.

Now, every year, the president issues a new declaration designating March as National Women’s History Month, accompanied by a speech about the significance of women’s history. Across the country, museums, schools, libraries, community organizations, and media outlets take the opportunity to highlight women’s histories.

Even more significant, women’s history has gained broad recognition both within and outside of the academy. In many primary and secondary schools, women’s history has become a part of the curriculum. It is the subject of popular books, documentaries, miniseries, and museum exhibits – in some cases, whole museums!

It is also a vibrant field of study among professional historians, who have uncovered and continue to uncover diverse histories of women in virtually every place and era. In my own subfield, historians have turned their attention toward the histories of conservative women, many of whom strenuously opposed the same feminist activism that helped to establish women’s history as a legitimate pursuit. Though they may have disagreed with the feminist motivations of the field’s founders, they made undeniable political contributions that demand historical attention.

Of course, there is still more that can be done. There is more research to do and there are more stories to tell. We can do more to nuance and diversify public understandings of women’s history, and to continue to insist that these efforts matter. But as we close the door on one more National Women’s History Month, it is also worth looking back to see how far we’ve come.

Featured image credit: “Autumn at TEDS” by Andrew Seaman. CC0 via Unsplash.

The post National Women’s History Month: A Brief History appeared first on OUPblog.

Yes means yes: why verbal consent policies are ineffective

Communication around sex on college campuses tends to be poor in general—not only do students struggle to communicate and have hang-ups and fears about communicating, but hookup culture is one that privileges noncommunication. After all, what better way to signal a casual attitude toward your partner than to ignore him or her? Because students are often afraid to challenge these established norms—they fear rejection but also wider social implications—campus culture does not support open and mature communication about sex. At least, not yet. This, of course, does not mean that we should give up on teaching students to become better at communicating with their partners—we absolutely should teach verbal communication as central, even ideal, especially when it comes to hookups because the lack of a prior relationship makes other forms of communication unreliable. But without also attending to the peer culture in which students are immersed, we’re asking them to thwart established norms without really considering how difficult it can be to do this, and many students don’t have the necessary emotional and social courage. We’re setting them up to fail.

Verbal consent policies also assume that everyone knows exactly what they want in sexual situations, which, of course, is not always true. A sexual encounter can be a fact-finding mission with one’s partner, and it can result in a bevy of confusing feelings about one’s desires and interests. Learning to communicate better, and building intimacy and trust, can help a great deal toward talking through what is working, what isn’t, and where to go next. But again, on college campuses, the typical context for a first- time sexual encounter is a hookup where often there is no prior intimacy or trust. And we must acknowledge how college students already practice consent (or don’t).

Kristen Jozkowski of the University of Arkansas is the premier researcher in this area. Jozkowski has challenged the prevalence of policies that teach that true consent can be only verbal, arguing that such policies have been established by universities and the State of California without looking into the lived realities of how people actually negotiate consent. This failure to contend with reality can limit the effectiveness of these policies, especially because one’s ability to offer verbal consent is often influenced by gender and because our culture discourages young women from enthusiastic “yeses” altogether.

It is unrealistic to ask young people simply to change these scripts without first transforming the problematic culture that creates them. Only the hardiest of them can swim against such a strong current.

According to Jozkowski, in the sexual scripts that young women and men inherit, women are expected to refuse sex, and men are expected to verbally and physically push past women’s refusals. Women who give an enthusiastic “yes” run the risk of getting labeled sluts, while men are socialized to discount women’s “nos” as “token refusals” they need to turn into nonverbal acquiescence. To expect women to say “yes” enthusiastically, so that consent is crystal clear, is to ignore the power of these scripts. And it is unrealistic to ask young people simply to change these scripts without first transforming the problematic culture that creates them. Only the hardiest of them can swim against such a strong current.

Cultural biases work against women in the other direction as well. Short of a woman aggressively and forcefully exclaiming “No!,” men are expected to proceed as far as they can get. “When women are not aggressive in rejecting sex, not only are their partners likely to misunderstand their desires,” writes Jozkowski, “campus discourse may suggest that they did not do enough to ‘prevent the assault.’ This can lead to internalized self-blame, prevent reporting, and perpetuate rape culture.”

Scholars Melissa Burkett and Karine Hamilton agree with Jozkowski, and argue that while women should be empowered to say no or yes to sex, gender imbalances and inequalities exist in college culture that limit women’s being listened to and respected. Worse still, women learn that any “no” should come with an explanation for why they are saying no—such as “I can’t tonight because . . . I have my period”—so as not to seem rude. An aggressive “No!” challenges traditional gender norms for women, turning a sexual encounter into something awkward and uncomfortable.

Jozkowski worries that, while affirmative consent policies have good intentions, they simply may be ineffective. They don’t consider the cultural biases and scripts around gender that may impede students from taking up certain words, phrases, and emotional attitudes in sexual encounters. “Campus climate is that thing that needs to change,” Jozkowski writes. “While students need to be involved in this shift, those at the top (including campus administrators, athletic directors and coaches, faculty and staff, and inter- fraternity and PanHellenic councils, etc.) need to take the lead. And in order for them to demonstrate a genuine commitment to eliminating sexual assault, strong campus- level policies need to be in place, and violations of those policies need to result in serious repercussions.” One of the most worrying problems with consent education, according to Jozkowski, is how it still puts the burden on women to prevent sexual assault by asking them to become more “sexually assertive” (yes means yes!) and to protect themselves and their friends through bystander education programs and personal safety programs. Jozkowski is in good company when she also argues that these efforts, though well-intentioned, take the focus off the perpetrators of sexual assault.

While it’s possible to change cultural attitudes over time, affirmative consent policies run counter to the scripts young adults inherit about gender norms and hookup culture. If we don’t engage students in sustained conversations that help them to analyze, evaluate, and critique these norms and narratives (not to mention the ways in which gender, sexual orientation, race, economic background, ethnicity, and religion operate and are expressed within these narratives and norms), our policy and education efforts will amount to little. But most institutions have yet to find new and creative ways of having conversations about consent. They simply haven’t devoted the required resources and time to prevention and education programming. And many schools simply don’t know how to tackle it adequately. Instead, they focus on government compliance and avoiding scandal.

Featured image: Oxford College Christchurch by Jewels. Pixabay License via Pixabay .

The post Yes means yes: why verbal consent policies are ineffective appeared first on OUPblog.

April 10, 2019

Germanic dreams: the end

I have not posted any gleanings for a long time, because, sadly, the comments and questions have been very few, but at the moment, I have enough for two pages or so and will answer everybody next week. A few responses, including a private email, to my two most recent essays on dream made me think that I should first say something about people’s efforts to find a convincing etymology of this hard word, and this is what I’ll do today. As usual, I’ll dispense with most references, but will supply anyone who is interested in them with all the necessary information. The heroes of the dream series are Hamlet, Prospero, Walter W. Skeat, and Friedrich Kluge (he especially). Their images will be featured prominently in these pages.

Before the discovery of regular sound correspondences between languages (and that happened only in the early nineteenth century thanks to the works of Rasmus Rask and Jacob Grimm), etymologists worked with attractive look-alikes. Even when they knew Old English, Old High German, and other Germanic languages, they believed that the words in those languages had come directly from some venerable extraneous source: Hebrew (which was allegedly spoken in Paradise), Classical Greek, or Latin, the port of last (linguistic) resort. Since chance coincidences are easy to find, diligent researchers always succeeded in discovering seemingly plausible etymons. Other than that, they acted like modern lexicographers; that is, they copied from one another, and the multiple repetition of the same idea produced an illusion of solidity.

Hamlet, afraid of falling asleep. Image credit: Garrick as Hamlet. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Hamlet, afraid of falling asleep. Image credit: Garrick as Hamlet. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Seventeenth-century researchers considered two main hypotheses: dream was said to go back to either Hebrew radam (with reference to falling asleep) or Greek drâma (“dreams being, as plays are, a representation of something which does not really happen”; the Greek word means simply “deed”). The similarity between dream and Latin dormire “to sleep” could not be missed either, and later Greek drêmō “I run” joined the group of possible etymons. “Run” was forced to mean “to pass swiftly, as a nightly vision does.” In an oblique way, both words are familiar to English speakers: the root dorm– is present in dormant and dormitory, while the Greek root (with a different vowel by ablaut) turns up in –drome (hippodrome, velodrome, etc., including syndrome). A Celtic origin of dream was also sometimes considered.

The eighteenth century marked no progress in the attempts to understand the origin of dream. (Let it be remembered that the old root of dream is draum-, retained by Old Norse draumr and Old High German traum; the Old English and the Old Saxon forms for “dream” were drēam and drōm respectively). Close to Latin dorm– is Slavic drem– (Russian dremat’ “to doze’; other Slavic forms are almost the same), and Noah Webster mentioned it in his 1828 dictionary. The fact that in Latin the vowel precedes r (-orm) while in Slavic it follows r (-rem) is no hindrance for connecting the two words: r and the contiguous vowel often play leapfrog (consider Engl. burn versus German brennen; the Gothic cognate of Engl. third is þriddja, in which þ = th, and so forth). This transposition of sounds is called metathesis. But the vowels in the Latin-Slavic root are incompatible with Germanic au in draum– and with ê in Greek drêmo (they cannot alternate by ablaut), so both impostors fade out of the picture, as behooves volatile dreams.

Walter W. Skeat, torn between noise and bliss. Image credit: Portrait of Walter William Skeat by Elliot & Fry. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Walter W. Skeat, torn between noise and bliss. Image credit: Portrait of Walter William Skeat by Elliot & Fry. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Once serious philology supplanted guesswork, scholars realized that the main problem was to combine “noise; music; joy” and “dream.” It seemed odd to set up two different words, but etymologists had a hard time in trying to understand the connection among all the senses. According to Jacob Grimm, dreams must have been taken for spiritual music (this idea met with disapproval on the part of some of his German contemporaries). Walter W. Skeat wrote in the first edition of his dictionary (1882, but the early installments began to appear in 1879) that the sense of “vision” had arisen from that of “happiness,” because “we still speak of a dream of bliss.” “The original sense,” he added, “is clearly [!] ‘a joyful or tumultuous noise’ and the word is from the same root as drum and drone.” The use of certainly, clearly, and their likes in etymological works is suicidal. Yet I think he was partly right. “Tumultuous noise” appears to be the nucleus from which most of the other senses developed, and, if so, the word dream is indeed onomatopoetic (sound-imitating). But I doubt that originally it had anything to do with joyful noise, let alone happiness or bliss. The crux of the matter is the existence of the Old Saxon noun drōm, which means “noise,?music,” “dream,” and (!) “life, existence.”

The “discourse” (sorry for the use of this overused word) changed radically, when in 1883, the great German philologist Friedrich Kluge suggested that there had been two unconnected nouns, pronounced as draum-: one for “noise” and one for “dream.” He followed his illustrious predecessor Hermann Grassmann, who set up several words in which Germanic au had, in his opinion, once had g in the root. Kluge cited a Greek cognate of draum– with old g after the vowel (see it at the end of last week’s post), which referred to noise and shrieking. Yet only one of Grassmann’s words, namely German Zaum “bridle, rein,” related to Engl. team, not certainly, but quite probably had g (assuming that team is a cognate of Latin dūcere “to pull”).

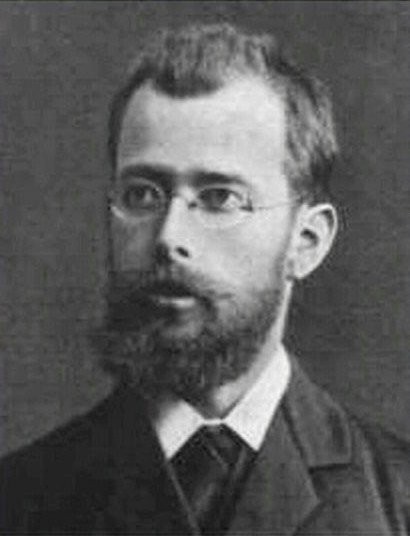

Friedrich Kluge, refusing to see unity where it exists. Image credit: Friedrich Kluge, by unknown author. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Friedrich Kluge, refusing to see unity where it exists. Image credit: Friedrich Kluge, by unknown author. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.James A. H. Murray, the editor of the OED, and Skeat did not endorse Kluge’s reconstruction, but they found it worth considering. Skeat remained cautious almost until the end, but in the last (“Concise”) edition of his dictionary suddenly, that is, without giving any reasons, added that the two words are quite (!) distinct. (How is distinct different from quite distinct? Beware of adverbs!) Although some later etymologists spoke against Kluge’s idea, none of them succeeded in tipping the scale, and modern dictionaries cautiously support Kluge, while remaining noncommittal. Last week, I argued that that there had been only one noun and that we should start with Old Saxon drōm, among whose senses we, surprisingly, find “existence.” Perhaps, I suggested, draum– was once opposed to līf-, as “existence at night, full of the deafening noise from demons” to “daily life, dominated by light, rather than noise.”

Some words for “deception” and “demon” have the root draug-, and Kluge assumed that nightly visions were called dreams because they deceived people. But here he erred: to our distant predecessors dreams were not phantoms or illusions. They were the substance of a real, even if parallel, world; they even prophesized future events. Assuming that the root of dream did once have g, the story began with “noisy existence at night” and “noise.” People probably took it for granted that screeching demons dominated dreams, and sometimes secondary (obvious!) connotations did not arise. Old High German traum and Old Icelandic draumr retained only that meaning (“dream”); the word, it appears, needed no comment. Old Saxon drōm reminds us that draum– could lose its initial reference and acquire the neutral sense “existence.” Elsewhere, we don’t find this sense. Old English emphasized only the idea of noise and expanded that field (drēam “merry noise; singing, music”)—indeed, not Mozart’s Eine kleine Nachtmusik, which many of us enjoy every day when we are put on hold. Be that as it may, etymologies come and go, while our questions and doubts remain, perhaps because “we are such stuff as dreams are made on, and our little life is rounded with a sleep.

Prospero, vanishing like a dream. Image credit: Prospero, Miranda and Ariel, from “The Tempest” by unknown artist. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Prospero, vanishing like a dream. Image credit: Prospero, Miranda and Ariel, from “The Tempest” by unknown artist. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Featured image credit: The Soldier’s Dream of Home by Currier & Ives, New York. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Germanic dreams: the end appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers