Oxford University Press's Blog, page 195

April 3, 2019

How to really build a better economy

The American economy is in great shape in many ways. Riding the cusp of an expansion that started in 2009, the stock market is up, consumer confidence is booming, and unemployment has fallen to historically low levels. But trouble looms. America faces two distinct but related challenges that policymakers must address in the coming years.

The first challenge is rising government debt. Under current policies, debt will rise steadily to unprecedented levels over the next decade and to unsustainable levels over the next 30 years and beyond. Debt isn’t always bad – we’ve had good reasons to borrow in the past to fight recessions and finance investments. Nevertheless, if we don’t rein in the growing debt, it will make it harder respond to wars or recessions, address social needs, and maintain our role as a global leader. This is not a tax problem or a spending problem any more than one side of the scissors does the cutting. It’s the imbalance between the two that creates the problem. Addressing the debt will require both slowing the spending trajectory and raising taxes.

The second challenge is changing the way we tax and spend. The nation has increasingly split into a fractured society with groups separated by disparities in income, education, and opportunity. This growing divide is not only inequitable, it is wasteful, reducing opportunities for tens of millions of Americans. To make Americans more productive and expand opportunity, we need more public investment— in education, healthcare, childcare, nutrition, infrastructure, and scientific research. However, public investments in these areas (other than healthcare) are slated to shrink as a share of the economy to lower levels than any time in the previous half century.

To make Americans more productive and expand opportunity, we need more public investment.

Addressing these twin challenges require three core changes:

Control entitlement spending

Social Security, Medicare (for the elderly), and Medicaid (for some of the poor and elderly) are among America’s most popular and successful programs. Social Security provides more than half of retirement income for about two-thirds of retirees, while Medicare and Medicaid finance healthcare for tens of millions of households. But these programs also drive the increase in federal debt, as an aging population and rising healthcare costs boost federal spending over time.

For healthcare, the way to reduce cost is to increase competition in Medicare via a premium support system, pay providers based on outcomes rather than services rendered, and allow Medicare to negotiate drug prices directly. Health insurance coverage could rise via expansions of Medicaid and private insurance. It’s also important to raise the full retirement age for Social Security, create new protections for early retirees and low-income households, and raise the payroll tax base and rates.

Invest in the future

Safety net programs have proven beneficial impacts. They reduce poverty and crime and raise educational attainment, future earnings, and health status. From a public perspective, they are good investments. It’s therefore important to boost spending on social policy substantially, by a full percentage point of GDP, through 2050 and focus on five areas: investing in children, increasing participation in safety net programs among those who are already eligible, raising educational attainment, increasing employment, and boosting wages of low-income workers.

Scientific research and infrastructure – roads, bridges, airports, etc. – are areas where the private sector is likely to invest too little because it can’t capture all the benefits. However, net federal public investment in infrastructure has been near zero for the past 25 years, and public funds for research have fallen as well. New investments in infrastructure and research and development, of about 1 percent of GDP, would help address this problem through major new public investments in human and physical capital.

Raise and reform taxes

To resolve the nation’s fiscal problems, however, we will need more revenue than what can be obtained through reform of existing taxes.

A good tax system raises the revenues needed to finance government in an equitable and simple way. To finance the added public investments, encourage growth, rein in long-term debt, and distribute tax burdens fairly both within and across generations, we need to raise and reform taxes.

In the income tax a key imperative is to raise taxes on high-income households. Households in the top income groups have experienced enormous income gains, in relative and absolute terms, over the past 30 years, but their taxes have not gone up as a share of income. In a progressive tax system, this is inappropriate. Raising taxes on high-income households is the only way to have them share significantly in addressing the fiscal burden. To that end, we should close capital gains loopholes, repeal the business pass-through subisidies in the 2017 tax overhaul, and replace the mortgage interest deduction with a first-time homebuyers’ credit, increase taxes on estates and inheritances. Another problem with the current system is that evasion rates are high – about one-sixth of all taxes owed are not paid. Increasing the IRS budget would help address this issue.

To resolve the nation’s fiscal problems, however, we will need more revenue than what can be obtained through reform of existing taxes. There are two logical and plausible new taxes to consider. The value-added tax – in existence in 160 countries around the world – would tax consumption and raise significant revenue without hurting saving and investment. A carbon tax would boost the fiscal status further, correct the underpricing of carbon emissions, and provide significant environmental benefits. Both new taxes could be accompanied by measures to offset the burdens on low- and middle-income households.

Through our tax and spending policies, we can expand our economy or let it wither; make society more equal, or less; expand opportunity or continue to let tens of millions of struggling families fend for themselves. There is a way to pay for the government that people want, and shape that government and the economy in ways that serve us all.

Featured image credit: “money-coin-investment-business” by Nattanan Kanchanaprat. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post How to really build a better economy appeared first on OUPblog.

April 2, 2019

Why most scientists think birds are dinosaurs – and you should too

We used to think—and many of us were taught in school—that the dinosaurs went extinct many millions of years ago. But now it seems like this might not be the case. Today’s biologists tend to think birds are dinosaurs, which means that, if true, the dinosaurs did not go entirely extinct after all. Some of them survived.

Scientific ideas can change over time—just as scientific ideas about birds, dinosaurs and extinction have changed over time. Change like this means scientific experts can be wrong, and it also means they can disagree with one another. If scientists today think birds are dinosaurs, then current scientists think past scientists were wrong.

It is also possible for scientists to disagree with one another in the present. And there is present disagreement about whether birds really are dinosaurs. By now, most biologists agree birds are dinosaurs—that they evolved from a group of maniraptoran theropods sometime in the Jurassic Period (around 150 million years ago). But not all biologists are convinced. Some think birds descended independently of dinosaurs, evolving from an earlier group of reptiles, possibly sometime in the Triassic Period (250–200 million years ago).

The group of scientists who agree birds are descended from maniraptoran theropods has been rather cheekily dubbed the “Birds Are Dinosaurs Movement,” or BADM. On this account of the evolutionary history of birds, their closest ancient relatives would have been other maniraptoran theropods, like the charismatic dromaeosaurs (a group including Hollywood star Velociraptor). Those who dispute birds are descended from maniraptoran theropods are committed to the opposing notion that “Birds Are Not Dinosaurs,” or BAND. This was actually the dominant view of most biologists until a series of important fossil discoveries, beginning with Deinonychus antirrhopus (described by John H. Ostrom in 1969).

So, how might one decide between BADM and BAND? One intuitive response to expert disagreement is to think we ought to wait until the science is settled—until there is no more disagreement—before endorsing a position. But this is actually a very problematic stance to take. It is extremely easy to manufacture uncertainty (keeping the science from ever seeming settled), and to generate new sources of debate (leading to novel and perpetual instances of disagreement). This is something that has historically happened with the science linking smoking to lung cancer and with the science linking CO2 emissions to climate change, and with the science unlinking MMR vaccines from autism. Looking at these disputes reveals that uncertainty and debate can linger on, long past when they should reasonably expire as genuine impediments to science and policy.

So, if we cannot use total certainty or complete consensus to settle a scientific disagreement, what can we use? Historically, one popular way to decide is to apply the philosopher of science Sir Karl Popper’s (1934) criterion of falsifiability: to ask which of the positions under scrutiny can be tested, and rejected if they fail the test. If a position is not falsifiable, then it is not scientific, and should be rejected for that shortcoming alone—or, so this line of reasoning goes.

One problem with this line of reasoning is, again, that scientific ideas can change over time. We need to allow for some alteration and development of these ideas, while also honoring the scientific commitment to testing and potentially rejecting them. In the ongoing dispute between BADM and BAND, both positions have offered and tested various claims; both positions have falsified and rejected various hypotheses; both positions have altered and developed their ideas. Popper’s falsifiability criterion does not conclusively help us here.

Another relevant notion we might consider is Thomas Kuhn’s (1962) idea of scientific paradigms. The BADM and BAND camps plausibly are competing paradigms in a Kuhnian sense; however, describing them in this way does not necessarily help decide between them. But what if we could, conceptually speaking, combine these two ideas—Popper’s and Kuhn’s? What if we could adopt Kuhn’s notion of paradigms, in order to appreciate how members of scientific communities consider complex rather than isolated bundles of commitments, along with Popper’s notion of falsifiability, in order to emphasize how scientific processes are designed to empirically test and sometimes reject these commitments?

In the early 1970s, the Hungarian-born philosopher of science Imre Lakatos suggested that looking at scientific research programmes in this sort of hybrid way could distinguish healthy (or progressive) research programmes from unhealthy (or degenerative) ones. A healthy research programme, according to Lakatos, generates testable hypotheses that, when corroborated, add empirical content to the core commitments of the programme. In this way a “protective belt” of material from different sources—of facts the programme can explain, predictions it has risked, and tests it has survived—builds up around the core.

Using Lakatos’ account, it is possible to visually depict theory change and evolution. Depicted this way, it is not at all hard to tell which of the scientific positions on bird origins—BADM versus BAND—is faring better. Look at this Lakatosian depiction of the development of the BAND position:

Image credit: Chronological depiction of the Lakostosian model applied to BAND. Used with permission.

Image credit: Chronological depiction of the Lakostosian model applied to BAND. Used with permission.Now look at an illustration of the theoretical evolution of the BADM position:[image error]

Image credit: Chronological depiction of the Lakostosian model applied to BADM. Used with permission.

Image credit: Chronological depiction of the Lakostosian model applied to BADM. Used with permission.Compare the last entry in each series. Notice how BADM has built an extensive, multi-faceted protective belt around its core, while BAND has not? The BADM position has an extended recent history of both considering and corroborating claims; the BAND position has considered many claims, but has been much less successful when it comes to testing them. In the debate about bird origins, the dinosaurian contingent is winning.

So, did the dinosaurs go extinct? Not entirely. Birds survived, and they are dinosaurs. This position is so well supported by current science that science communicators and educators should feel utterly confident disseminating this view. Scientific researchers in both paleontology and ornithology should likewise expect research that treats birds as dinosaurs to be more cohesive and fruitful than research that does not.

Finally, and speaking more generally, how should we handle scientific disagreement? By conceiving of scientific positions in terms of complex rather than isolated bundles of commitments, and by examining the comprehensive history of empirical testing that each position has. This combined approach can help practitioners and observers alike to distinguish healthy from unhealthy positions in scientific debate.

For more on this topic, please see the author’s recent paper in Systematic Biology, co-authored with paleo-ornithologist N. Adam Smith.

Featured image credit: “Migratory birds” by Myriams-Fotos via Pixabay

The post Why most scientists think birds are dinosaurs – and you should too appeared first on OUPblog.

April 1, 2019

What can we learn from meme culture?

If you go on-line, the chances are that you have encountered memes. What exactly is a meme? Some people take memes to be simply images with added text. The artist Barbara Kruger is often cited as a pre-internet forerunner of this practice. But another kind of meme presents a fascinating window into the ways communities are created and held together. These communal memes, as I call them, are like instructions for a group activity.

In May 2016, the novelist Celeste Ng was bantering with friends on Twitter and mentioned an anxiety dream in which her book, Everything I Never Told You, was published as Some Things I Never Told You. She started playing with altered versions of titles of books by her author friends. Finally, riffing on Fitzgerald’s The Beautiful and the Damned, she tweeted The Reasonably Pretty and the Slightly Sinful along with the newly-minted hashtag #ScaleBackABook. Thousands of people took up the challenge displaying their skill and imagination in changing book titles (Paradise Misplaced Somewhere in my Purse (@helenqterrez), All’s Well that Ends (@masten_j), A Tweet of Two Villages (@DawnReidPM)) and a communal meme was born.

Image credit: Tweet screenshot of the #ScaleBackABook thread. Public domain via Twitter.

Image credit: Tweet screenshot of the #ScaleBackABook thread. Public domain via Twitter.This is a great example for thinking about communal memes. First, we see community functioning in two ways: a community of friends among whom the idea of the meme comes into focus and the community of Twitter-users in general that allows the meme to flourish. What is essential is that the members of the community can see and respond to each other’s efforts. Memes are often associated with the internet because the internet creates large interactive communities. But the same kind of thing as we see in #ScaleBackABook happens in families and groups of friends too, without anyone going online.

Secondly, we can see the way in which instances of the meme, the individual altered book titles, are a kind of performance. One admires (or disparages) the efforts of others (likes, upvotes, downvotes) and occasionally steps into the circle to “show one’s stuff.” The behavior produced by the meme is like a ritualized game, something like the displays of wit in a salon of the ancient régime or playing the dozens.

Thirdly, there is the fundamental role of context in the way in which the instructions for participants are fixed. With #ScaleBackABook, it is because the community is one of Twitter users, who understand how hashtags work, that it suffices for Ng simply to tweet an example and the hashtag itself. She does not need to be explicit.

Image credit: Batman Slapping Robin. Public domain via imgflip.

Image credit: Batman Slapping Robin. Public domain via imgflip. These features are to be found in most communal memes. Consider image macros, where a common image, for example the well-known image of Batman slapping Robin, is customized by the addition of words by each participant.

Without dependence on hashtags, instances of this meme are not confined to Twitter but can appear anywhere. They need not even be digital. Here are some being enacted at a live gathering (along with me talking about them a bit), further emphasizing the performance-like nature of meme-making.

One of the most interesting features of image macros is the way the instructions are fixed and conveyed. With Batman Slapping Robin, the context, besides the on-going practice of image macros, includes a knowledge of how comic books work. The event depicted in the image tells us what kind of text is appropriate. One would need to know almost nothing else to jump straight into this practice. But what sort of text should you add to this image, to make an instance of the Feminist Ryan Gosling meme?

Image credit: “Ryan Gosling” by Elen Nivrae. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: “Ryan Gosling” by Elen Nivrae. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Besides knowledge of image macros in general, one would have to be familiar with other instances of the meme (or to have read explicit descriptions such as the following) to know that the text should come in two chunks, the first “Hey Girl” and the second making some point of feminist theory in a way that sounds like a seduction. You might also learn from that familiarity that you could use any image of Gosling looking fetching.

Image credit: “Feminist Ryan Gosling meme” by Danielle Henderson. Public domain via Tumblr.

Image credit: “Feminist Ryan Gosling meme” by Danielle Henderson. Public domain via Tumblr.Feminist Ryan Gosling memes were initially the creations of a single person, Danielle Henderson. Like the pre-hashtag scaled-back book titles tweeted by Ng, they became the basis for a communal meme. They show how single images with added text might become the basis for communal memes. How are the instructions that constitute a communal meme generated from one or more One-Offs? Hashtags on Twitter are a ready-made device for this transition. Without those, how are the instructions generated? Must all Feminist Ryan Gosling memes start with “Hey Girl”? Must the theory made to sound seductive always be feminist? Only the development of a practice or tradition can settle on the implicit rules an authentic instance has to satisfy (or deliberately flout, but that’s a whole other blog post). And as we know, such practice is always open to the challenge of heterodoxy. Thus communities around a particular meme must always be negotiating the competing interests of rigor and spontaneity, tradition and innovation.

Memes, it turns out, far from being trivial or unimportant, afford us an entry point into thinking about communities, solidarity, performance, practice, and meaning. They can teach us about the ways that norms are created and sustained and how they function to organize communal behavior.

Feature Image Credit: ‘Endlessly Scrolling’ by Robin Worrall. Public Domain via Pixabay .

The post What can we learn from meme culture? appeared first on OUPblog.

From orientalism to ornamentalism

Recently, the Metropolitan Museum of Art hosted an exhibit called China Through the Looking Glass. The exhibition’s spectacular and unabashed display of Orientalist commodification and appropriation charmed many and repelled others. The exhibition, extended months beyond its original schedule due to its enormous popularity, reminds us how enduring the so-called Asian fetish still is in western culture and how limited our critical response is to this expansive phenomenon, other than one of moralistic outrage. Is it not time for us to develop a fuller vocabulary to consider the uncomfortable intimacy between cultural appropriation and recognition? We sit down with Anne Anlin Cheng, author of Image credit: Evening dress by Alexander McQueen and Sarah Burton. Cream silk satin embroidered with blue and white porcelain; white silk organza. From China: Through the Looking Glass, 2015, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Photo by Anne A. Cheng, used with permission.

Lost in this struggle over political correctness, we fail to see what is really arresting about this exhibition and what it can teach us about the force and limits of the contemporary American racial imaginary. How do we understand this conflation between the “Oriental” and the “highly ornamental”—that is, really, a confusion of persons and things? What kind of an idea of “personhood” gets bred out of this kind of confusion? And what function does this peculiar kind of synthetic persons serve for ideals of modern western personhood?

AR: Let’s begin with defining “ornamentalism.”

AC: For me, the word “ornamentalism” names the enduring conflation between the “oriental” and the “ornamental” in western thought and culture. From Plato to Oscar Wilde to Le Corbusier, the “oriental” has always been associated with excessive ornamentation and femininity. We can see this aesthetic trope in the visual expressions of Art Nouveau, French Symbolism, American Rococo, and all the way up to the quite recent Met exhibit. However, more than identifying this enduring style, at once so racialized and gendered, as a symptom of western Orientalism (after Edward Said), I argue that this conflation between persons and things gives us an unprecedented opportunity to reconceptualize the very notion of “racial embodiment.”

AR: What do you mean by a different notion of racial embodiment?

AC: The idea of the flesh (corporeal and embodied; jeopardized and redemptive) has been crucial to race and gender studies for the last several decades. But I think the trope of Asiatic femininity-as-ornamentality demands a slightly more counter-intuitive thinking, in order for us to entertain the possibilities and implications of a kind of racialized gender that is built, not on ideas of organic flesh, but on fantasies of animated ornaments and artifice. Confronted by a brutally dehumanizing history of racism, dare we think about a figure whose survival and flourish depends on crushing objecthood?

I say this is a scary question, but one that we must confront. There is, in fact, this very ancient and still animated figure in our world, who generates passions and derisions in almost every sector of our lives, from the boardroom to the bedroom, from the courtroom to the theater to the big screens. This figure who is at once atavistic and futuristic (think of the geisha robots in the recent film Ghost in the Shell), inorganic and yet imbued with sensorial promises, demands that we rethink racial logic as solely indebted to the flesh.

Instead, let us think differently. Let us work through, rather than shy away from, that intractable intimacy between being a person and being a thing. Let us try to build a different historiography of raced bodies: one constructed through fabrics, ornaments, and “skins” that never enjoyed the fantasy of organicity, one populated by non-subjects who endure as ornamental appendages. Let us substitute ornament for flesh as the germinal matter for the making of racialized gender. Let us, in short, formulate a feminist theory of and for the yellow woman.

AR: Are you worried about using the phrase “the yellow woman”?

AC: I certainly don’t use the term lightly. Coming to say this phrase constitutes something of a therapeutic process for me. It is an ugly term, but I think our “delicacy” about using this term itself says something about the weird combination of aestheticization and denigration directed at this figure. After all, we say white women, black women, brown women, but we do not say yellow woman. It is not because she is exempt from feminist concerns; far from it. And yet the bulk of feminist theory—French feminism, white feminism, black feminism—has overlooked her beyond granting her a nominal pathology.

I use the term “yellow woman” rather than “Asian woman in the West” or “Asian American woman” because these more ameliorative, politically acceptable terms do not conjure the queasiness of this inescapably racialized and gendered figure. I am not so much interested in recuperating “yellowness” as a gesture of political defiance as I am intent on grasping the genuine dilemma of its political exception. What does it mean to survive as someone too aestheticized to suffer injury but so aestheticized that she invites injury?

What makes the yellow woman the exception in the larger category of “women of color” is precisely the precariousness of her injury, a fact that is at once taken for granted and questioned. This figure is so suffused with representation that she is invisible, so encrusted by aesthetic expectations that she need not be present to generate affect, and so well known that she has vanished from the zone of contact. I think it is important and about time that we name the ugly racialization behind her beauty.

Featured image: Woman with a fan. Image by LisaRedfern. CC0 via Pixabay .

The post appeared first on OUPblog.

March 31, 2019

New ways to think about Autism and why it matters

What’s wrong with using the word “spectrum” to describe autism? Perhaps some would suggest that the precise terminology used for referring to these medical conditions is relatively unimportant. In fact, the current terminology facilitates views that distort or oversimplify reality and may be causing harm.

In talking about people with one or another form of autism, phrases such as “severely affected” or “high-functioning” are used frequently, but they can conceal as much as they reveal. These two descriptions are often used as if they were opposites, yet there are probably cases where both descriptions apply to the same person.

An example unrelated to autism may be instructive here. As a teacher of medical, graduate, and undergraduate students, I encounter non-disabled people who are much better at oral than written communication or vice versa. It makes sense to evaluate the two capabilities separately and to tailor any intervention to the skill that is less well developed. The average of the two abilities is not especially helpful for practical purposes. What is the connection to the language used to discuss people with autism?

The needs of any person with autism can be determined to a surprising degree by details that are obliterated when the condition is viewed solely through the lens of severity, i.e. where they are on some spectrum. For someone who wants support or assistance, what specific help they want can be influenced by their goals and circumstances as much as by their particular medical symptoms or behaviors.

Further complicating the effort to fashion useful treatment or intervention, abilities and deficits can be highly uneven among people with a diagnosis of autism. Some people with more cognitive ability are less able or are less comfortable socially than people with less cognitive ability. There are people with outstanding verbal skills but very limited abstract thinking ability.

With respect to severity, it is probably also necessary to distinguish between severity of deficits in abilities or skills and the severity of need for treatment or intervention. So, for example, a highly verbal person may need medical attention and therapy for other issues, related or unrelated to verbal ability.

Other issues of language and conceptualization pertaining to autism were raised in 2017 by Simon Baron-Cohen. In Baron-Cohen’s view, autism is not a disorder, at least most of the time. He argues that individuals with autism are people with different abilities but that their brains are not dysfunctional. He allows that in some cases autism may be associated with disabilities but attributes many of these problems to other conditions.

Perhaps Baron-Cohen’s perspective is the result of what one might call office or lab autism. Some people’s demeanor and actions in a doctor’s office or a researcher’s lab will be inadequately representative of their full repertoire of behavior at home and anywhere else they may go. I found it telling that Baron-Cohen made no mention of episodes of agitation that are often known to parents as “meltdowns.” These very challenging outbursts are not limited to young children. This behavior is reasonably viewed as a type of dysfunction. This sort of behavior is part of the condition of autism.

I do agree with Baron-Cohen that people with autism need greater acceptance and inclusion. At present, a substantial proportion of adults with autism who require some degree of continuing support are socially isolated, struggle to find adequate and stable employment, and have inadequate general medical care. Increased insight into the complexity of autism and its associated clinical problems (coupled with appropriate empathy) might help to improve the lives of these people.

Featured image credit: “Colour, pastel, square” by Markus Spiske. CCO via Unsplash.

The post New ways to think about Autism and why it matters appeared first on OUPblog.

March 30, 2019

The maestro speaks: Ennio Morricone on life and music

Over his esteemed six decade career, Italian composer Ennio Morricone has scored hundreds of movies across numerous genres, most famously the Spaghetti Westerns of Sergio Leone. Many of his most iconic musical cues—to name just three, the coyote-like “wah-wah” of The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly, the haunting harmonica from Once Upon a Time in the West, and the distinct oboe of The Mission—have transcended their films to cement their place in popular culture, referenced in cartoons and commercials, played at sporting events, and even performed by metal bands in concert. Additionally, today’s English-speaking audiences may be familiar with some lesser known pieces from Morricone’s early career in Italy due to their inclusion in recent Quentin Tarantino movies.

Below are excerpts of Ennio Morricone: In His Own Words, a conversation between Morricone and fellow composer (and former protégé) Alessandro De Rosa on life and music. Accompanying these insights are some of the composer’s most influential pieces from cinema.

The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly (1966)

Morricone detailed how he created the legendary “wah-wah” sound in the main theme to Sergio Leone’s masterpiece:

I thought that I might come close to this effect by overlaying two hoarse male voices, one singing “A” the other singing “E” somewhere in between sforzato and falsetto. I went to the recording room, talked about it with the singers, we recorded the voices and added a light reverb and the effect worked. Then I continued this incipit by emulating vocal sounds through the wah-wah effect, which trumpets and trombones obtain by moving the damper back and forth, an effect typical of brass bands in the twenties and thirties.

Morricone experimented with electric instruments to get the haunting theme played at the film’s climax, “The Ecstasy of Gold”:

Along with Edda Dell’Orso’s voice, there was also a distorted electric guitar producing a kind of piercing cry. I noted on the score “distorted electric guitar” and two notes: c and b. [Guitarist Bruno Battisti] D’Amario could freely oscillate between the two pitches with quarter-tones, and I added synthesized sounds as well. These little inventions were very rewarding, and gradually I enriched them with more and more electronic instruments.

Once Upon a Time in the West (1968)

A harmonica played a major role in the plot of Leone’s 1968 Western, thus becoming a central element of Morricone’s score:

The harmonica is the instrument we see in the hands of one of the protagonists, but it gradually turns into a symbol of revenge. From its tangible presence on screen it leads the mind to grasp what the eye cannot reach, transcending the here and now.

Leone’s camera movements for Once Upon a Time in the West related directly to Morricone’s score because the music had been completed before filming began, the opposite of how films are normally scored. This worked especially well in a scene introducing one of the film’s main characters:

Only at that moment does Edda Dell’Orso’s voice enter, followed by a rapid crescendo on the horns leading into the full orchestra, which Leone synced to an upward pan shot of the dolly moving from the window to Jill entering the village. Visually, you move from a detail shot to an establishing shot of the town, and musically from an isolated voice to the full orchestra.

Sacco & Vanzetti (1971)

For the politically-charged 1971 film, Morricone collaborated with singer Joan Baez at the peak of her career:

Unfortunately I did not have the orchestra at my disposal. I was forced to realize an arrangement with the rhythmic section alone: a piano, a guitar, and a set of drums….She sang beautifully, but I had to handle the mix with great attention in order to create uniformity: her identity and that of the orchestra, which we recorded afterwards, needed to blend as well as possible.

The Mission (1986)

Often thought to be one of the biggest slights in Oscars’ history, Morricone’s unforgettable score for The Mission lost at the 1987 Academy Awards. Like the harmonica in Once Upon a Time in the West, an instrument shown on screen featured heavily in the score:

I started with [main character Father] Gabriel’s oboe theme: it’s written in a post-Renaissance style, with all the ornamentations that were typical of that period—grace notes, mordents, grouplets, and appoggiaturas. At the same time, I tried to mimic the way the actor moves his fingers on the instrument in the sequence of his first encounter with the Guarani [natives] who surround him above the falls, firmly intentioned to kill him.

Inglourious Basterds (2009)

Morricone discussed his use of Beethoven’s “Für Elise” in a piece called “The Verdict” for The Big Gundown (1966) and its life beyond that movie, such as its appearance in the opening of Quentin Tarantino’s Inglorious Basterds:

The movie sold so well that [director Sergio] Sollima started to consider it a lucky charm, so from then on he wanted to open every new film with that quote. I did so for his two following movies. When Tarantino utilized it, there was no reason in trying to justify the presence of that quotation… why? What could I object to at that point? If you like it so much, keep it…

Django Unchained (2012)

Again surprised by Tarantino’s method of selecting music, Morricone questioned the director’s use of his demo track in Django Unchained:

He liked it so much that he put it directly in the film, without waiting for the final mix, which eventually was released only in Elisa’s official album. Tarantino is famous for his very peculiar way of dealing with music, but that time he went so far as to use a provisional version!

The Hateful Eight (2015), an Oscar, and the future

In February 2016, The Hateful Eight finally won Morricone a competitive Oscar. Coming at 87, and after 5 previous nominations, it served as a long-awaited feather in the cap of his outstanding career. Yet today, even at the age of 90, the maestro is not entirely finished. His last tour as a conductor will conclude this summer, and there were reports that he would be contributing in some way to Tarantino’s next movie.

We’ll end now with Ennio Morricone’s response when asked if his music will stand the test of time:

Luckily, I don’t have to judge myself; history will put all these day-to-day events in perspective….Music is mysterious; it doesn’t offer many answers. Film music, on the other hand, is even more mysterious at times, both because of its bond with images and because of its way of bonding with the audience.

We think it will.

Featured Image credit: Ennio Morricone – Estadio Bicentenario de la Florida (Chile), 26 November 2013. Cancha General/Gonzalo Tello. CC BY 2.0 via

Flickr

.

The post The maestro speaks: Ennio Morricone on life and music appeared first on OUPblog.

March 29, 2019

Celebrating notable women in philosophy: Philippa Foot

This March, in honour of Women’s History Month, and in celebration of the achievements and contributions of women to the field of philosophy, the OUP philosophy team honours Philippa Foot (1920–2010) as its Philosopher of the Month. Philippa Foot is widely regarded as one of the most distinctive and influential moral philosophers of the twentieth-century. She is best-known for contributing to the revival of the Aristotelian virtue ethics, the theory of ethics developed by Plato and Aristotle that emphasizes the virtues, or moral character, of the person carrying out the action rather than the duties, rules, or the consequences of actions. In ancient time, virtue ethics was a dominant form of ethics

Despite having no formal education as a child, Foot succeeded in obtaining a place at Somerville College, a women’s college within the University of Oxford after taking a correspondence course in Latin. She was one of the remarkable group of women philosophers, including Elizabeth Anscombe, Mary Midgley, and the future novelist Iris Murdoch who studied at Oxford University during the Second World War and developed a shared philosophical viewpoint on moral philosophy. Conscription had reduced the number of men at Oxford University since they were enlisted in war work. As a result, these women had the opportunity to attend the same philosophy classes and make their voices heard in a predominantly female university environment. They became life-long friends and would engage philosophically during their university years and in the years after. Foot would also spend many hours in philosophical discussions with Elizabeth Anscombe who was a student of Ludwig Wittgenstein and influenced her thinking about ethics. Anscombe excoriated consequentialism, which determines the morality of an action upon the consequences of the outcome, and advocated a return to virtue ethics.

Image credit:

Image credit: Dissatisfied with the prevailing moral philosophy of her contemporaries, Foot defended the objectivity of morality against prescriptivism and emotivism of philosophers such as Charles Stevenson, A.J. Ayer and Richard Hare, and the whole moral subjectivism tradition that derived from David Hume. She also considered the important role virtues played in her conception of morality, inspired by the ethics of Aristotle and St. Aquinas. She believed that goodness should be seen as the natural flourishing of humans and that virtues are qualities beneficial to the community. They are essential characteristics that any human being needs to have, both for his own sake and for that of others. Moreover, her approach was influenced by the later work of Ludwig Wittgenstein; her criticism of subjectivism and emotivism can be seen as Wittgensteinian by bringing the attention back to the grammar of moral concepts. To the wider world, she is also associated with the Trolley problem, which raised the question of why it seems morally permissible to steer a runaway trolley aimed at five people toward one person while it may not be acceptable for a surgeon to kill one healthy man to use organs to save five patients.

Foot’s published work mainly consists of essays, most of which are collected in two volumes, Virtues and Vices (1978) , Moral Dilemmas: and Other Topics in Moral Philosophy (2002), culminating in her acclaimed monograph, Natural Goodness (2001) which is considered one of the most important philosophical works on moral philosophy. Her works address a broad range of subjects, including the connection between virtue and happiness, the nature of practical rationality, the limitations of consequentialism, the connection between justice and morality, euthanasia, and abortion. For more on Philippa life and works, view our interactive timeline here:

Featured image credit: Somerville College Oxford, Creative Commons CC-BY-SA-4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Celebrating notable women in philosophy: Philippa Foot appeared first on OUPblog.

March 28, 2019

What Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel tells us about women’s music

Everyone loves a good plot twist. And what better plot twist than finding out that a work of art, scientific discovery, or other creation was the achievement not of a well-known man, but rather a woman? Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel was a talented composer of the early 19th century who worked mostly in private. As an upper-class woman with many social responsibilities and expectations, she was not encouraged to go on to any kind of public career. Instead she hosted concerts in her Berlin, Germany home, performed music with her friends, and composed—a lot. Over 450 works, in fact.

Hensel started to publish her music under her own name just a year before she died, but almost 20 years earlier she published six songs under her brother’s name: Felix Mendelssohn, composer of the famous “Wedding March” and Overture to “A Midsummer Night’s Dream.” Hensel’s family and friends knew about her songs in her brother’s Op. 8 and Op. 9, and the word even spread all the way to Vienna.

Fanny Mendelssohn Bartholdy, by her husband, Wilhem Hensel, 1829. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Fanny Mendelssohn Bartholdy, by her husband, Wilhem Hensel, 1829. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Hensel received a letter from a curious listener who wondered if anything else known as her brother’s was actually by her! Hensel laughed off the idea, but it persisted to our own time. Access to most of Hensel’s music and facts about her life was difficult until the 1990s at the earliest, but then scholars started to slowly discover a more complete picture of her life. Only then were scholars able to understand how unique Hensel’s music was, even if quite similar in style to her brother’s (they developed their style together as students). Once researchers understood her style, and had access to her original scores, letters, and diaries, they could detect which works were hers and which were not.

This is where the story of the lost “Easter Sonata” comes in. Mendelssohn scholars knew the work had existed at one point because it is mentioned in the family letters, but the score had been long lost. Or so people thought. The work had been recorded in France under Mendelssohn’s name in 1972. Because the siblings’ musical style is quite similar, the recording flew under the radar for almost 40 years, until the manuscript was rediscovered and the work was properly attributed to Hensel in 2010. This was due partly to how difficult it was (and still is) for women to enter the historical record of great works of Western art music. Without publicly recognized indicators of success, value is not imputed, and the work fades from memory with the death of its creator.

Audiences expect to go to the concert hall and hear works of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Ludwig van Beethoven, Johannes Brahms, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky and maybe the odd “contemporary” palette cleanser (short, not too offensive–new music has its own canon problems). But when audiences go to hear the work of women, it is often a specially highlighted event. There are invited speakers and lots of press. This is important work and is necessary in order to arrive at a point in history when the inclusion of women in the canon is normalized. There are already many examples of people who are doing this work, and the progress already made in the past few decades is incredibly exciting. In 2016, for example, The Metropolitan Opera of New York City even programmed the first opera by a woman in over a century. There are many easily accessible resources for educators and performers that show how women are working in music today and encourage people to challenge their assumptions.

There is one more highly relevant reason it’s important to normalize works of art by women: everyone should be able to look up to someone who looks like them. The encounter with women’s music should be an everyday thing, not a special occasion. What can we do today to help normalize the music (or other work in any field) of a woman, person of color, or other marginalized social class? No matter how small the effort, it just might encourage and inspire the next great artists.

Featured image credit: the Music Room of Fanny Hensel (nee Mendelssohn) by Julius Eduard Wilhelm Helfft, 1849. Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post What Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel tells us about women’s music appeared first on OUPblog.

March 27, 2019

Perchance to dream? Part 1

Strange as it may seem to those who are not familiar with the niceties of English etymology, dream is not only a word of questionable origin but also a word whose recorded history in Germanic contains a major riddle. However, before presenting this riddle, I would like to repeat what I have said about such matters more than once. From the etymological point of view, some words are indeed hopeless; that is, we do not know enough to suggest reasonable conclusions about their derivation. But it may happen that good conjectures (given the information at our disposal) exist, and one wonders why the most authoritative dictionaries balk at adopting them. Do those conjectures remain unknown to lexicographers (dictionary makers)? This is unlikely. More probably, few editors have the boldness to publish solutions that are not fully secure. James A. H. Murray, Walter W. Skeat, and Friedrich Kluge, to mention only those scholars to whom I constantly refer in this blog (and this list is most incomplete), did not fear losing face and offered many controversial hypotheses and later kept defending or modifying them. Be that as it may, some details in the development of the Germanic word for “dream” seem to have been clarified, even though they are not a hundred percent certain and though dictionaries prefer to ignore them.

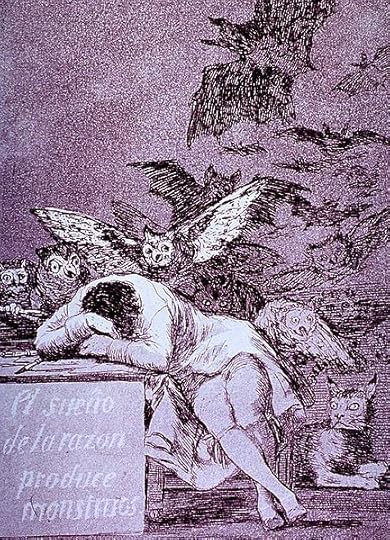

Goya’s etching “The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters” is probably the best-known depiction of a nightmare in art. The Old English word for “dream” could also refer to such demonic visions. Image credit: El sueño de la razón produce monstruos by Francisco Goya. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Goya’s etching “The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters” is probably the best-known depiction of a nightmare in art. The Old English word for “dream” could also refer to such demonic visions. Image credit: El sueño de la razón produce monstruos by Francisco Goya. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.The forms of our word in the Old Germanic texts are as follows. Note only the senses, for all the sound correspondence are regular: dr-m and a long vowel in the middle. It is natural to begin with Old English: drēam “joy, gladness, delight, ecstasy, din, mirth, rejoicing; melody, music, song, singing.” Those glosses have been culled by language historians from the texts in which drēam occurs and are therefore open to interpretation. Perhaps the common denominator of all that joy and singing is noise. On the other hand, “jubilation” may be the underlying concept. Anyway, nothing in the Old English texts reminds us of sleep and dreaming, and this is the root of the trouble.

By contrast, Old Icelandic draumr and Old High German troum meant only “dream” (no noise, no joy). Modern Icelandic draumur, German Traum, and Dutch droom mean the same. In English, dream “a vision during sleep” did not surface in texts before the thirteenth century, and it has been suggested that the word is a borrowing from Scandinavian: allegedly, it either supplanted the native sense of dream or influenced its meaning. Yet it remains unclear whether “noise, din” (or “merriment, jubilation”) and “nightly vision,” the senses recorded in the oldest period, are at all compatible. Many researchers believe that we are dealing with unrelated homonyms.

For some clues, we should turn to an Old Germanic language called Old Saxon. Its speakers were, quite obviously, related to the people who invaded Britain in the fifth century (compare the term “Anglo-Saxon England”), but the texts from the Saxons who remained on the continent go back to the second half of the ninth century. The main of them, a poem modern scholars call Heliand “The Savior,” is a magnificent retelling of the Gospels. In that poem, the word drōm appears multiple times and has three senses.

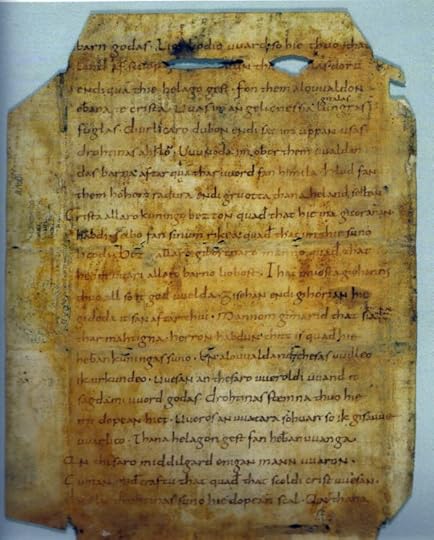

The Berlin Heliand. Image credit: Heliand fragment circa 850. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.“Life on this earth.” It is far from clear how this sense developed. Perhaps the following hypothesis has some value. In Old Germanic, “earthly life” referred to “joy,” with the accent on “joyful existence in the din of communal living.” Modern people’s desire for privacy and quiet was alien to those who lived two millennia before us and even quite some time later. The pre-Christian Germanic concept of life (communal life!) stressed the temporary blessings of our short stay on earth among relatives and allies, rather than an expectation of eternal bliss in heaven.

The Berlin Heliand. Image credit: Heliand fragment circa 850. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.“Life on this earth.” It is far from clear how this sense developed. Perhaps the following hypothesis has some value. In Old Germanic, “earthly life” referred to “joy,” with the accent on “joyful existence in the din of communal living.” Modern people’s desire for privacy and quiet was alien to those who lived two millennia before us and even quite some time later. The pre-Christian Germanic concept of life (communal life!) stressed the temporary blessings of our short stay on earth among relatives and allies, rather than an expectation of eternal bliss in heaven.In the mead hall, people drank, made merry, and one of the many ways to express their happiness was to laugh. Medieval laughter had nothing to do with humor as we understand it; it expressed deep satisfaction, be it at the sight of a vanquished enemy or of belonging to the retinue of the king, the ring-giver. When Beowulf, the hero of a famous Old English poem, died, it is said that he gave up laughter. The Old Icelandic phrase the abode of laughter meant “breast.” (In my book In Prayer and Laughter, I said all I know about this subject and won’t enlarge on it here.) In the Old Saxon Heliand, one finds an analog of the English phrase. When Herod died, we read, he gave up drōm. Other instances of this usage occur elsewhere. Apparently, drōm denoted earthly existence, viewed as a blessing and something worthy of having.

In the episode, known as the wedding at Cana, we are told that men’s drōm in the hall reigned supreme. There is no way of deciding whether this drōm denoted boisterous merriment, joy, or even music. In a similar passage, gaman, instead of drōm, is used. Gaman occurs in almost the same form in Gothic (a Germanic language recorded in the fourth century) and Old English and, most probably, consists of ga-, a collective prefix (like ge– in Modern German), and man “man.” The Gothic noun meant “partner,” so that once again we see that joy (merriment) was synonymous with communal living (partnership, fellowship). The Modern English continuation of this word is game. Thus, drōm was gaman! (Aren’t we embarrassingly close to our overused word fun?) But drōm could also mean “life” in general. While describing one’s existence in both heaven and hell, the Heliand poet uses this word without any compunction. So once again, we should agree that drōm meant “life,” even if the starting point was perhaps “life as joy.”The previous two points would not have been worthy of mention if, in the Heliand, drōm had not also occurred with the sense of “dream.” This is what happened to Joseph: an angel came to him an drōma, that is, in a dream. Two more occurrences of this drōm show that this usage was normal in Old Saxon. I’ll quote only the last of them, because it is almost identical with the one we have just seen: fon them drōma ansprang Ioseph “Joseph jumped up from that dream” (this sentence occurs in the episode “The Flight to Egypt”). An angel appears to Joseph in a dream. Image credit: Joseph’s Dream by Gaetano Gandolfi, c. 1790. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

An angel appears to Joseph in a dream. Image credit: Joseph’s Dream by Gaetano Gandolfi, c. 1790. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.The conclusion is obvious: the word whose modern reflex (continuation) is Engl. dream could occur in one Old Germanic language with two senses: “life” (“joyful existence,” “earthly life,” or “life anywhere,” depending on the context) and “dream,” and it is our task to understand how this blend could develop. Are we witnessing two homonyms or one word with two seemingly incompatible meanings? And here I would like to return to the beginning of the present post. The literature on the history of “dream” is huge, but, on consulting it, one sometimes gets the impression that etymologists have no way of answering the question asked above and are stuck in limbo. I am convinced that no limbo exists, even though the way out of it is neither broad nor straight.

To be continued until light and drōm appear at the end of the tunnel.

Featured image credit: The wedding at Cana by Jan Cossiers. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Perchance to dream? Part 1 appeared first on OUPblog.

How singing in a choir can improve life for seniors

“When my mother died, the music stopped in my house,” said Isabel Heredia. Her mother wasn’t a professional singer, “but she had a fantastic voice. She sang at parties.” Isabel enjoyed singing with her mother at their house in San Francisco but didn’t do any formal singing herself as an adult, although she had been in a choir as a girl in Cuba. Alzheimer’s clouded her mother’s last years, making life hectic for Isabel, who was her mother’s primary caregiver.

“I retired just after my mother died. Then I started getting lazy,” explained Heredia, who had been a Spanish teacher. “I was so busy and worried when my mother was ill that I just let go, watching TV and being passive. That’s detrimental to your health. For people who live alone, the worst thing is to spend the day in your pajamas. You think about going out, but then you watch TV. Not talking with people every day after working two jobs for years, is not good. You need an activity that is constant every week so you will get up, get dressed, and get out.”

She was overjoyed when she heard from a friend about five years ago about the chance to join a community choir for free as part of the Community of Voices study that was being run by the University of California San Francisco. The study aimed to see what impact singing in a choir would have on the quality of life for older adults, particularly those from diverse cultural backgrounds who hadn’t recently been in a choir. The study set up twelve choirs in senior centers and community centers around the city. A music school, San Francisco Community Music Center, worked with the university to create the project and provided teachers to lead the choirs, which sang in English as well as in Spanish and Tagalog.

Isabel Heredia (center) singing with Coro Solera, a San Francisco Community Music Center choir that was part of the Community of Voices study. Image Credit: Courtesy of Isabel Heredia, photo by Martha Rodríguez-Salazar. Used with permission.

Isabel Heredia (center) singing with Coro Solera, a San Francisco Community Music Center choir that was part of the Community of Voices study. Image Credit: Courtesy of Isabel Heredia, photo by Martha Rodríguez-Salazar. Used with permission.“This was tailor-made for me,” said Heredia. “I wanted to sing in Spanish! I already knew a lot of the songs—folk songs, oldies, classics”—songs she had loved singing with her mother. She joined one of the choirs, after first completing an assessment that all study participants had to do: memory exercises and tests of physical, mental, and emotional health. “They did the tests every few months to see if there’s progress. I didn’t mind. I just wanted to sing,” explained Heredia.

“This has been fantastic for me,” she said. She was doing something she loves that gave her a reason to get out of the house and make friends. “If you don’t go, they call you: ‘Where were you? What happened?’ You learn a new song every week. You start learning faster after a while. They do exercises for breathing and rhythm—very beneficial.”

She and other choir members loved the choirs so much that the music school found funding to keep all twelve choirs going—tuition free—after the study ended. A Google Impact Challenge grant helped for one year. Then the school cobbled together funding from local government and social services sources, and from non-profits and private donations. Now, more than 350 older adults sing with the school’s thirteen tuition-free choirs, including a new one at a hospital and rehabilitation center. Heredia, now 80, still sings with the choir she joined for the study, as well as with another choir. “I do other things, too. I take classes. I go to concerts and the ballet with people I meet at choir. Singing is an expression of joy—that also gives you joy.”

The NIH-funded Community of Voices study, one the first randomized controlled trials of a choir intervention, is now completed and its findings, published recently, note that for adults age 60 and over who had not been regular choir members before the study, singing in a choir reduced feelings of loneliness and increased interest in life, compared with similar adults who weren’t in a choir. Other research has found that high rates of loneliness, social isolation, and depression among older adults can cause health problems.

Choirs offer a relatively easy way to develop novel approaches to help older adults stay engaged in the community. There are few requirements for joining other than a willingness to try singing. There are no instruments for participants to buy and learn, as with a band or orchestra. Some choir members felt at first that they couldn’t sing, but with patient encouragement from the choir directors, “somehow it all works,” said Mary Cunningham, who was in the same choir during the study as Heredia and continues to sing with that group. “I can carry a tune but never thought I was good enough to be in a choir,” Cunningham explained. “But really, you can sing if you want to. The choir leaders take us where we are and bring us along. They never make anybody feel they’re not doing it right. Their message is: ‘We’re here to enjoy singing, enjoy each other, and strive to be the best that we can be.’ We perform at senior centers and street celebrations. I’m grateful that the choir exists for me at this time of my life.”

Now that adults age 65 and over are the fastest-growing segment of the U.S. population, choruses for older adults are springing up around the country. In addition to the music school’s choirs in San Francisco, New Horizons International Music Association and Encore Creativity for Older Adults offer choirs specially for seniors in a number of locations. Multi-age choruses at music schools and religious organizations may also welcome singers of all ages and abilities. And for those who wish to create their own choir for seniors, help is out there.

Featured image: Handel, closing bars of Hallelujah Chorus. Public domain via Wikimedia .

The post How singing in a choir can improve life for seniors appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers