Oxford University Press's Blog, page 199

March 7, 2019

Women in law: a legal timeline

In celebration of International Women’s Day, explore our interactive timeline detailing women’s legal landmarks throughout history. Covering from 1835, when married women’s property laws began to be reformed in America, through to future considerations on how the English judiciary system can continue to improve diversity, delve into the key milestones of women’s legal history. In addition, discover the global female pioneers of the legal profession, such as Arabella Mansfield, who was the first female American lawyer or Clara Brett Martin, who was the first female lawyer in Canada.

As well as highlighting key milestones and pioneers, this timeline incorporates links to articles, providing you with further reading on women’s legal history, including a plethora of Oxford University Press’ online journals and other online resources.

Featured image credit: Notebook Work Girl. CCO creative commons via Pixabay.

The post Women in law: a legal timeline appeared first on OUPblog.

Reflecting on gender justice

The Charter of the United Nations (signed in 1945), was the first international agreement to uphold the principle of equality between men and women. Since then there have been many significant achievements in the struggle for the international protection of women’s rights, most notably the United Nation’s landmark treaty the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, the second most widely ratified human rights treaty in existence.

Despite this advancement in gender justice, continued imbalances regarding representation, access, enforcement, and implementation remain. The disproportionate representation of women at major legal organizations and the ratio of female judges on international courts and tribunals such as the International Court of Justice (of the fifteen current judges, three are women) and the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (three of the twenty-one judges are female) are a stark reminder of this imbalance.

In celebration of International Women’s Day on March 8th, we reflect on the representation of women in law, the progression of women’s legal rights, and the gender imbalances still hindering access to justice today.

What is International Women’s Day?

The origins of International Women’s Day rest in feminist protest – against labour discrimination, in pursuit of suffrage, and in campaigns for peace. International Law, today, holds many tools, from The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women to Security Council resolution 1325, to guarantee rights for women and yet we know that gender remains a site of multiple oppressions globally.

International Women’s Day asks us to remember the transformative power of feminist protest as a means to change international law for the better, to remember the Women’s Peace Congress of 1915 and to listen to transnational feminist organisers across communities to articulate new areas for legal change.

Achieving the promise of gender equality

In 2015 as part of the Sustainable Development Goals the world committed itself to achieve gender equality. The Sustainable Development Goals were a result of a UN-led process, involving its 193 Member States, which committed the world to 17 goals as part of its 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. The objectives are far-reaching: to end all discrimination and eliminate violence against women and girls; ensure full participation in decision-making; and achieve universal access to reproductive rights. All this by 2030.

Particularly important is a commitment to recognize and value unpaid care and domestic work. Women still spend three times more time on unpaid work than men, precipitating many into precarious, low-paid work, or reliance on other, poorly-paid women. For the poorest women, inadequate housing and lack of electricity and water intensify the struggle. The Sustainable Development Goals specify four areas for improvement: public services, infrastructure, social protection policies, and shared responsibility within the family.

Achieving gender equality and the empowerment of all women and girls will not happen easily. This requires a concerted effort from all levels of society. We cannot allow governments to reach 2030 without fulfilling their promises. With three years already behind us, we need to work together to ensure that everyone is included.

Women’s right to live free of domestic violence

In 2014, the US Board of Immigration decided that women fleeing domestic violence were entitled to seek asylum if they had been unable to escape their marriage or get assistance from police. In June 2018, Attorney General Jeff Sessions declared that women couldn’t claim asylum in the US on the basis of domestic violence, arguing that they did not constitute a “particular social group” and that domestic violence was “private criminal activity,” not persecution by a government. Responding to an ACLU lawsuit, in December 2018, federal Judge Emmet Sullivan struck down the Sessions policy, arguing that domestic violence victims seeking asylum in the US qualify for “credible fear” interviews, where they can make the case that their government was “unable to protect them from violence.” International courts have reached similar conclusions. The European Court of Human Rights has learned to regard domestic violence as a violation of women’s human rights, even though such violations result from the state’s failure to safeguard women’s rights, not from state persecution. These violations are harder to see, but crucial to recognize in order to protect women’s right to live free of violence.

2019 marks forty years since the Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination Against Women was adopted, but are we really any closer to equality? The theme for International Women’s Day 2019, is “Think equal, build smart, innovate for change”, but are lawmakers thinking equally when it comes to safeguarding women’s rights on domestic violence, healthcare, unpaid work, and maternity leave? Are legal institutions willing to innovate and re-build to address the gender imbalance in female representation? International law is an essential instrument in the battle for gender equality, but how can we ensure that international laws will be interpreted and implemented consistently across the globe, so that no woman or girl is left behind.

Featured Image Credit: “#MARCH4WOMEN” by Giacomo Ferroni. Public domain via Unsplash.

The post Reflecting on gender justice appeared first on OUPblog.

March 6, 2019

Up at Harwich and back home to the west via Skellig

A few more travels, and we’ll reach our destination. Last week (February 20, 2019), we spent some time in Coventry, where no one dispatched us: we went there driven by curiosity. It turned out that the melancholy idiom send one to Coventry may not have anything to do with that town. To reinforce this unexpected conclusion, I’ll relate another story. At one time, the phrase up at Harwich existed; perhaps it is still known in the eastern counties. Harwich is a port in Essex, and up at Harwich means (or meant) “in a state of confusion; at sixes and sevens.” This is what I have read: “Harwich was formerly one, if not the chief, port of embarkation for the continent, and at the same time tedious of access. From Norfolk and Suffolk the whole counties must be crossed, and boat finally be taken before getting to Harwich. From London and Essex, all Essex must be crossed before you reach the extremist point of land in the whole county till you approach the town and harbor in the corner; and when once there, there is ‘nilye willye,’ the stormy sea before you. Hence, when any one drifted into an unpleasant position, and had, if any, only an unwelcome alternative, he was said to be ‘All up at Harwich!’—a place denoting his consequent perplexity and embarrassment of mind.”

The explanation is not particularly trustworthy, though hardly improbable. Yet Walter W. Skeat and a few other people believed that Harwich is a folk etymological variant of harriage, a noun derived from harry, like marriage and carriage, which are derived from the verbs marry and carry. Indeed, harriage is a well-attested legal term meaning “service done by the tenant with his beast of burden.” But the phrase at harriage never existed, so that Skeat’s idea may be the product of his own scholarly folk etymology. We are up at Harwich, though not in the literal sense of the idiom.

In the south of Ireland, people used to go to Skellig to do penance. On the day before Lent, a season in which no marriages are made in the Catholic Church, crowds of unmarried people of both sexes went to Skellig in pairs. There they were supposed to do penance for forty days. Centuries ago, in Skellig, devout monks allegedly used “to enjoy a sharper amount of maceration and general discomfort during Lent.” Hence the proverb to go to do penance at Skellig. Today, Skellig Michael is a tourist attraction, but, if going to Canossa could become proverbial, why not going to Skellig?

In one of the previous posts, I noted that, when one hears go to…, only bad things can be expected. The origin of many such phrases has never been found. About a hundred year ago, people in England used the idiom to go to Warwick “to quarrel.” Perhaps some still do. Was it a joke with reference to the word war? Such cheap puns exist in almost every European language. I would very much like to repeat my question to the readers: if the exotic phrases you have encountered in the recent posts are still used or at least remembered where you live, please send us your comments. Send to Coventry, go to Bath, and go to Jericho have universal currency, but some others were probably very little known even in the nineteenth century (my sources rather seldom go beyond the 1850s). Have they survived? In Worcestershire, they used to say to go up Johnson’s end “to become very poor.” Who was the destitute Mr. Johnson, or is Johnston’s End a place name, and is the phrase still alive?

Sometimes the origin of an idiom is mysterious, even though the form is transparent. Why do some people go to the dogs? Even to go to pot may be less obvious than it seems, but occasionally this or that expression has been traced to its sources with a measure of success. This, I believe, can be said about the phrase to go west “to die.” It already occurred in the sixteenth century (sometimes in the form to go westwards), but surfaced with a vengeance during the First World War and was often discussed then and in the early 1920s. All the explanations I have found on the Internet and a few more were suggested long, and even very long, ago.

Tyborn. Going west. Image credit: Tyburn tree by The National Archives (United Kingdom). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Tyborn. Going west. Image credit: Tyburn tree by The National Archives (United Kingdom). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. Image credit: Charles Kingley – 1899 Westward Ho! cover 2 by Walter Sydney Stacey (1846-1929). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: Charles Kingley – 1899 Westward Ho! cover 2 by Walter Sydney Stacey (1846-1929). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Here they are: 1) The phrase may have come from the idea that the Fortunate Isles or Islands of the Blest, where the souls of the good attain happiness, are situated in the western ocean; 2) the phrase was popularized by the Irish: “The western Irish attach a sinister meaning to west”; 3) gone west was a common expression in Canada some years ago [written in 1918], and probably originated from the fact that the Far West was almost an unknown country, into which if a man ventured, he was considered as lost to his friends”; 4) to Elizabethan writers the phrase meant “ to be hanged,” with reference to the way from the City of London westwards, to Tyburn (or Tiburn), a place of public executions; 5) The reference is to the westering sun. 6) An extract from a Buddhist tract published in the reign of Kien lung [= Quianlong, Chien-lung], about 1748, runs as follows: “in the dynasty Sung [A.D. 960 to 1280]… a certain blacksmith… while in good health… called a neighbor to write the following verse for him ‘Ting Ting Tang Tang, / The iron oft refined, becomes steel at length,/ Peace is near, I am bound to the west.” After uttering these words, he died on the spot. The author of the note asks whether the phrase gone west traveled to Europe via America after having been found by an American missionary in China. (The idea, as I understand it, is: Did the phrase originate in China?). Some of those conjectures are obviously at odds with chronology, to use James A. H. Murray’s favorite turn of speech.

One can risk the tentative conclusion that gone west has been coined more than once by people in different parts of the world, for the sun sets in the west and is seen no more. The other associations are secondary. Perhaps the original English form of the idiom was to go westwards. When the idiom resurfaced during the First World War, it was reborn as slang (this is quite obvious from its use in Galsworthy’s 1922 novel The White Monkey, Part 4 of the Forsyte Saga), but it seems to have been crude slang in the Elizabethan days as well. Laughing at death has ancient roots. Yet I’d rather not finish our journey on such a macabre note and quote another old letter to ta periodical: “When a Huntingdonshire [a district of Cambridgeshire] man is asked if he has ever been to Old Weston, and replies in the negative, he is invariably told: ‘You must go before you die’. Old Weston is an out-of-the way village in the county, and until within a few years [written in 1851] was almost inapproachable by carriages in winter; but in what the point of the remark is, I do not know.” Isn’t this question a pun on the phrase to go west (that is, “Old man, go to Old Weston, before you go west”)? However, none of it matters, because nowadays things tend to go south, at least in American English. Some journalists love this idiom.

Featured image credit: Harwich England by Eva Kröcher (Eva K.). England City Coast Harwich Sea. CC BY-SA 2.5 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Up at Harwich and back home to the west via Skellig appeared first on OUPblog.

Schizophrenia and ballet dancer Vaslav Nijinsky

Schizophrenia is the most iconic of all mental illnesses but both its conceptualization and causes remain elusive. The popular image portrays patients convinced of being persecuted and hearing voices that nobody else can hear. In reality this complex brain disorder presents an endless variety of psychotic (delusions and hallucinations) and non-psychotic symptoms. This complexity is at the heart of a century-long debate about whether schizophrenia is a single illness or should be conceptualized as a syndrome, like dementia, in which different illnesses present common symptoms but have different causes.

One important case to look at when considering the origins of schizophrenia is that of Vaslav Nijinsky (1890-1950), the most talented ballet dancer in history, who was diagnosed one hundred years ago.

His biography resembles a novel, filled with drama, anecdotes, and controversies. A child prodigy at the Imperial Russian Ballet School in St. Petersburg, he went to lead Diaghilev’s legendary Ballet Russescompany that exhilarated Europe from 1909. Nijinsky was famous for the prodigious leaps, technical perfection, elegant movements, and delicate expression of emotions as much as for his radical choreographies (figure) that opened modern dance to the general public.

L’après-midi d’un faune, premiered in 1912 at the Théâtre du Châtelet in Paris. The first choregraphy by Nijinsky was the first ‘dissonant’ ballet, uncoupling movements and music, generated a major controversy. Image credit: Nijinsky in “L’Après-midi d’un faune”. Paris by Adolf de Meyer (1868–1946) and Oregonian2012. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

L’après-midi d’un faune, premiered in 1912 at the Théâtre du Châtelet in Paris. The first choregraphy by Nijinsky was the first ‘dissonant’ ballet, uncoupling movements and music, generated a major controversy. Image credit: Nijinsky in “L’Après-midi d’un faune”. Paris by Adolf de Meyer (1868–1946) and Oregonian2012. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.The fame of the God of Dance, as he was called, was extraordinary. For instance, as Russian national, he was under house arrest in Budapest during the First World War. A high-profile international diplomatic agreement was needed for a safe-passage, with the strict condition that Nijinsky must dance again. He was also prone to choleric outbursts and impulsive acts. Once, he threaten to leave the company in Barcelona due to financial disputes and police had to detain him at the train station and bring him back to the theatre.

In 1917, after his second dismissal from the company due to erratic behaviour, Nijinsky settled in Switzerland with his family. He continued to suffer from disruptive delusions and hallucinations, however. He described these experiences richly in his diaries, a masterpiece for self-reported schizophrenia symptoms, and a must-read to all psychiatrists-to-be.

Professor Eugen Bleuler and Nijinsky met on 6 March 1919. The towering figure in psychiatric history assessed the world-famous dancer at the Burghölzli, an asylum near Zurich. Bleuler concluded, “intelligence evidently very good in the past, now he is a confused schizophrenic with mild manic excitement.” Nijinsky was just 30 years old and was never to recover.

Prof. Eugen Bleuler, circa 1900. Image credit: Eugen Bleuler by The National Library of Medicine. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Prof. Eugen Bleuler, circa 1900. Image credit: Eugen Bleuler by The National Library of Medicine. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.During the following twenty years he spent his time in and out of mental health institutions. The majority of the time he was either catatonic or displayed disorganized speech and behaviour. Some of the most renowned psychiatrists of the age—including Ludwig Binswanger, Carl Jung, Nobel Prize winner Julius Wagner-Jauregg, Alfred Adler, and Manfred Sakel —treated Nijinsky, with little success. Nijinsky had barely any symptom-free periods. During the Second World War, Nijinsky narrowly escaped the Nazi program for eradicating patients with mental illness by hiding in a cave. He finally died of kidney failure in London at the age of 60.

Schizophrenia is currently conceptualized as a disorder in which genetic and early-in-life stressors affects the brain development (the so-called neurodevelopmental hypothesis). Subtle cognitive, social, and motor impairments act as silent markers of the disease during childhood, albeit psychosis will emerge after adolescence, when the illness is diagnosed.

Understanding Nijinsky’s case only under this neurodevelopmental prism is challenging, however. As a child he was prodigiously balanced, with formidable strength and harmonic movements. His case does not fit with the neurological soft-signs and subtle motor abnormalities that are signs of neurodevelopmental problems. Indeed, Nijinsky’s biography is filled with tragic events, including repeated physical and sexual abuse before psychosis onset, crudely reported in his diaries. Such traumatic experiences are considered major risk factors for developing psychosis and schizophrenia. Nijinsky’s case might be an iconic case of this group of patients in which trauma is present later in life and not directly related to early neurodevelopmental factors. Unravelling the mechanisms by which trauma is associated to schizophrenia remains a challenge.

Intriguingly, Bleuler was among the first to advocate for a syndrome approach for the disorder. Dementia praecox, the old term for schizophrenia, was first proposed by Emil Kraepelin, after grouping three independent illnesses (paranoia, catatonia and hebephrenia) into a single category or clinical entity. It was Bleuler who in 1911 coined the term schizophrenias, in plural, to highlight the likely different causes for the disorder. The attempts to differentiate schizophrenia subtypes based in clinical features have failed, however, due to poor reliability and frequent overlap between subtypes. A recent effort to deconstruct mental symptoms into their cognitive domains, which also resembles Bleuler’s fundamental symptoms approach, is a new step in the understanding of this complex disorder or group of disorders.

Featured image credit: “Curtain” by Eli Elschi . Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Schizophrenia and ballet dancer Vaslav Nijinsky appeared first on OUPblog.

March 4, 2019

The growing role of citizen scientists in research

A movement is growing where science is no longer restricted to academics but instead it has become a pursuit for the public in general. Nature lovers have unwittingly been acting as data collectors, especially people that create lists of wildlife they see at home, in the park, or during a hike. Birdwatchers are known for making lists of the bird species they see, and scientists have come to realise that these lists can provide extremely useful information for monitoring animal populations. Through initiatives like eBird or the European Bird Portal, checklists are now being used to monitor bird population trends and track migrations. This contribution of the general public to scientific research is called Citizen Science.

Citizen science has been around for a long time; for instance, the Christmas Bird Count in North America first began in 1900. The Christmas Bird Count involves volunteers that conduct organised counts of bird species, within circles of 24km diameter, between 14 December and 5 January each year. This provides important information about bird trends across North America. Today, a number of similar coordinated initiatives aim to stimulate citizen science such as nationwide counts on a specific weekend of garden birds in the United Kingdom, The Netherlands, France, and Germany.

An even larger initiative invites citizens across the globe to observe as many birds as possible in a single day. On 5 May 2018, some 30,443 participants reported 7,025 species to eBird. There are numerous other ways to get involved in citizen science, such as the long running Serengeti Snapshot project where volunteers classify millions of photos collected through camera traps. Citizen science projects have also been designed to include schools and advance environmental education. Reaching out to such wide audiences can prove challenging; societies and conservation organisations can provide an important link between researchers and citizen scientists.

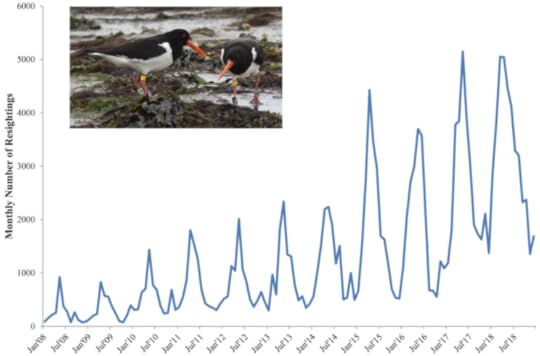

The growth for the number of observations of colour-ringed oystercatchers over time. Inset image is a pair of colour-ringed oystercatchers on the island of Ameland by Tom Voortman. Used with permission.

The growth for the number of observations of colour-ringed oystercatchers over time. Inset image is a pair of colour-ringed oystercatchers on the island of Ameland by Tom Voortman. Used with permission.Citizen science data does create a number of challenges when used in academic research. Citizen science data collection can make it difficult to compare data across years or between different areas. If we return to the Christmas Bird Count, 27 birders took part in the first count in 1900 and observed approximately 90 species. In contrast, over 65,000 participants took part in the 2017-18 Christmas Bird Count. Citizen scientists saw 379 species in Texas alone. It’s important for researchers to control for the largely unstandardized form of data collection. Without addressing factors like the number of people participating, the experience of volunteers, the hours spent in the field, or the distance travelled, it may appear that we have more biodiversity in our cities than in remote natural areas, simply because there are more people in cities reporting what they see.

Despite the challenges of citizen science data, researchers are able to make important insights from the data. Our recent study showed how citizen scientists were vital for identifying the migration patterns of Eurasian Oystercatchers, a bird we’re studying to estimate seasonal survival rates across different regions. The NGOs of Sovon Dutch Centre for Field Ornithology and Birdlife Netherlands launched the citizen science project in 2008. One specific goal was to increase the number of areas where oystercatchers were fitted with colour rings. Oystercatchers with colour rings become uniquely identifiable, allowing researchers to track the birds’ movements and estimate how long they survive. Colour-ringing already occurred on a few specific coastal locations, but the project needed to include birds from other coastal areas and inland areas. Citizen scientists were necessary to covering such large areas. Through a series of outreach events, researchers established 16 new study areas in 2008 where citizen scientists received the necessary training to capture and equip breeding oystercatchers with colour-rings. The project is now into its eleventh year. It has over 40 active ringing groups who have ringed more than 15,000 oystercatchers. Citizen scientists have entered nearly 212,000 observations of these colour-ringed birds. This provides important information about the cumulative human impact on bird populations.

There are an increasing number of opportunities to participate in citizen science, especially with the advent of the internet and, more recently, smartphones. An additional benefit of citizen science is that it strengthens people’s connection with nature, which is important in an ever urbanising world in which we face many environmental challenges. We should also be considering how to develop citizen science projects in schools to enhance children’s connection with nature at a young age.

Featured image credit: Spot the colour-ringed oystercatchers (five in focus, with two more blurred in background) by Tom Voortman. Used with permission.

The post The growing role of citizen scientists in research appeared first on OUPblog.

Public support for tax hikes on the rich is nothing new

In a 60 Minutes interview in early January, newly elected US Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez started a serious political debate when she suggested creating a new 70% tax bracket for annual incomes above $10 million. As a national-level policy proposal, Ocasio-Cortez’s idea is a sharp break with historical trends since 1980. Currently, the top marginal rate is 37 percent for incomes above around $500,000 for single filers (or about $600,000 for joint returns). Predictably, the proposed tax increase on the wealthiest Americans has attracted legions of vocal supporters and detractors among politicians, activists, and analysts. Such tax hikes were almost certainly among the policies President Donald Trump had in mind when he delivered a conspicuous denunciation of socialism in the United States during this year’s State of the Union Address.

But a poll showing nearly 60% support for Ocasio-Cortez’s proposal among registered voters surprised even some analysts sympathetic to the idea. Because registered voters tend to have significantly higher incomes, and lower-income people usually express greater support for tax increases on the wealthy, favorability toward Ocasio-Cortez’s idea would likely have been even greater had this poll sampled US adults overall. Given consistent decreases in upper-income taxes since the early 1980s, the prevalence of free-market/anti-tax rhetoric in the political sphere, and Americans’ oft-cited cultural aversion to paying taxes, how could so many people actually endorse such a steep money-grab from Uncle Sam?

As it turns out, public support for Ocasio-Cortez’s proposal is quite consistent with responses to dozens (perhaps hundreds) of credible polls over several decades. When given an opportunity to weigh in on the general contours of tax policy, significant majorities or pluralities of Americans have long backed higher taxes on the wealthy (and on the large corporations whose shares are disproportionately owned by those at the top of the income scale, and whose leading executives occupy that same economically privileged position). The magnitude of favorability has varied a bit with political and economic conditions, but support for leaning on the rich to pay a greater share toward the common good has been an enduring feature of popular opinion for many decades.

This trend reaches at least as far back as the 1970s and 1980s, sometimes considered the crest of popular anti-tax fervor in the United States. From the George H.W. Bush presidency through most of Barack Obama’s first term, an average of 66% of respondents in 14 Gallup polls said “upper-income people” pay “too little in federal taxes.” In the same polls, no more than 7% said “middle-income people” pay too little, and no more than 22% said the same of “low-income people.” Across the George W. Bush and Obama years, 60% to 70% of adults expressed the belief that corporations pay too little in federal taxes. And from 1985 through 2015, general support for the notion that “the money and wealth in this country should be more evenly distributed among a larger percentage of the people” spanned 56% to 68%. Favorable sentiment toward taxing the rich and big corporations continued to be strong as Obama neared the end of his presidency: A November 2015 CBS News/New York Times poll registered support for “increasing taxes on wealthy Americans and large corporations in order to help reduce income inequality” at 63% of all US adults — including nearly 40% of Republicans. The dawn of the Donald Trump era did little to change these tendencies (see, for example, this ABC News/Washington Post poll from September 2017).

To be sure, there have been notable inconsistencies between Americans’ views on the general shape of tax policy and their responses to specific legislative proposals debated by their representatives. Broader contexts of ideas and communication dynamics often channel and influence poll responses. Information (or its lack), question framing, and the political rhetoric and visual imagery associated with policy issues as they are discussed in the media can significantly influence how the public responds to survey questions. Indeed, Ocasio-Cortez’s progressive image and facility with social media seem to have resonated with many Americans: Public opinion research demonstrates that the messenger and the medium – not just the message – matter. More broadly, there’s little doubt that political and economic circumstances (especially increasing wealth and income inequality) have played a role in the positive responses to Ocasio-Cortez’s proposal and other plans to hike taxes on the rich. America’s changing demographic profile is probably reinforcing these attitudes: The dwindling majority of non-Latinx whites in the United States tends express less worry about economic inequality than does the rest of the population. And even Gen X’ers (let alone Millennials and the rising Generation Z) are more likely than their aging parents to see the economic system as unfair. Still, public support for the 70% tax on top incomes clearly reflects a deeper historical dynamic that has been remarkably impervious to population changes, shifting political winds, and the dizzying 24-7 cable news/Twitter cycle.

Whether or not Ocasio-Cortez’s idea is a “radical” one depends on how that thoroughly loaded term is defined. Her proposal, and similar progressive plans to tax concentrated wealth floated by Senators Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders, are major departures from the normal operation of US tax policy for the last 40 or so years. Such ideas, however, have long resided very much in the center of public opinion. Will higher taxes on the wealthy be endorsed or tolerated by the critical mass of elected leaders needed to enact and sustain these policy changes? The looming tax battles may pose a pivotal test for the American political economy and American democracy alike.

Image Credit: 1 U.S.A dollar banknotes by Sharon McCutcheon. Public Domain on Unsplash

The post Public support for tax hikes on the rich is nothing new appeared first on OUPblog.

March 3, 2019

Contemporary lessons from the fall of Rome

It’s a time-honored game, and any number can play. The rules are simple: just take whatever problem is bothering you today, add the word “Rome,” and voilà. You have just discovered why the mightiest empire in Western history came to an end.

In 1969, Ronald Reagan blamed it on “the twin diseases of confiscatory taxation and creeping inflation.” In 1977, Phyllis Schlafly said it was due to “the ‘liberated’ Roman matron, who is most similar to the present-day feminist.”

And (a personal favorite), in 1984, Joan Collins told Playboy, “It’s like the Roman Empire. Wasn’t everybody running around just covered in syphilis? And then it was destroyed by the volcano.”

So it was all-but-inevitable that, when a mile-long caravan of migrants from Central America began its fateful trek to the U.S. border, the specter would be raised of the waves of barbarian invaders that, we have long been taught, overwhelmed the Empire in the fifth century.

Like all the other reasons for Rome’s fall, this one comes with an implicit message: if we want to avoid Rome’s fate, we had better act. OK. But how?

Build the wall? That didn’t work out too well for the Romans, as the impressive remains of Hadrian’s Wall in England testify.

Let everybody in? The Romans tried that, too. In fact, a historian once suggested that the Fall could boil down to “an imaginative experiment [in citizenship] that got a little out of hand.”

Don’t expect the answer to come from the ivory tower, because academics like to play the game as much as anybody, though usually more subtly. So, at various times, the Fall has been blamed on a decline from rationalism into religious “superstition,” on too much bureaucracy or not enough, on the welfare state, moral decline, globalism, environmental decay, monotheism, lead poisoning, and a drain of precious manpower resources into churches and monasteries (to name but a few).

The common denominator to all these explanations is that they project their authors’ own concerns onto Rome. That is easy enough to do. Rome is a vast tableau, and the Fall didn’t occur in one day or even in one year. It was a long-running process that lasted hundreds of years. Anything you want to look for is probably there.

So if you want to play the game, go right ahead. But here are a couple of suggestions for playing it more usefully.

“more lives were lost due to Romans fighting Romans in constant civil wars than were ever threatened by outsiders.”

First, don’t just look for comparisons; contrasts are equally important. Yes, Germanic peoples fleeing famine or disaster did put pressure on Rome’s frontiers. But as Romans themselves recognized, more lives were lost due to Romans fighting Romans in constant civil wars than were ever threatened by outsiders.

Second, bear in mind that everything changes. If (like Edward Gibbon) you think Rome reached its high point in the second century, then everything that changed has to be a “decline.”

Suppose we taught U. S. history that way. Maybe America at the time of the Founding Fathers was led by smarter and more godlike beings. But are you ready to say that everything from cell phones to fluoride toothpaste represents a decline? Some things are better, some things are worse.

Once you have taken these two steps, you are in a position to identify what it is about Rome, or us, that was essential—the sine qua non, so to speak. Let me suggest that for us it is not a matter of race or religion or even of language. As Abraham Lincoln put it in a speech in 1858, what those “descended by blood from our ancestors” and those immigrants who, he estimated, made up “perhaps half our people” in his day had in common was “that old Declaration of Independence,” where they can find “that all men are created equal.”

If they subscribe to its principles, Lincoln said, “they have a right to claim it as though they were blood of the blood, and flesh of the flesh of the men who wrote that Declaration.” That, he said, is “the electric cord” that makes us all Americans.

In a day when it can easily seem that we are besieged on all sides, we should remember, with Lincoln, the enormous, transformative effect that our political culture has had on the world.

Then maybe, just maybe, we can learn something from Rome’s fall.

Featured image credit: Roman Forum, Rome. Photo by Bert Kaufmann. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons .

The post Contemporary lessons from the fall of Rome appeared first on OUPblog.

Where did the phrase “yeah no” come from?

I’ve noticed myself saying “yeah no.”

The expression came up in a class one day, when I had asked students to bring in examples of language variation. One student suggested “yeah no” as an example of not-quite standard California English.

California, it seems, gets the credit or blame for everything. But “yeah no” is not California English and it’s not just something young people say. It’s been around for a while and is used by males and females, young and old. I began to notice “yeah no” in the speech of others and soon in my own speech as well. Perhaps I had been using it all along and was just now becoming more aware of it.

When I mentioned her use of “yeah no” to a Victorianist colleague, she suggested the usage might have come from a BBC character on the show “Little Britain”, which ran on television from 2003 to 2005. The character Vicky Pollard is a teen slacker stereotype, prone to saying “Yeah but no but yeah but…”. The catchphrase is meant to convey inarticulateness. And the Urban Dictionary gives no less than six “definitions” of “Yeah no” including this one: “An annoying and obnoxious phrase uttered by the simple minded, who don’t think before they speak.”

Yeah no.

It is wrong to think of “yeah no” as an oxymoron and a sign of inarticulate confusion. “Yeah no” is what linguists call a discourse marker. Discourse markers are usually short and sometime vague-seeming parts of a sentence which serve semantic, expressive, and practical functions in speech. They can indicate assent or dissent (or sometimes both). They can indicate attention, sarcasm, hedging, self-effacement, or face-saving.

It is wrong to think of “yeah no” as an oxymoron and a sign of inarticulate confusion.

Examples of “yeah no” abound and there is quite a bit of linguistic commentary, including posts by Stephen Dodson on his Language Hat blog, by Mark Liberman on the Language Log, and by Ben Yagoda in The Chronicle of Higher Education Lingua Franca column. And “yeah no” is not just an English phenomenon. Some of the commentary points to other languages with similar discourse markers, including “Da nyet” in Russian, “oui non” in French, and “ja nein” in German, and more. When I mentioned “yeah no” to a colleague recently back from a sabbatical in South African, she pointed me to the South African English expression “ja-nee.”

Some of the earliest published discussions of English “yeah no” come from Australia, which may mean that the English usage grew there or that Australian researchers noticed it first (or both). In their 2002 article, Kate Burridge and Margaret Florey first explored the variety of uses to which “yeah no” could be put. One is to agree with what has just been said before adding another point—an amplification or clarification. Here is an example in which the second speaker is agreeing and amplifying:

“Do you eat meat?”

“Yeah no, I eat anything.”

But “yeah no” can also be used to acknowledge and disagree:

“Do you eat meat?”

“Yeah no, I eat fish and sometimes chicken.”

The answer assents to eating some meat (fish and chicken) but clarifies that red meat is not on the menu.

Another use of “yeah no” is to signal hesitation and imply mixed feelings, as in this bit of dialogue from Joe Penhall’s play “Landscape with Weapon”:

Dan: Hi.

Ned: Hi Dan. How you doing?

Dan: OK. How are you doing?

Ned: Yeah no, I’m good.

Or this, from Kekla Magoon’s book 37 Things I Love (in no particular order):

Evan … clears his throat: “So I guess you’re not going to the graduation dance?”

“Oh,” I had totally forgotten about it. “Yeah, no. The funeral and everything is that day. So I can’t.”

“Yeah” confirms the not going (yeah, I’m not going) and “no” emphasizes the fact that the character can’t go.

And “yeah no” can be a way of accepting a compliment, as in this Australian example from Erin Moore’s University of Melbourne honors thesis “Yeah-No: A Discourse Marker in Australian English.” Complimented on his team’s success (“You’re doing a very good job at the moment?”), a coach responds by accepting the compliment but also deflecting it.

“Well yeah no, it is pleasing the boys have had a good year, but um as I’ve as I’ve said to the boys, it’s a new year and everyone’s trying to knock you off, and we’ve gotta be up to it.”

The discourse marker “yeah no” is here to stay, and today, you can even buy “Yeah no” tee-shirts and coffee mugs.

Featured image credit: “Conversation on swing” by Bewakoof.com Official. Public domain via Unsplash.

The post Where did the phrase “yeah no” come from? appeared first on OUPblog.

March 2, 2019

Could too low blood pressure in old age increase mortality?

With increasing age, blood pressure rises as a consequence of arterial stiffness, caused by the biological process of ageing and arteries becoming clogged with fatty substances, otherwise known as arteriosclerosis. Large hypertension trials showed that lowering blood pressure in people over 60 is beneficial and lowers the risk of heart attacks, stroke, and all-cause mortality, even in people over 80. Since arterial hypertension, high blood pressure in the arteries, is the most important preventable cause of cardiovascular disease, it seemed obvious for at least two decades to treat hypertension without restrictions even patients over 60.

However, when it comes to the growing population group of people over 80, this may no longer make sense in all, as many of these people tend to have long-term conditions, take a lot of medicines, and have increased frailty. In addition, patients with these characteristics are often included in trials and therefore evidence lacks generalizability. Furthermore, observational studies raise concerns about lowering blood pressure too much, since there are several cohort studies showing that people with lower blood pressure tend to face more problems with dementia and are actually more likely to die.

However, current international guidelines for treating high blood pressure still tells doctors to lower blood pressure to low values of even

Since the appropriateness of lowering blood pressure remains controversial in the oldest-old, we followed patients drawn from the general population for five years to test whether low blood pressure in patients receiving antihypertensive medicine, leads to cognitive decline and increased mortality compared to patients with higher blood pressure.

…a more individual approach instead of “one size fits all” seems most appropriate and is also more patient-centered.

Our findings show that, yes, people with low blood pressure who receive blood-pressure lowering therapy are more likely to suffer from cognitive decline and increased mortality than people with higher blood pressure especially when they are frail. For mental abilities, age seems to play an important role. At age 85 and older, low blood pressure is associated with worse cognitive function, whereas in studies with patients aged 60 and under there was an association of higher blood pressure and cognitive decline.

Doctors thinking about prescribing blood pressure lowering therapy in older patients should consider the specific patients and their therapeutic goals. In the light of these findings, a more individual approach instead of “one size fits all” seems most appropriate and is also more patient-centered. This is especially important for very old and frail patients not just to follow those guidelines, in which people over 80 or frailty have been less considered.

Featured image credit: “Blood cells” by Qimono. Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Could too low blood pressure in old age increase mortality? appeared first on OUPblog.

Celebrating women in politics: 10 books you need to read for Women’s History Month

This March we celebrate Women’s History Month, commemorating the lives, legacies, and contributions of women around the world. Since the inception of the women’s suffrage movement at Seneca Falls in 1848, we have seen a significant increase in women’s involvement in politics and the fight for women’s rights. It is important to honor the ones who stood up and fought before us, especially as we look forward towards the challenges to come.

We’ve compiled a brief reading list that explores the achievements and challenges of women in politics.

Women as Foreign Policy Leaders: Sylvia Bashevkin provides critical insight on women’s leadership roles in contemporary foreign policy, while highlighting the diverse and transformative contributions that Jeane Kirkpatrick, Madeleine Albright, Condoleeza Rice, and Hillary Rodham Clinton made during a series of Republican and Democratic administrations. Read a free chapter online HERE A Seat at the Table: Kelly Dittmar, Kira Sanbonmatsu, and Susan J. Carroll have interviewed over three-quarters of the women serving in the 114th Congress (2015-2017). This book looks at women’s legislative priorities and behavior, details the ways in which women experience service within a male-dominated institution, and highlights why it matters that women sit in the nation’s federal legislative chambers.Women, Power and Politics: As women continue to gain importance in politics as voters, candidates, and officeholders, so does our importance on understanding how gender shapes political power and distribution of resources within our society. Lori Cox Han and Caroline Heldman focus on the role of women as active participants in government and the public policies that affect women in their daily lives.

A Seat at the Table: Kelly Dittmar, Kira Sanbonmatsu, and Susan J. Carroll have interviewed over three-quarters of the women serving in the 114th Congress (2015-2017). This book looks at women’s legislative priorities and behavior, details the ways in which women experience service within a male-dominated institution, and highlights why it matters that women sit in the nation’s federal legislative chambers.Women, Power and Politics: As women continue to gain importance in politics as voters, candidates, and officeholders, so does our importance on understanding how gender shapes political power and distribution of resources within our society. Lori Cox Han and Caroline Heldman focus on the role of women as active participants in government and the public policies that affect women in their daily lives.

Power and Feminist Agency in Capitalism: To instigate change, we need to draw on collective power, but appealing to a particular type of subject, “women,” will always be exclusionary. Claudia Leeb proposes that power structures that create political subjects are never all-powerful. She rejects the idea of political autonomy and shows that there is always a moment in which subjects can contest the power relations that define them.A Feminist in the White House: A feminist, an outspoken activist, a woman without a college education, Midge Costanza was one of the unlikeliest of White House insiders. Doreen Mattingly also reveals a wider, but heretofore neglected, narrative of the complex era of gender politics in the late 1970’s Washington – a history which continues to resonate in politics today.100 Years of the Nineteenth Amendment: Year 2020 will mark the 100th anniversary of the Nineteenth Amendment, giving many women in the United States the right to vote. Holly J. McCammon and Lee Ann Banaszak present this collection of essays to take a look over the past century of women’s political engagement and how much women have achieved. Read a free chapter online

HERE

Power and Feminist Agency in Capitalism: To instigate change, we need to draw on collective power, but appealing to a particular type of subject, “women,” will always be exclusionary. Claudia Leeb proposes that power structures that create political subjects are never all-powerful. She rejects the idea of political autonomy and shows that there is always a moment in which subjects can contest the power relations that define them.A Feminist in the White House: A feminist, an outspoken activist, a woman without a college education, Midge Costanza was one of the unlikeliest of White House insiders. Doreen Mattingly also reveals a wider, but heretofore neglected, narrative of the complex era of gender politics in the late 1970’s Washington – a history which continues to resonate in politics today.100 Years of the Nineteenth Amendment: Year 2020 will mark the 100th anniversary of the Nineteenth Amendment, giving many women in the United States the right to vote. Holly J. McCammon and Lee Ann Banaszak present this collection of essays to take a look over the past century of women’s political engagement and how much women have achieved. Read a free chapter online

HERE

No Ordinary Woman: This book is a biography of Edith Penrose, a remarkable woman and distinguished scholar. Angela Penrose tells Edith’s personal and professional story, weaving it through significant historical events of the twentieth century, reflecting the upheavals and dichotomies of the times. Read a free chapter online

HERE

Performing Representation: Shirin M. Rai and Carole Spary’s comprehensive analysis of women in the Indian parliament explores the possibilities and limits of parliamentary democracy and the participation of women in its institutional performances.Gender Parity and Multicultural Feminism: Around the world, we see a participatory turn in the quest of gender equality, illustrated by the implementation of gender quotas in national legislatures to promote women’s role as decision-makers. Ruth Rubio-Marin and Will Kymlicka explore in their book, the connection between gender parity and multicultural feminism. Read a free chapter online

HERE

No Ordinary Woman: This book is a biography of Edith Penrose, a remarkable woman and distinguished scholar. Angela Penrose tells Edith’s personal and professional story, weaving it through significant historical events of the twentieth century, reflecting the upheavals and dichotomies of the times. Read a free chapter online

HERE

Performing Representation: Shirin M. Rai and Carole Spary’s comprehensive analysis of women in the Indian parliament explores the possibilities and limits of parliamentary democracy and the participation of women in its institutional performances.Gender Parity and Multicultural Feminism: Around the world, we see a participatory turn in the quest of gender equality, illustrated by the implementation of gender quotas in national legislatures to promote women’s role as decision-makers. Ruth Rubio-Marin and Will Kymlicka explore in their book, the connection between gender parity and multicultural feminism. Read a free chapter online

HERE

Historic Firsts: Hilary Clinton was not the first women to run for presidency; Shirley Chisholm ran in 1972, but was unsuccessful. Even with her loss, it was a significant campaign that rallied American votes across various racial, ethnic and gender groups. Can “historic firsts” bring formerly politically inactive people into the electoral process, making it both relevant and meaningful? Evelyn M. Simien explores this idea. Read a free chapter online

HERE

After the Vote

:Author Elisabeth Israels Perry begins with the city’s suffrage movement, which prepared these women for political action as enfranchised citizens. This book illustrates the variety of ways women negotiated the transition from nonpartisan to partisan activism after they won the vote.

Historic Firsts: Hilary Clinton was not the first women to run for presidency; Shirley Chisholm ran in 1972, but was unsuccessful. Even with her loss, it was a significant campaign that rallied American votes across various racial, ethnic and gender groups. Can “historic firsts” bring formerly politically inactive people into the electoral process, making it both relevant and meaningful? Evelyn M. Simien explores this idea. Read a free chapter online

HERE

After the Vote

:Author Elisabeth Israels Perry begins with the city’s suffrage movement, which prepared these women for political action as enfranchised citizens. This book illustrates the variety of ways women negotiated the transition from nonpartisan to partisan activism after they won the vote.Featured image credit: Suffragettes by U.S. Embassy The Hague. CC BY-ND 2.0 via Flickr.com

The post Celebrating women in politics: 10 books you need to read for Women’s History Month appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers