Oxford University Press's Blog, page 203

February 9, 2019

Preventing miscommunication: lessons from cross-cultural couples

We might expect that people will have trouble understanding one another when they are using a foreign language, but several studies have found that overt misunderstandings are relatively uncommon in such situations. The reason for this is that when people can anticipate that some problems of understanding may occur, they adapt the way they speak. They monitor the level of understanding by, for example, checking that the listener has understood, clarifying words and concepts that may be difficult for the listener to grasp, and creating meaning in collaboration with the listener. Listeners, in turn, indicate promptly if they have not understood what the speaker has said and offer tentative interpretations of what they think the speaker might mean.

But what happens when these people fall in love with each other and start a life together? Contrary to common expectations, many partners who have met each other using mainly non-native English as their common language of communication, their lingua franca, continue with English even after years of living under the same roof. They may mix in other languages (which is in fact a very common practice in multilingual environments), but the main language of communication is often very hard to change once one has become comfortable using a certain language with one’s partner.

People in a monolingual relationship may struggle to understand how someone can have a meaningful love relationship using a foreign language. Lingua franca couples report that even strangers will often wonder why they use a language that is not native to either of them – why doesn’t one of them just use the other’s language? And how can the partners really understand each other? A recent large-scale study revealed that problems related to the difficulty of expressing emotions in cross-cultural love relationships will subside in a matter of months. What, then, are the strategies that these couples develop in the course of time, that help them understand each other?

For this purpose, I asked seven couples to record their everyday interactions over a week, and then used detailed conversation analysis to identify misunderstandings and practices that seemed to prevent understanding-related problems from occurring. The results were very interesting.

Misunderstandings were here defined as different from non-understandings. This means that only those occasions were counted toward the total where a partner’s interpretation of his/her spouse’s earlier turn was either rejected, corrected, or understood by the speaker him-/herself to be wrong, or where it otherwise became obvious in the course of the interaction that this candidate understanding significantly deviated from what the partner had intended.

In the 24 hours of naturally occurring audio recordings, I found only 46 misunderstandings. Most of these seemed to occur due to vagueness. For example, a common misunderstanding was caused by the insufficient framing of the object at hand which resulted in miscommunication revealed as the interaction continued: “Oh, that Maria. I thought you were talking about the other Maria!”

Although in these cases, it is easy to blame the speaker, it is important to remember that these speakers know each other well – they can thus expect to understand each other easier than complete strangers. In fact, Arto Mustajoki, Emeritus Professor of Russian Language and Literature from the University of Helsinki, theorizes that this “common ground fallacy” is a common reason for misunderstandings between any speakers: people expect to share a certain amount of knowledge between them and to be on the same wavelength, and thus fail to contextualize their turns accurately enough.

The present study looked at conversational strategies that the couples used to pre-empt problems of understanding and attempt to arrive at a fuller understanding. One of the most common strategies found was that the couples actively communicated non-understanding. They repeated ambiguous items in the partner’s previous turn (A: “It’s the one you bought the first time.” B: “First time?”) and offered candidate understandings mitigated with softeners and rising intonation (“You mean X?”, “Like X?”). They clarified, repeated and paraphrased their own turns until the partner displayed satisfactory understanding, and demonstrated remarkable perceptiveness in monitoring whether the partner had really understood or if they just indicated understanding without actually understanding.

One of the benefits of such relationships is that the partners have at least three languages to which they can resort: both partners’ native languages and the common language. If words fail in one language, they can be retrieved from other languages, and chances are that the partner will understand at least one of those items. This is also one of the strategies that the participants of the study were found to use in attempting to arrive at a shared understanding. But what happens if the partner still doesn’t understand, or if the speaker can’t retrieve the word in any language? Or perhaps the word doesn’t even exist in the language(s) which they most commonly use.

In these cases, the couples used extra-linguistic means to achieve understanding: They imitated or acted out the target word or action, drew a picture while explaining the issue at hand, used deictic items (e.g., this, that, there, over here – words that commonly require a gesture to go along with) or onomatopoeia to make meaning. Especially interactions that were particularly bound to the physical world, such as cooking and renovation planning, stimulated extra-linguistic means. This happened presumably because explaining intentions in these contexts would require specialized vocabulary which the speakers were unlikely to know. Consider the (simplified) example below, where a Norwegian husband (H) is suggesting to his Mexican wife (W) that they should dust icing sugar on top of a cake:

H: We, uhh, I was feeling like, say like melis? Like shh.

W: We could put a little bit. Just a little bit to… make it like, as a decoration, not

as a…

H: Yeah but we need the-uh, one of these.

W: Mmm, do we?

H: Make, if want to make like uh, shh-hh shh.

W: Like a sprinkles?

H: Yeah.

W: Mmm that’s true…

In the first line, the husband uses the Norwegian word melis (icing sugar) which has already been introduced earlier in the conversation. Then he gives an example, “shh”, likely embellished with some kind of a gesture of dusting sugar. The wife seems to understand immediately what he means, and agrees that they could put a little bit of icing sugar, but only as a decoration. The husband then states that they need “one of these”, using a deictic item (taken here to mean a sieve). When the wife questions this, he again uses onomatopoeia, “shh-hh shh” in clarifying what he aspires to do with icing sugar. The last three turns confirm that even without the words “icing sugar”, “sieve”, and “dusting”, the two have managed to successfully negotiate the final touches of decorating the cake.

In sum, the article concludes that long-term couples do not struggle with very many misunderstandings. However, the fact that they know each other so well both facilitates understanding but also causes miscommunication because they fall into the “common ground fallacy.” When it comes to meaning-making strategies, the couples demonstrate remarkable creativity and resilience. In addition to the strategies identified in earlier research, they use an array of extra-linguistic means in making themselves understood better. Perhaps this is something we all could learn from these couples.

Featured Image Credit: ‘two person hands holding mugs on white surface’ by rawpixel. CCO Public Domain via Unsplash.

The post Preventing miscommunication: lessons from cross-cultural couples appeared first on OUPblog.

February 7, 2019

150 Years of the Periodic Table

2019 marks the 150th anniversary of the creation of the periodic table, and it has been declared the International Year of the Periodic Table by the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). In anticipation of the anniversary, and the official opening day ceremony that will take place in France on February 7, Oxford University Press is celebrating the centuries of discover that created the modern Periodic Table.

Here, we take a look at the fascinating history of the people behind the table, starting in 450 BCE and going through the present day, and the way the table and understanding of elements has evolved over time. Even today, many aspects of the periodic table remain unresolved—including a consensus on just how many elements remain undiscovered, leaving much room for discovery and further development in the future.

Featured age credit: “Beaker glass ware” by uncredited. Public Domain via Pxhere.

The post 150 Years of the Periodic Table appeared first on OUPblog.

February 6, 2019

Etymology gleanings for December 2018 and January 2019

In December and January, the ground, as we know from the poem about two quarrelling little kittens, was covered with frost and snow, so that there has not been too much for me to glean, but a few crumbs were worth picking up. However, first I wish to thank those who have been sending questions, correcting and enlightening me, and wishing me another happy year of dealing with language history.

It is better to lie down and sleep than to quarrel and fight. Image credit: Two kittens by Unknown. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

It is better to lie down and sleep than to quarrel and fight. Image credit: Two kittens by Unknown. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.The wheat, the tares, and tare weight

Several people assured me that they had never heard the biblical word tare and know only chaff. Yet the word exists, even if it is partly forgotten. Some of our readers believe that tare is the same word, whether it refers to weight or botany. This is not so. Tare (in botany) is short for tare vetch. Our earliest philologists made unsuccessful guesses while looking for some verb meaning “to strangle, tear, destroy” as the etymon of tare. The English noun has a secure cognate in Dutch, as once pointed out by Johannes Franck, the author of the first modern etymological dictionary of Dutch. The word is tarwe.

Among many other things, Walter W. Skeat wrote numerous notes on English etymology. Here is part of his explanation of tare: “The use of tares in our bibles is perhaps due to Wyclif (sic), who translated the Lat. zizania by ‘taris’; Matt. XIII. 25…. [Franck] suggests, rightly, that [tare] is the equivalent of the Du[tch] tarwe, fem[inine], wheat; M[iddle] Du[tch] terwe. It seems that there were two Teutonic [= Germanic] words for wheat, viz. wheat and tare. Of these, wheat was adopted in all the Germanic languages, whilst tare was confined to English and Dutch. In Dutch, tarwe and weit are both explained as ‘wheat,’ and the use of the two words seems to be a luxury. In English, it is tolerably clear that they were differentiated, wheat being reserved to express the true corn [grain], and tare that which grew up along with it in the same field. At a later time, the compound tare-vetch was formed to signify ‘wheat-vetch,’ or vetch found in the wheat-field.” The rest of the explanation is also interesting, but it is too long to reproduce here in full (Notes on English Etymology, 1901, p. 291). Dictionaries cite Baltic, Latin, and Sanskrit cognates of tare.

Tare “weight in the wrapping, receptacle, or conveyance containing goods” goes back to French tare “weight in goods, deficiency.” Spanish and Italian tara are adaptations of Medieval Latin tara, from an Arabic word meaning “what is thrown away.” Russian tara “packaging materials” is from German, which borrowed it from Italian.

The suffix -en

In olden times. Image Credit: Iliad for Boys and Girls-1907-0187 by A. J. Church. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

In olden times. Image Credit: Iliad for Boys and Girls-1907-0187 by A. J. Church. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.The word olden, now an archaism in the phrases in olden times and in olden days, is hard to explain. Dictionaries inform us that olden is old + –en, a trivial and perhaps even misleading piece of information, for the reference is to the suffix added to nouns (as in wooden, oaken, and the like) but not to other adjectives. Even though olden goes back to Middle English, it has no analogs in the modern language. The timid suggestion that –en may be a relic of the adjectival declension (compare German in den alten Tagen “in old days,” dative plural) carries little conviction. Perhaps Ernest Weekley was right. In his English etymological dictionary, he observed that the noun old also exists, even if preserved only in the phrase of old. Can it not, indeed, be that –en in olden was added to the noun old?

In even “evening,” –en is not a living suffix, though even is obviously related to eve. In the related languages, we find similar forms (compare German Ab-en-d). It has been suggested that the form even is an old past participle, but this reconstruction is flimsy. The adjective even, with cognates in the other Germanic languages, including Gothic, contains only the root of the word, and its distant origin has not been discovered.

Greek musings

Demeter, or Chloe: Indo-European but not Germanic. Image credit: Evelyn de Morgan – Demeter Mourning for Persephone, 1906 by Evelyn De Morgan. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Demeter, or Chloe: Indo-European but not Germanic. Image credit: Evelyn de Morgan – Demeter Mourning for Persephone, 1906 by Evelyn De Morgan. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.I have not looked for the origin of Modern Greek grassidi “grass,” but this word did not occur in the Classical period. “In olden times,” the Greek for “grass” was póa; its rather general synonym (“verdure”) was khlōe, known to us from the name Chloe. So I suspect that grassidi is a late borrowing from some Germanic language. Engl. grass, with cognates everywhere in Germanic, has the same root as grow and green. The root has no known connections with any word in Classical Greek.

By contrast, sparrow requires no guessing. This word has been investigated very well, among other reasons because it occurs in Gothic (sparwa; Mark X: 29 and 31; there, two cheap sparrows are mentioned). It was not a compound and did not mean “seed-picker” but rather “hopper” (though this is not cetin). As a general rule, in researching the origin of a word, one should deal with the oldest form attested in the language, rather than with its modern reflex. It is not Modern but Classical Greek that we need for reconstructing the past of a word in Indo-European.

Robin

It is certainly easy to trace robin to rubinus. It is also easy to trace asparagus to sparrow grass. The question is whether the result is not a product of folk etymology. Everything would have been obvious if rob– ~ rab– did not mean so many things. It should also be borne in mind that, with regard to etymology, dictionaries tend to copy the information from one another. Except for the OED, no one has the time and resources to investigate the origin of every English word, and it is often taken for granted that, if a certain opinion has been repeated many times, it is correct. Incidentally, a correspondent wrote me and asked whether I was serious in suggesting that different epochs have their favorite ways of word formation. Yes, quite serious. For instance, the twentieth century abbreviated like a house on fire (hence doc, prof, lab, bus, ad, gym, dorm, etc.). After the 1917 revolution, countless compounds resembling Engl. op-ed appeared in Russian. One (kolkhoz) has even made it to other languages. By contrast, we “blend” everything. I have recently seen the word slowbalization, a typical modern product. Fashion is an equally strong force in clothes and word formation.

Rabbit

Nether rare nor a rabbit, but certainly Welsh. Image credit: Hix Oyster and Chop House, Smithfield, London by Ewan Munro. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Nether rare nor a rabbit, but certainly Welsh. Image credit: Hix Oyster and Chop House, Smithfield, London by Ewan Munro. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons. The origin of the superstition connected with rabbits is obscure. People pronounce rabbit, rabbit, rabbit for good luck and say “Good morning, rabbits” on the first day of the month. I have a tiny database on this phenomenon, which partly overlaps with the references in Wikipedia, so I have little to say here. Yet I suspect that rabbit is an alteration of some other, probably foreign, word or phrase in an ancient charm or incantation, something like aroint thee witch in Macbeth. It first became rab it and then rabbit. Obviously, in order to work, a charm should be incomprehensible. By way of compensation, I can state with authority that Welsh rabbit is not and has never been rarebit.

The progress of Spelling Reform

The Society’s work is going on well. To those who are sorry to lose the history of English as the result of our efforts I can repeat that first, dozens of modern spellings distort the history of English words; second, that a well-thought out reform will treat each word with extreme care, and third, that Modern English spelling is not a refresher course on the history of Indo-European, so that, if phthisis, God forbid, loses its ph– or committee loses two or three letters, no one will become less educated, but everybody will sigh a sigh of relief. Get off your high horse ~ equus ~ hippos and look through the papers of our undergraduates: after fifteen or so years of “education,” they cannot distinguish between there and their, its and it’s and spell should of done.

An apology

I have an uneasy feeling that not too long ago I received an email with three interesting questions, but I cannot find it. With my sincere apologies to that correspondent, may I ask him to resend me that letter? I promise to answer the questions posthaste.

Featured image credit: Aves en la mañana la luz del sol. CC0 Public Domain via Public Domain Pictures.

The post Etymology gleanings for December 2018 and January 2019 appeared first on OUPblog.

How to do fact checking

The actor Cary Grant once said of acting that, “It takes 500 small details to add up to one favorable impression.” That’s true for writing as well—concrete details can paint a picture for a reader and establish credibility for a writer. Details can be tricky, however, and in the swirl of research and the dash of exposition, it is possible to get things wrong: dates, names, quotes, and facts.

I’ve been doing some fact-checking of my own lately for a book project and have a few tips.

If you don’t know, don’t assume. Is guerilla originally a French word or Spanish? I once assumed it was French, not bothering to check. But it turned out to be Spanish.

Don’t be misled by terminology. I once referred to the Soviet Revolution as occurring in October of 1917, based on the notion that it was the October Revolution. But that’s only true on the Old Style calendar; on the New Style calendar, the revolution took place in November 1917.

Beware of common knowledge. What we think we know may not be the whole story. Take the simple statement that Johannes Gutenberg invented the printing press. He was involved, to be sure, and a key player. But he was not a lone artisan (he had financial backers supporting him and skilled craftsmen working for him) and it is more accurate to say that he devised a revolutionary method of printing with mechanical movable type.

Learn what needs checking. For any project, keep a list of the kinds of things that need to be verified: names, dates, places, arithmetic, and more. Names shift in your memory: Is it Pacific Crest Trail or Pacific Coast Trail? Dates can lead you down a garden path—a film might have been produced in one year and released in the next. Someone elected in 1980 would have taken office in 1981. A bridge or building you mention might not have existed in the time period of your novel.

Information mutates from source to source, so it is preferable to find the original source. Where that isn’t possible, look for the best source possible—something that is peer reviewed or fact-checked.

The arithmetic of lifespans can be tricky as well: If someone was born in 1894 and lived until 1976, how old were they when they died? Eighty-two is what you get by subtracting 1894 from 1976, but the actual age depends on the birth and death days: December 15, 1894 and February 20, 1976 yields eighty-one and change.

Look for original sources. Information mutates from source to source, so it is preferable to find the original source. Where that isn’t possible, look for the best source possible—something that is peer reviewed or fact-checked.

Ask for help. Reach out to librarians, archivists, and other scholars. When I found myself stumped about a particular fact whose citations all pointed to one place, I contacted the author and he helped me resolve the mystery.

Be wary of quotes. Something is often up when a quote appears more than one way. A putative quote from Alice Roosevelt Longworth, Teddy’s tart-tongued daughter, supposedly described Franklin Roosevelt as “ninety percent Eleanor and ten percent mush.” Elsewhere the quote appears as “ten percent mush and ninety percent Eleanor.” And still elsewhere as “two-thirds mush and one-third Eleanor.” When historian Joseph Lash asked her about the quote, she said: “Never, I never said that. … ‘Mush’ is a bad, a silky word. There’s no ring to “mush.” The New York Times obituary of Longworth gave the quote as “one-third sap and two-thirds Eleanor.”

Admit defeat when necessary. When you’ve determined that something is unverified or in dispute, say so. There’s no shame in being uncertain.

Inevitably, you will make a mistake, misread a source, or get fooled. When that happens, someone will correct you and it is best to admit the error, say thank you, make a correction if possible, and learn the lesson. Mistakes can happen to anyone, but every slip is a learning experience.

As for that Cary Grant quote at the beginning, it checks out. The Oxford Dictionary of American Quotations by Hugh Rawson and Margaret Miner includes it and I managed to track it back to a 1964 news article by James Bacon who interviewed the actor and later wrote a biography.

Featured image credit: the book shop by bill lapp. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post How to do fact checking appeared first on OUPblog.

February 5, 2019

How to see inside a pyramid: the power of the mysterious Muon

By the mid-1930s, just five fundamental particles were known. This concise collection of building blocks revealed the true nature of matter and light. Three types of particle: electrons, protons, and neutrons, formed the wide array of atoms known to chemistry. Photons composed the whole electromagnetic spectrum, including light. The fifth particle was the positron, the anti-particle of the electron, predicted by Paul Dirac and discovered by Carl Anderson in cosmic rays. The interactions between these particles were explained in terms of just three forces: electromagnetism, the strong force, which binds the atomic nucleus together, and the weak force, which is responsible for some forms of radioactivity.

The world of particle physics seemed neat and tidy with everything in its place. Then, in 1936, Carl Anderson and Seth Neddermeyer announced the discovery of another new particle in cosmic rays, a particle now known as the muon. The whole physics community was taken aback at the unexpected arrival of a particle with no obvious role in the grand scheme of things. Nuclear physicist Isador Rabi captured their surprise in his memorable reaction: “Who ordered that?”

Our understanding of particle physics has come a long way since the 1930s. The Large Hadron Collider (LHC) blasts high energy protons together and a whole variety of particles are produced in these collisions. Most such particles are composed of quarks and antiquarks and interact via the strong force. These particles are known as hadrons. There are just a handful of particles which do not feel the strong force and the muon is one of these.

Muons behave just like very heavy electrons, with around 207 times as much mass. Like electrons, they feel the electromagnetic and weak forces. Unlike the electron, the muon is unstable, decaying into an electron and two neutrinos with a lifetime of around two microseconds.

Muons undergo numerous interactions when passing through matter, but lose very little energy in each collision. Being so much more massive than electrons, they just brush the electrons to one side as they pass by. Muons are also deflected much less than electrons by the electromagnetic fields within a solid material, so they generate much smaller electromagnetic ripples and lose much less energy in this way as well.

These characteristics mean that muons are the most penetrating of all the particles produced in the LHC apart from the will-o-the-wisp neutrinos that head off into deep space and disappear without a trace.

The outermost parts of the two main detectors at the LHC, known as ATLAS and CMS (Compact Muon Solenoid), are dedicated to tracking the muons created in the proton-proton collisions within the machine. Image credit: “LHC CMS waiting for tracker insertion” by Murial. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia.

The outermost parts of the two main detectors at the LHC, known as ATLAS and CMS (Compact Muon Solenoid), are dedicated to tracking the muons created in the proton-proton collisions within the machine. Image credit: “LHC CMS waiting for tracker insertion” by Murial. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia. The Dragon Of Smoke Escaping From Mount Fuji by Katsushika Hokusai. Image credit: “Hokusai-fuji-koryuu” by Katsushika Hokusai. Public Domain via Wikimedia.

The Dragon Of Smoke Escaping From Mount Fuji by Katsushika Hokusai. Image credit: “Hokusai-fuji-koryuu” by Katsushika Hokusai. Public Domain via Wikimedia.These ultra high energy particles are created in our atmosphere when high energy protons and other cosmic rays from distant regions of the galaxy collide with atomic nuclei in the atmosphere. Every second dozens of them pass through our bodies and an estimated 150 pass through every square metre of the Earth’s surface, penetrating . up to a kilometre of solid ground. They travel further through less dense materials such as air and this has given rise to an important practical application.

Japanese physicists have adapted sensitive muon detectors designed for particle physics experiments to monitor the innards of active volcanoes in a technique known as muon transmission imaging or muography. Detectors are positioned around the volcano and the flux of muons from different directions is measured. There is a greater transmission of muons through low density material such as a cavity within the volcano, so a 3D image of the volcano’s interior is generated, just as an X-ray machine can peer inside a human body. By imaging the volcano over a period of time it is possible to see the magma chamber filling with molten lava which offers the potential to save lives by evacuating the area prior to an eruption.

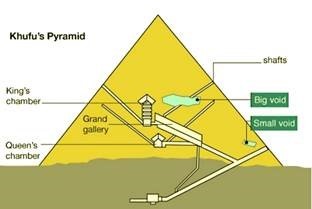

In the same way, muons are now being used to investigate the mysteries of the ancient world. The Pharaoh Khufu ruled Egypt over 4500 years ago and is remembered for building the Great Pyramid on the plateau of Giza close to present day Cairo. Within the pyramid are three chambers: the King’s Chamber, the Queen’s Chamber and an unfinished chamber cut into the bedrock. The pyramid was looted in antiquity and the base of a sarcophagus in the King’s Chamber is all that remains inside. But the Great Pyramid is vast and there has long been speculation that other hidden chambers may exist deep within its structure.

Image Credit: “Khufu’s Pyramid” by Nicolas Mee. Used with permission.

Image Credit: “Khufu’s Pyramid” by Nicolas Mee. Used with permission.The muographers have taken up the challenge of revealing secret rooms hidden within the Great Pyramid. In 2017 a team of physicists led by Kunihiro Morishima of Nagoya University, Japan announced the discovery of a large cavity about 30 metres long above the Grand Gallery within the pyramid. They made this remarkable discovery by placing muon detectors in the Queen’s chamber and using the imaging methods developed for monitoring volcanoes. To confirm the reality of the discovery three different techniques for detecting muons were used, so the physicists are confident their results are correct.

Perhaps, this is the secret chamber where the royal treasures of pharaoh Khufu were hidden 4500 years ago and they have rested there undisturbed ever since. As yet, no-one knows. The team is currently designing a mini flying robot with the aim of investigating further.

An amended version of this article was originally published here on 28th April 2018.

Featured image credit: “Numazu and Mount Fuji seen from Mount Hottanjō, in Numazu, Shizuoka prefecture, Japan” by Alpsdake. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post How to see inside a pyramid: the power of the mysterious Muon appeared first on OUPblog.

Happy Chinese New Year!

This year, the Chinese New Year begins today, February 5th, and people all around the world will be ringing in the year of the Pig. Oxford Chinese Dictionary editor Julie Kleeman shares some insight into the traditions associated with the Chinese New Year celebrations.

Chinese New Year, or the Spring Festival (春节 chunjie) is a fifteen-day celebration beginning on the second new moon after the winter solstice and ending on the full moon fifteen days later.

Sounds complicated? That’s because when marking traditional holidays the Chinese still use a lunisolar calendar, a system that incorporates elements of the lunar calendar with those of the solar calendar.

The Oxford Chinese Dictionary boasts a centre section that contains, among a host of useful lists including those containing Chinese measure words, kinship terms, ethnic groups, SMS abbreviations and a chronology of Chinese historical and cultural events, a page dedicated to Chinese festivals and holidays, featuring brief descriptions of each event and its corresponding date in the lunar calendar.

The list kicks off with 正月初 – the first of the first lunar month, i.e. the New Year, or 春节 chunjie. If the information provided here whets your appetite for more, you can always look up the term itself, and just below the entry for 春节 chunjie you’ll find a handy culture panel on this, the most important of Chinese festivals.

Food

According to the boxed note, 春节 chunjie is a time for families to reunite for a celebratory meal. The main New Year celebrations take place on New Year’s Eve or 除夕 chuxi. This is the biggest of all New Year’s spreads and the dinner is likely to include a veritable feast of delicacies. Chief among them is fish, because 鱼 or yu (the Chinese word for ‘fish’) sounds a lot like 余 or yu (the Chinese word for ‘abundance’).

In northern China no New Year’s Eve is complete without 饺子 (jiaozi), the dumplings, boiled in water, for which northern cuisine is famous. The Oxford Chinese Dictionary contains a culture box dedicated to the popular snack, explaining how it is made and why it is such a staple of the New Year’s feast.

Greetings

One of the most popular greetings at this time of year is 恭喜发财 gongxi facai or ‘may you be prosperous!’ Look up 恭喜 gongxi in the dictionary and you will find 恭喜发财 gongxi facai listed as an example. You will also find a cross-reference to a usage box on popular Chinese greetings or 问候 wenhou that contains other ways of wishing a happy New Year to your Chinese friends.

Spring Festival couplets

Having the dictionary to hand during the Chinese Spring Festival might also help you to decipher 春联 chunlian or ‘Spring Festival couplets’, the black Chinese characters on bright red paper that are pasted up and hung on doorways and storefronts in the run-up to the Chinese New Year.

There are a huge variety of Spring Festival couplets to suit the scenario. Stores generally use couplets that make references to their line of trade, summoning in good fortune in businesses, or a good reputation. At family homes, couplets usually contain messages that invite good luck and happiness for the coming year.

Each couplet is made up of two lines of verse called the “head” and “tail”, which correspond with one other phonologically and syntactically word-for-word and phrase-for-phrase. The “head” is posted on the right side of the front door and the “tail” on the left.

The condensed language form can be difficult to understand, but once cracked promise profound and often clever, double meaning.

For example:

东去山明水秀 dongqu shanming shuixiuWinter has gone, the mountains are clear and the water is sparkling春来鸟语花香 chunlai niaoyu huaxiangSpring has come, the birds are singing and the flowers are fragrantNote that word-for-word, the upper and lower lines are antithetical, and yet the meanings are complementary and the message content is hopeful and uplifting.

If you are looking for a little Spring cheer, the Oxford Chinese Dictionary can help you to decipher even the most complex of Spring Festival couplets. It will also provide you with all the most useful background information, both lexical and cultural, that you could hope for at this time of year.

Dig in and explore to reveal Spring Festival secrets!

A very happy new year to one and all. 新年快乐!

Featured Image Credit: “ hanged red ball lantern” by Humphrey Muleba. Public Domain via Unsplash.

The post Happy Chinese New Year! appeared first on OUPblog.

February 4, 2019

The best strategies to prevent cancer

February 4th marks World Cancer Day and this year, the launch of a new three year campaign called “I Am and I Will,” led by the Union for International Cancer Control. The focus lies on emphasising the importance of each person’s role in the fight against cancer, and reinforcing that everyone has the power to reduce the impact of cancer.

A fundamental step towards reducing the impact is to look towards prevention and understand how to lower the risk of developing the disease. Many lifestyle factors, such as diet and smoking, can play a role in the likelihood of contracting cancer. An estimated 30-50% of cancer cases are preventable by avoiding these risk factors.

In the UK, obesity is the second biggest cause of cancer. While people make their own food choices, it is the responsibility of the government to implement the necessary measures in order to combat the rising obesity rates. Cancer Research UK says, “While we might think we’re in control of what we eat, we’re probably all being influenced more than we realise.” Marketing, cost, and convenience subconsciously influence our decisions – which may not necessarily be the healthiest ones. In an attempt to reduce the child obesity rates of the capital from 40%, junk food advertising will be banned across public transport in London as of this month.

Image credit: Runner by skeeze. Pixabay License via Pixabay.

Image credit: Runner by skeeze. Pixabay License via Pixabay.Exercise levels are a key component of obesity, and numerous studies have looked into the association between physical activity, excess fat and cancer. Although not fully established, various chemicals and hormones (such as estrogen and insulin) appear to affect cell signalling pathways that may lead to the development of cancer. Exercise can help to lessen the levels of these hormones in the body and hence reduce the risk of uncontrollable cell division. Although keeping active may not necessarily result in weight loss, it can play a vital role in maintaining a healthy weight – reducing the risk of 13 types of cancer. Instant benefits of exercising include preventing bowel and breast cancer, improved mood, and higher energy levels.

Most people know that unhealthy eating habits may lead to problems such as heart disease or obesity. However recently there has been focus on consuming certain food types and chemicals found within foods and their effects on cancer. There are many controversies round food groups, e.g. meat and dairy, with studies claiming they either increase or decrease the chances of developing the disease.

Processed meat has emerged in the last few years as a food which should be eaten in moderation and should be limited to around 70g per day. It is estimated that 3 in 20 of male bowel cancer cases are caused as a result of eating too much red meat. While individual people are ultimately responsible for the foods they eat, food manufacturing companies can reduce harms by ensuring clear labelling of foods, and reducing the presence of damaging chemicals and additives.

Bacon by Wokandapix. Pixabay License via Pixabay.

Bacon by Wokandapix. Pixabay License via Pixabay.Consumption of alcohol has been shown to be linked as a risk factor to cancers of the oral cavity, oesophagus, liver, and more. However currently there is no evidence that binge drinking is any better or worse in terms of cancer risk and frequency. In a directly proportional relationship the risk of cancer appears to increase as the quantity of alcohol increases. Alcohol may also increase the levels of estrogen in the body, which is associated with a higher risk for breast cancer.

Smokers have long been informed of an increased risk for lung cancer. In the US alone, 80 to 90% of all lung cancer cases are attributable to smoking. An absence of the habit can prevent fifteen different types of cancer; however the consequences are worse the longer people have smoked. Research suggests that a DNA mutation with the potential to cause cancer occurs once for every fifteen cigarettes smoked. Combining both alcohol and smoking increases the risk by around 33%. Second-hand smoke also increases a non-smokers’ risk of developing cancers of the lung, larynx, and pharynx.

The above risk factors are not the sole cause or single correlation to developing cancer, and are all associated by complex relationships. By not only looking at prevention as a way to reduce the impact of cancer, everyone can share knowledge and make people aware of what changes to make.

Featured image: Books by free photos. Pixabay License via Pixabay. World Cancer Day Campaign Material by Union for International Cancer Control. CC BY-SA 4.0 via World Cancer Day.

The post The best strategies to prevent cancer appeared first on OUPblog.

The Treaty of Versailles: A Very Short Introduction

National self-determination was supposed to be the answer to the so-called “ethnic problem” of the 19th century. The prewar, multi-ethnic Russian, German, and Austro-Hungarian empires, all on the wrong side of history, had disappeared at the end of the First World War never to return. In their place would come relatively homogenous nation-states that would, in theory, reduce the ethnic tension that had undermined the stability of Central Europe and the Balkans. Once each nation possessed its own internationally-recognized borders and resources, Europeans should have a greater incentive to cooperate and fewer reasons to compete.

These new nations had to identify what made them distinct and by what right they could claim a hold on the loyalties of the people who would live inside their artificial borders. The architects of new states like Ukraine, Poland, and Czechoslovakia needed symbols and identifiers. Usually these symbols were rural, recalling ancient common traditions like language, religion, cuisine, literature, and, above all, the importance of links to the land.

Where did this process leave the Jews, few of whom shared these common cultural identifiers? The so-called “minorities” question perplexed the thinkers of 1919. Because the treaties that came out of the Paris Peace Conference changed borders but did not forcibly move people, minorities would end up living in all of the new states. What kind of future could they expect?

The designers of the new world order of 1919 rejected an idea floated by American Jews like Louis Marshall to give the largest minorities their own voice in the League of Nations. Such a system would have been politically messy and might well have required the British to accept an Irish voice and, much to Woodrow Wilson’s horror, the United States to accept an African American or Asian one. Still, the essential problem remained: how to protect minorities in nation-states where their presence would make them stand out as aliens?

The question did not get the attention that it should have. All of the constitutions of the new states made at least rhetorical promises to guarantee the rights of minorities. Wilson thought such constitutional guarantees would suffice; time soon proved him wrong. Some intellectuals in 1919 expected that each minority would benefit from a brother state to look after them. Ethnic Hungarians in Romania, for example, could always appeal to the Hungarian government to make their case for them in the League of Nations. Or, Poland could be expected to treat ethnic Ukrainians inside its borders well because it needed Ukraine to treat ethnic Poles well. This principle of reciprocity would ensure the reasonable treatment of minorities across the continent.

The great exception, of course, was the Jews. They had no state to make a case on their behalf. The Jews of the United States sent money and did their best, but in the 1920s the American government took few concrete steps to slow the growing anti-Semitism in the new states. Immigration laws in 1921 and 1924 virtually closed the United States to Jewish immigration.

Jews in France, Germany, Italy, and the United Kingdom sometimes sent help as well, but many feared that too close an identification with their Jewish brethren might call their own patriotism into question. Assimilated western Jews did not identify with the generally Yiddish-speaking and more Orthodox Jewish communities of the east.

In Germany, home to a particularly well-assimilated Jewish community, the Jews nevertheless appeared as the last remaining minority. The Treaty of Versailles redrew Germany’s borders, in the process taking away most of the Poles and Alsatians who had lived there under the Kaiser’s empire. The Jews remained as the only large minority. They became an easy target for the new German Right.

Anti-Semites and ultra-nationalists also associated Jews with the Bolshevik Revolution and the fears of communism that came with it. Jews, including Rosa Luxemburg in Germany and Béla Kun in Hungary, did hold positions of importance in several Communist movements. Jews, most notably Leon Trotsky, were also prominent in the new Soviet Union. Although many non-Jews were also communists and although most Jews did not support the Soviets, linking Jews and Bolshevism became an all-too simple calumny in 1920s Europe.

The result was a wave of pogroms that targeted Jews as dangerous aliens in the new nation-states. In Poland and Ukraine, especially, accusations of blood libel and Jewish treachery against Christians fueled fears about Jewish threats to national ways of life. With no state willing to help and the British blocking most legal routes to Palestine, Jews found themselves trapped in new states that did not want to accept them into their national projects.

The collapse of the international economy in 1929 marked a deadly turning point. With jobs at a premium, the new states moved to expel Jews from the civil service and ended what limited educational subsidies they had provided to Jewish schools. Anti-Semitic persecution and dehumanization followed as the rise of the Nazi party gave an imprimatur to official anti-Semitism and a model for other states to follow. The European Jews who survived the 1940s recognized the need to ensure that Jews would have a state of their own to protect their interests and to defend their people. By 1948 national self-determination would at long last apply to the Jews as well.

Featured image credit: Europe map 1919. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The Treaty of Versailles: A Very Short Introduction appeared first on OUPblog.

February 2, 2019

Based on a true story [podcast]

In the world of film, members of the audience perceive what they see on screen as realistic, even if what they’re seeing is not actually real. The role and influence of academic consultants has been debated as the impact of historical films in the lens of educating a populous is in question.

On this episode, we examine the significant role of academic consultants within television and movies, particularly historical and science fiction films. The use of consultants on set has steadily increased since the early twentieth century, and we investigate why this trend has become a popular practice and how it impacts the audience, the success of the project, and its cultural impact on society.

We called consultant Diana Walsh Pasulka, the author of American Cosmic: UFO’s, Religion, Technology, to help us weigh in on the significance of academic and historical advisers on film and television sets.

Featured image credit: Red cinema chair by Felix Mooneeram. Public domain via Unsplash.

The post Based on a true story [podcast] appeared first on OUPblog.

February 1, 2019

Raising daughters changes fathers’ views on gender roles

Today, almost three quarters of women with dependent children are working mothers, an increase of 1.2 million over the last two decades. However, this figure hides a substantial gender gap in full-time employment.

The latest figures of the Office for National Statistics show that while more than 9 in 10 working fathers work 30 or more hours a week, only half of working mothers do. Among couple families with both parents in employment, the most common way of organising their activity is for the father to work full-time and the mother to work part-time (49 percent).

While the UK gender pay gap, currently at 8.6 percent among full-time employees, is at its lowest in history, progress towards closing the remaining pay gap has slowed over the last decade.

In addition, women still stem the bulk of housework, meaning they are the ones having to manage the double burden of managing employment and domestic work.

Arguably, some of the root causes for the latter facts are related to the persistence of traditional social norms with regards to gender roles at work and in the household. It is thus important to accelerate changes in people’s attitudes towards gender roles, which haven’t kept pace with changes in the workplace. In this context, it is important to know whether attitudes are malleable and hence how effective efforts to change gender role attitudes and stereotypes can be.

Researchers who have looked at this subject are divided. While some posit that attitudes can change over the life course, others argue that they are formed before adulthood and remain fairly stable thereafter.

We explored this question in greater detail by studying the effect of raising daughters on parental attitudes. We used data from the British Household Panel Survey on 6,332 women and 5,073 men with at least one child under the age of 21 living in their household, covering two decades up until 2012. Parents were asked to rate their agreement with the statement “A husband’s job is to earn money, a wife’s job is to look after the home and family,” on a five-point scale ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree.”

While we find no effect on mothers, the findings reveal that – controlling for a set of confounding factors including age and number of children – fathers are less likely to hold traditional views on gender roles if they raise a girl. Fathers’ likelihood to hold traditional views declines by 8 percent when their daughters reach primary school age and by 11 percent by secondary school age. This timing coincides with the period during which children experience a stronger social pressure to conform to gender norms.

This shows that gender attitudes are malleable and can be shaped by adulthood experiences, at least in industrialised societies such as the UK. Against the background that the persistence of traditional views on gender roles can be a barrier to achieving gender equality inside and outside the workplace, these results are encouraging.

Our findings may extend to other areas as well. For example, while some men might not be attentive to evidence of gender pay gaps and sexist stereotypes, as fathers of daughters they may be. It is possible that through parenting, fathers see the world through a female lens, triggering this shift in views.

Featured Image Credit: “Father and Daughter” by Keelco23. Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Raising daughters changes fathers’ views on gender roles appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers