Oxford University Press's Blog, page 205

January 16, 2019

The tortures of adapting Samuel Richardson’s ‘Pamela’

The term “bestseller” is a bit of a stretch for the eighteenth century, when books were expensive (though widely shared), and information about print-runs is hard to come by. But if any early novel deserves the title, it’s Samuel Richardson’s Pamela, which on publication in 1740 rapidly caught the imagination of Britain, Europe, and indeed America (the Philadelphia printing by Benjamin Franklin was the first unabridged American edition of any novel).

The author of this innovative novel was a leading London printer, and also, it turned out, a brilliant ventriloquist, with an unrivalled understanding of audience tastes and desires in the marketplace for print. Narrated in the voice of its teenage protagonist, Richardson’s tale of a virtuous servant girl who strenuously resists the advances of her predatory master had something for every kind of reader. It was, as Ian Watt wrote in The Rise of the Novel (1957), “a work that gratified the reading public with the combined attractions of a sermon and a striptease.” It was also a work of ground-breaking psychological complexity in which, as Pamela’s persecutor Mr. B at last admits as the plot nears its scandalous conclusion of inter-class marriage, “we have sufficiently tortur’d one another.”

These words supply the title of Martin Crimp’s new play When We Have Sufficiently Tortured Each Other: 12 Variations on Samuel Richardson’s Pamela, which opens at the Dorfman Theatre (the most intimate of the National Theatre’s three auditoria) on January 16th. The play looks to Richardson’s novel for a fresh take on the conflicts of the #MeToo era. Crimp is only the most recent in a long line of playwrights to have exploited Pamela creatively—or sometimes, as Richardson saw it, merely cynically. One mark of the book’s bestseller status is the number of adaptations and other appropriations it inspired at the time: dramatizations, versifications, commentaries, parodies, sequels. You could visit a display of Pamela waxworks, flutter a fan engraved with Pamela scenes, cheer on Pamela horses at the Newmarket races—and all in an age that knew nothing of merchandizing rights. As a friend wryly commiserated with Richardson, the novel had been of great and lucrative service to his “brethren” in the book trade: “witness the Labours of the press in Piracies, in Criticisms, in Cavils, in Panegyrics, in Supplements, in Imitations, in Transformations, in Translations, &c, beyond anything I know of.”

Pamela lent itself especially well to the theatre, in part because of the novel’s epistolary form. One strength of letter-narration in Richardson’s hands was the intimate access it gave to the minute-by-minute flux of consciousness as crisis unfolded in an ongoing present. Another was the dramatic immediacy and vivid colloquial dialogue with which Pamela represented her encounters with Mr. B and other characters, including his “man-like” housekeeper Mrs. Jewkes, who leers greedily at Pamela’s body with her “dead, spiteful, grey, goggling Eye.”

Inevitably, Mrs. Jewkes was played by a man in the earliest stage adaptation by Henry Giffard, which also featured (as Mr B.’s young kinsman Jack Smatter) the rising star actor David Garrick, fresh from his breakthrough role as Richard III. Comic versions took a cue from Henry Fielding’s hilarious satire Shamela (1741), which turned Pamela into a devious social climber (“After having made a pretty free Use of my Fingers, without any great Regard to the Parts I attack’d, I counterfeit a Swoon’) and Mr. B into her dupe and target Squire Booby (“I have destroy’d her … Speak to me, my Love, I will melt my self into Gold for thy Pleasure”). The farces were still going strong a decade later, when A Dramatic Burlesque of Two Acts, Call’d Mock–Pamela: or, a Kind Caution to Country Coxcombs, Interspers’d with Ballads was performed in 1750 at Dublin’s Smock-Alley Theatre. Mock–Pamela survives today in just one known copy.

There were also adaptations by major continental playwrights, notably Voltaire with his three-act version Nanine (1749) at the Comédie française, and Carlo Goldoni with his more faithful Pamela nubile, which opened in Mantua in 1750 before a long and successful run in Venice. Goldoni later produced a sequel, Pamela maritata (1760). Perhaps the social and sexual charge of Richardson’s novel was eroded as it entered the cultural landscape as a fashionable play. But Pamela was always a lightning rod for anxieties about class mobility, and Goldoni made the defensive move of making Richardson’s plebeian heroine turn out, in a convenient last-gasp revelation, to be of noble birth all along. That was not the end of the problem, however.

When François de Neufchâteau’s Paméla, ou la vertu récompensée, a version modelled on Goldoni’s, was premiered in Paris at the height of the French Revolution in 1793, the Committee of Public Safety shut down the production. It was allowed to reopen when Neufchâteau restored Pamela’s original peasant identity, but then closed down again when a Jacobin zealot denounced a speech from the play promoting political and religious toleration (“Point de tolérance politique! c’est un crime!”). This time Neufchâteau and his actors were imprisoned, and the Comédie française went dark. Let’s keep a careful eye on the Dorfman Theatre this month.

Featured image credit: Pamela, 1745 plate. Public Domain via Wikimedia.

The post The tortures of adapting Samuel Richardson’s ‘Pamela’ appeared first on OUPblog.

January 15, 2019

Music in history: overcoming historians’ reluctance to tackle music as a source

Despite their enthusiasm for borrowing from other fields and incorporating new types of source material, many historians remain reluctant to analyze music. For example, when the American Historical Association dedicated its 2015 Annual Meeting to “History and Other Disciplines,” organizers called for work that engaged with anthropology, material culture, archaeology, visual studies, and museum studies, but they were noticeably silent about music and musicology. What explains this aversion?

First, many historians seem to believe that music, more than other cultural practices and products, demands specialized analytical tools. Of course, the field of musicology exists precisely to explicate musical texts and performances in all their specificity, and it does seem foolhardy for historians who lack this specialized training to attempt a technical, formal analysis of music. Yet historians have long since overcome any doubts they may have felt in the face of film or visual art, even though they lack training in film studies or art history. Perhaps they can more easily detect the similarities between films and paintings on the one hand and more familiar, textual sources on the other; they can more readily see the usefulness of the historian’s analytical toolbox for dissecting these sorts of materials: unpacking narratives, decoding symbols, contextualizing meanings, etc. Music, by contrast, seems somehow impenetrable, even ineffable. It is not surprising that many histories of modern, popular music actually focus exclusively on lyrics.

A second, related reason for historians’ unwillingness to engage music as a source is a concern that haunts all cultural history and, in fact, much cultural analysis more generally: the problem of reception. We may be able to describe how a given cultural product makes us feel, what meanings we invest in it, but how can we know how audiences in the past responded? Since the great turn to social history in the 1970s, some historians have in fact avoided any analysis of the content of cultural texts; they attend to the conditions of production and distribution as well as to the context of reception while remaining silent about what the object looks or sounds like. But once again, historians have been quicker to overcome this anxiety in the case of film or visual art than in that of music. The stumbling block here may be the obviously somatic quality of music’s impact. Music moves us physically, and those responses are seldom recorded; for earlier time periods, they obviously never were. How, then, do we avoid universalizing our own experience of music? How do we historicize not just aesthetic judgments, but physical responses?

Those historians who have made music a central object of their analysis have offered convincing answers to these questions. They have deployed their expertise in more conventional archives to contextualize the music they analyze, recognizing that the problem of musical reception is just a version of the basic problem that attends the analysis of any historical source. In this sense, historians have a great deal of relevant experience in reconstructing the meanings people made in the past. The best historical work attends to the specificity of music even as it widens the field of analysis to include its social, political and ideological contexts. Historically minded musicologists – Derek Scott and Thomas Brothers, for instance – have achieved a similar synthesis, but inevitably historians strike a different balance, foregoing some of the technical, formal analysis, while deepening the contextual work and making the musical sources speak to questions of larger, historiographical significance.

The best historical work attends to the specificity of music even as it widens the field of analysis to include its social, political and ideological contexts.

The articles in the Music Histories special section of the Journal of Social History offer powerful examples of this sort of music history. In his contribution to the section, Jason McGraw analyzes Jamaican music in postwar Britain, demonstrating the ways Caribbean migrants used music and dance to forge community in the face of endemic racism. Though scholars have written extensively about ska, reggae, and other Jamaican genres, they have typically focused on the achievements of musicians, charting stylistic influences and explicating cases of individual genius. McGraw, by contrast, reveals how audiences confronted the policing of their communal spaces and the racialization of their communities. By charting the production and consumption of music over time, he sheds new light on the mechanics of identity formation in diaspora and on a key aspect of modern British social history.

James Millward’s article traces the emergence and development of the sitar within the shifting, transimperial and multicultural terrain of the “silk road.” His account reveals the extent of cultural exchange in the premodern and early modern periods, showing how musicians and instrument makers engaged with changing social, political and economic contexts. By setting a specific musical story within these larger contexts, he is able to engage powerfully with ongoing debates about the history of globalization.

Music histories like these do not offer anything as technical as a musicological analysis, yet they treat music as much more than a soundtrack. They delve deeply into the stylistic attributes, technological production and commercial distribution of music, while situating it within broader contexts shaped by migration, empire, and war, as well as by racial, ethnic, and gender hierarchy. And in so doing, they reveal both how rich musical sources and musical stories can be for historians and how much historians have to offer to the study of music. To the extent that social and cultural historians remain interested in how ordinary people exert agency within economic, political and ideological constraints, they ought to venture with less trepidation onto this fertile terrain.

Featured image credit: Violin Strings by Providence Doucet. CC0 via .

The post Music in history: overcoming historians’ reluctance to tackle music as a source appeared first on OUPblog.

January 14, 2019

Protest songs and the spirit of America [playlist]

In a rare television interview, Jimi Hendrix appeared on a network talk show shortly after his historic performance at the Woodstock Music & Art Fair. When host Dick Cavett asked the guitarist about the “controversy” surrounding his wild, feedback-saturated version of “The Star-Spangled Banner,” Hendrix gently demurred.

His performance wasn’t “unorthodox,” he protested. “I thought it was beautiful.”

But Hendrix’s ominous, bombs-bursting version of our national anthem, in fact, would be interpreted as a protest against the war in Vietnam. In a nation born in the spirit of protest, even the national anthem can be heard as a protest song.

With each new social movement of recent years–from Occupy Wall Street and the civil rights demonstrations in Ferguson to #MeToo and the Women’s March–some cultural observers inevitably wonder aloud where all the classic protest songs have gone. They’re thinking, no doubt, about the Civil Rights-era ubiquity of “We Shall Overcome,” or the inspirational, radio-friendly pledge that “A Change Is Gonna Come.”

In truth, for as long as people have been making music, we’ve been inspired by protest songs: songs that take a stand against war and violence, songs that call out the suppression of women, minorities, immigrants, and the working class, songs that lament our treatment of the environment and the self-destructive nature of humankind. Before the United States entered World War I, songwriters published a slew of popular anti-war songs. Kitty Wells became the “Queen of Country Music” after she challenged the sexual double standard with her classic “It Wasn’t God Who Made Honky-Tonk Angels.” Whole genres have arisen out of the urge to push back, from the blues and hip-hop to punk and disco. (Yes, disco.)

Which Side Are You On? may be named for a folk protest song from the Depression era, but the question persists, through each generation and across every style of music. When the line gets drawn in the sand, which side are you on?

Featured image credit: The Obamas and the Bidens link arms and sing “We Shall Overcome”, 2011 by The White House from Washington, DC. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons .

The post Protest songs and the spirit of America [playlist] appeared first on OUPblog.

January 13, 2019

In the face of such ridicule, why would any sane women run for office?

The recent election of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez to Congress has evoked a fair amount of ridicule among persons taken aback by her youth and ideology. She is the “telegenic it girl of the left” according to Daily Beast columnist Matt Lewis. CNBC notes that she has only $7,000 in savings; this is a millennial who is so financially irresponsible that she cannot afford an apartment in D.C. until her first congressional paycheck. And because she wears “that jacket and coat [she] don’t look like a girl who struggles.” Even worse, she is Puerto Rican with “an ethnic name” (per Rush Limbaugh).

No matter one’s political affiliation, it is worth noting that ridicule has been a strategy of silencing women in politics for centuries. One of the first British women to publicly engage in politics was Georgiana Cavendish, Duchess of Devonshire. In 1780, this high-born lady had the nerve to appear on stage with a Whig candidate. Her canvassing on his behalf led cartoonists to display her as a voluptuous temptress who showed off her thighs and exchanged kisses for votes. Eventually, she had to drop her political activities to avoid further embarrassment.

Unfortunately, this slut-shaming of women politicians still appears in the modern era. When researching Ocasio-Cortez, for instance, one may stumble across searches such as “Ocasio-Cortez and breasts” and “Ocasio-Cortez and body pics.” Sexist and sexualized criticisms used to undermine women are not only leveled at left-leaning women in US politics—Nikki Haley, for instance, has been accused of having an affair with President Trump (an allegation she called “disgusting”). Another recent example is a left-wing blogger calling Theresa May, the British Prime Minister, a “whore” after a political defeat. This could be flabbergasting to anyone who has observed May’s demure clothes and manners—far from what the insinuation brings to mind. However, the sexualization of any woman in the public sphere means that the male gaze will supersede her credentials and expertise.

On the other hand, a powerful woman may evoke a different type of ridicule that portrays her as a freak of nature. The editorial cartoons of Margaret Thatcher, the “Iron Lady” who became Britain’s first female prime minister in 1979, include pictures of her with an imperiously long nose and un-feminine stocky body. One cartoon depicts her cavorting with vultures, while others published shortly after her death show a devil cowering in fear of her.

Women who speak out, then, must risk being called freaks of nature—as seen in the 1829 cartoon of Fanny Wright, an outspoken abolitionist and feminist. The image features a goose in a dress standing at a podium and gabbling away. Obviously, she is speaking nothing but nonsense and “deserves to be hissed,” as the cartoonist suggests. In that era, Wright’s critics regarded a female public speaker as violating the laws of nature. Those who argued against the women’s suffrage movement also stressed that allowing women any political power violated God’s laws. Traditionalists may still regard a female public speaker as equally abnormal as a goose proselytizing in a black dress.

One parallel between Ocasio-Cortez and Wright is that they both advocated for positions that apparently challenge the existing social order. Ocasio-Cortez has promoted Medicare for all, mobilization against climate change, and tuition-free public universities. Wright had gone even further in her time by criticizing religious institutions. Her radical ideas included the suggestion that children be sent to boarding schools to be educated outside the home, which outraged many who believed that she was trying to impose atheism on society. By rejecting blind faith in religions, advocating for freedom and education for enslaved Americans, and promoting women’s rights in an era when they had almost none, Wright must have appeared as a freak to many.

Another source of ridicule of women politicians is their unorthodox histories. Ocasio-Cortez, for instance, has worked in restaurants and bartended. Her story is tame compared to that of Victoria Woodhull, the first woman who ran for president; Woodhull had been a child psychic, a 15-year-old bride to an alcoholic, a cigar girl at a raunchy San Francisco port, the first female stockbroker (alongside her sister), a publisher, and a proponent of free love. When she ran for president in 1872, she was called both a lunatic and a prostitute.

In the face of such ridicule, why would any sane woman even want to run for office? Women may simply want to use their brains and exercise their leadership skills. Margaret Chase Smith once expressed her motivations that had resulted in her becoming the first female senator in 1949: “When people keep telling you, you can’t do a thing, you kind of like to try.” Despite being called silly geese and other insults, women are determined to become political leaders.

Featured image credit: A downright gabbler, or a goose that deserves to be hissed by James Akin. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post In the face of such ridicule, why would any sane women run for office? appeared first on OUPblog.

January 12, 2019

Cervical cancer and the story-telling cloth in Mali

Around the world, the arts are being used within communities to address local needs. For such projects to be most effective, program participants must: ensure that their program goals are locally-defined; research which art forms, content, and events might best feed into their program goals; develop artistic products that address their goals; and evaluate these products to ensure their efficacy. The work of the Global Alliance to Immunize Against AIDS Vaccine Foundation in Mali offers one example of how to do this.

Cervical cancer rates are five times higher among women in Africa than in the United States, and Mali has the highest rate of cervical cancer in West Africa. Local health authorities are working with international organizations to make the human Papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine available in Mali. Vaccination would have a significant impact on the cervical cancer burden in Mali, yet the success of prevention methods will hinge on raising awareness about HPV and cervical cancer.

After completing preliminary studies on cervical cancer and HPV knowledge in Mali, the organization responded to a significant need for community awareness and education through a story-telling cloth focused on HPV and cervical cancer. Using textiles for communicating messages is a common practice in Mali and many other parts of Africa; for example, pagnes (term referring to a length of printed fabric) may feature local proverbs, promote particular political leaders, or mark national events. Textile patterns are produced locally and used to make clothes and accessories worn by men and women.

The initiative in Mali centered on a pagne on which the words “I protect myself, I care for myself, and I get vaccinated” are depicted as banners across images of healthy cervixes, fallopian tubes, and uteruses. A background of healthy cells transforms to cancerous cells surrounding HPV viruses, to create a visual narrative connecting HPV infection to the later development of cervical cancer. A key addition to the cloth pattern came from community members: when the imagery and significance was explained during focus groups, women mentioned a specific Malian proverb, “banakoubè kafisa ni bana foura kèyé,” meaning, “it’s better to prevent than to cure.” This proverb was included in the final version of the pattern. Additional preliminary feedback also was incorporated into the pattern; this included color preferences, scale of the design, and changing wording used on the cloth.

Image credit: Healthcare personnel wearing the story-telling cloth at a community health clinic in Bamako, Mali. ⓒ 2015 GAIA Vaccine Foundation. Used with permission.

Image credit: Healthcare personnel wearing the story-telling cloth at a community health clinic in Bamako, Mali. ⓒ 2015 GAIA Vaccine Foundation. Used with permission.The educational pagne was the keystone of a broader program for cervical cancer prevention funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. The goal was to maximize screening at five participating community health clinics, educate neighborhood residents, and discover preferences for HPV vaccination. Starting in March 2015, the organization worked closely with the Mali’s regional health department to run a healthcare worker training program to build capacity for cervical cancer screening. A televised campaign launch featured the cloth and healthcare practitioners involved in the initiative. The organization provided midwives, doctors, and outreach workers with enough fabric to tailor two outfits which were worn during community education sessions in community clinics and surrounding neighborhoods. Community health workers used the cloth to help explain HPV and cervical cancer to women, and to encourage women to attend cervical cancer screenings. Local radio station personalities also promoted the availability of cervical cancer screening. Finally, the organization provided screening supplies during the six months of the campaign.

The results of the project were highly positive. Some 78% of women who participated in a clinic or neighborhood education session had seen the story-telling cloth, and the vast majority was able to accurately identify the imagery. The organization evaluated the efficacy of the HPV story-telling cloth education campaign on awareness by measuring the increase in screening rates, which showed a dramatic five-fold increase over the same period in the previous year. Interest in the HPV vaccine was high; 92.6% of participants in a survey expressed interest in having the vaccine available in Mali, and 87.4% said that they would vaccinate their daughters. When asked why they would choose HPV vaccination for their daughters, 84% of survey participants gave an answer that related to the story-telling cloth awareness campaign; 73% mentioned “prevention” or “protection,” and 11% responded with the exact proverb that was printed on the cloth. Participants received a bag made from the HPV cloth so that they could help educate others. Through the survey, the organization also was able to obtain information about a number of related issues, such as: which parent would need to give consent for vaccinations, how best to contact parents when vaccination is available, and where people prefer vaccinations to be given. This information was reported to public health officials to help ensure that future vaccination efforts are effective.

The Global Alliance to Immunize Against AIDS Vaccine Foundation’s work with textiles and HPV in Mali offers one example of the ways in which people and organizations around the world are using the arts to transform communities. In this case, an organization has drawn upon the historical use of textiles to communicate messages within a community and has developed a new product that meets contemporary needs. This example also shows how organizations can test new products; such tests help program staff to improve designs and ensure that their initiatives have a lasting impact.

Featured image credit: Story-telling cloth for cervical cancer prevention. ⓒ 2015 GAIA Vaccine Foundation. Used with permission.

The post Cervical cancer and the story-telling cloth in Mali appeared first on OUPblog.

January 10, 2019

Life as a librarian in the Māori community

Nearly 700,000 New Zealanders are of Māori descent, with most Māori living in the North Island. Hastings is a city on the North Island, and Hastings District Libraries is made up of three libraries –Flaxmere Library, the Havelock North Library and Community Centre, and the Hastings War Memorial Library which was officially opened in 1959 after the original building was destroyed in the 1931 earthquake.

Moana Munro is a librarian specializing in Māori services at Hastings Public Libraries in New Zealand. We spoke to Moana about her life as a librarian focused on the Māori community.

Oxford University Press: How and why did you become a librarian?

Moana Munro: I was never much of a reader as a child and didn’t enter a library until my mid 30s when I had a BA to study towards. Twelve years later, here I am working as a librarian with an emphasis on Māori services, or Kaitiakipukapuka Māori. I felt it was important to offer an indigenous viewpoint, within a Western-driven service. Like many indigenous nations, colonization has taken its toll, with a loss of cultural identity, loss of land, urbanization with an associated loss of traditional tribal connections, and Te Reo Māori (Māori language) sidelined.

I wanted to make a difference and support a growing shift to acknowledging and reclaiming Māori language, history, traditions and culture. Meeting new people every day is always a pleasure. Helping people toward a better understanding of their Māori ancestry is also really rewarding.

OUP: How do you feel your work at the libraries benefits the Māori culture in the Hastings area?

MM: There’s a huge variety of tasks in the work I do, assisting people from all walks of life who are interested in finding out about Māori. People don’t want a know-it-all specialist; they want someone who can point them in the right direction and share a heartfelt experience. It is important to stay relevant as a librarian; there are so many new resources. A push to learn Te Reo Māori has produced many more websites and publications that we can assist our customers with.

We have a wide collection of literature which explores all things Māori, including many out-of-print books which can only be read in the library. Emphasis is given to any material of a local nature, particularly Ngāti Kahungunu (a Māori tribe).

No two days are the same and interruptions are frequent, but over the years I have come to cope by maintaining connections with the community and by calling upon some traditional Māori principles, including Te Reo Māori (Māori language), whakapapa (Māori ancestry), manaakitanga (traditional Māori hospitality), wairuatanga (spirituality), kotahitanga (working together) and kiatiakitanga (guardianship). This plus common sense usually produces good results.

OUP: How do you engage with the local community?

Image credit: “Storytime at Pou” by Moana Munro. Used with permission.

Image credit: “Storytime at Pou” by Moana Munro. Used with permission.MM: Due to my work as a Kaitiakipukapuka Māori, I have made many connections with local iwi (tribal groups) and their marae (community spaces). There is a growing awareness that libraries are not just about books; they are community spaces where people can share, learn, and engage with each other. Supplying free Internet access has brought in many people from all cultures who may once have seen libraries as a particularly Western resource.

The uptake has been huge and our libraries have never been busier. As library staff we have all had to upskill in many unexpected and challenging directions to meet the needs of the community and provide something of value. Keeping things lively and vibrant is key. We host all kinds of community groups, from knitters to computer gamers, creative writers to artists, makerspaces and even children’s parties. This, as well as offering space for people to meet in a safe, non-judgemental environment (including social workers and parole officers), has helped encourage more people to see the value in their library.

I also like to get out into the community and engage with people on their own turf. One council initiative in which I am involved is the Street by Street programme. We visit at-risk streets in poor neighbourhoods to tell them about services that can help them, including libraries. We listen to their stories to see how we can help.

We are currently developing an annual schedule of Māori focused programming. We run Te Reo Māori events parallel to other programmes, particularly at times that are significant to Māori , for example Matariki. This is the winter solstice, sometimes known as Māori New Year. We include stories about Matariki for our preschool ‘story time’ events, and crafts in our after-school programmes. Each library has a Matariki display. Our reading challenge has been a great success; encouraging children to read books for which they receive stamps on a pizza card which can then be redeemed at a local pizza outlet. The children can read in English or Te Reo.

OUP: Outside the library you have Ngā Pou, a powerful installation of large, carved statues. Can you tell us a bit about it?

MM: On 26 July 2013, Hastings District Council and Ngā Marae o Heretaunga worked together to install Ngā Pou o Heretaunga as a heritage statement right in the centre of town, conveniently at the forefront of this library. Standing as Kaitiaki (guardians) are 19 Tupuna Pou (ancestral posts). Welcoming people, locals and visitors, each Tupuna Pou faces towards their affiliated marae. The whakakairo (ornate patterns) tell their stories.

OUP: It was recently Māori language week, “Te Wiki o Te Reo Māori” – what events did you put on for this?

MM: We read stories to children in Te Reo Māori sang songs and did crafts. We also had Māori language displays and featured Te Reo in our social media. It has been rewarding to see several of our staff taking advantage of council-sponsored courses in Te Reo also.

OUP: Finally, a bit about your reading preferences! What book are you reading at the moment?

MM: I am reading a book called Ka whawhai tonu matou (struggle without end). It is the first history of Māori by a Māori writer. It is by Ranganui Walker, who is a favourite author of mine.

Featured image credit: “Pou” by Moana Munro. Used with permission.

The post Life as a librarian in the Māori community appeared first on OUPblog.

January 9, 2019

On Robin and robin

“Then the Bi-Coloured-Python-Rock-Snake scuffled down from the bank and said: ‘My young friend, if you do not now, immediately and instantly, pull as hard as ever you can, it is my opinion that your acquaintance in the large-pattern leather ulster’(and by this he meant the Crocodile) ‘will jerk you into yonder limpid stream before you can say Jack Robinson’. This is the way Bi-Coloured-Python-Rock-Snakes always talk.” Alas, my students have never read Kipling’s Just So Stories and don’t know how the Elephant’s Child got its trunk. Unlike them, I have known this story since my early childhood, but only decades later did I understand the joke. Of course, the Python mixed such pompous language with slang and used “reduplication” (immediately and instantly) because it was bi-colored! From this tale I learned the phrase about Jack Robinson, and I have never met anyone who does not understand it. Among other things, there was an amusing comment on that gentleman in the post for December 12, 2018.

Also, on March 8, 2017, I wrote about Tom, Dick, Harry, and a few other heroes of our idioms. Some characters (for example, Hobson of Hobson’s choice) had prototypes. But what do we know about most of the others? Poor Betty Martin (all my eye and Betty Martin “nonsense!”) has been researched high and low and roundabout, but, in all probability, she never existed. Dick, Jack, and many other similar names are so common that looking for the men behind them holds out little promise (yet Dick’s hatband, for example, has been discussed with some success).

Place names may also give us pause. Take, for example, all of a motion, like a Mulfra toad on a hot showl [that is, shovel]. Mulfra is in Cornwall, but what is so peculiar about its toads? Who was there so cruel to animals as to put toads, all the superstitions notwithstanding, on hot shovels? In Pembrokeshire West (Wales), when an infant grows very fast, they say (or said in the middle of the nineteenth century) that it gains like Matty Murray’s money. I tried and failed to discover the story behind that simile. Finally, take as wise as Waltham’s calf. Yes, I know: that idiot of a calf ran nine miles to suck a bull, and its fame predates Shakespeare. But who was Waltham, the calf’s owner?

This is a shovel-nosed toad. Did its existence inspire the inhabitants of Mulfra? Image credit: Triprion petasatus by Maximilian Paradiz. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

This is a shovel-nosed toad. Did its existence inspire the inhabitants of Mulfra? Image credit: Triprion petasatus by Maximilian Paradiz. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Such phrases are countless, and they are not specific to English. In Russian, a certain Sidor (the name rhymes with consider), another animal hater, had a goat, and it was beaten so mercilessly that the act passed into a proverb. The plot thickens with Kuz’ka (the diminutive of Kuz’ma, stress on ma). His mother was a regular termagant. To show one Kuz’ka’s mother means “to treat someone with extreme severity.” By contrast, at Malan’ya wedding there was an overabundance of food; hence the idiom to cook as though for Malan’ya’s wedding. Finally, the otherwise insignificant Makar (the name rhymes with cigar) drove his calves so far that a more distant place does not exist. What folklore or reality gave rise to those sayings?

Who would even think of abusing such a goat? Image credit: White Goat Kid Animal by MabelAmber. CC0 via Pixabay.

Who would even think of abusing such a goat? Image credit: White Goat Kid Animal by MabelAmber. CC0 via Pixabay.The recent exchange about the mysterious Jack Robinson made me think of Robin Hood, the hero not only of ballads but also of a few idioms. One of them is to sell Robin Hood’s pennyworths. Thomas Fuller (1608-1661) wrote History or the Worthies of England, a huge but entertaining book, very patriotic and in some places fiercely partisan. It appeared posthumously (1662) and is now available online. Fuller gave the following most uncomplimentary explanation (it will be found on p. 315): “To sell Robin Hood’s pennyworth. It is spoken of things sold under half their value; or, if you will, half sold, half given. Robin Hood came lightly by his ware, and lightly parted therewith; so that he could afford the length of his Bow for a yard of Velvet. Whithersoever he came, he carried a fair along with him, chapmen crowding to buy his stolen commodities. But seeing the receiver is as bad as the thief, and such buyers as bad as receivers, the cheap pennyworths of plundered goods may in fine prove dear enough to their consciences.” According to an old song: “All men said, it became me well, / And Robin Hood’s penny worth I did sell.” Later, a good pennyworth turned into an idiom, with no mention of Robin Hood left.

John Heywood, another great collector, wrote in his book of proverbs (1562; I’ll retain his spelling): “Tales of Robyn Hode are good for fooles.” I know and also remember that “many talk of Robin Hood that never shot in his bow,” but will nevertheless continue. I A few sayings seem to be still alive, at least in the northern counties, traditionally connected with Robin Hood. Thus, a cold wind during a thaw is called a Robin Hood wind, because Robin Hood was said to bear any wind but a thaw wind. It is indeed a piercing wind, and Robin Hood, as well as his merry men, lived in the open and, naturally, suffered from bad weather. “One correspondent of the Manchester City News suggests that the expression belongs originally to the neighborhood of Rochdale, and refers to the bitter north and east winds that come from the direction of Blackstone Edge, a predominant feature of which hill is Robin Hood’s Bed” (Notes and Queries, Series 11, vol. X, 1922, p. 378).

Kuz’ka’s mother. Image credit: Baba Yaga by Koka (1916) by Кока Б-уа, 10 лет. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Kuz’ka’s mother. Image credit: Baba Yaga by Koka (1916) by Кока Б-уа, 10 лет. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.There once existed the proverbial saying to go all round Robin Hood’s barn, that is, “to go all over the place.” (“I must have gone all round Robin Hood’s barn before I lighted upon the place” or “Where have you been today? –All round Robin Hood’s barn! I have been all about the country, first here, and then there.”) The idiom still seems to be known. As early as 1878, an explanation was given, which I find repeated on the Internet and in at least one reliable modern book. The gist of the explanation is that Robin Hood had no barn; consequently, the ironic phrase meant walking all the way around the cornfields in his district.

Perhaps so, but I have some doubts about this etymology. In any case, I have run into another one. As early as 1559, William Cunningham brought out a book titled The Cosmographical Glasse…, in which he referred to Robin hodes (sic) miles, such miles being several times the ordinary length. Hence to go round by Robin Hood’s barn may suggest the longest way around. The reference to the fields is perhaps not implausible, but Robin Hood lived in the forest, and nothing suggests his proximity to any fields.

Let me finish with a sixteenth-century greeting: “Good even, good Robin Hood!” and promise a continuation next week.

Featured image credit: Illustration at p. 73 in Just So Stories (c1912) by Kipling, Rudyard, Gleeson, Joseph M. (Joseph Michael), or Bransom, Paul, 1885- (ill.). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post On Robin and robin appeared first on OUPblog.

January 8, 2019

A new geological epoch demands a new politics

Young people have become increasingly vocal in castigating older generations for their failure to act on climate change. University students are at the forefront of campaigns to divest from fossil fuels. A group of 21 young Americans launched a high-profile court case against the US government to pursue a legal right to a stable climate. And the School Strike for Climate initiative launched by fifteen-year-old Swedish student Greta Thunberg has attracted worldwide attention.

At the UN climate change conference in December 2018, Thunberg delivered a scathing message: “we can’t save the world by playing by the rules. Because the rules have to be changed.”

What has got the world into this predicament, what kind of change is needed, and how can it be achieved?

Humanity now exerts such a pervasive influence over the Earth’s life-support systems that we have entered a new geological epoch: the Anthropocene. A Great Acceleration in global production and consumption since the mid-20th century has brought human-induced climate change, large-scale deforestation and plummeting biodiversity.

The Anthropocene brings renewed instability to the Earth system—in contrast to the unusually stable Holocene epoch of the last 12,000 years. Without radical changes to the ways in which we produce energy, feed ourselves, and meet other basic needs, the Earth could reach dangerous tipping points including multi-metre sea-level rise and the collapse of globally significant ecosystems such as the Amazon rainforest.

The scale of the change required to reduce these risks poses unprecedented political challenges. Many of our core institutions—from nation-states to capitalist markets—emerged years ago, enabling them to ignore the ecological degradation they were causing.

Some of these institutions have helped to achieve remarkable progress. Nevertheless, these institutions—from markets that ignore environmental impacts to governments that rely on unsustainable economic activity to maintain their authority—remain stuck in what we call “pathological path dependencies.” These path dependencies decouple human institutions from the Earth system by systematically repressing information about ecological conditions and prioritizing narrow economic concerns.

How can pathological path dependencies be broken? Institutions must develop ecological reflexivity: a capacity to question their own core commitments, and if necessary change themselves, while listening and responding effectively to signals from the Earth system.

To cultivate ecological reflexivity we must confront a core paradox for institutional design in an ever-changing Earth system, no fixed model of governance is appropriate for all time. Institutions must be flexible enough to respond to changing environmental and social conditions, while stable enough to provide a framework for long-term protection of shared interests.

We call this kind of institution a “living framework.” The term calls to mind the idea of a living document that is updated over time. It also suggests the idea of a framework for living, that is, for flourishing under unstable conditions.

Achieving the reflexivity that is necessary also requires dismantling barriers to reflexive governance, including government subsidies for unsustainable practices and the ability of vested interests to undermine progressive reform. And it requires empowering agents to rethink what core societal values—such as justice, democracy, and sustainability—should mean under Anthropocene conditions.

Given that dominant agents such as states, international organizations, and corporations are often stuck in pathological path dependencies, more promising agents might include cities and sub-national governments, scientists and other experts, and those most vulnerable to a damaged Earth system.

Each of these agents has an important role to play, whether shifting dominant discourses in a more ecological direction or cultivating local experiments in sustainable living. But each kind of agent also has important limitations when working in isolation.

To overcome these limitations, societies need to cultivate interactions among agents. The best way of doing so is through democratic practices. Democracy opens up essential spaces for those most affected by environmental change—whether peasants’ movements for climate justice, citizens of small island states, or youth advocates on biodiversity or climate change—to hold decision-makers accountable.

Overcoming the pathological path dependencies that drive ecological degradation will not be easy. But, given that we cannot turn the clock back on the advent of the Anthropocene but must learn how to live with it, finding an antidote to those path dependencies is essential. The antidote, we believe, can be found in cultivating an ecologically reflexive democratic politics.

Feature image credit: “Cave, rock, water and cavern” by Ademir Alves. Public domain via Unsplash.

The post A new geological epoch demands a new politics appeared first on OUPblog.

January 7, 2019

How sibling rivalry impacts politics

Was Ed Miliband right to stand against his brother David for the leadership of the Labour party in 2010? Or should he have stepped aside to give his elder brother a clear run? There was much media debate over his decision to challenge David, and relations between the brothers have remained cool and distant to this day. Half a century earlier, John Kennedy and his brothers Robert and Ted were all viewed as potential American presidential candidates. But Robert waited until after his elder brother was dead, and no one pressed Ted’s claims until Robert was dead too. The rights of seniority were strictly upheld.

Throughout history, sibling rivalry has been as familiar as mutual love and support. Clashes of personality and competition for parental attention have always stirred passions. The Book of Genesis describes how the rivalry between Cain and Abel sprang from Cain’s resentment that God favoured his younger brother. The very first murder in history, a case of fratricide, was over the rights of the first-born. Gender has proved an equally problematic issue, with a marked preference for sons still common in many parts of the world today. In Britain, for almost a thousand years, the royal succession has been governed by both gender and birth-order. Sons succeeded according to age, with the rights of daughters recognised, very grudgingly, only from the mid-Tudor period. The story of Henry VIII’s children underlines the strength of these conventions. His son Edward was only nine at his father’s death, but it was accepted that a male child must take precedence over adult half-sisters. The three half-siblings had little love for another, and when Protestant Edward died at fifteen he tried to bar the Catholic Mary from the succession. Yet in the event, even most Protestants accepted that Mary should be next in line, rather than her younger half-sister Elizabeth (a Protestant) or Lady Jane Grey. Two years later Mary seriously considered executing Elizabeth, reminding us how bitter sibling hatreds can be in either sex. In the next century, it was the conventions of royal succession that triggered the so-called Glorious Revolution. In 1688 James II, a Catholic convert, fathered a baby boy (later to become the Old Pretender), who immediately took precedence over his two adult half-sisters, who were both Protestants. The fear of Catholic and arbitrary rule stretching far into the future proved more than the political nation could accept. The rules of succession have now been changed to enshrine gender equality. But the principle of seniority still applies—and with the Queen’s eldest child and grandchild both male, it will be many years before a royal princess takes precedence over a younger prince.

Image credit: Robert Kennedy, Ted Kennedy, John Kennedy. Photo taken by Cecil (Cecil William) Stoughton. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: Robert Kennedy, Ted Kennedy, John Kennedy. Photo taken by Cecil (Cecil William) Stoughton. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Is it a natural human instinct to privilege the first-born? It has not in fact been a universal practice. Some societies have favoured the youngest child, or given them all equal rights. In Anglo-Saxon times, it was often the ablest son rather than the eldest who took the crown, sometimes after a Darwinian struggle. But for centuries, English landed estates and titles passed to the eldest son, which families saw as the best way to preserve their estates intact down the generations. Younger sons were often bitterly resentful. It was convenient for families to have ‘an heir and spare’, but how was the spare to live, and what was he to do? And if the eldest son was irresponsible or not very bright, would it not be better to transfer the inheritance to a more capable younger brother? Such issues were fiercely debated in families, in print, and on the stage. Shakespeare explores the rights and responsibilities of older and younger sons in As You Like It, and several playwrights, including the female spy and writer Aphra Behn, addressed the issue of disinheriting an unsuitable heir.

Social values have changed greatly since Shakespeare’s time. And against the Milibands’ rivalry we can set the close bond between Serena and Venus Williams, all the more impressive given the younger sister’s more glittering career. Yet sibling issues still have resonance today. The nation celebrated Prince Harry’s wedding, but what role will be found for another heir’s spare?

Featured image credit: The Family of Henry VIII: An Allegory of the Tudor Succession. Attributed to Lucas de Heere. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post How sibling rivalry impacts politics appeared first on OUPblog.

January 5, 2019

How women really got the vote

In 2018 we commemorated property-owning women over the age of 30 getting the vote in the United Kingdom. Two years later we will mark 100 years since all women received the vote in the United States.

These are important parliamentary milestones but the lauding of campaigners has given priority to organised women’s movements in gaining the vote. This edges women’s suffrage off the main stage of world politics and makes it a pressure group issue; interesting enough in its way, but of no great consequence in the halls of power.

This emphasis on campaigners, whether militant or constitutional, takes away from the more profound change wrought when women got the vote.

In international terms, enfranchisement in the UK and US was no great advance: seven nations had enfranchised women in the years before 1918; 20 countries in the years before 1920. At the start of 1893, no women had the vote for a national parliament anywhere in the world. By 1963 almost all women had the vote, whatever political system they lived under, and it was considered a mark of backwardness if a nation had not enfranchised women. What is evident here is not a national movement dictated by local campaigns, but an international gender revolution.

The most important date is 1949, when the populous nations of China, India and Indonesia enfranchised women; that was 40 per cent of the world’s female population.

What was driving these enfranchisements? The great movements of women’s suffrage, where tens of nations enfranchised in a few years, are associated with national solidarity and re-organisation. This holds true from revolutionary Russia through war-shocked Europe and North America to the revolutions in India and China, to the emergent nations in Africa up to the tentative democracies in Arabian states during the War on Terror.

The lobbying, demonstrating, rallying, letter writing, and perhaps even militancy of women’s suffragists and their allies helped to a greater or lesser degree; but the most important factor in women’s gaining the right to vote was the re-evaluation of nationhood in terms of citizenship. This happened through great national upheavals.

The existence of an organised feminist movement was a generally helpful but not essential factor. In some countries (notably the US) vigorous feminist organisations deterred erstwhile supporters by militancy or by unrealistic proposals as to what the vote would achieve in such fields as sex regulation and alcohol prohibition. In some countries the women’s vote was granted with no major feminist agitation. In Norway the suffrage movement was feeble – though the women’s vote was still granted there earlier than in Holland with its massive suffrage movement. This is not to say suffrage movements were uninfluential, but other factors were more important; American suffrage campaigner Carrie Chapman Catt lamented that it seemed “the better the campaign, the more certain that suffrage would be defeated.” Sometimes they just stirred up the opposition.

While organisations and individuals made real contributions, particularly in setting the terms for enfranchisement and keeping the issue in the public mind, mega-national issues played a greater part. The most important factors making for women’s suffrage were national crises such as war or nationalist uprisings (often, of course, happening at the same time). The first great bulk of countries enfranchised women during or after the First World War regardless of whether they were on the winning or losing side, or even combatants. A struggle for national self-determination such as that undertaken by Finland and India made for an ultimately painless enfranchisement for women. Invasion and civil war had the same effect in China. There were countries in which there was no association with war, notably the first enfranchisements in New Zealand and Australia, though these were still a matter of national self-definition.

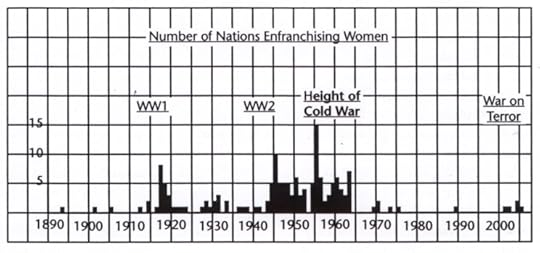

Graph showing when nations introduced votes for women. From Jad Adams, Women and the Vote: A World History (OUP, 2016).

Graph showing when nations introduced votes for women. From Jad Adams, Women and the Vote: A World History (OUP, 2016).Plotted as a graph, the world picture of women’s suffrage shows rises and falls in alignment with the great wars of the twentieth century: a close relationship exists between the end of the First and Second World Wars and the number of enfranchisements of women in different nations.

There is a pronounced but less clear relationship with the height of the Cold War in the late 1950s and early 1960s when a large number of new nations enfranchised women. In the last phase, the relationship of the global War on Terror with late enfranchisements of women in Arab states is inescapable. Enfranchisements between wars are seen to be slow and sporadic, mere dots on the graph of women’s enfranchisements, compared with the solid blocks of nations that cluster round the periods of war.

The repositioning of women’s suffrage in terms of national identity, nationalist movements, and war gives a perspective that puts gender at the heart of national and international politics.

Featured image credit: Detail from a German poster for Women’s Day, March 8, 1914, demanding voting rights for women. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post How women really got the vote appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers