Oxford University Press's Blog, page 204

January 30, 2019

The last shot at “robin”

What else is there to say about robin? Should I mention the fact that “two Robin Redbreasts built their nest within a hollow tree” and raised a family there? Those who grew up with Mother Goose know the touching story by heart. (Fewer and fewer students I teach have ever heard those poems and are amused when I quote them.) Incidentally, the fact that people coined the phrase robin redbreast shows how vague (“non-informative”) the word robin was. No one needs “a supplement” to woodpecker, swallow, or sparrow. But if rob– was a generic root that could denote anyone from a sheep to a seal, robin, even with a suffix, did need reinforcement.

Robin Goodfellow, mentioned and even illustrated last week, should not surprise us either, because the names of venomous creatures (spiders, among them) and monsters often have the same root or are even homonymous: compare bug, the verb to bug, and bugaboo. The existence of Robin Hood is dubious, to say the least, but the choice of the name (Robin) for a legendary character is typical. Also don’t forget Robin the Bobbin, who ate more meat than fourscore men, along with a church and a steeple, and all the good people, but complained that his stomach was not full. He may shed no light on my story, but here is another monster, and the root (rob-), whose existence I defended last week (January 16, 2019), is equally omnivorous. There also was Robbin-a-bobbin/ He bent his bow, / Shot at a pigeon/ And killed a crow.” The experience of many an etymologist is similar (see the title of the present post).

I will finish this cycle by saying a few words about the phrase round robin. In 1536, it was applied to a sacramental wafer and seems to have meant “a piece of bread; cookie; pancake.” Frank Chance, one the most insightful etymologists of the nineteenth century, suggested that robin is here a specific use of Robin, like Jack in flapjack “pancake.” As late as 1897, robin rolls were sold in Oxford. (Or are they still? I would be grateful for some information on this subject.) Perhaps a baker named Robin was the originator of some such dainty. In today’s Facebook, I found numerous women at Robin Roll; Robin Rolls is their next-door neighbor. I don’t know how many common personal names have given rise to the names of dishes and beverages, but charlotte and sandwich are two of them, and martini may be another. (I of course don’t mean the likes of beef stroganoff.)

Are these the original round robins? Image credit: Round Robin image by Paul lee6977. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Are these the original round robins? Image credit: Round Robin image by Paul lee6977. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Naturally, we are most interested in the origin of round robin “circular petition.” It seems that that usage originated in the British navy. In 1802, Charles James, the author of A New and Enlarged Military Dictionary…, explained the phrase as “a corruption of ruban rond.” Of course, he may have had predecessors. In any case, this derivation has been repeated in numerous sources; even the usually cautious Wikipedia cites it. Ruban rond figured in Webster until 1864. C. A. F. Mahn, the first reasonable editor of Noah Webster’s etymologies, left the phrase without any explanation. But in 1880, French rond + ruban reappeared there with perhaps, added to be on the safe side, and stayed there until the famous third edition (1961), when it was again expunged.

The first edition of the OED left round robin without any explanation (just cited the examples), The Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology stated that the reference to robin remains undiscovered, and the OED online only states that the phrase was probably coined by sailors. Not a single thick dictionary of the last fifty years offers even a tentative etymology. Obviously, the French source should have been ruban rond, but Engl. robin round has never existed. To remedy the situation, some old dictionaries referred to the spurious French phrase rond ruban, a poisonous plant on the soil of English etymology, as James A. H. Murray might have put it (he was fond of such memorable expressions).

French ruban rond is a ghost word, and for that reason English could not have adapted it for its use. But even if it ever turns up in French texts, it will have to be understood as a borrowing from English sailors, refashioned after ruban rouge, ruban bleu (ribbons for orders), and the like. There was an attempt to connect robin in round robin with roband “short length of rope yarn or cord for lashing sails to yards,” formerly called robbin or robin. However, round roband, that is, “round ribbon,” has not been attested either.

I am aware of only one more conjecture about the history of round robin. Richard Stephen Charnock, a dialectologist and an active student of proper and place names, wrote countless notes on the etymology of English words, few of which have value. In 1889, Trübner and Co. brought out his book Nuces Etymologicae (that is, approximately “Keys to Etymology”). In the introduction, he promised to correct the mistakes of many of his contemporaries. Among other things, he suggested that round robin is “more probably from round ribbon.” This was a wild guess, and no one remembers it.

Both are round robins, though the cigar fish is not at all round. Image credit (top to bottom): Fishing Frog by Hamilton, Robert (1866) British Fishes, Part I, Naturalist’s Library, vol. 36, London: Chatto and Windus. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons / Round Robin or Cigar-Fish by Goode, George Brown (1884) Fisheries and Fishery Industries of the United States: Section I, Natural History of Useful Aquatic Animals, Plates, Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Both are round robins, though the cigar fish is not at all round. Image credit (top to bottom): Fishing Frog by Hamilton, Robert (1866) British Fishes, Part I, Naturalist’s Library, vol. 36, London: Chatto and Windus. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons / Round Robin or Cigar-Fish by Goode, George Brown (1884) Fisheries and Fishery Industries of the United States: Section I, Natural History of Useful Aquatic Animals, Plates, Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.It does not seem likely that we’ll ever know who and under what circumstances coined the funny phrase round robin, but perhaps it is more reasonable not to separate round robin “circular petition” from round robin “pancake; cookie.” The technical sense (“hood” and the like; Robin Hood!) reinforces the idea that a round robin is simply a round object. Note the senses of round robin, as they appear in The Century Dictionary: “pancake; a kind of ruff, apparently the smaller ruff of the latter part of the sixteenth century; same a cigar fish; the angler Lophius piscatorius” (we are again in the animal kingdom), and then the document that interests us. The OED cites many more technical senses.

Perhaps the local meaning of round robin “pancake” was first applied to the document by natives of Devonshire. It has been pointed out that that county had been well represented in the navy.

Featured image credit: Image from page 64 of “The Boyd Smith Mother Goose” (1920) by Internet Archive Book Images. Public Domain via Flickr.

The post The last shot at “robin” appeared first on OUPblog.

January 29, 2019

Happy sesquicentennial to the periodic table of the elements

The periodic table turns 150 years old in the year 2019, which has been appropriately designated as the International Year of the Periodic Table by the UNESCO Organization. To many scientists the periodic table serves as an occasional point of reference, one that is generally considered to be something of a closed book. Of course they, and the general public, have become aware of the ever-growing list of new elements that need to be accommodated into the table, but surely the main structure and principles of the table must be fully understood by now?

Well it turns out that this is not the case. In this blog I will touch on just some of the loose ends in the study of the periodic table. The first has to do with the sheer number of periodic tables that have appeared, either in print or on the Internet, in the 150 years that have elapsed since the Russian chemist Dmitri Mendeleev first published a mature version of the table in 1869. There have been over 1000 such tables, although some of them are best referred to by the more general term periodic system, since they come in all shapes and sizes other than table forms, with some of them being 3-D representations.

Given that there are so many periodic systems on offer it is natural to ask whether there might be one ultimate periodic system that captures the relationship between the elements most accurately. This relationship that lies at the basis of the periodic system is a rather simple one. First the atoms of all the elements are arranged in a sequence according to how many protons are present in their nuclei. This gives a sequence of 118 different atoms for the 118 different elements, according to the present count. Secondly, one considers the properties of these elements as one moves through the sequence, to reveal a remarkable phenomenon known as chemical periodicity.

It is as though the properties of chemical elements recur periodically every so often, in much the same way that the notes on a keyboard recur periodically after each octave. In the case of musical notes the recurrence can easily be appreciated by most people, but it is quite difficult to explain in what way the notes represent a recurrence. In technical terms moving up an octave on a keyboard, or any other instrument for that matter, represents a doubling in the frequency of the sound.

Octaves in the case of elements, if we can call them so, are not quite like that. There is no single property which shows a doubling each time we encounter a recurrence. Nevertheless there are some intriguing patterns that emerge among the elements that are chemically ‘similar’. For example consider the number of protons in the nuclei of the atoms of lithium atom (3), sodium (11) and potassium (19). An atom of sodium has precisely the average number of protons among the two flanking elements (3 + 19)/2 = 11. This kind of triad relationship occurs all over the periodic table. In fact the discovery of such triads among groups of three similar elements predates the discovery of the mature periodic table by about 50 years.

Now most of the periodic tables that have been proposed display such triad relationships and so we must look elsewhere in order to find an optimal table, assuming that such an object actually exists. One possible course of action might be to consult the official international governing body of chemistry or IUPAC (International Union of Pure & Applied Chemistry) to see what their recommendation might be. The IUPAC organization has a rather odd policy when it comes to the periodic table of the elements. The official position is that they do not support any particular form of the periodic table. Nevertheless in the IUPAC literature one can find many instances of a version of the periodic table that is sometimes even labeled as “IUPAC periodic table”.

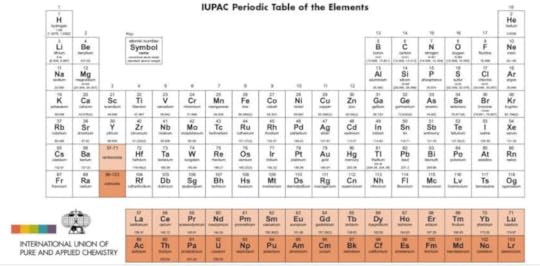

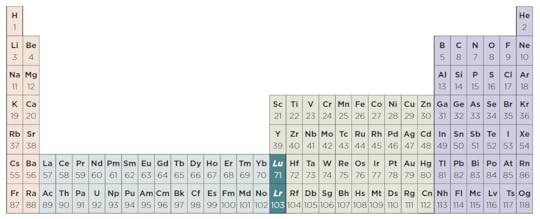

And if that’s not bad enough, the version that IUPAC frequently publishes, as shown in figure 1, is rather unsatisfactory for reasons that I will now explain.

Figure 1. IUPAC periodic table

Figure 1. IUPAC periodic tableConsider the third column from the left, or as it is aptly known, group 3 of the periodic table. Unlike all other columns of the table this group appears to contain just two elements, scandium and yttrium, shown by their symbols Sc and Y. If you look closely at the numbers in the two shaded spaces below these two elements you will see a range of values, such as 57-71 in the first case. This occurs because the elements numbered from 57 to 71 inclusive are assumed to fit in-between element 56 and 72, naturally enough. The reason why the two sequences of shaded elements are shown below the main body of the main table in a mysteriously detached manner is purely pragmatic.

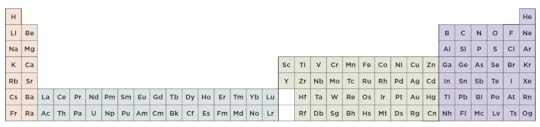

Figure 2. The 32-column version of the periodic table published by IUPAC

Figure 2. The 32-column version of the periodic table published by IUPACIt’s because doing otherwise, would produce a table that is perhaps too wide as shown in figure 2. But in a sense the far-too-wide table is more correct, since it avoids any breaks in the sequence of elements and avoids the impression that the shaded elements somehow have a different status from all others or that they represent something of an afterthought. But switching to such a wide table would not solve the problem even if IUPAC were to endorse doing so. This is because the table in figure 2 still shows only two elements in group 3 of the table and because it would imply that there are 15 so-called f-orbitals in each atom, whereas quantum mechanics, that provides the underlying explanation for the periodic table, suggests that there should be 14 of them.

OK, you might say, we can easily fix the problem by tweaking the periodic table slightly to produce figure 3. As far as I can see, from a lifetime of studying and writing about the periodic table, figure 3 is precisely the optimal periodic table that IUPAC should be publishing and even endorsing officially. This table restores the notion of 14 f-orbital elements as well as removing the anomaly whereby group 3 only contained 2 elements, since it now contains four, including lutetium and lawrencium.

Figure 3. The optimal periodic table?

Figure 3. The optimal periodic table?Why will IUPAC not see things quite so simply? That’s a big and complicated question which I can only touch upon here. Like many organizations with rules and regulations, when push comes to shove, decisions are made by committees. As a result, the science takes second place while the various committee members vie with each other and ultimately take votes on what periodic table they should publish. Unfortunately, science is not like elections for presidents or prime ministers, where voting is the appropriate channel for picking a winner. In science there is still something called the truth of the matter, which can be arrived at by weighing up all the evidence. The unfortunate situation is that IUPAC cannot yet be relied upon to inform us of the truth of the matter concerning the periodic table. In this respect there is indeed an analogy with the political realm and whether we can rely on what politicians tell us.

Featured image credit: Retro style chemical science by Geoffrey Whiteway. Public Domain via Stockvault.

The post Happy sesquicentennial to the periodic table of the elements appeared first on OUPblog.

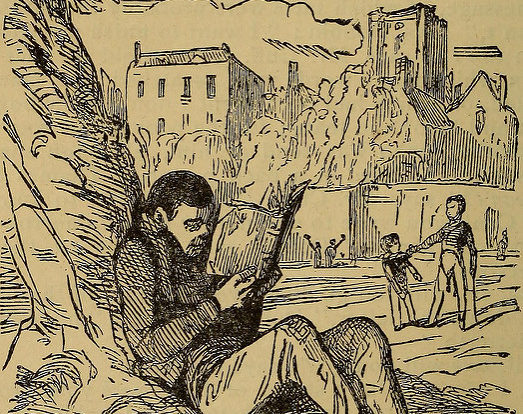

The challenges of representing history in comic book form

When I wrote my first graphic history, based on the 1876 court transcript of a West African woman who was wrongfully enslaved and took her case to court, in 2012, I received a diverse and gratifying range of feedback from my fellow historians. Their response was overwhelmingly but not universally positive. One colleague in particular tried to explain to me why she regretted the emergence of comic book style histories. “It’s too bad students just don’t read any more”, she sighed, implying that comic books shouldn’t be taken seriously. I was tempted to respond that opening the pages of a comic book was every bit as much an act of reading as turning the pages of a textbook or a monograph, but I couldn’t muster an argument in the moment, and actually just responded with a stunned silence.

By now, many readers are familiar with graphic histories, the expression of the history genre within the comic book medium. Graphic histories are a growing segment of comic book publications, with new titles coming out every day and many on display at conferences such as the American Historical Association’s annual meeting. Yet even as recently as 2012, graphic histories were relatively few, and most historians didn’t really think about them.

In the years since, my colleague’s comment has given me a great deal to contemplate. It’s not that I agree with her any more now than I did eight years ago. Rather, I have subsequently come to understand that both historians and creators of graphic histories have a lot of work to do to mutually develop a genre.

Many graphic histories suffer from a deficiency either as comics or as histories. Historians, unfamiliar with graphic novels, often create graphic histories with cramped, text-crowded panels and pages because we lack the skills to let the images do the work. Many comic artists and writers haven’t developed the tools and techniques historians have developed to reflect on the past. Narrative histories created by cartoonists (particularly those common in K-12 education) often lack historical interpretation.

My experience working taught me just how difficult it is to create a graphic history that is both a meaningful interpretation of the past and a masterful employment of the comic form. Despite the fact that I was co-writing my 2012 book with an experienced illustrator, I had a hard time understanding art’s potential to communicate experience as well as to be an explanatory medium.

In time, other historians and teams have since figured out how to make the genre work effectively. The excellent collaboration The Great Hanoi Rat Hunt is a great example of using a comic to create opportunities for readers to do their own interpretive work. This text is particularly significant in its attention to the connection between the graphic narrative and the sources and evidence that informs it. The authors of this book do a masterful job in this volume of making evidence available to the reader in ways that engage the narrative. (Citation is one of the issues that bedevils the graphic history, as there is no convention yet for citing sources in comic form.)

Battlelines: A Graphic History of the Civil War, the result of a collaboration between historian Ari Kelman and artist Jonathan Fetter-Vorm is another brilliant example of the genre. I particularly love the attention this text gives to artifacts of the war – letters, other documents, and objects. These receive loving artistic attention and connection to lived experiences that demonstrates, I think, a real command of the medium, and a minie ball as easily as a letter or newspaper article, each of which then forms the basis for a longer investigation into the human experiences of the conflict.

There are many other graphic histories that remain to be reviewed. Kate Evans’ graphic biography of Rosa Luxemburg, Red Rosa, and Li Kunwu’s autobiographical A Chinese Life are two that I’m itching to put before experts in relevant fields.

Not all graphic histories are great historical interpretations, but some are very good indeed, and can potentially produce an enormous societal impact. A few, like John Lewis, Andrew Aydin, and Nate Powell’s March, or Art Spiegelman’s Maus, have such a wide audience that to ignore them would be a major mistake for a profession striving to stay in touch with a society that needs our intervention more than ever. Their popular appeal may not be enough of a justification for historians to take graphic histories seriously, but combined with their potential as analytical and expressive tools, they demand our attention.

Featured image credit: Comic by Mahdiar Mahmoodi. Public Domain via Unsplash.

The post The challenges of representing history in comic book form appeared first on OUPblog.

January 28, 2019

Why terminology and naming is so important in the LGBTQ community

People with power using terms to belittle those with less power is something familiar to marginalized communities. While some shy away from terms used in this way, others grab them back, telling the world words can’t cow them.

At this point in history, it’s more vital than ever to name ourselves and to reclaim terms that have been used against us as queer-identified people living with mental health conditions. If we do not name ourselves, the door is wide open for others to label us.

Naming is powerful and historically, the power to name has been held by outsiders who designate and marginalize those less powerful as “other.” For example, gay men and lesbians have been called “fags” and “dykes,” and those with mental health issues have been called “crazy,” a word associated with dangerous or violent behavior. Because of this and the current nefarious activities by nationalist governments in many places around the globe, it is crucial to tell our own stories and to create a record of LGBTQ narratives to ensure our own futures.

It is imperative that we explore the evolution of queer identity with regard to mental health, detail experiences that foster resilience and stress-related growth among people, and examine what comes after marginalized sexual orientation and gender identity status is disentangled from their historical association with the concept of mental illness. This is how we can ensure appropriate treatment for our communities.

Self and community are interwoven for many LGBTQ people, including those of us living with mental health conditions. Just as there can be stigma and rejection against LGBTQ people in straight communities, LGBTQ people can experience repudiation in mental health communities. Conversely, people with mental illness can experience rejection in LGBTQ communities. Unfortunately, membership in one marginalized community doesn’t guarantee acceptance in another.

It’s often said in mental health communities that disclosing status as a person living with a mental health condition is a kind of coming out. For those of us who are queer and living with depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, or other mental health concerns, we’ve got more than enough coming outs.

The Stonewall Rebellion is a touchstone for the modern-day LGBTQ rights movement, though, of course, LGBTQ people have existed throughout history and rebelled in our own ways.

Reclamation in LGBTQ communities has come in many forms. Terminology such as “queer,” “dyke,” “fag,” and even “tranny” has been embraced by different segments of our communities, while some under the LGBTQ umbrella have categorically rejected these words. The pink and black triangles used by the Nazis to identify and shame male homosexuals and “asocials” (including lesbians) in the concentration camps have become queer and feminist symbols of solidarity and strength. The Stonewall Rebellion is a touchstone for the modern-day LGBTQ rights movement, though, of course, LGBTQ people have existed throughout history and rebelled in our own ways. There is no unanimity about reclaiming these, or other, terms. Although the majority often treats us as though we are monolithic, marginalized communities are genuinely diverse; we each have different opinions and experiences. We need to find strength and identity in our own ways and on our own terms.

These days, LGBTQ folks are “queering” traditions and institutions such as marriage, the family, workplaces, monetary systems, literature, art, and much more, including how we discuss and view people living with mental health issues. But claiming “madness” or calling oneself “crazy,” “mad,” “nuts,” or even a “headcase” is still all-too-often frowned upon. To reiterate, a shared characteristic does not necessarily foster agreement among all community members. For some, to snatch back these words as soon as possible extinguishes their negative power; for others, the pain of experiencing a slur is still too raw. Shame and stigma are freighted by well-known studies about the prevalence of mental illness in our communities. Who wants to be a statistic, after all?

By questioning – and then subverting – categories of gender and sexuality, hetero- and cis normativity, and invalid notions about mental health and wellness in our communities, we can (re)create LGBTQ narratives that make sense to and support us and our communities both creatively and honestly. Naming ourselves, with reclaimed terms or new ones, rebuffs shaming and allows us to embrace our entire beings. It can bring our whole selves to life outside of any closet someone might wish for us.

What are your names?

Featured image credit: “Memorial to Homosexuals Persecuted Under Nazism” by Tony Webster. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Why terminology and naming is so important in the LGBTQ community appeared first on OUPblog.

January 25, 2019

Are our fantasies immune from morality?

Immoral fantasies are not uncommon, nor are they necessarily unhealthy. Some are silly and unrealistic, though others can be genuinely disturbing. You might fantasize about kicking your boss in the shins, or having an affair with your best friend’s spouse, or planning the perfect murder. Everyone enjoys a dark little fantasy at some time. Which leads us to wonder, is it ever morally wrong to do so? Or, a better way to put the question, under what conditions is it morally wrong to fantasize about something?

A natural response to these questions is to answer flatly: no. It can never be morally wrong to fantasize about something simply because it is a fantasy. My imagination is not a space where morality intrudes. Rather, what happens in my imagination is my business, and no one else’s moral qualms should have bearing on this most personal space.

Despite this, there are circumstances where there is good reason to be morally concerned with some imaginings even if we still insist that people should be free to do so. The notion of an ethics of imagination falls into the interesting logical space where morality and legality come apart, that realm of morality that lies beyond what can be legislated. It is this same logical space where we find things like the ethical condemnation of a cheating lover (at least, between unmarried lovers). Cheaters cannot be arrested, but they are still jerks. It is not illegal to cheat on a lover, but it is immoral. The same is true for fantasies. We are free to imagine whatever we wish, but some fantasies are morally problematic.

So, when is it morally wrong to imagine something immoral? The short answer is that it is morally wrong to fantasize about something when that fantasy feeds an immoral desire.

Our fantasies feed certain desires for us, typically desires that otherwise go unfulfilled.

The slightly longer answer is this. Our fantasies are often tied to our desires—not always, but often. It is not an accident that we fantasize about the things that we do. If you fantasize about kicking your boss in the shins, it is likely due to some conflict that exists between you and your boss. If you fantasize about having an affair with your best friend’s spouse, it is likely because you fancy your best friend’s spouse. Our fantasies feed certain desires for us, typically desires that otherwise go unfulfilled.

This is particularly true for recurrent fantasies. Some fantasies pop into our heads seemingly unexpectedly. Some pass through our consciousness for a fleeting moment never to return again. Perhaps after an unpleasant conversation with your boss, you momentarily imagine kicking him in the shins. But the feeling passes and you don’t really dwell on the fantasy. Fleeting imaginings like these are not morally worrisome.

Yet, there are other fantasies that we actively return to, develop, and refine. There are some fantasies that one might entertain repeatedly, ones that we truly relish. Why are we drawn again and again to some fantasies but not others? Likely the answer is that there is something about recurrent fantasies that we find genuinely desirable. Fantasies like these are indicative of our desires.

Some things are morally wrong to desire. It is morally wrong to desire to commit an act of murder, or rape, or pedophilia. Of course, it is worse to actually carry out such a desire, but merely possessing the desire is itself morally wrong.

So, if we turn to fantasy to satisfy desires that we cannot otherwise satisfy, and some desires are themselves immoral, then we are doing an injustice to ourselves when we satisfy an immoral desire in our fantasies. By satisfying the desire, we do not rid ourselves of it. Rather, we run the risk of reinforcing the desire—that is, we may cultivate in ourselves a desire for something that we ought not to desire.

The interesting upshot of this philosophically is that fantasy is not immune from morality, despite its separation from reality. The boundaries of morality extend further than we might think—indeed, into thought itself.

Featured image credit: “Light, colour, bright and neon” by Efe Kurnaz. CC0 via Unsplash.

The post Are our fantasies immune from morality? appeared first on OUPblog.

January 23, 2019

A possible humble origin of “robin”

Some syllables seem to do more work than they should. For example, if you look up cob and its phonetic variants (cab ~ cub) in English dictionaries, you will find references to all kinds of big and stout things, round masses (lumps), and “head/top.” Animal names also figure prominently in such lists. In English, cob is the name of a male swan, several fishes, a short-legged variety of horses, and a gull. Similar words are sometimes called cop rather than cob. Many of them are regional, but a few are universally known. German Kopf “head” and Engl. cob(web) come to mind at once.

Cobble (as in cobblestone) is cob with the same suffix –le that we find in needle, handle, cradle, ladle, and a few others. Though one needs an effort in separating –le from the root, it is a real suffix. Cobbler, a Middle English noun, is, surprisingly, “of unknown origin,” with the verb cobble being “abstracted” from it by back formation (like sculpt from sculptor and televise from television). Then there is Old Icelandic kobbi “seal” and Engl. cub. If we search for similar words in the dictionaries of other Germanic languages, we’ll be swamped by kabbe, keb(be), kibbe, and kippe. Some such formations occurred in Middle English and then died out.

No one knows for sure how such words sprang up. They are like mushrooms, rootless and ubiquitous. If they first came into existence as animal names, at least some of them might be pet names (hypocoristic nouns). Perhaps Engl. dog, another noun of undiscovered origin, belongs with such “mushrooms” (see the posts for May 4, 11, and 18, 2016). It is also probable that some words like cob, few of which were recorded early, traveled from language to language, especially between English and Dutch. To enhance our confusion, we may add Engl. cup to this list. The point of this introduction is that Germanic teems with the monosyllables that do not form a family but rather obviously belong together. The story of rob– is not different from that of cub ~ cob: again a welter of similar formations without a clear-cut pedigree.

Robert Goodfellow. Image credit: Midsummer Puck Flying by Smatprt. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Robert Goodfellow. Image credit: Midsummer Puck Flying by Smatprt. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.In Old French, sheep were often called Robin. The Vikings seem to have brought this name to France from their historical home. Modern Icelandic still has robbi “sheep, ram.” Robbi is also the name of “white partridge.” German Robbe means “seal,” and in Norwegian (Nynorsk), robbe “bugaboo” occurs. This word may throw a sidelight on the rare and obsolete Engl. Roblet “a goblin leading people astray in the dark” and Robin Goodfellow. This character, Puck’s double, was especially popular in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, just when the word robin gained ground in England. But this goblin can lead astray even sober and dry-as-dust etymologists. He reminds us of Knecht Ruprecht, St. Nicholas’s German companion, and of hobgoblin, because Hob = Rob, and of hobbledehoy. Robert and Robin occupy an important place in folklore. Many must have heard about Robert the Devil and of Meyerbeer’s opera on this plot. French rabouin “devil” may belong here too.

Relatives: etymology and zoology are here at cross-purposes. Image credit (top to bottom): Juvenile Harp Seal by Virginia State Parks. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr / Ikes Bunny by Danni505. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Relatives: etymology and zoology are here at cross-purposes. Image credit (top to bottom): Juvenile Harp Seal by Virginia State Parks. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr / Ikes Bunny by Danni505. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.As we can see, rob-, like kob-, is a productive complex, and, while admiring its fertility, we cannot help remembering rabbit, which appeared in English texts in the fourteenth century as a term of French cuisine. Rabbit supplanted con(e)y, just as robin supplanted ruddock. The origin of rabbit has been the object of long and involved speculation. The hypotheses are many. Some people traced rabbit to Robert, others to French and Flemish. But it seems that we are dealing with parallel formations in several Eurasian languages. When people begin to call all kinds of living creatures from seals to spiders kobbi, robbi, tobbi, boppi, dogga, koppe, loppe, noppe, and the like, linguists have to admit the existence of what has been called primitive creation, and coincidences across languages are bound to occur.

We don’t know how language arose. We cannot even say at what stage a system of signals deserves to be called language. (Think of such phrases as the language of whales, the language of bees, and the like). Serious etymological dictionaries refer words to ancient roots. Non-specialists will find a long list of such Indo-European roots in the supplement to The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language. Here are some examples: ster- “stiff,” ster- “to spread,” ster- “star,” ster- “to rob, steal,” and ster– “barren” (they appear in Engl. stare, strew, star, steal, and stirk “a yearling heifer”). Nine homonymous roots appear under kel-, seven under gher-, five under ker-, and so forth.

Those are reconstructed roots. The role of such units in the formation of words is far from clear. Students of word origins take it more or less for granted that ster-, gher-, ker-, and the rest circulated in some form several thousand years ago. Perhaps they did, but, if so, there is no need to doubt that kob- ~ kab- ~ kub, rob- ~ rab-, nop-, lop-, and their likes existed in the full light of history. The reconstructed roots are the upper class of the “etymological community,” while the kob– ~ rob- ~ nop- ~ lop- rabble constitutes its “lower orders.” They are its plebeians, riff-raff; rag, tag, and bobtail. But those upstarts were vital and unprincipled. Rabbit superseded coney, and robin superseded ruddock. Were not also the respectable ster-, gher, and ker– such before they attained greatness in our dictionaries?

I would venture the hypothesis that robin and perhaps rabbit are similar but much later upstarts, coined perhaps in baby talk, perhaps as jocular forms (in principle, slang). This reconstruction cannot be “proved.” It is doomed to remain an irritating hypothesis. But one thing is obvious. Creativity is not a process that dominated language only in its infancy. It never stops. English speakers are acutely aware of this fact. Slang is born every day, and its origins are usually more than dubious.

Every epoch seems to favor one particular type of emotional word formation. Today, people use their ingenuity, to coin multifarious blends. Most are stillborn creatures, but a few will stay. Blog and motel are among them. Webinar may also survive the present generation. Brexit will be forgotten once the painful divorce comes to an end. In the late Middle Ages, the process of word creation was seemingly dominated by the creation of more and more monosyllables. New words spread easily, acquired suffixes (rob-in; rabb-it even added a French suffix), and began to look like old-timers. After all, two and four legs are equally good. Did it all happen the way I think? We’ll never know: just food for thought.

Featured image credit: Coney Island by Monica PC. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post A possible humble origin of “robin” appeared first on OUPblog.

January 22, 2019

Philosopher of The Month: William James (timeline)

This January the OUP Philosophy team honours the American psychologist and philosopher William James (1842-1910) as their Philosopher of the Month. James is considered one of the most influential figures in the history of modern psychology.

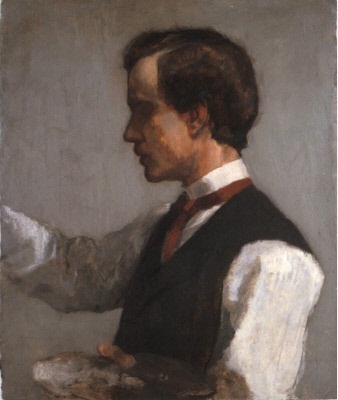

James was born into a wealthy New York family in 1841, the son of a Swedenborg theologian, and the brother of the famous novelist, Henry James. He received a private education at home, and with the family made frequent trips to Europe. At the age of 18 he begun an education as an artist and studied painting with the prominent American artist William Morris Hunt, but subsequently abandoned art. He went on to study chemistry and comparative anatomy at Harvard University before switching to Harvard Medical School in 1864 where he formed a lasting and important friendship with another philosopher, Charles Sanders Pierce. Although he graduated with a medical degree in 1869, he never practiced it.

Throughout his life, James was often subject to depressions and ill health. In 1870 he suffered a nervous breakdown which made him incapable of any work. In 1872, after his health had improved, he was offered the post to teach anatomy and physiology at Harvard by its president, Charles Eliot. In 1870 he expanded his teaching to include psychology and was instrumental in establishing the university’s psychology department and the first American experimental psychology laboratory. He then taught philosophy in 1879 and was appointed Professor of Philosophy at Harvard in 1885.

Image Credit: Portrait of William James by John La Farge, circa 1859, National Gallery. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image Credit: Portrait of William James by John La Farge, circa 1859, National Gallery. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.James’ first major and ground-breaking work, The Principles of Psychology (1890) in two volumes brings together physiology, experimental psychology, philosophy, elements of pragmatism, and phenomenology. He challenged the established psychological and philosophical thoughts of his day from the associationist school to the Hegelianism school by suggesting that the human experience was characterized by a “stream of consciousness”. He wrote in The Principles of Psychology, “Consciousness…does not appear to itself chopped up in bits…a ‘river’ or ‘stream’ are the metaphors by which it is most naturally described.” He also advanced a new theory of emotions which suggested that emotion follows, rather than causes, its physiological changes. According to him, external events cause bodily changes which we then feel. He asked what would grief be “without its tears, its sobs, its suffocation of the heart, its pang in the breast-bone?” He also discussed emotions in relation to art. These are the “subtler emotions,” which are elicited from the aesthetic properties of the work of art. The book’s ideas drew attention from Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung in Vienna and would influence generations of thinkers in Europe and America from Edmund Husserl, Bertrand Russell, John Dewey, Ludwig Wittgenstein, and James Joyce and it remains one of the great classic texts of modern psychology.

James also wrote an influential work on the philosophy of religion. The Varieties of Religious Experience: a study in human nature (1902) examines different forms of religious experience from the point of view of a psychologist. James discussed human spirituality such as conversion, mystical experiences, and saintliness as well as his conception of the “healthy-mindedness” versus the “sick soul”. This supports his view that direct religious experiences rather than institutional religions form the foundation of religious lives: “the feelings, acts, and experiences of individual men in their solitude, so far as they apprehend themselves to stand in religion to whatever they may consider the divine.” In The Will to Believe (1897), he defended the place of religious beliefs by repudiating evidentialism and arguing that the belief in the divine existence can be justified by the emotional benefits it brings to one’s life. He recognized the role of science but suggested that there are elusive religious experiences which can only be accessed by individual human subjects but not sciences.

Along with Charles Sanders Peirce, James is credited as one of the founders of American pragmatism – a philosophy which holds that a belief or the truth of an idea is to be appraised in terms of its practical consequences, thus rejecting the quest for abstract foundational truths, traditional metaphysics, and absolute idealism. According to James, truth is to be found in concrete experiences and practices, and not in transcendental realities, “the true is only the expedient in the way of our thinking, just as the right is only the expedient in the way of our behaving” (Pragmatism: A New Name for some Old Ways of Thinking, 1907, p. 222). These ideas are fully explored in his best known philosophical works, Pragmatism (1907) and The Meaning of Truth (1909).

By the time of his death in 1910, William James had become a much-esteemed and eminent philosopher and psychologist of the beginning of the twentieth century because of his important contributions to psychology, religion, and philosophy. For more on James’s life and work, browse our interactive timeline below:

Featured image credit:Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts, by coffee. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Philosopher of The Month: William James (timeline) appeared first on OUPblog.

January 21, 2019

The rightful heirs to the British crown: Wales and the sovereignty of Britain

The Mabinogion is a collective name given to eleven medieval Welsh tales found mainly in two manuscripts – the White Book of Rhydderch (c. 1350), and the Red Book of Hergest (dated between 1382 and c.1410). The term is a scribal error for mabinogi, derived from the Welsh word mab meaning ‘son, boy’; its original meaning was probably ‘youth’ or ‘story of youth’, but finally it meant no more than ‘tale’ or ‘story’. The title was popularized in the nineteenth century when Lady Charlotte Guest translated the tales into English. Despite many common themes, the tales were never conceived as an organic group, and are certainly not the work of a single author. Moreover, the ‘authors’ are anonymous, suggesting that there was no sense of ‘ownership’ and that the texts were viewed as part of the collective memory. Their roots lie in oral tradition as they reflect a collaboration between the oral and literary cultures, giving us an intriguing insight into the world of the medieval Welsh storyteller. Performance features such as episodic structure, repetition, verbal formulae, and dialogue are an integral part of their fabric, partly because the ‘authors’ inherited pre-literary modes of narrating, and partly because in a culture where very few could read and write, tales and poems would be performed before a listening audience; even when a text was committed to parchment, one can assume that public readings were the norm. Therefore, the overriding aim of this translation was to convey the performability of The Mabinogion; as such the acoustic dimension was a major consideration.

Their roots lie in oral tradition as they reflect a collaboration between the oral and literary cultures, giving us an intriguing insight into the world of the medieval Welsh storyteller.

The dating and chronology of the tales are problematic – they were probably written down sometime during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, against a background which saw the Welsh struggling to retain their independence in the face of the Anglo-Norman conquest. Although Wales had not developed into a single kingship, it certainly was developing a shared sense of the past, and pride in a common descent from the Britons. The basic concept of medieval Welsh historiography was that the Welsh were the rightful heirs to the sovereignty of Britain; despite invasions by the Romans and the Picts, and despite losing the crown to the Saxons, the Welsh would eventually overcome and a golden age of British rule would be restored. This theme of the loss of Britain is attested in the tale of Lludd and Llefelys which tells of the three ‘plagues’ that threaten the Island of Britain. The Dream of Maxen, on the other hand, tells of the historical Magnus Maximus, proclaimed emperor by his troops in Britain in AD 383; he depletes Britain of her military resources, so leaving the Island at the mercy of foreign invaders and marking the beginning of Wales as a nation according to certain interpretations. Arthur, who came to play a leading role in the development of Welsh identity, is a central figure in five of the Mabinogion tales. The author of Rhonabwy’s Dream has a cynical view of national leaders and kingship as Arthur himself and all his trappings are mocked. The author of How Culhwch won Olwen, on the other hand, sees Arthur as the model of an over-king, holding court in Gelli Wig in Cornwall and heading a band of the strangest warriors ever – men such as Canhastyr Hundred-Hands and Gwiawn Cat-Eye – who, together with Arthur, ensure that Culhwch overcomes his stepmother’s curse and marries Olwen, daughter of Ysbaddaden Chief Giant. In the tales of Peredur son of Efrog, Geraint son of Erbin, and The Lady of the Well, Arthur’s court is relocated at Caerllion on Usk, and Arthur’s role is similar to that found in the continental romances – a passive figure, who leaves adventure to his knights. These are three hybrid texts, typical of a post-colonial world.

With the Four Branches of the Mabinogi we are in a familiar geographical landscape and a society apparently pre-dating any Norman influence. Indeed, the action is located in a pre-Christian Wales, where the main protagonists are mythological figures. Even though it is doubtful whether their significance was understood by a medieval audience, the mythological themes make for fascinating stories: journeys to an otherworld paradise where time stands still and where mortals do not age; the cauldron of rebirth which revives dead warriors; shape-shifting where an unfaithful wife is transformed into an owl. But these are more than mere tales of magic and suspense. All the tales of the Mabinogion provided their audience with ethical dilemmas concerning moral, political and legal issues. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the Four Branches of the Mabinogi – it is they that convey most effectively the appropriate moral behaviour that is essential for a society to survive. In the first three branches, the nature of insult, compensation, and friendship are explored. In the Fourth Branch, however, further considerations are raised. Math, lord of Gwynedd, is not only insulted, but also dishonoured – his virgin foot-holder is raped, and his dignity as a person is attacked. The offenders, his own nephews, are transformed into animals – male and female – and are shamed by having offspring from one another. However, once their punishment is complete, Math forgives them in the spirit of reconciliation. Throughout the Four Branches, therefore, the author conveys a scale of values which he commends to contemporary society, doing so by implication rather than by any direct commentary.

Authors from Tennyson to Tolkien, from Evangeline Walton to Lloyd Alexander have been inspired by The Mabinogion while the tales are still being performed today by professional storytellers – tangible proof of their lasting significance and resonance.

Featured image credit: “Drudwy Branwen” by Anatiomaros. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The rightful heirs to the British crown: Wales and the sovereignty of Britain appeared first on OUPblog.

January 17, 2019

What can history tell us about the future of international relations?

According to Cicero, history is the teacher of life (historia magistra vitae). But it seems fair to say that history has not been the teacher of International Relations. The study of international relations was born 100 years ago to make sense of the European international system, which had just emerged from four years of warfare. Ever since, the field has remained remarkably Eurocentric. Virtually all major theories have been formulated to understand the international system that arose in Europe in the 17th and 18th centuries and expanded to become the first ever global state system in the 19th and the 20th centuries.

At the same time, however, many international relations theories have much wider pretentions. Take the most influential of all such theories, Kenneth Waltz’s neorealism. Waltz’s most general insight is that sustained domination by one power in international relations is a near impossibility because power accumulation in one state triggers efforts at emulation by other states (internal balancing) and the formation of hostile coalitions (external balancing). Waltz derived this insight from the European and later global state system, which for a thousand years has seen repeated attempts of long-term domination fall through due to balancing. But Waltz holds that this generalization applies “through all centuries we can contemplate.” This is neatly illustrated by his famous analogy that “[a]s nature abhors a vacuum, so international politics abhors unbalanced power.”

Recent work in the field suggests that international relations must break its European shackles and enlist historical evidence from other international systems in order to understand where the present multistate system is headed. Since the end of the Cold War scholars have become interested in the very limited attempts to balance US preeminence. They have turned to previous situations of single power dominance (or unipolarity) to investigate if this is a stable outcome in international relations – and if not, what is likely to replace it.

A good example of this scholarship is the edited volume The Balance of Power in World History by Stuart Kaufman, Richard Little, and William Wohlforth, which surveys more than forty different state systems during 7,500 years of world history. This book shows that balanced and unbalanced outcomes have been about equally common over time, and that the European system is exceptional due to the absence of single-power dominance. More generally, the authors conclude that “[u]nipolarity is a normal circumstance in world history.” Indeed, over time most multistate systems have moved in the direction of single-power dominance. This dominance has sometimes lasted for centuries. In one spectacular case, China, universal domination in the form of empire never broke up again. The Chinese imperial state was the product of a conquest that rolled up a previous multistate system – known as the Warring States – which in certain respects seems to have been uncannily similar to the later European system. However, after the unification of China in 221 BC, the area around the Yellow River and the Yantze never relapsed into an anarchic struggle between multiple states.

Image credit: “Trump President USA” by geralt. CC0 via Pixabay.

Image credit: “Trump President USA” by geralt. CC0 via Pixabay.Strong balancing theories – such as Waltz’s neorealism – do not fare well when measured up against something like Chinese history. The European experience of a sustained balance of power, it seems, cannot be generalized to other multistate systems. The new scholarship furthermore shows that there was nothing inevitable about the global state system that we know today. Other outcomes – such as empire – might well have succeeded. On this basis, scholars have speculated that American dominance might have staying power in the 21st century. The Chinese case, in particular, underscores the potential stability of such preeminence. Not only has the Chinese multistate system never reappeared but for millennia the Chinese imperial state exerted a general hegemony over East Asia, which included Japan, Korea and Vietnam.

However, the new historical research also shows that stable single-power dominance relies on more than overwhelming power. To last, dominance must be buttressed by some form of legitimacy, anchored in some kind of common institutions, and it must avoid what has been termed imperial overstretch. Chinese rulers, for instance, knew where to stop – with a few exceptions, they did not try to conquer countries such as Vietnam, Korea, and Japan – and the hierarchical relationship with neighbours was institutionalized via exchanges of gifts for tribute and in elaborate ceremonies such as the Kowtow.

This suggests that American power may be ephemeral. Seen from this vantage point, the Trump administration’s America First agenda – including its refusal to act as a hegemonic stabilizer by shouldering the costs of international institutions such as the UN or NATO and trade agreements such as NAFTA – could be the death throes of American dominance; the desperate actions of a declining hegemonic power no longer able or willing to invest in common purposes. Along these lines, British scholar Barry Buzan has argued that regional international systems such as the East Asian one might be revived as American power falters. To understand these processes, international relations scholars would do well to start quarrying the huge material that the history of other multistate systems has left to us.

Featured image credit: “The Great Wall of China” by panayota. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post What can history tell us about the future of international relations? appeared first on OUPblog.

January 16, 2019

The robin and the wren

Last week (January 9, 2019), our hero was Robin Hood, and I promised to write something about the bird robin. For some reason, in oral tradition, the robin is often connected with the wren. In Surrey (a county bordering London), and not only there, people used to say: “The robin and the wren are God’s cock and hen” (as though the wren were the female of the robin, but then the wren is indeed Jenny). In Wales, the wren is also considered sacred. This association with God (note also: the wren is Our Lady’s hen) did not prevent some people in England from chasing and killing the tiny and perfectly innocuous creature. The same holds for Ireland, where on St. Stephen’s Day (December 26; a public holiday) people chased, captured, and killed the wren wherever it could be found, in commemoration of St. Stephen, who was stoned to death. (I have read that now the killing is no longer practiced.) According to the best-known version, the ceremony goes back to a battle between the Irish and the Vikings, in which the Irish were prevented from surprising their enemy by a wren: it tapped upon the drum or the shield of the Scandinavian warrior (just picking up crumbs and meaning no harm) and woke him up. But the rite is probably much older and has nothing to do with the Vikings, as shown by the date: the day after Christmas ushers in the New Year, while the wren, for some reason, became the symbol of the old one.

The robin is called robin redbreast. The color of its plumage is “explained” in numerous etiological tales about fire bringing. Strangely, some such tales also revolve around the wren. It has been suggested that perhaps the rare Regulus ignicapilla, fire-crested wren, gave rise to this folklore, but that bird’s patch is bronze rather than red. Both birds are said to have performed heroic deeds. The wren from Normandy volunteered to be the bearer of the heavenly fire but got its feathers burned off in accomplishing the task. The other birds gave each a feather to replace the lost one, and only the owl refused to do so. That is why the owl, despised and hunted by all the other birds, has been hiding in the daytime. From a Welsh legend we learn that every day the robin carries a drop of water to quench the flame of the infernal pit and, and it is this flame that scorched its feathers.

Here are our main characters: a wren and a robin. Image credit (top to bottom): THE NORTH WIND DOTH BLOW by Neal Fowler. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr / JENNY WREN by milo bostock. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

Here are our main characters: a wren and a robin. Image credit (top to bottom): THE NORTH WIND DOTH BLOW by Neal Fowler. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr / JENNY WREN by milo bostock. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.The association between the two birds is old, for Shakespeare makes Lady Macbeth say in Macduff’s castle: “…the poor wren,/ The most diminutive of birds, will fight— / Her young ones in her nest—against the owl” (IV, 2: 9-11). And later, Macduff, on learning that his wife and children have been murdered, develops the same avian metaphor: “All my pretty ones? / Did you say all? O hell-kite! All? / What? all my pretty chickens and their dam? At one fell swoop?” (IV, 3, 215-18). In one fell swoop, Shakespeare’s coinage, has become proverbial (the obsolete adjective fell, related to felon, means “fierce, cruel”; the Romance root fel– is of undiscovered origin).

A diminutive suffix does not make a person small or useless. Image credit: Image from page 65 of “Vanity fair” (1900) by Internet Archive Book Images. Public Domain via Flickr.

A diminutive suffix does not make a person small or useless. Image credit: Image from page 65 of “Vanity fair” (1900) by Internet Archive Book Images. Public Domain via Flickr.However, neither the wren nor, most probably, the robin got their names from their color. I am sorry to say that wren is almost hopelessly obscure, even though it already occurred in Old English. The word has two probable cognates, but their existence provides little help. Etymologists’ conjectures are rather uninspiring. Yet, if you want to enlarge your everyday stock of words, I may remind you that the wren is a dentirostral passerine bird of the genus Troglodytes. Unlike other troglodytes, wrens do not dwell in caves; they only tend to forage in dark crevices. By way of consolation, Wren has a perfectly transparent origin: it means Women’s Royal Naval Service.

Robin, which appeared in English texts in the middle of the sixteenth century, looks deceptively transparent. However, it has baffled generations of etymologists. Two ideas come to mind. First, that the bird name must be identical with the proper name Robin. Now, Robin is a nickname for Robert, and -in a so-called diminutive suffix. Although not very common, this suffix does occur every now and then, as in piggin “a small pail,” hoggin “a small drinking vessel,” and dialectal buggin “louse,” to mention a few, while dobbin “horse” is a diminutive of Dob (Dobbin must be familiar to many from Thackeray’s Vanity Fair, in which Dobbin of Ours is an important character; if you don’t remember who he was, reread Chapter V: it will make your day). Several parallels come to mind: jackdaw, Jenny wren, magpie (mag + pie), and a few others from English and French.

Firebird: not a fire bringer but the very embodiment of fire. Image credit: Ivan-Tsarevich and Zhar-bird, 1896 by Yelena Polenova. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Firebird: not a fire bringer but the very embodiment of fire. Image credit: Ivan-Tsarevich and Zhar-bird, 1896 by Yelena Polenova. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Greenough and Kittredge say in their otherwise excellent 1901 book Words and Their Ways in English Speech: “…robin is of course a diminutive of Robert.” Yet this is only an intelligent guess; otherwise, they would not have said of course (I keep repeating year in, year out that of course, surely, certainly, and the rest in works dealing with reconstruction mean only that the authors have no evidence to support their claim). The conjecture is that the word group Robin redbreast was at one time shortened to robin. But Jenny wren, jackdaw, and magpie never turn into jack, jenny, and maggie, though somebody in one of Catherine Potter’s tales says that, after all, a magpie is a kind of pie. I believe that tracing robin to Robin is wrong, even though the most authoritative dictionaries say so.

The other tempting idea is to derive robin form some word meaning “red.” After all, our fire bringer does have a red breast. The Old English name of the robin was ruddock, that is “a (little) ruddy bird,” a gloss on Latin rubisca. However, robin does not sound like any word for “red.” In Old French, the bird was indeed called rubienne, and robin may have been a folk etymological alteration of that noun, but the middle of the sixteenth century is a rather late date for borrowing a popular word from French. An additional difficulty consists in the fact that Engl. robin is not isolated. Originally a Scots word, it has cognates in Dutch (robintje) and Frisian (robyntsje and robynderke “linnet”). Should we posit a borrowing by all three languages from Old French? Such a process would not be unthinkable, but what was so attractive in the French bird name?

Non-specialists may not be aware of how thoroughly the origin of bird names has been explored and how many excellent articles and books have been written on this subject. With some trepidation, I would like to offer a different etymology of robin. I have once written about this word but have not seen any discussion of my idea. Of course, somebody may have refuted it in an obscure footnote. If so, I’ll be grateful for the reference.

More about the subject will be said next week.

Featured image credit: The Stoning of St Stephen by Annibale Carracci. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The robin and the wren appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers