Oxford University Press's Blog, page 206

January 2, 2019

The continuing life of science fiction

In 1998, Thomas M. Disch boldly declared in The Dreams Our Stuff Is Made Of: How Science Fiction Conquered the World that science fiction had become the main kind of fiction which was commenting on contemporary social reality. As a professional writer, we could object that Disch had a vested interest in making this assertion, but virtually every day news items confirm his argument that science fiction connects with an amazingly broad range of public issues.

Take the ongoing debate over different forms of surveillance. There is a long libertarian tradition in science fiction of describing resistance to any kind of private or governmental surveillance in the works of Philip K. Dick and many others. The novelist David Brin joined the debate with his polemic on freedom and privacy in The Transparent Society, but that was published before the attacks of 9/11 in 2001 changed the political climate. Nowadays the USA has even to a certain extent institutionalized science fiction through the SIGMA think tank which advises government agencies including the Bureau of Homeland Security on likely futures.

And what about space? Many members of NASA grew up on a diet of science fiction which has no doubt fed into their projects and designs, but, apart from that, it has become obligatory to signal any new development by drawing a comparison with science fiction. When NASA offered a prize for the best design for an autonomous robot which could be used to explore remote planets, it was immediately compared to the Imperial Probe Droid from Star Wars.

Back in the science fiction of the 1980s and 1990s, virtual reality was something characters accessed through elaborate helmets and suits with complex sensors, which, writers like Pat Cadigan showed, could function like a powerful drug and alienate the wearer from any kind of external reality. Now the development of computerized eyeglasses is trumpeted as ‘making science fiction real’ through this new technology.

One difference from the older VR suits is that they tended to robotize the appearance of the wearer, but the new glasses look conventional visually while they speed up the processing and transfer of information.

Another standard theme in science fiction has been the exploration of the nature of humanity and of our relation to constructs like hybrid combinations of machine and organism — the cyborg — or projected versions of humanity which have become known as “avatars”. While he was working on his film Avatar (2009), James Cameron explained his title term as follows: “In this film what that means is that the human technology in the future is capable of injecting a human’s intelligence into a remotely located body, a biological body.”

Cameron’s application follows a principle of transference and repeats the old science fiction dream of the human mind being projected beyond its bodily limits. Indeed, Cameron admitted that he was drawing on the whole tradition of science fiction for his film and attempting to apply ‘wrap-round’ technology to give the viewer maximum immersion in the spectacle. The more common use of “avatar” denotes a computerized human simulation, introduced as early as 1975 in John Brunner’s The Shockwave Rider and then further dramatized in Neal Stephenson’s Snow Crash (1992). Brunner shows his character in flight from a threatening government programme; Stephenson evokes a more complex situation where his protagonist negotiates his way between different information systems. In Snow Crash avatars confuse their observers by blurring the boundaries between the physical body and its representations, whereas since the 1990s they have become staples of modelling and self-modification. The website Technovelgy includes these cases among many others embodying links between SF and technology.

As the UK novelist Paul Kincaid has said, science fiction is uniquely concerned with novelty, which very quickly produces ennui and so in that sense it is a “genre at the end of time.”

This is another way of saying that science fiction is constantly re-inventing itself. A concern with novelty involves a hyper-awareness of time. As Kincaid argues, maybe it’s a paradoxical sign of the continuing energy of science fiction that we hear so often of its demise.

The post The continuing life of science fiction appeared first on OUPblog.

How to use the passive voice

Writing instructors and books often inveigh against the passive voice. My thrift-store copy of Strunk and White’s 1957 Element of Style says “Use the Active Voice,” explaining that it is “more direct and vigorous than the passive.” And George Orwell, in his 1946 essay on “Politics and the English Language,” scolds us to “Never use the passive where you can use the active.”

The passive is an easy target but used strategically, it can be an important part of any writer’s repertoire. The passive allows writers to connect a sentence to the surrounding context putting the focus on the object of the action rather than the subject. Consider this excerpt from Jody Rosen’s paean to the Murphy bed in the September 2018 New York Times Magazine:

The Murphy bed offered a solution. Each morning, we wake up, pile pillows and blankets in the corner and push the bed up, where it slips into an upright frame so discreet that your eye slides right over it. Presto: The bedroom is transformed into a work space. At night, the contraption is flipped down again, the linen goes back on and we take advantage of a minor engineering marvel ….

The paragraph is about space in a cramped apartment. The second sentence deals with the bed’s disappearance, the third sentence with the bedroom’s transformation, and the forth with the bed again (the “contraption”). To use the active voice takes the focus off the bed and disrupts the unity of the paragraph. Try replacing the third and fourth sentences with the active:

The Murphy bed offered a solution. Each morning, we wake up, pile pillows and blankets in the corner and push the bed up, where it slips into an upright frame so discreet that your eye slides right over it. Presto: we transform the bedroom into a work space. At night, we flip the contraption down again, put the linen back on and take advantage of a minor engineering marvel ….

The paragraph goes from being about the bed to being about the sleepers.

The passive also allows writers to introduce situation and explicate it. In Matthew Desmond’s September 2018 New York Times Magazine piece, “Americans Want to Believe Jobs Are the Solution to Poverty. They’re Not,” we find the passive voice opening a paragraph:

American workers are being shut out of the profits they are helping to generate.

The remainder of that paragraph answers the complex question deferred by the passive verb. To rephrase the sentence in the active would give away the explanation and render it repetitive. It would be something like this:

The decline of unions, the imbalance of the economy, and the loss of good-paying jobs are shutting American workers out of the profits they help to generate.

The passive allows writers to connect a sentence to the surrounding context putting the focus on the object of the action rather than the subject.

Sometimes too the agent of a transitive verb is a noun of such length and complexity that it needs to be at the end of the sentence. Here is an example from Judith Thurman’s “The Mystery of People Who Speak Dozens of Languages” in the September 3, 2018, New Yorker:

The word “hyperpolyglot” was coined two decades ago, by a British linguist, Richard Hudson, who was launching an Internet search for the world’s greatest language learner.

If you try to switch that to the active voice, the sentence becomes unbalanced and collapses in on itself.

Two decades ago, a British linguist, Richard Hudson, who was launching an Internet search for the world’s greatest language learner, coined the word “hyperpolyglot.”

Finally, the passive is often necessary for parallelism or consistency in a relative or coordinate clause. Here are two more examples, one from Judith Thurman again and one from Doug Brock Clark, writing in the Atlantic.

But, from a small sample of prodigies who have been tested by neurolinguists, responded to online surveys, or shared their experience in forums, a partial profile has emerged.

He estimated that hundreds of people were either trapped by the waters or remaining in place to protect their homes from looters.

Rewriting these as active is an exercise in awkwardness.

Many similar examples of elegant passives can be found. The passive voice is such a useful tool that we often don’t even notice when we are using it. That was probably the case with George Orwell, who explained that in clumsy writing “the passive voice is wherever possible used in preference to the active, and noun constructions are used instead of gerunds.”

See what Orwell did there? He used the passive voice.

Featured image credit: Rocky Waters by Stuart Allen. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post How to use the passive voice appeared first on OUPblog.

December 31, 2018

Stories behind Oxford’s top 10 carols and Christmas pieces for 2018

The OUP hire library is a hive of activity running up to Christmas. Months in advance, the hire librarians receive requests for perusal scores of longer Christmas works. From September, hundreds orders for carols flood in – sometimes up to 15 carols in one order!

Singing carols at Christmas is a tradition loved by many and every year there are some recurring favourites. This year is no exception with O Come, all ye Faithful, Hark! The Herald Angels Sing, and Twelve Days of Christmas retaining the top three spots from last year. Some newer arrangements and carols have appeared in this year’s list, including Jingle Bells arranged by David Willcocks, All Bells in Paradise by John Rutter and On Christmas Night by Bob Chilcott.

Below are our top hired carols and Christmas pieces of 2018 and a few facts you may not know.

1. “O Come, all ye Faithful”

Arranged by David Willcocks, from Carols for Choirs 1 and 100 Carols for Choirs

O Come, all ye Faithful was originally written in Latin and appeared first in John Francis Wade’s 1751 collection, Cantus Diversi pro Dominicis et Festis per Annum.

2. “Hark! The Herald Angels Sing”

Composed by Mendelssohn, arr. David Willcocks, from Carols for Choirs 1 and 100 Carols for Choirs

Written by Charles Wesley, this carol was first published as “Hark, how all the welkin rings/Glory to the King of Kings.”

3. “Twelve Days of Christmas”

Arranged by John Rutter, from Carols for Choirs 2 and 100 Carols for Choirs

The “five gold rings” lyric first appeared in the arrangement by Frederic Austin, and is owned by Novello. Therefore, people wishing to arrange this traditional carol must seek copyright permission if they wish to use these lyrics!

4. On Christmas Night

Composed by Bob Chilcott

This Christmas work re-tells the Christmas story through a selection of well-known carols.

5. “Once in Royal David’s City”

Arranged by Gauntlett, arr. David Willcocks, from Carols for Choirs 2 and 100 Carols for Choirs

You may have heard the solo verse of Once in Royal David’s City sung at King’s College carols on Christmas Eve. To save the soloist from nerves running up to the service, the young treble singer is only told he is to sing the first verse just before the service begins. An OUP composer, Bob Chilcott, was one of these soloists!

6. “Jingle Bells”

Arranged by Pierpont arr. David Willcocks, from 100 Carols for Choirs

The lyric “Bells on Bobtail ring” refers to the style of a horse’s tail, where a tail is cut short, or gathered and tied in a knot.

7. “O Little Town of Bethlehem”

Arranged by Vaughan Williams, from Carols for Choirs 1 and 100 Carols for Choirs

Initially a success in the United States, this carol became a success in the UK after Vaughan Williams arranged the words to the traditional English folk tune, Forest Green, in 1906.

8. “All Bells in Paradise”

Composed by John Rutter

The text, written by Rutter, is inspired by the fifteenth-century Corpus Christi Carol.

9. “Sans Day Carol”

Arranged by John Rutter, from Twelve Christmas Carols Set 2, Carols for Choirs 2, and 100 Carols for Choirs

This carol, much like the Sussex Carol and the Coventry Carol, was named after a place, St Day in Cornwall. Soon after the first publication of a 3-verse Sans Day Carol, a 4-verse version was published in Cornish entitled ‘Ma gron war’n gelinen’. Its name was changed from St Day Carol to Sans Day Carol when published in the Oxford Book of Carols.

10. “Angels’ Carol”

Composed by John Rutter, from John Rutter Carols

Angels’ Carol begins with a solo harpist, which alludes to the tradition of Christian music that the harp was the angels’ instrument of choice.

Featured image credit: “Pastel Bokeh Lights Wallpaper” by Sharon McCutcheon. Public domain via Unsplash.

The post Stories behind Oxford’s top 10 carols and Christmas pieces for 2018 appeared first on OUPblog.

Top ten developments in international law in 2018

This year was, once again, one of great political turmoil. The international legal order is not immune from the impact of the rise of populism and increasingly strained relations between many of the world’s most powerful states. A positive view is that we are witnessing a period of global re-adjustment. A more negative take is that there is a real risk of the fabric of the international legal order, created so carefully in the aftermath of the First and Second World Wars, unravelling. One of this year’s key themes reflects the political stalemate: states and private parties turned to the courts to try and resolve disputes in the absence of political or diplomatic solutions. In some cases this was successful (environmental litigation), in others it is much less likely that international litigation will bring about a lasting resolution. With that in mind, let’s take a look back at ten major events, developments, and cases that shaped international law in 2018.

1) Protecting the environment through the courts

In parallel to political efforts to stop climate change and protect the world’s environment (including, potentially, a new Global Pact for the Environment), international and domestic courts have been busy this year trying to protect environmental and intergenerational rights. In February, the International Court of Justice awarded compensation for environmental damage for the first time in Costa Rica v. Nicaragua and, soon afterwards, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights issued an important advisory opinion on the right to a healthy environment, in the context of protecting the Greater Caribbean region (more on the Court’s busy year below). At the domestic level, Colombia’s Supreme Court handed down a ground-breaking judgement granting legal personality to the Amazon region, in a case brought on behalf of 25 young people. In the Netherlands, the Court of Appeal upheld a crucial judgment in the 2015 Urgenda case, in which the Court of First Instance ordered the Dutch state to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 25% by 2020, as compared to levels in 1990.

2) Salisbury nerve agent attack

In a sleepy British town in early March, an incident straight out of a cold war spy novel took place: a former Russian spy and his daughter were poisoned with Novichok, a military-grade, highly lethal nerve agent. Sergei and Yulia Skripal survived, but Dawn Sturgess, a local woman unconnected to the attack, died in June from accidental exposure. British intelligence, working together with several other intelligence services and analysts from the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, identified two Russian suspects. Theresa May, the British prime minister, characterized the attack as an unlawful use of force by Russia on UK territory. A number of consequences flow from this characterization under international law, including an argument that—however briefly—the UK and Russia were engaged in an armed conflict. Along with the murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi in Saudi Arabia’s consulate in Istanbul in October, this episode showed that Cold War-style infringements of sovereignty are far from over. The story had a curious postscript later in the year, when it was revealed that the Netherlands had expelled four Russian nationals who were caught trying to hack the OPCW’s systems.

3) Palestine takes to the courts

With a political solution to the Israel-Palestine conflict seemingly further away than ever, the Palestinians have turned to international adjudication in an attempt to safeguard their rights and gain a diplomatic advantage. In April, Palestine filed an inter-state complaint against Israel at the UN’s Committee against Racial Discrimination, the first inter-state claim ever filed under the UN’s human rights system. In May, the Palestinian foreign minister referred the situation in Palestine to the International Criminal Court. Then in September, the Palestinian government made its most high-profile move, starting proceedings against the United States at the ICJ. Basing itself on the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations, it claims that the US breached its international obligations by moving its embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem. The Court’s first move will be deciding whether it has jurisdiction. The world will be watching.

4) The Western Sahara dispute and the European Union

Another territorial dispute, which has received markedly less attention, is the one between Morocco and Western Sahara. After more than forty years of conflict, and with Morocco controlling around two-thirds of its southern neighbour’s territory, no resolution is in sight, and it is creating headaches for the EU’s relationship with Morocco. In February, the European Court of Justice decided that the EU-Morocco fisheries agreement cannot apply to waters adjacent to Western Sahara, confirming in the process that it has the power to test the compliance of international agreements concluded by the EU with international law. A few months later, the European Commission adjusted the EU-Morocco Association Agreement to extend benefits to products originating in Western Sahara. It seems that, for the Court, the principle of self-determination trumps political and trade considerations. Whether the same can be said for the Commission is less clear.

5) The crime of aggression comes within the International Criminal Court’s jurisdiction

Twenty years after the Rome Statute was signed and nearly eight years after International Criminal Court Member States agreed on its definition, the crime of aggression became a crime within the Court’s jurisdiction. Only nationals of states who have accepted the relevant amendments to the Statute can be prosecuted and then only if the crimes aren’t committed on the territory of a state that has opted out of jurisdiction, but the impact could still be momentous. Proponents of the criminalization of aggression argue that it will end impunity for starting an illegal war; opponents claim it is unlikely to lead to successful prosecutions, and could derail future humanitarian interventions aimed at stopping atrocities being committed against civilians (whether those interventions are desirable in the first place is a whole different debate..). Either way, the entry into force of the crime of aggression is a good story for the Court, in a year was marked by the acquittal by the Appeals Chamber of Central African Republic warlord Jean-Pierre Bemba, nearly eight years after his trial first started.

6) Interesting times in San José

Many international courts and tribunals have seen an uptick in cases in the last few years, but perhaps none as dramatically as the Inter-American Court of Human Rights. At a time when several South American countries appear to be moving away from the international rule of law and protection of human rights, the Court is proving a beacon of hope. Among other decisions, the Court held in an advisory opinion that governments must allow citizens to change their name and records in accordance with their gender identity and same-sex couples have the right to marry; it upheld the political rights of critics of the government in Venezuela; and, in a wide-ranging opinion on the protection of the environment, that, in certain cases, states can have jurisdiction over environmental crimes even if they are committed outside of their territory.

7) Trade wars: national security and the World Trade Organization

This was also the year that the trade war between the US and the EU, Canada, and China kicked off in earnest. Tariffs have been slapped on goods worth hundreds of billions of dollars, with the potential to seriously disrupt the post-war world trading system. Lawsuits have started to fly at the World Trade Organization. Much will hinge on the scope of the ‘national security exception’, the defence invoked by the US to impose tariffs on European steel and aluminium. Whether or not the WTO will be able to conclusively answer that question is up in the air: the US’ refusal to allow new appointments to the WTO’s Appellate Body means that the dispute settlement system—one of international law’s most successful—could grind to a halt as early as next year.

8) The Global Migration Compact

A number of other crises have pulled the spotlight away from the global migration crisis, but refugees and migrants continued to brave the journey to Europe in their hundreds of thousands. Over 700,000 Rohingya refugees are stuck in the Cox’s bazaar camp in Bangladesh. With the global political climate turning against welcoming refugees, the battle between those seeking to help them or to turn them back is increasingly playing out in the courts. Against this background, the Global Compact on Migration was adopted in December. The Compact is a ground-breaking agreement, negotiated by governments under the auspices of the United Nations, which comprehensively covers all dimensions of international migration. Its provisions are not legally binding in the traditional way, but it could prove highly influential.

9) A genuine chance to reform investor-state arbitration

Years of increasing dissatisfaction with the current investor-state arbitration system have finally led to a real push for change: in October, states decided at a meeting of the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL) to reform the system. The list of discontents is long, but focuses on the perceived unfair nature of investment arbitration, which is often seen to favour the rights of investors over (developing) states’ regulatory freedom, as well as inconsistent awards, an extreme lack of diversity among arbitrators, and the cost and length of proceedings. The next step is for states to decide on a list of potential reforms. Proposals range from keeping the current system of ad hoc arbitral panels but with more transparency and a better process for reviewing inconsistent or incorrect awards, to a permanent Multilateral Investment Court or Appellate Body. Discussions will continue in Commission’s Working Group in 2019. In another sign of the times, the International Court of Justice has announced that its judges will no longer sit as arbitrators on investment dispute panels. This had previously been a common, and lucrative, side line for many judges.

10) The centenary of World War I

This year marked the centenary of the end of World War I. Even after 100 years, the suffering caused by WWI is staggering: it killed between 15-20 million combatants and civilians. That is over 1% of the total world population at the time. Just as many were wounded. It is no surprise that end of the War marked the first real attempt to create a global legal order which could avoid future wars. The Covenant of the League of Nations revolutionized international relations by obliging its Member States not to resort to war to settle their disputes, which were to be submitted instead to the newly created Permanent Court of Arbitration and Permanent Court of International Justice. If the Allied Powers had managed to get their hands on Kaiser Wilhelm II, the first international criminal trial for aggression might even have happened. The system created after WWI eventually buckled under its own ambition, but it provided the blueprint for the legal order we have today. One hopes that today’s political leaders will reflect on the two global catastrophes that provided the impetus for the creation of the international legal system, before they take steps to dismantle it.

Featured image credit: “Backpack, light, atlas” by Arthur Edelman. Public domain via Unsplash.

The post Top ten developments in international law in 2018 appeared first on OUPblog.

December 30, 2018

Philosophy in 2018: a year in review [timeline]

2018 has been another significant year for the philosophy world and, as it draws to a close, the OUP Philosophy team reflects on what has happened in the field. We’ve compiled a selection of key events, awards, and anniversaries, from the bicentenary of the birth of Karl Marx to Martha Nussbaum winning the Berggruen Prize and the death of the philosopher Mary Midgley. Take a look through our interactive timeline.

Which key events would you add to our timeline of philosophy in 2018? Let us know in the comments.

Featured image credit: The Thinker Rodin Museum by Maklay62. CC0 via Pixabay .

The post Philosophy in 2018: a year in review [timeline] appeared first on OUPblog.

December 27, 2018

Will Congress penalize colleges that increase tuition?

Senator Charles Grassley of Iowa will serve as chairman of the Senate Finance Committee during the upcoming 115th Congress. Senator Grassley’s decision to lead the Finance Committee may have important consequences for the nation’s colleges and universities. Grassley, a Republican, has criticized increased tuition charges in the face of the pronounced, tax-free growth of many college endowments.

In light of his prior statements and the current political environment, a Grassley-led Finance Committee may scrutinize higher education endowments. On the committee’s agenda could be legislation aimed at the tax benefits such endowments enjoy and the benefits of tax-exempt entities more generally.

Grassley has in the past suggested that college endowments be subject to regulation similar to that applying to private foundations. Private foundations are required to distribute annually an amount equal to at least 5% of their net incomes. A foundation that fails to meet distribution mandate must pay a penalty tax.

Some commentators have urged Congress to penalize a college or university endowment in this fashion if the school the endowment supports does not control its tuition costs.

Last year, the Republican-controlled Congress imposed a tax on certain large academic endowments. However, the tax is a flat 1.4% tax on endowment incomes. The tax is not directly tied to tuition levels: An educational endowment that spends more of its income on scholarships pays the same tax as a school with an identical endowment that spends less on scholarships.

It is likely that a Grassley-led Finance Committee will consider changes to directly regulate the tuition levels of endowed educational institutions. That consideration will take place in a Congress in which Republicans only control the Senate and House Democrats will have to choose either bipartisan cooperation or confrontation with the Senate.

An educational endowment that spends more of its income on scholarships pays the same tax as a school with an identical endowment that spends less on scholarships.

Another area potentially subject to further view by a Grassley-led Finance Committee is the tax treatment of donor-advised funds. Today all private foundations pay to the federal Treasury a tax of 1% or 2% of their incomes. Donor-advised funds do not pay this tax.

For all practical purposes, donor-advised funds are the functional equivalents of private foundations. A donor-advised fund is an account sponsored by a public charity such as a community foundation or a charity established by a commercial investment firm like Vanguard or Fidelity. Donor-advised funds are marketed by their sponsors as substitutes for private foundations. Someone contributes to a donor-advised fund sponsored by a public charity with the understanding that his funds will be separately earmarked and that he will advise the sponsoring organization how to invest and distribute these earmarked funds and the income they produce. While donors technically just advise about the tax-exempt funds they create with tax-deductible dollars, in practice, that advice is the equivalent of the control that the creators of private foundations exercise over their foundations. A Grassley-led Finance Committee might consider extending the existing tax on private foundations’ incomes to donor-advised funds.

On many subjects, a Republican-controlled Senate and a Democratic-controlled House will have difficulty finding common ground. However, the tax treatment of higher education endowments and donor-advised funds could be one area where bipartisan agreement is achievable in the 115th Congress.

Featured image credit: University Museum, Harvard Campus, Cambridge, Massachusetts by Rizka. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Will Congress penalize colleges that increase tuition? appeared first on OUPblog.

December 24, 2018

The history of holiday traditions [podcast]

One of the best parts of the holiday season is that everyone celebrates it in their own unique way. Some traditions have grown out of novelty, such as eating Kentucky Fried Chicken dinners on Christmas in Japan. Others date back centuries, like hiding your broom on Christmas Eve in Norway to prevent witches and evil spirits from stealing it to ride on. Holiday traditions can stir up feelings of nostalgia and spark interest in exploring one’s ancestral past. We start to wonder where did these traditions come from? And how did these traditions spread and evolve?

On this episode of the Oxford Comment, we examine the history of holiday traditions and attempt to figure out why we continue to celebrate them; even the strange ones. Our guest, Gerry Bowler, author of “Christmas in the Crosshairs: Two Thousand Years of Denouncing and Defending the World’s Most Celebrated Holiday” explores the entire sweep of Christmas history and provides a global scope of its influence.

Featured image credit: Champagne, bottle, drink and wine by JESHOOTS.COM. Public Domain via Unsplash.

The post The history of holiday traditions [podcast] appeared first on OUPblog.

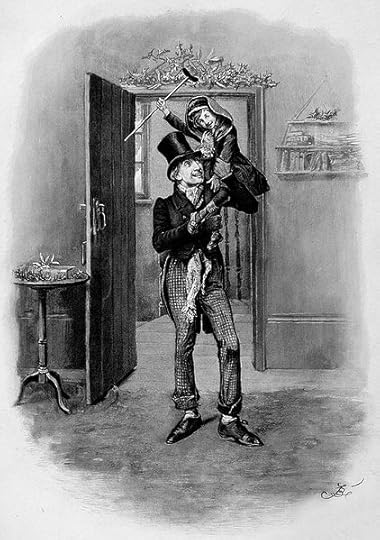

A classic christmas dinner with the Cratchits

Following a recipe for roast goose by Mrs Beeton, here’s that classic Christmas dinner portrayed by Charles Dickens in the famous scene from A Christmas Carol. Here Ebeneezer Scrooge watches with the Ghost of Christmas Present as the Cratchit family sits down to roast goose and Christmas pudding.

“And how did little Tim behave?” asked Mrs Cratchit, when she had rallied Bob on his credulity, and Bob had hugged his daughter to his heart’s content.

“As good as gold,” said Bob, “and better. Somehow he gets thoughtful, sitting by himself so much, and thinks the strangest things you ever heard. He told me, coming home, that he hoped the people saw him in the church, because he was a cripple, and it might be pleasant to them to remember upon Christmas Day, who made lame beggars walk, and blind men see.”

Bob’s voice was tremulous when he told them this, and trembled more when he said that Tiny Tim was growing strong and hearty.

His active little crutch was heard upon the floor, and back came Tiny Tim before another word was spoken, escorted by his brother and sister to his stool before the fire; and while Bob, turning up his cuffs — as if, poor fellow, they were capable of being made more shabby — compounded some hot mixture in a jug with gin and lemons, and stirred it round and round and put it on the hob to simmer; Master Peter, and the two ubiquitous young Cratchits went to fetch the goose, with which they soon returned in high procession.

Such a bustle ensued that you might have thought a goose the rarest of all birds; a feathered phenomenon, to which a black swan was a matter of course — and in truth it was something very like it in that house. Mrs Cratchit made the gravy (ready beforehand in a little saucepan) hissing hot; Master Peter mashed the potatoes with incredible vigour; Miss Belinda sweetened up the apple-sauce; Martha dusted the hot plates; Bob took Tiny Tim beside him in a tiny corner at the table; the two young Cratchits set chairs for everybody, not forgetting themselves, and mounting guard upon their posts, crammed spoons into their mouths, lest they should shriek for goose before their turn came to be helped. At last the dishes were set on, and grace was said. It was succeeded by a breathless pause, as Mrs Cratchit, looking slowly all along the carving knife, prepared to plunge it in the breast; but when she did, and when the long expected gush of stuffing issued forth, one murmur of delight arose all round the board and even Tiny Tim, excited by the two young Cratchits, beat on the table with the handle of his knife, and feebly cried Hurrah!

There never was such a goose. Bob said he didn’t believe there ever was such a goose cooked. Its tenderness and flavour, size and cheapness, were the themes of universal admiration. Eked out by apple-sauce and mashed potatoes, it was a sufficient dinner for the whole family; indeed, as Mrs Cratchit said with great delight (surveying one small atom of bone upon the dish), they hadn’t ate it all particular, were steeped in sage and onion to the eyebrows! But now, the plates being changed by Miss Belinda, Mrs Cratchit left the room alone — too nervous to bear witness — to take the pudding up and bring it in.

Image credit: “Reproduced from a c.1870s photographer frontispiece to Charles Dicken’s A Christmas Carol” by Frederick Barnard (1846-1896). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: “Reproduced from a c.1870s photographer frontispiece to Charles Dicken’s A Christmas Carol” by Frederick Barnard (1846-1896). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Suppose it should not be done enough! Suppose it should break in turning out! Suppose somebody should have got over the wall of the back-yard, and stolen it, while they were merry with the goose — and supposition at which the two young Cratchits became livid! All sorts of horrors were supposed.

Hallo! A great deal of steam! The pudding was out of the copper. A smell like a washing-day! That was the cloth. A smell like an eating-house and a pastrycook’s next door to each other, with a laundress’s next door to that! That was the pudding! In half a minute Mrs Cratchit entered — flushed by smiling proudly — with the pudding, like a speckled cannon-ball, so hard and firm, blazing in half of half-a-quartern of ignited brandy, and bedight with Christmas holly stuck into the top.

Oh, a wonderful pudding! Bob Cratchit said, and calmly too, that he regarded it as the greatest success achieved by Mrs Cratchit since their marriage. Mrs Cratchit said that now the weight was off her mind, she would confess she had her doubts about the quantity of flour. Everybody had something to say about it, but nobody said or thought it was at all a small pudding for a large family. It would have been flat heresy to do so. Any Cratchit would have blushed to hint at such a thing.

At last the dinner was all done, the cloth was cleared, the hearth swept, and the fire made up. The compound in the jug being tasted, and considered perfect, apples and oranges were put upon the table, and a shovel-full of chestnuts on the fire. Then all the Cratchit family drew round the hearth, in what Bob Cratchit called a circle, meaning half a one; and at Bob Cratchit’s elbow stood the family display of glass. Two tumblers, and a custard-cup without a handle.

These held the hot stuff from the jug, however, as well as golden goblets would have done; and Bob served it out with beaming looks, while the chestnuts on the fire sputtered and cracked noisily. Then Bob proposed:

“A Merry Christmas to us all, my dears. God bless us!” Which all the family re-echoed.

“God bless us every one!” said Tiny Tim, the last of all.

Feature image credit: “lights christmas luminaries night” by Jill111. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post A classic christmas dinner with the Cratchits appeared first on OUPblog.

December 23, 2018

Carbon tax myths

Over a two-week period in November 2018, the Camp Fire, the deadliest forest fire in California history, burned over 150,000 acres, killed more than 80 people, and destroyed some 18,000 buildings. A National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration report documents the unusually warm and dry conditions that sparked this fire. Each year sees new records being set for temperature extremes in the United States. Six of the ten hottest years on record have occurred since 2000. The six months ending this past October was the hottest six-month period on record, surpassing the previous record for 2016 by 0.3 degrees F. This is climate change at work.

The Camp Fire is a tragedy of epic proportions but should come as no surprise. A 2017 National Climate Assessment report has documented increases in large fires in 7 out of 10 Western regions over the period 1984-2011. Larger and more frequent forest fires are just one of the outcomes of our warming planet. The most recent report of the National Climate Assessment states that “annual losses in some economic sectors are projected to reach hundreds of billions of dollars by the end of the century—more than the current gross domestic product of many US states.”

The National Climate Assessment makes clear that doing nothing to reduce our greenhouse gas emissions will be extremely costly and puts the lie to the claim that cutting our emissions is too expensive a policy for the United States. Doing nothing will be much more costly. But what’s the right action to take? Economists across the political spectrum agree that a national carbon tax is the best way forward, as evidenced by the membership in the Pigou Club, Harvard economist Greg Mankiw’s list of economists who support the use of taxes on pollution such as greenhouse gases to combat climate change.

The arguments for a national carbon tax are compelling. Most importantly, a tax ensures we cut emissions at the lowest possible cost to society. It also would raise a lot of revenue – something regulations do not do. The US Treasury estimates that a carbon tax starting at just under $50 a year would raise over $2.2 trillion over a ten year period. This is after netting out reductions in income tax collections because of the higher costs of fossil fuels and other greenhouse gas emitting inputs to production. You could do quite a lot with $2.2 trillion. It could help finance the Green New Deal that newly elected members of Congress are calling for. Or it could provide a hefty climate dividend to US households, as proposed by the bipartisan Climate Leadership Council. The Treasury study shows that a dividend policy like that proposed by the CLC would make over 70% of US households better off. In other words, more than two-thirds of US households would get back more in dividends than they would pay in higher costs for carbon-intensive goods.

That low- and moderate-income households would have more money to spend or save with a carbon tax cum dividend puts the lie to one of the common misperceptions about a carbon tax – that it is regressive. One recent academic study by current and former Stanford economists shows that a carbon tax is likely to be progressive even if one ignores revenue. That’s because the tax impacts owners of capital more than it does workers and because transfer payments – disproportionately received by lower-income households – tend to be indexed against price increases.

A carbon tax will certainly kill more (if not all) of the remaining coal mining jobs. But solar, wind, and other green technologies have created hundreds of thousands of new jobs.

Here’s another myth that is, well, a myth: that a carbon tax is a job-killer. Sure, it will lead to fewer jobs in coal mining. Coal mining jobs have shrunk by nearly half over the past decade from roughly 91,000 to 50,000 jobs. Most of that job loss is due to the shift from Eastern to Western coal that can be mined with fewer workers with large excavation equipment that strips the topsoil off and reveals 60 to 100 foot deep beds of coal that can be hauled off in giant dump trucks. The other factor killing coal jobs is cheap natural gas, a product of the fracking revolution. A carbon tax will certainly kill more (if not all) of the remaining coal mining jobs. But solar, wind, and other green technologies have created hundreds of thousands of new jobs. For every job lost in coal mining, a green economy creates nearly ten new jobs.

Here’s another myth: a carbon tax will stunt economic growth. Despite a carbon tax of roughly $135 a ton, Sweden seems to be growing just fine. The accompanying figure shows that Swedish GDP has risen by nearly 80% since it enacted a carbon tax in the early 1990s while its emissions have fallen by one-quarter. The gap between Sweden’s GDP growth rate and that of the US has shrunk since Sweden enacted a carbon tax. The carbon tax can’t explain the convergence in growth rates. But it’s hard to argue that Sweden’s carbon tax has crippled its economy.

Will a US carbon tax make a difference given the surging economies – and emissions – of the developing world? Strictly speaking, a US carbon tax will do little by itself to dent global emissions. But it is difficult to imagine that developing countries struggling to move their citizens out of poverty will take the lead in reducing emissions if the world’s wealthiest country is not taking strong climate action itself. It is true that major emitting countries and blocs like the EU and China have reiterated their commitment to the promises they made in the Paris Agreement despite the Trump Administration’s retreat from the US commitments. But it is doubtful parties to the Paris Agreement will strengthen those commitments to the extent needed to address the climate problem in a meaningful way without US engagement. If the United States enacted a carbon tax and showed leadership in moving to a zero- carbon economy, it would strengthen the hand of leaders in major developing countries like China, India, and Indonesia who want to reduce emissions. A US carbon tax will not guarantee that developing countries will dramatically ramp up their efforts to reduce carbon pollution. Our acting to reduce emissions significantly is a necessary condition for more ambitious global engagement on what is, after all, a global problem.

Featured image credit: Cloud Factory by Dirk Duckhorn. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Carbon tax myths appeared first on OUPblog.

Dancing politics in Argentina

Argentina’s rich history of 20th and 21st century social, political, and activist movements looms large in popular imagination and scholarly literature alike. Well-known images include the masses gathered in the Plaza de Mayo outside the iconic pink presidential palace during populist President Juan Domingo Perón’s first terms (1946-1955). This scene was imprinted in popular culture, for better or worse, by Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Evita. The Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo famously held weekly demonstrations in the same plaza beginning in 1977 to decry the forced disappearance of their children by a brutal military government. Argentine protest movements continue to make headlines, most recently around feminist issues. Ni una menos (Not One [Woman] Less) is a movement against gender-based violence that has spread across Latin America through the strategic coupling of physical demonstrations with social media-based activism. While artists have a celebrated history of participating in these social and political movements, one community has long been excluded from the story: contemporary dancers.

“Contemporary” dance, though difficult to definitively categorize aesthetically or by time period, generally signals practices with some relationship to the Western concert tradition (i.e. ballet and modern dance). While tango is synonymous with dance in Argentina, the country has a long tradition of classical ballet and the earliest modern dance experiments date to the 1940s. Beginning in the 1960s, contemporary dancers began to produce dance works and cultivated creative projects and off-stage activisms that paralleled the political vanguards of the time, particularly following the 1966 military coup that installed General Juan Carlos Onganía’s repressive dictatorship. Susana Zimmermann’s Dance Laboratory (1957-1970), for example, offered an innovative model for dance practice and production that aimed to “create-together-a-new-language-for-a-new-man.” The group’s mission articulated with the revolutionary spirit of the time and protests against the dictatorship. While Zimmermann’s group was not officially affiliated with any political group, their stage works spoke to the political climate in powerful ways.

By the early 1970s, militant political groups—particularly armed factions—captured the national imagination and became a major concern for the military government. While the world of concert dance might seem distant from that of armed militancy, contemporary dancers indeed participated in these groups and in some instances put their knowledge of dance to work for the revolutionary cause. Militant dancers formed part of the infamous 1972 prison break at the Rawson Penitentiary in Trelew, an escape that ended tragically with the military’s execution of sixteen political prisoners. For example, choreographer Silvia Hodgers used exercises drawn from her dance training to both ready her comrades for the physical demands of the escape and choreograph their actual exit.

Image credit: Oduduwá Danza Afroamericana dancers and volunteers participating in the March 24, 2011 human rights march. Provided by and used with permission of the author.

Image credit: Oduduwá Danza Afroamericana dancers and volunteers participating in the March 24, 2011 human rights march. Provided by and used with permission of the author.The political struggles that marked the early 1970s culminated in the 1976 coup d’état that began Argentina’s last military dictatorship (1976-1983), a regime responsible for the forced disappearance and murder of an estimated 30,000 citizens. During this dark period, contemporary dance’s political intervention was subtler: it offered a mode of everyday survival. The military dictatorship closely surveilled citizens’ behavior, and Argentines had to make certain that their acts did not associate them with “subversion.” The sense of belonging in dance studios and experience of relative autonomy that they provided offered a life-sustaining respite from the dictatorship’s control. In the years following the dictatorship when Argentina faced the daunting task of grappling with the violence of this period, contemporary dance works delved into this past and helped make visible individual and collective traumas. Works like Silvia Vladimivsky’s tango-inflected The Name, Other Tangos (2006) explored the grief of forced disappearance and echoed the work of human rights groups that fought for justice in the juridical and legislative spheres.

When a staggering economic crisis struck Argentina in 2001, the contemporary dance community once again responded. As the working and middle classes took to the streets in protest, contemporary dancers imagined new forms of cooperative labor that challenged traditional ways of making art. Dancers for Life, a community dance group focused on collective creation, formed in 2002 and rehearsed until 2018 in a breadstick factory that was reopened by a labor cooperative following the 2001 crisis. As Argentina once again faces economic uncertainty, new generations of dancers are rethinking the relationship between art and labor politics. The Argentine Association of Dance Workers and the Forum for Dance in Action are two current organizations dedicated to fighting for dancers’ rights as workers in the face of deep government cuts to arts and education funding under conservative President Mauricio Macri.

Though contemporary dance’s history of political engagement is far less documented than that of other arts, even a brief overview demonstrates the centrality of this community to legacies of political struggle in Argentina. The political future of Argentina—and Latin America more broadly—of course remains uncertain. The ongoing rise of right-wing governments across the region is linked with the return of neoliberal economics and conservative social policies. The recent election of Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil offers the most recent (and arguably extreme) example of this shift. Contemporary dancers, surely, will continue to find ways to strategically and thoughtfully move through and intervene in these changing political landscapes.

Featured image credit: Dancing in the shadow by Ardian Lumi. Public Domain via Unsplash.

The post Dancing politics in Argentina appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers