Oxford University Press's Blog, page 208

December 16, 2018

The evolution of the word “terror”

Terror comes into English in the late fourteenth century, partly from Middle French terreur, and partly directly from Latin terror. The word means both “the state of being greatly frightened” and “the cause of that state,” an ambiguity that is central to its future political meanings. In Early Modern English, terror comes to stand for a state of fear provoked on the very edge of the social. That state is associated with the god Pan and the fear that grips men when they feel themselves removed from any social contact. It also stands for death itself.

The political meanings of terror date from the period March 1793 to July 1794, when the use of organized intimidation became an instrument of policy for the Jacobins and Robespierre. Interestingly, the announcement of terror as public policy was as much an attempt to claim the breakdown of social order as a government policy as it was a deliberate attempt to cause that breakdown. Throughout the first half of the nineteenth century, “a state of affairs in which the general community live in dread of death or outrage” was the dominant political meaning, and was still the most important meaning for the first edition of Oxford English Dictionary. It is worth remembering that most political terror during the twentieth century, from the German genocide in the Herero War of 1904-05 to the gulags of Stalin’s Soviet Union and the terror bombing by the Allied air forces during World War II, has been state terror (to be distinguished from state-sponsored terrorism, discussed below).

The invention of dynamite in 1863 by Alfred Nobel was the crucial technological condition which gave us modern terrorism. Although both terrorism and terrorist were joined in relation to the Jacobins, widespread use of these modern nouns comes when small groups of political dissidents attempt to use violent explosive force against an existing state to bring about political change. Three more or less distinct stages in this process can be sketched. The first, up until 1914, sees particularly in Russia the growth of a kind of terrorism which describes itself as such, and which believes that the social order is so rotten that a single act of violence aimed at the center of power will bring about a revolutionary transformation. Some sense of this is captured in the phrase little terror, which begins to be used at this time to describe difficult young children. This first wave of terrorism found unprecedented historical success when the assassination of the Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo in 1914 occasioned what Keynes called the “European Civil War.”

This conception of terrorism, the model for a host of imitators, is captured in the slogan “one man’s terrorist is another man’s freedom fighter.”

In the aftermath of that war, the Irish, who had participated in this first chapter of terrorism, developed a terrorist campaign targeting the police, a campaign that described itself as part of a military struggle for national liberation. This conception of terrorism, the model for a host of imitators, is captured in the slogan “one man’s terrorist is another man’s freedom fighter.” The focus of definition for terror passes from the act of terrorism itself to the status of the terrorist and whether he or she is authorized by an alternative and unrecognized legal authority. Thus, Michael Collins and the Irish Republican Army claimed their actions as legitimized by the Irish Republic that Pearse had proclaimed on the steps of the Post Office on Easter Monday 1916. Similarly, Umkhonto we Sizwe (or MK), translated as “Spear of the Nation,” authorized its violence in relation to the African National Congress, an authorization accepted by George W. Bush when he signed a bill removing the ANC from the US terror blacklist. In this period, use of terrorism and terrorist becomes widespread – note for example the decision made by British colonial authorities’ in the Malayan emergency of the 1950s to always refer to “Communist terrorists” and never just “Communists.”

This second stage culminated in the terror campaigns of the National Liberation Front or FLN (one of which is famously represented in Gillo Pontecorvo’s Battle of Algiers) that led to Algerian independence in 1962. The Algerian experience became the constant reference point for a new wave of terrorism in the aftermath of the Six-Day War of 1967, when a variety of Palestinian groups adopted terrorist tactics now taken onto an international stage. This was also the start of state-sponsored terrorism, as different Arab states supported different Palestinian groupings.

A full history of terrorism would need to reflect continuously on both the development of weapons and communication technology. The new phase, for instance, was marked by plastic explosives (the expression car bomb is added to the language in this period) and the ability (most famously at Munich in 1972) to get the world’s instant attention through television screens. In the 1980s, with the failure of Arab nationalism to deliver either socialist or capitalist success for its peoples, a new form of Islamic terrorism began to develop. This new variety of terrorism claimed its authority not from a political but from divine authority. This appearance of the divine was one of the conditions of the emergence of the suicide bomber (another was further sophistication of the technology of plastic explosives). These developments culminated in the attacks of September 11, 2001.

In the aftermath of the September 11th attacks, George W. Bush announced his “War on Terror,” thus, as Terry Jones remarked, becoming the first world leader to declare war on an abstract noun. The political effects of this use of terror have prompted widespread questioning of the term and of the nature of terrorism itself. Distinguishing between terrorist and non-terrorist acts of violence in terms of the acts themselves is problematic, and if we follow the Hobbesian arguments of the German legal philosopher Carl Schmidt that at the root of every state’s legitimate use of violence is an illegitimate use of violence, it is difficult to produce a distinction in terms of legal authority. The linguistic effects of Bush’s war are difficult to gauge, but it could be argued that Bush completed a process begun by Robespierre and that a word initially used to describe emotional states experienced at the very margins of the social is now limited entirely to describing emotional states experienced at the very heart of social and political life.

Featured image credit: Hogan’s Flying Column. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The evolution of the word “terror” appeared first on OUPblog.

2018 Philosophers of the Year: Schopenhauer, Marx, Merleau-Ponty [quiz]

This December, the OUP Philosophy team marks the end of a great year by honouring three of 2018’s top Philosophers of the Month. The immeasurable contributions of Arthur Schopenhauer, Karl Marx, and Maurice Merleau-Ponty to the field of philosophy ensure their place among history’s greatest thinkers. To celebrate, we’ve compiled a quiz highlighting the lives and works of each. Test your knowledge of these legendary philosophers.

Featured Image: Library Books Literature by Free-Photos. CC0 via Pixabay .

The post 2018 Philosophers of the Year: Schopenhauer, Marx, Merleau-Ponty [quiz] appeared first on OUPblog.

December 15, 2018

Desires for power: sex scandals and their proliferation

Why do sex scandals seem to follow people in positions of power? Politicians, Hollywood producers, priests, gurus – none seem to be exempt. Money and sex: the combined forces that corrupt and surround powerful public figures. When accusations emerge, they tend to center on the moral failings of a particular individual. But this individualization provides no rationale for the extraordinary proliferation of sex scandals. In short, we miss the opportunity to recognize broader social structures of power relations that allow and even enable these kinds of abuses to occur.

The unapologetic authoritarianism of guru-disciple relationship makes it a revealing case study through which to analyze power relations, particularly those related to physical touch and sexuality. As I argue in a recent article, “Guru Sex,” in the guru-disciple relationship there are social conventions surrounding touch, what I call haptic logics. Put simply, the guru is believed to be a powerful conduit for both spiritual and social power. In response, believers want to be close to the guru, which has both spiritual and social effects. Spiritually, devotees believe that proximity to the guru (and the guru’s touch) results in positive spiritual effects, such as miracles, healing, enlightenment, or personal transformation. Socially, proximity to the guru has a direct correlation to increased power within the devotional community. Recognizing these positive effects, devotees yearn to be close to the guru, and, importantly, they are expected to do so and to want to do so. These haptic logics give gurus extraordinary power to use, abuse, and demand proximity within a system that justifies, reinforces, and sacralizes their physical touch.

Devotional cults that exalt gurus envision the guru to be in possession of “special gifts” (a term used by sociologists Max Weber and Emile Durkheim to describe charisma). The guru’s charisma is embodied, contagious, and intentionally transferrable. Gurus are believed to be physical embodiments of spiritual power and to be able to transmit that power to their followers. This perceived ability justifies the guru’s exalted social status. It also cultivates followers’ desire for proximity to the guru so that they might gain access to the perceived source of sacred power. The physical body of the guru is a sacred object; proximity to the guru is a sacred opportunity.

In such a social system, increased proximity to the guru, such as private audiences and unconventional intimacies (massaging the guru’s feet, for example) are communally envisioned as a blessing for any devotee. Deliberate rejections of proximity are unthinkable within such communities, for example: leaving a position near the guru for one more distant without reason; discarding any of the guru’s possessions received as gifts; or rejecting the guru’s blessed food. Instead, devotees rush to be close the guru, to follow the guru, and outstretch their hands in an attempt to touch the guru. Many gurus employ bodyguards, flanked personal assistants, and sometimes even an armed entourage to protect against this desire to touch them. This institutionalized communal longing for and valorization of the guru’s physical touch systematically justifies gurus’ physical contact with devotees. Devotees are socialized to long for the guru’s touch; the guru is socialized to impart his or her touch (and access to be touched) as a blessing to devotees.

But as Tulasi Srinivas has discussed, proxemic desire is not only devotees’ longing to be close to the guru for the possible effects of spiritual transformation; it is also the social recognition of them as “good devotees,” because the devotional community recognizes the value of proximity. The social hierarchy of the guru community is based on a pyramid of proximity. The closer one is in proximity to the guru, the more institutional power one has and vice versa; the more institutional power one has, the more proximity one is granted. In various domains, those closest to the figure in power, in Weber’s terms the “charismatic aristocracy,” wield extraordinary power and are similarly governed by the haptic logics of proxemic desire, as they function as gatekeepers and spokespersons for the guru.

Within this hierarchical pyramid, subordinates are expected to desire proximity to those in more powerful positions along the chain of charismatic aristocracy, leading up to the guru. Such a system easily lends to abuses, wherein the powerful can take advantage of the proxemic desires of the neophyte. These haptic logics do not always result in sexual abuse, but when it does occur, they create serious barriers to the vindication of victims. In countless examples of guru sex scandals, fellow devotees characterize physical contact and private sessions with the guru as a blessing and reject victims’ allegations of abuse. When Shyama Rose told her mother of Prakashanand Saraswati’s sexual advances to her as a pre-adolescent, her mother viewed the special contact with the guru as a blessing and told her to “just enjoy it.”

Allegations of abuse represent the refusal of proximity to the guru, in essence, a refusal of the social conventions that govern the guru-disciple relationship. As a result, most victims become ex-devotees and fellow devotees often blame victims for their rejection of the guru. Within this system of haptic logics, one can imagine a powerful charismatic leader saying something like “when you’re a star, they let you do it.”

Featured image credit: “Photographed in Kolkata” by Biswarup Gangly. CC.BY.3.0from via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Desires for power: sex scandals and their proliferation appeared first on OUPblog.

Place of the Year 2018: Mexico, a year in review

January: In mid-January, a group of divers from the Gran Acuifero Maya (GAM) project connected two underwater caverns in eastern Mexico, revealing what was believed to be the biggest flooded cave on the planet. This discovery could potentially inform more about the ancient Maya civilization and lead to further understanding of the development of the people’s culture in the region prior to the Spanish conquest.

February: In February, a magnitude 7.2 earthquake struck southeastern Mexico, with the epicenter in the state of Oaxaca. 348 kilometers (216 miles) away from the epicenter in Mexico City, the earthquake could still be felt. Later in the day, a magnitude 5.8 aftershock struck the Oaxaca area again.

March: Mexico, the United States, and Canada formally submitted their joint bid to host the 2026 FIFA World Cup in March. It was announced in June that they were successful in their venture, and that the World Cup will return to North America in 2026.

April: In April, Mexico and the European Union reached an agreement on a new free trade deal. The new deal added farm products, additional services, investment and government procurement, included provisions on labor and environmental standards, and efforts to fight corruption.

May: In a rare political move, all four of the presidential hopefuls in Mexico banded together in May to make a statement to United States President Donald Trump, demanding protection for Mexican citizens whose lives have been negatively affected by the President’s crackdown on immigrants. Front-runner and eventual President-elect Andrés Manuel López Obrador said, “We will look for a relationship with the United States based on mutual respect, not subordination. We won’t be subordinate to Trump or to any other foreign government.”

June: Mexico defeated defending World Cup champion Germany in a surprise victory in June. While it was initially reported that fans had been celebrating and jumping with such force that they set off earthquake detectors, it was later discovered that there was, in fact, an earthquake.

July: General elections were held on 1 July, where the voters of Mexico elected a new President. Andrés Manuel López Obrador won the election with over 50% of the vote, winning the most states by a candidate since Ernesto Zedillo won every state in the 1994 election. His 6 year term in office began on 1 December 2018.

August: On 1 August, an Aeroméxico passenger plane crashed in the capital of Mexico’s Durango state just moments after take-off. While many were injured, all 103 passengers and crew-members miraculously survived the crash.

September: The number of family members arrested at the US-Mexico border rose to roughly 16,658 in September, a 31 percent increase over the previous month, and the most recorded in a single month since fiscal year 2012 when the Border Patrol started compiling records.

October: The US, Canada and Mexico reach a new trade deal, the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), to replace the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA).

November: Tensions at the United States and Mexico border came to an all-time high as US border guards fired tear gas in an effort to stop migrants from crossing the border. This was after 500 migrants on the Mexican side of the border overwhelmed the police blockades at a major US-Mexico border crossing in San Diego.

December: Former Mexico City mayor Andrés Manuel López Obrador was sworn into office as Mexico’s first leftist president in seven decades on 1 December 2018. At the ceremony he pledged to end corruption and impunity to transform the nation on behalf of the poor and marginalized. At the time of the ceremony in the country’s parliament, his approval ratings were 56%, 32% higher than his predecessor Enrique Peña Nieto.

Featured image credit: Torre Latino Mexico City by TildeStudio. CC0 via Pixabay .

The post Place of the Year 2018: Mexico, a year in review appeared first on OUPblog.

What do you value most in life? [quiz]

A character virtue is a core characteristic in human nature. Cross-cultural research has found that character virtues are grounded in biology, as they are the characteristics of humanity that survived the evolutionary process because they aid us in solving important tasks necessary for survival of the species. The six character virtues defined by psychologists are wisdom, courage, humanity, justice, temperance, and transcendence.

Everyday choices are guided by a person’s strongest character virtue, and show what they value most in life. This personality quiz,based on a psychometrically validated personality test developed by expert psychologists, will help you discover what your defining character virtue is and how it can help guide your future life choices.

Questions adapted from Character Strengths and Virtues: A Handbook and Classification

Featured image credit: “Take this flower” by Evan Kirby (@evankirby2). CC0 via Unsplash.

The post What do you value most in life? [quiz] appeared first on OUPblog.

December 14, 2018

Improvising with light: Nova Express psychedelic light show

Paul Brown is best known for his work as an artist creating visual art that uses self-generating computational processes. Yet before Paul started creating art with computers, he worked with Nova Express, one of the main psychedelic light shows performing in Manchester and the North of England during the 1960s and early 1970s. Nova Express had been founded by artist Jim MacRitchie and they were later joined by Les Parker. They played with groups such as Pink Floyd, The Who, The Nice, Canned Heat, Barclay James Harvest, Edgar Broughton, and others. I met up with Paul at the British Computer Society in Covent Garden for a conversation about this earlier period of his career.

What separated Nova Express from other light shows in the area was a more sophisticated improvisational approach to performing with light. “Jim and I developed a technique where rather than just putting projections and stuff up and then standing back and listening to the band, we actually played the projectors as instruments. We were like a visual rock band and would rap and harmonise with the music, fading images in and out on the projectors using our fingers. We were working rhythmically with the groups so that the lights were all happening in synchronisation with the music.” These dynamic performances earned the approval of bands, managers, and promoters, leading to bookings at nightclubs and universities across the North. As Paul recounts, some bands even refused to work with anyone except Nova Express, and they developed special relationships with groups such as The Nice who were keen to engage in audio-visual jamming sessions.

Technically, the group would mix turbulent inks in glass clock faces on overhead projectors, and also devised various other innovative approaches using slide projectors. “What you would do is get one piece of glass, get some drops of different colours of Vitrea glass paint add a few drops of ether, put another glass on the top and, as it heated up in open gate of a Aldis slide projector it would go absolutely crazy!” Another technique involved sealing oil and water-based dyes in between two thin pieces of circular glass, which could then be rotated inside a projector with the slide mechanism removed. Paul created transparencies of his own moiré patterns on Kodalith film, and developed slides of his own photography, experimenting with hot developer fluids to produce interesting effects. The group would also project existing 16mm movies over the top of the various psychedelic moiré patterns and textures.

While today’s digital light shows typically use frequency analysis to link motion graphics to the bass, middle and treble frequencies, Nova Express divided labour so that each projectionist would follow different parts of the music.

While today’s digital light shows typically use frequency analysis to link motion graphics to the bass, middle and treble frequencies, Nova Express divided labour so that each projectionist would follow different parts of the music. “We’d each have our favourite instruments, projectors, and set of slides, so we’d each play our own materials, but we would play very much together as a group. Les was very interested in basslines, so he’d be playing to that using kind of sombre colours. I was much more interested in the lead stuff, and so I’d be playing dynamic moiré patterns in very bright and fluorescent colours following the lead instruments. Then Jim would be doing the percussion and rhythm sections, so we could produce these very rich visual spectacles”. Fascinatingly, Nova Express were not only interested in synchronising sound and image, but also in creating forms of “visual syncopation” where “one rhythm would be going into the eyes and another rhythm would be going into the ears”.

Given the popularity of hallucinogenic drugs such as LSD in the sixties gig scene the group were operating in, I am intrigued to hear if Nova Express were taking inspiration from drug experiences directly, or trying to elicit psychedelic experiences for their audiences. “Absolutely”, says Brown. “We were using drugs. Interestingly enough, because we worked so hard, we were taking a lot of speed, and that would just keep us alert, you know, so we could do like an hour and a half non-stop of very, very fast work over red-hot projectors. But we were also taking a lot of psychedelics and stuff and, of course breathing in all that ether! We used psychedelic imagery that was lifted from all over the place, and we saw our contribution as being part of the psychedelic visual experience. We felt very committed to that, as a group, and felt it was part of our aesthetic.”

Paul ultimately sees the combination of sounds and visuals in the gig setting as key to producing powerful experiences for the audience. “What I realised was, if you get an audio feed, for the audio processing part of your brain, and you have your visual feed, for the visual processing, it really boosts the experience. We were able to take the audiences to spaces where they’d be just out of their heads, they wouldn’t have to do drugs, they could just watch and listen.” It’s a formula that has seen enduring popularity with the rise of what would eventually be known as VJing – where an artist mixes video as a complement to the music at live concerts and music festivals – and Nova Express can now retrospectively be counted as one of the early pioneers of this form in the analogue era.

Sample lightshow image 01, photo © Paul Brown c.1969.

Sample lightshow image 02, photo © Paul Brown c.1969.

Sample lightshow image 03, photo © Paul Brown c.1969.

Sample lightshow image 04, photo © Paul Brown c.1969.

Typical projector setup 01, photo © Duncan Curtis c.1973.

Typical projector setup 02, photo © Duncan Curtis c.1973.

Featured image credit: Sample Nova Express lightshow image, photo © Paul Brown c.1969. Image used with permission.

The post Improvising with light: Nova Express psychedelic light show appeared first on OUPblog.

Did emotional appeals help to win the Brexit referendum?

“[Brexit] was a big fundamental decision: an emotional decision,” said Nigel Farrage in an interview with The Guardian’s John Harris in September 2018. For once at least the former UKIP leader, a key figure in the campaign to Leave the European Union, was 100% right.

Since the shock result of the referendum in June 2016, the Government’s tortuous attempt to successfully disengage the UK from the European Union has effectively been the only news story. Indeed, Brexit coverage in traditional media has been so extensive it could probably be measured in print hectares and broadcast months, while debate in online channels has been both exhaustive and exhausting.

Yet, one aspect that has been largely absent from these discussions thus far is the contrasting approach taken by the respective election campaigns for Leave and Remain. With demands for the so-called People’s Vote gaining traction (effectively, a re-run of the 2016 referendum on the grounds that the reality of Brexit is now clear) understanding why Leave’s campaign was so much more effective is vitally important, and particularly for Remainers hoping for a reverse second time around.

In truth, it is not particularly surprising that the campaign methodologies have not been subjected to scrutiny. Academically and commercially speaking brand communication can be considered essentially ahistorical. The discipline is entirely forward-looking: it is interested in how to do things, not how they were done and has very little to say about its own past outside beyond the memoirs of its great men and women. For example, despite its considerable influence on commerce and culture during the late twentieth century, there are no extant histories of the UK’s public relations industry during this period.

Largely for this reason, social scientists tend to be suspicious of brand communication’s academic literature. They openly ignore its methodologies, conflate all of its diverse activities to advertising, and only occasionally concern themselves with its output. Even in these rare instances, research is primarily concentrated on the impact and effects of advertising rather than the matter of its conception.

Research into brand communication has been almost exclusively concerned with the way the campaigns were executed; for example, Leave’s strategy to dedicate much of its marketing spend to social media activities.

This has certainly been the case with Brexit. Research into brand communication has been almost exclusively concerned with the way the campaigns were executed; for example, Leave’s strategy to dedicate much of its marketing spend to social media activities. The conclusion drawn is that the Remain campaign would have enjoyed more success if it had adopted a similar social media strategy. I’d argue that this would probably have made very little difference: an exercise in chucking good money after bad. This decision was undoubtedly important, however, as any marketer will attest, it’s not the media channel but the persuasiveness of the communication that you are pushing through it which matters above all else.

The first issue to resolve is whether we can be sure that the Leave campaign had a significant impact. Here I think that there is very strong argument to indicate that it did. Opinion polls from the time the referendum was first mooted in 2010 to the point at which the date was set and campaigning started in earnest, suggested the British public was evenly divided on the question.

In elections that are this close and where a simple plurality of the vote determines the victor, we know that outcome is ultimately decided by the swing voters. They are the primary target of most political activity during elections purely because, with their vacillating views, theirs is the only vote it is possible to influence. Those with an entrenched opinion do of course also consume campaign brand communication but they do so for a different reason: to reinforce rather than to inform their voting intention.

So, given that this was a bi-lateral vote, where opinion was fairly evenly divided, we can almost be sure that the Leave campaign made a difference. Estimates of the number of swing voters in the EU referendum vary but analysis of opinion polls reveals that at the time the date of the referendum was set by Prime Minister David Cameron (February 2016), around 19% of those intending to vote – some six million people – were undecided. That means that in order to play a decisive role, the Leave campaign would have to influence only around 12% of the voters, and conceivably as little as 10%.

On final thing to consider is that the academic literature on the subject of swing voters shows a high correlation between those with a low interest in politics, who do not consume political media, and a propensity to be an undecided voter. We are not talking about a group with strong views about immigration or national sovereignty let alone the Common Agricultural Policy, they are much more likely to be people who had previously given the European Union, and the UK’s membership of it, very little thought at all. Most of this group ended up voting Leave. The key question is not why but rather how was don’t care was made to care?

Featured image credit: Banksy does Brexit (detail) by Duancan Hull. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr .

The post Did emotional appeals help to win the Brexit referendum? appeared first on OUPblog.

December 13, 2018

The adventures of a nitrogen atom

You have more than six hundred muscles in your body. Pick one of those muscles at random—say one of the eight in your tongue. Its cells will contain protein fibers. These consist of long chains of amino acids, which in turn contain nitrogen atoms. Now pick, at random, one of those nitrogen atoms. For storytelling purposes, let us refer to it as Atom. It turns out that Atom has quite a history, as do all your atoms.

You became part of Atom’s story when Atom became part of yours. This probably happened long after you were born; indeed, it is unlikely that any of the atoms in your newborn self are still with you. Those atoms have departed, only to be replaced by others. And besides the replacement atoms, many other atoms have joined you; otherwise, you wouldn’t have grown as much as you have since emerging from your mother’s womb.

Atom would have entered you as a component of the food you ate—more precisely, as part of the proteins you consumed. It might, for example, have dwelled in a piece of steak. After you swallowed that piece, its protein molecules were torn into their constituent amino acids by your digestive system. Those amino acids then entered your bloodstream and the one with Atom was subsequently taken in by a tongue cell.

The steak would, of course, have come from a cow. Before becoming part of that cow, Atom might have been part of a clover plant that the cow ate, and before that, part of an ammonia molecule that the plant took in through its roots. Previous to that, Atom would have been part of a nitrogen molecule, drifting through the air. These molecules consist of a pair of nitrogen atoms, and they are the primary component of the earth’s atmosphere.

For Atom to move from a nitrogen molecule to an ammonia molecule required some radical chemistry. It might have taken place in the reactor vessel of a fertilizer factory: in the Haber process, nitrogen molecules are mixed with natural gas and steam under very high temperatures and pressures to produce ammonia. Alternatively, the nitrogen molecule to which Atom belonged might have been struck by lightning and thereby become part of an ammonia molecule. And finally, Atom could have become part of an ammonia molecule inside one of the rhizobia bacteria that lived on the roots of the clover plant that the cow ate.

It is conceivable, for example, that besides dwelling in you and maybe a cow, Atom might have spent time in, say, Napoleon and, long before that, in a dinosaur.

Before drifting through the atmosphere, Atom would have had many other adventures. It is conceivable, for example, that besides dwelling in you and maybe a cow, Atom might have spent time in, say, Napoleon and, long before that, in a dinosaur.

Push further back and we arrive at the moment of Atom’s “atomic birth.” Atom didn’t come into existence in the Big Bang, 13.7 billion years ago. That event yielded only hydrogen and helium atoms, along with a few lithium and beryllium atoms. The formation of other elements required the presence of stars, and the first of those would have appeared about 200 million years after the Big Bang. In those stars, hydrogen and helium fused to make heavier atoms, including nitrogen. Subsequent stars would have been even more efficient in their nitrogen production.

It is important to realize that Atom would have been formed not just inside a star, but in the very core of that star, where the pressure and temperature would have been incredibly high. Realize, too, that in order to become part of you, Atom had to be liberated from that star and that the only way this could happen was for it to blow up. The debris of that supernova event would have provided building material for the Sun, for its planets, and not to be forgotten, for yourself. This, in turn, means that Atom existed before our Solar System did. Conclusion: Atom, that randomly selected nitrogen atom in your tongue, is at least 4.5 billion years old.

One final thing to keep in mind is that Atom will go on to have new adventures after you die. If your body is cremated, the newly-liberated Atom might again drift through the atmosphere and might subsequently become part of an oak. If you are instead buried, Atom might come to reside in one of the muscle cells of a nematode worm that feeds on you.

It is unclear whether “you the person” will enjoy an afterlife, but there is every reason to think that someday, some of your constituent atoms will again play a role in the life process. We could, perhaps, think of it as your “atomic afterlife”?

Featured image credit: Atmosphere Representation Nitrogen by WikimediaImages via Pixabay.

The post The adventures of a nitrogen atom appeared first on OUPblog.

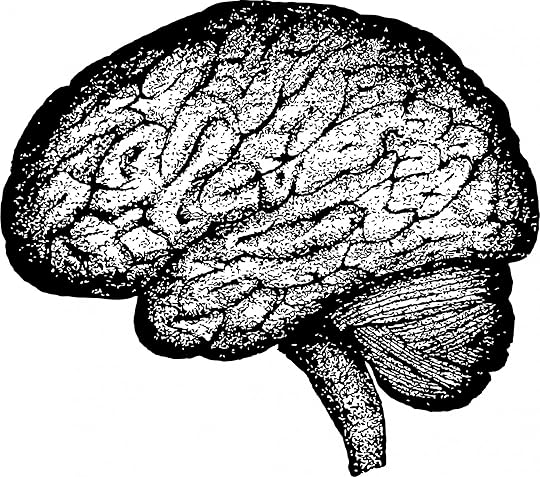

There’s a map for that: tracing pathways through the ever-changing brain

When I was in medical school, my fellow students and I all dreaded a single course, taught then in the second year—neuroanatomy. At my school, we had two famous neuroanatomy professors who had written competing textbooks on the subject and clearly disliked each other. One was known to be eccentric and the other mean. But the reason we dreaded the course was that we knew it would challenge the human capacity for memorization to the absolute limit. And given how many things a medical student is required to memorize, we were frightened.

The brain is comprised of about 80 billion neurons and an equal number of three other types of cells: astroglial cells, oligodendroglial cells, and microglial cells. The neurons send out processes called axons that connect with dendrites on other neurons, forming trillions of connections called synapses. Some axons travel distances of only millimeters while others run for several feet from the brain to other parts of the body. Within the brain, there are many different substructures, each connected by axons and dendrites to multiple other substructures. In the 1970’s, neuroanatomy courses meant memorizing something that looked as complicated as the New York City subway map.

The human brain has approximately 80 billion neurons and trillions of synaptic connections. Image credit: Human Brain by Dawn Hudson. CC0 via Public Domain Pictures.

The human brain has approximately 80 billion neurons and trillions of synaptic connections. Image credit: Human Brain by Dawn Hudson. CC0 via Public Domain Pictures.We were taught that if you disrupt this pathway going from this region to that region, the ability to move the left arm below the elbow would be lost. Hitting a pathway in another part of the brain meant losing the ability to understand, but not generate speech. If you cut the nervous supply at the level of the spinal cord in a particular spot, a person would no longer be able to feel a pinprick to the front of the right thigh, but vibration to that area would not be affected. We sat up long nights, often in groups, trying to remember all of this because that is what we would be asked about on the many tests our two professors loved to give.

Through all of this, we were too scared and exhausted memorizing the names of brain regions and pathways to ask a fundamental question: if the brain is laid out like a fixed series of subway stations and tracks, how is it that we can learn something new? It must be the case that something is capable of changing somewhere in the brain to accommodate the fact that we continue to learn and remember things through our lives.

Indeed, thanks to Eric Kandel, who became a professor at my medical school after I had graduated and joined the faculty myself, and to many other neuroscientists through the second half of the twentieth century, we learned that the brain is an incredibly adaptive, plastic organ, capable of responding and changing every time we see something new, learn a new fact, or experience a new emotion. Yes, our brains are programmed by genes that tell neurons where to go as it develops in utero, but those same genes are turned on and off throughout life whenever we have an experience. After all, even the ancient New York City subway system is subject to change; we just got a brand new line on Second Avenue and new cars are continuously being added to existing lines.

Unfortunately, that also means that adverse life experiences can damage the brain. Studies continue to show that traumatic early life experiences lead to reductions in brain volume in certain key areas of the central nervous system. Early life adversity also changes the strength of connections among various brain regions and the degree to which groups of neurons are activated throughout life.

A scientific illustration of how epigenetic mechanisms can affect health. Image credit: Public Domain via National Institutes of Health.

A scientific illustration of how epigenetic mechanisms can affect health. Image credit: Public Domain via National Institutes of Health.Changes in gene activation in the brain occur in part through a process called epigenetics (below). Although we are born with most of the DNA sequences in our genes we will ever have, molecules such as methyl and adenyl groups bind to our DNA or the proteins that surround DNA and alter the expression of those genes. For example, one recent study showed that epigenetic modifications of a receptor for the brain neurotransmitter dopamine have an effect on IQ scores.

Because traumatic early life experiences clearly predispose people to developing psychiatric illnesses like depression, anxiety disorders, and schizophrenia, scientists have spent the most time examining the effects of stressful life events on brain function in both laboratory animals and humans. But positive experiences—indeed, each and every experience—affects brain function. And that means that it is possible that a positive life experience like a successful course of psychotherapy might be able to reverse structural and functional abnormalities in the human brain.

In the last half-century, we have come an enormous distance in understanding that the brain is not an organ whose functions are written in stone, but rather a dynamic collection of genes, molecules, cells, and pathways, all of which are modified on a second-by-second basis. So far, we have the most information about the profound ways that early life adversity affects brain structure and function, and that information is proving extremely useful in developing new ways to intervene with psychiatric illnesses, both with medications and psychotherapy. As research develops, we will also learn more about how to reinforce the effects of positive life experiences on the brain.

Of course, this new information about the brain makes it even more complex than we originally thought, so studying neuroscience in medical school (instead of just neuroanatomy) may still be scary to students. But it is now far more interesting than it was for me.

Featured image credit: Nerve Cell by ColiN00B. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post There’s a map for that: tracing pathways through the ever-changing brain appeared first on OUPblog.

Making music American: a playlist from 1917

The entrance of the United States into World War I on 6 April 1917 inspired a flood of new music from popular songwriters. Simultaneously, the first recording of instrumental jazz was released in April 1917, touching off a fad for the new style and inspiring record companies to promote other artists before year’s end. Victor and Columbia, the industry leaders, developed technological innovations that made possible the first recordings of a full symphony orchestra. These recordings are a sample of the rich variety of recordings released in this era.

“Livery Stable Blues” by Original Dixieland Jazz Band (Victor 18255)

Recorded on 26 February in Manhattan, the first jazz instrumental recording benefited from innovative techniques by Charles E. Sooy and his team of Victor engineers. In order to capture all five instruments with clarity, they placed each musician at a different distance from the recording apparatus. The resulting record was so different from anything else on the market that it took the country by storm when it was released on 15 April, eventually selling a million and a half copies.

“Indiana” by Original Dixieland Jazz Band (Columbia A2295)

Following a copyright dispute with Victor, the ODJB agreed to make a recording for rival Columbia, whose engineers did not take the same pains with instrument placement as the Victor engineers had done for “Livery Stable Blues.” Additionally, the company insisted that the band record a song by publisher Shapiro, Bernstein, and Company that they did not know. They were taught the song by a pianist in the publisher’s office, and they hummed the tune in their heads as they walked to the recording studio. The result was less than polished, but the number eventually became a jazz standard.

“Over There” by George M. Cohan, sung by Nora Bayes (Victor 45130)

George M. Cohan (“the man who owned Broadway”) composed the iconic song “Over There” on 7 April, the day after Congress voted to enter the war. It was introduced to the public by popular vaudeville singer Nora Bayes in June. Her recording of the song made it popular nationwide later in the fall.

“In Flanders Fields” by Charles Ives

American experimental composer Charles Ives wrote this bracing setting of Canadian John McCrae’s well-known poem in April. Ives weaves allusions to American and French patriotic songs into the melody of his dissonant composition.

Schön Rosmarin by Fritz Kreisler

Among the numerous European artists who made their homes in the United States during World War I, few could rival the popularity of Austrian violinist Fritz Kreisler. His virtuosity and technical prowess were admired by connoisseurs, but it was sentimental Viennese tunes like this that appealed to the vast majority of listeners.

Étincelles by Moritz Moszkowski, played by Olga Samaroff (Victor 64995)

American-born pianist Olga Samaroff had studied in Europe and had deep ties to Germany. She was among the country’s most popular classical soloists during the war, and she later enjoyed a long career as a teacher and writer on music.

“Ride of the Valkyries” by Richard Wagner, arranged by Ernest Hutcheson and played by Olga Samaroff (Victor 74772)

Wagner’s music was extremely popular with American audiences, despite the efforts of propagandists to have it banned during the war. Here the famous “Ride of the Valkyries” is played by American pianist Olga Samaroff.

“Finale” from Symphony No. 4 by Pyotr Tchaikovsky, played by the Boston Symphony Orchestra under Karl Muck (Victor 6050)

During the summer of 1917, Victor engineers devised a method for recording a full symphony orchestra for the first time. At a recording session in early October, engineers Raymond and Harry Sooy (whose younger brother Charles had recorded the ODJB in February) captured the sounds of the Boston Symphony Orchestra in Victor’s Camden, NJ studio. By the time of the records’ commercial release in December, Karl Muck had been publicly criticized for his alleged loyalty to Germany, and Victor advertised the records without mentioning his name.

Hungarian Dance No. 5 by Johannes Brahms, played by the Philadelphia Orchestra under Leopold Stokowski (Victor 64752)

Later in October, Victor invited rising star Leopold Stokowski and his Philadelphia Orchestra to Camden for a recording session. When the first of these records were released in January 1918, Stokowski (the husband of pianist Olga Samaroff) was hailed as a genius. He went on to a sixty-year career as one of the world’s most popular recording artists.

“Danny Boy” sung by Ernestine Schumann-Heink (Victor 88592)

Austrian-born contralto Ernestine Schumann-Heink was among the most popular recording artists of the World War I era. Her record of “Danny Boy,” released on 1 January 1918, was especially affecting to listeners who knew that she had one son serving in the German navy and four sons in the US military.

“On Patrol in No-Man’s Land” by James Reese Europe, sung by Noble Sissle (Pathé 22089)

James Reese Europe, the well-known bandleader for Vernon and Irene Castle, enlisted in the New York National Guard’s all-black Fifteenth Infantry Regiment along with his friend Noble Sissle, a successful vaudeville singer. Under his leadership, the regimental band achieved great fame in France. Upon their return to the United States after the war, the band toured and recorded under the name “Harlem Hellfighters.” This recording features Europe’s most popular song about their combat experiences, sung by Sissle.

“How ya Gonna Keep Down on the Farm, now that They’ve Seen Paree?,” played by the Harlem Hellfighters Band

James Reese Europe’s band played a wide range of musical styles in concert and on recordings after the war. This song was one of their most popular, encapsulating the changes that had taken place in American society as a result of the war.

Featured Image credit: James Reese Europe and his band play American jazz for hospital patients in Paris, 1918. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Making music American: a playlist from 1917 appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers