Oxford University Press's Blog, page 212

November 27, 2018

What can psychology tell us about music?

Music can intensify moments of elation and moments of despair. It can connect people and it can divide them. The prospect of psychologists turning their lens on music might give a person the heebie-jeebies, however, conjuring up an image of humorless people in white lab coats manipulating sequences of beeps and boops to make grand pronouncements about human musicality.

In truth, that’s historically rather how music psychology used to work. In the early 1900s, elaborate mechanical apparatus were devised that purported to determine a child’s musical potential by measuring their perceptual acuity on tasks such as loudness discrimination. Measuring musical aptitude with performance on an acoustic judgment task misses out on what might be even more essential factors—say, the degree to which music captivates a child’s attention or inspires them to move.

But contemporary work on music perception embraces a variety of disciplines and methodologies, from anthropology to musicology to neuroscience, to try to understand the relationship between music and the human mind. Researchers use motion capture systems to record people’s movements as they dance, analyzing the gestures’ relationship to the accompanying sound. They use eye tracking to measure changes in infants’ attentiveness as musical features or contexts vary. They place electrodes on the scalp to measure changes in electrical activity, or use neuroimaging to make inferences about the neural processes that underlie diverse types of musical experiences, from jazz improvisation to trance-like states to simply feeling a beat.

One particularly interesting recent example from Nori Jacoby and Josh McDermott takes its methodological inspiration from the game of telephone. In this familiar diversion, one person whispers a sentence to another, who in turn whispers it to someone else. The whispered exchanges continue until the message winds its way back to the original speaker, who often finds the content radically transformed. In Jacoby and McDermott’s task, participants hear a random rhythm and are asked to reproduce it as closely as possible by tapping along with it. The pattern of taps they produce is then played back to them as the next rhythmic sequence they’re asked to match, and so on and so forth in a kind of game of tapping telephone. Across the course of this iterative process, tapping patterns settle into rhythmic structures common in the participants’ musical environment. By examining how these structures change from place to place, this research can illuminate the interrelationship between culture and a person’s sense of time.

This design relies on a relatively widespread musical behavior—rhythmic tapping—rather than a potentially unfamiliar and awkward task like providing overt ratings of acoustic features. By randomly generating the initial seed rhythms, this task also avoids the kinds of inadvertent cultural biases then can creep into the selection of materials for experiments in music perception. These strengths enable the research design to be used successfully in places around the world where musical styles and practices differ from one another, permitting insight into the interrelationships between perceptual tendencies and the characteristics of the music to which people listen most frequently.

Image credit: “Audio e guitars” by Snapwire. CC0 via pexels.

Image credit: “Audio e guitars” by Snapwire. CC0 via pexels.Through close partnership with people who make music as well as people who study it from the perspective of the humanities, scientific approaches to music are increasingly focused on aspects of musical experience that extend beyond beeps and boops, like exploring the cognitive processes that underlie the experience of musical groove, or trying to understand the role singing plays in interactions between infants and their caregivers.

At several sites around the world, including the McMaster Institute for Music and the Mind in Hamilton, Ontario, and the Max Planck Institute for Empirical Aesthetics in Frankfurt, Germany, concert halls have been specially constructed to allow both for musical performances and for scientific inquiry. They feature seats that have been outfitted with physiological measurement systems, stages that incorporate motion capture systems, and other tools that make it possible to study experiences sustained at public performances and in participatory music making sessions. This work has even fed back into new kinds of composition and performance, in which features of the sound change depending on the heart rate of the audience members as the concert progresses.

Some lines of research explore potential clinical applications of music, ranging from benefits for gait and coordination in movement disorders, to memory effects in dementia, to speech facilitation in aphasia. Other lines of research identify new ways to make music, ranging from Rebecca Fiebrink’s systems for creating music out of intuitive hand gestures to Gil Weinberg’s robots that can improvise along with human partners. Still other studies try to peel apart the influence of exposure and context to understand the way music does and does not communicate across social boundaries.

With its long, sometimes checkered, but uncommonly close relationship between people in the arts, humanities, and sciences, research in music cognition has the potential to serve as a model for integrating multiple intellectual frameworks in order to address humanity’s big questions.

Featured image credit: “Music Melody” by MIH83. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post What can psychology tell us about music? appeared first on OUPblog.

November 25, 2018

Meet the editors of International Studies Quarterly: a Q&A with Brandon Prins and Krista Wiegand

Brandon Prins and Krista E. Wiegand will become the new lead editors of International Studies Quarterly, the flagship journal of the International Studies Association, in 2019. We asked them about trends in international studies scholarship and teaching, what global issues aren’t getting the attention they should, and their goals for the journal.

Oxford University Press: What trends do you see in international studies scholarship and teaching?

Brandon Prins: New methodological tools and data collection projects have transformed research and teaching in international studies. The incorporation of geographic information systems, remote sensing, crowdsourcing, machine learning, and other computational tools not only help us collect and process new information. These things can also facilitate interdisciplinary collaboration. The hope is that such teamwork can bring valuable insight to critical challenges the global community confronts and motivate student interest in international studies.

Krista Wiegand: In recent years, there has been a major initiative to bridge international studies with the policy making world by synthesizing academic research and providing it to policy makers through blogs, policy briefs, and op-eds. This has been a positive trend and hopefully more academic research, including research published in our journal, will inform foreign policy in the U.S. and other states.

OUP: What global issues aren’t getting the attention they should?

BP: I would like the journal to increasingly reach scholars in developing countries and reflect their experiences and speak to the problems they confront.

Image credit: used with permission of Brandon Prins.

Image credit: used with permission of Brandon Prins.KW: Though there is some very good research on the political aspects of environmental issues such as climate change and resource scarcity, it seems like this is a topic that more international studies scholars should be considering. There are so many potential political consequences of climate change and resource scarcity, particularly civil wars, poverty, and the role of international institutions, that could be explored much more by international studies.

OUP: What led you to the international studies field?

BP: Questions of conflict and cooperation ground international studies and these questions always struck me as fascinating and significant. Further, international studies for me has always involved multiple issue areas and consequently connected me to scholars in other disciplines who ask similar questions but from different theoretical and methodological perspectives.

KW: My interest in international studies began my freshmen year in college when Lebanese friends of mine had relatives killed in the Lebanese civil war. Learning about this war and many other armed conflicts sparked my interest in the causes of civil and interstate wars, international disputes, and conflict management. I’m particularly interested in issues that groups and states fight over, such as territory, ethnic identity, and economic resources.

OUP: What makes International Studies Quarterly unique?

BP: The journal is meant to publish the best research across the full-range of scholarship we have in the International Studies Association. In this way, each issue of the journal allows a reader to find specific topics of interest but also discover new puzzles, approaches, and methodologies. This diversity sets the journal apart.

Image credit: used with permission of Krista E. Wiegand.

Image credit: used with permission of Krista E. Wiegand.KW: The journal is unique in that it provides the best overview of cutting-edge research in the field of international studies, ranging from highly empirical research to in-depth case studies to experimental research. As the flagship journal of the International Studies Association, the publication publishes research that influences trends in the field for years to come.

OUP: What goals do you have for International Studies Quarterly?

BP: My goals are simple: I want to publish the best, most innovative, and most engaging research being done in the field of international politics.

KW: My goals for the journal are to provide readers with outstanding research that can be highly utilized, promote submissions from women scholars and scholars in developing countries, and to increase the impact of the journal in the field.

OUP: The International Studies Association’s 60th Annual Convention is coming up in March 2019. What are you looking forward to at the convention?

BP: I go to every convention hoping to learn something new and 2019 will be no different. The convention is an opportunity to discover novel research projects that may help me in my own work.

KW: I am most looking forward to participating in roundtables about journal editing and peer review. I am a strong advocate of improving the culture of peer review in our field. In my role I hope to have some positive influence on scholars who are not certain about the peer review process done by journals and the best practices that reviewers can use.

Featured image credit: Earth Blue Planet Globe by Wikilmages. CC0 via Pixabay .

The post Meet the editors of International Studies Quarterly: a Q&A with Brandon Prins and Krista Wiegand appeared first on OUPblog.

Dynasties: lions with pride

Lions are arguably the most respected and feared creatures of the animal world, the males fighting with rivals and protecting their pride, while the lionesses are adept hunters who catch enough food for the whole pride.

It is no surprise that their group structure has once more been examined in BBC’s Dynasties. To accompany this week’s episode at the midpoint of our blog series, enjoy our ten facts about the interaction between these fierce beasts of the savanna.

More social = more territoryLions haven’t always lived in prides; this is a practice that has evolved over thousands of years. Sociality has evolved as a way to hold onto territory: lions are more likely to form prides than live in smaller roaming groups as the value of their landscape increases, i.e. there are more resources available in the area, such as prey and water. In these circumstances it is more worthwhile to form a large pride in order to prevent the area being taken over by rivals.Pride size limitations

Following the fact above, you might expect that pride size varies in response to the amount of food available. However, recent research has revealed that competition for land – after its availability has been limited by flooding – is a greater limiting factor for pride sizes than the amount of prey that resides nearby.Part-time prides

Contrary to popular belief, lions don’t live together in prides 24/7, but instead have a fission-fusion group dynamic, in a similar way to chimpanzees. Each lion may spend weeks living independently, or as part of a small subgroup, before re-joining their pride. One reason for this is to participate in hunting for their food.Fierce female hunters

Did you know that the majority of hunting is carried out by lionesses, either alone or in pairs? If the prey is particularly difficult to catch – for example, when the prey lives in harsh environments or if the animal is much larger than them – the group of hunters may be larger, but for the most part a couple of lionesses will fell the prey while the rest of the pride watches from a distance, waiting for dinner to be ready.

Image credit: Lion Aggressive Threat by MonikaP. CC0 via Pixabay.The hierarchy of feasting

Image credit: Lion Aggressive Threat by MonikaP. CC0 via Pixabay.The hierarchy of feastingWithin a pride, a strict hierarchy is enforced at mealtimes. First, the males will claim the largest portions, followed by the females (who will have caught the kill), and finally the cubs. This hierarchy is taught to cubs from early on – they learn to expect a telling-off if they try to sneak in early!Nomadic males mean danger

When they mature, male lions leave the pride they were born in and live as nomads. These nomadic males may eventually decide to take over another pride, fighting and ousting the reigning king, or kings. When they succeed, the new kings kill any cubs in the pride which may have been fathered by the former males in order to assert their dominance and ensure all cubs within the pride are their own.

Image credit: Mother and daughter by Tambako The Jaguar. CC BY-ND 2.0 via Flickr.Unequal nomad partnerships

Image credit: Mother and daughter by Tambako The Jaguar. CC BY-ND 2.0 via Flickr.Unequal nomad partnershipsNomadic males often live and hunt in pairs, or as a small group. However, in these male ‘partnerships’ there is often inequality, with one partner typically receiving over 70% of all matings and 47% more food than the lesser partner. Despite this subordination, the partnership is beneficial for both lions, with the ‘beta’ male possessing higher reproductive fitness than the average single male nomad.Cooperative mothers

Lionesses within the same pride who have cubs at a similar time are often seen helping each other care for the cubs, working together to ensure the pride’s survival. However, mothers tend to reserve their milk for their own cubs, showing slight favouritism towards their own offspring.Big cat cohabitation

Did you know lions share their habitat with leopards? You might think this causes conflict between the two species of big cat, but their diets differ enough that they don’t cross paths too often: lions typically favour large- to extra large- sized prey, such as buffalo, while leopards prefer small- to medium- sized prey, such as impala.Can lions and humans coexist?

Due to human pressures, the territory of lions has declined by 75% over the years. Lions have adapted to coexist alongside humans by responding to their seasonal movements: they will move away from settlements when humans are living there, as they experience less stress the further away they are from densely populated human areas. Thus, peaceful coexistence is best maintained if humans keep their distance from these big cats.

Featured image credit: Lion pride by suebrady5. CC0 via Pixabay .

The post Dynasties: lions with pride appeared first on OUPblog.

November 24, 2018

Immigration, the US Census, and political power

As I write these lines, a key court case has begun in New York. That case centers on the US Census. At issue is the Trump administration’s addition of a question to the Census which will ask people whether they’re US Citizens. This seemingly innocuous question highlights a longstanding theme in US political life—the relationship between mathematics and political power.

The purpose of the US Census is to count, “enumerate” is the exact word found in the constitution, the US population, and this should be done every ten years. Also, the relevant provision of the constitution, Article 1 Section 2, says nothing about a distinction between citizens and non-citizens. In fact, the only distinctions made are among free persons, Indians, and “three fifths of all other persons,” an obvious reference to slaves. The results of the Census serve a number or purposes, but I’ll just focus on one: apportionment.

Apportionment is the process of allocating seats in the US House of Representatives to the 50 states. That is, each state gets assigned a specific number of seats in the House and is, therefore, entitled to send that number of congresspersons to Washington. The key, however, is that the number of seats a state gets depends on its population—the bigger a state’s population the more seats it gets and, therefore, the more congresspersons it gets to send. And this can affect outcomes as crucial as how much federal money the state receives or the number of electoral votes it gets in Presidential elections. So, states have a keen interest in having their populations correctly counted. And this is where the Trump administration’s addition of a citizenship question comes in.

The key, however, is that the number of seats a state gets depends on its population—the bigger a state’s population the more seats it gets and, therefore, the more congresspersons it gets to send.

A worry among demographers, as well as others, is that addition of such a question will discourage immigrants, including documented ones, from filling out the form. If this were to happen, it would result in undercounts in states, like New York and California, with large immigrant populations. And because of what I said about the relationship between the census and apportionment, these states might end up with fewer seats in the US House of Representatives.

For those worried about the dilution of political power I just referred to, another area of mathematics could conceivably come to the rescue: statistics. Even though to many, statistics is a dreaded evil, it’s an extremely useful evil. It’s a discipline which has developed, among other things, several methods designed to deal with just the type of problem I’ve been discussing.

This isn’t the place to go into the technicalities of these methods. Those interested in them can follow up. Suffice it to say that some of the methods in question rely on estimates of population using birth certificates, death certificates, and other vital records, while others draw upon various sampling techniques. The main point for this post, however, is that mathematical technicalities are often also matters of raw political power. The methods used by census statisticians to address undercounts, because of their implications for apportionment, could mean the difference between whether a state gets that federal transportation grant it wants or whether it’s decisive in electing a President.

The use of statistical methods to adjust for enumeration errors in the census has for years been a major point of contention. Advocates of these methods have been worried that undercounts will result in less representation for certain groups, especially blacks and immigrants. Those who’ve opposed their use have focused on what they see as their unconstitutionality. That is, they’ve said the constitution requires us to count people not use statistical gimmicks to estimate them. Advocates of methods of adjustment have responded by arguing that opponents are using the constitutional argument as an excuse to disenfranchise members of “minority” groups, as well as others who reside in states many of these minority group members call home. As I’ve said, this debate has been going on for quite some time. Trump’s addition of a citizenship question is likely to intensify it.

Featured image credit: Neon HD by Karolina Szczur. Public Domain via Unsplash .

The post Immigration, the US Census, and political power appeared first on OUPblog.

November 23, 2018

The politics of “political” – how the word has changed its meaning

Over the course of history, the word “political” has evolved from being synonymous with “public sphere” or “good government” to meaning “calculating” or “partisan.” How did we get here? This adapted excerpt from Keywords for Today: A 21st Century Vocabulary explains the evolution.

The problems posed by political result from a combination of the term’s semantic shift over the last several centuries and the changing face of post-national politics that have become so important since mid-twentieth century.

One hallmark of modern politics is its asymmetry. Whereas the political was formerly imagined as practically synonymous with the public sphere, and with conflicts between institutions or nation states, now it can just as frequently designate conflicts between an individual and an institution, or between a non-national group and an ideology (e.g., between G8 protestors and police in various countries, or between the Taliban and ‘the west’). This shift has affected the linguistic fortunes of the words politics and political, as the adjectival and nominal forms have developed different connotations over the last several decades.

The adjective political has developed to have two relatively exclusive meanings. Political has supplanted the now largely archaic adjectival form politic. Both forms derive ultimately from Greek polis, initially a city-state and then later, by extension, the body politic. In medieval usage, the adjective politik connoted that which was prudent, sensible, and sagacious, a meaning that continued even as the usual form migrated to political. The political as a realm of public speech was imagined as elevated and righteous, often contrasting the perceived benefits of constitutional governments against the characteristics of despotism or tyranny. In the mid eighteenth century, for instance, David Hume, in A Treatise of Human Nature, described the “security and protection, which we enjoy in political society” (1740), and a character in Oliver Goldsmith’s novel The Vicar of Wakefield (1766) shudders lest this rarified sphere be degraded by expanding suffrage. From the sixteenth century onward, another set of meanings came to be attached to the term: against its more elevated connotations, political came to mean “cunning” or “temporizing.” Today, the political sphere may more readily be imagined as contaminating the common man rather than the other way around. To call someone “political” is rarely a compliment. The adjectival form that once connoted good government, which was synonymous with “judicious” and “insightful,” now activates an altogether different set of connotations: “calculating” and, perhaps more of a piece with our political moment, “partisan.” The crux of this semantic fall from prudence to mere expediency seems to lie in a correlative historical shift: politics, once viewed as a space of quasi-transcendental stability, is now viewed as an arena of profound contingency.

The adjectival form political has become weaponized in recent years, with more pervasive use of terms such as political animal and political agenda together with the advent of political correctness and the PAC, the political action committee that has taken over American politics in the wake of the 2010 Citizens United decision. (What does it mean that “political action,” rather than the government or an identifiable political party, is the primary engine of US politics now?). In the US, the noun politics seems to have been superseded in current usage by what we might call the “political plus noun” formula.

The metastasis of the “political plus” formulation reflects the shifting epistemological grounds on which political theory has traditionally taken its ethical stand. While it is beyond the scope of this entry to summarize the main schools of twentieth century political thought, some brief remarks may help to clarify the linguistic situation. Long gone is the idea of the political as the Aristotelian idea of the inclination toward the bonum apprehensum, that thing that is good in itself, a teleological ethics effectively eviscerated by Thomas Hobbes and the Enlightenment. The semantic shift of political might be viewed in light of Hannah Arendt’s interpretation of the political longue durée, in which the past, with its defining public sphere of active citizenship – politics as the realm of prudent discourse – was eclipsed by a modernity that had begun to look inward rather than outward, intent on the private pursuit of happiness and wealth. Within this paradigm, increasing inwardness results in a fracturing of political realities. A nostalgic follower of Arendt would ask: where has all the substantive political engagement gone? – yet the definitions of public and private assumed by Arendt seem insufficient to describe the recent multiplication of political. In particular it does not engage with one of feminism’s most insistent slogans: “the personal is political.”

What has happened is less that politics has migrated from the public to the private spheres and more that the political can take place in many different arenas, with many different types of agent participating simultaneously. We have moved from the sphere of politics to the political because the language needs to describe the contingency of shifting assemblages of political actors that do not fall completely or easily within a particular domain of discourse. Those actors may include institutions (the European Union, Burma), individuals (a chancellor), non-governmental collectives (WikiLeaks, the IRA), or even non-human actors (global warming). In such a world, the political, with its ability to follow the dust of migrating geopolitical animals, may seem a nimbler alternative to a more static, public sphere-identified politics.

Featured image credit: “Blue Building Pattern Freedom” by Pexels. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post The politics of “political” – how the word has changed its meaning appeared first on OUPblog.

Reflections on anthologising

The year was 1968 and I was a young postgraduate music student walking down King’s Parade in Cambridge when I saw the revered figure of David Willcocks, director of King’s College Choir, striding towards me. He had rock-star status in Cambridge and beyond, and although I knew him from his weekly harmony and counterpoint classes which I had attended, I wasn’t quite sure whether to nod politely, say ‘good afternoon, Mr. Willcocks’, or hurry past hoping he hadn’t noticed me. Fortunately, he spoke first. ‘Would you like to co-edit a second volume of Carols for Choirs with me, Mr. Rutter?’ There was only one possible answer, and that’s how my part-time career as an anthologist began.

Anthologising is one of life’s sweet pleasures, rather like throwing a party for your favourite friends. Imagine that, by a miracle of scheduling, there they all are in one room at one time, and as you circulate among them, you remember exactly why you wanted to be their friend in the first place, you probably remember the circumstances of your first meeting, and you are delighted to find that they haven’t changed a bit and you are still drawn to them. Also at the party are some new friends; you haven’t known them for as long, but you sense that they will remain your friends forever.

An anthology is a gathering of your friends. In the case of the sacred choruses collection I have just been editing, the room is a 384-page book—you can’t, of course, include everyone you would like to, but there’s still space for lots of friends. In many cases, I certainly remember when I first met them . . . The heavens are telling when I sang in my school performance of Haydn’s Creation as a piping 13-year-old treble, standing next to my chum John Tavener. Our hearts always lifted when we heard ‘turn to page 42’ and we rehearsed this (to me still thrilling) chorus. As I walked home after those rehearsals—it saved the bus fare—I walked on air. Or the Fauré Requiem: it was a set work for A-level and I took myself along to a local amateur performance to get to know it better. I remember experiencing an uncanny feeling that it would be a dear friend and companion on my life’s journey (it is). To this day tears come to my eyes when I conduct the In paradisum.

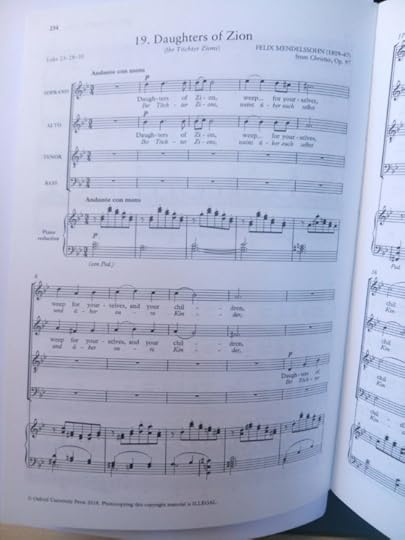

You never know when you might make a new friend. Last year I was browsing through the autograph manuscript of Mendelssohn’s unfinished oratorio Christus (I love composers’ manuscripts) when I happened on an exquisite chorus, Daughters of Zion, that I had never even heard of before. Welcome to the party, new friend!

Image credit: Daughters of Zion from Sacred Choruses.

Image credit: Daughters of Zion from Sacred Choruses.A party is private, an anthology public, but as host/editor, your hope is that others will enjoy your friends as much as you do. As a composer, I suppose I look upon my compositions as my children, but my anthology choices are my friends, and friends are important too.

Featured image credit: “OUP bookshelf” by Barbara Stuart, OUP.

The post Reflections on anthologising appeared first on OUPblog.

National Day of Listening [podcast]

In 2008, StoryCorps created National Day of Listening for citizens of all beliefs and backgrounds to record, preserve, and share the stories of their lives. This year, we invite you to celebrate by listening to our podcast, The Oxford Comment. During 2018, we’ve tackled issues from freedom of the press, to the rise of narrative non-fiction, consent on college campuses, and the global plastic problem.

Featured image credit: City traffic in New York Texas by Henry Be. Public Domain via Unsplash.

The post National Day of Listening [podcast] appeared first on OUPblog.

November 22, 2018

Anywhere, anytime: children’s exposure to alcohol marketing

“Marketing plays a critical role in the globalization of patterns of alcohol use among young people, and reflects the revolution that is occurring in marketing in general”

—The World Health Organization (WHO)

Alcohol is linked to over 200 medical conditions, causes a number of cancers and a raft of social issues that collectively place a major burden on society. Children are particularly susceptible to the harms from alcohol consumption due to their developing brains and inexperience regarding consumption risks. For example, early onset drinking is linked with various adverse psychological, physical, and social outcomes, such as alcohol dependence, neurological dysfunction, and risky/unwanted sexual interactions. Despite the harm alcohol can cause, there are currently little to no legislative regulations in place on alcohol marketing in many countries.

Marketing is a crucial aspect driving demand for alcohol, which is concerning given the billions of dollars spent by the alcohol industry on marketing every year. For example, Diageo, the largest global alcohol company, spent £1.8 billion on its global marketing strategy in the 2016/2017 financial year (50% of its operating profit). Alcohol marketing contributes to the worldwide burden of alcohol-related harm by promoting the misleading aspects of alcohol, normalising it as an ordinary commodity, and increasing overall consumption. Children are particularly susceptible to the misleading aspects of alcohol marketing and their exposure has been associated with increased consumption and hazardous drinking patterns.

Children are particularly susceptible to the harms from alcohol consumption due to their developing brains and inexperience regarding consumption risks.

The WHO recommends restrictions on alcohol marketing as one of the most cost-effective policy interventions for reducing alcohol-related harm. However, many jurisdictions still rely on self-regulatory models for alcohol marketing, in which the industry is responsible for creating, monitoring, and enforcing their own marketing codes. These self-regulatory systems have consistently failed at protecting children from exposure to alcohol marketing, leaving children vulnerable to the adverse effects of exposure.

Until recently, estimates of children’s exposure to alcohol marketing have relied on self-reporting measures that may not accurately quantify the extent of children’s exposure to alcohol marketing and thus the limitations of self-regulation. Using automated wearable cameras, we found that New Zealand children are exposed to alcohol marketing on average 4.5 times per day. Children were exposed to alcohol marketing in places such as the home, licensed outlets, and sports venues via a variety of promotions such as sports sponsorship, merchandise, and shopfront signage. Furthermore, Māori (the indigious people of New Zealand) and Pacific children had five and three times higher rates of exposure to alcohol marketing than Non-Māori/Pacific children, respectively. Disparities were mainly attributed to higher rates of exposure via off-licence outlets and sports sponosorship for Māori children.

This exposure occurred at a time when the New Zealand Government did nothing, despite being advised to increase restrictions on alcohol marketing by the Law Commission in 2010 and by the Ministerial Forum on Alcohol Marketing and Sponsorship in 2014. The higher rates of exposure to alcohol marketing for Māori children demonstrate the government is not meeting its obligations to Māori under the Treaty of Waitangi, particularly as Māori are 1.5 times more likely to be hazardous drinkers than non-Māori. This research provides further evidence of the need for legislative restrictions on alcohol marketing, specifically, ending industry self-regulation of alcohol marketing, banning alcohol sponsorship of sport, and increasing restrictions on alcohol outlet shopfronts.

Introducing alcohol marketing restrictions…would substantially…protect children from the adverse effects of early onset alcohol consumption.

Introducing alcohol marketing restrictions similar to those introduced in France, as recommending by the Law Commission, would substantially reduce children’s exposure to alcohol marketing and protect children from the adverse effects of early onset alcohol consumption. However, persistent alcohol industry lobbying has successfully weakened important aspects of the French Évin Law, such as permitting televised and outdoor alcohol marketing, highlighting the need for continuous advocacy and public support even when robust legislation is introduced.

Featured image credit: People cheering at a party by Yutacar. Public domain via Unsplash.

The post Anywhere, anytime: children’s exposure to alcohol marketing appeared first on OUPblog.

What is the role of a doctor in 2018?

In a tumultuous world in which technology is expanding faster than at any other point in history, where many countries face a myriad of conflicts and natural disasters, and where patient needs are continually changing, it was only fitting that the question we posed to entrants of this year’s Clinical Placement Competition should be “what is the role of a doctor in 2018?”. In partnership with Projects Abroad, we asked medical students to answer this question using a picture and a caption, for the chance to win £2,000 towards a clinical placement abroad.

We received a number of insightful and thought-provoking entries, but after careful deliberation, we are delighted to announce that the winner of the Clinical Placement Competition 2018 is Binay Gurung. Binay’s picture portrays an honest and authentic snapshot of medicine around the world, which complemented his definition of the role of a doctor in 2018. We asked Binay to tell us more about the inspiration behind his entry, and about his time in the Nepalese hospital featured in his picture.

It was a hot summer day and there were seven of us in the room – a doctor, an auxiliary nurse, a 16-year-old girl (we will call her Rita) and her mother, two other patients waiting to be seen, and me. Rita had been suffering with stomach pain for a few weeks. The doctor, a recent graduate, took a brief history from Rita and asked her to lie on the couch. When he finished examining her abdomen, he said, “Now take off your underwear, lie on your left and bring your knees to your chin.” He wanted to complete the examination with a digital rectal examination. Rita flushed, hesitated for a moment, but complied obediently.

This was in a village hospital in Rukum, a remote district in Nepal around 300 km west of Kathmandu, where I had gone for an elective placement. Rita was one of at least fifty patients waiting to be seen that morning, most of whom had walked for one and a half to two days to get there. Among the crowd of people waiting that morning were a malnourished 7-year-old girl who turned out to be HIV positive; an unconscious 22-year-old mother of two rushed in from a village, eight hours away, with wild mushroom poisoning; a middle-aged man with a black gangrenous arm due to a recent fracture that hadn’t been treated; the list goes on. I was surprised that most of the patients only came to the hospital as a last resort, often too late from a clinical point of view, but that wasn’t the main problem they faced there. At least, these people came and were lucky to be receiving some medical care. Many people either did not make it to the hospital in time (around 250 had died in this way the year before), or could not afford the treatment so did not bother coming to the hospital, or went to witch doctors instead for treatment.

Image credit: Binay’s winning photograph, captioned: ”A doctor’s role in 2018 should be to promote global health equity and equality. A hospital ward in Rukum, Nepal: People walk for over 2 days to come to this hospital, the closest healthcare facility in their region.” (Photo credit: Binay Gurung. Used with permission)

Image credit: Binay’s winning photograph, captioned: ”A doctor’s role in 2018 should be to promote global health equity and equality. A hospital ward in Rukum, Nepal: People walk for over 2 days to come to this hospital, the closest healthcare facility in their region.” (Photo credit: Binay Gurung. Used with permission)The hospital was run by a non-government Christian organisation in partnership with the local government. Built on 2000 square meters of land donated by 16 local farmers, it served a large hilly area. I was told that the hospital had a capacity of 50 in-patients, but later realised this calculation was not based on bed space alone, but on bed space plus floor space. The hospital employed 41 people, but only two doctors, nine nurses, and five medical assistants. The hospital heavily relied on medical volunteers from developed countries, so much so that all the 196 major operations performed the year before were by volunteer surgeons. Even with such limited resources, the hospital was doing a commendable work. Apart from running a busy out-patients clinic and a 24-hour emergency service, it organised free medical camps for people living in the very remote regions – 4,500 people had benefited from this service the year before. Additionally, the hospital regularly ran a public health programme of education and vaccination for the people in the region, most of whom are illiterate.

What I describe here is not unique to Rukum. According to a report by the World Health Organisation, at least 400 million people, mostly in low- and middle-income countries, currently lack access to essential healthcare. The situation is worse if we consider surgical care. The Lancet Commission on Global Surgery reported that out of the 313 million surgical procedures undertaken worldwide every year, only 6% occur in the poorest countries. The numbers speak for themselves. Access to healthcare is not the same everywhere and, alarmingly, people in the poorest regions, where over a third of the world’s population live, are the most affected.

Image credit: “The hospital laboratory, which performs basic blood tests”. (Photo credit: Binay Gurung. Used with permission)em>

Image credit: “The hospital laboratory, which performs basic blood tests”. (Photo credit: Binay Gurung. Used with permission)em>But why should we care? We should care because it is inhumane not to. And if not for humanity’s sake, it is important that we do something about this for our own selfish reasons. As Dr Margaret Chan, the World Health Organisation’s former director-general, said in her Chatham House speech in 2011, we are so interdependent in this world that the consequences of an adverse event in one part can directly affect people in the opposite corner of the world. This was demonstrated with severe consequences by the 2008 financial crisis and equally by the recent Ebola outbreak in 2014.

It is about time we do something about such injustice in healthcare, and who better to carry this responsibility than doctors, the group of professionals who have taken a solemn pledge to dedicate their lives to the service of humanity? We should redefine a doctor’s role, in 2018 and the years to come, to include advocating for the promotion of global health equity and equality.

Featured image credit: ‘Nepal in the world (W3)’ by TUBS. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post What is the role of a doctor in 2018? appeared first on OUPblog.

The politics of food [podcast]

Gearing up for Thanksgiving and the holiday season brings excitement for decorations and holiday cheer, but it can also bring on a financial burden – especially where food is concerned. The expectation to host a perfect holiday gathering complete with a turkey and trimmings can cause unnecessary pressure on those who step up to host family and friends.

On this episode of The Oxford Comment, we explore the social, economic and psychological issues that families face, when providing meals year-round, especially during the holidays. From parent-shaming to the expense of eating organic, the food we eat says more than meets the eye. With the help of the authors of Pressure Cooker: Why Home Cooking Won’t Solve Our Problems and What we Can Do About It we tackle the million dollar question; how do families approach the conversation of food?

Featured image credit: Farmhouse tableware by Hannah Busing. Public Domain via Unsplash .

The post The politics of food [podcast] appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers