Oxford University Press's Blog, page 214

November 18, 2018

Dynasties: emperor of all penguins

Of the seventeen species of penguin in existence, the emperor penguin is arguably the most well-known and heavily documented. Depicted in films such as March of the Penguins and Happy Feet, it is difficult not to be endeared by the flightless birds and their fluffy chicks, so it is no surprise that they have been documented once more in BBC’s Dynasties.

In the second post of our Dynasties blog series, we’ll be exploring how emperor penguins and their flippered relatives interact with each other to build their respective dynasties in the chilly Antarctic.

Who’s the tallest of them all?Standing over a metre tall, the emperor penguin is the tallest penguin of all the species alive today. However, it is not the tallest penguin there has ever been on this planet. Over the years, several fossilised ancestors of penguins have been identified, the oldest of which is around 60 million years old. A recent study suggested that this penguin ancestor would have been 5 foot, 7 inches tall – taller than the average human woman!Frosty incubators

Like most members of the animal kingdom, penguins breed during the spring and summer – except emperor penguins. Instead, emperors brave the bitter winters of the Antarctic to lay their eggs, incubating until they hatch in the spring, and raise their chicks in the summer. Through this method, the penguins avoid exposing their chicks to the frosty climate as much as possible, allowing them to mature before the next winter hits.

Image credit: Penguin chick by MemoryCatcher. CC0 via Pixabay.Chick-rearing vs. hunting

Image credit: Penguin chick by MemoryCatcher. CC0 via Pixabay.Chick-rearing vs. huntingThe closest relatives to emperor penguins are the king penguins, who look very similar as adults but whose chicks are significantly different in appearance. King penguins vary in hunting behaviour at different stages of the chick-rearing cycle depending on their age and breeding experience. For example, during the incubation stage, younger breeders take longer hunting trips, while more experienced breeding penguins take shorter foraging trips during the early stages of the chick’s life. Furthermore, females have been found to spend less time hunting than males.Krill or be krilled

Antarctic penguins, including the Emperor penguin, are dependent on krill for food. In particular, young penguins – who are constantly growing until they become an adult – rely on krill to survive; if the number of krill is particularly low at any point, juvenile mortality increases. Penguins compete for krill against other predators, including leopard seals, who also hunt penguins! Many seabirds, including penguins, have also been known to ingest plastic debris, which can lead to obstruction of the gut and poisoning through the toxic chemicals found in plastic, eventually leading to death. This issue was explored in the memorable episode of Blue Planet II narrated by Sir David Attenborough, and our accompanying blog post: ‘Our Blue Planet’.

Image credit: Emperor penguin diving by WikiImages. CC0 via Pixabay.Hunt and be hunted

Image credit: Emperor penguin diving by WikiImages. CC0 via Pixabay.Hunt and be huntedAs penguins are in the middle of the food chain – hunters of krill but hunted by seals – diving into the sea is risky but necessary for all species of penguin in the Antarctic. Adelie penguins have developed a behaviour which favours the many: the colony observes their fellow penguins before deciding whether to dive in or not, waiting for the bravest/hungriest penguin to take the plunge. The colony will then only follow the first penguin into the water if the water is proven safe, i.e. they aren’t attacked by a seal upon entering the ocean. Although this strategy is unfair on the bravest penguin, which has a good chance of dying when they hit the water, it does prevent a massacre of the colony should there be any seals waiting in the water.Equal partnerships

The chick-rearing habits of emperor penguins are widely known: the female will lay the egg to be incubated by the male, while the female travels to the ocean to hunt; when she returns a couple of months later, the females regurgitate the fish they ate to feed their new-born chick, while the males take their turn to go hunting in the ocean; the pair will then continue to switch between hunting and chick-rearing for the early months of their offspring’s life. In contrast to this equal partnership, in over 70% of cases little penguins choose to exercise unequal parenting effort, despite the fact that being an equal pair is a more effective strategy, suggesting quality of character plays a role in how dedicated little penguins are as parents.Love isn’t black and white

Did you know that penguins were the first species observed to have same-sex pairings? Between 1915 and 1930, Edinburgh Zoo kept a group of penguins, which were named according to their assumed male/female pairings. However, after several years and various observations, the zoo realised that they had got many of the penguins’ genders wrong, finding male and female same-sex couples to be present in addition to the heterosexual couples! Since then, many homosexual pairs have been observed in nature and in zoos, including at Central Park Zoo in New York, who famously hatched and raised an orphaned chick and have since been the subject of children’s picture book And Tango Makes Three .

Featured image credit: Emperor penguins by Christopher Michel. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Dynasties: emperor of all penguins appeared first on OUPblog.

Graffiti Artists are Gaining Recognition—and Rights

Graffiti used to be thought of primarily as vandalism—as a furtive, illegal activity that defaced public property. It was seen as both a reflection of and contributor to urban decay.

However, several recent high-profile lawsuits involving what is now called “exterior aerosol art” reveal just how far graffiti has advanced in cultural esteem and recognition as a legitimate art form. While some corporations are using aerosol art’s newfound popularity turn a profit, aerosol artists are pushing back and asserting their authorial rights in court.

For example, earlier this year H&M attempted to use a piece of graffiti art on a Brooklyn handball court as the backdrop for an ad. The work had been put there illegally. When the artist objected, H&M asked a court to declare that illegal graffiti art is not entitled to copyright protection. In the face of a swift social-media-fueled backlash against the clothing chain for appearing disrespectful to street artists, it dropped the suit and apologized.

In another case, this time involving legally made aerosol art, a Swiss artist who goes by the name Smash 137 is suing General Motors for including one of his commissioned murals in a Cadillac commercial set in a Detroit parking garage. The artist claims that GM violated his copyright by using images of the mural without his knowledge or consent.

One of the most noteworthy lawsuits involving graffiti art is the recent decision (currently under appeal) in the 5 Pointz case. In November 2017, 21 aerosol artists were awarded $6.75 million by a federal judge in a landmark lawsuit against the developer of the 5 Pointz factory complex in Long Island City, in Queens. In the 1990s, the developer, Jerry Wolkoff, began allowing aerosol artists to use the sprawling complex to develop and display their work. He even employed a curator to manage the site, with the mutual understanding that eventually all of the work would be destroyed. 5 Pointz, which is visible from the New York City Subway’s 7 line, began to attract attention from aerosol artists around the world as well as tourists. The site was featured in a TV show, a movie, and in multiple music videos. Ironically, its success as a “graffiti mecca” may have helped to hasten its demise by increasing the value of the property.

“Moral rights laws are generally understood to protect the reputational interests of visual artists.”

In 2011, Wolkoff announced that he planned to demolish the factory buildings in order to build two apartment towers. The artists objected. Citing the Visual Artists’ Rights Act (VARA), a federal statute which protects works of art with “recognized stature” from destruction, they sought an injunction in court against the destruction of their murals. Wolkoff falsely claimed that he needed to begin development of the complex right away, lest he lose certain tax benefits, and the judge denied the injunction in late 2013. As it turned out, Wolkoff had not even applied for the permits he needed to develop 5 Pointz. He used the opportunity to whitewash all of the 5 Pointz murals in the middle of the night, without warning the artists. A jury subsequently found that 45 out of 49 of the works were of “recognized stature” and awarded $150,000 in damages for each work, for a total of $6.75 million.

While some worry that the outcome will have a chilling effect on opportunities for exterior aerosol artists to receive permission from property-owners to develop their work, the ruling is significant for several reasons. It was the first time that VARA had been applied in a case involving graffiti art, and it thereby affirms its status as a legitimate art form.

Second, it highlights the delicate balancing act between the rights of property owners and artists that judges must undertake when applying this law to works of art permanently affixed to walls. It is one thing for the law to enjoin the owner of an oil painting of recognized stature against destroying it: this seems like a relatively minor restriction of a property owner’s rights. But when the protected artwork is part of a building, one potential implication of VARA is that the building owner could be forced to preserve the artwork for the life of the artist. This issue arose in a similar case in 2016, in which the artist Katherine Craig sued a property owner who wanted to convert the 9-story building on which she had painted her Illuminated Mural into condos. The case was settled before it went to court.

While VARA comes under the umbrella of US copyright law, the statute protects the so-called “moral rights” of artists, which are their non-economic or reputational rights in their artworks. This enables a visual artist to her artwork but still maintain certain rights with respect to it, because that artwork serves as a representative of her name brand as an artist. If the work is distorted, it may harm the reputation of the artist whose name is attached to the work. (VARA protects all works of visual art, whether they have recognized stature or not, from modification or misattribution). But unlike traditional forms of visual art, aerosol art on building walls cannot easily be bought or sold, and they are usually understood to be ephemeral by their very nature. In one sense, this makes exterior aerosol art an uncomfortable fit for the paradigmatic VARA cases presumably intended by Congress when it passed the statute nearly thirty years ago. On the other hand, however, it highlights the interest that the 5 Pointz artists had in the preservation of their works: they could not sell them, but their ongoing presence could lead to future commissions and professional opportunities. In that sense, moral rights, despite their designation as non-economic rights, can have very real material consequences for artists. Reputation is a form of wealth.

Moral rights laws are generally understood to protect the reputational interests of visual artists. But they also protect the interests of the public, which can regard cherished works of art as its own, as part of a cultural patrimony. This is why works of recognized stature are protected from destruction under VARA—although it has been left to the courts to decide just which artworks cross that threshold. The notion that a work of graffiti could become so valuable to the public that its removal would spark public outcry might seem farfetched, but this has happened on multiple occasions when enterprising property owners have attempted to sell works by Banksy that he illegally sprayed on their walls. When residents of a community protest the removal of graffiti art, rather than its presence, it is a sure sign that exterior aerosol art has entered a new era.

Featured image credit: Lost in Keong Saik by Autumn Studio. Public Domain via Unsplash

The post Graffiti Artists are Gaining Recognition—and Rights appeared first on OUPblog.

November 17, 2018

Big money, dark money, and the two Gilded Ages

The 2018 midterm elections were the most expensive in history, and much of the money that financed them was undisclosed, or “dark.” There has always been big money in elections, of course, and some of it has always been dark. In the first Gilded Age, all campaign contributions were made in secret. The presence of big and dark money in today’s elections, however, is not a continuation of old practices; it came about as a result of recent court decisions.

Congress tried to curb big money at the tail end of the Gilded Age: it banned corporate money from elections in 1907 and brought campaign money into the light by passing the first disclosure law in 1910. Big donors and politicians opposed the reforms but complied with them once they passed.

Presidential campaign committees began filing disclosure reports in 1912, and have been doing so ever since. Those reports reveal that disclosure caused another change: big donors immediately began writing much smaller checks. It is likely that some checks were still illegally laundered corporate contributions, but at least they were smaller. Apparently, billionaires and corporations both thought it was not a good idea to flaunt their wealth in public.

The one percenters of the first Gilded Age might not have liked the new law, but they raised no ideological or constitutional objections. They adapted, grudgingly, to the new norms of a more open democracy. And big donors continued to write smaller checks into the 1960s — an impressive record for a law with no formal enforcement mechanism.

But in 1968, twenty of Richard Nixon’s fundraising committees failed to file disclosure reports, and Nixon’s Justice Department didn’t prosecute them. In 1972, President Nixon solicited illegal corporate contributions and failed to report dozens of individual gifts that were the largest in half a century. These were the first large-scale violations of the disclosure law.

The resulting Watergate scandal spurred Congress to pass more comprehensive reforms. This time, though, they did meet with ideological and constitutional objections. Conservatives could not defeat the reforms in Congress, but in 1976, they challenged them before a Supreme Court that had taken a right turn under Nixon.

They based their challenge on a radical theory of the First Amendment: that political money is tantamount to political speech and has the same constitutional protection. They did not oppose disclosure, but they did oppose limits on contributions and expenditures.

The justices accepted the conservatives’ First Amendment theory, but still upheld limits on contributions to candidates and PACs. Contributions were only second-hand speech, they said, and so had less constitutional protection. But they struck down spending limits because spending was “pure speech” and had full constitutional protection. That included third-party spending on behalf of candidates — called independent expenditures because they are supposedly done without the candidates’ cooperation. This was the key victory in what the challengers triumphantly called the “wreckage” of the post-Watergate reforms.

It is through independent expenditures that contributions are getting bigger and darker today. That is because in 2010, the Court adopted an even more radical First Amendment theory. In Citizens United, it went against the 1907 law to hold that corporations have the same right as individuals to make independent expenditures.

It is through independent expenditures that contributions are getting bigger and darker today. That is because in 2010, the Court adopted an even more radical First Amendment theory.

Fortune 500 companies did not make such expenditures for fear of offending customers. But nonprofit corporations registered with the IRS as nonpolitical social welfare groups jumped at the chance. IRS rules let them make political expenditures as long as they spend most of their money on their nonpolitical goals. But there are ways around those rules, ways the IRS seems unable to block. And as non-political groups, they do not have to report the donors who finance their political spending. The IRS was immediately inundated with applications to form more such groups.

Just weeks after Citizens United, the District of Columbia circuit court struck down the limit on contributions made to independent-expenditure PACs — a law that had been in force for thirty-four years. This decision created the super PAC, which can take contributions of unlimited size to make unlimited independent expenditures.

But super PACs have to file disclosure reports. That was all right for the billionaires who now think it is a good idea to flaunt their wealth in public. And publicity-shy billionaires stayed in the dark by laundering their contributions to super PACs through the politically active social welfare groups unleashed by Citizens United.

The first Gilded Age was a time of great inequality and disruptive social and economic change. But it was also the beginning of the urban industrial economy, with labor unions and other countervailing forces, that was the foundation for twentieth-century democracy.

Now that old economy is crumbling. So is the old democracy and the campaign finance laws that were an essential part of it. Recently that crumbling has been accelerated as a matter of political policy. Dark money and super PACs are the results of the Supreme Court’s deliberate dismantling of campaign finance law. Today’s one-percenters are adapting to the norms of a democracy that is less open and more money-driven than at any time since the first Gilded Age.

Featured image credit: Packs Pile Money by PublicDomainPictures. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Big money, dark money, and the two Gilded Ages appeared first on OUPblog.

Why is it so difficult to throw away fetuses?

It has been five years since I started my research on anatomy in 19th century Belgium, but I remember my first visit to an anatomical collection like it was yesterday. It was the beginning of autumn and the temperature was cool enough to cause a slight numbness in my hands. I was not yet used to the piercing smell of alcohol and formaldehyde; a smell that soaked into my clothes and skin, and that I immediately associated with death. Most of all I remember the fetuses. Dozens of jars of human fetuses packed four or five deep on plain metal shelves. As I rearranged them carefully to be able to look at them, they rocked on the rippling preservation fluid. Of course, there were other items on the shelves —a jar with ovaries, a preserved heart, all kinds of bones— but they were less numerous, and their containers and preservation fluid suggested that they stemmed from the 20th rather than the 19th century.

Image taken by and used with permission of the author.

Image taken by and used with permission of the author.Naive as I was —a newly-come PhD student in the beginning of her twenties— I figured that 19th-century anatomists must have been particularly interested in fetuses. I even found some evidence to support this claim: Cambridge archeologists had argued that fetal and infant remains were much more likely to be curated long term in anatomical collections; meeting reports of 19th century scientific societies showed that anatomists encouraged their former students to send “interesting” miscarried or stillborn fetuses to them; and snippets from hospital archives revealed that many women who died in hospital were autopsied in the hopes of finding fetal remains.

But then I found the original 19th-century inventories of the anatomical collections I visited. There were indeed long enumerations of fetal preparations. Yet to my surprise there were also mountains of pages on other body parts and types of bodies, such as preparations of the sensory organs and the respiratory system, and a large collection of skeletal remains from different “races”. It became clear that anatomists in 19th century Belgium had not been particularly interested in fetuses. The development of the fetus was but one of their many interests. It just happened to be that the jars containing fetuses remained in collections until today, whereas the other preparations had disappeared. To give one concrete example: it is estimated that the anatomist Adolphe Burggraeve (1806-1902) and his aide Edouard Meulewaeter made over 200 preparations per year. Only three remain today. The most well-known is a newborn child dressed in a white christening gown, lauded for its rosy cheeks and natural skin tone.

If these fetuses do not tell us much about 19th-century scientific interests, then what can we, as historians, learn from them? Most obviously, it has taught me to distinguish between historical collections and what is left of them today. Remaining specimens are not representative of the collections to which they once belonged. Historians of anatomy have to broaden their view, and scrutinize what archeologists have called the “missing majority”. In fact, studying missing anatomical specimens, and the ways in which they have been disposed of, cannot only reveal much about changing research agendas, but also about changing standards and sensitivities with regard to the preservation and use of human remains in collections.

Most importantly, the preservation of these fetuses tells us something about historically rooted assumptions about the social value of certain human remains.

Most importantly, the preservation of these fetuses tells us something about historically rooted assumptions about the social value of certain human remains. Scholars such as Susan Lawrence or Lynn Morgan have drawn attention to the varying social value of different parts or types of bodies. Whereas we believe that human remains clearly embodying a sense of identity or personhood should be either kept or disposed of in meaningful ways, we are largely indifferent towards the treatment of other bodily materials, such as tissue samples, hair, or vials of blood. In a similar vein, differences between historical anatomical collections and what is left from them today might teach us much about relations between body and personhood, and about what it means to be (dis)qualified as human.

In the Brussels City Archives, I found requests to bury “jars with organs”. At least until the 1940s, discarded anatomical preparations were brought to the cemetery, where they were buried anonymously, together in a grave. It explains why I was unable to trace most of the preparations that filled the pages of 19th-century inventories. However, I also discovered that anatomists had to ask the city council for special permission to preserve fetuses after six months of gestation. The law described that they had to be buried individually in a separate coffin or alongside their mother if she had died during childbirth. Whereas “jars with organs” could be buried anonymously, fetuses had to be “decently” disposed of because they had a different social value. Perhaps fetuses remain in collections because we were —and are— unable to throw them away.

Featured image credit: Science & Technology Fair 2011 – Kolkata 2011-02-09 0844 by Biswarup Ganguly. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Why is it so difficult to throw away fetuses? appeared first on OUPblog.

November 16, 2018

George Balanchine: mythology and reality

There are few choreographers with more influence in the world of ballet than George Balanchine. Over three decades after his death, his ballets are performed somewhere on the planet virtually every day. Two prominent dance institutions continue his legacy—the School of American Ballet and the New York City Ballet—and dancers who worked alongside him lead important companies and schools across America from Miami to Seattle. So important is Balanchine’s legacy that his own last name is a registered trademark, and a special Trust ensures that his ballets are preserved and licensed properly. This kind of permanence is especially notable in the world of dance, often an ephemeral and evanescent art form.

As is the case with many famous artists, Balanchine is a figure somewhat larger than life, and accordingly, his life and career have been the subject of a good deal of mythologizing. These ways of talking about Balanchine make for great storytelling, and many of them have their origins with Balanchine himself. But they don’t actually square with reality. In the course of my research for Balanchine and Kirstein’s American Enterprise, I discovered time and again that the reality of what happened during Balanchine’s first decade in the United States is infinitely more fascinating and illuminating than the stories and myths. Here are five of the most consequential of these myths:

1) “But first, a school.” This might be termed the founding myth of Balanchine’s American career, and the choreographer is said to have uttered this phrase when Lincoln Kirstein first proposed that he come to the United States to found a ballet company in 1933. In fact, most evidence suggests that Kirstein was the true champion of the School of American Ballet, while Balanchine’s primary motivation for coming to America was the opportunity to create new ballets for the stage. Choreography and not pedagogy remained Balanchine’s primary focus for most of his early years in the United States, much to the consternation of Kirstein and others.

Image credit: Portrait of Ringling Circus choreographer George Balanchine: Sarasota, Florida, April 1942. Joseph Janney Steinmetz Collection, State Library and Archives of Florida. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: Portrait of Ringling Circus choreographer George Balanchine: Sarasota, Florida, April 1942. Joseph Janney Steinmetz Collection, State Library and Archives of Florida. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.2) Balanchine’s “first ballet in America.” In stories of Balanchine’s early years in America, one work holds special status, in part because it is the only ballet from these early years to have survived into the present. This is Serenade, one of Balanchine’s most beloved and iconic works, and the first wholly original work begun after his emigration. In contrast to its revered status today, however, Serenade was one of Balanchine’s least significant works during these early years. Like its creator, Serenade had not yet achieved the renown that it enjoys today.

3) Balanchine versus the New York Times. It’s often claimed that John Martin, the prominent dance critic of the New York Times, had it in for Balanchine and made it difficult for his enterprise with Kirstein to succeed. Martin is caricatured as an obstinate partisan with an irrational allegiance to modern dance and special disdain for foreign-born artists. In fact, Martin was a big fan of many of Balanchine’s works and the faults that he did find in some of his ballets were echoed by numerous other writers and observers.

4) Balanchine the “neoclassical” choreographer. Balanchine is especially renowned today for his abstract and neoclassical approach to choreography, exemplified by works such as Serenade and Concerto Barocco. When he first arrived in America, however, Balanchine had a much different style and was mostly regarded as an overly experimental modernist with a penchant for the idiosyncratic and bizarre. Most of his ballets were premised on obsessive love triangles, surrealist conceits, or both, and American audiences and critics accordingly found them a bit hard to swallow, including his now beloved ballet Apollo.

5) The meaning of Balanchine’s “popular” work. During his first decade in America, Balanchine created dances for nine productions on Broadway (including four musicals by Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart) and three feature-length films. These projects are often considered peripheral to Balanchine’s efforts with Kirstein, even though many dancers and historians have long noted how his choreographic style was influenced by rhythms and techniques from popular American dance forms such as tap. In reality, Balanchine’s popular projects were closely intertwined with his “official” work on the ballet stage. And one of his most significant neoclassical ballets, Concerto Barocco, was likely inspired by the title number of the musical On Your Toes.

In recent months, the two institutions that Balanchine co-founded with impresario Lincoln Kirstein have been unsettled by abrupt changes in leadership and disturbing allegations of misconduct. In discussions about the future direction of the enterprise, Balanchine’s legacy looms large, to the point of defining and perhaps hindering the search for a new leader. At this moment in history, it’s thus more important than ever to separate mythology from reality as far as Balanchine is concerned. Indeed, confronting the reality of Balanchine’s complicated past just might make it easier for the School of American Ballet and New York City Ballet to chart a bolder and more confident future.

Featured image credit: German dancer Falco Kapuste in Apollon Musagète, 1978. E. Straub. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons .

The post George Balanchine: mythology and reality appeared first on OUPblog.

Time for new targets to treat blocked arteries

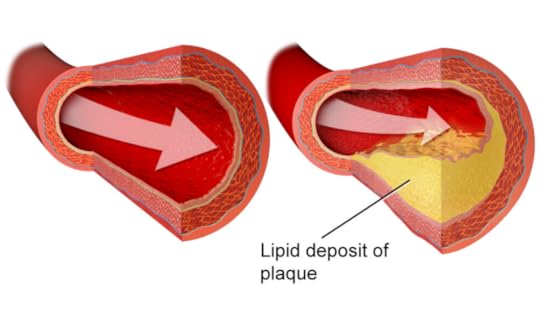

The human cardiovascular system relies on continuous circulation to ensure it functions to meet the needs of the body. Like a fish must remain in water, body organs and tissues require a constant supply of blood. A loss of blood flow, dependent on severity and duration, can result in a loss of oxygen, build-up of waste products and tissue damage.

Atherosclerosis is the most common cause of reduced blood flow, which is characterised by a build-up of fat within the blood vessel known as a plaque. As the plaque increases in size the vessels become narrower and stiffer, causing a reduction in blood flow, which can cause angina or peripheral artery disease. At an advanced stage, the plaque can rupture causing blood clots to form and occlude vessels. In the heart, this can cause a heart attack or in the brain, can cause a stroke.

We often think of the body’s immune system as our frontline of defence against the outside world; however, the cells of the immune system also fulfil housekeeping roles inside the body such as removing dead cells and waste. In the past, researchers thought that atherosclerotic plaques were a passive collection of fat from the bloodstream that increased over time. Researchers now understand that atherosclerosis is actually an inflammatory disease where immune cells are centrally involved in disease progression. During atherosclerosis, the blood vessel is “activated” and produces markers that recruit a diverse population of immune cells. The immune cells produce their own markers that interact with the activated cells in the vessel and with fat molecules to drive plaque development.

The markers present on the immune cells in the atherosclerotic plaque are interesting to researchers for two reasons. Firstly, they are present in a unique pattern that allows identification of the type of cell it is. Secondly, they mark a location where a drug or treatment can act to potentially slow, stop or prevent atherosclerosis by acting to stop the function of the cell to which it is attached. The ability to study these markers, therefore, would allow researchers to identify unique cells so that they can target them for the development of new therapies.

Photo by Blausen.com staff, courtesy of Oregon State University, via Flickr

Photo by Blausen.com staff, courtesy of Oregon State University, via FlickrScientists can identify cell markers by tagging them with a molecular sensor such as fluorescent light or dye. Techniques that use this technology are currently the go-to method for identifying immune cells. Unfortunately, these methods are limited in that they can only tag up to a maximum of 18 markers at a time. This means that researchers cannot study the full diversity of the immune cell population. Recently, researchers have introduced the use of Cytometry by Time of Flight (CyTOF) which uses heavy metals to tag cells. Crucially, the new technique allows for the tagging of 45 cell markers simultaneously.

The technique has now been used by researchers to study the immune cells in atherosclerotic vessels in a pre-clinical model. Researchers showed that vessels from mice with atherosclerosis contained the same type of immune cells as non-atherosclerotic vessels but expressed them in different proportions. It would not have been possible for researchers to measure the different levels of these immune cells using the previously existing methods. Now that this new technique has been optimised, the next step is to use human samples to identify what immune cells could be targeted for new therapies in atherosclerosis.

Feature Image Credit: “Blood cells” by quimono. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Time for new targets to treat blocked arteries appeared first on OUPblog.

Place of the Year 2018 nominee spotlight: Myanmar

Extreme violence and discrimination has led to a humanitarian crisis in Myanmar’s Rakhine State. Throughout 2017 and 2018, Rohingya refugees have been crossing the border into Bangladesh in fear of their lives. United Nations officials have described the crisis as “a textbook example of ethnic cleansing.” In 2018, mid-October reports revealed that the number of Rohingya refugees has reached nearly one million. In addition to being forced from their homes, many refugees face further danger; young girls in Bangladesh refugee camps account for the largest group of trafficking victims, with many being sold into forced labor.

Human rights groups blame anti-Rohingya propaganda and “fake news” on Facebook for inciting murders, rapes, and the largest forced human migration in recent history. Myanmar military personnel conducted a systemic campaign through false Facebook accounts and posts, targeting the country’s predominantly Muslim Rohingya minority group. The posts consisted of personnel posing as pop stars and national heroes, posting and sharing fictitious stories claiming Islam was a global threat to Buddhism, the rape of a Buddhist woman by a Muslim man, and more.

The fake news campaign stretches back half a decade, with as many as 700 officers meeting in foothills near the capital of Naypyidaw. They would gather intelligence on popular accounts and criticize any content that was unfavorable to the military.

Facebook’s head of cyber-security policy, Nathaniel Gleicher, said it had found “clear and deliberate attempts to covertly spread propaganda that were directly linked to the Myanmar military.” The Facebook posts have since been removed, with Mark Zuckerberg saying in response to the deaths that, “My emotion is feeling a deep sense of responsibility to try to fix the problem.”

The concept of fake news has created acute damage to the cultures of democracy and faith in institutions in places such as Hungary, Italy, Brazil, Mexico, and the 2018 Midterm elections in the US. The negative repercussions of fake news are tragically present in Myanmar today. On the below episode of the Oxford Comment, authors Jamie Susskind and Siva Vaidhyanathan explore the influence of digital media on the modern political sphere and the negative repercussions that come with it, such as in Myanmar. Find all of the Oxford Comment episodes also on Spotify.

On November 15, 720,000 Rohingya who escaped slaughter, rape, and village burning were scheduled to be repatriated to Myanmar from Bangladesh. Among others, the United Nations was vehemently opposed to this move, warning that forcing the first group of 2,200 Rohingya refugees to return to the mass violence that awaits the minority Muslim group is a “clear violation” of core international legal principles. A coalition of 42 humanitarian and civil society groups called this repatriation process “dangerous and premature.” The day the refugees were supposed to be transported back to Myanmar, Bangladesh’s Rohingya Relief and Repatriation Commissioner announced that no one will be forcibly repatriated. Many of the refugees are terrified at the prospect of returning, as they believe it would be a death sentence.

On the global stage, human rights advocates are condemning the actions of political leaders in Myanmar. In March, the US Holocaust Memorial Museum rescinded its top award from Suu Kyi. Other honors she has been stripped of include the freedom of the cities of Dublin and Oxford, England. In September, Canada’s parliament voted to strip Suu Kyi of her honorary citizenship. On November 12, Amnesty International stripped State Counsellor of Myanmar Aung San Suu Kyi of the Ambassador of Conscience Award. By failing to speak out against the violence against the Rohingya Muslim minority, the human rights group accused the leader of perpetuating human rights abuses. Amnesty’s Secretary General Kumi Naidoo wrote that, “We are profoundly dismayed that you no longer represent a symbol of hope, courage, and the undying defense of human rights.” The United Nations has been outspoken in their condemnation of the military leaders in Myanmar, recommending that they be put on trial for crimes that include genocide.

GIF by Nicole Piendel for Oxford University Press.

GIF by Nicole Piendel for Oxford University Press.Learn more about the history of Myanmar and the Rohingyas with these titles: The Rohingyas, Burma/Myanmar: What Everyone Needs to Know, Southeast Asia: A Very Short Introduction, Borders: A Very Short Introduction, Migrant, Refugee, Smuggler, Savior

Place of the Year 2018 Shortlist

Featured image credit: “myanmar-burma-landscape-sunrise” by 12019 / 10266 Images. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Place of the Year 2018 nominee spotlight: Myanmar appeared first on OUPblog.

November 15, 2018

Twelve philosophy books everyone should read: from Plato to Foucault [slideshow]

Every year the third Thursday in November marks World Philosophy Day, UNESCO’s collaborative “initiative towards building inclusive societies, tolerance and peace.” To celebrate, we’ve curated a reading list of historical texts by great philosophers that shaped the modern world and who had important things to say about the issues that we wrestle with today such as freedom, authority, equality, sexuality, and the meaning of life.

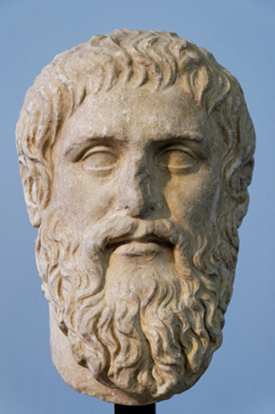

The Republic by Plato (427-347 B.C.E.)

The Republic by Plato (427-347 B.C.E.) Plato’s greatest work was the Republic, an extended dialogue on justice, in which he outlined his view of the ideal state. It is decidedly authoritarian. He begins from the premise that only those who know what good is are fit to rule, and he prescribes a long and rigorous period of intellectual training which he thinks will yield this knowledge. They should also govern with a view to maximizing the happiness of the state as a whole.

Leviathan by Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679)

Leviathan by Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679) Hobbes was one of the founders of modern political philosophy. He wrote that citizens had to transfer some of their freedom in exchange for protection and security from the sovereign authority. In this way, they have entered into a kind of social contract. Without government, people would find themselves in conflicts.

Treatise of Government by John Locke (1632-1704)

Treatise of Government by John Locke (1632-1704) Locke helped to establish the first fully formed, secular theory of human rights with his work, Treatise of Government (1690). He started with the idea that in a state of nature, free from external authority, people had a duty to protect themselves and not to do harm to others. He contended that when society is formed, a government is set up to determine the disputes between people if these rights and duties are not obeyed and respected. Locke saw civil government as the means to enforce laws and to settle disputes as long as they didn’t infringe the trust placed in them by citizens. Since the government exists by the consent of the people to promote the good for its citizens, any government that failed to do so should be removed.

A Treatise of Human Nature by David Hume (1711–76)

A Treatise of Human Nature by David Hume (1711–76) Widely known for his humanitarianism and philosophical scepticism, Hume’s philosophy was a form of empiricism. He rejected speculative philosophy and theology and all claims to truth that lay outside human experience. The basis for knowledge, he argued, lay only in the experience of the senses. Hume’s most enduring work is A Treatise of Human Nature in which he advocates the scientific study of human nature as a means of understanding and improving society. Such study, Hume argued, would provide the basis for a secular morality and for a society ruled by justice and reason.

The Social Contract by Rousseau (1712-1778)

The Social Contract by Rousseau (1712-1778) Born in Geneva in 1712, Jean-Jacques Rousseau was a visionary and revolutionary philosopher and writer. He opens The Social Contract with the dramatic opening line ‘Man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains’. Rousseau asserts that the authority of the state can only be legitimate if it comes from the will of the people. The book’s ideas exert a considerable influence on the French Revolution and on the development of modern principles of human rights.

The Wealth of Nations by Adam Smith (1723 -1790)

The Wealth of Nations by Adam Smith (1723 -1790) Smith was an eminent Scottish moral philosopher and the founder of modern economics, best-known for his book The Wealth of Nations (1776) which was highly influential in the development of Western capitalism. In it, he outlined the theory of the division of labour and proposed the theory of laissez-faire. Hence instead of mercantilism, Smith believed that government should not interfere in economic affairs as free trade increased wealth.

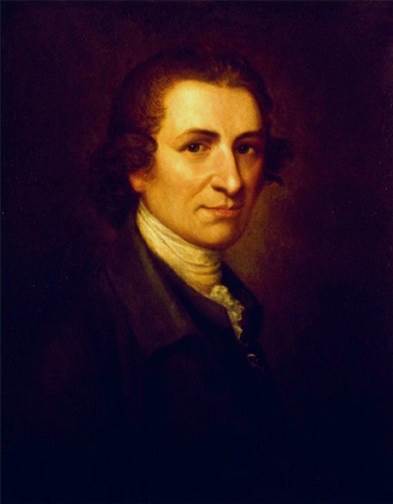

The Rights of Man by Thomas Paine (1737-1809)

The Rights of Man by Thomas Paine (1737-1809) Paine was another important figure in the history of the French and American Revolutions, best known for his works, Common Sense (1776) and The American Crisis (1776-1783). His ideas were rooted in the theories of Locke and Rousseau. In The Rights of Man, Paine turned his attention to the French Revolution to examine the nature of human rights. As a champion of democracy and republicanism, he reasoned that an ideal government is one that would support mankind’s unalienable natural rights (life, liberty, free speech, and freedom of conscience) and that a revolution was permissible if the state failed to benefit its people.

The Vindication of the Rights of Woman by Mary Wollstonecraft (1759-1797)

The Vindication of the Rights of Woman by Mary Wollstonecraft (1759-1797) Mary Wollstonecraft’s The Vindication of the Rights of Woman was a powerful and ground- breaking work of feminist literature and philosophy. In it, she argued for reform of women’s education, and an increase in women’s contribution to society. Wollstonecraft saw that the prevailing pedagogical theories were turning women into feminine beings, ill-prepared for life vicissitudes. She wanted women to become rational and independent beings, whose sense of self came from the development of their mind rather than a mirror.

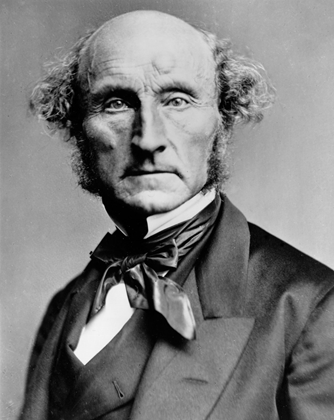

On Liberty by John Stuart Mill (1806-1873)

On Liberty by John Stuart Mill (1806-1873) John Stuart Mill was one of the most influential philosophers of the nineteenth-century and an advocate of utilitarianism, a theory based on the works of Jeremy Bentham. His book On Liberty (1859) made him famous as a defender of human rights. He argued for the right of the people to live as they wished as long as they didn’t do harm to others. Mill also believed that happiness was the basis for morality and encouraged any action which maximised the greatest happiness of the greatest number of people. Mill was the leading liberal feminist of his day. He defended the rights of women on equal terms with men in The Subjection of Women (1869) and proposed measures such as votes for women. As with On Liberty, Mill stated that his views on the emancipation of women were deeply influenced by his wife, Harriet Taylor, an early advocate of women’s rights.

La Nausée by Jean-Paul Sartre (1905-1980)

La Nausée by Jean-Paul Sartre (1905-1980) Sartre was the best-known twentieth-century exponent of existentialism, and, together with Simone de Beauvoir, had a considerable influence on French intellectual life in the decades following the Second World War. La Nausée was Sartre’s first novel, published 1939. It is an attempt to capture in fictional form the human experience through the lens of Phenomenology and Existentialism. The novel’s hero, Antoine Roquentin, undergoes an existential crisis in the course of which he loses confidence in the old‐established values and identities of ordinary social life. The protagonist comes to realize that he is a free agent and must find his own purpose in a world devoid of meaning.

The Second Sex by Simone de Beauvoir (1908-1986)

The Second Sex by Simone de Beauvoir (1908-1986) Simone de Beauvoir was a French existentialist philosopher and author of The Second Sex. It is a foundational text of feminism which looked at women’s oppression under patriarchy. In it she argues that ‘one is not born but one is made a woman’ which suggests that being a woman is not an essential, biological condition but is the effect of socialization and acculturation.

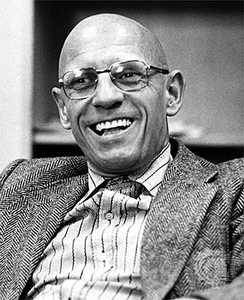

The History of Sexuality by Michel Foucault (1926–1984)

The History of Sexuality by Michel Foucault (1926–1984) Foucault was a French philosopher, historian of ideas, and theorist. His work showed in particular how nineteenth-century obsessions with classification led to the construction of sexual identity categories and how social, political and economical forces sought to influence and control attitudes towards sex and sexual behaviors.

Featured image credit: Book-covered walls by Eugenio Mazzone. Public Domain via Unsplash.

The post Twelve philosophy books everyone should read: from Plato to Foucault [slideshow] appeared first on OUPblog.

Why We Fall for Toxic Leaders

The Oxford Word of the Year is a word or expression chosen to reflect the passing year in language. Every year, the Oxford Dictionaries team debates over a selection of candidates for Word of the Year, choosing the one that best captures the ethos, mood, or preoccupations of that particular year. The 2018 Oxford Word of the Year is: toxic.

It is the sheer scope of the word’s application that has made toxic the stand-out choice for the Oxford Word of the Year. Here, Jean Lipman-Blumen, the author of The Allure of Toxic Leaders, reflects on the lure of following toxic leaders.

School shootings, terrorism, cyberattacks, and economic downturns open the door to toxic leaders. Small wonder these dangerous, seductive leaders attract followers worldwide. Toxic leaders typically enter the scene as saviors. They promise to keep us safe, quell our fears, and infuse our lives with meaning and excitement, perhaps, even immortality. Yet, as history grimly attests, they routinely leave us far worse off than they found us.

We are most vulnerable to toxic leaders when our sense of safety lies at low ebb. Leaders who vow to make us “great again” may actually create, not simply exacerbate, our anxieties. Their grandiose illusions require only the simplest response: total acquiescence. That is the tip off, the smoking gun. Still, their seductive offers usually prove irresistible.

The temptation to follow toxic leaders has deep roots, first, in our existential anxiety, the knowledge that, inevitably, we all physically die. We struggle mightily to ignore that inexorable clock ticking deep inside us. Yet, when cascading massacres and other crises assault our senses, we taste our own mortality. “Active shooters” and exploding packages are just the latest entries in a growing catalogue of death-dealing disasters that stir our existential anxiety.

Predictably, toxic leaders step forward to reassure us that they alone can avert our “appointment in Samarra,” annihilate our human “enemies,” and assuage our social disadvantages—but only if we pledge allegiance to their flag.

A second and related root of our vulnerability to toxic leaders feeds on our deep hunger for meaning and intensity in our lives. This yearning increases our vulnerability to toxic leaders’ promises of an exhilarating existence, etched forever in human memory. We can console ourselves about the prospect of physical death if an intense life opens the door to immortality. As Napoleon knew so well, “There is no immortality but the memory that is left in the minds of men.”

In their call to arms, toxic leaders identify the “Other,” whom we must vanquish to satisfy these needs. Naming the “enemy” not only explains our discontent. It also ignites fierce emotions that goad us on: anger, hatred, distrust, envy, even greed. Meaning and intensity fuse.

In our ordinary lives, we all live intensely at key moments: the birth of a child, the loss of a loved one, the discovery of love. Toxic leaders, however, guarantee us incessant intensity, heated by a flame of fury, hostility, and revenge. They continue to feed that fire until it engulfs not only the despised “Other,” but the followers, and, eventually, even the toxic leader. That followers, themselves, face dangers large and small from toxic leaders is evident in the number of loyalists’ lives lost, careers curtailed, and resources ravaged.

A third deep root of our “fatal attraction” to toxic leaders: by supporting them, we become “the Chosen,” special individuals, sheltered within the privileged “center of action.” Within that sacred space, key decisions are shaped—mostly in our favor. Even when we are not part of the toxic leader’s inner circle, our dedication to that vision anoints us as valued members of “the base.” The catch: as “the Chosen,“ we feel compelled to squelch any rising doubts, much less act upon them, lest we face eviction from the Garden of Eden. Witness the steady stream of ousted White House staff whose slightest deviations have pushed them outside looking in.

What effective countermeasures, if any, can we take?

Most importantly, we can face up to our fears and stare them down. Confronting anxiety stimulates both resilience and creativity. As psychologist Kurt Lewin noted, this exposes us to change, prompting us to experiment, learn, and innovate still more. Innovation, itself, seasons life with fervor. Galvanized to invent novel solutions, we create new institutions that reduce our fears. And, ironically, acting despite our anxiety takes courage, the active ingredient in true heroism, the one real path to immortality.

Next, we can seek “dis-illusioning” leaders, who shatter our illusions, forcing us to face reality, opening the door to self-reliance, confidence, and growth. “Dis-illusioning” leaders teach us to engage in the “valuable inconvenience of leadership,” that is, sharing the hardships of leadership and developing our “leader within.” These tough-minded leaders demonstrate that, far from being the privilege of a select few, leadership is the responsibility of us all, whereby we learn to shoulder life’s burdens with strength and grace.

One more weapon against toxic leaders: select—or better yet—become a “connective leader.” These valuable leaders easily identify even the slimmest mutuality in conflicting agendas of diverse, but interdependent, groups. They help us see ourselves “completed”—not diminished—by our connection to others, as the Nguni Bantu concept of “Ubuntu” suggests. Connective leaders enable us to reject the “we/they” dichotomy, opening possibilities for comradeship, collaboration, and even more creativity. By becoming our most complete selves, we find the intensity and meaning we’ve been seeking.

Living as connective leaders, we engage in enterprises devoted to the common good, beneficial and supportive to all—like global, enduring, and sustainable peace. As “complete” persons, we can join with others to live intensely, with purpose, and possibly—just possibly—set the world on a better trajectory. Combined, these strategies offer strong defenses against toxic leaders.

The choice is ours. The time is now.

Featured image credit: Photo by rob walsh. Public domain via Unsplash.

The post Why We Fall for Toxic Leaders appeared first on OUPblog.

November 14, 2018

The unbroken etymology of “bread”

Some preliminary conclusions about our subject appeared last week (see the post for November 7, 2018). Those are not particularly promising. It appears that once upon a time the product we associate with bread was called hlaif-; its modern reflex (continuation) in English is loaf. What that hlaif– looked like is unknown. In any case, some time later, bread appeared and was called brauð– (ð = th in Engl. the). The hyphens after hlaif– and brauð– mean that those are the roots of the two words, with their endings omitted. According to the data of archeology, the earliest cereal product people consumed was some kind of pancakes, but of course, we have no idea what those pancakes were called. The cruelest law of etymology has it that, if we don’t know the properties of the object under discussion, we have no chance of discovering the origin of its name. Therefore, all derivations of loaf and bread are and will remain moderately intelligent guesswork.

In our case, we are doomed to examine roots, trying to decide which of them might fit what we today call bread. The favorite of most dictionaries is the idea that bread is related to the verb brew, because the word brauð– allegedly designated leavened bread, and yeast is brewed. Bread made with yeast was well-known in Ancient Egypt, but this fact tells us nothing about the food industry among the earliest Germanic speakers. Anyway, bread is a Germanic word of relatively narrow distribution. Unlike bread, brew has wide Indo-European connections: Classical Greek broûtas “beer,” Latin defrutum “boiled must,” and Old Irish bruthe “broth.” Naturally, Engl. broth belongs here too. Beer, must, and broth are “brewed,” but bread is not, even if we insist that the product called brauð– was prepared with yeast. A new product can be called after its ingredient, but what would the meaning of bread have been? “A food made with yeast”?

Here is a brewer. Next, you will see a baker. Are they related? Image credit: Hook Norton Brewery by Matt Hamm. CC BY-NC 2.0 via Flickr.

Here is a brewer. Next, you will see a baker. Are they related? Image credit: Hook Norton Brewery by Matt Hamm. CC BY-NC 2.0 via Flickr.James A. H. Murray, the first editor of the Oxford English Dictionary, did not think much of the yeast etymology of bread and followed a suggestion of the great German philologist Eduard Sievers. The original name of “bread,” both of them explained, appears to have meant “pieces, bits, fragments.” According to the evidence of several Old English glosses, two Latin words for “bits, morsels” were translated into Old English as brēadru and bitan (both forms are plural). Murray concluded that loaf had been used for an undivided article, while bread designated pieces of the same product. When the first volume of the OED appeared, one of the reviewers celebrated the fact that bakers and brewers had been shown to go different ways. The reviewer was too fast and allowed his enthusiasm to run away with him.

Here is a baker. Are they related? Image credit: Wily Jaciw, master baker at Boudin Bakery in the Fisherman’s Wharf district of San Francisco, California by Carol M. Highsmith. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Here is a baker. Are they related? Image credit: Wily Jaciw, master baker at Boudin Bakery in the Fisherman’s Wharf district of San Francisco, California by Carol M. Highsmith. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.A word, allegedly supporting this etymology, is German Brosamen “crumbs.” Its root is bros-. (The singular exists but is rarely used, for what is one crumb?). Brosamen poses no difficulties: bros- is related to an ancient verb meaning “to break” (Old English had brēotan, a word now lost, except in the root of brittle). Its German synonym Brocken is related to another verb of the same meaning (German brechen, Engl. break). No direct connection between Brosamen and brauð– (Engl. bread, German Brot) seems to exist. It also looks odd that a special word designating pieces of bread would have ousted an old “respectable” name of a traditional “unbroken” product. For example, pita, whether from Germanic or Aramaic, appears to have meant “bit,” but it did not supersede any of its rivals. More probably, the word for “bread” could also be used for “pieces of bread.”

A scribe working on glosses (as we think). Image credit: Accueil scribe invert by Philippe Kurlapski. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

A scribe working on glosses (as we think). Image credit: Accueil scribe invert by Philippe Kurlapski. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Still another attempt connects bread with the verb to brook “to endure.” In English, it is archaic and occurs only with a negation (I cannot brook this behavior). It once meant “to use, to enjoy” (German brauchen means “to use”). According to a rather weak hypothesis, bread is related to brook and once meant “a product one uses (enjoys)”. One wishes for a more concrete tie between the name and the object.

Unexpectedly, the pivotal word that may shed light on the etymology of bread is the compound bee-bread (Old Engl. bēo–brēad). It means and meant “honeycomb.” The only way to interpret this word, which has exact analogs in two other Old Germanic languages, is to gloss it as “bees’ food.” This compound makes some traditional hypotheses suspicious and even useless. Bread must have meant “food, sustenance, as it still does in our daily bread and other similar phrases, though some nicer shades of meaning escape us. For instance, meat also meant “food,” as it still does in the phrase it’s meat and drink to me.

“A thing brewed” and “a thing broken” begin to look like rather improbable original senses. We need a meaning that will make it clear how brauð-, admittedly, an innovation, differed from hlaif-. “A thing enjoyed” sounds too vague, and from a linguistic point of view bread and brook are hardly related. Was hlaif- a liquid or polenta-like food, as I suggested last week, while brauð– was solid? What was the technology of making bread? Or is bread a borrowing from the neighbors who knew something about cereals the Germanic speakers did not know? A parallel process would have been the borrowing of hlaif– by the Slavs (that is why khleb has no Slavic etymology).

It remains for me to say what people can find in dictionaries. The Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology repeats the hypothesis given in the OED but adds the cautious perhaps. Since that time, the lexicographers at the OED must have discarded Murray’s idea, for The Shorter Oxford now says: “Origin unknown.” Skeat, at the end of his life, was noncommittal. The Old English word, he only wrote, “sometimes means ‘bit’ or ‘piece’.” Weekley supported Murray. The Century Dictionary and Henry Cecil Wyld (The Universal Dictionary of the English Language), both known for their excellent etymologies, advocated the brewing idea, without offering any discussion. Surprisingly, the 2013 etymological dictionary of Proto-Germanic does the same (a brief statement without a line of comment), and, unfortunately, the same holds for some German and Icelandic reference books, though the latest etymological dictionary of German (Kluge by Seebold) gives an unusually detailed survey of the main opinions and refuses to choose the best one. However, it seems that Seebold favors the brook/brauchen idea.

Origin unknown? Yes, alas. Only food for thought, but I am sorry for a lay reader who thinks naively that a solid dictionary contains the truth about solid foods.

Featured image credit: Breaking bread, juice, dinner party, Broadview townhouse, Seattle, Washington, USA by Wonderlane. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The unbroken etymology of “bread” appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers