Oxford University Press's Blog, page 217

November 6, 2018

The German Revolution of 1918-19: democratic ancestry or subjective liberation?

On 9 November 1918 in central Berlin, Philipp Scheidemann, a leading moderate Social Democrat, and Karl Liebknecht, an antimilitaristic renegade who was soon to co-found the Communist Party, announced the end of the German Empire and the beginning of a new political era. Both tried to give direction to a revolution that had begun as a protest movement against the war and the attempts by some officers to continue fighting in the face of defeat. However, both politicians’ speeches attest to the difficult heritage which the revolution bequeathed to Social Democrats and Communists. From a balcony of the Reichstag, Scheidemann hailed a resounding victory for the German people, while also admonishing them to maintain “quiet, order, and safety” and respect the “ordinances” and “proclamations” issued by the new authorities. Such statements came back to haunt his party, for it has often been faulted for containing popular unrest rather than marshalling it for social transformation. Liebknecht confidently proclaimed “the new socialist freedom of workers and soldiers”, which later earned him a place among the German Democratic Republic’s venerated ancestors. Yet, the religious language in which he evoked the “ghosts” of countless victims of total war and proletarian struggle marching past the Berlin Palace always sat oddly with a system based on “scientific” Marxism-Leninism.

The German Revolution of 1918-19 has never been easy to identify with, and its hundredth anniversary once again throws this difficulty into sharp relief. The balance has lately shifted toward acknowledging moderate revolutionaries’ achievements, namely that they ended the war, introduced universal suffrage at all levels, and built the foundations of the welfare state. While it is salutary in principle to appreciate Germany’s often forgotten democratic history, there is a price to pay for downplaying the complexity of the transition from wartime to postwar society in favour of a political narrative for our times. This transition was replete with spontaneous acts and idiosyncratic utterances. Ordinary people played cards in the workplace and started political arguments on the tram. They marched into noble estates to demand support, churches smoking cigarettes and waving red flags, and elementary schoolrooms to remove pictures of the Prussian kings. All this reflected a quest for subjective liberation after years of military or quasi-military discipline that does not always lend itself to retrospective identification. What are we to make of workers’ and soldiers’ councillors who drove around in commandeered cars for pleasure, arrested a condescending lawyer without any legal grounds, or defended children against corporal punishment by punching their female teacher?

This multi-faceted quest for freedom and dignity posed a problem for the left parties of the time because it did not fit into their respective ideological frames. Social Democrats expressed disappointment with a widespread lack of inner discipline, of morally governed selfhood. Communists bemoaned the fact that “proletarians’ will to independent action” had been worn down in the trenches, although they continued to believe in a second revolution. Independent Social Democrats, in an uneasy position between moderates and radicals, complained either that the German people were devoid of the energy of their Romanic or Slavonic counterparts, or that they possessed the energy but lacked strong leadership. In the winter and spring of 1919, coup attempts, short-lived council republics, and mass strikes followed in rapid succession. Meanwhile, in tranquil Weimar, Social Democrats were busy drafting the Republic’s constitution together with political Catholics and left liberals. At the time of its first anniversary, no party felt able to own the revolution, instead looking back at a mere “elementary collapse”. Radical workers, too, questioned how much had really changed. “Didn’t we build the railway so we could ride on it?” asked one miner in the Ruhr area, “yet, at best we get to travel third-class, mostly fourth-class, while the fat cats are sitting back on cushions in first or second class.”

Against the backdrop of a multi-faceted quest for subjective liberation, a revolutionary subject was keenly sought after but frustratingly evanescent. Hence, the German Revolution of 1918-19 lacked a clear narrative and was soon told as a story of failure. It is doubtful whether its protagonists can serve as models for today’s democratic politics. But the popular irreverence, exuberance, and urge for a better life merit our curiosity.

Featured image credit: Bundesarchiv Bild 146-1972-029-03, Rätezeit by Unknown. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The German Revolution of 1918-19: democratic ancestry or subjective liberation? appeared first on OUPblog.

Stress management in the work place [infographic]

Employees in the modern work force are faced with obstacles every day that prompt stress. These work-related stressors can lead to different kinds of strains that affect both the health and the well-being of the employee and the organization. Various types of stress management interventions, guided by organizational development and work stress frameworks, may be employed to prevent or cope with job stressors and manage strains that develop.

Using the Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Psychology, we’ll define these stressors and strains and then explore some stress management techniques.

Feature image credit: Photo by rawpixel on Unsplash.

The post Stress management in the work place [infographic] appeared first on OUPblog.

The fiddle and the city

The violin holds special importance to me as part of my upbringing in Detroit, both as part of the musical world of my Jewish community and as an example of the citywide belief in music education. The Detroit that I grew up in had a pulsating inner musical life from the many populations that Detroit attracted to and housed in its vast industrial landscape. For the Jews, the violin literally had a special resonance. It was the lead instrument in the traditional klezmer dance bands for weddings. In the east European homeland, people thought the fiddle had unusual power as an expressive vessel. It was not just an instrument, but a voice, a tool for meditation in the slow pieces played around the tables at a celebration. Then the fiddles kicked in and got people up and dancing. As the older folkways faded, the enormous success of Jewish virtuoso concert artists like the ones I heard at Masonic Temple only raised the violin to a new height of enjoyment and pride.

Another example of how the violin was important in my Detroit is the way that music cut across social boundaries. It wasn’t just me that picked up the violin; across the city, in every neighborhood, elementary schools handed out instruments to small children, often setting up a career for life that way. That child could be Armenian, African American, or Appalachian in family origin. In my research, I’ve talked to the Kavafian sisters, who have had impressive concert careers, and Michael Ouzounian, principal violist for the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra for decades, representing the Armenian story. In fact, they were taught by another compatriot, Ara Zerounian, who became the Kavafians’ stepfather. In the famous Cass Technical High School Orchestra, I shared a stand with Darwyn Apple, a pioneering African American orchestra player who had a long career in St. Louis. Also near me were the Barnes Brothers, Robert and Darrel, who worked in the Boston and Philadelphia Orchestras later. Their family was from Louisville, and even their mother was a rare woman professional musician in Detroit.

The educational system believed in music as not just a leveler, but a career path in those days. So despite all the roadblocks Detroit’s charged and often violent streets put up, there were still green lights at some intersections of experience. The public school system in Detroit had a long-term effect on the dozens of children who went on to active lives in music from Detroit. I think of it as a traffic circle: people come from many directions, spin around the circle, and go off at different angles to various destinations. Some musicians, like those I just mentioned, got on a career highway that might well take them away from Detroit, whereas others went back to their neighborhoods, becoming, for example, major polka band leaders who could use their skills in ensemble and arranging within their communities. It’s one of the fascinating and little-known stories about the musical life of Detroit at its peak of civic striving.

A series of three family photos bring the story closer to home:

Image credit: used with permission of the author.

Image credit: used with permission of the author.Here’s my great-uncle Maurice/Moishe (depending on context), who came to Detroit in 1912. He loved the classical violin, but making a living as a salesman didn’t leave him much leisure time. He took me to concerts by the world’s greatest artists – Mischa Elman, Jascha Heifetz, Nathan Milstein, and the rest. He also took me to Detroit Tigers games. The combination of classical music and baseball marks the American Jews of his and the next generation.

Image credit: used with permission of the author.

Image credit: used with permission of the author.Here’s my father, born the year before Uncle Moishe arrived in Detroit. He was supposed to play the violin, but they didn’t have Suzuki in those days and he got discouraged fast. You can see by his position that he isn’t taking the fiddle seriously.

I inherited his 1920s violin and recently donated it to a public-school program in New York City for kids that can’t afford to buy instruments.

And here’s the self-explanatory picture (thanks for the captions, Mom) of me at age four, happy to be starting my lifelong journey with the violin. Going to those recitals, even at such a tender age, inspired me, and we had a great family friend, Ben Silverstein, who somehow got me going on a one-quarter size instrument.

Image credit: used with permission of the author.

Image credit: used with permission of the author.His son became the concertmaster of the Boston Symphony, so I guess Ben knew a thing or two about teaching kids. Tragically, he was killed in a car crash only five years later (no seat belts back then), but I continued with other teachers, three of whom, all in the Detroit Symphony Orchestra, later moonlighted for Motown. A couple of those classical fiddlers also put on other outfits to play in a Latin band. It was all part of the musical merge that so marked Detroit’s history in its heyday.

Featured image credit: Requiem by Cameron Mourot. Public Domain via Unsplash .

The post The fiddle and the city appeared first on OUPblog.

November 5, 2018

Life science documentaries

OUP is constantly publishing new and exciting research spanning all kingdoms of life. We continually strive to bring you, the OUPblog readers, the most relevant and interesting content to support and expand your knowledge of the life science realm.

One way we do this is by posting accessible, listicle-style blog posts to accompany prolific nature documentaries, such as those narrated by the eminent Sir David Attenborough. Did that moving episode of Blue Planet II pique your interest? Or are you excited to discover the secrets of animal families in Dynasties? Delve deeper into key themes raised in these programmes by exploring our existing blog series below, and be sure to check back for more content relating to popular documentaries in future.

Sir David Attenborough will shortly be returning to our screens narrating a new nature documentary: Dynasties. Over the course of five weeks, this series will follow individual animals – chimpanzees, emperor penguins, lions, painted wolves, and tigers – as they protect and lead their respective social units.

To accompany each episode, we will be publishing a blog post about each species featured in the show, focusing on their interactions with other members of their species. Be sure to check back after every episode to keep up-to-date with our blog series!

Chimpanzees and their community

One of our closest relatives in the animal kingdom, chimpanzees are known to exhibit some very human traits in the wild. For the first blog in the series, we’ll be delving into the social dynamics of chimpanzee ‘communities’, examining how they are structured and how they interact with rival communities.

Emperor of all penguins

Of the seventeen species of penguin in existence, the emperor penguin is arguably the most well-known and heavily documented. In the second blog post of the series, we’ll be exploring how emperor penguins and their flippered relatives interact with each other to build their respective dynasties in the chilly Antarctic.

Lions with pride

Lions and lionesses alike exercise their prowess to protect their pride, causing them to be considered one of the most respected and feared creature of the animal world. To accompany the third episode of the documentary, we’ll be sharing some facts about the social interactions of these fierce beasts of the savanna.

Painted wolves on the prowl

Tasked with cooperating as a pack to survive, painted wolves – also known as ‘African wild dogs’– are unusual in the animal kingdom due to their cooperative social system. In the penultimate post of our blog series, we’ll be examining the social dynamics of a painted wolf pack.

Tigers and their solitary homes

Tasked with closing Dynasties, tigers are very unlike any of the other species featured throughout the series, preferring to live alone rather than cooperate in large social groups. Find out more about this solitary big cat through our selection of facts about how tigers behave and interact with others.

Blue Planet returned to our television screens in 2017 as Blue Planet II, 16 years after the first series aired to great critical acclaim. The series, fronted by Sir David Attenborough, focuses on life beneath the waves, using state-of-the-art technology to bring us closer than ever before to the creatures who call the ocean depths their home.

Over the course of seven weeks, we shared a selection of facts relating to each episode of the series, with posts published across the OUPblog and our Tumblr page. Explore each week’s collection of facts about our oceans by following the links below.

One Ocean: Blue Planet II returns

The series begins with an overview of our oceans – no small feat considering the ocean covers over 70% of our planet’s surface. Covering a wide range of facts about our wild and wonderful oceans, as well as some research touching on the themes of future episodes, read this introductory blog to whet your appetite for the rest of the series.

The second episode of Blue Planet II takes us to the deepest, darkest depths of the ocean floor, where crushing pressure, brutal cold, and pitch-black darkness make this one of the most extreme environments on our planet. To accompany this episode, discover alien worlds, volatile landscapes, and a host of bizarre creatures that call this almost-inhospitable environment their home.

Coral reefs are home to a quarter of all marine species, so it is fitting that they are the focus of Blue Planet II’s third episode. Exploring the vast array of different marine life that live here – from green turtles and bottlenose dolphins, to manta rays, octopuses, and parrotfish – this episode demonstrates how these different creatures have adapted to survive in these underwater mega-cities.

Episode four of Blue Planet II takes us into the open ocean. An isolating environment far from shore, the Big Blue presents unique challenges for the creatures who call it home including increased competition for mates and food. Learn more about the open ocean and the impact of human activities on it in this post.

In the fifth episode of Blue Planet II, we are introduced to our ‘Green Seas’ – vast forests of kelp, blooms of algae, and large expanses of sea grass – where an array of creatures battle fierce competition with one another, adapting in order to survive.

The penultimate episode in our Blue Planet II series takes us to the coast, where land and sea collide. In this episode, we meet creatures who alternate between these two very different domains, and learn how they adapt to survive in this ever-changing environment. What are some of the most notable aspects of this bridge between two worlds?

The final post in the series looks to the future and asks, “What will our oceans look like five, ten, twenty years from now?”, examining the ongoing issues of marine pollution, climate change, and other human activity that impacts our oceans. This momentous episode highlights the issue of plastic pollution, driving a nation to pledge to cut down on the use of plastic.

Featured image: Landscape Coast Shore by Free-Photos. CC0 via Pixabay .

The post Life science documentaries appeared first on OUPblog.

The history of The Declaration of the Rights of the Child

Virtually every news cycle seems to feature children as victims of military actions, gun violence, economic injustice, racism, sexism, sexual abuse, hunger, underfunded schools, unbridled commercialism—the list is endless. Each violates our sense of what childhood ought to be and challenges what we believe childhood has always been.

But the ideas that shape our notions of childhood emerged less than a century ago. Reformers and policy-makers had struggled toward creating a modern childhood since the 1830s. They sought to build an extended, nurturing childhood, one that freed children of responsibility and allowed them simply to be children. Their efforts led to modest improvements in education, efforts to eliminate the worst forms of child labor and somewhat better medical care.

By the early 1900s, enough progress had been made—both in terms of material improvements and rising expectations—that the American social worker, civil rights advocate and anti-child labor activist Florence Kelley could declare in Some Ethical Gains Through Legislation that youngsters had “a right to childhood.” But the catastrophic effects of the First World War on civilians in general and children in particular energized child welfare reformers, including Eglantyne Jebb, the Englishwoman who founded the Save the Children Fund. Jebb would be one of the leading figures in the movement that led to the “invention” of childhood in 1924.

Of course, there have always been children, and through most of history their experiences have naturally differed from those of adults. Yet, on 26 September 1924, when the League of Nations adopted the “Geneva Declaration of the Rights of the Child,” it recognized not only their different needs and roles in society, but established benchmarks against which communities’ or nations’ treatment of children could be measured. In so doing, the League established the standards for a childhood that resembled one that we would recognize as “modern.”

The Declaration’s preamble declared “that mankind owes to the Child the best that it has to give.” “Beyond and above all considerations of race, nationality or creed,” children possessed certain rights simply because they were children. It affirmed:

The child must be given the means requisite for its normal development, both materially and spirituallyThe child that is hungry must be fed; the child that is sick must be nursed; the child that is backward must be helped; the delinquent child must be reclaimed; and the orphan and the waif must be sheltered and succoredThe child must be the first to receive relief in times of distressThe child must be put in a position to earn a livelihood, and must be protected against every form of exploitationThe child must be brought up in the consciousness that its talents must be devoted to the service of fellow menThe Declaration emerged from empathy for children that had been building for decades. Yet the promises it made would ring hollow in the face of a world-wide depression, and a second, even more devastating world war. Indeed, violence and disorder would plague children’s lives for the rest of the 20th and into the 21st centuries.

Yet the hopeful words of 1924 set a precedent that would eventually create a set of assumptions about children’s rights that would become nearly universal. Of course, many nations struggled to fulfill those assumptions, but the League’s successor, the United Nations, would pass much-expanded statements on children’s rights in 1959 and again in 1989. The ideals articulated in the Declaration would inspire the creation of the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) in 1946 and the founding of countless governmental agencies and NGOs around the world dedicated to the relief and well-being of children. Despite the many challenges that have emerged during the century since the League issued the Declaration, it remains a beacon reminding the world community of its shared responsibility to advocate for the “right to childhood.”

Featured image credit: “Children forced from their homes in Ekaterinodar (now Krasnador) during the Russian Civil War, 1919.” Public domain via Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division,

The post The history of The Declaration of the Rights of the Child appeared first on OUPblog.

Does the personalisation of politics have any benefits for democracy?

Democracy in the twenty-first century appears to have reached a fork in the road. On the one hand, over recent decades we have witnessed an explosion in the popularity of democratic norms and values around the globe to the extent that all but two countries label themselves as democracies, which if nothing else indicates how dominant this norm has become. On the other hand, particularly in those states where it is the long-established mode of political decision-making, citizens appear to be deeply disaffected with how democracy is practised. Even putting the election of Donald Trump and the recent Brexit referendum to one side, the long-term trend across Europe and America sees voter turnout declining, political parties struggling to retain members, and professional politicians increasingly despised or deemed untrustworthy. Outside these regions, in new or transitioning democracies, democratization scholars fear that progress has stalled, and that in the absence of strong structural bulwarks against authoritarian rule the triumphant march of democratization may have halted.

The tendency for politics to become dominated by the personalities of its leaders rather than ideology or policy programme is a key theme in this discussion. Most scholars argue it is a rising feature of political life that produces negative effects (see Poguntke & Webb 2005; McAllister 2007; Balmas et al. 2014). In particular, personalization is assumed to negatively affect political representation, because the limited relevance of political ideologies and platforms makes politicians less accountable to their voters. In this view, democracy has arrived at a significant fork in the road. And, worryingly, we don’t appear to know which way to go.

We have been fascinated by these themes because we study very small states (they have population of less than 1 million). As our forthcoming book Democracy in Small States: Persisting Against All Odds shows, personalism is and always has been ubiquitous in societies where citizens and politicians meet and engage with each other on a day-to-day basis. As a result, if personalization is global trend then we have a lot to learn about its effects, negative or otherwise, by studying the way politics works in micro cases. In particular, because small states are, statistically speaking, much more likely to be democratic than large states, personalisation may have unanticipated benefits for the resilience of democratic governance.

To explain this resilience, one of the questions we sought to answer in the book is how does domestic politics actually work in small states? And, having established this, does it conform to the negative depiction of personalisation or does the statistical correlation between country size and democratization point to hidden benefits? We studied 39 small states with populations of less than 1 million to answer these questions, conducting over 250 interviews with elite actors in the process. Despite the incredible diversity of these states (they come from five world regions and vary in terms of all the standard variables political scientists use to compare democracies, including levels of economic growth, colonial legacy, institutional design, party system etc.), we found that the practice of politics is remarkably similar. Key characteristics include:

Strong connections between individual leaders and constituents. Rather than being mediated by party systems, in small states voters and politicians have considerable opportunities for direct, personal contact. This tendency is amplified by the overlapping private and professional roles that politicians undertake. Politicians are more than just legislators: they are family or clan members, friends, neighbours, or colleagues.A limited private sphere. Contemporary democratic politics in large states is characterized by a distinction between public and private, with the institutions that define the former regulating conduct in the latter. In small states, the private sphere is dramatically reduced while the public sphere is expanded beyond the narrow confines of formal institutions. The result is a remarkably transparent political system but also one in which clear lines of accountability are blurred and concern with corruption is magnified.The limited role of ideology and programmatic policy debate. Leaders are largely elected because of who they are rather than what they stand for. As a result, political contestation focuses on the qualities and characteristics of individual politicians rather than party manifestos. Indeed, a number of Pacific Island states, such as Tuvalu or the Federated States of Micronesia, do not have political parties at all.Strong political polarization. The absence of ideological difference should theoretically breed consensus but in fact, small state politics is often characterized by extreme polarization. Political competition between personalities is often fiercely antagonistic precisely because they have few ideological differences, and therefore politicians have to focus on personal disagreements to differentiate themselves. In combination with the limited role of parties, this also potentially creates political instability, as political alliances are regularly broken.The ubiquity of patronage. In small states nobody is faceless. Relatives and friends stick together in more visible and unavoidable ways. This leads to political dynasties and various other types of collusion. It also means that politicians in small states typically experience considerable pressure from constituents, who are often the same relatives and friends, to personally provide material largesse. Failure to do so can lead to electoral defeat. Patronage in the public sector is also common in small states, and public sector appointments are often made on the basis of political loyalties.The capacity to dominate all aspects of public life. An expanded public sphere and the absence of specialist roles create opportunities for individuals to dominate politics in a manner that is virtually impossible in large states. Pluralism is uncomfortable and dissent is often stifled while dependent constituents can be easily bought off.Based on these similarities, we argue that hyper-personal politics has both the democracy-stimulating and repressive characteristics. For example, the familiarity between citizens and politicians is often regarded as democracy-enhancing, as it creates better opportunities for political representation and responsiveness. In addition, this closeness can foster political awareness, efficacy, and participation among citizens because political decisions often have a direct impact on their personal lives. Moreover, the close connections between citizens and politicians provide a formidable obstacle to executive domination, as their extensive social connections prevent politicians from resorting to full-blown oppression or violence.

But, it is clear that personalism simultaneously presents obstacles. The relative absence of ideology and the focus on political individuals undermines substantive representation. Patron–client linkages create social and economic dependency and unequal access to public resources and strong polarization and personality clashes can breed political instability and turmoil. Moreover, the opportunities for political leaders to accumulate untrammeled powers without the customary ‘checks and balances’ carries the risk of executive domination or dictatorial politics.

Hyper-personalism, it seems, provides mixed blessings for democratic governance, at least in small states. Certainly, not all of the six characteristics we identify are relevant for large states; the benefits of smallness both exacerbate and offset the consequences of personalism. In which case, the hyper-personal politics of small states might prove to be a better outcome than the combination of limited ideology, polarization, and leader dominance increasingly common to large and wealthy western democracies. Either way, these extreme cases highlight that hyper-personal democracy is both possible and yet very different to the experience of North America and much of Europe. The lesson is that rather than personalization precipitating a crisis of democracy, it presents as a crisis for a particular type of democratic politics common to a handful of large and rich states.

Featured image: Photo by Parker Johnson on Unsplash.

The post Does the personalisation of politics have any benefits for democracy? appeared first on OUPblog.

November 4, 2018

Learning from nature to save the planet

Our planet is out of balance as the result of our technologies. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change warns that global temperatures could reach a frightening plus +3° by the end of the century, our ocean ecosystems risk being overwhelmed by non-degrading plastic waste, open rubbish tips scar the landscape and pollute our water supplies with the hazardous leftovers of yesterday’s technology. The race to recycle and reuse, to be more efficient and more sustainable is on, and we know the clock is ticking.

Boosting efficiency or reducing emissions by a few percent is helpful but it may not be enough. Nor is recycling a panacea for the problem of waste; the effectiveness of many recycling processes is low and can never come close to 100%. The information technologies that have transformed our 21st century civilization ravenously consume rare earth metals at unprecedented rates, some supplies will run out in the coming decades, and the computer farms we build to support the internet, artificial intelligence, and blockchain could consume up to 1/5th of global energy by 2025. The information and communications technologies that drive much of today’s industry, public services, and domestic life, from mobile phones to computers and robots, are therefore becoming as much a part of the problem of human sustainability as gas-guzzling cars and coal-fired power stations. What can we do?

There may be a path forward; we can learn from nature to create technologies that are smart, adaptive, human-compatible, but also efficient, resource neutral and that have natural cycles of growth, decay, and re-use. From the use of biological or biomimetic materials, to energy scavenging from biosources, to brain-like learning, perception and cognition using low-power massively parallel hardware, next generation technologies are taking insight from nature to create more sustainable solutions to the challenges faced by our species and our planet.

Take the brain, for example. When Google DeepMind’s AlphaGo beat grandmaster Lee Sedol in 2016 at the game of Go, the energy that AlphaGo consumed in one week was likely more than Lee Sedol had used in his entire life. Human brains are not only the most powerful “computers” we know of, but they are also the most efficient, probably by around five orders of magnitude (100,000x) compared to current supercomputers. Likewise, Sedol gained his Go mastery by playing many fewer games than AlphaGo, demonstrating one key edge that human brains still have over machines—our ability to learn efficiently from a small number of experiences—small data, if you like, rather than big data.

…the patch can be used repeatedly and for a much longer period of time, thus decreasing the potentially negative environmental impact and waste of similar products.

This sort of thing has far-reaching implications for environmental resilience. In one example, researchers have studied the adhesive traits of beetles, which show high adhesion strength even on rough or wet surfaces. Researchers have mimicked this simple trait to create a biomedical skin patch which provides strong adhesion without using wet or toxic chemicals. In this sense, the patch can be used repeatedly and for a much longer period of time, thus decreasing the potentially negative environmental impact and waste of similar products.

These are the kinds of challenges where technology has much to learn from natural solutions. However, the wider benefit is potentially more far-reaching. The chemistry of living systems is very different from the one used in our current technologies. The main elements used in living systems are carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen, phosphorus, and sulphur—amongst the commonest elements on earth (other elements are also used but at much lower concentration—well below 1% of mass). Moreover, these main six chemical elements are involved in natural cycles: the carbon cycle, the water cycle, the sulphur cycle, the nitrogen cycle, and the phosphorus cycle that all intrinsically sustainable. “Living machine” technologies that build on principles harvested from the natural world—and ultimately, perhaps, from the same materials as living systems—could play a crucial in addressing some of humanity’s most pressing problems.

Interestingly, the development of such technologies could also see a narrowing of the gap between living systems and human-made ones, and perhaps, eventually, a rethinking of the nature of life itself.

Featured image credit: Cuckoo Wasp Insect by skeeze. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Learning from nature to save the planet appeared first on OUPblog.

A fresh look at clichés

Recently a friend gave me a copy of It’s Been Said Before: A Guide to the Use and Abuse of Clichés by lexicographer Orin Hargraves. I was intrigued to read it because I had been wondering about clichés for some time.

Clichés are commonplace linguistic forms or formulas that serve a predicable function, much like idioms (under the weather) or stock transitional phrases (on the one hand). Clichés can be helpful when a writer needs to establish or invoke a commonly accepted idea in a way that is well-codified and easy to understand. Those same features, codification and simplicity, can also make commonly used phrases appear trite.

Nevertheless, we rely on them. We may use them when we are writing on a deadline (hence their prevalence in workaday journalism) and we may use them when we are speaking extemporaneously and can’t always aim for thoughtful originality. We may use them because we are lazy or don’t really care about the piece we are writing. Whatever the reason, clichés fill the page or the ear with words and present the illusion of description: we write about a deafening silence, an accident waiting to happen, a recipe for disaster, spilled milk, and death blows.

If clichés are so bad, why do they even exist? New ones arise all the time as part of the life cycle of linguistic forms. What was once a fresh metaphor becomes popular then all-too-common and then clichéd: the once-evocative dumpster fire is already in need of a replacement and the phrase past its sell-by dates may be past its own sell-by date. The most tattered clichés never disappear: fit as a fiddle, alive and kicking, in this day and age, a country mile, seemed like an eternity, and head in the sand are recycled endlessly in the thrift shop of our vocabularies.

Like idioms, clichés can also become so automatic that we may lose track of their literal senses: After the storm, builders came out of the woodwork. It’s time to bite the bullet on gun control. I will touch base with you about baseball on Sunday. Choosing the correct floral arrangement is not so cut and dried. The reader or listener may focus on the clumsy, unintended semantic mismatch. If you are lucky, people will think you are punning!

When we write about new awarenesses, life-changing moments, or matters of great consequence, originality and precision seem to abandon us. We slip into wordy conventional formulas, invoking a palpable sense of dread, a force of nature, or a perfect storm.

My interest in clichés started when I noticed them in the prose of more than a few good writers. I began to suspect that we all fall into clichés when the writing gets uncomfortable—when we are commenting on topics that are emotional or profound. When we write about new awarenesses, life-changing moments, or matters of great consequence, originality and precision seem to abandon us. We slip into wordy conventional formulas, invoking a palpable sense of dread, a force of nature, or a perfect storm.

How does a writer control clichés, or at least become more aware of them? It’s not rocket science. They often stand out like sore thumbs.

As we proofread, we should give any piece of writing to a cliché-check, noting phrases that seem overly familiar and deciding if we really need them or if there is perhaps a better way to express the thought. A quick cliché-check would certainly catch those references to rocket science and sore thumbs in the last paragraph.

If we decide to keep an idea, we might come up with a better, fresher way to say it. Consider the lament I wanted to curl up in a little ball and die. That clichéd way of expressing embarrassment might be recast as I wanted to disappear in a puff of smoke. How about trying I wanted to erase myself? Or if we are expressing frustration and had drafted I ran into a brick wall at every turn, we might consider instead saying I felt like a mime in an invisible box.

Monitoring clichés is as much a part of proofreading as minding your commas, apostrophes, and spelling, and it will make better writers of us all.

I hope we are all on the same page about this.

Featured image credit: Old Brick Wall by Olga Reznik. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post A fresh look at clichés appeared first on OUPblog.

November 3, 2018

Are we misinformed or disinformed?

“Disinformation” is a common term at present, in the media, in academic and political discourse, along with related concepts like “fake news”. But what does it really mean? Is it different from misinformation, propaganda, deception, “fake news” or just plain lies? Is it always bad, or can it be a useful and necessary tool of statecraft? And how should we deal with it?

There are no straightforward answers not least because each of these terms provokes a subjective reaction in our minds. Misinformation could be the wrong information put out by mistake, but Disinformation sounds like a deliberate strategy of deceit. Propaganda might be intended to persuade, maybe exaggerated but essentially harmless; or it could be used by an authoritarian state to brainwash its people. In 1948, the Foreign Information Research Department (IRD) was set up in the UK to combat aggressive Communist propaganda, issuing or sponsoring its own propaganda in return: was one of these bad, and the other good? Former CIA analyst Cynthia Grabo said that if propaganda was true, it was public diplomacy; if false, disinformation. Things are not that simple.

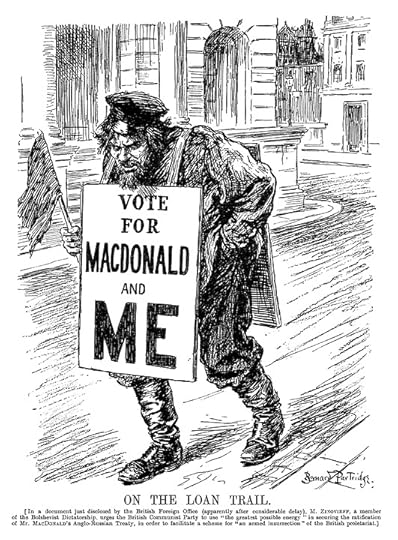

Image credit: On The Loan Trail, 29 October 1924. Cartoon by John Bernard Partridge for Punch, created in the wake of the publication of the Zinoviev letter. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: On The Loan Trail, 29 October 1924. Cartoon by John Bernard Partridge for Punch, created in the wake of the publication of the Zinoviev letter. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Deception is another tricky term. It might seem little different from lies or fake news, but in a military context its meaning can be positive, even celebratory. Think of Operation Fortitude, designed to make Hitler believe the Allied invasion in June 1944 would not be in Normandy; or Operation Desert Deception, executed in the run-up to the First Gulf War to convince the Iraqis the Coalition would attack from a different direction to the one it actually came from. Both these operations involved subterfuge, media manipulation and decoy tactics—lies in fact, disinformation used by the good guys. And if we accept that disinformation can be used for “good” purposes, we are even further into the realm of subjective judgement.

There is nothing new about all this, of course. Disinformation is an ancient concept: Thucydides, for example, identified the deliberate manipulation of information to influence decision-making, and the distorting effects of political polarisation on truth and democracy; Plato thought it was fine for rulers to lie to the populace in the interests of public safety and state security. Both agreed that the intention of those disseminating the information makes a difference, and this is a useful lesson for us today: it is important to try and work out the intent of the source of the disinformation. For example, when considering how to deal with alleged Russian disinformation activity, it is vital to try and see how things look from Moscow, to understand the motivation without necessarily accepting the premise.

The Zinoviev letter is a classic piece of disinformation: probably forged, this document was passed through secret service channels and leaked to right-wing interests during the British General Election campaign of 1924 to damage the Labour Party. One aspect of the affair brings us back to the present day and illustrates the dangers of disinformation. In 1924, the Foreign Office drafted a letter of protest to the Soviet government, in response to what it called an unwarranted act of provocation and interference in the British political process. The evidence (including Russian evidence) suggests that the Politburo initially had not the slightest idea what the British were talking about (one of the reasons to believe the Letter is a forgery). But the Soviet leaders decided very quickly how to respond: firstly, deny everything; secondly, suggest that the British themselves must be responsible for the forgery. This is a classic response, today as well as in 1924. Denial of guilt and an attempt to deflect blame back on the accuser is no guarantee of truth or falsehood in any disinformation campaign. It is a recognised tactic that apart from anything else is intended to convince the domestic audience of what a state wishes its people to believe. Obviously, this is easier to bring off in an authoritarian state, where the media may be constrained, but it can be adopted anywhere.

Today, the speed of communications, social media, international and political instability and a range of other factors combine to create an environment where disinformation can flourish and be used by a range of actors as a tool of policy. There is no point in throwing up our hands in outrage and pretending only bad guys use it. Disinformation is part of strategic communications, of contemporary statecraft. We all need to be on the lookout. In the ancient world, philosophers argued that political authority depends on citizens who think, judge and fact-check for themselves. Defence against disinformation means understanding what might happen if information is compromised, collaborating with others to identify the risk and working together to mitigate it. Recognition of disinformation, and accepting shared responsibility for the risks it brings, is an essential tool in the box of those seeking to protect themselves against it.

Featured image credit: “A man with “fake news” rushing to the printing press, 7 March 1894″ by Frederick Burr Opper. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Are we misinformed or disinformed? appeared first on OUPblog.

From the archive: revolutionary discoveries and celebrated voices [timeline]

Since 1858, countless advancements have been made across all academic fields, whether in medicine, politics, or science, to name a few. Some discoveries and voices have been more revolutionary than others, their names instantly recognisable no matter your specialist field.

From Darwin to Desmond Tutu, and numerous Nobel Prize winners in between, discover which well-known academics have published in our journals over the course of 140 years through our interactive timeline.

Featured image credit: Spins by Luke Chesser. Public Domain via Unsplash.

The post From the archive: revolutionary discoveries and celebrated voices [timeline] appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers