Oxford University Press's Blog, page 219

October 27, 2018

Philosopher of The Month: William Godwin [timeline]

This October, the OUP Philosophy team honours William Godwin (1756–1836) as their Philosopher of the Month. Godwin was a moral and political philosopher and a prolific writer, best-known for his political treatise ‘An Enquiry Concerning Political Justice’ and ‘Things as they were or Caleb Williams’, a political allegorical novel.

Born in East Anglia in 1756, Godwin came from the family of Religious Dissenting tradition and was trained to be a minister, following in his father’s footsteps. He had a change of heart and embarked on a literary career, espousing Enlightenment ideas. In 1796 he married Mary Wollstonecraft, the first major feminist philosopher and the author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman and their daughter Mary Shelley, the famous writer of the gothic novel, Frankenstein, was born the following year.

Godwin was a key figure in the British radical republican milieu. An Enquiry concerning Political Justice, published in 1793, established him as a proponent of philosophical anarchism. It was written during the British crisis in the 1790s when liberty and the questions about the sacred, natural rights of man were on everyone’s mind. Godwin argues that governments should be abolished since they oppress and infringe liberty. Society can only progress if states encourage people to decide and think for themselves on the best course of action. In doing so, their minds and capacity for rational judgment would develop. Godwin argues that mankind has the potential for achieving perfection and this depends on the liberation of the human mind and the removal of authoritarian and irrational institutions. Thus there would be no place in society for state interventions, laws, punishments, or any other forms of political and social controls. Because of his belief in human perfectibility, he even speculates on the possibility of immortality and the elimination of illness and ageing.

The book is also famous for its controversial ‘fire cause’ passage in which he asks his readers to choose between the archbishop Fénelon and his chambermaid. If both were trapped in a burning room where the archbishop was writing his great work ‘The Adventures of Telemachus’, and we could only rescue one of them, should we not save the life of the former who will produce the greatest possible benefits for society? Even if chambermaid turns out to be someone dear, a wife, a mother, and a benefactor, Godwin argues that justice would require that we save the life which is more valuable.

Enquiry was a success upon publication and established his reputation as a philosopher and a writer. Godwin was revered by the first generation of Romantic poets such as Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, William Hazlitt, and Percy Bysshe Shelley. The book’s ideas would later influence the works of philosophers and thinkers such as Marx, Thoreau and Kropotkin.

For more on Godwin’s life and work, browse our interactive timeline below:

Featured image credit: Caspar David Friedrich, Mondaufgang am Meer, Moonrise over the Sea, 1822. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons .

The post Philosopher of The Month: William Godwin [timeline] appeared first on OUPblog.

October 26, 2018

Animal of the Month: More to the bee than just honey

Great truths are often so pervasive or in such plain view as to be invisible. This is the case with bees and their food plants, the world’s quarter million flowering plant species, especially because it’s easy to overlook small things in a world in which whales and elephants hold the imagination of the public. Little do most of us know that the more than 20,000 species of wild bees (Hymenoptera: Apoidea: Anthophila) on our planet are working behind the scenes to pollinate most fruit and vegetable crops and wild plants, providing approximately one-third of the food humans consume. We are familiar, of course, with the domesticated honey bee and its large social colonies, and the occasional bumble bee seen in the garden. But behind the scenes are thousands of small, solitary bees living in the soil and in the pithy stems of overwintering plants, each of which plays an important role in pollinating much of the world’s flora.

Image credit: Bombus Affinis by Johanna James.

Image credit: Bombus Affinis by Johanna James.Bees evolved approximately 125 million years ago in a relatively rapid burst of diversification in concert with the flowering plants (Angiosperms), each dependent on the other for survival. Bees and the small subfamily of vespid pollen wasps (Masarinae) are the only group of Hymenoptera (ants, bees, and the stinging wasps) that rely entirely on pollen and nectar for food and reproduction. Solitary bees are integral parts of most ecosystems, from desert to tropical to alpine temperate communities. The major groups of social bees (honey bees, bumble bees and stingless bees) form colonies of hundreds to hundreds of thousands of individuals. These large, behaviorally complex communities have often been compared to human societies with their complex division of labor and dominance structures, sophisticated communication systems for sharing information, remarkable learning capacity and behavioral plasticity that enables them to respond to changes in their environment. The bees, which retain all the diverse levels of sociality, offer a rare view into the evolution of social behavior.

Image credit: Andrenid by Jim Whitfield.

Image credit: Andrenid by Jim Whitfield.As humans are changing the earth’s environment at an alarming rate, however, it is impossible for bees to adapt in concert to these changes. Precipitous declines of bumble bee populations are accompanied by extirpation from whole regions of Europe and parts of South America, and even extinction or endangered status of some species in North America. Causes of these declines are likely to be multifaceted, but minimally include extensive loss of natural food and nesting resources to accommodate the enormous expansion of agricultural production, accompanying use of harmful pesticides, diseases transmitted via domestication and global transport of colonies for crop pollination and climatic warming.

Unfortunately, the precautionary principle is not used in the U.S. as it is in Europe, where neonicotinoid pesticides have been banned in lieu of obtaining the critical scientific information required to make credible decisions about their continued use. Commercial interests trump environmental interests in most cases, however, a couple of successes in environmental protection of bees suggests the message is getting through at some level. In the meanwhile, we can all do our part to encourage sustained bee populations by the plants and nesting sites we provide in our own gardens, exchanging pesticides and herbicides for weed-pulling exercise.

Featured Image Credit: Bee on Lavander by Alfonso Navarro on Unsplash.

The post Animal of the Month: More to the bee than just honey appeared first on OUPblog.

Why major in dance? A case for dance as a field of study in universities in 2018

Parents, provosts, and authors of recent articles/discussion boards are questioning the purpose or viability for dance programs in contemporary university structures. An article in Dance USA from 2015 presents a narrow view of the role of collegiate dance. Understanding the wider lens on dance education, it can be an excellent path to career success. College programs in dance transcend training an elite artist/athlete. College training educates the student to become an artist/citizen with a depth of expertise in the physical forms as well as the historical, cultural, political and scientific aspects of dance. When Towson University dance major alumni from 2008-2013 were polled, 85.4% of respondents stated they were fully employed in dance or a dance-related field. Students can go on to be dancers, choreographers, and dance educators. In linking dance study with another major they also prepare to become dance journalists, anthropologists, physical therapists, or arts administrators. The dance major also develops skills that translate to other endeavors.

Studying choreography involves developing the skills to conceive, research, design, edit, refine, and collaborate to produce a creative product, and move it from the rehearsal studio to a stage production for public view. The internationally recognized choreographer, dancer, director, and author of The Creative Habit, Twyla Tharp, describes the creative process as starting with a discipline and rigor of attention in a systematic pattern that develops into habit (read more about creativity and habit here). Through countless hours in rehearsal and performance, students practice and develop the creative habit.

Greg Sample and Jennita Russo of Deyo Dances performing in the modern ballet Brasileiro by Barry Goyette. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Greg Sample and Jennita Russo of Deyo Dances performing in the modern ballet Brasileiro by Barry Goyette. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Dance, like so many other contemporary career paths, often consists of sequences of freelance work and requires skills in entrepreneurship to succeed. Many collegiate dance programs such as those at the University of Iowa, Arizona State University, and the North Carolina School for the Arts, offer courses in entrepreneurial skills or require courses in the business department to attain this set of strategies to become successful in the workplace.

During 30,000 hours of teaching dance and movement efficiency and 35 years of teaching in college dance programs, I find people who chose dance as a college major to demonstrate a commitment to practice, focus, discipline, rigor, and reliability. Dance majors acquire skills to accept critical feedback, adjust outcomes through years of daily coaching in technique coursework. The full courses of study in most dance programs require coursework in technical, historical, scientific, and creative perspectives in dance.

Companies such as Google are investigating learning from the skills taught in dance programs.

Arts organizations, corporations, and foundations look for employees with the skills to think innovatively, work diligently towards a common goal, adapt to changing environments, embrace a commitment to the ensemble, push past physical and mental exhaustion, and develop a product in the vision and interest of that company.

Whether a dance major moves forward to contribute to the world through artistic expression or discovers other interests along the way, they are marketable with skills to provide fertile groundwork for a productive work life and provide contribution to the community. In whatever endeavor follows after graduation, the dance major also carries deep skills for employment as well as an understanding of the profound importance of culture, art, and beauty in this world.

Featured image credit: Discipline by Bruno Horwath. Public Domain via Unsplash .

The post Why major in dance? A case for dance as a field of study in universities in 2018 appeared first on OUPblog.

October 25, 2018

Place of the Year 2018 Longlist: vote for your pick

With 2018 nearing an end, we are excited to announce the longlist for the Oxford University Press Place of the Year. From a cave in Chiang Rai, to historical political summits, to young activists marching for their lives, we explored far and wide for our contenders.

Now it’s your time to choose. Learn more about the locations and why they have been nominated for Place of the Year 2018 from our interactive map. Vote for your pick below by 2 November! Have a suggestion that didn’t make our list? Tell us in the comments!

The Place of the Year 2018 will be announced on 4 December.

Place of the Year 2018 Longlist

Featured image credit: nasa-earth-map-night-sky-cities by 14398. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Place of the Year 2018 Longlist: vote for your pick appeared first on OUPblog.

Place of the Year 2018 Longlist: Vote for your pick

With 2018 nearing an end, we are excited to announce the longlist for the Oxford University Press Place of the Year. From a cave in Chiang Rai, to historical political summits, to young activists marching for their lives, we explored far and wide for our contenders.

Now it’s your time to choose. Learn more about the locations and why they have been nominated for Place of the Year 2018 from our interactive map. Vote for your pick below by 2 November! Have a suggestion that didn’t make our list? Tell us in the comments!

The Place of the Year 2018 will be announced on 4 December.

Place of the Year 2018 Longlist

Featured image credit: nasa-earth-map-night-sky-cities by 14398. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Place of the Year 2018 Longlist: Vote for your pick appeared first on OUPblog.

Technology, privacy, and politics [podcast]

All eyes are on the U.S. political landscape heading into the 2018 Midterm Elections in November. With all 435 seats of the House of Representatives and about one-third of Senate spots up for grabs, the next decade of politics lies in the hands of voters. Party control of both the House and the Senate will determine the future of the current presidency.

From fake news to Cambridge Analytica, the 2016 election was the first look at how digital media will influence modern campaigns. The 2018 midterm elections will amplify the effects seen by social media in the last election.

On this episode of The Oxford Comment, host Erin Katie Meehan sits down with experts Kathleen Hall Jamieson, Siva Vaidhyanathan, and Jamie Susskind to gain a better understanding of our current dependence on technology, and the political dangers that come with it.

Featured image credit: Tree Structure Networks by geralt. CC0 via Pixabay .

The post Technology, privacy, and politics [podcast] appeared first on OUPblog.

October 24, 2018

Returning to our daily bread [Part II]

Bread may not be a very old word, but it is old enough, and, whatever its age, its origin has not been discovered. However, the harder the riddle, the more interesting it is to try to solve it. Even if the answer evades us, it does not follow that we have learned nothing along the way. Also, one of the conjectures for which we have insufficient proof may be partially true. Etymology is about the process of discovery: the goal looms in the distance, and who cares if in the end the explorer did not reach it!

Our route begins not with English or German, or Old Icelandic, but with Gothic, a language in which the oldest Germanic consecutive book-length text (parts of the Bible) was recorded in the fourth century. After that date we have almost nothing written by the Goths, for they were assimilated, and the continuation of their language is lost. Yet after their migration from southern Russia, a small group of the once populous tribe remained in Crimea. (Not too long ago, the name of this peninsula needed the definite article, but for some political reasons, it is no longer the Crimea.)

There is an important addition to that story. In 1554, the Flemish scholar and diplomat Ogier Ghislain de Busbecq (1522-1592) reported that during his stay in Crimea he had met the descendants of the Goths there. He drew up a list of eighty-six words, most of which do sound Germanic. No one knows to what extent they are indeed Gothic. Some of them may well be. In any case, the study of Crimean Gothic is a well-developed discipline, even though the problems are many. Of Busbecq’s two informants one was a native speaker of Greek. The other was indeed a Goth, but he was more fluent in Greek than in Gothic. Also, Busbecq wrote down what he, a speaker of Flemish, thought he had heard, and there is no way of knowing how accurate his crude transcriptions were. His work (“four treatises”) came out in Paris in 1589, and one should reckon with misprints. Yet the survival of the Goths in Crimea at least until the end of the 18th century is a fact, and, considering how limited our knowledge of their language is, every bit of information counts.

Thick broth, but not bread. Is this Gothic broe? Image credit: Chicken broth soup by E4024. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Thick broth, but not bread. Is this Gothic broe? Image credit: Chicken broth soup by E4024. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.As noted in the previous post, apparently, the Goths had no cognate of bread, though the relevant forms existed in most Germanic languages. Only hlaifs, related to Old Engl. hlāf (Modern Engl. loaf), turned up. Consequently, if the Crimean Goths acquired a form like, for example, German Brot or Icelandic brauð (ð = Engl. th in the), such a word could be only a borrowing. Be that as it may, Busbecq recorded broe, a word without any consonant after it, and glossed it as panis “bread” (his glosses were given in Latin, and his book was also written in that language). The word did not have two syllables: the letter –e was almost certainly mute. Assuming that bro(e) was heard and recorded accurately, it did probably refer to food, but it may have meant, in addition to some sort of less solid bread (?), also “broth.” In any case, having a late Gothic word like broth or Brot should be taken seriously. Engl. broth (with congeners elsewhere in Old Germanic) has the same root as the verb brew; therefore, broe, if it is not a ghost word, displays a pure root.

Engl. bread developed from what once upon a time must have sounded as brauð-, a form whose root is identical with the Old Icelandic one, and comparison with brew, from breuw-, shows that the last consonant in bread is indeed a suffix. This suffix recurs in past participles, such as brew-ed, bre–d, burn–ed, and a host of others. Is bread indeed brewed? Before I can answer this question, I have to make a digression in a much lighter vein than the previous considerations.

(The images of some of the lexicographers whose names will be mentioned below have not come down to us, but we’ll show you those whom we could find. I wish we had a picture of Busbecq!) Some etymologists tend to be monomaniacs. It was Ernest Weekley (1865-1954), an excellent linguist and the author of an English etymological dictionary and of the best popular books on English words known to me (they appeared in the first decades of the 20th century and are not remembered as well as they deserve) who made this connection. Weekley applied the term monomaniac to the etymologists who attempted to trace all words to one language, usually their own. Such fanatics never stop appearing. But Weekley’s term also fits other benighted “word sleuths.” For instance, some people believe that hundreds of words sprung from a single concept or from a single root, or from three or four roots, while others proclaim that they found one grammatical source of hundreds of words.

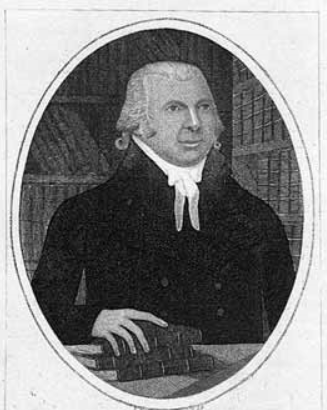

John Horne Tooke. Image credit: John Horne Tooke by Thomas Hardy. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

John Horne Tooke. Image credit: John Horne Tooke by Thomas Hardy. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.In this blog, I have more than once mentioned the famous politician John Horne Tooke (1736-1812). Among other things, he wrote a two-volume work on etymology, which still has some reserved supporters. Tooke insisted that dozens of nouns had been formed from the past participles of verbs. The English verb bray “to crush small, pound” is a 14th century borrowing from French, but this circumstance did not prevent Tooke from suggesting that bread goes back to it (from “the grain crushed small”). Although in view of the chronology this proposal has no merit, the idea of separating -d in bread from the root makes sense. In other cases, Tooke’s etymologies cannot even be discussed.

This is a brood, not a bride; nor a loaf of bread either. Image credit: Female Mallard with ducklings by Brocken Inaglory. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

This is a brood, not a bride; nor a loaf of bread either. Image credit: Female Mallard with ducklings by Brocken Inaglory. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.An 1830 reviewer of Tooke’s work accepted his main idea, but preferred to derive bread from the past participle of Old Engl. brædan (long æ) “to cook, roast, bake” (in principle, “to make warm”). The same idea occurred to Stephen Skinner (1623-1667), the author of one of the earliest etymological dictionaries of English. In Modern German, braten means “to roast”; its English cognate is brood, not bread. Tooke’s etymologies are, in principle, useless, but they were well-known through the efforts of the once famous philologist Charles Richardson (1814-1896), the author of an otherwise excellent English dictionary. It is much to the credit of John Jamieson (1759-1838), the compiler of the inestimable dictionary of the Scottish language, that he resented Tooke’s interpretation of bread.

John Jamieson. Image credit: Rev John Jamieson by John Kay. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

John Jamieson. Image credit: Rev John Jamieson by John Kay. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.We will return to all those suspicious past participles, but first, one more monomaniac, who too has figured in this blog more than once, should be mentioned. Charles Mackay, a noted poet and a god word historian, unfortunately, also wrote an etymological dictionary in which he attempted to show that countless English words are adaptations of the words of Irish Gaelic. The result was, of course,main idea but preferred to derive breadfrom the past participl catastrophic, and no one consults his book today, though it contains useful summaries of his predecessors’ opinions. But, if, guided by a nonsensical principle, a patient lexicographer writes several thousand etymologies, he may once or twice guess well. This, I think, also happened to Mackay, but his derivation of bread from Gaelic brod “the choice of best quality of anything, the best quality of grain, etc.” is a museum exhibit, assuming that a museum of discarded etymologies exists. In a way, I have been working for years to build such a repository, for I believe that the authors of new hypotheses should be aware of everything their predecessors have done, in order to learn from their mistakes and avoid reinventing the wheel.

Charles Mackay. Image credit: Charles Mackay by Charles Rogers. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Charles Mackay. Image credit: Charles Mackay by Charles Rogers. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.This concludes a survey of the early attempts to discover the origin of bread. To what extent later scholars have been more successful will become clear in the next posts.

Featured image credit: Crimea neutral map02 by PANONIAN. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Returning to our daily bread [Part II] appeared first on OUPblog.

On White Fury

y 1807, Simon Taylor’s anger was running hot. This old slaveholder was, by then, approaching seventy, and the abolitionist campaign, which he had vehemently opposed since it first began two decades earlier, was on the brink of a major success. After many years of debate, the parliament in London was poised to put an end to the slave trade.

Image Credit: Am I not a man emblem used during the campaign to abolish slavery, 1788, designed by William Hackwood. Public Domain via

Wikimedia Commons

.

This pitched Taylor into a state of incandescent fury. From his home in the British colony of Jamaica, he had long raged against abolitionists. To him the figurehead of the anti-slave-trade campaign, William Wilberforce, was a “hell-begotten imp”, spreading ‘infernal nonsense’. Taylor had never been able to understand Wilberforce. He continually expressed outrage that such a man had misguidedly taken up the interests of “negroes” against those of white colonial slaveholders. “Am I not a man and a brother?” was the slogan of the abolition movement—accompanied by the image of a kneeling African, begging for help. It was a message that grabbed imaginations and changed perceptions. And, for a man like Taylor—whose wealth was based on buying, selling, and exploiting enslaved Africans—it was nothing less than a disaster.

Taylor’s view of empire was built around the principles of white supremacy and white solidarity. To men like him, the only people who could be considered “natural born subjects” of the British Empire, and therefore deserving of its care and protection, were whites; he considered black people merely as items of property. He struggled to understand how any truly patriotic Briton could see things differently. How could the British public and parliament fail to see that colonial slaveholders were the most precious and useful inhabitants of the empire? How could they prioritise the welfare of black slaves over the interests of such fellow white Britons?

Taylor was born in Jamaica in 1740, into an empire that seemed to belong to wealthy Caribbean slaveholders. The eldest son of a Kingston merchant, he was sent to school at Eton before returning to Jamaica in 1760, taking over the family firm, and branching out into the sugar business. He was investing in the most lucrative and dynamic part of the eighteenth-century British imperial economy. Sugar planters were notoriously wealthy, Caribbean sugar was Britain’s most valuable overseas import, and the enslaved Africans whose labour made all of this possible were treated as a disposable resource. Taylor bought and developed three huge plantations—which, like all British sugar estates, were worked by hundreds of enslaved workers, imported to the Caribbean colonies from West Africa via the transatlantic slave trade—becoming one of the richest and most influential British sugar planters of his generation.

Taylor was middle-aged by the time that the abolition movement emerged. At first, he saw it as a naïve and sentimental outpouring of emotion that would soon wither, once sensible men of business exposed its absurdity. But by the time he entered his sixties, abolitionism (coupled with revolutionary uprisings by enslaved people throughout the Caribbean) had forced him to accept that the world of plantation slavery that he had worked all his life to sustain was more vulnerable than at any time he could remember. “I am glad I am an old man”, he grumbled in a letter to an old friend, confessing that he was “really sick both in mind & body at scenes I foresee”.

Soon after, on receiving the long-anticipated news that parliament had reached its momentous decision to put an end the slave trade, his reaction was predictable. He felt “really crazy”—”lost in astonishment and amazement at the phrensy which has seized the British nation”. Of course, parliament had only abolished the trade in slaves across the Atlantic. (By the time concrete plans were laid to end slavery itself, Taylor had been dead for two decades.) But the abolition of the slave trade in 1807 was, nonetheless, a major political setback for British slaveholders that dealt a significant blow the wider system of slavery. It might be tempting, then, to view Taylor’s rage as the behaviour of a man failing to come to terms with irreversible defeat. Perhaps, then, we could take comfort in the knowledge that Taylor and the world of slavery that he built with such self-confident conviction and defended with such venom are now safely in the past. That, however, would be unjustifiably complacent.

When we look at it carefully, we see that Taylor was angry not because he believed that defeat was inevitable but because he believed that it could, and should, be averted. And privileged, vocal, outraged men like him can be influential even when major decisions go against them. In the political wrangles over the dismantling of the British slave system, slaveholders won large concessions and retained significant privileges. What is more, the kind of angry reaction to change embodied by a man like Taylor is not simply a thing of the past. Again and again between his times and ours—through unfinished struggles over emancipation, decolonization, and civil rights—those who have grown up as beneficiaries of white privilege have responded angrily to pressure for equality, increased diversity, and even the most basic of reforms, as though they were types of oppression. Again and again between his times and ours—through unfinished struggles over emancipation, decolonization, and civil rights—those who have grown up as beneficiaries of white privilege have responded to pressure for equality, increased diversity, and even the most basic of reforms, as though they were types of oppression. Institutionalised racism rooted in colonialism and slavery proves stubborn in the face of reform, partly because when old white privileges are challenged, indignant white fury—of the sort that Taylor luridly expressed in letter after letter—is rarely far behind.

Featured image credit: “Caffeine” by Bruno Scramgnon. CC0 via Pexels.

The post On White Fury appeared first on OUPblog.

It Keeps Me Seeking

ometimes spouses will look back on the time of their getting to know one another and say, half-jokingly, that on a given occasion one was putting the other to the test. A person keen on hill-walking might invite their loved-one on an expedition in the Lake District; they want to know if their friend will enjoy it and thus “pass”. One keen on theatre might invite a loved-one to a play; they want to know if their friend will appreciate it and thus “pass”. Such “tests” are, up to a point, a natural part of any developing friendship, but you can’t spend your whole life that way. If it is just test after test then the friendship is not developing, and indeed is liable to drain away. Eventually friends come to know one another well enough that they wish to develop the relationship by other means: they wish to achieve something together. This “knowing” is human “knowing” —the French connaître and the German kennen, as opposed to savoir and wissen. It does not mean the absence of uncertainty; it means the presence of trust.

All this carries over quite well (not perfectly well, but quite well) to what is going on when some kinds of religious talk makes reference to “knowing” God. To “know” God in this sense does not imply the absence of uncertainty; it does imply the decision to keep going, and to seek to achieve something worthwhile.

But someone will ask, “but does God even exist?”

Asking “Does God exist?” is like asking “Are perfect numbers composite?” Anyone asking the question has not understood the terms of discussion.

One can answer “yes” to the second question without much hesitation, because it is easy to come to agreement on the standard mathematical definition of a ‘perfect’ number (one which is the sum of its proper divisors). For the first question, one might reply, “the very fact that you need to ask shows that you don’t yet have a very good sense for theological talk—for how it works, and what sort of truth-speaking is going on; you need perhaps to learn to ask a different sort of question. You might ask, for example, “what is the nature of that which can honourably call upon my allegiance, and can liberate my fellows?” That is perhaps a more helpful question.”

Jascha Heifetz. See also the poem “The Musician” by R.S. Thomas. Image credit: ‘Jascha Heifetz – Carnegie Hall 1947 (02) wmplayer 2013-04-16’ from Wikimedia Commons.

The previous paragraph risks being patronising, and I apologise if it is; my aim in this piece is not really to advise anyone, but simply to alert them to the fact that within the very diverse (and confusing) realm of religious expression, a great deal of care is needed to extricate oneself from one’s own presuppositions and the presuppositions of the surrounding culture. If a word such as “God” is being used to mean anything less than “that which is our true context and rightly commands our allegiance” then there is, at the very least, the risk that someone has embarked on the rather useless and unedifying programme of defining their own concept of god and then appealing to that concept for enlightenment (or the lack of it).

But this is not to offer a sleight-of-hand, a sneaky way to win an argument by coming up with a definition that I like. It is rather to re-orient the discussion. To turn it from an inward-focussed debate about things we think we know, to an outward-focussed journey and a desire to learn. Now we can exchange our insights not as final conclusions but as ongoing aids. We can welcome every avenue of learning: everything that science, and the scientific method can offer, for example, and also the most thorough and honest historical enquiry. It becomes obvious that the question, “Is Christianity compatible with evolution?” is sort of a crazy question, like asking “Is learning the violin compatible with the fact that trees grow from seeds?”

We can also feel free to assert a sense that the natural world does not contain all its truth inside itself, but, like a poem or a symphony, is also a pointer to truths larger than itself. We can embrace this sense and feel free to explore. This does not mean freedom to invoke shoddy intellectual work or arguments that do not hold water. Better to admit we don’t know than to invoke a worthless argument. Uncertainty is ok, it is a partner on any journey of discovery.

But finally, we are going to need to decide, at some stage, whether our relation to whatever can rightly command our allegiance is an exercise of personal choice which can be withdrawn or redirected at any moment, or whether another mode of relating may become more fruitful.

Featured image credit: ‘Keswick Panorama – Oct 2009’ by Diliff. CC-BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post It Keeps Me Seeking appeared first on OUPblog.

October 23, 2018

The language of victory: 8 ancient phrases used by Emperor Justinian

Between the fall of the western Roman Empire in the fifth century and the collapse of the east in the seventh, the remarkable era of the Emperor Justinian (527 – 568) dominated the Mediterranean region. Famous for his conquests in Italy and North Africa and for the creation of stunning monuments such as the Hagia Sophia, his reign was also marked by global religious conflict within the Christian world.

When writing about the Justinian era, historian Peter Heather chooses to use both Greek and Latin terminology as a way to bring Justinian’s legacy to life. We’ve listed out some of the terms that help detail the political and martial history of Emperor Justinian.

Nika— win or conquer (Greek): The empire that Justinian inherited in 527 AD began as Constantine’s dream in 312 AD. Constantine was advised in a dream, on the eve of battle, to mark the heavenly sign of God on the shields of his soldiers, and they went on to score a resounding victory. Thanks to Constantine’s dream, nika became the catchphrase of Rome’s armies.

Civilitas— civilization (Latin): The Roman imperial state claimed to be a superior form of political organization—not just superior to existing governments, but superior to any governments that might ever exist. Combining classical Greek philosophy and imperialism, the Romans placed heated importance on civilitas, civilization, as it signified an order of social organization that allowed human beings to become the fully rational beings their divine Creator wished them to be.

A mosaic of Justinian I by Meister von San Vitale in Ravenna. Credit: “Meister von San Vitale in Ravenna.” Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

A mosaic of Justinian I by Meister von San Vitale in Ravenna. Credit: “Meister von San Vitale in Ravenna.” Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Nomos empsychos—law incarnate (Greek): From the late third century onwards, Roman emperors dominated lawmaking in the Roman world and were themselves customarily viewed as law incarnate. They could make (and sometimes break) laws as they wished, as long as they could present what they were doing as supportive of the ideals of rational civilization.

Bucellarii—personal soldiers (Latin): By the time of Justinian, field army generals all seemed to have substantial forces of officers and soldiers who were recruited by them personally and tended to follow their generals on campaigns even to far-flung corners of the Mediterranean. Sixth century bucellarii swore an allegiance not only to their general but to their emperor as well and were often supported in part by state funds.

Denarii—silver coins which were used to pay soldiers (Latin): The third century was marked by financial upheaval in Rome, particularly problems regarding military pay. Progressively, Roman imperial administrators debased the denarii, cutting full-value silver coins with base metals to generate the need amount of money to pay soldiers. It took about a month for everyone to realize that the new coins were worth less, though, by which time many of the soldiers would have spent their pay.

Silentarius—usher (Latin): The standard translation of silentarius, usher, gets nowhere near its importance. A long-serving palace insider, the silentarius Anastasius was voted for by Empress Augusta to be the next emperor in 491 AD. He fulfilled the public’s major requirements: he was orthodox, and he was Roman.

Henotikon—act of union (Greek): With the Eastern Church ever more bitterly divided, Byzantine Emperor Zeno drew up a peacekeeping initiative that successfully restored peace to the Eastern Church by stating that the faith had been satisfactorily defined once and for all in the fourth century at the Councils of Nicaea (325) and Constantinople (382).

Auxilia…divino—by Divine help (Latin): Around 500 AD, Theoderic the Great wrote a famous letter to Emperor Anastasius, claiming that he, Theoderic, “by Divine help learned in Your Republic the art of governing Romans with equity.” This letter is often cited to show barbarian deference to Roman ideology. Read as a whole, however, Theoderic asserted that his ability to govern Italy as a fully-fledged Roman ruler was not the product of observation and attention to Roman rule, but divine intervention.

Featured image credit: “Hocgracili” by Alatius. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The language of victory: 8 ancient phrases used by Emperor Justinian appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers