Oxford University Press's Blog, page 209

December 12, 2018

Sowing one’s etymological oats

For many years I have been studying not only the derivation and history of words but also the origin of idioms. No Indo-European forms there, no incompatible vowels, not consonant shifts, but the problems are equally tough. Sometimes it suffices to discover the source of an enigmatic word, in order to understand the phrase. Thus, once we find out what kibosh means, we can decipher the phrase to put the kibosh on. As we have seen, a whole book was needed to approach the truth. Or what is dander in getting one’s dander up? No less enigmatic than kibosh and dander is Jack Robinson. Something happens before you can say Jack Robinson. Who was this gentleman, and how did he become a unit of speed or an ideal of brevity? Or why do we say to go to hell in a handbasket? Every word is clear, but the whole makes little sense.

The origin of the idiom to sow one’s wild oats has bothered me since my student days. I think it should mean the opposite of what it does. One sows wild, uncultivated oats, that is, weeds. It should mean “to indulge in vice.” And it does, but not quite, for the phrase, I believe, is used only with reference to the past, that is, with the implication that the “sower” (always a young male) who once indulged in debauchery and promiscuity has now settled down; he is not harvesting anything bad. It is not like cutting the mustard: you cut it and achieve your goal. The profligate’s oats never germinate, and the seedlings are forgotten. One probably cannot say: “Stop sowing your wild oats” or “You have been sowing your wild oats for years; get a job, marry, and settle down.” Idioms are in general averse to such transformations (for instance, one will hardly ever hear something like he will soon go to hell in a handbasket or why not cut the mustard next time?), but I still wonder why this phrase is always used in the past.

Let us hope that he is not sowing wild oats. Image credit: Farmer sowing seeds – panoramio by tormentor4555. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Let us hope that he is not sowing wild oats. Image credit: Farmer sowing seeds – panoramio by tormentor4555. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.In my excellent database of idioms, only once has an explanation turned up. A correspondent to the ever-helpful Notes and Queries wrote in 1852: “In Kent, if a person has been talking at random, it is not uncommon to hear it said ‘you are talking havers’ or folly. Now I find in an old dictionary that the word havers means oats; and therefore I conclude, that the phrase to sow one’s wild oats means nothing more than to sow folly’.” Today we don’t need an old dictionary to discover that the old Germanic name for “oat” has been preserved in German Hafer, Dutch haver, and the Scandinavian noun havre. One should not suggest that Danish, Norwegian, and Swedish havre is an early borrowing from West Germanic, for hafri did turn up in Old Icelandic, though indeed only once, but in poetry, and ancient poetry tends to retain native words better than prose.

The enigmatic word haver reached even Kent. Image credit: Kent UK locator map 2010 by Nilfanion. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The enigmatic word haver reached even Kent. Image credit: Kent UK locator map 2010 by Nilfanion. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Now, haver “folly” is a fairly well-known northern word, and I was surprised to find it in Kent. Its origin is unknown. To connect it with oats seems rash. Haver “oats” did make its way into Middle English from Norse but, except for northern havercake and haverbread, left no trace in the modern language if we disregard haversack “canvas bag.” This bag was slung over the shoulder and originally contained a soldier’s day rations. Amazingly, German Habersack “a bag in which cavalry carried the oats for their horses” made its way into French (soldiers’ words travel easily from one warring side to the other), and English borrowed it in the eighteenth century.

To sow one’s wild oats bears the stamp of a so-called familiar quotation, a pithy saying from Latin or some other famous source, but I am not aware of such a source, and, as far as I can judge, no one is. In English, the idiom appeared in the sixteenth century and denoted a useless occupation, but frittering away one’s time and being famous for fast living are different things. The reference known to us is to vicious, rather than unprofitable, behavior. The time of this idiom’s emergence is a bit unexpected. Not everybody may realize that colorful idioms in the modern European languages are late. The only exceptions are translated quotations from the Bible and Classics.

While reading Old English, if we understand every word and the grammar of the sentence, we understand everything. Combinations like kick the bucket, kick up one’s toes, or go west/south, all of them meaning “to die” (and there is a whole thesaurus of expressions of the same type) emerged in great quantities during and after the Renaissance. Our oldest authors were fond of similes but had not yet learned to use metaphors. The sixteenth century is a rather early time for the coining of a phrase like to sow one’s oats. That is why I suspected that we are dealing with a translated phrase, and it is irritating that the source has not been found. Yet there is another approach to our idiom, though with it we may also come up short.

Our best books have nothing to say about the origin of the phrase to sow one’s wild oats. For example, Linda and Roger Flavell explain in the Dictionary of Idioms and their Origins: “The allusion is to the young and impulsive lad who sows wild seed on good ground where a mature and experienced man would have sown fine seed. Like the weeds they are, wild oats take hold rapidly but are extremely hard to get rid of, rather like the consequences of young folly.”

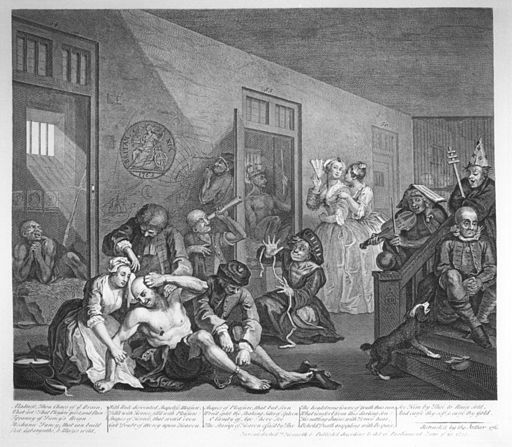

A famous rake sowing wild oats. Image credit: The Rake’s Progress 8 by William Hogarth. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

A famous rake sowing wild oats. Image credit: The Rake’s Progress 8 by William Hogarth. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Very true, but all the questions remain. Has anyone ever indulged in sowing wild oats? The image, one supposes, should have some foundation in reality. Nowadays, sowing one’s wild oats most often means “having sexual intercourse with many women.” In British English, oats is slang for “sperm”; hence the universally understood reference to promiscuity. That is of course the reason why, when today one uses the idiom to sow one’s wild oats, people think of a young male hopping from one contact to another. I wonder what the order of the linguistic events was and whether oats, unbeknownst to us, meant “seed” and “sperm” for centuries, but surfaced only in our living memory. Slang may remain dormant for a long time without appearing in print, though oats is a rather poor synonym for seed. To feel one’s oats means “to be confident.” Is this too an allusion to a man’s triumphant virility? The phrase is allegedly an Americanism. Finally, oats, we hear, has come to denote “sexual gratification”; this appears to be another word from overseas.

The answer about the origin of our idiom may be close at hand, but some link is missing, and we have to confess that the source remains unknown. Samuel Johnson was talking havers when he said that oats is a grain which in England is generally given to horses, but in Scotland supports the people. Oats and wild oats have come back to haunt us. Rootless words and idioms—this is our etymological oatmeal, which supports neither people nor horses.

All this I was going to use as a preface to the last part of my plant series (the etymology of the word oat), but decided to divide the story into two parts. I’ll regale you with the second part next week. See special essays on get one’s dander up, put the kibosh on, and cut the mustard.

Feature image credit: Avena fatua by Matt Lavin. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Sowing one’s etymological oats appeared first on OUPblog.

How does the Supreme Court decide what the Constitution means?

The US Constitution declares itself to be “the supreme law of the land.” Unfortunately, the meaning of the constitutional text is not always clear. Consider the abortion case Roe v. Wade. How did the US Supreme Court conclude that the Constitution gives a woman an essentially unconstrained choice to have an abortion in the first trimester of her pregnancy but that it also allows the state to regulate or prohibit abortion as the pregnancy progresses?

Everyone—the president, state legislators, and private citizens–can have their own opinion on what the constitution means. But since the 1803 decision in Marbury v. Madison, the Supreme Court has had the last word on constitutional interpretation. How does the Court decide what the Constitution means?

Ultimately the Supreme Court is constrained by political realities. If the Court tried to direct Congress to spend money on highways or to force people to go to a Catholic church, the resulting uproar would drown out the words of the Court’s opinions.

The major struggle over theories of constitutional interpretation is between those judges and scholars who believe that the Constitution should be narrowly interpreted only according to the intent of the framers or the understanding of its provisions at the time of adoption and those who assert that we have to look beyond those intentions and understandings. The former theory, that the Constitution has a “changeless nature and meaning,” as Justice David Brewer wrote (South Carolina v. United States, 1905) is known as originalism or interpretivism; the latter is known as nonoriginalism and is sometimes described as the idea of a living Constitution.

The concept of originalism as a solid source of constitutional law is as attractive as the idea of a text with plain meaning, but nonoriginalist judges and scholars have identified problems with the concept. There is an initial problem of our ability to render a historical judgment about original intent or understanding. Reference to “the intention of the framers” suggests that there existed a definable group of framers and that we can determine their intentions with a high degree of certainty. But who are the framers?

The original Constitution was drafted, negotiated, and voted on in a convention composed of delegates from different states with different points of view and then ratified by the members of thirteen state legislatures and conventions. Whose intent are we to focus on: the drafters of the provision at issue, others who participated in the debate at the convention or in the Congress, or members of the ratifying legislatures?

The difficulties of ascertaining historical intention have led some originalists to shift focus from the intention of the framers to the general understanding of a constitutional provision at the time of its enactment, what Justice Scalia described as “the intent that a reasonable person would gather from the text of the law.” The search for original understanding, therefore, presumes that we can comprehend the framers’ world and apply that comprehension to our own world. But nonoriginalists point out the difficulty of achieving that comprehension.

What is the nature of the Constitution, why does it command obedience, and what is the role of the Court in interpreting it?

Originalism presumes that historical intent is a fact, like a physical artifact waiting to be unearthed, but it is often hard to dig up the truth about an event two hundred years in the past. When the authors and ratifiers of the First Amendment thought of freedom of speech and freedom of press, they could only have in mind some idea of freedom of speech and press—literally—because speaking and printing were the only forms of communication available. How do we translate that understanding to the regulation of, for example, readily accessible pornography on the Internet or pervasive commercial advertising on television?

In the end, the choice between originalism and nonoriginalism and among their many variations is a choice based on political theory: What is the nature of the Constitution, why does it command obedience, and what is the role of the Court in interpreting it? These are difficult questions to resolve, and history does not answer them for us. Indeed, constitutional historians argue that the framers themselves were not originalists. Lawyers and statesmen in the late eighteenth century did not hold a conception of fundamental law as the positive enactment of a legislative body, such as a constitutional convention, whose understanding in enacting the law should guide its interpretation.

Does this leave constitutional interpretation at the point where we simply say that it’s all up to the justices’ points of view and that they can read into the Constitution their own political views and personal preferences? Yes and no. “Yes,” in the sense that no plain meaning of the text, historical evidence, or objective principles determine their decisions. And “no,” in the sense that a justice is not completely free to reach any decision on any basis he or she wants.

This brings us back to the idea that constitutional law is as much a language and a process as a body of rules and rights. The words of the Constitution and the ways it has been understood, interpreted, and argued about inside and outside the courts provide the language the justices must use in interpreting and applying the Constitution.

When it is taken seriously and pursued in good faith, constitutional interpretation becomes a model of principled debate on important social issues. It can be conducted at one level removed from immediate political controversies, making it easier to consider consequences, construct principles, and analogize to other situations—the kinds of things the legal process is best at.

Too often, of course, constitutional debate is not carried on at this level. Instead, it becomes one more vehicle for the expression of preconceived beliefs. Because the Constitution is subject to varying interpretations, justices and others can select the interpretation that best fits the conclusion they wish to reach without engaging in a serious process of interpretation.

Featured image credit: Constitution 4th of July by wynpnt via Pixabay.

The post How does the Supreme Court decide what the Constitution means? appeared first on OUPblog.

December 11, 2018

How to face the moral challenges of organizations from the inside

When you enter your workplace on Monday morning, is it you who enters it, or is it someone else? A mask, a role you play in order to get through the workday? And does that matter? Many people would say it is a matter of choice, or perhaps of aesthetic sensibilities, whether or not you want to play a role in your job, or be true your own self. But arguably, there is more to it: it is not only exhausting and potentially psychologically damaging if employees have to pretend to be someone else for eight or more hours a day. There are also tricky moral questions: if, as a private individual, I am committed to certain values and principles, should I simply forget about them when I go to work?

For example, many of us would like to see our economic systems to shift onto a more sustainable, climate-friendly path, and see it as a moral duty to contribute to such a shift. But there is often a gap between this commitment and our behavior. This gap can occur in our private lives, for example in our consumption behavior, as when we are far more oblivious about the CO2 emissions of our travels than we know we should be. But often this gap is even greater in our jobs. For it is here that our energies, our skills, and our knowledge are being put to use – while our choices are often much more constrained.

Imagine a world in which all individuals in their work lives, from security guards to nurses to accountants to managers to politicians, would use their specific skills and local knowledge for contributing to the reduction of CO2 emissions. Instead of realizing such a world, we are entangled in a system in which many of us are complicit with practices that we do not morally endorse. But many of us feel we have to play along – because we depend on our jobs, and these jobs are part of this system. Employment takes place in complex organizations that cut out different roles and stitch them together by rules and hierarchies; often, they are driven by market pressures and market ideologies. Together, they form a system that seems beyond anyone’s control.

What does it mean to face the moral challenges of organizations from the inside? This area has been largely neglected by philosophers, because of the divide between moral philosophy – which looks at the ethical choices of single individuals – and political philosophy – which asks what the institutions of a just society would be. Considering how much this matters for our lives, this has received relatively little attention. In order to understand its specific challenges, I read empirical literature on organizations, but also interviewed practitioners about their experiences. Doing so proved a fruitful approach for grasping the nuances of these moral challenges – including the vexing question of how you can remain true to your moral self when acting from within an organizational role.

…how should organizations be embedded in the broader institutional framework of a society, such that the pressures on them do not make moral agency impossible?

Some of these issues can be addressed within organizations. Responsible leaders allow for an atmosphere of trust in which knowledge can be openly shared, criticisms can be raised, and debates lead to constructive solutions. Organizational rules, for example, do not have to be treated as an iron cage that employees are supposed to follow blindly – individuals can also be encouraged to use their own sense of judgment and to discuss critical cases with colleagues. The latter can be crucial for preventing the kinds of moral wrongs that can happen when a general rule is applied to an atypical case.

But in the end, organizations can only do so much when they are driven by market pressures and when the expectations of society do not support responsible organizational practices. Hence, questions of political philosophy arise: how should organizations be embedded in the broader institutional framework of a society, such that the pressures on them do not make moral agency impossible?

Democratic societies can take steps, through the legislative process, that either support or undermine moral agency within the system.

For example, what legal protection do employees enjoy? Who owns the information that one needs to make well-informed decisions about morally grey areas? Among the strategies I suggest for reclaiming the system, i.e. bringing organizational structures back into the scope defined by our shared moral norms, a key concern is the introduction of more participatory and democratic structures into organizations, which create counter-power and require accountability from those with organizational power. One way of doing so is to support – e.g. through tax reductions – cooperatives and other forms of companies in which employees have more rights. Such non-traditional companies are at the forefront of attempts to create a more just and more sustainable economic system.

For addressing urgent moral issues, such as the fight against global poverty, the reduction of carbon emissions, and not least for creating organizations that allow us to remain true to ourselves in our jobs, this might be our best bet!

Featured image credit: Taller than the Trees by Sean Pollock. Public Domain via Unsplash.

The post How to face the moral challenges of organizations from the inside appeared first on OUPblog.

Donuts, dogs, and de-stressing: library programs to ease student stress

For most students, December is the most wonderful (read: stressful) time of the year. With final projects and exams nearing, students and librarians alike are gearing up for the anxiety-filled, coffee-fuelled days and nights ahead.

To help prepare their patrons for the long hours of studying, writing, and prepping, librarians have created anti-procrastination, stress-relieving events that seek to ease the pain of the finals push. We chatted with librarians from the United States, United Kingdom, and Canada about their specific programs, and the impact they have on students’ health and well-being during this tense time:

“Night of a Thousand Donuts,” Michigan State University Libraries; Michigan, US:

During the “Night of a Thousand Donuts,” the Michigan State University Library serves almost 2,000 donuts, 50 gallons of coffee, orange juice, and healthy snacks such as oranges and almonds at the Main Library and the Business Library. They place the food and drinks on book trucks and pass them around the building, as well as offer some in a conference room on the 4th floor of the library. This event takes about 30 librarians and staff to prepare, and is their most popular event; they give everything away in a little over an hour.

Image credit: “Michigan State University tweet”. Used with permission from Holly Flynn.

Image credit: “Michigan State University tweet”. Used with permission from Holly Flynn.For this event, the librarians snap photos and put them on their three social media channels – Facebook, Twitter and Instagram – and the posts quickly become their most popular social media posts of the year. The program is offered to all students – around 50,000 individuals – every finals week (twice a year), thanks to a generous donation from Michigan State University Federal Credit Union.

Feedback on the program has been overwhelmingly positive:

“When we first started doing this, they asked us who we are and why we were doing this,” said Holly Flynn, Coordinator of Outreach and Engagement. “They seemed pretty amazed that librarians noticed them at all and wanted to help.”

For more information on this and other events the library offers, check out this blog post written by Holly Flynn.

“Dog De-Stress Day,” Staffordshire University Library; Stoke-on-Trent, UK:

Image credit: “Staffordshire Library Therapy Dog Event.” Used with permission from the Staffordshire Library.

Image credit: “Staffordshire Library Therapy Dog Event.” Used with permission from the Staffordshire Library.In April each year, the Staffordshire University Library has regular dog days where guide dogs come in and let students spend time with them. They have a library dog called Willow, who does the same. Dog De-Stress Day is held twice a year on the Stoke-on-Trent campus to help students relax and unwind.

The program is offered to all current students, and runs for a total of six weeks. It benefits not only the students and dogs, but also the owners of the guide dogs, who enjoy sharing their furry companion with others.

In addition to this program, they also have a Children’s library with children’s books which the students are able to access for a moment of light-heartedness. This year, they are adding mindfulness books and games, and have linked up with the Sports Centre to offer physical well-being activities that will include activity boxes in the library with hula hoops and skipping ropes for students to use.

For more information about the “Dog De-Stress Day,” check out this article.

“Long Night Against Procrastination,” Loyola Marymount University; California, US:

On the night before the start of finals, the William H. Hannon Library at Loyola Marymount University hosts its “Long Night Against Procrastination” event. This event is a structured study session that encourages students to focus for an extended period of time to complete a project. The library publicizes the event across campus and reaches out to specific entities, such as the writing center, the honors program, and more, to get 50 to 60 students to sign up for the event.

Image credit: “Long Night Against Procrastination Event.” Used with permission from the Loyola Marymount University Library.

Image credit: “Long Night Against Procrastination Event.” Used with permission from the Loyola Marymount University Library.It takes place on the third floor of the library from 8:00-pm to midnight. At the start of the event, students receive a goody bag and information about the schedule and resources available during the event. After pledging on a whiteboard what they hope to accomplish during the event, the students get to work.

Image credit: “Long Night Against Procrastination Event”. Used with permission from the Loyola Marymount University Library.

Image credit: “Long Night Against Procrastination Event”. Used with permission from the Loyola Marymount University Library.During the event, librarians and tutors are available to assist students with their projects if needed. Students take scheduled, structured breaks throughout the event, which include things such as a yoga stretch break, a few minutes of watching cute videos, and a group popping of bubble wrap. Pizza is also served halfway through the event.

The library has found “Long Night Against Procrastination” to be successful, with both a good turnout for the event and positive feedback from students afterwards. In addition to providing study resources, free food, and giveaways, the event provides an opportunity for co-studying with other students that encourages attendees to stay focused and be productive.

For more information on this program read this longer piece written by John Jackson, Head of Outreach & Communications at the William H. Hannon Library.

“Library De-stress Week,” University of Toronto; Toronto, Canada:

Library De-stress Week started at The University of Toronto Mississauga Library in December 2012. On average, they have 1,000 participants in events, which include therapy dog visits, mini-massage appointments, board games, video games, henna and tattoos, as well as various creative arts and crafts projects (scratch arts, DIY gift bags, and more).

Nelly Cancilla, the Communications and Liaison Librarian, helps run the program, and said it is highly effective for relieving stress, and students look forward to the events as a way to break up their studying with entertaining and positive activities. They see their role in the library as supporting the needs of the community and student stress and mental health is an issue that they see as a priority particularly during the exam period.

Explore their full calendar of de-stress events on their website.

Featured image credit: “Long Night Against Procrastination Event” photo, used with permission from the Loyola Marymount University Library.

The post Donuts, dogs, and de-stressing: library programs to ease student stress appeared first on OUPblog.

December 10, 2018

How video may influence juror decision-making for police defendants

On 20 October, 2014, Chicago Police Officer Jason Van Dyke shot and killed Laquan McDonald, a 17-year-old black boy. In his initial police report, Van Dyke indicated that McDonald had been walking down the street holding a knife and behaving erratically, and eventually McDonald pointed the knife toward Van Dyke, advancing at him. Van Dyke claimed that he shot McDonald in self-defense, although he did not report the number of shots he fired. Yet, video from a camera mounted on a police cruiser revealed that McDonald was not approaching but rather walking away from Van Dyke when Van Dyke began shooting. Moreover, Van Dyke continued to shoot McDonald after he was lying on the ground. Van Dyke emptied his firearm, shooting McDonald a total of 16 times. The Cook County coroner determined that nine of the 16 bullets entered McDonald’s back, leading him to rule McDonald’s death a homicide.

It took 13 months for the dash-cam video showing Van Dyke killing McDonald to be released to the public, but it is probably no coincidence that Van Dyke was charged with first-degree murder on the same day. Even though it was the first time in almost 35 years that a Chicago police officer was charged with murder for a death caused while on duty, marking a significant turnaround in the handling of such cases, the release of the video precipitated public outrage and a series of protests over the course of several years in Chicago.

Indeed, instances of police use of excessive or deadly force can now be captured not only by police dash-cams and body-cams but also by smartphone and surveillance cameras. As a result of video technology proliferation, many instances of police-inflicted injury and death have been video recorded, providing documentary evidence that a disproportionate number of victims are racial and ethnic minorities (e.g., the 15-year-old girl who was forced onto her stomach while an officer put his knees on her back in McKinney, Texas; Eric Garner who died as the result of an illegal chokehold in New York City; Walter Scott who was unarmed and shot in the back in Charleston, South Carolina, etc.). In recent years, these videos have become increasingly available to the public and widely disseminated, fueling the launch of the Black Lives Matter movement demanding justice for minority victims of police violence. Yet, little research has explored how video is impacting juries when police actually go to trial as defendants.

Image credit: person holding black smartphone recording a video by chuttersnap. CC0 via Unsplash.

Image credit: person holding black smartphone recording a video by chuttersnap. CC0 via Unsplash.Cases like the murder of Laquan McDonald’s raise a variety of issues relevant to understanding jury decision making in the trials of police defendants. First, the mass protests launched in response to the video of his murder point to a growing distrust of the police by the public. In general, exposure to video footage of police use of excessive or deadly force might negatively affect public perceptions of police and court legitimacy. This has implications for understanding the attitudes of citizens in the jury pool, more of whom are likely to be skeptical of police now than in the past.

Second, police officers’ defense attorneys are likely to attempt to filter potential jurors who are distrustful of police out of the jury pool. Because minorities trust police less and perceive them as less legitimate relative to white people, such jury selection practices are likely to result in the systematic elimination of black jurors. Of course, the counterpoint is that prosecuting attorneys are likely to seek to dismiss white jurors who evince higher levels of trust in the police, too. The problem is that defense attorneys will be more successful in their efforts because black people are underrepresented in jury pools so there are fewer of them to eliminate to begin with. As a consequence, juries in cases involving police defendants may be unrepresentative of the populations from which they are drawn and of those victimized by the crimes at issue.

Third, because a video of a specific incidence of police violence may be circulated widely before the officer’s trial begins, it may be difficult to identify impartial jurors who either have not been exposed to the video or resulting media coverage, or at least remain unbiased by their exposure to such pretrial publicity. Moreover, even after jurors are seated in a trial, it is important to ensure they are not exposed to such publicity while the trial is in progress—an increasing challenge in the age of Google and Twitter.

Fourth, the proliferation of video technology in recent years also has increased the likelihood that video evidence of injurious or deadly yet contested police interactions will be introduced during trial, directly affecting jurors’ case decisions. Although jurors have been found to perceive police witnesses as more credible than lay witnesses, when police testimony is contradicted by video evidence, jurors might be more likely to believe what they see with their own eyes. Jurors generally find video evidence to be particularly reliable and convincing, in part, because they consider video to be a reflection of objective reality. Indeed, one juror in Van Dyke’s case—the only black juror—indicated that Officer Van Dyke should never have testified because he came off as not believable.

It has long been recognized that advances in technology can be an impetus for changes in laws and policy. As Laquan McDonald’s murder and others like it illustrate, technological advances also have the potential to shape jurors’ attitudes and decision-making.

On 5 October, 2018, nearly four years after Laquan McDonald’s death, a jury found Van Dyke guilty of second-degree murder and 16 counts of aggravated battery. Yet, Van Dyke’s case is a rare instance in which a police officer was tried and convicted of murder committed while on duty. For the most part, grand jury outcomes favor police defendants, and even when a police officer does face trial, police officers tend to maintain secrecy and refuse to testify against their colleagues, which serves to protect police defendants who may have abused their power. Much more research is needed to understand grand jury decision making and the impact of the “blue wall of silence” in this context. Still, it seems reasonable to conclude that the fact that McDonald’s murder was captured on video and disseminated broadly played a role in Van Dyke’s conviction—a conviction that bucked historical patterns and might reflect the beginnings of a new trend toward police accountability.

Featured image credit: Laughing photo by Spenser. CC0 via Unsplash.

The post How video may influence juror decision-making for police defendants appeared first on OUPblog.

The past, present, and future of MELUS: Multi-Ethnic Literature of the United States

Gary Totten is professor and chair of the department of English at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. He also serves as Editor-in-Chief of the journal MELUS: Multi-Ethnic Literature of the United States. In this interview session, we ask Gary Totten a few questions to learn more about his work, and the coming work for the field and the journal.

Oxford University Press: Can you tell us a bit about the history of the Multi-Ethnic Literature of the United States journal?

Gary Totten: The Society for the Study of the Multi-Ethnic Literature of the United States was organized as a scholarly society in 1973, in response to the lack of representation of papers or panels on US multi-ethnic literature at the Modern Language Association annual convention. A year later, the journal was created under the editorship of Katharine Newman, who was also responsible for organizing the annual conferences of the society, which we continue to enjoy. Joseph Skerrett, Jr. at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst took over the editorship after Katharine had served for twelve years. Under his leadership, the journal’s scope expanded and its reputation increased. He often emphasized in the journal scholarship taking a cross-cultural or interethnic approach, and he was a terrific mentor, encouraging graduate students, junior scholars, and others to submit their work when he heard them present at conferences. The society, journal, and the profession at large suffered a great loss with Joe’s death in July 2015. The forthcoming 2018 winter issue of the journal will be published in his honor.

Veronica Makowsky assumed the editorship after Joe, and the journal moved from UMass Amherst to the University of Connecticut. During Veronica’s tenure, among other innovations, the journal’s content became accessible electronically. Martha Cutter at UConn became editor next and reinstated editor’s introductions to the issues, which Joe had also provided. Martha expanded the journal’s scope further by exploring new critical and theoretical frameworks for the study of US multi-ethnic literature, including ecocritical (the study of the relationship between literature and the environment) and transnational contexts, among others, and exploring a range of genres and media. I was fortunate to be selected as editor in 2014 after Martha had served for eight years.

OUP: How would you describe the journal in three words?

GT: Groundbreaking. Field-defining. Essential.

OUP: How has the field changed since the creation of the journal in 1974?

GT: The journal reflects the changes in literary criticism since the mid-1970s. One of the changes that seems most pronounced to me is the introduction of new approaches to the study of multi-ethnic US literature, including hemispheric and transnational contexts and the insights offered by queer, ecocritical, and cultural studies, among other critical developments. Challenges to definitions of what constitutes a “text” or the “literary” have allowed the study of multi-ethnic US literature to expand to include film, graphic narratives, and other visual texts; digital media; and rap, hip-hop, and spoken word poetry, among other genres. Increased digital access to archival materials has led to important new work in print culture studies and exciting theoretical developments regarding the nature and function of the multi-ethnic archive.

OUP: Tell us more about your experience of being editor for the journal.

GT: My work as editor is one of the most satisfying scholarly activities of my career so far. I want to emphasize the word scholarly because, while a journal editorship is often categorized as “service” on university faculty annual evaluations and similar reporting mechanisms, I view it as sustained and serious intellectual work that determines the scholarly direction of a field. It’s very satisfying to be involved in such field-defining work on a daily basis. It’s also satisfying to work with authors, ranging from graduate students and junior faculty members to senior scholars, to develop their ideas and arguments. I value the vision and expertise of our guest editors who make our yearly special issues possible. I greatly appreciate the skill and collegiality of my editorial team of graduate students who manage submissions, workflow, and correspondence; copy edit; fact check; and proofread. We have a great graphic designer responsible for the terrific cover design, and I’m grateful to the artists who allow us to feature their beautiful and important work on the covers of the journal. The stellar editorial team at OUP ensures that marketing, production, permissions, and all aspects of the publishing endeavor run smoothly. I find the collaborative nature of this work nourishing in many ways.

OUP: Given everything going on in the world, how would you describe the importance of the journal?

GT: The scholarship published in our journal challenges racism, sexism, homophobia, xenophobia, and hateful rhetoric and actions of any kind. Through its thoughtful critical examination of multi-ethnic literature, culture, and experience, scholarship in MELUS centers the lives and work of the marginalized and asserts the humanity of the refugee, the migrant, and the disenfranchised. In the process, this work expands and enriches readers’ capacity to understand and empathize with others work that seems especially urgent during our current moment.

OUP: Instead of writer’s block, have you ever gotten reader’s block?

GT: Yes, I have, usually when I have read or edited submission for an extended length of time. When that starts happening, I know it’s time to stop and come back to it when I’m able to better focus.

OUP: Where is your favorite place to read and edit work?

GT: I do a lot of my reading and editing work at home. I live in the desert, and my backyard borders on a desert conservation area. I love the view of the landscape, and of the occasional rabbit, lizard, or coyote. It’s a peaceful and inspiring setting in which to work on the journal.

OUP: What are some of the benefits your members get from reading the journal?

GT: Readers gain access to exciting and award-winning scholarly work in the field and to the widest range of such scholarly work assembled in one journal. In addition to cutting-edge scholarship, the journal also sometimes includes interviews with current writers, which provide unique insights into the work and craft of these writers.

OUP: What is the most difficult part of being an editor?

GT: One of the most difficult tasks as an editor is to reject interesting work. The volume of submissions means that a high percentage of submissions that might require revision will not make it into the journal.

OUP: What do you hope to see in the coming years from both the field and the journal?

GT: The journal will continue to reflect changes in literary and cultural studies generally and approaches to multi-ethnic US literature and culture specifically. I think that the geographical and critical contexts for the study of such texts will continue to expand. Although we receive a number of submissions from international scholars, I would very much like to see an increase in submissions from scholars around the world. At the journal’s conference held at MIT in 2017, the current president of the society, Joe Kraus, organized a panel examining the question, “What is Multi-Ethnic US Literature?” This is a question that we should continue to pursue, and one that I would love to see taken up in the journal. How have our understanding and definitions of “multi-ethnic” and “literature” changed? Are there other terms that reflect the kind of work that the journal and society undertake? How might we address the ways in which the important contexts of sovereignty and tribal identity necessary for understanding Native American literary traditions, for example, interrogate ideas about “multi-ethnic” and nationality? How do hemispheric and comparative approaches challenge definitions of literary traditions that depend on national identities or borders? I hope discussion of these questions will be part of the journal’s future.

Featured image credit: Team, man, woman and business photo by rawpixel. Public Domain via Unsplash.

The post The past, present, and future of MELUS: Multi-Ethnic Literature of the United States appeared first on OUPblog.

International disability rights and the dilemma of domestic courts

Since 1992, 3 December has been the International Day of Persons with Disabilities. According to the World Report on Disability, approximately one in five people in the world are disabled and are at heightened risk of exclusion, disadvantage, and poverty.

Law plays an important role in tackling this inequality and exclusion. For the past decade, the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (the Disability Convention) – an instrument of international law – has been both a catalyst and guide for legislative reform enhancing the equality and inclusion of disabled people. To what extent, though, is this Disability Convention influencing domestic case law? This question has attracted surprisingly little attention to date, despite the fact that its importance was signalled in one of the earliest cases decided by the UN Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities – Nyusti and Takács v Hungary.

Nyusti concerned the failure of a private sector Hungarian bank to provide ATM machines that were accessible to blind people. The Hungarian Supreme Court had ruled that equality legislation could not help the blind claimants because they had originally become customers of the bank knowing that the ATM machines were not accessible. The Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities found, however, that Hungary was in breach of the Convention for failing to take adequate steps to ensure the accessibility of banking services. The UN Committee recommended, not only that the Hungarian government must ensure that all newly procured ATMs were accessible, but also that it ensure that “appropriate and regular training on the scope of the Convention” be provided “to judges and other judicial officials in order for them to adjudicate cases in a disability-sensitive manner.”

Our recent study grapples with the question of how national courts are using and interpreting this Disability Convention. Consistent with Christopher McCrudden’s work on the UN Convention for the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women, we found that usage patterns of the Disability Convention could not be explained solely, or even primarily, by reference to the constitutional approaches taken by different countries to the incorporation of international treaties into their domestic law. We also found that, where judges did use the Disability Convention, they appeared to be using it with an eye to solving domestic problems, rather than as part of an effort to identify interpretations consistent with accepted principles of international treaty interpretation. Judgments rarely engaged in substantive interpretations of the Convention’s provisions – an omission which risks misunderstandings of core, but often counter-intuitive, Convention concepts such as reasonable accommodation (which can be mistakenly assumed to be all about housing rather than as a cross-cutting duty not to discriminate in all aspects of life) and independent living (which can be mistakenly assumed to involve living without help from others). For example, in a recent German case, the Federal Social Court interpreted “independent” as meaning that persons with disabilities should be independent of the need to rely on the help of others. This interpretation of “independent” appears to overlook the particular way in which that term is used within the context of Article 19, where the emphasis is on securing choice and control over support and not on removing the need for support.

Nevertheless, some Convention provisions did appear to be influential in driving positive case law developments. Notable examples are the Disability Convention’s broad approach to the meaning of ‘disability’ – which led the Court of Justice of the European Union to overturn its earlier case law on the point; its classification of an unjustified denial of a ‘reasonable accommodation’ as a form of discrimination – which was used by the High Court of Bombay to fill in gaps in domestic equality law; and its requirement that people with disabilities be given support to exercise their legal capacity – which was used by the Constitutional Court in Russia to find that plenary guardianship was unconstitutional, and that a less restrictive alternative was required.

Judges seldom referred to interpretations of the Disability Convention given by courts in other countries. This may in part be due to the absence of a convenient means of locating relevant cases in other countries. Or it may simply be a reflection of the fact that the judges are primarily engaged in an inward-looking exercise, focusing on issues within their own jurisdiction. Reference to the Convention’s impact on, and interpretation through, European legal systems (notably EU law and the European Convention on Human Rights) were more common. The relatively clear enforcement and implementation mechanisms associated with these regional systems provided judges with opportunities to draw on Disability Convention standards when they might otherwise have felt they were barred from doing so – eg prior to domestic ratification of the Convention (Ireland) or where there was a strongly dualist approach to international treaties, coupled with the absence of a written constitution guaranteeing rights (UK).

It seems clear that the Convention’s standards are percolating into domestic case law. The fact that most judges who use the Disability Convention do not appear to engage in detailed substantive analysis of its meaning creates opportunities and risks: opportunities for innovation and creative legal problem-solving; and risks of interpretations which are blatantly inconsistent with the object and purpose of the Convention. There are also, of course, significant risks of under-use of the Convention standards in situations where it could assist in interpreting ambiguous domestic law.

Courts and judges have an important role to play in empowering people with disabilities and securing their human rights. For this to happen, we need more information about what is happening in practice, and we need more initiatives to share relevant case law and the factors that shape it so that judges and others can learn from experiences in different countries.

Featured Image: ATM keypad with braille by redspotted. CC by 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post International disability rights and the dilemma of domestic courts appeared first on OUPblog.

December 9, 2018

Dynasties: tigers and their solitary homes

Striking in appearance, tigers are fierce hunters of the forest which first evolved around two million years ago; today, they are sadly declining in population size due to poaching, habitat loss, and prey depletion.

Tasked with closing BBC documentary Dynasties, tigers are very unlike any of the other species featured throughout the series, preferring to live alone rather than cooperate in large social groups. Find out more about this solitary big cat through our selection of facts about how tigers behave and interact with others.

We hope you have enjoyed our blog series throughout the past month. Why not revisit past blogs in the series on chimpanzees, emperor penguins, lions, and painted wolves?

Hunting tigers are best left aloneIn contrast to the other big cats documented by Dynasties, tigers strictly hunt alone. Although we learnt in a previous blog post in this series that lions in fact actively hunt alone while the rest of the pride watches, tigers do not hunt with an audience. This is due to the difference in habitat: lions hunt in open habitats, such as savannas, while tigers hunt in a closed environment including forests, adopting a “stalk and ambush” tactic – with the assistance of their stripes to camouflage them against their background – which is not effective with a group. Tigers also have stronger teeth and a more powerful bite force than any other big cat, allowing them to deftly kill their prey alone with a crushing bite to the back of the neck.Apprentice hunters

Cubs are taught to hunt by their mothers from the ripe young age of six months. Prior to this, cubs are taken to kill sites to eat the felled prey aged 1-2 months, but they will not participate in the actual hunting, stalking, and killing for several months more. Cubs become independent at 15 months old, when their mother likely has a new litter, at which point they gradually separate from their mother. If the cub is female, the mother may donate some or all of her territory to her daughter, as this greatly increases the daughter’s chances of survival and reproduction.

Image credit: Malayan Tiger Cubs by Malcolm. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Far-flung family

Image credit: Malayan Tiger Cubs by Malcolm. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Far-flung familyRather than living in a close-knit group like many other species featured in Dynasties, tigers have a dispersed social system through which they maintain social contacts but from the distance. Each tiger claims some land to be their territory, which they defend against intruders of the same sex. Female tigers have a smaller amount of territory, which is determined by how much food and water they need to survive and raise their cubs. Territory size also varies depending on the type of habitat – for example, the density of trees – as well as the tiger’s age; tigers mark their habitat primarily through scent and visual signals such as claw marks on the ground and trees to warn other tigers off.

Image credit: Bengal tiger roaring by Neerajsaxena0711. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.A mate a week

Image credit: Bengal tiger roaring by Neerajsaxena0711. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.A mate a weekTigers aren’t monogamous creatures. Instead, a male and female tiger will stay together for five to seven days, mating as much as possible during this time to ensure success. After a week is up, the male tiger leaves the female’s territory to go in search of another female to mate with in an attempt to father as many cubs as possible.Male defence and breeding

Male tigers aim to defend the territories of as many female tigers as possible. The stronger and the better at fighting the tiger is, the better he can defend the females’ territories from defenders, while also maintaining the size of his own territory. A male tiger’s success in female territory defence grants him exclusive breeding rights with those females, thus ensuring the strongest genes are passed on to future generations of tigers.No cubs are safe

Male tigers don’t have an active hand in raising their young, instead leaving the mother to be the primary carer, occasionally visiting to share kills with the mother and cub. The father will also continue to protect the mother’s territory…until he is displaced by a rival male. If another male tiger successfully takes over the father’s territory, he will also kill any cubs the ousted male fathered. This forces the female to come into heat and bear his offspring sooner.

Featured image credit: Siberian Tiger Family by Mathias Appel. Public Domain via Flickr .

The post Dynasties: tigers and their solitary homes appeared first on OUPblog.

There are two different types of Jane Austen fans

There is a theory current among many of my fellow Janeites about what kind of a Jane Austen devotee one can be. Either, it is said, one unreservedly cleaves to the Austen of Pride and Prejudice and Emma, or one empathically embraces the Austen of Persuasion and Sense and Sensibility. One cannot love both, not equally, not without reservations about one or the other set of works, even if one likes and admires all of Austen’s writing.

I nevertheless place myself squarely in the second camp. Persuasion is my favorite Austen novel. I have always found Anne Elliot Austen’s most endearing heroine, and Captain Wentworth by far the most attractive romantic interest (not a rich snob, not a parson, not annoyingly overburdened with a sense of his own rectitude). I delight in the novel’s subtle inclination toward utilitarianism and its depiction of the relationship between equals exemplified by Admiral and Mrs. Croft.

I have to wonder, however, about the difference between the two aforementioned targets for Janeite affection. Is it to be found in the contrast between the relative extroversion and introversion of the novels’ heroines, or perhaps in the degrees to which Humean pride and humility govern their respective characters (I will just note here that Hume has a bit of a soft spot for pride and would probably like Emma quite a lot)? Is it to be found in the reader’s tendency to empathize or identify with one set of traits rather than another? This latter suggestion strikes me as unlikely. While I enjoy all of Austen’s novels, I don’t like Emma’s mistakes or the fictional fact that she is so often wrong (at other people’s expense, rather than just her own). Of course, I suspect that this reaction is largely due to the not-at-all-fictional fact that I am more likely to make mistakes of that kind (and therefore to wince at their depiction). I clearly to identify with Emma, I just like her less than Anne.

On one memorable occasion, I took one of those “Which Austen character are you?” personality tests (I stand ready to construct another, much better test of this sort, the moment someone offers me a substantial sum of money to do it) only to discover that I was Mary Crawford of Mansfield Park, certainly as far from the self-effacing Anne Elliot as one could possibly be. Probably it was an accurate test, as such things go, but such a finding certainly jettisons any notion of preference based on identification with the protagonists of the novels at issue.

The heroines of these novels are near opposites, but each novel provides the same clear, strong focus on issues involving autonomy and autonomous agency. They just do so from diametrically opposed perspectives.

My tentative hypothesis about the aforementioned disparity in Janeite tastes is based on a few philosophical considerations. Consider Emma and Persuasion in particular. Emma was begun in 1814 and completed in 1815, during which year Persuasion was begun. Persuasion was completed in 1816 and published posthumously in 1817. The heroines of these novels are near opposites, but each novel provides the same clear, strong focus on issues involving autonomy and autonomous agency. They just do so from diametrically opposed perspectives.

Consider that much of Emma concerns, as Gilbert Ryle would have it, the issue of solicitude. Emma Woodhouse interferes in the lives of others and influences their decision making, often to ill effect. She is herself, on the other hand, given that she is overconfident and fond of her own way, quite difficult to influence. It is only through seeing her mistakes and understanding what produced them that she relinquishes her inclination to orchestrate other people’s lives and begins to accept occasional advice about her own. Anne Elliot, on the other hand, is too easily influenced by others. She lacks confidence. She allows her decisions to be swayed by others in a way that is contrary to her happiness because she is inclined to distrust her own impulses and choices. Anne Elliot, that is, is on the receiving end of the kind of treatment that Emma Woodhouse doles out. Anne’s father is vain and profligate and will never heed her advice, while Mr. Woodhouse is placid and risk-aversive and entirely dependent on Emma. Emma has been the mistress of her household since her mother died. Anne has been largely ignored and neglected since her mother’s death, and can exert no corrective influence on her relations. We have two motherless young women, each with siblings who are entirely unlike them in character, each confronted with the important issue of independence and autonomy: their own, and that of others in what Hume would call their narrow circle. Emma acts on others while Anne is acted on. Emma profits in the end from the acquisition of a modicum of humility, while Anne profits from the acquisition of a certain self-confidence and pride.

Perhaps the kind of preference which Austen lovers are wont to note involves a preference for one or the other of the following: an interest in forging independence or an interest in respecting that of others, an interest in self-development and autonomous agency, or an interest in recognizing and respecting the boundaries of others. Emma and Persuasion are both stories of change and self-development and maturation, one chronicling a turning inward and self reflection, the next describing a turning outward and a venturing forth into the world.

Featured image credit: Royal Crescent 1829 by Unknown. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons .

The post There are two different types of Jane Austen fans appeared first on OUPblog.

December 8, 2018

Have you heard of René Blum?

Happy Hanukkah from OUP! This year we’re celebrating with a series of eight books celebrating Jewish history and culture over the eight nights of Hanukkah. As your menorah candles burn bright, take this opportunity to honour both the endurance of the Maccabees and the Jewish people.

In this blog post, Judith Chazin-Bennahum, author of René Blum and The Ballets Russes: In Search of a Lost Life, provides an insight into the incredible life of René Blum.

Well? Have you? If not, it’s probably because René Blum’s lifelong career in the arts has been safely hidden from the history books. Only his brother Léon Blum, the first Socialist and Jewish Prime Minister of France, received enormous attention. But Judith Chazin-Bennahum knows why René Blum deserves to be remembered: because he was an extraordinary man. Chazin-Bennahum’s book introduces the reader to the world of the Belle Epoque artists and writers, the Dreyfus Affair, the playwrights and painters who reigned supreme during the late 19th century and early 20th century period in Paris. Below she provides us with just a few of his most impressive accomplishments.

Caught in one of the deadliest battles at the Somme, as a French soldier in WWI under enemy fire, Blum saved important works of art from Amiens and for his bravery received the Croix de Guerre. He kept a brief journal about his experiences during the war describing the constant thunder of distant cannon and featured the deadly boredom of being a soldier. Later, during the Holocaust he was shocked that he was imprisoned having served his country honorably during wartime.As editor of the Parisian literary journal Gil Blas, Blum singlehandedly arranged for the publication of Marcel Proust’s Du côté de chez Swann (Swann’s Way) the first volume of La Recherche du Temps perdu, (In Search of Lost time) by the publisher, Bernard Grasset. When Proust was a young and radical author, he received many letters of rejection, including one from André Gide.After the death of the great ballet impresario, Serge Diaghilev, René Blum brought back to life the Ballets Russes de Monte Carlo, engaging the greatest talents in ballet in 1932. As Artistic Director of the Théâtre du Monte Carlo, he succeeded in convincing his colleagues that resurrecting the Ballets Russes would be a boon to the theatre and the public of Monte Carlo. He hired the Colonel de Basil as his partner in this grand venture but soon lost respect for de Basil who tried to overtake Blum in the running and administering of the company. They parted soon after in 1934.René Blum oversaw the extraordinary performances of young Balanchine’s early works in 1932, Cotillon and La Concurrence, as well as the symphonic ballets of Leonide Massine, Les Présages and Choriartium that rocked the dance scene, as well as the classical pieces of Michel Fokine including Petrouchka and Les Sylphides. Bronislava Nijinska, the brilliant choreographer of the Ballets Russes was hired to replace de Basil and presented her Bolero, and Les Comédiens Jaloux.Blum saved many dancers and choreographers from the ravages of World War II by selling his company to American entrepreneurs in 1940. Blum had been with the company in the United States when the war broke out but he fatally chose to return to Paris to be with his son Claude René and also his brother Léon who was on trial and in prison in Vichy France.Although quite ill while imprisoned at Drancy, the infamous concentration camp near Paris, he gave lectures on French literature and ballet to distract the others from their pain and hunger. He behaved heroically before he was murdered at Auschwitz, complaining of the terrible conditions for his fellow prisoners in the camps.Feature image credit: “Ksenia Kern, balerina” by Sergei Gavrilov. CCO via Unsplash.

The post Have you heard of René Blum? appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers