Oxford University Press's Blog, page 202

February 15, 2019

Congratulations to Cyberwar

Oxford University Press has won the 2018 R. R. Hawkins Award, which is awarded by the Association of American Publishers to a single book every year to “recognize outstanding scholarly works in all disciplines of the arts and sciences.” This year’s winner is Kathleen Hall-Jamieson’s Cyberwar: How Russian Hackers and Trolls Helped Elect a President.

Kathleen Hall Jamieson. Image Credit: The Annenberg Foundation Trust at Sunnylands

Kathleen Hall Jamieson. Image Credit: The Annenberg Foundation Trust at SunnylandsIn Cyberwar, Kathleen Hall Jamieson marshals the troll posts, unique polling data, analyses of how the press used hacked content, and a synthesis of half a century of media effects literature to argue that, although not certain, it is probable that the Russians helped elect the 45th president of the United States. In the process, she asks: How extensive was the troll messaging? What characteristics of social media did the Russians exploit? Why did the mainstream press rush the hacked content into the citizenry’s newsfeeds? Was Clinton telling the truth when she alleged that the debate moderators distorted what she said in the leaked speeches? Did the Russian influence extend beyond social media and news to alter the behavior of FBI director James Comey? After detailing the ways in which Russian efforts were abetted by the press, social media, candidates, party leaders, and a polarized public, Cyberwar closes with a warning: the country is ill-prepared to prevent a sequel.

The award is usually given to serious long-term reference projects, which include past Oxford University Press winners such as The Oxford History of Western Music, American National Biography, and the International Encyclopedia of Dance, so the awarding of the prize to a width="107" height="162" />

Other notable Oxford University Press book mentions for this year’s PROSE awards include:

Down Girl: The Logic of Misogyny by Kate Manne in two categories for Excellence in Humanities and Philosophy

The New Negro: The Life of Alain Locke by Jeffrey Stewart in the Biography category

Cajal’s Neuronal Forest: Science and Art by Javier DeFelipe in Biomedicine and Neuroscience

EuroTragedy by Ashoka Mody in Economics

Cyberwar by Kathleen Hall-Jamieson also won for Excellence in Social Sciences and Government, Policy and Politics

Featured image credit: Books by Gael Varoquaux. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Congratulations to Cyberwar appeared first on OUPblog.

Can Self-Help Save the World?

Many meditators, yogis, and other spiritual practitioners will answer this question with a resounding yes. Critics – ranging from religious studies and management scholars to serious Buddhist practitioners – may disagree.

Mindfulness meditation, which has grown exponentially in popularity in recent years, is commonly associated with a wide-ranging set of contemplative practices aimed at training oneself to pay “attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment and nonjudgmentally,” as defined by Jon Kabat-Zinn, the founder of the Center for Mindfulness in Medicine, Healthcare, and Society.

Early leaders in the mindfulness movement, many of whom came of age in the counterculture of the 1960s and 1970s, had a more activist bent; they hoped that mindfulness would lead to a wave of self-actualization, increased compassion for others, and democratic decision-making. With these tools, humanity would be able to collectively address the many complex social problems we collectively face, such as racism, overconsumption, economic inequality, and environmental degradation.

To investigate the spread of mindfulness across powerful social institutions in science, healthcare, education, business, and the military, I travelled around the country from 2010-2012, and again in 2015, talking with leaders of the mindfulness movement. The passionate, inspiring mindfulness advocates at top Ivy League and flagship universities, at Fortune 500 companies like Google and General Mills, at K-12 schools, and the U.S. military had personally benefited from meditating and felt bolstered by a wave of scientific evidence which has supported the practices’ beneficial effects on well-being, memory, attention, meta-awareness, cognitive flexibility, and emotional regulation. Above all, by sharing mindfulness, meditators believed they not only transformed themselves, but the world around them.

Yet, most meditators I spoke with revealed more self-centered effects from spending time in quiet contemplation. This was not surprising to some of mindfulness’ leaders.

Sitting in his office at the Center for Mindfulness in Medicine, Healthcare, and Society in January of 2015 in Shrewsbury, Massachusetts, Executive Director Saki Santorelli told me that people loved to do mindfulness because they learned about who they were, and through the practice, they transcended who they previously were, and who they had thought they were. This process was intrinsically rewarding and exhilarating.

People come to their mindfulness program, he said, because they have “a Real. Life. Problem. Something is just not right,” he said. “And what keeps people engaged is . . . the most interesting topic in the world.” He paused and turned toward me.

“What is this most interesting topic in the world?” He paused again, waiting.

“The most interesting topic in the world,” he responded, “is me.” He continued, “People come here because they are interested in me. Meaning themselves. And something’s not quite right about me or I want to learn more about me including “how am I going to live with this condition for the next 20 or 30 or 40 years?”

In teaching mindfulness at the Center, they seek to “draw out,” rather than “pour in” knowledge. They seek to ignite “a fire with people to know more about ‘who’ or ‘what’ I actually am,” he said. He explained:

They start with practice. Practice reveals not because I say so, but because they discover it. They discover that they have a breath, they discover that it feels a particular way, they discover something about the relative present moment, whatever that is. They discover something about what happens in their viscera when they have a particular thought or a particular emotion . . . They discover the ways that they’re conditioned or limiting themselves or living today out of yesterday’s memory, about whom or what I am or what I’m capable of. And they love it. . . . And whenever people discover a little bit more about who they are, they transcend. And ultimately, I think that’s what’s transformative—is that sense of transcending. Transcend some idea about who you think they are, even if it’s a tiny little idea, and then you feel more room.

Others found meditation useful for different reasons. Neuroscientist Ravi Chaudhary (pseudonym used upon request) thought mindfulness practice provided him with a critical cognitive distance that enabled him to pause, reflect, and ultimately, have greater self-control in facing the challenges that arose in his life. He has learned “not be super reactive to unpleasant situations,” he said. “There’s difficult situations no matter what,” but with mindfulness, he now can take “a moment, sit back and accept that . . . I am not part of it, but rather it is there and I am here.” This helps him make decisions “as if it’s a presumed situation,” and he feels less entangled with difficult situations.

These effects of mindfulness meditation are no doubt important: they help people learn about themselves and, hopefully, engage in more thoughtful decision-making. Mindfulness meditation can also have a therapeutic effect for many people, helping them de-stress, calm themselves and provide openings to experience a sense of peace.

However, mindfulness’s impact off the cushion of the larger organizations and communities where it is practiced largely remains to be seen. Most mindfulness programs have never gotten around to confronting the many larger-scale social problems we face as a society; in fact many newer practitioners might be surprised to learn that founders of early mindfulness programs had sought out such activist-minded ends. In speaking with dozens of program leaders and mindfulness teachers, only a handful had any evidence at all that their programs’ impacts extended beyond the program’s direct participants and into the larger organizations they were a part of.

The impact of mindfulness practice, even among top CEOs and corporate leaders, is largely not trickling down into their larger companies and causing them to cut down expected work hours or loads or increase wages, which are the fundamental causes of the stress many Americans face today. While meditation practices may individually improve the lives of practitioners, and perhaps even those they regularly interact with, it is less clear how the practices lead to the collective action needed to address the complex social problems we face daily in our workplaces and in our democracy.

Yet, the myth that mindfulness will lead to a more progressive, utopian world continues to linger, as a mirage, that might appear just around the bend.

Featured image credit: “Take a seat photo” by Simon Wilkes. Public Domain via Unsplash.

The post Can Self-Help Save the World? appeared first on OUPblog.

How self-help can help the world

Many meditators, yogis, and other spiritual practitioners will answer this question with a resounding yes. Critics – ranging from religious studies and management scholars to serious Buddhist practitioners – may disagree.

Mindfulness meditation, which has grown exponentially in popularity in recent years, is commonly associated with a wide-ranging set of contemplative practices aimed at training oneself to pay “attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment and nonjudgmentally,” as defined by Jon Kabat-Zinn, the founder of the Center for Mindfulness in Medicine, Healthcare, and Society.

Early leaders in the mindfulness movement, many of whom came of age in the counterculture of the 1960s and 1970s, had a more activist bent; they hoped that mindfulness would lead to a wave of self-actualization, increased compassion for others, and democratic decision-making. With these tools, humanity would be able to collectively address the many complex social problems we collectively face, such as racism, overconsumption, economic inequality, and environmental degradation.

To investigate the spread of mindfulness across powerful social institutions in science, healthcare, education, business, and the military, I travelled around the country from 2010-2012, and again in 2015, talking with leaders of the mindfulness movement. The passionate, inspiring mindfulness advocates at top Ivy League and flagship universities, at Fortune 500 companies like Google and General Mills, at K-12 schools, and the U.S. military had personally benefited from meditating and felt bolstered by a wave of scientific evidence which has supported the practices’ beneficial effects on well-being, memory, attention, meta-awareness, cognitive flexibility, and emotional regulation. Above all, by sharing mindfulness, meditators believed they not only transformed themselves, but the world around them.

Yet, most meditators I spoke with revealed more self-centered effects from spending time in quiet contemplation. This was not surprising to some of mindfulness’ leaders.

Sitting in his office at the Center for Mindfulness in Medicine, Healthcare, and Society in January of 2015 in Shrewsbury, Massachusetts, Executive Director Saki Santorelli told me that people loved to do mindfulness because they learned about who they were, and through the practice, they transcended who they previously were, and who they had thought they were. This process was intrinsically rewarding and exhilarating.

People come to their mindfulness program, he said, because they have “a Real. Life. Problem. Something is just not right,” he said. “And what keeps people engaged is . . . the most interesting topic in the world.” He paused and turned toward me.

“What is this most interesting topic in the world?” He paused again, waiting.

“The most interesting topic in the world,” he responded, “is me.” He continued, “People come here because they are interested in me. Meaning themselves. And something’s not quite right about me or I want to learn more about me including “how am I going to live with this condition for the next 20 or 30 or 40 years?”

In teaching mindfulness at the Center, they seek to “draw out,” rather than “pour in” knowledge. They seek to ignite “a fire with people to know more about ‘who’ or ‘what’ I actually am,” he said. He explained:

They start with practice. Practice reveals not because I say so, but because they discover it. They discover that they have a breath, they discover that it feels a particular way, they discover something about the relative present moment, whatever that is. They discover something about what happens in their viscera when they have a particular thought or a particular emotion . . . They discover the ways that they’re conditioned or limiting themselves or living today out of yesterday’s memory, about whom or what I am or what I’m capable of. And they love it. . . . And whenever people discover a little bit more about who they are, they transcend. And ultimately, I think that’s what’s transformative—is that sense of transcending. Transcend some idea about who you think they are, even if it’s a tiny little idea, and then you feel more room.

Others found meditation useful for different reasons. Neuroscientist Ravi Chaudhary (pseudonym used upon request) thought mindfulness practice provided him with a critical cognitive distance that enabled him to pause, reflect, and ultimately, have greater self-control in facing the challenges that arose in his life. He has learned “not be super reactive to unpleasant situations,” he said. “There’s difficult situations no matter what,” but with mindfulness, he now can take “a moment, sit back and accept that . . . I am not part of it, but rather it is there and I am here.” This helps him make decisions “as if it’s a presumed situation,” and he feels less entangled with difficult situations.

These effects of mindfulness meditation are no doubt important: they help people learn about themselves and, hopefully, engage in more thoughtful decision-making. Mindfulness meditation can also have a therapeutic effect for many people, helping them de-stress, calm themselves and provide openings to experience a sense of peace.

However, mindfulness’s impact off the cushion of the larger organizations and communities where it is practiced largely remains to be seen. Most mindfulness programs have never gotten around to confronting the many larger-scale social problems we face as a society; in fact many newer practitioners might be surprised to learn that founders of early mindfulness programs had sought out such activist-minded ends. In speaking with dozens of program leaders and mindfulness teachers, only a handful had any evidence at all that their programs’ impacts extended beyond the program’s direct participants and into the larger organizations they were a part of.

The impact of mindfulness practice, even among top CEOs and corporate leaders, is largely not trickling down into their larger companies and causing them to cut down expected work hours or loads or increase wages, which are the fundamental causes of the stress many Americans face today. While meditation practices may individually improve the lives of practitioners, and perhaps even those they regularly interact with, it is less clear how the practices lead to the collective action needed to address the complex social problems we face daily in our workplaces and in our democracy.

Yet, the myth that mindfulness will lead to a more progressive, utopian world continues to linger, as a mirage, that might appear just around the bend.

Featured image credit: “Take a seat photo” by Simon Wilkes. Public Domain via Unsplash.

The post How self-help can help the world appeared first on OUPblog.

February 14, 2019

Oral sex is good for older couples

Is it difficult or even embarrassing to imagine grandparents having oral sex? Indeed, most studies of oral sex focus on adolescents or younger adults, while research on sexuality in late life is primarily focused on sexual dysfunctions from a medical perspective, contributing to the prevailing stereotype that most older adults are sexually inactive or asexual due to health conditions or related medication use. However, data from the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project showed that a significant share of older couples were sexually active and about 37% of them had participated in oral sex in the past year.

Despite the fact that many older adults stay, or want to stay, sexually active, a significant share of them suffer from sexual dysfunctions that make penile-vaginal intercourse more difficult. Therefore, oral sex may play an important but overlooked role in encouraging sexual behavior and thus enhancing well-being in late adulthood. However, empirical studies of oral sex are limited, and virtually all of them focus on younger adults and have shown mixed evidence on oral sex links to well-being. Some studies suggest that oral sex, either as foreplay or as a replacement for vaginal sex, may enhance sexual enjoyment and satisfaction, and in turn increase the chance of orgasm and promote emotional closeness and well-being: whereas others suggest that oral sex has less benefit to people’s happiness and well-being than vaginal sex. Nevertheless, empirical evidence on implications of oral sex for people’s well-being especially among older adults, is lacking.

We analyzed 884 older heterosexual couples, with at least one spouse older than age 62, from the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project data to provide the first nationally representative evidence linking oral sex, relationship quality, and psychological well-being. We found that receiving oral sex was positively related to both men’s and women’s perceptions of relationship quality, which in turn promoted their happiness and mental health and reduced psychological distress.

Interestingly, we found that men’s giving oral sex was also positively related to their own emotional well-being, in part because it heightened their wife’s happiness in their relationship. However, women’s giving oral sex was unrelated to their own well-being although it did increase their husband’s happiness in the relationship. A wife’s appraisal of happiness in the marital relationship was related to both her own and her husband’s emotional well-being, while husband’s feelings of marital happiness were related only to his own well-being, not his wife’s. Because women usually play the primary role in caregiving, managing household work, and providing emotional support in the relationship, and men tend to benefit more from the relationship, it is not surprising that “her” appraisal of the relationship has a key impact on the couple’s well-being.

Another interesting finding is that men who had more negative feelings about their relationship were less likely to give oral sex to their wife, but when women had negative feelings about their relationship, it did not affect whether they gave oral sex to their husband.

As we celebrate Valentine’s Day, let’s refresh our senior couples’ excitement of this special holiday! When other family members, friends, and neighbors are lost due to geographic relocation and death in late adulthood, a spouse or partner may play an increasingly crucial role in older couples’ well-being.

The post Oral sex is good for older couples appeared first on OUPblog.

February 13, 2019

Dissecting the verb “hitchhike”

It is hard to believe how recent the verb hike is. Slightly more than a hundred years ago, The Century Dictionary (CD) found a slot for hike only in the supplement, and this is what we read there: “Also hyke; a widely used dialect word, parallel to hick, recently emerging into some colloquial use; prob[ably] orig[nally] an imitative word, parallel to hit, expressing a quick stroke or motion.” As “parallel” to it the CD mentions East Frisian [actually, Low German] hikken “thrust, push, punch,” and the reference is given to hick and hit. Hick “to hop, spring”, another regional word, we discover, is probably a variant of hip “to hop,” which, too, is regional and obsolete. With hit there are no problems: it is a borrowing from Scandinavian (Old Icelandic hitta and so forth), except that its origin in Scandinavian (Old Norse) is, alas, unknown. In 1907, the noted American etymologist Francis Asbury Wood called hike “a quick or sudden movement” slang.

The OED also included hike only in the supplement. The entry contained citations going back all the way to 1809, and, what is important, among the senses we find “to walk laboriously; tramp,” in recent use “to walk for pleasure”; then all the now familiar senses are listed. With regard to etymology, we are invited to compare hoick “to lift up, often with a jerk,” said to be perhaps originally a local variant of hike. This derivation is probable, because the pronunciation of oi for i is widely known, and Standard English owes several well-established words to it, for example, boil and groin. Thus, we have hike, hoik, hick, and hit. The members of the trio hike ~ hoik ~ hick may well be cognates, but hit, with its final t, looks a bit suspicious. Besides, the word parallel in the CD raises questions. Does it mean “related to” or “resembling”? Dictionaries are fond of such evasive formulations.

This is the famous Alfred (“Hitch”) Hitchcock. Image credit: Alfred Hitchcock NYWTS byLibrary of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. New York World-Telegram and the Sun Newspaper Photograph Collection. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

This is the famous Alfred (“Hitch”) Hitchcock. Image credit: Alfred Hitchcock NYWTS byLibrary of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. New York World-Telegram and the Sun Newspaper Photograph Collection. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.The plot thickens once we invite Walter W. Skeat as an authority. In his lifetime, the “concise” version of his great etymological dictionary appeared in 1911, one year before his death. Hike is not there, but it turns up in the entry hitch, which is a piece of good luck, because we are most interested in the origin of hitchhike. Skeat compares hitch with Lowland Scotch hatch and hotch and then, without explaining the progress of his thought, adds “provincial English” hike “to toss” and hikey “a swing.” Finally, he notes that hook is not related to this group. It should not come as a surprise that Skeat compared hitch and hike. Although hitch turned up only in Middle English, if it existed earlier, it may have sounded as hickan or hyckan.

Ernest Weekley, the author of the only original one-volume English etymological dictionary of the post-Skeat era, observed that, if in the group hitch ~ hatch ~ hotch the “main” verb was hotch, it could go back to French hocher “to shake,” known to English speakers from hotchpotch (or hodgepodge), a word the French borrowed from Middle Dutch. Be that as it may, we witness a typical case of elementary, or primitive, word formation, which I have discussed in this blog more than once, first in connection with the origin of butterfly (see the post for May 21, 2007). Such monosyllabic verbs as dig, hit, hitch, kick, pick, peck, and put cannot be called sound-imitative (unlike grunt, bark, caw, meow, and so forth), but they have been aptly called symbolic.

People produce them almost instinctively. Hence the impression that such words come from nowhere. They often look alike in unrelated languages, so that, while dealing with them, the idea of cognates becomes vague, almost illusory. Old English had the verb hīgian “to strive, pant” (predictably, of unknown origin), the etymon of the obsolete Modern Engl. hie “to hurry, move quickly” (that is, “to push one’s way forward”?), and in the Westphalia dialect of German hick-hick “cheese worm” (a pushy creature?) has been attested. We may have a hacking cough, and we hiccup when we have a kick (!) in the throat or a catch in the voice: all such words render the same strong or spasmodic effort familiar from hitch and hit. That is why ingenious hypotheses of the origin of hike inspire little confidence. For example, it has been suggested that hike is a blend of hie and (wal)k—a most improbable idea, even though its author was Ferdinand Holthausen, a distinguished philologist. Those fond of etymological curiosities may also look up hit in Horne Tooke’s Diversions of Purley. Tooke derived numerous words from past participles. He treated hit in the same preposterous way.

We certainly prefer a hitchhiker to a hit man, even if hit and hitch are related. Image credit (top to bottom): Hitchhiker at city limits of Waco, Texas by Library of Congress. Public Domain via Picryl/ Hitman Launches March 11 with Three Locations by BagoGames. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

We certainly prefer a hitchhiker to a hit man, even if hit and hitch are related. Image credit (top to bottom): Hitchhiker at city limits of Waco, Texas by Library of Congress. Public Domain via Picryl/ Hitman Launches March 11 with Three Locations by BagoGames. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.The Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology has no suggestions about the origin of hike; it only states that the verb is of dialectal origin. However, a dialectal or slang word also has a source. Hit ~ hitch ~ hike, hitch ~ hatch ~ hotch are typical examples of sound complexes people coin to make clear the idea of striking, jerking, and the like. It does not seem unreasonable to explain hit, hitch, hike and the rest as symbolic and feel satisfied. Such verbs and even nouns have existed forever. Yet we tend to treat old words of this type with undue reverence. For example, in Gothic, a Germanic language, recorded in the fourth century, haiftsts “fight, quarrel” turned up. Its origin is, predictably, unknown. Francis A. Wood suggested that haifsts might belong with hoist, hike, hick “to hop,” and a few others. This etymology does not look fully convincing, but it is not indefensible.

Considering how many examples of hike Joseph Wright gives in his English Dialect Dictionary, we may be certain that this verb never disappeared from British dialects. It must have been brought by the colonists to the New World and stayed dormant there for a long time. How and why it suddenly surfaced, became universally known and even respectable remains unclear. Around 1870, it was American college slang for “to move vigorously” (“You’ve got to hike around, and fling some style inter your victuals”). When hike reached the general public, it had the status of an Americanism, but, like numerous other so-called Americanisms, it was coined in England. In the street argot of British tramps, hike flourished long before it was noticed by the educated part of the world.

In 1930, there was a brief exchange about the verb hike in Notes and Queries. A correspondent from Kent wrote: “This is still used hereabouts, meaning to set a dog to work in a hedge. It is equivalent to ‘hie in’ [!].” It was also suggested that probably another form of hike “is the ‘hoick over’, when hounds are pushed on over a woodland ride, or a low fence, or encouraged to draw a cover.” There is a good deal of historical and etymological justice in the fact that someone in the second decade of the twentieth century coined the verb hitchhike and that it conquered the world. In principle, hitchhike is a tautological compound, with both elements meaning the same, as in pathway (compare the post for October 7, 2009 and numerous tautological phrases of the first and foremost, kith and kin, and safe and sound type). Hike might have been little known, but if one hikes with hitching, the effect is guaranteed. People realized the symbolic strength of the coinage, and, as we can see, the word has come to stay.

The post Dissecting the verb “hitchhike” appeared first on OUPblog.

Black History Month: a reading list

February marks the celebration of Black History Month in the United States and Canada, an annual celebration of achievements by Black Americans and a time for recognizing the central role of African Americans in US history.

The first variation of Black History Month was initiated by Dr. Carter G. Woodson (founder of the Association for the Study of Negro Life) in 1926 titled Negro History Week, which took place during the second week of February. The Association for the Study of Negro Life and History later expanded the February celebration in the early 1970’s, renaming it Black History Month. However, it was Some of These Days: Black Stars, Jazz Aesthetics, and Modernist Culture, James Donald

Some of These Days provides a cultural history of the Harlem Renaissance’s vast influence abroad, moving beyond simple biography to recreate the rich community of artists who interacted with-and were influenced by world’s first two major African American stars, Josephine Baker and Paul Robeson.Creating Their Own Image: The History of African-American Women Artists, Lisa E. Farrington

Creating Their Own Image offers the first comprehensive history of African-American women artists, spanning from slavery to the Harlem Renaissance and the tumultuous civil rights era, right up to the present day. Weaving together an expansive collection of artists, styles, and periods, Lisa Farrington argues that for centuries African-American women artists have created an alternative vision of how women of colour can, are, and might be represented in American culture. I Am Your Sister: Collected and Unpublished Writings of Audre Lorde, Edited by Rudolph P. Byrd, Johnnetta Betsch Cole, and Beverly Guy-SheftallThis collection of Lorde’s personal and political writing features many never-before-published works, including Lorde’s landmark 1988 essay, A Burst of Light. With personal reflections by Alice Walker, bell hooks, and others, I Am Your Sister offers new insights into Lorde’s writings.Dvorak to Duke Ellington: A Conductor Explores America’s Music and Its African American Roots, Maurice Peress

I Am Your Sister: Collected and Unpublished Writings of Audre Lorde, Edited by Rudolph P. Byrd, Johnnetta Betsch Cole, and Beverly Guy-SheftallThis collection of Lorde’s personal and political writing features many never-before-published works, including Lorde’s landmark 1988 essay, A Burst of Light. With personal reflections by Alice Walker, bell hooks, and others, I Am Your Sister offers new insights into Lorde’s writings.Dvorak to Duke Ellington: A Conductor Explores America’s Music and Its African American Roots, Maurice Peress

American conductor, Maurice Peress, recounts American music in the twentieth century and explores its African American roots. Midway through, Peress himself becomes part of the story as he describes his work with George Gershwin, Duke Ellington, and Leonard Bernstein.An American Odyssey: The Life and Work of Romare Bearden, Mary Schmidt Campbell

Mary Schmidt Campbell offers readers an enlightening insight into one of the most important and underappreciated visual artists of the twentieth century, Romare Bearden. Bearden’s work provides an exquisite portrait of memory and the African American past; according to Campbell, it also offers a record of the narrative impact of visual imagery in the twentieth century, revealing how the emerging popularity of photography, film and television depicted African Americans during their struggle to be recognised as full citizens of the United States. Katherine Dunham: Dance and the African Diaspora, Joanna Dee Das

Katherine Dunham: Dance and the African Diaspora, Joanna Dee Das

Joanna Dee Das makes the argument that Katherine Dunham, was more than just a dancer and choreographer – she was an intellectual and activist committed to using dance to fight for racial justice. As an African American woman, she broke barriers of race and gender, most notably as the founder of an important dance company that toured the United States, Latin America, Europe, Asia, and Australia for several decades.Mahalia Jackson and the Black Gospel Field, Mark Burford

Drawing on previously unexamined archival and media sources, Mark Burford explores Mahalia Jackson’s journey from church singer in New Orleans to celebrity gospel singer. The African Imagination in Music, Kofi Agawu

The African Imagination in Music, Kofi Agawu

In this accessible introduction, The African Imagination in Music breaks down the key elements of sub-Saharan music and invites general readers to participate in the scholarship surrounding it.Between the Lines: Literary Transnationalism and African American Poetics, Monique-Adelle Callahan

Between the Lines examines the role of women poets of African descent in shaping the history of the Americas. Focusing on three women whose poetry wrestled with the sociopolitical predicaments of the late nineteenth century, Between the Lines ventures a broader definition of African American literature by placing it in a hemispheric context. This represents the first extended/comprehensive study of Cuban poet Cristina Ayala and includes previously undisclosed translations of her poems. The Transformation of Black Music: The rhythms, the songs, and the ships of the African Diaspora, Sam Floyd, Melanie Zeck, and Guthrie Ramsey

The Transformation of Black Music: The rhythms, the songs, and the ships of the African Diaspora, Sam Floyd, Melanie Zeck, and Guthrie Ramsey

The Transformation of Black Music explores the dynamic musical practices of the past thousand years that emerged in Africa and throughout the African Diaspora. With an emphasis on the value of black music, this book takes readers on a journey that has never before been attempted in a single volume alone.African Affairs Journal

The top ranked journal in African Studies, African Affairs takes an interdisciplinary approach to the politics and international relations of sub-Saharan Africa. A virtual issue is dedicated to the February 2019 political elections in Nigeria.

Featured image credit: “Knowledge” by Alfons Morales. Public domain via Unsplash.

The post Black History Month: a reading list appeared first on OUPblog.

February 12, 2019

What the Paris Peace Conference can teach us about politics today

One hundred years ago, the treaty of Versailles, the centerpiece of a set of treaties and agreements collectively known as the Paris Peace Settlements, was signed in the glittering hall of mirrors in the former home of France’s Sun King. For some, the war it brought to an end marked the final chapter of a distinct period in international relations, one dominated by a European states system that had endured since the Middle Ages and in which military conflict was relatively commonplace.

Anniversaries impose a misleading unity on a period of history. Nevertheless, it can still be useful to reflect on where we once were, what has changed, and what the prospects for the future might be. 2019 represents a moment of transition in both domestic and international politics. The backlash against globalization, the rise of intolerant and anti-democratic populisms, the tensions between rising and declining powers as well as the withdrawal of the United States from its hegemonic global role, are all calling into question norms and institutions underpinning a twentieth century world order many had taken for granted.

There are suggestive and sometimes troubling parallels between 2019 and 1919. At both moments, the world witnessed a retreat from globalism, the rise of nativist and populist political parties, demands from national movements for their own states, the spread of international revolutionary movements—Bolshevism then, radical Islamism today—and concerns about the absence of international order. One prominent observer speaks of a “concerted attack on the constitutional liberal order.”

Many of the challenges that concern us today—ethnic nationalisms, building the foundations for peace and prosperity around the globe, managing and containing war, or the future of Europe—were discussed in Paris a hundred years ago. This raises important questions. If we do not have strong international institutions and norms, if great power rivalries continue to lead to trade wars and arms races, are we in danger of a repeat in some form of the 1910s or the 1930s? Do we risk another “unqualified failure” in achieving collective economic goals? Are we destined for war?

Anniversaries impose a misleading unity on a period of history.

We are seeing a resurgence of chauvinistic nationalisms, a revived use of vilification and fear of others, demands for protectionism, and a growing isolationism in the United States. This may well play out, as it has done before, in rivalries and competition among nations. We may, in some cases – take empire, for instance – have concluded too soon that some phenomena are things of the past. While the European and Japanese empires have long since gone, imperialism and multi-national empires still exist, although we have found different terms to describe them.

Yet the circumstances of 2019 are significantly different from those existing in 1919. President Donald Trump appears to be undermining institutions and practices traditionally viewed as hallmarks of US prestige. International society is a more far diverse place than it was one hundred years ago, involving participants who bring along with them a broader range of cultural legacies. And military technology has moved on. It now has the capacity to end the human race.

Empirical shifts in thinking about international relations might mask more profound structural continuity. Others see not similarities but differences and ruptures. Scholars disagree about the meaning of history as it is written, the uses of history for life and politics, and the ways that history shapes behaviour. Thinking about enduring international issues through the prism of the past helps us to better take stock of our world today and our ideas as to where it might be going. To do so is also to help to bridge the divide between political scientists and historians which, while perhaps not a pressing issue for those in the real world – too often prevents those on each side benefitting from the knowledge and analytical tools of the other with consequently deleterious impacts on our understanding of the world we live in.

Featured image credit: ‘Hall of Mirrors’ by yuliu. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post What the Paris Peace Conference can teach us about politics today appeared first on OUPblog.

The Man who Mapped LSD

Albert Hofmann first synthesized LSD on 16 November 1938. it was not until five years later that he would discover its effects, however. Some 75 years ago, on April 19th 1943, he realised the phenomenal effects of LSD first hand. Ingesting 250 micrograms of the compound, he experienced strong sensory and cognitive alterations, which reminded him of mystical episodes of his youth. That was the advent of the modern psychedelic age, which would go on to change society fundamentally.

The fruits of Albert’s work were short-sightedly halted by prohibition in the late 1960s. Now, after a half-century of neglect, the scientific community is once more beginning to pay attention due to evidence of these compounds’ efficacy. Outside of the academy, the possibility that these unfairly maligned substances might be key to tackling the mental health crisis, notably as powerful treatments for anxiety and depression, is starting to permeate public consciousness. As Hofmann’s tireless and diligent work begins to move from the peripheries of social acceptance and into the mainstream, we stand poised to cross over into a golden age of science and research of drugs and psychiatry, reversing the taboos that have held us all back for so many years.

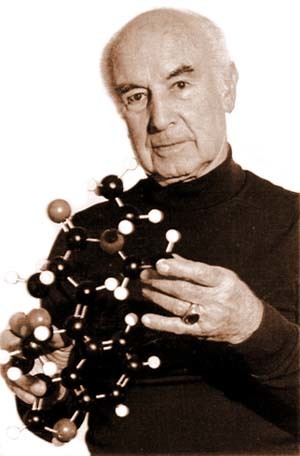

Image credit: Dr. Albert Hofmann and Amanda Feilding, courtesy of the Beckley Foundation.

Image credit: Dr. Albert Hofmann and Amanda Feilding, courtesy of the Beckley Foundation. Image credit: Dr. Albert Hofmann with a model of the LSD molecule, courtesy of the Beckley Foundation.

Image credit: Dr. Albert Hofmann with a model of the LSD molecule, courtesy of the Beckley Foundation.When I first met Albert in the 1990s at a conference in Amsterdam, I thought he was the happiest man I had ever known. Reflecting on my own studies of cerebral circulation, I asked him if he’d ever thought that LSD might increase the overall capillary volume of blood in the brain, and he answered in his humble way that he was “just a little Swiss chemist, not a physiologist.” Since 1966, I had dedicated my life to developing a better understanding of how LSD works so we could better harness its powers to improve the human condition. Through the years, Albert and I developed a firm friendship based on this shared mission.

Following its discovery, there was a burst of scientific excitement for LSD in both medical and therapeutic circles. It was heralded as a wonder-drug in psychiatry, speeding-up and deepening the healing process by overcoming ego defences and accelerating access to psychological trauma so that it could be healthily addressed. The structural similarity between LSD and the neurotransmitter serotonin encouraged the nascent hypothesis that perception and behaviour might be driven by brain chemistry. Between 1943 and 1970, it generated almost 10,000 scientific publications, leading to its description as “the most intensively researched pharmacological substance ever.”

Then, in 1971, after LSD had broken out of the lab and become associated with the anti-draft counterculture, the US government pressed the United Nations to list the compound as a Schedule 1 substance amidst a moral panic. The prohibition of psychedelics and other psychoactive substances became commonplace. Albert’s breakthrough was ringfenced and consigned to the side-lines. Despite its ground-breaking potential, LSD became his “problem child.”

I promised Albert that, for his 100th birthday, I would obtain the first official permissions to carry out scientific research with LSD, and return what should be considered his wonder child to its natural role, an invaluable tool for neuroscience and psychotherapy. We obtained the approvals by his 101st birthday, but sadly, the taboo surrounding LSD continued to needlessly obstruct legitimate research. It was another decade until I was able to commence the world’s first brain-imaging study of LSD in human subjects, through the Beckley/Imperial Research Programme, a collaboration I set up with, and co-direct alongside, Professor David Nutt. The study unlocked the secret principles of psychedelic action: normally well-organised, independent brain networks destabilised and disintegrated, and the segregation between networks dramatically decreased.

Image credit: The first scans of the brain on LSD, courtesy of the Beckley Foundation.

Image credit: The first scans of the brain on LSD, courtesy of the Beckley Foundation.In the peak psychedelic state, there is much greater connectivity between brain regions that usually do not communicate. These altered activity and communication patterns correlated with fundamental changes to experience, such as ego-dissolution, altered meaning, and a more fluid state of consciousness. In 2016, we presented the findings at the Royal Society in London. I thought it was an appropriate place to honour Albert’s legacy.

Our work, and that of organisations like us, is central to a scientific rediscovery of these compounds, that has been christened the psychedelic renaissance. It is still only with great effort and expense that any new study into one of these compounds can be authorised, but the handful of modern investigations so far completed have given us insights into the nature of information processing in the brain, novel theories of psychosis and of consciousness itself, as well as many directions for future research for treating anxiety, anorexia, addiction, PTSD, OCD, depression, opioid dependence, cluster headaches, tinnitus, and several neurodegenerative disorders.

As society moves towards an epidemic of depressive and anxiety disorders, Albert’s work has never been more pertinent. It is heartening that the taboo surrounding mental health issues is dissipating. Let us hope that the taboo surrounding these most promising treatments weakens too, and Albert’s problem child is recognised for the wonderchild it might be.

Featured image credit: “X-t1, fujifilm, fuji” by Viktor Forgacs. Public domain via Unsplash.

The post The Man who Mapped LSD appeared first on OUPblog.

February 11, 2019

Photography and sex in Amos Badertscher’s Baltimore

The Baltimore photographer Amos Badertscher has been cataloguing queer lives in his city since the 1960s: male sex workers and their girlfriends, the 1990s Baltimore and Washington club culture, transgender people, crack and heroin addiction, and the impact of AIDS. His is the largest extant photographic record of the short lives of hustlers (male sex workers) that I know of. Though he could by no means be described as famous, Badertscher enjoyed a brief period of academic notice with the publication of Duke University Press’s Baltimore Portraits in 1999, and his work featured in a 2016 exhibition in the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art in New York. His work is intensely personal. This is no dispassionate chronicle of the sexual life and culture of a major US city.

Image credit: Club Kids, 1999 by Amos Badertscher, Badertscher Collection. Used with permission of Amos Badertscher.

Image credit: Club Kids, 1999 by Amos Badertscher, Badertscher Collection. Used with permission of Amos Badertscher.Club Kids (1999) is merely one in Badertscher’s vast collection of photographs. The central male figure in Club Kids, flanked by his topless female friends, is young, slim, and relatively clean-cut. He appears detached, the object of desire: the other figures in this image (including Badertscher with his Nikon) are attentive, the women with their arms draped around his waist and neck and the blond with her hand resting on his crotch, the centre point of the photograph. Who is the young man? Is this group portrait a fashion shoot, or something else? The female subjects, whose bodies are either turned inward towards the male or hidden behind him, although their breasts are visible, are secondary figures. It is the male’s open, forward-facing stance that invites admiration, which holds the photographer’s attention (eye contact is implied through the mirror used to photograph the group). The posing of the females suggests the male’s heterosexuality; he has his arm around one woman and the other is touching his hand. But the presence of the photographer hints at (perhaps one-sided) same-sex desirability. The man’s youthful masculinity is pivotal. However, so too is the three’s engineered androgyny, the most obvious representation of which comes from their shared wardrobe. All three are wearing baggy jeans with boxer shorts visible above the top of their pants (a classic 1990s American masculine fashion-statement) and the fact that all three are topless. Or does the portrait hint at something more? Bisexuality? Queer sex? Are the two female clubbers lesbians? Are they posing before, or after, group sex? We can probably agree that the image is palpably sexual; while the nature of that sexuality is unresolved, it is unlikely that Badertscher is endorsing heteronormativity. It is a queer historical image within a larger archive of queer history in Baltimore.

When Branka Bogdan (my co-researcher and co-writer on things Badertscher) and I first came across this photograph in Amos’s Baltimore basement studio/office, he explained that it captured a chance encounter with young aficionados of the late 1990s club scene. He met them at a gay pride block party near the city’s famous gay club the Hippo during the summer of 1999. The kids “basically pursued raves in and out of state.” The brief narrative written in hand around the photograph, Badertscher’s trademark, corroborates his astonishing memory about thousands of such interactions. What we also learned was that the photographer was mainly interested in the young man but that he could only persuade him to pose if the young women appeared alongside him. Badertscher was/is extremely attracted to female as well as male androgyny, but in this instance his focus is more on the male. The photographer’s presence within the frame in Club Kids may perhaps seem unusual to those who first encounter his work but is typical of many of the images he took. The photograph is representative not only of this artist’s extensive oeuvre and of his take on urban Baltimore’s street culture, but also of that culture’s constructions of gender and sex.

I have spent considerable time in the archives in the twenty years since my research and writing took a sexual turn. I have encountered the erotic art of the Kinsey Institute (the Institute is pivotal to all sexual histories); The University of Chicago Library’s holdings of the work of 1920s sociologists, mapping the sexual opportunities to be found in the anonymity and freedom of the furnished rooms’ district of Chicago (casual sex before casual sex); the San Francisco History Center’s life course diaries of Lou Sullivan, transitioning from heterosexual woman to gay man; gay masturbatory journals in the New York Public Library that are of such a sexually explicit nature, and name so many people, that they were embargoed for 75 years until I gained special permission to read them; the private archive of the amateur pornographer known as ANONYMOUS who, with a team of straight women, wrote gay male erotic fiction for publication in the 1990s; and the scattered archive of masturbation.

But my favorite archive of all is Amos Badertscher’s intensely intimate, lifetime photographic dossier on Baltimore’s sexual cultures, a supreme example of where today’s personal obsession can become tomorrow’s archive.

Featured image credit: Camera and photographs by congerdesign. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Photography and sex in Amos Badertscher’s Baltimore appeared first on OUPblog.

February 10, 2019

Simone de Beauvoir at the movies

Say you’re an intellectual, a writer. You love going to the movies and are a devoted student of cinematic culture. You also identify as a woman. Over the years, you have had to deal with the fact that the women you see onscreen often appear in the service of male desire; they are meant to be spanked, to be kissed, to oblige and to support men. The rehearsal of this asymmetrical gender dynamic disturbs you, but as a student of cinematic culture, you’ve learned to hold your nose and keep watching to learn the language of film, and in turn the world. You treasure the movies for their unique capacity to frame and reveal truths about the world that are elusive off-screen.

The post Simone de Beauvoir at the movies appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers