Oxford University Press's Blog, page 192

April 26, 2019

In America, trees symbolize both freedom and unfreedom

Extralegal violence committed by white men in the name of patriotism is a founding tradition of the United States. It is unbearably fitting that the original Patriot landmark, the Liberty Tree in Boston, sported a noose, and inspired earliest use of the metaphor “strange fruit.” The history of the Liberty Tree and a related symbol, the Tree of Slavery, illustrates American entanglements of race and place, nature and nation.

The Liberty Tree was a specific elm (Ulmus americana) in the Province of Massachusetts Bay. It was also a generic designation for political gathering sites throughout the thirteen colonies (mainly in New England, but also notably Charleston and Annapolis). And it was a stylized tree in the form of a “liberty pole,” plus a design element for flags.

In the age of revolution, this emblem had multicultural, transatlantic appeal. The Sons of Liberty in Newport, Rhode Island, appropriated for their cause a sycamore that had previously been used for gatherings by the city’s African population. In Haiti, black revolutionaries enthusiastically adopted liberty poles. Toussaint L’Ouverture’s apocryphal parting words became famous: “In overthrowing me, you have overthrown only the trunk of the tree of negro liberty; but the roots remain; they will push out again, because they are numerous, and go deep into the soil.”

The African tree of liberty was not just metaphorical. From the Caribbean to Brazil to Ecuador-Colombia, maroon communities associated food-producing trees such as tamarind (Tamarindus indica) and pigeon pea (Cajanus cajan) with freedom. A cotton tree (Ceiba pentandra) in the center of Freetown, Sierra Leone, became mnemonically associated with both the slave trade and the homecoming of freed slaves from North America.

Image Credit: “Bostonians Paying the Exciseman, or Tarring and Feathering” by Phillip Dawe. Public Domain via The John Carter Brown Library.

Image Credit: “Bostonians Paying the Exciseman, or Tarring and Feathering” by Phillip Dawe. Public Domain via The John Carter Brown Library.In the antebellum United States, abolitionist newspapers regularly printed toasts and lyrics about the glorious tree that bore the fruit of freedom. But for many white male citizens, the arboreal symbol retained its base meaning—regeneration through violence. Henry Ward Beecher, in a collection of pastoral quotations, captured the idea: “A traitor is good fruit to hang from the boughs of the tree of liberty.” Thomas Jefferson, in private, had voiced a similar sentiment in 1787: “The tree of liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots & tyrants.”

For nineteenth-century Americans, the liberty tree had an obvious inverse, the tree of slavery. Abolitionists portrayed it as an invasive non-native species. Drawing on the Bible, they condemned the plant’s evil fruit. Both antiracists and racists used this metaphor. Depending on political context, the fruit could symbolize corruption, miscegenation, the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, unfree labor—or the mere presence of black people on free soil.

Borrowing from Victorian literature, antislavery Americans warned of the upas tree—verdure deadly to the touch. Originally linked to Java in the colonial imagination, the toxic tree (Antiaris toxicaria) became a trope for the dangers and blights of the so-called torrid zone. Early members of the Republican Party spoke of girdling, uprooting, or felling the poisonous tree of slavery. In the darkness following Reconstruction’s end, Frederick Douglass wrote that “one Upas tree overshadows us all.”

As visual art, the tree of unfreedom only occasionally appeared in nineteenth-century media. The most striking example was cartographic. An 1888 chart by John F. Smith titled Historical Geography attempted to explain U.S. history as two divergent plant growths. The godly “Tree of Liberty” had been planted in (continental-climate) Plymouth in 1620 and its blessings spread straightly westward to the Golden Gate under the arboricultural care of Whigs and Republicans. Concurrently, the devilish “Tree of Slavery” took root in (subtropical-climate) Jamestown with the arrival of the first slave ship, and twistingly spread its curses throughout the South. On his politicized map, Smith portrayed the Emancipation Proclamation as a temporal ax.

Did America’s toxic tree ever materialize in woody form? No and yes. There is no Tree of Slavery on the national map—no analogue to the Liberty Tree in Boston‚ an organic monument that, upon death, became a source of relic wood. However, from South Carolina to Texas to Indiana to California, vigilance committees and lynch mobs freely took the lives of out-group members, and then took mementoes from the trees they used as accessories and witnesses to murder.

At root, lynching trees were liberty trees—landmarks of the civic freedom to commit violence in support of white nationalism. They were also vegetal manifestations of toxic masculinity. This dynamic outlived the closing of the frontier and the end of Jim Crow. Timothy McVeigh—a terrorist who considered himself a patriot—owned a T-shirt (now a museum display in Oklahoma City) showing a liberty tree superimposed with Jefferson’s bloody dictum.

In US public memory, lynching is disproportionately associated with the former Confederate states. The privately financed National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama, cries out for complementary sites of truth and reconciliation in every region of the country. If the United States were to fully detoxify its landscapes of memory, Boston, the birthplace of the revolution, could play a role. The Freedom Trail, as designed in the 1950s, excluded the site of the Liberty Tree because the city’s power brokers wanted to steer heritage tourists away from Chinatown and the red-light district Today, one could imagine an extension to a new memorial that encouraged Americans to consider various conjoined growths, past and present, in their republic: freedom and slavery, white liberty and racial terror, boughs and gallows.

Or, returning to Frederick Douglass, if Americans wished to partake of the “tree of knowledge,” they would find its fruits “bitter as well as sweet.”

Featured image credit: Untitled by Adarsh Kummur. Public Domain via Unsplash .

The post In America, trees symbolize both freedom and unfreedom appeared first on OUPblog.

Can the taste of a cheese be copyrighted?

Copyright is an intellectual property right that vests in original works. We know that works like novels, paintings, photographs, sculptures, and songs are examples of what copyright law protects.

But how far can copyright protection go? Can copyright protect, say, a perfume or the taste of a food product?

Unlike more traditional works, which are perceived through senses like sight and hearing – that is, through mechanical senses – perfumes and tastes can be only perceived through chemical senses, such as smell and taste. This makes interpretation of what one is trying to protect potentially complicated.

In the past, courts in France and the Netherlands were indeed asked whether a perfume could be protected by copyright. While the French Supreme Court answered Non! on consideration that the smell of a perfume could not be defined objectively, the Dutch Supreme Court said Ja! and considered that a smell could also be protected by copyright. This in practice has meant that, while in France, perfumers could not rely on the additional protection offered by copyright for the life of the perfumer and 70 years after their death, in the Netherlands perfumers found themselves able to prevent copying of their fragrances by using copyright as a weapon.

Recently, in the Netherlands, the producer of a spreadable cheese, Heks’nkaas, sued a competitor over the marketing of a taste-alike cheese, claiming that – by copying the taste of Heks’nkaas – the defendant had infringed the copyright.

The court in the Netherlands that had to decide the action was unsure whether the taste of a cheese could be protected by copyright, so it asked the Court of Justice of the European Union to clarify this point. The court said that, in order to be considered a work and thus be eligible for copyright protection, the object at issue, the cheese, must be expressed in a manner which makes it identifiable with sufficient precision and objectivity. This requirement is meant to allow both competent authorities (e.g. courts) and interested third parties, (e.g. competitors) to identify – clearly and precisely – the object in respect of which protection is claimed.

It’s very difficult to identify the taste of a food product with precision and objectivity. This makes it different from a literary, pictorial, cinematographic, or musical work, which is a precise and objective form of expression. The taste of a food product, the court said, “will be identified essentially on the basis of taste sensations and experiences, which are subjective and variable since they depend, inter alia, on factors particular to the person tasting the product concerned, such as age, food preferences and consumption habits, as well as on the environment or context in which the product is consumed.”

But the court did not rule out that in the future people may develop systems making it possible to define objectively what a perfume or a taste are, in a way similar to international colour classification codes like Pantone. This means that also these less conventional works might be protectable by copyright.

In addition, the court appeared to suggest that different outcomes, like those occurred in France and the Netherlands in relation to the protection of a perfume, would no longer be possible: the same object must be protected in accordance with the same criteria across Europe. This might have significant implications for those countries, like the United Kingdom, Ireland, Austria, and Cyprus, which only admit copyright protection in a limited number of works. The result has been, for instance, that in the past UK courts have denied protection to the Stormtrooper Helmet from the Star Wars films and the assembly of the scene photographed for the cover of Oasis’s Be Here Now 1997 album. The reason for denying protection was that neither object could be accommodated within one of the eight categories recognized under UK copyright law. After the cheese case things might change, and countries in the EU would need to acknowledge that copyright can subsist even in less conventional objects, insofar as they are works in the sense clarified by the court.

Feature image credit: “Too many to count” by Elisa Michelet. Public domain via Unsplash.

The post Can the taste of a cheese be copyrighted? appeared first on OUPblog.

April 25, 2019

Why Robinson Crusoe is really an urban tale

Robinson Crusoe (1719) was Daniel Defoe’s first novel and remains his most famous: a powerful narrative of isolation and endurance that’s sometimes compared to Faust, Don Quixote or Don Juan for its elemental, mythic quality. Published 300 years ago this month, the work was an immediate popular success, and as one envious rival sneered, “there is not an old Woman that can go to the Price of it, but buys thy Life and Adventures.” It took longer to gain a foothold in the literary canon, in part because of Defoe’s lasting reputation as a political incendiary who had spent several months in prison for seditious libel. But in later generations Robinson Crusoe was championed by Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Walter Scott and others, and its vivid combination of exotic adventure and pious introspection made it a classic for Victorian readers.

We think of Robinson Crusoe above all as a book about solitude and survival. Shipwrecked in a violent storm off the coast of South America, and the sole survivor, Defoe’s hero salvages what he can from the wreckage, and sets about reconstructing a miniature civilization on “this dismal unfortunate Island, which I call’d the Island of Despair.” It’s a slow but successful process, in which Crusoe progresses beyond the desperate foraging of his first days on the island to build a settlement where he cultivates crops, domesticates livestock, and manufactures utensils like pots and lamps. The story may have been inspired by the celebrated case of Alexander Selkirk, a Scottish mariner who survived alone for years after being marooned in the South Pacific. But when finally rescued in 1709, Selkirk had been driven half-mad by his ordeal—“a Man clothed in Goat-Skins, who look’d wilder than the first Owners of them,” his rescuer recalled—and was no longer capable of coherent speech. By contrast with Selkirk, Crusoe thrives, and his elaborately tailored goat-skins, made famous by an iconic frontispiece illustration in the first edition, are a mark of his human triumph over a hostile world.

The Life and Strange Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe

The Life and Strange Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe Defoe resumed these themes of isolation and endurance in his later fiction, but explored them in different worlds. There, as much as in Robinson Crusoe, he writes novels of adverse conditions, personal hardships, and abrupt lurches into disaster, and novels in which the struggle to survive involves its characters in crises that are not only practical but also moral or spiritual. Yet Defoe was also the first great novelist of urban life, and in A Journal of the Plague Year (1722) and Moll Flanders (1722), the struggle plays out in the teeming metropolis of his own experience. H. F., the otherwise unnamed narrator of the Journal, is alone and imperiled on the plague-ridden streets, where “London might well be said to be all in Tears.” Moll Flanders defamiliarizes urban experience in a different but no less compelling way, by imagining a protagonist “without friends, without clothes, without help or helper in the world,” who comes to observe and describe the city from the viewpoint of its criminal underworld. Crime, for Defoe, was never just sin, but something to which we might all be driven, like Crusoe in his doomed ship. As he writes in an astonishing newspaper leader, destitution would make thieves of us all, and worse: “I tell you, Sir, you would not Eat your Neighbours Bread only, but your Neighbour himself, rather than Starve, and your Honesty would all Shipwrack in the Storm of Necessity.”

The language of shipwreck is a striking feature of all these novels, though one Defoe’s narrators tend to evoke during interludes of calm. “Now I seem’d landed in a safe Harbour,” says Moll at one such point. After the plague, as survivors pick up the threads of their lives, H. F. is dismayed to see “People harden’d by the Danger they had been in, like Sea-men after a Storm is over,” not reformed or penitent, but instead “more bold … in their Vices.” There was even a sense, Defoe once suggested, in which Robinson Crusoe, for all its overt exoticism, might be thought of as a novel about urban life. In Serious Reflections During the Life and Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe (1720), a work that teasingly blends Defoe’s authorial identity with that of the fictional Crusoe, he now experiences, he says, “more Solitude in the Middle of the greatest Collection of Mankind in the World, I mean, at London … than ever I could say I enjoy’d in eight and twenty Years Confinement to a desolate Island.” Perhaps Robinson Crusoe was even an “Allegorick History” reflecting his own struggles and dangers in the toxic political environment of a capital city; perhaps it was no fiction at all, but “one whole Scheme of a real Life … spent in the most wandring desolate and afflicting Circumstances that ever Man went through”—a life in which he too had been “Shipwreck’d often, tho’ More by Land than by Sea.” Like every classic, Robinson Crusoe has many layers, and one of these seemed to lie very close to home.

Featured image credit: Dickey Beach by texaus1. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Why Robinson Crusoe is really an urban tale appeared first on OUPblog.

April 24, 2019

On getting in (and out of?) scrape

Neither words nor idioms reveal their origins to a hurried look, but the problems in dealing with these two areas are different. For example, we say to eat crow. This odd phrase means “to suffer humiliation.” We know what eat means, and we have seen many crows. But the etymology of the relevant words need not bother us. The question rather is: “Who, when, and where, ate crow, and why was it bad”? Note that crow has no article, as in, for example, neither fish nor fowl; it refers to the bird’s flesh. The observation about the lack of the article is not superfluous, because in another idiom, namely, to pluck a crow “to settle a small affair; to disagree,” the article occurs and points to the name of an individual bird. What is so special about crows? By the way, the phrase to pluck a goose also existed. In this case, we have to discover a custom, a rite, or a story behind the “language act” that interests us.

Neither fish nor fowl. Image credit: Lion by Netloop. Pixabay License via Pixabay.

Neither fish nor fowl. Image credit: Lion by Netloop. Pixabay License via Pixabay.One often wonders whether some puzzling word group is indeed an idiom. People used to speak about a dish of tea. Why dish? Is a figurative meaning implied? To knock into a cocked hat: what is wrong with a cocked hat? Some people are fond of adding I don’t think to their statements. Is I don’t think an idiom? Does it have “an origin”? My local patriotism makes me cite Minnesota jog. Is this also an idiom? Not really: this jog is a triangular strip of island one can see on the map of the United States. Yet if you don’t know the answer, guessing will not take you anywhere.

A jogger in Minnesota. Not the same as Minnesota Jog. Image credit: Forest Nature by dominic_winkel. Pixabay License via Pixabay.

A jogger in Minnesota. Not the same as Minnesota Jog. Image credit: Forest Nature by dominic_winkel. Pixabay License via Pixabay.Compare a few more typical questions: according to Cocker “executed with perfection” (who was Cocker?), mad as hatter (did hatters ever go mad?), funny bone (what is so funny about it?), through thick and thin and from pillar to post (who coined those alliterative binomials?), and especially pay through the nose, kick the bucket, and their likes. (You will find special posts devoted to the items highlighted above and below.) My prospective explanatory dictionary of English idioms contains phrases of all kinds. To get into a scrape is one of them. What is a scrape? Obviously, the word denotes an unpleasant situation and should have some connection with scraping, but the problem lies elsewhere. The verb scrape is common, while the noun scrape occurs rarely, and its use sheds little light on the idiom.

What is wrong with a cocked hat? Image credit: Tricorne by Rogers Fund, 1926, Metropolitan Museum of Arts. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

What is wrong with a cocked hat? Image credit: Tricorne by Rogers Fund, 1926, Metropolitan Museum of Arts. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.To be sure, similar difficulties arise in the search for word origins. To follow the history of the word bread, we have to know what product was once called “bread” and how people made it. In similar fashion, in order to discover the etymology of bride, a detailed study of marriage rules and rites of the remotest past is needed. But at a certain point, a student of word origins begins to wallow in phonetics and grammar. The science of etymology is at a crossroads of linguistics and culture and needs a researcher versed in countless technicalities, while the history of idioms is mainly an area of culture, and a non-specialist can offer a reasonable hypothesis.

So what is a scrape? The Old English verbs resembling “scrape” were scrapian and screpen. Screpen would have yielded screap, but scrapian looks like a fine etymon for scrape, except that the meaning of the Modern English verb is much closer to that of Old Norse skrapa. Therefore, the English verb is usually believed to be a borrowing from Scandinavian, rather than being a direct continuation of scrapian. We can also say that the English verb modified its meaning under the influence of its northern cognate. Wherever the truth lies, it does not make the origin of the idiom clearer.

I am aware of three worthwhile observations that purport to account for the rise of the metaphor at the bottom of our idiom. 1) From Hamlet’s soliloquy, we remember the phrase there’s the rub. The noun rub occurs in Shakespeare six times, and it has been explained very well indeed: rub “in bowls, an obstacle by which a bowl is hindered in or diverted from its proper course; obstacle (physical or otherwise); unevenness, inequality.” Shakespeare also knew the verb to rub “to encounter an obstacle.” As early as 1853, a correspondent to Notes and Queries cited Shakespeare’s rub as a clue to the phrase get into a scrape. He also mentioned at a pinch (this is the British equivalent of American in a pinch) as having a similar basis. This was a good idea, but, like many other good ideas in etymology, it has been lost.

Beware of rabbit holes. Image credit: Down the Rabbit Hole by John Tenniel. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Beware of rabbit holes. Image credit: Down the Rabbit Hole by John Tenniel. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.2) Robert Chambers in his once famous The Book of Days…(1864) wrote: “There is a game called golf, almost peculiar to Scotland, though also frequently played upon Blackheath, involving the use of a very small hard elastic ball, which is driven from point to point with a variety of wooden and iron clubs. In the north it is played for the most part upon downs (or links) near the sea, where there is usually abundance of rabbits. One of the troubles of the golf-player is the little hole at a burrow; this is commonly called a rabbit’ scrape, or simply a scrape. When the ball gets into a scrape it can scarcely be played. The rules of most golfing fraternities, accordingly, include one indicating what is allowable to the player when hegets into a scrape. Here, and here alone, as is known to the writer has the phrase a direct and intelligible meaning.” Swedish srkapa means, among several other things, “reprimand”; the great lexicographer Edward Lye (1694-1767) was aware of this fact. In 1889, St. Swithin (the pseudonym of Eliza Gutch) quoted the relevant passage from The Book of Days and called into question Hensleigh Wedgwood’s suggestion that “scrape, in the sense of difficulty, is perhaps from the metaphorical sense of Sw. skrapa.” The source of scrape “difficulty” need not delay us here, but it is characteristic that the golf term was at one time current only or mainly in the north. (Incidentally, those interested in the etymology of the word golf may consult the post for July 6, 2011.)

In a scrape. Image credit: Iceland car stuck in river by Roger McLassus. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

In a scrape. Image credit: Iceland car stuck in river by Roger McLassus. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.3) Not only rabbits but also stags make scrapes. Such deer holes are hard to detect, and people break their legs while walking in parks. In an ironic comment on this statement, another correspondent wondered why deer holes should be more dangerous than rabbit holes or cart ruts. We can conclude that a scrape is a scrape (a hole, a rut), and getting into it is dangerous for both balls (golf balls) and legs.

With regard to the origin of the phrase, the OED is noncommittal: “Probably from the notion of being ‘scraped’ in going through a narrow passage.” Yet the reference to a sporting metaphor, reinforced by the analogy of rub, looks attractive.

Featured image credit: Flock by pcdazero. Pixabay License via Pixabay.

The post On getting in (and out of?) scrape appeared first on OUPblog.

Celebrate National Poetry Month with Bernard O’Donoghue

For National Poetry Month, we sat down with Bernard O’Donoghue, author of Poetry: A Very Short Introduction. O’Donoghue discusses the importance of poetry, the influence social media has, and his own process when it comes to writing.

Eleanor Chilvers: Why is poetry important?

Bernard O’Donoghue: Poetry seems to have been thought important in all known societies, often without argument. Poetry is often thought to represent values other than the dominant materialist assumptions of society. It is the principle that Seamus Heaney, one of the foremost modern poets, calls “redress:” restoration of balance with values that are under-represented in a society or culture. This takes it, like other arts, towards recreation rather than practical or material advancement.

EC: What is the importance of poetry in society?

BO: I think it is important that poetry, while representing alternative values in this way, also takes seriously the interests of the society it operates in. Seamus Heaney, quoting the Greek poet-diplomat Giorgos Seferis, said poetry should be “strong enough to help” with the problems faced by society. It will lose its worth and its point if it is confined to pleasing itself. Again, like all the arts, it has a public function. Percy Bysshe Shelley said the “poets were the unacknowledged legislators” for the world. But they must prove their entitlement to such grand claims.

EC: Why is it important to study poetry from an academic perspective?

BO: Again, like the other arts, poetry has formal elements to it. There is no one particular formality it must satisfy, and the forms vary from language to language and society to society. The study of poetry is to observe what the formalities are: the importance of sound for poetry in English, for example. It is often said nowadays that, if you want to write, you must read to find out what the practice of writing is. This applies in a marked way to poetry.

EC: How does the Internet and social media contribute to the well-being of poetry?

BO: The internet is enormously valuable as a repository of existing poetry, and as an explanation of what particular poetic forms are: to define, say, what figures of speech are and how they work rhetorically – what metaphor is, and why it is crucial for poetry as for all language. Social media is useful as a sharing of this kind of knowledge, and for sharing the attempts to write poetry or debate its rules.

EC: What kind of work are you most drawn to reading yourself? Do you read work similar to your own?

BO: I remember the stage of life – in my early teens – when I first started to love poetry: narrative poems like “Flannan Isle” and “The Ancient Mariner.” From them, it was a natural development in the course of studying literature and language in school curricula. I loved Latin poetry as a kind of riddling challenge: how the word-order gave a kind of taste to what was being said. “De Rerum Natura” – concerning of things the nature, and so on. This has led to a special enthusiasm for lyric poems where the weight is on the verbal structure. My preferred reading now is of work very far past my own: of Dante, for example, who seems to incorporate the lyric felicity of short poems with a huge visionary scope. I also like the fact that Dante is a great moral and ideological whole: a vision of the universe with all its component elements. I like poetry which is lyrically expressive and morally conclusive at the same time: like the Anglo-Saxon elegies where narrative eloquence is the basis for a concluding view of the world.

EC: Where do you get your ideas?

BO: I just hope they will come, and mostly they don’t. Most of my poems come from the material of childhood: a tendency which is perhaps accentuated in my case by the fact that my adult life has mostly been lived in the south of England, centred on London, in marked contrast with the rural Irish world of farming childhood.

EC: What’s your process for writing?

BO: I am very unsystematic, I am sorry to say. I never sit down at the desk and work at an extensive task. I have great admiration for writers who embark on a novel or some other extensive form, and keep going at it – maybe for years. How did Joyce keep going through Ulysses? I don’t think I am a dedicated, professional writer at all. I wait for snatches of thought or story and see what I can do with them. “Waiting for the spark from Heaven to fall,” Matthew Arnold said in “The Scholar Gipsy.” And it rarely does. You have to catch it while it’s flying, children used to say when asked to repeat something.

EC: What are you reading right now?

BO: I am reading a remarkable novel by an ex-student of mine, Omar Robert Hamilton, called The City Always Wins about the Egyptian revolution of 2011-12 and its brutal suppression. It is classically art that attempts to help. Poetry too can express the public as well as the personal. I always have more than one book on the go of course. I am translating “Piers Plowman” at the moment – slowly – and I fall back on that very happily. Social and individual again.

Poetry: A Very Short Introduction by Bernard O’Donoghue is publishing later this year.

Featured image credit: Notebook by cromaconceptovisual. Pixabay License via Pixabay.

The post Celebrate National Poetry Month with Bernard O’Donoghue appeared first on OUPblog.

April 20, 2019

Notre-Dame, a work in progress

At dusk on Monday, April 15th, just in time for the evening news, the world was treated to the horrendous spectacle of uncontrollable flames licking the roof of Notre-Dame cathedral in Paris. The fire spread from a scaffold that had been installed six months earlier for restorations, completely consuming the timber roof with its lead covering and turning the majestic steeple into a tinder box that came crashing down at the church’s crossing. Some observers were quick to compare this dramatic disaster to the terrorist attack on the World Trade Center in New York, but alas there was no one to blame. Buildings with such a large quantity of old wood are quite fragile, and the fire probably began from a short circuit in the electrical equipment serving the scaffolds.

Notre-Dame, located on the Île de la Cité island in the center of Paris, is revered by Parisians as the heart of the city and indeed by many as the heart of France. From its origins in 1163 it has undergone numerous transformations to the point it is difficult to discern what is authentic. During the mid-13th century the architects Jean de Chelles and Pierre de Montreuil revised the original structure, expanding the transept while adding the flying buttresses so that they could remove much of the bearing walls and enlarge the stain-glass windows, similar to their work on St. Denis. The patronage for the windows, which were paid for by competing interest groups and powerful individuals, became a means of achieving status in medieval society.

As the religious center of the city, so poignantly described in Victor Hugo’s The Hunchback of Notre-Dame (1831), the cathedral still attracts intense devotion, quite evident in the reaction to the fire. But as one of the prime symbols of the ancien regime, along with the convents of Cluny and St. Denis, it also attracted popular wrath, and underwent severe damage during the French Revolution, including the guillotining of the statues of the kings on the west façade. After its conversion into a secular building, the original steeple was removed, and for a brief period the interior was used as a wine cellar. It was not reinstated as a church until 1801 for the coronation ceremony of Napoleon I. Inspired by Hugo’s novel, the first modern restoration campaign of the church began in 1844, under the guidance Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc and his partner Jean-Baptiste Lassus. Viollet le-Duc, in the effort to create a harmonious whole, added many new ingredients, including his own version of the steeple, the famous gargoyles, and a statue of himself set in the spire, often criticized as mystifications of the authentic church.

At the time of the fire Notre-Dame was already under restoration with a budget of only 300,000€. Now that the smoke has cleared a gaping hole is finally letting in glorious natural light (as well as rain) and 1,300 tons of charred oak beams are sprawled across the pavement like a work of conceptual art. The post-fire restoration has been estimated at €1 billion (and at least a five-year process). The money has already been pledged, including significant sums from the three wealthiest families in France, the Pinaults, the Arnaults and the Bettencourts, who seem to be trying to outbid each other in the quest for recognition. President Emmanuel Macron has announced that there will be a competition for the reconstruction, and perhaps this will offer the chance to promote a more conscientious rebuilding of Notre-Dame for a new purpose, not as an exhausted religious symbol but as part of a new sustainable agenda, the world’s first Green Cathedral.

Featured image: GodefroyParis [CC BY-SA 4.0], via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Notre-Dame, a work in progress appeared first on OUPblog.

April 18, 2019

Who invented modern democracy?

Did modern democracy start its long career in the North Atlantic? Was it invented by the Americans, the French and the British? The French Revolution certainly helped to inject modern meaning into a term previously chiefly associated with the ancient world, with ancient Greece and republican Rome. In the 1830s the French commentator Alexis de Tocqueville concluded from his trip to the United States that it was possible for a modern state to function as a democracy (in both a political and a social sense)—even though it remained to be seen if what worked in the new world could be made to work in the old. The British establishment was late in embracing democratic rhetoric, retaining reservations well into the twentieth century, but the British model of representative government gave the people some role while holding them in check—which was reassuring for nervous elites elsewhere.

Still, these were only a few strands within a much more widely shared and variegated process of change that unfolded across Europe and the Americas during the nineteenth century. Outside the North Atlantic region, enthusiastic or doubting democrats certainly looked elsewhere for inspiration—but so did the French, Americans and Britons. And creativity was displayed everywhere. During the French revolutionary era, “democracy’ was if anything more enthusiastically celebrated in the Dutch, Swiss and Italian sister republics than in France itself. Spain’s anti-Napoleonic Cadiz constitution—which vested great power in a unicameral legislature, elected on the basis of a wide though indirect franchise—provided a model both for Spain’s American provinces (some of which then shrugged it off as insufficient for their purposes) and also for Portugal, and states in the Italian peninsula. Spain was not unusual in giving rise to a “democratic’ party in the context of the European revolutions of 1848-51, but this party was unusual in surviving those turbulent years. Meanwhile Germans and Poles, rising stars in the nascent international democratic pantheon, won wider recognition—just as later Garibaldi was widely feted. Beyond Europe and its settlements, to be sure, other peoples had their own relevant traditions and practices, though only in later decades were these recast within an explicitly “democratic’ imaginary.

Democracy has many faces and many histories.

The history of democracy is a history of challenges—in America, France and Britain no less than elsewhere. Indeed, challenge was commonly what produced it. “Democracy’ won support when it promised to solve problems to which other solutions could not be found. In southern Europe, a particular challenge was the extent to which power in international affairs was vested in “northern powers’: Britain, France, Austria and Russia. Inhabitants of southern states—in Iberia, Italy and the Balkans—found their opportunities to shape their own destinies limited by the preferences of northern power-brokers. Relative economic backwardness, one cause of this subordination, was recognised as a problem in its own right. Some inhabitants of these states concluded that their governments needed urgently to learn how to harness the patriotism of their peoples.

The Ottoman and Arab world was not untouched by these currents. The word for people or crowd, cumhur/jumhur, was employed for a variety of purposes: to describe popular turbulence but also to characterise republics. Indigenous practices of representation were formalised and reconfigured. In the last quarter of the nineteenth century, variants on the imported word “democracy’ began to be used to characterise local developments, and an Ottoman Parliament very briefly met. If other courses were ultimately followed, that was not because of a lack of local ingredients for parallel experiments, but because different political choices were made.

Democracy’s history is sometimes written teleologically and triumphally—as if now we know the end goal, and the historian’s task is to chart how quickly and effectively different peoples in the world have attained it. But this kind of history teeters on the brink of self-congratulation (not least national self-congratulation). It doesn’t equip us very well to think about how democratic ideas and practices have mutated and continue to mutate, nor to expect democracy’s development to be littered with challenges, sometimes prompting its modification, at other times to its more or less general rejection. Democracy has many faces and many histories. We will not know until hindsight tells us from what springs it may be renewed.

Featured image: The Promulgation of the Constitution of 1812. Oil painting by Salvador Viniegra. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Who invented modern democracy? appeared first on OUPblog.

April 17, 2019

Spring gleaning (Spring 2019)

Dream “a vision in sleep” is such a word that a semantic bridge can be built between it and almost anything. That is why for a reasonable hypothesis about the etymology of dream, we need a convincing phonetic match. Otherwise, we’ll be at the mercy of medieval scholars. None of the Greek words beginning with d fulfils the requirement.

In connection with dream, I also received a question about Latin trauma. Indeed, trauma corresponds to Germanic draum– almost letter by letter, but the correspondence of the initial consonants should have been reverse: non-Germanic d versus Germanic t (as in Latin duo~ Engl. two)! So the game is lost before it is begun, and indeed, Greek traûma and Latin trauma have an origin different from that of dream.

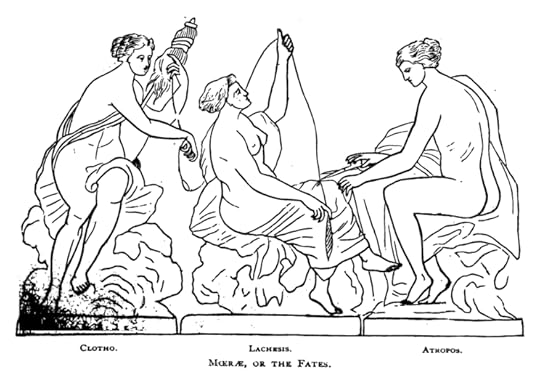

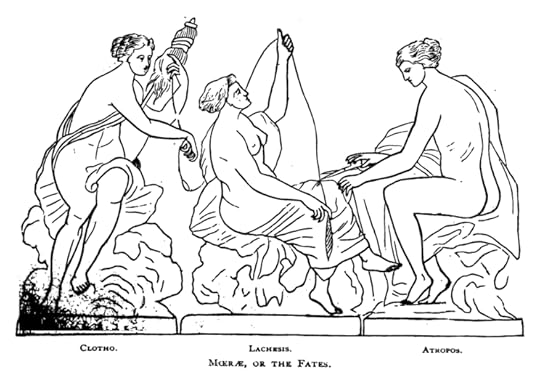

The oldest of the goddesses of fate was Klotho, the primordial spinner. Image credit: “Moirae, or the Fates” by Sarah Amelia Scull. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The oldest of the goddesses of fate was Klotho, the primordial spinner. Image credit: “Moirae, or the Fates” by Sarah Amelia Scull. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Engl. cloth and Greek klōth- “spin”

These words cannot be related because both begin with k, and the Greek word, if it were a cognate of the English one, would have had initial g. I discussed the origin of cloth in the post for August 10, 2016. A very probable cognate of cloth is the Greek root gloi– “sticky.” An extremely old borrowing of this Germanic noun from Greek is out of the question. Also, the oldest cloth was not spun. The Greek word is familiar to those who know myths from the name Klōthó (the last vowel is long), Spinner, the oldest of the three goddesses of fate (Moirai).

Engl. old and Greek aldáino “let grow, rear”

These words do share the same root, which also occurs in Latin alo (compare Engl. alimentary and alimony). The idea of old is “nourished; grown.” Some complications occur only because of the type of word formation, but the comparison is valid (as our correspondent discovered without my help; I can only confirm the validity of his conclusion). The adjective old was once the past participle of a verb meaning “to nourish.”

The etymology of the verb embarrass

I am not a Romance scholar and can only repeat what specialists say on this subject. There is no doubt that the English verb is from French. All the best dictionaries I have consulted state that French borrowed the word from Spanish, which, in turn, borrowed it from Italian, the idea being that the ultimate source is imbarrare “to embar” (“enclose within bars”); hence the figurative sense. But recently, dictionaries, including Meriam Webster online, have begun giving the etymon as Portuguese baraça “noose.” I could not find out who the author of this view is and will be grateful for an explanation.

The latest way to embarrass. Image credit: “Image from page 59 of ‘Biggle horse book : a concise and practical treatise on the horse'” (1895)” by Jacob Biggle, Fairman Rogers Collection. No known copyright restrictions via Flickr.

The latest way to embarrass. Image credit: “Image from page 59 of ‘Biggle horse book : a concise and practical treatise on the horse'” (1895)” by Jacob Biggle, Fairman Rogers Collection. No known copyright restrictions via Flickr.Hebrew shekel

The etymology of shekel is not in question: the word refers to a unit of weight. This word had related forms in Aramaic and Arabic and spread to Greek (síklos~ síglos), from which it made its way to late Latin (siklus) and finally to Old French sicle and from it to Middle English (this word stayed in English until the 18thcentury). But the question was whether Hindi sikka is related. Once again, I should repeat that, not being a specialist, I cannot give a dependable answer, but from what I have seen sikka is neither a borrowing nor an adaptation of shekel.

Our correspondent informed me that he runs an etymology group, and I am pleased to give the address of an ally: http://www.facebook.com/groups/padabeeja.

An ancient shekel. Its name went a long way. Image credit: “Judaea Half Sheke” by Classical Numismatic Group, Inc. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

An ancient shekel. Its name went a long way. Image credit: “Judaea Half Sheke” by Classical Numismatic Group, Inc. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Slang: an etymology

I received a friendly letter from the editor of Online Etymology Dictionary, who has read my hypothesis of the word slang (I am not sure whether he knows the spirited post of September 28, 2016 or a very detailed article in my etymological dictionary) and, in principle, agreed with it. I will first reproduce the explanation in my dictionary and then address his doubts. Both slang “a long narrow piece of land” and slanger “to wander, loaf” have been recorded. The development must have been from “the land, the territory over which people wander” to “those who travel about this territory (first and foremost, hawkers),” further to “the manner of hawkers’ speech,” and to “low class jargon, argot.” The question was about the connection between the territory and the speech used in it. As often happens in semantic reconstruction, the only “proof” is analogy; that is, the existence of a similar case, and in the dictionary I cite such a case: a transition of meaning from “territory” to “language.”

The hypotheses about the etymology of slangare numerous, and I discussed all of them. The reconstruction I support was offered at the end of the nineteenth century, but it was published in a provincial British journal (Cheshire Sheaf) and not noticed. I found a mention of it in a relatively recent article. Few etymologies are final. Yet the progress of senses offered above seems to be convincing. If a better conjecture happens to be found, I’ll be the first to rejoice.

Chippy “prostitute”

I have answered a letter about chippy privately, but it may be of some use to everybody. The word has nothing to do with Chippewa. Words for “prostitute” are sometimes hard to trace to their roots, but most nouns and adjectives sounding as chippy seem to have something to do with chip, even though the connection is often obscure.

Sl-words and the rake’s progress

When I say that many sl– words seem to have symbolic origins, with sl– referring to slime, sleaze and the like, I certainly don’t mean that all such words belong together. Slam, slave, slot, slow, slang, and dozens of others have nothing to do with sound symbolism. The role of sl– was discussed in connection with slut and slattern. A correspondent asked me whether there are masculine analogs of those two words. Words disparaging women’s promiscuity, garrulity, and untidiness are countless, while words pillaring men usually refer to their drunkenness and debauchery. However, rake, libertine, and profligate are there for everybody to see.

Another comment was that sn– words also look as though they stick together. This is certainly true, though snort, sneeze, sniff, sneer, snivel, snigger, snore, snooze, snip, snuff, and one or two more perhaps suggest sound imitation rather than sound symbolism. But then there are snob and snood of undiscovered origin.

Two pence pronounced as tuppence

In Middle English, long vowels were sometimes shortened even in dissyllables. (The shortening in trisyllables is known much better: compare holy and south versus holiday and southern.) This explains the difference in the pronunciation between no and nothing, know and knowledge. A similar case is two pence versus tuppence. Sometimes the quality of the vowel remained the same, and only the length was affected. Foreigners have to learn that the first vowel of sausage is short despite the deceptive spelling. Native speakers acquire the correct pronunciation before they learn to read.

Split personality, or the future of English

From a letter to a student newspaper: “My partner and I have been together for three years. Throughout this time, I’ve seen them switch majors around six times. They bounced from department to department. . . . However, they told me a few months ago that they’ve decided on something for sure. I was excited at first (who doesn’t want their partner to actually understand what they’re going to do” (and so on for about fifteen more lines). We are thrilled. Are you?

Featured image credit: Embarrassed and miserable. “Tiger behind chainlink fence” by David Ramirez. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Spring gleaning (Spring 2019) appeared first on OUPblog.

The last shot at dream

Dream “a vision in sleep” is such a word that a semantic bridge can be built between it and almost anything. That is why for a reasonable hypothesis about the etymology of dream, we need a convincing phonetic match. Otherwise, we’ll be at the mercy of medieval scholars. None of the Greek words beginning with d fulfils the requirement.

In connection with dream, I also received a question about Latin trauma. Indeed, trauma corresponds to Germanic draum– almost letter by letter, but the correspondence of the initial consonants should have been reverse: non-Germanic d versus Germanic t (as in Latin duo~ Engl. two)! So the game is lost before it is begun, and indeed, Greek traûma and Latin trauma have an origin different from that of dream.

The oldest of the goddesses of fate was Klotho, the primordial spinner. Image credit: “Moirae, or the Fates” by Sarah Amelia Scull. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The oldest of the goddesses of fate was Klotho, the primordial spinner. Image credit: “Moirae, or the Fates” by Sarah Amelia Scull. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Engl. cloth and Greek klōth- “spin”

These words cannot be related because both begin with k, and the Greek word, if it were a cognate of the English one, would have had initial g. I discussed the origin of cloth in the post for August 10, 2016. A very probable cognate of cloth is the Greek root gloi– “sticky.” An extremely old borrowing of this Germanic noun from Greek is out of the question. Also, the oldest cloth was not spun. The Greek word is familiar to those who know myths from the name Klōthó (the last vowel is long), Spinner, the oldest of the three goddesses of fate (Moirai).

Engl. old and Greek aldáino “let grow, rear”

These words do share the same root, which also occurs in Latin alo (compare Engl. alimentary and alimony). The idea of old is “nourished; grown.” Some complications occur only because of the type of word formation, but the comparison is valid (as our correspondent discovered without my help; I can only confirm the validity of his conclusion). The adjective old was once the past participle of a verb meaning “to nourish.”

The etymology of the verb embarrass

I am not a Romance scholar and can only repeat what specialists say on this subject. There is no doubt that the English verb is from French. All the best dictionaries I have consulted state that French borrowed the word from Spanish, which, in turn, borrowed it from Italian, the idea being that the ultimate source is imbarrare “to embar” (“enclose within bars”); hence the figurative sense. But recently, dictionaries, including Meriam Webster online, have begun giving the etymon as Portuguese baraça “noose.” I could not find out who the author of this view is and will be grateful for an explanation.

The latest way to embarrass. Image credit: “Image from page 59 of ‘Biggle horse book : a concise and practical treatise on the horse'” (1895)” by Jacob Biggle, Fairman Rogers Collection. No known copyright restrictions via Flickr.

The latest way to embarrass. Image credit: “Image from page 59 of ‘Biggle horse book : a concise and practical treatise on the horse'” (1895)” by Jacob Biggle, Fairman Rogers Collection. No known copyright restrictions via Flickr.Hebrew shekel

The etymology of shekel is not in question: the word refers to a unit of weight. This word had related forms in Aramaic and Arabic and spread to Greek (síklos~ síglos), from which it made its way to late Latin (siklus) and finally to Old French sicle and from it to Middle English (this word stayed in English until the 18thcentury). But the question was whether Hindi sikka is related. Once again, I should repeat that, not being a specialist, I cannot give a dependable answer, but from what I have seen sikka is neither a borrowing nor an adaptation of shekel.

Our correspondent informed me that he runs an etymology group, and I am pleased to give the address of an ally: http://www.facebook.com/groups/padabeeja.

An ancient shekel. Its name went a long way. Image credit: “Judaea Half Sheke” by Classical Numismatic Group, Inc. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

An ancient shekel. Its name went a long way. Image credit: “Judaea Half Sheke” by Classical Numismatic Group, Inc. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Slang: an etymology

I received a friendly letter from the editor of Online Etymology Dictionary, who has read my hypothesis of the word slang (I am not sure whether he knows the spirited post of September 28, 2016 or a very detailed article in my etymological dictionary) and, in principle, agreed with it. I will first reproduce the explanation in my dictionary and then address his doubts. Both slang “a long narrow piece of land” and slanger “to wander, loaf” have been recorded. The development must have been from “the land, the territory over which people wander” to “those who travel about this territory (first and foremost, hawkers),” further to “the manner of hawkers’ speech,” and to “low class jargon, argot.” The question was about the connection between the territory and the speech used in it. As often happens in semantic reconstruction, the only “proof” is analogy; that is, the existence of a similar case, and in the dictionary I cite such a case: a transition of meaning from “territory” to “language.”

The hypotheses about the etymology of slangare numerous, and I discussed all of them. The reconstruction I support was offered at the end of the nineteenth century, but it was published in a provincial British journal (Cheshire Sheaf) and not noticed. I found a mention of it in a relatively recent article. Few etymologies are final. Yet the progress of senses offered above seems to be convincing. If a better conjecture happens to be found, I’ll be the first to rejoice.

Chippy “prostitute”

I have answered a letter about chippy privately, but it may be of some use to everybody. The word has nothing to do with Chippewa. Words for “prostitute” are sometimes hard to trace to their roots, but most nouns and adjectives sounding as chippy seem to have something to do with chip, even though the connection is often obscure.

Sl-words and the rake’s progress

When I say that many sl– words seem to have symbolic origins, with sl– referring to slime, sleaze and the like, I certainly don’t mean that all such words belong together. Slam, slave, slot, slow, slang, and dozens of others have nothing to do with sound symbolism. The role of sl– was discussed in connection with slut and slattern. A correspondent asked me whether there are masculine analogs of those two words. Words disparaging women’s promiscuity, garrulity, and untidiness are countless, while words pillaring men usually refer to their drunkenness and debauchery. However, rake, libertine, and profligate are there for everybody to see.

Another comment was that sn– words also look as though they stick together. This is certainly true, though snort, sneeze, sniff, sneer, snivel, snigger, snore, snooze, snip, snuff, and one or two more perhaps suggest sound imitation rather than sound symbolism. But then there are snob and snood of undiscovered origin.

Two pence pronounced as tuppence

In Middle English, long vowels were sometimes shortened even in dissyllables. (The shortening in trisyllables is known much better: compare holy and south versus holiday and southern.) This explains the difference in the pronunciation between no and nothing, know and knowledge. A similar case is two pence versus tuppence. Sometimes the quality of the vowel remained the same, and only the length was affected. Foreigners have to learn that the first vowel of sausage is short despite the deceptive spelling. Native speakers acquire the correct pronunciation before they learn to read.

Split personality, or the future of English

From a letter to a student newspaper: “My partner and I have been together for three years. Throughout this time, I’ve seen them switch majors around six times. They bounced from department to department. . . . However, they told me a few months ago that they’ve decided on something for sure. I was excited at first (who doesn’t want their partner to actually understand what they’re going to do” (and so on for about fifteen more lines). We are thrilled. Are you?

Featured image credit: Embarrassed and miserable. “Tiger behind chainlink fence” by David Ramirez. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The last shot at dream appeared first on OUPblog.

Explaining Freud’s concept of the uncanny

According to his friend and biographer Ernest Jones, Sigmund Freud was fond regaling him with “strange or uncanny experiences with patients.” Freud had a “particular relish” for such stories.

2019 marks the centenary of the publication of Freud’s essay, “The ‘Uncanny”. Although much has been written on the essay during that time, Freud’s concept of the uncanny is often not well understood. Typically, Freud’s theory of the uncanny is referred to under the heading of “the return of the repressed.” But Freud also offered another, more often overlooked, explanation for why we experience certain phenomena as uncanny. This has to do with the apparent confirmation of “surmounted primitive beliefs.”

According to this theory, we all inherit, both from our individual and collective pasts, certain beliefs in animistic and magical phenomena—such as belief in the existence of spirits—which most of us, Freud thought, have largely, but not totally, surmounted. “As soon as something actually happens in our lives,” Freud wrote, which seems to confirm a surmounted primitive belief, we get a feeling of the uncanny. Not only must the phenomenon be experienced as taking place in reality, however, it must also bring about uncertainty about what is real. As Freud put it, the phenomenon must bring about “a conflict of judgement as to whether things which been ‘surmounted’ and are regarded as incredible may not, after all, be possible.”

Consider some examples. Apparent acts of telepathy and precognition can appear to confirm belief in the omnipotence of thoughts. Waxworks and other highly lifelike human figures can appear to affirm belief in animism—the doctrine that everything is imbued with a living soul.

A remarkable illustration of Freud’s theory can be found in Carl Jung’s autobiography. In 1909, during a meeting between Jung and Freud, Jung “had a curious sensation,” as if his “diaphragm were made of iron and were becoming red-hot—a glowing vault.” “And at that moment,” Jung wrote, there was such a “loud report” that came from the bookcase that was standing next to them that he and Freud “started up in alarm, fearing the thing was going to topple over.” Jung said to Freud: “There, that is an example of a so-called catalytic exteriorization phenomenon.” “Oh come,’” Freud replied. “That is sheer bosh.” “You are mistaken, Herr Professor,” said Jung. “And to prove my point, I now predict that in a moment there will be another such loud report!” Jung wrote that no sooner had said these words “than the same detonation went off in the bookcase.”

“To this day I do not know what gave me this certainty.” Jung wrote. “But I knew beyond all doubt that the report would come again. Freud only stared aghast at me.”

Following the incident, Freud wrote a letter to Jung advising him to keep a “cool head.” Freud was first inclined “to ascribe some meaning” to the noise. But he subsequently made some investigations, and numerous times had observed the same noise coming from the bookcase, yet never in connection with his thoughts. “My credulity,” Freud wrote, “or at least my readiness to believe, vanished along with the spell of your personal presence.”

Freud’s theory of surmounted primitive beliefs provides an explanation for why Freud experienced the sounding bookcase uncanny. It also provides an explanation for why the event had a different effect on Jung. For Freud causal connection between Jung’s thoughts and the noise was impossible. For Jung, it merely affirmed his belief in the reality of the “catalytic exteriorization phenomenon.”

Can this theory of Freud’s be used to explain all uncanny phenomena? This does not seem likely. For a start, one may have qualms about Freud’s characterisation of primitive beliefs. It also does not seem plausible that in order to experience something as uncanny one must first have held and then surmounted a belief in its reality. What if I had never believed in the existence of ghosts, does that mean I cannot experience a ghost-like apparition as uncanny?

Can these problems with Freud’s theory be overcome? That is a task for another occasion.

Featured image credit: “Early morning in NZ” by Tobias Tullius. Public domain via Unsplash .

The post Explaining Freud’s concept of the uncanny appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers