Oxford University Press's Blog, page 189

May 23, 2019

Imitation in literature: inspiration or plagiarism?

Imitation is a complex word with a long and tangled history. Today, it usually carries a negative charge. The Oxford English Dictionary’s second definition of the word is “a copy, an artificial likeness; a thing made to look like something else, which it is not; a counterfeit.” So an imitation of a designer handbag might be a tatty fake.

In the field of literature, at least since the second half of the eighteenth century, the word has acquired a wide range of associations, many of which are negative. An imitation of an earlier text might be no more than a juvenile exercise: John Keats wrote his “Imitation of Spenser” (generally thought to be his first poem) when he was in his teens. As early as 1750, William Lauder claimed to have identified John Milton’s imitations of a number of contemporary Latin poets, and argued that Milton was a textual thief who had stolen most of Paradise Lost from other writers. Ironically, however, Lauder was himself no saint. He had sexed up his list of Milton’s thefts by inserting into Milton’s supposed sources quotations from Latin translations of Paradise Lost. Unsurprisingly, these inserted passages closely resembled passages from Paradise Lost. Today, a writer who accuses another writer of imitating his work is unlikely to mean it as a compliment. He might well be ready to follow up the accusation with a writ.

There is a long-standing association between imitation and plagiarism. This is because an imitation has from the early stages of literary history often been regarded as a work which has a clear and evident verbal debt to an earlier text. The fifth century writer Macrobius discussed at length the ways that Virgil imitated Homer, and sought to defend the Roman author against the charge of stealing from the Greek. The passages he cited were close verbal parallels. After the copyright act of 1709, legal arguments about intellectual property strengthened these long-standing associations between imitation and furtive or unlawful acts of textual appropriation. And once romantic conceptions of originality and creativity were thoroughly embedded in the literary tradition, imitation became generally a dirty word.

These legal and historical forces are too powerful to resist. But they are worth thinking about critically, since they can have a stifling effect on human creativity. They make us nervous about imitating other people or other writers. In the age of copyright, we run the risk of forgetting a key truth about human beings. Everyone learns by imitating other people. Children learn the simplest tasks by observing adults or other children, and replicating their actions. They might do so by direct gestural replication of the person they are imitating, or by grasping what that person appears to be trying to do, and finding an alternative way of realising that end. Either way, they learn by imitation.

Everyone learns by imitating other people.

Literary imitation can be thought about in a similar way. When someone imitates an earlier text, they are not necessarily just taking words from that text. Indeed, the object of literary imitation is usually not simply a sequence of words, but something much more nebulous: a style, or a way of writing. A later author can learn a style from an earlier author—as Keats did from Edmund Spenser, for instance—or a way of structuring sentences, or a stanzaic form. Literary imitation, that is, does not have to be about verbal replication. It can be a means by which writers learn from the past how to do something new.

In the Roman rhetorical tradition, imitation was a good thing. It was how you learnt from an expert earlier orator, how you discovered what kind of writer you might become yourself, and how you equipped yourself with a set of tools which would enable you to address new cases, new circumstances, and new audiences. Imitation had nothing to do with verbal replication. The Roman rhetorical tradition wasn’t simply admirable. Male orators would present themselves as learning from those they imitated ways of fighting and defeating their opponents. Today, that might look like a parody of masculine competitiveness. But that tradition fed into the work of generations of poets right through until the nineteenth century, and it gave our ancestors an understanding of a key point which we risk losing sight of today.

People learn how to do things by closely watching how others do it, by practising the skills they see in others, and by working out new ways of achieving similar outcomes. Literary imitation can be very similar. The pressure to be original and creative and to avoid the stigma of producing “a thing made to look like something else,” puts pressure on writers to avoid dependency on other creative agents. Creativity grows through learning skills from others. We should not regard it as paradoxical to claim that creativity is the product of imitation.

Featured image: “Book background” by Patrick Tomasso. CC0 via Unsplash .

The post Imitation in literature: inspiration or plagiarism? appeared first on OUPblog.

Why climate change could bring more infectious diseases

Human impact on climate and environment is a topic of many discussions and research. While the social, economic, and environmental effects of climate change are important, climate change could also increase the spread of infectious diseases dramatically. Many infectious agents affect humans and animals. Shifts of their habitats or health as a result of climate change and pollution can lead to the spread of infectious diseases.

One of the first signs of climate change is non-typical behaviour of animal populations. Raising temperatures and humidity are favourable for the development of infectious agents. Ticks are transmitters of various infectious diseases which have a seasonal occurrence in temperate regions – from early spring to late fall. Mild winters and humid, warm summers lead to longer times for tick-borne diseases like Lyme disease to develop. Migratory birds are a major vehicle for the spread of infectious diseases. Some of the pathogens can be transmitted directly to humans. Disturbing their migration route thanks to climate change can spread diseases to new territories. Migratory birds can carry ticks, which if have time to develop into adult form, can spread other deadly diseases.

Mosquitoes, which live in the tropical and subtropical areas of the world, carry and transmit a variety of infectious agents like malaria, Zika virus, dengue virus, and West Nile virus. Long-term changes in temperature and rainfall patterns could lead mosquitoes to spread into habitats where they weren’t detected before. The increasing levels of carbon dioxide and temperatures trigger mosquito expansion and higher rate of transmitting diseases as a result. Migratory birds can also promote the spread of mosquitoes and infectious agents.

The stress of dealing with unusual environmental conditions makes animals that transmit human diseases more susceptible to infections. The stress weakens their immunity, allowing parasites to multiply much easier.

Influenza is a respiratory infection found in all parts of the world. Seasonal disease outbreaks are quite common, but vaccination helps to reduce their occurrence. The nature of the virus makes it difficult to find a universal vaccine so researchers manage infection by adjusting vaccines according predicted global influenza circulation; a change in the environment and virus occurrence would make vaccine prevention much more difficult.

Climate change is already taking lives because of the extreme rainfalls, which lead to flooding and contamination from wastewater treatment facilities. The increasing rain frequency will cause outbreaks that could be impossible to handle, especially if the area is already depleted. Extreme weather can as well affect negatively human immunity and increase human-to-human disease transmissions.

Melting ice caps and glaciers as a result of climate change not only will increase sea level but reveal unknown microorganisms. It’s likely melting ice caps will expose unknown infectious agents.

The information above sounds disturbing, but it’s important not to panic. Climate change is inevitable yet humankind has the tools to reduce its impact. The public and governments should be aware about climate change complexity and prepare. Poor regions need more help with supplies and expertise. We also shouldn’t forget about the importance of taking measures to reduce our environmental impact and reduce climate change. It’s much easier to avoid a catastrophe altogether than to be forced to marshal resources to combat it later on.

Featured image: “Mosquito” by mikadago. Pixabay License via Pixabay.

The post Why climate change could bring more infectious diseases appeared first on OUPblog.

May 22, 2019

Disbanding the etymological League of Nations

Bad and good news should alternate. Last week (Oxford Etymologist, May 15, 2019), we witnessed the denigration of everything that is Dutch. But the devil is not as black as he is painted, and the word Dutch occurs in a few positive contexts. More than a century ago, the English knew the phrase to stoke the Dutchman. It meant “to keep the steam up” and referred to the Flying Dutchman, the fastest train on the Great Western Railway. To be sure, the original Flying Dutchman was a legendary ghost ship that can never make port. Some of our readers may have seen Richard Wagner’s early opera with this title. Despite the terrifying name, the train was the pride and joy of its company.

More problematic is the phrase to put a dutchman in. The meaning of the word dutchman (here it should probably be spelled with small d) is not a mystery. The phrase was used by builders and cabinet-makers when a small piece of wood has to be inserted to make a bad joint good. As far as I can judge, the origin of the strange sense (why dutchman or Dutchman?) remains debatable. Therefore, I’ll refer to what a correspondent to American Notes and Queries (ANQ) suggested in 1889. No online discussion I have consulted mentions it. By the end of the nineteenth century, the phrase put a dutchman in, apparently an Americanism, had been current for quite some time.

The Flying Dutchman in its full glory. Image credit: “GWR 7ft gauge Flying Dutchman” by Trainiac. Public Domain via Flickr.

The Flying Dutchman in its full glory. Image credit: “GWR 7ft gauge Flying Dutchman” by Trainiac. Public Domain via Flickr.In Swabia, old German carpenters and cabinet-makers were known to make use of the expression to put a schwab in (the German version was not given in the note) when fitting joints and mortises very loosely, and then making their work tight and firm by inserting small wedges. (Mortise “a hole or recess cut into a part which is designated to receive a corresponding projection, also called a tenon, on another part, so as to join or lock the parts together.”) “Hence the phrase current among the building fraternity to put a Dutchman in—that is, where a joint does not fit perfectly, to insert a small bit of wood after the German fashion.” If this conjecture has merit, we witness the not uncommon substitution of Dutch for German. Last week, I cited “Pennsylvania Dutch,” the name of a German dialect in the United States, and suggested that one should not be in a hurry to take every problematic use of Dutch for “German.” But here the equation of German with Dutch looks reasonable.

Also, seeing how many people with German roots settled in the United States, we can understand why dutchman was coined in America. In principle, every claim to the American origin of an English word, unless it is the name of a peculiarly American institution or an obvious borrowing from Spanish or some indigenous or African language, should be examined with a measure of disbelief. More than once, it turns out that we are dealing with a local British word, little known “at home” but carried across the ocean and given a new lease on/of life in the colonies. Yet dutchman seems to be a genuine Americanism, though even here further research may make this conclusion invalid.

This is what a dutchman in woodwork looks like. Image credit: “Wooden patch” by Sam Sheffield. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

This is what a dutchman in woodwork looks like. Image credit: “Wooden patch” by Sam Sheffield. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.The Dutch, as we have seen, were a favorite target of ridicule for British speakers. The French fared no better. Out of modesty, I’ll bypass French kiss and French letter and will discuss only the enigmatic locution to take French leave. The earliest citation in the OED online goes back to 1751, while Merriam-Webster, also online, gives 1748, without citing the sentence in question (consequently, the date in Wikipedia should be slightly emended). In any case, it is the fairly recent origin of our phrase, rather than the year of its first occurrence in print, that matters.

The phrase has been discussed in numerous letters to the editor and in dictionaries. The meaning “to leave unobtrusively or without permission” has never been in doubt. Possibly, as we’ll see, “without permission” is at the core of the phrase. But the reference to French remains a puzzle, the more so as the Germans have an exact analog, while the French call it “English leave.” Though Frank Chance, an astute and extremely knowledgeable etymologist, devoted two letters to the phrase (Notes and Queries 7/III, 5-6 and 518), he did not solve the riddle. The not uncommon reference to the Napoleonic wars as the time when the idiom came into being should be dismissed, because, once again to use James A. H. Murray’s favorite expression, it is at odds with chronology: people were known “to take French leave” before Napoleon, who was born in 1769, and, consequently, before the wars. Attempts to connect French in this idiom with free or some words like free should be dismissed as fanciful.

The Flying Dutchman ghost ship. Unlike its steaming namesake, it never existed. Image credit: “The Flying Dutchman” by Louis Michel Eilshemius. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The Flying Dutchman ghost ship. Unlike its steaming namesake, it never existed. Image credit: “The Flying Dutchman” by Louis Michel Eilshemius. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Even though the reference to French/English remains enigmatic, I think the following comment, printed in 1884, may be of some interest: “When a soldier or servant takes ‘French leave’, he, for a time at least, absconds. If one jocularly remark [sic: it is the subjunctive] of something which he is in search of and cannot find, ‘it has taken French leave’, he means that it has been unduly removed, or possibly purloined. When a person is said to take French leave, the phrase invariably presupposes that he is a subordinate, bound to seek leave from a possibly only temporary superior. Its origin probably arose either from the old-fashioned contempt of the English, and especially of the French sailor, for the Frenchman, who was thus taunted for being unexpectedly absent when everything seemed to promise an unpacific [!] ‘meeting’, or from the escapes of French prisoners of war.” Sure enough, in the later usage, especially at school, leave means “permission” rather than “absence.”

I wonder whether the reference to sailors’ language will lead us anywhere. A similar scenario was discussed last week in relation to Dutch courage. English is full of phrases going back to maritime vocabulary. For my prospective dictionary of idioms, my assistants and I looked through dozens of journals whose titles mean nothing today. One periodical among them stands out not only as a forum but also as a fully reliable source of information. I mean The Mariner’s Mirror (its first volume appeared in 1911). To take French leave has not been discussed in its pages, but perhaps the phrase deserves a comment by one of its authors. If our story begins with take French leave, all the others (such as to take English leave and to take Irish leave) are derivative of it.

The end of Napoleon’s campaign in Russia. Our idiom has nothing to do with it. Image credit: “Napoleon’s retreat from Moscow” by Adolph Norten. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The end of Napoleon’s campaign in Russia. Our idiom has nothing to do with it. Image credit: “Napoleon’s retreat from Moscow” by Adolph Norten. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.I planned to finish this essay with Russian roulette, but that would have been too scary.

As many people may still remember, the League of Nations was famous for great expectations and deplorably modest results. Its etymological equivalent is not much more profitable. However, to use the word that describes the backbone of our education, talking about the origin of our vocabulary is great fun.

Time to take French leave.

Featured image: “The Austrian, Christian social politician and Federal Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss addressing the League of Nations in Geneva in 1933” by unknown photographer. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Disbanding the etymological League of Nations appeared first on OUPblog.

May 17, 2019

Is social media a platform for supporting or attacking refugees?

On March 15th 2019, a white nationalist opened fire during Friday prayers, killing fifty Muslims and injuring at least fifty others in two mosques in Christchurch, New Zealand. The attack was the largest mass shooting in New Zealand’s history and came as a shock to the small and remote island nation which generally sees itself as free from the extreme violence and terrorism seen elsewhere in the world. The victims included New Zealand citizens, migrants, and in an extremely cruel twist of fate, Muslim refugees who had fled the war in Syria.

To the horror of many, the attacker used Facebook to live-stream the massacre at Al Noor Mosque. Facebook and YouTube were slow to take down the video. Internet users were still uploading and watching the video several hours after the suspect had been arrested. The video was amplified via Reddit, and users of the far-right message board, 8chan, applauded the attack in real-time. One anonymous poster wrote: “I have never been this happy.”

Facebook, Twitter, and other social media sites have been used repeatedly by white nationalists to attack minorities. The perpetrator was most likely radicalised online, and connected with other white supremacists in Europe. Mainstream social media platforms are frequently used to attack refugees. On Twitter, for example, you can find the following hashtags: #fuckrefugees, #RapeRefugees, #MuslimInvasion, and #NotWelcomeRefugees. Some research has even identified a close, causal link between online hate speech and offline violence targeting refugees.

While social media is often used to attack minorities and refugees, it has also provided a platform to support them. Refugees frequently use social media to navigate their way to Europe and to communicate back home. Advocacy organizations have also used social media in support of refugee rights. In September 2015, the image of dead Syrian toddler Alan Kurdi washed up on the shore of Turkey made front pages across the world. The photograph led thousands to tweet #welcome refugees and take to the streets. In the UK, 38 Degrees initiated an on-line petition demanding local councils accept more refugees, which was signed by 137,000 people. Similar social media campaigns were also active in Austria, Germany, Ireland, Poland, Austria, Canada, the United States, and New Zealand. They mobilised people to take part in vigils, offer a bed, a meal or an English lesson to a refugee. In Australia, for instance, GetUp co-organized vigils across Australia under the hashtag #lightthedark and over 10,000 people attended and urged then Australian Prime Minister Tony Abbott to welcome more refugees.

Nevertheless, there is a need to regulate social media companies to ensure they do not disseminate hate speech or violent attacks. As New Zealand’s prime minster, Jacinda Arden, explained immediately after the attacks: “We cannot simply sit back and accept that these platforms just exist and that what is said on them is not the responsibility of the place where they are published. They are the publisher. Not just the postman.” The Australian government moved quickly to criminalise the “abhorrent violent material” online. New laws, passed in early April, stipulate that social media companies will be obliged to remove this content “expeditiously” or face fines and/or imprisonment. Germany passed similar laws in May 2018 and requires social media companies to remove objectionable material within 24 hours or face fines of up to €50 million.

While social media is often used to attack minorities and refugees, it has also provided a platform to support them.

Critics of these new laws suggest they will limit free speech, be misused by autocrats, and potentially even play into the hands of the far-right. Others have argued politicians must address a deeper and more difficult structural issue: monopoly control of the internet. Yet, even Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerburg has acknowledged the need for global regulation of social media big tech companies. In a Washington Post op-ed he argued that: “Internet companies should be accountable for enforcing standards on harmful content.” He called for an independent body to set the standards of harmful content distribution, and monitor compliance.

New Zealand and France are already taking a leadership role in regulating online hate speech internationally. On May 15th they co-hosted a summit in Paris to encourage tech companies and concerned countries to sign-up to the “Christchurch call,” a pledge to eliminate violent, extremist content online. Since the Christchurch attacks Ardern has been consistently strong on the need to act internationally, while France has already sought innovative ways to regulate. In January 2019 Emmanuel Macron’s government embedded a team of senior civil servants in Facebook to help regulate hate speech online. France is currently the G7 President and in May will also host a G7 digital ministers meeting. This global initiative still faces many challenges – its language will need to be precise and binding to have force. States must not only sign the pledge, but also commit to regulation within their national jurisdiction to enforce it.

Featured Image Credit: “social media” by Pixelkult. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

The post Is social media a platform for supporting or attacking refugees? appeared first on OUPblog.

James Harris, the black scientist who helped discover two elements

The year 2019 is the 150th anniversary of the publication of Russian chemist Dmitri Mendeleev’s Periodic Table. The Periodic Table is a tabular arrangement of all elements. Mendeleev developed it to recognize patterns of the known elements. He also predicted that later scientists would fill in new elements in the gaps of his table. Today’s periodic table now provides a useful framework for analyzing chemical reactions and continues to be widely used in chemistry, nuclear physics, and other sciences.

While many chemists have been involved in the development of the periodic table, some stand out more than others. One such person is James Andrew Harris, the first African American to contribute to the discovery of a new element. Harris’ discoveries took place in the late 1960’s long after Mendeleev published the first periodic table in 1869.

Harris was an essential member of the team at Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory that discovered two previously unknown elements—Element 104, Rutherfordium, detected in 1964, and Element 105, Dubnium, detected in 1970. The first African American scientist to play a key role in the search for new elements, he was once described by a writer for Ebony magazine as a “hip, scientific soul brother.”

Harris was born in Waco, Texas, in 1932 and raised by his mother after his parents divorced. He left Waco to attend high school in Oakland, California, but returned to Texas to study science at Huston-Tillotson College in Austin. After earning a B.S. in chemistry in 1953 and serving in the Army, he confronted the difficulties of finding a job as a black scientist in the Jim Crow era.

When Harris first began looking for a job after graduating with a B.S. in chemistry, he was met with shock and incredulity. It was 1955, and many employers found it hard to believe that an African-American was applying for a job as a chemist.

But he persisted in his search and landed employment in 1955 at Tracerlab, a commercial research laboratory in Richmond, California. Five years later, he accepted a position at the Lawrence Radiation Lab (later renamed Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory), a facility of the Department of Energy operated by the University of California.

There he worked in the Nuclear Chemistry Division as head of the Heavy Isotopes Production Group. His responsibility was to purify and prepare the atomic target materials that would be bombarded with carbon, nitrogen, or other atoms in an accelerator in an effort to create new elements. The purification process was extremely difficult, and Harris was regarded highly for his meticulous work in producing targets of superb quality.

Harris was so respected for this work that his colleagues went on to say that his target was the best ever produced in their laboratory. Harris’ targets allowed for the discoveries of Rutherfordium and Dubnium to occur. They were especially important as they occurred during the Cold War around the same time Russian scientists at the Joint Institute for Nuclear Research were attempting the same work. Both of these elements are considered to be superheavy, meaning that they contain more than 92 protons in their nucleus, and are highly unstable, radioactively decaying so quickly that most stable form of Rutherfordium has a half-life of only 1.3 hours.

After the discovery, Harris continued to work at the Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory where he was active in nuclear research chemistry. He devoted much of his free time to recruiting and supporting young black scientists and engineers, often visiting universities in other states. Harris even worked with elementary school students, particularly in underrepresented communities, to encourage their interest in science. These efforts brought him many awards from civic and professional organizations, including the Urban League and the National Organization for the Professional Advancement of Black Chemists and Chemical Engineers.

Harris had his own trading card from a campaign created by Educational Science Books. The company took the idea of baseball cards and instead made trading cards for scientists, an item that proved to be a great icebreaker for Harris with the children he visited. His commitment led him to be a member of the Big Brothers of America, the Parent-Teachers Association, and the Far West High School Policy Board.

Harris retired from the Lab in 1988. Although his community work continued, most of his time was devoted to family, travel, and golf. Harris, along with his wife, often joined friends all over the United States, the Caribbean, and the Pacific Islands for friendly rounds of golf. He died of a sudden illness in December 2000 at the age of 68. Even with all of his accomplishments, Harris is most remembered by his colleagues for his personal qualities, and for his impact on the periodic table which continues to live on.

Featured image: Smithsonian Institution Archives, Accession 90-105, Image #SIA2008-3327. No Known Copyright Restrictions via Smithsonian Institution Archives.

The post James Harris, the black scientist who helped discover two elements appeared first on OUPblog.

May 16, 2019

Should the people always get what they want from their politicians?

Should we listen to the voice of “the people” or the conviction of their representatives? Britain’s vote to leave the European Union has inspired virulent debate about the answer. Amidst Theresa May’s repeated failure to pass her Brexit deal in the House of Commons this spring, the Prime Minister appealed directly to the frustrations and feelings of the people. “You the public have had enough,” she asserted in a speech of March 20. “You are tired of the political games and the arcane procedural rows,” she continued, adding: “I agree. I am on your side.” Others called for parliament to seize control of the process: to bypass May’s government altogether by passing its own resolutions. In this scenario, MPs would listen not to the public mood but to their own judgment, blocking their ears to the demands of a restive, divided populace.

These divides, pitching politicians against the people, have a deep history. “When a gentleman was fairly and duly returned as the representative of any body of men,” William Baker MP asserted in 1780, “he was then, in the sentiments he might entertain concerning any parliamentary question, or state difficulty, to be governed by no other influence but the dictates of his conviction, and ought not to be directed by any other motive whatever, not even by the injunction of his constituents.” Baker’s adherence to these principles did not in fact go over well with his constituents, a newspaper sketch wryly noted, proving “neither very intelligible nor acceptable to the majority of the electors.”

In his 1774 “Speech to the Electors of Bristol,” Edmund Burke made a celebrated appeal to the superior judgment of MPs. Burke conceded that “it ought to be the happiness and glory of a representative to live in the strictest union, the closest correspondence, and the most unreserved communication with his constituents.” But he was unequivocal about the politician’s role: “Your representative owes you, not his industry only, but his judgment; and he betrays, instead of serving you, if he sacrifices it to your opinion.” In other words, MPs respected their constituents by exercising independence from them.

…amidst the current “global populist insurgency, our duly elected representatives should depend more upon their own judgment and worry less about the uninformed opinion of the masses.

Burke’s speech itself has become bound up in contemporary debates surrounding legislative agency. Quoting these lines from Burke’s speech, James Kirchick concludes that, amidst the current “global populist insurgency, our duly elected representatives should depend more upon their own judgment and worry less about the uninformed opinion of the masses.” On the other hand, writing about Brexit for the right-wing website Breitbart, Jack Montgomery writes that Burke’s Bristol speech “is often used by modern MPs as an excuse to ignore the wishes of their electors.” Montgomery’s article turns instead to Burke’s Thoughts on the Cause of the Present Discontents. The House of Commons, Burke stated in that 1770 pamphlet, “was not instituted to be a control upon the people” but as “a control for the people.” Montgomery quotes Burke’s demands that MPs should have “some consanguinity, some sympathy of nature with their constituents,” rather than that they should “in all cases be wholly untouched by the opinions and feelings of the people out of doors. By this “want of sympathy” Burke concluded “they would cease to be a House of Commons.”

Appeals like those of Baker and Burke belonged to their own period of revolutionary ferment. The seeming incoherence of that moment—“What people, for god’s sake?” a review of Burke’s pamphlet noted in exasperation—might have lessons for our own. Before the electoral reforms of the early nineteenth century, the “parties” of politics were in flux. A pamphlet on the 1720 financial crisis described Members of Parliament joining the “disaffected Party” in response to the stock market crash following the South Sea Bubble. Yet this term applied here not to parties in the more restricted parliamentary sense, but to an expanded assemblage of discontented elements within the nation at large. MPs had aligned themselves with fault lines emerging from below, not partisan lines dictated from on high. The rage of the people determined the shape taken by the parties here, not the other way around.

Recent years have witnessed a global epidemic of disaffection from the political process. Alienation from electoral politics has coupled with an often incendiary populism (not least in the events that brought former Breitbart associate Steve Bannon into the White House). Debates that pitch politicians against the people seem poised to continue. But these are artificial—even undemocratic—distinctions. Burke’s writings and their apparent inconsistencies point instead to the ways that popular discontents were never neatly contained, nor easily separated out from parliamentary will. The exasperated response to Burke (“What people, for God’s sake?”) also points to the slipperiness of this term and its availability to manipulation. We must remain wary about efforts to conscript the people’s rage for monolithic, authoritarian, ethno-nationalist ends. But adopting a deeper historical perspective reminds us that democracy is always messy, shifting and uncertain, open to excluded voices and unsettled feelings. The people, for better and worse, continue to define the parties of politics.

Featured image credit: “Put it to the People” by John Briody. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Should the people always get what they want from their politicians? appeared first on OUPblog.

May 15, 2019

A linguistic League of Nations

Some time ago, a question followed my discussion of sound-symbolic and sound-imitative sl-words (March 13, 2019): “What about slave?” Obviously, as I replied, not all words of a certain phonetic structure belong to the same homogeneous group. Yet ever since, I have been planning to write something about this tricky subject. Slave would not have deserved special attention if it were not so close to Slav. By way of introduction, I decided to devote some space to the use of ethnic names in words and phrases. The examples are trivial, but perhaps some of them will be new to our readers.

An often-discussed adjective of this type is Welsh. Its Old English form was wealh. It referred to Welshmen and Britons, but it also meant “foreigner, stranger” and “slave.” Since the Germanic tribes that invaded Britain in the early Middle Ages fought with the indigenous Celts, those meanings are easy to understand. Yet one wonders why the wise old king Hrothgar, Beowulf’s host in the famous Old English poem, has a wife called Wealh-theo, that is, “foreign slave.” Was she captured as a concubine and attained the status of the queen? Such cases were not too rare.

This is Hrothgar’s gentle and wise wife Wealhtheo[w], as we think she looked like. Image credit: “Queen Wealhtheo[w] as the hostess of the banquet” from the children’s book, Stories of Beowulf, by J. R. Skelton. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

This is Hrothgar’s gentle and wise wife Wealhtheo[w], as we think she looked like. Image credit: “Queen Wealhtheo[w] as the hostess of the banquet” from the children’s book, Stories of Beowulf, by J. R. Skelton. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.As is well-known, walnuts don’t grow on walls. The old form wealh-hnutu means “foreign nut,” and the same first component occurs elsewhere. Perhaps the most interesting compound of this type is wealh-stod “translator, interpreter; a person versed in foreign languages.” If stod had a long vowel (then wealh-stōd), it might be related to the verb stand, with the whole meaning “someone who stood by (while translating from a foreign language),” but this etymology is far from certain. In contrast, the much abused Welsh rabbit poses no problems. The name is a joke: something cheap (and unappetizing) is given the name of an expensive dainty. Such are also Irish lemons, or Irish apricots “potatoes,” Essex lion “veal dish,” and many others. The ineradicable attempt to turn Welsh rabbit into Welsh rare-bit is akin to the famous folk etymology that changes asparagus into sparrow grass. As H. F. Fowler observed, Welsh rabbit is amusing and right, and Welsh rarebit stupid and wrong. (Read his incomparable book Modern English Usage, but take one of the older editions.)

By far, the most common “ethnic” word in English phrases is Dutch. A year ago, I wrote about Dutch uncle. The still current phrase is (if I do something,) I am a Dutchman (= a great fool). According to the traditional explanation, such negative references to Dutch go back to the Anglo-Dutch trade wars, fought mainly in the second half of the seventeenth century, though they spilled over into the eighteen hundreds. The truth of this explanation is not immediately clear. Several idioms with Dutch surfaced in the nineteenth century (even in the second half of it), much too late to be echoes of those conflicts. Why didn’t they become popular at the height of the wars, when they must have been on everybody’s lips? Also, some are so rare (and possibly useless) that even the OED has no citations of them. In 1881, a correspondent to Notes and Queries asked about Dutch month: “What is the origin of this duration of time when it takes the meaning of a long time, as in the following sentence?—‘why, you will be as long as a Dutch month’?” No response followed. It would be nice to answer that question a hundred and forty years after it was asked. The public is expected to contribute to the success of the media. This is what is called “going Dutch.”

This is not asparagus, is it? Image credit: “Nature Grass Bird” by André Chivinski. CC0 Public Domain via pxhere. ‘

This is not asparagus, is it? Image credit: “Nature Grass Bird” by André Chivinski. CC0 Public Domain via pxhere. ‘Double Dutch “unintelligible gibberish” was first recorded in 1876. There is no certainty that Dutch in some such locutions means “German,” as in the name of the dialect called Pennsylvania Dutch, and that such idioms express the traditional animosity of the English toward the Germans (a suggestion along these lines has been made). I am a Dutchman turned up in a printed text in 1843. Surely, Dutchman does not mean “German” in it. Also, in at least some such phrases, German could have been expected! Why this long and steady obsession with the Dutch, rather than the constantly denigrated French, about whom something will be said next week?

One may conjecture that, once Dutch became a derogatory term, it continued to live on and began to be applied to practically anything despicable and mean. Perhaps so. I am not contesting the traditional explanation that goes back to E. Cobham Brewer (if not to some earlier authority), but a note of caution may not be out of place. The OED testifies to the existence of many phrases “often with an opprobrious or derisive application, largely due to the rivalry and enmity between the English and Dutch in the 17th century.” As usual, the difficulty consists not only in establishing the general principle but in tracing each phrase to its origins.

A typical example is the idiom Dutch courage “bravery induced by drinking,” first recorded in 1826. William Platt, a knowledgeable, even if not always reliable, student of many languages, wrote in 1881, that “this is an ironical expression, dating its origins as far back as 1745, and conveys a sneering allusion to the conduct of the Dutch at the battle of Fontenoy [May 11, 1745, fought in the War of the Austrian Succession]. At the commencement of the engagement the onslaught of the English allied army promised victory, but the Dutch betook themselves to an ignominious flight.” The OED remarks, as it often does, that this explanation is at odds with chronology. This damning phrase, probably coined by James A. H. Murray, killed many attractive but unreliable hypotheses.

An anchor left at home. Image credit: “Anchor Old Rusty” by guvo59. Pixabay License via Pixabay.

An anchor left at home. Image credit: “Anchor Old Rusty” by guvo59. Pixabay License via Pixabay.Another most suspicious explanation runs as follows: “In the Dutch wars, it had been observed that the captain of the Hollander’s men-of-war, when they were about to engage with our ships, usually set a hogshead of brandy abroach [“in a condition of letting out a liquid”] afore the mast and bid the men drink…; and our poor seamen felt the force of the brandy to their cost.” The literature on the origin of idioms is full of such anecdotes. It is hard to disprove them, but of course, the venerable law of onus probandi expects the writer to cite some arguments that would make the story credible. Here is another conjecture: “May not this expression have arisen out of the practice, stated to have existed, of making Dutch criminals sentenced to death drunk before hanging or beheading?” How much more useful this explanation would have been, if its author had referred to his source! Where was this practice “stated to have existed”?

Personally, I prefer the following explanation: “I thought everybody knew that ‘Dutch courage’ was a jocular term for a glass of Hollands, when resorted to as a fillip for a faint heart.” My preference means absolutely nothing. (Hollands is Dutch, or Geneva, gin.) Everybody? By the way, fillip is probably a sound-imitative word related to flip! Such is the state of the art. One may read on and discover a phrase like the Dutchman’s anchor at home “an object that would have been useful in this situation, but it was, unfortunately, left at home” and many, many more.

A fillip to a faint heart. Image credit: “Hollandse Graanjenever” by unknown author. CC BY- SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

A fillip to a faint heart. Image credit: “Hollandse Graanjenever” by unknown author. CC BY- SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.To be continued!

Featured image: “Boors Drinking in a Bar” by Adriaen van Ostade, National Gallery of Ireland. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post A linguistic League of Nations appeared first on OUPblog.

Looking at Game of Thrones, in Old Norse

The endtime is coming. The night is very long indeed; sun and moon have vanished. From the east march the frost-giants, bent on the destruction of all that is living. From the south come fiery powers, swords gleaming brightly. A dragon flies overhead. And, terrifyingly, the dead are walking too. Heroes are ready and waiting; representing the best of mankind, they have trained in anticipation of the greatest of battles. Now the two mighty forces lock together in apocalyptic combat. Who will emerge victorious when the fight is over and the sun returns once more?

If you’ve been watching the final season of the HBO TV series Game of Thrones, you may think that you recognise this scenario as the long-anticipated showdown involving the Night King and his army of the dead. Against the elemental power of ice are ranged heroic humans in all their vulnerability and courage, supported by the forces of fire. But, in fact, what underlies the vividly horrifying vision I outline above is not Game of Thrones at all – though the similarities are indeed striking.

No, I’m describing the culmination of the magnificent Old Norse-Icelandic poem, “The Seeress’s Prophecy” (Völuspá), probably composed in the late tenth century and which stands first in the astonishing collection known as the Poetic Edda. Mostly preserved in a single manuscript written in Iceland around 1270, these poems relay much of what we know about Old Norse mythology. They also recount the wildly dramatic history of a single heroic dynasty – the Völsungs, a lineage that is extinguished through its uncompromising adherence to ideas of honour and vengeance and, inevitably, violence.

“The Seeress’s Prophecy” is the answer a prophetic female giantess give to Óðinn, the Norse god of wisdom. He has sought her out to discover, or confirm, his understanding of the distant past – and the unknown, but greatly feared, future – a mission he often undertakes in the mythological poetry. The seeress tells about the creation of the universe, detailing how the earth was raised by the gods up out of the sea, how the gods instituted time, built temples and made golden gaming-pieces, and how dwarfs and humans came to be created. With the beginning of time comes both fate and history; the seeress’s vision grows increasingly darker once it moves beyond the present. For the gods themselves become compromised; one of their number, Loki, finally breaks with them and shows his true loyalties to the gods’ enemies: the giants.

When the mighty wolf, Fenrir, Loki’s monstrous child breaks free, the great cosmic wolves swallow the sun and moon: “one in trollish shape shall be the snatcher of the moon,” says the poem. The frost and fire-giants march, Fenrir the wolf and the Miðgarðs-serpent attack: “the serpent churns the waves, the eagle shrieks in anticipation/ pale-beaked he rips the corpse.” Óðinn and Þórr are slain. Hel’s kingdom empties as the dead march out: “heroes tread the hell-road and the sky splits apart.” The heroes of Valhalla ready themselves to fight – in vain; and the world plunges headlong to its doom:

The sun turns black, land sinks into the sea,

the bright stars vanish from the sky;

steam rises up in the conflagration,

hot flame plays high against heaven itself.

Image credit: “Children of the Forest & Night King cosplayer at the 2017 Con of Thrones” by Gage Skidmore. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

Image credit: “Children of the Forest & Night King cosplayer at the 2017 Con of Thrones” by Gage Skidmore. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.It’s here in “The Seeress’s Prophecy” then that the potent myth of ragna rök, the destruction of the world in searing flame and darkness, first appears. The inescapable apocalypse, the end of human hopes and divine ambition has seized the imaginations of writers, composers and artists ever since the Poetic Edda began to circulate through the rest of Europe, primarily from the later eighteenth century onwards. Onto his saga of the downfall of Siegfried the Dragon-Slayer and his kinsmen by marriage, the Gjukungs, the composer Richard Wagner bolted the tale of the Ring, stolen from the Rhine-maidens and a much grander narrative: that of the downfall of the gods. Götterdämmerung is a name derived from a medieval rewording of ragna rök – the Doom of the Gods, as ragna rökkr – the Twilight of the Gods. Wagner was less interested in battles between giants, gods and monsters, but rather in the ethics of his deities, the equivocation and double-dealing that Wotan (Óðinn) employs to establish Valhalla and to inaugurate a line of heroes. At the end of Wagner’s great opera cycle, Der Ring des Nibelungen, the gods’ palace collapses in flame, the Rhine rises in flood and the old order is swept away.

J. R. R. Tolkien too loved the darkness imagined for the end of the Northern world; he admired the stoic courage that kept humans going in the certain knowledge that one day the dragon must come. Since Tolkien, children’s and young adult authors, such as Joanne Harris and Francesca Simon – and of course Neil Gaiman, in American Gods – have seized upon the ragna rök theme as speaking particularly to the hopes and fears of young people in the postwar world. George R. R. Martin, in A Song of Ice and Fire, and, following him, the Game of Thrones showrunners have also incorporated the larger themes and many smaller details from the Norse endtimes into their vision of the greatest existential threat that humanity could ever face.

Why does the ragna rök myth speak to us so compellingly? There’s the drama of the loss of everything. All that we have ever loved – and hated too – is swept away. Gods and humans know it must come, but they bravely resolve to keep going meanwhile, even in the face of profound hopelessness. And – crucially – the end is not the end. For, in a while, the earth rises up again, green and lovely and the sun’s daughter sets out on her path across the sky. Another generation of gods finds the golden gaming-pieces, lost in the long grass in the earliest age and: “the waterfalls plunge, an eagle soars above them, / over the mountain hunting fish”. Our beautiful world is renewed and cleansed. Can it – and we – do better next time in this bright, new dawn?

If you’d like to hear more about The Poetic Edda, check out our Author Talk with Carolyne Larrington.

Featured image credit: “Battle of the Doomed Gods” by Friedrich Wilhelm Heine (1882). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Looking at Game of Thrones, in Old Norse appeared first on OUPblog.

May 14, 2019

Why banishment was “toleration” in Puritan settlements

Typically, sociologists explain the growth of religious toleration as a result of people demanding religious freedom, ideals supporting tolerance becoming more prevalent, or shifting power relations among religious groups. By any of these accounts, Puritan New England was not a society where religious toleration flourished. Yet, when contrasted to a coterminous Puritan venture on Providence Island, it becomes clear that New England’s orthodox elite did succeed in developing a system to bound, and in turn reduce, religious conflict among themselves. It also becomes clear that this system was durably shaped by New England’s vast (if occupied) territorial frontier.

In 1628, 120 miles east of the coast of Nicaragua, English merchants happened upon a small island suitable for colonization and the production of lucrative crops. Dubbing their venture Providence, backers in England developed the settlement as a Puritan religious and military outpost in the heart of the Spanish West Indies. Like New England, it sent large numbers of English Protestants to the New World in the early 1630s and struggled to establish religious and political institutions during its first decade of settlement. On Providence, religious infighting tore the colony apart. Debates about the location of the Island’s church, the ministers’ authority over expulsion, and the possibility of congregational separation to the mainland, propelled settler revolt. Despite some notable hiccups—for instance, the threat of charismatic usurpers like Roger Williams and Anne Hutchinson—New England managed to develop a stable orthodox tradition. By 1641, New England’s leadership could proclaim their settlement an actually existing New Jerusalem. On Providence, after three failed settler revolts, a successful Spanish assault ended the project.

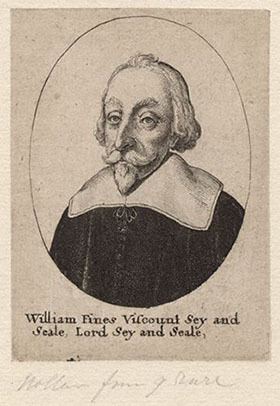

Figure 1 – William Fiennes (Lord Saye and Sele), Prominent Member of the Providence Island Company. Image credit: William Fiennes by Wenceslaus Hollar. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 1 – William Fiennes (Lord Saye and Sele), Prominent Member of the Providence Island Company. Image credit: William Fiennes by Wenceslaus Hollar. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.These differences in religious-state development were crucially shaped by the variation in open space between the two settlements. Providence was a tightly packed and closed space surrounded by water. New England had a vast frontier. Because they had nowhere to send religious dissenters, Providence’s leadership tried to address settler complaints by extending tolerance to religious dissenters, liberalizing property contracts, and expanding settlement to the mainland. At first leaders in Massachusetts adopted a similar approach. During this period, there were intense conflicts around spatial management like those on Providence. But once the frontier was “opened”, these conflicts were defused. New England found itself on a paradoxical trajectory: institutionalized religious intolerance and durable social peace.

Figure 2 – Providence Island Map ca. 1775, Inlay from Thomas Jeffery’s Map of the Island of Roatán. Image Credit: Ruatan or Rattan by Robert Sayer. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 2 – Providence Island Map ca. 1775, Inlay from Thomas Jeffery’s Map of the Island of Roatán. Image Credit: Ruatan or Rattan by Robert Sayer. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.There can be little doubt that New England’s leadership recognized this strategy of toleration by territorial segmentation was facilitated by their geography. Leading New England minister John Cotton put it to dissenter Roger Williams like this, “[b]anishment is a lawful and just punishment: if it be in proper speech a punishment in such a Country as this is, where the Jurisdiction (whence a man is banished) is but small, and the Country round it above it, large, and fruitful…. [B]anishment is not counted so much a confinement, as an enlargement, were a man doth noe so much loose civil comforts, as change them.” Territorial availability legitimated Williams’ expulsion.

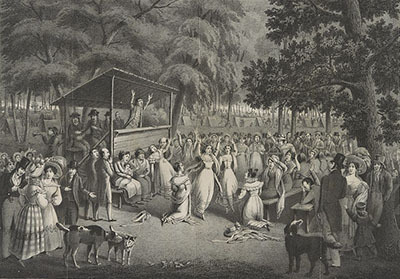

A frontier revival, ca. 1829. Image Credit: Camp Meeting by H. Bridport. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

A frontier revival, ca. 1829. Image Credit: Camp Meeting by H. Bridport. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Scholars today insist that such a system doesn’t reflect true tolerance. Leaders from the Providence venture also chastised New Englanders about their embrace of territorial division to manage religious difference. Writing to Massachusetts Governor John Winthrop they sarcastically asked, “them who daily leave you at the [Massachusetts] Bay and go many miles southward for better accommodations only may you not ask them whether they doubt the work be of God? whether his gracious presence be not amongst you etc.?” If today’s critics emphasize the limitations of an expulsion-centered model of toleration, Providence’s leadership wondered if the sort of religion you could maintain only by removing dissenters was legitimate. According to them, New England’s claim that the expulsion system was “a work of God” were “merely besides this question.”

Ironically, it was the proximity produced by the confines of Providence Island that seem to have caused all the trouble. Unlike Europe – where religious dissenters often found themselves huddled into secret churches outside of public view – New England’s system presented dissenters a means to practice religion publicly and collaborate in decision making. Moreover, by focusing on the benefits of frontier separation, elites could stem religious debate among themselves and also ensure protections against radical forms of Protestant dissent. However onerous such a system was, it had its appeals.

These debates about religious authority and territory are significant because they suggests that regimes of toleration are also shaped by how easy it is to push people out. In the American context, the frontier is typically imagined as barrier to orthodox religious control. However, such accounts miss the opportunities afforded by the frontier for religious state makers. The frontier is not simply the basis of America’s tradition of religious radicalism; it is also the basis of its intolerance.

The post Why banishment was “toleration” in Puritan settlements appeared first on OUPblog.

May 13, 2019

How do we measure the distance to a galaxy and why is it so important?

On March 3, 1912, Henrietta Swan Leavitt made a short contribution to the Harvard College Observatory Circular. With it she laid the foundations of modern Astronomy. Locked in solitude due to her deafness, Leavitt was the first person to discover how to measure distance to galaxies, thus expanding our understanding of the Universe in one giant leap.

Leavitt discovered that the period of oscillation of Cepheid stars, a type of variable stars, is related to their intrinsic brightness. Brighter Cepheids take longer to complete their oscillation cycle. Simply finding Cepheids on other galaxies and measuring their oscillation period would allow one to measure the distance to such objects based on their apparent brightness. Leavitt’s result is so important that it would have earned her a Nobel Prize if it had not been for her premature death.

Leavitt’s discovery was the first step of what we know today as the cosmic distance ladder, a set of techniques that allows us to measure the distance to objects located millions of light years away. Although the use of Cepheid stars is one of our best tools for measuring distances to nearby galaxies, we cannot always find these variable stars in other galaxies. For this reason, astronomers have been developing multiple (but less secure) alternatives to measure distance to galaxies. One possibility, for example, is to measure the brightness of red giant stars when they reach the brightest phase during their stellar evolution. This happens at a well-defined brightness that is known as the Tip of the Red Giant Branch. This technique gives very precise distances when galaxies are relatively close. However, there are times when the detection of individual stars is at the limit of the capacity of the telescopes. On these occasions, astronomers can resort to other techniques that are based on the variation of brightness from one area to another of the galaxies. As galaxies are made up of individual stars, if we observe relatively small regions of a galaxy we will appreciate that they do not have exactly the same number of stars and therefore their brightness can change from one area to another. The closer the galaxy is, the greater will be the variation from one region to another, since the number of stars observed in the same angular region will be lower. This way of measuring distances is known as surface brightness fluctuation (SBF) technique and it is considered a secondary distance indicator as it is not as reliable as those tools based on individual stars.

Henrietta Swan Leavitt by unknown. Public domain via

Wikimedia Commons

.

Henrietta Swan Leavitt by unknown. Public domain via

Wikimedia Commons

.While astronomers continued to refine their methods of measuring distances to galaxies, a revolution in astronomical imaging techniques was taking place. In recent years, new observation strategies have allowed us to discover galaxies that are thousands of times fainter than the brightness of the night sky in terrestrial observatories. Suddenly, thousands of galaxies with very low surface brightness appeared in images obtained by telescopes. These galaxies have come popular under the name of Ultra Diffuse Galaxies and their ultimate nature is the subject of a very lively debate within astronomers. As with any astronomical object, the first problem posed to astronomers was to measure the distance at which these galaxies are located. The measurement of distance is key if we want to unravel the properties of these newly discovered galaxies.

Of all the galaxies discovered to date, one has generated massive attention: KKS2000 04 (also known as NGC1052-DF2). This galaxy, located in the constellation of Cetus, has aroused much interest because of its apparent absence of dark matter. This is something that is difficult (if not impossible) to understand within the current framework of galaxy formation. The amount of dark matter that we infer in a galaxy depends strongly on the distance at which the object is located. As a general rule, if we incorrectly place the galaxy very far away, scientists measure less dark matter. Using the SBF technique, to measure the distance to KKS2000 04 resulted in a distance of 64 million light years. A galaxy at that distance would represent the first example of a galaxy without dark matter. However, if the galaxy were closer, its content of dark matter would be greater and the object would not be anomalous.

Puzzled by the fact that all the properties of KKS2000 04 that depend on the distance were anomalous (their dark matter content and the brightness of their global clusters), it was important to explore other different distance indicators in addition to the SBF technique. Surprisingly, all the other methods (including the more secure Tip of the Red Giant Branch estimator) agreed on a much closer distance to the galaxy (of only 42 million light years away). With this revised distance, all the properties of the galaxy are normal, and fit well within all the observed trends traced by similar galaxies of low surface brightness. So, what is wrong with the SBF technique? Why does it produce larger distances for ultra-diffuse galaxies like KKS2000 04?

The SBF technique has been so far only explored in bright galaxies, where the density of stars (and therefore their brightness) is very high. These galaxies are very different compared to objects with a very low density of stars such as KKS2000 04. Would that mean that the SBF technique should be revisited when dealing with ultra-diffuse galaxies? New works indicate that this must be the case. In fact, without such a revision for diffuse galaxies, the SBF tool provides greater distances than those at which the object is actually located. This does not mean that the SBF technique cannot be used to measure distances for diffuse galaxies, but rather that it’s time to recalibrate the technique. With the new calibration, adapted to this type of galaxy, the distance to KKS2000 04 coincides among different methods and the problem of the absence of dark matter in this galaxy is solved.

More than 100 years later, heirs to a tradition that began with Henrietta Leavitt, the results of this work show once again the fundamental relevance of having accurate distances to extragalactic objects. For a long time, this has been (and continues to be) one of the most difficult tasks in Astronomy: how to measure the distance to objects we cannot touch.

Featured image credit: Colour composite image of [KKS2000]04 combining F606W and F814W filters with black and white background using g-band very deep imaging from Gemini. The ultra-deep g-band Gemini data reveals a significant brightening of the galaxy in the northern region. © 2019 The Author(s) Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the Royal Astronomical Society

The post How do we measure the distance to a galaxy and why is it so important? appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers