Oxford University Press's Blog, page 185

June 27, 2019

Mad Pride and the end of mental illness

When we think of mental illness we’re likely to recall experiences, behaviours, and psychological states that are bad for the individual: a person with severe depression loses all interest in life; another with anxiety might not be able to leave the house; auditory hallucinations can be terrifying; paranoia can make social interaction impossible; and delusions take the person away from a shared reality. When we describe these experiences and states as illnesses we are acknowledging that it is not wholly within the person’s control to act otherwise. When a person is ill, they really cannot help it. That is why being ill often protects someone from condemnation and, in some cases, garners sympathy.

The view of mental illness just outlined might seem uncontroversial, but in fact mental health activists are challenging it. While it is true that mental illness is often associated with suffering, this is not always bad for the individual; it depends on how the person interprets the experiences. For example, depression, in some traditions, is understood as a pathway to spiritual fulfilment; auditory hallucinations (or voices) are regarded by some activists as avenues to a more complete understanding of one’s self; and manic states (with bipolar disorder) can result in bouts of artistic creativity.

Mad Pride activism goes beyond these challenges and rejects the very notion of mental illness, a notion that implies a disorder or a dysfunction of the mind. In place of it, activists reclaim the term “mad,” deprive it of its negative connotations, and present the diverse phenomena of madness as sources of identity and culture. The concept of mental illness, activists argue, is discriminatory and prevents society from a fuller understanding of madness.

This is not the first time that people have challenged the concept of mental illness. In the 1960s and 1970s, dissident psychiatrists attacked the concept, with Thomas Szasz deriding it as a myth that legitimises the oppression of social deviance, and R. D. Laing describing it as a harmful notion that prevents a proper understanding of the meaning and potential of madness. And over the past two decades, the concept has been carefully dissected and analysed by the re-emerging field of philosophy and psychiatry, only to be found lacking: there is no objective way of determining who or what should fall under this class of phenomena. The challenge from Mad Pride differs from these attempts in two main ways: it comes primarily from people who use mental health services (as opposed to clinicians and academics), and it is not a technical worry about the boundaries of the concept, but a cultural and political challenge to societal views of madness.

It is a peculiar feature of many societies in North Europe and North America that the cultural understanding of experiential, psychological, and behavioural deviance has come to be dominated by medical and psychological models of dysfunction. This was not the case in earlier historical periods in these societies, nor is it the case in other cultures around the world today, for example in the Dakhla Oasis of Egypt where I had conducted field-work in 2009 and 2010. In both cases, the cultural repertoire had/has alternatives to dysfunction, for example in seeing madness as a transformative process that can lead to a distinctive form of wisdom, or as a “dangerous gift” that can allow access to unique knowledge not available through everyday experience. Part of what Mad Pride wants to achieve is to bring these notions back into the culture, and in doing so to resist the near-monopoly of the concept of mental illness over the cultural imagination.

Achieving this is not to going to be easy. To the modern sensibilities of many people, stories about spiritual transformation and esoteric wisdom are hard to grasp. Additionally, no matter how we understand madness, there is no hiding from the fact that phenomena such as delusions, hallucinations, extremes of mood, and loss of control over one’s actions jeopardise someone’s ability to live a fulfilling life. All of this weakens the claim that madness is a source of culture and identity, and not an illness.

Now these are reasonable objections and it is important to attend to them. Note, however, that the way in which they have been framed indicates that engaging with Mad Pride has already led to progress. For once we begin to talk about what makes life fulfilling, we inevitably appeal to evaluative notions such as what we consider good or bad, right or wrong. With this insight in place we can begin to ask the right questions. Do hallucinations always impair a person’s ability to live a fulfilling life, or can they sometimes be useful? Are delusions always bad, or can they be sources of innovation? At what point do changes in mood become extreme, and who should make this judgement? Mad Pride challenges people to think about these questions, and to examine their values and core beliefs in the process.

Are we witnessing the end of mental illness? If by this we are referring to the powerful experiences and the suffering that appear to be part of being human, then the end is not, perhaps even can never be, near. But if by this question we are referring to the end of the dominance of the concept of mental illness on social and professional understandings of madness, then Mad Pride has made a strong case for expanding the cultural repertoire beyond medical and psychological models of illness.

Featured image credit: “Hand holding a sparkler” by Free Photos. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Mad Pride and the end of mental illness appeared first on OUPblog.

June 26, 2019

Seven!

It was not quite by chance that a week ago I embarked on a discussion of numerals (on June 19, the topic was nine). You are reading Post No. 700. Every hundred numbers, I congratulate myself on the progress of the blog. Oxford Etymologist came into existence in early March 2006, and, since a year consists of fifty-two weeks, it takes approximately two twelve months to produce a hundred illustrated essays. This past winter, there was a short break (for some time, the world languished without my contributions, though for no fault of mine); the schedule, it appears, may sometimes be disrupted. In any case, on July 12 and July 19, 2017, I wrote about the words six and hundred. Two summers from now, you may expect an essay on eight.

The number seven has not been neglected in people’s tales and scholarly thought. Don’t we have seven days in a week? The word sennight (that is, “seven nights”) used to mean “week.” In Middle English, the form ended in –nihte, and, according to the general rule, final -e was lost (apocopated). Sennight is hopelessly archaic, but fortnight “two weeks” is still a living word in British English. The Ancient Babylonians identified seven of their gods with the seven planets in the sky (apparently, the number included the sun and the moon, in addition to the five visible planets). All about such things can be easily found on the Internet, but few of our readers will have seen the periodical The Open Court (1887-1936). At one time, my team of volunteers screened the entire set for tidbits on etymology, and that is why I am aware of the article titled “Seven” by the editor Paul Carus (Vol. 15, 1901, 412-27); interesting reading. It too is now available on the Internet, and I will refrain from retelling it, but will add that in Pushkin’s (and Tchaikovsky’s) The Queen of Spades, the fateful cards are three, seven, and ace.

Seven was one of the cards that allowed the protagonist of “The Queen of Spades” to win. What about us, etymologists? Image credit: “‘The Queen of Spades,’ pg 102” by Paul Hardy, “The Strand Magazine.” Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Seven was one of the cards that allowed the protagonist of “The Queen of Spades” to win. What about us, etymologists? Image credit: “‘The Queen of Spades,’ pg 102” by Paul Hardy, “The Strand Magazine.” Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Etymologists are supposed to know why words mean what they do. Few words are more obscure than the names of our first ten numerals. In the post on six, I mentioned the well-known fact that in old days no one needed precise high numbers. Indeed, why should anyone want to mention 61 pigs or 93 horses? We have words like flock, herd, and a great number of others like them. Yet people have ten fingers, and, if we add ten toes to the count, words for the numerals from one to twenty will reflect tangible reality. There does not seem to be any disagreement that all primitive counting was and still is connected with the fingers.

Can you fine the 93rd horse in this herd? Image credit: “Horsemen leading a large number of horses in a ring for sale at a horse fair” by William Henry Simmons. after Rosa Bonheur. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Can you fine the 93rd horse in this herd? Image credit: “Horsemen leading a large number of horses in a ring for sale at a horse fair” by William Henry Simmons. after Rosa Bonheur. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.I’ll borrow some facts from an article to which no one refers, but it is a curious piece and deserves a brief mention. The article bears the title “The Origin of the Names of Numerals.” It appeared in the renowned German philological journal Beiträge zur Kunde der indogermanischen Sprachen [“Contributions to the Study of the Indo-European Languages”], vol. 30, 1906, 223-65. Everything is unusual about it: the text is in English, it is very long, and the author is an American. The signature says: “Caroline T. Stewart. Columbia, Missouri.” From the ever-helpful Internet, I learned that she was a Michigan alumna and in 1905 had the rank of an assistant professor at Columbia, Missouri. A female professor of German in Missouri more than a hundred years ago was certainly not an ordinary phenomenon. She probably sent her entire MA thesis to Germany. The work is learned, but not original, though it contains a few suggestions that must have been her own. Adalbert Bezzenberger, the distinguished editor of the journal, hardly read the whole article. Yet he may have thought that his readers would be curious to know what philologists overseas wrote about Germanic and Indo-European linguistics, even though he could not be ignorant of the contributions by the great American sanskritologist W. Dwight Whitney (1827-1894). More probably, he appreciated Stewart’s footnotes about the systems of counting in the American aboriginal languages. I owe my information in the next paragraph to those footnotes.

William Dwight Whitney, a great American philologist. Image credit: “William Dwight Whitney” by unknown author. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

William Dwight Whitney, a great American philologist. Image credit: “William Dwight Whitney” by unknown author. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.In one of the indigenous dialects of West Washington, the root of the name for “finger” is also used for the word meaning “six.” Some people, it was observed, begin counting with the little finger of the left hand, proceed toward the thumb, which is 5, so that the next thumb will be 6, the first member of the new series—an important finger, perhaps even the finger. Elsewhere, for 5 the left wrist was touched, for 6 the left elbow, for 7 the left shoulder, for 8 the right shoulder, for 9 the left breast, and for 10 the sternum. Frequently, the same word is used for “five” and “hand” or for “five” and “fist.” If six may denote “the finger” and the beginning of the new series, it does not come as a surprise that the word for “seven” is sometimes related to the word for “two.”

We seem to be close to the solution of our own riddle, but, alas, we are not. Not a single English (or, for that matter, Indo-European) numeral resembles any word we need (finger, breast, shoulder, and so forth). The noun finger is also of uncertain origin, and I have doubts that it is akin to the German verb fangen “to catch”: no one “catches” anything with fingers. Fingers are nimble, so that the word finger may be cognate with many Germanic f-verbs meaning “to move briskly back and forth” (this etymology has been suggested, but has anyone noticed it?).

Seven pairs of all clean animals (and not only those) found refuge here. Image credit: “Noah’s Ark” by Edward Hicks, Philadelphia Museum of Art. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Seven pairs of all clean animals (and not only those) found refuge here. Image credit: “Noah’s Ark” by Edward Hicks, Philadelphia Museum of Art. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Another trouble with numerals is that they tend to influence one another. Four and five begin with the same consonant, and so do six and seven. The Gothic word for “eight” (ahtau) ends in au, which is a typical ending of the dual. (Indo-European had not only the singular and the plural but also the dual: “we two,” you two.” The verb had corresponding endings.) It follows that ahtau meant “twice four,” but this fact sheds no light on the origin of four. Finally, and this is the crux of the matter, in the past, numerals were occasionally borrowed from neighboring languages, because they played a prominent role in exchanging goods. There is no certainty that our words have ascertainable Indo-European roots. This disconcerting conclusion may be relevant to the origin of seven.

An often cited example of a borrowed numeral is Russian sorok “40.” Sorok (stress on the first syllable) does not sound like the transparent Slavic compounds for twenty, thirty, fifty, and the rest of them. The idea that sorok is a loanword makes sense. See also the post on eenie-meenie (“Catching someone by the toe”: January 10, 2018). In the Afro-Asiatic world, the word for “seven” resembles our seven, and the most recent theory has it that the Indo-European word is a borrowing. Where, in the Semitic group, the root has a transparent meaning, it denotes “middle finger; prominent finger on the hand.”

Tracing seven to a foreign source is acceptable, but there is a hitch. Though the scholarly literature on the Indo-European and Germanic seven is huge, most of it deals with the word’s phonetic form. The word’s irregularity and the absence of any plausible derivation make the suggestion of borrowing attractive. But Russian sorok is an exception in the series, while in Indo-European, the origin of all the first ten numerals is enigmatic. Should we then agree that all of them are borrowings? In the open court of etymology, the question remains unanswered.

Featured image: “Meeting the Seven Dwarves” by Loren Javier. CC BY-ND 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Seven! appeared first on OUPblog.

Five attitudes of mindfulness for the performing musician

Comedian Jack Benny made famous the old joke, “Pardon me, can you tell me how to get to Carnegie Hall?” The punchline, of course, is “Practice, practice, practice.” And yet, it’s not entirely true.

Musical success does require many hours of repetition, the careful refinement of difficult passages, and a high standard of excellence. It demands intense scrutiny and a highly critical ear. Mistakes are corrected and phrases are fine-tuned until they’re nearly impeccable. Even then, they can always be better. A practice mindset requires striving, achieving, and the curious “divine dissatisfaction” famously articulated by choreographer Martha Graham.

This perspective, however, is limited. The same qualities that fuel a practice session have the potential to derail a performer on stage. In a public performance, we don’t have the luxury of stopping to fix mistakes or hone interpretations. The striving that propelled our rehearsals can suddenly make our performances sound labored, even contrived. Few performers can truly experience a flow state of consciousness when every musical gesture is analyzed.

Mindfulness may be the gentlest and most nuanced of all practices, but it is also perhaps the most powerful.

Perhaps surprisingly, a world-class performance integrates dual mental perspectives. Because these viewpoints are somewhat paradoxical, they can be difficult for musicians to reconcile. In contrast to a practice mindset, a performance mindset allows the performer to release many of her perfectionistic ideals in order to hear herself from the perspective of the average audience member. Through objective awareness, she can perceive the larger picture, which might include the character of the music and her own expressive personality. Listening from this broader perspective requires a performer to surrender a great deal of the criticism and self-judgment on stage that served her so well in practice.

Mindfulness is the mental skill that can help musicians practice the more abstract philosophies of this performance mindset. A trendy synonym for awareness, mindfulness is simply the deliberate and nonjudgmental focus of attention on the thoughts and events of the present moment. The following are five counterintuitive attitudes of mindful awareness that can help self-critical performers adopt a healthy performance mentality.

Non-striving. This attitude implies that we can accomplish a necessary task without effort. When the motor skills required to play a musical instrument are rehearsed to the point of automatic execution, the need to work hard begins to diminish. When we stop exerting and start allowing, our performances can begin to sound more effortless and spontaneous.Nonjudgment. Concerts are rarely note-perfect, and musicians seldom perform free from distractions. When something goes awry (and at some point, it will), we can view the event objectively before moving on. If we can perceive all performance events with the relaxed awareness of an impartial witness, without ascribing positive or negative qualities to them, we may find it easier to stay focused on the task at hand.Acceptance. It’s easier to accept positive events than negative events. Yet, accepting is not necessarily the same as condoning—it is ability to acknowledge the present moment by seeing things as they really are. By the time we recognize that something has happened, whether a missed note or forgotten lyric, that event is already in the past. Acceptance can help us quickly return our attention to the present, making any necessary adjustments.Trust. Few musicians feel as prepared as possible when they walk out onto the stage. The very nature of the performing arts presumes that our preparation could always have been better. By learning to trust our groundwork, talents, and abilities, we can begin to silence the chatter of our hardworking inner judges. Trust allows a musician to direct her focus away from her own self-doubts, and pay closer attention to what she is communicating to an audience.Letting go. It is indeed a paradox to struggle toward the pursuit of artistic excellence, and then let all of that go as we walk out onto the stage. Clinging is sometimes rooted in insecurity. Once we are able to identify our anxieties, frustrations, limitations, and biases, we can learn to detach ourselves from the tyranny of our own thoughts. The realization that we are not our thoughts is a brave step in the direction of mindful awareness.Mindfulness may be the gentlest and most nuanced of all practices, but it is also perhaps the most powerful. If you had told me thirty years ago that acceptance, trust, and non-striving would be my most important mental skills for performance success, I would have laughed you right out of my practice room. I would have enumerated my unfinished tasks, my technical flaws, and other responsibilities that demanded my immediate attention, before politely closing the door. In a culture that celebrates busyness, it is a paradigm shift to experience allowing, trusting, and being. But in that space of present-moment awareness, we can begin to recover our freedom as creative, expressive, joyous musicians.

Featured image credit: “Guitarist in an Art Museum” by Mariya Georgieva. Public domain via Unsplash.

The post Five attitudes of mindfulness for the performing musician appeared first on OUPblog.

June 25, 2019

A visual history of slavery through the lens [slideshow]

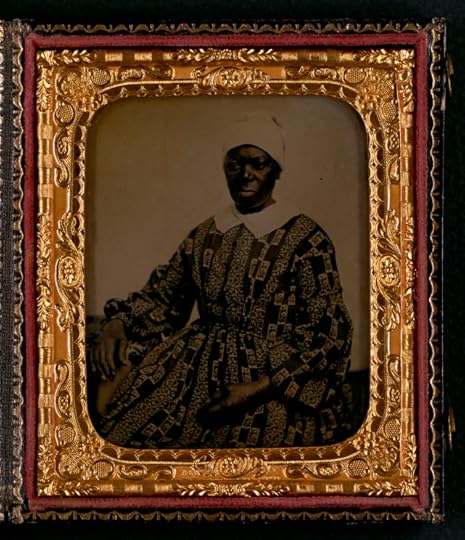

During the 1840s and 1850s, slaveholders began commissioning photographic portraits of enslaved people. Most images portrayed well-dressed subjects and drew upon portraiture conventions of the day, as in the photograph of Mammy Kitty (Figure 1.12), likely enslaved by the Ellis family in Richmond, who placed an arm on a clothed, circular table. Photographs of enslaved people attempted to depict human bondage as a supposedly humane condition. But slaveholders also limited the ways in which enslaved people could express themselves. In the available archive, slaves did not adopt certain poses – including holding portraits of their loved ones (to reveal family ties) and standing on their own (to convey stature) – that free people often used. In this way, photography helped solidify the cultural boundaries between enslaved and free.

Figure 1.12. “Mammy Kitty,” ambrotype, c. 1860. Artist Unknown. Ellis Family Daguerreotypes, Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia.

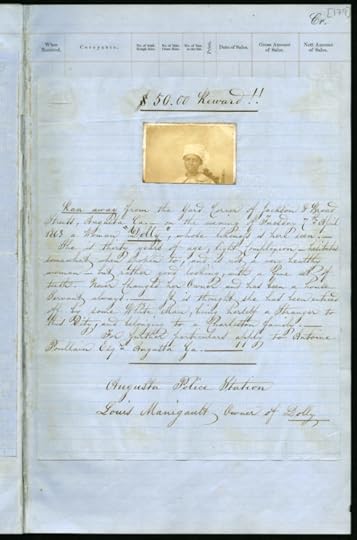

Figure 1.27. Fugitive slave advertisement for Dolly, 1863. Manigault Plantation Journal, p. 179, Manigault Family Papers #484, The Southern Historical Collection, Wilson Library, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

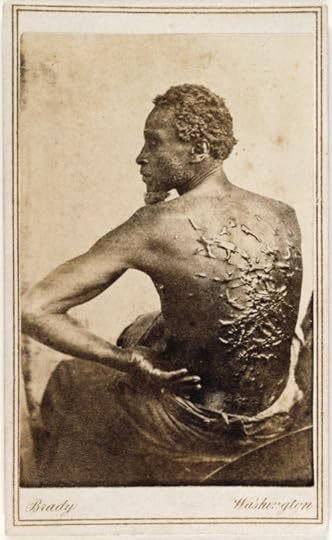

Figure 3.9 Gordon, Artist: Mathew Brady Studio, copy after William D. McPherson and Mr. Oliver, 1863, Albumen silver print, National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

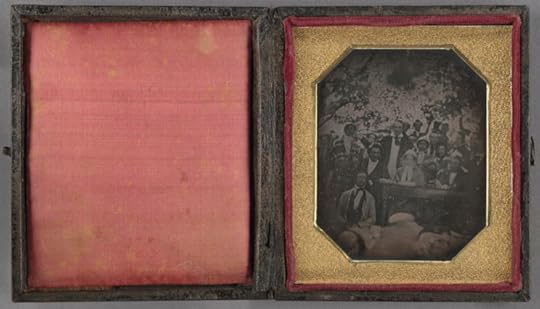

Figure 3.17. Ezra Greenleaf Weld, Fugitive Slave Law Convention, Cazenovia, New York, daguerreotype, August 22, 1850. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program.

Figure 3.23. James Presley Ball, Jesse Berch, quartermaster sergeant, 25, Wisconsin Regiment of Racine, Wis. [and] Frank M. Rockwell, postmaster 22 Wisconsin of Geneva, Wis., carte de visite, 1862. Civil War Collection, Gladstone Collection of African American Photographs, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, LC-DIG-ppmsca-10940.

Figure 4.10 Contraband Foreground, stereograph, Camp Brightwood, D.C., 1861-1865, Artist Unknown. Civil War Photograph Collection, Stereograph Cards Collection, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, LC-DIG-stereo-1s02759.

Figure 4.15. George Barnard, Group portrait of soldiers in front of a tent, possibly at Camp Cameron, Washington, D.C., carte de visite, 1861-1865. Civil War Collection, Gladstone Collection of African American Photographs, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, LC-DIG-ppmsca-11200.

Figure 5.2. Alexander Gardner, Richmond, Virginia. Group of Negroes (‘Freedmen’) by canal, negative, April 1865. Civil War Glass Negatives and Related Prints Collection, Civil War Collection, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, LC-DIG-cwpb-00468.

When Dolly fled bondage in Augusta, Georgia during the Civil War, enslaver Louis Manigault quickly responded, circulating at least two fugitive advertisements with her photographic portrait (a paper carte de visite). Manigault’s ads demonstrate how photography could be used to police enslaved people’s mobility, though in this case, Dolly was never caught (Figure 1.27).

In the spring of 1863, a fugitive man entered Union lines near Baton Rouge and posed with his flagellated back for the camera (Figure 3.9). He was called both Gordon and Peter in the press, and though his identity remains unclear, the significance of the image is abundantly apparent. Copies of The Scourged Back were quickly sent to the North, and soon abolitionists began selling it in their newspapers; at one point in July the National Anti-Slavery Standard even reported its supply had run out. For abolitionists, The Scourged Back confirmed what they had long said about the brutalities of bondage. The image also marked a turning point in abolitionist culture, as photographs began to replace orality as a form of testimony about the conditions of enslavement.[image error]

In August 1850, over two thousand activists gathered to protest the Fugitive Slave Law in Cazenovia, New York. Many of them posed for a group daguerreotype, including Frederick Douglass, Gerrit Smith, and Mary and Emily Edmonson (Figure 3.17). An early protest image and a strikingly interracial scene, the image was also meant to be shared with activist William L. Chaplin, who had recently been jailed for attempting to help enslaved people escape in Washington, D.C.. The image reveals abolitionists’ innovative uses of photography to picture a social movement and to build that movement through the circulation of photographs.[image error]

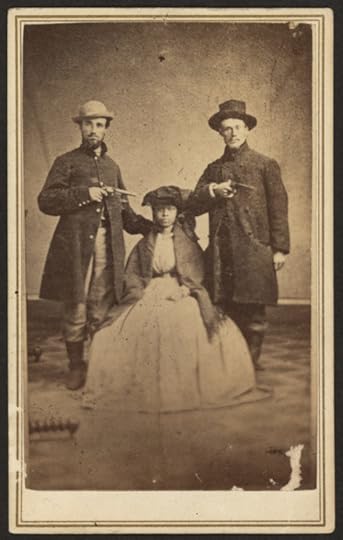

Abolitionists made and shared photographs of fugitives who passed along the Underground Railroad. This image (Figure 3.23), taken in 1862, pictured an unnamed fugitive and two Union soldiers who stopped in Cincinnati on their way northwards to Wisconsin. It was taken by James Presley Ball, a black photographer in Cincinnati, who had operated a studio in the city since 1849.

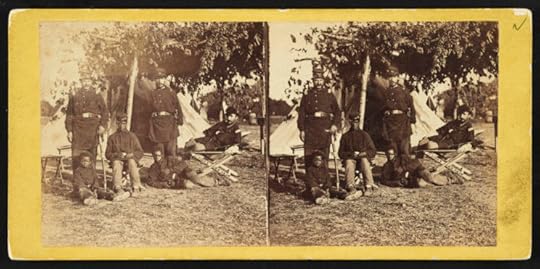

During the Civil War, thousands of white northern soldiers encountered thousands of fugitive enslaved people, who fled bondage and entered Union camps (Figure 4.10). In this context, black people, particularly black men, were pictured in a variety of subordinating poses – including scenes of black subjects sitting before, kneeling beneath, and serving white soldiers (Figure 4.15). These images have often been overlooked in the study of Civil War photography, but evidence suggests that these interracial scenes enabled white soldiers to concretize a vision of racial hierarchy as slavery fell.

Artist Alexander Gardner made this image in Richmond in the spring of 1865, as the war came to an end (Figure 5.2). He pictured ten African Americans at the top of an embankment with a crumbling flour mill in the background. Gardner chose not to publish the image in Gardner’s Photographic Sketch Book of the Civil War (1866), instead picking a photograph from the same location that focused on the decayed cityscape (View on Canal, near Crenshaw’s Mill). In doing so, Gardner stressed southern ruination rather than enslaved liberation.

Featured Image Credit: “Susse Frére Daguerreotype camera 1839” by Liudmila & Nelson. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post A visual history of slavery through the lens [slideshow] appeared first on OUPblog.

June 24, 2019

Using technology to help revitalize indigenous languages

Our planet is home to over 7,000 human languages currently spoken and signed. Yet this unique linguistic diversity—the defining characteristic of our species—is under extreme stress, as are the communities that speak these increasingly endangered languages.

The pressures facing endangered languages are as severe as those recorded by conservation biologists for plants and animals, and in many cases more acute. But linguistic endangerment is by no means a natural or inevitable process. Some of the complex, interrelated processes that result in language loss include presumptuous beliefs about the inevitability and inherent value of monolingualism and networks of global trade languages that are increasingly technologized. Currently, over two thirds of the world’s population speak one of 12 languages as their mother tongue. Such homogenization leaves in its wake a linguistic landscape that is increasingly endangered and fragmented.

The harmful legacy of colonization and the enduring impact of disenfranchising policies relating to indigenous and minority languages are at the heart of language attrition from New Zealand to Hawai’i, and from Canada to Nepal. While some indigenous mother tongues and narrative traditions have received recognition from the United Nations, many more have not and continue to be oppressed in the nation-states in which they are spoken.

In 2016, the United Nations General Assembly adopted a resolution proclaiming 2019 as the International Year of Indigenous Languages to help promote and protect indigenous languages. This celebration of indigenous linguistic vitality and resilience is welcome and timely, but is it enough? Language revitalization is a political act that is rarely just about language and should best be understood as representing broader community goals of self-determination. Successful support structures for language revitalization efforts are ones that acknowledge the context that brought about a language’s de-vitalization in the first place. Meaningful support must therefore affirm the wider goals of the community and not simply focus on the language in a de-contextualized way.

Successful support structures for language revitalization efforts are ones that acknowledge the context that brought about a language’s de-vitalization in the first place.

Indigenous and other historically marginalized speech communities are leveraging new digital tools and technologies in inspiring ways to reclaim their languages and move historically oral traditions into online spaces. Counter to arguments that suggest that TV would kill radio and that the Internet would kill TV, we’re currently in the midst of a radio renaissance. Podcasting and community-based radio are powerful platforms for indigenous communities living both within, and far away from, their traditional homelands. They often have rich archives of tape recordings of elders speaking their languages. The National Māori Radio Network is a group of radio stations in New Zealand that serve the country’s indigenous Māori population. Under their funding agreement from Te Māngai Pāho, the Māori Broadcast Funding Agency, most of these stations must produce programs in the Māori language, and must promote Māori culture actively.

Similarly, Nuxalk Radio is a non-commercial community radio station broadcasting on 91.1 FM from the Nuxalk village of Q’umk’uts, in Western Canada, and worldwide online. Granted a license to operate by the hereditary leadership of the Nuxalk nation in 2014, Nuxalk Radio is explicitly committed to “promoting Nuxalk language use, increase the fluency of semi-fluent Nuxalk language speakers, inspire new Nuxalk language learners, raise the prestige of the Nuxalk language and reaffirm the fact that the Nuxalk language is relevant.” By contributing to physical, mental, spiritual, and emotional well-being of the community, Nuxalk Radio asserts Nuxalk Nationhood.

As indigenous community members know all too well, and as linguists and technologists are quickly learning, Apps and online dictionaries won’t in and of themselves bring a language back. However, such tools can support learners and teachers who will. Some digital tools serve primarily as prestige tools—platforms without reference functionality that have been developed to engage younger people and combat damaging stereotypes of indigenous languages being antiquated or incompatible with modern technology. Other technologies, such as language-specific approximate search and optical character recognition, increase accessibility for language learners and teachers. Further still, cutting-edge technologies like automatic transcription and speech synthesis have shown promise for teachers, curriculum developers, and researchers, helping them to create more resources in less time with fewer people. The most powerful technologies are ones that are mindful of the goals of language revitalizationists and amplify the accessibility and impact of their work.

The post Using technology to help revitalize indigenous languages appeared first on OUPblog.

June 22, 2019

First ladies throughout American history

Attention to the spouse of the president of the United States has been a constant throughout American history, but the role of the first lady has changed over time. The first lady has always been an exemplar of idealized femininity and thus connected to expectations of the role women should play in society. While initially the first lady served primarily as the hostess of the White House, the role gradually expanded to include leading reforms and engaging with the public both domestically and abroad. With the 2020 election nearing and the potential for either a female president or a married gay male president, we’ve decided to take a look back at some past first ladies and their legacies.

Elizabeth Monroe

Elizabeth Monroe Stylish Elizabeth Monroe, dubbed “la belle Américaine” in Paris, aroused considerable envy among her peers in Washington. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Mary Todd Lincoln

Mary Todd Lincoln Mary Todd Lincoln wore an elaborate gown to her husband’s inauguration, and she continued to spend extravagantly on clothes. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Caroline Harrison

Caroline Harrison Caroline Harrison, the second wife of a president to die in the White House, was noted for starting the White House china collection and for helping make a medical school coeducational. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Helen Taft

Helen Taft Helen Taft raised many eyebrows when she broke precedent and rode with her husband to the White House after his inauguration. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Grace Coolidge

Grace Coolidge Popular Grace Coolidge kept several pets and was often photographed with her dogs or her raccoon, Rebecca. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Lou Hoover

Lou Hoover Lou Hoover, the first president’s wife to broadcast from the White House, was an enthusiastic promoter of the Girl Scouts and fitness training for young women. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Eleanor Roosevelt

Eleanor Roosevelt Called “Our Flying First Lady,” Eleanor Roosevelt chose air travel when most Americans refused to try it. Here she is pictured in Dallas, Texas, just weeks after becoming First Lady. Image courtesy of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Library.

Jacqueline Kennedy

Jacqueline Kennedy Jacqueline Kennedy made a poignant appearance at the inauguration of Lyndon Johnson aboard Air Force One less than two hours after her husband’s death. Image courtesy of the Lyndon Baines Johnson Library.

Pat Nixon

Pat Nixon Pat Nixon visited the Great Wall of China during the Nixons’ historic tour of China in 1972. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Nancy Reagan

Nancy Reagan After her first White House year, Nancy Reagan increased her involvement in programs to combat use of illegal drugs. Image courtesy of the Ronald Reagan Library.

Michelle Obama

Michelle Obama As First Lady, Michelle Obama billed herself as mom in chief to two young daughters, but many Americans focused on her fashionable wardrobe and her athleticism. Image courtesy of the White House.

Melania Trump

Melania Trump As the first naturalized citizen to preside over the East Wing of the White House, Melania Trump aroused considerable interest in her wardrobe and style. Image courtesy of the White House.

Featured image: “Executive residence from the South lawn” by Daniel Schwen. CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post First ladies throughout American history appeared first on OUPblog.

June 20, 2019

What biodiversity loss means for our health

Among the great lies I learned in medical school was that a human being was the product of a sperm and an egg. Yes, these gametes are necessary, but they are hardly sufficient to create and sustain a human life. Each one of us stays alive only with the help of trillions of other organisms – the human microbiome – that live on and in every surface of our body exposed to the outside world. Of all the cells that comprise a human body, only two-thirds derive from a sperm and an egg. We can see inklings of what a massive disruption to our relationship with the microorganisms that live within us means to health with the overuse of antibiotics. Antibiotic disruption can foster antimicrobial resistance, weight gain, autoimmune disease, and even perhaps mental health disorders.

Our relationships with other creatures are just as important, especially considering the ongoing and rapid decline in biodiversity. A recent U.N. report emphasized the current rate of species loss is unprecedented in human history and that as many as 1 million species are at risk of extinction. Anyone can quickly discover that life-saving bonds connect us with other species. Take food, as an example. While domesticated food crops are hardly at risk of disappearing, other plants and animals are and can be just as important to keeping us alive.

If your health depends on a medicine, there’s a good chance that the medicine wouldn’t exist had it not been given to us from nature. This is true for medicines that have been around for a long time, such as aspirin and most antibiotics, but also for new ones as well. All told, nearly two-thirds of new drugs approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration between 1981 and 2014 derive in one way or another from natural products. Many of these new drugs, including the anticancer agent trabectedin and pain reliever ziconotide, come from species that depend upon threatened habitats such as mangrove forests and coral reefs. In the ongoing battle against cancer and chronic pain, finding medicines that work in new ways is a major win. The heavy dependence of drug discovery on natural products makes clear that when we lose species, we may kill off potential treatments for presently incurable diseases.

Upheaval in nature also can influence the diseases we may need to treat, especially infections. Many of the fearsome infectious epidemics in recent years have resulted because of altered relationships between people and other life forms. The first known epidemic of Nipah virus, which can kill 80% or more of people infected, occurred in Malaysia in 1999. The epidemic occurred because bats, which harbored the virus, were lured to mango trees planted next to industrial-scale pig farms. The bats, through their feces, infected the pics, and the pigs transmitted the disease to humans. Subsequent epidemics have occurred in other nations from bats contaminating date palm sap collected in buckets that were attached to trees to harvest syrup for human consumption. Another highly lethal virus, rabies, has also been fuelled through disruptions of relationships. Rabies cases in India have been fuelled by a mass die off of vultures. The vultures were poisoned by diclofenac, an anti-inflammatory drug similar to ibuprofen, that the vultures consumed when they fed on dead cattle which had been given the drug to keep them mobile just prior to death. Feral dogs, some of whom had rabies, filled the scavenger void left by the vulture deaths. A broader look at emerging infections shows that about three quarters of emerging infections in recent decades have entered human populations from other animals, and predominantly from wild animals. Humans swim in a common germ pool with other animals. Habitat degradation or outright habitat loss can spur wildlife migrations, and combined with a growing, more urban and mobile human population, can be a recipe for greater disease emergence.

The medical truth is that establishing enough room for nature to thrive and protecting relationships with other species are vital for our health. Of course, not all species benefit humanity but consider that only a few – perhaps a few thousand – out of millions pose any real threat to our own, and the folly of the present extinction spasm, as the preeminent biologist E.O. Wilson calls it, for our own species becomes clear.

Wilson has urged that we set aside half of the earth’s land surface to do this. Only about 15% is protected today. Such an investment in conservation of life on earth may ease pressure on the human-animal encounters that promote infectious epidemics. It also can secure the vast treasure trove of secrets still hidden in life forms known and yet undiscovered that can provide clues to diagnose and treat presently mysterious or incurable diseases. Perhaps above all, though, protecting nature can secure our minds and souls. Abundant evidence confirms what anyone who’s intimately known a piece of nature has known forever: exposure to nature can soothe our minds and provide an irreplaceable sense of belonging to this world.

Featured image credit: “The sun sets over Nature Valley in South Africa.” by redcharlie. Public domain via Unsplash.

The post What biodiversity loss means for our health appeared first on OUPblog.

June 19, 2019

Numerals, especially the number nine, in folklore and language

In fairy tales and legends, most things happen three times. There are three brothers and three daughters; the protagonist faces three trials; only the third attempt brings success; and so forth. According to someone’s joke, ever since Caesar divided Gaul into three parts, everything has been divided in the same way. But perhaps the same would have happened without the opening line of De Bello Gallico (The Gaulic Wars). After all, the boundaries between youth, “midlife” (with or without its crises), and old age are hard to miss. From today’s vantage point, the history of English falls into three periods: Old, Middle, and Modern. German fares no better, but the Scandinavian languages are partly immune to this tripartite tyranny. Most likely, Caesar instinctively followed the pattern that had existed long before him.

Our predilection for twelve goes back to Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia. We still buy a dozen eggs and have twelve hours in the day. Jesus had twelve disciples, and in the Icelandic sagas, a chieftain is usually accompanied by twelve companions. In those tales, the word hundred usually means “long hundred;” that is, 120. Duodecimal counting is familiar to many. Other favorite numerals are sometimes harder to explain. In the Grimms’ tale, there are seven dwarfs, and the wolf attacks seven kids. Likewise, Russian proverbial sayings revolve around seven of everything. American Indian folklore celebrates the number four. But today my topic is “nine.” In the past, I have discussed the odd idiom it takes nine tailors to make a man (April 6, 2016) and nine of diamonds, the curse of Scotland (three posts: November 15, 2017; November 22, 2017, and December 6, 2017). There are quite a few more.

Ninepence, neat and nimble. Image credit: “Post Medieval Siege Piece Ninepence” by The Portable Antiquities Scheme/The Trustees of the British Museum. CC BY-SAY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Ninepence, neat and nimble. Image credit: “Post Medieval Siege Piece Ninepence” by The Portable Antiquities Scheme/The Trustees of the British Museum. CC BY-SAY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Rather instructive is the popularity of the word ninepence. I’ll begin by quoting a passage from John Gough Nichols’s article in the journal Numismatic Chronicle, vol. II, 1840, p. 84, as I found it in The Century Dictionary: “The nine-pence was a coin formerly much favoured by faithful lovers in humble life as a token of their mutual attachment. It was for this purpose broken into two pieces, and each party preserved with care one portion, until, on their meeting again, they hastened to renew their vows.” This custom was in use for centuries. Here is a note from the 1818 edition of Samuel Butler’s Hudibras: “Until the year 1696, when all money not milled was called in, a ninepenny piece of silver was as common as sixpences and shillings, and these ninepences were usually bent, as sixpences commonly are now, which bending was called ‘To my love’ and ‘From my love’; and such ninepences the ordinary fellows gave or sent to their sweethearts as tokens of love.” It is not the first time that I have a chance to refer to Hudibras. It is a very long poem, but reading it “in installments” is sheer delight.

There was (or still is?) the proverbial saying give the old woman her ninepence. Perhaps it suggested that old women also deserve love, but a more prosaic and less sentimental explanation has been offered: “When labourers got a shilling a day the wife got ninepence of it, and the husband retained threepence for his own expenses.” Even so, it is characteristic that the sum of twelve pence (a shilling) was divided into three and nine.

Menshikov, Peter I’s former minion, in exile: a noble brought to ninepence. Image credit: “Menshikov in Berezovo” by Wassilij Iwanowitsch Surikov. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Menshikov, Peter I’s former minion, in exile: a noble brought to ninepence. Image credit: “Menshikov in Berezovo” by Wassilij Iwanowitsch Surikov. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.People said a grand ninepence, a right ninepence, and an easy ninepence, but especially attractive were two alliterative phrases: a neat ninepence and a nimble ninepence. In idioms, the owner of such a valuable coin was sometimes given the name of Nancy. The very triumph of alliteration is the locution to bring a noble to nine-pence and nine-pence to nothing (said about persons living beyond their means). Its variant is his noble has come down to nine-pence, also said about a person who has been brought down in the world, and from a state which in his estimation had been rather an important one. People said so as early as the sixteenth century, and it looks as though some of those phrases do not predate the fifteen sixties. (A word of warning may not be out of place here. When in trouble with the origin of such idioms, don’t be in a hurry to refer ninepence to ninepins: the two have nothing in common.)

My collection contains several other specimens of curious “number phrases,” but I’ll quote only one more (Irish) simile: “As narrow in the nose as a pig at ninepence.” It was recorded in 1862, and I have not seen an explanation for it. The riddle may have a simple solution. In Russian, the pig’s snout is called piatachok (stress on the last syllable), literally, “a five-kopeck coin.” Could the association in English be similar? An equally colorful phrase is the Americanism seven by nine politician. (Never mind Seven of Nine.) In my database, I find the comment to the effect that seven-by-nine is generally applied to a laugh or smile of latitude more than usually benignant, “as if measuring the length and width thereof at the same time playing upon the word benign.” This comment is rather vague. But a 1909 note from Connecticut on a seven by nine politician sounds reliable. The correspondent defined such a person as “a man of too limited abilities, force, or outlook to cut much of any.” The phrase, he added, refers to the old-fashioned windowpanes, before the time when glass filling the whole or half of the sash was common; these were “seven-by nine” in hundreds of thousands of farm or village houses. Similar names were two-cent or two-for-a-cent or huckleberry (whortleberry) politician, the last having the same implication as peanut: one who peddled huckleberries by the quart. Political slang is volatile, and it is no wonder that today an expression common a century ago arouses no associations.

Poor child: Dressed to the nines for the sake of royal etiquette. Image credit: “Infanta Margarita Teresa in a Blue Dress (1659)” by Diego Velázquez. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Poor child: Dressed to the nines for the sake of royal etiquette. Image credit: “Infanta Margarita Teresa in a Blue Dress (1659)” by Diego Velázquez. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Nine is a pervasive element in all kinds of sayings. Some are still known or at least understood, for instance, to be dressed up to the nines. The explanation of the nines as going back to the eyne, that is, “to the eyes,” seems more realistic than the reference to nine Muses, but, sure enough, there were three Graces and nine Muses in the ancient world. In Lancashire, to look nine ways for Sunday used to mean “to be completely at a loss,” and the phrase possession is nine points of the law occurred, according to the OED, as early as 1616. This phrase aroused James A. H. Murray’s special interest (Notes and Queries 10/VII, p. 200). It has been discussed many times since.

Whence, I repeat, this fascination with nine? Why should it have been nine (just nine) days’ wonder? It has been more or less convincingly explained why we are sometimes in seventh heaven, but why on Cloud Nine? The existing conjectures should be taken with a huge grain of salt. Catch 22 has an undisputed origin, to be at sixes and sevens is less clear, and the same holds for most such idioms. If I had nine lives, I might go the whole nine yards and write a comprehensive etymological dictionary of English idioms, but, being pressed for time, I have collected the little that came my way and will present this fruit of my loom to the public in the nearest future.

At sixes ans sevens. Image credit: “Chaos Room” by levelord. Pixabay License via Pixabay.

At sixes ans sevens. Image credit: “Chaos Room” by levelord. Pixabay License via Pixabay.Featured image: “The Nine Muses” by Lodewijk Toeput. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Numerals, especially the number nine, in folklore and language appeared first on OUPblog.

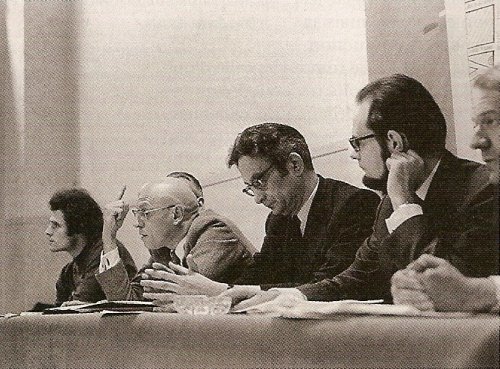

Michel Foucault on the insane, the criminals, and the sexual deviants

Michel Foucault (1926-84) was one of the most influential and notable French philosophers and historians of ideas, best known for his theories on discourses and the relation of power and knowledge. His seminal works such as L’histoire de la folie à l’âge classique (1972, trs. as History of Madness, 2006), Surveiller et punir (1975, trs. as Discipline and Punish, 1977), and Histoire de la sexualité (1976–84, trs. as History of Sexuality, 1979–88) examine the emergence of the powerful, state institutions (penal, scientific, and medical), and their mechanisms of control. They chart western attitudes towards the insane, criminals, and sexual deviants and consider the ways in which societies have penalized those who are outside the norms. Though notoriously difficult, his theories have been ground breaking and applied across a range of disciplines from philosophy, literary criticism, anthropology, sociology, gender studies, and queer theory.

Born in Poitiers, he was educated at the École Normale Supérieure in Paris where he was a student of Louis Althusser and Maurice Merleau-Ponty. He began his teaching career at various European universities in Germany, Sweden, and Algiers in 1950s before returning to France to the chair of philosophy at the University of Clermont-Ferrand and the University of Vincennes in Saint-Denis. He was appointed professor of the history of systems of thought at the prestigious Collège de France in 1970. Politically active from the 1970s onwards, he was the founder of the Groupe d’informaiton sur les prisions (established in collaboration with Jean-Marie Domenach and Pierre Vidal-Naquet for the purpose of distributing information about conditions in French prisons), and often protested on behalf of the marginalised group.

Throughout his career, Foucault was interested in how institutions use science and knowledge as an instrument of power to subjugate humans under the control of the experts. Like Friedrich Nietzsche, Foucault saw knowledge and power as inextricably linked. Folie et déraison (1961, trs. as Madness and Civilization, 1965) or L’histoire de la folie à l’âge classique (1972, trs. as History of Madness, 2006) critique the institution of psychiatry. It is a study of the emergence of the concept of mental illness in Europe, based on his extensive archival research, and expresses his mistrust of the underlying agenda of modern psychiatry. Foucault believed that the medical treatments for the insane, instead of curing and liberating them, were repressive and oppressive, and were ways of controlling challenges to conventional society morality.

Image credit: “Supplice de Robert-François Damiens pour régicide sur la place de la Grève à Paris le 28 mars 1757.” Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: “Supplice de Robert-François Damiens pour régicide sur la place de la Grève à Paris le 28 mars 1757.” Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Out of concern for French penal reform, Foucault examined the changes in penal practices in Surveiller et punir (1975, trs. as Discipline and Punish, 1977). The book charts the shift from the standard executions of the pre-modern era to the creation of the nineteenth-century prison. At the beginning of the book, he recounted the gruesome details of the fate of French soldier, Robert-Francois Damien, who was tortured and torn apart in a horrifying and lurid public spectacle for attempted regicide of King Louis XV. He then juxtaposed this scene with a timetable and list of regulations of a nineteenth century institution for young offenders, where every motion is prescribed and monitored. While recognizing that the modern way of imprisoning criminals was gentler and more humane, he argued that the emergence of modern prison was a mechanism of more effective control. He further argued that these strategies of discipline and confinement became the model for control of an entire society, with factories, schools, and hospitals modelled on the modern prison.

His reputation also rests on Histoire de la sexualité (1976–84, trs. as History of Sexuality, 1979–88), a subversive multi-volume work on various themes of modern sexuality, left incomplete before his death. Foucault was himself a homosexual living in France when it was still not widely accepted. The work is seen as a continuation of the genealogical approach of Surveiller et Punir (1975, trs. as Discipline and Punish, 1977), and showed the intricate links between various modern fields of knowledge about sexuality and the power structures of society. Foucault believed that modern control of sex operates like the modern control of criminals by making sex an object of medical discourse and discursive scientific disciplines.

Image credit: “Conference de presse sur l affaire Jaubert, de gauche à droite: Pierre Laville, Michel Foucault,Claude Mauriac, Denis Langlois et Gilles Deleuze” by Denis Langlois. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: “Conference de presse sur l affaire Jaubert, de gauche à droite: Pierre Laville, Michel Foucault,Claude Mauriac, Denis Langlois et Gilles Deleuze” by Denis Langlois. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Foucault repudiated the view that sexuality was repressed during the Victorian era. He argued that in fact there was a proliferation of new medical, juridical, and psychological discourses concerning sex and obsessive discussions about sex, and these led to the construction of sexual identities, designed to regulate rather than suppress sexuality. Foucault famously put forward the view that the homosexual category did not exist until the 19th century. Although same sex relations have been practiced throughout history, people who practised homosexuality were not classified as homosexuals, and did not think of themselves in terms of sexuality.

In the last few years of his life, Foucault delved into the ancient Roman and Greek texts to look at their perception of sex and pleasures and the emergence of the codes of morality from ancient pagan to early Christianity, L’Usage des plaisirs (1984, trs. as The Use of Pleasure, 1985) and Le Souci de soi (1984, trs. as The Care of the Self, 1985). These last two books marked an important turn in Foucault’s thinking about ethics from the power/knowledge work of the 1970s. They drew on the ancient ideas of the art or the aesthetics of existence, and the philosophy of life focused on “the care of the self” as a means to contest the structures of social institutions. Whereas the earlier works examined the political subjugation of humans, in these late works Foucault argued that, as self-determining individuals, we can resist our own subjection and have the capacity to transform our lives ourselves.

Foucault’s other key works include Naissance de la clinique (1963, trs. as The Birth of the Clinic, 1973), which examined the rise of the medical profession, Les Mots et les choses (1966, trs. as The Order of Things, 1970) on the origins of the modern human sciences, and L’Archéologie du savoir (1969, trs. as The Archaeology of Knowledge, 1972), a treatise on his archaeological method and theory.

An early victim of AIDS, Foucault died in Paris on June 25, 1984 at the age of 57.

Featured image: “Eiffel Tower” by William West. Public Domain via Unsplash.

The post Michel Foucault on the insane, the criminals, and the sexual deviants appeared first on OUPblog.

June 18, 2019

Four remarkable LGBTQ activists

Around the world, the LGBTQ community faces inequality and discrimination on different levels. Although an increasing number of countries have legalised same-sex marriage in recent years, in countries such as Nigeria and Saudi Arabia, members of the LGBT community are still fighting for their simple right to exist.

In the USA, much of LGBTQ activism began fifty years ago, starting with the Stonewall riots of 1969. In celebration of this notable anniversary, discover the lives of four pivotal activists.

1. Frank Kameny (1925-2011)

As an activist long before the Stonewall riots, Kameny was a pioneer in the gay rights movement. During World War II, he interrupted his studies in astronomy to serve in the army. At his induction, when asked if he had homosexual tendencies, he answered no. Decades later, he confessed that he resented having to lie in order to serve his country.

Kameny earned his Ph.D. in 1956 and moved to Washington, D.C., where he took a job teaching astronomy at Georgetown University. A year later, the Army Map Service offered him a job as a civilian astronomer, but after five months he was found unsuitable for government employment on the basis of information that he was homosexual. Asked to resign, Kameny refused. He interpreted the government’s action “as a declaration of war against me and my fellow gays”.

After launching a failed legal battle against the government, he recognized that it was now time for homosexuals to act collectively. In 1961, he founded the Mattachine Society of Washington, a social activism organisation for the gay and lesbian community. Kameny envisioned the struggle for gay rights as part of the larger civil rights movement, a position that emboldened him to take up the plight of homosexuals well before the Stonewall riots made gay rights a cause célèbre.

2. Harvey Milk (1930-1978)

Image credit: “Harvey Milk in 1978 at Mayor Moscone’s Desk” by Daniel Nicoletta. CC BY-SAY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: “Harvey Milk in 1978 at Mayor Moscone’s Desk” by Daniel Nicoletta. CC BY-SAY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Milk was a politician and gay rights activist. As with many gay men and lesbians of his generation, the Stonewall riots of 1969 marked Milk’s emergence as a political and social activist. A few years later, Milk moved permanently from New York to San Francisco, which had become a relatively safe place for openly gay people since the end of World War II. Milk opened a camera store on Castro Street in the centre of the gay community, and quickly became a leader in gay political activism.

In 1973, Milk declared his candidacy for the San Francisco Board of Supervisors. Although he lost that race, Milk garnered more than 17,000 votes and finished tenth in a 32-candidate field. Milk emerged from the 1973 campaign as a new force in San Francisco politics, an urban populist whose platform, while founded on gay rights, also embraced other progressive policies.

After a second race for supervisor in 1976, which he lost closely, Milk was established as the leading political spokesman for the city’s gay community. The election of his friend and ally George Moscone to mayoral office gave him access to the city’s centre of power. Moscone appointed Milk to the board of permit appeals, making Milk the first openly gay city commissioner in the United States.

3. Pat Parker (1944-1989)

Parker was a poet, performer, and activist. Growing up in the segregated South, Parker encountered racism regularly. This experience followed her during her studies at Los Angeles City College, where the head of the school’s department discouraged her journalistic aspirations, telling her there was no place for black people in the field.

However, the civil rights, women’s liberation, and Black Power movements politicized and empowered Parker. During the 1970s, Parker joined Gente, a lesbians of colour group, which provided support and solidarity in the face of racism in society at large and within the women’s movement. During this time, Parker also joined the Women’s Press Collective, a lesbian-feminist publishing collective, and she performed her poetry in community spaces, where audiences responded enthusiastically to her work.

Parker’s reputation continued to grow throughout the late 1970s and 1980s, when she travelled the world reading poems from her book, Movement in Black. Parker’s creative output throughout her life was substantial; she was an extraordinary performer of her work voicing the experiences of African American lesbians and a precursor to the spoken word movement.

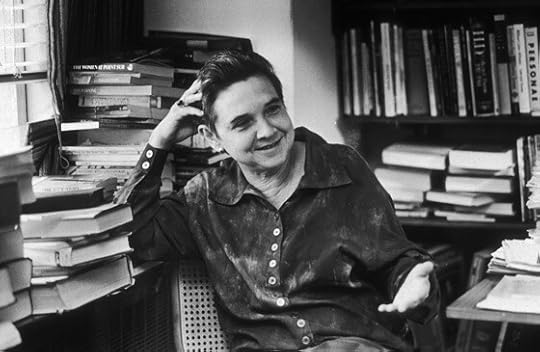

4. Adrienne Rich (1929-2012)

Image credit: Adrienne Rich by orionpozo. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

Image credit: Adrienne Rich by orionpozo. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.Rich was a poet, essayist, and activist born to a white, upper middle-class family in Baltimore. At fifteen, she learned about the Holocaust, but felt that she could not discuss it; households like hers mentioned neither the racism nor anti-Semitism so prevalent in the 1940s. Rich became committed to fighting for social justice and searching for poetry that could change the world. Her first book of poetry, A Change of World, published the year she graduated college, was chosen by W. H. Auden as the winner of the prestigious 1951 Yale Younger Poets Competition.

After many years as an established writer, Rich came out as a lesbian in 1975. She embraced her new role as a spokesperson for lesbian-feminist thought through lectures, essays, and editing. Rich and her partner, Jamaican writer Michell Cliff, co-edited one of the most important lesbian journals, Sinister Wisdom, for two years. Furthermore, Rich’s “Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence” became a key foundational feminist text. Published in 1980, her essay was one of the first texts to acknowledge lesbianism.

These four activists played an important role in promoting acceptance of the LGBTQ community, but they represent just a few of the important LGBTQ activists from history. Today, we have them to thank for paving the way towards equal rights, though the fight is far from over.

Featured image: “Gay Pride Parade” by naeimasgary. Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Four remarkable LGBTQ activists appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers