Oxford University Press's Blog, page 181

August 2, 2019

8 books to help us re-imagine populism and privilege [reading list]

The 115th American Political Science Association Annual Meeting’s conference theme is “Populism and Privilege.” It will highlight the self-identified populist movements around the globe, whose main unifying trait is their claim to champion the people against entrenched elites. This scholarship raises vital questions about whether some or all of these self-labeled populist movements represent understandable, legitimate responses to entrenched, self-serving privileges and perspectives of global and national elites or whether they instead represent efforts to preserve privileges of established groups against economic, demographic, and cultural transformations. The meeting will feature writers from around the world, whom collectively or individually speak on pressing issues surrounding this topic.

We’ve compiled a brief reading list highlighting books that focus on the conference theme.

In today’s world, working people’s experiences are strangely becoming more alike even as their disparities sharpen. Paul Apostolidis explores the logic behind this paradox by listening to what Latino day laborers say about work and society. The book shows how migrant laborers are both important in relation to the precarious conditions of contemporary work life. Read a free chapter here.

Democracy and Dictatorship in Europe

Sheri Berman provides a new understanding of the development of democracy and dictatorship in Europe by drawing on lessons from European political development that illuminate problems democracy is facing in Europe and elsewhere today.

Loren Collingwood and Benjamin Gonzalez O’Brien examine the origins of sanctuary policies, but also media framing, public opinion, policy influences, and the effect sanctuary cities have on crime and Latino incorporation.

Drawing on his experiences leading citizenship classes for Mexican migrants and working with cross-border activists, Adrián Félix examines the political lives (and deaths) of Mexican migrants. Tracing transnationalism across the different stages of the migrant political life cycle, this book reveals the ways in which Mexican immigrants practice citizenship in the United States as well as Mexico. Read a free chapter here.

Matt Guardino connects news content, elite rhetoric, and public opinion to the historical dynamics of the American media system and media policy regime and provides a study that delves deeply into the political-economic structure and institutional dynamics of the news media in this book. Read a free chapter here.

Alex Hertel-Fernandez provides a history of the rise of conservative lobbying groups, including the American Legislative Exchange Council, the State Policy Network, and Americans for Prosperity, documenting both their victories and their missteps over time.

Populism and Liberal Democracy

Takis Pappas’ book offers a comprehensive theory about populism during both its emergence and consolidation phases in three geographical regions: Europe, Latin America and the United States. If rising populism is a threat to liberal democratic politics it is only by answering the questions it posits that populism may be resisted successfully.

Read a free chapter here.

While defending the right of states to control immigration, Sarah Song also argues that states have an obligation to open their doors to refugees and migrants seeking to be reunited with family. This book considers the implications of a new positive theory for immigration law and policy. Read a free chapter here.

See which authors are hosting or attending events on this fully searchable online conference program.

Featured image credit: “Capitol Building Full View” by “noclip”. Public domain via WikimediaCommons.

The post 8 books to help us re-imagine populism and privilege [reading list] appeared first on OUPblog.

August 1, 2019

The life and work of Herman Melville

August 1st marks the 200th anniversary of Herman Melville’s birth. We have put together a timeline of Melville’s life to celebrate the event.

Feature Image credit: “Arrowhead farmhouse Herman Melville” by United States Library of Congress. Public domain via Wikimedia.

The post The life and work of Herman Melville appeared first on OUPblog.

July 31, 2019

Monthly gleanings for July 2019

As always, many thanks to those who left comments and to those who sent me emails and asked questions.

Notes on animals

Beaver

Rather long ago, I wrote four posts on the etymology and use of the word brown (see the posts for September 24, October 1, October 15, and October 22, 2014). The origin of the animal name beaver was mentioned in them too. Here I’ll say what I know about the subject. Beaver has immediately recognizable cognates in many languages and, apparently, goes back to Indo-European. The Germanic languages have similar forms: Dutch bever, German Biber, Icelandic bjórr, etc. The ancient Germanic etymon must have sounded as bebruz. The relevant words in Latin, Slavic, and Baltic are fully compatible with the Germanic ones. The Greek name of this animal is known to most of us from the myth of the “Gemini” Castor and Pollux. Some other animal name may have had the same root in Classical Greek, but the beaver was called differently (hence Castor).

The form bebruz, with its b occurring twice, is a telltale sign of what linguists call reduplication. Reduplication is ubiquitous. Consider the name of the disease beriberi; cucurri, the perfect of Latin cúrrere “to run,” and Engl. so-so and tut, tut, among dozens of others, to say nothing of phrases like it is very, very good. The main witness in the etymology of beaver is Sanskrit babhrús “brown, great ichneumon (a kind of mongoose),” and the traditional explanation has it that the beaver got its name from the color of its skin (“brown-brown”). But though repeated in the best dictionaries, this etymology need not be taken for God’s truth, because the color name may go back to the animal’s name! Some hypotheses on the origin of brown will be found in my posts mentioned above. None of them is definitive.

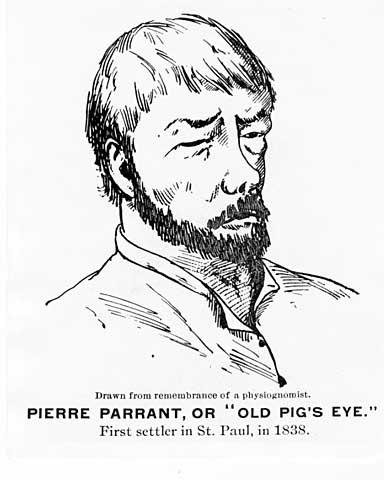

Pierre Parant. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Pierre Parant. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.The once very active American etymologist Francis A. Wood connected the animal’s name with Sanskrit bhárvati “to gnaw, chew” (related is Latin fōrma “mold, shape,” from which we have form). I don’t think anyone has discussed, let alone accepted, this conjecture. When mentioned, it is left without comment.

Pig’s eye

Our correspondent is interested not in the phrase itself but in its historical connections with St. Paul, Minnesota, for the town (the capital of the state) was for some time called Pig’s Eye. This was the nickname of Pierre Parrant, the first non-indigenous inhabitant of what later became St. Paul. Reportedly, he was blind in one eye. The phrase goes back to Middle English piggisnye (nye stands for an eye, that is, a neye, an example of misdivision (also called metanalysis), as in nanny from mine Annie, and the like). The word first occurs in Miller’s Tale (Chaucer; see the OED). At that time, it was a term of endearment. Pigs have small eyes, and possibly the association was between them and tiny but precious jewels. There is also a flower called pig’s eye. Parrant used “Pig’s Eye” as the name of his bar. Perhaps he suggested that his establishment was precious, but by the nineteenth century, the phrase pig’s eye had acquired a negative meaning and developed into a vulgar word.

Pig’s eye also became a synonym of pig’s ear as an expression of disbelief. In rhyming slang, pig’s ear meant “beer.” Again, we cannot decide whether Parrant was aware of Cockney slang. In any case, he sold liquor, and pig’s eye could very well become the name of his brand, regardless of British usage. I have read somewhere (but I cannot find my note) that at one time pig’s eye meant “anus.” No source I have consulted records it, but all the best dictionaries of slang include the phrase in a pig’s eye, synonymous with in a pig’s ear (an emphatic expression of disbelief). The sense “anus” would go a long way toward the amazing deterioration of meaning: from “my precious one” to a swear word. I suspect that Parrant knew just that sense and that his customers enjoyed the rudeness or perhaps the ambiguity of it. Be that as it may, there is still a park in St. Paul called “Pig’s Eye,” and a brand of beer also bears this name.

Pig’s eye, a true picture of beauty. Pig by Tim McReynolds from Pixabay. Pig’s face flowers public domain via pxhere.

Pig’s eye, a true picture of beauty. Pig by Tim McReynolds from Pixabay. Pig’s face flowers public domain via pxhere.Idioms

Pig and whistle

I was delighted to see the positive comments on my posts devoted to American idioms and will definitely write more about them. My prospective dictionary of idioms is expected to be published in 2020, and I hope it will sell like hotcakes. At the moment I have two things to say.

Here is the now famous tavern sign. Its popularity is recent. Photo © Jaggery (cc-by-sa/2.0).

Here is the now famous tavern sign. Its popularity is recent. Photo © Jaggery (cc-by-sa/2.0).Above, I made a few inconclusive statements about pig’s eye. By way of compensation, I mined my database for pig and whistle. This is the name of a tavern sign. (Did Parrant know it? Probably not.) The literature on such signs is a pleasure to read. The occasional phrase gone to pigs and whistles seems to have meant “ruined with intemperance,” but, if so, why did it? The inspiration must have come from the pub. Ebenezer Brewer, the main nineteenth-century authority on the origin of idioms, connected pig “a small bowl” (compare piggin “a small wooden pail”) with whistle, being a variant of “wassail,” and his explanation has often been repeated.

He was wrong by definition, for who would have put together two garbled words to produce the phrase in question? The entire phrase should be accounted for: etymologizing it word by word looks like a forlorn hope. Even the great scholar Max Müller succumbed to this temptation and traced pig to Danish piga “girl” (why?!) and whistle to the same wassail (wassail was an old salutation—wæs hāl! “be whole/ healthy!”). A reasonable hypothesis sounds so: “The phrase originated in order to explain the way in which the wood of some soft-grained tree, instead of being devoted to the formation of some permanently useful valuable article of furniture, was used up by boys and youth in the whittling of pegs and whistles. That is to say, gone to pigs and whistles means ‘reduced to some mean and trifling service’.” The alternation of short i and short e in dialects is common, so that peg could easily be confused with pig and become the source of the joke. (Signs are supposed to be memorable, not logical: compare Dickens’s “Magpie and Stump”).

In a brown study

In the posts on brown, I discussed this idiom, which means “in deep meditation.” At one time, I came to the conclusion that the phrase in a brown study had not crossed the Atlantic Ocean. I was wrong. Moreover, we should assume that it was widely known even among the lower classes. Of all people, Huck Finn says (close to the end of Chapter 41): “She judged she better put in her time being grateful we was alive and well and she had us still, stead of fretting over what was past and done. So she kissed me, and patted me on the head, and dropped into a kind of brown study.”

Slav and slave

Jon Cowan adduced two examples of an ethnic name being used for coining the word for “slave.” Both are too marginal to create a pattern, but of course, the existence of such an equation could be expected somewhere in the world. However, in the history of the Eurasian Middle Ages, similar cases are either non-existent or vanishingly rare.

Numerals

Thank you for calling my attention to the sources on the origin of numerals. I knew them both. In connection with the exchange in the comments, I can only add that of all the old Indo-European words the numerals are among the most hopeless from an etymological point of view. None of them goes back directly to Greek, even though they have cognates in Greek. Their obscurity is astounding because such primitive words could be expected to have rather obvious origins. But none of them is transparent, and the reconstructed roots sound like eeny, meeny, yield no meen’ing and leave us in the dark.

Feature image credit: D. Gordon E. Robertson, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Monthly gleanings for July 2019 appeared first on OUPblog.

Why Anna Burns’ Milkman is such a phenomenon

Few contemporary novels will have had a year like Milkman by Anna Burns. It was published, without a great deal of fanfare or advance publicity, in May 2018. But then it began to attract attention by dint of being longlisted, and then shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize. Some were surprised when it won. I wasn’t. In the course of a long commute to work, I had listened to the remarkable audiobook of Milkman twice. Gripped by that experience, I had begun to read the novel with focus. What intrigued me most was the question of how Burns had managed to write a book which can be read both within and outside the Irish tradition. I was also drawn to the question of how and why this novel seems so compelling for our time, and of how it seems so attuned to the zeitgeist of this #MeToo moment.

Quality of voice is all important to the experience of listening to an audiobook. The reading of Milkman by Bríd Brennan perfectly catches the cadence and rhythm of Burns’ strange and compelling depiction of the Troubles in Northern Ireland. The story is told from the perspective of “Middle Sister,” an unnamed central character. Milkman almost seems to have been written to be read aloud. Certainly the experience of listening to the work—my first ever experience of listening to a serious work of literature before reading any words on the page—has persuaded me that audio is a medium that deserves to be taken seriously. It is also an ideal way to tackle a work that might seem challenging, or forbidding.

These are charges which have been made against Milkman. Perhaps I too would have faltered had I begun to read the book in the traditional way. Reading and listening are fundamentally different kinds of cognitive experience, and I cannot recover the experience of being a first reader of Milkman now. I was hooked into the world of the novel right there in those car journeys. I even began to invent reasons for driving further, just so I could hear a bit more.

Milkman might be classified as a feminist Troubles narrative. Or a novel of voice. Or a dystopian fiction. Or a psychological thriller. In some sense it is all of these things. Middle Sister, the seventh of eleven children, is aged eighteen. Though she is living in the heart of a family home, she is a loner who makes herself conspicuous to community gossips by walking alone, and reading as she walks. Her isolation deepens once she begins to be stalked by “Milkman,” a 41 year old paramilitary who pushes himself in to the edges of her life. She is deeply confused by his attentions and does not know how to respond. (“Thing was, he hadn’t physically touched me.”) When her mother’s friend suggests that this encroachment might be something that the “women of the issues” could address, Middle Sister responds with derision:

These women, constituting the nascent feminist group in our area – and exactly because of constituting it – were firmly placed in the category of those way, way beyond-the-pale.

These biting ironies—so typical of the way Middle Sister sees the world—suggest that the novel is a critique of feminism, and its failings. It is also a tour-de-force exploration of an evolving feminist consciousness.

Literary prizes are big business for publishers, and booksellers. Anything listed for the Booker has a sales boost, and winners always sell well. Milkman has been a particular success, with sales in the UK jumping 880% in the week after the Booker win was announced (from 963 copies to 9446 copies). This is the highest sales jump for any recent Booker winner, besting even Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall, winner in 2009. Just over a year after publication, sales exceed 540,000 copies. The work has been a particular international success, with the deal for simplified Chinese rights believed to be the biggest single deal ever done for an author not previously published in China. This is testament to the fact that Burn’s work—inspired by the experience of growing up in Belfast in the late 1960s and 1970s—has transcended the conditions of its own making.

In addition to the Booker, Milkman has been awarded the George Orwell Prize for Political Fiction, a British prize that recognizes writing that comes closest to achieving Orwell’s ambition to “make political writing into an art.” Within the US, Milkman has been awarded the National Book Critics Circle Prize, and the audiobook has just received a Cameo award. A surprise best seller, Milkman is a rare commodity: a work of literary fiction that is both a commercial and critical success. May there be many more like it.

Featured Image: Photograph taken by Clare Hutton.

The post Why Anna Burns’ Milkman is such a phenomenon appeared first on OUPblog.

July 30, 2019

George R. Terry Book Award winners – past and present

The George R. Terry Book Award is awarded to the book that has made the most outstanding contribution to the global advancement of management knowledge. The prize is presented at the Academy of Management’s annual conference, and we would like to take this opportunity to congratulate our authors on this prestigious achievement. To celebrate, we will be revisiting the work of our winners and finalist in the past and present.

Judgment and Strategy by Robin Holt

2019: Finalist

This book argues strategy is the process by which an organization understands and declares itself. To bring this about exponents of strategic inquiry attempt to gather knowledge about the conditions in which any organization is being organized: emerging markets, restless geo-political environments, networks of technological ordering, populations and skill sets, and the like. The upshot of such inquiry is a succession of images by which an organization attains distinction as a unity, or ‘self’.

Ringtone by Yves Doz and Keeley Wilson

2018: Winner

In less than three decades, Nokia emerged from Finland to lead the mobile phone revolution. It grew to have one of the most recognizable and valuable brands in the world and then fell into decline, leading to the sale of its mobile phone business to Microsoft. This book explores and analyzes that journey and distills observations and learning points for anyone keen to understand what drove Nokia’s amazing success and sudden downfall.

Trust in a Complex World by Charles Heckscher

2016: Winner

This book explores current conflicts and confusions of relations and identities, using both general theory and specific cases. It argues that we are at a catalyzing moment in a long transition from a community in which the prime rule was tolerance, to one with a commitment to understanding; from one where it was considered wrong to argue about cultural differences, to one where such arguments are essential.

Hyper-Organization by Patricia Bromley and John W. Meyer

2016: Finalist

Provides a social constructivist and institutional explanation for expansion of organizations and an overview of main trends in organization theory. Much expansion is hard to justify in terms of technical production or political power, it lies in areas such as protecting the environment, promoting marginalized groups, or behaving with transparency.

Making a Market for Acts of God by Patricia Jarzabkowski, Rebecca Bednarek, and Paul Spee

2016: Finalist

This book brings to life the reinsurance market through vivid real-life tales that draw from an ethnographic, “fly-on-the-wall” study of the global reinsurance industry over three annual cycles.

This book takes readers into the desperate hours of pricing Japanese risks during March 2011, while the devastating aftermath of the Tohoku earthquake is unfolding. To show how the market works, the book offers authentic tales gathered from observations of reinsurers in Bermuda, Lloyd’s of London, Continental Europe and SE Asia as they evaluate, price and compete for different risks as part of their everyday practice.

A Process Theory of Organization by Tor Hernes

2015: Winner

This book presents a novel and comprehensive process theory of organization applicable to ‘a world on the move’, where connectedness prevails over size, flow prevails over stability, and temporality prevails over spatiality. The framework developed in the book draws upon process thinking in a number of areas, including process philosophy, pragmatism, phenomenology, and science and technology studies.

The Institutional Logics Perspective by Patricia H. Thornton, William Ocasio, and Michael Lounsbury

2013: Winner

How do institutions influence and shape cognition and action in individuals and organizations, and how are they in turn shaped by them? This book analyzes seminal research, illustrating how and why influential works on institutional theory motivated a distinct new approach to scholarship on institutional logics. The book shows how the institutional logics perspective transforms institutional theory. It presents novel theory, further elaborates the institutional logics perspective, and forges new linkages to key literatures on practice, identity, and social and cognitive psychology.

Neighbour Networks by Ronald S. Burt

2011: Winner

There is a moral to this book, a bit of Confucian wisdom often ignored in social network analysis: “Worry not that no one knows you, seek to be worth knowing.” This advice is contrary to the usual social network emphasis on securing relations with well-connected people. Neighbor Networks examines the cases of analysts, bankers, and managers, and finds that rewards, in fact, do go to people with well-connected colleagues. Look around your organization. The individuals doing well tend to be affiliated with well-connected colleagues.

Managed by the Markets by Gerald F. Davis

2010: Winner

Managed by the Markets explains how finance replaced manufacturing at the center of the American economy, and how its influence has seeped into daily life. From corporations operated to create shareholder value, to banks that became portals to financial markets, to governments seeking to regulate or profit from footloose capital, to households with savings, pensions, and mortgages that rise and fall with the market, life in post-industrial America is tied to finance to an unprecedented degree. Managed by the Markets provides a guide to how we got here and unpacks the consequences of linking the well-being of society too closely to financial markets.

Managed by the Markets explains how finance replaced manufacturing at the center of the American economy, and how its influence has seeped into daily life. From corporations operated to create shareholder value, to banks that became portals to financial markets, to governments seeking to regulate or profit from footloose capital, to households with savings, pensions, and mortgages that rise and fall with the market, life in post-industrial America is tied to finance to an unprecedented degree. Managed by the Markets provides a guide to how we got here and unpacks the consequences of linking the well-being of society too closely to financial markets.

Featured image credit: Books by Christopher. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post George R. Terry Book Award winners – past and present appeared first on OUPblog.

July 29, 2019

How microwaves changed the course of the Battle of the Atlantic

Sir Robert Watson Watt is credited as the inventor of radar. In Britain radar was known as RDF (radio direction finding). The way that radar works is that pulses of microwave radiation of controlled frequency and polarisation are emitted from a transmitter. Some of these microwaves reach an object (an aircraft or submarine for example) directly or after reflecting off the Earth or sea surface. For radar to work, the object must be metallic or have a partially conducting surface that absorbs and re-radiates the radio waves.

The time for pulses to travel directly from transmitter to receiver and indirectly after pulses from the transmitter are re-radiated from, for example, a hostile aircraft (the ‘echo’) are measured. In practice the distance between transmitter and receiver is small and can be neglected so that the location of the aircraft can be determined as half the distance from transmitter to aircraft and back again. Results are displayed on an oscilloscope that identify the echo, the re-radiated signal. Radar played a critical role in the Second World War, especially in the Battle of Britain in 1940, and the value of the contribution made by the air tracking radar system developed by Watt in the 1930s is immeasurable.

The system consisted of high-frequency direction-finding radio detectors (HF-DF). In 1938 the Royal Air Force erected a series of tall pylons An Allied tanker torpedoed in the Atlantic Ocean by a German Submarine, 1942. Image from Wikimedia Commons.

Some, but not all, ships possessed HF-DF detectors, and HF-DF detectors could not detect submarines. While U-boat radio emissions could be detected 20 miles away from a convoy, a plane dispatched in that direction did not have a system for detecting small objects such as a conning tower on a submarine. The Allies needed a miniature radar system that could detect such small objects. The breakthrough was made by John Randall and Henry Boot in the spring of 1940 in a wooden building at Birmingham University. They invented the cavity magnetron, which generated microwave pulses with a wavelength of 10 cm, was the size of a saucer and from late spring 1943 could be fitted in RAF aircraft. The device did not crack or melt even though it emitted high energy microwaves.

In September 1940 at the height of the Battle of Britain the Tizard Mission arrived in the United States from England, bringing a prototype cavity magnetron. James Baxter wrote in Scientists against Time (1946) that the cavity magnetron was, “the most valuable cargo brought to these shores.” This device was far ahead of any comparable miniature radar device under development in the United States. In March 1943 squadrons of fully equipped aircraft began to join the Allied forces in the Battle of the Atlantic. Now the Allies could search out and destroy German U-Boats from the air with unparalled accuracy. US industry had manufactured one million cavity magnetrons before the end of the Second World War.

After the war, the United States increased its research and development into the cavity magnetron and microwaves in general. Among the leaders in the field was the physicist Percy Spencer. There is a story that while working at the defence contractor Raytheon, Spencer walked past a bank of equipment that was generating microwaves, and the chocolate bar in his pocket softened, giving him the idea that microwaves could be used to heat food. That led very quickly to the development in the late 1940s of the first type of microwave oven, the early models of which contained cavity magnetrons.

Featured Image: Convoy WS-12 en route to Cape Town, 1941 ‘ used with permission from Wikimedia Commons.

The post How microwaves changed the course of the Battle of the Atlantic appeared first on OUPblog.

July 26, 2019

Why British communities are stronger than ever

Although it’s fashionable to bemoan the collapse of traditional communities in Britain and the consequent loss of what social scientists have come to call social capital, we should be wary of accepting this bold story at face value. For a start, the UK has not suddenly become an individualist nation—individualism has deep historic roots in the Protestant Reformation, roots that were further strengthened by the early adoption of market economics across large swathes of British society.

Even bodies that grew up to resist the logic of market atomization, such as trade unions and cooperative societies, often preached collectivism as the only way in which their members could hope to enjoy the individual freedom and personal autonomy that others took for granted.

The cosy, close-knit vision of community we project on to the recent past is a myth. Yes, poverty and close proximity obliged neighbours to look out for one another, but privacy remained jealously guarded, relations with neighbours were often fraught, and reliance on strangers, as opposed to family, was widely seen as a last resort.

In recent years, my research has focused on re-analyzing the surviving field notes and interview transcripts from a range of historic social science projects conducted between the late 1940s and the late 2000s. Interrogating original testimony from the forties and early fifties demonstrates that the motto of many living in tight-knit, working-class communities like Bermondsey and Bethnal Green—so often held up as the epitome of “traditional” Cockney London—was always “we keep ourselves to ourselves, and then we can’t get into trouble,” as one Bermondsey labourer put it. The famous sociologist Michael Young heard the phrase so often during his research for Family and Kinship in East London (1957) that he simply wrote “Again!” in his notes after a Bethnal Green housewife told him that “[you’re] better off if you keep yourself to yourself”. For many, the demands of forced community were a burden to be managed, rather than something to be celebrated.

In the years after the Second World War, people came increasingly to question the dictates of custom and tradition. Millions leapt at the opportunity to escape the close-quartered, face-to-face communities of Victorian Britain, where everyone knew each other’s business.

But this was not a rejection of community per se. Rather, it represented an attempt to find new ways of living better suited to the modern world. In the process, community became increasingly personal and voluntary, based on genuine affection rather than proximity or need. Contrary to the claims of the doomsayers, we have actually never been better connected or better able to sustain the relationships that matter to us than we are today.

Contrary to the claims of the doomsayers, we have actually never been better connected or better able to sustain the relationships that matter to us than we are today.

The desire to reconcile personal independence with social connectedness is in many ways the defining feature of English popular culture in the modern age. But this reconciliation is not easy to achieve. Many struggle to find a happy balance in their lives between self and society. In turn, policy-makers have also struggled successfully to reconcile the potentially competing claims of individualism and community, especially since the 1980s. But the fact that so many profess to lament the current bias towards materialism and narrow self-interest, and mobilize powerful narratives about the death of community to underscore their dissatisfaction, reminds us that the ascendency of economic liberalism may not be as securely based as we often imagine.

What we need is concerted, joined-up policy designed to facilitate social connection at the grassroots level. Much is already happening, notably in the help offered to local groups to run community resources like pubs and shops and in the heightened awareness of loneliness, but this will count for little if we don’t stop the decline of other vital community facilities such as libraries, parks, sports fields and civic space itself (all too often ceded to private developers in recent decades). Popular individualism and the powerful urge for personal independence will always limit the scope for grand, top-down plans to build community, but if policy makers, public bodies and voluntary groups work with the grain of popular culture, and focus instead on systematically providing the diverse contexts within which social connection can flourish on the ground, much can still be achieved.

People have long sought to reconcile autonomy with social connection—self and society. It is high time that we valued and nurtured the new groups and forms of sociability that have developed in recent decades, rather than bemoaning the passing of a largely mythic version of community.

Featured image credit: Image owned by Jon Lawrence. Used with permission.

The post Why British communities are stronger than ever appeared first on OUPblog.

July 25, 2019

How Germany’s financial collapse led to Nazism

The summer of 1931 saw Germany’s financial collapse, one of the biggest economic catastrophes of modern history. The German crisis contributed to the rise of the Nazi Party. The timeline below shows historic events that led up to Adolph Hitler’s taking control of Germany.

Featured image credit: The SA in Berlin in 1932. . Bundesarchiv, B 145 Bild-P049500 / CC-BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post How Germany’s financial collapse led to Nazism appeared first on OUPblog.

July 24, 2019

Mangling etymology: an exercise in “words and things”

We read that Helgi, one of the greatest heroes of Old Norse poetry, sneaked, disguised as a bondmaid, into the palace of his father’s murderer and applied himself to a grindstone, but so bright or piercing were his eyes (a telltale sign of noble birth, according to the views of the medieval Scandinavians) that even a man called Blind (!) became suspicious. He said that such eyes became a warrior. To make matters worse, the “bondmaid” ground a bit too hard, because the stand under the mill was splitting. The Icelandic word for the stand, or support, of the grindstone is möndull or möndultré (tré means “tree”).

This is our Scandinavian hero with shining eyes. Helgi und Sigrun by Johannes Gehrts. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

This is our Scandinavian hero with shining eyes. Helgi und Sigrun by Johannes Gehrts. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Möndull is the oldest recorded name of the object called “mangle” in Present-day English. However, in English, we also find the word mandrel with several senses, two of which are “a shaft in a lathe” and “a miner’s pick.” Both mangle and mandrel were recorded only in the eighteenth century. Their etymology is sometimes said to be unknown, but French has mandrin “a punch, mandrel,” and Classical Greek has mándra “an enclosed space, sheepfold,” also used to designate the bed in which the stone of a ring is set, “much like Engl. mandrel,” as Walter W. Skeat explains. Finally, there is Oscan mamphur “part of a lathe.” (Oscan is an extinct language of southern Italy.) It seems that the Germanic ancestor of Old Scandinavian möndull and Engl. mandrel reached Germanic speakers from the south, perhaps from Greece via Italy.

All this information can be found in dictionaries, but it will be fair to say, that the most detailed history of the noun mangle comes from the German scholar Rudolf Meringer, a brilliant representative of the movement known by its German name Wörter und Sachen (“Words and Things”). He also edited a journal called Wörter und Sachen, which is a pleasure to read, because it printed numerous illustrations, and what’s the good of the book without pictures?

An old mangle. Photo © David M Jones (cc-by-sa/2.0) via Geograph.

An old mangle. Photo © David M Jones (cc-by-sa/2.0) via Geograph.In retrospect, there is nothing revolutionary in the ideas of that school. Obviously, in order to discover the etymology of the word, we have to know the construction of the thing this word denotes. Yet even today one runs into attempts to explain the name of some fish as “streaked” (this is a random example), and it becomes clear that the linguist has never seen the fish in question (because it has no streaks). In 1906, Meringer investigated all the words and all the objects connected with the mangle.

Anyone can see that mangle and mandrel (we’ll disregard the suffixes) differ in one important respect: the first word has g, while the other has d in the root. Those who like novels about the Middle Ages (alas, my students have never read a single work by Walter Scott) will remember that military expeditions occupy a prominent place in them. Castles are constantly besieged, and one of the machines used to destroy them is the mangonel, a kind of catapult. The origin of the machine’s name poses no problems. The English word, first recorded in the thirteenth century, came from Old French. The etymon is Latin, but its ultimate source is Greek mágganon (gg has the value of ng). There is no nd in the root of that word.

In the Middle Ages, no walls were attacked without mangonels. From the Dictionary of French Architecture from 11th to 16th Century by Eugène Viollet-le-Duc. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

In the Middle Ages, no walls were attacked without mangonels. From the Dictionary of French Architecture from 11th to 16th Century by Eugène Viollet-le-Duc. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.To turn to more peaceful pastimes: the main function of the mangle is to roll and press laundered clothing. It may be useful to quote an explanation added to the definition of mangle in The Century Dictionary: “In the older form an oblong rectangular wooden chest resting upon two cylinders and loaded with stones was moved backward and forward by means of a wheel and pinion, the rollers being thus made to pass over and press the articles spread on a polished table underneath.” The construction of the mangle and the mangonel is in some respects similar.

It was believed that the pressing machine had borrowed its name from the war engine. But Meringer had a good point: the mangle, a household device, must have been the older contraption of the two, so that the mangonel was probably named after the mangle, rather than the other way around. The Greek word also meant “magical object,” and magic, as we know, can be used for both good and bad purposes. Latin mango did not necessarily denote a swindler, an unreliable dealer; as Meringer pointed out, initially it referred to any trader. In all English compounds, from whoremonger and warmonger to costermonger and fishmonger, monger goes back to the Latin word, of most probably Greek origin.

A costermonger, a hawker of fruit and vegetables. Victoria Embankment, via Leonard Bentley on Flickr. CC BY-SA 2.0.

A costermonger, a hawker of fruit and vegetables. Victoria Embankment, via Leonard Bentley on Flickr. CC BY-SA 2.0.When Old Germanic mandel and the borrowed mangel met, it appeared that they denoted similar objects, and an expected fight between two near-homonyms, which happened to be near-synonyms, ensued. Scandinavian stayed with –nd-, while West Germanic (English, Dutch, and German) switched to –ng-.The plot thickens when we approach the English verb to mangle “to mutilate, crush, injure” and German mangeln “to lack.” Engl. mangle looks like a natural cognate of the word for the war machine invented for demolishing walls. This verb appeared in texts in the fourteenth century, early enough to be related to the noun, which, as noted above, though undoubtedly old, was recorded about four hundred years later. Mangonel goes back to the 1200s. The chronology is confusing and does not seem to be of much relevance in this case.

Whatever the origin of the English verb, it must have been influenced by the meaning of the noun. However the main point is this: according to what looks like scholarly consensus, mangle (verb) and mangle (noun) are unrelated. The English verb is believed to go back to Anglo-Norman mangulare, whose origin is unknown (that is, we have no idea what the reconstructed root ment- and its variant met- designated). Both maim and mayhem are its probable derivatives. Old French mahaigner meant “to cripple.”

Related forms have been found in numerous languages, including Old Slavic, Lithuanian, and Sanskrit. They mean “to disturb, irritate; embarrass; whip butter, press, etc.” Neither met nor ment resembles a sound-symbolic or an onomatopoeic formation, so that there have been attempts to connect men– with min– as in mini– (compare diminish). German mangeln “to lack” does not quite align itself with that lot, unless we bring mini into play. Its oldest forms meant the same as today: “to lack, do without.” Is this the reason no one wants to connect it with the name of the pressing machine? Elmar Seebold in his edition of Kluge’s etymological dictionary says without any discussion that mangeln is a borrowing of Latin mancare “to mutilate.” But don’t we need “to lack”?

It would be nice to incorporate the verbs (mangle and mangeln) into the presser ~ catapult’s family and declare them related, but no one is ready to do so, and for the moment we too will stay slightly embarrassed and at the unready.

Feature image credit: The Siege of Eger in 1552 by Béla Vizkelety. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Mangling etymology: an exercise in “words and things” appeared first on OUPblog.

July 22, 2019

How medical marijuana hurts Mexican drug cartels

Public support for marijuana legalization has grown substantially. The consumption of recreational marijuana has been legalized in Uruguay, Canada, and several US states. In addition, many European countries, most US states, and Thailand have passed laws that allow the consumption of cannabis for medical reasons. Given the growth in public support, it is important to arrive at a better understanding of the welfare consequences of marijuana legalization.

In the United States, California was the first state to pass a medical marijuana law in 1996. These laws allow patients with a prescription from a doctor to consume marijuana. The laws also legalize the whole supply chain, allowing small-to-medium scale farmers to grow cannabis, so that it can be sold in marijuana dispensaries. More than two decades later, 33 states and the District of Columbia have followed suit. Such laws allow researchers to study the systemic effect of marijuana on crime. It appears that medical marijuana laws can reduce violent crime, dramatically, at least in US counties that border Mexico.

Earlier drug decriminalization policies in the Netherlands, and several US states decriminalized the consumption, but not the supply chain. Medical marijuana laws are the first policy to decriminalize the consumption, distribution, and small- and medium scale production of the drug. By legalizing the supply chain, these laws take away the business of marijuana from organized crime.

Prior to the increase in medical marijuana legalization laws, marijuana had been a lucrative crop for Mexican drug cartels, since the drug is easily cultivated in the Mexican climate. The cartels could grow it themselves and ship it to the US with small declines in quality due to transport and storage. At the same time, the cartels are known to contribute to large-scale systemic drug violence in the United States, especially in the region close to the Mexican border. The cartels would use violence to protect their territories and shipments on both the Mexican and the US side of the border.

However, with the introduction of legal marijuana the playing field changed. Marijuana produced in the US tends to be fresher. Given the legality, there is more variety of types, and there is no risk of prosecution for those who are qualified for the use and production. Suddenly, the Mexican cartels had difficulties competing and in making profits in the marijuana market because the demand for illegal marijuana started to decrease. We find evidence that the reduction in the profitability in the marijuana market results in a drop in drug-related violent crime.

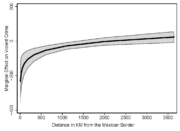

The effect of medical marijuana laws on violent crime by distance from the Mexican border. Image used with permission from the authors

The effect of medical marijuana laws on violent crime by distance from the Mexican border. Image used with permission from the authorsWhen a state at the Mexican border legalizes marijuana for medical consumption, the violent crime rate decreases by 13 percent on average. Whenever inland states introduce such laws, violent crime in the nearest border state decreases, as smuggling routes leading to the state become less profitable. The strongest reduction of crime is in counties closest to the Mexican border, with 200 less violent crimes per year as is illustrated in the figure. The figure shows that the negative effect on crime diminishes as a county is located farther away from the Mexican border. The crimes most strongly affected are robberies and homicides. Murders related to the drug trade decrease by a staggering 41 percent.

Policy makers resort to policing and enforcement strategies in the effort to reduce drug violence. These strategies include militarized deployment, killing and apprehension of cartel leaders. However, several studies show that these interventions are counterproductive; they escalate rather than curb violence. Instead, policy makers could focus on reducing the profitability of drug trafficking. An unexpected benefit of medical marijuana laws is that they reduce violent crime related to drug trafficking.

Featured image credit: Cannabis Plants by Rex Medlen. Public Domain via Pixabay .

The post How medical marijuana hurts Mexican drug cartels appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers