Oxford University Press's Blog, page 184

July 5, 2019

How technology is changing reproduction and the law

Millions of Americans rely on the likes of birth control, IVF, and genetic testing to make plans as intimate and far-reaching as any they ever make. This is no less than the medicine of miracles. It fills empty cradles, frees families from terrible disease, and empowers them to fashion their lives on their own terms. But every year, thousands of accidents happen: Pharmacists mix up pills. Lab techs misread tests. Obstetricians tell women their healthy fetuses would be stillborn. These mistakes can’t be chalked up to reasonable slips of hand or lapses in judgment as often as human failures and flawed quality controls.

But political and economic forces conspire against meaningful regulation. And however egregious the offense, no statute or doctrine says that these injuries matter, legally speaking. The American legal system treats reproductive negligence less like mischief than misfortune. Some courts insist that thwarted plans are too easy to contrive and too hard to verify. Others wonder why victims didn’t just turn to abortion or adoption instead. Most are unwilling to risk characterizing any child’s birth as a legal injury. So judges throw up their hands when professional misconduct leaves patients with no baby, when they undertook reliable efforts to have one; any baby, when they set out to avoid pregnancy and parenthood; or a baby with different genetic traits than the health, sex, race, or resemblance they’d carefully selected.

This isn’t the first time that technological advances have outpaced the slow churn of the legislative process and existing tools of the common law. It was exactly one century ago, the legal scholar Roscoe Pound, then dean of Harvard Law School, published the new edition of his treatise, On the Law of Torts. What made the textbook remarkable was its inclusion of a prescient chapter that set forth an emerging right for the “Interference with Privacy.” That right is well-established today. But American law wasn’t much concerned with the exposure of secrets until advances in picture-taking made natural bedfellows with professional muckraking.

News outlets had been an expensive and largely exclusive enterprise, with the handful of major papers focused on economics, politics, and art. Photography, meanwhile, was an unwieldy and time-consuming undertaking, in which willing participants had their portraits taken in a formal studio. Cheaper and quicker printing techniques ushered in a competitive tabloid industry that used salacious reporting to sell papers. This yellow journalism got a boost from the invention of handheld cameras that let amateur Kodakers pry into the personal spaces of others and memorialize their guarded moments for the whole world to see.

Failed abortions, switched donors, and lost embryos may be first-world problems, but these aren’t innocent lapses or harmless errors.

Yet these privacy incursions found no redress in the existing law of contract, defamation, copyright, or otherwise. And judges initially rejected appeals to recover for intangible interference’s with privacy. In 1902, New York’s high court protested that even the “[m]ention of such a right is not to be found in Blackstone, Kent or any other of the great commentators upon the law.” Slowly but surely, judges began exercising their common-law powers to recognize new claims of privacy. And by 1941, most states recognized that now-familiar right of the one that wrestler Hulk Hogan asserted, for example, to win the $140 million judgment that bankrupted Gawker in 2016 after the media giant posted his sex tapes online.

Not a single new such tort has been adopted in nearly a century since. The time has come.

A similar story can be told about reproductive negligence today. Just as click-camera incursions placed privacy interests in sharp relief, lost embryos, defective Plan B, and switched donors bring to fuller expression the meaning and significance of the interests that people have when it comes to family planning. Each represents a distinctive interference with reproductive liberty. The first kind of case leaves affected families painfully incomplete. A second forces victims to care for a child they were in no position to. The third changes the experience of raising a child of a different type. Practical differences among these injuries can’t be captured by any monolithic cause of action. Three separate rights should protect against procreation that’s wrongfully deprived, imposed, and confounded. Tort law is no less equipped than it was in Pound’s era to accommodate these real and substantial harms that don’t involve any unwanted touching, broken agreement, or damaged belongings.

We’re used to blaming randomness or cosmic injustice when we don’t get the child we want, or when we get the one we don’t. And yet cutting-edge interventions promise to deliver us from the vagaries of natural conception and the genetic lottery. Sometimes things don’t work out —but that’s no reason to turn a blind eye when bad behavior seriously impairs people’s autonomy, well-being, and equality with those whose family planning comes more easily. Failed abortions, switched donors, and lost embryos may be first-world problems, but these aren’t innocent lapses or harmless errors. They’re wrongs in need of rights.

Featured image credit: Baby by Janko Ferlič. CC0 via Unsplash.

The post How technology is changing reproduction and the law appeared first on OUPblog.

July 4, 2019

The gender riots that rocked Cambridge University in the 1920s

On 20 October 1921, a sombre procession took over King’s Parade, a usually bustling thoroughfare in Cambridge. A hearse made halting progress, bearing the weighty effigy of the Last Male Undergraduate, and accompanied in shuffling steps by ‘Mere Males’: bowed and wretched figures wearing long grey beards. Their sprightlier colleagues made speeches about the risks of female governance at the side of the road, hassled young women on bicycles and eventually raised the cry: “We Don’t Want Women!”

All this was because of a vote that was taking place that day in Cambridge University’s Senate House, to decide whether the women’s colleges, Newnham and Girton, would be allowed membership of the university. It was a vote between two compromise options: one offering degrees but not membership of the senate, the other only a ‘titular degree’ (ie. the certificate but none of the rights that went with a degree). Though suffrage had been extended to some women in Britain in 1918, and the women’s colleges in Cambridge were over fifty years old, women were not entitled to participate. Members had to vote in person, so by the time an official appeared on the steps of the building to announce the women’s defeat (i.e. the passing of the second option), it was just after 8.30 p.m. Cheers erupted. One Reverend Howard Percy Hart, perhaps overexcited by his day trip into Cambridge to cast his vote, exhorted the mob to “go and tell Girton and Newnham!” Off they went.

The principal of Newnham College (Girton was a long way out of town), Blanche Athena Clough, was a veteran of the women’s movement and was expecting trouble. The entrances to her college were closed and barred against the 1,400 or so men now charging towards them; supposedly, police and proctors (the university’s own disciplinary force) were on standby.

Between Blanche and the men stood the Clough Memorial Gates, a bronze tribute to her aunt, Newnham’s first principal. Halted there, the students turned their attention to another set of gates leading to the yard outside Old Hall (where some of the Newnhamites’ bedrooms were). Smashing down the brick gatepost, they gained entrance to the yard and commandeered an old handcart, with which they returned to batter in the lower panels of the Memorial Gates, causing hundreds of pounds worth of damage.

On the other side of the college, a subsection of the rioters managed to force open the iron gates of Clough Hall, break windows and smash in a door leading to Peile Hall. Only by placing themselves in the doorway were Proctors able to prevent the young men from gaining entrance. They satisfied themselves by searching for undefended parts of the college, shouting and singing, for another hour. For ninety minutes that evening, the women of Newnham were under siege.

At first the undergraduate community seemed appalled by the incident. Keen to display gallantry, each college held a meeting over the following weekend in which they passed resolutions condemning the assault. The colleges formed a committee to convey to Blanche Athena Clough, in person, the feeling that the outburst of “a small number of undergraduates” was strongly resented. Students elicited (and quickly received) donations to cover the cost of repairs. This, the young men seemed to feel, should be enough to close the matter. The controversy that erupted in the national press therefore stung them badly.

The shocking attack, by opponents to a motion that had anyway been defeated, caught press attention almost immediately. The Daily Chronicle reported “a very malicious attempt to accentuate the defeat of the women by destroying their property” as early as the 22nd. Within days The Times was intoning of “grave injury”; The Spectator of “bad manners and stupidity.” The Cambridge undergraduates’ own professors berated them for their un-sportsmanlike conduct. “What sense,” cried one, “what chivalry, was there in kicking the party that was down?” How could they possibly be trusted to run the empire one day, another worried, if they couldn’t even be trusted to behave as gentlemen?

The undergraduate press (which did not include women, of course) responded swiftly, transforming the debate from a question of the wrong done to women to one of the wrong done to Cambridge men. “[W]e feel it incumbent upon ourselves to drop our bantering for a while,” a Granta editorial announced gravely, a week after the attack on Newnham, “and utter a protest against the hysterically grotesque attack made upon Cambridge Undergraduates.” (They were talking about themselves.)

Sensational reporting had failed to understand that the whole thing was a prank, university magazines insisted; that the police were at fault for not stopping them; that, in fact, there was “a considerable number of foreign Undergraduates” involved.

To many, the outcry was simply further evidence that, despite appearances, it was in fact Cambridge masculinity that was under threat (rather than, say, the education of women or the principle of equality between the sexes). Whilst Dorothy Marshall, a young student at Girton, had spent 20 October in town “feeling small & forlorn & somehow in a hostile country” and Newnhamite M.E. Roberts remembered her college “temporarily resembl[ing] a beleaguered fortress,” it was clear to their male contemporaries that it was the women’s presence that was the threatening one. Young Cambridge men may have attempted to invade a women’s college but it was simply intended as a pre-emptive strike. Only the previous year, their elders had warned that though “for the moment [women] may be content with having stormed the walls of the university … in time… they will be heard knocking loudly at the gates of the colleges.”

The injustice of the whole thing was so severe that the concurrent coverage for the women rankled. The student press noted the “propaganda” gains for Newnham, and began to question the veracity of Blanche Athena Clough’s estimate of the damage. Worse was to come, when a handful of students who had been involved in the raid were indentified and disciplined. In the words of an outraged student, “thanks to the childish feminine spite born of disappointment, several relatively innocent undergraduates have been sent down.”

One nice thing about the day of the Senate House vote, The Old Cambridge reflected afterwards, was that “men, and men only, thronged the pavements of King’s Parade…men’s voices filled the air…Men dominated the scene: woman might never have been born into the world.” This halcyon moment would never be regained in Cambridge, though it took until 1948 for women to obtain full membership. The hysterical reaction to their campaign in 1921 ensured that the Newnham and Girton staff trod carefully for the next two decades, keen not to jeopardize their hard-won, if unequal, place at the university. After the events of October 1921, it was a position they understood to be far less secure than they had hoped.

Feature image credit:”Newnham College, Cambridge .” Photo by Azeira, via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The gender riots that rocked Cambridge University in the 1920s appeared first on OUPblog.

July 3, 2019

Etymology gleanings for June 2019

Like every journalist (and a blogger is a journalist of sorts), I have an archive. Sometimes I look through the discarded clippings and handwritten notes and find them too good to throw away. Below, I’ll reproduce a few rescued tidbits.

The bitter honey of Spelling Bee

Problems abound. Several years ago, I read in the major newspaper of the town in which I live: “Once again, stellar young spellers of the Twin Cities [Minneapolis and St. Paul, Minnesota] find themselves in a predicament…. No sponsor has emerged to organize or foot the bill for a regional spelling bee…. A metropolitan area with six professional sports teams—and a billion-dollar stadium in downtown Minneapolis—should be able to scrape together a few grand once a year for a well-established, much-loved, and much publicized competition of the academic field.” We are spellbound. Hear, hear!

The organizers of the most recent tournament are also in despair, but for another reason: eight participants spelled all the terrible words correctly. Spelling coaches have not been paid for nothing. At the moment, a search is on for even harder technical terms, the terms that no one outside professional circles needs. I have some advice for the organizers. Concentrate on personal and place names. At least they are “fun.” To be sure, Worchester and Leister are too easy, but think of Beauchamp (= Beecham), Cholmondeley (= Chumley), Marjoribanks (= Marchbanks), Strachan (= Strawn), Menzies (= Ming–is), and my great favorite Leveson-Gower (= Lewson Gore). Dictate askew to them, and they will shrug their shoulders, but, alas, it is Ayscough. Brougham and broom will not trouble anyone, but, in any case, what a fertile field for wasting one’s brains and time!

Image CC0 Public Domain via pxhere.

Image CC0 Public Domain via pxhere. This is not Becky Thatcher. Image by Levan Ramishvili via Flickr, Public Domain.

This is not Becky Thatcher. Image by Levan Ramishvili via Flickr, Public Domain.Meanwhile, I came across an old article on Margaret Thatcher (NY Times) by an experienced journalist and the London weekend editor. She wrote about how Mrs. Thatcher and her husband vetted the list of those who should be invited for a gala at Downing Street. Mr. Thatcher disapproved of some candidates, but a few of those he rejected “got a thumb’s up” from his wife. This is the most hilarious apostrophe I have seen in years (and believe me: in my students’ papers, I have seen them all, including Proffesor [sic] Higging’s). It would be nice to organize an impromptu spelling competition among editors, proofreaders, English teachers, and media people, with Mr. Thumb as Chair. The motto could be: “Thumb’s Up.”

An aside. My colleague, a professor at a major American University, asked a large group of students: “Do you know who Becky Thatcher is?” After a pause, someone volunteered a question: “Do you mean Margaret Thatcher?”

PS. As far as I can judge, half a century ago, 1960s and the like were spelled with an apostrophe (1960’s).

Who are we?

Bow Street Magistrates Court by Matt Brown. CC 2.0 via Flickr.

Bow Street Magistrates Court by Matt Brown. CC 2.0 via Flickr.I had the impression that the prevalent use of female instead of woman is an American invention. But this is what I found in the book Guesses at Truth by Augustus J. and Julius C. Hare; its first series was published not later than 1827. The authors discussed the use and abuse of the words wight, person, and their synonyms. Among other things they wrote: “As a woman now deems it an insult to be called anything but a female, as a strumpet is become [sic] an unfortunate female, and as every day we may read of sundry females being taken to Bow Street [the famous Magistrates’ Court in London], in like manner everybody has been metamorphosed into an individual, by the Circe who rules the fashionable slang of the day.… A beggar this morning said to me, that he was an unfortunate individual….” (p. 91 of the London reprint; note the use of the comma.) It is curious to watch how words come, go, and come again.

The modern-day Circe looks very nice, and so do the pigs. Image via the Internet Archive Book Images on Flickr.

The modern-day Circe looks very nice, and so do the pigs. Image via the Internet Archive Book Images on Flickr.Always grumbling

New words irritate us. But there is no need to worry: they too shall pass. From Notes and Queries 4/VII, 1871: 252-53: “Who brought into fashion the word well-nigh, which within the last year or so has come to be commonly substituted for almost? One has always been familiar with well-nigh in old [sic] English, and in our northern counties it has never gone out of colloquial use; but in ordinary English speech, and in writing, it had become nearly obsolete. All persons [!] now-a-days read newspapers and novels, and many read nothing at all, so that a word once started by a popular novel-writer or journalist becomes within a few months adopted by the public in a truly remarkable manner. One cannot now take up a newspaper, magazine, or popular tale, without coming upon well-nigh in such a position as almost would have held a year or two ago.”

To be or to not be again

I also have a petty pet peeve. My fight against gratuitous splitting is pathetic, rather than heroic, but I cannot understand why you may not want to even look at the photo…. and he has a duty not to publicly make or defend offensive remarks…. are clearer, better, or more eloquent than you may not even want to look and a duty not to make or defend offensive remarks publicly. Specialists, I am sure, know how long splitting has existed in regional American English, but, since I have mentioned Becky Thatcher, I may now turn to Huckleberry Finn.

Huck’s recollections: “She said it [i.e. smoking] a mean practice, and I must try to not do it any more” (Chapter 1) and “He used to always whale me when he was sober….” (Chapter 3). My question is: With regard to grammar, should Huck Finn be our role model? Universal splitting seems to have inundated newspapers about fifty years ago. Nowadays, journalists “know” that infinitives should be split, but most do it ineptly. Reread the phrase a duty not to publicly make… offensive remarks. The writer probably wanted to say a duty to not publicly make offensive remarks, but had a vague recollection that this is not a good thing to do and shoved to farther away, to the worst place possible, instead of producing a sentence in less “fashionable” English. As they say in such cases: “Where is the outrage?”

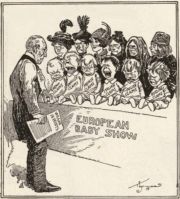

Has anyone seen these words? Wilson’s Fourteen Points: European Baby Show. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Wilson’s Fourteen Points: European Baby Show. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

From The Nation 109 (No. 2827), 1919, p. 327: “There are times when our principles forsake us. Such a time has come. Armistice, Fourteen Points, freedom of the seas, self-determination, everything to the contrary notwithstanding, we are for Yap! It is recorded that Yaps, Yappers, Yappites, Yappiki—whatever they call themselves—are ‘highly intelligent for savages’….” Who exactly was meant, and were those words indeed current after World War I? Were Yappers Yuppies?

Dated slang

How the Other Half Talks. Lack of work among the laboring classes has many curious euphemistic synonyms, among which are the following: Legging it; on one’s uppers; on the loose pulley; got a steady job of loafing; wheeling a light into Flat Rock Tunnel; shoveling smoke out of a gas-house; pressing bricks and turning corners; holding on the slack; living on one’s intellect; living on the interest of one’s debts. (American Notes and Queries, vol. 7, 1891, p. 166.)

Speak of the devil

In 1884-1885, Notes and Queries published a series of letters under the title Topographia Infernalia. Some time later, I may return to it, but today I’ll only quote a sentiment with which I fully agree. “An eminent book collector, noted for his good nature, declared that a man who published a book without an index ought to be put in the thistles beyond hell, where the devil could not get him. Yet the thistle appears to be in some sense one of the devil’s plants.”

Featured image credit: Perspective View of Western Portal, Looking SE. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Etymology gleanings for June 2019 appeared first on OUPblog.

How feminism becomes a tool of neo-imperialism

During this year’s State of the Union address, President Donald Trump claimed that one in three women crossing the United States/Mexico border is sexually assaulted. Though the specific statistic he cited is questionable, it should come as no surprise that women crossing international borders face severe gender-based violence. What is surprising is that the president, who has minimized and mocked many of the at least thirteen women who have accused him of sexual harassment and assault, suddenly seemed to think gender-based violence was a problem.

His rhetoric reveals more than simple hypocrisy. It manifests a set of epistemic habits associated with what I call “missionary feminism.” Missionary feminists filter information about the world in ways that turn analyses of the situation of “other” women into opportunities to confirm Western superiority. A danger of missionary feminism is that it makes imperialist attitudes and policies seem like they are required by a commitment to gender justice.

The president’s portrayal of sexual assault is strategically silent about what makes sexual assault happen at the border. A New York Times investigation revealed that much of the sexual violence that women face crossing the border happens once they are in the United States at the hands of U.S Customs and Border Patrol staff. Even when women are sexually assaulted by smugglers, it is often within the supposed safety of US territory. Women migrants who are victims of sexual assault within the United States even face deportation.

Not to mention that what makes women vulnerable in the first place is a set of US government policies that militarize the border and contribute to the conditions that make women need to cross the border to begin with. For example, the conditions provoking asylum seekers to leave Honduras were caused by Honduran President Juan Orlando Hernández’s US-backed government.

This strategic silence is an example of one epistemic habit constitutive of missionary feminism: the idealization of global geopolitics and history. We idealize something when, in the process of abstracting about it, we attribute positive attributes to it that it does not actually have (or have to the degree we think it does). The president’s comments idealize the global order by ignoring the role that global factors, like US border and economic policy, play in making women vulnerable to gender-based violence.

Those of us living in the West and North have been trained to fill in the explanatory blank left by the absence of a global structural analysis in a particular way: by attributing gender-based violence to other cultures. Indeed, the president has publicly suggested in other speeches that people from certain non-white cultural groupings are especially likely to commit rape. This resort to the cultural is also a part of missionary feminism. Failing to look at global structures and Western complicity in violence and injustice around the world allows Western culture to seem to have the moral high ground. Those who only see gender-based violence when they imagine it is committed by others can easily preserve the idea that Western culture has produced emancipation for women.

But the idea that the West, or Western culture, has ended sexist oppression is false and self-serving. Sexual assault and sexual violence remain widespread in the United States, as the current #MeToo movement points out. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that one in five US women will be sexually assaulted. Women in the United States and Western Europe continue to do much more housework and care work than men. The ability to work outside the home is often presented as empowerment, but is it really a straightforward feminist success that US women spend more than three times as much time on housework as men?

The idea that Western intervention or Western culture are good at ending the sexist oppression of women who live in the global South is also specious. The global economic order, driven by the interests of Western countries, increases the amount of unpaid labor women have to do and increases their economic vulnerability. For example, the International Monetary Fund and World Bank promote the privatization of social services, and women must often pick up the slack left by end of public funding for these services by increasing the amount of time they spend caring for children, the sick, and people with disabilities.

Admittedly, Trump is no feminist. But missionary feminist attitudes often help win hearts and minds, even self-described feminist hearts and minds, to imperialist causes. The Bush administration’s similar, but perhaps less racially motivated, fixation on sex trafficking de-emphasized the other forms of labor trafficking to which women were subject and characterized the causes of prostitution in ways that ignored the economic conditions that make women collude with sex traffickers. It was supported by high-profile feminist organizations. A media campaign to convince US women that feminism means celebrating Trump’s attention to trafficking is already underway.

The ease with which feminism gets coopted to serve the purposes of Northern and Western domination may seem like cause for pessimism. It shouldn’t be. We need cross-border feminist activism now more than ever. The causes of much contemporary gender injustice are transnational, ranging from war, to the disproportionate recruitment of women into low-status factory work by multinational corporations, to US policies that prevent women in the global South from seeking abortion and contraception.

What we need is not a retreat from global feminism but rather a feminist reckoning about values. Feminists need to turn from a missionary feminism that highlights contrasts between North/West and South to preserve Northern/Western superiority and toward asking the real feminist question: what reduces sexist oppression? Oppression is a set of social relations in which one group is systematically subordinated to another. Remembering that feminism is about women’s oppression can help us avoid the mistake of assuming that any mention of women, or policy targeted toward them, is necessarily feminist. Since reducing oppression means making change in the world, feminists need to be empirically informed about the causes of the problems they are trying to solve. This includes seeking knowledge about how global structures and Northern policies cause harm to women. A first step toward anti-imperialist global feminisms is for people in the North to be able to recognize missionary feminism for what it is.

Featured image credit: Photo by Siora Photography. Fair use via Unsplash.

The post How feminism becomes a tool of neo-imperialism appeared first on OUPblog.

July 2, 2019

Connecting performance art and environmentalism

For many of us, the reality of global warming and environmental crisis induces an overwhelming sense of hopelessness because there seems to be a lack of real solutions for ecological catastrophes. The looming sense of crisis is the reason why people came out in droves to the Derwent River on an overcast day in June 2014 to participate in Washing the River, artist Yin Xiuzhen’s performance event in Hobart, Tasmania.

Audience members took brushes and mops to engage in a ceremonial act, taking part in the symbolic cleansing of a monumental stack of 162 frozen blocks of dark brown ice made from the water of the Derwent River. The artist has tapped into the universal desire to make some sort of contribution to undoing the damage to nature. Since the 1970s, performance artists have developed a vital and creative role in environmental activism, and like Yin, they have done the work of bringing entire communities together to enact ecological change; or, to actually do the work of restoration such as reforesting lands and replenishing at-risk eco-systems.

Yin’s performance provided a new updated perspective toward performing environmentalism. Washing the River was restaged four different times and it was first performed at the Funan River in Chengdu, China in 1995. The event was presented again at the Upper Georges River in Sydney, Australia in 2010 and more recently, in 2017, at the Pesanggrahan River in Jakarta, Indonesia. An artist who lives and works in China, Yin originally staged Washing the River for an agricultural community in the rural south of her country. She explains that, when the performance ended, people wanted to bring the blocks of ice home to keep their food cold. As shown by their urge to re-use the ice from the river, the audience members living agrarian lifestyles differ greatly from the class of consumers who generate the most waste and carbon emissions.

For a long time, China’s contribution to the survival of the planet and the whole of natural life was through the country’s slow industrial growth, sustaining a population of 1.3 billion people in the 1990s. But the society known for bicycles (not cars) as its primary mode of transportation was transformed dramatically in the thirty years after Deng Xiaoping’s economic reforms. By 2018, China was emitting more carbon from fossil fuels than Europe and the United States combined. Still, the image of a progressive, successful Chinese capitalism aligns with the modern nationalist ideal for a country once denigrated as backward and primitive.

The Yin exhibition in faraway places in all parts of the world emphasizes the cultures and lifestyles that are also endangered, along with their rivers and diverse ecological systems. The banks of the Derwent once served as the home for the aboriginal Tasmanian community before the British occupied the territory in the 19th century. The activist practice of Yin’s performance connects with the aboriginal community’s time-honored communal rituals, paying reverence to the river, to nature, and thereby providing a reminder that humans are inseparable from nature. The 19th century industrial drive is one that divided humans according to the primitive and the modern, recognized as agricultural economies and the industrialized nations. Only now, the whole of the human species is implicated today, since it is responsible for the demise of the environment.

Performance artists like Yin (and others, including Ana Mendieta, Kalisolaite ‘Uhila, and Patty Chang) remind us of our inextricability from nature and of the fact that there are many humans who still live close to nature. The artistic and performative ritual is timeless in its connecting humans to natural processes. Against the dire consequences of ecological crisis, the performative aesthetic is a creative solution for rethinking the role of humans and for taking seriously indigenous forms of knowledge that affirm all biological life. All natural life must share the same natural resources, breathe the same air and drink the same water. Creative inspirations such as Yin’s, bringing communities back to the river, engaging with each other and with nature, engenders an uplifting hopefulness and a return to the belief in human possibilities.

Featured image credit: “New Norfolk Derwent River” by eGuide Travel [CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...)] via WikiCommons.

The post Connecting performance art and environmentalism appeared first on OUPblog.

It’s not you, it’s me: the problem of incivility

We regularly decry this or that latest episode of incivility, and can thereby find temporary satisfaction. Maybe we feel heartened to see the uncivil criticized, the critique itself a reassurance that incivilities still meet some resistance. Maybe we find relief in collective condemnation of the uncivil, solidarity in shared disapproval. Or maybe we just experience atavistic delight – if the uncivil offend our sense of good and right, it can feel good and right to see them publicly pilloried for it. But these satisfactions steer our thinking about civility away from a better target. The incivilities that ought to concern us first and most should be our own.

The early Confucians were passionate advocates for civility. Contemporary readers may receive this fact with dismay. It is likely to stimulate associations with finger-wagging scolds condemning others’ uncivil crimes and rude misbehavior. But Confucian advocacy is framed firmly in the first person: I should be civil. I should cultivate in myself the habits of emotion, mind, and conduct to make respectful and considerate engagement with others my steady norm. This is an approach to civility sorely missing from our popular discourse. Perhaps one reason for this is that my own failures of civility are so much less satisfying to consider than yours.

The incivilities of others largely lie outside my control, but my own are problems over which I can exercise some power. To take myself in hand will entail sacrificing the fast, frenetic pleasure of saying just what I think in favor of slower tact and care. It will entail cultivating better habits and reflexes where others displease me. It will entail trying to hold fast to pro-social values that recognize our dependencies on each other even amidst our many differences. Most of all, it requires an unsettling, introspective honesty about what moves and motivates me.

When I consider what prompts my incivilities, I find a murky mess. Absent are the crisp explanations I give the incivilities of others. Where I can quickly count uncivil others naught but purely awful, I read my own motivations as complex and vexed. This is why Confucius upbraids one of his students for a tendency to morally judge others, wryly remarking that it must be nice to have time for such pursuits. For if you but turn that critical gaze upon yourself, you’ll find more than enough to consume a calendar of days and years. The explanations won’t be quick and the work of being better will be long and hard. At least I have found it so.

My impulses to incivility are many and diverse. Sometimes I act as what Confucius calls a xiaoren, or “petty person”. I focus on my own interests, caring not what comes of you as I aim at what I want. Sometimes I grow angry and want a chance to lash and thrash, ignoring or denying any damage to the one who feels my blows. Sometimes I want a bit of fun and, let’s face it, rudeness is more fun than restraint can ever be. Sometimes I want that fellow feeling when we together can despise some others, using incivility to build ourselves a bit of “them” so that the “we” opposing them are better bonded. Sometimes I want power in a world that would deny me. If I can take you down a peg with disrespect, your descent can work an elevation for myself. Sometimes I want to shut another up, to get relief from hearing you by making you not want to speak. Sometimes I am just tired and incivility brings a needed rest from taxing self-control.

There is much more than even this that works as spur when I am rude, but let this little bit suffice. The purpose here is not to catalog exhaustively, but to register the trouble. And of course the trouble does not stop with all these reasons I can have, for the trouble rarely sorts so simply as I here suggest. My motivations to incivility are many and diverse, but more vexing still is how they intermix and mingle. The flow of my incivilities is most often sourced by many streams at once.

None of this of course rules out that incivility may sometimes just be good. There may well be times when the best that I can do is deal a little disrespect. The challenge here will be to know when that is so, to avoid the self-deception that would have me tell myself I’m always in the right when rude. The self doubt this all induces is surely why even sage Confucius claimed he only got himself in order at the age of 70. It takes long practice to earn instincts you can trust.

Too often we treat civility as a second- or third-person art, a mechanism to decry what you or they have done. To take civility as a first-person project is to say that “the problem of incivility” is not first you or them, but me. And in this way, perhaps, the problem can more fruitfully be ours. For even as I see the mess I make of things, the ways I can be mean or low or cruel, I will see along the way the reasons you can be the same as well. We all are sometimes tired, angry, and needful of relief. As a Buddhist injunction would have it: “We here are struggling.” Perhaps if I struggle more with myself, we can against each other struggle less.

Featured image: Photo by Amy Olberding, 2019. Used with permission.

The post It’s not you, it’s me: the problem of incivility appeared first on OUPblog.

July 1, 2019

How new technology can help advocates pursue transitional justice

People today document human rights incidents faster than it can be processed or analysed. Documentation includes both official and unofficial information, ranging from reports and inquiries to news articles, press releases, statements, and transcripts. These can all serve as a record of a human rights violation.

There is simply too much content to synthesize quickly enough for use in judicial or policy work. However, as this content is valuable for justice and accountability, we need to find ways to convert it into usable information. New technology has a crucial role to play in this process, allowing us to analyse, view, and use information. This is particularly interesting in conflict contexts.

Active armed conflicts and mass human rights violations persist globally. Many countries are still reeling from conflicts that have ceased, or past periods of mass human rights violations. The violations are often so numerous and serious that the regular justice system is unable to respond adequately. As a result, countries often establish a variety of specialised judicial and non-judicial measures to support their transition towards sustainable peace – this is known as transitional justice. The most common approaches include the creation of specialised criminal justice mechanisms, truth seeking initiatives, reparations programs and institutional reform. Transitional justice initiatives such as these aim to recognise the dignity of individuals, provide redress for violations, prevent recurrence and contribute towards national reconciliation.

One useful example comes from the civil war in Sri Lanka, which ended in 2009. Following years of conflict, and much disagreement about how the end of the war unfolded, in September 2015, at the United Nations Human Rights Council in Geneva, the Sri Lankan government agreed to establish a range of transitional justice mechanisms. These included an office on missing persons, a reparations commission, a truth commission, and a judicial mechanism.

The proposed transitional justice mechanisms in Sri Lanka, like similar ones in other contexts, need reliable data. Existing documentation on human rights violations is a vital data source. At the outset, documentation enables transitional justice mechanisms to design>Conflict Mapping and Archive Project have manually searched for and read close to 6,000 documents online and in archives. Researchers have scoured these documents for relevant information on possible human rights violations. This process involved hours of work by a number of committed students as well as around a dozen pro bono lawyers over the course of 18 months.

Automated systems that capture newly created or historical electronic content may be incredibly powerful in transitional justice work. These systems have existed for decades, but it is unclear if and how they have been used in transitional justice. Existing sophisticated content-gathering systems could largely replace manual searching and filtering, like that undertaken by the mapping project team, requiring significantly less effort and oversight. Automated systems have sometimes been used for larger projects that predominantly monitor contemporaneous news sources, but have been less frequently used for historic conflicts or for projects that incorporate a wider variety of sources.

Once researchers have gathered the appropriate documents and filtered them to include only those that are relevant, they still need analyze and extract pertinent information. Those working on the mapping project in Sri Lanka have done this manually, with researchers coding and entering the relevant information into a database to form over 4,000 incidents. This is because the benefits of technological development have inconsistently filtered into the human rights and, more specifically, transitional justice fields, so the majority of the work has been completed by hand.

Content analysis technology could improve the process of human interpretation, helping to automatically extract and code this information. One example is text annotators, such as the Stanford Core NLP tool, which could make the work of researchers much more efficient. However, we are still not at the stage where technologies such as these are being used routinely in transitional justice contexts, because they are difficult to employ and the margin of error is still too great to justify its use.

Finally, the information that has been selected and extracted needs to be understood, both in isolation and in comparison to other information. Truth seeking mechanisms are concerned with identifying trends and patterns, as well as root causes and antecedents. To facilitate this process, truth commissions and other transitional justice mechanisms generally use various databases as a major component of their information management system. The mapping project currently relies on a simple relational database, which can be modified in-house and can generate internal customisable reports. It is user-friendly and serves the project’s purposes well, because it can be shared easily and external users can navigate the reports without a sophisticated understanding of technology.

As valuable as databases are, however, they are not at the cutting edge of what is technologically possible today. Increasingly, human rights data are presented in a visual format. More often, non-government organisations are using interactive data visualisation techniques to facilitate ease of understanding and analysis for the user. People can better understand complex information if they can visualise it, allowing data to become more persuasive and memorable. Since researchers cannot accurately anticipate what each user’s interest will be in the dataset, interactivity gives users the ability to select relevant data for visualisation.

The Conflict Mapping and Archive Project recently finished a report based on all the information it has gathered and analysed. The next phase of its work will involve creating an interactive data visualisation tool. These resources will be crucial foundations for truth, reparations, and accountability work. The mapping project’s use of modest technology to process information overloads has led to an exploration of the exciting possibilities for comprehensive, efficient transitional justice work.

Featured Image Credit: “Grey click pen on black book” by Thomas Martinsen. CC BY 2.0 via Unsplash.

The post How new technology can help advocates pursue transitional justice appeared first on OUPblog.

June 29, 2019

#MeToo and Mental Health: Gender Parity in the Field of Psychiatry

In 2015, I retired from the NHS and presented an exit seminar titled “Career Reflections of a 1970s Feminist,” using my experiences of training and working in medicine and psychiatry from 1975 to 2015 to highlight women’s issues. Afterward, I was surprised by discussions with current women psychiatry trainees, who said that not much had changed in terms of their work experiences.

This was shocking and sad. Many women who campaigned during the 1960s assumed that inequalities would melt away when the Sex Discrimination Act 1975 and the Equal Pay Act 1970 were enacted on 29th Dec 1979. Instead, throughout 2018 there has been a deluge of media coverage about gender inequalities and sexual harassment.

The Women’s Movement has a long history dating back to the fifteenth century or before and gathering momentum in the 19th century. I have in my ancestry two pioneering intellectual women, Margaret Fuller (1810-1850) and Frances Willard (1839-1898), who were part of the Women’s Movement in America. In those days, their priorities were education and suffrage. They would have been disappointed to think that 200 years later, women were still suffering inequalities. In 1893, New Zealand became the first country in which women had the right to vote in parliamentary elections. The two World Wars later opened spaces for women to excel outside their domestic spheres.

Women (and men) have made great strides in this arena, but something has stalled since enactment of our discrimination and equality laws. The immediate response is to gather data and draw up policies and protocol. But these have not worked in the past, so why expect the same process to produce different results next time? Sam Smethers, CEO of the Fawcett Society, talks of “push back.” Historians of feminism talk about waves (which implies troughs too). Others talk of “undercurrents” or “stealthy factors,” or instruct in survival strategies such as “leaning in.”

We do not know why such inertia exists in our social structures. Perhaps ethological (observation of animal behaviour) research in our organisations is the place to start. How do people, men and women, behave in our institutions and why is the resistance to change so strong?

Consider these three scenarios:

1. Cauliflower cheese portions:

This is familiar to many women. You go to the canteen at work with male colleagues and the kindly serving staff dish out your cauliflower cheese. As a woman, mine was often smaller than that of the male doctors I dined with. Portion control was not equal. We paid the same. We were all happy—the men get a good dollop of lunch, I got plenty for my needs and the kindly staff had done their jobs well. But it was not equal. Is it a problem? Is it so much part of our indoctrinations that it is usually invisible? Is this just a clear and amusing example of many, more insidious inequalities that perpetuate gender differences in our social settings? Verdict: More research needed.

2. Surfing

It is becoming apparent that women doctors work harder than many men doctors and get paid less. How did that happen when the UK has a national contract? There is focus on clinical awards, who gets extras, career effects of working less than full-time, gender differences in academic medicine, and so on, but ethological research could give insights here too. Consider this stereotyped scenario: male consultant, any specialty, his secretary may make him tea or coffee, hang up his coat, prepare clinic, tribunal, and lecture materials, have letters ready for signing, manage his diary, etc. His team will usually be fully staffed and his operating theatres have their quotas of assistants. What of this happens for his woman colleague? Are more staffing gaps found in teams with women consultants? Who does the extras such as on call rota planning, extra teaching, and pastoral care? Close analysis of the ways institutions support men and women employees differently may show that while men get help to surf the waves, women get ballast and smaller surfboards. Again, more research needed.

3. Witch hunting

Something happens in the treatment of women employees as they get older. Just at the stage when they are likely to have fewer domestic commitments and more time available for work, their wisdom and skills seem less valued. At this stage, there seems to be a culling of older women and a stacking up of older men at the hierarchy pinnacles. Some people’s testimonies seem difficult to believe initially, until one considers witch hunting. Why did witch hunting—a gendered phenomenon that defied logic–evolve in some societies in the past, and by which medusa tentacles is such group-think or bias evident now? Why do our social systems need this sort of group behaviour, who initiates it, who perpetuates it, and who benefits from it? More research needed.

Psychiatry is not the only space in which women are silenced or burdened, but as a discipline it’s one lens through which we can analyse a larger phenomenon. Now more than ever, it’s essential to discuss, in real time, women’s experiences as health professionals and as patients in mental health services. Too often women have been silenced and the gender gap in scientific publications is one example of this. As I edited the essays for this book, I was constantly overwhelmed by their quality, integrity, and content, and so inspired by my wonderful women colleagues.

Featured image credit: “Medical hospital hallway” by Foundry. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post #MeToo and Mental Health: Gender Parity in the Field of Psychiatry appeared first on OUPblog.

June 28, 2019

LGBT Pride month timeline: The 50th anniversary of the Stonewall uprising

2019 marks the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall Riots, a series of revolts by gay, lesbian, and transgender people against police harassment in Greenwich Village, New York City, in 1969. The riots are considered a pivotal moment in the LGBTQ rights movement. During the 1950s and 1960s, when homosexuality was still illegal in all U.S states except Illinois in 1969, police forces across the country would routinely raid gay bars. To commemorate this historic event and the birthplace of the pride revolution, we explore the important events in LGBTQ history, from antiquity to the modern day, the important thinkers and some key milestones for the LGBTQ rights movement.

The list is not meant to be exhaustive but is an overview of the key dates in the development of LGBTQ history.

Featured Image: Photo by Stavrialena Gontzou on Unsplash

The post LGBT Pride month timeline: The 50th anniversary of the Stonewall uprising appeared first on OUPblog.

How drawing pictures can help us understand wine

It’s notably very difficult for most people to talk about wine. Part of this may because wine is a fairly complex product. But the language itself may also be a barrier to understanding. John Cleese once satirized the pretentious oenophile in Monty Python: “Real emetic fans will also go for a ‘Hobart Muddy’, and a prize winning ‘Cuiver Reserve Chateau Bottled Nuit San Wogga Wogga,’ which has a bouquet like an aborigine’s armpit.” But actual terms commonly used to describe wine are often almost equally ridiculous.

Watch here as Master Sommelier candidate Ian Cauble describes a wine blind and identifies its grape variety, vintage and region almost perfectly. The analytic manner in which he does this process is based on the deductive tasting method.

Unfortunately Ian did not pass the exam the year the film was made. Many other students never even reached this point in their tasting career. Most fail.

But despite that, interest in becoming a taste master has never been higher. Since 2011, registration for the Court of Master Sommeliers’ introductory course has jumped 71 percent, and registration for the certified exam is up 95 percent. There are still under 250 Master Sommeliers in the world, and candidates can expect up to a decade or more of intense training in advance of the grueling three-part test that, on average, takes three tries to pass.

Thousands paid to vicariously experience the Master Sommelier exam through the movie SOMM, whose success has spurred two sequels (SOMM 2 and SOMM 3) as well as launching an annual conference dedicated to the SOMM that started in 2015.

Consumers today are not content with merely knowing about a product, they desire mastery. Expertise can seen as a social cue for when it comes to high status products. Certification can also lead to professional opportunities and higher salaries. A list of wine certifications are available here.

Taste and smell, which combine to form flavor, are two of the senses that humans least understand (or trust). Constellation Brands research finds about a third of consumers state that they are confused about wine.

Learning to taste and appreciate the target product is key to become an expert in all taste domains. In wine education programs students are given a template for wine analysis (see grid from the Court of Master Sommeliers here ) and taught to learn the language of wine. This is supposed to make the otherwise ambiguous taste experience more concrete and reduceable to different attributes (color, aroma, taste, quality, etc.).

Beyond wine and the wine aroma wheel, other domains have developed similar systems such as cheese, coffee, chocolate, tea, whisky, and beer. Beer has its own certification system, as does cheese, whisky, tea, chocolate and there is even a water sommelier.

Part of the purpose of education is to provide experts a meaningful way to communicate to consumers about how a wine tastes. The problem is that verbal descriptors can only go so far when describing a perceptual experience like wine. The expert lexicon can distance the average consumer from the taste experience.

Media coverage on the “most irritating wine words” to consumers, which include terms like “firm skeleton,” “old bones,” and “nervy.” Some 55% of consumers said that many descriptors did not help them understand the taste of wine. Yet, instead of changing the terms, or way wine is described, publications like Wine Spectator have encouraged consumers to learn the lexicon.

But while the traditional verbal and analytic tasting notes are important for the novice taster, over time, to become expert, a different way of tasting is called for.

It may be useful to encourage consumers to harness their overall impression of the wine by thinking of it as a shape, and to have them draw it as an image. The drawing process allows consumers to pay more attention to their taste experience and notice subtle differences. This also allows consumers to think about flavor more holistically: The process of doing the drawing allows consumer to see whole experience of wine and how develops on their own palate, in turn allowing them to better connect what’s in the glass with the flavor they perceive. Using a visual sense to portray a lesser understood sensory modality is effective in learning as the image can serve as a mnemonic device for later memory. See an example below:

Drawing from one of the wine studies in the article. Used with permission by the article author.

Drawing from one of the wine studies in the article. Used with permission by the article author.Some wineries try to use shapes/imagery as part of their marketing, see Domino wines, where the winemaker uses his shapes on the label. Gilian Handelman, Director of Wine Education for Kendall Jackson, has used shape drawing to portray differences in their wines. Elaine Chukan Brown (aka Hawk Wakawaka) has visual tasting notes that have been used for wine cartoons and labels .Even some wine apps like QUINI are moving in the direction of having visual tasting notes. The majority of the wine industry, however, still relies on verbal descriptors which fail to capture the holistic taste experience.

Thinking of wine in this new manner, as a shape, may seem unusual for consumers, but it has the potential to improve how people think about and order wine. In the future, we may order wines in restaurants not by asking for “full bodied” with “red fruit,” but having guests use Etch a Sketch devices so consumers can convey their taste preference to the sommelier.

Featured image credit: “Okanagan Valley, Canada” by Kym Ellis. Free use via Unsplash.

The post How drawing pictures can help us understand wine appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers