Oxford University Press's Blog, page 180

August 8, 2019

Robot rats are the future of recycling

I just watched WALL-E for the first time in five years or so. It’s the story of a plucky little robot tasked with cleaning up the world by compacting rubbish into blocks and building structures out of the blocks to minimize the amount of land they take up. Of course, he falls in love and saves the world along the way, but for a geek like me, that’s beside the point. It’s a great movie about robots and, laws of physics aside, shows quite a deep understanding of their potential. However, in their quest for a truly dystopian scenario, I think the storytellers missed the point about how such robots could really help us.

Imagine that, twenty years from now, we have got our production of plastic rubbish mostly under control. I saw Prof Mark Miodownik of University College London give a great talk on how he and his colleagues are working to make this happen for plastics. This would involve limiting our use of everyday plastics to those that easily be recycled, using enzymes to break them down into the hydrocarbons we need to make more stuff, and having a much clearer and more efficient recycling streams. To be really effective, this would have to happen not just for plastics but for everything: paper, organic matter, electronics. Though only a tiny fraction of the waste we produce is currently dealt with constructively, change is already happening: there are industrial machines designed to split out construction waste for re-use, disassemble iPhones, and sort in recycling plants.

Just stopping making the situation worse isn’t enough though. I think what haunts many of us is the idea that we have done too much damage to the planet for it to ever recover. So, after we stop (quite literally) trashing the planet, how do we deal with all those hundreds of thousands of acres of landfill across the world? Or, for that matter, the Texas-sized garbage patch floating in the ocean, made infamous by Sir David Attenborough two years ago?

To me, the obvious answer is autonomous robots. Not some magic-bullet-solves-the-whole-problem race of giant super-intelligent humanoid robots, but a swarm of mostly-small robots with dexterity and a specific expertise, but relatively limited native intelligence otherwise. I imagine hundreds of robot rats (probably looking more like cockroaches actually), scurrying up landfill with little sensors and dextrous arms, identifying particular types of material, and delivering the sorted rubbish to larger carrier robots that will take the sorted materials back to the recycling plant when they are full. Some robots will be bigger and stronger to pick up and lug old appliances back to base. Some will have specialist sensors to identify tricky materials. And all will have some ability to communicate with each other, even if only in the most rudimentary way.

This heterogeneity – the idea that there will be a diverse community of machines with different skills and of different generations – is one of several things that the makers of WALL-E gets very right. Another is the idea that robots don’t need to squander one of our precious resources: power. Apart from the obvious idea that small machines can use solar power to keep going, there are other possibilities too. Refueling robots (you’d want these stations to be able to move to where they’re most efficiently used) could also be powered by digesting some of the biological matter in the landfill. Two decades ago, researchers at the University of the West of England developed a system that could eat and get energy from slugs: surely a vegan digester must be possible by now. If that can’t work, then we could try to develop some kind of miniature version of the Klemetsrud waste-to-energy incinerator in Norway, which now includes carbon capture.

To make sure the electricity burden is minimized in the first place, we will want to use the most efficient hardware possible. For more than 30 years, we’ve been developing models of how to do vision, hearing, and other intelligent tasks using silicon circuits that work more like our brains do. This field, known as neuromorphic engineering, not only has the advantage of speed, but – when designed well – neuromorphic circuits can operate with several orders of magnitude less power than their conventional digital counterparts.

Of course, a vision like this has many challenges: not least ensuring that robot rats aren’t hurting biological wildlife (perhaps including real rats). In an effort like this we will undoubtedly encounter unexpected problems and unintended consequences. But scientists, engineers, and philosophers from across the world have been considering these issues for decades now and, apart from anything else, we are all now exquisitely aware that the biggest danger to human life is other humans.

Why don’t we have swarms of robots in our landfill yet, when most of the technological problems seem to be solvable? Perhaps it’s because we, as citizens, have never made it a priority. But it’s clear robotic technology can develop pretty fast when given the right resources. In this case, the research is funded by the military. Of course, they’re looking to replace pack animals, security guards, and people who have to decommission bombs, not sort garbage. The engineers work according to our priorities, so if we want to see progress, we need to put our money where rubbish is.

On the plus side, the kind of smaller, less-intelligent, less safety-critical robots that we need to sort trash should be massively cheaper than the machines that we need to accompany troops. And maybe a war on rubbish is one that we could eventually win.

Featured images from Unsplash and Pixabay.

The post Robot rats are the future of recycling appeared first on OUPblog.

Why academics announce plans for research that might never happen

Why do academic writers announce their plans for further work at the end of their papers in peer reviewed journals? It happens in many disciplines, but here’s an example from an engineering article:

Additionally, in our future work, we will extend our model to incorporate more realistic physical effects . . . We will expand the detection procedure . . . We will integrate our detection procedure . . . We will validate the performance of our proposed detector with real data.

There are several possible explanations for this practice. One is that it’s a continuation of a discussion between author and colleagues—participants in a society meeting, conference, or research network. Another is that it’s a response to a reviewer’s critique of the submitted paper. To secure its publication, the author promises to remedy its defects in future work. Yet another is that it’s simply promotional—an advertisement of the scope of the research, its importance to the field.

To be clear, none of this refers to suggestions in an article to benefit research by the larger community. For example, an author might suggest new lines of investigation or potential confounds in experimental practice, here in a study of mental health problems: “Depression, too, can be heterogeneous . . . and future work would be wise to consider such variation.”

In contrast, an author’s announcement of his or her intentions can present readers with a dilemma. Should they restrict their own research to avoid duplication or, more drastically, turn to a different area of study? As Vernon Booth noted in his prize-winning booklet Writing a scientific paper, published in 1971, “An author who writes that an idea will be investigated may be warning you off [his or her] territory.”

Suppose, though, you’re committed to the territory. Should you accelerate your efforts to avoid being overtaken? Or continue at the same pace and assume that duplication is unlikely? Or should you exercise patience and wait for the follow-up publication to see what emerges? If you do wait, where should you look and for how long? Or should you simply ignore the announcement? After all, the author may never publish again. He or she may have promised too readily and not thought through what was entailed, or having done so, loses interest, or for other reasons disengages from the field, or from research more generally. And of course it’s possible that the announcement was meant only for effect, an empty version of the warning described by Booth. Parallels can be found in the software industry’s promotion of what became known as vapourware—advertised products that didn’t exist and were never likely to.

Curiously, the act of rounding off a paper with an announcement has a remarkably long history. Here’s an example from about 350 years ago: “And the next time, we hope to be more exact, especially in weighing the Emittent Animal before and after the Operation.”

And another from over 150 years ago: “We hope shortly to be able to prepare some pure cobalt and nickel by depositing galvanoplastically those metals in the form of foil from solutions of their pure salts.”

And another from about 50 years ago: “Quantitative results regarding these phenomena have been obtained and will be published in due course.”

In fact, this last example, which a colleague helpfully identified, is from one of my own publications, a note published during my thesis studies.

Nevertheless, it’s difficult to justify the inclusion of such material in papers now. In his booklet, subsequently revised and republished, Booth said that promises should be offered sparingly. The advice was probably too gentle. Whether they’re about future publications or research, it’s best to avoid statements of intent altogether. They can prove a challenge for the reader and, just occasionally, for the author too.

Featured image credit: “White Printer Paper Lot” by Pixabay. Public domain via Pexels.

The post Why academics announce plans for research that might never happen appeared first on OUPblog.

August 7, 2019

Racial biases in academic knowledge

The word of racism evokes individual expressions of racial prejudice or one’s superiority over other races. An outrageous yet archetypical example is found in the recent racist tweets made by the President Donald Trump, attacking four congresswomen of color by suggesting that they go back to the countries where they are originally from if they criticize America. Along with such individual racism, institutional racism exists not only in politics, entertainment, housing, healthcare, and incarceration, but also in education. However, what is often overlooked is another form of racism—epistemological racism or biases in academic knowledge and associated scholarly activities.

In schools and universities, racism is typically regarded as microaggressions that students and instructors of color experience daily as a result of intentional or unintentional racial insults targeted at them. Racism is also manifested as over- or under-representations of certain racial groups in institutional categories, such as departments, committees, and administrators. Yet, epistemological racism is invisible and ingrained in our academic knowledge system, reinforcing institutional and individual forms of racism.

In North America, for instance, racial biases in school knowledge becomes evident when we ask, whose culture and views are reflected in teaching history, literacy, language, and art. Similarly, in higher education, it is important to question whose perspective dominates theory, methodology, and empirical knowledge deemed legitimate. Obviously, in many disciplines, a typical answer is European-American epistemological approaches originally developed by white scholars, often male, trained within Western academic traditions. Many scholars of color are compelled to fit in this mainstream culture of white knowledge in order to survive and thrive. This includes myself—a woman scholar of language education originally from Japan and working in a North American university. This pressure to succeed makes students and scholars of color complicit with white knowledge, further perpetuating this sort of racism.

Academic socialization requires alignment of one’s scholarship with established theories and methodologies. Research requires citing key works published by well-known scholars. Epistemological racism is reproduced in this process, as these key works, or the original ideas that these key works draw on, are often produced by white scholars in the West. This ends in solidifying institutional racism because citation records often serve as a yardstick for measuring individual academic merit. Thus, scholars, who are well-cited, tend to receive greater recognition, leading to higher positions, more awards, and more professional opportunities. Scholars from non-Western backgrounds, typically identified by their names, tend to be disadvantaged as they are cited less often, unless they are distinguished. Moreover, even white European scholars, if they are from non-Anglophone backgrounds, may struggle to publish in international English-language journals because their research focused on local contexts is seen as too parochial. Thus, epistemological racism manifests itself as knowledge exclusion based on not only scholars’ racial and ethnic roots but also on the subjects of their research.

However, some scholars have begun to resist and decolonize Western-centric academic knowledge. For instance, Raewyn Connell uses an umbrella term, southern theory, to describe how postcolonial and indigenous perspectives can promote alternative academic worldviews that prioritize the experiences, identities, and values of non-Western cultures, while critiquing the hegemony of Western normative lens through which we understand culture, language, history, and society. However, this alternative approach can be problematic. For example, the field of communication studies has begun to explore ethno-centered approaches to understand unique features of communication in non-Western cultures. However, such scholarship may fail to take into consideration diversity, complexity, and conflicts within each culture. Moreover, women proponents of southern theory may still be silenced or marginalized by patriarchal academic traditions. This emphasizes the importance of understanding how power relations are forged through the complex interplay among race, gender, class, nationality, sexuality, ability, and so on.

Overlaying President Trump’s demand that the four congresswomen of color should leave the country if they don’t like America on epistemological racism, we see an invisible force imposing scholars of color to conform to the system of white Western academic knowledge—you should love white Western knowledge if you strive to achieve scholarly success. As one of the critical scholars of color contesting epistemological racism, I have begun questioning my own citation practices: Do I draw on European-American theories over others? Do I cite well-known male scholars over female scholars or color? What are consequences? Do these practices help perpetuate institutional racism and sexism, which continues to marginalize me in academe?

Featured Image Credit: ‘Library, book’ by Susan Yin. CCO public domain via Unsplash .

The post Racial biases in academic knowledge appeared first on OUPblog.

Some American phrases

This is a continuation of the subject broached cautiously on July 17, 2019. Since the comments were supportive, I’ll continue in the same vein. Perhaps it should first be mentioned that sometimes the line separating language study from the study of history, customs, and rituals is thin. For example, there was (perhaps still is) the British English phrase to hang out the broom. It meant “to invite guests in the wife’s absence,” while in other situations the same phrase referred to a working girl’s desire to get married. (See the post of February 10, 2016 on it.) There is nothing here for the linguist to do: all the words are clear, and the meaning is known. One has to discover why the custom of hanging out the broom indicated such unexpected things. This is what so-called antiquaries try to do. In fact, most idioms, unless they contain incomprehensible words like brunt and lurch, are of this type.

Consider the phrase blue plate lunch(eon). Wikipedia has an article about it, but I can add something to what it says. Blue plate special first referrred to a low-priced meal that usually changed daily. The name “may well have come from the over-popular ‘willow pattern’ of the chinaware.” (All my quotes have been borrowed from Notes and Queries and American Notes and Queries.) It still remains somewhat unclear “when designers introduced the theoretically excellent, but actually disturbing, practice of dividing a large luncheon plate into compartments.”

A correspondent, who sent a letter to ANQ in 1945, wrote that the source of this expression may perhaps be found in the description of Forefathers’ Day, a New England tradition first observed in December, 1798. It later became customary to eat from huge blue dinner plates specially made by Enoch Wood & Sons of Staffordshire. One can see that here, as in the case of hanging out the broom, we deal with a custom. Yet both phrases are indeed idioms, because the knowledge of their components won’t help an outsider to understand the whole.

Many years ago, we rented a cabin in northern Minnesota. The owner was a handyman who owned an establishment called “Let George do it.” His name was indeed George, and I found the sign ingenious and clever. Only much later did I learn that the phrase let George do it means “let somebody else do this work.” I’ll now reproduce part of the letter from the New York Public Library, addressed to Notes and Queries in 1923. The expression “has in the last ten or dozen years become current in America. Especially during the [First World] War was it in common use. We are interested to learn if there is any foundation to the statement that this phrase is of English origin. We know that the French have employed for several centuries a very similar expression, ‘Laissez faire à George, il est home d’âge’ [‘Let George do it; he is a grownup man’], which they trace back to Louis XII. Has such an expression been used in England, and if so, is there any explanation of its origin known to you or your readers?”

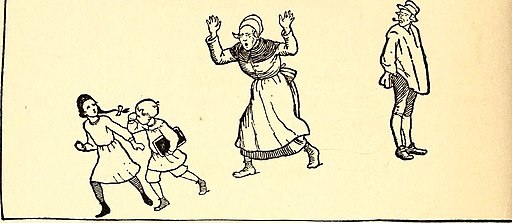

Georgie Porgie always did his work himself. From The Boyd Smith Mother Goose, public domain via Internet Archive Book Images on Flickr.

Georgie Porgie always did his work himself. From The Boyd Smith Mother Goose, public domain via Internet Archive Book Images on Flickr. This is a seven by nine smile one can only dream of. The Smile of a Cheshire Cat by Brian, CC by 2.0 via Flickr.

This is a seven by nine smile one can only dream of. The Smile of a Cheshire Cat by Brian, CC by 2.0 via Flickr.The question has never been answered. The OED found the first occurrence of the phrase in print in 1909. This is exactly the date the letter writer had in mind. By the way, while working on my prospective dictionary of idioms, I made a list of questions in Notes and Queries that produced no replies. The list is instructive. I still have no idea whether let George do it is an Americanism or whether it only flourished on American soil (if so, why so late?), and what it has to do with its French analog. It does not appear in English dictionaries of familiar quotations. On the Internet, one can find some informative correspondence about the origin of the phrase. But the sought-after etymology is lost. Perhaps some of our readers know something about the matter. Their suggestions are welcome.

If I am not mistaken, the next two phrases are not in the OED. As I read in a 1909 publication, “the American phrase seven by nine is generally applied to a laugh or smile of latitude more than usually benign, as if meaning the length and width thereof and at the same time playing upon the word benign.” (Is the reference to benign an example of folk etymology?) I would like to mention a problem with words and expression called American in dictionaries. They produce the impression that all English speakers in the United States know them. Yet this term is a trap into which unwary foreigners who try to learn “real American” from books often fall. They use such words and idioms and don’t realize that they may have stumbled upon a piece of local or forgotten usage or slang. For example, now, more than half a century after the radio show “Let George do it,” young people seldom recognize the collocation.

This is the preeminent Connecticut Yankee. Oxford World’s Classic edition.

This is the preeminent Connecticut Yankee. Oxford World’s Classic edition.In any case, at the beginning of the twentieth century, the American phrase a seven by nine politician existed. Here is a commentary from a Connecticut Yankee, if I may plagiarize Mark Twain. The phrase is said to apply to a man “of too limited abilities, force, or outlook to cut much of any. [It] refers to the old-fashioned windowpanes, before the time when glass filling the whole or half of the sash was common; these were ‘seven by nine’ in hundreds of thousands of farm or village houses…. Its nearest synonym is ‘peanut’ politician, that is, bearing the same relation to large political ideas and plans as a peanut vendor, or huckster of peanuts and roast chestnuts in a pushcart, does to large mercantile activities. Neither name implies a low position or importance: only the pettiness of the issues which can form the staple of the activities…. Similar names are ‘two-cent’ or ‘two-for-a cent’ (‘ha-penny’ comes just between) or huckleberry (‘whortleberry’) politician: the last having the same implication as ‘peanut’—one peddles huckleberries by the quart.”

What a rich display of dated slang! Peanuts do not fare too well in American English: cheap payments are “just peanuts,” and peanut politics, that is, “petty politics” (often with reference to corruption) is a phrase one can still hear around. The explanation quoted above may very well be correct, but I notice with some unease that seven and nine are the favorites of numerous idioms and folklore, and here they occur in what was known a hundred years ago, and in an entirely different context, as entente cordiale. See the posts for April 6, 2016 and June 19, 2019. Does the phase seven by nine really have an ascertainable foundation in reality, or is the use of seven and nine in it as mysterious as in nine tailors make a man and seven-league boots?

La entente cordiale. From L’oncle de l’Europe, public domain via Internet Archive Book Images on Flickr.

La entente cordiale. From L’oncle de l’Europe, public domain via Internet Archive Book Images on Flickr.The unresolved riddle of the phrase let George do it again reminds us of the fact that many typical American words and expression were coined in England, came into desuetude there, but survived in the New World. That is why the definition of an Americanism is often ambiguous. Compare what I wrote about the idiom to get down to brass tacks in April 15, 2015.

I would like to repeat that, if my discussion of American idioms presents interest, I may perhaps write one more such essay in the nearest future.

Feature image credit: Daderot, public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Some American phrases appeared first on OUPblog.

Friedrich Schiller on Beauty and Aesthetics – Philosopher of the Month

German poet and playwright, Friedrich Schiller is considered a profound and influential philosopher. His philosophical-aesthetic writings played an important role in shaping the development of German idealism and Romanticism in one of the most prolific periods of German philosophy and literature. Those writings are primarily concerned with the redemptive value of the arts and beauty in human existence. He was immensely well-known for his literary accomplishments, and his influence on German literature, having written a number of successful historical dramas, such as The Robbers, Maria Stuart, and the trilogy Wallenstein. His poem, “Ode to Joy” was set in the final movement of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony and later enshrined in the European Hymn.

Born in 1759, in Marbach in the state of Württemberg in southwest Germany, son of an army surgeon, Schiller attended the military academy of Karl Eugen, Duke of Württemberg and emerged as an army doctor in 1780. He however rebelled against military disciplines and developed interests in the arts and humanities, reading and writing, “Sturm and Drang,” a German literary and artistic movement of the late 18th century that rejected the prevailing neo-classicism in favour of subjectivity, emotional turmoil, artistic creativity, and the beauty of nature. His first play The Robbers (1781), the story about a nobleman turned robber on the themes of freedom and rebellion, caused a sensation on its first performance. Forbidden by Karl Eugen to pursue his literary ambitions, Schiller fled in 1782 to Manheim in Palatinate and became a resident playwright at the Manheim National Theatre from 1783-1784. From this period on, he authored many Sturm and Drang plays such as Don Carlos (1787), and two major histories, a history of the conflict between Spain and the Netherlands in the 16th century and a popular history of the Thirty Years War. In 1787, he settled in Weimar, then German’s literary capital, and was appointed, thanks to the Goethe’s recommendation, an honorary professor of history at the University of Jena, where he lectured on history and aesthetics. His health broke down from overwork in 1791, but received patrons from the Danish aristocrats allowing him to recover and turn his full attention to philosophy and the study of Kant’s idealism.

In the area of philosophy, Schiller’s works principally concern aesthetics but they also made important contributions to the fields of ethics, metaphysics, ontology, and political theory. The central influence in the development of Schiller’s aesthetics was Immanuel Kant, whom Schiller began to study in 1791 but was also influenced by many other classical and eighteenth century writers such as Alexander Gottlieb Baumgarten, Johann Georg Sulzer, Moses Mendelssohn, Burke, and Lord Shaftesbury. His major treatises on aesthetics written between 1791 and 1795 consist of Kallias Letters, Letters on Aesthetic Education, On Grace and Dignity, and On Naïve and Sentimental Poetry.

Graff, Anton. Porträt des Friedrich von Schiller. Between circa 1786 and circa 1791, Kügelgenhaus Museum der Dresdner Romantik, Dresden. Public Domain via Wikimedia

Graff, Anton. Porträt des Friedrich von Schiller. Between circa 1786 and circa 1791, Kügelgenhaus Museum der Dresdner Romantik, Dresden. Public Domain via WikimediaKallias Letters (1793) explicates what Schiller meant by defining beauty as ‘freedom in appearance’. Schiller was disappointed with Kant’s theory which demoted beauty to a subjective quality and wanted to establish the objective concept of beauty. Kant regarded that there could be no objective principle of beauty and that aesthetic experience refers only to pleasure felt by the subject, not to any property of the object. Schiller however further developed that in order to judge something beautiful, we have to consider the inherent qualities of the object itself: namely, whether the object is self-determining, “being-determined-through-itself of the thing”, in the sense that it is free from external forces and allowed to express its inner nature. According to him, we cannot have an experience of beauty if the aesthetic object is subject to constraints, whether moral, desire or physical. We should not apply any concepts to it but should view it as if it were free. This view is in line with Kant’s Critique of Judgment which stresses that work of art is beautiful if it appears like nature and does not conform to the rules of art. In “On Grace and Dignity” (1793), he elaborated on the notion of ‘the beautiful soul’ as one in which “sensuality and reason, duty and inclination, are harmonized, and grace is its expression in appearance.” In this work, Schiller aimed to show how the concept of grace can bridge the divide between morality and aesthetic in Kantian philosophy.

Letters of Aesthetic Education (1795) is Schiller’s most influential work and the clearest expression of his belief that art, rather than religion, plays a central role in the moral education of an individual. Expressed in a series of letters to his new patron Friedrich Christian, the treatise was written immediately during the French Revolution at the beginning of the 1793-94 Reign of Terror. Like many of his contemporaries, Schiller admired the revolutionary ideas of liberty, equality, fraternity, and the sacred right of man but disapproved of its violent method and bloody executions such as the execution of Robespierre. The treatise thus blends political analysis, an account of Kant’s transcendental aesthetics and a critique of the Enlightenment to define the relationship between art, beauty, and morality. Since the revolution had not achieved a political stability, Schiller saw art as the key to the realization of morality and the establishment of a free society since art has the powers to educate sensibility, cultivate people’s moral awareness and inspire them to act morally according to the principles of reason.

At the heart of this treatise is his argument that we are driven by two fundamental drives of human natures, the “physical” or “sensuous” drive which impels man to fulfill his material and physical needs, and the “formal” drive, which proceeds from man’s rational and intellectual nature. Art and beauty come into play by ennobling his sensuous nature and harmonizing the conflicts between the two basic drives. This unity awakens the existence of the third drive, “play drive”, in which we are no longer constrained by physical needs or moral duty and are able to realize our full potentials.

On Naïve and Sentimental Poetry (1795–6), which appeared in Schiller’s journal, Die Horen is also another important work in the history of aesthetics. Its poetic theory about the two different types of poetry and our relationship to nature had an impact on the development of Romanticism and also inspired Friedrich Schlegal’s ideal of Romantic poetry because of its concept of the sentimental. Schiller followed the premise à la Kant in Critique of Judgment that we take pleasure in the nature (birdsong, animals, gardens, flowers etc.) rather than artificial objects because they are natural. He further thought that our pleasure in nature is more moral than aesthetic because it evokes the feelings of harmony and unity that we have lost and to which we long to return. In contrast to the “naïve” classical poetry, which tended to realism, the modern or sentimental poetry of Schiller’s era is self-reflective and idealizes its objects.

Schiller’s remarkable period of intense philosophical output ended in 1796 when he returned to literature and play writing. This was also an extraordinary literary period in which he produced a number of successful plays, the tragic trilogy Wallenstein, and four major dramas, Maria Stuart, The Maid of Orleans, The Bride of Messina and Wilhelm Tell. He also collaborated with Goethe on a literary journal Die Horen (1795-7) to raise the standard of art and literature, and also on Xenien, a series of satirical epigrams against the critics who opposed their artistic visions.

Due to poor health, Schiller died at the age of forty- five. He was admired by the dominant intellectuals of the time, Friedrich Schlegel, Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph von Schelling, Friedrich Hölderlin, and Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel. His essays on the role of art have been influential for their insights into aesthetics and rank among Germany’s most profound and sophisticated works.

Featured Image: Neuschwanstein Castle, Schwangau, Germany. Photo by Ashley Knedler on UnsplashThe post Friedrich Schiller on Beauty and Aesthetics – Philosopher of the Month appeared first on OUPblog.

August 6, 2019

How quantitative thinking shaped our worldview

Over the past couple of months or so, I’ve had a few opportunities to speak with individuals and groups about “us” — who we are and how we came to be ourselves. By “us,” I do not mean self-reflection and the introspection of following self-help conventions; rather, I mean the “us” to be our worldview: our thinking, acting, and doing. Ordinary actions that are part of our daily living, like looking at the weather to decide what to wear before dressing; or starting our car and driving a familiar route (knowing in advance that this is not the most direct course but does have less traffic); or, occasionally, checking the stock market averages to see the current value of our investments or a retirement account; or even—when anticipating an Amazon delivery, worrying about who to call if you think you package was stolen. Nowadays these things can be reliably forecast. Weather, at least for the next few days, is nearly-always accurately known. Driving routes are predictable events (just ask the delivery services person for his route map, which is updated each day or even hourly).

Each event demands a new outlook—one that would have been unimaginable just a few years ago. By these events we have a quantitative outlook as our frame of reference. We view things as calculable (that is, reliably predictable) – and typically in terms of odds or likelihood of occurrence. We are now quantitative beings. Quantitative thinking is our inclination to view natural and everyday phenomena through a lens of measurable events, with forecasts, odds, predictions, and likelihood playing a dominant part. Mathematically-based estimates are much more accurate than the mere guesses of years’ past.

But how did we get this worldview? And, how did it come about so quietly and quickly? We were changed and did not even notice until the change was so complete it was our perspective on all things.

This worldview is unlike anything humankind had before; and, it came about because of a momentous human achievement. Namely, we had learned how to measure uncertainty. Probability as a science was invented. By probability theory we now have correlations, reliable predictions, regressions, the bell-shaped curve for studying social phenomena, Bayesian estimation (MS Windows is based on this) and the psychometrics of educational testing (something that effects each one of us).

Unexpectedly and surprisingly, we came to this worldview only recently, within the past two hundred years or so, compared to more than 6,000 years of human history. Even more astonishing is the fact that the change to the new worldview can be traced to just a few (about 50 or so) people. They, almost single-handedly, invented probability theory: the science that gives us methods for calculating odds, probability and reliable forecasts.

Imaginably, this worldview impacts each of us. Quantification is now everywhere in our daily lives, such as in the ubiquitous microchip in smartphones, cars, and appliances. Quantification is also essential in business, engineering, medicine, economics, and elsewhere.

I was watching TV where a prominent ad ran that touted Microsoft’s use of artificial intelligence to raise crop production, thus one acre of land can now feed such-and-such many more people than before. My thoughts immediately went to probability theory; which is the very basis of AI. (Hence, by the ad, more food)—all directly stemming from the imaginative work of Adrien-Marie Legendre and Carl Gauss, Thomas Bayes, and others. I am very glad to tell their story.

Later that day, I watched a full episode of the popular game show Deal or No Deal (originally broadcast in England and later transferred to America). It’s a perfect conditional probability! Once again, probability theory in action. And, it fits neatly into our contemporary, quantitative mindset.

Featured image by Victor Rodriguez on Unsplash.

The post How quantitative thinking shaped our worldview appeared first on OUPblog.

How the Eurovision Song Contest has been depoliticized

When Duncan Laurence of the Netherlands briefly acknowledged his victory in the 2019 Eurovision Song Contest with the dedication, “this is to music first, always,” he was making a claim that most viewers would have found unobjectionable. Laurence’s hopefulness notwithstanding, the real position of music in the 2019 Eurovision Grand Finale on 18 May 2019 in Tel Aviv was more troubling than secure. From the moment that Israel’s Netta Barzilai had won the 2018 Eurovision in Lisbon, the first return of the Eurovision to Israel since Dana International had won in 1998 promised controversy. There was little to stop the rising European conflict between inclusion and exclusion—the rights of national ownership and belonging—from spilling over into an international music competition, born of the Cold War, but coinciding with the week of Naqba, the Palestinian day of “Catastrophe.”

The European Broadcasting Union and the Israeli hosts followed tradition by taking every step possible to exclude political symbols from entering the contest. Song lyrics, for example, must be stripped of political meaning or risk elimination. The broadcasting union goes to extreme measures to prevent border conflicts between competing nations, from finding place in songs. Minority rights, legal restrictions on LGBTQ rights in competing nations, the refugee crisis, the #MeToo movement, and the rise of right-wing nationalism find their way into songs in coded form more often than not.

The depoliticization of the Eurovision by media organizations in recent years has grown disproportionately in comparison with the social issues it seeks to silence. The national song entries suffer accordingly, replacing a poetics of critical eloquence with glitzy performance. The Tel Aviv Eurovision show, for example, displayed more pyrotechnics and acrobatics than ever before. Intermission acts mustered Eurovision stars from previous years, who combined forces in one mash-up after the other, to turn European history—the Cold War, the break-up of the Soviet Union, the formation of the European Union, civil war and ethnic cleansing in southeastern Europe—into one big colorful panorama. When Madonna was flown to the Eurovision to perform the final intermission act of the Grand Finale, the excess would have reached its ultimate crescendo had Madonna risen to an occasion that, clearly, she understood not in the least.

The 2019 Eurovision also contained voices of quiet resistance, singers and songwriters who were responding to a more troubling reality in Europe. Against the backdrop of relentless show it was often difficult to hear these voices, the marginal representing the marginalized. The most subtle of such voices responding to a more troubling Europe was that of Tamara Todevska, whose song, “Proud,” was the first-ever entry for North Macedonia. Singing a gentle ballad about the relationships between women, especially multi-generational relationships, Todevska reflected on the difficulties of inclusion and harassment (Girl, for every tear the world makes you cry/ Hold on to me, I am always on your side. . . ./ Tell them, this is me and thanks to you I’m proud). Her song received the most jury votes from national committees and eventually placed seventh.

There were other singers voicing resistance, ranging from the intensely personal to the most political. The Norwegian entry, the trio KEiino, performed “Spirit in the Sky,” posing questions about cultural survival in a natural world endangered by climate change, but then elevating the questions to Indigenous rights with Sámi lyrics in the chorus. France’s Bilal Hassani, a drag performer of North African heritage, eschewed subtlety altogether (I am me, and I know I will always be/ Je suis free, oui j’invente ma vie) when performing the intertextual LGBTQ “Roi” with dancers who had different disabilities.

As the 2019 Eurovision Grand Finale drew to its close, it became clear that the quieter voices, those who recognized that Europe was larger than national politics and the clichés of spectacle, just might carry the day. Bilal Hassani’s “Roi” (King) perhaps asked too much in 2019, but Mahmood’s “Soldi” (Money), about broken family relations, sung by a Muslim representing Italy, moved to second place. When the tallies were complete, it was one of the gentlest of all 2019 entries, Duncan Laurence’s “Arcade,” that would bring the 2020 Eurovision to the Netherlands. Beautifully crafted and magnificently sung, “Arcade” soared above Eurovision 2019 (A broken heart is all that’s left. . . ./ I carried it, carried it, carried it home):

Featured Image credit: “Duncan Laurence (Netherlands 2019)” by Martin Fjellanger, Eurovision Norway, EuroVisionary is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

The post How the Eurovision Song Contest has been depoliticized appeared first on OUPblog.

August 5, 2019

McCarthyism and the legacy of the federal loyalty program [video]

As World War I finally concluded on November 11, 1918, the United States became swept up in a fear-driven, anti-communist movement, following the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution. From 1919-1920, the United States entrenched itself in the First Red Scare, the American public anxious at the prospect of communism spreading across continents. The first Red Scare occurred in the global context of the struggle by contemporaries to envision their future amid the chaos and horror wrought by World War I. However, the Red Scare resurged in the late 1940s well into the 1950s in the United States during the opening phases of the Cold War with the Soviet Union. Once again, the United States found itself in a state of anti-communist unrest, yet the second Red Scare lasted nearly a decade.

Senator Joseph McCarthy of Wisconsin made himself famous in 1950 by claiming that large numbers of Communists had infiltrated the U.S. State Department. McCarthy’s fear-mongering and anti-communist maneuvers yielded “McCarthyism”: the tactic of undermining political opponents by making unsubstantiated attacks on their loyalty to the United States. The second Red Scare predated and outlasted McCarthy and its machinery far exceeded the reach of a single maverick politician.

As anti-communist sentiments heightened, the government and nongovernmental actors at national, state, and local levels deemed the American Communist Party as a serious threat to national security. The identification and punishing of Communists, as well as their alleged sympathizers, spawned a McCarthy-era witch hunt for Communists, forcing many thousands of Americans to face congressional committee hearings, FBI investigations, loyalty tests, and sedition laws. The Communist prejudice continued, creating negative consequences for those accused, ranging from imprisonment to deportation, loss of passport, or, most commonly, long-term unemployment.

This video delves into the lasting legacy of the second Red Scare, as well as McCarthyism in American culture, highlighting the strain of Communist fear on working-class Americans and Civil Rights activists.

Featured image credit: “Blurry American Flag” by Filip Bunkens. Public domain via Unsplash.

The post McCarthyism and the legacy of the federal loyalty program [video] appeared first on OUPblog.

August 4, 2019

How to construct palindromes

A palindrome is a word or phrase that reads the same way forwards and backwards, like kayak or Madam, I’m Adam. The word comes to us from palindromos, made up of a pair of Greek roots: palin (meaning “again”) and dromos (meaning “way, direction”). It occurs in English as early as the seventeenth century, when the poet and playwright Ben Jonson referred to “curious palindromes.”

Some palindromes, the simplest sort, are reversible words, often with a consonant-vowel-consonant vowel-consonant (or CVCVC) spelling, like civic, level, dewed, radar, refer, rotor, and tenet. Shorter palindromes are common too, like pup, mom, and wow. Longer ones include racecar and rotator.

The alternating consonant-vowel shapes is convenient but not necessary, and palindromes like noon, deed, boob, (with a CVVC shape), deified and reifier (with a CVVCVVC shape), and redder (with a CVCCVC shape) exist as well. If you ignore the hyphen between its parts, the CVCCVC compound pull-up works as well.

Some fans of this sort of wordplay insist that true palindromes must spell the same word in both directions, so live and evil, dessert and tressed, and era and are would not count as true palindromes. When words can be reversed but the meaning changes, they are sometimes called heteropalindromes. I’m not that fussy though. They are all palindromes to me.

To understand how to make palindromes, it helps to think about the combinations that can begin and end words. English syllables can begin with a single consonant letter or end with letter clusters like thw, dw, tw, thr, dr, tr, kw, qu, cr, kr, kn, cl, kl, pr, fr, br, gr, pl, ph, fl, bl, and gl, as in thwart, dwindle, tweet, through, dream, train, kwanza, queen, creek, kraut, know, pring, fret, brew, gray, play, phone, fly, and glow. But many of these clusters don’t occur in reverse at the end of words. At the end of words, we find wd, wt, rd, rt, rc, rk, lc, lk, rp, rf, rb, rg, pl, lf, and lb, as in lewd, newt, bard, cart, arc, talc, walk, carp, arf, verb, berg, kelp, calf, and bulb. Of these, the reversible combinations are few: dr, tr, cr, kr, pr, br, gr, pl, and fl: ward/draw, bard/drab, trap/part, marc/cram, knob/bonk, prep/perp, brag/garb, grub/burg, plug/gulp, flow/wolf, flog/golf.

The suffixes –s and –ed are especially helpful, since they can create plural and possessive nouns and present and past tense verbs. The letter s is also very common in two- and three-letter consonant clusters at the beginning of a word: sleep/peels, spin/nips, stab/bats, stub/buts, snub/buns, straw/warts, and slip-up/pupils. And the syllable de- can also occur at the beginning of words: denim/mined, devil/lived, debut/tubed, decaf/faced, decal/laced, demit/timed, and desuffused.

Beyond being reversible themselves, words can be combined to make palindromic phrases and even sentence-long palindromes, from simple ones like “No, son,” and “Sue us” to longer sentences like “Do geese see God?” or “Step on no pets.” The strategic use of a semicolon gives us the compound sentence “Deliver no evil; live on reviled.” It is even possible to create a palindrome that goes on forever. How? If you embed the word ever into the palindrome never even you can get never ever even, never ever ever even, and so on to infinity.

Making palindromes is something of an art form. Phrases and sentences are often poetical rather than strictly grammatical. And they sometimes work best when combined with illustrations, as in John Agee’s books Go Hang a Salami! I’m a Lasagna Hog and So Many Dynamos!, which offer up such entertaining combinations as Llama mall, Dr. Awkward, or Mr. Alarm.

If you want to try to create some palindromes yourself, here are some tips:

Start with a list of reversible words. In addition to the words already given there are pairs like: room/moor, edit/tide doom/mood, time/emit, avid/diva, bad/dab, rail/liar, raj/jar and many more.

Reversible names like Ada, Bob, Viv, Eve, Anna, Hannah, and Mada/Adam, can be a good way to begin or end a palindrome.

Palindromists don’t worry much about punctuation, so gateman’s nametag and bro’s orb will count.

There are some common palindrome frames you can use to practice with, like the ones below, adapted from Howard Bergerson’s 1973 book, Palindromes and Anagrams.

“Was it a ___ I saw?”

You need a word that ends in –at.

“I saw _______; ______ was I.”

The first blank is a plural noun.

“_____ not on _____”

Since not on is itself reversible, all you need is a reversible word that makes sense. Look for a verb that reverses as a noun.

“Ma is as_____________ as I am.”

Ma is as reversed gives s plus as I am, so you’re a looking for a word that begins with an s to fill in the blank.

“______ if I _______.”

Look for a verb that is a palindrome.

How did you do? Did you come up with these or similar correct answers?

“Was it a rat I saw?”

“I saw desserts; stressed was I.”

“Live not on evil.”

“Ma is as selfless as I am.”

“Pull up if I pull up.”

Until next month, mix a maxim.

Featured image: “Red Bull Formula 1” by Hanson Lu. Public domain via Unsplash.

The post How to construct palindromes appeared first on OUPblog.

August 3, 2019

The international reporting you never see

It’s your morning routine. You open your tablet, go to your favorite news app, and skim the headlines over a cup of coffee. Your screen floods with images of election protests in one region of the world, wars in another region, and diplomatic skirmishes in another. If you tap on an image and dive in for more information, you might see the familiar name or face of the foreign correspondent who is standing in the very places you’re reading about. This is the person who goes where you can’t go and tells you what’s happening there.

But this journalist probably couldn’t have covered the story without the help of someone whose name and face is nowhere to be found: the “fixer.” News fixers are locally-based media workers who help foreign correspondents translate languages they don’t know, navigate terrain with which they are unfamiliar, and interview sources who otherwise might not talk to them. And they’re everywhere. There are fixers working in Beirut, in Mexico City, in Moscow, in Sweden, in Los Angeles, and in London.

These media workers are usually professional journalists in their own right, but they’re called fixers when they agree to help the correspondents who visit their regions from somewhere else. The idea is that the fixer will help a foreign journalist in almost every respect—except with writing the final story or appearing in the final television report. Fixers are usually blocked from contributing to the final story, and because of this, they are often relegated to the shadows of the international news industries.

“I’ve had situations where, you’re the guy on the ground, and you get to do most of the ‘muscle,’ and let’s say, ‘dirty work,’” said an anonymous fixer who works with foreign journalists in Mexico City. “They come, they go, and then you stay, and then, people win prizes for your work.”

Not only can this undervalued work be physically and emotionally exhausting—it can also put these local media workers in significant danger, especially if they are helping foreign correspondents cover sensitive stories. “It is too risky for me to stay in the same place,” said one anonymous news fixer based in Somalia. “These guys [from Al-Shabaab] will always try to hunt down and assassinate me because of the work I am doing. Because I have worked with so many international people.”

Chris Knittel, a US-based fixer who helps journalists and documentarians cover stories about gang violence, also worries about safety. “Once the cameras and crew are gone you must deal with any aftermath or perceived problem that may arise after the film airs,” said Knittel. “If a gang member thinks that the editing team didn’t alter his voice enough, you may have an entire blood set gunning for your head.”

Despite the risks that news fixers face, they still don’t get much protection from the vast majority of the news organizations that depend so heavily on their labor. Few news outlets provide local fixers with insurance, with their own safety equipment, or with systematic assistance in evacuating their countries when necessary.

While individual journalists might try to protect the local employees they hire, they can’t do much without the backing of their news outlet. But Leena Saidi, a fixer working in Beirut, said that news organizations should take more care of their fixers, at the very least, by giving them hostile environment training. This kind of training provides journalists with tips on how to safely navigate conflict zones or other physically dangerous environments.

“If a company uses a fixer on a regular basis, then I think they’re just as responsible for making sure that fixer has that training,” said Saidi. “It’s the right thing.”

While organizations such as the Frontline Club and publications like the Columbia Journalism Review have started to report on these problems, there is still much work to be done. Not only do news organizations fail to talk about news fixers enough; there are also only a handful of academics who have discussed news fixers in their work. Journalism scholar Colleen Murrell is one exception, with her groundbreaking book, Foreign Correspondents and International Newsgathering: the Role of Fixers. Jerry Palmer and Victoria Fontan have also published academic research on the topic. These studies primarily look at fixers working in Iraq, and both studies emphasize the perspectives of the foreign correspondents over those of the fixers themselves.

But foreign correspondents couldn’t cover their stories without the help of local fixers. This is why it is vital that journalism scholars and practitioners also hear the news fixers’ own perspectives. We need to pay more attention to the stories that fixers tell about their labor, stories that show the deeply collaborative nature of international news reporting in the 21st century.

The post The international reporting you never see appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers