Oxford University Press's Blog, page 177

September 6, 2019

Ten things you need to know to become a police officer

Applying to become a police officer in the UK is undoubtedly complex and challenging. While there are variations in the minimum qualifications to join, many requirements for applicants are common to all forces. Applicants must be at least 18 years, must have been resident in the UK for more than three years, and must not have a criminal record. The format of Recruitment Assessment Centres and the health and fitness requirements are the same for all forces. Similarly, all applicants who believe they have a disability, such as dyslexia, can make a declaration on their application form. Afterwards, the force will contact them to find out if they would like to apply for reasonable adjustments. There are some differences in the recruitment process across the UK from force to force, and the eligibility criteria can occasionally change. Differences include, for example, whether a full driving licence is required or if the applicant needs to live within the police force area. The only certain way of obtaining accurate and definitive advice about vacancies and the application process is to look at the websites for each force the applicant is considering.

To help with your application to be a police officer, here are ten hints:

Visit the local police station and ask regular officers about the work from their perspective.Take time to consider whether the role of police officer is appropriate for you, and if you are suited for a career as a police officer. A series of pre-application questions could help you decide.Parts of the application form and assessment centre are more likely to be competence-based, so plan how you will provide responses incorporating the competencies of a police officer. Analyse the competencies and decide what previous experiences from your everyday life you could refer to at interview to show you are the right person for the role.During the application process, you should be prepared to provide written and verbal replies to questions about what you have done in the past, to evidence individual competency. For example, if the question relates to team working, your responses should be about what you yourself did within the team, not what the team did as a whole.Research the force you have applied. This will reap benefits in the application stages. What is its core business? What are its current priorities and what is its vision or mission? Are there wider external factors that influence the business? Think about the questions recruiters might ask, based on this research and the job advertisement details.Each part of the recruitment process is no less important than the other, so whether you are completing situational judgement tasks in the initial stages, writing an application form, or attending an assessment centre, plan out and prepare for each stage of the application process.Consider attending a preparation course to help with applications. Some companies provide coaching for the role play and the interview elements of the assessment centre, for example, and can boost the confidence of applicants.At assessment centres and interviews, you should dress smartly to evidence good judgement.In an interview, you should be prepared to comment on your own values and ethics as well as those of the police force you are applying to.Usually you can only apply to one force at any one time. If you apply to a force and are unsuccessful, you may have to wait six months before reapplying.Other police officer entry routes are available, including direct entry inspector and superintendent programmes for applicants who already have middle management or senior management/director leadership skills. Alternatively, there is the National Graduate Leadership Programme 2020, for outstanding graduates wishing to become police leaders in either uniform or detective roles. Should you wish to serve your community as a police officer, but have commitments that prevent you from taking up a full-time salaried position, there are also volunteering opportunities in the special constabulary.

Good luck!

Featured image credit: Two-white-blue-yellow vehicles. CCO creative commons via Unsplash .

The post Ten things you need to know to become a police officer appeared first on OUPblog.

September 4, 2019

The last shot at American Idioms

The use of metaphors is relatively late in the modern European languages; it is, in principle, a post-Renaissance phenomenon. The same holds for the idioms based on metaphors. No one in the days of Beowulf and perhaps even of Chaucer would have coined the phrase to lose one’s marbles “to become insane,” even if so long ago boys were as intent on collecting marbles as was Tom Sawyer.

American English is about five centuries old, and, not unexpectedly, quite a few phrases of this type arose in it. Some became universally known; others never crossed the ocean eastwards. As with many words first recorded overseas, we may come across collocations that had some currency in rural British dialects but did not catch the attention of literary people in England. Yet to lose one’s marbles does not appear to be one of such cases. The game of marbles in the form familiar to us originated in Germany (or so they say) and may have been popularized in the United States by the children of German immigrants (pure guesswork). To lose one’s marbles may go back to the frustration of a player who lost them, though the connection is not too convincing and other suggestions also exist. In any case, the idiom should remain with the label “American.”

A similar case is between a rock and a hard place. It turned up in the early 1920s, mainly in Arizona, in the sense “to be bankrupt.” The reference is supposed to be to the difficulty of navigating between Scylla and Charybdis. But why should such an allusion to a Greek myth have occurred to some businessman in twentieth-century Arizona? If the current explanation is correct, the inventor must have been someone versed in old tales. In any case, we witness a common play with almost interchangeable synonyms: after all, rock is the same as hard place. A model for such a locution would be easy to find: compare between the Devil and the deep sea (the 1620s) and between the beetle and the block (first attested in a book in 1590; beetle was the name of a sledge-like instrument).

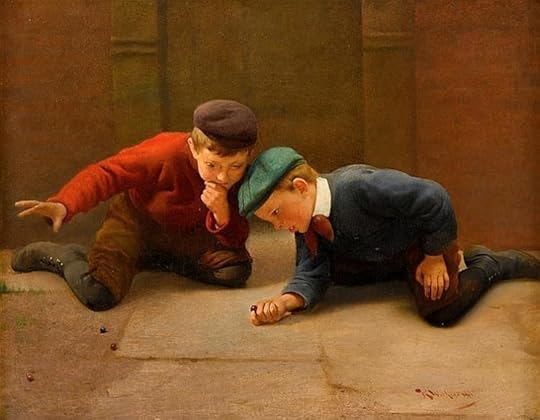

Play well, don’t lose your marbles! Image credit: “Game of Marbles” by Karl Witkowski. Public domain via Wikimedia.

Play well, don’t lose your marbles! Image credit: “Game of Marbles” by Karl Witkowski. Public domain via Wikimedia.The idioms that are certainly American are not many, and lists of them exist. However, in my rundown on them, I failed to find a mention of under the weather. No occurrence of it in texts predates 1827. In 1857, it was explained (by an Englishman) as going back to the phrase under the wind, that is, “protected from the wind,” but under the weather means “sick, indisposed.” Though the nautical origin of the phrase is likely, the OED does not risk an etymology. The reference may well be to some place on board a ship in which the weather (or seasickness) affects one in a negative way. One wonders why British sailors did not coin the phrase centuries earlier.

Not improbably, to talk through one’s hat “to talk insincerely or nonsense” also originated in American English. In any case, the earliest citation in the OED is from an American text (1888). The saying has been tentatively traced to the custom of standing for a short time in church and praying into one’s hat (and thus feigning a prayer?). According to another interpretation, the saying means “to talk big or nonsense.” Fine, but why through one’s hat?

Hats do not fare well in idioms. Think of mad hatters (mad as a hatter was discussed in the post for January 24, 2018). Also, a promise or rather a threat to eat one’s hat refers to doing such an improbable thing if something happens. No one knows how such a threat originated. Mr. Grimwig (Chapter 14 of Oliver Twist) promised to eat his head, not his hat, if Oliver returned to Mr. Brownlow’s home. (Of course someone with a name like Grimwig would have been happy to eat any part of his head or the whole of it.) But hat is hardly an alteration of head or heart (as has been suggested), because boots also occurred in this idiom. To eat one’s hat turned up in a text dated to 1767 and seems to be an Americanism.

Some idioms go back to the days of slavery. Today, they are, fortunately, only of historical interest, and, to understand them, we need a background story. On July 17, 2019, I cited the phrase a man and a brother. Gin work may also be mentioned in this context. I owe my knowledge of this collocation to an article in American Notes and Queries 9, 1971, p. 120 (which I’ll retell almost verbatim). The phrase meant “Little daily chores that must be done close around the farm house, as opposed to the harder all-day work of the farm.” In Salem, a central West Virginia town, some older people were told as children that the expression had originated in the Valley of Virginia. In that region, before the Civil War, male slaves who became too old or feeble to work in the fields were known generically as the “jims.” They were brought into the plantation house and given lighter work, “Jim Work,” in the house, yards, and out-buildings. Other farmers, whether slave-holders or not, picked up the term to designate work of lesser importance. It has been suggested that gin work (the same meaning) may be an alteration of Jim work.

Absolutely no rain! Image credit: “Quaker meeting in York” by Fran Lane. CC BY 1.0 via Wikimedia.

Absolutely no rain! Image credit: “Quaker meeting in York” by Fran Lane. CC BY 1.0 via Wikimedia.This story reminds us that sometimes, to understand an idiom, we have to decipher a seemingly incomprehensible word. Neither Jim nor gin makes sense in the phrase cited above: one has to know the “realities,” to understand the meaning. Or it may happen that, though the necessary situation looks deceptively clear, the whole sounds like a puzzle. Such is the seemingly enigmatic phrase it always rains Quaker week, an obvious Americanism. It was believed that the Friends’ (Orthodox) yearly meeting (April or May) invariably brought rain! Rain, like hat, is a relatively common guest in the world of idioms. For it rains cats and dogs see the post for March 21, 2007. This is a British phrase, but to rain on one’s parade “to ruin one’s plans; to be a wet blanket, as it were” is a piece of American slang. Many idioms require the help of the folklorist. Compare the post on to hang out the broom for February 10, 2016.

An ideal image of transatlantic independence. Image credit: “Hogs in Snow” by Eva Blue. Public domain via Unsplash.

An ideal image of transatlantic independence. Image credit: “Hogs in Snow” by Eva Blue. Public domain via Unsplash.Finally, we may bother about neither the obscurity of the word involved nor the emerging picture of the whole. We know what to be left in the lurch is, even though we cannot find this proverbial lurch on the map of the world. Nor are many people interested in discovering the nature of dander in to get one’s dander up, but, if you are one of them, read the post for September 6, 2017.

It is nice to finish this series with an idiom that celebrates independence, a much valued asset on both sides of the Atlantic. My choice is as independent as a hog on ice. The Century Dictionary connected hog with hog in the game of curling, but this interpretation has been contested. The phrase enjoyed some popularity around 1900 in the Midwest and was used ironically about people who paraded nonexistent independence. But why such a bizarre image? The inventor did indeed go the whole hog in trying to obfuscate us. As always in etymology, there are more questions than definitive answers. Difficulties are everywhere, but don’t despair. Hitch your wagon to a star! (Ralph Waldo Emerson).

Featured Image Credit: “Britannia between Scylla & Charybdi” by James Gillray. Public Domain via Wikimedia.

The post The last shot at American Idioms appeared first on OUPblog.

The science behind ironic consumption

When I turned 21, my friends brought me to a dive in East Atlanta called the Gravity Pub. The menu offered burnt tater tots, deep fried chili cheese dogs, and donut sandwiches. Happy hour featured rot-gut whiskey, red-eye gin, and one-dollar cans of Schlitz. We listened to Bon Jovi, Spice Girls, and a medley of yacht rock and boy band blue eyed soul crackling through rusty speakers. And we played Bingo. For prizes like Cookie Monster water wings, neon rave sticks, and Bible action figures. Ties were broken via hula-hoop competition.

I was a business student at the time. My marketing textbook told me that consumers seek out products that they like or that they think will help them project a desirable image. But this sounded very different than my experience at the Gravity Pub, where we were eating food, drinking alcohol, and listening to music that we thought was disgusting while playing a game meant for retirees to win prizes meant for children.

What was my textbook missing?

Ironic consumption.

My friends and I were not the first people to consume products ironically and we were certainly not the last. There is a strong dose of irony in every hipster cliché, from teardrop tattoos and prohibition-era mustaches to fanny packs and trucker hats. But ironic consumption isn’t limited to hipsters. You can see it in the popularity of ugly Christmas sweaters. You can see it when Michelin star restaurants serve macaroni and cheese, when movie snobs revel in the shoddy storytelling and production in The Room, and when liberal millennials attend Donald Trump rallies wrapped head-to-toe in MAGA paraphernalia.

What exactly is ironic consumption and why would someone want to use a product ironically rather than simply using a product they actually think is good?

In order to answer these questions, it helps to think about products as symbols that consumers use to communicate their interests and beliefs and to infer those of others. Normally, wearing a wedding ring says, “I’m taken,” listening to Justin Bieber says, “I’m a Belieber” (see the young woman in this cartoon in The New York Times), and getting a “Make America Great Again” tattoo says, “I support Donald Trump.” When consumers use a product ironically, however, they are attempting to reverse the product’s conventional meaning. By ironically wearing a Justin Bieber tee-shirt, the gentleman in the cartoon is emphatically saying that he is not a Belieber.

Image credit: “vegan hat” by Allie Smith. CC0 via Unsplash.

Image credit: “vegan hat” by Allie Smith. CC0 via Unsplash.Why go to the trouble of wearing this shirt ironically rather than simply wearing a shirt that says, “I hate Justin Beiber”?

It appears the ambiguity might be part of the appeal. In experiments in which observers are asked how they feel about people displaying certain products like this “Vegan” hat, their reactions depend upon context.

When participants are asked what they thought about the consumer (Do they like her? Do they think she is cool?) as well as why they think she is using the product (Is she being ironic or sincere?), their responses are interesting.

Participants were only likely to think that the consumer was using a product ironically if they were close enough to her to know that her opinions and beliefs are inconsistent with the product’s conventional meaning. For example, if I know that Madison is a carnivore, then I’m more likely to think that she is wearing the “vegan” hat ironically.

When the consumer used a product associated with the participant’s in-group (e.g., if the participant was himself a vegan), participants had less favorable impression of the consumer if they believed she was using the product ironically. Conversely, when the consumer uses a product that is not associated with the participant’s in-group (e.g., if the participant was himself a carnivore), participants had a more favorable impression if they believed the consumer was using the product ironically.

Ironic consumption lets people selectively signal one meaning to an in-group (which is likely to detect irony), and another to out-groups (which are unlikely to detect irony). For example, suppose I’m a meat eater with a handful of close meat-eating friends, and we are surrounded by neighbors who believe that eating meat is wrong. By ironically wearing a “Vegan” hat, I could make a good impression both on my vegetarian neighbors, who will think I am a fellow kale enthusiast, and my friends, who will realize that I am wearing the hat ironically.

The ambiguity associated with ironic consumption can help consumers not only when they are surrounded by people who with different tastes and beliefs, but also when they are uncertain about what message a product is going to signal. Irony offers a shield against anyone who might question your decision to try out an unusual product, like a dress made of balloons.

If your balloon dress catches on, you can claim that you can revel in the status that comes from wearing it before it became cool. If not, you can claim that you were wearing it ironically and thereby avoid the consequences of committing a fashion faux pas.

Featured image credit: “Couple ready for the Christmas time” by gpointstudio. CC0 by public domain via Shutterstock.

The post The science behind ironic consumption appeared first on OUPblog.

September 2, 2019

A new twist on rapid evolution in the Anthropocene

Many people view evolution as an extremely slow, long-term process by which organisms gradually adapt and diversify over millennia. But researchers also have found that rapid evolutionary change can occur over mere centuries, or even decades. Such ongoing rapid evolution is the focus of a fast-moving field of empirical work, made easier by new techniques for detailed DNA analyses in wild populations. Rapid evolution by natural selection can allow wild populations to adapt to new environments or keep pace with stressors in their home habitats.

Superimposed on this baseline of ongoing evolution is the increasingly prolific influence of human activities as a force of natural selection. The current epoch of earth’s history known as the Anthropocene – a period shaped by humans – is marked by massively altered ecosystems and alarming rates of species’ declines. Hundreds of scientific studies show that subtle but important evolutionary changes have allowed wild species to persist longer than they would be able to otherwise in the face of human-induced pressures, including climate change and introductions of invasive species.

A famous example of rapid evolution was caused by coal burning in mid-19th century Britain. Air pollution killed lichens and coated tree bark with dark soot, resulting in selection for the dark, cryptic form of the British peppered moth. Another textbook example of rapid evolution is selection for resistance to pesticides in many weeds and insects in a matter of years or decades. Likewise, pollution in rivers and lakes has selected for super-hardy fish in some cases, and selective harvesting of large-sized fish has led to heritable shifts towards smaller-sized individuals. Wild species that can’t acclimate or adapt to human-caused selection pressures may simply disappear.

Until now, the evolutionary effects of humans on wild, unmanaged species have mainly been inadvertent by-products of anthropogenic activities rather than intentionally planned interventions. It’s true that we have radically altered the genomes of domesticated plants and animals, but these species typically do not affect the gene pools of wild populations unless they interbreed with wild relatives or escape to become self-sustaining on their own (think of feral pigs).

This may be about to change.

Already, incentives are mounting to genetically engineer non-domesticated species of commercial importance, such as vast tracts of forest trees that have been decimated by insect damage and diseases. A recent report by the US National Academies of Sciences and Medicine argues for the urgent need to engineer resistance genes into the germlines of harvested tree species. Meanwhile, the challenge of tinkering with the genes of non-model species has been greatly simplified by a new gene-editing tool known as CRISPR. Thus, we may be on the brink of engineering wild, free-living species very intentionally for the first time in their evolutionary history.

Another genetic engineering feat plays into this paradigm-shifting scenario. In the past few years, biochemical engineers have developed a powerful technique in which CRISPR is harnessed to a gene drive system. A gene drive can be inserted into the DNA of a wild species in tandem with various types of desired “cargo” genes. A cut-and-paste feature of the gene drive causes the inserted cargo genes to be inherited by all future offspring in a non-Mendelian fashion. In some cases, the cargo could be a resistance gene that protects a wild species from a deadly disease, or one that prevents it from serving as a vector for human pathogens. In other cases, the trait could lead to single-sex offspring (e.g., all male) or could cause sterility, yet it would still be driven into all interbreeding individuals, eventually causing the population to self-destruct. Some people have suggested that gene drives should be used to eradicate pest species, like invasive rodents on islands and feral cats that plague wildlife in Australia.

Australian feral cat. Photo credit: Tim Doherty

Australian feral cat. Photo credit: Tim Doherty Feral cat in an Australian national park. Photo credit: Andy Sheppard

Feral cat in an Australian national park. Photo credit: Andy SheppardBoth types of gene drive applications – for introducing a desired trait, or for eradicating unwanted populations – are actively being pursued by researchers who work with mosquito-borne pathogens. Likewise, academic researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Tufts University plan to genetically engineer wild, white-footed mice to make them resistant to the spirochete bacterium that causes Lyme disease. If small-scale experiments on islands are successful, these researchers may expand their efforts to include a gene drive designed to alter much larger populations of wild mice in the Lyme transmission cycle.

White-footed mouse, the focus of a genetic engineering project to combat Lyme disease. Photo credit: Michael Richardson

White-footed mouse, the focus of a genetic engineering project to combat Lyme disease. Photo credit: Michael RichardsonHowever, before wild organisms with novel genes and gene drive systems are released into the environment, regulatory agencies, other scientists, and the public will need to weigh in on the wisdom, likelihood of success, and potential risks of each proposed application. Because a gene drive could quickly sweep through all interbreeding individuals, extreme caution is needed to avoid unintentional and unwanted consequences of this futuristic mechanism for rapid evolution. Welcome to the evolutionary Anthropocene.

Featured image credit: “DNA String Biology 3D” by qimono. Free use via Pixabay

The post A new twist on rapid evolution in the Anthropocene appeared first on OUPblog.

September 1, 2019

Celebrating banned books week

Book banning is not a new phenomenon. The Catholic Church’s prohibition on books advocating heliocentrism lasted until 1758. In England, Thomas Bowdler lent his name to the practice of expurgating supposed vulgarity with the 1818 publication of The Family Shakespeare, edited by his sister.

In the US, the nineteenth century anti-vice activist Anthony Comstock enforced laws aimed at suppressing materials that were “obscene, lewd, or lascivious.” Included in that category were anatomy textbooks and materials on birth control. Among those indicted was Margaret Sanger, whose 1914 newspaper The Woman Rebel was deemed obscene.

Later attempts at book banning were directed at the likes of James Joyce’s Ulysses and D. H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover. In 1933, Judge John M. Woolsey overturned a federal ban of Ulysses, which had been in effect since 1922. Woolsey concluded that the book, while not to his liking, was serious art. Lawrence’s novel, banned in England, was published by an Italian publisher in 1928, and three decades later printed in the US by the Grove Press. Grove successfully defended the work in federal court in 1959, arguing that works could be both obscene and have redeeming social value. By 1964, the Supreme Court would agree in another Grove Press case involving Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer. By the end of the 1960s, a presidential Commission on Obscenity and Pornography, established by Lyndon Johnson, issued a controversial report concluding that “Federal, State, and Local legislation prohibiting the sale, exhibition, or distribution of sexual materials to consenting adults should be repealed.” The report was rejected by Congress.

By the end of the 1960s, a presidential Commission on Obscenity and Pornography, established by Lyndon Johnson, issued a controversial report concluding that “Federal, State, and Local legislation prohibiting the sale, exhibition, or distribution of sexual materials to consenting adults should be repealed.” The report was rejected by Congress.

By the late 1970s and early 1980s, books were increasingly being challenged in schools and libraries for social and political content. Students and parents pushed back, and in June of 1982, after a challenge by students in New York, the Supreme Court weighed in. The 5-4 decision in Island Trees School District v. Pico ruled that public schools could not remove books from school libraries “simply because they dislike the ideas contained in those books.” Among the eleven books that the school had attempted to remove were works by Kurt Vonnegut, Jr., Richard Wright, Alice Childress, Eldridge Cleaver, and Bernard Malamud.

That May, after the case had been argued but before the decision was handed down, banned books were showcased at the 1982 American Booksellers Association exposition in Anaheim, California. The ABA exhibit featured about five hundred supposedly dangerous books stacked inside locked metal cages. And in September of 1982, the American Library Association led the first banned book week celebration.

But challenges continued. And since 1990, the Library Association’s Office of Intellectual Freedom has kept track of challenged books, drawing on reports in the media and from librarians. Among the recent works on the ALA’s top ten lists are George by Alex Gino (2018), Thirteen Reasons Why by Jay Asher (2017), This One Summer by Mariko Tamaki and Jillian Tamaki (2016), and Looking for Alaska by John Green (2015). Among the most challenged over the years are To Kill a Mockingbird, The Catcher in the Rye, and the Captain Underpants series.

Happy reading.

Featured Image Credit: “ Old books in Shelves” by Roman Kraft. CC0 via Unsplash.

The post Celebrating banned books week appeared first on OUPblog.

August 30, 2019

It’s not just young people who are pre-drinking

Pre-drinking, the act of drinking at home before going out, is an issue of global concern due to its links with greater overall drinking across the night, and increased risk of assaults, injuries, and arrest. Generally people pre-drink due to the high cost of drinks in licensed premises, to socialize with friends, reduce social anxiety before going out, or to get drunk quickly.

Most of the pre-drinking research that exists has been undertaken in the United States but the practice has also been widely reported in literature from several European countries, as well as Brazil, Canada, and New Zealand. Whilst it is positive to acknowledge pre-drinking is recognized as a global concern given the international research output, inconsistencies between these studies prevent a clear understanding of international trends, including the influence of the each country’s culture on patterns of alcohol use.

Inconsistencies between international studies can include the definition of pre-drinking; in the United States, pre-drinking generally refers to the act of drinking before attending an event, such as a sports match, while in the UK and Australia pre-drinking refers to drinking at someone’s home before attending bars and nightclubs. There are also study methodology variations; US-based research generally utilizes samples of college students describing retrospective alcohol use, while research from other countries typically use street- or bar entrance-intercept surveys with nightlife goers.

These inconsistencies between studies results in uncertainty for policy-makers aiming to implement evidence-based strategies targeting risky pre-drinking behaviors among specific groups of the population.

Indeed, pre-drinking behaviors are largely country specific. One analysis of pre-drinking of respondents across 27 countries to determine the role of age and sex on pre-drinking showed a big disparity on a country level in those who engage with pre-drinking. Respondents from Greece, for instance, had a low uptake of pre-drinking, in comparison to respondents from Ireland, who had the highest uptake of pre-drinking. This may be in part due to socio-cultural differences in drinking patterns. For example, in Mediterranean countries like Greece and Italy, many people have a drink with dinner most nights, whereas in countries like Ireland and Australia, many people drink little during the week, but then binge drink on the weekends.

It is not just young people who are pre-drinking. While pre-drinking increases between age 16 and 21 years, as might be expected, surprisingly pre-drinking also increases again after the age of 30 for respondents for both men and women genders, generally from Brazil, Canada, and England amongst others. This could be due to people over 30 years who may be meeting at home for a few drinks to socialise with friends before going out to dinner or a bar.

Pre-drinking practices therefore are not limited to university-age consumers of alcohol, as might be expected.

The gender split between those who pre-drink and those who don’t is less defined than expected. More males engage in pre-drinking than females except for respondents from Canada and Denmark. Perhaps we need more research to understand the changing trends of alcohol consumption among females as well as robust measures of motives to pre-drink.

While there is some consensus around the motives of pre-drinking, such as economics, culture, (including drinking culture), socializing, what is clear is that pre-drinking typically contributes to overall drinking consumption on a night out. The consequence of the total drinking amount on a night out increasing, means the risks for assaults, injuries, and arrests also increase.

What is needed are greater policy measures that target pre-drinking. A recent evaluation of Government Policy measures to reduce alcohol fueled violence in Queensland, Australia suggest a number of recommendations that speak to a better understanding of pre-drinking. Some examples of these include “introduce a minimum unit price on alcohol”, “trial the introduction of government support scheme for original live music played before 22:00”, and the “ongoing independent evaluation and monitoring of alcohol-related harms”.

Nevertheless, given the country-specific variations and the disparities across age and sex in pre-drinking behaviors, more research from other countries is required to better understand the inter-play between alcohol policies designed to reduce alcohol-related harms and pre-drinking.

Featured Image Credit: “Drinks” by bridgesward. Via Pixabay.

The post It’s not just young people who are pre-drinking appeared first on OUPblog.

11 books that deal with contemporary government and comparative political science [Reading List]

Our Comparative Politics series deals with contemporary government and politics. Global in scope, books in the series are characterized by a stress on comparative analysis and strong methodological rigour. It is a series for not just students and teachers but for researchers of political science too. Books in the series range from coalition governance to parliaments throughout time to reforming democracy.

With the European Consortium for Political Research’s 2019 conference taking place this month, we’ve assembled a reading list of books that we publish in cooperation with the independent scholarly association.

The Reshaping of West European Party Politics

Long gone are the times when class-based political parties with extensive membership dominated politics. Instead, party politics has become issue-based. Christoffer Green-Pedersen’s book highlights the more complex party system agenda with the decline, but not disappearance, of macroeconomic issues as well as the rise in ‘new politics’ issues together with education and health care. It also presents a new model of issue competition among political parties based on a new coding of party manifestos.

Michael Koß offers a new approach to understanding the institutional development of parliaments. How can we explain the evolution of legislatures in Western Europe? This book analyses ninety procedural reforms which restructured control over the plenary agenda and committee power in Britain, France, Sweden, and Germany between 1866 and 2015.

Read a free chapter here

Inequality After the Transition

Ekrem Karakoç’s book is an all-encompassing examination of the origins, increase, and persistence of inequality in new democracies. It challenges the conventional thinking found in much of the democratization-inequality literature, and offers a new theory. It speaks simultaneously to literature of democratization, party systems, social policy, and inequality to explain why democracies are not able to fulfill their promise to the disadvantaged and why they cannot achieve income equality.

Read a free chapter here

Democracy and the Cartelization of Political Parties

This book traces the evolution of parties from the model of the mass party, through the catch-all party model, to argue that by the late 20th century the principal governing parties and were effectively forming a cartel, in which the form of competition might remain, and indeed even appear to intensify, while its substance was increasingly hollowed out. Richard S. Katz and Peter Mair examine what cartelization means for parties and party systems, and what cartelization of the parties means for the future of democracy

Read a free chapter here

From Party Politics to Personalized Politics?

What do Beppe Grillo, Silvio Berlusconi, Emmanuel Macron (and also Donald Trump) have in common? They are prime examples of the personalization of politics and the decline of political parties. Gideon Rahat and Ofer Kenig provide fresh new insights into the study of both party change and political personalization through a cross-national comparative analysis

Read a free chapter here

Multi-Level Electoral Politics

This book explains how party and voter behaviour in a given election is affected by the existence of multiple electoral arenas. It focuses on three levels of elections in France, Germany, and Spain and produces useful insights about politics from these three major EU countries.

Read a free chapter here

Organizing Political Parties

Political party organizations play large roles in democracies, yet their organizations differ widely, and their statutes change much more frequently than constitutions or electoral laws. How do these differences, and these frequent changes, affect the operation of democracy? Organizing Political Parties provides a comparative study of representation and political participation in contemporary democracies.

Read a free chapter here

Reforming Democracy

Camille Bedock demonstrates how quantitative and qualitative methods can be combined in an empirical research. This study provides both a better empirical understanding of the world of democratic reforms in consolidated democracies, thanks to a new>Read a free chapter here

Party Reform

Anika Gauja analyzes the last ten years of party reform across a handful of established democracies including Australia, the United Kingdom, Canada and Germany to examine what motivates political parties to undertake organizational reforms and how they go about this process.

Read a free chapter here

How Europeans View and Evaluate Democracy

Based on a new>Read a free chapter here

Alan Renwick and Jean-Benoit Pilet provide a rich, detailed historical account and analysis of electoral systems and electoral reforms from a comparative study of 31 European countries. Studying the evolution of electoral systems in European democracies since 1945, they demonstrate that, since the 1990s, there has been a shift towards more personalized electoral systems.

Read a free chapter here

Image credit: Knowledge by Alfons Morales via Unsplash

The post 11 books that deal with contemporary government and comparative political science [Reading List] appeared first on OUPblog.

August 28, 2019

Monthly gleanings for August 2019

Grammar and glamour

As is known, glamour is a spelling variant of glamor even in American English. The question I received was about the connection between glamour and grammar. The word glamour appeared in printed books only in the 18th century. It occurred in Scottish ballads and meant “magic, enchantment.” If Walter Scott had not picked it up and made famous, most of us may never have heard about its existence. (Incidentally, both English and German owe to the Romantics the revival of many obsolete and regional words.) Those who consult old dictionaries may have read that glamour goes back to Glámr, the name of the most famous Icelandic ghost (actually, revenant), described in The Saga of Grettir, or glámr, the Old Icelandic poetic name of the moon, allegedly, the chief producer of illusions. This etymology is wrong. But the true one is a bit puzzling.

The most glamorous field of knowledge, and it is also “fun.” Image by PDPics from Pixabay.

The most glamorous field of knowledge, and it is also “fun.” Image by PDPics from Pixabay.Glamour is undoubtedly an alteration of grammar. Under the term grammar were formerly included all areas of linguistics, and later, “learning” acquired the sense “magic, enchantment.” The word that interests us has been recorded in the forms gramary, gramery; glamery, glamour, and so forth. They reached Scotland from France. The change of gr– to gl– in glamour has never been explained, and this is the puzzling element. Not inconceivably, some words like gleam and glow contributed to the change, but this is guesswork.

This woman is always losing her keys. Photo by Susanne Nilsson. CC by-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

This woman is always losing her keys. Photo by Susanne Nilsson. CC by-SA 2.0 via Flickr.Nowadays, grammar has been all but banished from schools, because, allegedly, it provides no fun, and everything in our educational system is supposed to be fun in its most primitive form. I have taught grammar all my life and can testify to the fact that its enchantment is strong, and, once students realize the magic of cases, moods, tenses, and the rest and begin to notice the use of grammar for the niceties of style, they always ask for more. (Here is one example. Everybody knows that the progressive, or continuous, tense describes an action happening right now, for example, I am standing in front of you, as opposed to I always stand while lecturing. It is rewarding to watch the outburst of curiosity when I ask why then it is possible to say I am always losing my key.) But, of course, to be able to provide a feast, one needs a group of hungry guests.

Three words for “flat”

Those are Engl. flat and German flach and platt. Platt is the easiest to explain. It is a borrowing of a French adjective. Engl. plate, plateau, platypus (the latter a bookish formation from two Greek words), and platitude have this root, widespread in Latin and Greek. Flach is related to Latin plaga “flat surface,” which is akin to neither plague nor plagiarism. Flat is the hardest case. The first root of platypus, mentioned above, reproduces Greek platús ”broad” (compare Plato, whose name meant “broad-shouldered”). As though to tease us, the first consonants in flat ~ platús correspond nicely (Germanic f to non-Germanic p, as in Latin pater versus Engl. father), but where Greek has t, we should expect Engl. th (compare Latin trēs and Engl. three). The numerous attempts to obviate this difficulty have left the riddle unsolved. This is a parade example of how comparative phonetics works. Before the nineteenth century, platt, flat, and flach could have been compared without much trouble, but we avoid the easy solution, and with much wisdom comes much sorrow.

The animal is broad-footed. Etymological musings play no role in its life. Heinrich Harder (1858-1935). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The animal is broad-footed. Etymological musings play no role in its life. Heinrich Harder (1858-1935). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.The origin of the word beaver

There are more than three etymologies of beaver. Some of them are old and fanciful. The one mentioned in the comment was offered by Eric Hamp (Indogermanische Forschungen 77, 1972, p. 164). The reference can be found in my Bibliography of English Etymology. Hamp believed that the reconstructed Germanic root bhebhru– must go back to a verbal root. “Is it too bold to suggest that the beaver was so called because he carried (bhher) wood to make his dam?” This conjecture has not been discussed in later works, and probably for good reason. Even though the beaver indeed carries logs, sometimes from afar, this feature does not look prominent enough for calling the animal “carrier.” (For comparison: no beast of burden has such a name.) Those who have an idea of Hamp’s output know that he has written several thousand notes. Any idea that occurred to him immediately appeared in print. Many of his notes are one paragraph long. If someone happened to point to an inconsistency in his reasoning or to a fact that contradicted his conclusion, he tended to agree with his critic. In my opinion, his etymology of beaver is one of such rather insubstantial ideas.

Sn– and sm-words

German nörgeln “to moan; cavil; grumble, schnarchen “to snore,” and many others like them certainly belong with the sn-words I have discussed in my post. Some of them begin with n, rather than sn– because of s-mobile (about which see the post for last week). German schnurz in mir ist es schnurz, a synonym of mir ist es schnuppe “I cannot care less; it is all the same to me,” is obscure, but both words are probably sound symbolic and may be vaguely connected with the concept of the nose (my subject was snuff). The long nose figures prominently as a derogatory gesture, though some gestures are unpredictable: as Ian Ritchie noted in his comment, the Italians tap the right side of the bridge of one’s nose to indicate cleverness. Also, schnurz rhymes with Furz “a fart.” As usual, when sound symbolism comes in, sound imitation (onomatopoeia) is not far behind.

The long nose, an international gesture of opprobrious contempt. 131 Thumbing Nose, Wat Pho by Anandajoti Bhikkhu. CC-by-2.0 via Flickr.

The long nose, an international gesture of opprobrious contempt. 131 Thumbing Nose, Wat Pho by Anandajoti Bhikkhu. CC-by-2.0 via Flickr.No, I don’t think that smell is from smoke. The words are so different that neither can be the etymon of the other. At best, the same “sound-symbolic idea” unites them, and, if there is any truth in this reconstruction, “smell,” I believe, is primary.

Pig’s eye

I am grateful for both comments. I did know that pig’s eye once meant “ace” in slang, and even toyed with the idea that here we have a bridge to asshole. But of course, there is no way to substantiate such an idea. In a way, I am sorry that I rushed in where serious specialists prefer to tread gingerly. Matthew Goff asked me whether I could say something about pig’s eye in connection with the history of St. Paul, and I used my database for the answer. But my materials payed me false. I now know that the whole of St. Paul was never called Pig’s Eye and that the famous grog shop was not called that either. Mr. Goff thanks me graciously for taking up this subject, but it would have been better if I had not done so. Yet what I said about pig’s eye as a term of endearment and a flower name is correct.

American idioms

I read with great interest the comments on seven-by-nine politicians. Obviously, the phrase seven-by-nine acquired a life of its own. I have also received a letter on let George do it. My view of the origin of such idioms is rather melancholy. The choice of names in them often seems to be arbitrary. Roger, meaning “received,” and Roger in Jolly Roger could probably have been Richard (now Romeo has supplanted Roger!). And think of the countless uses of jack, jenny, and dick (the latter returns us to Richard), not to forget about peter and tom in tomcat and tomgirl.

Mangle

The post for July 24, 2019 was on the history of the word mangle. Some of our readers dealt with the mangle I described when they were young. Their experience is instructive. Justin T. Holt told an amusing story of the mangling of his German etymological dictionary. He owns the 21st edition of Kluge-Seebold. The latest is the 25th, but there is very little difference between the two. The entry on the noun Mangel provides the usual information; the verb mangeln is compared with Latin mancare, as mentioned in my post. The text is the same in all the editions.

Spelling Reform

The work on the Reform continues. Many proposals have been sifted and analyzed, and early in 2020 we may expect a second meeting of the Spelling Congress.

Feature image credit: A pirate flag by Oren neu dag. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Monthly gleanings for August 2019 appeared first on OUPblog.

The problem with Buddhist law in Sri Lanka

Several weeks after the Sri Lanka’s Easter tragedy, in which suicide attackers with links to ISIS killed more than 250 people in a series of coordinated bombings, the country’s president announced that he was releasing a Buddhist monk from prison. The monk, Ven. Galagoda Atte Gnanasara, was the country’s most controversial cleric, having risen to prominence in the aftermath of Sri Lanka’s civil war as the head the Army of Buddhist Power (Bodu Bala Sēnā), an influential Buddhist nationalist group with strongly anti-Muslim views. At the time of his release he had served ten months of a six-year sentence for contempt of court. The announcement of the monk’s pardon instantly made headlines in Sri Lanka and around the world, with many analysts warning that the president’s actions would result in a new phase of pro-Buddhist and anti-Muslim policies on the island.

Yet, as I ask in a recent article, “Buddhist Law Against the State?”: Why was the monk incarcerated in the first place and what, exactly, was the reversal that was occurring? Moreover, what does the broader saga reveal about the interweaving of religion, law and politics in Sri Lanka?

The significance of Gnanasara’s recent exoneration is diminished only by the significance of his original arrest in June 2018, when, for a period of weeks, the island was fixated on the monk’s fate. Gnanasara’s arrest filled newspaper headlines and TV programmes, social media memes and viral videos. From the capital city, Colombo, to the some of the island’s most remote towns, Buddhist monks and lay leaders held rallies and demonstrations, accusing the government of attacking Buddhism and trammelling on the sacred institution of the Buddhist monasticism. At one point, hundreds of saffron-robed monks turned one of Colombo’s busiest intersections into a traffic-stopping protest gathering.

While the spectacle was captivating, even more remarkable were the arguments being made—and not made—about law. As the protests spread around the country, critics focussed less on the conviction itself and more on a rather small legal technicality relating to the procedures of imprisonment: the question of whether the monk would be forced to remove his sacred robes and don the standard prison uniform of a white “jumper” and shorts. From a chorus of voices opposing the court’s judgment, Sri Lankan Buddhist protestors directed their attentions to the robe. So fixated was the public on Gnanasara’s prison clothes that some journalists begin referring to the affair as “Jumper-gate.”

Jumper-gate is one of those rare prism-like events, in which, for a moment, a miscellany of seemingly diffuse and unrelated ideas becomes boldly visible as a single connected unit. In this case, what came strongly into view was the centrality of law in the island’s ongoing debates over the status of Buddhism in a religiously and ethnically diverse country.

Support for Gnanasara merged with demands for law reform. For example, protestors spoke out against what they perceived as injustices built into the island’s long-standing system of legal pluralism, in which separate bodies of property and personal law applied to Muslims, Jaffna Tamils, Kandyan Sinhalese and others—while no concrete legal accommodations seemed to apply to Buddhists, beyond vague constitutional guarantees to give Buddhism the “foremost place.” Protestors also used the idea of a monk being forced to disrobe as evidence of a state-led legal campaign against monastic law, or Vinaya.

Even more striking in the protests was the deep interweaving of race and colonialism with these issues of religion and law. Echoing throughout jumper-gate were accusations that Sri Lankan law was “white-person’s law” (suddangē nitiya) the discriminatory product of Portuguese, Dutch. and British colonists who, as Gnanasara put it “made the law, while holding a bible and giving responsibility to God.” In slogans and speeches dense with multivalent language that mixed together imagery of skin-color, nationality, ethnicity, and language, protestors announced that Sri Lanka’s legal institutions were tainted by bigotry and that those state officials who staffed the courts were, in fact, cabal of deracinated “black-whites” (kalu suddo) who were perpetuating a regime of colonial oppression.

Gnanasara is now out of prison. Nevertheless, those issues and arguments that appeared crystalline during Jumper-gate continue to dominate the country’s religious and political life. Events like Jumper-gate (or Buddhist legal activism) seem to be occurring more often, not less—not just in Sri Lanka but around Southeast Asia. Understanding religion in this region increasingly requires scholars to understand law and history and, perhaps then, begin to understand a healthy way to move forward.

Kelaniya Temple in Colombo, Sri Lanka. April 24, 2019. A Sri Lankan Buddhist monk participates in rites dedicated to the victims of a horrific series of bombings that took place on Easter Day 2019 and killed more than 250 people in the cities of Colombo, Negombo, and Batticaloa. (ISHARA S. KODIKARA/AFP/Getty Images.)The post The problem with Buddhist law in Sri Lanka appeared first on OUPblog.

August 27, 2019

Reviewing for scientific journals: A how to

Scientific journals are complex ecosystems, bringing together different actors in what is loosely akin to an inquisitorial court of law. The chief editor is the judge. She will decide whether a manuscript goes out for review and makes the final decision should the paper be peer reviewed. Members of the editorial board are like council, ensuring crucial checks and balances among authors (the applicant), reviewers (the jury), and even the chief editor. The reviewers play a crucial role in the ecosystem, since they give expert opinion on whether the manuscript should be published, and provide in-depth analysis that both corrects errors and points out communicative and scientific improvements. Without reviewers, quality control would be in the hands of the authors themselves, and readers in deciding whether the paper was worth considering.

Reviewing is a professional act. You have been invited to do so based on your expertise and reputation. Your report must live up to this and therefore you need to approach the review in the right mind set, which is as an expert who will be unbiased, thorough and thoughtful. As the saying goes ‘Review for others as you would have others review for you’. Expect to spend several hours or more on a review.

Understanding a study sufficiently well to comment on it means setting aside blocks of time to read the paper and write your report. Even if reading and writing are done in a single period, I suggest making comments on the manuscript file itself and to add corresponding elaborations on an electronic file (that will become your report). There may be technical parts of the manuscript where you lack expertise: do not attempt to comment on aspects for which you really do not feel qualified.

The editorial office is responsible for the smooth running the journal. Typical decision times vary from days (in cases of desk rejections) to several months. One late review can hold up the whole process. Only accept to review if you can make journal deadlines, and if you are willing to review but may be late, contact the journal office to see if you can negotiate a new deadline.

Authors and editors need to understand and be able to react to the reviewer’s report. This is achieved by writing a structured document. You should start your report by recapping the manuscript, eventually ending in general observations about clarity and interest. This is followed by two main sections: major comments and minor comments. Number each of your comments and include page and line numbers of what exactly you are referring to in the manuscript. Unless the journal specifies otherwise, do not mention whether you recommend publication in the journal. This will go into a separate area reserved for the editors only.

Your report should address the following:

Science. Evaluate the appropriateness of hypotheses, statistical tests, analyses, and the interpretation of results.Veracity of facts, logic and claims. The science should be precise, accurate, complete and verifiable (including cited work).Interest, importance, novelty. What is the advance? How general are the findings?Clarity. Your job is not to correct grammar and spelling! This said, you should comment on the overall communicative quality of the study, and highlight in the minor comments section those key passages that are unclear.Once a review is submitted it cannot be revised. I therefore suggest that before actually submitting, you wait a few days and come back to the document and eventually revise.

Once the review complete, you will be asked to make a recommendation that will – for most journals – only be seen by the editor. Recommendation are typically chosen from: accept, accept pending minor revisions, major revisions, reject. The content of your report to the authors should be consistent with your publication recommendation.

You will have the opportunity to leave confidential comments to the editor. This is the place to give your opinion and, should you recommend revisions, list those that are most important. If you did not have the expertise to review certain sections of the paper, then say it here (not in the report for the authors). As said above, it is important that your review and comments to the editor give the same basic message. Writing a glowing report only to be accompanied by a confidential recommendation to reject without the possibility of resubmission, presents problems for both editors and authors.

One of the most contentious aspects of reviewing a manuscript is deciding whether or not to sign your report. Some do it systematically, others never, and yet others only when their reports are positive. Signing makes reviewers more responsible. But signing carries risks, one being that should the authors be upset by your (well-intentioned) comments, then this may have consequences in the future, particularly if you are a young scientist. Unless you know the risks and want to communicate your identity to the authors (ask yourself honestly why you would want to do this), then I suggest not signing your report.

It’s a good idea to save electronic copies of both the marked manuscript and your review. These will come in handy should, for any reason, the journal misplaces your report, and should you be asked to re-review the manuscript.

The journal may have a space for you to indicate if you would be willing to re-review the manuscript should it be revised. It is good practice to do this, since you are in the best position to judge whether the authors have adequately replied to your comments.

Reviewing is an enriching experience for you and important for promoting the quality of the scientific commons.

Feature Image Credit: Photo by Kaitlyn Baker via Unsplash.

The post Reviewing for scientific journals: A how to appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers