Oxford University Press's Blog, page 179

August 17, 2019

The first gay president?

The topic of the sexuality of President James Buchanan has become a talking point in the media of late due to the presidential campaign of openly gay candidate Mayor Pete Buttigieg of Indiana. In that spirit, we turn to the life of our nation’s only bachelor president and his intimate personal relationship with William Rufus King of Alabama (vice president under President Franklin Pierce). The surprisingly intimate nature of their personal and political relationship reveals how male friendship shaped the politics of America before the Civil War.

James Buchanan, 1834

James Buchanan, 1834 A lifelong bachelor, Buchanan cherished his intimate friendship with William Rufus King, from their days living together while in the Senate to King’s death in 1853. (Smithsonian American Art Museum)

William Rufus DeVane King, ca. 1838

William Rufus DeVane King, ca. 1838 Although virtually unknown today, King was a southern politician and slaveholder who influenced Buchanan immensely. (Dialectic and Philanthropic Societies Foundation, University of North Carolina)

View of East King Street, first block, south side, 1858

View of East King Street, first block, south side, 1858 James Buchanan lived in a house from 1829 to 1849 that was located on the northeastern corner of King Street and Duke Street, in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. (Lancaster History, Lancaster, Pennsylvania)

Ann Coleman

Ann Coleman The fiancée of James Buchanan, Ann Coleman died in 1819. Her untimely death left many questions unanswered. Buchanan, his family members, and his political supporters protected the privacy of his relationship with Coleman during his lifetime and beyond. (Lancaster History, Lancaster, Pennsylvania)

Chestnut Hill

Chestnut Hill The planation of William Rufus King was situated on King’s Bend in Dallas County, Alabama, near Selma. (Alabama Department of History and Archives, Montgomery)

Cornelia Van Ness Roosevelt, 1857

Cornelia Van Ness Roosevelt, 1857 The wife of Congressman John J. Roosevelt of New York, Cornelia Roosevelt was an intimate friend of both Buchanan and King and facilitated their correspondence. (Gilman Collection, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

Anna Payne and Dolley Madison, 1848

Anna Payne and Dolley Madison, 1848 Buchanan called Anna Payne, the closest niece of Dolley Madison, the “Lovely Miss Annie,” and later served as an executor to the estate of Dolley Madison. (Greensboro Historical Museum, Greensboro, NC)

“Union”

“Union” Created in the wake of the Compromise of 1850, the portrait depicts the politicians who helped, whether directly or indirectly, to pass the series of measures that admitted California, resolved the Texas boundary issue, permitted popular sovereignty in the newly acquired territories of the Mexican Cession, and enacted the Fugitive Slave Law. James Buchanan is pictured standing directly in front of William Rufus King in the second row at right. (Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress)

The inauguration of James Buchanan, March 4, 1857

The inauguration of James Buchanan, March 4, 1857 The crowd for Buchanan’s inaugural was the largest assembled theretofore for a presidential inauguration. (Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress)

Cabinet of President James Buchanan, 1859

Cabinet of President James Buchanan, 1859 This early photograph shows President Buchanan standing, surrounded by his Cabinet including Jacob Thompson, Secretary of the Interior; Lewis Cass, Secretary of State; Howell Cobb, Secretary of the Treasury; Jeremiah Black, Attorney General; Horatio King, Postmaster General; John B. Floyd, Secretary of War and Isaac Toucey, Secretary of the Navy. (Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress)

Harriet Lane Johnston

Harriet Lane Johnston Harriet Lane Johnston, ca. 1895. The careful efforts of Johnston, Buchanan’s niece, preserved the personal papers of James Buchanan, as well as her own correspondence, for future researchers. (Lancaster History, Lancaster, Pennsylvania)

Featured Image Credit: “Drawing of President of the United States James Buchanan’s home, ‘Wheatland,’ near Lancaster, Pennsylvania” by Unknown Artist. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons .

The post The first gay president? appeared first on OUPblog.

How women are fighting sexist language in Russia

Coal miners are predominantly male, and kindergarten teachers predominantly female. Professions are gendered, as any Department of Labor survey, anywhere in the world, illustrates. And until the 1980s, the nouns used in English to describe some occupations were also gendered, such as fireman, or stewardess. Feminists in English-speaking countries fought this largely by neutralizing male and female occupational nouns (fireman to firefighter, stewardess to flight attendant), and sometimes by dropping a familiar female noun in favor of a technically male, but standard noun (actress to actor), or ignoring an unfamiliar female noun (senatrix) and simply using the grammatically male one (senator). These techniques successfully eliminated the awkward combination nouns that had been used to describe women who had taken on traditionally male jobs, like woman-doctor, woman-lawyer, and woman-ambassador.

Some Russian feminists have embarked on a quest to address the problem of sexist language by inventing or bringing back female-gendered nouns for professionals in occupations where the norm is male. This language feminization is more challenging than it sounds, however, because the Russian language, unlike contemporary English, is thoroughly gendered. Every noun has a gender (male, female, or neuter), and, as it happens, most occupation nouns are male. There are exceptions— housewife (domokhoziaika) is female, as are nurse (medsestra) and nanny (niania). Sometimes the word “woman” will be affixed to a male-gendered occupational noun, but, as in English, this makes a woman who adopts that male profession sound like an oddity or exception (e.g. woman-doctor or zhenshchina-vrach). The new or resuscitated words gaining in popularity in Russia today change the endings of the male nouns, rendering them grammatically female. Thus doctor (vrach) becomes vrachinia (something like doctoress), lawyer (iurist) becomes lawyeress (iuristka), and professor (professor) would be rendered as professoress (professorka).

To the ears of English-speaking feminists, this might sound like a Great Leap Backward. The ending ess — like the Russian ka — can be read as informal, endearing, or diminutive, a gentle linguistic suggestion that the feminized version of the profession is not quite as serious as the profession signified by the male noun. After all, if a poetess (whether in English or in Russian) were truly talented, she would be called a poet. But, Russian feminists argue, without the female ending, women in certain professions simply disappear. The Russian words for president and mayor, for example, are gendered male, linguistically speaking, which makes people more likely to assume that the occupants of those positions are and should be men. Putting ka at the end of occupation nouns renders women visible — and plausible — in those occupations instead. Moreover, as Olga Lipovskaia, a doyenne of the feminist movement in Saint Petersburg, argues, the only reason that ka or essa sounds diminutive and signifies something less substantial than the noun without that suffix, is that patriarchy has taught us that things identified with women are less valuable than things identified with men.

The use of feminitives (feminitivy), as these nouns are called, is controversial. As with any effort to alter the language, conservatives resist such changes, seeing the new words as awkward-sounding perversions of the mother tongue. Feminitives are keenly debated on social media, as with one Facebook post about a Moscow schoolgirl whose teacher took points off her Russian language test score for using the feminitive for trainee (stazherka) during an oral exam. Proposals have been floated to fine journalists for employing feminitives in their articles, and to delay the introduction of such terms into dictionaries for at least 40 years. Languages are not static, however, and some variations provoke more resistance than others. After all, Russia has adopted a wide range of English-language words that have achieved considerable penetration of the public sphere. Words like update (apdait) and parking (паркинг), not to mention names of stores like Fresh Market and Organik Shop, have been imported wholesale. Russian conservatives use English terms even to condemn western phenomena (such as using GayRopato describe liberal-leaning Europe).

Russian feminists also debate the use of feminitives. To some, affixing the female endings sounds both artificial and blunt, needlessly emphasizing the fact that a woman is performing the job — something which would usually be expressed by mentioning the person’s name (as Russian last names are almost all gendered linguistically). Others believe the emphasis brings an element of fairness to an unfair linguistic situation, making it clear that a person does not have to be male in order to inhabit a range of occupational identities. One young feminist campaigning to recruit women candidates to run in the September 2019 municipal elections in Saint Petersburg uses potential candidates’ affinity for feminitives as a litmus test; she refers to deputesses (deputatki) on her recruitment website, and figures that if a potential candidate sees that and remains interested, it’s a good indicator of her feminist values. By contrast, a feminist sociologist at a well-known Russian university, while generally finding the discussion of feminitives a positive development, noted that she did not want to be called a “professor-ka.” The impact of patriarchy on language is hard to undo.

Changing the language is serious business. It isn’t only feminists who have taken up this discussion; the Russian police have evidently also found feminitivy a matter of significance. On 1 May 2019, six feminist activists with the Saint-Petersburg collective Eve’s Ribs (Rebra Evy) were arrested on their way to a Labor Day demonstration; the police also confiscated their posters — each one featuring a single hand-lettered female-gendered noun describing a profession: doctor, lawyer, author, historian. The activists were released after several hours, but their posters were detained until the activists came to the police station a week later to demand their return. After initially being told that the posters could not be returned on a Saturday (the activists pointed out that since the posters had been taken on a Saturday, surely there was no reason they could not be returned to their rightful owners on a Saturday), they were told that the police needed to hang onto the posters in order to perform an expert analysis on them to see whether they constituted “extremism” or not.

Language affects the way we think about the world, and about our own possibilities. How we shape and change the language matters. Yet, a language’s grammatical peculiarities can also dictate the options available without radically restructuring the common tongue. For example, it would be extremely complicated to revise the Russian language by re-inventing all professional nouns as linguistically neuter, ending in -o or -yo (creating words that would sound something like doctoro and lawyero in English), and doing so would make the gender of the doctor or lawyer in question harder to discern. It is similarly complicated to create job-related nouns in the Russian language that would accurately express the identity of people who identify as non-gender-binary (and, so far, there has been no Russian movement toward doing so). English allows for this easily by using the standard nouns (lawyer, doctor, firefighter, soldier), and occasionally alters terms imported from other languages in order to do so (Latinx being an increasingly familiar example to avoid Latino or Latina). Not so for Russian.

The related problem of gendered pronouns and possessive pronouns has been handled in various ways in English, from alternation (using he in some examples and she in others), to combining the two in speech and writing (When a lawyer goes to court, he or she should look his/her best), and even to pluralization, a choice resisted because of its sheer grammatical defiance of the common use of the plural pronoun (When the president gives a press conference, they stand in the Rose Garden). The he or she technique works in Russian (Kogda chelovek zanimaetsia sportom, on ili ona…), though it is not commonly used, and is complicated by the fact that adjectives and some verb forms are also gendered, introducing a potentially long list of or clauses into a sentence. The very fact, though, that the discussion of feminitives has become widespread in Russia in the past two years suggests that issues of sexism and how to counter it are increasingly permeating the popular consciousness — a welcome development for Russia’s often-marginalized feminist community.

Featured image credit: Choose your Words, by Brett Jordan (@brett_jordan) via unsplash

The post How women are fighting sexist language in Russia appeared first on OUPblog.

August 16, 2019

The future of humanitarian medicine

Humanitarian medicine aims to provide essential relief to those destabilized by crises. This concept, the humanitarian imperative, expands the principles of humanity to include, as a right, the provision of aid to those suffering the consequences of war, natural disaster, epidemic or endemic diseases, or displacement.

Providing assistance to those in crises is a premise as old as human society and is one that is embedded in religious scriptures and social norms. Modern secular humanitarianism, however, originates in the mid-19th century with the first Geneva Convention and the formation of the International Committee Red Cross. Most humanitarian organizations continue to adhere to the original humanitarian principles of impartiality, neutrality, and independence. Expanded over the years, humanitarian providers now have the benefit of established international humanitarian law, which provides a legal framework for negotiation and access.

While over the years there have been steady increases in humanitarian need and presence globally, the previous decade has been marked by unprecedented expansion. As demonstrated in the trends in the financial appeals to meet the global humanitarian needs (an admittedly imperfect approximation to the size of humanitarian needs and operations), in 1992, the first inter-agency humanitarian appeal requested US$2.7 billion to meet the global needs, and by 2007, this figure rose to $5.5 billion. A little more than one decade later, in a 2019 report, the UN required funding reached $24.88 billion, of which only $13.87 billion (56%) were received in 2018. Those covered needs in 41 countries. This explosive increase in global humanitarian needs, with recognition of an equally expanding scope of operations, shows no signs of waning.

The principle cause of the human suffering that leads to a humanitarian response is closely linked to conflict and its resultant displacement, and conflicts today have a changing profile. Today, complex wars, such as the one in Yemen, and protracted conflicts, including those in Syria, Democratic Republic of Congo, and South Sudan have become the unfortunate norm. In its 2018 Global Humanitarian Assistance report, Development Initiatives estimated that in 2017 conflicts and disasters around the world left 201 million people in need of assistance. In addition to this, forced displacement continues to climb and in 2017 reached the highest level since World War II. Over the long term additional factors, such as climate change, are expected to make the situation even worse due to extreme weather, destruction of resources, and famine. The Institute for Environment and Human Security of the United Nations University has forecasted between 25 million and one billion environmental migrants by 2050. Most prognoses foresee 200 million. A displacement at this scale will dwarf anything previously seen.

The human suffering associated with such increases in conflict and displacement is pronounced, and the costs associated with the provision of humanitarian relief are significant. In a 2018 report, the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs estimated the total requirements are approximately $25.2 billion, of which only $15.2 million was received. Significantly, this 40% gap in funding is not equally distributed among countries in need however, as although Iraq received over 90% of the requested $568 million in 2018, Haiti received only 13% of its $250 million request. This suggests that funding to relieve suffering is often tied to political interest and affected by media presence and trade interests, rather than based on need alone.

This changing context has brought both an increase in humanitarian need and an increased risk for those providing such relief. The changing profiles of war have led to erosion of respect for International Humanitarian Law, with increased violations, generally without repercussions. The peril for those practicing humanitarian medicine has never been greater. In 2017, 158 major incidents of violence against humanitarians were documented in 22 countries and affected 313 aid workers.

This is a transformative time both globally and within the humanitarian community. While conflicts continue to claim lives in so many areas in the world, a form of humanitarian action that still adheres to principles of impartiality and independence remains critical. Those committed to practicing humanitarian medicine are upholding the noble principles established over a century and a half ago to help alleviate the suffering in their fellow men. This practice goes beyond simply the clinical and exerts solidarity with those in need and touches on the core of what humanity entails. How both the humanitarian sector and the global community navigates these challenges is crucial.

Featured image credit: Pixabay

The post The future of humanitarian medicine appeared first on OUPblog.

Why American cities remain segregated 50 years after the Fair Housing Act

Fifty years after passage of the Fair Housing Act, large urban areas still remain highly segregated by both race and income. A report last year in the Washington Post concluded that that although the United States is on track to be a minority-majority nation by 2044, most of us have neighbors that are the same race as us.

This homogeneity is deepening in communities across the nation. A study conducted by the University of Illinois at Chicago portrayed the stark income inequality across Chicago neighborhoods, which have also been plagued historically by racial segregation. In 1970, half of Chicago’s census tracts were middle income. Today, that’s true of only 16 percent of tracts in the city. Most of Chicago’s middle-income neighborhoods have become low-income neighborhoods, though the number of high-income neighborhoods has also increased sharply.

The study piqued my interest. I wanted to know what was happening in my hometown of St. Louis. The City of St. Louis, like Chicago, has also suffered a long history of segregation.

The study identified census tracts as middle income if the per-capita income there was between 80 and 120 percent of the metro-wide per-capita income for a given year. I used that methodology to examine St. Louis’s middle-income neighborhoods. What I found closely resembled the neighborhood trajectory in Chicago. From 1970 to 2017, St. Louis lost almost 50 percent of its middle-income neighborhoods. In 1970, St. Louis had 106 census tracts, and 48 of them were middle income; by 2017, that number had decreased to 25. St. Louis had 37 low-income census tracts in 1970. That number grew to 62 by 2017.

Curious whether this trend was consistent, I looked at neighborhoods in nine of the largest U.S. cities (excluding Chicago), and I used census data from the last 50 years. Indeed, those data confirmed a steady decline in middle-income neighborhoods across the cities. Some city neighborhoods are becoming poorer, and others richer, while the number of middle-income neighborhoods is shrinking at an average rate of at least 50 percent every half century. In some cities, like San Diego, the number of middle-income neighborhoods has decreased by 75 percent since 1970. The cities of New York, Los Angeles, Houston, Philadelphia, and Phoenix have all seen a 60 percent decline on average in the number of middle-income neighborhoods. Each has also seen a steep increase in the number of low-income neighborhoods.

Largest US Cities: Income and Census Tract Analysis (1970–2017)

No. of Census TractsCityYearLow IncomeMiddle IncomeHigh IncomeNew York197076099233020171359411292Los Angeles19702554522762017524183272Houston1970130230213201734091142Philadelphia19701431635120172627143Phoenix1970552941012017225124101San Antonio19706312814220171659769San Diego19708635218820179988128Dallas19704360125201718145105San Jose197073165292017957672Source: US Census Data using Social Explorer

The continued prevalence of segregation in US cities and the hollowing out of middle-income neighborhoods are deeply concerning. Research has confirmed that economic context exerts considerable influence on key life outcomes, including graduation rates, incarceration rates, and health. Increasingly, the poor of all races live in resource-deprived communities with weak schools, high crime, and few neighbors possessing the individual social capital to successfully advocate for neighborhood improvement. In a 2014 study, Raj Chetty and colleagues confirmed that income and racial segregation erect significant barriers to social mobility. Chetty’s latest project, Opportunity Insights, predicts the chances of a child’s upward mobility based on the neighborhood where that child grew up. The project’s conclusions are astonishing: If a child grows up in a low-income family and the family moves from a below-average neighborhood to an above-average one in the same metropolitan region, the child’s lifetime earnings would increase by $200,000. Neighborhoods matter.

The negative effects of income and racial segregation have been well documented over the past 50 years and lack of progress is evident. Successfully overhauling the policies implicated in maintaining segregation will require a concerted effort by federal, state, and local governments, as well as national and local advocacy organizations. And politics is more important than policy because, without good politics, there is no room for good policy. We need to both increase access to high-opportunity neighborhoods and redevelop low-income neighborhoods into mixed-race, mixed-income communities. The investments necessary to effect such transitions are broad and deep. They include efforts to build social capital, improve services, and create housing options. Reducing income segregation in low-income communities requires neighborhood improvement strategies that incorporate efforts to attract middle-class residents. But we also must ensure that neighborhood change does not lead to displacement of the poor for the rich. Building mixed-income communities requires careful analysis and planning at the neighborhood level, ongoing interventions in housing markets by government and nonprofit institutions, and the use of such techniques as community land trusts, inclusionary zoning, and permanent affordable housing.

Featured image credit: “White fence and flowers” by Randy Fath. Via Unsplash .

The post Why American cities remain segregated 50 years after the Fair Housing Act appeared first on OUPblog.

August 15, 2019

A 13-year-old scholar shares her research experiences

I noticed that sometimes after using a hand dryer my ears would start ringing. At first I didn’t really pay attention to it, but then I wondered if they were too loud, and that was why my ears were hurting. Also, I noticed that in many cases, when children were in washrooms with hand dryers, the children would be covering their ears and didn’t want to use the hand dryers since they thought they were too loud. Many parents seemed to be acting as if they thought that their child was just overreacting, but I wondered if maybe the dryers actually were too loud for kids’ ears.

To find out, I measured how loud hand dryers were in public washrooms across Alberta, Canada. I measured the loudness from different heights and distances from the dryers, including at the height of children’s ears. Often, I would drive around looking for washrooms with hand dryers, and sometimes, even if I spent a whole day looking, I would find only two. Those times would be very frustrating for me, and I would often wonder if I was making the right choice. I could have been home, biking, playing outside, hanging out with my friends, and having fun, but instead I had spent the whole day driving around looking for and testing hand dryers. My whole family supported me, and encouraged me to keep on going. Without them, I am almost certain that I would have given up, and not been inspired to write a paper. Another big obstacle that I faced was as I was developing a prototype to reduce the noise of hand dryers. The prototype that I developed was a continuation of my previous science fair projects. I made a prototype (a model that reduced the noise of the hand dryer) out of a furnace air filter. I attached it below one of the hand dryers. It was a tube shape and you put your hands under the tube and the tube absorbed the sound. I had built/sewed by hand 12 different prototypes. As you can imagine, that took a very long time, as I had to measure, cut, shape, and stitch; it was hard and tiring. I then tested the prototypes. One of my main objectives for the prototype was that it wouldn’t trigger the motion sensor, since it would be impractical if the prototype triggered the motion sensor and the dryer was running all the time. However, even though I had measured, 11 of the 12 prototypes set off the sensor. I felt terrible. Only one prototype didn’t trigger the motion sensor, and it barely reduced the noise at all. Worst of all, I felt like an absolute failure. I was completely ready to give up. But then, I thought of all the scientists in the world, for instance, Thomas Edison who made 1,000 light bulbs before one of them worked out. He never gave up, so neither did I.

I decided to write a paper since I thought that my results were important. A main thing though was that my sister had written a letter to the editor that got published in Paediatrics & Child Health as well, and it was titled “What kids think about boys getting the HPV vaccine as well as girls,” and it was about her science fair project. I think that my sister really motivated me, because she had written this when she was in grade 5, and she was only 10 years old, and at that time, she was the youngest person to ever get published in a peer-reviewed journal. I thought that that was just incredible (as it is), and I looked up to her so much. So when some of my judges at the city science fair suggested that I write a paper since they thought that my results were good, I started thinking about it seriously, since I saw that my sister was able to do it, so why couldn’t I?

I can still clearly remember the moment, I was grabbing my binders from my locker at school, since it was almost the end of lunch, and then I glanced down at my phone, and I saw that an email was on the screen, and it said that my paper was accepted. I was so shocked, I just sat on the ground, and leaned against my locker, so surprised that my paper was accepted, and I remember thinking all the way through classes that afternoon: I am so excited! My paper is accepted! When I got home and told my family the news, they were all super excited for me.

I hope that kids will try to question things, and if they have a question to go and find the answer, and to prove your answer. I also hope that kids will learn the lesson to never give up, and to keep on going no matter what. Sometimes you feel like quitting, and giving up, but I hope that kids will try not to give up, because for every struggle, there is a triumph, no matter how small. I also hope that kids and girls will not let anyone tell them what they can or can’t do, it is up to themselves to decide those limits, and I hope the limits that they decide for themselves are non-existent.

Image courtesy of author.

The post A 13-year-old scholar shares her research experiences appeared first on OUPblog.

Eighty years of The Wizard of Oz

The summer of 1939 was busy for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, one of Hollywood’s major studios, as it rolled out The Wizard of Oz, a movie musical almost two years in preparation. The budget for production and promotion was almost $3 million, making it MGM’s most expensive effort up to that time. A June radio broadcast introduced the songs and characters to the public. Sheet music was sent to prominent vocalists and bandleaders. Sneak previews, test-market viewings, and other publicity events took place around the country. The official premiere of The Wizard of Oz occurred at Grauman’s Chinese Theatre in Hollywood on August 15, followed two days later by the East Coast premiere at Loewe’s Capitol Theatre. Nationwide release came on August 25.

The rest is history—and what a history!

The Wizard of Oz made indispensable contributions not only to American film and song, but also to our national culture. How often have we heard someone paraphrase what Dorothy utters when stepping out of the tornado-tossed house in the land of Oz, “Toto, I’ve a feeling we’re not in Kansas anymore”? Or quote the Wizard’s attempt to deflect attention from his newly humbugged self: “Pay no attention to that man behind the curtain”? The American fashion designer Marc Jacobs could count on deep cultural memory when releasing a vivid red lipstick called “Surrender Dorothy,” the menacing phrase written in the sky by the Wicked Witch of the West. And, speaking of red: “ruby slippers” can mean only one thing—or actually a few things, since several sets were made for the filming of The Wizard of Oz. One pair now occupies an honored place in the Smithsonian Museum in Washington, D.C., alongside such iconic objects of material history as the fragments of the American flag that inspired the “Star-Spangled Banner.”

The Wizard of Oz literally resonated around the world. Australians refer to themselves as “Ozzies” (a phonetic spelling of “Aussies”). When World War II broke out, the march-like number “We’re Off to See the Wizard,” sung in the film by Dorothy and her companions as they set out on the yellow brick road, became a rallying song for troops from Down Under. No less an authority than Winston Churchill related in his history of the war that Australian soldiers sang it during an important (and victorious) battle with Italian forces in North Africa in January 1941. “This tune always reminds me of those buoyant days,” Churchill wrote.

The Wizard of Oz, a live-action musical in Technicolor (a new phenomenon at the time), was MGM’s response to Disney’s 1937 animated blockbuster Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. Adapting the L. Frank Baum classic into a film that would appeal both to children and adults proved challenging for executive producer Mervyn LeRoy and his team. In the end no fewer than fourteen writers worked on the screenplay. Over its long production time, the film had four different directors. A ten-year-old Shirley Temple was originally slated to play the role of Dorothy, but LeRoy, wanting a more experienced singer, turned to one of MGM’s newest stars, the sixteen-year-old Judy Garland.

ecorded.

ecorded. There were many mishaps or delays along the way to the film’s premiere. The actor scheduled to play the Tin Man, Buddy Ebsen (later famous on the television show “The Beverly Hillbillies”), proved to be severely allergic to silver makeup and body paint; he was replaced by Jack Haley. When filming the explosive exit of the Wicked Witch from the Munchkin village, Margaret Hamilton suffered serious burns and had to miss over a month on the set. The Scarecrow’s makeup created lines in Ray Bolger’s face that he had for the rest of his life.

MGM got one thing right from the beginning—the songwriters for The Wizard of Oz. The associate producer in charge of the musical aspects of the film, Arthur Freed, passed over better known composers like Jerome Kern to choose the team of Harold Arlen (music) and E. Y. (“Yip”) Harburg (lyrics), who had already worked together on a number of Broadway and Hollywood projects. Freed admired their ability to write songs at once appealing and sophisticated, and that is just what Arlen and Harburg did for The Wizard of Oz, creating charming “lemon-drop” numbers (as Arlen called them) like “If I Only Had a Brain” and “Ding, Dong, The Witch is Dead,” as well as the poignant ballad “Over the Rainbow,” which won an Oscar.

“Over the Rainbow” has, of course, had a life of its own beyond The Wizard of Oz. It holds the American Film Institute’s spot for top song and was also voted the greatest song of the twentieth century in a survey conducted in 2000 by the National Endowment for the Arts and the Recording Industry Association of America. It has been recorded thousands of times, by singers and instrumentalists working in many different styles. The version by the Hawaiian pop star Israel Kamakawiwo’ole (best known as “IZ”), has sat at or near the top the Billboard World Songs Charts since its release in 1993.

“Over the Rainbow” became Judy Garland’s theme song, helping seal her reputation as one of the greatest vocalists of her era. Her recordings and concert performances, extending from the original MGM studio take of 1938 to ones made shortly before her death in 1969, chart her difficult journey from child stardom to troubled adulthood. The youthful but nuanced innocence of the film version yields over time to the emotionally wrenching Capitol Records version of 1955. In the 1938 recording, Garland’s voice climbs upward smoothly, cautiously, on a single breath, for the final phrase “why, oh why, can’t I?” In 1955 Garland breaks the line up with several breaths, articulated by sobs or catches in the throat. Same song, same question, same singer—but different expressive worlds.

Eighty years on, watching the film for the first or the hundredth time, or listening to its immortal songs, we still fall under the spell of The Wizard of Oz. The Wizard of Oz ranks among the top ten in the AFI’s lists of the best movies of all time. As we observe the anniversary, it is appropriate to remember that there was no single wizard behind the curtain. We celebrate all the writers, directors, designers, cameramen, musicians, actors, and singers who created the magic that viewers experienced for the first time in the summer of 1939.

Featured image credit: Lobby card from the original 1939 release of The Wizard of Oz featuring Judy Garland, Ray Bolger, Jack Haley and Bert Lahr. MGM, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Eighty years of The Wizard of Oz appeared first on OUPblog.

August 14, 2019

Flatterers and bletherskites

Almost exactly twelve years ago, on August 2, 2006 (see this post), when the world and this blog were much younger, I mentioned some problems pertaining to the etymology of the verb flatter. Since that time, I have written several posts on kl– and sl-words and discussed sound symbolism more than once. There is little doubt that some sounds evoke steady associations in our mind. Such associations are akin to but not identical with those covered by the name of sound imitation (or onomatopoeia), and they are, in a way, mysterious, for why should kl-, for example, make us think of cloying, cleaving, and cluttering, while sl- conjures up an image of things slick, slimy, and sleazy? After all, clever refers to a laudable quality, and there is nothing reprehensible in slumbering or making haste slowly.

Whatever the cause, fl-words often suggest the idea of flickering ~ flittering ~ fluttering (and flowing, but flowing is not among our immediate concerns). The origin of Engl. flatter has bothered etymologists for centuries. The main difficulty consists in the embarrassment of riches strewn before them. Wherever one looks, some verb beginning with fl– offers itself as a sought-after etymon. The idea of borrowing looks especially tempting because flatter appeared in English only in the fourteenth century and ousted its older synonyms. Latin flare “to blow,” flatare “to make big,” and flagitare “to demand, importune,” with French flatter “to flatter,” as well as Icelandic flaðra “to fawn on one” (ð = Engl. th in this) and fletja “to roll (dough),” offer themselves as possible sources of the English word.

It is hard to prove anything in etymology, but two arguments speak decisively again borrowing Engl. flatter from French. First, French flatter would have lost –er in Middle English and become flat (this circumstance was already clear to the OED’s great editor James A. H. Murray).

Two historic events happened on August 2: in 1790, the first census began in the United States, and in 2002, the word flatter was mentioned in this blog for the first time. Get ready for the next census. From the “History of the United States from the earliest discovery of America to the present time,” public domain via Internet Archive Book Images on Flickr.

Two historic events happened on August 2: in 1790, the first census began in the United States, and in 2002, the word flatter was mentioned in this blog for the first time. Get ready for the next census. From the “History of the United States from the earliest discovery of America to the present time,” public domain via Internet Archive Book Images on Flickr.The second argument is a bit more complicated. As is well-known, German names like Sigmund and Siegfried are pronounced with initial z, that is (from the perspective of English), they are Zigmund and Ziegfried. The same holds for any Modern German word beginning with the orthographic s before a vowel: so “so,” sehen “to see,” Sommer “summer,” and the rest. To use technical terms, prevocalic initial s was voiced in German. Dutch went even farther and voiced both s and f before vowels.

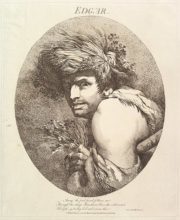

In Middle English, this rule affected only a few dialects, including Kent. Several “Kentisms” (mainly because of Chaucer’s predilection for them) are still with us: for instance, the historical female of fox is vixen (German Füchsin), and a large tub is called vat (German Faß “vessel”). When Edgar as Poor Tom in King Lear (IV, 6) impersonates a rustic, he says zwaggered “swaggered,” zur “sir,” vurther “further,” and volk “folk.” In the Middle English poem Ayenbite of Inwit [“Pricks of Conscience”], Kent, the words ulateri “flattery” and ulatour “flatterer” occur (u = v), but in that text initial French f remained unaffected! Consequently, to that poet ulateri and ulatour were native. In the process of sound change, speakers often distinguish between native and borrowed sounds and treat them differently.

There is another hitch. The origin of the French verb is unknown, and, as I repeat at every opportunity, nothing is less profitable than deriving an etymologically opaque word from another equally opaque one.

Edgar as Poor Tom. “Edgar (Twelve Characters from Shakespeare)” public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Edgar as Poor Tom. “Edgar (Twelve Characters from Shakespeare)” public domain via Wikimedia Commons.The result invariably turns out to be wrong. Discussion of the origin of the French verb would take us too far afield. Several hypotheses have been advanced, none of which is fully convincing. For the same reason, Icelandic flaðra as the etymon of Engl. flatter fades out of the picture: very little is known about its history and even less about its origin (and of course the consonants don’t match: ð versus t).

The Kentish author voiced initial f. We are appreciative of his speech habits. Ayenbite of Inwit, Oxford University Press first edition.

The Kentish author voiced initial f. We are appreciative of his speech habits. Ayenbite of Inwit, Oxford University Press first edition.Thus, English flatter is almost certainly native. Can it go back to Engl. flat? This idea still has some appeal to a few modern researchers, despite the fact that the development from “make flat” to “fawn on” is highly improbable. Although the sense “flatter” is always derivative of some coarser and ruder ones, especially prominent among them are “inflate,” “dupe,” and “lick.” German flattern, a near-homonym of flatter, means “to flutter.” Not improbably, it is a word of the same type as Engl. flatter. According to an extremely old suggestion, a flatterer flaps his wings as a dog wags its tail (hence the sense “flatter”). The suggested origin is thus from “flit about,” to “dance attendance” and (metaphorically) “ingratiate oneself by saying pleasant things.” This rather imperfect etymology of flatter seems to be the best there is at the moment.

Additionally, as though to mock us, another verb (this time certainly from French) synonymous with flatter is blandish, and this fact raises the question whether flatter does not perhaps trace to some word beginning with bl-. In Old Icelandic, the meanings of flaðra and blaðra overlapped. Latin blaterare “to blather” was suggested as the etymon of Engl. flatter centuries ago. Engl. blather ~ blether is from Scandinavian. Blither (which most of us seem to know only from the phrase blithering idiot) is a variant of blether, for in such words vowels and consonants vary freely, and competing dialectal forms substitute easily for one another. (Is Engl. blah, blah, blah from the first syllable of blather?)

Icelandic has the pair flaðra ~ blaðra, and in English, the pair flatter ~ blatter corresponds to it (blatter “to babble”). Could blatter influence the meaning of flatter? We will never know, but, even if it did, this fact will throw no light on the origin of flatter. Also, flatterers are glib and calculating, rather than idle talkers. The noun bladder and the verb blow (“Blow, winds, and crack your cheeks”) are related, and either the sound symbolic or the sound-imitative value of bl– in them is more than probable. To conclude, from the etymological point of view, fl– in flatter does not go back to bl-.

Uriah Heep and his mother, two villains in David Copperfield and two preeminent flatterers in world literature. From David Copperfield, public domain via Flickr.

Uriah Heep and his mother, two villains in David Copperfield and two preeminent flatterers in world literature. From David Copperfield, public domain via Flickr.I can now say something about bletherskite (see the title of this post), with its variants blatherskite, blatherskate, bletheranskite, bletherkumskite, and at least two more. In 1903, an instructive exchange occurred about the word’s origin in Notes and Queries. Since that time, it has been discussed in various blogs, though without reference to NQ. Today, probably no one calls anyone a bletherskite. I even wonder how many younger people understand the word, which designates a blithering fool (not a flattering definition, but there isn’t anything we can do about it).

Although recognized as an Americanism, bletherskite is Scottish. This is a familiar situation: many Americanisms are regional British words brought to the New World, where they flourished, at least for some time; at home they may be known little or not at all (see what is said about the idiom let George do it in the post for last week). The skate ~ skite component is tough. I am aware of at least six attempts to account for it. Some hypotheses are plausible, but in the sources I have consulted, they sound too definitive and produce the false impression that the answer is known. Some time in the future, I may return to this funny word. Today, our main object of enquiry has been the history of sycophants and lickspittles.

Feature image credit: Wings Nature Berries Bird Animal Fluttering, public domain via Max Pixel.

The post Flatterers and bletherskites appeared first on OUPblog.

What went wrong with Poland’s democracy

Poland had been one of the most successful of the European states that embarked upon a democratic transformation after the fall of Communism. After joining the European Union, Poland has been held up as a model of a successful European democracy, with a reasonably consolidated rule-of-law based state and well-protected individual rights. And yet, this all radically changed in 2015 when a populist party PiS (Polish acronym for Law and Justice) won both the presidential and parliamentary elections. After its double victory the party began to dismantle all major checks and balances characteristic of the separation of powers in a democratic state. Poland’s Constitutional Tribunal, its regular courts including the Supreme Court, its National Council of the Judiciary, as well as its electoral commissions, civil service and public media have all been subordinated to the executive – single-handedly controlled by the party’s leader. In the process, political rights such as the freedom of assembly have been restricted, and the party has captured the entire state apparatus. The speed and depth of anti-democratic changes took many observers by surprise.

Poland’s anti-constitutional breakdown triggers three major questions: what exactly has happened, why it has happened, and what are the prospects of a return to liberal democracy? These answers are formulated against the backdrop of current worldwide trends towards populism, authoritarianism, and what is sometimes called “illiberal democracy”. The Polish variant of “illiberal democracy” is an oxymoron. By undermining the separation of powers, the ruling party concentrates all power in one hand, thus rendering any democratic accountability illusory.

Poland’s anti-constitutional, populist backsliding uncovers a broader issue with manifestations in the United States and the Philippines, Italy and Hungary, Turkey and Russia. Each of those countries is different from others but all have some common features: populism everywhere is, in its aspirations if not in practice, anti-pluralist, anti-deliberative, and exclusionary.

The question about whether the European Union (and, to some extent, the Council of Europe) can and ought act in response to non-democratic changes in a member state such as Poland is a deeply contested issue For my part, I do not have any problem in giving an emphatic “yes” answer. The EU must (both for practical and principled reasons) intervene more decisively in the case of Poland’s systemic and ongoing breach of EU values proclaimed in article 2 of the Treaty on European Union. These are foundational values: the rule of law, democracy, and the protection of human rights. Both the union and all member states must observe them, and the breach by Poland especially of the rule of law cannot go unnoticed, and without a sharp legal response. The EU cannot afford having one of its member state violate with impunity its values, voluntarily endorsed by member states.

Despite the grim subject matter, there is nothing inevitable about the decline of Polish democracy. Poland has the strong societal and political resources necessary to arrest and reverse the negative trends, and then unravel all the nefarious institutional changes brought about by PiS rule, difficult though it will be. There is still a vibrant and resilient civil society, there are strong even if rather ephemeral social protest movements, there is an independent body of commercial media, both electronic and print, and there are passionate debates in social media.

In the run-up to the parliamentary elections, which will take place this October (a precise date is not yet determined) these “democratic assets” may turn decisive to help the pro-democratic forces prevent the re-election of PiS. Otherwise, the future is very grim indeed.

Featured Image Credit: March of Freedom, Warsaw, Poland Photo by Kris Cro

The post What went wrong with Poland’s democracy appeared first on OUPblog.

August 10, 2019

History of clashes in and around Jewish synagogues

One Sabbath day in the late-second century CE, a slave and future pope named Callistus (Calixtus I) entered a synagogue and, hoping to die, picked a fight with the Jews. For the opening salvo, he stood and confessed that he was a Christian. A melee ensued. But the Jews only dragged Callistus before Rome’s city prefect Fuscianus and accused him of violating their legal right to congregate. His owner Carpophous appears and exclaims that Callistus is not even a Christian. Sensing a ruse, the Jews press their case and prevail upon Fuscianus. With his plans now spoiled, Callistus is sentenced to hard labor in Sardinia.

It is an odd tale. But parts of it resemble the two most recent attacks against Jews at the Tree of Life synagogue (October 27, 2018) and at the Chabad of Poway synagogue (April 27, 2019): perpetrators entered synagogues on the Sabbath while Jews were gathered, executed their suicide mission, and Christianity was implicated. John 8:44 was evidently a battle cry for the Tree of Life attacker, and Christian theology an inspiration for the Chabad of Poway attacker.

Clashes in and around Jewish synagogues goes back to the earliest days of Christianity when followers of Jesus were trying to define themselves within and eventually apart from Judaism. According to the New Testament, both Jesus and the apostle Paul were often victims. Their fellow Jews drove them out of their synagogues with blows, sometimes on the point of death (Luke 4:16-30; Acts 14:1-19). Many other accounts of synagogue violence have come down to us from antiquity, mostly from Christians sources.

Explaining the violence, however, requires wading through complex theological, political, and rhetorical issues. The emerging picture is much closer to sectarian violence than to Christian-infused white-supremacy. The story about Callistus blends the theological, the political, and the rhetorical with personal animosity. Published in a multi-volume, anti-heretical treatise, it is part of a lager defamation of Callistus’s life by his bitter opponent, an author conventionally known as Hippolytus of Rome, the first antipope. He was out of the Roman church and out to prove that Callistus was a heretic. Behind the story was a theological controversy. Hippolytus was convinced that Callistus’s teachings on the Trinity were too close to strict monotheism, and by extension, too close to a Jewish understanding of God. Besides that, the entire story about Callistus is satirical, bordering on fiction. It is a total smear campaign. Whether Callistus ever set foot in a synagogue is open to question. But describing Callistus as venturing into one, attempting a bogus martyrdom there, then being ensnared in arguments before the city prefect over Jews’ civil rights, does show the synagogue as a unique flashpoint in Jewish and Christian relations.

In the following centuries, as ecclesiastical and imperial authority intertwined, synagogues were occasionally targets. Imperial legislation (397 CE) also sought to protect Jews and their synagogues from acts of violence. The common lack of enforcement, however, meant complex political jockeying, especially at the local level. Bishops were often left with distinct powers. Turmoil could result. In a letter to the emperor Theodosius I in 388 CE, Ambrose, bishop of Milan, excuses Christians at Callinicum (northeastern Syria) for torching a synagogue, reportedly at the instigation of their bishop. Theodosius wanted the arsonists punished and synagogue to be rebuilt at the bishop’s expense. Ambrose disagrees. During the reign of the last pagan emperor Julian “the Apostate”, he argues, many of the Church’s basilicas were burned by Jews, so their synagogue should remain in ashes (Ep. 40). Here, a Jewish synagogue was caught in the crosshairs of regional and imperial politics.

Later in Alexandria, a dispute over a civic institution became a pretext for action. As the story goes, agitations between Jews and Christians over rowdy pantomime shows led the city-prefect Orestes to regulate the theatre’s use, to the chagrin of the Jews. Many Alexandrians were gathered in the theatre for “Orestes’ publication” of the ensuing edict, he yielded to the “Jews accusations” that Hierax, an attendee and admirer of the bishop Cyril, was a spy sent to incite sedition. Reputedly wary of the power of Christian bishops anyway, Orestes had Hierax tortured. Conspiring Jews, the story continues, he then massacred a group of Christians, who in response, charged into the synagogues, rounded up the Jews and, under Cyril’s authority, drove them out of the city. In the fallout, Cyril wrote to the emperor Theodosius II indicting the Jews, through mediation, attempted an ultimately unsuccessful reconciliation with Orestes that eventuated a riot. In this case, power politics and culture wars in Alexandria precipitated the violence.

Verbal pugilism could further raise the potential for conflict. John Chrysostom of Antioch, in eight brutal homilies, repeatedly condemns Jewish synagogues as a “dwelling of demons” and vilifies those who congregate there. Whether his homilies induced his audience to harm their co-residents or ransack synagogues is unclear. (Later, the Nazis weaponized Chrysostom’s homilies). But Chrysostom’s blistering rhetoric reveals that even in fifth-century Antioch, some of his own flock continued to attend synagogues — whether as spectators enticed by the Jews’ festival trumpet blowing (4.7.4), or as participants in Jewish rituals (6.7.3). The blurred lines between Christians and Jews infuriated Chrysostom. Rhetoric is also tricky. Other times, Christian writers were railing against “rhetorical Jews” rather than real ones.

Overall, relations between Jews and Christians were variable. And in antiquity, just as now, either side could enact violence. So it is worthwhile to ask what forces gave rise to confrontations in synagogues by first unpacking the incidents in their own contexts and by probing the often partisan sources that relate them.

Featured Image: Photograph taken by Dr. Avishai Teicher.

The post History of clashes in and around Jewish synagogues appeared first on OUPblog.

Progressive black radio weighs in on Trump’s base

“Tom and Sybil, you guys lifted us up mightily for so many years,” said President Barack Obama to the Tom Joyner Morning Show anchors on 2 November, 2016. “I could not be more grateful.”

Economic insecurity or racism? Immediately following Donald Trump’s shocking 2016 electoral-college presidential win, commentators rushed to explain the results by focusing on white voters claiming that the economic recovery from the 2008 Great Recession had “left them behind.” Others argued strongly that Trump’s explicit racism and xenophobia had drawn in whites anxious about losing their racial and imperial privilege. But those arguments received little attention.

Until. Until Trump labelled the neo-Nazis marching on Charlottesville in August 2017 “good people.” Until he put thousands of refugee children in cages. Until his racist, xenophobic lies, week after week, month after month, piled Pelion on Ossa, the structure finally tumbling down when he recently accused four congresswomen of color of being traitors “incapable of loving our country,” and called for the women, three of the four born in the United States, and all of them of course American citizens, to “go home!”

Meanwhile, exhaustive post-election studies proved repeatedly that racism/xenophobia and fear of losing white privilege, not economic insecurity, were most Trump voters’ key motivations.

But an overlooked American media giant had never been fooled by the economic insecurity claim, and called out Trump’s racism, xenophobia, and misogyny day after day, both during the campaign and after the election. The Tom Joyner Morning Show, a syndicated morning drive-time music/politics/humor show whose eight-million strong audience is largely middle-aged, working to middle-class African Americans, has increasingly articulated explicitly progressive politics over its quarter-century history.

From its inception, the show and its audience—who called and later texted in their questions, opinions and magnificent wit—mixed into their deeply satisfying soul music playlist and comic hijinks the articulation of an organic vision of broad civil rights for all US minorities, women’s and LBGTQ rights, union rights and economic populism, antiwar and anti-imperial perspectives, and environmentalism. And from at least 2000 on, the program was deeply electorally engaged, working for and hosting Democratic politicians and movement activists. That engagement peaked in the 2007-08 electoral cycle, when they went all-in for Barack Obama, teaming up with the NAACP and the Teamsters Union, to register hundreds of thousands of black voters, urge them to the polls, and protect the franchise from Republican voter suppression with teams of on-call attorneys. They were rewarded with unprecedented access to the campaign, and multiple on-air interviews with Barack and Michelle Obama themselves.

Despite this show’s more than 14 years of hugely effective political engagement, as well as its music, humor, and audience interactions, mainstream media has paid extraordinary little attention to this black media giant, its blistering political humor, and its activist and philanthropic work. This failure of attention is yet another example of media scholars Robert M. Entman and Andrew Rojecki’s “saints or sinners syndrome” (The Black Image in the White Mind: Media and Race in America): media’s near-exclusive focus on only celebrity/wealthy or impoverished/criminal African Americans, “invisibilizing” the broad adult working- and middle class that is the bulk of the black American population. And the bedrock of this program’s audience.

The show was no less engaged in the 2016 election, expressing withering contempt for Trump in straight news reporting and wild comedy. “Billionaire Bigot Bozo” and “Pumpkin-Colored Race-Baiter” are only two of their many dozens of scathing Trump epithets. But they were also highly aware, unlike most US media, that Hillary Clinton’s campaign’s failure to invest in ads in black media and get out the vote efforts in African American-majority precincts, combined with Republican voter suppression, could curb precisely the Democratic-voting margin that had ensured President Obama’s two electoral triumphs. And despite their explicit on-air warnings to Clinton, that is precisely what happened.

Show comic Chris Paul’s day-after heartbroken doggerel poem pointed to the racism—“He lit the fire of the angry white male”—misogyny—“What do we say to our daughters about electing a man who bragged about assault”–and xenophobia—“What do our Latino neighbors make of…a new America that doesn’t include them?”—that had animated Trump voters.

Since the election, Tom Joyner Morning Show has maintained its activist stance, and was deeply engaged in the 2018 midterm Democratic electoral wins, most particularly Doug Jones’ Alabama senatorial victory—fueled by black voters, who turned out in higher numbers than they had for Obama’s two wins, over the racist, hard-right evangelical, alleged pedophile Roy Moore. Huggy Lowdown, a show comic, exclaimed to anchor Sybil Wilkes: “Kinfolk came to vote like it was a black funeral!” [all lost in laughter]

As an audience member texted in: “It’s time for America to shut up and listen to the sistahs!”

It is indeed—long past time. Only transcending “saints or sinners” to acknowledge all minority Americans’ experiences and apprehensions will enable us to unite the majority of the country and take out Trumpism.

Featured image credit: microphone by lincerta via Pixabay

The post Progressive black radio weighs in on Trump’s base appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers