Oxford University Press's Blog, page 182

July 22, 2019

The surviving letters of Jane Austen

Famed English novelist Jane Austen had an extensive, intimate correspondence with her older sister Cassandra throughout her life, writing thousands of letters before her untimely death at the age of 41 in July 1817. However, only 161 have survived to this day. Cassandra purged the letters in the 1840s, destroying a majority and censoring those that remained of any salacious gossip in a bid to protect Jane’s reputation.

Electronic Enlightenment has collected the Austen letters that remain, where, despite Cassandra’s best efforts, some of Jane’s tantalizing observations can still be glimpsed. Below are a few excerpts (copied verbatim with their influx of dashes and semicolons):

You scold me so much in the nice long letter which I have this moment received from you, that I am almost afraid to tell you how my Irish friend and I behaved. Imagine to yourself everything most profligate and shocking in the way of dancing and sitting down together. I can expose myself, however, only once more, because he leaves the country soon after next Friday, on which day we are to have a dance at Ashe after all.

– Jane Austen to her sister Cassandra, 9 January 1796

After they left us, I went with my Mother to help look at some houses in New King Street, towards which she felt some kind of inclination — but their size has now satisfied her ; — they were smaller than I expected to find them. One in particular out of the two, was quite monstrously little ; — the best of the sittingrooms not so large as the little parlour at Steventon, and the second room in every floor about capacious enough to admit a very small single bed. — We are to have a tiny party here tonight ; I hate tiny parties — they force one into constant exertion.

– Jane to Cassandra, 21 May 1801

A few days ago I had a letter from Miss Irvine, and as I was in her debt, you will guess it to be a remonstrance, not a very severe one, however ; the first page is in her usual retrospective, jealous, inconsistent style, but the remainder is chatty and harmless. She supposes my silence may have proceeded from resentment of her not having written to inquire particularly after my hooping cough, &c. She is a funny one.

– Jane to Cassandra, 7 January 1807

I continue to like our old Cook quite as well as ever — & but that I am afraid to write in her praise, I could say that she seems just the servant for us. — Her Cookery is at least tolerable ; — her pastry is the only deficiency.

– Jane to Cassandra, 31 May 1811

I am amused by the present style of female dress ; the coloured petticoats with braces over the white Spencers and enormous Bonnets upon the full stretch, are quite entertaining. It seems to me a more marked change than one has lately seen. — Long sleeves appear universal, even as Dress, the Waists short, and as far as I have been able to judge, the Bosom covered. — I was at a little party last night at Mrs Latouche’s, where dress is a good deal attended to, and these are my observations from it. — Petticoats short, and generally, tho’ not always, flounced. — The broad-straps belonging to the Gown or Boddice, which cross the front of the Waist, over white, have a very pretty effect I think.

– Jane to her sister-in-law Martha, 2 September 1814

In addition to Jane’s regular letters, a few key outliers exist, such as a poem to her brother upon the birth of his son and a coded message to her 8-year-old niece:

My dearest Frank, I wish you joy

Of Mary’s safety with a Boy,

Whose birth has given little pain

Compared with that of Mary Jane. —

May he a growing Blessing prove,

And well deserve his Parents’ Love ! —

Endow’d with Art’s & Nature’s Good,

Thy name possessing with thy Blood,

In him, in all his ways, may we

Another Francis William see ! —

– Jane to her brother Francis, 26 July 1809

Ym raed Yssac

I hsiw uoy a yppah wen raey. Ruoy xis snisuoc emac ereh yadretsey, dna dah hcae a eceip fo ekac. Siht si elttil Yssac’s yadhtrib, dna ehs si eerht sraey dlo. Knarf sah nugeb gninrael Nital. Ew deef eht Nibor yreve gninrom. — Yllas netfo seriuqne retfa uoy. Yllas Mahneb sah tog a wen neerg nwog. Teirrah Thgink semoc yreve yad ot daer ot Tnua Ardnassac. — Doog eyb ym raed Yssac. — Tnua Ardnassac sdnes reh tseb evol, dna os ew od lla.

[My dear CassyI wish you a happy new year. Your six cousins came here yesterday, and had each a piece of cake. This is little Cassy’s birthday, and she is three years old. Frank has begun learning Latin. We feed the Robin every morning. — Sally often enquires after you. Sally Benham has got a new green gown. Harriet Knight comes every day to read to Aunt Cassandra. — Good bye my dear Cassy. — Aunt Cassandra sends her best love, and so we do all.]

– Jane to her niece Cassandra Esten Austen, 8 January 1817

Though these letters are only a small fraction of her total epistolary output, Jane’s character and wit still bleed through. They are still a valuable look at the daily life of one of the great English writers, so one can imagine if we had access to them all?

Featured image credit: Debby Hudson, CC0 via unsplash.

The post The surviving letters of Jane Austen appeared first on OUPblog.

Summer music camps aren’t just for kids anymore

Kids aren’t the only ones about to head off to sleep-away summer camps. Scores of adults are packing bags—and musical instruments—to spend a week at summer programs that let them experience “camp food, lumpy beds, and music from 9:00 a.m. to 9:30 p.m.—what could be better? I return to work energized, inspired, and at peace. The perfect vacation,” said Dr. Karlotta Davis, a Denver physician, avocational flutist and regular summertime music camper.

She and other avocational musicians say there is something magical about getting away from everyday stress to focus on music for a glorious week, instead of having to shoehorn music-making into spare moments in their regular hectic schedules. Once they start, many go back year after year. “I’ve been attending SCOR [String Camps on the Road] for almost twenty years,” noted Peg Beyer, a retired New York banker. “It was the first summer music program I attended after picking the cello back up (after a ten-year hiatus). The friendly environment helped in building confidence that allowed for taking risks and growth.” She has graduated now to other summer programs that have auditions and play more advanced music, but she still fits in a String Camps on the Road camp.

Summer programs help in overcoming a lack of musical self-confidence that can discourage adults from getting back into the music-making they loved as youngsters but put on hold to start careers and families. A nurturing summer program can provide enough of a boost to keep them making music the rest of the year—in part to be ready for the next summer’s music camp.

“I see it as annual maintenance for my playing,” said Washington economist and violinist David Brown. He spends a week each summer at the Bennington Chamber Music Conference in Vermont. “I get to play more there than at home, both in terms of personal practice and playing with others.” The program’s coaches—professional musicians—help “keep bad habits from setting in.” Another benefit of returning to a music camp each year: “It’s a reunion with people I have really enjoyed getting to know.” That’s why Elena Rahona, a New York environmental researcher and violinist, attends the UK’s East London Late Starters Orchestra program each summer: “I relish the lovely bubble of it all, the good friends, the music … a fantasy world where there is always someone eager to jump in for some pick-up quartets.”

Image credit: Professional violist Korine Fujiwara coaches clarinetist Georgiana McReynolds and violist Maggie Speier in Mozart’s Clarinet quintet at the Bennington Chamber Music Conference summer program. Photo by Amy Nathan. Used with permission.

Image credit: Professional violist Korine Fujiwara coaches clarinetist Georgiana McReynolds and violist Maggie Speier in Mozart’s Clarinet quintet at the Bennington Chamber Music Conference summer program. Photo by Amy Nathan. Used with permission.Music-camp friendships made the Baltimore Symphony’s last-minute cancellation of its Baltimore Symphony Orchestra Academy Week summer program this year especially painful. “It’s not so much putting a hole in the summer as it is the dozens of friendships I’ve built up there all those years that I won’t have the opportunity to be with this year,” said Beyer, a nine-year veteran of this program for amateur musicians, canceled without warning in late May along with the orchestra’s other summer fare, as part of its retrenchment due to financial problems. Summer program friendships include the coaches—in this case, Baltimore Symphony musicians, whose jobs may now be at risk, a concern for Beyer and others. She and other regular Academy Week participants are trying to set up informal musical get-togethers this summer and hire Baltimore Symphony musicians as coaches. Other disappointed participants have been scrambling to locate spots in other programs.

Finding summer programs requires online searching and word-of-mouth recommendations, as there is no comprehensive list of programs, although these sixty programs can serve as a “starter list” for a would-be camper’s further research. Music camps for adults cover a variety of genres—classical, jazz, rock, folk, country, choral music—and a range of skill levels, from programs for newbies to ones for advanced players. Tuition can be high and taking off a week from work or family responsibilities may not always be possible, leading some avocational musicians to put together their own summer music programs closer to home, performing with summer bands and choruses, or taking workshops at a local music school.

Statistician Liz Sogge is going that route this summer, playing violin in a coached chamber music program at Baltimore’s Peabody Preparatory. Atlanta nursing professor Ann Rogers is keeping up with her flute lessons and hoping that her schedule next year will let her go to music camp again. “My advice for those who have never attended a summer program: Go for it,” she said. “It’s great to hang out with other adults who enjoy music. Don’t worry about your skills. A good program will be supportive whatever your level.”

Featured image credit: Trees. Photo by Amy Nathan. Used with permission.

The post Summer music camps aren’t just for kids anymore appeared first on OUPblog.

July 21, 2019

Boris Artzybasheff, C. S. Lewis, and lost art

In September 1947 the paths of two great minds and almost exact contemporaries crossed when Boris Artzybasheff painted a portrait of C. S. Lewis for the cover of Time magazine. Lewis was by then an established name in Britain and a rising star in America, while the distinctive style (if not name) of Russian-born New Yorker Artzybasheff was familiar to millions on account of the hundreds of illustrations he did for popular books and magazines. Both men were shaped deeply by the wars they experienced as teenagers, by the growing prevalence of machines in society, and by a faith in their own singular points of view. Both wrote children’s books and had a keen interest in myth and fantasy, and both disparaged commercialization of the arts while benefitting from it. In the decades since their deaths, however, it was Lewis whose name remained known to the public, while Artzybasheff is remembered by few besides art specialists. The reasons for this are complex. But it occurred to me recently—having searched for and failed to locate Artzybasheff’s original portrait of Lewis—that one prosaic differential is the degree to which their respective estates preserved and promulgated their legacies.

Lewis was a scholar of literature at Oxford and Cambridge Universities and an adult convert to Christianity. A series of broadcasts he did during the Second World War explaining the tenets of Christianity, along with a book called The Screwtape Letters, made his a household name. Lewis then wrote The Chronicles of Narnia in the quiet of the post-war years. After his death in 1963, an American fan named Walter Hooper took it upon himself to organize, manage and promote Lewis’s substantial literary estate. His two stepsons did their best to maximize the estate’s financial potential. The Chronicles of Narnia reached ever new audiences through an expanding educational system and with each new film and television rendition, while many of his other books remained steady sellers, especially in America. Such success requires people who are willing and capable of managing the myriad of logistics that accompany a growing, international, multi-media brand—and Lewis certainly had that.

Artzybasheff, by contrast, didn’t have children or other heirs who were willing to invest in his legacy, so his striking anthropomorphisms of man and machine (a favorite subject) haven’t been utilized by some modern company’s advertising team or made into T-shirts. His was an immigrant’s story. He was born in Kharkov, Ukraine, then part of Russia, and emigrated to New York in 1919, spending his twentieth birthday on Ellis Island. The first book he illustrated, Verotchka’s Tales, appeared in 1922 and many more followed through the 20s and 30s, including several that he both wrote and illustrated such as Seven Simeons: A Russian Tale (1937), winner of the New York Herald Tribune prize. During the war he began doing covers for Time—215 in all between 1941 and 1965—while the State Department employed him for cartography projects and a United Nations logo. Martin Salisbury described Artzybasheff’s art like this: “Words such as ‘idiosyncratic’ or ‘eccentric’ do not begin to do justice to the extraordinary creations of Boris Artzybasheff. His was an art that defies categorization—one of elaborate compositions and constructions, rendered all the more surreal and disturbing by his intensely detailed techniques.”

His incredible art retains its power today. But Artzybasheff had no fans come forward after his death in 1965 to collect and preserve his work. Instead much appears to have been lost; the largest collection, at Syracuse University, contains few originals. Artzybasheff, also unlike Lewis, did not have the steady support of a university but painted and drew for businesses who could issue him a check. Perhaps this, too, meant there were fewer natural allies or colleagues to keep his art before the public and his memory alive.

Lewis and Artzybasheff crossed paths one more time, when the latter included creatures from Lewis’s Out of the Silent Planet, the Hrossa, in a drawing of Martians portrayed in literature through the centuries, for Life magazine in 1956. It may be that when Artzybasheff was asked to paint a portrait of Lewis for Time, he discovered the author’s science fiction trilogy and a kindred imagination. Lewis, for his part, was lucky to have been in the hands of such an artist.

Featured Image: Vanka’s Birthday, llustration by Boris Artzybasheff from Verotchka’s Tales. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Boris Artzybasheff, C. S. Lewis, and lost art appeared first on OUPblog.

July 20, 2019

How will wars be fought in the future?

Russia’s actions in Ukraine, the rise (and apparent fall) of ISIL in Syria and northern Iraq, and Chinese activity in the South China Sea have prompted renewed debate about the character of war and conflict, and whether it is undergoing a fundamental shift. Such assertions about the apparent transformation of conflict are not new; one of the enduring features of conflict over the centuries has been how much it changes.

From the longbows of Agincourt, to the mechanised slaughter of the First World War and the digital warfare of the 21st century, the ingenuity of the human race continues to impact on the character of conflict and how wars are fought. As states gain military advantage, adversaries look for ways to counter it, driving change and innovation. In order to be able to plan and prepare for future war, states must regularly monitor how other states, either allies or adversaries, wield military force.

The increasing complexity of the global security environment in the 21st century makes it difficult for states to plan for future wars. The sheer pace of change, accelerated by changes in technology and communications, as well as the growing interconnectedness of societies, has added to the complexity of the international environment. The ability of actors and individuals to produce their own digital content and communicate it across state boundaries instantly is unprecedented.

The cognitive realm has become a battlespace, where victory is won by the domination of ideas and narratives, rather than physical territory. Although information warfare is not new, the manipulation of interconnected, information-rich environments means that it is becoming increasingly difficult to distinguish between friend and foe, and the traditional binary distinction between war and peace is often unclear. This raises questions about what constitutes the use of force in the 21st century and the continuing effectiveness of traditional armed forces.

As the rate of technological change accelerates and the landscape dominated by technologies that are potentially disruptive, many states envision future conflicts that involve remote and autonomous systems. However, depending on technology will increase vulnerabilities that adversaries will seek to exploit. In recent decades many militaries, particularly in the West, have become increasingly dependent on GPS for navigation, positioning of precision munitions and timing, to the extent that it is now recognised as a single point of failure by the US Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). Rather than seeking to compete with multiple technologies, adversaries focus on disabling modern command, communications, and navigation systems, which would have an immediate impact on a state’s military capabilities. An over-reliance on technological solutions could also undermine the ability of actors to adapt and think creatively. Western states run the risk of being out-thought by their opponents, who have been conducting in-depth assessments of the Western way of war for decades.

For states such as Russia and China, the lessons from Western interventions in the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (1999), Iraq (2003) and Libya (2011) have been instructive, shaping their own perceptions of the changing character of conflict and the implications for their own militaries. In contrast to the focus of Western states on discretionary operations centred on counterinsurgency, stabilisation, and humanitarian intervention, conventional military force has remained a central focus of these states. For example, there is a long tradition of rigorous military strategic debate in Russia, as well as an emphasis on the systematic, scientific study of the theoretical foundations of war and conflict. Forecasting the future character of war is an enduring concern in the writings of serving or retired military officers in open publications intended for an internal Russian audience. Many such writings focus on the characteristics of 21st century conflict and the security threats facing Russia, particularly those that come from the US.

Thus, in attempting to predict the future character of war and conflict, it is vital to understand that our adversaries are going through a similar process of observation and assessment. The lessons learnt by others from your own experience may not be the lessons we consider to be the most important, or are comfortable with, but if we fail to heed them we may find ourselves unable to effectively counter adversaries.

The experiences of individual states foster different visions of future conflict and how states envisage military force being used, either by themselves or potential adversaries. This diversity stresses the fundamental difficulties of predicting the precise nature of the next war or future conflict. While states take different routes in attempting to manage this inherent unpredictability, they all seek to conduct a thorough analysis of conflicts both past and present to understand and predict how countries will fight wars in the future.

Featured Image Credit: “Line of Soldiers Walkin” by Pixabay. CC0 public domain via Pexels.

The post How will wars be fought in the future? appeared first on OUPblog.

July 19, 2019

From the farm to rocket road: one engineer’s story

Retired engineer Henry Pohl can vividly recall his first encounter with a rocket. During the early 1950s, the Army drafted him and shipped him from Texas to the Redstone Arsenal in Huntsville, Alabama. “That dadgum thing looked pretty simple,” he says of the rocket engine. It didn’t look much bigger than the tractor engine back home. Pohl watched his army colleagues prepare a static test—the rocket engine would be held in place. “All at once that thing lit off. I had never seen power like that,” he recalls. “That beautiful white flame came out of the engine that looked like a gigantic cutting torch.” What amazed Pohl was that something the size of his tractor engine—which was impressive already—could weigh less but generate hundreds of times more power. He was hooked. Soon enough, he’d be running that test facility and helping Wernher von Braun, the German-turned-American rocket scientist, build rockets large enough to carry humans into the cosmos.

Prior to his rapture with rocketry, Pohl had only wanted to farm. Raised in rural south Texas, he remembers fetching water from the well, marking the mornings with chores, and navigating cloudy moonless nights, before electric power, black like a deep cave. He once found his way home by feeling the ruts in the road with his feet and hands. But Pohl was always fascinated with machines. He was the boy who went to town to fetch the family’s first gas-powered tractor and ride it home, holding the vibrating steel wheel until it bruised his hands.

Pohl recalls the first time he saw von Braun speak. At a conference in the late 1950s, von Braun lectured on one of his passions: a permanent, rotating space station. “When he got through,” Pohl says, “he wanted to know if there were any questions, and I said ‘Yes, you can’t balance it.’” Pohl had mounted his share of tractor and truck tires on the farm, and he knew it would be impossible to stabilize something with people and equipment moving around within.

“Ah!” von Braun said. He rifled through his briefcase, found an extra slide. He explained to Pohl that expertly placed water tanks would maintain the station’s balance. von Braun and his fellow imported German scientists would come to greatly value Pohl’s questioning and mental fearlessness.

One night in September of 1957, one of Pohl’s German bosses strode into his office looking beaten and almost physically ill. Pohl asked him what was wrong, and his boss said that the Russians were going to launch a major rocket and put something into an orbit around Earth. Pohl had never seen the man look so depressed. “Henry,” his boss said, “it’s going to be very bad for the United States.” Days later, the launch of Sputnik I created something akin to cultural panic. A space race began, with the Soviet Union having bolted at full sprint and America on its heels, blinking at the sound of the starter’s gun. Soon, Congress created NASA, and the agency quickly absorbed the army’s Redstone Arsenal, along with Von Braun and Pohl.

Henry Pohl in a 1959 NASA film detailing a small-scale working model of a Saturn rocket. (Still taken from footage provided by Henry Pohl from the NASA film The Saturn Vehicle Scale Model.)

Henry Pohl in a 1959 NASA film detailing a small-scale working model of a Saturn rocket. (Still taken from footage provided by Henry Pohl from the NASA film The Saturn Vehicle Scale Model.)When NASA built a new Manned Spaceflight Center near Houston, Pohl took a new post there. His German colleagues were sorry to see him leave, but he wanted to be closer to his family. He took everything he had learned about the very large rocket engines in Huntsville and applied them to the much smaller rocket thrusters that would nudge space capsules this way and that for more delicate maneuvers. He joined Apollo, the all-consuming sprint to land men on the Moon and return them, alive and unharmed, to Earth.

“That’s all I thought about, day and night. That’s all I dreamed about, day and night. We had so many problems, and you never had enough time.” He said a lot of it was fun, but it took too much of a toll. He had hoped for weekends at the Pohl family farm, working cattle, but it never materialized. With his Houston desk disappearing in stacks of worries, Pohl tracked insolvent problems, arguments, and mysteries from multiple NASA centers to scores of contractors across the nation. He could not afford to ignore a single loose thread.

After Apollo, Pohl worked on the Space Shuttle’s engines, and eventually rose to oversee all of Engineering at the Johnson Space Center. Today he lives in rural south Texas, within view of the original family homestead. Beside the dirt road leading to the family ranch, a little “welcome to paradise” sign perches on a barbed-wire fence. Pohl helps keep track of many hundred head of cattle, but he will gladly sit down and share his stories.

Henry Pohl’s wall of mementos, featuring Apollo-era retro control thrusters, from his work in Houston, and scale models of Saturn rocket engines, from his work in Huntsville.

Henry Pohl’s wall of mementos, featuring Apollo-era retro control thrusters, from his work in Houston, and scale models of Saturn rocket engines, from his work in Huntsville.Henry especially enjoys talking about his childhood, from thawing the bath water on a winter’s morning to building a barn by steady hand. While he is proud of his rocketry career, he returns again and again to the near misses, the details that almost escaped his notice. Tiny cracks in fuel tanks and misread scans of spacecraft seams trouble him still.

Featured image by NASA, The Manned Spacecraft Center’s Mission Control, Houston, 1965.

The post From the farm to rocket road: one engineer’s story appeared first on OUPblog.

The paradox of alliances– strong economics but fragile politics

It’s not just in international relations that identity politics can sabotage opportunities to cooperate for mutual economic benefit. Much the same can happen to cooperation between firms. Organizations form alliances because they make strategic and economic sense. Yet often the potential for collaboration is undermined by the distrust and fears of the partners.

The long-standing alliance between Renault and Nissan Motors has been in the news for just this reason. Their collaboration began in 1999 when Renault sought a partner to help it achieve economies of scale and to sell cars in more countries. It agreed to a complex cooperative relationship with struggling Nissan, then facing a shrinking market share and a debt load that was leading the company toward bankruptcy. Under the leadership of Carlos Ghosn, the new alliance management turned Nissan around through a combination of investment and streamlining production and purchasing, while Renault gained first-rate engineering and access to new markets. In only three years Nissan had been rescued, and the combined companies were among the top five world automakers. By 2016, another struggling Japanese manufacturer, Mitsubishi, joined the alliance which in 2017 sold more cars than any other manufacturer.

The Renault-Nissan alliance seemed to have worked. A variety of joint activities, shared production, and technology development projects led to improved efficiency for all parties involved. At the same time, the partners retained their separate identities with customers and employees, building confidence and loyalty.

Yet things have gone badly wrong. Ghosn, by then chief executive of all three entities, was arrested by the Japanese authorities in November 2018 on charges of financial misconduct at Nissan including understating his pay and perks. This exposed a simmering rivalry between the French and Japanese nationalists in each camp of the alliance. While speculation continues as to the underlying reasons for this hostile move by the Japanese, it seems that a major factor was a growing sense of grievance that Renault dominated the alliance through its 43.4% ownership. Although Nissan accounted for the largest share of the alliance’s sales and profits, it owned only 15% of Renault in the form of non-voting shares. Tension increased when the French government decided in 2015 to boost its stake in Renault to preserve its double-voting rights as a shareholder. The French also began to push for a complete merger of the two firms. Nissan’s reservations stopped an announced merger between Renault and Fiat Chrysler, while Renault threatened to derail the recent overhaul of Nissan’s corporate governance structure. Despite the agreement reached on granting Nissan board committee seats to Renault’s representatives, whether their lucrative collaboration can be repaired remains to be seen. Some of the alliance’s joint business functions set up during the Ghosn era to oversee cooperation are reportedly being axed amid the increasingly strained relationship between the companies.

It is not so unusual for an economically successful alliance to fall prey to mistrust between the partners. The Renault-Nissan alliance started well with a strong personal chemistry between senior partner executives and engineers fostered by joint activities undertaken even before the companies signed a formal agreement. This foundation was built on cooperation in many joint project teams which particularly contributed to Nissan’s turnaround.

Over time, though, the alliance’s unbalanced ownership structure failed to reflect Nissan’s success. Joint activities such as the launch of a low-cost car in India in 2014 were hampered by failing cooperation. Ghosn’s centralized leadership eroded the separate identities of the firms and supplanted the need for actual cooperation between firms. The prospect of a full merger driven by French voting interests threatened the carefully maintained cultural identity of Nissan as a leading Japanese industrial firm. By the summer of 2019, it is clear that little trust remains among the partners, even as all sides proclaim their commitment to continuing cooperation.

What can we take away from this story? Alliances can be very successful – if led by the right people, designed around a sound cooperative strategy, and supported for the long run by employees. Yet conflicts often arise between partners, and studies suggest that around 50 per cent of alliances are terminated by the time they reach their fifth anniversary. Even with a good economic and strategic fit, personal and political tensions can develop between partners, reflecting differences in cultural identity and expectations. An understanding of human perception and behavior is essential to enable the economic payoffs from alliances to be achieved and maintained. Two insights are particularly important. First, while cooperation provides mutual gains that partner firms cannot generate on their own, it is important for the partners to develop and maintain a perception of mutual benefit among their staff. Second, trustbetween firms is essential and requires a lot of psychological investment to overcome cultural and other sources of misunderstanding.

Cooperative strategies are ever more common; firms often use alliances in order to pool technologies and development costs in search of innovation. Cooperation between auto and artificial intelligence companies to develop autonomous vehicles is one example of such agreements. However, firms must recognize that the strategic and economic benefits of cooperation cannot be sustained without a lot of effort to overcome human and organizational divisions.

Image by Gerd Altmann from Pixabay

The post The paradox of alliances– strong economics but fragile politics appeared first on OUPblog.

July 18, 2019

Did Caravaggio paint Judith Beheading Holofernes?

A disconcerting exclusion of alternative views and scholarship has marked the very carefully choreographed two-year long build-up toward the most controversial sale of a seicento picture this year—that of the so-called Toulouse Judith Beheading Holofernes, ascribed to Caravaggio.

The arguments presented in its favour look compelling. A contemporary document refers to it in Naples in 1607; a copy of it by Louis Finson can be found in Naples; scientific data match the imprint of Caravaggio’s Neapolitan work; and its provenance—despite many blanks—seems to match. Caravaggio scholars have been looking for a lost Judith Beheading Holofernes for years and the spectacular context of the painting’s discovery in an attic in April 2014 after having been lost for decades made the entire story even more alluring. “Leaning against a wall, it had been completely hidden behind old box springs and mattresses,” recalled auctioneer Marc Labarbe. Following its display in Paris, London, and New York in preparation for the auction slotted for 27 June this year at the regional Labarbe auction house in Toulouse, it was pulled unceremoniously a few days before the planned action sale after being snatched up by an anonymous buyer.

In fact, the analysis of documents and texts, technical and connoisseurship considerations paint a different picture. The attribution to Caravaggio has been strongly challenged and dismissed on a number of occasions, including during two Scholars Day events held in front of the painting at the Pinacoteca di Brera (February 2017) and the Musée du Louvre (June 2017). My view was clear in both instances. The painting is not by Caravaggio.

Caravaggio scholarship is somewhat divided on this picture. This is not new or strange. There have been similar debates for decades regarding a couple of other paintings that have entered Caravaggio’s story on controversial grounds. Some paintings hang on tenaciously and feature in exhibitions and catalogues. Others get dismissed more rapidly.There’s nothing wrong in this, because ultimately this is one of the great fascinations of connoisseurship and scholarship.

The Toulouse Judith Beheading Holofernes is a fascinating painting that throws significant light on the context of Caravaggio’s short but intense first Neapolitan stay, from September 1606 to June 1607, before his very unexpected departure for Malta. The traditional narrative is of the artist as a loner, working in isolation, jealously guarding his methods, and averse to artistic exchange. In reality, he most likely worked in a context of colleagues walking into their fellow artists’ workspaces to exchange views and help each other. That Caravaggio disliked rivals in Rome is well known, but he also had many artists who were close to him. Caravaggio clearly needed help in Naples; he required studio space, materials, carpenters, and manpower to (at the very least) stretch the large canvases of paintings such as the Virgin of the Rosary (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna), the Seven Works of Mercy (Pio Monte della Misericordia, Naples), Crucifixion of St Andrew (Cleveland Museum of Art) and the Flagellation (Museo di Capodimonte). It seems that he got particularly close to the workshop of the Flemish painter Louis Finson, who had settled in Naples in 1605 (or shortly before), and most probably established a working relationship with him.

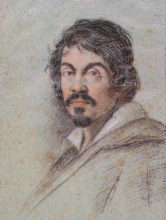

A portrait of the Italian painter Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio by Ottavio Leoni, c. 1621, Biblioteca Marucelliana. milano.it, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

A portrait of the Italian painter Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio by Ottavio Leoni, c. 1621, Biblioteca Marucelliana. milano.it, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.The Toulouse painting, more than anything else, seems to emerge from this context. It has the undeniable aura of Caravaggio’s ‘presence’, of being painted by someone who knew Caravaggio’s manner and technique well, and by someone who probably interacted with the artist regularly. On the other hand, it lacks the strength of Caravaggio’s Neapolitan works, the sheer power of narrative, the striking surety of brushwork, the dramatic vigour of approach, and the intensity of his characters.

Its sale in June coincided with the notable exhibition Caravaggio Napoli (12 April – 14 July 2019) at the Museo di Capodimonte (and the Pio Monte della Misericordia) where his Neapolitan masterpieces were placed in close proximity. In the halls of that show, one could not fail to note that the Judith (absent for obvious reasons) would not have made the mark as an autograph work by the Lombard artist. In many ways, it should have been there, because the exhibition also explored the immediate context around Caravaggio and the works of those who were instantly impacted by the power of his brush. Had the painting been in the exhibition, it might have been pulled from the auction for a different reason.

Featured Image credit: Caravaggio’s original Judith Beheading Holofernes, painted between 1598 and 1599, now held at the Palazzo Barberini. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Did Caravaggio paint Judith Beheading Holofernes? appeared first on OUPblog.

July 17, 2019

Idioms: the American heritage

Idioms, especially if we add proverbs and familiar quotations to them, are a shoreless ocean. Especially numerous are so-called gnomic sayings (aphorisms) like make hay while the sun shines, better safe than sorry, and a friend in need is a friend indeed. Their age is usually hard or even impossible to determine. Since most of them reflect people’s universal experience, they may be very old. In contrast, such undecipherable phrases as kick the bucket, put a spoke in someone’s wheel, or cut the mustard are fairly recent. At least they presuppose the existence of buckets, spokes, wheels, and the cultivation of mustard. (This type of reasoning is called relative chronology and sometimes yields useful results.)

More important is the fact that in the Germanic languages (and English is one of them) metaphorical sayings, like an extensive use of metaphors in general, are relatively late. There were few of them before the Renaissance. And yet, now that they are with us, we seldom know where they came from. To put a sock in it “to pacify someone, to make one quiet down” is, or so it seems, a British twentieth-century invention (with sock being rather enigmatic), while it blew (knocked) my socks off appears to be a late Americanism. Obviously, our conclusions about the chronology of such sayings depend on their occurrence in books, newspapers, or some other written sources. The time gap between coining and recording them may but needn’t be too long.

In my etymological database of approximately 1,500 idioms, about sixty are probably or certainly Americanisms. Perhaps a quick view of them will be interesting to our readers. The New World provenance of some needs no proof. Such are, for example, honest injun, recorded very early (1676), Lynch Law (1811), and almighty dollar. The first of them makes us wince. It means “my word of honor,” and its derogatory sense is likely, for the suggestion must have been that an Indian is never to be trusted (an honest Indian is thus a wonder). Mark Twain’s characters Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn regularly use this American equivalent of British honour bright, but there is no way of knowing to what extent his novels contributed to the popularity of the expression. In any case, the southerners Tom and Huck did not learn it from books.

The origin of even such seemingly obvious idioms is not always clear. For example, is the interpretation given above (an honest native is a wonder) correct? Lynch Law sent historians looking for the true Lynch. Some studies of this subject are excellent, but the identity of Mr. Lynch is still not entirely clear. Almighty dollar (1836) has been traced to Washington Irving, possibly modeled on almighty gold. In dealing with idioms, one often wonders whether the phrase in question is worth considering. For instance, does the phrase the American way exist? It probably does, but how idiomatic is the locution the American way of life?

Also, some phrases referring to places have become proverbial. Such are White House (Washington D.C.), Downing Street 12 (London), and perhaps Sleepy Hollow, the latter immortalized by Washington Irving. One hesitates to call them idioms, because they are fully transparent. However, take Foggy Bottom. As an area, the term applies only to a relatively small section of Northwest Washington between White House and Georgetown. But as a political term it refers to the State Department only, rather than to government in general. It was presumably coined on analogy with Whitehall (the main residence of English monarchs in the sixteenth and the seventeenth century) and Quai d’Orsai (the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs is situated on that embankment in Paris). To be sure, the name does not sound complimentary.

How foggy is Foggy Bottom? Image via Wikimedia Commons, CC by 3.0.

How foggy is Foggy Bottom? Image via Wikimedia Commons, CC by 3.0.One author wrote: “My personal recollection associates the term as well with the gas works and its emanations, which until recently [1962] were distinguishing qualities of Foggy Bottom.” Another correspondent suggested the following: “A friend who lived in Washington D.C. mentioned FB as an area district name. This would take it to 1915 and earlier. I assume that bottom is a reduction of bottomland, and that foggy refers to the morning miasma of the Potomac or its eastern branch, the Anacostia.” The origin of place names is a branch of etymology in its own right. However, at the moment we are not interested in geography. Clearly, Foggy Bottom has gained such popularity as a political term because of its association with the State Department.

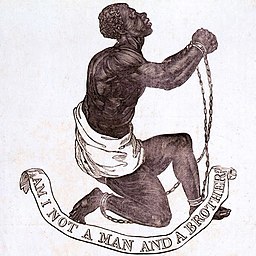

A man and a Brother. Image via Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain.

A man and a Brother. Image via Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain.No one will doubt that honest injun is an American coinage. The same, we would think, must be true of the antislavery slogan a man and a brother, but it is not. The phrase was adopted as a seal by the Anti-Slavery Society of London. In 1768, Josiah Wedgwood produced a medallion showing a Negro in chains, with one knee on the ground and both hands lifted to heaven. In the printed book (1799), the design of the seal of the Society for the Abolition of Slavery was modeled by William Hackwood under Wedgwood’s directions and was laid before the committee of the Society on October 16, 1787. It was approved, and “a seal was ordered to be engraved from it. In 1792 Wedgwood, at his own expense, had a block cut from the design as a frontispiece illustration for one of Clarkson’s pamphlets.”

This is Josiah Wedgwood, the preeminent potter. Photo © Stephen Betteridge (cc-by-sa/2.0).

This is Josiah Wedgwood, the preeminent potter. Photo © Stephen Betteridge (cc-by-sa/2.0).Two more American phrases with names in them may be worth mentioning. One is Annie Oakley “a pass to circus and other performance after it is punctured.” It commemorates Annie Oakley, famous for sharpshooting achievement. One of her tricks was to cut out the pips on a playing card. She was the star of a once popular show. Is Annie Oakley an idiom? Another item from my database is Bronx cheer “a sound of derision made by blowing through closed lips with the tongue between them.” I’ll quote the entry in full: “The same as British blowing a raspberry. Some say the cheer originated at the old Fairmount Athletic Club in the Bronx; others associate it with the Yankee Stadium, also in The Bronx. Mr. Clarence Edward Heller, in our Sunday Visitor, a Catholic publication, once traced the origin back to the thirteenth century, in the south of Italy. His point was later confirmed by an editor of an Italian paper (published here in the United States), who said that the mouth salute has long been somewhat common in that region. Damon Runyon says the cheer (that is, the vulgar form) was discovered and titled by Tad [Thomas A. Dorgan, 1877-1929], the great cartoonist, a matter of thirty years ago. It came about, he states, when Tad made a trip of exploration to the Fairmount Boxing Club in the Bronx” (American Notes and Queries 2, 1942, 106-107). The OED dates the phrase to 1929. The Internet (“The Phrase Finder”) offers some discussion of Bronx cheer. It is different from what is said above, but my conclusions are limited, because they derive entirely from my modest database. Yet I do consult dictionaries of the why do we say so? type. Not to put too fine a point on it, some suggestions in them should be taken with a grain of salt.

Annie Oakley. You have to be a sharpshooter to pass into in idiom. Image via Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain.

Annie Oakley. You have to be a sharpshooter to pass into in idiom. Image via Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain.If this post invites questions and comments, I’ll perhaps continue with the subject.

Feature image credit: Whitehall, via Leonard Bentley on Flickr. CC BY-SA 2.0.

The post Idioms: the American heritage appeared first on OUPblog.

A forgotten African satirist: A.B.C. Merriman-Labor

In 1904, twenty-six-year-old A.B.C. Merriman-Labor stamped the red dust of Freetown’s streets from his shoes and headed for London. There he intended to prove his literary skill to the world. The Sierra Leone Weekly News had assured him that his color would no obstacle there, and he could “go anywhere, wherever his merits, either intellectual or social, will take him.”

Freetown’s robust literary community, its clubs, library, and lectures had nurtured him and encouraged his literary dreams. Already he had published a novella, produced a play, and given lectures that were published in the U.K. then distributed worldwide. But it was his 1898 essay on the Hut Tax War that had made his name.

He knew the ideas in the essay would be dismissed if he spoke as the Krio A.B.C. Merriman-Labor, a junior clerk in the Colonial Secretary’s office, so he signed it “an Africanised Englishman Twenty Years in British West Africa.” In the piece, he slyly promised a dashing war story that would make “pleasurable reading … for every loyal English subject…of the British Empire,” then daringly described an out-of-touch colonial administration that understood very little of what was happening in the vast land it governed. The true hero of the war in his telling was the Temne chief Bai Bureh, a plucky leader of wit, cunning and honor, who outwitted the British forces at every turn. The exposé quickly became a sensation in West Africa.

For the next six year, Merriman-Labor saved every penny as he worked his way up the civil service ladder. Then, in 1904 he left his respectable government job and headed to the center of the empire.

London, it turned out, was not as perfect as he had been led to believe. Its streets were not paved with gold, but rather, he joked, “plastered over with mud and something…left behind by the hundreds of thousands of horses.” This gap between the idealized Sierra Leonean vision of the metropolis and its stark realities inspired Merriman-Labor’s London writing. First came the articles for the Sierra Leone Weekly News, then the 10,000-mile lecture tour around Africa called “Five Years with the White Man,” and finally his only surviving full-length book Britons Through Negro Spectacles.

Merriman-Labor was determined to speak important truths but knew as a black man he could not speak those truths directly. In Britons, he disguised himself as comedian to make his words more palatable to his white readers. “Considering my racial connection,” he wrote, “I am of the opinion that the world will be better prepared to hear me if I come in the guise of a jester.”

Part travelogue, part reverse ethnology, and part spoof of books by ill-informed “Africa experts,” Britons camouflages its radical ideas with jokes, puns, satire, burlesque, and lampoon. It describes a walk around London with Merriman-Labor acting as a guide to a newly arrived African friend. As they pass landmarks, observe people, and discuss British manners, the city’s famous clocks toll, marking the passing day. Nine years before James Joyce strolled Leopold Bloom around Dublin and sixteen years before Virginia Woolf ambled Clarissa Dalloway through the West End, Merriman-Labor walked arm-and-arm with Africanus from Poultry Street to Hyde Park.

On the surface, the silly jokes offer the stuff of fun, providing, as the Dundee Courier concluded, an “hour or two of quiet amusement.” But its purpose is much more daring than its comical pose. By acting as an ethnographic observer, Merriman-Labor asserts the right of being the observer, not the observed. In Britons, the white Europeans are the exotic others who need to be explained.

No wonder it provoked strong negative reactions. As a criticism of English institutions, The Law Journal declared, “it is valueless.” The Daily Expresscharacterized its comic portrait of British life as “low jests” from a “crude pen.” Its audacity was palpable in Africa. F. Z. S. Peregrino, founder of Cape Town’s first black newspaper, saw its irreverent jibes as so inflammatory, he prevented Britons from being circulated.

In the end, Merriman-Labor was made to pay for his audacity. Britons Through Negro Spectacles was a commercial failure. Its costs sunk him so deep into debt, he was forced into bankruptcy.

Ultimately, life in London led him to cast off his British identity as yet another disguise. Disgusted with the country that had claimed him, educated him, and then disowned him, he discarded his British name and became Ohlohr Maigi. It was an identity he only possessed for a few years until overwork in World War I munitions factory led to an early death at age forty-two.

Merriman-Labor’s work floated into obscurity, but not oblivion. His clever, irreverent, joyful voice rings through Britons Through Negro Spectacles, reminding us that for those willing to listen, voices from the margins have important things to teach us.

Featured image credit: Typewriter by Tama66. CC0 via Pixabay

The post A forgotten African satirist: A.B.C. Merriman-Labor appeared first on OUPblog.

July 16, 2019

Twenty years since Eyes Wide Shut

Twenty years after Stanley Kubrick’s death and the release of his last film, Eyes Wide Shut, the film and its director have reached a peak of popularity and public interest. The film met with a decidedly mixed reception on its original release as audiences, led to believe they were about to see an erotic film with Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman, discovered instead a deliberately paced, intellectually, and emotionally challenging meditation on marriage, fidelity, jealousy, domesticity, desire, and dreams.

Eyes Wide Shut took a full two years to shoot. But, more importantly, it was on Kubrick’s mind for 50 years. He began thinking of adapting Arthur Schnitzler’s fin-de-siècle Viennese novella, Traumnovelle, at the same time as he began making feature films in the early 1950s. There were many stops and starts along the way as Kubrick struggled to find the right way to do it. Finally, in the mid-1990s, he put his doubts to rest and plunged into the demanding task of making the movie that would become his last.

He gave the task of writing the initial screenplay to Frederic Raphael, a seasoned screenwriter, and the two clashed almost immediately. Feelings were so raw on Raphael’s part that he wrote an unflattering memoir of working with Kubrick, Eyes Wide Open. What Raphael failed to realize—or perhaps he realized it too well—was that he was something of a hired hand, someone to spark Kubrick’s imagination. As we see throughout the numerous drafts of the screenplay, Kubrick kept pushing and guiding Raphael’s hand. “NO!!” he writes in the margin. “Keep to A[rthur] S[chnitzler].” Or more intriguingly, as the orgy sequence was being written: “He should first be very sexy, then turn Pulp Fiction dangerous and brutal.” Raphael did as much as he could. Kubrick took over and finished the screenplay himself.

At the same time, Kubrick engaged in a typically detailed, all but obsessive, period of pre-production. Kubrick looked at everything—all the masks he could import from Venice for the orgy sequence; detailed measurements of Tom Cruise’s face for his mask. He sent out photographers to scour London, and other parts of the UK, for images that might be of use should he want to shoot on location. (As it turned out, much of the film, including the streets of Greenwich Village, was shot on studio sets.) He ordered catalogues of women’s underwear. He read widely not only books about Schnitzler, but Karen Horney’s work on psychology and a book called Cult and Occult, detailing bizarre sexual practices.

Image credit: Costume and mask worn by Tom Cruise in Eyes Wide Shut displayed at Stanley Kubrick: The Exhibit, TIFF, Canada. Photo by Carlos Pacheco. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: Costume and mask worn by Tom Cruise in Eyes Wide Shut displayed at Stanley Kubrick: The Exhibit, TIFF, Canada. Photo by Carlos Pacheco. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.What followed was a shoot that was a remarkable period of concentration, patience, and working against Kubrick’s own biological clock. Despite deteriorating health, Kubrick insisted that every element in the film be exactly what he wanted, no matter how long it took. If a location was not to his liking, he moved on to another. If a set was not just so, he had it rebuilt. His actors—Cruise and Kidman—stuck with him throughout the arduous shoot. Others left, like Harvey Keitel, who was originally cast to play the role of Victor Ziegler and was replaced by Sidney Pollack. Begun in November 1996, the shoot was completed in June 1998. Months of editing followed.

Finally, in early March 1999, Kubrick sent a print of Eyes Wide Shut by air to New York (Kubrick never flew; in fact, he never traveled very far from home) where it was screened for Cruise, Kidman, and Warner Bros. executives. The projectionist was asked not to watch. Everyone was pleased with the film.

On March 7th, Kubrick died. He left much of the work of preparing a distribution print to family and co-workers, who made numerous small decisions, including blacking out figures in the orgy in order to get an “R” rating for the film and adding the pre-credit shot of Kidman dropping her dress, one of the “erotic glimpses” that Kubrick had filmed. Kubrick had always tinkered with a film before, and sometimes after, distribution, famously cutting 20 minutes from 2001: A Space Odyssey during its initial run. This has led to much speculation about whether the Eyes Wide Shut we have is the film Kubrick would have wanted us to have had he lived. The question, of course, is moot, an unsatisfying quest for what might have been. The film we do have tells a complete, if enigmatic, story of male sexual instability, of an uncertain reconciliation of a couple whose marriage had become ferment because a wife admits that she has sexual longings, of a world in a liminal state between dream and waking.

Despite the ongoing conspiracy theories that have surrounded the film’s orgy sequence, the film is not about the Illuminati or child sex trafficking, but rather the instability of seeing and desiring, of being certain in one’s gender, sexuality, and marriage. It is about class and power and the masks used to keep our identities from ourselves and others. The negative reviews that greeted the film’s opening have been replaced by serious scholarly inquiry into its enigmas. The Stanley Kubrick Archive at the University of the Arts in London have offered unparalleled access to the director’s working methods, offering detailed information on the particulars of his creative process on this and all his films. Eyes Wide Shut itself keeps opening new insights on each viewing, new interpretations—like a dream.

Featured image credit: Masks from the film Eyes Wide Shut displayed at Stanley Kubrick: The Exhibit, TIFF, Canada. Photo by Carlos Pacheco. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons .

The post Twenty years since Eyes Wide Shut appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers