Umm Zakiyyah's Blog, page 8

June 30, 2018

Unconditional Love Doesn’t Exist, Nor Is It Praiseworthy

“Too much control thrives when family members cling to a myth that everything is perfect when it’s not.”

—Dan Neuharth, If You Had Controlling Parents

The following is an excerpt from Reverencing the Wombs That BROKE You by Umm Zakiyyah:

Perhaps it is through observing the enduring affection between mother and child that has most significantly inspired our concepts of unconditional love, a love so strong that it is altered by neither time nor circumstance. But is it real?

In speeches and in writing, unconditional love is praised so highly and spoken about so freely that it seems almost sacrilegious to pose a question that challenges its existence. However, when we are continuously faced with the reality of children neglected and abused by their very own parents—sometimes from birth, sometimes later in life—it behooves us to take a moment to consider what we mean by the term unconditional love. But perhaps more importantly, it is necessary to consider the effects that this definition, as well as its underlying assumptions, has on those who believe in it wholeheartedly, especially when their traumatic personal circumstances suggest otherwise.

When Melanie speaks about her mother loving her as best she can and vice versa, she is not speaking about a natural, effortless love that is unaltered by human choice or circumstance. She is speaking about a love based on conscious, continuous work, a love rooted in deliberate behavior and choice, even as this love is inevitably imperfect. She is not speaking of what many term “unconditional love.”

If we are to understand “unconditional love” according to the apparent meaning of the term, in my view, it is not a concept that exists amongst human beings. Moreover, even if it did exist, it is not a unique, praiseworthy or desirable type of love. My view is shaped not only by my faith tradition, but also by the obvious reality of the world in which we live. As I reflect in my personal journal:

Unconditional love does not exist, nor is it praiseworthy. All love comes with conditions, and should. God Himself has conditions on whom He loves: “But if they turn away [from obedience], then verily, God loves not those who disbelieve” (Qur’an, 3:32).

The Qur’an also specifies the conditions for gaining His love: “Say [O Muhammad], ‘If you love God, [then] follow me. God will love you and forgive you your sins. For God is Oft-Forgiving, Most Merciful’” (Qur’an, 3:31).

Not Even a Mother’s Love Is Unconditional

Regarding a mother’s natural love for her child, I reflect in my journal:

Natural or innate love, like that between a mother and child, is not the same as unconditional love. Natural love is like a seed lying in fertile ground with no prior effort on your part. However, for that seed to blossom into a fragrant flower or delectable fruit, it requires daily nurturing and care. Otherwise, it dies. Similarly, all love—whether innate or romantic—is conditional upon some level of effort and dedication if it is to remain alive.

Thus, those who say they believe in unconditional love are not really speaking of love that is unconditional per se. Rather they are speaking of deeply felt lasting love. They are speaking of a love that has endured despite the many storms of life that had threatened to weaken or uproot it. Nevertheless, in poetic matters of the heart, hyperbole is generally more palatable and preferable than technical truth. As such, the term unconditional love is favored more than the more accurate term conditional love. In this vein, the usage of the term unconditional love is akin to a term of endearment: Like calling a loved one my angel, baby, or honey, it is meant to be sentimental, not truthful.

Enduring Love, Not Unconditional Love

I propose that a better and more honest term than unconditional love is enduring love, a love that endures precisely because it meets the conditions necessary for that love to endure. In other words, when we are observing what we call “unconditional love,” we are really observing the positive side of conditional love, the only type of love that exists.

In this context, however, it is important to note that the term conditional love does not mean that humans are consciously or overtly demanding that loved ones fulfill certain conditions in order to earn or sustain their love. The term merely refers to the inherent nature of human love itself. Nevertheless, not all conditional love is equal, and perhaps the most obvious example is that of the oft-enduring bond between mother and child compared with the oft-disrupted bond between romantic partners.

While the compassionate bond between a mother and child is arguably the most powerful expression of love on earth, this fact alone does not make it unconditional. It simply makes it possibly the most enduring bond of love and the most difficult to disrupt. But that it can be (and often is) disrupted suggests that certain conditions (whether conscious or unconscious) were not met to ensure that it was sustained long-term.

Before I explain how this all connects to the story of Melanie and others suffering similar trauma, I believe it is important to note that my view of unconditional love is rooted in how I define love itself. To me, while love is definitely rooted in unseen feelings of the heart, love is not merely unseen feelings of the heart. Love, like faith, requires both internal and external manifestation before it can be rightly called love. In other words, love is an action word more than it is a feeling word, though some minimal level of feeling is necessary to make it complete. However, love does not exist simply because someone claims or believes that it does, even if they are speaking of their own heart.

The Myth of Unconditional Love

Naturally, because unconditional love itself is not rooted in human reality, those who claim to believe in it have varying and often contradictory assumptions regarding its existence. Ironically, those with the healthiest view of “unconditional love” define it as rooted in conditions, even as they do not consciously realize they are placing conditions on its definition. In other words, for all practical purposes, they define “unconditional love” as conditional love that has yielded positive, lasting results.

Put another way, their definition is really describing enduring love (or what can be viewed as healthily nourished natural or innate love), the positive side of conditional love. Because this use of the term unconditional love is not really in reference to love without conditions, its mythical aspects exist only in terminology, not in meaning. Thus, when one’s belief in unconditional love is rooted in hyperbolic terms of endearment, it poses very little danger—so long as it is continuously understood as enduring conditional love, as opposed to effortless unconditional love (which does not exist).

However, the dangers of believing in unconditional love become most obvious when we explore the arguably more popular and widespread understanding of it: love that endures forever and remains unaltered simply because the one deserving of it exists. (Here, I’ll admit a caveat to my earlier reflection that unconditional love does not exist nor is it praiseworthy. In this context, I am speaking only of love amongst human beings. I am not speaking of the love humans should have for their Creator and what and whom He loves. Theoretically, it can be argued that in the case of humans loving God, unconditional love is indeed praiseworthy, and I would agree. However, even in this case, humans are incapable of showing this form of unconditional love toward God in the way that He deserves. As such, our human faults and failings render even this praiseworthy theoretical example as proof that unconditional love does not exist).

Dangers of the “Unconditional Love” Myth

When unconditional love is understood according to its more popular usage—effortless love that endures irrespective of time or circumstance—the dangers of believing in it become more obvious. While cases of abuse and neglect are often cited as exceptions to the existence of unconditional love, it is often the belief in unconditional love that not only fuels the abuse, but also allows it to last for so long unabated.

When parents assume that all of their actions are motivated by unconditional love, they can become blind to when they are not behaving lovingly. Moreover, they are even less likely to recognize when their actions are motivated by the opposite of love, be it resentment, envy, or even hatred. In many homes, the term “tough love” (which refers to healthy though unpleasant, necessary disciplinary measures inspired by genuine concern for the child’s well-being) is used as a euphemism for abuse and mistreatment, which is often rooted in the parents’ own unaddressed emotional trauma.

In more extreme cases, it is the parents’ belief in unconditional love that actually inspires deliberate mistreatment of their children. In other words, some parents define “unconditional love” as the license to, quite literally, do whatever they want with or to their children. In this erroneous belief system, parents view anything and everything they do as an act of love. Consequently, when a child’s emotional, psychological, or physical wellbeing is viciously assaulted, a parent will claim that he or she is doing it “for their own good.”

Due to their view that parental love has no conditions or limits (i.e. it is “unconditional”), these parents ascribe to the pathology of complete and literal ownership of their children’s minds, bodies, and souls. “I brought you into this world, and I can take you out!” is a common proclamation made by these parents. Because they view the harm they inflict on their children as a manifestation of “unconditional love,” they genuinely believe their children should love and appreciate them no matter what. Often these abusive parents cite the very acts that traumatize and harm their children as proof of their unconditional parental love.

Love As a Weapon in Abusive Families

In the case of Melanie’s mother, we can see a distinct difference between how Melanie is treated and how her younger sisters are treated. This is an obvious example of how even parental love is conditional. In Melanie’s case, the level of love she was shown was in direct relation to the circumstances surrounding her mother’s pregnancy [i.e. Melanie was born from her mother being raped, while her sisters were born from her mother getting married].

Though Melanie’s situation is arguably an extreme example, it is well-known that even in families that are considered healthy, normal, and functional, obvious favoritism exists in the parents’ interactions with their children. In fact, emotional trauma is not uncommon in even these “good families.” As such, there are often many parallels between the emotional struggles of children who have suffered obvious abuse and those who have suffered subtler forms of trauma at the hands of their parents.

Regarding the psychological harms of believing that love is unconditional, especially in families, consider this excerpt from the blog “Myth of Unconditional Love” by Jennifer Stuck:

I’ve been bombarded with the idea of unconditional love for as long as I can remember. Everywhere from home, to church, to Valentine’s Day commercials, people have pushed the concept that I should show love with no strings attached and expect nothing in return…But what does this type of thinking do to my personal boundaries? And more importantly, why SHOULDN’T my love have conditions?

I’ve recently become aware that the belief in unconditional love has interfered with my healing from childhood sexual abuse. In the past, I found it difficult to express anger towards the people who hurt me. My abusers weren’t my family and I never loved them, but I did care deeply about the people in my family who failed to protect me. The positive feelings I felt for my family coupled with the anger I felt about them neglecting me was confusing.

I was always taught that I should love no matter what, forgive all mistakes, and never question their place in my life. They were my family after all. But my anger went against the definition of unconditional love I was always taught…I was already harboring guilt after being sexually abused, and the idea of unconditional love just piled on more.

On top of adding to my guilt, being told I should love someone even when they have hurt or neglected me was like being told to ignore my personal boundaries. Years of childhood sexual abuse had already taught me to ignore my feelings and put everyone else’s needs first. The belief in unconditional love just reinforced that. According to everyone else, my feelings didn’t matter and I had no choice in who or when I loved. I wasn’t allowed to place conditions on my love. I was supposed to love them no matter what they did. But that was in their best interest, not mine.

The whole concept of unconditional love has been used by abusers and the people who protect them for generations to keep victims silent. When you think about it, who else would require love without conditions? (Stuck, 2011)

What’s Wrong with Unconditional Love in Marriage

Regarding believing in unconditional love in a marriage, Willard F. Harley, Jr. (a professed Christian) writes in part one of “What’s Wrong with Unconditional Love?”:

But the [marriage] vows that I made…were not for unconditional love. My vows were that I would care for [my wife] regardless of conditions beyond our control…

So let me explain to you what unconditional love in marriage is, and then we’ll see whether or not it makes any sense to promise such a thing…

“Unconditional” means that there are no prerequisites or contingencies to the promise. The promise of love is to be made regardless of all circumstances, including what the other person chooses to do. There should be no confusion regarding its meaning.

“Love,” however, is a different matter, and I’ve seen many different ways to define it. I define love as applied to marriage in two ways: (1) romantic love which is the feeling of incredible attraction to someone and (2) caring love which is meeting someone’s needs. When you’re in love, you feel something, and when you care, you do something…

My definitions of love makes [sic] the spouse very unique, but the promise itself very conditional. If I promise to be incredibly attracted to [my wife] Joyce, and to meet her emotional needs for the rest of our lives together, it doesn’t make sense if there are no conditions attached…

If I had promised to be in love with Joyce unconditionally, I would have failed to understand how romantic love is created and destroyed. It’s not what I do that causes me to be in love with Joyce–it’s what she does. So I can only promise to be in love with her if she meets my important emotional needs, and avoids hurting me. I have nothing to do with it, except to give her an opportunity to make those deposits.

My second definition of love, caring love, makes unconditional love seem possible. Technically, I could try to meet my wife’s emotional needs without condition. But could I do it indefinitely, and would it be a good idea?

Let’s take a few examples. Suppose a wife were to have an affair, divorce her husband, and marry her lover. Should her ex-husband continue supporting her financially if they had no children together? Should he provide the same support that he would if they were married? Should he be there to help her through life’s struggles? Some who believe in unconditional love feel that he should.

Or, suppose a husband sexually molested their children and ended up in prison. Should his wife continue to meet his emotional needs during conjugal visits? Some who believe in unconditional love think that she should.

What if a husband were to beat his wife senseless in a fit of drunken rage? Should she continue to meet his emotional needs? I once counseled a couple where the husband tried to kill his wife three times. After his last effort he buried her in a shallow grave because he thought she was dead. But she managed to recover, dig herself free, and crawl for help. Should she give him another chance? Should she meet his emotional needs for the rest of his life? The elders of her church thought she should because they believed in unconditional love. After I encouraged her to divorce her husband, they never referred anyone to me again…(Harley, n.d.).

Regarding religion being used to support the concept of unconditional love, Harley says further:

I’ve heard almost every argument in favor of unconditional love, and I’ve found that the argument that is the most difficult for me to refute is religious. While this argument has been made by advocates of many different religions, I’ll focus on the Christian argument because that’s the faith that I endorse.

The argument goes something like this: We should love our spouses unconditionally because Jesus Christ loves us unconditionally. Even if it’s not safe or practical to do so (as with infidelity, physical abuse, or divorce) we should love unconditionally out of obedience to God. While I certainly encourage being in obedience to God, I can’t find any text from the Christian Bible that suggests that conclusion.

The phrase, “unconditional love” is found nowhere in Scripture. We read “For God so loved the world that he gave his one and only Son, that whoever believes in him shall not perish but have eternal life” (John 3:16). Those who encourage us to love unconditionally take this to mean that God loves us all unconditionally. But if that’s true, it must be my third meaning of the word, love–he wishes us the best in life. That’s because the verse goes on to explain that we must do something to save ourselves. According to this verse, we must meet his conditions to be saved…

The concept of salvation itself is expressed in many different ways in various texts, but it always comes with a condition. It’s never suggested that salvation comes with no strings attached. As one example, “If you confess with your mouth, ‘Jesus is Lord,’ and believe in your heart that God raised him from the dead, you will be saved” (Romans 10:9)…

So if there’s no religious reason to give or receive unconditional love in marriage, we’re left with practical reasons. And I know of none (Harley, n.d.).

Moral and Spiritual Harms of “Unconditional Love”

Though the depths of the additional danger of believing in the myth of unconditional love are beyond the scope of this book, I think it is beneficial here to mention briefly the intellectual, moral, and spiritual harms this belief entails. In an article entitled “The Myth of Unconditional Love,” writer Walter Hudson references Amazon’s critically acclaimed Transparent series to illustrate his point:

While watching the…trailer for Amazon’s Transparent, I was struck by the tagline, “Love is unconditional.” In the context of a show about a transgender father who comes out to his grown children, the idea seems clear. If his children love him, they won’t care that he thinks he’s a woman.

Is that true though? Do I need to accept anything my loved ones say, think, or do for them to remain loved ones? Does love require universal acceptance?

The popular notion of “unconditional love” emerges from post-modern moral relativism. It is an interpersonal application of the idea that everything is equally valid and equally true. In that context, judgment has become hate…One cannot disagree with the gay orthodoxy without being labeled a hater…

We’re dealing with a particularly insidious lie that cheapens love by transmuting it from a value-based emotional response to an autonomic pleasantry. Put another way, unconditional love is nothing special. If love is unconditional, then anyone deserves it. If anyone deserves it, then the particulars of an individual’s behaviors, beliefs, and values do not matter…

Ironically, the unconditional love crowd typically punctuate their rhetoric with the sentiment “love people for who they are.” But that doesn’t make the least bit of sense. You can’t both love someone for who they are and love them unconditionally. Their identity is a condition. They are not someone else. From this we quickly realize that the real exhortation of “unconditional love” is to accept whatever taboo, be it homosexuality, transgenderism, or any of a hundred other things…

Indeed, true love drives continual growth and improvement. True love responds to values sought and attained, to principles manifest in action.

I love my wife for who she is, not for whatever she happens to be, but for what she believes and how she lives her life. Her values align with my own. I could not love her otherwise. If I claimed to, it would be a lie…

Love requires judgment. Love upholds standards. Love sets conditions. When our loved ones fall short, we correct them in love. If we didn’t care, we wouldn’t bother. In that sense, what the “unconditional love” peddlers sell is not actually love, but a miserable and toxic indifference (Hudson, 2015).

Healing Through Letting Go of “Unconditional Love”

I spent a considerable amount of time explaining the myth of unconditional love because I believe that understanding this myth is crucial for many survivors [of abuse]. Even for those of us who have not suffered emotional trauma or abuse in our lives, navigating life with a healthy, realistic view of love can improve our relationships with friends, family, and loved ones.

Understanding both the limits and potential endurance of love can inspire us to be more mindful of our own behavior and intentions, and it can free us from self-blame when someone we imagine loves us behaves in a harmful or abusive manner. Many children of abuse who believe their parents love them unconditionally often look for faults within themselves to explain the hurtful treatment they consistently suffer at the hands of their mother or father.

Logically, if a parent loves a child unconditionally, any negative treatment is rooted in a problem within the child, not in the limits of the parent’s own ability or willingness to love. Likewise, the concept of unconditional love implies that any unjust behavior toward one child and preferential treatment toward another must be understood as the child’s fault.

However, if a child understands that parents are merely human beings with very real limits to their ability and willingness to love, then he or she can move beyond self-blame to self-healing—guilt-free. This healthy psychology and outlook on life allow adult children of abuse to engage in necessary self-care without viewing their healing journey as “selfishness” simply because their parents are angry or resentful of this newfound independence.

READ FULL BOOK: Reverencing the Wombs That BROKE You. [CLICK HERE]

Umm Zakiyyah is the internationally acclaimed author of twenty books, including the If I Should Speak trilogy, Muslim Girl , and His Other Wife . Join UZ University to learn how you too can find your writing voice and share inspirational stories with the world: UZuniversity.com

Subscribe to Umm Zakiyyah’s YouTube channel , follow her on Instagram or Twitter , and join her Facebook page.

Copyright © 2016, 2018 by Al-Walaa Publications. All Rights Reserved.

REFERENCES

Harley, W. (n.d). What’s Wrong with Unconditional Love? MarriageBuilders.com. Retrieved September 11, 2016 from http://www.marriagebuilders.com/graphic/mbi8110_ul.html

Hudson, W. (2015, August 7) The Myth of Unconditional Love. Pjmedia.com. Retrieved September 11, 2016 from https://pjmedia.com/lifestyle/2015/8/7/the-myth-of-unconditional-love/ and https://pjmedia.com/lifestyle/2015/8/7/the-myth-of-unconditional-love/2/

Stuck, J. (2011, April 11). The Myth of Unconditional Love. OvercomingSexualAbuse.com. Retrieved September 11, 2016 from http://overcomingsexualabuse.com/2011/04/11/the-myth-of-unconditional-love/

The post Unconditional Love Doesn’t Exist, Nor Is It Praiseworthy appeared first on Umm Zakiyyah.

June 4, 2018

‘But I Don’t Want Forgiveness’

The following is an excerpt from the book And Then I Gave Up: Essays About Faith and Spiritual Crisis in Islam by Umm Zakiyyah:

Some years ago, I was sitting with a friend of mine and she started telling me about her struggles with hijab after becoming Muslim. She had grown up Christian and accepted Islam while she was in college.

“For me, hijab was the hardest thing,” she said. “I just didn’t want to wear it. So I made every excuse I could. ‘It’s too hot.’ ‘I can’t breathe’.” She shook her head, remembering. “But the funny thing is, I didn’t realize I didn’t want to cover.

“Until one day I was talking to some sisters and I was making the same excuses. And the sisters started trying to convince me, but for everything they said, I had an answer. And we kept going back and forth. But then a sister said something that I really couldn’t respond to.” She paused. “‘Just make du’aa. Pray that Allah makes it easy for you’.”

Her eyes grew distant, reflecting. “When she said that, I didn’t know what to say. In the back of my mind, I knew that if I asked Allah for help, I would wear hijab. And that’s when I knew I didn’t really want to cover. I didn’t even ask Allah to help me. Because I didn’t want Him to.”

• • •

When I hear stories like these, I think of the depths of the human heart. I think of how we think we know ourselves and our intentions. But, really, we don’t.

For almost every one of us, there’s something we know we need to change but simply won’t. The issue may involve not wearing hijab, not praying regularly, watching inappropriate TV and movies, intermingling, having “boyfriends” or “girlfriends”… And for each, we have a convenient excuse, if we bother to make excuses at all.

But in Ramadan, a lot of unpleasant things come to surface because the devils are chained and the depths of our hearts are exposed.

Yet most of us still manage to wriggle out of obedience to Allah, and the excuses abound…

There’s no point in wearing hijab in Ramadan if I know I’m just going to take it off later…

I don’t want to be a hypocrite…

I know myself, and I’m not ready to change my life…

But in each excuse, there’s one key component that’s missing.

Allah.

I don’t mean His name is absent. For most of us, it’s actually Allah’s name we use to justify our wrong.

Allah is Forgiving. Allah knows my heart. Allah’s my judge…

Or our favorite…

When I change, I’ll do it for Allah, not because people asked me to…

Yet Allah says, “And make not Allah’s (name) an excuse in your oaths against doing good, or acting rightly…” (2:224).

RAMADAN JOURNAL Page. CLICK HERE

When we’re not blaming Allah for our sins, we’re blaming our natural human weakness. And it’s true; humans are weak. But the truth is that this isn’t our chief shortcoming.

But human weakness is the chief shortcoming for those with high emaan.

Those with low emaan have as their chief shortcoming a diseased heart.

The strong believers constantly strive to do what’s right, but because of human weakness, they inevitably fall short. But their energy is spent striving against sin, not giving in to it.

The weakest believers don’t even bother striving; they’re quite comfortable in their life of sin. Their energy is spent defending their sin, not fighting against it.

…I don’t want forgiveness. I don’t want to change. I like the wrong I’m doing…

This is what it really boils down to. Otherwise, we’d just make du’aa, and pray that Allah makes it easy for us to do what’s right, even if we fall short at times.

But it starts with wanting change. And that’s not an easy thing for the human heart, especially for those of us content with our low emaan and life of sin.

Yet…

All will be forgiven during the month of Ramadan, except those who do not want to be forgiven.

And who does not want to be forgiven?

Those who do not ask.

The month of Ramadan is, more than anything, a month of opportunity. It is a time to set right things that are wrong. It’s a time to change course, even as you’ve no idea how you’ll walk that new path. It’s a time to ask for change, to beg for change, to cry for it—even if part of you doesn’t even want it.

And it’s okay if you have no idea how you’ll manage wearing hijab, praying regularly, shutting off that TV, or leaving alone those “cute” girls or guys.

It’s okay, because it’s not you you’re turning to for help.

It’s Allah.

And Allah is able to do all things.

Let us remember, too, that Allah is All-Forgiving. But, of course, to benefit from Allah’s Forgiveness, we first have to want it. And wanting forgiveness isn’t just saying we want it, or just uttering a prayer. It means we regret our sin. It means we hate our sin. And it means we take every step to avoid it.

And we never give up fighting against it.

That’s what it means to want Allah’s forgiveness.

That’s what it means to ask for it.

So it is upon each of us to closely examine our lives—and hearts—and ask ourselves a simple question.

Do you want forgiveness?

If our answer is yes, we know Who to turn to for help and guidance.

If our answer is no… well, there’s nothing for us to do except what we’ve always been doing.

READ FULL BOOK: And Then I Gave Up: Essays About Faith and Spiritual Crisis in Islam [CLICK HERE]

Essay originally published via saudilife.net

Umm Zakiyyah is the internationally acclaimed author of twenty books, including the If I Should Speak trilogy, Muslim Girl , and His Other Wife . Join UZ University to learn how you too can find your writing voice and share inspirational stories with the world: UZuniversity.com

Subscribe to Umm Zakiyyah’s YouTube channel , follow her on Instagram or Twitter , and join her Facebook page.

Copyright © 2010, 2018 by Al-Walaa Publications. All Rights Reserved.

The post ‘But I Don’t Want Forgiveness’ appeared first on Umm Zakiyyah | Author Writer Speaker.

June 2, 2018

No Place Like Home: American Teacher in Saudi

AUTHOR’S NOTE: I lived as an expat in Saudi Arabia from 2005 to 2013. This blog was written about my first experience as an English teacher there.

Some time after the tears of euphoria dry and reality sets in, anyone who has emigrated from their native land experiences what is commonly referred to as “culture shock.” For some, this simply means getting used to a new language, people, and way of life.

For me, it meant learning the “school system” as a new teacher at an international school in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia…

…

I arrived to work on my first day of teaching (which incidentally was about two months into the school year due to delays in my visa) prepared to have a class schedule, a student list, and an actual classroom. I thought perhaps I’d get the official teacher’s handbook complete with all the details, major and minor, of what I’d need to know and do as a new employee. And the teachers’ editions to the English texts I’d be using wouldn’t have been so bad either.

Instead, I got a stack of another teacher’s exams on my desk and was told to grade them.

“The supervisor said you have to mark these,” the teacher said as she deposited an enormous pile of her midterm exams on my desk. To top it off, the subject was Literature (which I would not be teaching, and even if I would be, I hadn’t read any of these stories! How then was I to evaluate students’ comprehension of them?)

I had the vague feeling that I was being taken advantage of, but I couldn’t be sure. After all, I was new to the school (in fact new to Saudi Arabia), and I had no idea if this was how things worked here.

Or didn’t.

As she walked away, I detected a hint of triumph in her gait. She turned and added almost apologetically, “It’ll help you get to know the students.”

Huh?

To add insult to injury, when I finally got my class schedule and wanted to know where my classroom was, I was told I had to go to the students.

I then walked helplessly around the school searching for my students’ classroom. When the search was to no avail, I spoke to a supervisor to ask for help. I thought maybe she knew where the students’ classroom was.

“What?” she said indignantly. Her eyes scolded me. She raised her voice when she said, “You didn’t tell the students where to meet you?”

What? I didn’t even know who these students were.

My confusion must have shown on my face because she then said, an air of boredom and frustration in her now lowered voice, “You must find an empty classroom and tell the students to meet you there.”

That was a task to say the least.

First I had to find a group of girls who (rumor was) were somewhere in this massive building. (That should narrow it down). But I could use a teensy bit of help, a small hint perhaps…?

The supervisor regarded me as if I’d just asked her the first letter of the English alphabet. (I sensed I wasn’t making such a good impression as that “hot shot” English teacher delivered fresh from the States.) “Look at their class schedule to find out where they are now!”

Duh!

Now, that was a no-brainer. …But…um…

I just assumed it was a small oversight that I wasn’t given their schedule.

One glance at the woman’s face told me I shouldn’t ask my next question….

But I couldn’t help myself. I just had to know where I might get my hands on this coveted student schedule of theirs…

“It’s posted outside their homeroom!”

Hmm… Yes, common sense, of course.

But… um…

Where was their homeroom?

I glanced hesitantly at the supervisor…and decided against asking.

“Right,” I said, smiling as brightly as I could. I had to at least pretend that my intelligence quotient met the minimum of that of a teacher.

But my thoughts were frantic.

Where would I find a classroom after I found their homeroom then looked at their schedule to find the classroom they’re in now so I could tell them to go to that classroom I found where I would teach them? (I never bothered wondering why they had to leave that particular room in the first place.)

“If no other teacher is using a room,” the supervisor said finally, “you can use it.”

Right…

Not wanting to waste more time, I disappeared into the hall to start “the hunt.”

Finally, my speed walks and quick peeps into classrooms (“So so sorry,” I’d say when I found my eyes meeting that of an annoyed teacher interrupted midsentence as the door opened and I peered inside) led me to a genuinely empty room. Then I whizzed back to the students (whom I’d miraculously found…their identification made quite easy by clusters of them wandering aimlessly through the halls because of an assumed “free lesson”) and told them which classroom to go to (after introducing myself quickly, of course). I also instructed them to get their books and line up outside the designated room to wait for me. (In the meantime, I had to “capture” a few hallway stragglers who were pretending they were not part of this class).

As I arrived trailing behind a line of about 25 seventh-grade girls, another supervisor was waiting for me outside the classroom I’d found.

She snarled at me. “Why are you late to class! These girls should not be hanging in the halls.”

Deep breath. Now… exhale…

There is no place like home. There is no place like home. There is no place like home…

“And where are the exams?” she demanded as if I’d stolen something.

“Right here.” I gestured my chin toward to an envelope cradled in my arms.

“You are not allowed to carry the exams around. You are to return them to the section supervisor immediately after marking them!”

“Well…um…I had a class.”

Silence.

She began studying me as if I were an exhibit in a foreign museum.

“You’re new, aren’t you?” she said. She was speaking more to herself than to me, and she frowned momentarily as I handed over the bulky manila envelope that was tearing at the sides due to the excessive amount of exams jammed inside.

I just blinked back at her.

There was pity in her eyes. Not sympathy. Pity.

I’d wasted her time.

She sighed before walking away…

…

Later, in the staffroom, I had a plan, an epiphany actually. I would organize the disorganization!

So throughout the day I took notes on all the empty classrooms I’d found and the classes I’d had in them, being sure to memorize their locations by using hallway landmarks such as students’ art projects and colorful banners.

…

Then, that night, in the comfort of my home, I sat before my computer feeling energized as my hands were poised on the keyboard ready to type. I felt as if I were accomplishing “mission impossible.”

Inspired that I’d actually found a method to the madness, I sifted through my papers of hurried pen strokes and scribbled notes. On the computer program, I made a table. I divided it into rows and columns before typing in the info I’d gathered. I then used the gray shading to indicate my “teacher planning periods” (which I’d later learn were really “substitute for whoever’s absent” periods) and the school’s assigned breaks.

After about an hour of mental wrestling, formatting and typing, and re-formatting, it was done.

Ah! The joys of… a piece of paper.

I printed out the schedule and felt a sense of satisfaction when I went to sleep that night.

In the morning, I cheerily arrived to school and hung the printed paper on the side of my desk. (Too many desks cluttered together didn’t allow much chance for hanging anything on a wall).

When it was time for class, I gathered my books and double-checked my neatly organized printout before proceeding to my lesson.

…Only to discover that my designated classrooms were now being used by other teachers.

“But it was vacant yesterday,” I said as diplomatically as I could to the occupant of my room.

The veteran teacher smiled, amused. “Yes, but they have my class twice a week. I always use this room on this day.”

My heart sank.

This could not be happening…again.

And so…

I was speed walking and peeping into classrooms. (“So so sorry,” I’d say when I found my eyes meeting that of another annoyed teacher interrupted midsentence as the door opened and I peered inside). …Then after finding an empty room, I whizzed back to the grumbling students and told them to gather their books and line up outside the classroom I’d found.

Whew! I exhaled at the end of the day.

But I wasn’t totally defeated. All wasn’t so bad.

No, I couldn’t use my fancy “empty classroom” map of mental landmarks complete with colorful student art and banners. But I could use that fancy schedule of my classes I’d printed out and posted on my desk in the staffroom.

…Until I was informed that my schedule was changed.

I wasn’t smiling when the teachers near me snickered.

One kind soul had the presence of mind to give me a genuine, sympathetic smile.

And her kind eyes said what I could laugh about only later…

Welcome to Saudi, ukhti. This is your new home. And there’s no place like it in the world.

Trust me.

Umm Zakiyyah is the internationally acclaimed author of twenty books, including the If I Should Speak trilogy, Muslim Girl , and His Other Wife . Join UZ University to learn how you too can find your writing voice and share inspirational stories with the world: UZuniversity.com

Subscribe to Umm Zakiyyah’s YouTube channel , follow her on Instagram or Twitter , and join her Facebook page.

Copyright © 2011, 2018 by Al-Walaa Publications. All Rights Reserved.

First published via saudilife.net

The post No Place Like Home: American Teacher in Saudi appeared first on Umm Zakiyyah | Author Writer Speaker.

June 1, 2018

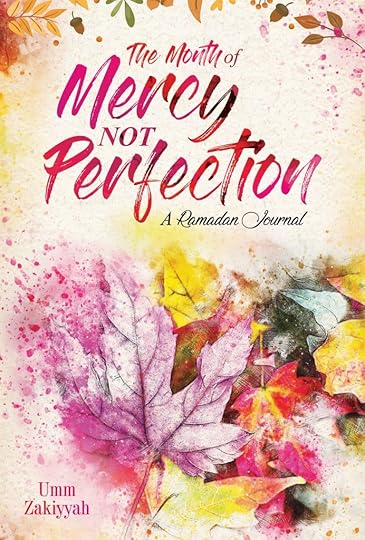

Reality of Ramadan: You Might Not Benefit

“Ramadan is the month of mercy, not the month of perfection. You’ll still make mistakes, and you’ll still fall short at times. But Allah’s mercy remains. Seek it, and don’t give up.”

—from the journal of Umm Zakiyyah

The following is an excerpt from the book And Then I Gave Up: Essays About Faith and Spiritual Crisis in Islam by Umm Zakiyyah:

I returned to my dormitory room after a full day of classes—and fasting. I was exhausted. Outside was dark, and my stomach grumbled. I had eaten only a little at iftaar because I had been so busy with schoolwork and meetings.

As I settled at my desk with a bagel and some grapes, I glanced at the clock. It was almost time for Ishaa. Already, I felt dread knotting in my chest. I could barely keep up with praying my five prayers on time; how would I pray Tarawih…alone?

I drew in a deep breath and exhaled, in that moment mentally scolding myself for my doubts. I will pray Tarawih every night this Ramadan, I told myself, no matter what.

An hour later I was facing the Qiblah as I completed my first two units of Tarawih. Heaviness weighed on my limbs and my mind wandered. How many more to go? I asked myself in irritation.

I mentally blocked out the question and moved on to the next set of prayers…and the next…and the next.

When I finished I almost collapsed in relief.

I was finally done. I met the warmth of my bed feeling as if a weight had been lifted from my shoulders…

And an even weightier load put in its place.

That was the last time I prayed Tarawih that Ramadan.

“Whoever observed prayer at night during Ramadan because of faith and seeking his reward from Allah, his previous sins will be forgiven” (Muslim).

It took a series of repeated spiritual failures like the one I experienced as a first-year American college student before I finally faced the painful reality I had been avoiding for so long: Ramadan just wasn’t what it used to be.

My parents had become Muslim the year I was born, so all the years preceding my living alone for the first time were filled with Islam in the house.

As a child I fasted the long summer days along with my older siblings and my parents. I enjoyed the burst of pride I felt upon waking early in the morning and breaking fast at the end of the day. I felt like such a “grownup” savoring the sweetness of dates and cold water, and praying shoulder-to-shoulder next to my big sisters. I also felt a sense of purpose sitting down and reading a thirtieth of the English Qur’an and reflecting on its verses. And I was unable to contain my sense of accomplishment upon finishing the entire book at the end of the month.

Although as a child fasting was not always easy (especially during the summer when the sun set close to nine o’clock at night), I recall Ramadan being such a tranquil month, and I was often in awe at the spirituality I felt emanating from within.

As I worshipped Allah, at moments I really felt a sense of camaraderie with the rest of the world—the sun rising each morning, the stillness of the grass outside, and the smiling faces of believers…

To me, Ramadan had always been…

Miraculous…

Until it wasn’t anymore.

RAMADAN JOURNAL Sample Page. CLICK HERE

One day the Messenger of Allah, sallallaahu’alayhi wa sallam, ascended the mimbar and said: “Ameen. Ameen. Ameen.” The Companions asked, “O Messenger of Allah, why did you do that?”

He said, “[The Angel] Jibreel said to me, ‘May Allah rub his nose in the dust—the person to whom Ramadan comes and his sins are not forgiven,’ and I said, ‘Ameen’…” (Ibn Khuzaymah -1888; Tirmidhi- 3545; Ahmad -7444).

When I first heard this hadith, I shuddered.

Was it that my loss of tranquility in Ramadan was due to my being amongst those about whom the angel spoke in this hadith?

…I didn’t want to think about it.

It has been more than fifteen years since I spent my first Ramadan away from home. And although I’ve been blessed with many a tranquil Ramadan thereafter—filled with nights standing in Tarawih and crying to Allah—I don’t think I’ve ever recovered from the spiritual loss I suffered that year.

Even now as Ramadan has arrived and I have a family of my own, I feel my chest constrict and tears of apprehension fill my eyes…

“When the month of Ramadan starts, the gates of Paradise are opened and the gates of Hell are closed, and the devils are chained” (Bukhari).

Will I suffer like I did before?

Will I turn from the gates of Paradise, shutting my eyes to my faults and sins?

Will I stand eagerly—and patiently—at the gates of Hell…

Awaiting the Blessed Month to end?

…I shiver at that thought.

“O Allah! Protect me from myself!” I pray.

Ramadan is the most feared and eagerly awaited month of the year, I wrote in my diary a few years ago.

And for me, it is.

…Because now I know all too well that there is nothing “miraculous” about the Month of Mercy.

There is no tranquility that will fall into your lap. There is no spirituality that will settle over you while you sit idle…

Only those who want Ramadan’s blessings will receive them. Only those who want Allah’s forgiveness will be granted it.

And only those who want Paradise will enter it.

And for me, that is the most terrifying—and welcomed—reality of all…

That it is possible for any human—whose death is the only imminent certainty of life—to actually live a single day on this earth, or an entire month of Ramadan, without benefiting from it…

And that it is possible for any human—who sincerely turns to Allah before that moment of certainty—to be granted forgiveness greater than his faith and deeds deserve.

And Allah offers us both in this Blessed Month.

Which will you choose?

READ FULL BOOK: And Then I Gave Up: Essays About Faith and Spiritual Crisis in Islam [CLICK HERE]

Essay originally published via saudilife.net

Umm Zakiyyah is the internationally acclaimed author of twenty books, including the If I Should Speak trilogy, Muslim Girl , and His Other Wife . Join UZ University to learn how you too can find your writing voice and share inspirational stories with the world: UZuniversity.com

Subscribe to Umm Zakiyyah’s YouTube channel , follow her on Instagram or Twitter , and join her Facebook page.

Copyright © 2010, 2018 by Al-Walaa Publications. All Rights Reserved.

The post Reality of Ramadan: You Might Not Benefit appeared first on Umm Zakiyyah | Author Writer Speaker.

May 29, 2018

Maybe It’s Divorce We’re Taking Lightly

“Marriage is not the end of the rainbow, and divorce is not the end of the world.”

—from the journal of Umm Zakiyyah

The following is an excerpt from the book Let’s Talk About Sex and Muslim Love by Umm Zakiyyah:

“This is really a shame,” the woman said. “The divorce rate of Muslims is so high. Why are Muslims taking marriage so lightly?”

It’s a question we’ve likely all heard or uttered by our own tongues. But the more I live, the more I’m developing a different perspective…

Anisa’s Story

Anisa was twenty-two when she got married, but she was sixteen when she met eighteen-year-old Samir. They met in Honor Society and were drawn to each other, the only practicing Muslims at school. Anisa wore hijab, and Samir spoke openly about Islam. Though they shared no classes, they saw each other during the club’s weekly meetings after school.

Neither Anisa nor Samir thought much of their frequent talking. But there was so much to discuss and so much that drew them together. They shared the same goals in life, and they both dreamed of teaching Islam on a large scale.

When Samir graduated, Anisa couldn’t escape the sense of sadness that overwhelmed her, but she tried to focus on school. She kept telling herself it was just loneliness. But something deep inside said it was something more…

It was a year before Anisa and Samir got back in touch. Anisa was browsing a friend’s Facebook page when she saw Samir’s profile. Her heart pounded in excitement, and her hand trembled nervously as she sent him a friend request. Less than an hour later, he accepted, and it was clear that Samir was excited to hear from her.

They talked online almost every day after that. But they still didn’t admit to themselves what was happening. But when Anisa gave Samir her phone number and told him the times to call (when her parents weren’t home), she started to feel a little guilty. But they talked mostly about Islam and what they envisioned for themselves in the future…and in marriage.

Anisa was eighteen and months away from graduation when Samir surprised her by visiting the school. It was time for Honor Society, but when she saw Samir, she couldn’t bring herself to go inside.

“I had to see you,” he said as they walked down the hall. They both kept their hands tucked deep into their pockets, but they couldn’t avoid the furtive glance. “I miss you, Anisa.”

The words sent Anisa’s heart fluttering, and she barely found her voice. “Me too.” When she realized that her response made no sense, they both laughed awkwardly.

They were sitting on the bleachers outside when Samir said, “I know it’s wrong to have these feelings…” Anisa averted her gaze, her face growing warm in embarrassment. “But I can’t take this anymore. I need to be with you…properly, you know?”

“No,” Anisa’s mother said later that night when Anisa confided in her about Samir. “You are too young. Besides, he’s not from our country. It can never work. I’ll mention none of this nonsense to your father. Stupid girl, don’t go and ruin your life for some boy.”

“I’m not giving up,” Samir said on the phone the next day, but his voice betrayed how heartbroken he was. “I’m talking to your father.”

“Stay away from my daughter!” A week later, Anisa shuddered as her father’s voice carried to the solitude of her room. She heard the front door slam, and she rushed to the window, her heart dropping as she saw Samir walking to his car, shoulders slouched.

“I’m not giving up,” Anisa told Samir on the phone the next day.

“I wish we could run away together,” Samir said, a hint of humor in his sad tone. They both laughed, but when Anisa hung up the phone, tears stung her eyes.

When Anisa was twenty-one years old and in her third year in university, her parents said they had found a “good boy” for her.

“You will not refuse Abdullah,” her mother said the night before Anisa was to meet him. “Your father worked very hard to find the right match for you. Abdullah finished medical school and comes from a good family. Do not disappoint us.”

Samir met Anisa on campus after she told him the news. Anisa cried unabashedly as Samir fought back tears, but he couldn’t keep himself from pulling Anisa close to him. Islamic limits blurred at that moment, and neither cared. They just wanted this moment, which they would never have again.

Naturally, Anisa’s marriage to Abdullah was strained from the start. Her heart was attached to Samir, and no matter how hard she tried, she could not loosen the hold Samir had on her heart. But she convinced herself that her mother was right. A good Muslim girl did what her parents wanted, even if it wasn’t what she wanted for herself.

“We are good Muslims, Anisa,” her mother had said after Anisa and Abdullah met. “We are not forcing you. Allah forbids this. But if you do not marry Abdullah, know you are breaking your parents’ hearts, and I will never forgive you for that.”

Abdullah was a good man, Anisa could not deny. He provided for her and spent quality time, but he did not share Anisa’s love for Islam or her outlook on life. Even though they didn’t have children, Abdullah asked her to drop out of graduate school and focus on her “Islamic duties.” He said a good Muslim woman doesn’t mix with men—even though his job at the hospital required just that, as did his casual friendships with female coworkers.

When Abdullah suggested Anisa remove her hijab, she was aghast. She cried to her mother, and to Anisa’s shock, her mother told her to obey her husband. “We are living in difficult times,” her mother said. “There’s no point in putting hardship on yourself.”

Anisa felt uncomfortable when she walked outside uncovered for the first time, and she could never bring herself to accept this new life. She became so ashamed of herself that she stopped reading Qur’an and she barely prayed. Ultimately, Anisa fell into deep depression and fought thoughts of suicide.

On one particularly distressful day, Anisa took a walk. As the sun warmed her hair and bare arms, Anisa reflected on her life, and she found that she didn’t even know herself anymore.

“Anisa?”

Anisa’s private thoughts were disrupted, and she looked up to find Samir opposite her…and a beautiful woman in hijab with a baby stroller.

Shocked and ashamed, everything came back to her in that moment. She felt angry with herself, her parents, and even Abdullah. But she would get her life back, she told herself, even if it meant divorce…

The Reality of Divorce

Like the fictional character Anisa, most people who reach the point of divorce have a long history of practical and psychological struggles that led them to that point. These men and women do not fantasize about divorce, and they do not take marriage lightly.

“The decision to divorce is never easy, and as anyone who has been through it will tell you, this wrenching, painful experience can leave scars on adults as well as children for years.” For Muslims this decision is all the more difficult because they have to consider the repercussions in this world and in the Hereafter.

Is Divorce As Bad As We Think?

Though it is unquestionable that preserving a marriage is of great importance in Islam, the stigma attached to divorce and the vow “till death do us part” are not Islamic concepts.

Allah says,

“…No person shall have a burden laid on him greater than he can bear.” —Al-Baqarah (2:233)

In the chapter Al-Talaaq (Divorce), Allah says,

“…And whoever fears Allah and keeps his duty to Him, He will make a way out for him [from every difficulty]. And He will provide him from [sources] he never could imagine. And whosoever puts his trust in Allah, then He will suffice him.” —65:2-3

Therefore, it is imperative that we not place impossible restrictions on ourselves. Whether a believer is married or divorced, Allah’s mercy, love, and provision are always near.

Another Point of View

When we look at divorce honestly, we often find that amongst Muslims, it is not always the one seeking divorce who is taking marriage lightly. It is sometimes the parents and families who compel the Anisas and Abdullahs of the world into marrying for the sake of tradition or image—or parents and families whose complete lack of involvement leave youth without guidance when embarking on this life-altering milestone.

Naturally, whether the marriage is “forced” or decided without proper guidance, it is likely only a matter of time before divorce is sought as a last resort to restore psychological or spiritual peace. And when these men and women raise their hands to Allah and ask for relief, who are we to say they’re discounting the heavy responsibility of marriage? Divorce at such times may be a tremendous blessing for them.

And we should not take this lightly.

READ FULL BOOK: Let’s Talk About Sex and Muslim Love [CLICK HERE]

This essay was first published via onislam.net

Umm Zakiyyah is the internationally acclaimed author of twenty books, including the If I Should Speak trilogy, Muslim Girl , and His Other Wife . Join UZ University to learn how you too can find your writing voice and share inspirational stories with the world: UZuniversity.com

Subscribe to Umm Zakiyyah’s YouTube channel , follow her on Instagram or Twitter , and join her Facebook page.

Copyright © 2016, 2018 by Al-Walaa Publications. All Rights Reserved.

“Divorce: The Most Difficult Decision You Will Ever Make.” Excerpted from The Complete Idiot’s Guide to Surviving Divorce. BookEnds, LLC. Cited October 23, 2012 on http://life.familyeducation.com/divorce/divorce-counseling/45515.html

The post Maybe It’s Divorce We’re Taking Lightly appeared first on Umm Zakiyyah | Author Writer Speaker.

May 28, 2018

She Couldn’t Have Sex with Her Husband: Modesty Gone Too Far

She was taught that sex was dirty and shameful, so she was never allowed to talk about it. In her family and culture, this thinking was considered the highest form of modesty. But unfortunately, this “modesty” led her to have so much anxiety about sex and nudity that she didn’t even feel relaxed enough to let her own husband touch her. In fact, she’d developed a condition called “vaginismus” in which her body literally closed up, preventing any penetration. So even after she got married, she was unable to have sex with her husband for more than one and a half years. Read some of her story below.

The following is an excerpt from the book Let’s Talk About Sex and Muslim Love by Umm Zakiyyah:

In this interview, Tasniya, a young Muslim woman, discusses how vaginismus prevented her and her husband from having sex. She says:

When I got married and I wasn’t able to consummate my marriage, I was very confused. I went to several counselors, Imams, and gynecologists but no one really understood me. I felt isolated and depressed because I thought I was the ‘only one’ going through this. For example, my gynecologist gave me an exercise to do: she told me to buy the smallest tampon in the store, put lube on it, and try to insert it into my vagina. It was a nightmare for me! I just couldn’t do it and I felt like a failure every single time. Therefore, at one point, I seriously considered leaving my husband because I felt as though I was being unfair to him and he deserved better. Feelings of shame and guilt overwhelmed to the point where I was really having difficulties living a normal life. Insha’Allah [God-willing], my husband and I want to start a family some day and I thought that I could never do such a thing because I couldn’t even have intercourse!

Alhamdulillah, after making du’aa [prayerful supplication] to Allah (SWT) and doing some research, I came across the clinic in NY [New York]. I realized my condition actually has a name and I’m not some sort of weirdo because there are others out there just like me! Then, I realized that if I am a Muslim woman who was suffering silently, I am sure there are other Muslim women who are also suffering silently. This is a taboo topic to talk about and no one likes to admit that they can’t have intercourse (especially after marriage). That is when I decided that I have to spread awareness about this so I can help the ummah. I want our ummah to know that there is a cure and vaginismus can be a thing of the past insha’Allah!

What are some of the causes of vaginismus?

According to Ditza Katz and Ross Lynn Tabisel, authors of Private Pain: It’s About Life, Not Just Sex, some causes are:

Being worried about the fragility of the vagina

Fear of pain

Religious inhibitions and taboos

Cultural variations

Parental or peer misrepresentation of sex and sexuality

The inability to say No to an unwanted sexual situation. [This] causes the feeling of being forced, of being option-less, of the need for self-protection, and thus vaginismus

Childhood sexual abuse

Parental indulgence and over-protectiveness

What are some of your memories as a child and young adult that you feel are significant in shaping how you felt about your body, specifically as a female?

I always felt uncomfortable in my body. I have low self esteem and body image issues. I was always under the impression that things like the period or menses are a dirty thing. I would always be ashamed of my pad leaking, which I believe contributed me to ultimately be ashamed and disgusted by my vagina. Because I didn’t realize that menses are a normal part of the life, it became something that was unnatural to me.

I also associated pain, shame, and disgust with things like intercourse. I don’t think I was ever taught that intercourse is a pleasurable thing for the husband and wife. No one ever told me that intercourse is pleasurable in the eyes of Allah (SWT) when it is done in the confines of marriage. Therefore, mentally I conjured up this negative image of intercourse and associated pain and disgust with it, which ultimately led me to having vaginismus.

When you reached puberty, did you know what was happening? If so, what did you know about this physical change? If not, why not?

When I reached puberty, I had no idea what was going on with my body. The first time I had my period was a traumatic experience. I thought I had cancer and I was afraid to tell my parents because I didn’t know what they would think. Finally my mom saw me crying and I told her what had happened. She gave me a pad but I never really understood what was going on and why I was having my period all of a sudden. Therefore, this lack of understanding of what truly happened in my body could have resulted in having vaginismus.

As a teen and young adult, how did you feel about your natural feelings toward the opposite sex? Did you talk to anyone about these feelings? If not, why not? If so, who, and how was the topic addressed?

I always felt ashamed of having feelings toward the opposite sex. In my mind, I thought I was sinning and God would punish me for having these feelings. I would try to contain them but I couldn’t. I would talk to my friends about these topics but that’s about it. We were all going through the same thing and we really didn’t understand what was going on. I would enjoy talking about boys with them but afterwards I’d feel guilty because I thought I would go to Hell for even talking about such things.

Do you recall feeling confused or frustrated as a child or young adult regarding any “taboo” subjects? Please explain.

I always felt upset when I couldn’t openly ask or speak about certain topics with my family members. I remember an aunty of the family once telling my mom how ‘advanced’ children have become these days because they know so much about topics like intercourse and sex. She remarked how back in the day children were so innocent and because they didn’t know what intercourse or sex was until they got married. It almost seemed that because children are learning about these topics at an early age, they are somehow “messed up”. So it would often frustrate me because I felt like those aunties were talking about me. I learned a lot about sex from my classmates and health classes in school. However, I didn’t think I was a “messed up” child for knowing these things. It almost seemed that being ignorant about the world was a sign of purity and being knowledgeable was a sign of impurity. It just didn’t feel right and I felt very conflicted.

When did you first discover you had vaginismus? How did you know there was a problem? What happened?

Before marriage, I had a gut feeling that something would go wrong. Every time I would think of having intercourse, I felt nervous or afraid. However, I thought all girls felt that way because it is something new for them. I first discovered I had vaginismus after I got married. I couldn’t consummate my marriage so I knew something was wrong. We would try for hours and hours to have intercourse but I just couldn’t. I would start panicking and crying in bed. I was so afraid to open my legs up even when my husband would try to. If he tried to touch my vagina or anywhere near that area, I would move his hands away and push him.

When he tried to enter me, it literally felt like he was hitting a brick wall. I started to think something was wrong with me anatomically and maybe I didn’t have a hole or something. It was frustrating and I knew something was wrong. I just didn’t know exactly what it was and the traditional doctors or gynecologists did not know either.

Another experience that confirmed that something was wrong with me was when I went to have my first gynecological exam. It was a nightmare. I was freaking out and my heart was racing. When the gynecologist came to do my pap smear, I was so terrified. I was not about to let her put that instrument inside me. It looked so big and scary! She tried to put her small finger inside me and the pain was excruciating. I started crying and I told her I did not want to go through with the exam. So my husband and I left. I was so embarrassed. I felt like I failed him. I failed us. Again, I had no idea what was wrong with me but there was something wrong indeed.

READ FULL BOOK: Let’s Talk About Sex and Muslim Love [CLICK HERE]

Umm Zakiyyah is the internationally acclaimed author of twenty books, including the If I Should Speak trilogy, Muslim Girl , and His Other Wife . Join UZ University to learn how you too can find your writing voice and share inspirational stories with the world: UZuniversity.com

Subscribe to Umm Zakiyyah’s YouTube channel , follow her on Instagram or Twitter , and join her Facebook page.

Copyright © 2016, 2018 by Al-Walaa Publications. All Rights Reserved.

The post She Couldn’t Have Sex with Her Husband: Modesty Gone Too Far appeared first on Umm Zakiyyah | Author Writer Speaker.

Nobody Cares About Black Muslims, He Said

alone.

it hurts.

I cannot lie

to be abandoned

by those who look like me

because I see the other as brethren too

and then

to be abandoned

by the other

my brethren

in faith.

because I look like me

The following is an excerpt from the book Prejudice Bones in My Body by Umm Zakiyyah:

The first time I remember not feeling loved—I mean really not feeling loved—was at college, when the school disparaged me because I was Black. And Muslims showed their eager support.

I wrote this in my journal because alone at home with a pen and paper is one of the few places I feel safe enough to be honest about my pain. The other places are when I am alone with Allah, when I am alone with those I love, and those whom I trust love me.

But recently I’ve been taking a few risks, sharing my heart in ways I never have before. It started, I think, with the decision to speak about feeling like I could no longer be Muslim, in the video I Never Thought It Would Be Me. That was a scary first step, but it was a necessary one because I felt trapped in my confusion and pain, and trapped in a life others had carved out for me. Then the words flowed a bit more easily, even if hesitantly, in Pain. From the Journal of Umm Zakiyyah, then Broken yet Faithful, and now Faith.

But it’s still hard, and I often cringe in knowing I’ve shown so much of myself. But today, for the sake of my emotional health and spiritual sanity, I feel I have no other choice.

The truth is, the most difficult part of the battle to be seen as human is the one waged against oneself. I was taught that I didn’t have the right to exist, and I’d believed it. Though no one used those exact words, it was instilled in me nonetheless. In circles of those who looked like me, I was taught that my existence had to be sacrificed for “the greater good,” for a Black legacy that was bigger than me. I was taught that internal hurts—those inflicted upon me by those who looked like me—had to be kept quiet because the admission would be seen by “them” as an opportunity to inflict more hurt.

But in my eyes, “they” inflicted hurt because of their own internal pain and spiritual depravity, not because I admitted to having pain of my own. Yes, “they” would use any opportunity to say I deserved to hurt, and I certainly didn’t want to give them more power over me than they already had.

But the problem is, this hiding of hurts (and thus giving oneself no opportunity for healing) is itself a grave hurt and a form of oppression, incited by a culture of systematic racism. It is the existence of racism that tells us that we do not exist like others do.

Besides, isn’t it the very definition of being human to have within you, individually and collectively, both good and evil? And is there any group of people who escape this part of human experience? What then, I wondered, was the point of denying my right to be seen as human too?

Equal Opportunity Evil

Here’s the problem with buying into bigoted untruths of the self and others: evil doesn’t discriminate. Shaytaan, as well as his army, views all human hearts the same: as opportunities for corruption and dragging them alongside him to Hellfire. He doesn’t care about the amount of melanin (or lack thereof) in the skin of human beings, the descendants of the one toward whom he felt destructive, envious pride. Ironically, Shaytaan sees us as we should see ourselves: as a single people, a single group, a single family of Adam.

When we, whoever we are, begin to believe evil has escaped us more than it has escaped others, or that good has come to us more than it has come to others, then we have joined Shaytaan and his army, and thus have given our hearts over to the same prideful disease that destroyed Iblis.

Black in the MSA (Muslim Student Association)

When I was in college, I was very active in the MSA. Ultimately, I served as vice president one year and president another. During my four years in undergrad, I was often the only Black Muslim who participated consistently. But it was a fellow BSU (Black Student Union) member who approached me after class one day and asked if I would come to a speech by a man who had been part of the administration of former U.S. President Ronald Reagan. She showed me some of the man’s writings, and I was appalled. It listed in unapologetic horrid detail “scientific proofs” of the biological inferiority and pathology of Black people. In other words, it detailed how Black people, allegedly, had not fully evolved from apes and thus had underdeveloped intelligence and “inherently” violent and immoral ways.

I sat in the audience listening in shock to a speech by a man brought to the university on school funds. My only consolation was that we, the Black students, had come in groups, prepared to challenge him during Q&A. When I glanced around the audience, I was pleasantly surprised to see some members of the MSA in attendance. Like myself and the Black students, they were different shades of brown sitting amidst the predominately White audience though the MSA members were mostly Desi, from India and Pakistan.

When the speaker made a joke disparaging a Black student, I saw the reaction of some MSA members, and I did a double take. The MSA group was laughing and clapping. When the speaker spoke of Blacks and Latinos being inherently ignorant and mentally diseased and Whites and Asians being inherently intelligent and superior, the Desi Muslims roared in applause. When he spoke of the inherent inferiority of Black people, they nodded in agreement as their eyes lit up in an eager admiration that I associated with someone being in the presence of a beloved celebrity.

A Wake-up Call

I could say I shouldn’t have been surprised, given that the speaker himself was originally from India. But that wouldn’t be true, and it wouldn’t be right. I was surprised, and I should have been. Why should I, or any believer, expect anything less than basic human decency from fellow believers in Allah?

But it hurt. I cannot deny that. These were the same Muslims who sat opposite me, an administrator of the MSA, to brainstorm events to bring together Muslims on campus. No wonder I was the only Black person who participated regularly. I was the only one who hadn’t gotten the memo. But since I’d been voted in as an administrator myself, in the eyes of the MSA, I had no right or claim to my pain. After all, how could they be racist when they voted in a Black board member?

So I went home that day and said nothing about what I’d seen or heard. As far as I could tell, the Desi MSA members hadn’t seen me in the crowd, so after the event, I found my way out of the room and carried my heavy heart alone.

Nobody Cares About You

“Nobody cares about Black Muslims except Black Muslims,” an MSA member said to me months later when I suggested an event aimed at explaining the differences between the Nation of Islam and orthodox Islam. This member was Arab, and I’m sure, like the Muslim supporters at the racist speech, he meant no harm. “Good people” never do.

But they somehow manage to continually inflict it. And because they don’t mean to, our job is to suffer in silence, continuously. Because apparently, the only crime greater than good people inflicting pain is for hurt people to openly acknowledge that they hurt.

This is particularly the case if those hurt people are members of a group unapproved for full human existence. If you’re of a privileged group, you can speak of the hurt you felt when the people you hurt didn’t praise you enthusiastically enough for not hurting as much as they could.

Being Black and Muslim

I don’t like sounding like a victim because I am not. I am a hurting human being. But because I am not viewed as a full human being, when I speak of hurt, it is allegedly because I see myself as a victim. When others speak of hurt, it is because they see themselves as a human who is hurting.

Being Black and Muslim is not a victim experience. It is a human experience, and it is my human experience. And it hurts. And it’s not because I bemoan either gift (Blackness or Islam) that God has given me. It is because the suffering inflicted on me by my brothers and sisters in both humanity and faith due to their dislike of the melanin God has given me.

I don’t pretend to understand the fight that people are picking with God when they speak so condescendingly about the black and brown-hued creations of God. But I myself feel grateful for the gift of brown skin that my Lord has given me. If nothing else, it at least offers me that much more protection from destructive human pride.

Also, as I experience daily mistreatment from both fellow Americans and fellow Muslims, I am given the priceless reminder that this earth is not my home.

READ FULL BOOK: Prejudice Bones in My Body [CLICK HERE]

Umm Zakiyyah is the internationally acclaimed author of twenty books, including the If I Should Speak trilogy, Muslim Girl , and His Other Wife . Join UZ University to learn how you too can find your writing voice and share inspirational stories with the world: UZuniversity.com

Subscribe to Umm Zakiyyah’s YouTube channel , follow her on Instagram or Twitter , and join her Facebook page.

Copyright © 2016, 2017, 2018 by Al-Walaa Publications. All Rights Reserved.

Originally published via muslimmatters.org

The post Nobody Cares About Black Muslims, He Said appeared first on Umm Zakiyyah | Author Writer Speaker.

May 25, 2018

Yesterday, I Cried

The following is an excerpt from the book And Then I Gave Up: Essays About Faith and Spiritual Crisis in Islam by Umm Zakiyyah:

Author’s Note: This was written when I lived in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, and taught English at an international school.

It was one of those moments when you feel the tugging at your heart and the moisture behind your lids before you decide whether or not you want to…

The day started off as normally as one could hope. It was the weekend, a Friday, and I needed to run by a friend’s house to pick up some books I needed for school.

Weekends are usually a stress relief for me, time to take a deep breath and exhale slowly. And I wouldn’t have to hold my breath again until Saturday morning, when I’d return to work.

Before I go on, I think I should say that I’m a teacher—of high school girls. Anyone who’s had the wondrous experience of working full time in a classroom full of “kids” knows the endless rewards of imparting knowledge on the next generation. And the endless heartache of having them impart stress on you.

I’m no exception.

So I was having one of “those days” (If you’re a teacher, you know what I mean), when you wonder, What’s the point? I mean, the world is going in a drastically different direction than I’d ever imagined. And the kids aren’t too excited about an “old” woman standing in front of them, telling them that they should pray Salaah on time, wear hijab, and be “good Muslims.”

Ho hum… Yes, I know. But what else can I tell them? “Which movie star couple do you think might accept Islam together”?[image error]

Anyway, I was stressed, to the point of heartache. I’d heard yet another story of a Muslim girl I’d once taught who was living a life wholly disconnected from Islam, and was sharing it with the world on Facebook. Sadly, today these stories seem endless. Someone’s at the mall meeting up with boys. Someone’s throwing his number into cars. Someone’s stopped saying their prayers…

I arrived at my friend’s house with a heavy heart, and was, as usual, wondering where my place was in all of this. After all, I have my own faults and my own soul to fend for. But still… There had to be something I could do. We’re all in this together, right? We’re here to help each other. You remind me; I remind you. That’s what it means to be Muslim. At least that’s what I’d been taught.

Who do you think you are? What gives you the right to tell others what to do? You need to mind your own business. You just think you’re better than everyone else. You’re so judgmental… These are just a few of the responses to seeking to help each other that believers hear each day. And it hurts. Oh, how it hurts.

I don’t know about anyone else, but I find these words so painful because not only do I not think I’m better than others: I know I’m not better than others, yet I still have the obligation to command the good and forbid the evil. And that’s no easy burden to bear.

In the end, I imagine that’s why believers like the Companions, who were able to command the good and forbid the evil without ever giving up—even as they had faults of their own—are so highly praised in Islam. Allah says of them, “You are the best people evolved for mankind. You command the good and forbid the evil, and believe in Allah” (3:110).