Nicholas C. Zakas's Blog, page 8

January 21, 2014

Private instance members with weakmaps in JavaScript

Last week I came across an article[1] by Nick Fitzgerald in which he described an approach for creating private instance members for JavaScript types using ECMAScript 6 weakmaps. To be completely honest, I’ve never been a big proponent of weakmaps – I thought there was a loss of fuss about nothing and that there was only one use case for them (tracking data related to DOM elements). I was still clinging tight to that belief up until the point that I read Nick’s article, at which point my weakmap belief system blew up. I now see the possibilities that weakmaps bring to JavaScript and how they will changes our coding practices in ways we probably can’t fully imagine yet. Except for the one that Nick mentioned, which is the focus of this post.

The legacy of private members

One of the biggest downsides of JavaScript is the inability to create truly private instance members on custom types. The only good way is to create private variables inside of a constructor and create privileged methods that access them, such as:

function Person(name) {

this.getName = function() {

return name;

};

}

In this example, the getName() method uses the name argument (effectively a local variable) to return the name of the person without ever exposing name as a property. This approach is okay but highly inefficient if you have a large number Person instances because each must carry its own copy of getName() rather than sharing a method on the prototype.

You could, alternately, choose to make members private by convention, as many do by prefixing the member name with an underscore. The underscore isn’t magic, it doesn’t prevent anyone from using the member, but rather serves as a reminder that something shouldn’t be used. For example:

function Person(name) {

this._name = name;

}

Person.prototype.getName = function() {

return this._name;

};

The pattern here is more efficient because each instance will use the same method on the prototype. That method then accesses this._name, which is also accessible outside of the object, but we all just agree not to do that. This isn’t an ideal solution but it’s the one a lot of developers rely on for some measure of protection.

There’s also the case of shared members across instances, which is easy to create using an immediately-invoked function expression (IIFE) that contains a constructor. For example:

var Person = (function() {

var sharedName;

function Person(name) {

sharedName = name;

}

Person.prototype.getName = function() {

return sharedName;

};

return Person;

}());

Here, sharedName is shared across all instances of Person, and every new instance overwrites the value with the name that is passed in. This is clearly a nonsensical example, but is an important first step towards understanding how to get to truly private members for instances.

Towards truly private members

The pattern for shared private members points to a potential solution: what if the private data wasn’t stored on the instance but the instance could access it? What if there was an object that could be hidden away with all of the private info for an instance. Prior to ECMAScript 6, you’d so something like this:

var Person = (function() {

var privateData = {},

privateId = 0;

function Person(name) {

Object.defineProperty(this, "_id", { value: privateId++ });

privateData[this._id] = {

name: name

};

}

Person.prototype.getName = function() {

return privateData[this._id].name;

};

return Person;

}());

Now we’re getting somewhere. The privateData object isn’t accessible from outside of the IIFE, completely concealing all of the data contained within. The privateId variable stores the next available ID that an instance can use. Unfortunately, that ID needs to be stored on the instance, so it’s best to make sure it can’t be changed in any way, thus using Object.defineProperty() to set its initial value and ensure the property isn’t writable, configurable, or enumerable. That protects _id from being tampered with. Then, inside of getName(), the method accesses _id to get the appropriate data from the private data store and return it.

This approach is a pretty nice solution to the instance private data problem except for that ugly vestigial _id that is tacked onto the instance. This also suffers the problem of keeping all data around in perpetuity even if the instance is garbage collected. However, this pattern is the best we can do with ECMAScript 5.

Enter weakmap

By adding a weakmap into the picture, the “almost but not quite” nature of the previous example melts away. Weakmaps solve the remaining problems of private data members. First, there is no need to have a unique ID because the object instance is the unique ID. Second, when an object instance is garbage collected, all data that is tied to that instance in the weakmap will also be garbage collected. The same basic pattern as the previous example can be used, but it’s much cleaner now:

var Person = (function() {

var privateData = new WeakMap();

function Person(name) {

privateData.set(this, { name: name });

}

Person.prototype.getName = function() {

return privateData.get(this).name;

};

return Person;

}());

The privateData in this example is an instance of WeakMap. When a new Person is created, an entry is made in the weakmap for the instance to hold an object containing private data. The key in the weakmap is this, and even though it’s trivial for a developer to get a reference to a Person object, there is no way to access privateData outside of the instance, so the data is kept safely away from troublemakers. Any method that wants to manipulate the private data can do so by fetching the appropriate data for the given instance by passing in this and looking at the returned object. In this example, getName() retrieves the object and returns the name property.

Conclusion

I’ll finish with how I began: I was wrong about weakmaps. I now understand why people were so excited about them, and if I used them for nothing other than creating truly private (and non-hacky) instance members, then I will feel I got my money’s worth with them. I’d like to thank Nick Fitzgerald for his post that inspired me to write this, and for opening my eyes to the possibilities of weakmaps. I can easily foresee a future where I’m using weakmaps as part of my every day toolkit for JavaScript and I anxiously await the day that we can use them cross-browser.

References

Hiding implementation details with ECMAScript 6 WeakMaps by Nick Fitzgerald (fitzgeraldnick.com)

January 7, 2014

How to be a mentor

Mentorship tends to be a hot topic at any company that cares about its employees. I’ve experienced a variety of mentorship approaches in my career and learned one important lesson: very few people are taught how to be mentors. There are no good guides, no classes, and typically little organizational support. Yet that won’t stop people from assigning you to be a mentor or having people approach you in an ad hoc way about helping them at work.

I’m a very big believer that mentoring should be part of every senior engineer’s job. Senior engineers should mentor junior engineers, staff engineers should mentor senior engineers, principal engineers should mentor staff engineers, and so on. The junior engineers are, naturally, off the hook until they get promoted. Mentorship should be a vital part of any engineering organization, as working with people becomes more and more important in your career.

Over the years, I’ve learned a lot through the mentors I had and have done a lot of reflection to figure out why they were so effective. I’ve tried to put those learnings into action with the engineers I’ve mentored. Here are some of the things I’ve learned.

Make it their time

As opposed to meeting with managers, where the manager likely has some sort of agenda for their employee, a mentoring relationship and discussion should be different. This is the mentee’s time and they should be free to use it how they see fit. As a mentor, you can have certain agenda items for the mentee, such as encouraging them to be more outspoken. However, the meeting time is for the benefit of the mentee, and that means they should be the ones setting the primary agenda for the discussion.

As a mentor, you should help fill in the gaps if the mentee isn’t sure what to discuss. Ask what they’ve been working on recently and whether or not there were any issues with it. Are they enjoying their team? What do they want to focus on? Simple questions can help kickstart a conversation.

Mentor the whole person

It’s very easy to get caught up in the career aspect of mentorship. Many mentees are looking for tips to get promoted or land a different job. That’s all well and good, and honestly, is the easiest part of mentoring. In any company there’s usually a prescription for getting promoted, and to the extent you can articulate that in a useful way, you are being a good mentor. But there’s more to a person than career aspirations.

As a mentor, you need to understand where career fits into this person’s life. Is it the most important driver? Is it a means to provide for a family? Is there a longer-term goal? What drives this person? Is it a thirst and curiosity for knowledge? Is it gaining necessary experience to move into a different role? Getting a good understanding of the whole person helps you to better evaluate what happens at work. For instance, if you notice the person struggling for apparently no reason, asking how things are outside of work is usually a good first step.

Always keep in mind that your goal, as a mentor, is to help your mentees succeed in their professional life. Success can mean getting promoted, becoming a manager, or even working at a different company that is a better fit. Understanding more about the person than just the next step in their career is imperative.

Don’t give answers, provide strategies

Especially with technical mentoring, people will come to you with technical questions and it will be tempting to give them the answer. Don’t. People learn a lot better when they figure things out on their own. That doesn’t mean you stonewall when a question is asked. Instead of giving the answer, try to point them in the right direction by asking questions or suggesting other ways of approaching the problem. Some of the things I say frequently:

Start from the top, what is the problem you are trying to solve?

What would make this problem easier to solve?

What alternatives have you looked at?

Have you considered __________ or __________? Try looking them up and let me know what you think.

Are there any easier ways to do the same thing?

For technical mentoring, these sort of questions end up turning into a repeatable strategy. No one needs me there to ask them these questions all the time, they are questions anyone can ask themselves when they stuck. Repeating questions like this when asked for help is at first an introduction and later a reminder of the way that they can solve problems on their own..

Non-technical questions can sometimes be easier in this regard, as there are frequently no clear-cut answers. Some of the items in my bag of tricks for non-technical issues:

Encourage taking someone else’s point of view, especially when there are disagreements. What is their goal versus the goal of the person they’re disagreeing with?

In contentious situations, what sort of outcome are they looking for?

Share a story about a similar incident you dealt with, making sure to highlight that your approach may not be correct all the time.

Sometimes for younger mentees, it also helps to explain to them the roles of the people involved with a situation. Oftentimes, they won’t understand exactly what the product manager is trying to do or why the engineering manager is making a change. (Admittedly, sometimes even more experienced mentees still don’t understand the dynamics and relationships at play.)

Give homework

The best thing you can do for a mentee is to give them homework. When they come to you with areas of interest or problems, point them in the direction of some authoritative work that can help them. These days there are no shortages of blog posts, articles, books, and talks that are freely available online on almost any topic you can imagine. Make sure to provide these on a regular basis. As all great teachers know, learning needs to be continued outside of the classroom for the teachings to sink in.

That also means you have to do a bit of research. If your mentee has a particular area of interest, it’s worth your time to research that area and see if you can find some good resources to share. Junior engineers, especially, can have a harder time discerning between advice from a random blog post and advice from an authoritative source. Your guidance and direction as it relates to outside sources is a key asset.

Don’t prevent all mistakes, just horrible ones

A common mistake I see when people start to mentor others is the need to prevent their mentees from making mistakes. This is absolutely the wrong thing to do. Your job as a mentor isn’t to prevent your mentees from making mistakes. On the contrary, you want them to make a certain class of mistakes so they can learn from them. Looking back over my career, I’m thankful for the mistakes I made because the lessons I learned really sunk in. Don’t deny your mentees that learning experience.

A day of lost work pursuing the wrong solution is something that is acceptable from a learning point of view. The pain of that work will remain long after the day is gone. In fact, most of the guidelines I wrote about in Maintainable JavaScript come directly from painful mistakes that I or someone I worked with made during my career (I recount those stories in the book, so readers understand the origin of the guidelines).

What you really must prevent are the atrocious mistakes, the ones that could severely impact the mentee’s career or the company as a whole. Your goal is to prevent career-threatening lapses in judgment. Fortunately, most people aren’t in a situation where they can really screw things up terribly – but some still find creative ways to do so.

If a mentee is headed in the wrong direction, it’s often a good idea to just keep an eye and let them trudge down the path until they realize the mistake. If, however, they are trudging right off a ledge, then it’s your job as a mentor to get in the way and turn them around.

Don’t try to create a you-clone

Another common mistake I see with new mentors is trying to get their mentees to think and act like them. Despite what our egos tell us, it is not beneficial to have two or more people who all think and reason in the exact same way. Creating a walking, talking clone of yourself is doing both you and your mentee a disservice. That is explicitly a non-goal of mentoring.

As a mentor, you want to help your mentee develop their own ideas and strategies. You want them to become fully-formed human beings capable of existing without direct guidance. You are there to lend insights from your experience and prevent horrible mistakes from happening, but otherwise you are there to guide their development into a more experienced version of themselves.

If a mentee solves a problem in a way that you wouldn’t have solved it, ask yourself if that will cause a catastrophe. Is it worse or just different? And if it is worse, how much worse? Is it an emergency or are we talking about a slight difference that will be hardly noticeable in any situation?

Unless you micromanage your mentee, there is no way that they will end up doing the exact same thing as you in every situation…and chances are that neither of you want that. Let them develop into their own career and guide them along that path. There’s already one of you, that’s enough.

Conclusion

Mentoring is important for career growth. I certainly wouldn’t be where I am today if not for the mentors that guided me along the way. If you are a more experienced engineer, take the time to mentor someone who is more junior to you. It can be incredibly rewarding for both of you and helps to foster important interpersonal skills that don’t usually get exercised in the tech industry. Just remember, this type of relationship is different than that of a colleague or a manager-employee. Mentors are resources for their mentees, and you do the mentees a disservice if you don’t keep that in mind.

December 27, 2013

On interviewing front-end engineers

There was a really nice article written by Philip Walton last week[1] regarding his experience interviewing for front-end engineering roles at various companies in San Francisco. To summarize, he was surprised by the types of questions he was asked (mostly having to do with computer science concepts) and the types of questions he wasn’t asked (what about the DOM?). I wish I could be surprised, but having lived in Silicon Valley for the past seven years, I have heard these stories over and over again. I don’t believe these problems are specific to the San Francisco Bay Area by any stretch of the imagination – I think it’s more specific to our industry the continuing misunderstanding about what front-end engineers do and the value we add.

We hire smart people

When Google was an up-and-coming company, they had a very regimented way of hiring. The idea was that they wanted to hire the smartest people possible and then, once hired, they would figure out where best to apply your smarts. That very necessarily meant that everyone had to come in getting more or less the same interview in an attempt to standardize the bar for “smart” as an engineer. That meant regardless of your area of expertise or focus, you would more or less be getting the same interview as every one else. Once deemed “smart”, you were in but had no idea what you’d be working on until you showed up on campus as a fully-credentialed employee.

I blame the Google approach for a lot of the bad hiring practices related to front-end engineers in the industry today. When I was interviewing with Google, I was taken aback by the questions being asked of me that had nothing to do with my expertise. I remember in a couple of instances pondering if I should just leave, because I had no idea how to use a heap sort to accurately track search query times for billions of requests. That wasn’t what I wanted to be doing with my career, I had no interest in this realm of computer science; what value could this question possibly provide?

(Note: I have no idea if Google still follows this same procedure for hiring. For the purposes of this post I’ll refer to this as “the Google approach” but I in no way mean to insinuate that things work exactly the same now. Also, Google has, and has had, some of the best and brightest front-end engineers in the world working for them. I by no means intend to say that they have done poorly in their front-end hiring.)

Human resources

From a practical point of view, and having gone through my own failed startup, I understand the Google approach. When a company is small and just starting out, you need people who are capable of doing many different things. You don’t have the luxury of having a front-end engineer and a back-end engineer and a database administrator and a site reliability engineer. You need people who can do many things, and it doesn’t even matter if they can do them at an expert level – they just need to do stuff that works and they need to be skilled enough to take on new tasks as they arise.

The Google approach of hiring works really well for this situation. You need a common idea of what is an acceptable skillset for an engineer at your company when resources are constrained. The primary motivation is the fluid mobility of an engineer from task to task, effectively, hiring human resources that can be deployed in any number of ways as priorities and needs shift. Young companies don’t have the luxury of specialists. Everyone needs to be as full stack as possible to get work done.

The good news is that this process produces very good results when you are looking for full stack engineers with a common core skillset. This often is the best way to go when a company is small and growing. Google kept using it even as it got larger and did start to augment it a bit for some specialists who came through (I did get a couple of JavaScript questions while interviewing with them).

Growing up

The biggest problem I’ve seen with growing companies is that they fail to adapt their interview processes as the company gets larger and the complexion of the team changes. As you decide to hire specialists and more experienced engineers, the Google approach to hiring starts to fail. The one-size-fits-all interview no longer applies and you start to run into trouble. It’s a difficult position for a company to be in. If you’ve never hired a specialist before, and it’s a specialty with which you have no experience, how can you formulate an interview process that accurately detects the skillset you seek?

So many companies use an “and” approach. That is, I want you to live up to the common core skillset that we expected of every engineer to this point and be able to do the specialty. This deludes the hiring company into believing that they are keeping their magic bar for engineers in tact and getting someone with the specialty they need. And sometimes that works. But most of the time it doesn’t.

Understanding front-end engineers

Hiring specialists is an especially difficult task for any company that doesn’t have experience with that specialty. The reason is pretty obvious: specialists, by their nature, have expertise in something that is unique. Specialists care about things that other people don’t care about and willfully ignore things that most people do care about. The brain can only handle so much data, so to get a deep understanding of a particular topic it is often necessary to jettison other information that applies more broadly. For instance, there was a point in time where I could do anything in Visual Basic 4.0. These days, I’d be hard-pressed to come up with any working code short of copying it from the Internet. That wasn’t where I decided I wanted to spend my intellectual capital and so I let it fade.

Front-end engineers are, of course, specialists. We care about things that seem insane to others: understanding differences between dozens of browsers, pixels vs. ems, PNG vs. JPEG, compatibility of JavaScript APIs, how to construct a DOM to represent a UI, and so on. When I try to explain something cool I did to a back-end engineer, their eyes tend to glaze over very quickly. They will never understand the rush I get when I test something across Internet Explorer, Firefox, Chrome, and Safari and have it work for the first time. They will never understand why bold looks better than italic in a particular situation. They will never understand how I find bugs in browsers. They don’t have to.

What is important to know?

I’ve been getting asked more and more about whether or not front-end engineers need to understand computer science algorithms and data structures in order to be hired. My simple answer: no. I don’t see these as necessary prerequisites for people to be successful as front-end engineers. The reason is that these aren’t things most front-end engineers do on a day-to-day basis. Do I use algorithms and data structures? Sometimes, but I usually look up the things I need when I have a need for them. That information is easy to find online and there are always people around who know these topics better than me.

The things I look for in a front-end engineer have little to do with traditional computer science concepts. I’ve written before about what makes a good front-end engineer[2] and how to interview front-end engineers[3], and generally I still agree with everything I wrote in those articles. I want enthusiasm and passion for the web, and understanding of HTML, CSS, and JavaScript, and more importantly, how to use them together to create a solution to a problem.

In general, I believe interviews should be designed to demonstrate skills that a candidate will be expected to use on a day-to-day basis. It’s easy to pat ourselves on the back and chat about O-notation (which I had never even heard of until about 7 years into my career) or heap sort (the first time I encountered heap sort was during my Google interview), but is that a good indicator of whether or not someone will be successful as a front-end engineer? Absolutely not.

I’m not a big fan of trivia questions, either. Trivia questions are “name three ways to align something to the right”. Those questions remind me of high school tests, where you’re testing the ability to regurgitate information rather than seeing a demonstration of skills. What should you ask? Think about what you’re expecting someone to do on a regular basis in the role and ask something that approximates it. Not sure? You can always pull out a past problem that was experienced at the company and ask the candidate how they’d solve it. What I want to know is that if I come to you with a particular type of problem, you are willing and able to solve it.

I want to see how you attack a problem in your domain, how you work through issues and incompatibilities, what your instincts tell you when you get stuck, and whether or not you can take feedback and incorporate it into your process. That’s what makes people successful.

The lies we tell ourselves

The pervasiveness of questions such as finding palindromes, summing arrays, etc. are usually backed by a belief that these are providing vital pieces of data in sizing up a candidate. The various lies we tell ourselves regarding these questions usually sound like:

We’re getting good insights into their thought process – Bullshit. You get good insights into a person’s thought process not with trivia or random questions that are more likely to appear on a college computer science exams, but rather through situational exposure. Giving someone a question that is so far out of their normal work tells you little about their value. Does it tell you how they deal with situations that they are ill-suited to address? Totally. And if that’s your concern, then keep on asking these questions. Most engineers will be dealing with a particular problem space. That’s where questions should focus.

We hold everyone to this standard – This is the mythical measure of smarts. You believe that asking the same questions to everyone gives you a good measuring stick that is applicable everywhere. Except, no such measuring stick exists. Asking Michael Jordan to hit a 100-mph fastball would not give you any good insights into his athletic prowess. There are some people who will be pretty good at everything, but specialists, in particular, tend to let go of knowledge they don’t use every day in order to be specialists. There is no one measure of smarts.

It’s worked well to this point – Usually the cry of a growing company. We hired smart people in the past with these questions, why wouldn’t we continue? The reason you don’t continue is because the shape of the team has changed. You can now hire specialists that know more about their realm than anyone at your company probably does. You can hire the same type of people you’ve been hiring using the same process, but it’s crazy to think that you can hire a very different type of person using the same approach.

I’ve heard these over and over again in my career, and it frustrates me to no end. There is nothing more important than matching interview questions to what a candidate would actually do as an employee. That’s where the useful data lives in the process. Being unable to find palindromes for a word is interesting trivia, but what does it really tell you about the possibility of success if hired?

Conclusion

In my nearly 14-year career I’ve been responsible for hiring a large number of front-end engineers and I can say, proudly, that I’ve never made a bad hire. Some turned out to be merely good, others turned out to be excellent, but none of them were bad. I did this not by focusing on trivia and things that they wouldn’t actually end up doing on a daily basis; I did it by creating questions that showed me they would be able to take on the tasks I had waiting for them upon arrival. Getting to know people within their problem space is important, and if it hasn’t been clear in this article, this applies to all specialists (not just front-end engineers).

It is typically frustrating for specialists to interview with companies. What makes it better? Giving feedback. If you are the first specialist hired, give feedback about the interview process and see if it can be tweaked. Even if you don’t get hired, give feedback to your recruiter explaining that you didn’t think you were able to show your skills due to the questions you were asked.

Unfortunately, there are still many companies who will apply the one-size-fits-all approach to hiring engineers and you won’t get an interview tailored to your specific skills. Make no mistake, interviewing is hard and growing a company is extremely hard. The best way to change things is from the inside, so give feedback, get involved with your company’s hiring practices, and help make the next experience better for someone else.

References

Interviewing as a Front-end Engineer in San Francisco by Philip Walton (CSS Tricks)

What makes a good front-end engineer? by me (NCZOnline)

Interviewing the front-end engineer by me (NCZOnline)

November 12, 2013

In the ECMAScript 6 shadows: Native errors

ECMAScript 6 is coming up on the horizon, with JavaScript engines starting to implement certain features. There are some parts of the specification that have received a lot of attention: WeakMap, classes, generators, modules, and more. These represent large changes and additions over the ECMAScript 5 specification. However, there are certain smaller parts of the specification that are easy to miss yet equally important for the future of JavaScript. They are so small that barely anyone talks about them and you might not even know they are there unless you spend some time reading the actual specification. One such feature is native errors.

Errors today

To understand why native errors are so exciting, you first have to understand how errors work today. All errors thrown by the JavaScript engine inherit from `Error`, which is to say that all errors have `Error.prototype` in their prototype chain. The list of errors from ECMAScript 5 are:

Error – base type for all errors. Never actually thrown by the engine.

EvalError – thrown when an error occurs during execution of code via eval()

RangeError – thrown when a number is outside the bounds of its range. For example, trying to create an array with -20 items (new Array(-20)). These occur rarely during normal execution.

ReferenceError – thrown when an object is expected but not available, for instance, trying to call a method on a null reference.

SyntaxError – thrown when the code passed into eval() has a syntax error.

TypeError – thrown when a variable is of an unexpected type. For example, new 10 or "prop" in true.

URIError – thrown when an incorrectly formatted URI string is passed into encodeURI, encodeURIComponent, decodeURI, or decodeURIComponent.

You can also choose to throw these errors using their constructors, however, most developers throw their own custom errors. The uninitiated tend to start out by just using generic `Error` objects, such as:

throw new Error("This is my custom error message.");

The problem them becomes distinguishing between errors thrown by the JavaScript engine and errors thrown by developers. This is a very important aspect of a good error handling strategy in applications. The traditional way to do this is to create your own base error type, which inherits from `Error`, and then have all of your other error types inherit from that. For example:

function MyError(message) {

this.message = message;

}

MyError.prototype = Object.create(Error.prototype, {

name: { value: "MyError" }

});

function ThatNameIsStupidError(message) {

this.message = message;

}

ThatNameIsStupidError.prototype = Object.create(MyError.prototype, {

name: { value: "ThatNameIsStupidError" }

});

function YouDidSomethingDumbError(message) {

this.message = message;

}

YouDidSomethingDumbError.prototype = Object.create(MyError.prototype, {

name: { value: "YouDidSomethingDumbError" }

});

So the custom errors to use are ThatNameIsStupidError and YouDidSomethingDumbError. Both inherit from MyError and the intention is that any developer-defined errors will inherit from that common base type, allowing you to do things like this:

try {

doSomethingThatMightThrowAnError();

} catch (error) {

if (error instanceof MyError) {

// handle developer-defined error

} else {

// handle native error

}

}

In this code, you check to see if the thrown error is an instance of MyError, knowing that all developer-defined errors inherit from that common type. It’s pretty straightforward to set this up, though it does require that extra base type to determine from where the error originated.

Enter native errors

ECMAScript 6 defines a new type of error called NativeError. Section 19.5.6[1] describes this object type:

When an ECMAScript implementation detects a runtime error, it throws a new instance of one of the NativeError objects defined in 19.5.5. Each of these objects has the structure described below, differing only in the name used as the constructor name instead of NativeError, in the name property of the prototype object, and in the implementation-defined message property of the prototype object.

Looking back at section 19.5.5 (mentioned in the first sentence), you’ll see that the NativeError objects are:

EvalError

RangeError

ReferenceError

SyntaxError

TypeError

URIError

That means all of the runtime errors thrown by the JavaScript engine now inherit from NativeError instead of inheriting from Error (NativeError inherits from Error, so all existing code using instanceof Error will still work). That means you will one day be able to tell the difference between your errors and the JavaScript engine’s errors using code like this:

try {

doSomethingThatMightThrowAnError();

} catch (error) {

if (error instanceof NativeError) {

// handle native error

} else {

// handle developer-defined error

}

}

So instead of needing to create your own custom base error type (like MyError), any developer-defined error will be easily identifiable because it does not inherit from NativeError. That means you get to write less code to be able to make this distinction amongst errors.

Conclusion

Error handling isn’t a sexy topic, but one that becomes more important as your application grows larger. This subtle change in how errors work is both brilliant and effective at solving one of the significant pain points in JavaScript regarding handling errors. I’m very happy to see this change in ECMAScript 6 and look forward to seeing what other interesting features are lurking in the shadows of the specification.

References

ECMAScript 6: Native Error Object Structure

November 4, 2013

Now available: ESLint v0.1.0

It was four months ago when I announced the start of the ESLint project. My initial goal was to create a fully-pluggable JavaScript code quality tool where\ every single rule was a plugin. Though I like and appreciate JSHint, the inability to be able to define my own rules alongside the existing ones was keeping several of my projects from moving forward. After doing an initial prototype using Esprima, I was convinced this idea would work and started building ESLint one weekend.

Contributions

Since that time, I’ve been joined by 28 contributors who have implemented new rules, fixed bugs, wrote documentation, and otherwise contributed to the ongoing development of ESLint. Without their help, it probably would have taken several more months to reach the point we’re at now. I’d like to especially call out the work of Ian Christian Myers, Ilya Volodin, Matt DuVall, James Allardice, and Michael Ficarra for their constant and ongoing work, participation in conversations, and dedication to the project.

Alpha release

Today I’m excited to announce version 0.1.0 is available. This is the first alpha version that is ready for people to start using and give us feedback on. Up until this point, the tool was in a state of constant flux and I didn’t feel comfortable recommending anyone use it. I wanted to get ESLint as close to the ruleset of JSHint before deeming it ready for use, and we are finally there. We have (as best we can tell), nearly 100% coverage of the JSHint rules that don’t apply to formatting (white space and other code convention rules).

Here’s what this release gives you:

Most of the JSHint rules (that don’t apply to formatting issues)

New rules can be loaded at runtime

Specification of shared settings using .eslintrc files

Configure rules as disabled, warnings, or errors

Output results as Checkstyle, compact, JSLint-XML, or JUnit formats

95% or higher code coverage for statements, branches, functions, and lines

Known issues

As this is an early alpha release of ESLint, there are some issues we are aware of that need addressing:

Performance – on large files, ESLint can be around 3x slower that JSHint. This has to do with the number of times we are traversing the AST to gather information. We will be focusing on reducing these traversals to speed up execution.

Edge cases – there are almost certainly edge cases for each rule that we have not accounted for. We spent a lot of time looking through JSHint and JSLint code to try and figure out exact patterns to catch. If you find an edge case, please let us know.

No web UI – this is on the roadmap, and we are looking for someone to lead this initiative.

Documentation gaps – we have some good documentation but there are definitely some gaps. We will be working on filling those gaps.

Things that may change

Since this is the first alpha release, there are several things that may change going forward. Some of the potential changes are:

Removal of rules that don’t make sense

Renaming of rules

Splitting up of rules into more granular rules

Internal API changes (developers – be careful)

Internal Testing framework changes

Whenever possible, we will make changes in a backwards-compatible manner, but given the early stage of this project I can’t make any promises in this regard.

Installation

ESLint runs exclusively on Node.js, and is best installed using npm:

npm i -g eslint@0.1.0

ESLint requires Node.js 0.8 or higher.

Feedback

At this point, what we really need is feedback from you. You can send in general feedback to the mailing list or file an issue if there’s a problem or you’d like to request a feature. Your input will help us make ESLint even better going forward.

October 29, 2013

The problem with tech conference talks lately

I’ve spoken at my fair share of conferences over the years, and I used to get very excited about attending them. Lately, though, I’ve found myself more disappointed in conferences on a more frequent basis. Leaving aside the social aspects that have been increasingly under fire, I’d like to focus my attention squarely on the very thing that attracts people to conferences in the first place: the talks.

In my opinion, the quality of talks at many conferences has been dropping precipitously. This has little to do with the quality of speakers. There are some fantastic speakers who give incredibly mundane talks. There are some lousy speakers who give talks that are full of high-quality information. There are experienced speakers who end up speaking based on past excellent talks and fail to deliver. There are inexperienced speakers who knock it out of the park on the first try. The speakers aren’t actually the problem, it’s the content they produce.

Balancing conference schedules

Not all conference talks are of the same type. In general, I break down conference talks into several categories:

Instructional – teaches a topic

Case Study – explains a real-life implementation and its outcome

Inspirational – makes you think about something differently

Advertisement – introduces a product/library/framework/etc.

My preference is for conferences to be composed primarily of instructional and case study talks, roughly in equal portions (though I would love there to be slightly more case studies). The inspirational talks are usually reserved for opening and closing keynotes. The three other types of talks can form a really nice conference schedule when used appropriately. It’s the last one, advertisements, that are the problem.

Advertisement talks

Advertisement talks aren’t necessarily given by conference sponsors, though that is not uncommon. The purpose of an advertisement talk is to introduce you to a product in which the speaker has a vested interest. That means you could be introducing a new open source project you created, or a company could be introducing a new enterprise-grade storage solution, or an evangelist is going over a company’s API. All of these fall into the category of advertisement because the value to you is secondary to getting the message out about the product.

Don’t get me wrong, I don’t think all advertisement talks are bad and should be eliminated. My problem is that they now seem to represent the overwhelming majority of conference talks. The tech community has somewhat brought this on ourselves with our ravenous appetite for all things new and shiny. We’ve made celebrities out of John Resig and Jeremy Ashkenas for creating jQuery and Backbone, respectively. These are two very smart guys who have done amazing things for the web development community, and now everyone with an open source project and an idea is shooting for that level of popularity.

I see conference talks filled up with people who are presenting their new “awesome” project that will “totally blow your mind.” Only problem is that no one is using it yet, or it’s not even finished, or it’s version 0.0.1 so it would be foolish for you to even attempt to use it at this point. Here’s the thing: there is no value to me, as an audience member, if you’re talking about an unproven tool, framework, or library. I’m not going to risk my product on your unproven technology, I’m going to wait for someone else to do it.

Once again, I’m not proposing that conferences ban all advertisement talks. What I am proposing is that they be severely limited in their number. Keep the sponsored talks that you must, but let’s put a lid on the number of people talking about fledgling projects without any real world use cases.

Case study talks

These types of talks are, by far, the best to have at a conference. A case study talk takes you through an actual real world implementation of something. Case study talks can be a mixture of instructional and advertisement, but the value is that you get actual data and insights. What turns an advertisement talk into a case study talk? Compare:

“Introducing AbdominalRegion for Backbone.js”

vs.

“How we used AbdominalRegion for Backbone.js to decrease page load time by 50%”

The first talk title is a talk I will likely skip. Why would I care about this new tool you wrote? In the second talk title, I’m very interested in decreasing page load time for my Backbone.js application, and I’m very interested in anything that can help me do it.

Just like that, an advertisement talk that does nothing but promote your own project turns into a useful talk that also happens to talk about your own project. It’s the real world implications and uses of the project that make it compelling to an audience that is hungry to improve their products. I really don’t care if you have an MVC framework that you think is better than anything out there; I do care if your MVC framework can solve a problem I’m actually dealing with.

Most of my talks over the years have been case studies, and I like to think that’s part of why they’ve been well-received. I take my experience building large-scale applications (and last year, consulting for large companies) and put that experience into my talks. I want to help people solve problems they’re actually facing.

Tutorial talks also benefit from a case study treatment. Instead of telling me about how prototypes work in JavaScript, show me how using prototypes will make something I’m doing easier. Instead of walking through APIs for WebRTC, show me how to embed video chat into my product. All talks are instantly made better by applying the topic to a real-world situation that the audience may be dealing with.

And don’t forget to include the downsides in your case studies: the things you messed up, the problems you ran into, and what you learned from the whole process. Everyone improves when we share our experiences honestly.

If I were a conference organizer, I would be sure upwards of 80% of the talks were case studies. These types of talks provide the highest value to the audience and should be the focal point of any good conference.

A note for new project authors

At this point you may be thinking, “but if I can’t submit talks about my awesome project, how will people know how awesome it is?” The reason jQuery and Backbone.js became popular had nothing to do with John and Jeremy plastering the conference scene with talks. They became popular because they are good tools that helped people solve real problems. The popularity grew organically as more people found them useful. There was no grand marketing campaign.

The best thing you can do for your project is to use it in a real world situation and try it out. You probably started the project to solve some problem – now use it to see if the problem was solved. Next, show it to a few friends you trust. Ask them to try it out. See if they have any feedback.

For example, I started ESLint because I needed a JavaScript linter that had pluggable rules. I hacked something together one weekend and then started showing it to a few friends. I’ve yet to give a talk about it but people are finding it useful and contributing code.

After you get some good feedback, start attending local meetups. Those are good places to share what you’ve been working on and gather even more feedback from people who are thinking about similar problems. See if you can get a few more people to look at your project and try it out.

Once a few people have been using it and you’ve been incorporating feedback, you’ll have a good amount of real-world information about it’s use and what problems it can solve. At that point, by all means, start going to conferences and sharing what you know.

It’s about the content

All conferences begin and end with the content they provide in the form of talks. We need less pure instructional and advertisement talks and more case studies. As you’re filling out your talk proposals for 2014, think long and hard about what type of talk you’re proposing. Almost any talk can be augmented with real-world information to make it a case study. We all have interesting work experiences, think about sharing more of those and less about the open source project you’re hacking on during the weekends. Let’s flood conferences with so many high quality case studies that there are no “filler” talks.

If you’re a conference organizer, raise your bar in 2014. Limit the number of talks that “introduce” a new tool. Encourage those presenters to submit a case study showing how their new tool helped solve an actual problem. Ask those who submit tutorial talks to include a real-world use case or explain how the tips and techniques affect developers every day.

If you’re a conference attendee, tells the organizers what you want. You don’t want to be fed talk after talk about weekend side projects. You want quality. You want something that helps you do your job better. You want fewer talks that are thinly veiled advertisements for a company or product. You want quality, useful information.

Together, we can create conferences that aren’t just great social events, but also great learning events. The technical community has faced such a wide array of challenges and solved problems in interesting ways – we can all benefit from those experiences if we talk about them. Not all that is shiny is good, sometimes you just need a novel approach to using the tools you’re familiar with to make a big difference.

Let’s all agree to make a difference by sharing our experiences.

October 15, 2013

The best career advice I’ve received

I recently had an interesting discussion with a colleague. We were recounting our job histories and how our, shall we say colorful personalities, could have negatively impacted us long term. The truth is, I was kind of an asshole coming out of college (some would argue I’m still kind of an asshole, but that’s beside the point). I was arrogant and bitingly sarcastic, a generally irreverent character. I thought I knew it all and was quite proud of myself for it.

I had a habit of telling more experienced engineers that they were doing things wrong, and despite being right most of the time, I didn’t have the personality to make it effective. During one particularly engaging conversation, one of the senior engineers stopped and said, in these exact words, “I’m going to f***en beat the shit out of you if you don’t shut up.” I laughed it off because I knew he wouldn’t dare, and only years later did I realize the relevance of that statement: it was actually what he wanted to do.

Since that time I’ve grown up a lot, learned to watch what I say, and treat people with respect regardless of defining characteristics. The sarcasm stays in check while in a professional environment; I let it out to play when I’m with good friends. This self-control, along with a lot of other invaluable lessons, came to me not of my own accord, but through the careful guidance of the mentors I’ve had along the way. If not for them, who knows if my interpersonal relationships would have short-circuited my career.

The truth is that I have been incredibly blessed in my career because of the people I’ve come into contact with. My managers along the way molded a really rough-around-the-edges character into someone I’m proud to be. More than that, because of their influence, I’m not just a good programmer – I’m a good teammate and a good person. So impactful were these people on my life that I frequently recount their advice to the colleagues that I now mentor.

I also find their advice to be universally applicable, so I’d like to share the things I was told that helped me along the way. Of course, some of these are paraphrased since my memory for exact phrases isn’t all that great, but I believe I’ve captured the important parts correctly.

Don’t be a short-order cook

My very first job lasted 8 months because the company shut down. As I was talking with my manager about what I would do next, he gave me this advice:

Nicholas, you’re worth more than your code. Whatever your next gig is, make sure that you’re not a short-order cook. Don’t accept a job where you’re told exactly what to build and how to build it. You need to work somewhere that appreciates your insights into the product as well as your ability to build it.

This is something I’ve kept in mind throughout my career. Simply being an implementer isn’t good enough – you need to be involved in the process that leads up to implementation. Good engineers don’t just follow orders, they give feedback to and worth with product owners to make the product better. Fortunately, I’ve chosen my jobs wisely and never ended up in a situation where people didn’t respect or value my insights.

Self-promote

My second manager at Yahoo pulled me aside one day to give me some advice. He had been watching my work and felt like I was hiding a bit:

You do great work. I mean really great work. I like how your code looks and that it rarely breaks. The problem is that others don’t see it. In order for you to get credit for the work you’re doing, you have to let people know. You need to do a bit of self-promotion to get noticed.

It took me a little while to digest what he was saying, but I finally figured it out. If you do good work, but no one knows that you did good work, then it doesn’t really help you. Your manager can back you up but can’t make your case for you. People within the organization need to understand your value, and the best way to do that is to tell people what you did.

This is advice I give to many of my colleagues now. Self-promoting doesn’t mean, “look at me, I’m awesome.” It means letting people know when you’ve hit major milestones, or when you’ve learned something new. It means showing people the work that you’re proud of. It means celebrating your accomplishments and the accomplishments of others. It means being visible within the organization. The engineer who sits quietly in a corner and just codes away is always a bit mysterious – don’t be like that. A quick email to say, “hey, I finished the new email layout. Let me know what you think” goes a long way.

It’s about people

I was very title-driven earlier in my career. I always wanted to know what I had to do to be promoted. During my first one-on-one with my new manager on the Yahoo homepage, I asked what it would take for me to get promoted. His words still ring in my ears:

At a certain point, you stop being judged on your technical knowledge and start being judged on the way you interact with people.

I’m not sure I’ve ever received a better insight into the software engineering profession since that time. He was exactly right. At that point, no one was questioning my technical ability. I was known as a guy who wrote good, high-quality code that rarely had bugs. What I lacked was leadership skill.

Since that time, I’ve seen countless engineers get stuck at one level in their career. Smart people, good code, but the inability to work effectively with others keeps them where they are. Anytime someone feels stuck in their software engineering career, I recount this advice and it has always been right on the money.

None of this matters

I went through a period at Yahoo where I was frustrated. Maybe frustrated isn’t the right word, more like angry. I had angry outbursts and was arguing with people constantly. Things were going wrong and I didn’t like that. During one particularly rough day, I asked one of my mentors how he managed to stay calm when so many things were going wrong. His response:

It’s easy. You see, none of this matters. So some crappy code got checked in, so the site went down. So what? Work can’t be your whole life. These aren’t real problems, they’re work problems. What really matters is what happens outside of work. I go home and my wife is waiting for me. That’s pretty nice.

I had moved to California from Massachusetts and had a hard time making friends. Work was my life, it was what kept me sane, so when it wasn’t going that meant my life wasn’t going well. This conversation made me realize I had to have something else going on in my life, something I could go back to and forget about the troubles I had at work.

He was right, once I shifted my mindset and recategorized the annoying things at work as “work things,” I was able to think more clearly. I was able to calm down at work and have much more pleasant interactions with people.

Authority, your way

When I was first promoted to principal engineer at Yahoo, I sat down with my director to better understand what the role entailed. I knew I had to be more of a leader, but I was having trouble being authoritative. I asked for help. Here’s what he said:

I can’t tell you how to be authoritative, that’s something you need to figure out on your own. Different people have different styles. What you need to do is find a style that you can live with, that makes you comfortable. I can’t tell you what that is, but you do need to find it for this position.

I spent a lot of time that year observing people of authority and how they interacted with others. I took note as to how they walked, how they talked, how they dealt with problem situations. I tried different styles before I finally came across one that worked for me. My style is uniquely me and anyone learning to be in a position of authority has to go through the same growing pains. My advantage was that my mentor clued me about the process up front.

Moving from “how?” to “what?”

During a conversation with my manager at Yahoo, I asked what the expectations were with my new position. He answered:

To this point in your career, you’ve answered the question, “how?” As in, we tell you what needs to be done and you figure out how to do it. At this point, though, you need to answer the question, “what?” I’m expecting you to come and tell me what needs to be done.

This is the part where I see a lot of engineers get tripped up, and I would have as well if not for this piece of advice. Switching from “how?” to “what?” is very hard and takes time to develop. It also takes a bit of maturity to be left to your own desires as to what you focus on. After all, if you can spend your time on anything you want, you are also solely responsible for what you produce.

At Box, we call this “running open loop,” meaning that you do your job with minimal oversight and yet still are making a significant positive impact on the engineering organization and the company as a whole. This is the step where many engineers fail to make the leap, and I still give this advice to anyone who is trying to get to the next level.

Act like you’re in charge

I had just sat through a meeting where I had nothing to say. During my one-on-one with my director, I mentioned that I was just in a meeting where I had no idea why I was there and had nothing to contribute. He said:

Don’t ever do that again. If you’re in a meeting, it’s because you are there to participate. If you’re not sure why you’re there, stop and ask. If you’re not needed, leave. You’re in a leadership position, act like it. Don’t go quietly into a room. Just act like you’re in charge and people will believe it.

In that piece of advice, my mentor had reminded me of a lesson I learned while acting in high school: no one knows when you’re acting. If you’re nervous but act like you’re not, then people won’t know that you’re nervous. The same with leadership. The old phrase fake it til you make it comes to mind. From that point on, I never sat quietly in a meeting. I made sure I only went to meetings that needed me to participate and then I would participate.

Let them win

I went through a particular period where there were a lot of arguments on the team. I prided myself on ending those arguments with authority. I had a “my ruling is final” mentality, and my manager noticed that and gave me this piece of advice:

I see a lot of arguing going on, and I see you pushing through to win a lot. I know that most of the time you are right, but every once in a while let them win. Pick the things that really matter to you and push for those but let the other things go. There’s no need to win every argument.

This was one piece of advice I resisted initially. I was right nearly all of the time, why would I ever let someone else win? However, as I had grown to trust his instincts, I gave it a shot. The result: there were less arguments. People didn’t feel like they had to get one over on me, and in turn, I became better at identifying things I really didn’t care that much about. I stuck to my guns on important issues and let the others ones get resolved by the other party. The intensity of all conversations dropped considerably.

Conclusion

Looking back at the brash guy I was when I graduated college, my career could have ended up very different. I was seen as a malcontent, a smart but hard-to-deal-with guy who people dealt with because they had to. If it weren’t for the mentors I had along the way, as well as some humbling failures early in my career, my interpersonal skills (or lack thereof) could have very well done me in. These days, I regularly seek out those who are more experienced than me and ask for advice. I may no longer make big, glaring mistakes, but I also don’t want to wait for one to happen to seek out the experienced insights of someone I trust.

The nearly five years I was at Yahoo were some of the most transformative in my career. I got to work on interesting problems at a large scale, but moreso I was blessed with a series of wonderful managers and other mentors within my organization. I credit those conversations with turning me into a person that I’m proud of today, both at work and outside in “real life.”

If I can leave you with one overriding piece of career advice, it would be this: identify someone at your work that is smarter than you in some way (technically, organizationally, etc.) and attach yourself to them. See if you can regularly have lunch or coffee and pick their brain for the vast amount of knowledge it has. Your career, and maybe even your life, could end up drastically better by doing so.

October 7, 2013

Node.js and the new web front-end

Front-end engineers have a rather long and complicated history in software engineering. For the longest time, that stuff you sent to the browser was “easy enough” that anyone could do it and there was no real need for specialization. Many claimed that so-called web developers were nothing more than graphic designers using a different medium. The thought that one day you would be able to specialize in web technologies like HTML, CSS, and JavaScript was laughable at best – the UI was, after all, something anyone could just hack together and have work.

JavaScript was the technology that really started to change the perception of web developers, changing them into front-end engineers. This quirky little toy language that many software engineers turned their noses up at became the driving force of the Internet. CSS and HTML then came along for the ride as more browsers were introduced, creating cross-browser incompatibilities that very clearly defined the need for front-end engineers. Today, front-end specialists are one of the most sought after candidates in the world.

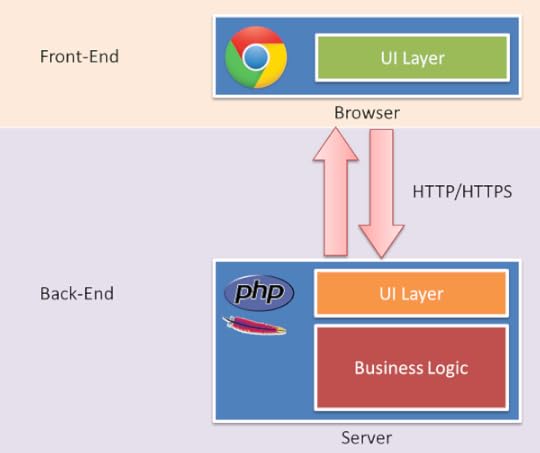

The two UI layers

Even after the Ajax boom, the front-end engineer was seen as primarily working with technologies inside of a browser window. HTML, CSS, and JavaScript were the main priorities and we would only touch the back-end (web server) in order to ensure it was properly outputting the front-end. In a sense, there were two UI layers: the one in the browser itself and the one on the server that generated the payload for the browser. We had very little control over the back-end UI layer and were often beholden to back-end engineers’ opinions on how frameworks should be put together – a world view that rarely took into consideration the needs of the front-end.

In this web application architecture, the UI layer on the browser was the sole domain of front-end engineers. The back-end UI layer was where front-end and back-end engineers met, and then the rest of the server architecture was where the guts of the application lived. That’s where you’d find data processing, caching, authentication, and all other pieces of functionality that were critical to the application. In a sense, the back-end UI layer (often in the form of templates) was a thin layer inside of the application server that only served a front-end as incidental to the business logic it was performing.

So the front-end was the browser and everything else was the back-end despite the common meeting ground on the back-end UI layer. That’s pretty much how it was until very recently.

Enter Node.js

When Node.js was first released, it ignited a level of enthusiasm amongst front-end engineers the likes of which hadn’t been seen since the term “Ajax” was first coined. The idea of writing JavaScript on the server – that place where we go only when forced – was incredibly freeing. No longer would we be forced to muddle through PHP, Ruby, Java, Scala, or any other language in addition to what we were doing on the front-end. If the server could be written in JavaScript, then our complete language knowledge was limited to HTML, CSS, and JavaScript to deliver a complete web application. That promise was, and is, very exciting.

I was never a fan of PHP, but had to use it for my job at Yahoo. I bemoaned the horrible time we had debugging and all of the stupid language quirks that made it easier to shoot yourself in the foot than it should be. Coming from six years of Java on the server, I found the switch to PHP jarring. I believed, and still do believe, that statically typed languages are exactly what you want in the guts of your business logic. As much as I love JavaScript, there are just some things I don’t want written in JavaScript – my shopping cart, for example.

To me, Node.js was never about replacing everything on the server with JavaScript. The fact that you can do such a thing is amazing and empowering, but that doesn’t make it the right choice in every situation. No, to me, I had a very different use in mind: liberating the back-end UI layer from the rest of the back-end.

With a lot of companies moving towards service-oriented architectures and RESTful interfaces, it now becomes feasible to split the back-end UI layer out into its own server. If all of an application’s key business logic is encapsulated in REST calls, then all you really need is the ability to make REST calls to build that application. Do back-end engineers care about how users travel from page to page? Do they care whether or not navigation is done using Ajax or with full page refreshes? Do they care whether you’re using jQuery or YUI? Generally, not at all. What they do care about is that data is stored, retrieved, and manipulated in a safe, consistent way.

And this is where Node.js allows front-end engineers a lot of power. The back-end engineers can write their REST services in whatever language they want. We, as front-end engineers, can use Node.js to create the back-end UI layer using pure JavaScript. We can get the actual functionality by making REST calls. The front-end and back-end now have a perfect split of concerns amongst the engineers who are working on those parts. The front-end has expanded back onto the server where the Node.js UI layer now exists, and the rest of the stack remains the realm of back-end engineers.

No! Scary!

This encroachment of the front-end into what was traditionally the back-end is scary for back-end engineers, many of whom might still harbor resentment against JavaScript as a “toy” language. In my experience, it is exactly this that causes the organizational disagreement related to the adoption (or not) of Node.js. The back-end UI layer is disputed land between the front-end and back-end engineers. I can see no reason for this occurring other than it’s the way things always have been. Once you get onto the server, that is the back-end engineer’s responsibility. It’s a turf war plain and simple.

Yet it doesn’t have to be that way. Separating the back-end UI layer out from the back-end business logic just makes sense in a larger web architecture. Why should the front-end engineers care what server-side language is necessary to perform business-critical functions? Why should that decision leak into the back-end UI layer? The needs of the front-end are fundamentally different than the needs of the back-end. If you believe in architectural concepts such as the single responsibility principle, separation of concerns, and modularity, then it seems almost silly that we didn’t have this separation before

Except that before, Node.js didn’t exist. There wasn’t a good option for front-end engineers to build the back-end UI layer on their own. If you were building the back-end in PHP, then why not also use PHP templating to build your UI? If you were using Java on the back-end, then why not use JSP? There was no better choice and front-end developers begrudgingly went along with whatever they had to use because there were no real alternatives. Now there is.

Conclusion

I love Node.js, I love the possibilities that it opens up. I definitely don’t believe that an entire back-end should be written in Node.js just because it can. I do, however, strongly believe that Node.js gives front-end engineers the ability to wholly control the UI layer (front-end and back-end), which is something that allows us to do our jobs more effectively. We know best how to output a quality front-end experience and care very little about how the back-end goes about processing its data. Tell us how to get the data we need and how to tell the business logic what to do with the data, and we are able to craft beautiful, performant, accessible interfaces that customers will love.

Using Node.js for the back-end UI layer also frees up the back-end engineers from worrying about a whole host of problems in which they have no concerns or vested interest. We can get to a web application development panacea: where front-end and back-end only speak to each other in data, allowing rapid iteration of both without affecting the other so long as the RESTful interfaces remain intact. Jump on in, the water’s fine.

September 10, 2013

Understanding ECMAScript 6 arrow functions

One of the most interesting new parts of ECMAScript 6 are arrow functions. Arrow functions are, as the name suggests, functions defined with a new syntax that uses an "arrow" (=>) as part of the syntax. However, arrow functions behave differently than traditional JavaScript functions in a number of important ways:

Lexical this binding – The value of this inside of the function is determined by where the arrow function is defined not where it is used.

Not newable – Arrow functions cannot be used a constructors and will throw an error when used with new.

Can’t change this – The value of this inside of the function can’t be changed, it remains the same value throughout the entire lifecycle of the function.

No arguments object – You can’t access arguments through the arguments object, you must use named arguments or other ES6 features such as rest arguments.

There are a few reasons why these differences exist. First and foremost, this binding is a common source of error in JavaScript. It’s very easy to lose track of the this value inside of a function and can easily result in unintended consequences. Second, by limiting arrow functions to simply executing code with a single this value, JavaScript engines can more easily optimize these operations (as opposed to regular functions, which might be used as a constructor or otherwise modified).

Syntax

The syntax for arrow functions comes in many flavors depending upon what you are trying to accomplish. All variations begin with function arguments, followed by the arrow, followed by the body of the function. Both the arguments and the body can take different forms depending on usage. For example, the following arrow function takes a single argument and simply returns it:

var reflect = value => value;

// effectively equivalent to:

var reflect = function(value) {

return value;

};

When there is only one argument for an arrow function, that one argument can be used directly without any further syntax. The arrow comes next and the expression to the right of the arrow is evaluated and returned. Even though there is no explicit return statement, this arrow function will return the first argument that is passed in.

If you are passing in more than one argument, then you must include parentheses around those arguments. For example:

var sum = (num1, num2) => num1 + num2;

// effectively equivalent to:

var sum = function(num1, num2) {

return num1 + num2;

};

The sum() function simply adds two arguments together and returns the result. The only difference is that the arguments are enclosed in parentheses with a comma separating them (same as traditional functions).

When you want to provide a more traditional function body, perhaps consisting of more than one expression, then you need to wrap the function body in braces and explicitly define a return value, such as:

var sum = (num1, num2) => { return num1 + num2; }

// effectively equivalent to:

var sum = function(num1, num2) {

return num1 + num2;

};

You can more or less treat the inside of the curly braces as the same as in a traditional function with the exception that arguments is not available.

Because curly braces are used to denote the function’s body, an arrow function that wants to return an object literal outside of a function body must wrap the literal in parentheses. For example:

var getTempItem = id => ({ id: id, name: "Temp" });

// effectively equivalent to:

var getTempItem = function(id) {

return {

id: id,

name: "Temp"

};

};

Wrapping the object literal in parentheses signals that the braces are an object literal instead of the function body.

Usage

One of the most common areas of error in JavaScript is the binding of this inside of functions. Since the value of this can change inside of a single function depending on the context in which it’s called, it’s possible to mistakenly affect one object when you meant to affect another. Consider the following example:

var PageHandler = {

id: "123456",

init: function() {

document.addEventListener("click", function(event) {

this.doSomething(event.type); // error

}, false);

},

doSomething: function(type) {

console.log("Handling " + type + " for " + this.id);

}

};

In this code, the object PageHandler Is designed to handle interactions on the page. The init() method is called to set up the interactions and that method in turn assigns an event handler to call this.doSomething(). However, this code doesn’t work as intended. The reference to this.doSomething() is broken because this points to a global object inside of the event handler instead of being bound to PageHandler. If you tried to run this code, you will get an error when the event handler fires because this.doSomething() doesn’t exist on the global object.

You can bind the value of this to PageHandler explicitly using the bind() method on the function:

var PageHandler = {

id: "123456",

init: function() {

document.addEventListener("click", (function(event) {

this.doSomething(event.type); // error

}).bind(this), false);

},

doSomething: function(type) {

console.log("Handling " + type + " for " + this.id);

}

};

Now the code works as expected, but may look a little bit strange. By calling bind(this), you’re actually creating a new function whose this is bound to the current this, which is PageHandler. The code now works as you would expect even though you had to create an extra function to get the job done.

Since arrow function have lexical this binding, the value of this remains the same as the context in which the arrow function is defined. For example:

var PageHandler = {

id: "123456",

init: function() {

document.addEventListener("click",

event => this.doSomething(event.type), false);

},

doSomething: function(type) {

console.log("Handling " + type + " for " + this.id);

}

};

The event handler in this example is an arrow function that calls this.doSomething(). The value of this is the same as it is within init(), so this version of the example works similarly to the one using bind(). Even though the doSomething() method doesn’t return a value, it is still the only statement executed necessary for the function body and so there is no need to include braces.

The concise syntax for arrow functions also makes them ideal as arguments to other functions. For example, if you want to sort an array using a custom comparator in ES5, you typically write something like this:

var result = values.sort(function(a, b) {

return a - b;

});

That’s a lot of syntax for a very simple procedure. Compare that to the more terse arrow function version:

var result = values.sort((a, b) => a - b);

The array methods that accept callback functions such as sort(), map(), and reduce() all can benefit from simpler syntax with arrow functions to change what would appear to be more complex processes into simpler code.

Other things to know

Arrow functions are different than traditional functions but do share some common characteristics. For example:

The typeof operator returns "function" for arrow functions.

Arrow functions are still instances of Function, so instanceof works the same way.

The methods call(), apply(), and bind() are still usable with arrow functions, though they do not augment the value of this.

The biggest difference is that arrow functions can’t be used with new, attempting to do results in an error being thrown.

Conclusion

Arrow functions are an interesting new feature in ECMAScript 6, and one of the features that is pretty solidified at this point in time. As passing functions as arguments has become more popular, having a concise syntax for defining these functions is a welcome change to the way we’ve been doing this forever. The lexical this binding solves a major painpoint for developers and has the added bonus of improving performance through JavaScript engine optimizations. If you want to try out arrow functions, just fire up the latest version of Firefox, which is the first browser to ship an implementation in their official release.

August 21, 2013

That time the lights went out at Etsy