Nicholas C. Zakas's Blog, page 17

October 14, 2011

CSS Lint v0.7.0 released

I'm happy to announce that version 0.7.0 of CSS Lint is now available on the web site, via GitHub, and through npm. This release focused very heavily on two things: documentation and stabilization.

For documentation, we've moved everything over onto a wiki, which allows us to quickly and easily update the documentation and more as we go. All prior documentation on the site as well as in the source code repository has been moved to the wiki. As part of the move, there is a long (and growing) Developer Guide to help you get started with contributing to the project.

Other notable changes in this release:

Improvements to the build tool now allow you to run JSHint via one command on the entire codebase as well as run unit tests on the command line. See the Developer Guide for more information.

Mahonnaise pointed out a problem with the parser API design that prevented easy addition of rules on the fly. That issue has been fixed.

Brent Lintner both suggested and implemented a --quiet option for the command line interfaces.

I noticed an issue with the Node.js CLI where output couldn't be captured on the command line. In the process of investigating, I discovered it to be a bug in Node.js and implemented a workaround. Unfortunately, that workaround cause another issue, reported by Grepsey, that led to another fix.

I updated the CSS parser to handle IE filters correctly and also to fix incorrect comment parsing as reported by andywhyisit.

Eric Wendelin continued his excellent work on the CLI by changing the API to accept and output relative paths by default instead of absolute paths. This does mean the output formats have changed slightly, but we think there shouldn't be any issues related to that.

Thanks once again to all of the great feedback and contributions we've been receiving from the growing CSS Lint community.

October 11, 2011

Simple, maintainable templating with JavaScript

One of my principles of Maintainable JavaScript is to keep HTML out of JavaScript. The idea behind this principle is that all markup should be located in one place. It's much easier to debug markup issues when you have only one place to check. I always cringe when I see code such as this:

function addItem(list, id, text){

var item = document.createElement("li");

item.innerHTML = "

Whenever I see HTML embedded inside of JavaScript like this, I foresee a time when there's a markup issue and it takes far longer than it should to track down because you're checking the templates when the real problem is in the JavaScript.

These days, there are some really excellent templating systems that work both in the browser and on the server, such as Mustache and Handlebars. Such templating systems allow all markup to live in the same template files while enabling rendering either on the client or on the server or both. There is a little bit of overhead to this in setup and preparation time, but ultimately the end result is a more maintainable system.

However, sometimes it's just not possible or worthwhile to change to a completely new templating system. In these situations, I like to embed the template into the actual HTML itself. How do I do that without adding junk markup to the page that may or may not be used? I use a familiar but under-appreciated part of HTML: comments.

A lot of developers are unaware that comments are actually part of the DOM. Each comment is represented as a node in the DOM and can be manipulated just like any other node. You can get the text of any comment by using the nodeValue property. For example, consider a simple page:

<!DOCTYPE html>

You can grab the text inside of the comment via:

var commentText = document.body.firstChild.nodeValue;

The value of commentText is simply, "Hello world!". So the DOM is kind enough to remove the opening and closing comment indicators. This, plus the fact that comments are completely innocuous within markup, make them the ideal place to put simple template strings.

Consider a dynamic list, one where you can add new items and the UI is instantly updated. In this case, I like to put the template comment as the first child of the or so its location isn't affected by other changes:

First item

Second item

Third item

When I need to add another item to the list, I just grab the template out of the comment and format it using a very simple sprintf() implementation:

/*

* This function does not attempt to implement all of sprintf, just %s,

* which is the only one that I ever use.

*/

function sprintf(text){

var i=1, args=arguments;

return text.replace(/%s/g, function(pattern){

return (i < args.length) ? args[i ] : "";

});

}

This is a very minimal sprintf() implementation that only supports the use of %s for replacement. In practice, this is the only one I ever use, so I don't bother with more complex handling. You may want to use a different format or function for doing the replacing – this is really just a matter of preference.

With this out of the way, I am left with a fairly simple way of adding a new item:

function addItem(list, id, text){

var template = list.firstChild.nodeValue,

result = sprintf(template, id, id, text),

div = document.createElement("div");

div.innerHTML = result;

list.appendChild(div.firstChild);

}

This function retrieves the template text and formats it into result. Then, a new is created as a container for the new DOM elements. The result is injected into the , which creates the DOM elements, and then the result is added to the list.

Using this technique, your markup still lives in the exact same place, whether that be a PHP file or a Java servlet. The most important thing is that the HTML is not embedded inside of the JavaScript.

There are also very simple ways to augment this solution if it's not quite right for you:

If you're using YUI, you may want to use Y.substitute() instead of sprintf() function.

You may want to put the template into a tag with a custom value for type (similar to Handlebars). You can retrieve the template text by using the text property.

This is, of course, a very simplistic example. If you need more complex functionality such as conditions and loops, you'll probably want to go with a full templating solution.

October 3, 2011

When web standards fail us

From time to time, web developers rise up and grumble more loudly about the failings of the W3C and ECMA for the ways they choose to evolve (or not evolve) the technologies of the web. We talk about design by committee as a failure, browser vendors should just implement and not worry about it…unless it's Microsoft, they should never do anything without asking someone else first…and whether or not there is a better, faster way to create change. I'm actually less concerned about organizational structure than I am about these groups' lack of focus.

The big problem

I have a bias when it comes to problem solving: once a problem is solved, I don't want to have to solve it again. When the problem is well-defined and the solution is understood and accepted, I want that to be the solution and move on to solving newer problems.

Each web standard committee has a single job, and that is to solve problems in their focus area. The committees seem to have trouble defining the problems they want to solve. To be fair, fully defining a problem is often the most complicated part of solving it. However, there are two sets of problems to select from and there are many problems that have yet to be addressed despite years of history.

Design for today, design for tomorrow

From speaking with various people who work on web standards, there are basically two types of problems they attempt to solve: the problems of today and the problems of tomorrow. The problems of today are known entities. The entire problem context is well known and developer-created solutions already exist. The problems of tomorrow are a bit more esoteric. These problems may not have yet been encountered by developers but the standards want to provide for their eventuality.

To be certain, both problem sets deserve their due time and diligence, and everything from HTML5 to ECMAScript 5 solves some problems of today while also addressing some problems of tomorrow. The getElementsByClassName() method and the Selectors API solved the problem of developers wanting to query the DOM by CSS classes and use CSS queries – both were already ubiquitous amongst JavaScript libraries. The Cross-Document Messaging API solved the problem of secure cross-frame communication where otherwise developers were using multiple embedded iframes just to pass data back and forth. ECMAScript 5 finally introduced the official way to assign getter and setters as well as controlling property enumerability. All of these were problems of today that were well understood and fairly quickly turned into officially supported APIs.

The problems of tomorrow are often centered around doing things on the web that aren't yet being done. I like to call this to Photoshop-on-the-web problem. It goes something like this: given that I someday want to write Photoshop as a web application, what would I need to make that happen? First, I would need some way to manipulate pixel data directly (solved by canvas). Then, I would need some way to crunch a lot of data without freezing the browser UI (solved by web workers). Of course, I would need to be able to read files directly from the desktop (solved by the File API).

You may be saying at this point, "but I do want to do that now!" That's fine, but these APIs came about before today. It's inevitable that some problems of tomorrow will become problems of today, but some may not. Do we really need databases in the browser, or are simple key-value stores enough? Only the future will tell.

Unsolved problems of today

As I said, it's definitely important to spend time both solving problems of today and looking forward at potential future problems that will trip people up. What I absolutely can't stand is the way web standards committees frequently overlook problems of today in favor of spending time on problems of tomorrow. If a problem is well-defined and affecting a large number of developers, let's solve that problem so no one ever has to re-solve it. There are a lot of problems that we've been dealing with a for long time and no one seems interested in addressing them. To me, this is the biggest failing of web standards: failure to allow developers to move on to more interesting problems.

Here's a list of current problems that are not yet solved:

Cookie reading/writing in JavaScript – Netscape gave us document.cookie. It hasn't changed at all since then, meaning anytime anyone wants to read from or write to a cookie, they must do all of the string formatting themselves. We've been writing JavaScript cookie libraries for the past 15 years and we still need them because the API never changed to reflect what we're actually doing. This is a glaring failure in the evolution of the web.

JavaScript string formatting – we've known for a decade that we need to be able to escape text for HTML and regular expressions, and that we have a need for general string formatting similar to sprintf(). Why is this not a solved problem? Why do we each have to rewrite such functionality over and over again? The next version of ECMAScript will apparently have a feature called quasis that tries to solve all problems using the same (new) syntax. I really don't like this because there's no backwards compatibility for what is a set of solved problems in the world of computer science. We're not breaking new ground here, an htmlEscape() method would be a great start, or implement String.format(). Something sane.

JavaScript date formatting – once again, a problem that has existed for over a decade. Why can't I easily do date formatting in JavaScript? Java has had this capability for a while, and it's not horrible. Why are we stuck still writing date formatting libraries?

Common UI paradigms – this one really bugs me. For the past decade, we've all been writing a ton of JavaScript to make the best UI controls. The controls have become ubiquitous in JavaScript libraries and often require a ton of code to make them work correctly. Why aren't there HTML tags that allow me to create these common UI paradigms:

Tabs – how many more times do we need to create JavaScript for a tabset? There are even ARIA roles to markup HTML to be tabs, why can't we have some tags whose default behavior is to use those roles? I am very tired of creating ever-newer versions of tabs.

Carousels – a very popular control that is little more than a tag that stops and starts periodically based on user interaction. There are few sites you can go to that won't have at least one carousel on the page. And having written a few, it's always a pain. Why can't this just be part of HTML?

Accordions – nothing magical here. Very close to the HTML5 element behavior. Why can't I have this natively?

Trees – another decade-long invention that we've still not standardized. In fact, my second-ever published article was about creating an expandable tree…that was in 2002. ARIA also has roles to represent trees, so why not have an HTML-native version?

JavaScript touch events – even though touchscreen technology is relatively new, there quickly emerged some common patterns that would be nice to have standardized. Why do I need to decipher multiple touch events to figure out what the user is doing? Why aren't there events for swipe, flick, tap, and pinch? I don't want to need a PhD in computer science to be able to program for the touch-enabled web.

Conclusion

I'm all for moving forward, and don't get me wrong, both TC-39 and the W3C have done a commendable job at solving many of today's problems. I'd just like to see more addressed so that we can stop solving the same problems repeatedly over the next decade. In another ten years, I don't want to be writing JavaScript to parse a cookie string, and I don't want to be debating the best way to create a tab control. These are all known problems that deserve attention now so that we can move on to solving more interesting problems in the future.

September 19, 2011

Script yielding with setImmediate

Those who have attended my talks on JavaScript performance are familiar with my propensity for using setTimeout() to break up long scripts into smaller chunks. When using setTimeout(), you're changing the time at which certain code is executed, effectively yielding the UI thread to perform the already-queued tasks. For example, you can instruct some code to be added to the UI thread queue after 50ms via:

setTimeout(function(){

//do something

}, 50)

So after 50ms, this function is added to the queue and it's executed as soon as its turn comes. A call to setTimeout() effectively allows the current JavaScript task to complete so the next UI update can occur.

Problems

Even though I've been a big proponent of using setTimeout() in this way, there are a couple of problems with this technique. First and foremost, timer resolution across browsers varies. Internet Explorer 8 and earlier have a timer resolution of 15.6ms while Internet Explorer 9 and later as well as Chrome have a timer resolution of 4ms. All browsers enforce a minimum delay for setTimeout(), so setTimeout(fn, 0) actually execute after 0ms, it executes after the timer resolution.

Another problem is power usage. Managing timers drains laptop and mobile batteries. Chrome experimented with lowering the timer resolution to 1ms before finding that it was hurting battery life on laptops. Ultimately, the decision was made to move back to a 4ms timer resolution. Other browsers have since followed suit, though many throttle timer resolution to 1s for background tabs. Microsoft found that lowering the timer resolution to 1ms can reduce battery run time by 25%. Internet Explorer 9, in fact, keeps timer resolution at 15.6ms when a laptop is running on battery and only increases to 4ms when plugged in.

The setImmediate() function

The Efficient Script Yielding specification from the W3C Web Performance Working Group defines a new function for achieving this breaking up of scripts called setImmediate(). The setImmediate() function accepts a single argument, which is a function to execute, and it inserts this function to be executed as soon as the UI thread is idle. Basic usage:

var id = setImmediate(function(){

//do something

});

The setImmediate() function returns an ID that can be used to cancel the call via clearImmediate() if necessary.

It's also possible to pass arguments into the setImmediate() function argument by including them at the end:

setImmediate(function(doc, win){

//do something

}, document, window);

Passing additional arguments in this way means that you needn't always use a closure with setImmediate() in order to have useful information available to the executing function.

Advantages

What setImmediate() does is free the browser from needing to manage a timer for this process. Instead of waiting for a system interrupt, which uses more power, the browser can simply wait for the UI queue to empty and then insert the new JavaScript task. Node.js developers may recognize this functionality since process.nextTick() does the same thing in that environment.

Another advantage is that the specified function executes after a much smaller delay, without a need to wait for the next timer tick. That means the entire process completes much faster than with using setTimeout(fn, 0).

Browser support

Currently, only Internet Explorer 10 supports setImmediate(), and it does so through msSetIntermediate() since the specification is not yet finalized. The Internet Explorer 10 Test Drive site has a setImmediate() example that shows the improved performance using the new method. The example sorts values using a delay while the current state of the sort is displayed visually. This example requires Internet Explorer 10.

The future

I'm very optimistic about the setImmediate() function and its value to web developers. Using timers for script yielding is a hack, for sure, and having an official way to yield scripts is a huge win for performance. I hope that other browsers quickly pick up on the implementation so we can start using this soon.

September 15, 2011

Experimenting with ECMAScript 6 proxies

ECMAScript 6, aka "Harmony", introduces a new type of object called a proxy. Proxies are objects whose default behavior in common situations can be controlled, eliminated, or otherwise changed. This includes definition what happens when the object is used in a for-in look, when its properties are used with delete, and so on.

The behavior of proxies is defined through traps, which are simply functions that "trap" a specific behavior so you can respond appropriately. There are several different traps available, some that are fundamental and some that are derived. The fundamental traps define low-level behavior, such as what happens when calling Object.defineProperty() on the object, while derived traps define slightly higher-level behavior such as reading from and writing to properties. The fundamental traps are recommended to always be implemented while the derived traps are considered optional (when derived traps are undefined, the default implementation uses the fundamental traps to fill the gap).

My experiments focused largely on the derived get trap. The get trap defines what happens when a property is read from the object. Think of the get trap as a global getter that is called for every property on the object. This made me realize that my earlier experiments with the proprietary __noSuchMethod__() might be applicable. After some tinkering, I ended up with the following HTML writer prototype:

/*

* The constructor name I want is HTMLWriter.

*/

var HTMLWriter = (function(){

/*

* Lazily-incomplete list of HTML tags.

*/

var tags = [

"a", "abbr", "acronym", "address", "applet", "area",

"b", "base", "basefont", "bdo", "big", "blockquote",

"body", "br", "button",

"caption", "center", "cite", "code", "col", "colgroup",

"dd", "del", "dir", "div", "dfn", "dl", "dt",

"em",

"fieldset", "font", "form", "frame", "frameset",

"h1", "h2", "h3", "h4", "h5", "h6", "head", "hr", "html",

"i", "iframe", "img", "input", "ins", "isindex",

"kbd",

"label", "legend", "li", "link",

"map", "menu", "meta",

"noframes", "noscript",

"object", "ol", "optgroup", "option",

"p", "param", "pre",

"q",

"s", "samp", "script", "select", "small", "span", "strike",

"strong", "style", "sub", "sup",

"table", "tbody", "td", "textarea", "tfoot", "th", "thead",

"title", "tr", "tt",

"u", "ul",

"var"

];

/*

* Define an internal-only type.

*/

function InternalHTMLWriter(){

this._work = [];

}

InternalHTMLWriter.prototype = {

escape: function (text){

return text.replace(/[>< "&]/g, function(c){

switch(c){

case ">": return ">";

case "< ": return "<";

case "\"": return """;

case "&": return "&";

}

});

},

startTag: function(tagName, attributes){

this._work.push("<" + tagName);

if (attributes){

var name, value;

for (name in attributes){

if (attributes.hasOwnProperty(name)){

value = this.escape(attributes[name]);

this._work.push(" " + name + "=\"" + value + "\"");

}

}

}

this._work.push(">");

return this;

},

text: function(text){

this._work.push(this.escape(text));

return this;

},

endTag: function(tagName){

this._work.push("");

return this;

},

toString: function(){

return this._work.join("");

}

};

/*

* Output a pseudo-constructor. It's not a real constructor,

* since it just returns the proxy object, but I like the

* "new" pattern vs. factory functions.

*/

return function(){

var writer = new InternalHTMLWriter(),

proxy = Proxy.create({

/*

* Only really need getter, don't want anything else going on.

*/

get: function(receiver, name){

var tagName,

closeTag = false;

if (name in writer){

return writer[name];

} else {

if (tags.indexOf(name) > -1){

tagName = name;

} else if (name.charAt(0) == "x" && tags.indexOf(name.substring(1)) > -1){

tagName = name.substring(1);

closeTag = true;

}

if (tagName){

return function(){

if (!closeTag){

writer.startTag(tagName, arguments[0]);

} else {

writer.endTag(tagName);

}

return receiver;

};

}

}

}

});

return proxy;

};

})();

This uses the same basic approach as my earlier experiment, which is to define a getter that interprets property names as HTML tag names. When the property matches an HTML tag name, a function is returned that calls the startTag() method, likewise a property beginning with an "x" and followed by the tag name receives a function that calls endTag(). All other methods are passed through to the interal writer object.

The InternalHTMLWriter type is defined inside of a function so it cannot be accessed outside; the HTMLWriter type is the preferred way to use this code, making the implementation transparent. Each called to HTMLWriter creates a new proxy which, in turn, has reference to its own internal writer object. Basic usage is:

var w = new HTMLWriter();

w.html()

.head().title().text("Example & Test").xtitle().xhead()

.body().text("Hello world!").xbody()

.xhtml();

console.log(w);

Ugly method names aside, the prototype works as you'd expect. What I really like about this type of pattern is that the methods can be easily updated to support new HTML tags by modifying the tags array.

The more I thought about proxies and the get trap, the more ideas I came up with. Developers have long tried to figure out ways to inherit from Array to create their own array-like structures, but we've also been unable to get there due to a number of issues. With proxies, implementing array-like data structures are trivial.

I decided that I'd like to make a stack implementation in JavaScript that uses an array underneath it all. I wanted the stack to be old-school, just push(), pop(), and length members (no numeric index support). Basically, I would just need to filter the members being accessed in the get trap. Here's the result:

var Stack = (function(){

var stack = [],

allowed = [ "push", "pop", "length" ];

return Proxy.create({

get: function(receiver, name){;

if (allowed.indexOf(name) > -1){

if(typeof stack[name] == "function"){

return stack[name].bind(stack);

} else {

return stack[name];

}

} else {

return undefined;

}

}

});

});

var mystack = new Stack();

mystack.push("hi");

mystack.push("goodbye");

console.log(mystack.length); //1

console.log(mystack[0]); //undefined

console.log(mystack.pop()); //"goodbye"

Here, I'm using a private stack array for each instance of my stack. Each instance also has a single proxy that is returned and used as the interface. So every method I want to allow ends up being executed on the array rather than the proxy object itself.

This pattern of object member filtering allowed me to easily enable the members I wanted while disabling the ones I didn't. The one tricky part was ensuring the methods were bound to the correct this value. In my first try, I simply returned the method from the array, but ended up with multiple errors because this was the proxy object instead of the array. I added the use of the ECMAScript 5 bind() method to ensure the this value remained correct for the methods and everything worked fine.

A few caveats as you start playing with proxies. First, it's only currently supported in Firefox 6+. Second, the specification is still in flux and the syntax, order of arguments, etc. may change in the future. Third, the patterns I've explained here are not and should not be considered best practices for using proxies. These are just some experiments I hacked together to explore the possibilities. Proxies aren't ready for production use but are a lot of fun for experimentation.

September 3, 2011

CSS Lint v0.6.0 now available

Following quickly on the heels of the v0.5.0 release, here comes the v0.6.0 release. This release saw a lot of activity around bug fixing, refactoring to make things easier, and documentation. Some of the highlights of this release:

New Rule: Mike Hopley suggested we add a rule that could suggest shorthand properties when all dimensions of margin and padding were provided as separate properties. That rule has been added.

Kasper Garnæs and Tomasz Oponowicz each contributed some cleanup code to the various XML formats the CLI supports, ensuring that proper escaping happened.

Kasper also submitted the checkstyle-xml output format for use with Checkstyle.

Cillian de Róiste contributed a fix for the Node.js CLI that ensures it will now handle absolute file paths correctly.

Eric Wendelin implemented the csslint-xml output format for compatibility with Jenkins Violations.

Julien Kernec'h added some missing CSS properties to the rule that checks for valid properties.

I took a first pass at creating a developer guide for CSS Lint, explaining how the code is organized and how the build system works.

The complete changelog can be found at GitHub. If you're using the Node.js version of CSS Lint, you can update your version via:

npm update csslint

Please keep those submissions and issues coming. The GitHub issue tracker is the best way to get our attention. We'd also love to hear about how you're integrating CSS Lint into your build system, feel free to drop us a line on the mailing list and tell us what you've been up to.

August 18, 2011

CSS Lint updated to 0.5.0

After a slight delay to figure out some UI changes, the 0.5.0 release of CSS Lint has now made it to csslint.net. As with previous releases, this release saw a mixture of bug fixes and new features. The biggest change you'll notice on the web site is that rules are now categorized based on how they help your code. We received a lot of feedback that you weren't sure why some rules were there. We hope that categorizing the rules will help clear up some of that confusion (there's more documentation coming, we promise!). There were also a lot of changes under the hood, here are the highlights:

cssguru pointed out that the !important rule didn't tell you how the target usage count. That has been addressed.

Eric created a one-line-per-file output format that matches JSHint's output format.

Senthil discovered a problem with the Rhino CSS Lint CLI where directories were not being read. The CLI has now been fixed and directories can be recursively read once again.

The CSS parser now correctly supports CSS keyframe syntax and CSS escaping.

cssguru also argued that having too many important declarations should not be an error. After some discussion, we agreed, and this is now a warning.

mahonnaise suggested that a rule to detect the universal selector would be a good addition to the tool. We agreed, and 0.5.0 now warns when using the universal selector as the key selector.

Oli found a bug in the box model rule where valid box model settings are flagged as problematic. This issue has been resolved.

I added a rule that checks for known CSS properties and warns if the property is unknown. Vendor-prefixed properties are considered exceptions to this rule.

Nicole added a rule that warns when a large negative text-indent is used without first setting the direction to ltr.

Of course, there are other miscellaneous fixes and tweaks that have gone into this release. If you're using CSS Lint for Node.js, you can update by typing:

npm update csslint

And please keep sending in your bugs and suggestions over on GitHub as well as asking questions on the mailing list. Your feedback has been invaluable in making this tool even better.

August 9, 2011

Introduction to the Page Visibility API

A major pain point for web developers is knowing when users are actually interacting with the page. If a page is minimized or hidden behind another tab, it may not make sense to continue functionality such as polling the server for updates or performing an animation. The Page Visibility API aims to give developers information about whether or not the page is visible to the user.

The API itself is very simple, consisting of three parts:

document.hidden – A boolean value indicating if the page is hidden from view. This may mean the page is in a background tab or that the browser is minimized.

document.visibilityState – A value indicating one of four states:

The page is in a background tab or the browser is minimized.

The page is in the foreground tab.

The actual page is hidden but a preview of the page is visible (such as in Windows 7 when moving the mouse over an icon in the taskbar).

The page is being prerendered off screen.

The visibilitychange event – This event fires when a document changes from hidden to visible or vice versa.

As of the time of this writing, only Internet Explorer 10 and Chrome (12+) have implemented the Page Visibility API. Internet Explorer has prefixed everything with "ms" while Chrome has prefixed everything with "webkit". So document.hidden is implemented as document.msHidden in Internet Explorer and document.webkitHidden in Chrome. The best way to check for support is with this code:

function isHiddenSupported(){

return typeof (document.hidden || document.msHidden || document.webkitHidden) != "undefined";

}

To check to see if the page is hidden, the following can be used:

function isPageHidden(){

return document.hidden || document.msHidden || document.webkitHidden;

}

Note that this code will indicate that the page is not hidden in unsupporting browsers, which is the intentional behavior of the API for backwards compatibility.

To be notified when the page changes from visible to hidden or hidden to visible, you can listen for the visibilitychange event. In Internet Explorer, this event is called msvisibilitychange and in Chrome it's called webkitvisibilitychange. In order to work in both browsers, you need to assign the same event handler to each event, as in this example:

function handleVisibilityChange(){

var output = document.getElementById("output"),

msg;

if (document.hidden || document.msHidden || document.webkitHidden){

msg = "Page is now hidden." + (new Date()) + ""

} else {

msg = "Page is now visible." + (new Date()) + ""

}

output.innerHTML += msg;

}

//need to add to both

document.addEventListener("msvisibilitychange", handleVisibilityChange, false);

document.addEventListener("webkitvisibilitychange", handleVisibilityChange, false);

This code works well in both Internet Explorer and Chrome. Further, this part of the API is relatively stable so it's safe to use the code in real web applications.

Differences

The biggest difference between the implementations is with document.visibilityState. Internet Explorer 10 PR 2′s document.msVisibilityState is a numeric value representing one of four constants:

document.MS_PAGE_HIDDEN (0)

document.MS_PAGE_VISIBLE (1)

document.MS_PAGE_PREVIEW (2)

document.MS_PAGE_PRERENDER (3)

In Chrome, document.webkitVisibilityState is one of three possible string values:

"hidden"

"visible"

"prerender"

Chrome does not feature constants for each state, though the final implementation will likely contain them.

Due to these differences, it's recommended not to rely on the vendor-prefixed version of document.visibilityState and instead stick to using document.hidden.

Uses

The intended use of the Page Visibility API is to signal that to the page that the user isn't interacting with the page. You can use that information to, for example, stop polling for updates from the server or stop animations (though if you're using requestAnimationFrame(), that will happen automatically).

After a little thought, I realized that the Page Visibility API is much more about the user than it is about the page, and so I added support to my YUI 3 Idle Timer component. The component now fires the idle event when the page becomes hidden and the active event when the page once again becomes visible.

Whether using the Idle Timer, or the Page Visibility API on its own, this new functionality gives web developers a much-needed peek into what the browser is doing with our web application. I hope to see many more great advancements coming from the W3C Performance group.

July 21, 2011

Quick and dirty: Spinning up a new EC2 web server in five minutes

One of the things I've become more adept at in my new life is dealing with the dizzying array of Amazon web services. The two parts of the Amazon kingdom that I've really enjoyed using are S3, their RESTful redundant storage solution, and EC2, the on-demand virtual machine system. Recently, I was in a situation where a bunch of us needed a web server quickly and I was able to get an EC2 instance up and running in a few minutes. Okay, to be fair, it took me a little longer than it will take you because I made a couple of mistakes, but now I can easily spin up a new EC2 instance with a basic web server in five minutes.

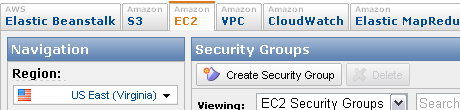

Create a security group (1st time only)

Go to the AWS console and click on the EC2 tab. On the lower-left is an option called Security Groups, click on that to bring up your current security groups. There is usually a default security group that allows SSH and nothing else.

Click the "Create Security Group" button and give the group a name and description. When it shows up in the list, click the name and you'll see two tabs towards the bottom of the screen. Click on the Inbound tab, which is where you create the security rules. You want to enable SSH and HTTP only at this point (you may choose to add more later).

Select "HTTP" from the dropdown and then click "Add Rule". You'll see the rule added to the right side of the panel.

Select "SSH" from the dropdown and click "Add Rule".

Click the "Apply Rule Changes" button to apply both of these rules.

Now this security group is ready for your new web server.

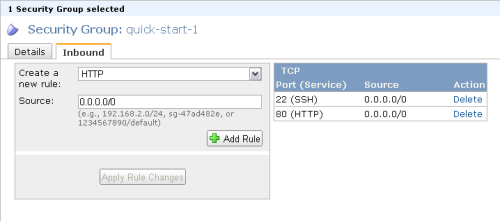

Create keypairs (1st time only)

On the same EC2 tab, there's an option on the lower-left called "Keypairs". Keypairs are used to secure your EC2 instance so that only you can access them. If you don't have an existing keypair to use, you can create a new one by clicking the "Create Keypair" button. This will prompt you for a name and then immediately start a file download of a file with .pem as its extension. Keep this file safe because you'll need it to access your EC2 instance.

Keep in mind that you will never be able to retrieve this .pem file if you lose it. You'll need to delete the keypair and create a new one.

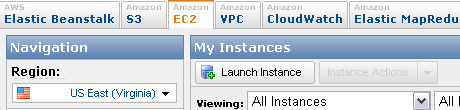

Create the virtual machine

Click the Instances option on the right side of the EC2 tab. Click the Launch Instance button after which you'll be asked to select which AMI to use. I always just use the first one, Basic Amazon Linux 32-bit AMI, though you may choose another if your needs are different.

If you don't have any special needs for this box, you can keep all of the defaults on the two Instance Details screens. The one you may want to change is the type of VM (Micro, Small, Large), depending on your memory and computing needs. When it comes to the screen for adding tags, just fill in the name with something that makes sense (i.e. "Test Server") so you can identify this instance in the AWS console.

The next steps are to to select the keypair and the security group. These should be the ones you already created previously (you can create new ones on the fly, but usually you won't need to).

The last screen has a button called "Launch", which will create and start up the VM. Watch the console to see when your VM is ready.

Setting up your virtual machine

Now that the VM is up and running, you can log in using the .pem file saved from creating the keypair. Amazon will automatically assign a domain name to the VM, which you can see by right-clicking on the instance in the AWS console and selecting the "Connect" menu option. This will show you to connect to the VM using a command similar to this:

ssh -i yourfile.pem ec2-user@ec2XX-YYY-ZZZ-X.compute-1.amazonaws.com

If all went well, you'll now be in the command prompt for the VM.The first thing to do is update yum:

sudo yum -y update

Both Apache and MySQL are already installed on the VM, so you don't need to do anything for those. If you want PHP and PHP support for MySQL, then run the following:

sudo yum install php

sudo yum install php-mysql

With those installed, it's now time to start Apache running this command:

sudo service httpd start

The root of your web server is in /var/www/html/, so just drop an index.html file into this directory and you should be able to access the site by typing in the name of your EC2 instance into a browser.

That's really all there is to it. You can now put additional files into /var/www/html/ and build up your site.

Set services to start automatically (optional)

If you plan on shutting down and starting up the VM on a regular basis, you may want to set Apache and/or MySQL to automatically when the system boots up. To ensure Apache automatically starts, use:

sudo /sbin/chkconfig httpd on

If you also want to start MySQL at boot time, run this:

sudo /sbin/chkconfig mysqld on

Now, both Apache and MySQL will start up when you start up the VM.

Wrap up

Creating new instances on Amazon EC2 is incredibly easy and fast when you need a development server in a hurry. The best part is that you pay only for what you use, so running a server for a few hours means paying a very low fee for that usage. I'm now in the habit of spinning up new servers that I may use for a day, or a few days, and then deleting them when I no longer need them. Having this flexibility is an incredibly powerful tool for development, and I hope this post helps you come to this same conclusion.

June 19, 2011

Book review: Eloquent JavaScript

I'd heard a lot about Eloquent JavaScript by Marijn Haverbeke over the past few months, and so I was greatly interested when asked if I would do a book review. The first thing that struck me about the book was completely visual: the book doesn't look scary or overwhelming at all. Indeed, everything about the design says "eloquent": the calming yellow, the simple bird, the length (less than 200 pages). Everything has been beautifully designed to get people over the hump of thinking the topic is unapproachable (I'll be the first to admit that some of my books look quite daunting on the shelf).

I'd heard a lot about Eloquent JavaScript by Marijn Haverbeke over the past few months, and so I was greatly interested when asked if I would do a book review. The first thing that struck me about the book was completely visual: the book doesn't look scary or overwhelming at all. Indeed, everything about the design says "eloquent": the calming yellow, the simple bird, the length (less than 200 pages). Everything has been beautifully designed to get people over the hump of thinking the topic is unapproachable (I'll be the first to admit that some of my books look quite daunting on the shelf).

This a good approach because Eloquent JavaScript is written for a unique crowd: people who don't know JavaScript and also don't know programming. The first thing you need such readers to understand is that this isn't a scary topic, and in this the book succeeds beautifully.

One of the keys to a good technical book is understanding the audience. Generally speaking, Eloquent JavaScript does a good job of addressing the specific audience it's intended for. Descriptions are simple, effective, and use plain language, though I'll admit the constant use of words like "things" and "stuff" make me cringe a bit. The discussions of concepts are generally correct though sometimes a bit more context would be helpful.

There are some subtle and not-so-subtle things that I would change about the book. First, the order of topics is sometimes confusing, especially given the intended audience. For example, I consider closures to be an advanced topic, but it's discussed in the book before the arguments object, the Math object, and recursion. Yes, closures are important in JavaScript, but introducing the topic before the reader has enough foundation to appreciate the complexity is setting them up for failure. This isn't to say the descriptions are wrong, just that I think the order is wrong.

The big thing I would change about this book are the examples. Coming up with relevant examples in technical books is extremely difficult, and something I struggle with all the time. The problem I have with the examples in Eloquent JavaScript is that they are so far away from what the beginner will be doing: tracking dead cats, creating a terrarium simulation, parsing a Windows INI file, etc. I prefer to teach people with examples that are at least in the vicinity of what they'll actually be doing. The first real mention of web programming doesn't even enter the conversation until Chapter 9.

To be fair, chapters 9-12 do a good job of discussing web programming and introducing some of the topics the reader would need to make use of their new-found knowledge. These chapters I enjoyed quite a bit and was disappointed that they were so short. The information was enough to get you started, but I felt like the author had more to say and just didn't have enough space to say it.

Overall, I think Eloquent JavaScript is a good book, suitable for those without experience in JavaScript and even those without programming experience. I wouldn't take this book on it's own, though, as I think it works best as a supplementary book to something like Jeremy Keith's iconic DOM Scripting. If you already know JavaScript, there isn't much new in this book for you.

Nicholas C. Zakas's Blog

- Nicholas C. Zakas's profile

- 106 followers