Nicholas C. Zakas's Blog, page 11

December 18, 2012

Now available: Principles of Object-Oriented Programming in JavaScript (beta)

Ever since I put together my Principles of Object-Oriented Programming in JavaScript class, I’ve been wanting to put together a resource that people who took the class could take home with them. I go through a lot of topics in the class and I didn’t think the slides would be enough to help people remember what was discussed. I thought about adding notes into the presentation, but that didn’t quite seem right either. After some thinking, I came to the conclusion that a book on the topics would be the best way to go. Kate Matsudaira made a compelling argument that I should start with an ebook and so here we are: Principles of Object-Oriented Programming in JavaScript.

Ever since I put together my Principles of Object-Oriented Programming in JavaScript class, I’ve been wanting to put together a resource that people who took the class could take home with them. I go through a lot of topics in the class and I didn’t think the slides would be enough to help people remember what was discussed. I thought about adding notes into the presentation, but that didn’t quite seem right either. After some thinking, I came to the conclusion that a book on the topics would be the best way to go. Kate Matsudaira made a compelling argument that I should start with an ebook and so here we are: Principles of Object-Oriented Programming in JavaScript.

This is the first time I’ve attempted to publish something by myself (other than the posts on my blog), and so I am still learning about the finer points of self-publishing. For example, this is the first time I’ve had to make legible diagrams. It may seem like a minor point but when you’re used to sketching things out with a pen and handing them to somebody to make a pretty diagram, it takes a little bit of adjusting. But then again, this is an entirely new experience with all kinds of new opportunities.

The book itself is intended to be focused on object-oriented programming in JavaScript. Specifically, how you create and modify objects. If you ever wanted to know why objects behave in certain ways or how inheritance really works, I’m hoping that this book answers those questions. Object-oriented programming is about more than inheritance and I’m hoping this book is considered a nice, concise guide to how objects work in JavaScript.

Because I’m focusing on JavaScript itself and not necessarily on the browser or Node.js, the book works as a learning tool regardless of where you’re writing JavaScript. The same basic concepts apply regardless of the JavaScript environment that you’re working in. There is no discussion of the DOM, or CommonJS modules, or anything other than pure ECMAScript 5 (and a few mentions of ECMAScript 6 for context).

The book is available in three ebook formats: PDF, Mobi, and ePub.

Why Leanpub?

The book is published through Leanpub. In researching options for ebook development, I found a lot of different solutions. Many of them required some hands-on work in order to generate the three formats that all ebooks need to reach the largest audience: PDF, Mobi, and ePub. I was looking for a solution that would generate the three formats automatically without me needing to do anything special.

I was also looking for a solution that would allow me to write the book in markdown. In the past year I’ve transitioned to writing everything in markdown and converting it into the appropriate formats afterward. This has greatly sped up my writing as I worry less about formatting and more about the content.

That I had to worry about how to sell the book. Should I open up a web store? What forms of payment will I accept? This is the part where I got stuck.

I believe it was Cody Lindley who first suggested that I take a look at Leanpub. After about 5 minutes, I was convinced that this was the right solution for me. Leanpub not only generates all three formats directly from markdown, but they also setup a nice-looking page where people can learn more about the book and purchase it.

Another area of concern for me was the ability to update the ebook whenever I wanted. When dealing with print books, I’ve always been frustrated at how long it takes to get fixes into the book. With ebooks, the process should be much faster, however how do you manage that process? Leanpub does that for you. I can just update the book when I’m ready and everyone will get notified that there is a new version. That means I can make fixes or even add new content and everyone who already purchased the ebook will be notified and able to download a new copy quickly.

You can shape this book

Leanpub has a theory about ebooks that I really like: you should release content early and often, gathering feedback from readers, and keep doing that until the book is in good enough shape to be considered final. While this makes a ton of sense for novels, where you can release a chapter each week, I felt like a technical book must be mostly complete before it’s ready to be shared with readers.

So that’s what I did, the ebook now contains all of the content I planned on writing. But that doesn’t have to be the end. If there are topics that seem like they are missing or things that aren’t being explained as well as they should be or places where a diagram would help, you can tell me that and I can fix it pretty quickly. Basically, as a reader of this ebook, you can shape what the final version of the book is going to contain.

You’ll notice that I have called this a beta version of the book. The content hasn’t been fully edited or tech edited yet, but I still want to share this with everyone to start getting feedback. At the moment, there are 90 pages that are jampacked with deep technical explanations of how JavaScript objects work. There could very well be more content that belongs in this book and I need you to tell me what that is. And as I said, once you purchase the ebook, you will get all future updates as well. I’m hoping that means an errata page won’t be necessary because I’ll be constantly fixing issues as they arise.

I’m aiming to have the book out of beta by the end of February 2013. That doesn’t mean there won’t continue to be updates after that point, just that I will consider it mostly “done” except for ongoing fixes.

Pay what you want

Another thing that I like about Leanpub is the ability to let the customer say what they would like to pay for the ebook. Thanks to everyone who suggested a price, I ended up with a range of $15-20. Most of the 400 people who responded suggested a price within that range (some also went as high as $100, which is wow, a lot for an ebook). So what I decided to do is set the suggested price at $19.99. If you feel that is too much for the ebook, you can pay less. If you feel like you want to support this project, you can pay more. I love giving this flexibility to readers.

Submit feedback

Since I’m publishing this on my own, I’ve set up a mailing list to gather feedback. You can actually use the mailing list for feedback on any of my books, but this is the only way to submit feedback for the ebook. You can also let me know if you like how this project turned out or any suggestions for making it better. I’m really looking forward to hearing your feedback. If this works out, I may do more ebooks in the future.

December 11, 2012

Are your mixins ECMAScript 5 compatible?

I was working with a client recently on a project that could make full use of ECMAScript 5 when I came across an interesting problem. The issue stemmed from the use of mixins, a very common pattern in JavaScript where one object is assigned properties (including methods) from another. Most mixin functions look something like this:

function mixin(receiver, supplier) {

for (var property in supplier) {

if (supplier.hasOwnProperty(property)) {

receiver[property] = supplier[property];

}

}

}

Inside of the mixin() function, a for loop iterates over all own properties of the supplier and assigns the value to the property of the same name on the receiver. Almost every JavaScript library has some form of this function, allowing you to write code like this:

mixin(object, {

name: "Nicholas",

sayName: function() {

console.log(this.name);

}

});

object.sayName(); // outputs "Nicholas"

In this example, object receives both the property name and the method sayName(). This was fine in ECMAScript 3 but doesn’t cover all the bases in ECMAScript 5.

The problem I ran into was with this pattern:

(function() {

// to be filled in later

var name;

mixin(object, {

get name() {

return name;

}

});

// let's just say this is later

name = "Nicholas";

}());

console.log(object.name); // undefined

This example looks a little bit contrived, but is an accurate depiction of the problem. The properties to be mixed in include an ECMAScript 5 accessor property with only a getter. That getter references a local variable called name that isn’t initialized to a variable and so receives the value of undefined. Later on, name is assigned a value so that the accessor can return a valid value. Unfortunately, object.name (the mixed-in property) always returns undefined. What’s going on here?

Look closer at the mixin() function. The loop is not, in fact, reassign properties from one object to another. It’s actually creating a data property with a given name and assigning it the returned by accessing that property on the supplier. For this example, mixin() effectively does this:

receiver.name = supplier.name;

The data property receiver.name is created and assigned the value of supplier.name. Of course, supplier.name has a getter that returns the value of the local name variable. At that point in time, name has a value of undefined, so that is the value stored in receiver.name. No getter is every created for receiver.name so the value never changes.

To fix this problem, you need to use property descriptors to properly mix properties from one object onto another. A pure ECMAScript 5 version of mixin() would be:

function mixin(receiver, supplier) {

Object.keys(supplier).forEach(function(value, property) {

Object.defineProperty(receiver, property, Object.getOwnPropertyDescriptor(supplier, property));

});

}

In this new version of the function, Object.keys() is used to retrieve an array of all enumerable properties on supplier. Then, the forEach() method is used to iterate over those properties. The call to Object.getOwnPropertyDescriptor() retrieves the descriptor for each property of supplier. Since the descriptor contains all of the relevant information about the property, including getters and setters, that descriptor can be passed directly into Object.defineProperty() to create the same property on receiver. Using this new version of mixin(), the problematic pattern from earlier in this post works as you would expect. The getter is correctly being transferred to receiver from supplier.

Of course, if you still need to support older browsers then you’ll need a function that falls back to the ECMAScript 3 way:

function mixin(receiver, supplier) {

if (Object.keys) {

Object.keys(supplier).forEach(function(value, property) {

Object.defineProperty(receiver, property, Object.getOwnPropertyDescriptor(supplier, property));

});

} else {

for (var property in supplier) {

if (supplier.hasOwnProperty(property)) {

receiver[property] = supplier[property];

}

}

}

}

If you’re using a mixin() function, be sure to double check that it works with ECMAScript 5, and specifically with getters and setters. Otherwise, you could find yourself running into errors like I did.

December 4, 2012

Adventures in pointerless computing

A few people know that I’ve been battling a repetitive stress injury (RSI) in both of my elbows. I’m hit on all sides of the elbow: tennis elbow, golfer’s elbow, and triceps tendinitis. I’m sure the stress has been building in these tendons for most of my career, but they really got bad last year once I left Yahoo. Being self-employed, I felt the need to work seven days a week and in all kinds of situations (coffee shops, dining room table, while watching TV, etc.) and, no big surprise, my arms started to rebel.

Since that time, I’ve made the appropriate adjustments to my work schedule and style. I no longer work directly on a laptop, instead using a laptop stand and separate keyboard. I favor working at home in my ergonomically setup office. I use Dragon Naturally Speaking to dictate almost every blog post, email, or other writing assignment (hence some funny typos, or I guess, speakos). I strictly stay off the computer on the weekends. I even ended up going to a physical therapist for a while. Unfortunately, the problem persists and has forced me to curtail my computing activity.

I had long since switched from a mouse to a trackball, which limits the range of motion my elbows need to make. Still, I felt like the movement from keyboard to trackball and back was placing undue stress on my right elbow. And so I decided to try computing without a pointing device. I unplugged the trackball so it wouldn’t tempt me and went on my way.

The first thing I did was to go about my normal activities and see where I got tripped up. Fortunately, Windows 7 is very keyboard accessible and so using the operating system itself is pretty easy. The search functionality from the Start menu quickly ended up being my primary way of starting applications and opening specific folders. I only need to press the Windows button on the keyboard and the search immediately comes up. Very useful.

I needed to acquaint myself with switching, minimizing, and maximizing windows on my desktop. As it turns out, these are all pretty easy:

Windows key + down arrow minimizes the current window if it’s not maximized. On maximized windows, the window gets restored.

Windows key + up arrow maximizes the current window.>/li>

Windows key + left/right arrow pins the window to either the right or left of the desktop, or removes the pin (based on the direction of the arrow).

Alt + F4 closes the current window.

Alt + spacebar opens the system menu for a window (the one with minimize, maximize, etc. – especially useful for pasting into a command prompt).

Of course, there’s also the old reliable Alt + Tab to switch between windows. I found that I needed to keep fewer windows open because it’s very frustrating to cycle through more than a few windows at a time. Toggling back and forth between two windows is nice and easy, but anything more quickly becomes a challenge.

Next I went to my web browser, Chrome, to learn how to navigate and debug (as is part of my daily routine). You’re probably already familiar with using Ctrl + T to open up a new tab regardless of the browser you’re using. Here are some of the other shortcuts I learned about:

Ctrl + W closes the current tab.

Ctrl + Shift + W closes all tabs (learned this by accident).

Ctrl + Shift + T reopen a previously closed tab.

Alt + D sets focus to the addressbar.

Alt + F opens the settings menu.

F6 switches focus between the address bar, any toolbars you have installed, and the webpage.

F12 toggles the developer tools while Ctrl + Shift + J always brings up the developer tools on the console tab.

One of my biggest fears about going pointer lists it was losing the ability to debug code. Fortunately, the Chrome developer tools have a lot of keyboard shortcuts[1] as well. I’m still making my way through those, trying to figure out the fastest way to accomplish what I’m trying to do. There are still some oddities, like trying to switch focus from the console to the source code and back, but generally the developer tools are very usable with keyboard shortcuts. I successfully set breakpoints and step through code without much trouble. Debugging CSS is something I’m still working on because no right-click means no Inspect Element.

I’m hopeful that my arms will recover and I’ll be able to go back to computing as normal, but in the meantime, I’m embracing this opportunity to learn more about how computers work when you can’t use a mouse. This whole experience has been a fantastic reminder that not everybody uses computers in the same way and small changes can make big differences.

References

Chrome Developer Tools Keyboard Shortcuts

November 27, 2012

Computer science in JavaScript: Quicksort

Most discussions about sorting algorithms tend to end up discussing quicksort because of its speed. Formal computer science programs also tend to cover quicksort[1] last because of its excellent average complexity of O(n log n) and relative performance improvement over other, less efficient sorting algorithms such as bubble sort and insertion sort for large data sets. Unlike other sorting algorithms, there are many different implementations of quicksort that lead to different performance characteristics and whether or not the sort is stable (with equivalent items remaining in the same order in which they naturally occurred).

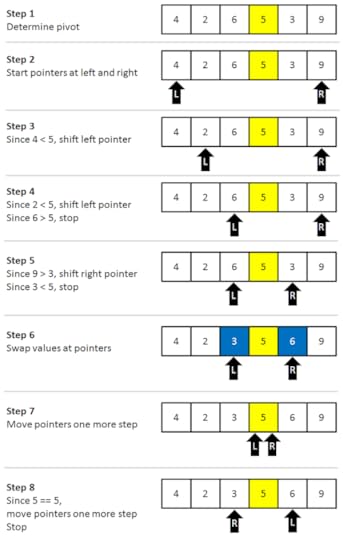

Quicksort is a divide and conquer algorithm in the style of merge sort. There are two basic operations in the algorithm, swapping items in place and partitioning a section of the array. The basic steps to partition an array are:

Find a “pivot” item in the array. This item is the basis for comparison for a single round.

Start a pointer (the left pointer) at the first item in the array.

Start a pointer (the right pointer) at the last item in the array.

While the value at the left pointer in the array is less than the pivot value, move the left pointer to the right (add 1). Continue until the value at the left pointer is greater than or equal to the pivot value.

While the value at the right pointer in the array is greater than the pivot value, move the right pointer to the left (subtract 1). Continue until the value at the right pointer is less than or equal to the pivot value.

If the left pointer is less than or equal to the right pointer, then swap the values at these locations in the array.

Move the left pointer to the right by one and the right pointer to the left by one.

If the left pointer and right pointer don’t meet, go to step 1.

As with many algorithms, it’s easier to understand partitioning by looking at an example. Suppose you have the following array:

var items = [4, 2, 6, 5, 3, 9];

There are many approaches to calculating the pivot value. Some algorithms select the first item as a pivot. That’s not the best selection because it gives worst-case performance on already sorted arrays. It’s better to select a pivot in the middle of the array, so consider 5 to be the pivot value (length of array divided by 2). Next, start the left pointer at position 0 in the right pointer at position 5 (last item in the array). Since 4 is less than 5, move the left pointer to position 1. Since 2 is less than 5, move the left pointer to position 2. Now 6 is not less than 5, so the left pointer stops moving and the right pointer value is compared to the pivot. Since 9 is greater than 5, the right pointer is moved to position 4. The value 3 is not greater than 5, so the right pointer stops. Since the left pointer is at position 2 and the right pointer is at position 4, the two haven’t met and the values 6 and 3 should be swapped.

Next, the left pointer is increased by one in the right pointer is decreased by one. This results in both pointers at the pivot value (5). That signals that the operation is complete. Now all items in the array to the left of the pivot are less than the pivot and all items to the right of the pivot are greater than the pivot. Keep in mind that this doesn’t mean the array is sorted right now, only that there are two sections of the array: the section where all values are less than the pivot and the section were all values are greater than the pivot. See the figure below.

The implementation of a partition function relies on there being a swap() function, so here’s the code for that:

function swap(items, firstIndex, secondIndex){

var temp = items[firstIndex];

items[firstIndex] = items[secondIndex];

items[secondIndex] = temp;

}

The partition function itself is pretty straightforward and follows the algorithm almost exactly:

function partition(items, left, right) {

var pivot = items[Math.ceil((right + left) / 2)],

i = left,

j = right;

while (i < pivot) {

i++;

}

while (items[j] > pivot) {

j--;

}

if (i

This function accepts three arguments: items, which is the array of values to sort, left, which is the index to start the left pointer at, and right, which is the index to start the right pointer at. The pivot value is determined by adding together the left and right values and then dividing by 2. Since this value could potentially be a floating-point number, it’s necessary to perform some rounding. In this case, I chose to use the ceiling function, but you could just as well use the floor function or round function instead. The i variable is the left pointer and the j variable is the right pointer.

The entire algorithm is just a loop of loops. The outer loop determines when all of the items in the array range have been processed. The two inner loops control movement of the left and right pointers. When both of the inner loops complete, then the pointers are compared to determine if the swap is necessary. After the swap, both pointers are shifted so that the outer loop continues in the right spot. The function returns the value of the left pointer because this is used to determine where to start partitioning the next time. Keep in mind that the partitioning is happening in place, without creating any additional arrays.

The quicksort algorithm basically works by partitioning the entire array, and then recursively partitioning the left and right parts of the array until the entire array is sorted. The left and right parts of the array are determined by the index returns after each partition operation. That index effectively becomes the boundary between the left and right parts of the array. In the previous example, the array becomes [4, 2, 3, 5, 6, 9] after one partition and the index returned is 4 (the last spot of the left pointer). After that, the left side of the overall array (items 0 through 3) is partitioned, as in the following figure.

After this pass, the array becomes [3, 2, 4, 5, 6, 9] and the index returned is 1. The heart rhythm continues like this until all of the left side of the array is sorted. Then the same processes followed on the right side of the array. The basic logarithm for quicksort then becomes very simple:

function quickSort(items, left, right) {

var index;

if (items.length > 1) {

index = partition(items, left, right);

if (left < index - 1) {

quickSort(items, left, index - 1);

}

if (index < right) {

quickSort(items, index + 1, right);

}

}

return items;

}

// first call

var result = quickSort(items, 0, items.length - 1);

The quicksort() function accepts three arguments, the array to sort, the index where the left pointer should start, and the index where the right pointer should start. To optimize for performance, the array isn’t sorted if it has zero or one items. If there are two or more items in the array then it is partitioned. If left is less than the returned index minus 1 then there are still items on the left to be sorted and quickSort() is called recursively on those items. Likewise, if index is less than the right pointer then there are still items on the right to sort. Once all this is done, the array is returned as the result.

To make this function a little bit more user-friendly, you can automatically fill in the default values for left and right if not supplied, such as:

function quickSort(items, left, right) {

var index;

if (items.length > 1) {

left = typeof left != "number" ? 0 : left;

right = typeof right != "number" ? items.length - 1 : right;

index = partition(items, left, right);

if (left < index - 1) {

quickSort(items, left, index - 1);

}

if (index < right) {

quickSort(items, index + 1, right);

}

}

return items;

}

// first call

var result = quickSort(items);

In this version of the function, there is no need to pass in initial values for left and right, as these are filled in automatically if not passed in. This makes the functional little more user-friendly than the pure implementation.

Quicksort is generally considered to be efficient and fast and so is used by V8 as the implementation for Array.prototype.sort() on arrays with more than 23 items. For less than 23 items, V8 uses insertion sort[2]. Merge sort is a competitor of quicksort as it is also efficient and fast but has the added benefit of being stable. This is why Mozilla and Safari use it for their implementation of Array.prototype.sort().

References

Quicksort (Wikipedia)

V8 Arrays Source Code (Google Code)

November 20, 2012

The Front End Summit new speaker program

One of the last things I did before leaving Yahoo! was to help organize the Front End Summit along with James Long and David Calhoun. This is (was?) a yearly internal front end conference that brought together engineers from all over the world. While not the same as planning a public conference, we faced many similar situations: we had to find speakers, we had to secure space for the conference (surprisingly hard, even though the company owned the space), and figure out how to get budget for everyone’s travel, food, and other expenses.

James, David, and I each came in with our own ideas about what was most important to achieve. My personal goal was to create a new speaker program to encourage inexperienced and brand new speakers to give talks. I had this goal for a couple of reasons. First, I strongly believe that giving talks (even small ones) is important to the professional growth of engineers. Second, Yahoo! had just lost some amazing speakers through attrition and I felt like it was important for us to replenish the corps.

In designing this program, I thought back to my early days of speaking and what would have helped me. Mentors are always an important part of any new experience, and so we had a mentorship program. I asked a bunch of experienced speakers to take on one or two inexperienced speakers to guide them through the process. The mentors were there to help go over slides, give feedback, give support for the random freakouts that might happen, organize rehearsals…basically, anything that would help the new speakers feel more comfortable. Any speaker could ask for a mentor to help them, and it was up to the mentor and speaker to work out the best way to work with each other. Some chose to meet weekly to go over their progress, others communicated primarily via email; the mentorship was what they each wanted out of it rather than a rigid protocol.

If you chose to have a mentor, then you were obligated to attend two speaker training sessions (those without mentors were welcome to attend as well). The sessions were designed to go over general knowledge that everyone should have. Jenny Donnelly presented the first session, which was a combination of logistical insights (i.e., how to deal with lapel mics and washed-out projectors) as well as tips of how to design slides and speak clearly. The second session was an improv class. We actually didn’t tell anyone that’s what we were doing for fear that some may not show up. We hired an excellent outside guy to do the two-hour improv workshop designed to put people at ease in front of crowds. This was a huge hit – everyone who participated felt like it helped them tremendously. On top of it, we all got to act silly at work. If you want to improve your speaking and have never taken an improv class, I can’t recommend it enough.

The last part was the hardest: finding the new speakers. Since it was our stated goal to include as many new speakers as possible that meant doing a lot of outreach. James, David, and I had a session where we made two lists: the people we wanted to speak and the topics we wanted to include. Luckily for us, we were working at Yahoo! and there was no shortage of smart engineers. We took care to identify men and women, as well as engineers from other Yahoo! offices. The list of topics was important because the most common concern potential new speakers mention is usually not knowing what to talk about. We wanted to have a ready-made list of topics to give them when that concern popped up. Basically, we didn’t want to give smart people any excuse to not take this step.

I personally approached several of the people on the list, both men and women. I approach them with the same story: you are incredibly talented and do great work, and I think everyone would love to hear what you have to say. The men I was able to convince reasonably quickly to take a shot once I explained the logistics. The women, on the other hand, took a little more time to convince. Whereas the men would give me a response during that initial conversation, the women often asked for more time to think about it. In some cases, I would end up meeting with the women a second time to try to talk them into it. I mention this not because I thought there was anything wrong with how either gender responded, just that there was a very significant difference between how they responded and I think that’s worth noting. The lesson I learned is that I had to approach women differently than men to achieve the same result. And that’s okay.

For both men and women, there were some people that I was just unable to convince. However, the overall rate of success when approaching people directly was pretty high. That’s also worth noting for anyone trying to plan a conference.

We also accepted submissions from others because we wanted to include as many people as possible. Those that we invited were asked to still submit a formal proposal so that they got used to doing so. That’s something that I think is important: to give new speakers a safe and supportive way of going through the process of submitting a proposal. Getting new speakers through the entire process of proposal to practicing to speaking gives them far more confidence than anything else.

And the results? The two-day event was fantastic. All of the new speakers did incredibly well, and to be honest, every single one exceeded my expectations. I wish that my first talk went as smoothly as some of theirs did. They all received good to great ratings on their talks and each new speaker said that they were very likely to speak again in the future. And that was really what we were after. I told each new speaker that my goal wasn’t to get them to love speaking, it was to get them to not hate or fear it. I wanted those new speakers to know that they could give a talk just like anyone else if they put some work into it.

I bring up this experience because there’s been a lot of talk over the past couple of days about conferences and how they choose their speakers. What I learned in my experience is that getting a diverse set of speakers can take a little extra work but it’s not impossible, and the conference is better off for it. I’ve read various opinions where one group says that opening up a request for proposals is the only fair way to get speakers where another says that the only fair way is to invite every speaker specifically. I prefer to do both because each way biases you towards a particular group. An open request for proposals biases you towards people who hear about your conference and feel confident enough to submit a proposal; only inviting speakers biases you to people that you’ve heard of. I think the ideal conference is made up of a mix of those two groups as well as experienced and inexperienced.

Above all, though, what I would like people to take away from this post is that there isn’t a shortage of speakers in the world. Once you get past experienced speakers, you can create new ones from the remaining people. While I realize the logistical issues are different for a public conference than an internal conference, I wish that more conferences would offer some sort of mentorship program to inexperienced speakers.

I want to hear new speakers. Getting them to submit proposals is a great first step, but where is the support system to help them succeed? The goal shouldn’t be just to get new speakers on stage, but to convert new speakers into recurring speakers because they enjoyed the experience. I’m still overcome with pride when I see some of the engineers who took part in the new speaker program at Yahoo! going off and giving talks at meetups and conferences. Public speaking is an important skill, especially for engineers who spend much of their time not effectively communicating with others.

If you, your company, or your conference are interested in setting up a speaker training program like this, please contact me.

November 13, 2012

JavaScript APIs you’ve never heard of (and some you have)

This week I was scheduled to give a brand new talk at YUIConf entitled, JavaScript APIs you’ve never heard of (and some you have). Unfortunately, a scheduling conflict means that I won’t be able to attend. So instead of letting the work of putting together a brand-= new talk go to waste (or otherwise be delayed) I decided to put together a screencast of the talk. This is my first time doing a screencast so I would love some feedback. Here’s the description of the talk:

The number of JavaScript APIs has exploded over the years, with a small subset of those APIs getting all the attention. While developers feverishly work on Web sockets and canvas, it’s easy to overlook some smaller and quite useful APIs. This talk uncovers the “uncool” JavaScript APIs that most people have never heard of and yet are widely supported by today’s browsers. You’ll learn tips and tricks for working with the DOM and other types of data that you can use today.

The screencast is embedded below and the slides are available on Slideshare.

(Yes, my voice is a bit hoarse.)

November 6, 2012

ECMAScript 6 collections, Part 3: WeakMaps

Weakmaps are similar to regular maps in that they map a value to a unique key. That key can later be used to retrieve the value it identifies. Weakmaps are different because the key must be an object and cannot be a primitive value. This may seem like a strange constraint but it’s actually the core of what makes weakmaps different and useful.

A weakmap holds only a weak reference to a key, which means the reference inside of the weakmap doesn’t prevent garbage collection of that object. When the object is destroyed by the garbage collector, the weakmap automatically removes the key-value pair identified by that object. The canonical example for using weakmaps is to create an object related to a particular DOM element. For example, jQuery maintains a cache of objects internally, one for each DOM element that has been referenced. Using a weakmap would allow jQuery to automatically free up memory associated with a DOM element when it is removed from the document.

The ECMAScript 6 WeakMap type is an unordered list of key-value pairs where the key must be a non-null object and the value can be of any type. The interface for WeakMap is very similar to that of Map in that set() and get() are used to add data and retrieve data, respectively:

var map = new WeakMap(),

element = document.querySelector(".element");

map.set(element, "Original");

// later

var value = map.get(element);

console.log(value); // "Original"

// later still - remove reference

element.parentNode.removeChild(element);

element = null;

value = map.get(element);

console.log(value); // undefined

In this example, one key-value pair is stored. The key is a DOM element used to store a corresponding string value. That value was later retrieved by passing in the DOM element to get(). If the DOM element is then removed from the document and the variable referencing it is set to null, then the data is also removed from the weakmap and the next attempt to retrieve data associated with the DOM element fails.

This example is a little bit misleading because the second call to map.get(element) is using the value of null (which element was set to) rather than a reference to the DOM element. You can’t use null as a key in weakmaps, so this code isn’t really doing a valid lookup. Unfortunately, there is no part of the interface that allows you to query whether or not a reference has been cleared (because the reference no longer exists).

Note: The weakmap set() method will throw an error if you try to use a primitive value as a key. If you want to use a primitive value as a key, then it’s best to use Map instead.

Weakmaps also have has() for determining if a key exists in the map and delete() for removing a key-value pair.

var map = new WeakMap(),

element = document.querySelector(".element");

map.set(element, "Original");

console.log(map.has(element)); // true

console.log(map.get(element)); // "Original"

map.delete(element);

console.log(map.has(element)); // false

console.log(map.get(element)); // undefined

Here, a DOM element is once again used as the key in a weakmap. The has() method is useful for checking to see if a reference is currently being used as a key in the weakmap. Keep in mind that this only works when you have a non-null reference to a key. The key is forcibly removed from the weakmap by using delete(), at which point has() returns false and get() returned undefined.

Browser Support

Both Firefox and Chrome have implemented WeakMap, however, in Chrome you need to manually enable ECMAScript 6 features: go to chrome://flags and enable "Experimental JavaScript Features". Both implementations are complete per the current strawman[1] specification (though the current ECMAScript 6 spec also defines a clear() method).

Uses and Limitations

Weakmaps have a very specific use case in mind, and that is mapping values to objects that might disappear in the future. The ability to free up memory related to these objects is useful for JavaScript libraries that wrap DOM elements with custom objects such as jQuery and YUI. There’ll likely be more use cases discovered once implementations are complete and widespread, but in the short term, don’t feel bad if you can’t figure out a good spot for using weakmaps.

In many cases, a regular map is probably what you want to use. Weakmaps are limited in that they aren’t enumerable and you can’t keep track of how many items are contained within. There also isn’t a way to retrieve a list of all keys. If you need this type of functionality, then you’ll need to use a regular map. If you don’t, and you only intend to use objects as keys, then a weakmap may be the right choice.

References

WeakMaps Strawman (ECMA)

October 30, 2012

The “thank you” that changed my life

There’s so much rampant negativity in the world and on the Internet that it can be hard to deal with some days. It seems like more and more, I’m seeing people being mean and succeeding, and that makes me sad. Perhaps the biggest poster child for this was Steve Jobs, who by all accounts was a really big jerk.[1] In one way or another, he seemed to legitimize being an asshole as a good way to do business. And I’ve seen this even more now that I’m involved in startup life.

A situation recently popped up in my life where I had a decision to make. I could do what “everyone else does”, tell a lie, and end up with a bunch of money. Or, I could tell the truth, and never see a cent. Perhaps because of some abnormal wiring in my brain, the thought of lying didn’t even register as a realistic choice. I was told, “but this is how things are done.” I didn’t care. That’s not the way that I do things.

I began searching for examples of where being nice and polite actually worked out in business or otherwise. An opportunity where it would have been easy to be mean but being nice changed the result. After struggling to do research and thinking about stories I’ve heard, I came to realize that the best story is my own.

Back in 2003, I was working in a nondescript job that I hated. I was going on year two of an almost unbearable four years at this job and needed a creative outlet. I had started writing articles for several online sites and had gotten the idea to write a book. I wrote every day for about six months straight trying to figure out what this book would be like and what the focus would be. I knew it would be on JavaScript, more specifically all the stuff people didn’t understand, but I really wasn’t sure of the title or the outline or who I would propose the book to. All I knew was that I wanted to write about JavaScript and so that’s what I did.

After that six months, I had enough material to put together a rough outline and start proposing the book to publishers. My first choice was Sitepoint. I had written several articles for their website and they were just starting to publish books. I thought a book on JavaScript would fit in great with what they were trying to do. So I sent over a proposal with a writing sample and anxiously awaited a response. Not too long later, I got a rejection e-mail. And it wasn’t just a rejection e-mail, the person who wrote the e-mail not only didn’t like my idea for the book, he said he didn’t understand why anybody would ever want such a book and also that my writing style was terrible. This was quite a blow to me and my ego, but keeping with what I had been taught growing up, I wrote back to him and thanked him for the feedback. I asked if he could give me any advice on how to improve the book or my writing style. I heard nothing back.

I next approached Apress. At the time, Apress was just getting started with web development books and I was hopeful that they would be interested in a JavaScript book. My proposal was accepted and somebody started to review it. After a couple of months without hearing anything back, I e-mailed this person only to have the e-mail bounce back. Not a good sign. I dug around on the Apress website and found another editor’s email. I e-mailed him and explained the situation: someone was reviewing my proposal and now it appears that he doesn’t work there anymore. I inquired if anybody was looking at it now, and if not, if it would be possible to assign someone. He apologized for the inconvenience and assigned somebody else to review my proposal.

That someone else was John Franklin, a really nice guy who spent some time looking over my proposal and researching potential. After another couple of months, John finally got back to me and said that Apress was going to pass on the project. They felt that the JavaScript book market was already dominated by O’Reilly and Wrox and they were not interested in going head-to-head with them (particularly ironic given the number of JavaScript titles that were later published by Apress). I was disappointed because I felt like there was room for more JavaScript books in the market and they were missing an opportunity. As this was my second rejection, I was a little bit down. Still, I wrote back to John and said thank you for taking the time to review my proposal and for giving me his honest assessment.

Much to my surprise, John wrote back to me. He said that he personally thought that the book was a good idea and that I might be better off going with a larger publisher that might have the resources to pull it off. He gave me the name and contact information for Jim Minatel, an acquisitions editor at Wrox. I had never thought to contact Wrox because they already had several JavaScript books including the original Professional JavaScript by the late Nigel McFarlane.

I e-mailed Jim and introduced myself. It just so happened that he was looking for somebody to rewrite Professional JavaScript from scratch. Jim and I worked together to merge my proposal into his idea for the book and the end result was Professional JavaScript for Web Developers, my first book, which was released in 2005. What happened over the next several years is something that I still can’t believe.

The first interesting thing occurred when I got an e-mail from Eric Miraglia at Yahoo!. He let me know that Yahoo! was using my book to train their engineers on JavaScript. This was really exciting for me, because I had been a longtime Yahoo! user and knew how big the company was. Eric said to let him know if I’m ever in California, because he’d like to meet and show me around. I thanked Eric and told him I wasn’t planning any California trips soon, but I would definitely keep that in mind.

Because of the success of Professional JavaScript for Web Developers, Jim contacted me soon after to ask if I would write a book on Ajax. The Ajax revolution was just starting and Jim wanted to get out in front of it with a book. I initially turned it down because I was burned out on writing and the schedule he was proposing was really aggressive. However, he was eventually able to convince me to do it and Professional Ajax was released in 2006. It turned out to be the second Ajax book on the market and ended up being one of Amazon’s top 10 computer and technology books of 2006.[2]

The success of Professional Ajax was overwhelming. The book put me on the radar for Google, who came calling asking if I would like to work for them. Google was in a big hiring spree, bringing in top tier web developers from around the world. At the time I was still living in Massachusetts and the thought of moving to California wasn’t one that I relished (Google didn’t have the Cambridge office at that point in time). But I saw this as an opportunity I couldn’t pass up and accepted their invitation to fly out and interview.

At the same time, Jim came ringing again asking to update Professional Ajax for the next year. With all of the excitement, the Ajax book market was exploding as people discovered new and interesting ways to use this new technology.

While I was out in California interviewing with Google, I emailed Eric and asked if he would like to get together for drinks. I met with him and Thomas Sha at Tied House in Mountain View. We talked about the current state of the web and how exciting it was to be a web developer working with JavaScript and Ajax. We also talked a little bit about what was going on at Yahoo! at the time. When I got back to Massachusetts, Thomas called and asked if I would be interested in interviewing at Yahoo! as well. After all, he said, if you’re going to move all the way across the country you might as well know what your options are.

I ended up choosing to work for Yahoo! instead of Google and moved to California. I can’t say enough about my time at Yahoo! and how much I enjoyed it. I met so many great people that I can’t even begin to list. However, there are a few that stick out as I look back.

I met Bill Scott through my cubemate, Adam Platti. I had mentioned to Adam that I wanted to start giving talks and I didn’t know how to go about it. Adam said that his friend Bill did talks all the time and I should chat with him to figure out how to do it. He then made an introduction to Bill, and Bill made an introduction to the organizer of the Rich Web Experience, which was taking place in San Jose. That was my first conference speaking opportunity. The experience made me realize that not only could I give a talk, but people actually liked it. From then on, I was giving talks at conferences and other events.

I met Nate Koechley through Eric and Thomas when I arrived in California. Nate gave an introductory class to all new front-end engineers at Yahoo! that I was in and really enjoyed. Over the years, I would get to see him give several talks, and he more than anyone else influenced my speaking style. I loved how visual his slides were and how we could explain complex topics by breaking them down into small chunks. He also had great interactions with the audience, never getting flustered and always being both personable and respectful. I was fortunate to have Nate in some of my talk rehearsals and was the beneficiary of a lot of great feedback from him.

I met Havi Hoffman through email. At the time, she was working for the Yahoo! Developer Network and was looking for somebody to write a book. Yahoo! was just starting a partnership with O’Reilly to have Yahoo! Press-branded books and someone had written a proposal for a book called, High Performance JavaScript. I still to this day don’t know who wrote the original proposal, but that person was unavailable to write the book and so Havi had contacted me to see if I was interested. Havi introduced me to Mary Treseler at O’Reilly, and we all worked to get the book out in 2010.

High Performance JavaScript was also a hit. The time was right for a book on JavaScript performance, and people really liked it. The success of the book led to more speaking engagements which in turn led to requests for more books. In 2012, I proposed Maintainable JavaScript to Mary as a new title, and it was published later in the year. That was after the third edition of Professional JavaScript for Web Developers was released in January 2012.

The success of my books and speaking engagements led me to leave Yahoo! in 2011 to do two things: start a consulting business and attempt to create a Silicon Valley startup with some former colleagues from Yahoo!. Because people knew who I was, it was fairly easy to get consulting work. That was important because we were bootstrapping the start up (WellFurnished) and we would all be chipping in our own money to get it off the ground.

Today, I have the career that I couldn’t even have dreamed of coming out of college. Being able to work for myself, do the things that I love, and still have time to write and give talks is truly a blessing. And all of it, every single piece, can be traced back to a simple “thank you” I emailed to John Franklin in 2004. If I hadn’t sent that e-mail, I wouldn’t have been introduced to Jim Minatel, which means I wouldn’t have written Professional JavaScript for Web Developers, which means Yahoo! would never have started using it and I never would have written Professional Ajax, which means I never would have been interviewed by Google, which means I never would have met Eric Miraglia and Thomas She, which means I never would have worked at Yahoo!, which means I never would have met Adam Platti, Bill Scott, Nate Koechley, or Havi Hoffman, which means I never would have started giving talks or writing for O’Reilly, which means I never would have been able to start a consulting business, which means I never would have been able to attempt a startup.

My life was taken on a completely different path just by being nice to somebody. The truth is, you never know when that one moment of being nice will turn into a life altering moment. Amazing things can happen when you don’t push people away with negativity. So, embrace every opportunity to be nice, say please when asking for things, and above all, never forget to say “thank you” when someone has helped you.

References

Be a Jerk: The Worst Business Lesson From the Steve Jobs Biography (The Atlantic)

Best Books of 2006 -

Top 10 Editors’ Picks: Computers & Internet (Amazon)

October 19, 2012

Book review: Think Like a Programmer

I was excited to get a copy of Think Like a Programmer for review. The subtitle is, “an introduction to creative problem solving,” which is something that I think is very important to being a good software engineer. I’ve talked a lot to younger engineers about thinking critically to solve problems and not just relying on prescribed solutions all the time. I was truly hoping that this book would be one I could recommend to software engineers looking to take the next step.

I was excited to get a copy of Think Like a Programmer for review. The subtitle is, “an introduction to creative problem solving,” which is something that I think is very important to being a good software engineer. I’ve talked a lot to younger engineers about thinking critically to solve problems and not just relying on prescribed solutions all the time. I was truly hoping that this book would be one I could recommend to software engineers looking to take the next step.

The first chapter talks about problem-solving strategies and is pure gold. It talks about classic puzzles that were made famous as interview questions at places like Microsoft and Google. There are a bunch of interesting problems to look at, and a great discussion of how to solve the problems. The author gives a lot of great advice on how to solve difficult problems which break down to always having a plan, restating the problem until it makes sense, dividing the problem into smaller problems, starting with what you know, reducing the problem to a simpler problem first, looking for analogies, and experimenting to see how close you are getting. This first chapter needs to be read by anyone who wants to improve their problem-solving skills. I’ve never seen the process of problem-solving broken down so well as I did in this chapter. It really made me look forward to the rest of the book.

Unfortunately, the book very quickly turned into an introductory programming book. Chapter 2 jumps right in with C++ examples and the rest of the book is pretty much about solving simple problems in C++. Unfortunately, because C++ is quite a unique language, a lot of the lessons learned aren’t directly applicable in other, higher-level languages. After chapter 1, this book basically becomes another introduction to programming book focused on C++. The sort of problems focused on are the kinds of problems you would look at in a computer science course.

I found the dramatic change from chapter 1 to the rest of the chapters frustrating, because chapter 1 was truly unique and not at all language-specific. I was hoping this book would be about problem solving, a guide for non-programmers as well as programmers, and what I found was a chapter on problem solving and the book on learning the basics of C++. That’s not to say that it doesn’t give a good job teaching things like how to use pointers and why linked lists are useful, but for somebody who has already been in the industry and already graduated from a computer science program, these are really just reviews the fundamentals and not all that interesting.

So, if you didn’t take C++ in high school or college and want exposure to some basic constructs and approaches, then you are a good candidate for this book. Anyone with even a little bit of experience will probably not get much out of this book past chapter 1. It’s unfortunate, because I think the author really hit on a great topic in that first chapter and I would’ve loved an entire book that delves more deeply into the problem-solving process.

October 16, 2012

Does JavaScript need classes?

Like it or not, ECMAScript 6 is going to have classes[1]. The concept of classes in JavaScript has always been polarizing. There are some who love the classless nature of JavaScript specifically because it is different than other languages. On the other hand, there are those who hate the classless nature of JavaScript because it’s different than other languages. One of the biggest mental hurdles people need to jump when moving from C++ or Java to JavaScript is the lack of classes, and I’ve had people explain to me that this was one of the reasons they either didn’t like JavaScript or decided not to continue learning.

JavaScript hasn’t had a formal definition of classes since it was first created and that has caused confusion right from the start. There are no shortage of JavaScript books and articles talking about classes as if they were real things in JavaScript. What they refer to as classes are really just custom constructors used to define custom reference types. Reference types are the closest thing to classes in JavaScript. The general format is pretty familiar to most developers, but here’s an example:

function MyCustomType(value) {

this.property = value;

}

MyCustomType.prototype.method = function() {

return this.property;

};

In many places, this is code is described as declaring a class named MyCustomType. In fact, all it does is declare a function named MyCustomType that is intended to be used with new to create an instance of the reference type MyCustomType. But there is nothing special about this function, nothing that says it’s any different from any other function that is not being used to create a new object. It’s the usage of the function that makes it a constructor.

The code doesn’t even look like it’s defining a class. In fact, there is very little obvious relationship between the constructor definition and the one method on the prototype. These look like to completely separate pieces of code to new JavaScript developers. Yes, there’s an obvious relationship between the two pieces of code, but it doesn’t look anything like defining a class in another language.

Even more confusing is when people start to talk about inheritance. Immediately they start throwing around terms such as subclassing and superclasses, concepts that only make sense when you actually have classes to work with. Of course, the syntax for inheritance is equally confusing and verbose:

function Animal(name) {

this.name = name;

}

Animal.prototype.sayName = function() {

console.log(this.name);

};

function Dog(name) {

Animal.call(this, name);

}

Dog.prototype = new Animal(null);

Dog.prototype.bark = function() {

console.log("Woof!");

};

The two-step inheritance process of using a constructor and overriding a prototype is incredibly confusing.

In the first edition of Professional JavaScript for Web Developers, I used the term “class” exclusively. The feedback I received indicated that people found this confusing and so I changed all references to “class” in the second edition to “type”. I’ve used that terminology ever since and it helps to eliminate a lot of the confusion.

However, there is still a glaring problem. The syntax for defining custom types is confusing and verbose. Inheritance between two types is a multistep process. There is no easy way to call a method on a supertype. Bottom line: it’s a pain to create and manage custom types. If you don’t believe that this is a problem, just look at the number of JavaScript libraries that have introduced their own way of defining custom types, inheritance, or both:

YUI – has Y.extend() to perform inheritance. Also adds a superclass property when using this method.[2]

Prototype – has Class.create() and Object.extend() for working with objects and “classes”.[3]

Dojo – has dojo.declare() and dojo.extend().[4]

MooTools – has a custom type called Class for defining and extending classes.[5]

It’s pretty obvious that there’s a problem when so many JavaScript libraries are defining solutions. Defining custom types is messy and not at all intuitive. JavaScript developers something better than the current syntax.

ECMAScript 6 classes are actually nothing more than syntactic sugar on top of the patterns you are already familiar with. Consider this example:

class MyCustomType {

constructor(value) {

this.property = value;

}

method() {

return this.property;

}

}

This ECMAScript 6 class definition actually desugars to the previous example in this post. An object created using this class definition works exactly the same as an object created using the constructor definition from earlier. The only difference is a more compact syntax. How about inheritance:

class Animal {

constructor(name) {

this.name = name;

}

sayName() {

console.log(this.name);

}

}

class Dog extends Animal {

constructor(name) {

super(name);

}

bark() {

console.log("Woof!");

}

}

This example desugars to the previous inheritance example. The class definitions are compact and the clunky multistep inheritance pattern has been replaced with a simple extends keyword. You also get the benefit of super() inside of class definitions so you don’t need to reference the supertype in more than one spot.

All of the current ECMAScript 6 class proposal is simply new syntax on top of the patterns you already know in JavaScript. Inheritance works the same as always (prototype chaining plus calling a supertype constructor), methods are added to prototypes, and properties are declared in the constructor. The only real difference is less typing for you (no pun intended). Class definitions are just type definitions with a different syntax.

So while some are having a fit because ECMAScript 6 is introducing classes, keep in mind that this concept of classes is abstract. It doesn’t fundamentally change how JavaScript works; it’s not introducing a new thing. Classes are simply syntactic sugar on top of the custom types you’ve been working with for a while. This solves a problem that JavaScript has had for a long time, which is the verbosity and confusion of defining your own types. I personally would have liked to use the keyword type instead of class, but at the end of the day, this is just a matter of semantics.

So does JavaScript need classes? No, but JavaScript definitely needs a cleaner way of defining custom types. It just so happens the way to do that has a name of “class” in ECMAScript 6. And if that helps developers from other languages make an easier transition into JavaScript, then that’s a good thing.

References

Maximally minimal classes (ECMA)

YUI extend() (YUILibrary)

Prototype Classes and Inheritance (Prototype)

Creating and Enhancing Dojo Classes (SitePen)

MooTools Class (MooTools)

Nicholas C. Zakas's Blog

- Nicholas C. Zakas's profile

- 106 followers