Nicholas C. Zakas's Blog, page 7

April 29, 2014

Creating type-safe properties with ECMAScript 6 proxies

In my last post, I explained how to use ECMAScript 6 proxies to throw an error when a non-existent property is read (rather than returning undefined). I came to realize that proxies allow a transparent way to augment objects with validation capabilities in an almost limitless fashion. After some experimentation, I discovered that it’s possible to add type safety to JavaScript objects with just a few lines of code.

The idea behind type safety is that each variable or property can only contain a particular type of value. In type-safe languages, the type is defined along with the declaration. In JavaScript, of course, there is no way to make such a declaration natively. However, many times properties are initialized with a value that indicates the type of data it should contain. For example:

var person = {

name: "Nicholas",

age: 16

};

In this code, it’s easy to see that name should hold a string and age should hold a number. You wouldn’t expect these properties to hold other types of data for as long as the object is used. Using proxies, it’s possible to use this information to ensure that new values assigned to these properties are of the same type.

Since assignment is the operation to worry about (that is, assigning a new value to a property), you need to use the proxy set trap. The set trap gets called whenever a property value is set and receives four arguments: the target of the operation, the property name, the new value, and the receiver object. The target and the receiver are always the same (as best I can tell). In order to protect properties from having incorrect values, simply evaluate the current value against the new value and throw an error if they don’t match:

function createTypeSafeObject(object) {

return new Proxy(object, {

set: function(target, property, value) {

var currentType = typeof target[property],

newType = typeof value;

if (property in target && currentType !== newType) {

throw new Error("Property " + property + " must be a " + currentType + ".");

} else {

target[property] = value;

}

}

});

}

The createTypeSafeObject() method accepts an object and creates a proxy for it with a set trap. The trap uses typeof to get the type of the existing property and the value that was passed in. If the property already exists on the object and the types don’t match, then an error is thrown. If the property either doesn’t exist already or the types match, then the assignment happens as usual. This has the effect of allowing objects to receive new properties without error. For example:

var person = {

name: "Nicholas"

};

var typeSafePerson = createTypeSafeObject(person);

typeSafePerson.name = "Mike"; // succeeds, same type

typeSafePerson.age = 13; // succeeds, new property

typeSafePerson.age = "red"; // throws an error, different types

In this code, the name property is changed without error because it’s changed to another string. The age property is added as a number, and when the value is set to a string, an error is thrown. As long as the property is initialized to the proper type the first time, all subsequent changes will be correct. That means you need to initialize invalid values correctly. The quirk of typeof null returning “object” actually works well in this case, as a null property allows assignment of an object value later.

As with defensive objects, you can also apply this method to constructors:

function Person(name) {

this.name = name;

return createTypeSafeObject(this);

}

var person = new Person("Nicholas");

console.log(person instanceof Person); // true

console.log(person.name); // "Nicholas"

Since proxies are transparent, the returned object has all of the same observable characteristics as a regular instance of Person, allowing you to create as many instances of a type-safe object while making the call to createTypeSafeObject() only once.

Conclusion

By allowing you to get in the middle of assignment operations, proxies enable you to intercept the value and validate it appropriately. The examples in this post use the simple type returned by typeof to determine the correct type for a property, but you could just as easily add custom validation. The important takeaway is how proxies enable you to build guarantees into your objects without affecting normal functionality. The ability to intercept values and throw errors when they are incorrect can greatly reduce errors based one assigning the wrong type of data to a property.

April 28, 2014

Creating type-safe properties with ECMAScript 6 proxies

In my last post, I explained how to use ECMAScript 6 proxies to throw an error when a non-existent property is read (rather than returning undefined). I came to realize that proxies allow a transparent way to augment objects with validation capabilities in an almost limitless fashion. After some experimentation, I discovered that it’s possible to add type safety to JavaScript objects with just a few lines of code.

The idea behind type safety is that each variable or property can only contain a particular type of value. In type-safe languages, the type is defined along with the declaration. In JavaScript, of course, there is no way to make such a declaration natively. However, many times properties are initialized with a value that indicates the type of data it should contain. For example:

var person = {

name: "Nicholas",

age: 16

};

In this code, it’s easy to see that name should hold a string and age should hold a number. You wouldn’t expect these properties to hold other types of data for as long as the object is used. Using proxies, it’s possible to use this information to ensure that new values assigned to these properties are of the same type.

Since assignment is the operation to worry about (that is, assigning a new value to a property), you need to use the proxy set trap. The set trap gets called whenever a property value is set and receives four arguments: the target of the operation, the property name, the new value, and the receiver object. The target and the receiver are always the same (as best I can tell). In order to protect properties from having incorrect values, simply evaluate the current value against the new value and throw an error if they don’t match:

function createTypeSafeObject(object) {

return new Proxy(object, {

set: function(target, property, value) {

var currentType = typeof target[property],

newType = typeof value;

if (property in target && currentType !== newType) {

throw new Error("Property " + property + " must be a " + currentType + ".");

} else {

target[property] = value;

}

}

});

}

The createTypeSafeObject() method accepts an object and creates a proxy for it with a set trap. The trap uses typeof to get the type of the existing property and the value that was passed in. If the property already exists on the object and the types don’t match, then an error is thrown. If the property either doesn’t exist already or the types match, then the assignment happens as usual. This has the effect of allowing objects to receive new properties without error. For example:

var person = {

name: "Nicholas"

};

var typeSafePerson = createTypeSafeObject(person);

typeSafePerson.name = "Mike"; // succeeds, same type

typeSafePerson.age = 13; // succeeds, new property

typeSafePerson.age = "red"; // throws an error, different types

In this code, the name property is changed without error because it’s changed to another string. The age property is added as a number, and when the value is set to a string, an error is thrown. As long as the property is initialized to the proper type the first time, all subsequent changes will be correct. That means you need to initialize invalid values correctly. The quirk of typeof null returning “object” actually works well in this case, as a null property allows assignment of an object value later.

As with defensive objects, you can also apply this method to constructors:

function Person(name) {

this.name = name;

return createTypeSafeObject(this);

}

var person = new Person("Nicholas");

console.log(person instanceof Person); // true

console.log(person.name); // "Nicholas"

Since proxies are transparent, the returned object has all of the same observable characteristics as a regular instance of Person, allowing you to create as many instances of a type-safe object while making the call to createTypeSafeObject() only once.

Conclusion

By allowing you to get in the middle of assignment operations, proxies enable you to intercept the value and validate it appropriately. The examples in this post use the simple type returned by typeof to determine the correct type for a property, but you could just as easily add custom validation. The important takeaway is how proxies enable you to build guarantees into your objects without affecting normal functionality. The ability to intercept values and throw errors when they are incorrect can greatly reduce errors based one assigning the wrong type of data to a property.

April 22, 2014

Creating defensive objects with ES6 proxies

This past week I spent an hour debugging an issue that I ultimately tracked down to a silly problem: the property I was referencing didn’t exist on the given object. I had typed request.code and it should have been request.query.code. After sternly lecturing myself for not noticing earlier, a pit formed in my stomach. This is exactly the type of situation that the JavaScript haters point out as why JavaScript sucks.

The haters are, in this case, correct. If I had been using a type-safe language then I would have gotten an error telling me that the property didn’t exist, and thus saved me an hour of my life. This wasn’t the first time that I’d encountered this type of error, and it likely wouldn’t be the last. Each time it happens, I stop and think about ways that I could prevent this type of error from happening, but there has never been a good answer. Until ECMAScript 6.

ECMAScript 5

Whereas ECMAScript 5 did some fantastic things for controlling how you can change existing properties, it did nothing for dealing with properties that don’t exist. You can prevent existing properties from being overwritten (setting writable to false) or deleted (setting configurable to false). You can prevent objects from being assigned new properties (using Object.preventExtensions()) or set all properties to be read-only and not deletable (Object.freeze()).

If you don’t want all the properties to read-only, then you can use Object.seal(). This prevents new properties from being added and existing properties from being removed but otherwise allows properties to behave normally. This is the closest thing in ECMAScript 5 to what I want as its intent is to solidify (“seal”) the interface of a particular object. A sealed object, when used in strict mode, will throw an error when you try to add a new property:

"use strict";

var person = {

name: "Nicholas"

};

Object.seal(person);

person.age = 20; // Error!

That works really well to notify you that you’re attempting to change the interface of an object by adding a new property. The missing piece of the puzzle is to throw an error when you attempt to read a property that isn’t part of the interface.

Proxies to the rescue

Proxies have a long and complicated history in ECMAScript 6. An early proposal was implemented by both Firefox and Chrome before TC-39 decided to change proxies in a very dramatic way. The changes were, in my opinion, for the better, as they smoothed out a lot of the rough edges from the original proxies proposal (I did some experimenting with the early proposal[1]).

The biggest change was the introduction of a target object with which the proxy would interact. Instead of just defining traps for particular types of operations, the new “direct” proxies intercept operations intended for the target object. They do this through a series of methods that correspond to under-cover-operations in ECMAScript. For instance, whenever you read a value from an object property, there is an operation called [[Get]] that the JavaScript engine performs. The [[Get]] operation has built-in behavior that can’t be changed, however, proxies allow you to “trap” the call to [[Get]] and perform your own behavior. Consider the following:

var proxy = new Proxy({ name: "Nicholas" }, {

get: function(target, property) {

if (property in target) {

return target[property];

} else {

return 35;

}

}

});

console.log(proxy.time); // 35

console.log(proxy.name); // "Nicholas"

console.log(proxy.title); // 35

This proxy uses a new object as its target (the first argument to Proxy()). The second argument is an object that defines the traps you want. The get method corresponds to the [[Get]] operation (all other operations behave as normal so long as they are not trapped). The trap receives the target object as the first argument and the property name as the second. This code checks to see if the property exists on the target object and returns the appropriate value. If the property doesn’t exist on the target, the function intentionally ignores the two arguments and always returns 35. So no matter which non-existent property is accessed, the value 35 is always returned.

Getting defensive

Understanding how to intercept the [[Get]] operation is all that is necessary for creating “defensive” objects. I call them defensive because they behave like a defensive teenager trying to assert their independence of their parents’ view of them (“I am not a child, why do you keep treating me like one?”). The goal is to throw an error whenever a nonexistent property is accessed (“I am not a duck, why do you keep treating me like one?”). This can be accomplished using the get trap and just a bit of code:

function createDefensiveObject(target) {

return new Proxy(target, {

get: function(target, property) {

if (property in target) {

return target[property];

} else {

throw new ReferenceError("Property \"" + property + "\" does not exist.");

}

}

});

}

The createDefensiveObject() function accepts a target object and creates a defensive object for it. The proxy has a get trap that checks the property when it’s read. If the property exists on the target object, then the value of the property is returned. If, on the other hand, the property does not exist on the object, then an error is thrown. Here’s an example:

var person = {

name: "Nicholas"

};

var defensivePerson = createDefensiveObject(person);

console.log(defensivePerson.name); // "Nicholas"

console.log(defensivePerson.age); // Error!

Here, the name property works as usual while age throws an error.

Defensive objects allow existing properties to be read, but non-existent properties throw an error when read. However, you can still add new properties without error:

var person = {

name: "Nicholas"

};

var defensivePerson = createDefensiveObject(person);

console.log(defensivePerson.name); // "Nicholas"

defensivePerson.age = 13;

console.log(defensivePerson.age); // 13

So objects retain their ability to mutate unless you do something to change that. Properties can always be added but non-existent properties will throw an error when read rather than just returning undefined.

Standard feature detection techniques still work as usual and without error:

var person = {

name: "Nicholas"

};

var defensivePerson = createDefensiveObject(person);

console.log("name" in defensivePerson); // true

console.log(defensivePerson.hasOwnProperty("name")); // true

console.log("age" in defensivePerson); // false

console.log(defensivePerson.hasOwnProperty("age")); // false

You can then truly defend the interface of an object, disallowing additions and erroring when accessing a non-existent property, by using a couple of steps:

var person = {

name: "Nicholas"

};

Object.preventExtensions(person);

var defensivePerson = createDefensiveObject(person);

defensivePerson.age = 13; // Error!

console.log(defensivePerson.age); // Error!

In this case, defensivePerson throws an error both when you try to read from and write to a non-existent property. This effectively mimics the behavior of type-safe languages that enforce interfaces.

Perhaps the most useful time to use defensive objects is when defining a constructor, as this typically indicates that you have a clearly-defined contract that you want to preserve. For example:

function Person(name) {

this.name = name;

return createDefensiveObject(this);

}

var person = new Person("Nicholas");

person.age = 13; // Error!

console.log(person.age); // Error!

By calling createDefensiveObject() inside of a constructor, you can effectively ensure that all instances of Person are defensive.

Conclusion

JavaScript has come a long way recently, but we still have a ways to go to get the same type of time-saving functionality that type-safe languages boast. ECMAScript 6 proxies provide a great way to start enforcing contracts where necessary. The most useful place is in constructors or ECMAScript 6 classes, but it can also be useful to make other objects defensive as well. The goal of defensive objects is to make errors more obvious, so while they may not be appropriate for all objects, they can definitely help when defining API contracts.

References

Experimenting with ECMAScript 6 proxies by me (NCZOnline)

April 15, 2014

A framework for thinking about work

Your product owner comes to you with a request, and suddenly your stomach is tied in knots. There’s something about the request that doesn’t sit right. You blurt out, “well, that’s a lot of work,” because it’s the only thing that comes to mind. “Well, it’s really important,” comes the response. Inevitably, some uncomfortable conversation follows before one or both parties leave feeling wholly unsatisfied with what has transpired. Sound familiar?

The interaction between product owners and engineers is an always interesting and sometimes tense situation. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing – a little bit of pushing and pulling is good for the development process. Where things get difficult is a lack of shared understanding about what is being undertaken. I overhear and see situations where engineers are pouring an enormous amount of work into what is (in my mind) such a small thing that it should barely register on the priority list. In those instances, I imagine the initial conversation with a product owner and how it could have been more effective.

I eventually came to the conclusion that all work could be described by using two measures: value and effort.

Value

What exactly is value? Value means many things to many people, and it’s typically the job of the product owner to define the value for any given feature (or other work). Value means doing this work provides meaningful value to the customer, the product, or the company as a whole. In a healthy organization, the product owner has conducted market research, conferred with leadership, and determined that work should be done based on some perceived advantage of doing so. Value can mean:

Competitive advantage. You’re building something that your customers want and need. Doing so means they won’t seek out other options (your competitors) to fulfill their needs.

Sales. The work allows your company to sell to more customers or enter into bigger sales deals.

Customer satisfaction. Scratching a particular itch that a customer has, whether through fixing bugs or adding new features, is the way to ensure that existing customers stay customers while also building a reputation.

Strategic. Doing the work puts the company into an advantageous situation to execute on a larger strategy. For example, the company may want to enter a new market or new region.

There are other values that work can provide, but these tend to be the primary motivators. You shouldn’t be doing work if you don’t understand the value that the work provides.

Effort

Effort means a lot of things to a lot of people, but fundamentally it means the amount of work to complete a task. The amount of work is measured by:

Number of people required. A two-person task is more effort than a one-person task, though not necessarily double. There tends to be additional effort in coordinating multi-person tasks so the amount of effort per person isn’t necessarily linear.

Amount of time required. How long will it take to complete the work given the appropriate number of people? How long with less than the required people? And what if you take into account the inevitability of things not going as smoothly as planned? Understanding the time component of work is critical.

Complexity/Risk. The difficulty of work isn’t simply measured in time. The more complex the work is, the more likely it will introduce or uncover bugs. The more complex a change is, the more risk you introduce into the system and the more careful you must be.

Similar to value, there are other things to take into account when calculating the effort for a task, but these tend to be the major ones.

The grid

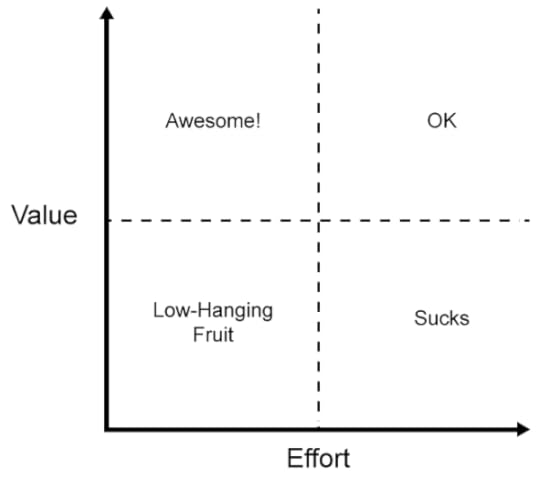

Over the years, I’ve come to think about work as falling on a two-dimensional grid. Along one axis is the amount of value that work provides, increasing as it goes up. On the other axis is effort, which is the amount of time it takes to complete the work, increasing as it goes right. We all know that there are low effort and high effort tasks, and we all end up doing a fair amount of both (as well as work that falls in the middle).

The really interesting part is looking at where the value and effort for a particular piece of work overlap.

I split the graph into quadrants:

Low-hanging fruit – this is low value work that requires little effort to complete. Anything that falls in this quadrant is usually described as, “we might as well just do it.” The amount of work is relatively equal to the value you get out of it, so it makes sense to do.

Awesome – this is high value work that requires little effort to complete. This doesn’t come along very often but is extremely awesome when it does. When I was at Yahoo, were battling a performance issue with certain Ajax requests when we discovered that the Ajax responses weren’t being gzipped due to a misconfiguration. It took all of a few minutes to fix and made a huge difference in our performance.

OK – this is high value work that takes a lot of effort to complete. Things like the redesigning an application or upgrading infrastructure fall into this category. The amount of effort required is high, but the value we get out of it is so high that we know we need to commit to it. Spending time in this area isn’t the most fun, but it is definitely worthwhile.

Sucks – this is low value work that requires a lot of effort to complete. As the name implies, you don’t want to end up here. The amount of effort is way out of proportion to the value we get from that effort, which essentially means you’re wasting time (especially if there is other higher-value work that could be done in the same amount of time). This is like trying to get cross-iframe communication working in IE6 with different domains. Your goal should be to avoid working in this area at all costs.

The interesting part

That’s a nice theory, you may be thinking, but how does this work in reality? Here’s the interesting part: engineers and product owners each own one axis on this chart. Engineers know how much effort it takes to accomplish something while product owners know how much value the work provides. Want to determine where the work falls on the graph? Have each (engineer and product owner) assign a number 1 to 10 to their axis, then see where they intersect. You have a 75% chance of ending up in a quadrant where the work is acceptable and should be done.

Of course, this process works best when both parties are completely honest about the work.

Help, I’m stuck in “sucks”!

If you find that you’re stuck in the “sucks” quadrant, then there’s some work to do. There are two ways to address this. The first is to decrease the amount of effort to gain the same value (move into the low-hanging fruit quadrant), which may mean scaling back to the minimal implementation that provides the value. The second is to provide more value for the work you’ll be doing (move into the OK quadrant). Either approach is acceptable – what isn’t acceptable is remaining in the sucks quadrant and doing that work.

Of course, the last option is to agree to just not to do the work. Sometimes, this ends up being the right answer (you’re “off the grid” at that point).

Stop. Think.

So next time you’re doing planning, stop and think about which quadrant your work falls into. Most of the time, you’ll be working the low-hanging fruit or OK quadrants, which is what you want. If you find yourself in the awesome quadrant, give yourself a pat on the back and tell people of your heroic feats. If you find yourself in the sucks quadrant, back up, take an accounting, talk to your product owner, and see if you can move that work into a different quadrant. Don’t haphazardly spend time in the sucks quadrant – there’s a lot of high value work to be done, make sure you’re doing it whenever possible.

April 2, 2014

I have Lyme disease

As best I can recall, it all started around 15 years ago. I was finishing up my sophomore year at college and had just taken my last final exam. The following Monday I would be heading into the hospital for some diagnostic tests related to persistent and as-yet-undiagnosed digestive issues. I woke up on Sunday feeling sicker than I’d ever felt in my entire life. My head was pounding, my body ached, I was nauseous, dizzy, and tremoring; the very definition of “flu like symptoms.” I spent the entire day in bed and prayed I’d feel better for all the tests I had to endure the next day. I didn’t.

When I got to the hospital they took one look at me and immediately hooked up an IV. I was dehydrated, bordering on delirious, and so weak that I needed help walking. Once they laid me down, I didn’t have enough strength to lift my head off of the pillow. Tests were run and everything came back negative. They sent me home and I was essentially bedridden for three months with all of these symptoms persisting.

I would eventually recover with the help of a chiropractor who surmised that I must have severe food allergies. Following a very strict diet and supplement protocol, I slowly regained my strength. It would take a year for me to fully recover, or so I thought.

Not the end

Although I was feeling much better, I would still get episodes where the symptoms would recur. They would happen every 2-3 months and I’d be sick in bed for 1-2 weeks. The episodes would come on suddenly and, try as I might, I was never able to discern a pattern. As a plucky 20-something, I pushed through as much as I could, and took to bed only when absolutely forced. After an episode was over, I’d feel back to normal. The only lingering symptom was incredibly unrestful sleep (as in, I could fall and stay asleep easily, but upon waking, I would feel like I didn’t get any rest) and persistent exhaustion.

Over the years I’d seek the opinion of dozens of doctors and alternative healthcare practitioners. Everyone was baffled. No one had experienced anything like what I was describing. I amassed quite an array of diagnoses: chronic fatigue syndrome, fibromyalgia, depression, anxiety, eating disorder, malabsorption. The one that stuck was chronic fatigue syndrome, as it was the best atomic description of what my body was presenting.

Chronic fatigue syndrome is strange in that it’s the name for a set of symptoms similar to mine but there is no test for it. You are deemed to have chronic fatigue syndrome only after a doctor has ruled out every other possible cause of persistent fatigue. And at that point, you’re pretty much screwed. There are no treatments and no cure, which makes sense, because no cause has ever been identified.

The symptom brigade

As time marched on, the amount of time in between episodes decreased and the length of the episodes increased. I also starting collecting new symptoms, each one more bizarre than the last, seemingly without cause. I started losing weight without trying. I went from a fit and athletic 165 lbs. to 160, and then 155, 150, all the way to my recent lowest of 128. It happened gradually but persistently over 10 years. Doctors accused me of having an eating disorder, of being too depressed to eat, of making myself sick to get attention. I told them over and over that I was eating all the time and nothing I did worked; they didn’t believe me. And so I sat by and watched, horrified, as my body grew weaker and more emaciated.

I started getting bizarre skin rashes that doctors couldn’t identify. I started losing my hair in my early 20s despite a favorable family history regarding male pattern baldness holding out until middle age. I seemingly acquired more food allergies with every passing year, defying the belief of every doctor I saw. I developed a chronic cough that made some think I was secretly smoking.

Then the neurological trouble started. I noticed my memory slipping and my short-term memory being effectively reduced to dog-like lengths. I found myself making mistakes on things I should know. I had trouble solving problems that I knew I should make short work of. I had trouble recalling words and names of people. My ability to concentrate disappeared – every conversation, every thought was a struggle.

I woke up one morning to find both of my arms numb and tingling. After another week, the tingling had spread to my neck and face. The tingling started to subside, giving way to intense nerve pain in my arms that was initially misdiagnosed as a repetitive stress injury (it didn’t respond to any RSI treatment). Shortly thereafter, after an intense (and undiagnosed) pain in my throat, speaking became a struggle. My voice ended up hoarse all the time and even short conversations caused immense pain. It felt like my throat just wouldn’t respond to my command to speak.

More recently, I’ve had bouts of extreme confusion. I’ve been stuck trying to complete everyday tasks. My brain feels like it doesn’t have the knowledge. It’s a combination of forgetting how to do something combined with not being able to solve the problem again, and it’s one of the most helpless feelings I’ve ever experienced. Last night, I looked at a closed container of parmesan, then back to my plate, then back to the parmesan, impatiently waiting for my brain to tell me how to open the container and pour the cheese onto my food.

Coping mechanisms

If you’ve ever met me, you may be wondering at this point whether I was experiencing any of these symptoms while with you. The answer is yes. For a long time, my life has been a carefully crafted act and series of processes to allow me to function somewhat normally. I struggled through every talk I’ve given, every interaction I’ve had. You see, I learned early on that people are very unsympathetic when it comes to my condition. When I initially got sick, my girlfriend of four years dumped me because it’s no fun dating someone who doesn’t feel well enough to go out. My senior year in college, the drama club took away my part because I had a bad episode eight weeks before opening night and had to miss a week of rehearsal. Those experiences convinced me that this was a secret I would need to keep or else I’d be denied the life I wanted.

Chronic fatigue syndrome, though officially recognized by the CDC, is still treated primarily as a psychological disorder. If you have cancer or AIDS, you are a victim who is bravely fighting a horrible disease. Society regularly labels these people as brave, courageous, and heroic. They are incredibly strong and we cheer them along in their pursuit of health (several members of my family have had, and beaten, cancer, and they are undeniably heroes). If you have chronic fatigue syndrome, though, society views you as weak, as emotionally inferior and constitutionally lacking. People tell you to “snap out of it” or “it’s just depression,” as if you could just decide to be healthy and it would be so. Even people you think love you still harbor secret opinions, “well, he is a bit of a hypochondriac.” These are the people we ridicule on sitcoms: the kid who needs an inhaler, the teenager with food allergies, all labeled as “weak” and pitiful. Not victims of unfortunate circumstances like those fighting a “real” disease, but people who have chosen to be weak, and therefore, deserve ridicule if for no other reason than it might snap them out of it.

So I devised ways to continue functioning, how to act healthy even when I felt horrible. I had no other choice and I was damn good at it. Some of the girls I dated never knew anything was wrong. Close friends and family members were kept in the dark. I was able to arrange my life in such a way that I could keep up the appearance of health. I became adept at excuse-making when I knew I was physically not well enough to do something. I had a cold. I’ve been working too much and need to rest. I had a wild weekend last week, so this weekend I’m just going to relax.

To make up for my failing memory and inability to concentrate, I started writing things down. The writing that you may know me for now was born out of a realization that I would most likely not remember what I had done or learned. The very first article I wrote was just for myself, written in such a way that I knew I would be able to re-learn it by reading the article carefully. It was only when a friend saw the article and convinced me to publish it that I realized the way I describe things for myself would be useful for others as well.

I also crafted my personality carefully to avoid energy-sucking behavior. While in my early 20s I was gregarious and always had something to say, I tapered down unnecessary conversation as my energy levels decreased with the passing of time. Those who meet me today tend to describe me as opinionated, but also as someone who will really listen. That was a purposeful change because listening takes far less energy than talking, and so I want to save my energy to say and do the really important things (see also: spoon theory).

Over the years I’d need to cut down on extracurricular activities to preserve my energy. I used to go to the gym four times a week to lift weights. I kept cutting down until I no longer went, there just wasn’t enough energy. I used to go out on the weekends, but in the past few years, all I’ve done is go to work and then come home to rest. I’ve had to give up things like meeting friends for dinner, going to shows, and other social events. That necessarily meant no more dating – the facade became too much energy to maintain while not at work, and it’s hard to start a relationship when you never feel well enough to go out and do anything.

The hardest part has been the gradual increase of isolation. Those with chronic fatigue and similar conditions often cite this as the most difficult part of their condition. Losing touch with friends, not being able to see loved ones, and without hope of meeting new acquaintances, life becomes quite dreary. If you let it.

This is why I believe in the transformative power of the Internet. I was able to still feel a part of the world no matter how sick I felt. Email, Twitter, Facebook, are all godsends to those with limiting health issues. It’s not quite the same as having someone there with you, but it helps immensely. I can do my food shopping, order gifts, and do all my banking online. What is a convenience for most people is how I’ve been able to stay self-sufficient for so long.

Mind games

A couple years ago, I recognized that my health had been on a steady decline. I mapped out what I thought was the most probable future: I estimated that at my rate of decline, without intervention, I would likely be functionally incapacitated within five years. I’m not talking about needing to work from home permanently, I’m talking about being unable to even work from home due to the physical stress and my deteriorating cognitive ability, effectively someone who would need to be in a nursing home. That’s not something most people even consider in their 30s, but I had to be realistic and plan appropriately. I got my affairs in order, put together a will, a power of attorney should I become incapacitated, and a living will. I figured the least I could do was to make it easy in the seemingly likely event that I’d be unable to care for myself in the not-too-distant-future.

I had promised myself a long time ago that I would never give up looking for the answer, but after over a decade of failing, I was beginning to doubt that the answer would arrive in time. So while I continued researching new studies on chronic fatigue syndrome, I decided to focus on the one thing I could control: my thoughts.

When I was little, my dad used to always talk about “mind over matter.” He’d use that phrase over and over again, and it stuck. Control your thoughts and you can exert some sort of control over the world through your reactions to it. So I started looking into ways of quieting my mind and taking back control of my thoughts. It took me several years, but through a combination of various meditation practices and hypnotherapy, I was finally able to create peace in my mind. I had tools for dealing with the horrific esoteric thoughts that could creep in when I wasn’t paying attention (“am I being punished?”, “am I bad person and so I deserve to suffer?”), I learned how to focus my mind on a task despite the firestorm in my body, and learned to accept what my body was telling me rather than trying to fight it.

I finally reached a point of peace. I wasn’t depressed, I wasn’t anxious, I just was. And in just being, I found more ways to calm my mind. The best way? Writing.

Writing became a form of meditation for me. I’d get lost as the words flowed from my mind effortlessly, with a gentle focus that made me feel peaceful and strong. Once I got into the flow of writing, whether a technical article or not, my mind relaxed into a familiar and comfortable pattern. It was pacifying to my mind and body. And so writing became my primary escape.

No matter how I felt, or how upset I might get about any type of situation, I would start writing so long as I felt well enough. It didn’t even matter what I was writing. I’d write letters to no one in particular, technical blog posts for this site, non-technical blog posts under a pseudonym on other sites, books, articles…it didn’t matter, what mattered was the writing. I can write for eight hours straight without a break when I get going. The meditative feel of the experience is such an available escape from however I’m feeling that I indulge regularly.

This experience is exactly why I tell aspiring writers to just write, about anything or nothing in particular, regardless of who might read it. Writing has been so soothing and comforting for me, that I can’t imagine what I would be like without it.

Lyme disease

How I discovered I have Lyme disease rather than the much more mysterious chronic fatigue syndrome is a story that some will have trouble believing. Suffice to say, when you’re fed up with doctors telling you you’re not sick, you will do anything and see anyone who might give you a glimmer of hope. You seek out the strange, the bizarre, because what other choice do you have?

I had been seeing a wonderful hypnotherapist who helped me process a lot of baggage and finally release it. For some, this is the most esoteric thing they’d consider, but it’s nowhere near the strangest type of healer I’ve ever seen. After one of our sessions, she told me that while she enjoyed working me, her gut was telling her the root of my problems was physical and not emotional. She then referred me to a strange old lady who practices a type of healing art related to the body’s energy field. The hypnotherapist assured me that this would be a bizarre visit, but it would be well worth it.

The old lady hobbled along with the help of a walker and used a technique called applied kinesiology to ask my body questions. What would follow was nothing if not the most entertaining evaluation I’d ever experienced. She proceeded to ask my body yes and no questions, and waiting for reactions in her partner’s muscle strength. Yes, it’s just as weird as it sounds, but I was desperate. Then she started asking my body if it had specific types of infections that I had never heard of. She used the word spirochete, which I had never heard of before. She recommended some herbs and wrote down what she had found.

Now, I’ve been to my fair share of strange health practitioners over the years, and as such, developed a very finely-tuned bullshit detector. I could tell when people were reaching or clueless, and I could tell when people were on to something. So I went home and did what anyone would do: I opened up Google and started typing in all the words I didn’t know. When I did that, all that came up were articles about Lyme disease.

I immediately did more research and ordered a book that I found from following the articles. The more I read the book, the more excited I got. The story sounded exactly like me, from bizarre beginnings to tests all showing nothing was wrong to recurring episodes of poor health. My heart started to beat faster and a growing amount of excitement surged in my body. Could this be it?

I ordered several more books on Lyme disease and started researching specialists in the area, eventually settling on a doctor not five minutes from my apartment. It took a couple of months to get in to see her. Because her specialty is fatigue-related disorders, including Lyme, I wanted to present her with my symptoms only and let her tell me what she thought was going on. I didn’t mention Lyme at all, because I didn’t want to unintentionally affect the diagnosis, I just relayed all of my symptoms and waited for her to respond. After about 30 minutes of listening to me name off symptom after symptom, she stopped and said, “So here’s my theory. I think around 15 years ago you got bitten by a deer tick and you have Lyme disease.”

She ran a lot of specialized bloodwork for Lyme disease and several other types of infections that are frequently seen with Lyme disease, and when I got the results back, they confirmed the diagnosis. I have Lyme disease along with a couple of related coinfections. I started treatment five weeks ago, and the average treatment period for chronic Lyme disease is 1-2 years. The treatment has some very unpleasant side effects, so I have a long road ahead. But for the first time, I have a path to travel.

Why share now?

You may be wondering why I’m sharing my story now. I debated whether I should or not, but upon seeking some advice from friends, I feel like it’s the right thing to do. I’ve been really sick since the end of last year, I’ve been stuck in a bad episode for months and so I’ve stopped giving talks, and more recently, have been forced to work from home due to my condition. I’ve been blowing off invitations for all kinds of things, lunches, talks, conferences, meetups, and I want everyone to know that I’ve not suddenly become a shut-in who doesn’t want to interact with people. It’s that I’m very sick and I’m trying to get better.

I’ve worked very hard to craft my public persona into something I’m proud of, and I realized that writing this post means I could very well end up being labeled as “that guy JavaScript guy with Lyme disease.” In one post, I would redefine myself publicly in terms of my disease, and that frightened me to no end. The years of trying to hide how sick I felt and the scorn I felt from people judging me as weak is still very fresh in my mind. I wasn’t sure if I was ready to embrace that.

However, something amazing has happened as a result of my illness and diagnosis. I reconnected with a childhood friend who had similar symptoms for years, and it now looks like she has Lyme disease and will be able to get better with treatment. Another friend relayed my story to her friend, who had suffered with a lot of similar symptoms, and she is now investigating Lyme disease as a possibility. There is so little attention on Lyme disease that it often goes misdiagnosed, sentencing people to miserable symptoms simply because not enough people understand the disease. I realized that everything I’ve been through could help others if I shared my story, and if my experience can save even one person from one day of suffering, then it’s worth any personal discomfort I might feel.

Be your own advocate

If you take anything away from this post, I hope that it’s this: be your own advocate. Listen to your body, no one knows your body better than you. Doctors may run tests that come back negative, but just like code, you can’t find the bug if you’re looking in the wrong place. Don’t let anyone convince you that your problems are all “in your head” and don’t convince yourself that suffering is normal and acceptable. It is not.

If you have unrestful sleep, persistent flu-like symptoms, strange infections and conditions, see a doctor and get all the horrible stuff ruled out. Sometimes the answer is simple and will show up on standard tests. I’ve had friends with similar symptoms find out they had brain tumors, or sleep apnea, or food allergies, or thyroid conditions. Those can all be tested for very easily. If you’ve ruled out everything else, start researching Lyme disease.

And if you’re suffering from some unknown, undiagnosed ailment, don’t give up on life. Absolutely everything worthwhile I’ve accomplished in my life occurred after I got sick. The only real limits you have are the ones you place on yourself.

March 26, 2014

Announcing Understanding ECMAScript 6

For almost two years, I’ve been keeping notes on the side about ECMAScript 6 features. Some of those notes have made it into blog posts while others have languished on my hard drive waiting to be used for something. My intent was to compile all of these notes into a book at some point in time, and with the success of Principles of Object-Oriented Programming in JavaScript[1], I decided that I’d like to do another self-published ebook. My initial experience with self-publishing went so well that I really wanted to make my next one even better. This is what you can expect.

Open from the beginning

Understanding ECMAScript 6 will be the first book (or ebook) that I write in a completely open manner. I’ve come to realize over the years that digital rights management is a fool’s errand. Big publishers, music companies, and movie companies are convinced that people will pirate their work and cost them money. I tend to agree with Tim O’Reilly’s belief that people who pirate have no intent of purchasing the work, so you’re not really losing any money. This is why I’ve only published with companies who have DRM-free ebooks (Wrox didn’t initially, but I was among the first to give the okay to sell DRM-free versions of my books).

With DRM-free ebooks of my content floating around, they will naturally end up in the hands of people who haven’t paid. Oh well. The fact that your for-pay content will end up online at some point where anyone can view it for free is most likely inevitable unless you feel like spending tons of money on lawyer fees to crack down.

So, given that my content is going to end up online for free regardless, I decided that I would make this ebook open from the beginning. That means a few things.

CC licensed

First, Understanding ECMAScript 6 will be licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0[2]. What that means is that you’re allowed to share the work so long as it is properly attributed but you cannot package or repackage it for sale. So if you buy a copy, you can upload it to your company’s shared space for others to view without feeling any guilt. Even if you get a copy for free, you’re allowed to share with others.

I’m doing this because I write primarily to share information and any money I make is a nice side effect of that effort. I really want the information to be out there to benefit others.

Not allowing commercial distribution or derivative works is a way of protecting my content. I’m still going to sell the content on Leanpub (more on that later), and I don’t think it would be fair for someone else to repackage my content and sell it as a competitor. So this license ensures that while the content is free for reading, I’m the only one who can sell it.

Free online

If people are going to be sharing the content for free, it only makes sense to have an “official” free version available online. Leanpub makes this easy as they allow full publishing of the book in HTML form. So from the start, Understanding ECMAScript 6 will be available for free as HTML that is viewable online. This is important to me because I plan on making frequent updates and releases the book as I go, and ensuring there’s always one place that is up to date for everyone to see is important for transparency and understanding how your snapshot relates to the final work.

Of course, you’ll also be able to purchase the various ebook formats from Leanpub. As with my previous ebook, purchasing the ebook once gives you access to all future updates until the book is completed.

Transparency on GitHub

While I’m using a CC license and making the content available online for free, it would be silly not to go the extra mile and make the content available on GitHub. So that’s what I’m doing, the Understanding ECMAScript 6 repository is now live and you can see exactly what I have, what I don’t have, and what sort of content to expect. I get a lot of questions about my process for writing books and now you’ll be able to follow that process from beginning to end.

I’m excited about this because I don’t think a lot of people understand the amount of work that goes into writing books. There is rarely a straight line from empty text file to finished book. There are frequent rewrites, reorganizations, and other changes. Putting the writing process out into the open is my way of showing the often chaotic nature of writing, and more specifically, of my writing.

Even better, instead of sending me emails with errata, you can file pull requests with the suggested fixes. You can file issues for concepts you want explained or problems that you see. In effect, you can interact with this book the same way you would any software project.

Just keep in mind some rules:

What you see on GitHub will have errors and lots of “TODOs” – welcome to my process

I won’t be accepting content contributions, only content fixes

Progress will likely be slow (it takes time to write a book)

There may be long periods of inactivity (see previous point)

Every so often, I’ll tag a snapshot and publish the ebook files on Leanpub.

On making money, or not

At this point you may be wondering why I feel comfortable having the content out there for free rather than forcing people to pay money for it. After all, I could end up making absolutely nothing from this effort. While that’s a possibility, I don’t believe that it’s true. My previous Leanpub experience showed me that not only are people will to pay for good content, they are willing to pay more than the asking price when given the chance. It’s my belief that there are a fair number of people who might receive the book for free and ultimately end up purchasing it because they enjoy the content. I firmly believe that people are generally willing to pay for things they enjoy, so my first goal is to make this book something that people enjoy and the rest should take care of itself.

And if not, I’ll be honest: tech books don’t make a lot of money. It’s not like I’m going to retire on sales of my books anytime soon. This is really not about the money for me. If you enjoy the book and want to show me, then purchase a copy; if you don’t enjoy it, then continue to use the free version. I won’t hold it against you.

Conclusion

I’m excited to embark on this journey. It’s the first time I’ve started a writing project in the open and I’m looking forward to the experience. Hopefully, people will learn just what goes into making a book and how crazy the development process can be. I know it will take a while to reach completion, but I think there’s enough interest in ECMAScript 6 is start writing this ebook now and sharing what I have periodically. I hope you’ll join me on this journey.

References

Principles of the Object-Oriented Programming in JavaScript (Leanpub)

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 (Creative Commons)

March 18, 2014

Leanpub: One year later

At the beginning of last year, I released my first self-published ebook, The Principles of Object-Oriented Programming in JavaScript. I decided to go this route for a few reasons, not the least of which being I didn’t really know how much time I’ve have to commit to its writing, so I didn’t feel comfortable being held to a deadline. I also wouldn’t want to put any publisher into a position where they’d have to chase me down – their business operates on timelines, and that’s something I couldn’t deliver.

I was also curious about the self-publishing revolution. I’d heard both good and bad results from various people who had tried it. Since I’d been through the traditional publishing process many times, I knew right away what I’d be losing: copy editors, technical editors, graphic designers for diagrams, marketing, and a physical book. I rationalized that readers could substitute for copy editors and technical editors to a certain degree by providing feedback, I could do rudimentary diagrams myself, and I could use Twitter and my blog for marketing. I knew I wouldn’t be able to expect the same number of sales vs. working with a publisher, but I rationalized that I didn’t need to sell as many copies because I could keep a larger percentage of the sale price.

Now it’s been a year later, and I decided to review my experience. The ebook was eventually picked up by No Starch Press to publish a print book called The Principles of Object-Oriented JavaScript. While that wasn’t my end goal, it was a nice surprise.

Choosing Leanpub

From the start, I knew I wanted the ability to make constant changes and fixes as I necessary. One of the things I always hated about print books was feeling helpless about typos or other mistakes. If a reader reports an error, I want it fixed immediately. I knew ebooks would give me the ability to do that, but I wanted to make sure I had a platform that would support this workflow.

Another important consideration for me was the format in which I’d have to write. I really wanted to write in Markdown, as it’s now my default format. I’ve grown to hate slogging through Microsoft Word documents, highlighting text, and changing its style. Markdown allows me to write more freely, without worrying too much about how the text looks.

I also wanted to generate all the popular ebook formats: PDF, ePub, and MOBI. I didn’t want to get caught in complaints of not supporting someone’s device, so the system I used had to automatically create each of these three formats.

Leanpub fit the bill perfectly. I could write in Markdown, make fixes and releases whenever I wanted, and all of the formats are generated automatically. Those alone sold me on Leanpub, but the things that really made me ecstatic were:

Variable price ranges let me set the lowest price I’d accept for the ebook as well as the suggested price. So I set the lower price at $14.99 and the suggested price at $19.99. That meant anyone buying the book could decide they didn’t want to pay $19.99 and give themselves a discount. Or they could choose to pay more if they wanted to. I really liked giving readers the power to pay what they felt was fair.

Customized landing pages and URLs are automatically created as part of the publishing process. So all I had to do was provide the content and a page was setup, ready to take orders.

The fact that Leanpub handles all orders and returns is fantastic. I never wanted to deal with that stuff.

The ability to offer coupons for special events came in handy when I was speaking or just wanted to give someone a discount (or the ebook for free).

Automatic royalty payment every month, deposited via PayPal. Authors get paid 90% minus 50 cents for each copy sold – you’ll be hard pressed to find a better deal than that.

As with any system, there were some quirks to get used to such as the default encoding and page layout. The images also have to be made obscenely big to support zooming of various formats. Overall, though, I’ve been very happy with the Leanpub experience.

Who paid what

My big experiment with letting people choose what they’d like to pay for the ebook was interesting. To quote my mother, “why would anyone pay more than they had to?” That was a good point. I figured that most buyers would automatically take the discount and pay $14.99 while a few would opt to pay a bit more. I wasn’t going to be offended if people chose the lowest price possible, I just figured that some would choose $19.99 intentionally. The results were pretty interesting. First, some basic stats (these exclude sales from bundles):

Total Sales: $14,866

Average Price: $16.74

Average Price Without Coupons: $17.66

Max Price: $78.62

On the whole, both considering an eliminating coupon purchases, the average price paid was at least $1.75 higher than the minimum price. So it appears that people are willing to pay more than the minimum, on average, for the ebook. The maximum price paid was $78.62, which is astounding, but there were other purchases at $30 and $50 as well. In fact, a whole lot of people opted to pay more than $19.99; some by just a few cents, by a few dollars.

Out of 888 purchases, 74 chose to pay more than the asking price while 243 chose to pay the asking price. While the majority did pay the lowest possible price (both including and excluding coupons), there were enough who chose to pay more that it’s hard to overlook. There was even one reader who returned the ebook just so he could buy it for more.

I found this to be an amazing occurrence: people will actually pay more if allowed to do so, and not just some of the time, on an ongoing basis. I like to think that letting people assign their own value to the thing they want to purchase is powerful. Of course, I set a lower limit to ensure I got at least $14.99, but allowing people to otherwise decide what they want to pay resulted in purchases for amounts I could never charge without feeling incredibly guilty.

While the $14,000 in sales is much lower than I have had with any of my other books, the royalties from those sales were pretty much inline with what I end up making in the first year with a new book. So ultimately I sold less copies while making roughly the same amount.

Conclusion

My experience with Leanpub over the past year has been a positive one. I’ve enjoyed using the platform and writing/updating the ebook. The sales were good enough that I’d be comfortable doing another ebook in the future, and my experience with DRM-free ebooks has been positive enough that I’m looking at ways of making future ebooks even more open. It’s so nice to work without external deadlines and just write at a pace I feel comfortable. The fact that this ebook ended up as a print book as well further convinces me that this may be the way to go for anything new that I write.

That’s not so there isn’t value in working with traditional publishers. It was only through my experience with Wiley and O’Reilly that I truly understood what I’d be missing by going this route. I highly encourage all aspiring authors to work with a publisher at least once so that you understand the entire process and just how involved it can be. Going on your own might seem like the fastest way to get your stuff out there, but you want to be sure what you’re putting out is a quality product, and it’s hard to know how to do that without having someone guide you along once or twice first.

March 4, 2014

Accessing Google Spreadsheets from Node.js

I’ve recently been working on a project involving Google Spreadsheets. My goal was to store data in the spreadsheet using a form and then read the data from that spreadsheet using a Node.js application. Having no experience with Google web services, I ended up digging through a lot of documentation only to find that there are no official Node.js examples. So I pieced together the process of accessing data from a Google Spreadsheet and wanted to share so others wouldn’t have to do the same thing.

This post assumes that you already have a Google Spreadsheet and that the spreadsheet is not shared publicly. It also assumes that you do not want to use your Google username and password to access the spreadsheet through a web service. This is possible, but I personally feel better using OAuth.

Step 1: Create a Google Developers Console project

In order to access data from any Google web service, you first need to create a project in Google Developers Console. Name it whatever you would like and then click on it to see more information about the application.

Step 2: Enable the Drive API

All projects have a set of APIs enabled by default, but the Drive API isn’t one of them. This is the API that lets you access things inside of Google Drive, including spreadsheets.

On the left side, click APIs & auth and then APIs. On the right side, scroll down until you find the Drive API and click the button to enable it.

Step 3: Create a service account

In order to avoid using your personal Google account information to access the API, you’ll need to set up a service account. A service account is a Google account used only to access web services.

On the left menu, click APIs & auth and then Credentials. You’ll see your client ID and the email address representing your application. Don’t worry about those, you don’t need them.

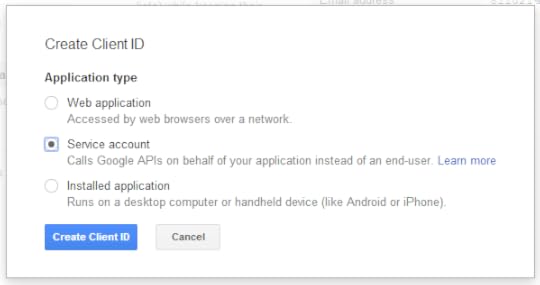

Click Create New Client ID, which will pop up a dialog. Select Service Account and click Create Client ID.

You’ll then see your new information on the page.

Step 4: Generate a key

The service account you created needs a way to authenticate itself with the Drive API. To do that, click Generate a New Key, which is located under the service account information.

The browser will download a private key and you’ll be given the password to use with the key. Make sure to keep this file safe, you won’t able to get another copy if you lose (you’ll just create a new key).

Step 5: Generate a PEM file

In order to use the key in Node.js with the crypto module, the key needs to be in PEM format. To do that, run this command:

openssl pkcs12 -in downloaded-key-file.p12 -out your-key-file.pem -nodes

You’ll be asked for the password that was given to you in the last step.

Step 6: Share your spreadsheet

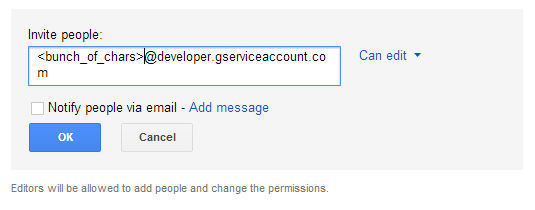

When you created the service account, an email address was created along with it in the format of @developer.gserviceaccount.com. The email address is important because you need to share your spreadsheet with the service account.

To do so, open the spreadsheet and click the Share button. In the dialog, enter your service account email address and uncheck Notify people via email. You’ll be asked to confirm that it’s okay not to send an email, and of course it is, since that’s just the service account.

You can decide whether you want the service account to have full access to modify the spreadsheet or just view it. As always, it’s best to start with the lowest permission level needed.

Step 7: Setting up your Node.js project

There are a lot of packages on npm relating to Google APIs, but for my use case I chose edit-google-spreadsheet due to its excellent documentation and support for multiple authentication methods, including OAuth2. If you just want a library to deal with authentication (assuming you’ll do the web service calls yourself), then take a look at google-oauth-jwt.

Install edit-google-spreadsheet:

npm i edit-google-spreadsheet --save

Step 8: Making the request

The edit-google-spreadsheet module is simple to get started with. Here’s an example that reads the spreadsheet:

var Spreadsheet = require('edit-google-spreadsheet');

Spreadsheet.load({

debug: true,

spreadsheetId: '',

worksheetName: 'Sheet 1',

oauth : {

email: '@developer.gserviceaccount.com',

keyFile: 'path/to/your_key.pem'

}

}, function sheetReady(err, spreadsheet) {

if (err) {

throw err;

}

spreadsheet.receive(function(err, rows, info) {

if (err) {

throw err;

}

console.dir(rows);

console.dir(info);

});

});

You can specify the spreadsheet to read by using either spreadsheetName or spreadsheetId. I prefer using spreadsheetId, since the name may change at some point. The ID is found in the share URL for the spreadsheet. For example:

https://docs.google.com/spreadsheet/c...

The value for the query string param key is the spreadsheet ID.

You also need to specify which worksheet to read. Unfortunately, the worksheet ID isn’t available in the Google Spreadsheets UI, so you’ll need to at least start by using worksheetName. The worksheet IDs are available in the extra information sent along the spreadsheet data (info in the example).

In this example, I also have the debug flag set, which outputs additional information to the console. Start with it turned on to aid with development, I found it immensely useful.

For more information on how to use edit-google-spreadsheet, please see its README.

The end

With that, you should be able to get an app up and running easily with access to Google Spreadsheet data. I’ve always loved the ability to set up arbitrary forms that store their data in Google Spreadsheets, and now being able to programmatically access that data from Node.js just makes it an even more powerful option.

February 25, 2014

Now shipping: Principles of Object-Oriented JavaScript

I’m very proud to announce that Principles of Object-Oriented JavaScript is now shipping! For frequent readers, this book is the print version of my self-published ebook, The Principles of Object-Oriented Programming in JavaScript, which I published at the beginning of 2013.

I’m very proud to announce that Principles of Object-Oriented JavaScript is now shipping! For frequent readers, this book is the print version of my self-published ebook, The Principles of Object-Oriented Programming in JavaScript, which I published at the beginning of 2013.

Birth of an ebook

The whole process began after a chat with Kate Matsudaira. We were talking about the ins and outs of publishing, and she managed to convince me that I should self-publish my next book. After doing a bit of research, I wound up selecting Leanpub as the publisher. I really liked a lot about their service:

Books could be written in Markdown

Automatically generate three formats of ebook

Automatic customizable product page

Handling of payments and refunds

Royalty payments through PayPal

Readers can select how much money they want to pay

Ability to update the ebook at any time and allow existing readers to update for free

I chose the topic because I was consulting at the time and was teaching a full-day course on object-oriented programming in JavaScript. Although I would leave a copy of my slides with the attendees, I felt like that wasn’t enough for them to remember everything we had talked about. I thought a companion book that covered the topics in the same order and with the same examples would be incredibly useful. So I started writing.

I quickly realized that this would be a short book, much shorter than most of my others. When compared to Professional JavaScript for Web Developers, which is over 900 pages, this book would clock in at just under 100 pages. That made me happy because I know that 900 pages can be intimidating. I’d also grown much fonder of short books with a laser-focus on specific topics.

Enter No Starch

When the ebook was complete, I didn’t think there was much chance of getting it published as a physical book by an existing publisher. Most publishers want around 200 pages. I figured if there was enough interest then I’d try to self-publish the physical book as well, but I would wait to see what the response was.

I ended up in a conversation with Bill Pollack from No Starch Press at Fluent last year. I explained to him what I was doing and he shared how No Starch approaches publishing. I was really enamored by the old-school approach he described: serious copy and tech editors, fine-tuning of topics and tone, and an approach to putting out a small quantity of high-quality books each year. We left with a handshake that we’d talk again if he liked what he read.

After reading the ebook, Bill thought it was worthwhile to proceed to create a physical book. No Starch wasn’t the first publisher to approach me, but they definitely felt like the right one. One of my big concerns was being able to continue selling on Leanpub so I could fulfill my commitment to those who had purchased the ebook already. Where other publishers said I would have to take down the Leanpub offering, No Starch allowed me to keep it up.

Working with the folks at No Starch was great, it reminded me of how things were in publishing ten years ago. The copy editing was fantastic and really smoothed out a lot of my narrative. The tech editing by Angus Croll was incredibly useful and appropriately nitpicky (seriously, if you don’t think your tech editor is nitpicky, you need to find a new one). And the cover design, well, I couldn’t be happier (the theme is JavaScript as the engine that driving web and server).

Code Lindley graciously agreed to write a foreword for the No Starch version.

So what is this book?

First and foremost, this book is the print edition of my self-published ebook, but with actual copy editing, tech editing, and professional graphics. The topics covered are the same and are mostly covered in the same way (the No Starch version has additional clarifications in some places). As a bonus, there is a No Starch ebook version.

The book itself is about understanding objects in JavaScript. Topics include:

The differences between primitive and reference values

What makes JavaScript functions so unique

The various ways of creating an object

The difference between data properties and accessor properties using ECMAScript 5

How to define your own constructors

How to work with and understand prototypes

Various inheritance patterns for types and objects

How to create private and privileged object members

How to prevent modification of objects using ECMAScript 5 functionality

One of the things I wanted to do with this book was treat ECMAScript 5 as the current version of JavaScript. There are still a lot of books that end up saying things like, “if your browser supports ECMAScript 5, do it this way.” I wanted to look towards a future where ECMAScript 5 is the minimum version everyone uses, and so I chose to do away with those qualifying statements and use ECMAScript 5 terminology exclusively throughout.

I also wrote the book in such a way that it’s relevant both for web and Node.js developers. There is very little mention of web browsers or Node.js, and that is intentional, to focus on the core of JavaScript that is universally applicable.

Overall, I’m very proud of this book. I think it’s short enough to not be intimidating but dense enough that you should get a good and fairly deep understanding of object-oriented concepts in JavaScript. Although I wasn’t planning on an actual print book for this material, I am very happy with the result. So thanks to everyone involved – this has been a fun journey.

February 4, 2014

Maintainable Node.js JavaScript: Avoid process.exit()

I’ve spent the last few months digging into Node.js, and as usual, I’ve been keeping tabs on patterns and problems that I’ve come across. One problematic pattern that recently came up in a code review was the use of process.exit(). I’ve ended up finding several examples of this, and I’m prepared to go so far as to say there are very few places where calling process.exit() makes sense.

What it does

When you call process.exit() (and optionally pass in an exit code), you cause processing to stop. The exit event is fired, which is the last opportunity for any code to run, and the event loop is stopped. Shortly thereafter Node.js actually stops completely and returns the specified exit code. So process.exit() stops Node.js from doing anything tangible after that point and the application stops.

The problem

In and of itself, the ability to exit with a specified exit code isn’t a horrible thing. Many programming languages offer this capability and it’s relied upon for all kinds of processing, not the least of which are build tools. The real problem is that process.exit() can be called by any part of the application at any time. There is nothing preventing a parser from calling it:

exports.parse = function(text) {

if (canParse(text)) {

return doTheParse(text);

} else {

console.error("Can't parse the text.");

process.exit(1);

}

};

So if the text can be parsed then it is, but otherwise an error is output to the console and process.exit(1) is called. That’s an awful lot of responsibility for a lowly parser. I’m sure other parsers are jealous that this one gets to tell the entire consuming application to shut down.

Since any module can call process.exit(), that means any function call gone awry could decide to shut down the application. That’s not a good state to be in. There should be one are of an application that decides when and if to call process.exit() and what the exit code should be (that’s usually the application controller). Utilities and such should never use process.exit(), it’s way out of their realm of responsibility.

What to do instead

Anytime you’re thinking about using process.exit(), consider throw an error instead:

exports.parse = function(text) {

if (canParse(text)) {

return doTheParse(text);

} else {

throw new Error("Can't parse the text.");

}

};

Throwing an error has a similar effect as calling process.exit() in that code execution in this function stops immediately. However, calling functions have the opportunity to catch the error and respond to it in a graceful manner. If there is no intervention up the call stack, then the uncaughtException event is fired on process. If there are no event handlers, then Node.js will fire the exit event and exit with a non-zero exit code just like when process.exit() is called; if there are event handlers, then it is up to you to manually call process.exit() to specify the exit code to use.

The key is that throwing an error gives the application an opportunity to catch the error and recover from it, which is almost always the case when dealing with module code.

Conclusion

In your entire application there is likely only ever the need for one call to process.exit(), and that should be in the application controller. All other code, especially code in modules, should throw errors instead of using process.exit(). This gives the application an opportunity to recover from the error and do something appropriate rather than die in the middle of an operation. Calling process.exit()

Nicholas C. Zakas's Blog

- Nicholas C. Zakas's profile

- 106 followers