Nicholas C. Zakas's Blog, page 5

October 5, 2015

Triggering Jenkins builds by URL

As you might have read not too long ago, I recently moved my site from Wordpress to Jekyll[1]. In so doing, I ended up using Jenkins[2] to periodically build and upload my site to S3. Having a Jenkins instance running turns out to be quite useful for all sorts of tasks and so I've been trying to take advantage of it to automate more of my routine tasks.

The goals

Recently, I received some useful feedback from readers of my newsletter:

The default URL for archived newsletters looks suspicious. Here's an example: http://us11.campaign-archive2.com/?u=06398d19c8d37d8d6ba9d9cf7&id=7ab9b1fc75. Yeah, that looks pretty scary to anyone who knows anything about web security. I decided I'd try to figure out a way to generate an archive on my site.

Some folks wanted to subscribe via RSS instead of email. While Mailchimp does provide an RSS feed, it's of everything you send to a particular list. That means both my blog posts and newsletter updates are merged into the same feed, so I didn't have a feed of just newsletter updates. It seemed like having a feed could also help me with generating an archive page, so I decided this would be a nice first step.

Mailchimp supports webhooks, so it will post to any URL you want when it sends out an email. I wanted that to trigger generation of the archive page on my site so it would be available as soon as the email was sent. Jenkins allows you to trigger a build by posting to a URL, but it took me a little while to figure out exactly how to get this to work correctly.

Note: This assumes you're using Jenkins' own user database for user management rather than LDAP or another directory service.

Step 1: Setting up a new user

Trigger a build via URL means that the Jenkins endpoint is open to anyone who can hit the server. Naturally, that means you want to ensure you've secured this endpoint as much as possible and the first step is to create a user with limited access to Jenkins. To create a new user:

Click on Manage Jenkins

Click on Manage Users

Click on Create User

Fill in the information for your user (I'll assume you've called this user "auto")

Click the Sign Up button

This will take you back to the user list.

Step 2: Enable the URL job trigger

Go to the job that you want to trigger and click Configure to edit the job. Under Build Triggers, check the box next to "Trigger Builds Remotely". You'll be asked to provide a secure token for validation. This should not in any way be related to the "auto" user, so don't reuse the password. You might want to generate a new key using a tool like the Random Key Generator[3]. Click Save to save the job information.

;

;

Step 3: Enable permission for "auto"

In order to allow "auto" to trigger the build, the user needs to have the following permissions set:

Overall - Read

Job - Build

Job - Read

Job - Workspace

To configure these permissions:

Click on Manage Jenkins

Click on Configure Global Security

Assuming you're using matrix-based security: add "auto" to the list and check off the boxes for the necessary permissions

Click Save

If you are not using matrix-based security, then this step is likely not necessary. Just make sure the "auto" user has the correct permissions.

Step 4: Create the URL

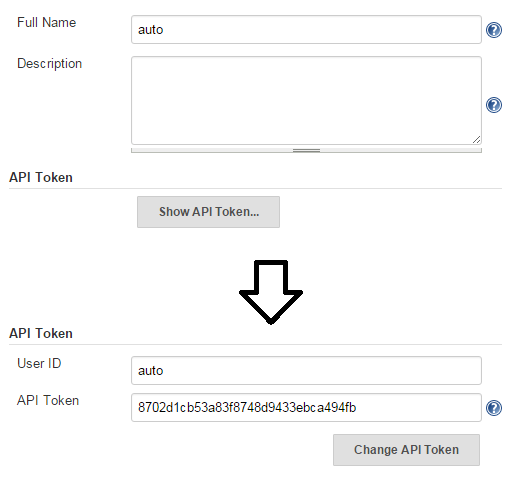

In order to make an external call using the "auto" user, you'll need to use an API token. From the user list, click on the "configure" icon (the wrench and screw driver) next to the "auto" user.

;

;

Underneath the user's full name and description is a section labeled "API Token". Click on the "Show API Token" button. This will reveal the API token you need to provide when triggering a job by URL.

;

;

With this information, you can now create a URL that looks like this:

http://auto:8702d1cb53a83f8748d9433eb...

Note that "JobName" should be replaced with the job name you're triggering. The correctly escaped version of this URL is shown when you set the authentication token (step 2).

This URL has three key pieces of information:

The username "auto"

The API token (after the colon)

The authentication token

All three must be correct, and the permissions for the user must be correct in Jenkins, in order for this URL to trigger the job. In order to trigger the job, you must send a POST request. You can test it out using cURL:

curl -X POST http://auto:8702d1cb53a83f8748d9433eb...

Once you send the request, log in to Jenkins and verify that the job is running. You can then use this URL for most webhooks.

Conclusion

I now have a job triggered remotely whenever Mailchimp sends an email. The script downloads the newsletter RSS feed, filters out blog posts, and generates an HTML archive page on my site. The most time-consuming part of the process was going setting up Jenkins to build via URL, as the resources I found online all had pieces of information missing. I hope that this post helps others make progress faster.

References

From Wordpress to Jekyll: My new blog setup by me (nczonline.net)

Jenkins (jenkins-ci.org)

Random Key Generator (randomkeygen.com)

September 21, 2015

My favorite interview question

Interviewing and hiring are more difficult tasks than they may seem. The cost of hiring the wrong person is quite high, yet companies that are hiring often want help sooner rather than later and so sometimes don't want to wait for a good candidate to come along. I operate on the mindset that the damage done by filling a position with a bad fit is far greater than the damage of not having enough people to do work, and so I believe in optimizing to find the right person for the job.

With that goal in mind, I have a favorite interview question that has helped me make a lot of hiring decisions over the years. I'm sure a few of you are thinking, "oh no, he's going to give away a good interview question and that will make it useless." Not so. I believe that a good interview process is one that is effective even when candidates know the questions ahead of time. I'm sharing this question specifically because I think it will help everyone, candidate and interviewer alike, by shifting focus to career aspirations.

The question

I rarely ask the question in the exact same way, but it usually takes this form:

Suppose you could design your dream job that you'll be starting on Monday. It's at your ideal company with your ideal job title and salary. All you have to do is tell them what you want to do at your job and you can have it. What does your job entail?

The question looks fairly simple at first glance, but there are some subtleties that help you dig in on important details.

"Starting on Monday"

The phrase "starting Monday" places the job in a specific time. It's clear that we're not talking about a position you will one day aspire to, nor are we talking about a dream job that can't actually exist. If a job is to start on Monday, you don't have time to learn new skills or gain experience. You are what you are, professionally, and you need to come up with a job that you can effectively perform next week.

Ideal company, title, and salary

I immediately exclude discussion of company, title, and salary, because these are the things people think they want but can't really affect my decision. Obviously the company is completely out of my control unless it's my current employer (I also don't want people sucking up to me by saying that my current employer is their dream job). I don't want to get into a discussion about titles because they are mostly meaningless; I'm not interested in what you want people to call you, I want to know what you're passionate about working on. And salary is, depending on the person, of variable importance and doesn't tell me much about the person. Yes, I would also like to have a $1 million salary per year, but that's not helpful in my evaluation of an candidate.

So by stating that these three things, company, title, and salary, are already taken care of, it frees candidates to think about what really matters to them.

Discussion

As should be obvious, this is not meant to have a one-sentence answer. Instead, I use it as a conversation starter to dig and find out what drives this person. Follow up questions and reacting to what they are saying helps me to figure out just how well this person would fit for the position. When trying this on your own, I'd encourage you to develop your own follow questions to dig deeper into the candidate's ideal job.

Getting stuck

Sometimes the scope of this question is too big for people to grasp and they get stuck. The enormity of defining any job they want can be overwhelming to certain people, and if that happens, I ask some followup questions to send them down the right path:

Let's start very simple: do you want to be writing code all day? If not, what else would you like to be doing?

Would you be working alone or on a team? If on a team, what role would you play on that team?

Is there a programming language you'd like to be spending most of your time in? What percentage of time would you need in that programming language to be happy?

Let's turn this around: what would you absolutely not want to do?

Is there something you'd like to spend time learning on your new job?

These questions are designed to get the candidate back on track (I never let people opt-out of the question). By helping to narrow down the job description to a few options, most candidates are able to continue down this path once they start.

Realistic self-view

The first thing I try to figure out is if this person's job description matches their skills. If a 22 year old tells me they want to be CEO of Google next week, for example, it looks like either their perspective on their skills is flawed or they didn't really grasp what I was asking. In that case, I say something like, "remember, you're starting this job on Monday. Are you ready to be CEO of Google on Monday?" If they say yes, then I'll probably entertain myself by asking how they'd run the company while mentally moving on to the next candidate.

IC vs. manager

I've periodically interviewed people for an individual contributor (IC) position and asked this question only to find that they really wanted to be a manager. Sometimes it's someone applying for a manager position who, underneath it all, really wants to be an IC. This is a really important data point to have because tend to get unhappy when in a position they're not picturing, and unhappy workers create problems (some small, some large). So if I have any hint that they may not be applying for the right role, I ask them to clarify, "so this ideal job would be in management?" Or, "this ideal job has no management responsibilities?"

Leader vs. follower

A slightly different take on IC vs. manager is whether someone is a leader or a follower. Here's the tricky part: leaders are more likely to tell you they feel they can and followers will almost never tell you they prefer to follow. Of course, you also can't really ask them directly because no one wants to be thought of as a follower. To determine this, you can look for key phrases they use:

I like to help other people

I feel like I have a lot of experience to share

I don't mind/I love mentoring others

By the way, if you're thinking you can trick someone into think you're a leader by using these phrases, you're wrong. They are just indicators to dig deeper, you're not going to trick someone who knows what they're doing.

Important: Both leaders and followers are important for a healthy team. Equally important is making sure you match people with the correct roles. Putting a follower into a leadership position is incredibly damaging to everyone, likewise forcing a leader into a follower position will lead to unhappiness. The goal here isn't to weed out followers, it's to make sure you're matching people to positions effectively.

Time spent

At some point during the discussion I usually ask people to break down how much of their time they'd like to spend on any particular task. Do they want a 50/50 split between coding work and management work? Do they want to spend 70% of their time designing and architecting and only 30% doing actual coding? Are they a manager who wants to spend 10% of their time coding to "stay in the game?" These are all important to understand to get a full understanding of the person.

Concluding

At the end of this question, I repeat back what the candidate told me. Something like:

Okay, so let me see if I have this correct. In your ideal job, you'd be spending 75% of the day writing code (JavaScript, if possible) and 25% of your day meeting with others to discuss technology and code. You'd prefer to be on a team of about 5 people and you'd like to be mentored by someone with more experience than you. Is that right?

If I get it wrong, I ask them to correct me so I have a good understanding. Once I have their answer correct, then I explain to them why I asked this question. Usually along the lines of:

The reason I ask this question to people is because I believe it's important to match people up to the correct position. I wanted to get to know you and your career goals to make sure we have a good fit for you. What I'd like to do now is tell you what I'm looking for and we can decide together if it seems like we have a fit. Does that sound okay?

At that point, I describe what the job they're applying for is like. I talk about the areas in which it is different from what they described and the areas in which it matches. Then, I offer my perspective on whether there's a fit and I ask them for theirs. This usually ends up in one of several paths:

It sounds to me like this isn't a great match for what you're looking for. Do you agree?

From what you've described, this seems like a job that mostly matches what you're looking for. What do you think?

It seems like this job is exactly what you're looking for. Do you agree?

When there's a good fit, the candidate feels better about continuing in the process because of this exercise. They understand that I'm not saying this is a great position for them to try to blindly sell them, but that I really understand what they're looking for and can honestly say I think it's a good fit.

I've never once had an argument with someone when I suggested it seemed like we didn't have a good match. In most cases, the candidates have thanked me for the exercise because it helped them really narrow in on what they're passionate about and what type of job they should be looking for. A couple times I've encouraged the candidate to apply to a different job at the company that seems more suited for what they're looking for. In all cases, candidates have told me they enjoyed answering the question.

Summary

I think getting to know a candidate is almost (almost!) more important than evaluating their skills. I've seen a lot of damage caused by hiring people into the wrong position due to mismatched expectations, and I'd like to avoid that at all costs. I also want candidates to know that I'm not trying to sell them something I don't have, nor am I making false promises about their chances of success when hired. Instead, I'm offering a complete view into the job they're applying for and, hopefully, a clearer view of their own goals and preferences.

I can honestly say this is the question I enjoy asking the most because reveal a lot about themselves. I think the key takeaway is that, regardless of the outcome, they feel listened to and that they were given a chance to really express how they see themselves fitting into an organization.

Ultimately, I feel that I have a responsibility to both my employer and the candidate to make sure we hire people that are good matches for the positions we have. The answers I receive from this question tell me very quickly how good of a match there is, at which point I feel better about spending more time digging into their credentials and skills. If I could only ask one interview question to every candidate, this would be the one.

September 7, 2015

Is the web platform getting too big?

Peter-Paul Koch recently wrote a blog post entitled, "Stop pushing the web forward" [1], in which he argued for a one-year moratorium on adding new features to the web platform. By new features, he means new APIs and capabilities in HTML, CSS, and JavaScript, arguing:

We're pushing the web forward to emulate native more and more, but we can't out-native native. We are weighed down by the millstone of an ever-expanding set of tools that polyfill everything we don't understand - and that's most of a browser's features nowadays. This is not the future that I want to push the web forward to.

The one-year moratorium, he argued, would give us all time to catch up on all the new features that have already been added. This, he continued, is really important because the pace at which new features are added is difficult for developers to deal with.

A lot of the responses to his post were disappointingly dismissive to the point of being rude (he was frequently publicly called a "grumpy old man" to rationalize his perceives wrongness), and I thought that was a shame because I think PPK hit on an issue that we're all facing: innovation fatigue.

Innovation fatigue

When I speak with more junior engineers, one of the most frequent questions I am asked looks like this:

How do you keep up with everything? Things are changing so fast, I feel like I'm always missing something, and then I get frustrated and think I should quit because everyone else seems to be on top of all the new stuff.

My response is usually something along the lines of this:

I don't. It's impossible to keep up with everything new that's coming out. Your goal should be only to be aware of things at a high-level until you need them. Skim over headlines or links shared by people on Twitter so you're aware of what's going on, but don't waste time trying to master everything. Wait until you need it.

Truth be told, I hate giving this advice. I remember a time when I felt like I knew everything about every browser (there were only two!). My first book, Professional JavaScript [2], I intended to contain everything you'd need to know about JavaScript and browser-based APIs. For the most part, I succeeded...until the third edition. That's when I realized that there was no way I could include everything anymore. And that made me sad.

So I think PPK was also channeling a bit of this sentiment in his post. As someone who spent an enormous amount of his personal time testing and documenting browser features and bugs, he must share my frustrations that the web isn't completely knowable by one person anymore. In fact, he said as much in his followup post [3]:

...part of my resistance to this idea is that I remember the old days when I could actually enumerate the features of each of the three browsers. (OLD days, I said.)

I'll admit it was nice to know everything for a while, though we were probably all too naive to realize that this wasn't a sustainable model. All occupations have an associated body of knowledge that practitioners dip into when they need to complete certain tasks. Visit any lawyer's or accountant's office and you'll find shelves filled with books that they use for reference. In the tech world, talk to any Java developer about how to deal with an exploding number of options for completing the same task, and you'll see that web developers have had it easy for a long time.

A moratorium?

I'm willing to bet that PPK didn't think his blog post would result in an actual moratorium, but it is worth looking at what happened during the forced moratorium that occurred when Internet Explorer 6 ruled the web. Once IE6 had effectively crushed Netscape, the Internet Explorer team was disbanded. Microsoft had won the web and there was no more work to do. At that point in time, IE6 was all the web there was and that meant no more new features.

The period of 2001-2006, five years of stagnation, actually turned out to be a good thing. As Douglas Crockford has mentioned in several of his talks, the stagnation gave developers some time to catch up to what already existed. To that point, the innovation had been rapid and the incompatible changes in Internet Explorer and Netscape meant you always had to learn two different ways of doing the same thing. It was exhausting and frustrating to make pages and applications that worked across both browsers because there just wasn't enough information about what to use in which situations. When all of a sudden there were no more features being added, we all could take a breather.

You'll note that the first edition of Professional JavaScript came out in 2005, towards the end of the stagnation period. I spent most of 2003 and 2004 writing that book, and felt like it encapsulated every important piece of JavaScript information that existed in the world. I wasn't alone, either, as blogs began to pop up and people started publishing their experiments with JavaScript and their understanding of how it worked.

That stagnation period is what gave Mozilla time to catch up with Firefox, it's what led to the Ajax revolution, and it's what ultimately unseated Microsoft as king of the web. So it's not a big jump to say that stagnation alone isn't a bad thing for the web. Maybe this stagnation period was an exception, but we can't know that for sure.

Is the web losing?

So what if we started a moratorium now? The main opponents to PPK's suggestion predict dire consequences in the form of lament that is now all too familiar to me: if we stop innovating, the web will lose. I've heard this refrain in many different forms over the years, "we need the web to win" or "we don't want the web to lose." What game are we playing? Who are the opponents? What are we doing that they aren't doing?

When you ask these questions enough, inevitably someone answers: native will destroy the web if we stop innovating. Now, I have no data suggesting that this isn't true, but I also have no data suggesting that it is. I'm also not convinced that this is really a native vs. web battle where there can only be one winner. However, if you hold this position, then I can understand why you'd fear a moratorium: stopping means falling behind while the opponent continues to innovate.

I'm not sure if such battle is ongoing, or if some are imagining a foe and a battle in order to push for new features. To me, the thought that native will overtake the web seems like a theoretical impossibility, especially as we see more native capabilities that are mirroring what's found in the web (i.e., React Native) and how hybrid mobile apps don't seem to be going away anytime soon.

Is native doing some cool stuff that would be great to have in web applications? Absolutely. But I hardly see this as a one-way street. More and more, it seems like native is trying to emulate the web development experience because it's faster, there's a built-in set of people with HTML, CSS, and JavaScript knowledge, and there are some great tools.

So, I'm not convinced the web is losing to anything, and I'm not convinced that between native and the web that there can be only one. I harken back to what Steve Jobs said when he returned to Apple in 1997:

If we want to move forward and see Apple healthy and prospering again, we have to let go of this notion that for Apple to win, Microsoft has to lose.

I feel the same about the web and native.

(If you have any research related to this topic, please post a link in the comments. I haven't been able to find any numbers to back up either that there's a war between the web and native or that one or the other is winning.)

Conclusion

I really appreciated PPK's willingness to stick his neck out and say something controversial to get people thinking and talking. In my heart, I'd love to see a moratorium, but that's mostly a selfish desire to stop trying to keep up with every new thing as it comes out. That's a path I've paved for myself and asking the world to change so I can stop walking that path isn't rational or realistic. Yet, I understand where PPK is coming from, as it's a sentiment that many developers share.

The rapid pace of web platform development is dizzying and it can, at times, be overwhelming. Imagine just starting out in the industry and discovering that you can never get ahead of the learning. Every six weeks (when new browsers are released), we need to augment how we do our work in some way. That's a pretty crazy roller coaster that I'm sure we'd all like a break from.

Yet at the same time, the innovation that we're experiencing means that solutions to our complex problems are more close than they are far away. We no longer have to go through years of experimentation, trying to find ways to work around the limitations of the browser. In some cases, if we can just wait a few months, the solution will be there.

In the meantime, I'll echo a point PPK made in his second article: what we really need is a single source of truth for the ongoing development of the web platform. I had hoped that webplatform.org [4] would fill this role, but it's not even close. What we really need is a home for the status of all web platform features, including standards work, browser implementations, and progress. If we could achieve this as a community, we could help the next generation of web developers tremendously. Instead of going to Edge's status page, Chrome's status page, searching GitHub, etc., we could go to one place and get all the information we need. That is a future worth fighting for.

References

Stop pushing the web forward by Peter-Paul Koch (quirksmode.org)

Professional JavaScript for Web Developers by me (amazon.com)

Stop pushing redux by Peter-Paul Koch (quirksmode.org)

WebPlatform.org

August 25, 2015

From Wordpress to Jekyll: My new blog setup

I had been thinking about moving my blog from Wordpress to Jekyll for a while. I was hesitant because I didn't know a lot about how Jekyll worked and wasn't sure if I'd ultimately want to have my site hosted on GitHub or not. I also was concern about not having the ability to schedule posts in the future. I used this feature quite frequently in Wordpress, especially as my energy goes up and down while battling Lyme disease. To me, not being able to schedule a post for later publishing was a deal-breaker, as I didn't want to manually push posts live all the time.

Looking over my hosting bill, however, made me realize I was severely overpaying for hosting my mostly-static-already site using Wordpress. I was paying $50 per quarter, or about $17 per month. In this day and age, that's an insane amount of money to pay for hosting a site that barely ever changes. I had been with this webhost for over a decade and the price had remained the same the entire time. Plus, the numerous Wordpress upgrades and countless security flaws were making me feel it was time to abandon Wordpress for a static site generator. So, I set about creating a plan to move my Wordpress-driven site to Jekyll.

Migrating comments

The first step in this process was to migrate my comments to Disqus. While I'm not a huge fan of Disqus, it was the simplest choice due to its ability to quickly integrate with Wordpress and then continue to function on a static site.

I started by installing the Wordpress Disqus Plugin, and it seamlessly integrated into my site. I then kicked off importing the comments into Disqus, only to find that this didn't quite work. I ended up needing to manually import comments, as the Disqus plugin only seemed to import a small number of comments each time I initiated it.

Exporting posts

Once I was certain the comments were safely migrated to Disqus, I looked for the best way to export the rest of my content. I eventually ended up using the Jekyll Exporter Plugin for Wordpress. After installation, you need only click "Export to Jekyll" to download a zip file of all content. I was impressed by this plugin's completeness as it included all tags, categories, permalinks, posts, and pages. Basically, you can unzip the result and serve that as a starting point for your converted site. It even copies files from your wp-content directory so you can keep track of images, stylesheets, and more.

The only thing the Jekyll exporter didn't do was provide any sort of layout from Wordpress. That makes sense, since all the layout information in Wordpress is in PHP. So, I had to manually grab the HTML from my Wordpress theme and migrate it over to Jekyll templates. I then put the Disqus JavaScript into the pages and was amazed to find that the comments all appeared.

Choosing a host

Initially I thought I would take advantage of GitHub Pages to host my site, as I know many others do. However, there were a few things I didn't like:

The aforementioned inability to schedule posts to be published in the future. Since GitHub doesn't give you a way to force-regenerate a site, that would mean either holding out posts until the day they are supposed to be published or else creating a dummy commit to force the site to regenerate. Neither of those appealed to me.

You can only use Jekyll plugin gems that GitHub has installed, so any additional functionality you want either needs to be hacked together or omitted. In my case, I wanted to generate yearly and monthly archives automatically. There's a jekyll-archives gem for that but it's not available on GitHub.

I wanted a test area where I could preview changes before pushing live. I could do that locally but since I'm on Windows, setting up Jekyll is pretty difficult (I've tried and given up three times). I could also have a separate GitHub repo for that purpose, but I really didn't want to have to manage two repos.

After doing some research, I realized I could host my static site on Amazon S3 for almost nothing the next year using the free tier. After that, the cost looks to be less than a dollar a month. So far, a significant savings from the $17 per month that I was paying for Wordpress hosting. Plus, S3 would serve as a solid backup for all of my content.

The deployment pipeline

Once I decided on S3 hosting, it became a matter of figuring out how to get the posts from the GitHub repository onto S3 and also how to schedule posts. It turned out the solution to both problems was the same: setup a Jenkins server.

In my mind I devised a simple strategy:

Check in files to git repo locally

Trigger a build when changes are pushed to master

The build checks out the remote git repo and runs Jekyll to generate the files

The build syncs the generated files with the files already on S3

If I could get that working, I reasoned, then I could set the same build to run automatically at midnight every night. That meant I could schedule posts for any point in the future and they would get generated only when appropriate.

I leaned heavily on the article, Trigger Jenkins builds by pushing to GitHub, to get my setup working. I used a micro instance on AWS because it's free for the first year, though I'll likely switch to DigitalOcean after the first year ($5 per month vs. roughly $10 per month for an on-demand micro AWS instance).

I ended up using S3Cmd for syncing with S3. I tried using the AWS CLI first, but its syncing capability is limited to file size and last modified date. Since each build is regenerating the entire site, the last modified date was always different and so the files were always being synced even though they were no different. S3Cmd, on the other hand, also checks the content of the file to see if there's a difference before syncing. That one change meant I went from 2,000 PUT requests each build to roughly three PUT requests on average.

Ultimately, the Jenkins setup has worked well. The same build is triggered by a push to the GitHub repo's master branch and automatically at midnight each night. By setting future: false in my _config.yml file, any future posts I write will not be generated until the correct date. I'm using tha latest GitHub Pages gem, so the configuration is compatible with what's being used on GitHub itself.

Serving traffic

Initially, I thought I'd be able to serve all traffic directly from S3. While possible, S3 does not compress files automatically, so all of my HTML, CSS, and JavaScript would be sent in its original form (thus using more bandwidth and costing me more). I first looked at using Cloudfront, the AWS CDN service, to front S3. However, Cloudfront also does not do any compression of requests (which shocked me).

Several people on Twitter recommended using CloudFlare instead. CloudFlare does compression of assets, along with other optimizations, DDoS protection, and free SSL, and they have a free tier. Even better, CloudFlare caches requests on their CDN for a specified amount of time, meaning that I'll be avoiding more requests to S3 than necessary (another cost savings).

Unfortunately, being new to S3 hosting, I made a rookie mistake: I named my buckets wrong. I was unaware that the bucket name must be the domain name you want to serve the content (a restriction I find strangely arbitrary). My initial bucket was named "nczonline", so I created a new one named "nczonline.net". The big mistake is that I did not create a bucket named "www.nczonline.net", and that was apparent to anyone who visited my site during the transition thanks to some misconfiguration. During that time, someone created a bucket named "www.nczonline.net", and since bucket names are universal, that meant I no longer could. That also meant I couldn't serve traffic directly from www.nczonline.net to S3 due to the AWS naming restrictions. I could serve from nczonline.net, but I had that setup to redirect to www.nczonline.net in order to make use of free email forwarding (that apparently couldn't work with the apex domain set as a CNAME).

I didn't want to abandon the idea of serving from S3, so I realized I needed something in between CloudFlare and S3 to make the S3 requests in such a way that would allow serving from www.nczonline.net. I ended up setting up Nginx on the same AWS micro instance and used that as a proxy to S3. After some trial and error, I realized that S3 was simply looking at the Host header to determine whether it should serve traffic or not, so I was able to work around that pretty easily with the following configuration:

server {

# Listen for traffic - old school and new

listen 80 default_server;

listen [::]:80 default_server ipv6only=on;

# Setup the hostnames that are allowed for this server

server_name nczonline.net www.nczonline.net;

# Proxy all requests to AWS

location / {

proxy_set_header Host nczonline.net;

proxy_pass http://nczonline.net.s3-website-us-we...

}

}

With Nginx set up to point to S3, I pointed CloudFlare at Nginx, and my site was finally working correctly. As a bonus, Nginx compresses HTML, CSS, JavaScript, etc. automatically, so I got some additional cost savings.

At this point, I could have simply pointed my domain name to Nginx and used that without CloudFlare. However, CloudFlare's edge caching, DDoS protection, and free SSL features (plus the cost: free) led me to believe that it was still advantageous to use.

Worth it?

Setting up this system was a bit more work than I expected, but I definitely think the effort was worthwhile. I learned a lot about AWS, GitHub, and Jenkins. I now have a much better understanding of the tradeoffs you make when serving content from S3, as well as the various restrictions. Mostly, though, I'm happy that I'm in complete control of the stack for my blog. Using Wordpress always made me a bit scared - performance issues, database corruption, and security holes were always on my mind. Plus, I hated the idea of my content being stuck in a database somewhere. I do most of my writing in Markdown these days, so having my site content in that format and versioned in a git repository was the idea that most appealed to me. No matter what happens, I'll always have easy access to that content.

July 16, 2015

Announcing the NCZOnline Newsletter

For a while, I’ve been toying with the idea of writing more short form content. While I love the long form of writing, it does take a lot of energy and as such I’ve been unable to do the regular amount of writing that I normally do. I thought about doing short form content on the blog, but it just seemed to be a bit out of place. Meanwhile, I had started doing a weekly email at work with useful and important links I’d read recently and got some really good feedback from that. Over the course of the past several weeks, the idea of having a public newsletter that combined short form writing and recommended links grew on me, both as a way to encourage me to keep writing and as a way to share what I’ve been reading and why I think it’s important.

And so, the NCZOnline Newsletter will be starting in August and be sent every two weeks on Tuesday, with the first edition coming out August 4. Here’s what you can expect in each edition:

A short form essay on the same topics you see on my blog: JavaScript, web development, software engineering, technical leadership, architecture, teamwork, and generally any topic that will help you become a better software engineer. This content will be unique and not part of my blog.

Links to three things (videos, articles, podcasts) that I think everyone needs to see. These won’t all necessarily be recent, but they will all be guaranteed to be worth your time. (If you want a list of recent happenings in the JavaScript world, then JavaScript Weekly is what you’re looking for.)

A recommended book. Once again, this won’t necessarily be only technical books, but rather, books that can make you a better, more well-rounded software engineer and person.

Discounts! I periodically receive discount codes for various things (books, conferences, etc.), and I’ll be sharing those with you as I receive them.

You can sign up by using the form at the bottom of this page (if you’re reading this on my blog) or by using the standalone signup form (if you’re reading this via RSS or email). Your email address will never be sold or shared, and you can unsubscribe at any point in time with a link in each newsletter. If you had previously signed up for updates by mail, then you will receive the newsletter as well. It’s still possible to receive just blog post updates and not the email newsletter (or vice versa) by updating your preferences on the signup form.

I’m currently looking for sponsors for the newsletter. While I’m happy to provide the newsletter for free, the software and services I use do cost money, and I’m looking for a way to offset those costs. If you’re interested in sponsoring the newsletter (even for just one edition), please contact me.

My goal with this newsletter is to make it feel like I’m mentoring each subscriber (sharing stories and links are both what I do with those I’m mentoring in real life). As such, you’ll be able to reply to each newsletter to send a message to me, and I guarantee I will read every single email. I expect the newsletter to evolve based on subscriber feedback so that it’s really a conversation rather than a monologue. I hope you’ll join me.

July 15, 2015

Announcing the NCZOnline Newsletter

For a while, I’ve been toying with the idea of writing more short form content. While I love the long form of writing, it does take a lot of energy and as such I’ve been unable to do the regular amount of writing that I normally do. I thought about doing short form content on the blog, but it just seemed to be a bit out of place. Meanwhile, I had started doing a weekly email at work with useful and important links I’d read recently and got some really good feedback from that. Over the course of the past several weeks, the idea of having a public newsletter that combined short form writing and recommended links grew on me, both as a way to encourage me to keep writing and as a way to share what I’ve been reading and why I think it’s important.

And so, the NCZOnline Newsletter will be starting in August and be sent every two weeks on Tuesday, with the first edition coming out August 4. Here’s what you can expect in each edition:

A short form essay on the same topics you see on my blog: JavaScript, web development, software engineering, technical leadership, architecture, teamwork, and generally any topic that will help you become a better software engineer. This content will be unique and not part of my blog.

Links to three things (videos, articles, podcasts) that I think everyone needs to see. These won’t all necessarily be recent, but they will all be guaranteed to be worth your time. (If you want a list of recent happenings in the JavaScript world, then JavaScript Weekly is what you’re looking for.)

A recommended book. Once again, this won’t necessarily be only technical books, but rather, books that can make you a better, more well-rounded software engineer and person.

Discounts! I periodically receive discount codes for various things (books, conferences, etc.), and I’ll be sharing those with you as I receive them.

You can sign up by using the form at the bottom of this page (if you’re reading this on my blog) or by using the standalone signup form (if you’re reading this via RSS or email). Your email address will never be sold or shared, and you can unsubscribe at any point in time with a link in each newsletter. If you had previously signed up for updates by mail, then you will receive the newsletter as well. It’s still possible to receive just blog post updates and not the email newsletter (or vice versa) by updating your preferences on the signup form.

I’m currently looking for sponsors for the newsletter. While I’m happy to provide the newsletter for free, the software and services I use do cost money, and I’m looking for a way to offset those costs. If you’re interested in sponsoring the newsletter (even for just one edition), please contact me.

My goal with this newsletter is to make it feel like I’m mentoring each subscriber (sharing stories and links are both what I do with those I’m mentoring in real life). As such, you’ll be able to reply to each newsletter to send a message to me, and I guarantee I will read every single email. I expect the newsletter to evolve based on subscriber feedback so that it’s really a conversation rather than a monologue. I hope you’ll join me.

June 23, 2015

Why you’re afraid of public speaking

One of the most common questions I’m asked is how to get started with public speaking. My answer is always the same: just start doing it. That’s usually when the terror crosses the questioner’s face, as if they had expected me to reveal some secret ninja training that makes you a confident and capable public speaker. I can see the moment they picture themselves standing in front of a crowd because their whole body tenses up. They’re nervous just thinking about it!

Being nervous

Being nervous is something I’m intimately familiar with. In my teenage years I suffered from severe social anxiety that I found crippling. It took me several years of therapy to finally break through, and that happened to coincide with when I took the leap of auditioning for the school play at 16.

Later, when I contracted Lyme disease, I developed debilitating anxiety attacks. I’m talking about staying in bed under the covers all day anxiety. This time, I needed medication just to get through certain days.

So if public speaking makes you nervous, I hear you. Here’s my big secret: it still makes me nervous. Every damn time. The difference is that I know I can do it, I know I can and will mess up and the world won’t end. I accept the nervousness for what it is.

What is nervousness?

I like to think of nervousness as my body telling me something is odd about this situation. It’s like an early alert system that while there’s no immediate danger, danger is a possibility. Nervousness starts your fight-or-flight response so you can be ready but doesn’t necessitate immediate action.

Fear is the sign of verifiable danger. It’s your body’s, “oh shit” response. When you feel fear, you need to act now, either by hiding (running away… or cowering under your blankets) or by preparing to fight. Fear is your body’s way of telling you to stop whatever it is you’re doing and pay attention.

In some cases, you first feel nervous and then feel fear; this is common for public speaking. In other cases, you skip feeling nervous and go directly to fear; I’m terrified of heights, when faced with a situation that tests that, I stop functioning altogether. Anyone who has a phobia will probably tell you the same story.

Evolution

All this is to say that both nervousness and fear are your body’s way of telling you something about your surroundings. We evolved to have these responses because they could save us from death. Feeling nervous when entering an area could mean a predator is nearby. Feeling afraid means you know your life is in danger from someone or something, so you better do something about it.

Now think about the room of a conference. There are maybe 200 strangers all facing in one direction watching your every move. If you were to place such a scene back in caveman days, you would be well served to get nervous or afraid. The chances those 200 people wanted to hear you speak, especially given the lack of spoken language at the time, was pretty slim. It was far more likely that your time was up and those strangers were there to make quick work of you.

Even moving that situation to present time isn’t any better. Imagine if you left your front door and were immediately met with 200 strangers looking at you…still pretty creepy.

So no wonder we all get afraid in front of an audience. There’s something incredibly primal about that reaction. I’ve seen this firsthand by talking with people about their public speaking fears. Most of the time, they start out with, “I get so nervous,” or, “I feel afraid.” When I ask what they are afraid of, most need to think about it before they start rattling off answers: what if I forget what I’m saying? What if I sound dumb? What if they don’t like me?

All of these are rationalizations their mind comes up with to explain the fear or nervousness. They feel uncomfortable first, then the mind gives plausible explanations about why the feeling is present. That’s what evolution had left us with: an early warning system that we can explain after the fact.

Combating nervousness

The point I’m trying to make is that trying to eliminate nervousness from public speaking probably won’t work unless you become a master of some kind of esoteric meditation practice. For the rest of us, we will likely feel nervous because the situation is, evolutionarily speaking, very odd and disconcerting. Given that, what can you do?

First, accept that feeling nervous is just part of the package. It’s not a judgment on your strength, aptitude, or confidence…it’s a constant that is not within your control any more than the weather. You might see it’s raining and grab an umbrella, but that’s about the best you can do.

Next, accept the feeling of nervousness in your body. This is unnatural because we are wired to react to nervousness, but you can choose the reaction. My social anxiety therapist gave me some great advice that I still pass on to others, it went something like this:

What’s the first thing you do when you feel nervous? You get nervous that you’re getting nervous, so you feel worse. Then you feel nervous that you got nervous about getting nervous, and before you know it, you’re a wreck. So the trick is, when you notice you’re nervous, just let yourself be nervous because at that point, it’s not that big a deal. What makes it a big deal is the cycle of worrying it kicks off rather than the feeling itself.

This made logical sense to me even as a 14 year old, which is probably why it has stuck with me for so long. It’s also very much in line with mindfulness training: when you feel nervous, accept that you feel nervous, say, “I’m feeling nervous,” and learn to sit with the feeling instead of fighting it.

Last, do everything in your control to limit the amount of anxiety you will feel on the day of the talk. For me, not having my talk finished and rehearsed a couple of times makes me even more nervous. Consequently, my talks tend to be fully formed two weeks before I give them for the first time.

I’m also afraid of not knowing where I’m supposed to speak, so I usually do a scouting mission for the building, and if possible, the room sometime before the talk. When I’m on, I don’t want to be late, so this information helps me greatly.

Another personal oddity: speaking on a full stomach makes me more nervous. That heavy feeling in my gut doesn’t mesh well with the butterflies. As a result, I won’t eat any food in the two hours leading up to my talk. If I’m hungry, I’ll eat something very small, just small enough to do the hunger pains. (After the talk, I usually eat a large-ish meal.)

Everyone has quirks like this. If you can identify the extra things that make you nervous and take care of them ahead of time, you’ll feel much better for the talk. Whatever you do, don’t stack the deck against yourself. Don’t make the experience even more anxiety-provoking than it already is by staying up all night the night before the talk, downing a bunch of caffeine, or having your slides unfinished the day of the talk. These situations are hard even for experienced speakers, so if you can avoid them, please do.

The power of ritual

Having a speaking ritual, a series of things you do leading up to your talk, also helps to keep the nervousness under control. Rituals give you a safe autopilot leading up to the talk. Here’s my ritual:

Arrive two hours early

Locate room I’ll be speaking in

Locate nearest bathroom to that room

Find some water

Talk to someone (anyone) casually to get into a social mindset

An hour before the talk: find a quiet place to review my slides

Half hour before the talk: go to the room to see what’s going on (is there a talk before mine?)

15 minutes before the talk: go to the bathroom

10 minute before the talk: setup my computer and slides

Start of talk: say “hi”

That last step, saying “hi,” is an important part of the ritual for me. I know from experience that once I start talking, I’ll get into a groove and I won’t feel the nerves anymore. I spent a lot of time figuring out how to get into that groove as quickly as possible. One day it occurred to me: just start talking! Since I knew I’d be nervous, I wanted something simple and easy to remember. Eventually, after some trial and error, I landed on, “hi.” Sometimes it’s hard for me to get that out, sometimes it’s easy, but all the time it kicks me into speaking mode. Pretty much every talk I have given the last two years I gave talks (pre-2014) began we me saying, “hi,” and pausing.

Conclusion

There’s nothing about public speaking that is normal. From an evolutionary perspective, it is a strange situation, and as such, it’s completely normal to feel nervous about it. But being nervous doesn’t mean you can’t still do it. Most people are nervous in front of a crowd, and it’s something you can deal with. Just remember, the nervousness is designed to warn you of potential danger, but there’s no real danger. You can thank your body for the consideration and calmly say, “I got this.”

June 22, 2015

Why you’re afraid of public speaking

One of the most common questions I’m asked is how to get started with public speaking. My answer is always the same: just start doing it. That’s usually when the terror crosses the questioner’s face, as if they had expected me to reveal some secret ninja training that makes you a confident and capable public speaker. I can see the moment they picture themselves standing in front of a crowd because their whole body tenses up. They’re nervous just thinking about it!

Being nervous

Being nervous is something I’m intimately familiar with. In my teenage years I suffered from severe social anxiety that I found crippling. It took me several years of therapy to finally break through, and that happened to coincide with when I took the leap of auditioning for the school play at 16.

Later, when I contracted Lyme disease, I developed debilitating anxiety attacks. I’m talking about staying in bed under the covers all day anxiety. This time, I needed medication just to get through certain days.

So if public speaking makes you nervous, I hear you. Here’s my big secret: it still makes me nervous. Every damn time. The difference is that I know I can do it, I know I can and will mess up and the world won’t end. I accept the nervousness for what it is.

What is nervousness?

I like to think of nervousness as my body telling me something is odd about this situation. It’s like an early alert system that while there’s no immediate danger, danger is a possibility. Nervousness starts your fight-or-flight response so you can be ready but doesn’t necessitate immediate action.

Fear is the sign of verifiable danger. It’s your body’s, “oh shit” response. When you feel fear, you need to act now, either by hiding (running away… or cowering under your blankets) or by preparing to fight. Fear is your body’s way of telling you to stop whatever it is you’re doing and pay attention.

In some cases, you first feel nervous and then feel fear; this is common for public speaking. In other cases, you skip feeling nervous and go directly to fear; I’m terrified of heights, when faced with a situation that tests that, I stop functioning altogether. Anyone who has a phobia will probably tell you the same story.

Evolution

All this is to say that both nervousness and fear are your body’s way of telling you something about your surroundings. We evolved to have these responses because they could save us from death. Feeling nervous when entering an area could mean a predator is nearby. Feeling afraid means you know your life is in danger from someone or something, so you better do something about it.

Now think about the room of a conference. There are maybe 200 strangers all facing in one direction watching your every move. If you were to place such a scene back in caveman days, you would be well served to get nervous or afraid. The chances those 200 people wanted to hear you speak, especially given the lack of spoken language at the time, was pretty slim. It was far more likely that your time was up and those strangers were there to make quick work of you.

Even moving that situation to present time isn’t any better. Imagine if you left your front door and were immediately met with 200 strangers looking at you…still pretty creepy.

So no wonder we all get afraid in front of an audience. There’s something incredibly primal about that reaction. I’ve seen this firsthand by talking with people about their public speaking fears. Most of the time, they start out with, “I get so nervous,” or, “I feel afraid.” When I ask what they are afraid of, most need to think about it before they start rattling off answers: what if I forget what I’m saying? What if I sound dumb? What if they don’t like me?

All of these are rationalizations their mind comes up with to explain the fear or nervousness. They feel uncomfortable first, then the mind gives plausible explanations about why the feeling is present. That’s what evolution had left us with: an early warning system that we can explain after the fact.

Combating nervousness

The point I’m trying to make is that trying to eliminate nervousness from public speaking probably won’t work unless you become a master of some kind of esoteric meditation practice. For the rest of us, we will likely feel nervous because the situation is, evolutionarily speaking, very odd and disconcerting. Given that, what can you do?

First, accept that feeling nervous is just part of the package. It’s not a judgment on your strength, aptitude, or confidence…it’s a constant that is not within your control any more than the weather. You might see it’s raining and grab an umbrella, but that’s about the best you can do.

Next, accept the feeling of nervousness in your body. This is unnatural because we are wired to react to nervousness, but you can choose the reaction. My social anxiety therapist gave me some great advice that I still pass on to others, it went something like this:

What’s the first thing you do when you feel nervous? You get nervous that you’re getting nervous, so you feel worse. Then you feel nervous that you got nervous about getting nervous, and before you know it, you’re a wreck. So the trick is, when you notice you’re nervous, just let yourself be nervous because at that point, it’s not that big a deal. What makes it a big deal is the cycle of worrying it kicks off rather than the feeling itself.

This made logical sense to me even as a 14 year old, which is probably why it has stuck with me for so long. It’s also very much in line with mindfulness training: when you feel nervous, accept that you feel nervous, say, “I’m feeling nervous,” and learn to sit with the feeling instead of fighting it.

Last, do everything in your control to limit the amount of anxiety you will feel on the day of the talk. For me, not having my talk finished and rehearsed a couple of times makes me even more nervous. Consequently, my talks tend to be fully formed two weeks before I give them for the first time.

I’m also afraid of not knowing where I’m supposed to speak, so I usually do a scouting mission for the building, and if possible, the room sometime before the talk. When I’m on, I don’t want to be late, so this information helps me greatly.

Another personal oddity: speaking on a full stomach makes me more nervous. That heavy feeling in my gut doesn’t mesh well with the butterflies. As a result, I won’t eat any food in the two hours leading up to my talk. If I’m hungry, I’ll eat something very small, just small enough to do the hunger pains. (After the talk, I usually eat a large-ish meal.)

Everyone has quirks like this. If you can identify the extra things that make you nervous and take care of them ahead of time, you’ll feel much better for the talk. Whatever you do, don’t stack the deck against yourself. Don’t make the experience even more anxiety-provoking than it already is by staying up all night the night before the talk, downing a bunch of caffeine, or having your slides unfinished the day of the talk. These situations are hard even for experienced speakers, so if you can avoid them, please do.

The power of ritual

Having a speaking ritual, a series of things you do leading up to your talk, also helps to keep the nervousness under control. Rituals give you a safe autopilot leading up to the talk. Here’s my ritual:

Arrive two hours early

Locate room I’ll be speaking in

Locate nearest bathroom to that room

Find some water

Talk to someone (anyone) casually to get into a social mindset

An hour before the talk: find a quiet place to review my slides

Half hour before the talk: go to the room to see what’s going on (is there a talk before mine?)

15 minutes before the talk: go to the bathroom

10 minute before the talk: setup my computer and slides

Start of talk: say “hi”

That last step, saying “hi,” is an important part of the ritual for me. I know from experience that once I start talking, I’ll get into a groove and I won’t feel the nerves anymore. I spent a lot of time figuring out how to get into that groove as quickly as possible. One day it occurred to me: just start talking! Since I knew I’d be nervous, I wanted something simple and easy to remember. Eventually, after some trial and error, I landed on, “hi.” Sometimes it’s hard for me to get that out, sometimes it’s easy, but all the time it kicks me into speaking mode. Pretty much every talk I have given the last two years I gave talks (pre-2014) began we me saying, “hi,” and pausing.

Conclusion

There’s nothing about public speaking that is normal. From an evolutionary perspective, it is a strange situation, and as such, it’s completely normal to feel nervous about it. But being nervous doesn’t mean you can’t still do it. Most people are nervous in front of a crowd, and it’s something you can deal with. Just remember, the nervousness is designed to warn you of potential danger, but there’s no real danger. You can thank your body for the consideration and calmly say, “I got this.”

May 14, 2015

The bunny theory of code

Anyone who’s ever worked with me knows that I place a very high value on what ends up checked-in to a source code repository. The reason for this is very simple: once code gets checked-in, it takes on a life of its own. Checking in is akin to sharing your code with others, and once out in the world, it’s hard to predict what that code will do. Hard, but not impossible, as there is one thing I can virtually guarantee will happen.

For years, I’ve shared with friends and clients what I call the bunny theory of code. The theory is that code multiplies when you’re not looking, not unlike bunnies that tend to multiply when you’re not looking. This isn’t to say that multiplying code is good or bad – it’s a characteristic of all code regardless of quality. What makes it good or bad is the quality of the code being multiplied.

The reason the bunny theory of code has held up is because of the way software engineers work. We rarely, if ever, start with a completely blank file and start writing code. More often that not we start by copying an existing file and then modifying it to get our result. Once again, this isn’t good or bad, it’s just the most efficient way to create something that is similar to something else.

And where do you look for existing files to copy? In the same source code repository. The false promise of your source code repository is that everything it contains is “good.” To complete your task, just find something that does something similar, copy, modify, and you’re done. Looking inside the same repository seems like a safety mechanism for quality but, in fact, there is no such guarantee.

When you check in a file it’s not long before another similar file appears. Once there are two examples of the same thing, the chances increase that a third will be introduced. Once a third appears, the code has established a base in your repository and is now considered an approved pattern. After all, if we’re doing the same thing in a bunch of places, it must be the correct way to do things…right?

Back in 2005, I found some code at work that seemed to fit my task. As I highlighted the code to copy into my own file, I noticed I had skipped the long comment in front of it. While I can’t remember the exact wording, the comment basically said this:

Do not copy this code! I couldn’t figure out any other way to do this, and we are only doing it in one place, so this seems okay. If you think you need to do this somewhere else, then you should figure out the right way to do it. You should under no circumstances copy this code to somewhere else.

I laughed…then panicked. You mean I have to figure out how to do this exact thing in some other way? That seems unfair. The original engineer knew that they hadn’t properly solved the problem and left it as a landmine for someone else. It just so happened that I stepped on it and now couldn’t remove my foot until it was properly disarmed.

This is the problem when bad code gets into source control: it increases the likelihood that someone will find it and copy it. Once it’s been copied one time, that increases the likelihood it will be copied again, and so on. Before you know it, the bad code has infiltrated all parts of the repository and is hard to extract.

The problem grows as the number of people committing code to the same repository grows. When you have a team of a significant size, managing what ends up in source control becomes incredibly important because it will multiply quickly. As such, you want to make sure the code that gets checked in is as high quality as possible and represents what you want others to do.

To keep a sane codebase, your focus should first be on how to prevent that first piece of bad code from getting into source control. Enforcing or disallowing patterns through automation is important to that end. The more you can automate and physically block code from entering the repository, the safer everyone will be. Of course, there are some patterns that are hard to block, especially if they’ve never been encountered before. That’s where code reviews come in. There’s no better detector of the strange than the human eye.

Of course, some patterns aren’t demonstrably “bad,” they are just not what you want everyone doing. Consider the case of a third-party library like jQuery. Suppose you don’t want team members using jQuery because you have established patterns to accomplish the same tasks that jQuery can do. At some point, someone decides that using jQuery would be better and so adds it in. This might be hard to detect automatically, however, a human code review would catch this easily. This is the critical point: if jQuery makes it into the repository, it’s a virtual certainty that others will start using it, too. At that point, you’ll need to either work to pull it back out or accept it and let others use it, too. In either case, you’re doing work that you didn’t plan on and that’s almost always a bad thing, especially on a large team. Introducing a new library means needing to learn all about its quirks, its bugs, its best practices, and there’s not always time to do that.

In my current role at Box, I’m famous for repeating the phrase, “no accidental standards.” We don’t accept that things are “the way” just because they pop up in a couple of places. When we see this happening, we stop, discuss it, and either codify it as “the way” or disallow it. We then update code appropriately before it gets too far. Through automation, code reviews, and code workshops[1], we are able to keep an eye on the code and make sure we’re all on the same page.

While it may seem like a lot of work to manage a source code repository in this way, it’s actually more work to not manage it. Letting code grow unencumbered by human intervention is a great way to end up with a big mess. Engineers try to do the right thing, and they do that by copying what’s already in source control. It’s completely natural and expected to do that. That’s why you want to ensure that the code being copied represents what you want them to do and you’re prepared for more copies of that code to appear.

Just like bunnies, if you’re prepared for the multiplication, there’s not a big problem. It’s when multiplication happens without anyone noticing that trouble begins.

References

Effective learning through code workshops by me (Box Tech Blog)

May 13, 2015

The bunny theory of code

Anyone who’s ever worked with me knows that I place a very high value on what ends up checked-in to a source code repository. The reason for this is very simple: once code gets checked-in, it takes on a life of its own. Checking in is akin to sharing your code with others, and once out in the world, it’s hard to predict what that code will do. Hard, but not impossible, as there is one thing I can virtually guarantee will happen.

For years, I’ve shared with friends and clients what I call the bunny theory of code. The theory is that code multiplies when you’re not looking, not unlike bunnies that tend to multiply when you’re not looking. This isn’t to say that multiplying code is good or bad – it’s a characteristic of all code regardless of quality. What makes it good or bad is the quality of the code being multiplied.

The reason the bunny theory of code has held up is because of the way software engineers work. We rarely, if ever, start with a completely blank file and start writing code. More often that not we start by copying an existing file and then modifying it to get our result. Once again, this isn’t good or bad, it’s just the most efficient way to create something that is similar to something else.

And where do you look for existing files to copy? In the same source code repository. The false promise of your source code repository is that everything it contains is “good.” To complete your task, just find something that does something similar, copy, modify, and you’re done. Looking inside the same repository seems like a safety mechanism for quality but, in fact, there is no such guarantee.

When you check in a file it’s not long before another similar file appears. Once there are two examples of the same thing, the chances increase that a third will be introduced. Once a third appears, the code has established a base in your repository and is now considered an approved pattern. After all, if we’re doing the same thing in a bunch of places, it must be the correct way to do things…right?

Back in 2005, I found some code at work that seemed to fit my task. As I highlighted the code to copy into my own file, I noticed I had skipped the long comment in front of it. While I can’t remember the exact wording, the comment basically said this:

Do not copy this code! I couldn’t figure out any other way to do this, and we are only doing it in one place, so this seems okay. If you think you need to do this somewhere else, then you should figure out the right way to do it. You should under no circumstances copy this code to somewhere else.

I laughed…then panicked. You mean I have to figure out how to do this exact thing in some other way? That seems unfair. The original engineer knew that they hadn’t properly solved the problem and left it as a landmine for someone else. It just so happened that I stepped on it and now couldn’t remove my foot until it was properly disarmed.

This is the problem when bad code gets into source control: it increases the likelihood that someone will find it and copy it. Once it’s been copied one time, that increases the likelihood it will be copied again, and so on. Before you know it, the bad code has infiltrated all parts of the repository and is hard to extract.

The problem grows as the number of people committing code to the same repository grows. When you have a team of a significant size, managing what ends up in source control becomes incredibly important because it will multiply quickly. As such, you want to make sure the code that gets checked in is as high quality as possible and represents what you want others to do.

To keep a sane codebase, your focus should first be on how to prevent that first piece of bad code from getting into source control. Enforcing or disallowing patterns through automation is important to that end. The more you can automate and physically block code from entering the repository, the safer everyone will be. Of course, there are some patterns that are hard to block, especially if they’ve never been encountered before. That’s where code reviews come in. There’s no better detector of the strange than the human eye.

Of course, some patterns aren’t demonstrably “bad,” they are just not what you want everyone doing. Consider the case of a third-party library like jQuery. Suppose you don’t want team members using jQuery because you have established patterns to accomplish the same tasks that jQuery can do. At some point, someone decides that using jQuery would be better and so adds it in. This might be hard to detect automatically, however, a human code review would catch this easily. This is the critical point: if jQuery makes it into the repository, it’s a virtual certainty that others will start using it, too. At that point, you’ll need to either work to pull it back out or accept it and let others use it, too. In either case, you’re doing work that you didn’t plan on and that’s almost always a bad thing, especially on a large team. Introducing a new library means needing to learn all about its quirks, its bugs, its best practices, and there’s not always time to do that.

In my current role at Box, I’m famous for repeating the phrase, “no accidental standards.” We don’t accept that things are “the way” just because they pop up in a couple of places. When we see this happening, we stop, discuss it, and either codify it as “the way” or disallow it. We then update code appropriately before it gets too far. Through automation, code reviews, and code workshops1, we are able to keep an eye on the code and make sure we’re all on the same page.

While it may seem like a lot of work to manage a source code repository in this way, it’s actually more work to not manage it. Letting code grow unencumbered by human intervention is a great way to end up with a big mess. Engineers try to do the right thing, and they do that by copying what’s already in source control. It’s completely natural and expected to do that. That’s why you want to ensure that the code being copied represents what you want them to do and you’re prepared for more copies of that code to appear.

Just like bunnies, if you’re prepared for the multiplication, there’s not a big problem. It’s when multiplication happens without anyone noticing that trouble begins.

References

Effective learning through code workshops by me (Box Tech Blog)

Nicholas C. Zakas's Blog

- Nicholas C. Zakas's profile

- 106 followers