Nicholas C. Zakas's Blog, page 3

September 2, 2019

Securing persistent environment variables using ZEIT Now

I’m a big fan of ZEIT Now1 as an application hosting provider. The way the service abstracts all of the cloud computing details and allows teams to focus on building and deploying web applications is fantastic. That said, I had a lot of trouble setting up secure environment variables for my first application to use. I was used to other services like Netlify2 and AwS Lambda3 exposing environment variables in the web interface to allow secure transmission of important information. When ZEIT Now didn’t provide the same option in its web interface, I had to spend some time researching how to securely set persistent environment variables on my application.

For the purposes of this post, assume that you need to set two environment variables, CLIENT_ID and CLIENT_SECRET. These values won’t change between deployments (presumably because they are used to authenticate the application with OAuth). As such, you don’t want to manually set these environment variables during every deployment but would rather have them stored and used each time the application is deployed.

Setting environment variables in ZEIT Now

According to the documentation4, there are two ways to set environment variables for your ZEIT Now project. The first is to use the now command line tool with the -e option, such as:

now -e CLIENT_ID="abcdefg" -e CLIENT_SECRET="123456789abcdefg"

This approach not only sets the environment variables but also triggers a new deploy. The environment variables set here are valid only for the triggered deploy and will not automatically be available for any future deploys. You need to include the environment variables any time you deploy, which isn’t ideal when the information doesn’t need to change between deploys.

The second way to set environment variables is to include them in the now.json file. There are actually two keys that can contain environment variables in now.json:

env is used for environment variables needed only during application runtime.

build.env is used for environment variables needed only during the build process.

Whether you need the environment variables in one or both modes is up to how your application is built.

Be particularly careful if your build process uses the same JavaScript configuration file as your runtime, as you may find both the build and runtime will require the same environment variables even if it’s not immediately obvious (this happened to me). This is common with universal frameworks such as Next.js and Nuxt.js.

Both the env and build.env keys are objects where the property names are the environment variables to set and the property values are the environment variable values. For example, the following sets CLIENT_ID and CLIENT_SECRET in both the build and runtime environments:

{

"env": {

"CLIENT_ID": "abcdefg",

"CLIENT_SECRET": "123456789abcdefg"

},

"build": {

"env": {

"CLIENT_ID": "abcdefg",

"CLIENT_SECRET": "123456789abcdefg"

}

}

}

The environment variables in now.json are set for each deploy automatically, so this is the easiest way to persist important information for your application. Of course, if your environment variables contain sensitive information then you wouldn’t want to check now.json into your source code repository. That’s not a great solution because now.json contains more than just environment variables. The solution is to use now.json with project secrets.

Using ZEIT Now secrets

ZEIT Now has the ability to store secrets associated with each project. You can set a secret using the now CLI. You can name these secrets whatever you want, but the documentation4 suggests using lower dash case, Here’s an example:

now secret add client-id abcdefg

now secret add client-secret 123456890abcdefg

These commands create two secrets: client-id and client-secret. These are automatically synced to my ZEIT Now project and only available within that one project.

The next step is to reference these secrets inside of the now.json file. To specify that the value is a secret, prefix it with the @ symbol. For example, the following sets CLIENT_ID and CLIENT_SECRET in both the build and runtime environments:

{

"env": {

"CLIENT_ID": "@client-id",

"CLIENT_SECRET": "@client-secret"

},

"build": {

"env": {

"CLIENT_ID": "@client-id",

"CLIENT_SECRET": "@client-secret"

}

}

}

This now.json configuration specifies that the environment variables should be filled with secret values. Each time your application is deployed, ZEIT Now will read the client-id and client-secret secrets and expose them as the environment variables CLIENT_ID and CLIENT_SECRET. It’s now safe to check now.json into your source code repository because it’s not exposing any secure information. You can just use the now command to deploy your application knowing that all of the important environment variables will be added automatically.

Summary

The way ZEIT Now handles environment variables takes a little getting used to. Whereas other services allow you to specify secret environment variables directly in their web interface, ZEIT Now requires using the now command line tool to do so.

The easiest way to securely persist environment variables in your ZEIT Now project is to store the information in secrets and then specify the environment variables in your now.json file. Doing so allows you to check now.json into your source code repository without exposing sensitive information. Given the many configuration options available in now.json, it’s helpful to have that file in source control so you can make changes when necessary.

References

ZEIT Now - Environment Variables and Secrets ↩ ↩2

April 15, 2019

Outputting Markdown from Jekyll using hooks

One of the things I most enjoy about Jekyll1 is writing my blog posts in Markdown. I love not worrying about HTML and just letting Jekyll generate it for me when a post is published. Using Liquid tags directly in Markdown is also helpful, as I can define sitewide or page-specific variables and then replace them during site generation. This is a really useful capability that I wanted to take advantage of to output Markdown for use in other sites. Places like Medium and dev.to allow you to post Markdown articles, so I thought repurposing the Markdown I used in Jekyll would make crossposting to those sites easier.

I assumed that there would be a property on the page variable that would give me access to the rendered Markdown, but I was wrong. This began a long journey through relatively undocumented corners of the Jekyll plugin ecosystem. I’m sharing that journey here in the hopes that others won’t have to go through the same frustrating experience.

An introduction to Jekyll plugins

I was relatively unfamiliar with the Jekyll plugin system before trying to figure out how to get the rendered Markdown for a post. Jekyll supports a number of different plugin types2. These plugin types affect Jekyll directly:

Generators - plugins that create files. While it’s not required that generators create files, this is the most frequent use case. Plugins like jekyll-archives use generators to create files that wouldn’t otherwise exist.

Converters - plugins that convert between text formats. Jekyll’s default of converting Markdown files into HTML is implemented using a converter. You can add support for other formats to be converted into HTML (or any other format) by creating your own converter.

Hooks - plugins that listen for specific events in Jekyll and then perform some action in relation to the events.

There are also two plugin types that are used primarily with Liquid:

Tags - create a new tag in the format {% tagname %} for use in your templates.

Filters - create a new filter that you can use to transform input, such as {{ data | filter }}

There is also a command plugin type that allows you to create new commands to use with the jekyll command line tool. The jekyll build command is implemented using this plugin type.

Designing the solution

My goal was to get the Liquid-rendered Markdown content (so all data processing was complete) for each post into a page property so that I could output that content into a JSON file on my server. That JSON file would then be fetched by an AWS Lambda function that crossposted that content to other locations. I didn’t need to generate any extra files or convert from one format to another, so it seemed clear that using a hook would be the best approach.

Hooks are basically event handlers in which you specify a container and the event to listen to. Jekyll passes you the relevant information for that event and you can then perform any action you’d like. There are four containers you can use with hooks:

:site - the site object

:page - the page object for each non-collection page

:post - the post object for each blog post

:document - the document object for each document in each collection (including blog posts and custom collections)

Because I wanted this solution to work for all collections in my site, I chose to use :document as an easy way to make the same change for all collection types.

There were two events for :document that immediately seemed relevant to my goal:

:pre_render - fires before the document content is rendered

:post_render - fires after the document content is rendered but before the content is written to disk

It seemed clear that getting the Markdown content would require using the :pre_render event, so I started by using this setup:

Jekyll::Hooks.register :documents, :pre_render do |doc, payload|

# code goes here

end

Each hook is passed its target container object, in this case doc is a document, and a payload object containing all of the relevant variables for working with the document (these are the variables available inside of a template when the document is rendered).

The :document, :prerender hook is called just before each document is rendered, meaning you don’t need to worry about looping over collections manually.

The catch: Rendering doesn’t mean what you think it means

I figured that the content property inside of a :document, :pre_render hook would contain the Liquid-rendered Markdown instead of the final HTML, but I was only half correct. The content property actually contains the unprocessed Markdown that still contains all of the Liquid variables. It turns out that “prerender” means something different than I thought.

The lifecycle of the content property for a given document in Jekyll looks like this3:

The content property contains the file content with the front matter removed (typically Markdown)

:pre_render hook fires

The content property is rewritten with Liquid tags rendered (this is what Jekyll internally refers to as rendering)

The content property is rewritten after being passed through a converter (this is what Jekyll internally refers to as converting)

The :post_render hook fires

While Jekyll internally separates rendering (which is apply Liquid) and converting (the Markdown to HTML conversion, for example), the exposed hooks don’t make this distinction. That means if I want Markdown content with Liquid variables replaced then I’ll need to get the prerendered Markdown content and render it myself.

The solution

At this point, my plan was to create a pre_render hook that did the following:

Retrieved the raw content for each document (contained in doc.content)

Render that content using Liquid

Store the result in a new property called unconverted_content that would be accessible inside my templates

I started out with this basic idea of how things should look:

Jekyll::Hooks.register :documents, :pre_render do |doc, payload|

# get the raw content

raw_content = doc.content

# do something to that raw content

rendered_content = doSomethingTo(raw_content)

# store it back on the document

doc.rendered_content = rendered_content

end

Of course, I’m not very familiar with Ruby, so it turned out this wouldn’t work quite the way I thought.

First, doc is an instance of a class, and you cannot arbitrarily add new properties to objects in Ruby. Jekyll provides a data hash on the document object, however, that can be used to add new properties that are available in templates. So the last line needs to be rewritten:

Jekyll::Hooks.register :documents, :pre_render do |doc, payload|

# get the raw content

raw_content = doc.content

# do something to that raw content

rendered_content = doSomethingTo(raw_content)

# store it back on the document

doc.data['rendered_content'] = rendered_content

end

The last line ensures that page.rendered_content will be available inside of templates later on (and remember, this is happening during pre_render, so the templates haven’t yet been used).

The next step was to use Liquid to render the raw content. To figure out how to do this, I had to dig around in the Jekyll source4 as there wasn’t any documentation. Rendering Liquid the exact same way that Jekyll does by default requires a bit of setup and pulling in pieces of data from a couple different places. Here is the final code:

Jekyll::Hooks.register :documents, :pre_render do |doc, payload|

# make some local variables for convenience

site = doc.site

liquid_options = site.config["liquid"]

# create a template object

template = site.liquid_renderer.file(doc.path).parse(doc.content)

# the render method expects this information

info = {

:registers => { :site => site, :page => payload['page'] },

:strict_filters => liquid_options["strict_filters"],

:strict_variables => liquid_options["strict_variables"],

}

# render the content into a new property

doc.data['rendered_content'] = template.render!(payload, info)

end

The first step in this hook is to create a Liquid template object. While you can do this directly using Liquid::Template, Jekyll caches Liquid templates internally when using site.liquid_renderer.file(doc.path), so it makes sense to use that keep the Jekyll build as fast as possible. The content is then parsed into a template object.

The template.render() method needs not only the payload object but also some additional information. The info hash passes in registers, which are local variables accessible inside of the template, and some options for how liquid should behave. With all of that data ready, the content is rendered into the new property.

This file then needs to be placed in the _plugins directory of a Jekyll site to run each time the site is built.

Accessing rendered_content

With this plugin installed, the Markdown content is available through the rendered_content property, like this:

{{ page.rendered_content }}

The only problem is that outputting page.rendered_content into a Markdown page will cause all of that Markdown to be converted into HTML. (Remember, Jekyll internally renders Liquid first and then the result is converted into HTML.) So in order to output the raw Markdown, you’ll need to either apply a filter that prevents the Markdown-to-HTML conversion from happening, or use a file type that doesn’t convert automatically.

In my case, I’m storing the Markdown content in a JSON structure, so I’m using the jsonify filter, like this:

---

layout: null

---

{

{% assign post = site.posts.first %}

"id": "{{ post.url | absolute_url | sha1 }}",

"title": {{ post.title | jsonify }},

"date_published": "{{ post.date | date_to_xmlschema }}",

"date_published_pretty": "{{ post.date | date: "%B %-d, %Y" }}",

"summary": {{ post.excerpt | strip_html | strip_newlines | jsonify }},

"content_markdown": {{ post.rendered_content | jsonify }},

"content_html": {{ post.content | jsonify }},

"tags": {{ post.tags | jsonify }},

"url": "{{ post.url | absolute_url }}"

}

Another option is to create a rendered_content.txt file in the _includes directory that just contains this:

{{ page.rendered_content }}

Then, you can include that file anywhere you want the unconverted Markdown content, like this:

{% include "rendered_content.txt" %}

Conclusion

Jekyll hooks are a useful feature that let you interact with Jekyll while it is generating your site, allowing you to intercept, modify, and add data along the way. While there aren’t a lot of examples in the wild, the concept is straightforward enough that with a few pointers, any programmer should be able to get something working. The biggest stumbling point for me was the lack of documentation on how to use Jekyll hooks, so I’m hoping that this writeup will help others who are trying to accomplish similar tasks in their Jekyll sites.

To date, I’ve found Jekyll to be extremely versatile and customizable. Being able to get the Liquid-rendered Markdown (even though it took a bit of work) has made my publishing workflow much more flexible, as I’m now more easily able to crosspost my writing on various other sites.

References

Jekyll Order of Interpretation ↩

March 4, 2019

Computer science in JavaScript: Circular Doubly-linked lists

In my previous post, I discussed what changes are necessary to turn a singly linked list into a doubly linked list. I recommend reading that post before this one (if you haven’t already). This post is about modifying a doubly linked list (also called a linear doubly linked list) in such a way that the last node in the list points to the first node in the list, effectively making the list circular. Circular doubly linked lists are interesting because they allow you to continuously move through list items without needing to check for the end of the list. You may encounter this when creating playlists or round-robin distribution of traffic to servers.

It is possible to create a circular singly linked list, as well. I won’t be covering circular singly linked lists in this blog post series, however, you can find source code for a circular singly linked list in my GitHub repo, Computer Science in JavaScript.

The design of a circular doubly linked list

The nodes in a circular doubly linked list are no different than the nodes for a linear doubly linked list. Each node contains data and pointers to the next and previous items in the list. Here is what that looks like in JavaScript:

class CircularDoublyLinkedListNode {

constructor(data) {

this.data = data;

this.next = null;

this.previous = null;

}

}

You can then create a circular doubly linked list using the CircularDoublyLinkedListNode class like this:

// create the first node

const head = new CircularDoublyLinkedListNode(12);

// add a second node

const secondNode = new CircularDoublyLinkedListNode(99);

head.next = secondNode;

secondNode.previous = head;

// add a third node

const thirdNode = new CircularDoublyLinkedListNode(37);

secondNode.next = thirdNode;

thirdNode.previous = secondNode;

// point the last node to the first

thirdNode.next = head;

head.previous = thirdNode;

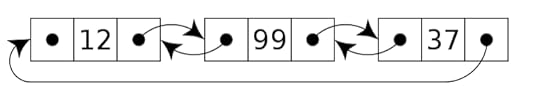

The head of the list and subsequent nodes in the list are created the same way as in a linear doubly linked list. The only difference is the last step where the last node’s next pointer is set to head and the head node’s previous pointer is set to the last node. The following image shows the resulting data structure.

Traversing a circular doubly linked list is a bit different than a linear doubly linked list because following next pointers alone will result in an infinite loop. For example, this is an infinite loop:

let current = head;

// infinite loop: `current` is never `null`

while (current !== null) {

console.log(current.data);

current = current.next;

}

In some cases you will want to continue iterating over the loop forever, but that typically does not happen in the context of a loop as in this code. In other cases, you’ll want to iterate over each node in the loop until the last node is found. To do that, you’ll need to check to see when current is head, which means you’re back at the beginning of the loop. However, simply swapping null for head in the previous example results in the loop not executing at all:

let current = head;

// loop is skipped: `current` is already `head`

while (current !== head) {

console.log(current.data);

current = current.next;

}

The problem here is that current started out equal to head and the loop only proceeds when current is not equal to head. The solution is to use a post-test loop instead of a pre-test loop, and in JavaScript, that means using a do-while loop:

let current = head;

if (current !== null) {

do {

console.log(current.data);

current = current.next;

} while (current !== head);

}

In this code, the check to see if current is equal to head appears at the end of the loop rather than at the start. To ensure that the loop won’t start unless current isn’t null, an if statement typically must preceed the do-while loop (you no longer have the pre-test of a while loop to cover that case for you). The loop will proceed until current is once again head, meaning that the entire list has been traversed.

Also similar to linear doubly linked lists, you can traverse the nodes in reverse order by starting from the last node. Circular doubly linked lists don’t separately track the list tail because you can always access the tail through head.previous, for example:

let current = head.previous;

if (current !== null) {

do {

console.log(current.data);

current = current.previous;

} while (current !== head.previous);

}

The CircularDoublyLinkedList class

The CircularDoublyLinkedList class starts out looking a lot like the DoublyLinkedList class from the previous article with the exception that there is no tail property to track the last node in the list:

const head = Symbol("head");

class CircularDoublyLinkedList {

constructor() {

this[head] = null;

}

}

The primary differences between a linear and circular doubly linked list have to do with the methods for adding, removing, and traversing the nodes.

Adding new data to the list

The same basic algorithm for adding data is used for both linear and circular doubly linked lists, with the difference being the pointers that must be updated to complete the process. Here is the add() method for the CircularDoublyLinkedList class:

class CircularDoublyLinkedList {

constructor() {

this[head] = null;

}

add(data) {

const newNode = new CircularDoublyLinkedListNode(data);

// special case: no items in the list yet

if (this[head] === null) {

this[head] = newNode;

newNode.next = newNode;

newNode.previous = newNode;

} else {

const tail = this[head].previous;

tail.next = newNode;

newNode.previous = tail;

newNode.next = this[head];

this[head].previous = newNode;

}

}

}

The add() method for the circular doubly linked list accepts one argument, the data to insert into the list. If the list is empty (this[head] is null) then the new node is assigned to this[head]. The extra step to make the list circular is to ensure that both newNode.next and newNode.previous point to newNode.

If the list is not empty, then a new node is added after the current tail, which is retrieved using this[head].previous. The new node can then be added to tail.next. Remember, you are actually inserting a new node between the tail and the head of the list, so this operation looks a lot more like an insert than an append. Once complete, newNode is the list tail and therefore newNode.next must point to this[head] and this[head].previous must point to newNode.

As with a linear doubly linked list, the complexity of this add() method is O(1) because no traversal is necessary.

Retrieving data from the list

The get() method for a circular doubly linked list follows the basic algorithm from the start of this post. You must traverse the list while keeping track of how deep into the list you have gone and ensuring you don’t loop back around to the front of the list. Here is how the get() method is implemented.

class CircularDoublyLinkedList {

// other methods hidden for clarity

get(index) {

// ensure `index` is a positive value and the list isn't empty

if ((index > -1) && (this[head] !== null)) {

let current = this[head];

let i = 0;

do {

if (i === index) {

return current.data;

}

current = current.next;

i++;

} while ((current !== this[head]) && (i index));

}

return undefined;

}

}

The get() method first checks to make sure that index is a positive value and that the list isn’t empty. If either case is true, then the method returns undefined. Remember, you must always use an if statement to check if a circular doubly linked list is empty before starting a traversal due to the use of a post-test instead of a pre-test loop.

Using the same traversal algorithm as discussed earlier, the get() method uses the i variable to track how deep into the list it has traversed. When i is equal to index, the data in that node is returned (existing the loop early). If the loop exits, either because it has reached the head of the list again or index is not found in the list, then undefined is returned.

As with a linear doubly linked list, the get() method’s complexity ranges from O(1) to O(n);

Removing data from the list

Removing data from a circular doubly linked list is basically the same as with a linear doubly linked list. The differences are:

Using a post-test loop instead of a pre-test loop for the traversal (same as get())

Ensuring that the circular links remain on the head and tail nodes when either is removed

Here is what the implementation of a remove() method looks like:

class CircularDoublyLinkedList {

// other methods hidden for clarity

remove(index) {

// special cases: no nodes in the list or `index` is an invalid value

if ((this[head] === null) || (index < 0)) {

throw new RangeError(`Index ${index} does not exist in the list.`);

}

// save the current head for easier access

let current = this[head];

// special case: removing the first node

if (index === 0) {

// if there's only one node, null out `this[head]`

if (current.next === this[head]) {

this[head] = null;

} else {

// get the last item in the list

const tail = this[head].previous;

/*

* Set the tail to point to the second item in the list.

* Then make sure that item also points back to the tail.

*/

tail.next = current.next;

current.next.previous = tail;

// now it's safe to update the head

this[head] = tail.next;

}

// return the data at the previous head of the list

return current.data;

}

let i = 0;

do {

// traverse to the next node

current = current.next;

// increment the count

i++;

} while ((current !== this[head]) && (i < index));

// the node to remove has been found

if (current !== this[head]) {

// skip over the node to remove

current.previous.next = current.next;

current.next.previous = current.previous;

// return the value that was just removed from the list

return current.data;

}

// `index` doesn't exist in the list so throw an error

throw new RangeError(`Index ${index} does not exist in the list.`);

}

}

While there are special cases in this remove() method, almost every case requires adjusting pointers on two nodes due to the circular nature of the list. The only case where this isn’t necessary is when you are removing the only node in the list.

Removing the first node in the list (index is 0) is treated as a special case because there is no need for traversal and this[head] must be assigned a new value. The second node in the list becomes the head and it previous pointer must be adjusted accordingly.

The rest of the method follows the same algorithm as for a linear doubly linked list. As we don’t need to worry about the special this[head] pointer, the search for and removal of the node at index can proceed as if the list was linear.

You can further simply removal of nodes if you don’t mind losing track of the original head of the list. The implementation of CircularDoublyLinkedList in this post assumes you want the original head of the list to remain as such unless it is removed. However, because the list is circular, it really doesn’t matter what nodes is considered the head because you can always get to every other node as long as you reference to one node. You can arbitrarily reset this[head] to any node you want an all of the functionality will continue to work.

Creating iterators

There are two distinct use cases for iterators in a circular linked list:

For use with JavaScript’s builtin iteration functionality (like for-of loops)

For moving through the values of the list in a circular fashion for specific applications (like a playlist)

To address the first case, it makes sense to create a values() generator method and a Symbol.iterator method on the class as these are expected on JavaScript collections. These methods are similar to those in a doubly linked list with the usual exceptions that the loop must be flipped and the you need to check to see if you’ve reached the list head to exit the loop. Those two methods look like this:

class CircularLinkedList {

// other methods hidden for clarity

values() {

// special case: list is empty

if (this[head] !== null) {

// special case: only one node

if (this[head].next === this[head]) {

yield this[head].data;

} else {

let current = this[head];

do {

yield current.data;

current = current.next;

} while (current !== this[head]);

}

}

}

[Symbol.iterator]() {

return this.values();

}

}

The values() generator method has two special cases: when the list is empty, in which case it doesn’t yield anything, and when there is only one node, in which case traversal isn’t necessary and the data stored in the head is yielded. Otherwise, the do-while loop is the same as the one you’ve seen through this post.

Creating an iterator that loops around is then just a matter of modifying this algorithm so the loop never exits. Here is what that looks like:

class CircularDoublyLinkedList {

// other methods hidden for clarity

*circularValues() {

// special case: list is empty

if (this[head] !== null) {

let current = this[head];

// infinite loop

do {

yield current.data;

current = current.next;

} while (true);

}

}

}

You wouldn’t want to use the circularValues() generator method in any situation where JavaScript will drain an iterator (as in the for-of loop) because this will cause an infinite loop and crash. Instead, manually call the next() method of the iterator whenever you need another value.

For this method, it really doesn’t matter if you use a do-while loop or a while loop. I used do-while to keep it consistent with the rest of this post, but you can use any flavor of infinite loop that you want.

Using the class

Once complete, you can use the circular doubly linked list implementation like this:

const list = new CircularDoublyLinkedList();

list.add("red");

list.add("orange");

list.add("yellow");

// get the second item in the list

console.log(list.get(1)); // "orange"

// print out all items

for (const color of list.values()) {

console.log(color);

}

// remove the second item in the list

console.log(list.remove(1)); // "orange"

// get the new first item in the list

console.log(list.get(1)); // "yellow"

// convert to an array

const array1 = [...list.values()];

const array2 = [...list];

// manually cycle through each item in a circular manner

const iterator = list.circularValues();

let { value } = iterator.next();

doSomething(value);

({ value } = iterator.next());

doSomething(value);

The full source code is available on GitHub at my Computer Science in JavaScript project.

Conclusion

Circular doubly linked lists are setup in a similar manner as linear doubly linked lists in that each ndoe has a pointer to both the next and previous nodes in the list. The difference is that the list tail always points to the list head so you can follow next pointers and never receive null. This functionality can be used for applications such as playlists or round-robin distribution of data processing.

The implementation of doubly linked list operations differs from linear doubly linked lists in that you must use a post-test loop (do-while) to check if you’re back at the beginning of the list. For most operations, it’s important to stop when the list head has been reached again. The only exception is in creating an iterator to be called manually and which you’d prefer never ran out of items to return.

The complexity of circular doubly linked list operations is the same as with linear doubly linked list operations. Unlike the other data structures discussed in this blog post series, circular doubly linked lists can be helpful in JavaScript applications that require repeating cycling through the same data. That is one use case that isn’t covered well by JavaScript’s builtin collection types.

February 4, 2019

Computer science in JavaScript: Doubly linked lists

In my previous post, I discussed creating a singly linked list in JavaScript (if you haven’t yet read that post, I suggest doing so now). A single linked list consists of nodes that each have a single pointer to the next node in the list. Singly linked lists often require traversal of the entire list for operations, and as such, have generally poor performance. One way to improve the performance of linked lists is to add a second pointer on each node that points to the previous node in the list. A linked list whose nodes point to both the previous and next nodes is called a doubly linked list.

The design of a doubly linked list

Similar to a singly linked list, a doubly linked list is made up of a series of nodes. Each node contains some data as well as a pointer to the next node in the list and a pointer to the previous node. Here is a simple representation in JavaScript:

class DoublyLinkedListNode {

constructor(data) {

this.data = data;

this.next = null;

this.previous = null;

}

}

In the DoublyLinkedListNode class, the data property contains the value the linked list item should store, the next property is a pointer to the next item in the list, and the previous property is a pointer to the previous item in the list. Both the next and previous pointers start out as null because the next and previous nodes aren’t known at the time the class is instantiated. You can then create a doubly linked list using the DoublyLinkedListNode class like this:

// create the first node

const head = new DoublyLinkedListNode(12);

// add a second node

const secondNode = new DoublyLinkedListNode(99);

head.next = secondNode;

secondNode.previous = head;

// add a third node

const thirdNode = new DoublyLinkedListNode(37);

secondNode.next = thirdNode;

thirdNode.previous = secondNode;

const tail = thirdNode;

As with a singly linked list, the first node in a doubly linked list is called the head. The second and third nodes are assigned by using both the next and previous pointers on each node. The following image shows the resulting data structure.

You can traverse a doubly linked list in the same way as a singly linked list by following the next pointer on each node, such as:

let current = head;

while (current !== null) {

console.log(current.data);

current = current.next;

}

Doubly linked list also typically track the last node in the list, called the tail. The tail of the list is useful to track both for easier insertion of new nodes and to search from the back of the list to the front. To do so, you start at the tail and follow the previous links until there are no more nodes. The following code prints out each value in the doubly linked in reverse:

let current = tail;

while (current !== null) {

console.log(current.data);

current = current.previous;

}

This ability to go backwards and forwards through a doubly linked list provides an advantage over a singly linked list by allowing searches in both directions.

The DoublyLinkedList class

As with a singly linked list, the operations for manipulating nodes in a doubly linked list are best encapsulated in a class. Here is a simple example:

const head = Symbol("head");

const tail = Symbol("tail");

class DoublyLinkedList {

constructor() {

this[head] = null;

this[tail] = null;

}

}

The DoublyLinkedList class represents a doubly linked list and will contain methods for interacting with the data it contains. There are two symbol properties, head and tail, to track the first and last nodes in the list, respectively. As with the singly linked list, the head and tail are not intended to be accessed from outside the class.

Adding new data to the list

Adding an item to a doubly linked list is very similar to adding to a singly linked list. In both data structures, you must first find the last node in the list and then add a new node after it. In a singly linked list you had to traverse the entire list to find the last node whereas in a doubly linked list the last node is tracked using the this[tail] property. Here is the add() method for the DoublyLinkedList class:

class DoublyLinkedList {

constructor() {

this[head] = null;

this[tail] = null;

}

add(data) {

// create the new node and place the data in it

const newNode = new DoublyLinkedListNode(data);

// special case: no nodes in the list yet

if (this[head] === null) {

this[head] = newNode;

} else {

// link the current tail and new tail

this[tail].next = newNode;

newNode.previous = this[tail];

}

// reassign the tail to be the new node

this[tail] = newNode;

}

}

The add() method for the doubly linked list accepts one argument, the data to insert into the list. If the list is empty (both this[head] and this[tail] are null) then the new node is assigned to this[head]. If the list is not empty, then a new node is added after the current this[tail] node. The last step is to set this[tail] to be newNode because in both an empty and non-empty list the new node will always be the last node.

Notice that in the case of an empty list, this[head] and this[tail] are set to the same node. That’s because the single node in a one-node list is both the first and the last node in that list. Keeping proper track of the list tail is important so the list can be traversed in reverse if necessary.

The complexity of this add() method is O(1). For both an empty and a non-empty list, the operation doesn’t require any traversal and so is much less complex than add() for the singly linked list where only the list head was tracked.

Retrieving data from the list

The get() method for a doubly linked list is exactly the same as the get() method for a singly linked list. In both cases, you must traverse the list starting from this[head] and track how many nodes have been seen to determine when the correct node is reached:

class DoublyLinkedList {

// other methods hidden for clarity

get(index) {

// ensure `index` is a positive value

if (index > -1) {

// the pointer to use for traversal

let current = this[head];

// used to keep track of where in the list you are

let i = 0;

// traverse the list until you reach either the end or the index

while ((current !== null) && (i < index)) {

current = current.next;

i++;

}

// return the data if `current` isn't null

return current !== null ? current.data : undefined;

} else {

return undefined;

}

}

}

To reiterate from the singly linked list post, the complexity of the get() method ranges from O(1) when removing the first node (no traversal is needed) to O(n) when removing the last node (traversing the entire list is required).

Removing data from a doubly linked list

The algorithm for removing data from a doubly linked list is essentially the same as with a singly linked list: first traverse the data structure to find the node in the given position (same algorithm as get()) and then remove it from the list. The only significant differences from the algorithm used in a singly linked list are:

There is no need for a previous variable to track one node back in the loop because the previous node is always available through current.previous.

You need to watch for changes to the last node in the list to ensure that this[tail] remains correct.

Otherwise, the remove() method looks very similar to that of the singly linked list:

class DoublyLinkedList {

// other methods hidden for clarity

remove(index) {

// special cases: no nodes in the list or `index` is negative

if ((this[head] === null) || (index < 0)) {

throw new RangeError(`Index ${index} does not exist in the list.`);

}

// special case: removing the first node

if (index === 0) {

// store the data from the current head

const data = this[head].data;

// just replace the head with the next node in the list

this[head] = this[head].next;

// special case: there was only one node, so also reset `this[tail]`

if (this[head] === null) {

this[tail] = null;

} else {

this[head].previous = null;

}

// return the data at the previous head of the list

return data;

}

// pointer use to traverse the list

let current = this[head];

// used to track how deep into the list you are

let i = 0;

// same loop as in `get()`

while ((current !== null) && (i < index)) {

// traverse to the next node

current = current.next;

// increment the count

i++;

}

// if node was found, remove it

if (current !== null) {

// skip over the node to remove

current.previous.next = current.next;

// special case: this is the last node so reset `this[tail]`.

if (this[tail] === current) {

this[tail] = current.previous;

} else {

current.next.previous = current.previous;

}

// return the value that was just removed from the list

return current.data;

}

// if node wasn't found, throw an error

throw new RangeError(`Index ${index} does not exist in the list.`);

}

}

When index is 0, meaning the first node is being removed, this[head] is set to this[head].next, the same as with a singly linked list. The difference comes after that point when you need to update other pointers. If there was only one node in the list, then you need to set this[tail] to null to effectively remove that one node; if there was more than one node, you need to set this[head].previous to null. Remember that the new head was previously the second node in the list and so its previous link was pointing to the node that was just removed.

After the loop, you need to ensure that both the next pointer of the node before the removed node and the previous pointer of the node after the removed node. Of course, if the node to remove is the last node then you need to update the this[tail] pointer.

Creating a reverse iterator

You can make a doubly linked list iterable in JavaScript using the same values() and Symbol.iterator methods from the singly linked list. In a doubly linked list, however, you have the opportunity to create a reverse iterator that produces the data starting from the tail and working its way towards the head. Here is what a reverse() generator method looks like:

class DoublyLinkedList {

// other methods hidden for clarity

*reverse(){

// start by looking at the tail

let current = this[tail];

// follow the previous links to the head

while (current !== null) {

yield current.data;

current = current.previous;

}

}

}

The reverse() generator method follows the same algorithm as the values() generator method in the singly linked list with the exception that current starts equal to this[tail] and the current.previous is followed until the there are no more nodes. Creating a reverse iterator is helpful for discovering bugs in the implementation as well as avoiding rearranging nodes just to access the data in a different order.

Other methods

Most other methods that don’t involve addition or removal of nodes follow the same algorithms as those in a singly linked list.

Using the class

Once complete, you can use the linked list implementation like this:

const list = new DoublyLinkedList();

list.add("red");

list.add("orange");

list.add("yellow");

// get the second item in the list

console.log(list.get(1)); // "orange"

// print out all items in reverse

for (const color of list.reverse()) {

console.log(color);

}

// remove the second item in the list

console.log(list.remove(1)); // "orange"

// get the new first item in the list

console.log(list.get(1)); // "yellow"

// convert to an array

const array1 = [...list.values()];

const array2 = [...list];

const array3 = [...list.reverse()];

The full source code is available on GitHub at my Computer Science in JavaScript project.

Conclusion

Doubly linked lists are similar to singly linked lists in that each node has a next pointer to the next node in the list. Each node also has a previous pointer to the previous node in the list, allowing you to move both backwards and forwards in the list easily. Doubly linked lists typically track both the first and last node in the list, and that makes adding a node into the list a O(1) operation instead of O(n) in a singly linked list.

However, the complexity of other doubly linked list operations is the same as with a singly linked list because you always end up traversing most of the list. As such, doubly linked lists don’t offer any real advantage over the built-in JavaScript Array class for storing a collection of unrelated data (though related data, such as sibling DOM nodes in the browser) might be useful to represent in some kind of linked list.

January 14, 2019

Why I've stopped exporting defaults from my JavaScript modules

Last week, I tweeted something that got quite a few surprising responses:

In 2019, one of the things I’m going to do is stop exporting things as default from my CommonJS/ES6 modules.

Importing a default export has grown to feel like a guessing game where I have a 50/50 chance of being wrong each time. Is it a class? Is it a function?

— Nicholas C. Zakas (@slicknet) January 12, 2019

I tweeted this after realizing that a lot of problems I had with JavaScript modules could be traced back to fights with default exports. It didn’t matter if I was using JavaScript modules (or ECMAScript modules, as many prefer to call them) or CommonJS, I was still stumbling over importing from modules with default exports. I got a variety of responses to the tweet, many of which questioned how I could come to this decision. This post is my attempt to clarify my thinking.

A few clarifications

As is the case with all tweets, my tweet was meant as a snapshot into an opinion I had rather than a normative reference for my entire opinion. To clarify a few points people seem confused by on Twitter:

The use case of knowing whether an export is a function or a class was an example of the type of problems I’ve encountered. It is not the only problem I’ve found named exports solve for me.

The problems I’ve encountered don’t just happen with files in my own projects, they also happen with importing library and utility modules that I don’t own. That means naming conventions for filenames don’t solve all of the problems.

I’m not saying that everyone should abandon default exports. I’m saying that in modules I’m writing, I will choose not to use default exports. You may feel differently, and that’s fine.

Hopefully those clarifications setup enough context to avoid confusion throughout the rest of this post.

Default exports: A primer

To the best of my knowledge, default exports from modules were first popularized in CommonJS, where a module can export a default value like this:

class LinkedList {}

module.exports = LinkedList;

This code exports the LinkedList class but does not specify the name to be used by consumers of the module. Assuming the filename is linked-list.js, you can import that default in another CommonJS module like this:

const LinkedList = require("./linked-list");

The require() function is returning a value that I just happened to name LinkedList to match what is in linked-list.js, but I also could have chosen to name it foo or Mountain or any random identifier.

The popularity of default module exports in CommonJS meant that JavaScript modules were designed to support this pattern:

ES6 favors the single/default export style, and gives the sweetest syntax to importing the default.

— David Herman June 19, 2014

So in JavaScript modules, you can export a default like this:

export default class LinkedList {}

And then you can import like this:

import LinkedList from "./linked-list.js";

Once again, LinkedList is this context is an arbitrary (if not well-reasoned) choice and could just as well be Dog or symphony.

The alternative: named exports

Both CommonJS and JavaScript modules support named exports in addition to default exports. Named exports allow for the name of a function, class, or variable to be transferred into the consuming file.

In CommonJS, you create a named export by attaching a name to the exports object, such as:

exports.LinkedList = class LinkedList {};

You can then import in another file like this:

const LinkedList = require("./linked-list").LinkedList;

Once again, the name I’ve used with const can be anything I want, but I’ve chosen to match it to the exported name LinkedList.

In JavaScript modules, a named export looks like this:

export class LinkedList {}

And you can import like this:

import { LinkedList } from "./linked-list.js";

In this code, LinkedList cannot be a randomly assigned identifier and must match an named export called LinkedList. That’s the only significant difference from CommonJS for the goals of this post.

So the capabilities of both module types support both default and named exports.

Personal preferences

Before going further, it’s helpful for you to know some of my own personal preferences when it comes to writing code. These are general principles I apply to all code that I write, regardless of the programming language I use:

Explicit over implicit. I don’t like having code with secrets. What something does, what something should be called, etc., should always be made explicit whenever possible.

Names should be consistent throughout all files. If something is an Apple in one file, I shouldn’t call it Orange in another file. An Apple should always be an Apple.

Throw errors early and often. If it’s possible for something to be missing then it’s best to check as early as possible and, in the best case, throw an error that alerts me to the problem. I don’t want to wait until the code has finished executing to discover that it didn’t work correctly and then hunt for the problem.

Fewer decisions mean faster development. A lot of the preferences I have are for eliminating decisions during coding. Every decision you make slows you down, which is why things like coding conventions lead to faster development. I want to decide things up front and then just go.

Side trips slow down development. Whenever you have to stop and look something up in the middle of coding, I call that a side trip. Side trips are sometimes necessary but there are a lot of unnecessary side trips that can slow things down. I try to write code that eliminates the need for side trips.

Cognitive overhead slows down development. Put simply: the more detail you need to remember to be productive when writing code, the slower your development will be.

The focus on speed of development is a practical one for me. As I’ve struggled with my health for years, the amount of energy I’ve had to code continued to decrease. Anything I could do to reduce the amount of time spent coding while still accomplishing my task was key.

The problems I’ve run into

With all of this in mind, here are the top problems I’ve run into using default exports and why I believe that named exports are a better choice in most situations.

What is that thing?

As I mentioned in my original tweet, I find it difficult to figure out what I’m importing when a module only has a default import. If you’re using a module or file you’re unfamiliar with, it can be difficult to figure out what is returned, for example:

const list = require("./list");

In this context, what would you expect list to be? It’s unlikely to be a primitive value, but it could logically be a function, class, or other type of object. How will I know for sure? I need a side trip. In this case, a side trip might be any of:

If I own list.js, then I may open the file and look for the export.

If I don’t own list.js, then I may open up some documentation.

In either case, this now becomes an extra bit of information you need in your brain to avoid a second side trip penalty when you need to import from list.js again. If you are importing a lot of defaults from modules then either your cognitive overhead is increasing or the number of side trips is increasing. Both are suboptimal and can be frustrating.

Some will say that IDEs are the answer to this problem, that the IDEs should be smart enough to figure out what is being imported and tell you. While I’m all for smarter IDEs to help developers, I believe requiring IDEs to effectively use a language feature is problematic.

Name matching problems

Named exports require consuming modules to at least specify the name of the thing they are importing from a module. The benefit is that I can easily search for everywhere that LinkedList is used in a code base and know that it all refers to the same LinkedList. As default exports are not prescriptive of the names used to import them, that means naming imports becomes more cognitive overhead for each developer. You need to determine the correct naming convention, and as extra overhead, you need to make sure every developer working in the application will use the same name for the same thing. (You can, of course, allow each developer to use different names for the same thing, but that introduces more cognitive overhead for the team.)

Importing a named export means at least referencing the canonical name of a thing everywhere that it’s used. Even if you choose to rename an import, the decision is made explicit, and cannot be done without first referencing the canonical name in some way. In CommonJS:

const MyList = require("./list").LinkedList;

In JavaScript modules:

import { LinkedList as MyList } from "./list.js";

In both module formats, you’ve made an explicit statement that LinkedList is now going to be referred to as MyList.

When naming is consistent across a codebase, you’re able to easily do things like:

Search the codebase to find usage information.

Refactor the name of something across the entire codebase.

Is it possible to do this when using default exports and ad-hoc naming of things? My guess is yes, but I’d also guess that it would be a lot more complicated and error-prone.

Importing the wrong thing

Named exports in JavaScript modules have a particular advantage over default exports in that an error is thrown when attempting to import something that doesn’t exist in the module. Consider this code:

import { LinkedList } from "./list.js";

If LinkedList doesn’t exist in list.js, then an error is thrown. Further, tools such as IDEs and ESLint1 are easily able to detect a missing reference before the code is executed.

Worse tooling support

Speaking of IDEs, WebStorm is able to help write import statements for you.2 When you have finished typing an identifier that isn’t defined in the file, WebStorm will search the modules in your project to determine if the identifier is a named export in another file. At that point, it can do any of the following:

Underline the identifier that is missing its definition and show you the import statement that would fix it.

Automatically add the correct import statement (if you have enable auto import)

can now automatically add an import statement based on an identifier that you type. In fact, WebStorm is able to help you a great deal when using named imports:

There is a plugin for Visual Studio Code3 that provides similar functionality. This type of functionality isn’t possible when using default exports because there is no canonical name for things you want to import.

Conclusion

I’ve had several productivity problems importing default exports in my projects. While none of the problems are necessarily impossible to overcome, using named imports and exports seems to better fit my preferences when coding. Making things explicit and leaning heavily on tooling makes me a productive coder, and insofar as named exports help me do that, I will likely favor them for the foreseeable future. Of course, I have no control over how third-party modules I use export their functionality, but I definitely have a choice over how my own modules export things and will choose named exports.

As earlier, I remind you that this is my opinion and you may not find my reasoning to be persuasive. This post was not meant to persuade anyone to stop using default exports, but rather, to better explain to those that inquired why I, personally, will stop exporting defaults from the modules I write.

References

WebStorm: Auto Import in JavaScript ↩

January 7, 2019

Computer science in JavaScript: Linked list

Back in 2009, I challenged myself to write one blog post per week for the entire year. I had read that the best way to gain more traffic to a blog was to post consistently. One post per week seemed like a realistic goal due to all the article ideas I had but it turned out I was well short of 52 ideas. I dug through some half-written chapters what would eventually become Professional JavaScript and found a lot of material on classic computer science topics, including data structures and algorithms. I took that material and turned it into several posts in 2009 and (and a few in 2012), and got a lot of positive feedback on them.

Now, at the ten year anniversary of those posts, I’ve decided to update, republish, and expand on them using JavaScript in 2019. It’s been interesting to see what has changed and what hasn’t, and I hope you enjoy them.

What is a linked list?

A linked list is a data structure that stores multiple values in a linear fashion. Each value in a linked list is contained in its own node, an object that contains the data along with a link to the next node in the list. The link is a pointer to another node object or null if there is no next node. If each node has just one pointer to another node (most frequently called next) then the list is considered a singly linked list (or just linked list) whereas if each node has two links (usually previous and next) then it is considered a doubly linked list. In this post, I am focusing on singly linked lists.

Why use a linked list?

The primary benefit of linked lists is that they can contain an arbitrary number of values while using only the amount of memory necessary for those values. Preserving memory was very important on older computers where memory was scarce. At that time, a built-in array in C required you to specify how many items the array could contain and the program would reserve that amount of memory. Reserving that memory meant it could not be used for the rest of the program or any other programs running at the same time, even if the memory was never filled. One memory-scarce machines, you could easily run out of available memory using arrays. Linked lists were created to work around this problem.

Though originally intended for better memory management, linked lists also became popular when developers didn’t know how many items an array would ultimately contain. It was much easier to use a linked list and add values as necessary than it was to accurately guess the maximum number of values an array might contain. As such, linked lists are often used as the foundation for built-in data structures in various programming languages.

The built-in JavaScript Array type is not implemented as a linked list, though its size is dynamic and is always the best option to start with. You might go your entire career without needing to use a linked list in JavaScript but linked lists are still a good way to learn about creating your own data structures.

The design of a linked list

The most important part of a linked list is its node structure. Each node must contain some data and a pointer to the next node in the list. Here is a simple representation in JavaScript:

class LinkedListNode {

constructor(data) {

this.data = data;

this.next = null;

}

}

In the LinkedListNode class, the data property contains the value the linked list item should store and the next property is a pointer to the next item in the list. The next property starts out as null because you don’t yet know the next node. You can then create a linked list using the LinkedListNode class like this:

// create the first node

const head = new LinkedListNode(12);

// add a second node

head.next = new LinkedListNode(99);

// add a third node

head.next.next = new LinkedListNode(37);

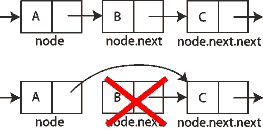

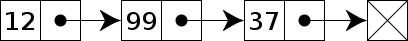

The first node in a linked list is typically called the head, so the head identifier in this example represents the first node. The second node is created an assigned to head.next to create a list with two items. A third node is added by assigning it to head.next.next, which is the next pointer of the second node in the list. The next pointer of the third node in the list remains null. The following image shows the resulting data structure.

The structure of a linked list allows you to traverse all of the data by following the next pointer on each node. Here is a simple example of how to traverse a linked list and print each value out to the console:

let current = head;

while (current !== null) {

console.log(current.data);

current = current.next;

}

This code uses the variable current as the pointer that moves through the linked list. The current variable is initialized to the head of the list and the while loop continues until current is null. Inside of the loop, the value stored on the current node is printed and then the next pointer is followed to the next node.

Most linked list operations use this traversal algorithm or something similar, so understanding this algorithm is important to understanding linked lists in general.

The LinkedList class

If you were writing a linked list in C, you might stop at this point and consider your task complete (although you would use a struct instead of a class to represent each node). However, in object-oriented languages like JavaScript, it’s more customary to create a class to encapsulate this functionality. Here is a simple example:

const head = Symbol("head");

class LinkedList {

constructor() {

this[head] = null;

}

}

The LinkedList class represents a linked list and will contain methods for interacting with the data it contains. The only property is a symbol property called head that will contain a pointer to the first node in the list. A symbol property is used instead of a string property to make it clear that this property is not intended to be modified outside of the class.

Adding new data to the list

Adding an item into a linked list requires walking the structure to find the correct location, creating a new node, and inserting it in place. The one special case is when the list is empty, in which case you simply create a new node and assign it to head:

const head = Symbol("head");

class LinkedList {

constructor() {

this[head] = null;

}

add(data) {

// create a new node

const newNode = new LinkedListNode(data);

//special case: no items in the list yet

if (this[head] === null) {

// just set the head to the new node

this[head] = newNode;

} else {

// start out by looking at the first node

let current = this[head];

// follow `next` links until you reach the end

while (current.next !== null) {

current = current.next;

}

// assign the node into the `next` pointer

current.next = newNode;

}

}

}

The add() method accepts a single argument, any piece of data, and adds it to the end of the list. If the list is empty (this[head] is null) then you assign this[head] equal to the new node. If the list is not empty, then you need to traverse the already-existing list to find the last node. The traversal happens in a while loop that start at this[head] and follows the next links of each node until the last node is found. The last node has a next property equal to null, so it’s important to stop traversal at that point rather than when current is null (as in the previous section). You can then assign the new node to that next property to add the data into the list.

Traditional algorithms use two pointers, a current that points to the item being inspected and a previous that points to the node before current. When current is null, that means previous is pointing to the last item in the list. I don’t find that approach very logical when you can just check the value of current.next and exit the loop at that point.

The complexity of the add() method is O(n) because you must traverse the entire list to find the location to insert a new node. You can reduce this complexity to O(1) by tracking the end of the list (usually called the tail) in addition to the head, allowing you to immediately insert a new node in the correct position.

Retrieving data from the list

Linked lists don’t allow random access to its contents, but you can still retrieve data in any given position by traversing the list and returning the data. To do so, you’ll add a get() method that accepts a zero-based index of the data to retrieve, like this:

class LinkedList {

// other methods hidden for clarity

get(index) {

// ensure `index` is a positive value

if (index > -1) {

// the pointer to use for traversal

let current = this[head];

// used to keep track of where in the list you are

let i = 0;

// traverse the list until you reach either the end or the index

while ((current !== null) && (i < index)) {

current = current.next;

i++;

}

// return the data if `current` isn't null

return current !== null ? current.data : undefined;

} else {

return undefined;

}

}

}

The get() method first checks to make sure that index is a positive value, otherwise it returns undefined. The i variable is used to keep track of how deep the traversal has gone into the list. The loop itself is the same basic traversal you saw earlier with the added condition that the loop should exit when i is equal to index. That means there are two conditions under which the loop can exit:

current is null, which means the list is shorter than index.

i is equal to index, which means current is the node in the index position.

If current is null then undefined is returned and otherwise current.data is returned. This check ensures that get() will never throw an error for an index that isn’t found in the list (although you could decide to throw an error instead of returning undefined).

The complexity of the get() method ranges from O(1) when removing the first node (no traversal is needed) to O(n) when removing the last node (traversing the entire list is required). It’s difficult to reduce complexity because a search is always required to identify the correct value to return.

Removing data from a linked list

Removing data from a linked list is a little bit tricky because you need to ensure that all next pointers remain valid after a node is removed. For instance, if you want to remove the second node in a three-node list, you’ll need to ensure that the first node’s next property now points to the third node instead of the second. Skipping over the second node in this way effectively removes it from the list.

The remove operation is actually two operations:

Find the specified index (the same algorithm as in get())

Remove the node at that index

Finding the specified index is the same as in the get() method, but in this loop you also need to track the node that comes before current because you’ll need to modify the next pointer of the previous node.

There are also four special cases to consider:

The list is empty (no traversal is possible)

The index is less than zero

The index is greater than the number of items in the list

The index is zero (removing the head)

In the first three cases, the removal operation cannot be completed, and so it makes sense to throw an error; the fourth special case requires rewriting the this[head] property. Here is what the implementation of a remove() method looks like:

class LinkedList {

// other methods hidden for clarity

remove(index) {

// special cases: empty list or invalid `index`

if ((this[head] === null) || (index < 0)) {

throw new RangeError(`Index ${index} does not exist in the list.`);

}

// special case: removing the first node

if (index === 0) {

// temporary store the data from the node

const data = this[head].data;

// just replace the head with the next node in the list

this[head] = this[head].next;

// return the data at the previous head of the list

return data;

}

// pointer use to traverse the list

let current = this[head];

// keeps track of the node before current in the loop

let previous = null;

// used to track how deep into the list you are

let i = 0;

// same loops as in `get()`

while ((current !== null) && (i < index)) {

// save the value of current

previous = current;

// traverse to the next node

current = current.next;

// increment the count

i++;

}

// if node was found, remove it

if (current !== null) {

// skip over the node to remove

previous.next = current.next;

// return the value that was just removed from the list

return current.data;

}

// if node wasn't found, throw an error

throw new RangeError(`Index ${index} does not exist in the list.`);

}

}

The remove() method first checks for two special cases, an empty list (this[head] is null) and an index that is less than zero. An error is thrown in both cases.

The next special case is when index is 0, meaning that you are removing the list head. The new list head should be the second node in the list, so you can set this[head] equal to this[head].next. It doesn’t matter if there’s only one node in the list because this[head] would end up equal to null, which means the list is empty after the removal. The only catch is to store the data from the original head in a local variable, data, so that it can be returned.

With three of the four special cases taken care of, you can now proceed with a traversal similar to that found in the get() method. As mentioned earlier, this loop is slightly different in that the previous variable is used to keep track of the node that appears just before current, as that information is necessary to propely remove a node. Similar to get(), when the loop exits current may be null, indicating that the index wasn’t found. If that happens then an error is thrown, otherwise, previous.next is set to current.next, effectively removing current from the list. The data stored on current is returned as the last step.

The complexity of the remove() method is the same as get() and ranges from O(1) when removing the first node to O(n) when removing the last node.

Making the list iterable

In order to be used with the JavaScript for-of loop and array destructuring, collections of data must be iterables. The built-in JavaScript collections such as Array and Set are iterable by default, and you can make your own classes iterable by specifying a Symbol.iterator generator method on the class. I prefer to first implement a values() generator method (to match the method found on built-in collection classes) and then have Symbol.iterator call values() directly.

The values() method need only do a basic traversal of the list and yield the data that each node contains:

class LinkedList {

// other methods hidden for clarity

*values(){

let current = this[head];

while (current !== null) {

yield current.data;

current = current.next;

}

}

[Symbol.iterator]() {

return this.values();

}

}

The values() method is marked with an asterisk (*) to indicate that it’s a generator method. The method traverses the list, using yield to return each piece of data it encounters. (Note that the Symbol.iterator method isn’t marked as a generator because it is returning an iterator from the values() generator method.)

Using the class

Once complete, you can use the linked list implementation like this:

const list = new LinkedList();

list.add("red");

list.add("orange");

list.add("yellow");

// get the second item in the list

console.log(list.get(1)); // "orange"

// print out all items

for (const color of list) {

console.log(color);

}

// remove the second item in the list

console.log(list.remove(1)); // "orange"

// get the new first item in the list

console.log(list.get(1)); // "yellow"

// convert to an array

const array1 = [...list.values()];

const array2 = [...list];

This basic implementation of a linked list can be rounded out with a size property to count the number of nodes in the list, and other familiar methods such as indexOf(). The full source code is available on GitHub at my Computer Science in JavaScript project.

Conclusion

Linked lists aren’t something you’re likely to use every day, but they are a foundational data structure in computer science. The concept of using nodes that point to one another is used in many other data structures are built into many higher-level programming languages. A good understanding of how linked lists work is important for a good overall understanding of how to create and use other data structures.

For JavaScript programming, you are almost always better off using the built-in collection classes such as Array rather than creating your own. The built-in collection classes have already been optimized for production use and are well-supported across execution environments.

Computer science in JavaScript 2019: Linked list

Back in 2009, I challenged myself to write one blog post per week for the entire year. I had read that the best way to gain more traffic to a blog was to post consistently. One post per week seemed like a realistic goal due to all the article ideas I had but it turned out I was well short of 52 ideas. I dug through some half-written chapters what would eventually become Professional JavaScript and found a lot of material on classic computer science topics, including data structures and algorithms. I took that material and turned it into several posts in 2009 and (and a few in 2012), and got a lot of positive feedback on them.

Now, at the ten year anniversary of those posts, I’ve decided to update, republish, and expand on them using JavaScript in 2019. It’s been interesting to see what has changed and what hasn’t, and I hope you enjoy them.

What is a linked list?

A linked list is a data structure that stores multiple values in a linear fashion. Each value in a linked list is contained in its own node, an object that contains the data along with a link to the next node in the list. The link is a pointer to another node object or null if there is no next node. If each node has just one pointer to another node (most frequently called next) then the list is considered a singly linked list (or just linked list) whereas if each node has two links (usually previous and next) then it is considered a doubly linked list. In this post, I am focusing on singly linked lists.

Why use a linked list?