Nicholas C. Zakas's Blog, page 10

March 27, 2013

Internet Explorer 11′s user-agent string: What does it mean?

Over the past few days, people have been going a little crazy over the announcement of the Internet Explorer 11 user-agent string. User-agent string announcements are typically met with a keen eye as we are still horribly tied to user-agent sniffing on servers around the world. And so when some beta testers leaked an Internet Explorer 11 user-agent string, people sat up and paid attention. The string in question, reported by Neowin[1], looks like this:

Mozilla/5.0 (IE 11.0; Windows NT 6.3; Trident/7.0; .NET4.0E; .NET4.0C; rv:11.0) like Gecko

If you’ve read my history of user-agent strings post, then you’re aware of the sinister history of user-agent strings and how browsers try to trick servers into believing that they are other browsers. Internet Explorer 3 actually began the practice by using “Mozilla” in the user-agent string so it would be identified by servers trying to filter for Netscape.

If this user-agent string is the final one (Microsoft hasn’t confirmed or denied this is the user-agent string), then it shows how one can manipulate the user-agent string to get different results. For comparison, here are a few different user-agent strings:

Internet Explorer 10

Mozilla/5.0 (compatible; MSIE 10.0; Windows NT 6.1; Trident/6.0)

Firefox 19 (Windows 7)

Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 6.1; WOW64; rv:19.0) Gecko/20100101 Firefox/19.0

Safari 6

Mozilla/5.0 (Macintosh; Intel Mac OS X 1076) AppleWebKit/536.26.17 (KHTML like Gecko) Version/6.0.2 Safari/536.26.17

Chrome 25 (Windows 7)

Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 6.1; WOW64) AppleWebKit/537.22 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/25.0.1364.172 Safari/537.22

In the past, it was easy to identify Internet Explorer by searching for the string “MSIE” in the user-agent string. If present, the browser is Internet Explorer. When Gecko was the embedded webview of choice, many simply looked for “Gecko” in the user-agent string to determine if it was a Gecko-powered browser (and therefore likely to behave as Firefox). That approach fell apart when Safari decided to add “like Gecko” into the middle of its user-agent string. Not long ago, WebKit overtook Gecko as the embeddable webview of choice, and so many started looking for “Firefox” in the user-agent string to specifically identify Firefox.

Chrome came along and wanted to be identified as Safari, so it pretty much copied the Safari user-agent string and added a “Chrome” identifier. Simple browser type detection based on user-agent string meant you would need to look for certain tokens in order:

If “MSIE” is present, it’s Internet Explorer.

Else if “Firefox” is present, it’s Firefox.

Else if “Chrome” is present, it’s Chrome.

Else if “Safari” is present, it’s Safari.

Else if “WebKit” is present, it’s a WebKit-based browser.

Else if “Gecko” is present, it’s a Gecko-based browser.

So if the Internet Explorer 11 user-agent string is the final one, it causes some interesting logic to happen in this case. In short, by removing “MSIE” in favor of “IE”, the browser is forcing itself to not be identified as Internet Explorer (step 1). By adding “like Gecko” at the end, it is self-selecting into the category of Gecko-based browsers (step 6).

Gecko- and WebKit-based browsers both are considered to have better standards support than Internet Explorer (generally well-deserved prior to IE10), so tricking servers into identifying IE11 as a Gecko-based browser could mean that the browser can handle the same content (JavaScript, CSS) as Firefox. Of course, that’s usually not the case, especially when it comes to vendor-prefixed functionality. Will IE11 support moz-prefixed functionality?

Is it wise for Internet Explorer 11 to try to hide its identity? I’m sure in some convoluted way it makes sense based on how web applications are serving up different content based on user-agent strings. I still have hope for a day when user-agent strings reflect the actual browser rather than trying to trick servers into serving the correct content, but for now, this is just a continuation of a long, sad browser user-agent lineage.

References

IE11 to appear as Firefox to avoid legacy IE CSS (Neowin)

February 26, 2013

What kind of a software engineer do you want to be known as?

Around this time every year, companies start doing their annual reviews. Coincidentally, software engineers start wondering what their peers and managers will be saying about them. Throughout my career I’ve always watched as colleagues worried about the results of their annual review. Will they get that promotion? Will they get that raise? Or will they be told that they are not performing up to expectations? All of this happens, like clockwork, once a year.

Annual reviews are a reminder that your reputation matters. For most of the year, software engineers don’t care at all what anybody else thinks as long as they’re getting the job done. Then annual reviews come along and we realize we might have rubbed some people the wrong way. I know software engineers who year over year always feel like their review is incorrect and unfair (though I’m sure other occupations have similar issues). What makes it more difficult for software engineers is that we deal so much with code that we sometimes forget how important it is to deal with people. The code isn’t going to give us a negative review so long as it works. Then again, you’re expected to write code that works, so your review only ever reflects when you don’t write code that works.

The rest of the review is based on what people say about you. They are your colleagues and your managers. And you probably didn’t even stop to think about that until around review time. If you’ve ever received a review that has been a complete shock to you, that means you didn’t spend enough time during the year to figure out what kind of the software engineer you want to be known as.

Never be surprised again

It’s been a long time since I had an annual review that surprised me. My last manager even came to expect it from me, as he would usually begin our conversations by saying, “I’m pretty sure you know what this is going to say.” He was right. It was very easy for me to predict what would show up on my annual review for one simple reason: I had already decided what I wanted to show up on the annual review the year before.

This is probably different than the way you’ve ever thought about annual reviews. Most of the time, you meet with your manager and set goals for the next year, and then your annual review is a checkpoint to see if you achieve those goals. Unfortunately, the goals are typically task oriented such as, “learn about Node.js”. It’s relatively easy to see if you’ve achieve those goals. What most people never stop and think about is what you would like to see on your annual review next year.

Stop and think about that. Decide right now what it is that you want your annual review to say next year and then take the steps necessary to make that happen. Keep in mind that your annual review typically reflects your reputation in addition to your technical work. The technical work takes care of itself but the reputation piece is one that you must actively work on.

Your reputation

Do you have any idea what your reputation at work is right now? If not, ask some colleagues that you trust to tell you how they view you as a coworker. Listen closely for adjectives because that’s what makes up your reputation. Then decide, is that a reputation that you want? Or is there one that would serve you better? What kind of a software engineer do you want to be known as?

Do you want to be known as the one who always shows up late and in a bad mood? Do you want to be known as the one who happily takes on complex problems? Do you want to be known as the one who smells badly? All of these things are within your control. You can create the reputation that you want for yourself, it just takes a little bit of planning. Everyone has a professional reputation but not everyone takes the steps to actively evolve that reputation. And believe it or not, as you get more experienced, your reputation starts to matter even more than your actual work.

If you stop and think about it, writing code is something that a lot of people do. You can hire someone cheaply out of college to write code and it may not be as good as an experienced software engineer, but if it’s close enough, that’s usually all you need. So if your programming acumen is the only thing that you focus on, you aren’t improving your position in the company. What matters far more are the soft skills that you have along the way. Do people enjoy working with you? Do you add something over and above your coding skill?

An example

The last time I stopped and thought about the kind of software engineer I wanted to be known as, I came up with a list of things that I wanted people to say about me on my annual review. These things reflected not necessarily what I was already doing, but what I would aspire to do in the next year. The things I wanted people to say about me on my annual review were:

Nicholas is fun to work with.

Nicholas cares about the career development of his peers.

I trust Nicholas to work on important projects.

If Nicholas is working on something, I know that it will get done correctly.

Nicholas is capable of learning new things quickly.

This is just a sampling of some of the things I wanted to see on my annual review at different points in time. Note that they all have to do with how others perceive me rather than the quality of the code that I wrote.

Next steps

Once you decide what you’d like to see on your annual review, the next step is to figure out how to make that happen. This is a little bit more difficult than other task-oriented goals because it relies on the opinions of other people. That being said, it’s certainly not impossible. You just need to stop and think about how your actions affect how other people see you.

Take the example of being fun to work with. Why would people say that about you? Well first and foremost, you have to be reliable. That means showing up on time, completing tasks that are assigned to you, and being a good team member. It’s not fun to work with someone who is unreliable. Assuming that you are reliable, then “fun” is achieved by having good relationships with those on your team. That means talking about things other than work, getting to know people outside of the code they write in the job that they do. It could also mean that you’re the one who starts Nerf gun wars or helps to plan team activities. The bottom line is that people enjoy working directly with you and would welcome the chance to do it again in the future.

You can take all of your reputation goals and break them down in that way. Almost all of them are reflections on how you interact with other people. As you go through the year, keep an eye out for interactions that run counter to your goals or strengthen them. For example, if you got into an argument with a colleague, how did that argument resolve? Did you both end up feeling resentful and not wanting to work with the other person? Or were you able to reach an understanding that was mutually beneficial? Any time and interaction doesn’t quite go smoothly, that’s a good time to review your reputation goals and see how that interaction affects them.

Conclusion

Your reputation as a software engineer matters. It’s something that you should actively seek to develop throughout your career because that’s what sets you apart from everyone else who can write the same code that you do. As you get more experienced, your reputation matters more and more, and can be the reason that you either get or miss out on new opportunities. As software engineers, we spend so much time thinking about code that we often neglect personal relationships with our colleagues. Yet our colleagues are the ones who contribute to our annual reviews and ultimately to our success. Watch your interactions with others, try to establish personal relationships with people, and frequently review your reputation goals to see if you’re on track. Hopefully at this time next year, your annual review won’t be such a big surprise.

February 21, 2013

On joining Box

I left Yahoo a year and half ago in search of new challenges. I left to chase the dream of startup life with some friends while consulting to pay my bills. I had a lot of fun doing both, starting a new company completely from scratch and getting to work with some awesome companies as a consultant. The original plan was for me to do that for three months while we sought funding and then join the startup full time.

As so many startup founders know, the path to success consists of unexpected twists and turns, and rarely does anything go the way you plan. And so 18 months after I planned on consulting for 3 months, I was still consulting. The funding hadn’t materialized. It was time to for some soul searching.

Truth be told, though I had fun consulting, it left me feeling unfulfilled. I’ve always enjoyed working on products and never enjoyed hypothetical benchmarking or problem solving. I’ve always loved learning something really cool while working on a product and then sharing that information with the world. That’s what I enjoyed most about working at Yahoo, and I knew that was something I wanted again.

Also, I’ve discovered that my writing and speaking is incredibly important to me. These are more than just adjunct things I do from time to time, they are a vital driving force in my life. I love learning and I love teaching what I’ve learned to others.

Through a series of random interactions, I came to have a conversation with Sam Schillace at Box. If his name looks familiar, it’s because he was part of the team that created Writely (ultimately sold to Google and went on to become Google Docs). We had a really good initial conversation and then several followups.

As so often happens, once you know and like someone at a company, you start to consider working there. I did my due diligence and, after chatting a bit more with Sam, decided that Box would be a good fit.

There were a lot of things that attracted me to Box. First, it’s a small but not tiny company. Before Yahoo, I worked at several companies around this size and always felt that to be my sweet spot. I like working in a place where I can get to know everyone and have a big impact. Second, the company is growing like crazy, so there is a lot of interesting work to do.

But most of all, I’m excited about helping to define and grow a culture of front-end engineering excellence at Box. I’ll be working internally to make Box a hub of great front-end engineering practices and will continue to write and give talks (both related directly to Box and not).

I’m looking forward to this next step in my career and in working with a great group of engineers to make an already kickass product even better. In the short term, I may be a bit quieter than usual as I try to get up to speed at work, but long term you can still expect me to share my thoughts on a regular basis.

For now, I’ve got work to do.

February 12, 2013

Making an accessible dialog box

In today’s web applications, dialog boxes are about as common place as they are in desktop applications. It’s pretty easy to show or hide an element that is overlayed on the page using a little JavaScript and CSS but few take into account how this affects accessibility. In most cases, it’s an accessibility disaster. The input focus isn’t handled correctly and screen readers aren’t able to tell that something is changed. In reality, it’s not all that difficult to make a dialog that’s fully accessible, you just need to understand the importance of a few lines of code.

ARIA roles

If you want screen reader users to be aware that a dialog has popped up, then you’ll need to learn a little bit about Accessible Rich Internet Applications (ARIA) roles. ARIA[1] roles supply additional semantic meaning to HTML elements that allow browsers to communicate with screen readers in a more descriptive way. There are a large number of roles that alter the way screen readers perceive different elements on the page. When it comes to dialogs, there are two of interest: dialog and alertdialog.

In most cases, dialog is the role to use. By setting this as the value of the role attribute on an element, you are informing the browser that the purpose of the element is as a dialog box.

When an element with a role of dialog is made visible, the browser tells the screen reader that a new dialog has been opened. That lets the screen reader user recognize that they are no longer in the regular flow of the page.

Dialogs are also expected to have labels. You can specify a label using either the aria-label attribute to indicate the label text or the aria-labelledby attribute to indicate the ID of the element that contains the label. Here are a couple of examples:

New Message

In the first example, the aria-label attribute is used to specify a label that is only used by screen readers. You would want to do this when there is no visual label for the dialog. In the second example, the aria-labelledby attribute is used to specify the ID of the element containing the dialog label. Since the dialog has a visual label, it makes sense to reuse that information rather than duplicate it. Screen readers announce the dialog label when the dialog is displayed.

The role of alertdialog is a specialized type of dialog that is designed to get a user’s attention. Think of this as a confirmation dialog when you try to delete something. An alertdialog has very little interactivity. It’s primary purpose is to get the user’s attention so that an action is performed. Compare that to a dialog, which may be an area for the user to enter information, such as writing a new e-mail or instant message.

When an alertdialog is displayed, screen readers look for a description to read. It’s recommended to use the aria-describedby element to specify which text should be read. Similar to aria-labelledby, this attribute is the ID of an element containing the content to read. If aria-describedby is omitted, then the screen reader will attempt to figure out which text represents the description and will often choose the first piece of text content in the element. Here’s an example:

Are you sure you want to delete this message?

This example uses an element to contain the description. Doing so ensures that the correct text will be read when the dialog is displayed.

Even if you omit the extra attributes and just use the appropriate role for your dialogs, the accessibility of the application improves tremendously.

Setting focus to the dialog

The next part of creating an accessible dialog is to manage focus. When a dialog is displayed, the focus should be placed inside of the dialog so users can continue to navigate with the keyboard. Exactly where inside the dialogue focus is set depends largely on the purpose of the dialogue itself. If you have a confirmation dialog with one button to continue in one button to cancel then you may want the default focus to be on the cancel button. If you have a dialog where the user is supposed to enter text, then you may want the focus to be on the text box by default. If you can’t figure out where to set focus, then a good starting point is to set focus to the element representing the dialog.

Since most of the time you will be using a element to represent a dialog, you can’t set focus to it by default. Instead, you’ll need to enable focus on that element by setting the tabIndex property to -1. This allows you to set focus to the element using JavaScript but doesn’t insert the element into the normal tab order. That means users won’t be able to press tab to set focus to the dialog. You can either do this directly in HTML or in JavaScript. For HTML:

New Message

For JavaScript:

var div = document.getElementById("my-dialog");

div.tabIndex = -1;

div.focus();

Once tabIndex is set to -1, you can call focus() on the element just like any other focusable element. Then the user is able to press tab to navigate within the dialog.

Trapping focus

Another accessibility issue with dialogs is making sure that focus doesn’t go back outside of the dialog. In many cases, a dialog is considered to be modal and therefore focus shouldn’t be able to escape the dialog. That the dialog is open and pressing tab ends up setting focus behind the dialogue then it’s incredibly difficult for a keyboard user to get back to the dialogue. So, it’s best to prevent that from happening by using a little bit of JavaScript.

The basic idea behind this technique is to use event capturing to listen for the focus event, a technique popularized by Peter-Paul Koch[2] and now in use by most JavaScript libraries. Since focus doesn’t bubble, you can’t capture it on that side of the event flow. Instead, you can intercept all focus events on the page by using event capturing. Then, you need only determine if the element that received focus is in the dialog or not. If not, set the focus back to the dialog. The code is pretty simple:

document.addEventListener("focus", function(event) {

var dialog = document.getElementById("my-dialog");

if (dialogOpen && !dialog.contains(event.target)) {

event.stopPropagation();

dialog.focus();

}

}, true);

This code listens for the focus event on the document so as to intercept all such events before the target element receives them. Assume a dialogOpen variable is set to true when the dialog is open. When a focus event occurs, this function traps the event and checks to see if the dialog is open, and if so, if the element receiving focus is within the dialog. If both conditions are met, then focus is set back to the dialog. This has the effect of looping focus around from the bottom of the dialogue back to the top. The result is that you can’t tab out of the dialog and so it’s a lot harder for a keyboard user to get lost.

If you are using a JavaScript library, chances are that it has a way of delegating the focus event in such a way that you can achieve this same effect. If you need to support Internet Explorer 8 and earlier without a JavaScript library, then use the focusin event instead.

Restoring focus

The last part of the focus puzzle with dialog has to do with restoring focus to the main part of the page when the dialog is closed. The idea is simple: in order to open the dialog, the user probably activated a link or a button. The focus then shifted into the dialog, where the user accomplish some task and then dismissed the dialog. The focus should move back to the link or button that was clicked to open the dialog so that it’s possible to continue navigating the page. This is an often overlooked aspect of dialog in web applications, but it makes a huge difference.

As with the other sections, this requires very little code to work. All browsers support document.activeElement, which is the element that currently has focus. All you need to do is query this value before showing the dialog and then set focus back to that element when the dialog is closed. For example:

var lastFocus = document.activeElement,

dialog = document.getElementById("my-dialog");

dialog.className = "show";

dialog.focus();

The important part of this code is that it keeps track of the last focused element. That way, all you need to do when the dialog is closed is to set focus back to it:

lastFocus.focus()

In total, this adds to very short lines of code to what you probably have already for your dialog.

Exiting the dialog

The very last piece of the puzzle is to allow the user a quick and easy way to exit the dialog. The best way is to have the Esc key close the dialog. This is the way dialogs work in desktop applications and so it’s very familiar to users. Just listen for the Esc key to be pressed and then exit the dialog, such as:

document.addEventListener("keydown", function(event) {

if (dialogOpen && event.keyCode == 27) {

// close the dialog

}

}, true);

The keyCode value for the Esc key is 27, so you need only look for that during the keydown event. Once received, close the dialog and set focus back to the previously focused element.

Conclusion

As I hope is obvious from this post, it really doesn’t take a lot of extra code to create a dialog that is easily accessible both by screen readers and those who use only a keyboard. For just a few lines of code you can take your users from being incredibly frustrated to being incredibly happy. There are a lot of web applications out there that use pop-up dialogs but very few get all of these pieces correct. Going halfway leads to more frustration than anything else, so I hope this post has inspired you to make your dialogs as accessible as possible.

References

WAI-ARIA (W3C)

Delegating the focus and blur events by Peter-Paul Koch (Quirksmode)

February 5, 2013

What technical recruiters can learn from online dating

I’m on LinkedIn just like most people in the tech industry. If you’re like me, you probably get random messages through LinkedIn from technical recruiters several times a week. Their tactics run the gamut of deliberately ignorant to over-the-top obnoxious and rarely do I feel like I’m being treated as a human being. After watching the behavior of recruiters on LinkedIn (and also in real life), I’ve come to realize that the problem is very similar to online dating.

Online dating

Online dating is basically about supply and demand. There is a supply of single people and they are in demand by other single people. Fair or not, this is frequently set up as women being the supply and the men being the demand. This plays out in real life just as much as an online dating where women get into clubs for free and men have to pay. Men want to go where the women are and so getting the women there first is important.

This was a rude awakening for me the first time I tried online dating. I had been encouraged by a couple of my female friends to sign up and they virtually guaranteed I would be going out on dates immediately. So I filled out my profile and sat back and waited for the e-mails to start flowing in. After a week, without receiving a single e-mail, I wondered what was wrong. After all, they just signed up and immediately were getting 20 or more messages a day. But me? Nothing.

Putting discussions about my desirability or lack thereof aside, what they and I failed to realize is that online dating is a very different experience for men and women. Assuming that a man and a woman are roughly equal level of attractiveness and have the same personality, the woman will be contacted far more frequently than the man. In fact, I’ve heard numerous times from female friends that the day they sign up their inbox is flooded with messages. And no matter how many times I’ve tried online dating (handful over the past decade), I can go months without receiving a single message. Why is it that women don’t contact men as much?

The problem is that there is little incentive for women to search for and communicate with men. The demand is coming right to their front door. Surely there is someone worthwhile in the dozens of e-mails waiting in their inbox. Why search for more candidates when resumes are being hand-delivered to you?

Men, on the other hand, have little hope of meeting anyone without actively searching and contacting women. As a man on a dating site, if you sit by and wait for somebody to contact you, you may find weekend after weekend completely free. Additionally, once you do decide to contact women, your message is just one of the dozens that they’re going to see.

Recruiters on LinkedIn are like the men on online dating sites. They are hoping to meet someone to fill a position, and there are a lot of candidates out there. They need to search for and contact potential candidates in the hopes of getting a response. The problem is made a bit more difficult than online dating because not everyone on LinkedIn is actually looking for a job. Despite that difference, the question is the same: How do you make your message stand out from all the others?

Strategies

Men use several strategies for trying to get women to notice and respond to them online. From my female friends, I verified that these are generally the type of messages that they receive. On LinkedIn, if you aren’t a recruiter that you are the supply (equivalent of the women on an online dating site), so I am actually receiving the type of messages that I imagine women receive on dating sites. The thing I find interesting is that many of the dating site techniques are duplicated by recruiters on LinkedIn. See if any of these sound familiar.

Copy-paste

The first is the least amount of effort and also yields a worst return: sending the same message to everyone. You just come up with a really good message that you literally copy and paste into every message that you send to every girl. The plus side of this approach is that you’re not investing a lot of time and effort into an activity that has a very low rate of return. On the minus side is the fact that generic messages will generally get a lower response rate than personal ones, so the onus is on you to contact much more women in order to make up for that.

Messages of this nature look like the following:

Hi there,

I came across your profile and think we would be a great match! I love to surf and go camping, and I think that we would have a lot of fun together. Hope to hear from you soon.

The message seems nice enough but you’ll note that there is nothing personal about it at all. First, you obviously found the profile otherwise you wouldn’t be able to send a message, so that doesn’t really tell you anything. Of course the fact that you’re writing indicates that you think there is a match. There goes the entire first sentence. The next sentence is just about you and doesn’t really reveal much. The last sentence is just a way to wrap up the message.

This is also a favorite tool of recruiters. Since LinkedIn fills in the name of the person being contacted, that typically isn’t a generic greeting as they would be in an online dating site. Still, the basic pattern is the same. Here’s an actual message I received on LinkedIn from a recruiter:

Hi Nicholas C.,

Our team has reviewed your profile and are very impressed by your skills and experience.

We are working on emerging technologies for our next generation products at [ redacted ]. We are located in the heart of Palo Alto, CA. Amazing offices, super smart people and financially well funded.

Would you be open to speaking with us?

Thank you in advance for your kind reply.

If you look closely, this is almost the exact same e-mail tailored to a professional environment. There is absolutely nothing about the message that specific to me, my skills, or my experience. Here’s another:

Nicholas C.,

I was reading through your background and I wanted to get in touch. I have two opportunities – one in Palo Alto and one in San Mateo that seem like you would be a fit for. Can you let me know if you are interested in hearing about new opportunities and when might be a good time to chat?

I’m not even convinced this person has any idea what I do let alone what I would like to do for my next job.

Half-hearted

The half-hearted approach is an evolution of copy-paste. Instead of sending the exact same message to everyone, you just change the first line to be more specific to that person. The entire rest of the message is the same for everybody, so you’re not putting in a lot of extra effort, and changing the first sentence (the first one that someone reads) may be enough to get them to read the rest.

Messages using this approach tend to look like this:

Hi SmartGirl456,

I love the hat in your profile picture, very cool. I love to surf and go camping, and I think that we would have a lot of fun together. Hope to hear from you soon.

So the greeting is personalized and the first sentence is plausibly personal. The rest of the message is completely generic and obviously the person who wrote it didn’t want to put much effort into it. Instead of following up with another sentence about hats, the message digresses back into generic boilerplate.

Here’s an actual message I received on LinkedIn:

Hi Nicholas C.,

I saw your profile and I thought you may be interested in a full time Web Performance Engineer Opening we have in our San-Mateo office.

This position will offer the opportunity to work on software that runs one of the largest distributed systems in the world. You will be an integral part of our aggressive growth strategy for creating highly inventive technology solutions for our customers, driving more and more traffic on the Internet. If you want to work on technology problems that are interesting and challenging, then this is the role for you.

Please let me know if you are interested in discussing this opportunity in more detail.

This is a little bit better. The first sentence at least indicates that this recruiter did a cursory examination of my profile. I do talk about Web performance on my profile, so that first sentence is actually relevant to me. The rest of the message is definitely impersonal and just pasted in. As with the purely copy-paste approach, this one leaves me feeling like the recruiter probably sends a very similar e-mail to dozens of people. Here’s another:

Nicholas –

Just stumbled on your profile and will first say … this message is indeed intended to recruit YOU!

I tend to be direct …

I work with Tier-1 VCs and early stage startups and I’m working with a company in SF that needs a Lead guy like you. They are a great story … almost profitable and only round of funding. They are going into a major growth phase and need top talent.

Environment is Python, but they don’t require that experience, even for a lead. They also need JS/HTML5/CSS3 and good, solid *people* on the team.

You interested in discussing?

The relevant part of this message is the first sentence. I put on my LinkedIn profile that I only want to be contacted by recruiters that are interested in me specifically (and not me or someone I know – covered later in this post). So he put a personal first sentence and then copied and pasted the rest. There’s nothing about the rest of the message that’s unique to me at all.

Information blast

This approach encapsulates the attitude that the more you know about me, the more you will like me. So instead of mentioning much about the person you’re contacting, the approach is to give you a time of information about the person writing the message. These females tend to be a little bit longer as they act like many profiles. Here’s an example:

Hi there,

Have you found that special someone yet? I haven’t yet, but I think we might be a good match. I am a recent graduate from business school who just moved to the area from the East Coast. I have a good job and make a good salary. I worked very hard and so when I’m not at work I like to blow off some steam. I love all outdoor sports but don’t mind staying in for a quiet evening either.

I noticed you also like outdoor sports, so I think we would have a good time together. If that sounds interesting to you, that I look forward to speaking with you.

Well, the person who wrote this message gets high grades for proper grammar and spelling, but not much else. This is probably duplicate information from the person’s profile which, if the woman was interested, she would probably go and read it anyway. Even though there’s nothing personal in this message, it has a personal feel to it because the writer is revealing information about himself. The last paragraph is a little bit personal because it mentions something from her profile. However, the likelihood that she got through everything about you (which looks boilerplate) just to get to the one sentence that indicates you’re writing to her specifically is pretty slim.

Here’s one from LinkedIn:

Hi Nicholas C.,

I came across your profile while looking for folks interested in web development. My name is [redacted] and I’m part of the early team at [redacted], a funded startup in Berkeley.

We’re a team of mostly engineers building a discovery service that connects people with entertainment, people and products that appeal specifically to them. Our early tests have been very positive, and we’re gearing up for a product launch this summer.

We recently raised a new round of funding, and we’re growing quickly. Our engineering team has a strong passion for building great software, and based on your experience with Yahoo and your book for Wiley I thought you might be interested in hearing more about our team and opportunities for web development roles.

Please let me know if you’re up for chatting sometime about [redacted].

So I get blasted with information about a company I’ve never heard of before. There is a sentence in the third paragraph that is specific to me and my background, but I never got to that paragraph because the first two were just a blast of information about the company. Here’s another:

Dear Nicholas C.,

You are 3 steps from working at [redacted]! Our recruiting process is “fast” just like our [redacted] [URL redacted] check out our products, email me your resume, and let me know which ONE position fits best, when you can begin working onsite in San Francisco OR Sunnyvale, what is your ability to work legally for any employer in the USA, name several times over the next couple of working days when you can be in a quiet place for a 15 minute conversation with me, I will confirm one time via email to confirm

Our Research & Development team is seeking talented system software developers ALL LEVELS, who are strong in C OR C++ OR Python. We are a Linux / Open Source environment and need programmers to create and support new version one products for the cloud.

This one is a real gem. Not only is there nothing about me personally in this message, but I’m blasted with all kinds of information about the company and the recruiting process and then I’m given a long list of things to do. There’s nothing in this message that even indicates the recruiter read my profile or has any idea what I do.

Once again, if the recipient of the message either on a dating site or on LinkedIn doesn’t feel like you were contacting them specifically, you will likely never hear back.

Or someone you know

This is actually one that doesn’t happen on online dating sites but does happen on LinkedIn quite frequently. The reason it doesn’t happen on dating sites is that everyone knows this isn’t the way to get a date. The approach is to act coy as if you’re not interested in the person who you contacted but rather somebody that they might know. Just to show you how silly this is, here’s what I imagine a message to a woman on a dating site would look like using this approach:

Hi SmartGirl456,

I’m looking for a date this weekend and I was wondering if you or someone you know might want to go out with me? Even if you aren’t interested, judging by your profile, you probably know some other women who are. Can’t wait to hear back from you.

It would be completely preposterous for a man to contact a woman with such a message. Yet, this is incredibly commonplace on LinkedIn. Here’s one that I received:

Hi Nicholas,

I am looking to expand our social web development team at [redacted] and was wondering whether you or someone you may know would be interested in full time or consulting gigs?

I always suspect that this is a passive aggressive way of asking if I would be interested in the job. As if I would say, “Actually, why do you want to speak to my friends? I’m the one that you want!” Here’s another:

Hello,

I am reaching out to obviously [sic] for your specific background or if anyone you may know may be interested in 2 great opportunities here in San Francisco. My company, [redacted], is looking for a Sr. PHP Developer/Front End Engineer and UI/UX Designer Developer for a well funded Green/Sustainable emerging technology company for the [redacted]. Please contact me directly or via email. I will of course share all the details and job descriptions with you. They are looking to meet immediately. Best regards for your help.

This is one of the most insulting type of messages that I’ve received on LinkedIn. If I ever see “or someone you know” in the message, I delete it immediately. I honestly can’t believe recruiters think that would work.

Harassment

Any guy who has spent any amount of time on an online dating site learns pretty quickly that you don’t get anywhere by e-mailing a woman multiple times. If you e-mail once and she doesn’t respond, you don’t send another e-mail asking if she got the previous one. Yes, she got the previous one and she wasn’t interested, so let it go. Yes, it’s personal, she doesn’t like you. She also doesn’t know you, so who really cares? If you’re a man on an online dating site, you must accept that this form of passive rejection will happen frequently. You only solidify that you’re not someone she’s interested in by continuing to pester her.

This is a lesson that recruiters don’t seem to get. When you continue to contact someone who isn’t interested in talking to you, that’s harassment. I can’t tell you how many times I have deleted an e-mail that a recruiter sends only to get a follow-up e-mail in today’s asking if I got the previous e-mail. In some cases, I even have received a third e-mail asking if I got the previous two.

I know that in some delusional minds, this might come off as being complementary. Boy, this person thought enough of me to e-mail a second or third time! They must really be interested! But the opposite is true. It tells me that you have no respect for me or my time.

Whether you’re on a dating site or on LinkedIn, if you contact someone and they don’t respond, chances are it’s not because they just didn’t see your message. You are rejected, let it go.

What works?

So after all of that, what actually works? In my various attempts at online dating, the best results that I’ve ever had were with short, personal messages that showed I had actually read through her profile. The most important thing is I made the messages about her and not about me. If she’s interested in me after reading it, she can always go to my profile. So messages such as this tend to go over better:

Hi SmartGirl456,

I love that picture of you at Fenway Park! I’m also from Boston, so I know that this can seem like a strange alternate dimension where sports doesn’t matter so much. Are you still loyal to the hometown favorites even after seven years?

Just about the only mention of me is that I’m also from Boston and that’s just to provide some context for the next couple of sentences. The message might seem simplistic, but it’s intensely personal and about her. Every sentence is related to her in some way in the entire message shows that I actually read your profile. I saw her photo and identified where it was taken, I noticed that she was from Boston, and I also noticed that she has been in California for seven years. In short, I approached her as someone who’s interested in learning more about her to see if we are a match rather than trying to get her to know more about me to see if we’re a match.

While I haven’t received a lot of messages that fit this mold, here’s one that comes close:

Hi Nicholas C.,

[redacted] is looking for a hands on development manager to lead a team of talented software engineers building a cutting edge, fast and interactive Web application that incorporates the best user experience patterns and technologies available.

As I reviewed your profile it appeared to me that you are particularly suited to define and implement a next generation UI architecture while ensuring continued functionality of the existing system.

I would welcome the opportunity to speak with you soon to discuss the possibility of your joining our team.

You can reach me at [redacted] at any time to get the ball rolling or by emailing me at [redacted]

While I think the first paragraph isn’t all that necessary, the second paragraph is really good. It could be tightened up (obviously I know you looked over my profile) but has some really good parts to it. The recruiter clearly you read my profile and understands what’s important to me. He then explained how I could do that at the company and left it at that. Short, to the point, and personal. If I were actually looking for a job, I would consider replying to this type of message.

Notice that I said I would consider replying to this type of message, not that I would. Whether or not I actually respond has to do with what’s going on in my life. Do I have any better opportunities that I’m exploring right now? Do I think the commute is something I can live with? Do I think this is a company I would be happy working for? Are writing it good, respectful message gets you into the “maybe” pile, just like it does on an online dating site.

If you are a recruiter, here are a bunch of tips that will get you into the “maybe” pile:

Start by talking about me. I don’t really care who you are, you’re obviously a recruiter for the company that shows up on your profile. Say something that makes me realize you actually read my profile and understand what I do. Something like, “I noticed you have an expertise in web interface architecture, and that’s something [company name] has a need for right now.”

Tell me a little about the position. One or two sentences about the position, where it’s located, what their responsibilities are, and how I would be making an impact. That’s about all I need to know to figure out if I have any interest.

Provide links about the company and position. Rather than pasting in boilerplate information to a message, just provide links to the extra information. If you did a good job describing the positions distinctively, I want to go and read a longer job description as well as read more about the company.

Your contact info. Give me your e-mail address to contact you if I’m interested. I will not be calling you on the phone so there’s no need to include your phone number.

Just like a message on an online dating site, the goal isn’t to close the deal. The goal is to get the other person interested enough to want to learn more. Keep your messages short and to the point and make sure that they are personal. It takes a little more time than the other approaches, but you will get a much higher rate of return this way.

I know that there are really good recruiters out there, because I’m friends with some of them. The problem is that there are so many bad ones that the good ones end up being looped in with them. If you are a recruiter reading this, please take this as advice to help improve yourself. I would much rather get relevant, respectful messages from recruiters even if I’m not interested at the time then continue to get disrespectful, lazy messages that make me want to never read anything I receive through LinkedIn again.

January 29, 2013

You can’t create a button

One of the most important aspects of accessibility is managing focus and user interaction. By default, all links and form controls can get focus. That allows you to use the tab key to navigate between them and, when one of the elements has focus, activate it by pressing the enter key. This paradigm works amazingly well regardless of the complexity of your web application. As long as a keyboard-only user is able to navigate between links and form controls then it’s possible to navigate the application.

Unfortunately, sometimes web developers try to get a bit too clever in creating their interfaces. What if I want something to look like a link but act like a button? Then you end up seeing a lot of code that looks like this:

I'm a button

That code should turn your stomach a little bit. It’s a link that goes nowhere and does nothing. All it does is attach an onclick event handler to give it a purpose. Because the desired appearance for this element currently is link-like, the markup uses a link and JavaScript.

Those who are familiar with ARIA may “fix” the problem by using the following:

I'm a button

By setting the ARIA role to button, you’re now telling the browser and screen readers that this link should be interpreted as a button (that does an action on the page) rather than a link (that navigates you away). This has the same problem as the previous code except that you’re trying to trick the browser into treating the link as if it were a button. In reality, it would be most appropriate to just use button:

I'm a button

The markup to use should never be based on the appearance of a UI element. Instead, you should try to figure out the real purpose of that element and use the appropriate markup. You can always style button to look like a link or a link to look like a button, but those are purely visual distinctions that don’t change the action.

If these were the worst sins of web applications that I have seen, I would be pretty happy. However, there is another even more disturbing trend that I’m seeing. Some Web applications are actually trying to create their own buttons by mixing and matching different parts of HTML, CSS, and JavaScript. Here’s an example:

I'm a button

This is a valiant attempt at creating a button out of a . By setting the tabindex attribute, the developer has assured that keyboard users can navigate to it by using the tab key. The value of 0 adds the elements into the normal tab order so it can receive focus just like any other link or button without affecting the overall tabbing order. The role informs the browser and screen readers that this element should be treated as a button and the onclick describes the behavior of the button.

To anyone using a mouse, assuming the styling is correct, there is no distinction between this element and an actual button. You move the mouse over and click down and an action happens. If you’re using a keyboard, however, there is a subtle but important difference between this and a regular button: almost all browsers will not fire the click event when the element has focus and the enter key is pressed. Internet Explorer, Chrome, Firefox, and Safari all ignore the enter key in this situation (Opera is the only one that fires click).

The enter key fires the click event when used on links and buttons by default. If you try to create your own button, as in the previous example, the enter key has no effect and therefore the user cannot perform that action.

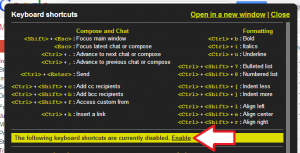

This horrible pattern is found most frequently in Google products. Perhaps the most ironic usage is in Gmail. When you press the ? key, a dialog pops up showing you available keyboard shortcuts and allowing you to enable more advanced shortcuts.

It looks like the word “Enable” is a link, so you press tab a few times to give it focus and press enter. Nothing happens. Why? Because the link is actually neither a linkage nor a button, it’s a . Here’s the actual code:

Enable

Almost exactly the problematic pattern mentioned earlier in this post. So basically in order to turn on keyboard shortcuts you need to be able to use a mouse. In fact, many of the buttons on Gmail are made in this way. If not for the keyboard shortcuts it would basically be unusable without a mouse.

Gmail isn’t the only Google site that uses this pattern. It can be found throughout the network of Google sites, including Google Groups and Google Analytics (which also hides focus rectangles). This alone makes Google products incredibly challenging to use for sighted users who don’t use pointing devices.

If you expect the user to interact with something, then you need to use either a link or button. These have the correct behaviors both in terms of getting focus and activating when the enter key is pressed. Links should be used whenever the action is a navigation (changes the URL) and buttons should be used for all other actions. You can easily styled these to create the visual effect that you want, but nothing can replace the accessibility of the native links and buttons.

January 21, 2013

What the NFL can teach us about diversity in technology

One of the issues that kept popping up in 2012 was that of diversity in technology. A lot of the discussion was centered around the Brit Ruby conference that was cancelled[1]. The conference had posted a lineup of all white male speakers and this didn’t go unnoticed by the tech community. This was followed up by allegations of racism and sexism that in turn made the sponsors of the conference uncomfortable. The sponsors decided to pull out, beating the conference without financial backing, and so the conference was canceled.

The fallout

There was a lot of feedback on the announcement. Some said it was a shame that the conference had to be canceled just because of the lineup. Perhaps it was really hard to find anybody but white male speakers who could make it to Manchester on that day and also deliver a talk on Ruby. It’s entirely possible that was the case. Others said that if the conference could only find white male speakers then it was the organizer’s fault because they weren’t looking for anybody else. It’s entirely possible that was true as well. Still others said that as a conference organizer, you should be promoting diversity and actively trying to create a diverse speaker pool to have the best conference possible. That’s also a good point.

Further discussions around whether or not conferences should invite a minority speaker just to avoid the appearance of discrimination circled around to camps. The first, that no one wants to be a token speaker and that doing so would be insulting not just to the speaker but also to the audience. The second camp says that even the act of doing that helps to promote diversity because it puts a minority in front of an audience and that alone can have a ripple effect for other minorities who have considered speaking.

Since I’m a white male, I’m not qualified to speak on many of these issues. All I can do is look at it from the outside and see if there is anything I can possibly do to improve the situation for everyone. The more I thought about the problem, the more I agreed with Frances Berriman who wrote a post[2] stating why she believed conferences aren’t the problem:

Conferences are not the problem, they are just showing the symptoms of a severe lack of diversity, generally, throughout the industry. We can cover up the warts all we like with bolstered numbers of minority groups on stage, but we should probably be working out how to tackle the actual issue of why so few of them enter the industry, as novices/newbies/entry-levels/graduates etc., in the first place who would later become the experts we seek out to speak.

To summarize, the problem isn’t that there aren’t enough good minority speakers in technology. The problem is that there aren’t enough minorities in technology. Since you can only draw speakers from those who are in the industry then it follows that it would be harder to find minority speakers that it would white male speakers because of the available pool.

That led me to realize, as a football fan, that the NFL is facing a similar issue right now.

The NFL

The NFL has a lot of players, 53 on the main roster and 8 on the practice squad, times 32 teams means potentially 1952 players are in the NFL at any given point in time. That doesn’t even include the people who don’t start on a roster and are added later in the year. Non-white players make up about 65% of the NFL.[3] That statistic is probably not shocking to anybody who has ever watched the game.

What you might be surprised to learn is that only three of the 32 teams have a minority head coach. That means less than 10% of NFL head coaches are minorities even though 65% of players are minorities. In 2013, there were eight head coaches and seven general managers hired by NFL teams and all of them were white males. The NFL isn’t happy about this and they are continually trying to figure out why there is such a large discrepancy between the players and the coaches.

The first attempt at addressing the problem was to adopt the Rooney rule[4], which requires all teams to interview minority candidates for head coach and general manager positions. The rule was enacted in 2003 in order to give minorities a chance at attaining these positions. The reasoning was the same as the reasoning you often hear these days about non-diverse speaker lineups: the problem is that the decision-makers do not come into contact with minorities and therefore aren’t able to select them. The theory was that when decision-makers are forced to seek out minorities then they will also be more likely to hire them simply because of increased exposure.

The league voluntarily adopted the Rooney rule partly to help fend off the threats of unfair hiring practices[5] that were popping up. That is not unlike the public outcries over conference diversity in the technology industry.

By 2006, there were seven minority head coaches in the NFL (22%), a significant improvement over the three present before the Rooney rule (9%). To many, that was a sign that the Rooney rule was working. Perhaps the hallmark moment of the last decade was when the Chicago Bears and Indianapolis Colts faced off in Super Bowl XLI, simultaneously becoming the first African-American head coaches to coach a Super Bowl team. Tony Dungy, the coach of the Colts, then became the first African-American head coach to win a Super Bowl. It seemed like the league was heading in the right direction.

Yet this year, the NFL is back to pre-Rooney rule representation of minorities as head coaches. If all of the teams are following the rules, and teams get fined if they don’t, then why is this still happening? In reality, there are a few things that are going on.

First and foremost, teams don’t usually fire a head coach unless they know who they want to replace him. There are a small number of big-name coaches that everyone will try to get to coach their team. Failing to get one of those coaches, then it becomes more of an open competition. But if the team already knows who they want as their coach then they still have to go through the process of interviewing a minority even though the decision has pretty much been made. That has led to a series of sham interviews with candidates who really didn’t have a chance at getting the position. They didn’t have a chance not because they weren’t qualified but more because the decision had already been made and now the team had to interview someone to satisfy the Rooney rule. A very sticky situation, and one that is eerily similar to the, “all the speakers I want are white males” issue with technology conferences.

Another problem is that groups of coaches tend to stay together. When you hire a head coach, he will bring with him his coordinators and assistants. When one of those people ends up getting hired as a head coach somewhere else, they will take part of that original staff with them to work with. And so the same coaching families keep going around and around. Unless you are part of one of those coaching families, you’ll have a hard time getting a job. Since those coaching families go back decades, back to when the league had very little diversity in coaching, they tend to be made up of more white males than anything else.

And so 10 years after the Rooney rule was put into place, there are questions about its effectiveness that have led the NFL to consider the problem is not solved.

What we can learn

What the NFL has learned is that forcing interviews of minorities doesn’t actually work. Having a sham interview with the candidate whom you have no intention of hiring is definitely insulting. What many are calling for the NFL to do now is to extend the Rooney rule to coordinators and assistant coaches as well. The idea is that qualified head coaching candidates usually make their way through the assistant coach ranks before finally getting head coach position. If the problem is that there aren’t enough qualified minority head-coaching candidates, then it must also be true that there aren’t enough quality minority coordinator and assistant coaches.

In short, people are now saying for the NFL what Frances said for technology: the problem isn’t a lack of diversity that you see in high-profile people, the problem is the lack of diversity that you see everywhere else. There can’t be a good minority head coach without their first being a good minority assistant coach. There can’t be a good female technology speaker unless there is first a good female technologist. Both the NFL and the technology industry are trying to solve the exact same problem: how do you get more minorities into positions that will allow them to grow and develop into the next great head coach or the next great technology speaker? Neither of these grow on trees and none of them are going to change simply because of a rule here or there.

Again, as a white heterosexual male, I’ve never experienced discrimination. It saddens me that anybody has and that people continue to experience it. Solving this problem is incredibly difficult. I know people may look at things like the Rooney rule and say that it was doomed to failure from the start, but doing nothing never brings about change. Change only happens through action, and action can be ineffective, but I would much rather people try than just give up because the problem is too hard.

I don’t have any easy answers. All I know is that I want things to get better and that I’ll take every opportunity I can to help. But the first thing we all have to do is approach the problem of diversity with compassion. People will try a lot of different things in the next few years to improve diversity in technology. Some will work and some will fail. Let’s promise to give credit to the people who make an effort even if the effort doesn’t result in change, because we will never get anywhere by not trying.

References

Why Brit Ruby 2013 was cancelled and why this is not ok (GitHub Gist)

Conferences aren’t the problem by Frances Berriman

Justin Medlock adds to list of black NFL kickers, but he’s not a trend-setter by David Whitley (AOL)

January 15, 2013

Fixing “Skip to content” links

Update (15-Jan-2013): After a few tweets about this and some re-testing, it appears the issue discussed in this post only affects Internet Explorer and Chrome. The post has been updated to reflect this.

If you’ve been doing web development for any amount of time, you have probably come across the recommendation to create a “skip to content” or “skip navigation” link for accessibility purposes[1]. The idea is to have the first link on the page linked to the main content so that those who can’t use a mouse can easily avoid tabbing through all of the site navigation just to get to the main content. The first tab stop on the page is a “skip to content” link that simply links to the container of the main content. Depending on the site, the link might always be visible or might only be visible when focus is set to it. Either way, the HTML looks something like this:

Skip to Content

Basically, this takes advantage of hashes for page navigation. The link to #content automatically moves the user down to the element whose ID is “content”. This type of navigation is very popular on large content sites where pages have a table of contents.

The problem

Although the “skip to content” link approach works most of the time, Internet Explorer 9 and Chrome aren’t obeying the rules. While the visual focus of the browser shifts to the element being linked to, the input focus stays where it was. For example, if I press tab and then enter on a “skip to content” link, the browser will scroll down to that element so I can read the content. If I then press tab again, the input focus moves to the next focusable element after the “skip to content” link, not to the next link in the content area.

The difference between visual focus and input focus is subtle. Visual focus is most often affected by scrolling. When you navigate to an element on the page using a hash, the browser scrolls that element into view, effectively changing the visual focus so you can read. If you use the up and down arrows, they interact with the scrollbar naturally. However, if you use tab to change focus then you end up scrolling back to the previous spot on the page. That’s because the input focus didn’t change along with the visual focus.

This is definitely a but in WebKit[2] and potentially one in Internet Explorer (perhaps one that’s been around for a while[3]). The WebKit one is a bit more innocuous whereas the Internet Explorer one appears to be related to styling. If the element being targeted by the in-page link has a width and height set via CSS, then the focus is set appropriately. Without both dimensions specified, the input focus doesn’t shift in Internet Explorer.

A solution

The best solution I came up with is to use a small piece of JavaScript to create a better behavior. The basic idea is to watch for changes in the URL hash using onhashchange and then set focus to the element that now has visual focus. Since that element is usually a or some other container, these elements aren’t the focusable by default (links and form controls are). To make them focusable, you need only set tabIndex to -1 before calling focus(). Doing so means that the element won’t be in the regular tab order but you can still set focus to it using JavaScript. Here’s the code:

window.addEventListener("hashchange", function(event) {

var element = document.getElementById(location.hash.substring(1));

if (element) {

if (!/^(?:a|select|input|button)$/i.test(element.tagName)) {

element.tabIndex = -1;

}

element.focus();

}

}, false);

I’ve chosen to use the DOM Level 2 method for adding an event handler, but you can just as easily use a browser agnostic approach. The hashchange event is supported back to Internet Explorer 8, so you may want to mix in attachEvent() if you’re supporting that browser as well. Of course, you could also just use a JavaScript library that abstracts that difference away from you.

What I like about this solution is that it doesn’t interfere with what the browser is doing as it shifts visual focus. All it does is wait for that shift to happen and then set focus to the element that you’re already looking at. That allows you to start tapping into the content area immediately while preserving the behavior of the back button.

Conclusion

The “skip to content” links can be a great aid to accessibility. Once Internet Explorer and Chrome fix their buggy implementations, the fix mentioned in this post won’t be necessary. As someone who uses only a keyboard on the web, I would greatly appreciate it if more sites used skips links to help with navigation.

References

Skip Navigation Links (WebAIM)

Skip links and other in page links in WebKit browsers (456 Berea Street)

Keyboard Navigation and Internet Explorer (Juicy Studio)

January 10, 2013

Advice for new and aspiring technical speakers

In a previous post I described the Front End Summit New Speaker Program that I organized while I was still at Yahoo. Since that time, I’ve received several e-mails and questions from people about how to get started speaking without the benefit of such a program. Obviously, it’s possible to become a really good speaker without a formal training program (most of your favorite speakers probably fall into that category) but it isn’t possible to become a really good speaker until you start speaking. The advice in this post echoes the advice that I gave to people who were in the program as well as people who have asked for advice personally.

Your Doubts

The first thing to do is ask yourself why you get that nervous feeling in your stomach when you think about speaking. If you’re reading this post, then you’re probably already over the hump and willing to give it a try, but there may still be doubts in your mind. The most common doubts and fears that new speakers have are:

I’m not an expert, why would anybody want to listen to me?

I’m going to sound stupid.

What if I mess up?

I don’t have anything interesting to say.

These little self-doubts prevent a lot of people from giving talks. I remember before my first talk at a conference I had the same doubts floating in my head. I felt out of place amongst the other speakers as they listed out their achievements. It was only after the conference that I realized they were just people with something to say and the guts to get up in front of a couple hundred people to say it.

All of the doubts that are circulating in your head, all the little negative comments, are all just an expression of fear. Fear is useful when it protects you from lions in the jungle but it’s not very useful in everyday situations like public speaking. Your minds typically reacts with fear to new situations because there might be danger. In terms of public speaking, there is absolutely no danger. Even if you give a horrible talk, there isn’t a lion waiting for you outside the door.

Anytime these thoughts start popping into your head, acknowledge them, don’t try to force them out (that usually just causes more stress). Just tell yourself that this is the result of fear of a new situation. Then tell yourself there are no lions waiting out there to eat you and that you can do this.

Pick a topic you don’t know

This probably flies in the face of most advice out there regarding new speakers. A lot of people tell you to pick a topic that you’re familiar with so as to ease your nerves. I actually believe in doing the opposite. For your first talk, pick something that you don’t know very well as your topic. Doing so opens up a world of opportunity for you.

When you speak about something that you know very well, the tendency is to oversimplify because it’s so fresh in your mind. You fall into the trap of believing that other people know as you know and leave out important tips along the way. Once you become an experienced speaker, it’s a lot easier to avoid these traps with topics that you already know. But as a new speaker, the best way to make sure that that you’re covering the topic well is to pick a topic that you need to research.

The process of learning about a new topic is a magical one. It’s a process that you hope to compress into about 40 minutes on stage with your audience. It’s much easier to do that if you just recently learned the topic. Let your talk be an excuse to learn about something new. Pick an API that you’re unfamiliar with or technology that you’ve never used before and spend a month learning about it. Write down everything that you go through including mistakes that you made and pleasant discoveries. These are the things your audience will be going through as he presents the topic. However, you’ll have a fresh insight into this because you just learned the topic yourself.

Speaking about a topic you don’t know well also avoids the common trap of thinking that you have to be an expert to give a talk. You don’t! An unfamiliar topic is a good subconscious trick to let yourself off the hook of being an expert. You don’t have to be an expert to give a talk, you just have to have an understanding of the topic and the way to present it.

So find a topic that you’re interested in but don’t understand very well yet. Spend some time researching it and create your talk around that topic. Now, instead of trying to figure out what to say about something, you can recount the story of how you learned about the topic. It’s the same thing you do with friends and family over dinner when people share their experiences of the day. A newly-learned topic will be much fresher in your mind when you go to give the talk.

Introduce yourself

Before starting to speak about the topic, take a minute and introduce yourself to the audience. Tell them who you are, where you work, and anything else that might be interesting about you. Basically, you want the audience to understand why they should be listening to you. Once again, you don’t have to be an expert to have people listen to you. The people in the audience might have the same job as you do different company than knowing that helps to put what you have to say and perspective.

Just make sure to keep this intro short, one minute max. I was once at a time where the presenter was fairly well known yet still felt the need to talk for about 7 minutes about the various things he had accomplished. Everyone in the room already knew who he was and why he was famous so the introduction felt very self-serving and made the audience uneasy.

Don’t do that. There’s no need to recite your entire resume. if you’ve ever seen me talk, I usually introduce myself with something like this: "I, my name is Nicholas Zakas, and I’m cofounder of a startup called WellFurnished. I’ve also written several books on JavaScript, of which you should buy many copies." Then I move on.

Tell a story

My favorite piece of advice that I give to new speakers is to tell a story. Don’t just go up in front of people and start rattling off facts and statistics. Storytelling is a great way to get a point across without losing the audience. There’s no special trick to storytelling, it’s something that you already do probably every day with your friends. The story is something that has a beginning, a middle, and an end. The mark of a good story is being able to look back from the end to the beginning and see the logical progression that got you to that point.

With technical topics, the beginning is usually a problem. You want to try to do something and you don’t know how to do it. The answer is the API or technique or technology that you’re speaking about. Start off the presentation with a description of the problem. Since software engineers are problem solvers at heart, presenting them with the problem at the beginning sets the proper context for the rest of the talk. For example, a problem statement for the HTML5 drag-and-drop API might be, "Don’t you wish there was a way to allow your users to upload files without using that ugly file input control on a form?" That instantly gets the audience thinking about the problem and if they’ve ever encountered it before. It also starts than thinking about how they’ve tried to solve that problem before and piques their interest about how you would solve the problem.

Then take the audience on a journey where the problem gets solved. Start with the basics and get more advanced as the top goes on. Make sure that by the end of the talk you have illustrated how the topic solves the problem presented at the beginning.

The end of the story is where you summarize everything that was discussed. You can do that formally with a summary slide and bullet points or informally with a short discussion. The goal is to solidify what was just covered in the audience’s minds. Think of this as the proverbial, "the moral of the story is" from the fairy tales you were told when you were little.

Be enthusiastic

How you speak and how you present yourself has a dramatic effect on how the talk is received. If you don’t remember any other piece of advice, let it be this: be enthusiastic about your talk. Show the audience that you enjoy the topic and enjoy explaining to them. Audiences tend to mirror the energy of the speaker. You’ve probably been in a talk where speaker was really nervous. Did you also start feeling a little bit nervous? That’s completely normal and happens all the time. If the speaker is relaxed and having good time, and the audience will too. If the speaker is nervous then the audience will be as well.

Choose a topic that you can get excited about. That’s the best way to make sure that you are enthusiastic in front of a crowd. Think about a story that you enjoyed telling to a friend and how enthusiastic you were telling it. And enjoy the topic, it’s hard to contain your enthusiasm for it. When the audience sees that your enthusiastic, they relax and become enthusiastic about your talk. That, in turn, makes you more relaxed.

One of the speakers that I mentored in the past had a bad habit of assuming that the audience already knew everything he was going to talk about. He littered his speaking with phrases like, "…but you probably already know that" and "…and probably not telling you anything new here". Consequently, he didn’t seem very enthusiastic about giving the talk and received low marks even though he presented good material. Why would you be enthusiastic about telling people things that they already know? Imagine if the description for talk said that the speaker would just recite facts that you already knew. You probably wouldn’t line up to get into that talk.

Always assume that what you’re telling people is completely new to them. Think about the enjoyment you get about telling a story to a friend – it’s because they don’t already know the story and you delight in seeing their reaction. That’s exactly what makes going to a talk so interesting. I have sat and listened to speakers talk about topics that I knew very well and still enjoyed it simply because the speaker was enthusiastic and entertaining.

One of my favorite speakers is my friend and former colleague Nicole Sullivan. She is an incredibly eloquent speaker who speaks with a subdued passion that really resonates with people. I frequently joke with her that she could get on stage and read the phone book and people would be enthralled. Nicole gets on stage and starts speaking, and you instantly like her. She’s smart and she obviously cares about the topic she’s presenting.

Really good speakers are like that, the audience is there to listen to the speaker first and listen to the content second. It’s the same reason you can watch a favorite movie over and over again even though you know the story: the performance itself is enjoyable even when you know the content.

Don’t try to be funny