Nicholas C. Zakas's Blog, page 13

August 8, 2012

Setting up Apache as a SSL front end for Play

We’ve been using the Play Framework[1] on WellFurnished since the beginning and have been delighted with the results. If you’re unfamiliar with Play, it’s a Java based MVC framework that allows for rapid application development. I’ve honestly never use a framework that let me get up and running so quickly. It’s been a pleasure to work with and we generally use the recommended setup of having Apache as a front end to the Play server.

Recently, I have begun working on a WellFurnished login to store our own usernames and passwords, thus eliminating the need to have a Facebook account to login. We put this off initially because it was easier to use somebody else’s login system (and security) to start getting users onto the site. We always intended to create our own login system, but we wanted to make sure that we were spending the majority of our time on features and not on implementing something that you can pretty much get for free. Now that the time has come, I’ve been investigating SSL and how to use it with Play. It was a little bit trickier than I thought, and so I wanted to share the steps in case anybody else ran into the same issues.

Basic setup

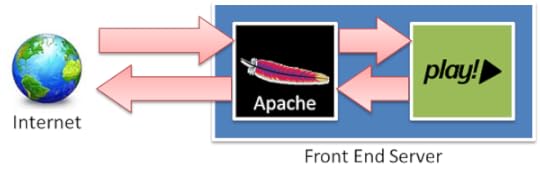

Before getting into SSL, it’s helpful to understand the overall setup and why it’s useful. The Play 1.X server is good but somewhat limited. It only recently gained SSL support and doesn’t have built-in support for gzipping of assets. As with most application servers, it’s pretty slow when serving up static content and is not designed to run on port 80 by default (it’s initially configured to run on port 9000). For all of these reasons, the documentation suggests using another server as a front end that listens to port 80, serves static assets, in general he talks to the world for Play.

I chose to use Apache because I’m familiar with it but you could easily use nginx instead. Apache is installed on the same box as the Play server and acts as the gatekeeper to the box. Traffic coming in from a browser goes to Apache first and Apache talks to the Play server on behalf of the browser. When the Play server responds, it responds to Apache, which in turn responds to the browser.

This basic architecture works by using Apache as both a forward proxy, which accesses the Play server on behalf of the Internet, and a reverse proxy, which accesses the Internet on behalf of the Play server. Setting this up in Apache is fairly trivial, first make sure that mod_proxy[2] is enabled for Apache:

sudo a2enmod proxy

Then add the following into your virtual host:

ProxyPreserveHost On

ProxyPass / http://127.0.0.1:9000/

ProxyPassReverse / http://127.0.0.1:9000/

Since Apache is acting as a proxy, the Host HTTP header sent with the request to the Play server would contain the internal name of the server rather than the original Host Header as sent from the browser. By adding ProxyPreserveHost On, Apache note is to keep the same Host header for the request to the Play server. The next two lines just set up Apache as a forward (ProxyPass) and reverse (ProxyPassReverse) proxy to the Play server. After that, you just need to reload Apache:

sudo service apache2 reload

That’s all that’s needed to get Apache proxying between the Internet and the Play server.

Enabling SSL on Apache

Play has built-in SSL support, but there is no reason to talk SSL directly to the Play server. After all, both Apache and the Play server are on the same box. Most setups with a forward proxy terminate the SSL at the proxy. That means a web browser uses SSL to talk to Apache but Apache talks to the Play server using plain old HTTP. Play is capable of determining that the request is secure or not using the request.secure flag, such as (Java):

// in a controller

if (!request.secure) {

redirect("https://" + request.domain + request.url);

}

This snippet of code redirects to the secure version of the page if the insecure version is accessed.

But before you can use that, you have to get SSL traffic going to the Play server. The first step in that process is to make sure that SSL support is enabled for Apache via mod_ssl[3]:

sudo a2enmod ssl

After that, you have to make sure that Apache is listening on port 443 for HTTPS traffic (in addition to port 80 for HTTP). Edit the /etc/apache2/ports.conf to add the port information. Port 80 should already be listed, you just need to add another line:

Port 80

Port 443

Once that’s complete, restart Apache so that it will listen to port 443:

sudo service apache restart

You now need to create a separate virtual host entry for port 443:

ProxyPreserveHost On

ServerName www.example.com

ProxyPass / http://127.0.0.1:9000/

ProxyPassReverse / http://127.0.0.1:9000/

That sets up Apache to listen on port 443 for traffic and also sets it up as a forward and reverse proxy for the Play server. Note that there is no mention of HTTPS because Apache is speaking to the Play server using HTTP.

Next, you need to enable SSL within the virtual host and provide the certificate and key files (assuming you already have them). These files can live anywhere but should not be in a publicly accessible location. You then reference them directly in the virtual host entry:

ProxyPreserveHost On

ServerName www.example.com

SSLEngine On

SSLCertificateFile /etc/apache2/ssl/server.crt

SSLCertificateKeyFile /etc/apache2/ssl/server.key

SSLRequireSSL

ProxyPass / http://127.0.0.1:9000/

ProxyPassReverse / http://127.0.0.1:9000/

The SSLEngine On directive turns SSL on while the two others simply provide paths for the certificate and key files. After one more Apache reload, the server is now speaking SSL to the outside world and HTTP to the Play server. I’ve also added in SSLRequireSSL to the entire server, ensuring that regular HTTP requests will never be honored on port 443. There are several other options available in mod_ssl That you might want to look at, but this is enough to get started.

One last step

At this point, the Play server is effectively being used over SSL with the SSL connection terminated at Apache. The setup works fine if you’re not doing anything tricky. However, there is one significant problem: request.secure always returns false. This makes sense from the Play server point of view because it is being spoken to using HTTP from Apache. Technically, the Play server is never handling a secure request. However, it’s important to be able to tell whether or not someone is connecting to your application using SSL or not, so this is not acceptable.

What you actually need is to forward along the protocol that was used to access the server. There is a de facto standard around the X-Forwarded-Proto header that is used with proxies. This header contains the original protocol (the forwarded protocol) of the request that the proxy received. The Play framework is smart enough to look for this header as part of its determination of request.secure. So you just need to add the header whenever request comes in via SSL.

To do that, make sure that mod_headers[4] Is enabled:

sudo a2enmod headers

Then you can specify the header as part of your virtual host configuration:

RequestHeader set X-Forwarded-Proto "https"

ProxyPreserveHost On

ServerName www.example.com

SSLEngine On

SSLCertificateFile /etc/apache2/ssl/server.crt

SSLCertificateKeyFile /etc/apache2/ssl/server.key

SSLRequireSSL

ProxyPass / http://127.0.0.1:9000/

ProxyPassReverse / http://127.0.0.1:9000/

The first line in the virtual host configuration sets the X-Forwarded-Proto Header for every request that comes through. The Play framework can look at this header to determine whether or not the request is secure. You need to reload Apache after making this change.

That might seem like the only change that’s necessary but there is one more that is a bit tricky to track down. Because it’s possible for multiple proxies to talk to a server, the server needs to distinguish between requests from a known proxy and an unknown one that might be trying to do harm. By default, the Play server doesn’t accept any headers beginning with X-Forwarded as truth because it can’t know for sure. You need to edit the Play application.conf file to add a list of known proxies in the XForwardedSupport key, such as:

XForwardedSupport = 127.0.0.1

This example includes only localhost as a valid proxy for which X-Forwarded headers should be used. Once this is included, request.secure reads the X-Forwarded-Proto header to determine if the request is secure. Now everything in the stack is behaving correctly.

Summary

This post took you through setting up Apache as a SSL front end for a Play application. As mentioned earlier, WellFurnished is currently using the 1.x version of Play, though expect to move to the 2.x version in the future. The Apache setup for handling SSL is fairly straightforward. If you would prefer to use nginx or another server as a front end, I suspect that setup would be roughly the same. The biggest sticking point for me when setting this up the first time was the last step, enabling XForwardedSupport for the application so that request.secure works as expected.

All of this work is going in so that we can have our own WellFurnished login and be less reliant on Facebook for handling that process. Stay tuned to WellFurnished for further details.

References

Play Framework

mod_proxy (Apache)

mod_ssl (Apache)

mod_headers (Apache)

August 1, 2012

A critical review of ECMAScript 6 quasi-literals

Quasi-literals (update: now formally called “template strings”) are a proposed addition to ECMAScript 6 designed to solve a whole host of problems. The proposal seeks to add new syntax that would allow the creation of domain-specific languages (DSLs)[1] for working with content in a way that is safer than the solutions we have today. The description on the template string-literal strawman page[2] is as follows:

This scheme extends EcmaScript syntax with syntactic sugar to allow libraries to provide DSLs that easily produce, query, and manipulate content from other languages that are immune or resistant to injection attacks such as XSS, SQL Injection, etc.

In reality, though, template strings are ECMAScript’s answer to several ongoing problems. As best I can figure, these are the immediate problems template strings attempt to address:

Multiline strings – JavaScript has never had a formal concept of multiline strings.

Basic string formatting – The ability to substitute parts of the string for values contained in variables.

HTML escaping – The ability to transform a string such that it is safe to insert into HTML.

Localization of strings – The ability to easily swap out string from one language into a string from another language.

I’ve been looking at template strings to figure out if they actually solve these problems sufficiently or not. My initial reaction is that template strings solve some of these problems in certain situations but aren’t useful enough to be the sole mechanism of addressing these problems. I decided to take some time and explore template strings to figure out if my reaction was valid or not.

The basics

Before digging into the use cases, it’s important to understand how template strings work. The basic format for template strings is as follows:

`literal${substitution}literal`

This is the simplest form of template string that simply does substitutions. The entire template string is enclosed in backticks. In between those backticks can be any number of characters including white space. The dollar sign ($) indicates an expression that should be substituted. In this example, the template string would replace ${substitution} With the value of the JavaScript variable called substitution That is available in the same scope in which the template string is defined. For example:

var name = "Nicholas",

msg = `Hello, ${name}!`;

console.log(msg); // "Hello, Nicholas!"

In this code, the template string has a single identifier to substitute. The sequence ${name} is replaced by the value of the variable name. You can substitute more complex expressions, such as:

var total = 30,

msg = `The total is ${total} (${total*1.05} with tax)`;

console.log(msg); // "The total is 30 (31.5 with tax)"

This example uses a more complex expression substitution to calculate the price with tax. You can place any expression that returns a value inside the braces of a template string to have that value inserted into the final string.

The more advanced format of a template string is as follows:

tag`literal${substitution}literal`

This form includes a tag, which is basically just a function that alters the output of the template string. The template string proposal includes a proposal for several built-in tags to handle common cases (those will be discussed later) but it’s also possible to define your own.

A tag is simply a function that is called with the processed template string data. The function receives data about the template string as individual pieces that the tag must then combined to create the finished value. The first argument the function receives is an array containing the literal strings as they are interpreted by JavaScript. These arrays are organized such that a substitution should be made between items, so there needs to be a substitution made between the first and the second item, the second and the third item, and so on. This array also has a special property called raw, which is an array containing the literal strings as they appear in the code (so you can tell what was written in the code). Each subsequent argument to the tag after the first is the value of a substitution expression in the template string. For example, this is what would be passed to a tag for the last example:

Argument 1 = [ "The total is ", " (", " with tax)" ]

.raw = [ "The total is ", " (", " with tax)" ]

Argument 2 = 30

Argument 3 = 31.5

Note that the substitution expressions are automatically evaluated, so you just receive the final values. That means the tag is free to manipulate the final value in any way that is appropriate. For example, I can create a tag that behaves the same as the defaults (when no tag specified) like this:

function passthru(literals) {

var result = "",

i = 0;

while (i < literals.length) {

result = literals[i ];

if (i < arguments.length) {

result = arguments[i];

}

}

return result;

}

And then you can use it like this:

var total = 30,

msg = passthru`The total is ${total} (${total*1.05} with tax)`;

console.log(msg); // "The total is 30 (31.5 with tax)"

In all of these examples, there has been no difference between raw and cooked Because there were no special characters within the template string. Consider template string like this:

tag`First line\nSecond line`

In this case, the tag would receive:

Argument 1 = cooked = [ "First line\nSecond line" ]

.raw = [ "First line\\nSecond line" ]

Note that the first item in raw is an escaped version of the string, effectively the same thing that was written in code. May not always need that information, but it’s around just in case.

Multiline strings

The first problem that template string literals were meant to address his multiline strings. As I’ve mentioned in previous posts, this isn’t a big problem for me, but I know that there are a fair number of people who would like this capability. There has been an unofficial way of doing multiline string literals and JavaScript for years using a backslash followed by a newline, such as this:

var text = "First line\n\

Second line";

This has widely been acknowledged as a mistake and something that is considered a bad practice, although it was blessed as part of ECMAScript 5. Many resort to using arrays in order not to use the unofficial technique:

var text = [

"First line",

"Second line"].join("\n");

However, this is pretty cumbersome if you’re writing a lot of text. It would definitely be easier to have a way to include

this directly within the literal. Other languages have had this feature for years.

There are of course heredocs[3], such as what is supported in PHP:

$text = <<

And Python has its triple quoted strings:

text = """First line

Second line"""

In comparison, template string-literals look cleaner because they use fewer characters:

var text = `First line

Second line`;

So it’s pretty easy to see that template strings solve the problem of multiline strings in JavaScript pretty well. This is undoubtedly a case where new syntax is needed, because both the double quote and single quote are already spoken for (and pretty much are exactly the same).

Basic string formatting

The problem the basic string formatting hasn’t been solved in JavaScript yet. When I say basic string formatting, I’m talking about simple substitutions within text. Think of sprintf in C or String.format() in C# or Java. This comment isn’t particularly for and JavaScript, finding life in a few corners of development.

First, the console.log() method (and its related methods) support basic string formatting in Internet Explorer 8 , Firefox, Safari, and Chrome (Opera doesn’t support string formatting on the console). On the server, Node.js also supports string formatting for its console.log()[4]. You can include %s to substitute a string, %d or %i to substitute an integer, or %f for floating-point vlaues (Node.js also allows %j for including JSON, Firefox and Chrome allow %o for outputting an object[5]). For example:

console.log("Hello %s", "world"); // "Hello world"

console.log("The count is %d", 5); // "The count is 5"

Various JavaScript libraries have also implemented similar string formatting functions. YUI has the substitute()[6] method, which uses named values for string replacements:

YUI().use("substitute", function(Y) {

var msg = Y.substitute("Hello, {place}", { place: "world" });

console.log(msg); // "Hello, world"

});

Dojo has a similar mechanism via dojo.string.substitute()[7], though it can also deal with positional substitutions by passing an array:

var msg = dojo.string.substitue("Hello, ${place}", { place: "world" });

console.log(msg); // "Hello, world"

msg = dojo.string.substitue("Hello, ${0}", [ "world" ]);

console.log(msg); // "Hello, world"

It’s clear that basic string formatting is already alive and well in JavaScript and chances are that many developers have used it at some point in time. Keep in mind, simple string formatting isn’t concerned with escaping of values because it is doing simple string manipulation (HTML escaping is discussed later).

In comparison to the already available string formatting methods, template strings visually appear to be very much the same. Here’s how the previous examples would be written using a template string:

var place = "world",

msg = `Hello, ${place}`;

console.log(msg); // "Hello, world"

Syntactically, one could argue that template strings are easier to read because the variable is placed directly into the literal so you can guess the result more easily. So if you’re going to be converting code using older string formatting methods into template strings, it’s a pretty easy conversion if you are using string literals directly in your JavaScript.

The downside of template strings is the same downside experienced using heredocs: the literal must be defined in a scope that has access to the substitution variables. There are couple of problems with this. First, if a substitution variable isn’t defined in the scope in which a template string is defined, it will throw an error. For example:

var msg = `Hello, ${place}`; // throws error

Because place isn’t defined in this example, the template string actually throws an error because it’s trying to evaluate the variable that doesn’t exist. That behavior is also cause of the second major problem with template strings: you cannot externalize strings.

When using simple string formatting, as with console.log(), YUI, or Dojo, you have the ability to keep your strings external from the JavaScript code that uses it. This has the advantage of making string changes easier (because they aren’t buried inside of JavaScript code) and allowing the same strings to be used in multiple places. For example, you can define your strings in one place such as this:

var messages = {

welcome: "Hello, {name}"

};

And use them somewhere else like this:

var msg = Y.substitute(messages.welcome, { name: "Nicholas" });

With template strings, you are limited to using substitution only when the literal is embedded directly in your JavaScript along with variables representing the data to substitute. In effect, format strings have late binding to data values and template strings have early binding to data values. That early binding severely limits the cases where template strings can be used for the purpose of simple substitutions.

So while template strings solve the problem of simple string formatting when you want to embed literals in your JavaScript code, they do not solve the problem when you want to externalize strings. For this reason, I believe that even with the addition of template strings, some basic string formatting capabilities need to be added to ECMAScript.

Localization of strings

Closely related to simple string formatting is localization of strings. Localization is a complex problem encompassing all aspects of a web application, but localization of strings is what template strings are supposed to help with. The basic idea is that you should be able to define a string with placeholders in one language and be able to easily translate the strings into another language that makes use of the same substitutions.

The way this works in most systems today is that strings are externalized into a separate file or data structure. Both YUI[9] and Dojo[10] support externalized resource bundles for internationalization. Fundamentally, these work the same way as simple string formatting does, where each of the strings is a separate property in an object that can be used in any number of places. The strings can also contain placeholders for substitutions by the library’s method for doing so. For example:

// YUI

var messages = Y.Intl.get("messages");

console.log(messages.welcome, { name: "Nicholas" });

Since the placeholder in the string never changes regardless of language, the JavaScript code is kept pretty clean and doesn’t need to take into account things like different order of words and substitutions in different languages.

The approach that template strings seemed to be recommending is more one of a tool-based process. The strawman proposal talks about a special msg tag that is capable of working with localized strings. The purpose of msg is only to make sure that the substitutions themselves are being formatted correctly for the current locale (which is up to the developer to define). Other than that, it appears to only do basic string substitution. The intent seems to be to allow static analysis of the JavaScript file such that a new JavaScript file can be produced that correctly replaces the contents of the template string with text that is appropriate for the locale. The first example given is of translating English into French assuming that you already have the translation data somewhere:

// Before

alert(msg`Hello, ${world}!`);

// After

alert(msg`Bonjour ${world}!`);

The intent is that the first line is translated to the second line by some as-yet-to-be-defined tool. For those who don’t want to use this tool, the proposal suggests including the message bundle in line such that the msg tag looks up its data in that bundle in order to do the appropriate replacement. Here is that example:

// Before

alert(msg`Hello, ${world}!`);

// After

var messageBundle_fr = { // Maps message text and disambiguation meta-data to replacement.

'Hello, {0}!': 'Bonjour {0}!'

};

alert(msg`Hello, ${world}!`);

The intent is that the first line is translated into the several lines after it before going to production. You’ll note that in order to make this work, the message bundle is using format strings. The msg tag is then written as:

function msg(parts) {

var key = ...; // 'Hello, {0}!' given ['Hello, ', world, '!']

var translation = myMessageBundle[key];

return (translation || key).replace(/\{(\d )\}/g, function (_, index) {

// not shown: proper formatting of substitutions

return parts[(index < < 1) | 1];

});

}

So it seems that in an effort to avoid format strings, template strings are only made to work for localization purposes by implementing its own simple string formatting.

For this problem, it seems like I’m actually comparing apples to oranges. The way that YUI and Dojo deal with localized strings and resource bundles is very much catered towards developers. The template string approach is very much catered towards tools and is therefore not very useful for people who don’t want to go through the hassle of integrating an additional tool into their build system. I’m not convinced that the localization scheme in the proposal represents a big advantage over what developers have already been doing.

HTML escaping

This is perhaps the biggest problem that template strings are meant to address. Whenever I talk to people on TC-39 about template strings, the conversation always seems to come back to secure escaping for insertion into HTML. The proposal itself starts out by talking about cross-site scripting attacks and how template strings help to mitigate them. Without a doubt, proper HTML escaping is important for any web application, both on the client and on the server. Fortunately, we have seen some more logical typesetting languages pop up, such as Mustache, which automatically escape output by default.

When talking about HTML escaping, it’s important to understand that there are two distinct classes of data. The first class of data is controlled. Controlled data is data that is generated by the server without any user interaction. That is to say the data was programmed in by developer and was not entered by user. The other class of data is uncontrolled, which is the very thing that template strings were intended to deal with. Uncontrolled data is data that comes from the user and you can therefore make no assumptions about its content. One of the big arguments against format strings is the threat of uncontrolled format strings[11] and the damage they can cause. This happens when uncontrolled data is passed into a format string and isn’t properly escaped along the way. For example:

// YUI

var html = Y.substitute("

Welcome, {name}

", { name: username });In this code, the HTML generated could potentially have a security issue if username hasn’t been sanitized prior to this point. It’s possible that username could contain HTML code, most notably JavaScript, that could compromise the page into which the string was inserted. This may not be as big of an issue on the browser, where script tags are innocuous when inserted via innerHTML, but on the server this is certainly a major issue. YUI has Y.Escape.escapeHTML() to escape HTML that could be used to help:

// YUI

YUI().use("substitute", "escape", function(Y) {

var escapedUsername = Y.Escape.escapeHTML(username),

html = Y.substitute("

Welcome, {name}

", { name: escapedUsername });});

After HTML escaping, the username is a bit more sanitized before being inserted into the string. That provides you with a basic level of protection against uncontrolled data. The problems can get a little more complicated than that, especially when you’re dealing with values that are being inserted into HTML attributes, but essentially escaping HTML before inserting into an HTML string is the minimum you should do to sanitize data.

Template strings aim to solve the problem of of HTML escaping plus a couple of other problems. The proposal talks about a tag called safehtml, which would not only perform HTML escaping, but would also look for other attack patterns and replace them with innocuous values. The example from the proposal is:

url = "http://example.com/";

message = query = "Hello & Goodbye";

color = "red";

safehtml`${message}`

In this instance, there are a couple potential security issues in the HTML literal. The URL itself could end up being a JavaScript URL that does something bad, the query string could also end up being something bad, and the CSS value could end up being a CSS expression in older versions of Internet Explorer. For instance:

url = "javascript:alert(1337)";

color = "expression(alert(1337))";

Inserting these values into a string using simple HTML escaping, as in the previous example, would not prevent the resulting HTML from containing dangerous code. An HTML-escaped JavaScript URL still executes JavaScript. The intent of safehtml is to not only deal with HTML escaping but also to deal with these attack scenarios, where a value is dangerous regardless of it being escaped or not.

The template string proposal claims that in a case such as with JavaScript URLs, the values will be replaced with something completely innocuous and therefore prevent any harm. What it doesn’t cover is how the tag will know whether a “dangerous” value is actually controlled data and intentionally being inserted versus uncontrolled data that should always be changed. My hunch from reading the proposal is that it always assumes dangerous values to be dangerous and it’s up to the developer to jump through hoops to include some code that might appear dangerous to the tag. That’s not necessarily a bad thing.

So do template strings solve the HTML escaping problem? As with simple string formatting, the answer is yes, but only if you are embedding your HTML right into JavaScript where the substitution variables exist. Embedding HTML directly into JavaScript is something that I warned people not to do because it becomes hard to maintain. With templating solutions such as Mustache, the templates are often read in at runtime from someplace or else precompiled into functions that are executed directly. It seems that the intended audience for the safehtml tag might actually be the template libraries. I could definitely see this being useful when templates are compiled. Instead of compiling into complicated functions, the templates could be compiled into template strings using the safehtml tag. That would eliminate some of the complexity of template languages, though I’m sure not all.

Short of using a tool to generate template strings from strings or templates, I’m having a hard time believing that developers would go through the hassle of using them when creating a simple HTML escape function is so easy. Here’s the one that I tend to use:

function escapeHTML(text) {

return text.replace(/[<>"&]/g, function(c) {

switch (c) {

case "< ": return "": return ">";

case "\"": return """;

case "&": return "&";

}

});

}

I recognize that doing basic HTML escaping isn’t enough to completely secure an HTML string against all threats. However, if the template string-based HTML handling must be done directly within JavaScript code, and I think many developers will still end up using basic HTML escaping instead. Libraries are already providing this functionality to developers, it would be great if we could just have a standard version that everyone can rely on so we can stop shipping the same thing with every library. As with the msg tag, which needs simple string formatting to work correctly, I could also see safehtml needing basic HTML escaping in order to work correctly. They seem to go hand in hand.

Conclusion

Template strings definitely address all four of the problems I outlined at the beginning of this post. They are most successful in addressing the need to have multiline string literals in JavaScript. The solution is arguably the most elegant one available and does the job well.

When it comes to simple string formatting, template strings solve the problem in the same way that heredocs solve the problem. It’s great if you are going to be embedding your strings directly into the code near where the substitution variables exist. If you need to externalize your strings, then template strings aren’t solving the problem for you. Given that many developers externalize strings into resource bundles that are included with their applications, I’m pessimistic about the potential for template strings to solve the string formatting needs of many developers. I believe that a format string-based solution, such as the one that was Crockford proposed[12], still needs to be part of ECMAScript for it to be complete and for this problem to be completely solved.

I’m not at all convinced that template strings solve a localization use case. It seems like this use case was shoehorned in and that current solutions require a lot less work implement. Of course, the part that I found most interesting about the template strings solution for localization is that it made use of format strings. To me, that’s a telling sign that simple string formatting is definitely needed in ECMAScript. Template strings seem like the most heavy-handed solution to the localization problem, even with the as-yet-to-be-created tools that the proposal talks about.

Template strings definitely solve the HTML escaping problem, but once again, only in the same way that simple string formatting is solved. With the requirement of embedding your HTML inside of the JavaScript and having all variables present within that scope, the safehtml tag seems to only be useful from the perspective of templating tools. It doesn’t seem like something that developers will use by hand since many are using externalized templates. If templating libraries that precompiled templates are the target audience for this feature then it has a shot at being successful. I don’t think, however, that it serves the needs of other developers. I still believe that HTML escaping, as error-prone as it might be, is something that needs to be available as a low-level method in ECMAScript.

Note: I know there are a large number of people who believe HTML escaping shouldn’t necessarily be part of ECMAScript. Some say it should be a browser API, part of the DOM, or something else. I disagree with that sentiment because JavaScript is used quite frequently, on both the client and server, to manipulate HTML. As such, I believe that it’s important for ECMAScript to support HTML escaping along with URL escaping (which it has supported for a very long time).

Overall, template strings are an interesting concept that I think have potential. Right off the bat, they solve the problem of having multiline strings and heredocs-like functionality in JavaScript. They also appear to be an interesting solution as a generation target for tools. I don’t think that they are a suitable replacement for simple string formatting or low-level HTML escaping for JavaScript developers, both of which could be useful within tags. I’m not calling for template strings to be ripped out of ECMAScript, but I do think that it doesn’t solve enough of the problems for JavaScript developers that it should preclude other additions for string formatting and escaping.

Update (01-August-2012) – Updated article to mention that braces are always required in template strings. Also, addressed some of the feedback from Allen’s comment by changing “quasi-literals” to “template strings” and “quasi handlers” to “tags”. Updated description of slash-trailed multiline strings.

References

Domain-specific language (Wikipedia)

ECMAScript quasi-literals (ECMAScript Wiki)

Here-Documents (Wikipedia)

The built-in console module by Charlie McConnell (Nodejitsu)

Outputting text to the console (Mozilla Developer Network)

YUI substitute method (YUILibrary)

dojo.string.substitute() (Dojo Toolkit)

YUI Internationalization (YUILibrary)

Translatable Resource Bundles by Adam Peller

Uncontrolled format string (Wikipedia)

String.prototype.format by Douglas Crockford (ECMAScript Wiki)

July 24, 2012

Thoughts on ECMAScript 6 and new syntax

I am, just like many in the JavaScript world, watching anxiously as ECMAScript undergoes its next evolution in the form of ECMAScript 6. The anxiety is a product of the past, when we were all waiting for ECMAScript 4 to evolve. The ECMAScript 4 initiative seemed more like changing JavaScript into a completely different language that was part Java, part Python, and part Ruby. Then along came the dissenting crowd, including Douglas Crockford, who brought some sanity to the proceedings by suggesting a more deliberate approach. The result was ECMAScript 5, which introduced several new capabilities to the language without introducing a large amount of new syntax. The focus seemed to be on defining the so-called “magical” parts of JavaScript such as read-only properties and non-enumerable properties while setting the path forward to remove “the bad parts” with strict mode. The agreement was that TC39 would reconvene to address some of the larger language issues that were being solved in ECMAScript 4 and punted on in ECMAScript 5. That process began to create the next version of the language code-named “Harmony”.

We are now quite a bit further along the development of ECMAScript 6 so it’s a good time to stop and take a look at what’s been happening. Obviously, the evolution of any language focuses around adding new capabilities. New capabilities are added in ECMAScript 5 and I fully expected that to continue in ECMAScript 6. What I didn’t expect was how new capabilities would end up tied to new syntax.

Good new syntax

I’ve had several conversations with people about various ECMAScript 6 features and many have the mistaken belief that I’m against having new syntax. That’s not at all the case. I like new syntax when it does two things: simplifies an already existing pattern and makes logical sense given the rest of the syntax. For example, I think the addition of let for the creation of block-scoped variables and const for defining constants make sense. The syntax is identical to using var, so it’s easy for me to make that adjustment in my code if necessary:

var SOMETHING = "boo!";

const SOMETHING = "boo!";

let SOMETHING = "boo!";

The cognitive overhead of using new keywords with the familiar syntax is pretty low, so it’s unlikely that developers would get confused about their usage.

Likewise, the addition of the for-of loop is some syntactic sugar around Array.prototype.forEach(), plus some compatibility for Array-like items (making it syntactic sugar for Firefox’s generic Array.forEach()). So you could easily change this code:

var values = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6];

values.forEach(function(value) {

console.log(value);

});

Into this:

var values = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6];

for (let value of values) {

console.log(value);

}

This makes complete sense to me. The syntax is very similar to the already existing for and for-in loops and mimics what’s already available with Array.prototype.forEach(). I look at this code, and it still looks like JavaScript, and that makes me happy. Even if I choose not to use the new syntax, I can still pretty much accomplish the same thing.

Bad new syntax

One of the features of ECMAScript 6 that has received a lot of attention by the so-called “fat arrow” functions[1]. This appears to be an attempt to solve several problems:

this binding – The desire to more easily specify the value of this Within a function. This is the problem that Function.prototype.bind() solves.

Avoid typing “function” – For some reason, people seem to hate typing the word “function”. Brendan Eich himself has said that he regrets using such a long word. I’ve never really had a problem with it or understood people’s frustration with having to type those characters.

Avoid typing parentheses, braces – Once again, the syntax seems to be the issue. And once again, I just don’t get it.

So essentially this:

function getName() {

return this.name;

}

var getWindowName = getName.bind(window);

Becomes this:

var getWindowName = () => this.name;

And this:

function getName(myName) {

return this.name myName;

}

var getWindowName = getName.bind(window);

Becomes this:

var getWindowName = myName => this.name myName;

I know I’m probably alone on this, but I don’t think the syntax is clear. If there are no arguments to the function, then you need to provide parentheses; also, if there is more than one argument, you need parentheses. If there’s just one argument, then you don’t need the parentheses. With me so far?

If you want to return an object literal from one of these functions, then you must enclose the object literal and parentheses:

let key_maker = val => ({key: val});

Then if you want to do more than one thing in the function body, you need to wrap it in braces and use a return Like you would in a regular function:

let sumIt = (val1, val2) => {

var sum = val1 val2;

return sum;

};

And don’t be confused into thinking these functions act like all other functions. There are several important differences between functions declared using the fat arrow syntax and functions declared in the more traditional way:

As mentioned previously, the value of this is static. It always takes the value of this for the enclosing function or global scope.

You can’t use new with a fat arrow function, it throws an error.

Fat arrow functions do not have a prototype property.

So not only are arrow functions trying to solve a bunch of problems, they also introduce a bunch of side effects that aren’t immediately apparent from the syntax. This is the type of new syntax that I don’t like. There’s a lot that goes on with arrow functions that is unexpected if you think that this is just a shorthand way of writing functions.

What’s more, I don’t know how to read this out loud. One of the things I’ve always liked about JavaScript is that it says what it does so I can actually read the code out loud and it makes sense. I have no idea how to pronounce that arrow function. “Let variable equal to a group of arguments that executes some statements?” It just doesn’t work for me. In some ways, this is the sort of problem you end up with when you try to solve multiple problems with one solution. There are a lot of rules to remember with this syntax and a lot of side effects to consider.

Just for argument sake, if someone asked me what sort of new syntax I would suggest for sugaring Function.prototype.bind(), I would choose something along the lines of this:

// My own attempt at sugaring Function.prototype.bind() - not ES6

function getName() {

return this.name;

}

This sort of syntax looks familiar to me while actually being new. I would read it as, “define a function in the scope of window called getName.” The idea is that this would always end up equal to window. Granted, the solves only one of the problems that arrow functions try to solve, but at least it says what it does.

Ugly new syntax

There are other features in ECMAScript 6 that make me feel like JavaScript is becoming an ASCII art language. For some reason, instead of adding new capabilities with already existing syntax, the specification adds new capabilities only with new syntax. What puzzles me the most about this is that these capabilities are those that already exist in other languages in some form.

Case in point: quasis (aka quasi-literals)[2]. Quasis seem to be a solution for many different problems in JavaScript. As best I can tell, quasis are supposed to solve all of these problems:

String formatting – JavaScript has been missing this for a long time. Languages such as C# and Java have a method called String.format() that allows simple symbol substitution in strings. Quite honestly, an implementation of that in JavaScript would make me incredibly happy (Crockford has actually proposed something along those lines[3]).

Multiline strings – For some reason, people feel like there needs to be a standard way of doing multiline strings that isn’t what’s already implemented using a backslash before a newline character.

HTML escaping – This is also something JavaScript has been missing for a long time. While it has shipped with URL escaping for quite a while now, HTML escaping has been noticeably missing.

Quasis use the backtick symbol (`) to indicate a section of code that requires variable substitution. Inside of the backticks, anything contained within ${...} will be interpreted as JavaScript in the current context. The basic syntax is as follows:

someFunc`Some string ${value}`;

The idea is that someFunc is the name of a function (a quasi handler) that interprets the value enclosed in the backticks. There are several use cases in the proposal, such as the creation of a safehtml quasi handler for doing HTML escaping and a msg quasi handler for performing localization substitutions. The ${value} is interpreted as the value of a variable named value. You can also have multiple lines within the backticks:

someFunc`Some string ${value}.

And another line.`;

I’m not going to go into all of the ins and outs of quasis, for that you should see Axel Rauschmayer’s writeup[4]. If you read through his post, you’ll see that this is a fairly involved solution to the already-solved problems I mentioned earlier. What’s more, it doesn’t even look like JavaScript to me. With the exception of multiline strings, the problems can be solved using regular JavaScript syntax. Once again, if it were up to me, this is how I would solve them:

// My take at string formatting - not in ES6

var result = String.format("Hi %s, nice day we're having.", name);

// My take at HTML escaping - not in ES6

var result = String.escapeHtml("Does it cost < $5?");

In these cases, it seems like a bazooka is being used when a water gun would suffice. Adding the capability to format strings and escape HTML is certainly important for the future of JavaScript, I just don’t see why there has to be a new syntax to solve these problems. Of everything in ECMAScript 6, quasis is the feature I hope dies a horrible, painful death.

Conclusion

I’m admittedly a bit of a JavaScript purist, but I’m willing to accept new syntax when it makes sense. I would prefer that new capabilities be added using existing syntax and then layer syntactic sugar on top of that for those who choose to use it. Providing new capabilities only with new syntax, as is the case with quasis, doesn’t make sense to me especially when the problems are both well-defined and previously solved in other languages using much simpler solutions. Further, only using new syntax for new capabilities means that feature detection is impossible.

It seems like in some cases, TC 39 ends up creating the most complicated solution to a problem or tries to solve a bunch of problems all at once, resulting in Frankenstein features like arrow functions and quasis. I believe that the intent is always good, which is to avoid problems that other languages have seen. However, the result seems to make JavaScript much more complicated and the syntax much more foreign. I don’t want JavaScript to be Python or Ruby or anything else other than JavaScript.

References

Arrow function syntax by Brendan Eich

Quasi-Literals

String.prototype.format() by Douglas Crockford

Quasi-literals: embedded DSLs in ECMAScript.next by Dr. Axel Rauschmayer

July 11, 2012

It’s time to stop blaming Internet Explorer

A couple of days ago, Smashing Magazine published an article entitled, Old Browsers Are Holding Back The Web[1]. The author of this article that “old browsers” are holding web developers back from creating beautiful experiences. Old browsers, in this case, apparently referred to Internet Explorer version 6-9. That’s right, the author groups Internet Explorer 9 into the same group as Internet Explorer 6. He goes on to list some of the things that you can’t use in Internet Explorer 8 and 9. You can read the rest of the article yourself to get the details.

Articles like this frustrate me a lot. For most of my career, I’ve fought hard against the “woe is me” attitude embraced by so many in web development and articulated in the Smashing Magazine article. This attitude is completely counterproductive and frequently inaccurately described. Everyone was complaining when Internet Explorer 6 had a 90%+ marketshare. That share has shrunk to 6.3% today[2] globally (though the article cites a much smaller number, 0.66%, which is true in the United States). Microsoft even kicked off a campaign to encourage people to upgrade.

I can understand complaining about Internet Explorer 6 and even 7. We had them for a long time, they were a source of frustration, and I get that. I would still never let anyone that I worked with get too buried in complaining about them. If it’s our job to support those browsers then that’s just part of our job. Every job has some part of it that sucks. Even at my favorite job, as front end lead on the Yahoo homepage, there were still parts of my job that sucked. You just need to focus on the good parts so you can tolerate the bad ones. Welcome to life.

But then the article goes on to bemoan the fact that so many people use Internet Explorer 8 and that Internet Explorer 9 is gaining market share. Are you kidding me? First and foremost, I would much rather support Internet Explorer 8 then I would 6 and 7. Microsoft forcing most people to upgrade from 6 and 7 to 8 is an incredible move and undoubtedly a blessing. Internet Explorer 8 isn’t perfect, but it’s a nice, stable browser.

Internet Explorer 9, on the other hand, is a damn good browser. The only reason it doesn’t have all of the features as Chrome and Firefox is because they rebuilt the thing from scratch so that adding more features in the future would be easier. Let me say that again: they rebuilt the browser from scratch. They necessarily had to decide what were the most important features to get in so that they could release something and start getting people to upgrade from version 8. If they had waited for feature parity with Chrome or Firefox, we probably still wouldn’t have Internet Explorer 9.

The constant drumming of “Internet Explorer X is the new Internet Explorer 6″ is getting very old. Microsoft has done a lot to try to correct their past transgressions, and it seems like there are still too many people who aren’t willing to let go of old grudges. There will always be a browser that lags behind others. First it was Mosaic that was lagging behind Netscape. Then it was Netscape lagging behind Internet Explorer. Then it was Internet Explorer lagging behind Firefox. People are already starting to complain about Android 2.x browsers.

What makes the web beautiful is precisely that there are multiple browsers and, if you build things correctly, your sites and applications work in them all. They might not necessarily work exactly the same in them all, but they should still be able to work. There is absolutely nothing preventing you from using new features in your web applications, that’s what progressive enhancement is all about. No one is saying you can’t use RGBA. No one is holding a gun to your head and saying don’t use CSS animations. As an engineer on the web application you get to make decisions every single day.

The author of the Smashing Magazine article very briefly mentions progressive enhancement as a throwaway concept that doesn’t even enter into the equation. Once again, this is indicative of an old attitude of web development that is counterproductive and ultimately lacking in creativity. The reason that I still give talks about progressive enhancement is because it allows you to give the best experience possible to users based on the browser’s capabilities. That’s the way the web was meant to work. I’ve included a video of that talk below in case you haven’t seen it.

It’s not actually old browsers that are holding back the web, it’s old ways of thinking about the web that are holding back the web. Fixating on circumstances that you can’t change isn’t a recipe for success. The number of browsers we have to support, even “old browsers”, just represent constraints to the problems that we have to solve. It is from within constraints that creativity is born[3]. The web development community has evolved enough that we should stop pointing fingers at Internet Explorer and start taking responsibility for how we do our jobs. Let’s create solutions rather than continually pointing fingers. We are better than that.

Clarification (2012-July-11): I think some people have jumped on my statement about Internet Explorer 8 and missed the larger point of the article. I am not saying that Internet Explorer 8 (or 9!) is on par with Chrome or Firefox. All I am saying is that the constant complaining about Internet Explorer has gotten old. Yes, complaining is useful to get people to listen. Microsoft is listening, so continuing to complain doesn’t do anything except perpetuate an attitude that I would rather not have in web development. Let’s give them a chance to right the ship without retrying them for past transgressions perpetually.

References

Old Browsers Are Holding Back The Web

IE6 Countdown

Need to create? Get a constraint

July 5, 2012

iOS has a :hover problem

Recently, I got my first iPad. I’ve had an iPhone since last year, and had gotten used to viewing the mobile specific view of most websites. When I got the iPad, it was my first time experiencing desktop webpages using a touch interface. Generally, the transition was easy. I just tapped on links I wanted to navigate to. Although sometimes they hit target seemed a little bit too small, I would just zoom in and tap away. Then I started noticing something: on certain links it was taking two taps instead of one to navigate. Most worrisome to me, personally, was that I noticed this on the WellFurnished home page. Of course, I had to dig in and figure out what was happening.

:hover exists everywhere

One of the things we’ve been told and I’ve repeated over and over again is that touch devices have no concept of hover. On a desktop with a mouse, you can move the pointer over an area of the screen and it can detect that to create a visual cue. That doesn’t mean you have activated that particular part of the screen, it’s just a visual indication that this part of the screen is “alive”.

Naturally, with a touch device, there really isn’t a lingering pointer. Designers who have relied on hover states to show functionality all of a sudden had unusable interfaces. This was one of the trends I thought hard against while I was at Yahoo: making sure that important functionality wasn’t displayed only on hover. It’s a clear accessibility issue for people who are not using a mouse.

So it goes without saying that most developers expect touch devices to simply ignore CSS rules containing :hover. That’s a logical assumption to make because, once again, there’s no such thing as a hover on a touch device. Except when there is.

This is where the people at Apple might have been a bit too smart. They realized that there was a lot of functionality on the web relying on hover states and so they figured out a way to deal with that in Safari for iOS. When you touch an item on a webpage, it first triggers a hover state and then triggers the “click”. The end result is that you end up seeing styles applied using :hover for a second before the click interaction happens. It’s a little startling, but it does work. So Safari on iOS very much cares about your styles that have :hover in the selector. They aren’t simply ignored.

No double taps

When I started experiencing the double tap behavior, I was noticing what appeared to be a hover state being shown after the first. Immediately I started looking at all the rules containing :hover. If I removed those rules, then the link worked with one tap. As soon as I added the rules back in, I was back to having the double tap. Clearly, this had something to do with how :hover is handled by Safari in iOS.

My first step was to create a simple example to see if I could reproduce it. I started out with a link that had a hover state:

a:hover {

color: red;

}

When I tried that, the link worked with one tap and I saw the color change briefly before navigating.

My next idea was that it might be a link inside of a container that had a :hover rule and came up with another example:

p:hover a {

color: red;

}

Once again, the link navigated with a single tap after displaying the change in color. I decided to go back to my original code and look at it more carefully. That’s when I noticed a slight difference between my test cases and the real world use case.

Double tap!

The culprit, as it turns out, is a combination of two factors. It’s not simply a :hover rule that triggers the double tap behavior. It’s a :hover Rule that either hides or shows another element using visibility or display. For example:

p span {

display: none;

}

p:hover span {

display: inline;

}

Tap meYou tapped!

It seems that the good people at Apple were very concerned about controls being hidden and only displayed on hover in webpages. Whenever you run into this situation, where an element is initially hidden and then displayed on hover, you will run into the double tap issue. The first tab will display the change in element and the second tap will navigate. If you then tap somewhere else on the screen, the :hover rule is no longer applied and you need to start the sequence over again.

You can try this all for yourself using this test page.

I went on and tried several other CSS properties and the only ones to trigger this behavior are visibility and display.

Possible workarounds

Shortly after originally posting this article, a couple of people on twitter gave some good suggestions for working around this issue area. Jacob Smartwood pointed out[1] that Modernizr provides a no-touch CSS class that indicates the browser doesn’t support touch. In that case, you can just make sure that all of your :hover rules are preceded by .no-touch, such as:

p span {

display: none;

}

.no-touch p:hover span {

display: inline;

}

Tap meYou tapped!

This works although it has the side effect of changing the specificity of the rule. In some cases this might not matter, but in others it might be important.

Oscar Godson pointed out[2] that touch can be detected in JavaScript with a simple piece of code, allowing you to implement your own Modernizr-like solution:

if ("ontouchstart" in document.documentElement) {

document.documentElement.className += " no-touch";

}

Conclusion

The mysterious double tap issue is caused by a :hover rule that changes the visibility or display properties of an element on the page. Changing any other property still allows a single tap to navigate to a link. I was only able to test this on iOS 5, as both my iPhone and iPad have it installed. Mobile Safari as well as any apps using the UIWebView (including Chrome) are affected. The Kindle Fire doesn’t exhibit this behavior at all. I would love to hear from others using other devices to see if any other browsers exhibit this behavior.

So don’t believe people when they tell you that hover doesn’t exist on touch devices. At least on iOS, hover does exist and needs to be planned for accordingly. If you are using a :hover rule to show something in your interface, you may want to hide that rule when serving your page to a touch device. It might be a good idea to just completely remove all :hover rules for any experience that’s going to be served to a touch device. The touch-based world doesn’t need hover, so be careful not to inject it accidentally.

Update (5-July-2012) – added possible workarounds that were mentioned on Twitter.

References

Jacob Smartwood’s tweet

Oscar Godson’s tweet

July 3, 2012

Book review: Adaptive Web Design

I’ve known Aaron Gustafson for about five years. We met at a conference initially and stayed in touch throughout the years despite living on opposite coasts and rarely seeing each other in person. We have a lot in common, such as the belief in front-end engineering as an important discipline and the value of progressive enhancement. It’s the latter that Aaron focuses on in his book, Adaptive Web Design.

I’ve known Aaron Gustafson for about five years. We met at a conference initially and stayed in touch throughout the years despite living on opposite coasts and rarely seeing each other in person. We have a lot in common, such as the belief in front-end engineering as an important discipline and the value of progressive enhancement. It’s the latter that Aaron focuses on in his book, Adaptive Web Design.

The book is an easy read at 144 pages and is the gentlest of introductions to the core concepts of progressive enhancement. Aaron takes you carefully from the basics of HTML and semantic markup all the way through applying JavaScript and ARIA. It truly is amazing how much information he managed to cram into a small book without making me feel overwhelmed at the end.

It begins with a description of progressive enhancement. The first chapter is aptly named, “Think of the user, not the browser”. If you learn nothing else from this book, it should be this very simple lesson. Most of the time people forget that web applications are being made for users and not for browsers. The tips and techniques are all designed to give users the best experience possible. That is exactly the heart of progressive enhancement and a great way to start the book.

The book takes you through the design decisions Aaron made when designing his Retreats 4 Geeks website. Having a case study that is carried throughout the book really helps you to get a feel for what he was trying to accomplish. There is discussion about content and responsive design and accessibility and just about everything in between. The feeling I got at the end was that the design decisions were fairly obvious and I would’ve done the same thing. In reality, that’s a tribute to Aaron’s writing than it is about my understanding of the topic. The decisions seem easy and obvious because of how the material is presented not because I have any idea what I’m doing. That’s what makes this book so useful.

Aaron makes the topic of progressive enhancement approachable to anyone regardless of their level of experience. If you’ve never done web design or don’t know what progressive enhancement is, this book is a perfect introduction. If you’re an experienced front-end engineer, you may be tempted to breeze through the book because the topics seem very general. But don’t. It’s the extra insights that Aaron injects into the description that makes the book valuable.

In the end, about the only complaint that I have about the book is that it’s too short. I was left wanting more, a lot more. And that’s not necessarily a bad thing.

June 28, 2012

What’s a software engineer, anyway?

I’ve received a lot of feedback over the past couple of weeks regarding my last two blog posts. The overwhelming majority seem to really like them. There are some, however, that have raised some interesting questions. Questions that deserve a bit more exploration than a simple blog comment provides. For instance, some seem to be drawing a distinction between web developers and software engineers based on the ability to complete some sort of task. Whether someone is capable of implementing quicksort from memory or setting up a server on their own or implementing a neural network for predictive analysis shouldn’t be the measure of whether someone is a software engineer or not.

As I stated before, a software engineer is simply someone who writes code for a living. That’s it. How do you know if your primary job is actually writing code? It’s actually quite formulaic.

Software engineering functions

There are two primary functions of a software engineer: development and maintenance. Development is the fun part, the part where you get to create new things or augment existing things with new functionality. Development is the breath of a software engineer – it’s what we live for. There’s nothing more exciting than creating something new. And every software engineer wants to be doing this as much as possible. Unfortunately, that only lasts for so long.

The second function, maintenance, is what many software engineers dread. This is otherwise known as fixing bugs. When it follows development pretty closely, people generally don’t mind. But when you’re maintaining code somebody else wrote, especially if it was written a long time ago, this quickly turns into the part that many engineers hate. Everyone is always looking for a way to get back into development, even though maintenance is a nice mental break from the hurried development cycle.

Almost all software engineers begin their careers doing maintenance. It’s very common for interns or other junior engineers to simply start by fixing bugs. In fact, some companies do that with more experienced engineers, too. The reason behind this is because figuring out what’s wrong helps you to learn about the software as a whole. Debugging is an excellent way to get acclimated to a new code base. There is nothing as revealing as stepping through code that you’ve never seen before to figure out why something is happening.

Engineers move on to real development, creating something from scratch, when they’re good enough at the maintenance tasks that they know their way around the software.

Software engineering focus areas

All software engineers perform functions in one of two focus areas. The first focus area is components. Almost all software engineers start out working on components, which are just pieces of some larger system. You’ll work on a single piece of something within a specific framework so that you can get the job done easily. The majority of software engineers remain component-based for most of their careers.

The second focus area is systems. These are usually software engineers who started out working on components and became fascinated with how the larger framework and ecosystem worked. Understanding systems is a very different skill set from understanding components because you need to think about relationships. Components within the system have relationships with other components within that same system (and potentially with other systems). Dealing with systems is frequently called software architecture, and the practitioners are called architects.

While all software engineers will work on components at some point in their career, not all software engineers will work with systems. Understanding systems is a very different skillset than understanding components. It’s the difference between knowing how to recognize and replace a broken screw versus putting together an engine from its component parts. Without a high-level understanding of how the system works, there is no way to complete the task.

On any given team, you typically find the lead is the one who is working at a systems level while everyone else is working at component level. Software architects live almost completely in the realm of systems, something that the best architects struggle with because the component builders that have all the fun (read: get to actually code!).

What’s not important

Notice to this point I haven’t actually talked about programming languages at all. As I’ve stated before, the programming language that you use is inconsequential. Whether you’re working with C, Java, HTML, CSS, or JavaScript, your role will still fall into line with what I’ve discussed above. You will be a maintainer of the component or system or you’ll be a developer of a component or a system. The actual tools that you use for the job depend very much on the component and on the system.

Those who say that all software engineers should be able to implement quicksort from memory or be able to set up a server on their own are completely misguided. These are tasks based very much on the role that the engineer is filling, which in turn is based on the components and systems that she works with. It has absolutely nothing to do with whether she is a software engineer or not.

I also heard from some people that you shouldn’t be considered a software engineer and unless you had formal training in computer science. I disagree with this assessment. First and foremost, colleges and universities teach only the very basics. Perhaps with the exception of those in postgraduate or PhD programs, the things that you learn in a computer science program are not the things that you end up using on the job in your career. Further, there are a large number of skills that are very important for software engineers that are still not yet taught in colleges.

HTML, CSS, and JavaScript are rarely taught in college. NoSQL databases are never taught. Web application architecture is never taught. In my career, I’ve used very little of what I learned in my college computer science program. The skills for which I have been hired are things that I taught myself over the years. A lot of front-end engineers are in the exact same boat. Because the skills that we possess aren’t taught in school, we have to teach ourselves. That doesn’t make us any less software engineers than anyone else. It just makes us different.

Conclusion

Software engineers are those people who are paid to write code. The two main functions of the software engineer our maintenance and development, and both of those can take place within components or systems. The nature of those components and systems is what defines the type of software engineer one is. It doesn’t matter what sort of tools are programming languages you use, as long as you are fulfilling these roles and writing code, you are a software engineer.

June 19, 2012

Web developers are software engineers, too

When I went to college I knew I wanted to work with computers but I didn’t know what exactly I wanted to do. I had fallen in love with a Packard Bell “multimedia” computer with a Pentium processor and a (gasp!) CD-ROM drive. I spent every waking moment on that computer doing nothing in particular but constantly building little tools and tweaking the system. It was all I could think about doing, and I knew that this was my career.

In college I took the requisite courses. Computer Science I and Computer Science II taught in Pascal. C for UNIX. C++. Smalltalk. Prolog. Assembly. Data structures and algorithms. Databases. All that stuff that requires you to sit in front of the terminal and type furiously to get a result. I found that really boring. I’m a very visual person, and staring at an endless stream of text all day drove me insane. That’s when I started experimenting with the web.

I’m dating myself here, but during my first year in college (1996) I set up my first webpage on AOL. I set it up mostly to keep in touch with high school friends and before I knew it I was spending a lot of time on that page. I was constantly updating and tweaking and trying to add new functionality. After a few months of doing this, I wanted to find a way to turn it into a job. My college, however, had zero classes on web development in the curriculum. It was just too new. So I learned mostly on my own, and got myself an internship at a startup doing web development.

It’s been over 15 years since then. Business has shifted to the web and with it the demand for web developers has steadily increased. What is surprising to me is what hasn’t changed: the perception of web developers as a whole.

In most companies, both large and small, web development is seen as some sort of gross amalgam of design and engineering. It’s not unlikely to see web developers in strange organizational groupings. Sometimes they are under design, sometimes they’re under product management, sometimes they don’t exist at all. I’ve spoken with a lot of web developers who have expressed this frustration to me. It’s hard for them to get any respect in the organization for what they do. And that starts with the organization as a whole.

My last job in Massachusetts was at VistaPrint. I really enjoyed going to work every day because the people there were so fabulous. I made a lot of really good friends there and always looked forward to being in the office around everyone. What I didn’t like was that I, along with anyone else who wrote code, was a “software engineer”. And every software engineer did everything from writing database queries to writing backend code to writing HTML, CSS, and JavaScript. It really didn’t matter if you had a particular skill in one of those areas, you still ended up doing everything. I tried to make the case several times for a different class of engineer, one who could spend her time focusing on client-side issues, but to no avail. So while I sat by and watched ugly templates being created and pushed to production, I was too busy writing SQL scripts to do anything about it. I really don’t this setup as it enforces a “jack of all trades, master of none” mentality.

One of the things that drew me to Yahoo was that I would be able to focus on HTML, CSS, and JavaScript. I would be able to leave the backend stuff to somebody else, and just focus on the things I love. Yahoo was really one of the first companies that grokked web development. They started out by creating a new role called “web developer” and hired on an amazing array of developers very early on to help lead the company’s march into this new era: Thomas Sha, Eric Miraglia, Nate Koechley, Mike Lee, and more. From top to bottom, this was an all-star lineup and a tremendous way for Yahoo to take a step towards being serious about web development.

Shortly after that, led by these first few web developers, Yahoo decided that all of those talented individuals were actually software engineers. Every single “web developer” became a “front-end engineer” overnight. They were now officially part of engineering, where they should have been all along. What followed was, in my opinion, the development of the greatest front-end community in the world. This was before Google became the place to work and long before Facebook and Twitter entered into the minds of engineers. A lot of the best practices we have today, especially in the realms of performance, progressive enhancement, open APIs, and accessibility, come directly from the work that was done at Yahoo during this period. By the time I arrived at Yahoo in 2006, the front-end community was vibrant and thriving, transforming Yahoo into a company that took incredible pride in crafting Web experiences. I was honored and privileged to be able to contribute to that community and work with all those people.

Some of the amazing engineers that came out of that community went on to do great things. Thomas Sha founded YUI and got the organizational support for it to thrive. Eric Miraglia went on to become vice president of product at Meebo, which was just acquired by Google. Nate Koechley became an internationally recognized authority on CSS and front-end development. Mike Lee went on to found and co-found several startups. Douglas Crockford formalized JSON and became a worldwide authority on JavaScript as well as an author. Steve Souders became a worldwide authority on performance, published the first performance data from a large company, created YSlow, wrote two books, and co-founded the Velocity conference. Bill Scott set about creating front-end communities as VP of UI Engineering at Netflix and Senior Director of UI Engineering at PayPal. Nicole Sullivan became an internationally known authority on CSS for her OOCSS approach and a highly sought-after performance consultant. Stoyan Stefanov took over development of YSlow from Steve, became an authority on performance and the author of several books. Isaac Schlueter created npm and became lead of Node.js. Chris Heilmann became an internationally known developer evangelist. Scott Schiller became the leading authority on web based audio through his SoundManager 2 project. I could go on and on and probably fill up several pages of front-end engineers from Yahoo who have made significant contributions to the world of web development. Suffice to say, building a great front-end community attracts great people.

Many of the front-end engineers from Yahoo can be found at companies large and small all around the world, helping to bring the same level of professionalism to other companies.

Yet in so many companies there is still a lack of respect for web development. Quite frequently we are labeled as “not engineers”, and sometimes even shunned by the “real” engineers. What I know, what I learned from Yahoo, is that what we do matters (this actually comes directly from Nate Koechley’s required “How to be a front-end engineer at Yahoo” class during my orientation). We may not have the same training and skills as traditional software engineers, but that doesn’t mean we aren’t software engineers. Yes, anyone can be a coder, because that just means you write code. What makes you a software engineer is that you’re paid primarily to write code that ends up being used by your customers. The fact that your code isn’t Java or C++ doesn’t make you any less of an engineer than someone who uses those every day.

(Note: I’m intentionally skipping over the typically arbitrary distinction some make between “developer” and “engineer”. As far as I’m concerned, they mean the same thing.)